Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Higher Education

versión On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.34 no.3 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/34-3-3466

GENERAL ARTICLES

Negotiating the "new normal": university leaders and marketisation

L. CzerniewiczI; R. MogliacciII; S. WaljiIII; R. SwartzIV; M. IvanchevaV; B. SwinnertonVI; N. MorrisVII

IUniversity of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching, e-mail: laura.czerniewicz@uct.ac.za / https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1239-7493

IIUniversity of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, e-mail: Rada.Mogliacci@uct.ac.za

IIIUniversity of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, e-mail: Sukaina.walji@uct.ac.za

IVUniversity of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, e-mail: Rebecca.Swartz@uct.ac.za

VUniversity of Leeds, Leeds, England, e-mail: M.Ivancheva@Leeds.ac.uk

VIUniversity of Leeds, Leeds, England, e-mail: B.J.Swinnerton@Leeds.ac.uk

VIIUniversity of Leeds, Leeds, England, e-mail: N.P.Morris@Leeds.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

This article explores how leaders, key decision-makers in research-intensive public universities perceive marketisation in the sector in relation to public-private arrangements in teaching and learning provision. The focus is on the nature of relationships between public universities and those private companies engaged in the co-creation, delivery and support of educational provision. It draws on 16 interviews with decision makers - senior leaders and managers in higher education at six research-intensive universities in South Africa and England. Questions raised in this article are: How do senior decision makers perceive the entry of private players into public higher education? What are their experiences of working in partnership with private companies? What effect do they think the relationship is having on the status of the public university? How do they talk about the market actors? We observe that university leaders in both study countries, despite their different positions in the global field of higher education, and the hybrid moral economy around processes of marketisation all use language borrowed from the business sector to justify or reject marketisation. This indicates an unprecedented level of normalisation of this rhetoric in a public sector otherwise sensitive to language use posing serious questions about the nature of public universities in this marketised era.

Keywords: marketisation, public-private partnership, digitisation

INTRODUCTION

This article considers how decision makers in research-intensive public universities perceive marketisation in the sector in relation to teaching and learning provision. Undertaken pre-Covid19, this was one of the questions in a broader project which asking how unbundling, digitisation and marketisation are changing the nature of HE provision in South Africa and England, and what impact this will have on widening access, educational achievement, employability and the mission of the public university. The study is interested in the nature of relationships between public universities and other actors, particularly private companies, in relation to the creation, delivery and support of educational provision as well as public universities' perspectives on these relationships.

The study draws on 16 interviews with university leaders, senior decision makers in public higher education at six research-intensive universities in South Africa and England. While the overall sample also included six teaching-oriented universities, we narrow down the focus of this article to research-intensive universities which have been the part of the sector most actively engaged with (rather than merely exploring the possibility of) partnering with private companies for unbundled educational provision. Unbundling here is used to designate the process of disaggregation of educational provision and the practice of its delivery via partnerships between universities and external stakeholders, often businesses offering digital platforms for online learning (see Swinnerton et al. 2018). The perspective is that of leaders in decision-making roles, rather than academics or students, thus shedding light on a key group of actors who are, according to the literature, engaged in forms of market-making in HE (Shore and Wright 2016). Our questions include: How do senior decision makers perceive the entry of private players in public HE? What are their experiences of working in partnership with private companies? What effect do they think the relationship is having on the status of the public university? How do they talk about the university as an actor in this exchange? On this basis we show the degree to which marketisation has been normalised not just as a process but also in the way that marketised language is used to explain decisions made by public universities on partnering with businesses, creating a "new normal" in the sector.

Marketisation is a contested term that is often used as an umbrella concept, incorporating a constellation of concomitant processes including privatisation, commercialisation, commodification, corporatisation and financialisation, each of which bring empirical and theoretical resources to bear. Following Dill (2003, 2) and Levidow (2002, 227) our working definition of marketisation is that it is a process of introduction of competition for the allocation of resources to actors and organisations operating within the public sector. In the HE sector it means that traditionally wholly publicly funded institutions are competing with each other for state funding and other income as well as with new providers, who are likely to be operating with different business models, including for profit. The focus here is on how university decision makers perceive the involvement of private sector actors in the public higher education sector, as well as how market practices and agendas are seen to be entering or becoming part of public institutions. The assumption is that in both study contexts there is a hybrid economy which is varied in its manifestation, with relationships more or less emergent or established.

FRAMING MARKETISATION

Human capital theory which has influenced HE policy making in many countries to varying degrees, is premised on the argument that education triggers "private enrichment, career success and national economic growth" (Marginson 2017, 1). Introduced as part of a bigger ideological apparatus along with the new public management paradigm, human capital theory has underpinned and justified policy making that enables funding regimes to decrease public investment in HE and increase the financial burden on students and their families (Wangenge-Ouma 2012, 216). Most national HE systems operate a hybrid funding model with the trend towards reductions in government subsidies and increases in student fees as well as other forms of income generation (Jungblut and Vukasovic 2017).

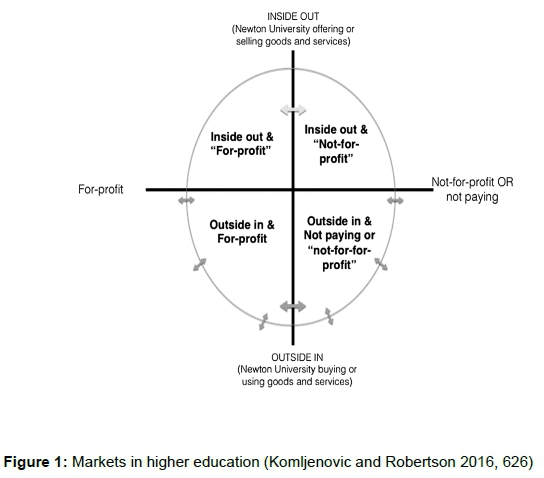

The central aspect of this push toward marketisation was a "range of policy tendencies that can be understood as forms of privatisation [which] are evident in the education policies of diverse national governments and international agencies" (Ball and Youdell 2008, 8). Ball and Youdell distinguish between exogenous and endogenous privatisation in public education. Exogenous privatisation involves "the opening up of public education services to private sector participation on a for-profit basis and using the private sector to design, manage or deliver aspects of public education" (2008, 9); this describes the numerous relationships that have been and continue to be formed with a multiplying range of providers selling goods and services to public universities. Endogenous privatisation in public education, where the language, norms and processes of business are brought into public education, is also of relevance in this study through what has been termed market-making practices. In their case study of an English research-intensive university, Komljenovic and Robertson (2016) have identified the types and nature of "market exchanges" that emerge, with these exchanges leading to a proliferation of new firms with specialist products for sale to universities. These market exchanges involve the university both as a buyer and seller of services with exchanges and services being either for-or not-for profit. The direction of movement of exchanges as well as the profit motive, illustrated in the diagram below, also show hybrid ways in which universities relate to the profit rationale of marketisation. Yet, the question remains how these different models are reflected in the narratives of senior leaders, and what language do they use to portray such hybridity?

Komljenovic and Robertson's (2016) four domains in which market exchanges happen point to the diversity of types of markets and goods that are involved when considering what is meant by marketisation. Of the narratives about these four domains presented, our particular interest is how senior leaders at public universities reflect on those where profits are intended, or at least where income is generated. We have studied this phenomenon with particular focus on unbundling: the process of disaggregating educational provision into its component parts, which may be provided in partnership with external actors (Walji 2018). In this, a university becomes both a buyer and seller in a dynamic marketplace that constitutes an exchange with specialist providers which both buy and sell products from and to universities. Indeed market-making and market exchanges are dynamic, sometimes fragmented and often contested processes (Komljenovic and Robertson 2016). And while authors such as Marginson (2013) and Ntshoe (2004) argue that full commercialisation in HE is not feasible and has not happened entirely in any jurisdiction, as HE is a "regulated quasi-market" (where pure economic imperatives are subsumed through public subsidies, loans, set caps on fees charged and exclusive access to elite institutions), the new terrain of public-private partnerships has presented novel ways of thinking about what constitutes "the core business" of the public university (see Swartz et al. 2018).

In this new light, marketisation can also be understood at a meso level through analysis of what constitutes the goods or products of HE - what educational activities are ascribed exchange value and sold - and who are the actors involved in these market-making activities. Marginson (2018) combines economic and political definitions of public/private goods in HE, offering an analytical framework comprising four quadrants that include both economic and political lenses. In combining economic and political notions of public and market in terms of goods and services offered, Marginson (2018, 331) aims to make "explicit the political choices associated with economic provision", insisting that market-making is social and contextual rather than linear and absolute. Yet in this complex terrain, it is clear that these definitions are shifting in some geographical contexts, such as the two contexts we study. In England and South Africa - which have traditionally public HE systems - there is increasing opening to market players, a diminished public role for HE, and a shift of responsibility for income generation from the whole system to individual institutions. This risks "the non provision of public goods", and while some institutions may be able to maintain a strong public mission, most institutions "must look to their own sustainability" (Marginson 2018, 324). Whether education results in the production (and sale) of "private goods" or "public goods" (or a combination) is a result of HE institutions' reactions to national policies. While there is an inherent market ethos in HE given the notion of a degree as a positional good, the extent to which the university has started to think of itself as a business responsive to an emergent market situation is a point of debate (Marginson 2018; Tomlinson 2018) that this article contributes to.

Amongst the significant literature on the mechanisms and effects of marketisation, there is a long-standing body of critique from both the Global North and South, with the main premise being to what extent public values are eradicated or jeopardised in a marketised sector (e.g. Côté and Allaha 2011; Loughead 2015; Marginson 2013; 2017; Slaughter and Rhoades 2009, and many others). It is posited that marketisation has undermined the emancipatory humanistic principles upon which universities were founded (Bertelsen 1998) as well as the value of social knowledge (Orr 1997), creativity, and critical thinking (Lynch 2006). In the African context, it has been argued that marketisation has led to a decrease in the quality of education (Oketch 2009) and also that it perpetuates the learning divide (Robertson and Komljenovic 2016). What does this shift look like beyond the internal management of universities (Shore and Wright 2016) and what are the interactions between public universities and for-profit market agents? Does the intersection entail boundary work in which universities delineate themselves from businesses? To address these less studied questions, this article explores the perceptions of senior management in HE institutions in South Africa and England regarding their institution's position in this rapidly changing terrain.

METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE

Sixteen interviews were conducted with senior leaders in 2017 at three research-intensive public universities in South Africa and three in England respectively. By senior leaders, we mean those in the senior leadership and management of the university, including the top leaders; different universities use different terminology for such positions. While in our original research we also interviewed senior leaders in teaching-oriented comprehensive (South Africa) and post-1992 (England) universities, based on coding and analysis of our interview data and the desk research of actual partnerships, we realised that when it came to unbundled provision the latter sector had much less exposure to and experience with such partnerships (Swinnerton et al. 2018). For this reason, in this article we focus our attention on leaders in research-intensive universities, each of which has two or more ongoing partnerships with private companies supporting or developing online courses, online education services or Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). We designed qualitative interview schedules that operationalised topics around the alignment of practices and values of public-private partnerships, emerging and contested business models for income generation, and pedagogical imperatives that guide partnerships. Having secured ethical clearance from our own and the other university institutions involved, we carried out the semi-structured interviews. We asked a similar set of questions each time, with the semi-structured format allowing us to probe central topics among all interviewees, while also enabling a level of thematic emergence (Schreier 2014). Interviews were recorded, transcribed, anonymised and coded with the qualitative data analysis software NVivo. The code book was developed by research team members, devising themes from the research literature into smaller analytical categories to reflect complex relations. We coded for emic themes drawn directly from interviewees. We intersected themes on decision-making around partnering as well as emerging business models connections with education.

By exploring institutions in South Africa and the UK we entered the terrain of paired comparisons, "a distinct strategy of comparative analysis with advantages that both single-case and multicase comparisons lack" (Tarrow 2010, 230). As Tarrow has argued, paired comparisons demand an intimacy with context and detail "that inspires confidence that the connections drawn between antecedent conditions and outcome are real" (Tarrow 2010, 239). Yet, instead of looking for a comparative design per se, we allowed the data to show us if more robust comparison by contrast (Tarrow 2010) was needed or were we rather observing two cases of mimetic isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell 1983) in the global field of higher education (Marginson 2008) in which organisations take up certain structural features that they believe are of benefit. Thus, while the two countries have different historical and geopolitical trajectories, and their HE systems' access to financial resources, international researchers, students, and transnational companies are different, our data shows that a small number of research-intensive public universities in both countries experience high interest from international companies and engage with forms of unbundled provision for income generation purposes. On this basis we were open to tracing both small differences and significant similarities in the perceptions of senior managers regarding their work with private companies.

REGULATING THE MARKET "NORM"

It was clear from interviewees in both countries that marketisation has become an integral part of university practices, widely acknowledged, although variably accepted, as part of the HE terrain. The English HE sector has a longer history of regulatory frameworks encouraging marketisation, with the policy environment having been restructured in the early 1980s (Robertson 2010). The UK Government's recent White Paper and Higher Education and Research Bill both aim to decisively open up the HE sector to the market. It was perhaps unsurprising therefore that the marketisation discourse was more widespread amongst the English interviewees. They did, however, observe that the regulatory environment was still fluid; as one respondent said about the public private divide "[it] depends what day you catch the Minister on how they see it, you know" (Senior Manager, England, University E).

In South Africa, the regulatory situation has engaged in a different way with private companies, as the policy environment has explicitly articulated higher education as a public good, with regulation to date designed to prevent the proliferation of those considered to be private "fly-by-night" providers. The new scenario of public universities partnering with private companies to marketise their provision has not received a great deal of formal policy attention. Yet, the view that the involvement of private companies in public university activities would act as a catalyst for change was present in interviews in both countries. In South Africa this was particularly evident in terms of recent political economic crises, particularly the push for universities to gain further revenues in order to afford fee-free education for low income and working class students (see Swartz et al. 2018). In this regard in South Africa, responses indicate that senior leaders were not fundamentally arguing against the market sector being involved but were concerned rather with how policy frameworks should shape the relationship. For those making decisions within universities, the dawning situation was explicit:

"We sat down and looked at the opportunities and possibilities of this whole new scenario and said there is a new reality here, what would it take for us to get involved in a way we would regard as being authentic that would not compromise the way we understand our role and function of a university (Senior Manager, South Africa, University A).

In the English context, it was evident that partnering is growing and decisions are being made on the basis that others in the sector (within the country and beyond) are increasingly engaged in it, hence it had assumed an air of normality:

"I think that even in the last two, even two to three years ago, this type of arrangement wouldn't have been very palatable to many Russell Group universities in the UK. But that's changing for a number of reasons. I think partly it's because there are more commercial partners who are kind of touting their wares, going around to universities showing or demonstrating what they can offer." (Senior Manager, England, University A).

Notably, it was the South African respondents who were concerned about the broader social context, raising questions about whether market actors, especially those from Northern countries could fathom the local context.

"There was some understanding for the South African situation, but not much. I don't think they were quite as involved as we were in that stage with all the discussions around Fees Must Fall [student protests]. We felt it on our campuses, while they were sitting in America and not really feeling it as we were feeling." (Senior Manager, South Africa University R).

While there are disputes about the pervasiveness of market penetration into the public HE sector and the extent to which agendas are shared, there was no questioning of whether the market actors had a role to play. The question was never "if" but "how", with the UK policy frameworks clearly setting out to enable the participation of market actors and the voices of the South African decision makers suggesting its inevitability.

ALIGNING PRACTICES AND VALUES

Senior decision makers at universities in both countries raised issues regarding the alignment of interests, goals and practices and the extent to which market players and HE institutions are guided by different set of rules and purposes. Interviewees in both countries described how their institutions' brand, ranking and values were major determinants in who they worked with and what company they kept. Interviewees also reflected on the difference between public institutions and private companies in terms of engagement as well as in terms of business models. For example, one of the interviewees from a South African HE institution, stated:

"So firstly, a consequence of a market is that the price determines who has access and then if the price goes up access is reduced. That's not the case in our system, because we have a financial aid system, which completely compensates for the price if someone can't afford it, so the price does not determine supply and demand and doesn't determine the distribution of who gets access." (Senior manager, South Africa, University A).

This opinion is echoed in interviews with other respondents in South Africa and England. In their view, and in line with the argument of Marginson (2013), universities are quasi-markets, based on a different set of rules and objectives. They generally felt that there was a fundamental difference between the ways private companies and public universities operate. Interestingly, although this respondent is saying that the logic of the university is different from that of the market, they are using the language of the market to say so, connecting to the idea of market "inevitability" described above.

In England, respondents were at pains to point out that universities could not be wholly subject to private sector practices because they are charities, with the concomitant consequences: as one respondent put it, "university [...] after all is a charity with those charitable purposes" (Senior Manager, England, University C). Another participant observed that being akin to a charity influenced the purpose of income generation, differentiating between profit and surplus:

"There's a business model and we do see this being a profitable venture, just like it needs to be in order to invest basically. In a way we're a charity, so we don't make profit, we make surplus." (Senior Manager, England, University E).

Indeed Marginson (2013, 360) has argued that universities do not compete for market share in their core business of mainstream undergraduate and postgraduate education, but they do compete for "emerging areas of activity and for non-core commercial revenues". The distinction between profit and surplus here marks the university's desire to set its values apart from those associated with the market.

Some respondents were comfortable with appropriating the language of the market if it served the interests of the public university, thus resolving what might have seemed to be a contradiction regarding the role of profits in the public sector.

"A public university to me is basically where any profit from the university is reinvested back into the university and not into the hands of shareholders. I don't think it necessarily requires immense government funding in order to be a public university." (Senior Manager, England, University A).

EMERGING AND CONTESTED BUSINESS MODELS

Whether it is called profit-making or generating a surplus, the issue of income generation is one that universities in both England and South Africa are confronting given that state subsidies have decreased in both countries - it has reduced to 40 per cent of income since 2000 in SA (Cloete 2016), and to 15 per cent since 1992 in the UK (Bolton 2017). What is at stake here is how relationships with private companies can be leveraged to make profits on behalf of and to serve the interests of public universities and what the implications of specific decisions might be.

The interviews suggest that public universities' engagement with the logic and language of the market involves boundaries becoming more fluid between what can be considered a private or a public good as well as regarding who has primary responsibility for the core business of teaching. This fluidity means that there is still a great deal of variety in the nature of the intersection between individual private companies and universities in terms of provision.

In some cases, there is consensus and trust and a high level of alignment. One respondent at an English university perceives the private company as a partner who shares their views:

"I think we're [the private company and us, the public university] quite on the same level here. So, they don't just deem success in terms of profitability, and neither would we. So, student experience is at the heart of everything." (Senior Manager, England, University A).

In this case, the private company, which exists to generate profits, has persuaded the university that its priority is a good or product, the "student experience". This is a case of what Komljenovic and Robertson (2016) (drawing on Çaliçkan and Callon 2010) call pacifying goods, where an intangible is made into a stable and predictable commodity and assigned value - thus the student experience is a commodity agreed on by both parties. In fact, student experience is now measured by Times Higher Education, in its ranking calculation, indicating its status as a pacified good (THE 2017). In the case above, trust and legitimacy has been established in the relationship between the two parties regarding this good.

Such consensus is on one side of the spectrum. On the other, in stark contrast, a South African interviewee said: "I have been to literally hundreds of presentations about products that could be sold to [Research-Intensive University] where the person who is presenting has no idea of our business needs". This respondent is also using the language of the market by referring to the requirements of a public institution as "business needs", and clearly perceiving the institution as a buyer of goods. But although there are numerous sellers, many of them new players, attempting to sell goods and services (an observation made by several interviewees), no relationship of mutual understanding has been formed.

It is not possible to comment on whether these two examples can be considered typical of the two countries where the study was conducted. It may be that, drawing on Komljenovic and Robertson (2016) and referring to Figure 1, where a university is operating in an "inside-out" market relationship as a "seller" and where a partnership has been established and negotiated to enable this, attitudes to market-making are more comfortable than a situation where an institution is a "buyer" as in the "outside-in" quadrant. It is perhaps in the ambiguities of the university and external companies' roles as buyer and seller, and the negotiations between these positions, that tensions can arise.

PEDAGOGICAL IMPERATIVES

While there were differences of opinion regarding whether private actors and universities share agendas, and to what extent they are able to develop working relationships of trust, there was unanimity among respondents regarding the priority of the educational mission. There was consensus across the two sites regarding their criteria for engaging with sellers of services. Both South African and English respondents stressed that their primary concerns were pedagogical:

"I have talked to a lot of the big commercial online providers, but their business model was much more fixed and it didn't necessarily fit my pedagogy drive." (Senior Manager, England, University E).

Indeed, the respondent commented that an expressed shared motivation was a reason that they had worked with a particular provider:

"The reason we signed ultimately with [Name of the Company] in this partnership is they sort of spent quite a lot of time waving their arms around and drawing pedagogy models and I quite liked that, it was nice, it wasn't about business." (Senior Manager, England, University E).

These interactions and intersections are acts of market-making, happening in ways Komljenovic and Robertson (2016, 5) point out are dynamic, diverse and difficult, thus recalibrating and remaking structures, social relations and subjectivities. This is the formation of new kinds of flows fluctuations and negotiations regarding priorities, ideas, practices, foci and intentions. It is in these ways that a convergence occurs of values, cultural shifts and organisational practices, thus reshaping the context within which public sector organisations work. (Ball and Youdell 2008).

TERMS OF ENGAGEMENT

A particular dimension of these negotiations pertains to the terms of engagement. It emerged that there was no established pattern of relationships between private companies and public universities. There were no traditions to fall back on. There were also a range of activities at varying levels of granularity that private companies were involved with when it came to, for example, offering online courses. Such activities included marketing, providing a technical platform, sourcing teachers, course design and assessment, each of which provided as discrete services. Interviewees raised questions about the terms of engagement in relation to their understandings of working with external providers.

The responses to notions of partnership were polarised. On the one hand there were examples of relationships, which, it was implied, were on an equal footing. There was an instance where a respondent expressed great satisfaction with a close partnership where they believe the arrangement to be fair.

"So [Name of the Company] brings the willingness to take risks, they'll share the profit, because which they ought to because if they're taking the risk there has to be a decent return for them, but they also carry the downside risk of having spent a whole load of money and not getting it back on a course which turns out to be a dud." (Senior Manager, South Africa, University A).

This language of partnership was used in both sites, but it was also treated with caution: as a leader at South African University M put it, "So while partnerships are one way to go, one needs to be cautious of the challenges of partnerships and what that entails".

Concerns were also raised, with interviewees being explicitly sceptical of the promises and premise of partnerships. In particular, the quality of private sector involvement was an repeated theme. In England, expressing concern about the role of an external company, one respondent said, "I think we can do a better j ob in a number of ways" (Senior Manager, England, University F).

However, doubts about quality were not the only reason for questioning a partnering relationship. Finances were also posited as a reason not to form an association, especially not in the form of a partnership. In one case, the decision was made not to work with an external partner because of loss of revenue: "we will sacrifice therefore a very significant proportion of the income stream" (Senior Manager, England, University E). This echoes the concerns raised elsewhere by university leaders expressing their desperation to counter reduced state subsidies. The implicit argument here was that the university should offer the services provided by the private actors itself, in order to reinvest all of the "income stream".

At the heart of the relationship between private companies and universities was a tussle and constant negotiation about ownership and agency. Decision makers in universities felt strongly about the issue of control. Interviewees in both locations shared their concerns about prioritising the educational imperative as well as asserting their agency in any relationship. This was expressed in different ways, in one instance financially:

"I think for a traditional university like [name], which is very focused on its reputation and losing its reputation potentially, there's much more control exerted over its main source of revenue, which is education." (Senior Manager, England, University A).

Another respondent expressed an even stronger sense of concern and urgency, arguing that by working with a private company, the educational work of teaching and learning would be turned into a product, which was problematic in itself and which the university would lose control of:

"and you no longer have a control over the quality of the final product. So basically, you're selling a brand and yes, you're selling content, but - but you're selling a brand and I don't think that's academically proper. I just don't." (Senior Manager, South Africa, University C).

It is clear that decision makers are having to manage and navigate which components of provision "belong" to which party, what can acceptably be handed over to a private company, and which aspects should be considered non-negotiable.

For some, the solution has been strong accountability and measures required from the private company:

"So, we're trying to adapt our pedagogies a bit, depending on how students, individual students or programmes best want to be supported, really. The [name of the company] student support services are quite strong, in the sense that they have a service level agreement with them. So, students aren't left more than twenty-four hours without a response to their query." (Senior Manager, England, University A).

In the process, the public university has adopted the language of the market, an example of endogenous privatisation where the language and practices of the market are incorporated into the public sector.

Overall, levels of comfort regarding how close or distant the relationship should be varied a great deal, with some viewing the connection as close, even equal, and several, especially in England, using the language of partnership. Others were more cautious or tentative. On the whole, participants emphasised the importance their role as leaders and decision makers in the university negotiating the terms of engagement with private companies and potential partners. They argued for what Mamdani (2007) refers to as the "soft version" of privatisation in HE, where the priorities of privatisation are set by the public institution, rather than the other way round.

CONCLUSION

It is evident from this research that the negotiations and new relationships being formed with external private companies raise important questions the marketisation of HE itself in South Africa and England today. The interviews indicate how prevalent these kinds of relationships between public universities and private companies already are in HE in both countries. While respondents from public universities expressed concerns about the nature of these relationships, they often employed the language of the market in order to express their doubts. Thus, while marketisation was often seen as an unwilling necessity, particularly in the South African context, it was not questioned as a process in itself. Ironically, even when attempting to differentiate themselves from private businesses, university leaders used the latter's language.

Interviews were explicit about prioritising student learning when choosing whether or not to form relationships as well as with whom to partner or acquire services. In cases in which the university acts as a seller of goods and services, as discussed in the example of student experience above, there were also concerns raised about the implications of this kind of activity for the core business of the institution. Overall, however, the responses show that opinions regarding these changes are mixed and there were varying degrees of ambivalence. Unsurprisingly, no single position emerged regarding profit-making by universities. While some see it as a necessity to maintain the "main" business, such as teaching and research and to compensate for the lack of government funding, others are more sceptical regarding whether working with private companies can and should be an integral part of HE's mission and work.

The variation in responses to these questions provides a useful reminder that regarding the relationship of private companies and public universities cannot usefully be considered as a simple helpful/harmful dichotomy. Given their prevalence, it is necessary to map the kinds of relationships that exist in their multiple dimensions, in order for the engagements between these parties to be better defined and conceptualised in policy terms. In the South African case, where the policy in this area has received less attention than in England, there are real implications for regulations going forward. An analysis of these relationships could also catalyse a necessary review of existing policies in the English context. In both cases these findings draw attention to key issues including transparency, mutual obligations and ownership. Policy principles and regulations will also need to consider the consequences of these engagements for all involved, including students and academics whose daily experience are affected in tangible ways by the new relationships. Interviews with these groups may tell a different story from that of senior leaders and provides a fruitful avenue for future research.

Finally, this research was undertaken prior to Covid19's deep disruption to higher education and the concomitant "pivot online" to remote teaching and learning, yet it pre-empts and rehearses the concerns, ambivalence and negotiations shown here. At a time when major budget crises are slashing the sector, and private sector promotions may seem alluring, additional judicious analyses of the nature of public university-private company relationships are imperative.

REFERENCES

Ball, S. J. and D. Youdel. 2008. Hidden privatisation in public education. Brussels: Education International. [ Links ]

Bertelsen, E. 1998. The real transformation: The Marketisation of higher education. Social Dynamics 24(2): 130-158. [ Links ]

Bolton, P. 2017. Higher education finance statistics. BRIEFING PAPER Number 5440, 20 March 2017. House of Commons Library. [ Links ]

Çaliçkan, K. and M. Callon. 2010. Economization, part 2: A research programme for the study of markets. Economy and Society 39(1): 1-32. [ Links ]

Cloete, N. 2016. University fees in South Africa: A story from evidence. CHET May 2016. https://chet.org.za/resources/sustainable-higher-education-funding-and-fees-south-africa [ Links ]

Côté, J. and A. Allaha. 2011. Lowering higher education: The rise of corporate universities and the fall of liberal education. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Dill, D. D. 2003. Allowing the market to rule : The case of the United States. Higher Education Quarterly 57(2): 136-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-2273.00239 [ Links ]

Dimaggio, P. J. and W. W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48(2): 147-160. [ Links ]

Jungblut, J. and M. Vukasovic. 2017. Not all markets are created equal: Re-conceptualizing market elements in higher education. Higher Education 75(5): 855-870. [ Links ]

Komljenovic, J. and S. L. Robertson. 2016. The dynamics of "market-making" in higher education. Journal of Education Policy 31(5): 622-636. [ Links ]

Levidow, L. 2002. Marketizing higher education: Neoliberal strategies and counter-strategies. In The virtual university? Knowledge, markets and management, ed. K. Robins and F. Webster, 227-248. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Loughead, T. 2015. Critical university: Moving higher education forward. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Lynch, K. 2006. Neo-liberalism and marketisation: The implications for higher education. European Educational Research Journal 5(1): 1 -17. [ Links ]

Marginson, S. 2008. Global field and global imagining: Bourdieu and worldwide higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education 29(3): 303-315. [ Links ]

Marginson, S. 2013. The impossibility of capitalist markets in higher education. Journal of Education Policy 28(3): 353-370. [ Links ]

Marginson, S. 2017. Limitations of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education 44(2): 1-15. [ Links ]

Marginson, S. 2018. Public/Private in higher education: A synthesis of economic and political approaches. Studies in Higher Education 43(2): 322-337. [ Links ]

Mamdani, M. 2007. Scholars in the marketplace: The dilemmas of neo-liberal reform at Makerere University, 1989-2005. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Ntshoe, I. M. 2004. Higher education and training policy and practice in South Africa: Impacts of global privatisation, quasi-marketisation and new managerialism. International Journal of Educational Development 24(2): 137-154. [ Links ]

Oketch, M. 2009. Public-private mix in the provision of higher education in East Africa: Stakeholders' perceptions. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 39(1): 21-33. [ Links ]

Orr, L. 1997. Globalisation and the universities: Towards the "market university"? Social Dynamics 23(1): 42-64. [ Links ]

Robertson, S. 2010. Corporatisation, competitiveness, commercialisation: New logics in the globalising of UK higher education. Globalisation, Societies and Education 8(2): 191-203. [ Links ]

Robertson, S. L. and J. Komljenovic. 2016. Non-state actors, and the advance of frontier higher education markets in the Global South. Oxford Review of Education 42(5): 594-611. [ Links ]

Schreier, M. 2014. Qualitative content analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of qualitative data analysis, ed. U. Flick, 170-183. Los Angeles; London: SAGE Publishing. [ Links ]

Shore, C. and S. Wright. 2016. Neoliberalisation and the "death of the public university". Associazione Nazionale Universitaria Antropologi Culturali (ANUAC). [ Links ]

Slaughter, S. and G. Rhoades. 2009. Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Swartz R., M. Ivancheva, N. Morris and L. Czerniewicz. 2018. Between a rock and a hard place: Dilemmas regarding the purpose of public universities in South Africa, in Higher Education (online first). [ Links ]

Swinnerton, B., M. Ivancheva, T. Coop, C. Perrotta, N. Morris, L. Czerniewicz, A. Cliff and S. Waljil. 2018. The unbundled university: Researching emerging models in an unequal landscape. Preliminary findings from fieldwork in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Networked Learning 2018, ed. M. Bajic et al., 218-226. Networked Learning 2018, 14-16 May 2018, Zagreb, Croatia. [ Links ]

Tarrow, S. 2010. The strategy of paired comparison: Toward a theory of practice. Comparative Political Studies 43(2): 230-259. [ Links ]

Times Higher Education World University Rankings. 2017. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2017/world-ranking [ Links ]

Tomlinson, M. 2018. Conceptions of the value of higher education in a measured market. Higher Education 75(4): 711-727. [ Links ]

Wangenge-Ouma, G. 2012. Public by day, private by night: Examining the private lives of Kenya's public universities. European Journal of Education Part I 47: 213-227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2012.01519.x [ Links ]

Walji, S. 2018. Online learning designs - synchronous and asynchronous models of online learning and how these relate to unbundling. https://unbundleduni.com/blog/ (Accessed 4 May 2018). [ Links ]