Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Literary Studies

On-line version ISSN 1753-5387

Print version ISSN 0256-4718

JLS vol.39 n.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1753-5387/13947

ARTICLE

Unveiling Neocolonialism in Sino-African Relations: Femi Osofisan's All for Catherine

Xunqian Liu

Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. lxunqian@sjtu.edu.cn. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2259-3746

ABSTRACT

This article examines the artistic and political implications of Femi Osofisan's All for Catherine, an adaptation of Cao Yu's play Thunderstorm. Although the dialogue remains largely faithful to the original, the characters, settings, and historical contexts are artfully shifted to the Nigerian cultural context. The original play by Cao Yu primarily offers a profound critique of capitalist society, a sentiment Osofisan carries forward in his adaptation. By analysing the play's postcolonial narrative and its portrayal of China's image, this article provides a literary and textual analysis of African perspectives on Sino-African relations. While China may intend to play a supportive role in Africa, extending its influence and contributing to economic growth, Osofisan's adaptation suggests a more nuanced perspective. It raises concerns about the potential for neocolonialism, where China' s investments might sometimes prioritise its own interests over the genuine development of African nations.

Keywords: Osofisan; Sino-African relations; African theatre; neocolonialism

Introduction

Femi Osofisan, a leading voice in contemporary Nigerian drama, boasts an impressive oeuvre of more than 60 plays since the 1970s (Zapkin 2021). Renowned for illuminating socio-political issues through drama, Osofisan actively contributes to the discourse on African development. He is celebrated as one of the foremost adapters in contemporary theatre (Dunton 2022), with notable examples including Who's Afraid of Solarin? (1978), Tegonni (1994), Wesoo, Hamlet! (2003), and Women of Owu (2006).

In 2013, Osofisan took up a three-month visiting professorship at Peking University. During his visit, Osofisan was invited to tour renowned Chinese playwright Cao Yu's (1910-1996) former residence. Osofisan also had the opportunity to watch Cao Yu's Thunderstorm, one of China' s most important theatrical works (Liu 2015). Echoing a miners' strike plotline in Thunderstorm, on the very day Osofisan arrived home from China, one of the headlines in newspapers at the airport was about a labour strike organised by African employees of a Chinese manufacturing company in Lagos (Cheng 2019, 96). The labour unrest in Lagos was not merely indicative of Nigeria' s internal dynamics but also related to the broader, intricately layered socio-economic exchanges between China and African nations, highlighting the tension between Chinese entrepreneurial pursuits in Africa and local perspectives and necessities.

Osofisan's practised eye recognised the dramatic potential of these overlapping themes. Drawing inspiration from Cao Yu' s Thunderstorm and juxtaposing its narrative with contemporary events in his homeland, Osofisan found a powerful medium to engage Chinese audiences and comment on the multifaceted nature of Sino-African interactions. While there exist several English translations of Cao Yu's Thunderstorm, Osofisan drew from these to relocate the setting from Northern China to Southern Nigeria, transforming the original tragedy between two Chinese families into an equally intense and thought-provoking encounter between a Chinese and a Nigerian family. His innovative adaptation was titled All for Catherine.1

This analysis is built on three foundational arguments. First, within the vast spectrum of global theatrical traditions, Thunderstorm uniquely bridges Eastern and Western narratives, sparking interest in Osofisan' s decision to adapt this particular Chinese play. Secondly, the overarching theme of class struggle, evident in both Thunderstorm and All for Catherine, aligns with Osofisan's recurrent thematic interests. Finally, All for Catherine transcends a simple stage adaptation, offering profound commentary on pressing issues in Sino-African relations (Sautman and Yan 2014) and insight into concerns regarding neocolonialism in China' s activities in Africa and the anti-Chinese sentiment growing among Africans.

Theoretical Foundation and Framework

This article applies Hutcheon's and Sanders's theories to shed light on Osofisan's adaptive strategy, which both honours the narrative integrity of the original and enriches it with culturally specific and pertinent significance. Hutcheon (2012) contends that adaptations are imaginative iterations that, though autonomous, are intricately connected to their source materials via a palimpsestic relationship. Osofisan's version maintains the fundamental aspects of Cao Yu's Thunderstorm-notably the motifs of capitalist exploitation and class conflict-whilst relocating the narrative to the Nigerian socio-cultural context, engendering a unique dialogue between the original work and its adaptation.

In parallel with Julie Sanders's perspective from Adaptation and Appropriation (2016), Osofisan's method resonates with Sanders's notion of appropriation, which extends beyond simple adaptation to encompass substantial transformation. All for Catherine does not just replicate the structure and central conflicts of Thunderstorm; it also seizes the narrative to interrogate neocolonial dynamics, particularly focusing on China's involvement in Africa. This method signifies a purposeful cultural rearticulation rather than a mere transplant. By preserving the original's dialogue and reshaping the characters, settings, and time frame to correspond with the Nigerian setting, Osofisan does more than translate the story's form; he redefines its essence, making it germane to modern discussions of power and influence in a postcolonial African context.

Furthermore, to delve into the nuances of this adaptive process, I invoke the concept of "intertextuality," denoting the intricate interplay and referencing amongst texts (Allan 2022). This concept allows for a nuanced exploration of the congruencies and divergences between Thunderstorm and All for Catherine, enabling an analysis of how Osofisan adeptly manipulates elements from the source material to forge new cultural significance.

Understanding the cultural and literary contexts of both the source text and the adapted work is paramount (Krebs 2012). A thorough examination of Thunderstorm's encapsulation of the socio-political and cultural atmosphere of early twentieth-century China is necessary. Contrasting this with the Nigerian environment in which All for Catherine is embedded is a valuable tool for uncovering the layers of meaning and resonance within Osofisan' s adaptation. It is imperative to highlight the neocolonial undertones present in Osofisan' s work. Concerns about neocolonial tendencies have surfaced against the backdrop of China's burgeoning influence in Africa (Sautman and Yan 2014). As such, this adaptation is not just a creative reinterpretation of a classic play but also a reflection and critique of these global power dynamics.

A review of literature on the general perceptions of China in the West points to a predominantly negative portrayal, associating China with neocolonialism and the ushering in of a new capitalist system in Africa (Sautman and Yan 2016). This representation emphasises the exploitative aspects of China' s involvement in Africa, with both African and Western media often using terms such as "neocolonial" and "neo-imperial" to characterise China and its citizens in Africa (Lumumba-Kasongo 2011). Moreover, China' s approach in Africa, occasionally circumventing global standards established mainly by Western entities like the International Monetary Fund, garners criticism for potentially eroding transparency, governance, and accountability. These concerns, ranging from the overshadowing of African interests (Gadzala 2015, 171-190) to the environmental implications of large infrastructure projects (Juma 2015), paint a complex and frequently contentious image of twenty-first-century Sino-African interactions.

By leveraging these theoretical and methodological frameworks-spanning cross-cultural adaptation, class conflict, and the themes of neocolonialism and globalisation- I aim to develop a comprehensive understanding of how Osofisan' s adaptation both reinterprets and recontextualises Cao Yu' s foundational work. Having laid the groundwork of drama and cultural interchange, my next step involves a practical exploration of these themes through the lens of Thunderstorm and its intersections with Western theatrical traditions.

Thunderstorm and Its Intersection with Western Theatrical Traditions

Cao Yu's four-act tragedy, Thunderstorm, written in 1933, is one of the most important plays in modern Chinese drama. It delves into intricate relationships within and across classes, exploring societal oppression and individual destinies. Rooted in the iconoclastic spirit of the 1920s and 1930s, the themes champion liberation from both familial patriarchy and capitalist exploitation.

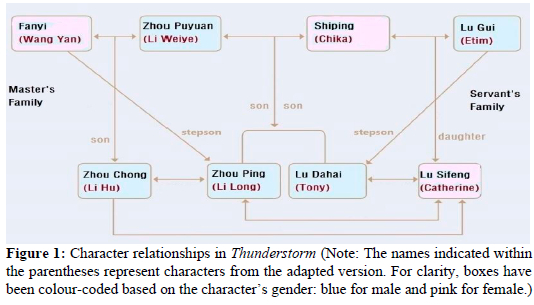

Thunderstorm introduces eight characters (five males and three females) from two families (Figure 1). The story unfolds 30 years ago, when Zhou Puyuan, in his youth, falls in love with the maid Shiping and they have two sons together. However, because Zhou's family pressure him to marry a woman of the same social standing, Shiping is coerced into throwing herself and their newborn son, Dahai, into the river; meanwhile, their elder son, Zhou Ping, is left behind with the Zhou family. Shiping and Dahai are rescued, but Shiping is left destitute and becomes a maid for a different family. She later marries a poor man named Lu Gui, who becomes Dahai's stepfather, and they have a daughter, Lu Sifeng. Zhou Puyuan marries Fanyi, and they have a son, Zhou Chong (Cao 2011).

The Zhou family manages various operations, including a mining operation, which keeps Zhou Puyuan away from home for long periods. This allows Fanyi, Zhou Puyuan's wife, to develop a relationship with Zhou Ping, her stepson. Meanwhile, Zhou Ping falls in love with the young maid Lu Sifeng and gradually distances himself from his stepmother, Fanyi. Fanyi plans to dismiss Lu Sifeng and demands that her mother come take her away. Shiping arrives at the Zhou household and is surprised to encounter Zhou Puyuan. Meanwhile, Dahai, who is working in the Zhou family's mine, comes as a representative of the striking workers to negotiate with Zhou Puyuan, leading to intense conflicts within the Zhou family.

On a stormy night, both families gather in the living room of the Zhou household. Zhou Puyuan, with a heavy heart, reveals the truth and asks Zhou Ping to recognise his mother, half-brother, and half-sister. With this, Sifeng discovers her involvement in an incestuous relationship with her brother and feels immense shame. She runs out of the Zhou residence and is struck by lightning, resulting in her death. Zhou Chong follows her, chasing after Sifeng, and also dies by lightning. Devastated, Zhou Ping takes his own life. Shiping and Fanyi, unable to bear the shock, lose their sanity, while Zhou Puyuan is left alone, consumed by grief and remorse.

The intricate web of relationships and consequences in Thunderstorm is not without familiar antecedents. In fact, its thematic depth is notably reminiscent of the classics from Greek theatre (Lau 1966, 1 -5). Deeply influenced by Greek tragedies, particularly Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, Thunderstorm encapsulates complex human relationships, familial conflicts, and inescapable fate (Ge 2018). Its structure, mirroring the traditional three-act Western drama, with exposition, rising action, climax, and denouement, enhances its international appeal. Its evoking of emotion is reminiscent of Greek tragedies' cathartic outcomes (Wetmore 2011).

This universality facilitated its international appeal; Thunderstorm debuted in Japan in 1935 and was introduced to the English-speaking world a year later as Thunder and Rain by Yao Ke (1905-1991) (Wang 2014). Over its storied history, it has been staged worldwide, gaining accolades and recognition, including from former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, for its ability to transcend cultures (University of Leeds 2014).

Given this backdrop, Osofisan, known for reinterpreting Western tragedies with an African lens, found Thunderstorm a captivating choice for adaptation. Osofisan's portfolio, and especially works such as Women of Owu (2006) and Tegonni: An African Antigone (1994), underscores his skill in grounding Western tragedies within African contexts (Connell 2016). The essence of Thunderstorm, deeply resonant with Greek tragedy, aligns naturally with Osofisan's adaptive approach.

Thunderstorm holds a unique position in the realm of theatre. While it is celebrated as one of China's most significant plays (Ge 2018), its essence is deeply rooted in the core of Western drama. An adaptation based on Thunderstorm offers a golden opportunity not only for Chinese audiences to see a familiar narrative through a new lens but also for African audiences to relate to its universal themes and dynamics. Such a rendition bridges cultural divides and conveys narratives that resonate with both African and Western audiences, fostering understanding and appreciation across different cultures.

Contextualising Osofisan's Adaptation

Adaptive Techniques

Having examined how Thunderstorm intersects with Western theatrical traditions, I turn to the structural changes Osofisan brought to the adaptation. He approached Thunderstorm emphasising simplification for stage performance. Osofisan removed the original prologue and epilogue, segments set a decade after the main storyline featuring Zhou Puyuan's visit to Fanyi, who suffers from a mental illness. Since Thunderstorm's publication, the relevance of these segments has been debated. Many feel they detract from the core narrative. Supporting this sentiment, the play's 1935 Tokyo debut under director Wu Tian excised these parts as "superfluous" (Wu 1935, 34).

Osofisan further simplified the original by turning its four acts into two, condensing both scenes and timelines. The master' s living room becomes the primary setting, incorporating dialogues originally in the servants' quarters in act 3. Instead of the drama spanning a day, it now unfolds from morning to afternoon. This simplification resonates with Grotowski's "poor theatre," which champions minimalism for an authentic connection between performers and audience (Fasoranti 2018; Grotowski 1996), and with the "African total theatre" approach, which integrates various African performance traditions for a cohesive experience (Tugbokorowei 2017). Osofisan' s adaptation borrows from this technique, blending elements from the original acts into a unified narrative within Li Weiye' s villa, offering audiences a comprehensive and coherent experience. By integrating these theatrical principles, Osofisan not only simplifies Thunderstorm's structure but also offers a more intimate and engaging theatrical encounter.

Character Transformations

Transitioning the story from 1920s China to late 1990s Nigeria, Osofisan meticulously reconfigured character relationships. The play morphed from a Chinese-centric family drama into a gripping tale of interactions between a Chinese and a Nigerian family. First, Li Weiye fled China during the Mao Zedong era. Although he found professional success in Africa, he never truly assimilated into African society. He hoped to return to China with his wealth to honour and continue the family legacy (Yang 2016, 413). Li Weiye is depicted as a Chinese capitalist with family roots in mining operations in Jos that span many years. Subsequently, he amassed considerable wealth by managing a rice plantation company, embodying the quintessential foreign capitalist. The conflicts between Li Weiye and his previously unknown son, Lu Dahai, who stands in for the workers, accentuate the labour-capital tensions between Chinese employers and Nigerian employees.

Shiping becomes Chika, a Nigerian woman. She later marries a Nigerian man named Etim, corresponding to the character of Lu Gui in the original script. Her son, Lu Dahai, is re-envisioned as Tony, a labourer with Chinese-African heritage. Lu Sifeng, her daughter, takes on the role of Catherine, a young African maid in Li Weiye's household. Zhou Ping becomes Li Long, a character of Chinese-African descent, while Zhou Chong is rendered Li Hu. In the adaptation, Li Weiye' s subsequent wife is introduced as Wang Yan.

Themes and Narratives

Osofisan introduces pronounced racial tensions in his adaptation. While class differences persist, racial bias takes centre stage. This is evident in Li Weiye' s dynamics with Chika. After his mother arrives in Nigeria, she criticises him for his relationship with Chika, leading to her eviction on New Year's Eve (Yang 2016, 439). Chika later recalls, "You were Chinese, and I was Nigerian. ... You remembered that I was poor and you were a wealthy foreigner" (Yang 2016, 442). This detail underscores racial prejudices against Africans common among some Chinese people.

Osofisan's work is deeply anchored in Nigerian ethnic traditions, bestowing authenticity and cultural depth to characters like Chika. After her abandonment, Chika's response mirrors many Nigerian women's resilience and autonomy. This theme resonates with works such as Flora Nwapa' s Efuru (2013), in which the protagonist chooses independence over a deceitful husband.

Echoing the lived experiences of numerous Nigerian women, Osofisan's characters are frequently portrayed as savvy in business and adept at achieving economic independence, subverting established gender norms. In Women of Owu, Osofisan highlights women's economic autonomy, portraying them as adept traders-a powerful counter-narrative to the traditional marginalisation of women (Götrick 2008). Similarly, Chika carves a niche for herself in Ghana's trading sector (Yang 2016, 399). At the same time, Osofisan does not gloss over the harsh realities many women confront. In order to survive in 1970s Nigeria, Chika had to resort to "begging, vending in motor markets, and even prostitution in military camps" (Yang 2016, 439) Women in Osofisan's works, like Sidi in Morountodun (1982), Iyunloye in Women of Owu, and Tegonni in Tegonni: An African Antigone, grapple with a myriad of challenges, from societal confines to personal hardships. Yet, they consistently rise, resilient and resolute. Following the tragic deaths of Catherine and Li Long, Chika faces the harshness of life with the profound words from the Gospel of Matthew: "Tomorrow will bring its own worries," bringing the story to an abrupt close.

Literary and Textual Analysis

This section analyses the labour-capital conflict theme in both Cao Yu' s Thunderstorm and Osofisan' s All for Catherine. The roots of the labour-capital conflict are traced back to Cao Yu's inspiration, John Galsworthy's (1867-1933) Strife (1907), which presented a workers' strike. Cao Yu's personal connection with Strife-portraying the iron mine director during his high school drama club years (Ta Kung Pao 1929)-adds a layer of authenticity to Thunderstorm.

In Strife, a worker named Luo Dawei passionately champions a strike, only to be betrayed by his fellow miners. A significant number of them deem Luo Dawei too radical, and with the strike increasingly impacting their livelihood, they opt for compromise. This narrative in Strife could be seen as an antecedent to the story of Lu Dahai in Thunderstorm, highlighting similar labour rights themes in plays across different regions.

Cao Yu was awakened to a society steeped in inequalities, where the wealthy and powerful indulged in luxury and excess at the cost of the oppressed working class. This stark disparity kindled an intense disdain for the societal structures and those at their pinnacle. His abhorrence was so deep that he infamously stated, "I would rather see its destruction, even at the cost of my own life" (Wang 1979, 40).

As Lan (2019) points out, Cao Yu masterfully weaves the theme of class conflict into the Zhou family' s saga, contrasting their personal anguish against the vast backdrop of historical class struggles, thereby heightening its societal impact. Dahai, the overlooked second illegitimate son raised in a working-class milieu, symbolises this clash. Unaware of his lineage, he labours in the coal mines, which, unknown to him, are owned by his biological father, Zhou Puyuan. He directly experiences his father's despotic actions, such as denying injured workers their due compensation and supporting the violent suppression of the miners' protests. As tension mounts and a strike unfolds, Dahai rises as the voice of the miners, leading to a consequential confrontation with Zhou Puyuan that merges personal strife with the broader conflict of class.

Dahai's ascent as a leader among the miners symbolises the burgeoning potential for a proletarian revolution, echoing one of the central tenets of orthodox Marxist theory: the working class' s capacity to unite and challenge their oppressors. From an orthodox Marxist perspective, family dynamics in a capitalist society mirror the larger scale of capitalist exploitation and class betrayal. Zhou Puyuan, embodying the dual roles of family patriarch and capitalist mogul, inadvertently sets the stage for the ruin or alienation of his sons, Dahai and Zhou Chong.

This analysis also applies to All for Catherine. In the adapted work, Li Weiye is portrayed as a Chinese capitalist engaged in mining operations in Jos. Later, he accumulates significant wealth by managing a rice plantation company. He personifies a typical foreign capitalist. The conflicts between Li Weiye and his unknown son, Tony (representing the workers), highlight the labour-capital contradictions between the Chinese bosses and Nigerian workers. The dialogue between Tony and his sister, Catherine, presents a stark depiction of the tensions between the capitalist bosses and the working class:

TONY (bitterly): Look, most of these foreign employers here, especially the Chinese like this Mr. Li, are up to no good. I've seen enough of their doings at the plantation these past few years to know them very well. They pretend they've come to help us, but they're only out to fleece us. Oh, I hate them.

CATHERINE: And what are these things you've seen?

TONY: Don't tell me you're blind, Catherine! Take even this house, this magnificent house! Will you say you don't know that it was built with the blood of workers crushed at their rice mills!

CATHERINE: Mr. Li is giving jobs to hundreds of unemployed. Every year he offers scholarships to several of our desperate youths. So what's wrong with it if he builds himself a decent home?

TONY: Of course he can afford to play the philanthropist. That's what they all do, isn't it, these rich expatriates?

CATHERINE: Mr. Li is different, can't you see? You especially! On dad's intervention, he gave you a job-

TONY: To salvage his conscience, isn't it? These grand gestures, after working so many to death! But do you see him living among us, among our people? Never! They build their separate estates, these glittering new mansions, and put a high fence round it, because they despise us!

CATHERINE: And our own people, the Nigerians too who live in these same estates?

TONY: Are no different dear sister! It isn't the colour of their skin I'm talking about! It's the cynical exploitation of the common people like you and me; the swindle that goes on with the collusion of our governments in the name of creating employment. All the big people are in the racket, whether black or white. It's the few rich against the powerless masses. (Cheng 2019, 96-97)

Tony's fervent criticisms of Li Weiye underscore the ingrained clash between labour and capital, which Osofisan stresses more than Cao Yu, emphasising the global reach of this conflict in line with a Marxist perspective. Osofisan is known for his Marxist-inspired works, emphasising political commitment and a vision rooted in societal transformation (Ajidahun 2022). Adeseke (2022) and Osanyemi, Iwuanjoku, and Awotayo (2018) affirm Osofisan's Marxist identity, underscoring his advocacy for the marginalised through his theatrical works.

In a related dialogue, Catherine alludes to an aspect of the Chinese government' s soft power strategy: utilising educational exchanges as a diplomatic instrument. The Chinese government has been actively enticing African students to study in China by offering them generous scholarships (Haugen 2013). This particular approach led Catherine to view Li Weiye in a somewhat positive light. Serving as an intermediary between the Chinese and Nigerian cultures, her portrayal presents a multifaceted perspective on their relationship. The play respects this complexity, steering clear of stereotypes:

Tony: No, it's all fake. You forged this document [referring to the agreement for resuming work] to deceive us. All the workers witnessed their fellow brethren being shot by your security personnel-30 of them! You know! They cannot ... they cannot submit without receiving any compensation. No! You forged this document, you despicable, filthy swindler! (Yang 2016, 444)

The fervour in Tony' s speech, especially his use of potent terms such as "despicable, filthy swindler," not only emphasises the depth of his emotions but also evokes strong reactions from the audience, making them question the morality of the capitalist elite. For example, he states "you rich people, whether Chinese or Nigerian, will go to any extent to make money, no matter how dirty the means are. Stealing, robbing, killing" (Yang 2016, 445).

This dialogue from the character Tony encapsulates a Marxist critique of class and the dynamics of power, reflecting the themes commonly found in Osofisan's works. Here, Tony dismisses race as the primary factor of division, instead highlighting class exploitation as the pervasive issue. His words underscore the complicity between governments and the wealthy elite in perpetuating social inequality, suggesting a global solidarity among the oppressed, irrespective of race.

In academic terms, Tony' s monologue resonates with the principles of Marxist theory, which holds that societal structures are primarily based on economic foundations- specifically, the modes of production and the relationships that they entail. Osofisan, known for his Marxist leanings (Adeseke 2022; Osanyemi, Iwuanjoku, and Awotayo 2018), explores the notion that the true divide is not along racial lines but rather class lines, with a focus on the bourgeoisie (the few rich) and the proletariat (the powerless masses).

This perspective aligns with scholarly analysis of Osofisan's work, where his characters frequently confront and contest the socio-economic structures that marginalise them (Ajidahun 2013). For instance, in Morountodun, Osofisan portrays the struggles of the underprivileged against a backdrop of economic exploitation and political corruption. The "cynical exploitation" and "swindle" mentioned by Tony can be linked to the concept of false consciousness (Mason 2020), a term used by Marxists to describe the ways in which the ruling class (the bourgeoisie) imposes its worldview on the proletariat, so they become complicit in their own oppression.

The "collusion of our governments" that Tony talks about reflects Osofisan's recurring theme of critiquing the postcolonial state for betraying the revolutionary ideals that were supposed to bring freedom and equality to the masses. The notion of "the few rich against the powerless masses" ties in with scholarly conversations around Osofisan's dramaturgy, which frequently depicts a society divided not just by wealth, but by the access to means of production and the perpetuation of class-based injustice (Obasi 2013).

In Osofisan's narrative, Catherine stands out as more than just a bridge between two cultures, rather offering a nuanced view of Sino-African relations and as a complex character in her own right. The line spoken by Li Hu, "She is simply the best girl in the world. She has a heart of gold, knows how to enjoy life, is understanding, and recognizes the importance of hard work" (Yang 2016, 412), summarises Catherine's virtues. However, the most telling part of Li Hu' s description is when he says, "Most importantly, she is not one of those Nigerian girls from the upper echelons called 'ajebota.'" The term "ajebota" is indigenous Nigerian slang, referring to privileged Nigerians who have lived a sheltered and affluent life. Her distinction from the "ajebota" by Li Hu is significant. It not only highlights her character traits but also comments on the privileged class's possible detachment from labour-capital issues.

Li Hu distinguishes Catherine from the "ajebota," an upper-class group within Nigerian society, while Tony points out the morally questionable actions of the rich, regardless of whether they are Chinese or Nigerian. Tony's statement underscores a universal critique of the sometimes unscrupulous lengths the wealthy might go to in order to accumulate more wealth. By not restricting this criticism to a particular nationality but extending it to both Chinese and Nigerians, the play indicates that the negative consequences of unrestrained capitalism are not confined to one culture. Li Hu and Tony provide valuable insights into the socio-economic intricacies of Nigerian and Chinese cultures. The play invites audiences to recognise universal patterns of exploitation by highlighting the tactics of the wealthy common across both cultures.

China's Engagement in Africa: What Do We See?

Hutchinson (2006, 208) notes that "one of the ways Osofisan engages with recognizable socio-political realities of contemporary Africa is by situating his plays clearly in the context of the post/neocolonial. The plays are framed by events in history that Osofisan sees as profoundly influential on Nigeria's current situation." The term "neocolonialism" refers to the ongoing economic, political, and cultural influence exerted by former colonial powers over their former colonies or other developing countries. It describes a situation in which former colonial powers, often supported by transnational corporations, maintain dominance over the economies of developing nations through various means, including foreign aid, debt, trade agreements, and investment. Neocolonialism can result in the exploitation of resources and labour, the perpetuation of unequal power dynamics, and the persistence of poverty and underdevelopment in previously colonised countries (Halperin 2023). Transnational corporations exert significant economic and political influence and are often criticised for their involvement in neocolonial practices, contributing to the exploitation of natural resources and labour in developing countries, often prioritising profits without due consideration for local environmental and social concerns.

Critics argue that China's investment in Africa can be classified as a form of neocolonialism (Mlambo, Kushamba, and Simawu 2016). They contend that China's motivations for investing in Africa primarily revolve around securing resources and economic influence rather than genuine concern for Africa's development. Nigeria, in particular, has been impacted by what is perceived as Chinese neocolonialism; Chinese investors have permeated various sectors, assuming diverse roles such as food vendors, second-hand clothes dealers, and construction site labourers. This influx of Chinese workers has yielded significant profits for investors while displacing local businesses. This has led to a growing sense that Chinese investors are gradually taking control of strategic sectors of the Nigerian economy, intensifying the perception of neocolonialism (The Sun 2022).

The intricate relationship between China and Africa has been a focal point of criticism and literary exploration (Thornber 2016). Artistic expression such as Femi Osofisan's All for Catherine and NoViolet Bulawayo's We Need New Names offers insight into the growing anti-Chinese sentiment among Africans. Bulawayo's novel, We Need New Names, portrays Zimbabwean-Chinese relations as heavily favouring China and exploitative towards Zimbabwe (Musanga 2017). The novel characterises China's engagement primarily in the construction and infrastructure development sector and offers the striking statement that "China is a red devil looking for people to eat so it can grow fat and strong" (Bulawayo 201 3, 47). The dialogues within the novel illustrate China's exploitation of Africa's manufacturing capabilities and extraction of its resources without substantial benefits accruing to Africa. Consequently, China is perceived as contributing to Africa's underdevelopment and deindustrialisation. "The fat Chinese man" in the novel is also depicted as engaging in promiscuous behaviour, as "two black girls" emerge from his tent (Bulawayo 2013, 45). This plot echoes Osofisan's tragic depiction of Chika, who was humiliated by Li Weiye. Similar themes recurring in different authors' works accentuate their relevance to modern African society. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Americanah (Adichie 2014), Chinese oil companies, much like other foreign oil firms, are portrayed as riffraff (Adichie 2014, 581).

China has come under scrutiny for its reliance on Chinese labour at the expense of local workers (Hillman and Tippett 2021). This is further exacerbated by the perception of some Chinese individuals that African workers might be less diligent, accompanied by an apparent lack of respect for African cultural practices. Moreover, instances have been reported of Chinese companies making discriminatory remarks towards local employees, reflective of a bureaucratic and condescending managerial approach (Tang 2011). In All for Catherine, factory owner Li Weiye sees African workers as indolent, manipulative, and devoid of loyalty. Statements such as "These workers have no loyalty to their bosses," and, "Ask most of the bosses here, and they will tell you that Black people are lazy and untrustworthy!" highlight this mindset. Phrases like "intentionally sabotage" indicate a profound distrust. Such perceptions are echoed by various Chinese factory owners (Sautman and Yan 2014; Yang 2016). Osofisan's initial manuscript presented even more pronounced racial prejudice. Osofisan revised his adaptation of Thunderstorm five times, each time sharing it with his Chinese students, peers, and friends to gather their feedback. In response to their perspectives, he excised derogatory remarks such as those alluding to "degenerate Nigerian youths" and "lazy, troublesome, thieving Nigerians" (Cheng 2019, 106).

The exploitation as well as mistreatment of African workers by Chinese corporations and capitalists is not primarily rooted in racial prejudice. Rather, it mirrors the domestic exploitation of Chinese labourers. Influenced by Confucian values, Chinese workers have traditionally been conditioned to exhibit behaviours that align with high power distance and collectivism. Specifically, they tend to be compliant, show respect for authority, and prioritise collective harmony even at personal cost (Hofstede 2001). Confucian values emphasise respect for authority, familial loyalty, and collective harmony. This deeply ingrained ethos has over the centuries shaped labour attitudes in China, leading to a work culture of compliance and sacrifice for the greater good. This ethos often leads employees to avoid voicing individual concerns, delivering maximum output at minimal cost. China' s immense population and competitive job market further pressure workers to accept demanding jobs and extended hours. In Chinese culture, familial responsibility often also trumps personal needs, leading many to believe that their primary duty is to provide for their families, even if doing so entails personal sacrifice.

The German sociologist Max Weber (2001) posits in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism that people's actions are dictated by their beliefs and values. Protestants strive to validate themselves as God' s chosen through hard work and wealth accumulation. In the Chinese context, they can be perceived as "family-centric Protestants." They endure hardships and often send a substantial portion of their income back home. Even for those yet to have children, saving money is geared towards future family formation (Tang 2011). Factory owners can take advantage of this orientation to achieve higher productivity at reduced cost.2

When transported overseas, especially in African factories, this work ethic can sometimes lead to contention. Researchers have interviewed management in African factories, where a manager lamented Tanzanian workers spending their wages on alcohol instead of saving. This manager tried persuading workers to save or to give to their families, believing it was a form of care-typical of traditional Confucian values (Tang 2011). These cultural differences can lead to racial bias. For instance, on the Chinese short-video platform Douyin there are videos claiming "Chinese in Africa can quell local workers' strikes with just a couple of moves" or "African workers are inherently lazy; once a Chinese boss takes over, everything becomes militarised." Such content both reinforces misconceptions among some Chinese viewers and fuels the arrogance of Chinese online nationalists. Drawing from China's investments in Africa and the narrative of Chinese individuals becoming bosses in Africa, these nationalists amplify nationalistic sentiments, connecting the supposed "laziness" of Africans to their race. This conflation is further weaponised through racially discriminatory rhetoric, leading to derogatory comments and insults.3

Chinese racial stereotypes have long portrayed Africans as impoverished, lazy, and backwards, aiming to foster a sense of ethnic superiority (Liu and Deng 2020). Faced with the perceived power disparity with Western nations, some Chinese people have resorted to discriminating against Africans (Visser and Cezne 2023). While Chinese netizens (i.e., online nationalists) do not unanimously support China's trade and investment activities in Africa, many derive a sense of national pride from China's engagement in African affairs. They regard China as Africa's saviour, and this self-proclaimed heroic identity is reflected in various forms of Chinese media, such as posters, television shows, movies, and newspapers (Suglo 2022). Despite the prevalence of these online narratives, Chinese scholars and mainstream media have paid little attention to these misrepresentations, as observed by the author. In this context, Osofisan' s text can be seen as a significant window to the nuances of China' s engagement in Africa, challenging these simplistic and potentially harmful stereotypes.

Theatre as a Mirror: Reflecting on Sino-African Relations

While China's official messaging has consistently emphasised its friendly relations with Africa, the reality is far more complex. There exists a gap between how China shapes its own image and its actual impact in Africa (Lumumba-Kasongo 2011). This article argues that Osofisan' s play, All for Catherine, serves as a call for reflection and awareness among Chinese nationals. By leveraging the prominence of Cao Yu's Thunderstorm, which is regarded as China's foremost theatrical work, Osofisan seeks to encourage Chinese nationals to take note of labour issues in Africa and the growing anti-Chinese sentiment among Africans, reminding them that the official portrayal of Chinese actions in Africa is not the whole story. From this perspective, All for Catherine shines a light on literature as a conduit for the exploration of complex social and political issues that transcend cultural and national boundaries.

Creative writers may incorporate social problems into their work to bring attention to them and foster awareness of potential solutions. Osofisan's plays emphasise the social responsibility of the playwright; he has sought to make the theatre reflect the problems of Nigerian society to explore social issues (Goff and Simpson 2007; Owonibi 2014). With the retelling of Cao Yu' s Thunderstorm, Osofisan transitions from a primary emphasis on Nigeria's internal issues to articulating a Nigerian viewpoint on global matters (Zapkin 2021). The themes of new colonialism and racial discrimination are not confined to Nigeria' s internal issues but reflect broader concerns applicable to the entire African continent.

All for Catherine provides a spur to reflection, dialogue, and an understanding of the complexities of African-Chinese relations. Through the power of drama, it invites audiences to critically examine their beliefs and biases, fostering a more inclusive and empathetic society. Osofisan offers his Chinese audience an opportunity to transcend the narrative of their own "Third World people's unity" and genuinely explore the mutual perceptions between the people of China and Africa.

Cao Yu, much like his contemporaries in Chinese theatre, was at the forefront of the "realist drama" movement in the 1930s, championing the belief that drama should not only mirror societal events but also serve as a platform for social critique. Thunderstorm prominently showcases the central theme of class conflict, which forms the ideological core of the play (Lan 2019). All for Catherine resonates with this spirit. However, while Osofisan employs drama to dissect societal issues, some modern Chinese scholars avoid such critical examination, instead hewing towards the official narrative of Sino-African amity presented by the Chinese government. Some scholars dismiss Osofisan's adaptation as a mere misinterpretation in the realm of Sino-African literature (Cheng 2019; Zhu 2022), possibly to sidestep contentious implications or align their literary research more closely with official viewpoints.

The core social resonance of Thunderstorm is rooted in its incisive critique of early twentieth-century Chinese capitalist society. Drawing from the societal challenges and the dominant intellectual trends of his time, Cao Yu skilfully integrated Marx's notion of class struggle to delineate social dynamics in his work (Lan 2019). Such profound societal reflections and a keen critical stance likely resonated with Osofisan and added motivation for his adaptation (Adiele 2021). Intriguingly, after the 1980s, renditions of Thunderstorm showcased in China began to downplay its emphatic themes of class antagonism and capitalist criticism. In the wake of the Mao Zedong era, as "reform and opening" initiatives took hold during the 1980s and 1990s, intellectual dialogue veered towards dissecting feudalism, overshadowing capitalist critiques. Consequently, numerous interpretations of Thunderstorm excluded the narrative arc of Lu Dahai and the confrontations between workers and capitalists. This article contends that Osofisan's adaptation of Thunderstorm highlights the core essence of the play, faithfully carrying forward Cao Yu's creative spirit, rooted in Osofisan's conviction that dramatists can drive social change.

Conclusions

Femi Osofisan's All for Catherine offers profound cultural commentary on the dynamics of neocolonialism and China' s engagement in Africa. By adapting Cao Yu' s Thunderstorm within the socio-cultural context of Nigeria, Osofisan effectively preserves the core essence of the original-a reflection on capitalist exploitation and class conflicts-while infusing it with a Nigerian identity. This transformation not only honours the original' s narrative integrity but also offers a novel lens to explore and interpret the themes in Thunderstorm within an African framework. Instead of radically altering the plot or dialogues, Osofisan meticulously re-contextualised the play's characters, settings, and temporal backdrops, embedding it within the socio-cultural fabric of Nigeria. The settings shift from early twentieth-century China to a corresponding period of economic and social shifts in Nigeria. This change in contexts provides fresh interpretative layers to the dialogues and actions, even if they remain textually faithful to the original.

The works of African writers like Osofisan and Bulawayo challenge the benign development narrative that China often promotes, highlighting the prevalence of scepticism towards China's intentions in Africa that is rooted in perceived economic exploitation and power imbalance. Chinese investments, characterised by specific practices and economic ambitions, have sparked debates regarding whether Chinese activities in Africa truly benefit African development or the local communities. This narrative speaks to the contrast between China's self-image of proud benevolence in Africa and the perception held by many Africans.

Another layer of complexity is added by the response of modern Chinese scholars, who frequently adopt the official narrative of Sino-African camaraderie, avoiding deeper socio-critical examinations (Cheng 2019; Liu 2015; Zhu 2022). The reluctance to confront or even acknowledge the challenging facets of this relationship, as portrayed in works such as All for Catherine, underscores a potential disconnect between this construal and the reality of the situation, indicating a need for more open dialogue. Drama and literature can be potent mediums to facilitate such discourse. They not only offer reflections on prevailing socio-political issues but also have the power to shape perceptions and foster cross-cultural understanding by dint of their popularity. Osofisan's adaptation of a Chinese classic stands as a testament to this ideal.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Machel Bosman for her proofreading assistance on this article. Additionally, this research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 22CDJ003.

References

Adeseke, A. E. 2022. "Confrontation as Means for Societal Changes: A Marxian Approach to Femi Osofisan's The Chattering and the Songs'" IJARIE: International Journal of Advance Research and Innovative Ideas in Education 8 (5): 410-418. https://ijariie.com/FormDetails.aspx?MenuScriptId=217065 [ Links ]

Adichie, C. N. 2014. Americanah. New York: Anchor Books. [ Links ]

Adiele, P. O. 2021. "Deconstructing Marxist/Revolutionary Labels in Femi Osofisan's Plays." Journal of Language, Literature and Communication 2 (1): 210-223. [ Links ]

Ajidahun, C. O. 2013. "Femi Osofisan Tackles Graft and Corruption: A Reading of His Socially Committed Plays." Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 50 (2): 111-123. https://doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v50i2.8 [ Links ]

Ajidahun, C. O. 2022. "Sophocles's Antigone and Osofisan's Tegonni: A Comparative Analysis." Imbizo 13 (2): 1-17. https://doi.org/10.25159/2663-6565/9708 [ Links ]

Allan, G. 2022. Intertextuality. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bulawayo, N. 2013. We Need New Names. New York: Little, Brown and Company. [ Links ]

Cao, Y. 2011. Leiyu [Thunderstorm]. Xi'an: Shaanxi shida chubanshe. [ Links ]

Cheng, Y. 2019. "History, Imperial Eyes and the 'Mutual Gaze': Narratives of African-Chinese Encounters in Recent Literary Works." In Routledge Handbook of African Literature, edited by M. Adejunmobi and C. Coetzee, 93-109. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315229546-7 [ Links ]

Connell, J. M. 2016. "The Place of Greek Tragedy in African Drama." Journal of Southern African Studies 42 (1): 171-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2016.1126463 [ Links ]

Dunton, C. 2022. "Femi Osofisan and the Process of Adaptation." Journal of the African Literature Association 16 (1): 181-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/21674736.2021.2023419 [ Links ]

Fasoranti, A. O. 2018. "Interrogating Abdulrasheed Abiodun Adeoye's 'Neo-Alienation' Directorial Style in the Productions of The Smart Game and The Lion and the Jewel." Humanitatis Theoreticus Journal 1 (1): 1-8. [ Links ]

Gadzala, A. W., ed. 2015. Africa and China: How Africans and Their Governments Are Shaping Relations with China. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Ge, L. 2018. "Cao Yu's Plays and Thunderstorm."In Routledge Handbook of Modern Chinese Literature, edited by M. D. Gu, 194-204. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315626994-16 [ Links ]

Goff, B., and M. Simpson. 2007. "History Sisters: Femi Osofisan's Tegonni: An African Antigone." In Crossroads in the Black Aegean: Oedipus, Antigone, and Dramas of the African Diaspora, edited by B. Goff and M. Simpson, 321-364. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/book/2764/chapter/143272803 [ Links ]

Götrick, K. 2008. "Femi Osofisan's Women of Owu: Paraphrase in Performance." Research in African Literatures 39 (3): 82-98. https://doi.org/10.2979/RAL.2008.39.3.82 [ Links ]

Grotowski, J. 1996. "For a Total Interpretation." World Theatre 15 (1): 17-20. [ Links ]

Halperin, S. 2023. "Neocolonialism." Encyclopedia Britannica, August 2, 2023. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/neocolonialism

Haugen, H. 0. 2013. "China's Recruitment of African University Students: Policy Efficacy and Unintended Outcomes." Globalisation, Societies and Education 11 (3): 315-334. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2012.750492 [ Links ]

Hillman, J., and A. Tippett. 2021. "Who Built That? Labor and the Belt and Road Initiative." Council on Foreign Relations, July 6, 2021. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/blog/who-built-labor-and-belt-and-road-initiative

Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Hutcheon, L. 2012. A Theory of Adaptation. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203095010 [ Links ]

Hutchinson, Y. 2006. "Riding Osofisan's Another Raft through the Sea of Nigerian History." In Portraits for an Eagle: Essays in Honour of Femi Osofisan, edited by S. Adeyemi, 250-215. Bayreuth: Bayreuth African Studies. [ Links ]

Juma, C. 2015. "Afro-Chinese Cooperation: The Evolution of Diplomatic Agency." In Africa and China: How Africans and Their Governments Are Shaping Relations with China, edited by A. W. Gadzala, 171-190. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Krebs, K. 2012. "Translation and Adaptation-Two Sides of an Ideological Coin?" In Translation, Adaptation and Transformation, edited by L. Raw, 42-53. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Lan, F. 2019. "From Thunderstorm to Golden Flower: Politico-Economic Conditions of Adaptive Appropriation." Comparative Literature: East and West 3 (1): 53-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/25723618.2019.1586082 [ Links ]

Lau, J. S. M. 1966. "Tsao Yu, The Reluctant Disciple of Chekhov and O'Neill: A Study in Literary Influence." PhD diss., Indiana University. [ Links ]

Liu, D. 2015. "Femi Osofisan's Africa, Literature, and China." Peking University, December 8, 2015. Accessed June 6, 2023. http://www.oir.pku.edu.cn/info/1037/2782.htm

Liu, T., and Z. Deng. 2020. "'They've Made Our Blood Ties Black' : On the Burst of Online Racism towards the African in China's Social Media." Critical Arts 34 (2): 104-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1717567 [ Links ]

Lumumba-Kasongo, T. 2011. "China-Africa Relations: A Neo-Imperialism or a Neo-Colonialism? A Reflection." African and Asian Studies 10 (2-3): 234-266. https://doi.org/10.1163/156921011X587040 [ Links ]

Mason, A. 2020. "False Consciousness: Political Philosophy." Encyclopedia Britannica, March 4, 2020. Accessed November 1, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/false-consciousness

Mlambo, C., A. Kushamba, and M. B. Simawu. 2016. "China-Africa Relations: What Lies Beneath?" The Chinese Economy 49 (4): 257-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2016.1179023 [ Links ]

Musanga, T. 2017. "Perspectives of Zimbabwe-China relations in Wallace Chirumiko's 'Made in China' (2012) and NoViolet Bulawayo's We Need New Names!" In "China-Africa Media Interactions: Media and Popular Culture Between Business and State Intervention," edited by A. Jedlowski and U. Röschenthaler, special issue, Journal of African Cultural Studies 29 (1): 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2016.1201654 [ Links ]

Nwapa, F. 2013. Efuru. Long Grove IL: Waveland Press. [ Links ]

Obasi. N. T. 2013. "The Limitations of the Marxist Ideals in the Plays of Femi Osofisan: A Study of Once upon Four Robbers and Morountodun." Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 3 (9): 36-41. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234673531.pdf [ Links ]

Osanyemi, T. A. S., R. E. Iwuanjoku, and F. B. Awotayo. 2018. "Interface Between History and Drama and Nation Building: A Marxist Reading of Femi Osofisan's Morountodun!" Bulletin of Advanced English Studies 1 (1): 111-118. https://doi.org/10.31559/BAES2018.LL9 [ Links ]

Osofisan, F. 1978. Who's Afraid of Solarin? Ibadan: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

Osofisan, F. 1982. Morountodun. Lagos: Longman. [ Links ]

Osofisan, F. 1994. Tegonni: An African Antigone. Ibadan: Opon Ifa. [ Links ]

Osofisan, F. 2003. Wesoo, Hamlet! Ibadan: Opon Ifa. [ Links ]

Osofisan, F. 2006. Women of Owu. Ibadan: University Press. [ Links ]

Owonibi, S. E. 2014. "African Literature and the Re-Construction of Womanhood: A Study of Selected Plays of Femi Osofisan." Mgbakoigba: Journal of African Studies 3: 88-98. [ Links ]

Sanders, J. 2016. Adaptation and Appropriation. 2nd ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315737942

Sautman, B., and H. Yan. 2014. "Bashing 'the Chinese': Contextualizing Zambia's Collum Coal Mine Shooting." Journal of Contemporary China 23 (90): 1073-1092. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2014.898897 [ Links ]

Sautman, B., and H. Yan. 2016. "The Discourse of Racialization of Labour and Chinese Enterprises in Africa." Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (12): 2149-2168. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1139156 [ Links ]

Suglo, I. G. D. 2022. "Visualizing Africa in Chinese Propaganda Posters 1950-1980." Journal of Asian and African Studies 57 (3): 574-591. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211025807 [ Links ]

Sun. 2022. "How China Is Re-colonising Nigeria." March 2, 2022. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://sunnewsonline.com/how-china-is-re-colonising-nigeria-2/

Ta Kung Pao. 1929. "The Nankai New Drama Troupe Is Staging a New Production of 'Strife'." [In Chinese.] October 24, 1929.

Tang, X. 2011. "Laziness and Diligence from the Perspective of Cultural Conflict." [In Chinese.] Beijing Cultural Review 4: 46-50. [ Links ]

Thornber, K. L. 2016. "Breaking Discipline, Integrating Literature: Africa-China Relationships Reconsidered." Comparative Literature Studies 53 (4): 694-721. https://doi.org/10.5325/complitstudies.53.4.0694 [ Links ]

Tugbokorowei, M. U. E. 2017. "Total Theatre Aesthetics on Stage with Temienor Tuedor' s To Cast a First Stone. " Scene Dock: Journal of Theatre Design and Technology 2 (3): 28-47. [ Links ]

University of Leeds. 2014. "Cao Yu: Pioneer of Modern Chinese Drama." University of Leeds, Bilingual text of the exhibition. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://stagingchina.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2014/02/Bilingual-Cao-Yu-exhibition-text.pdf

Visser, R., and E. Cezne. 2023. "Racializing China-Africa Relations: A Test to the Sino-African Friendship." Journal of Asian and African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096231168062

Wang, B. 2014. "Cao Yu and the Cross-Cultural Dissemination of Thunderstorm!" [In Chinese.] Shanghai Theatre 10: 50-52. [ Links ]

Wang, Y. ed. 1979. "Cao Yu tan Leiyu" [Cao Yu Talked about Thunderstorm]. Renmin xiju 3: 40-47. [ Links ]

Weber, M. 2001. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wetmore, K. J. 2011. Review of The Columbia Anthology of Modern Chinese Drama, edited by Xiaomei Chen. Journal of Asian Studies 70 (4): 1114-1116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911811001756 [ Links ]

Wu, T. 1935 "Leiyu de Yanchu" [Performance of Thunderstorm]. Zawen [Essays] 2: 34. [ Links ]

Yang, M. 2016. All for Catherine. In China Africa Research Review [In Chinese], edited by A. Li, 397-456. Beijing: Social Scientifics Academy Press. [ Links ]

Zapkin, P. 2021. "Femi Osofisan' s Evolving Global Consciousness in Four Adaptations. " Modern Drama 64 (4): 478-500. https://doi.org/10.3138/md.64-4-1044 [ Links ]

Zhu, Z. 2022. "Misconceptions and Development Prospects in Sino-African Literary Exchange: A Study of the Adaptation of The Thunderstorm in Nigeria." [In Chinese.] Literature, History and Philosophy 6: 138-149. http://caod.oriprobe.com/articles/64279810/zhong_fei_wen_xue_de_jiao_liu_wu_qu_yu_fa_zhan_yua.htm [ Links ]

1 Femi Osofisan's adapted version of All for Catherine has not been independently published. This article relies on the Chinese translation by Mengbin Yang, as included in the China-Africa Research Review (Yang 2016).

2 Chinese companies operating overseas often employ Chinese workers as a strategy to reduce labour costs. When stationed abroad, these workers frequently confront challenges, including the confiscation of their passports, withheld wages, and harsh working conditions. Despite these adversities, there remains a significant lack of solidarity among them. They seldom unite for collective actions such as strikes. On the few occasions when they try to highlight their grievances to the Chinese media, local Chinese embassies frequently suppress any reports that could be viewed as potentially embarrassing to Beijing (Hillman and Tippett 2021).

3 The references to videos on the Chinese short-video platform Douyin are based on the author's personal observations during regular browsing of the platform over an extended period. Due to the dynamic nature of the platform, where content is constantly uploaded and removed, providing permanent references can be challenging. Nonetheless, the examples given are indicative of a recurring theme observed across various user-generated content on the platform. Readers are encouraged to explore the platform to get a firsthand understanding.