Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.26 no.1 Potchefstroom 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2023/v26i0a15664

SPECIAL EDITION: LEGAL HISTORY

Legal History as the Perfect Vessel: Teaching with Infographies for the Development of Digital Visual Literacy Skills in Law Students

A Bauling

University of South Africa. Email: baulia@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Digital literacy development must be regarded equally essential as the development of other literacies and critical thinking skills in Bachelor of Laws students. Because law teachers do not include visuals in learning materials, law students do not develop the skills to effectively interpret them. Digital visual literacy (DVL) is one of the core digital literacies law teachers can advance in their students to prepare them for our visually-driven world. Legal historical course material is the perfect vessel for visual learning materials in law, as these can effectively communicate the spacio-temporal aspects of legal history and legal historical development. A recent empirical study of the views of South African students of legal history indicated their positive sentiments toward a wide variety of visual learning materials and the inclusion of instructor-generated summary infographics in online learning materials. They were also in favour of the inclusion of descriptive visuals like timeline infographics containing additional visual elements in legal historical course content. The study also indicated that reading and interpreting infographics aid the development of DVL skills, and the more infographics students interact with, the better they become at interpreting them. Since the instructor-generated summary infographic can be designed to communicate information about a specific module, it is suited to teaching any legal content. Visual learning artefacts can be created and sourced in numerous ways, but the process can be time-consuming. Sharing these amongst colleagues and institutions as open educational resources (OER) will ultimately aid a collective project aimed at the development of the DVL skills of South African law students. The article provides examples of instructor-generated summary infographics based on legal historical course content, distributed as freely available OER.

Keywords: Digital visual literacy; online legal education; legal history; visual learning in law; infographics; open educational resources.

1 Introduction

Just like everything else, written law - despite a long tradition of black-and-white stodginess - is going multimedia... Students spend years on textual interpretation; images are relegated to the margins, if that. With few exceptions, the law school curriculum remains in thrall to the logocentric traditions of a century ago.1

With this article I aim to illustrate the cardinal importance of the facilitation of visual literacy development in Bachelor of Laws (LLB) students in South Africa. I provide a contextual background to the article and set out why the development of law students' digital literacies is paramount. I explain why the development of digital visual literacy (DVL) skills is important if law students are to meet the demands of an ever-evolving legal practice, and why focussing on the development of these skills supports a pedagogically sound legal teaching practice. I define and discuss DVL, set out why students learn better when visual artefacts are incorporated in learning materials, and discuss the infographic as an example of such an artefact. I illustrate how the learning material for legal historical content provides fertile ground for the incorporation of infographics, which are useful to develop DVL skills. I discuss the findings of my recent empirical study on students completing a module on the Historical Foundations of South African Law, and briefly set out their views on the use of visual learning materials and infographics in legal historical learning materials. I conclude with a discussion on how to create and source pedagogically sound visual learning elements, and the necessity of sharing these as open educational resources to support an effort to develop DVL across all South African law schools and faculties.

2 Background

Between 2012 and 2018 the Council on Higher Education (CHE) formulated procedures for, conducted, and reported on a national review of the LLB degree in South Africa. For these purposes the Qualification Standard for the LLB Degree was formulated to facilitate the evaluation of each university's LLB degree.2 According to this Standard, the competencies to be fostered in the LLB qualification included, inter alia, proficiencies in communication and literacy, information technology, and problem solving.3Based on the findings, the final CHE Report noted a worrying tendency across the LLB programmes: no structured approaches to the use of information and communication technologies, the implementation of technology-enhanced learning strategies, and the development of technology-related literacies.4

Two years after the publication of the CHE Report, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted on higher education (HE) globally and the resultant emergency remote teaching and learning5 demanded of South African law schools sadly proved how prophetic the CHE's warnings were. The need to implement emergency remote teaching and learning almost overnight clearly illustrated how woefully underprepared law teachers at residential universities were to adapt to the challenge at hand. However, academic staff were not to blame. Most residential universities had not paid sufficient attention to the professional development and training of their educators on the effective and pedagogically sound use of their respective learning management systems. Law teachers at existing distance and online learning institutions, such as the University of South Africa (Unisa), had their own challenges. While online teaching and learning infrastructures existed and academics were well-versed in using these in a structured pedagogical approach suitable to open distance and e-learning (ODeL), Unisa's servers crashed many times during online examinations because of the sheer number of students active online at a given time.6

More disturbingly, emergency remote teaching and learning, and the accompanying requirement that students participate in or submit assessments online, illustrated that our students lacked the digital literacies necessary to effectively participate in their own learning.7 The significant impact of the digital divide, most notable in developing countries such as South Africa, further hampered students' chances to develop these literacies.8 Despite the inadequate skills of most law teachers and law students to teach and learn online, South African law teachers have not sufficiently focussed their scholarly contributions on digital skills and literacies development for law students and tuition-related professional development for law teachers.

In the past three years publications in South African law journals focussing on legal education have mainly addressed clinical legal education,9language-related literacies and writing skills,10 subject-specific education,11and postgraduate training and education.12 Notable exceptions exist.13 A recently published book, edited by Maimela, provides insights into how law teachers approached emergency remote teaching and learning during the pandemic, opinions on the future (contribution) of blended learning, and the opportunities created for revised philosophical and pedagogical approaches to education presented via emergency remote teaching and learning.14 But as a scholarly community we have not explored the skills required by our students to navigate online learning, changing legal practice, or an evermore digitally driven world.

One approach South African law schools may adopt to brace their efforts in digital literacy skills development is to focus on digital visual literacy (DVL). DVL is one example of the litany of digital literacies LLB graduates will need once they enter legal practice, and law faculties and schools are shirking their duties if they ignore the necessity of developing these skills. DVL skills development can be incorporated effectively in both fully online and blended education modalities to serve all South African law students.15

3 Digital visual literacy, legal education and legal history

By their very nature law and legal practice are predominantly textual and inevitably a rigid and traditional legal educational method has endured.16Resultantly, visual learning materials are rare, if employed at all, and a focus on visual learning and literacy development in law is absent.17 But a shift is taking place at law schools across the globe. The need to develop law students'18 DVL skills has come under the spotlight and law teachers are advocating that legal teaching practice consciously move away from the dogmatic text-heavy approach.19

Social media is partly responsible for the "visual turn" predominant in today's world.20 Consequently, learning materials free from visual artefacts are "divorced from the world in which the learner lives."21 Academics' bias is to blame. Their generally held perception that visual learning materials are lesser than text encourages students' perceptions in this regard.22 In this way images are regarded both by law teachers and law students as sources of inferior information and relegated to spaces of informal learning.

Next I discuss DVL, how a changing global legal practice is making this an indispensable skill, and the manner in which legal historical course materials are suited to digital visual learning strategies.

3.1 What is digital visual literacy?

Portewig defines DVL as the ability to think, analyse, and convey information visually.23 Spalter and Van Dam further explain DVL as the capability to generate, understand and critically evaluate two-dimensional, three-dimensional, still and moving computer-generated visual materials.24Visual literacy is a vital digital literacy that can be advanced by means of the pedagogically sound inclusion of visual resources in learning materials.25 It is safe to say that

the time has come to add digital visual literacy to the traditional textual and mathematical literacies as a basic skill required for educated citizens and productive participants in the knowledge economy of the 21st century.26

However, merely including visuals in learning materials does not automatically support DVL skills development in students - more is needed from academics.27 Many law teachers who teach face-to-face or via a blended modality utilise text-laden PowerPoint slides or other learning materials that hinder the brain from effectively interpreting the information.28While including images in slides supports the processing of information,29images should not be used exclusively for aesthetic purposes as this wastes the opportunity to develop visual skills. Additionally, digital visual content should also take on various forms such as video (multimedia), photographs, and other graphics.30

The infographic is an example of a digital visual artefact that may effectively be used to develop law students' DVL skills.31 The instructor-provided summary infographic is appropriate to the online learning milieu as this is a "dynamic space for instructional design innovation."32 DVL skills development can also be supported by creating assessments or activities that demand of students to create their own visuals aimed at communicating specific information.33 It is thus evident that today's university graduate who is ready for the digital and visual world of work must regard visuals as crucial sources of potential information and have the ability to interpret and create34these visuals.

But recent developments in legal practice, both in South Africa and across the globe, illustrate why future legal practitioners need to be adept at visual communication and interpretation.

3.2 South African legal practice Is changing

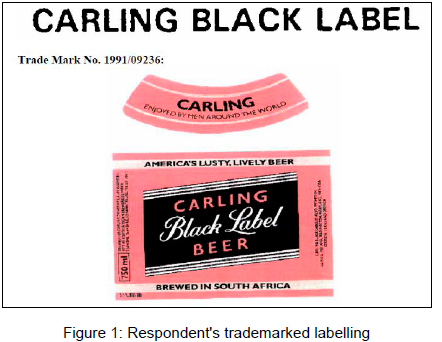

Legal practice is changing to embrace the visual, both globally and in South Africa. An example thereof is evident from the fact that judicial officials are incorporating images into their judgments.35 While this practice is not new, it is starting to become more prevalent. In the 2005 case of Laugh It Off Promotions CC v South African Breweries International36 the Constitutional Court had to consider intellectual property rights in the context of the protections afforded by the fundamental right to freedom of expression. As part of the discussion of the facts, the judgment contained the following images. Figure 1 below depicts the respondent's trademarked labelling as included in the reported judgment:37

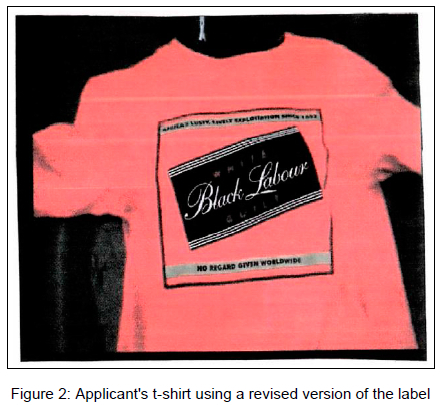

Figure 2 below (as included in the judgment) illustrates the applicant's t-shirt that depicted a revised version of the label in Figure 1, which includes the words "Black Labour", "WHITE GUILT", and "AFRICA'S LUSTY, LIVELY EXPLOITATION SINCE 1652": 38

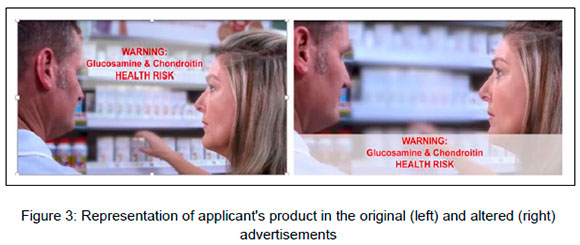

More recently our courts have been asked to consider the visuals incorporated in multimedia applications. In the case of Nativa (Pty) Ltd v Austell Laboratories (Pty) Ltd39 the Supreme Court of Appeal had to consider whether the respondent had falsely disparaged the applicant's product (OSTEOEZE), thereby creating an unfair market advantage.40 The Court considered various aspects communicated in two versions of a television advertisement used by the respondent. One of the questions before the Court was whether the visuals of the advertisements included imagery identifying the applicant's product and warnings that falsely communicated dangers posed by ingredients allegedly included in the applicant's product.41 The judgment contained the following images indicating the initial and altered advertisements in a side-by-side, frame-by-frame comparison:42

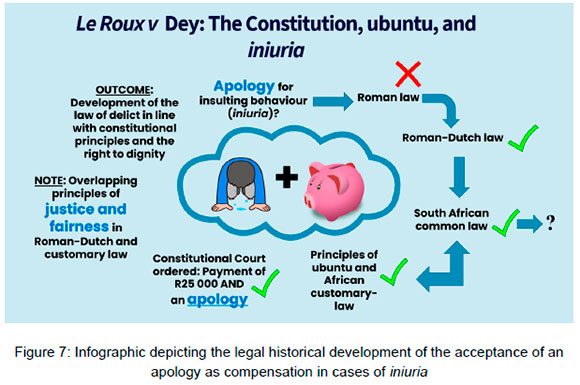

The law of delict has also produced cases that considered the interpretation of graphics and whether the use and distribution thereof constituted defamatory conduct. In the case of Le Roux v Dey43 the applicants (two schoolboys at the time of the incident) created and distributed an electronically generated image purporting to represent the deputy-principal (respondent) and principal of the applicants' school in a scenario depicting homosexual conduct. While the judgment itself did not contain the image created by the applicants, it provides a discussion of an interpretation of the composition of the image. Justice Yacoob, who is blind,44 provided an exposition of what the reasonable person who considered the image would think about it and the creators' intention therewith. He stated that:

The image does not say that Dr Dey or the principal have the habit of engaging in sexual activity with each other or that either of them were of low morals. This is because the pictures are not of the two men but they are pictures with different heads and bodies. ... I say to myself that the children at the school would know when [the applicants] crafted the image that no other person at the school would even begin to believe.45

Another interesting case in which the visual collided with the law of delict was heard in New South Wales, Australia. A preliminary hearing was held in the case of Burrows v Houda,46 concerning a matter in which emojis and emoticons were published on Twitter alongside a link to a newspaper article, and whether this constituted defamation.47 The newspaper article reported on a judge's comments about the plaintiff's unbecoming conduct in court, and whether disciplinary action should be taken against her. Singh provides a discussion of the case and the visuals of the emojis and emoticons in question.48 This case supports the arguments that social media are one of the main drivers of the "visual turn" prevalent in society and the need for the development of South African HE students' visual literacy skills.49

But the use of images in judgments, the role images may play in cases clients bring to their legal representatives, and "the enormous communicative and rhetorical power of visual media"50 and their potential for persuasion in court proceedings are not the only reasons why law graduates need to be digitally visually literate. Law graduates also need DVL and data literacy skills to be able to practise in a world severely impacted on by artificial intelligence (AI).51 The data mined and produced by AI are often represented visually to aid their interpretation due to the sheer scale thereof.52 "Lawtech", which refers to the marriage between technology and legal services,53 is a growing industry, which has significant social and professional implications. Law graduates with a specialised skillset in computer coding will be in an excellent position to develop the apps and algorithms necessary to support and promote the field of lawtech.54 DVL skills will aid the development of these apps, to increase their user-experience levels and user-friendliness.

Clearly legal education should produce fit-for-purpose graduates who can engage with the law in the societal context in which it applies. DVL, one of the core digital literacies, should thus be developed to accommodate the needs of the workplace.55 I will now explain how the visual representation of legal historical course content can support the development of DVL.

3.3 The case for legal history as a conduit for DVL development

The debate regarding what should be taught in legal history courses and how this should be done is a long-standing one. Prof Willemien du Plessis contributed to the discussion of the development of legal historical education by expounding the need to acknowledge and incorporate indigenous African legal histories in our understanding of South African legal development and how it is taught. In her inaugural address of 1991, at the then Potchefstroomse Universiteit van Christelike Hoër Onderwys,56 she argued for an enlightened approach to legal historical education to allow for the emergence of a law graduate who was ready to face the various challenges a (then politically) changing society would demand of its legal practitioners. Like the scholars who came after her, she discussed the legal history course's capability to teach law students a variety of skills and literacies, such as critical thinking skills, and to develop a more questioning stance towards law and the legal practitioner's role in society.57

This discussion on legal historical education and its place in our postapartheid jurisprudence was continued by various scholars and legal history teachers. By addressing the issue from a variety of angles, Nicholson,58 Van der Walt59 and Mitchell,60 amongst others,61 all reach the same conclusion as Du Plessis. They have argued for the retention of legal history as a standalone module or the incorporation of legal historical content in other introductory courses because of its pedagogic value and crucial role in a transformed and decolonialised curriculum. In essence they argue that a legal history course (or module content) can place modern South African law in its historical context and highlight the relationship between political and socio-economic influences, an evolving boni mores, and legal development. I support this argument wholeheartedly and the purpose of this contribution is not to engage with this topic further, since the case has been made eloquently and convincingly.

While many legal history teachers in South Africa seem in agreement that a more transformed and decolonialised approach to legal historical education is required, various approaches exist as to how to teach such content. An interesting approach to both legal historical research and education is found in the notion of how space and time affect law and legal history.62 Meccarelli and Solla Sastre have called for a spaciotemporal understanding of legal history and argue that

the manner in which legal spaces and times - and space and time in law -have been conceived has been inseparably linked to the historical contexts in which those times and spaces were imagined. ... Similarly, historians' understanding of time and space in their context has conditioned, limited or opened up new possibilities for the comprehension of law, and may even be found in the groundings of the definition of law itself.63

Considering legal history from this perspective has implications for the way it should be taught. While we tend to take the temporal aspect of legal history for granted, the spacial aspect thereof is often ignored.64 An example of how space and time impact on both law and history can be explored by investigating the impact of colonisation. Understanding colonisation and its influence on law demands a spaciotemporal interpretation of territoriality and "the symbolic and material appropriation of space."65 One example of how this approach to legal historical education might take shape in South Africa could evaluate the response and resistance to colonisation and apartheid and how these unfolded in a particular space and time.

The South African liberation movement riled against this appropriation of space by a non-native white minority, as well as the oppressive legal rules its government imposed. A transformed and decolonised legal history curriculum should acknowledge the role of the liberation movement in South African legal development. A discussion on the historical development of South African constitutionalism and fundamental human rights could include a conversation on the role of the Freedom Charter of South Africa in legal development. Here, visual learning material may be useful, as graphics are well-suited to communicating context.66

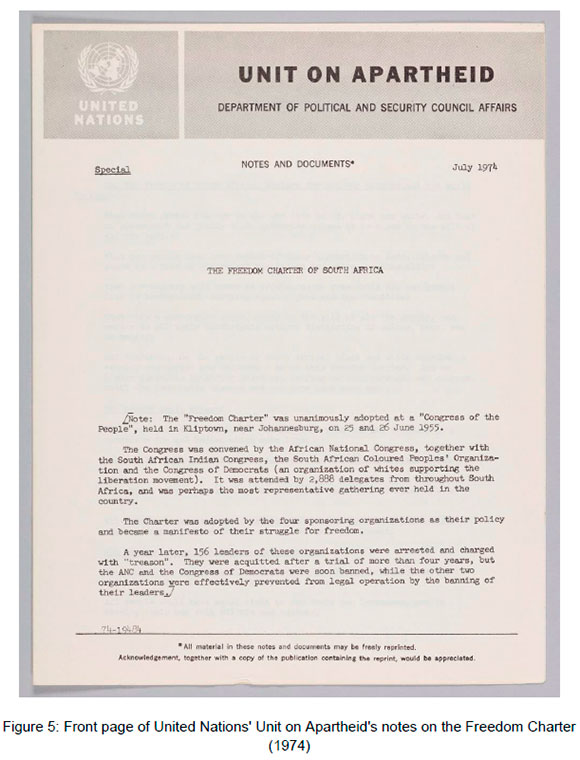

The spaciotemporal context of the adoption of the Freedom Charter can be communicated to legal history students with a visual learning artefact that represents an item in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Figure 5 depicts the first page of a five-page booklet on the Freedom Charter67 published by the United Nations (UN) Unit on Apartheid in 1974.68

The page captured in this image describes the historical context (or space and time) of the adoption of the Charter, as well as information on additional historical events that followed. While the image provides clear and readable information in the form of words, further visual interpretation of the image itself points to the time in which it was created. The grey letterhead, yellowing paper, and type-written wording all point to a pre-digital era, now long gone. The shadow of the page on the table indicates that it is a real document, photographed, digitised, and catalogued in a museum collection due to its historical significance. Additional spatial context is also provided by the image. The document illustrates a global response to apartheid. A discussion of the image with students could also include reference to the sanctions against the apartheid government and South Africa's international isolation at the time.

This single visual example and thoughts on how it could be incorporated in course content have illustrated how learning material addressing South African legal historical development could be used effectively to stimulate critical thinking and develop DVL skills. Both of these skillsets are essential in our digital world.69 Legal practice demands of our graduates to be digitally visually literate, and the development of legal historical course content provides the law teacher with the opportunity to imbue (online) learning materials with images that can help develop DVL skills in law students. While a variety of visual learning artefacts may be used to teach legal history, the infographic is an example of such an artefact that has been empirically proven to aid DVL development.70 The discussion that follows provides further insights.

4 Teaching legal history with infographies

Infographics may be regarded as the quintessential incarnation of visual communication in the digital age.71 Their pervasiveness in our visually driven world is compelling educators to consider including infographics in online learning materials, to enrich the educational experience presented by online and blended learning.72 Legal education should not be left out in the cold by failing to make use of this valuable visual learning resource. The infographic as visual learning artefact employed in online or blended learning is well-suited to presenting legal historical course content and stimulating students' visual acumen and literacy.73

Put simply, an infographic (a portmanteau of "information" and "graphic") is a visual representation of information.74 These graphics are simple to comprehend, stand-alone visual representations used to transmit an entire message, often as a story or sans supplementary text.75 While no consensus exists among scholars regarding which precise elements must be present for a graphic to constitute an infographic, strict definitions require "procedural elements" that influence viewers' thinking and conduct.76 In contrast, many contend that there is no minimum requirement or prerequisite for the complexity of an infographic for it to qualify as such.77 It is, however, accepted that infographics must encompass graphic components that demonstrate a relationship between the concepts communicated to provide the viewer with context.78 Infographics should comprise various visual elements, for example arrows, charts, icons representing data or information, maps, pictures, illustrations or images.79The purpose of including these visual components should be to contextualise, to aid the flow and communication of information, and to enable its interpretation to support learning.80

Infographics are the perfect visual learning artefacts for digital learning. Gallagher at al argue that

[t]he online environment often warrants additional and innovative visual materials to support asynchronous learning, of which summary infographics could be a useful addition.81

The infographic may thus be considered a pedagogically sound visual learning artefact that can effectively support online and blended learning. Infographics are also excellent tools for the development of a variety of digital literacies and other skills.82

The inclusion of infographics in learning materials results in a greater understanding of content and provides students with resources to expand their cognitive abilities.83 The pedagogical use of infographics has been found to "[increase] the collaboration, engagement and conceptual understanding of learners."84 Infographic-supported learning has also proven to have a considerable effect on academic performance and supports the development of metacognitive skills.85 In this way the inclusion of infographics in learning materials supports the attainment of module outcomes, since various facets of learning are bolstered. Crucially, the more students are exposed to infographics and asked to interpret them, the better they will be at understanding them in future.86 This means that the inclusion of infographics in online learning materials for law students supports their DVL skills development.

Apart from supporting DVL skills development, infographics are also highly adept at supporting visual learning, the principles of which are well-suited to teaching legal history. Visual learning materials support students by assisting with the recall of information and the cognitive processing thereof, and by providing ever-important context to what is being learnt.87Incorporating visual representations of information in students' learning materials piques their interest and intensifies their engagement with the content.88 Complex legal learning material containing concepts and terminology foreign to students is easier to understand when clarified by a blend of text and visuals.89 Because "human beings are 'dual processors' of information" images, if used effectively, have vital pedagogical value.90

Infographics are highly effective visual devices with which to teach the subject matter of a specific module or field and are therefore valuable visual resources in HE.91 The infographic as instructional instrument can be used in one of two ways: as the instructor-generated (or -provided), or the student-generated infographic.92 Infographics may therefore embody either learning material, when presented by an academic, or an assessment or learning activity, when created by the student. Porter93 argues that learning deepens when students both interpret and generate graphics, so using them in either approach improves learning.

Instructor-provided summary infographics are graphic artefacts shared (and/or created) by the academic to summarise and present information encountered by the student in the course material.94 Empirical evidence indicates that students regard instructor-provided infographics as valuable learning materials that clarify complex concepts and assist with the recall thereof.95 When engaging in critical thinking exercises and the application of existing knowledge to new problems, students who studied from visual summaries provided by the teacher performed better that those students who created their own.96

To guarantee the pedagogically sound application of infographics in course materials, academics should create or source infographics relevant the course content of the module in question. This ensures that the conceptual understanding that infographics can provide aids students' learning.97

South African legal history may be effectively taught online and in alignment with that expected of a transformed and engaging legal history course98 by using infographics specifically created to teach principles of legal history. I provide examples of what infographics of this nature could look like.

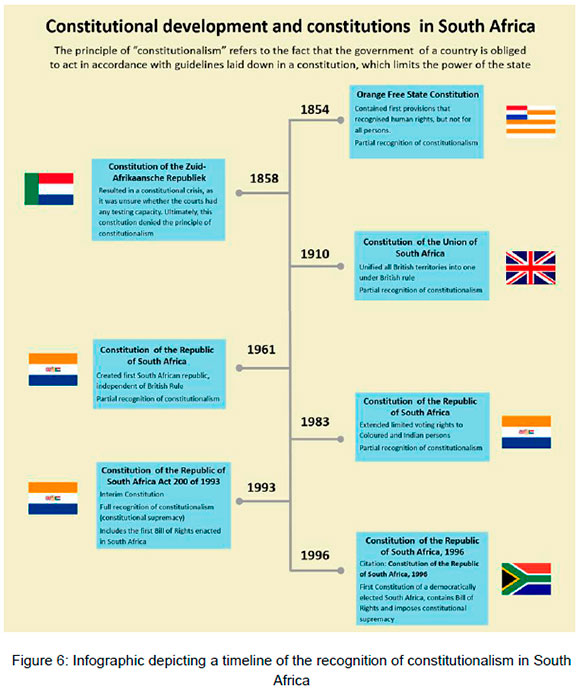

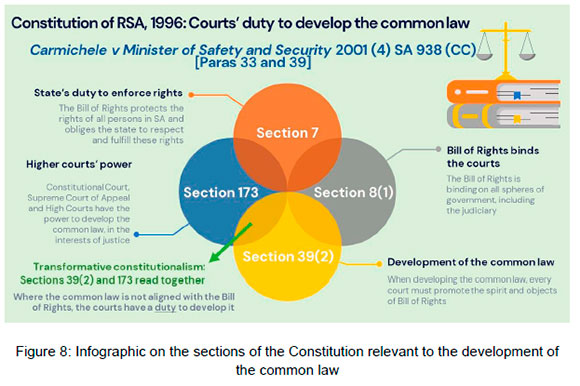

Figures 6 to 8 contain instructor-generated summary infographics included in the online learning materials of the module Historical Foundations of South African Law (HFL1501) at Unisa. Figure 6 represents a timeline infographic, depicting the recognition or not of constitutionalism throughout South African history. The timeline includes flags to represent the governments in power at the time each constitution was adopted.99 The infographic contained in Figure 7 was designed to accompany a discussion of the law on iniuria and its development in the case of Le Roux v Dey.100The infographic encompasses information on the historical recognition or not of an apology as restitution in cases of iniuria, both under South African common-law and African customary-law principles.101 While summarising the course content in question, these infographics also place the content in a spacio-temporal context to aid students' understanding thereof further. Figure 8 depicts a Venn diagram,102 a popular component in infographics, that illustrates the interrelationship between sections 7, 8(1), 39(2), and 173 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996,103 and their role in the development of the common law, as set out in Carmichele v Minister of Safety and Security104 This infographic was designed to illustrate the basis of the constitutional mandate to develop the common law when the need arises.105

The use of these infographics focussing on South African legal historical content and legal development as well as the use of other visual learning artefacts in the online learning materials of the HFL1501 module were empirically investigated to gain insight into students' perceptions of their value. Next, I provide a discussion of this study and its findings.

5 Empirical findings on the use of infographies in online learning materials for legal history

I recently conducted an empirical study on the 2021 cohort of Historical Foundations of South African Law students at Unisa. The main research question of the study considered students' views of the pedagogical value of infographics in the online learning materials of the LLB degree at Unisa.106 The objectives of the study relevant to the subject matter of this contribution in honour of Prof Du Plessis were: to determine which visual learning materials included in the study material were regarded as useful; whether students would appreciate more visual materials in the LLB curriculum; whether students' demographic characteristics impacted their desire to learn from more visual leaning content; whether students' demographic characteristics influenced the required visual literacy skills applicable to infographics analysis; whether prior contact with educational infographics improved their DVL skills essential to reading infographics; and whether students considered the addition of infographics to their study material as significantly impacting their understanding of complex concepts and definitions.107

From the population of 11 444 students (all those registered for the module in 2021) a total of 196 students provided their complete responses to the online questionnaire.108 This sample size (n=196) was non-representative, because it was not large enough to represent the population of the study (N=11 444)109 This means that "generalising from the sample to the intended population becomes risky"110 and that inferences made based on the data may be unreliable.111 Despite the low response rate the sample was considered large enough to obtain useful data, since the purpose of the study was to explore a topic (the use of infographics in learning materials for law) that had not been investigated before.112 The following discussion provides a brief summary of the theoretical and methodological aspects of the study.

5.1 A brief exposition of the empirical study

The theoretical framework of connectivism, as originally conceived and expounded by Siemens,113 was adopted to aid the focus of this study. Connectivism is considered as both a theory of learning and a pedagogical approach focussed on the concept of learning as a networked exercise.114According to the connectivist understanding of learning, the fundamental premise of learning involves the self (the learner) making connections with sources of knowledge. When existing knowledge becomes outdated or insufficient, the ability to develop new connections in the networked learning space becomes essential to future learning.115 In this regard the students' ability to read and understand visual sources of information and their regard for visual sources of knowledges as valid becomes relevant.116

I will now describe the methodological strategies adopted to explain how the study was conducted. The study relied on a non-experimental quantitative research design facilitated by means of a questionnaire. The most fitting research paradigm was that of positivism, which proposes the study of the observable reality of society and the interpretation of unbiassed data.117This cross-sectional descriptive study was implemented with a survey instrument that took the form of a single online self-administered questionnaire distributed to the entire population (N=11 444).

The questionnaire was designed and administered online by means of the Qualtrics XM™ software package. Probability sampling was used to arrive at the sample (n=196), representing all the respondents who submitted their answers to the questionnaire. Descriptive and inferential statistical data analysis techniques were used to interpret the numerical data collected to ultimately reach conclusions based on the responses. Statistical analysis of the data was facilitated with the Qualtrics XM™ and IBM® SPSS® Statistics software packages.118

5.2 Findings

While the study produced a significant amount of data from which various findings were drawn, only those relevant to this contribution are discussed here.119 I now briefly set out what the data analysis indicated regarding the respondents' views on the visuals and infographics used in the online study material of the HFL1501 module in 2021.

5.2.1 Students ' biographical profiles

The questionnaire items that collected biographical data on the respondents considered their age, English-language proficiency, and highest qualification. Almost half (49 per cent) of the sample of students who participated in the study were between the ages of 25 and 40, qualifying as Millennials.120 Students aged 18 to 24 (Generation Z) made up 38.8 per cent of the sample. Most of the respondents (77.6 per cent) were English second-language speakers and listed Matric as their highest qualification (48.2 per cent).121

5.2.2 Students ' preferred visual learning materials

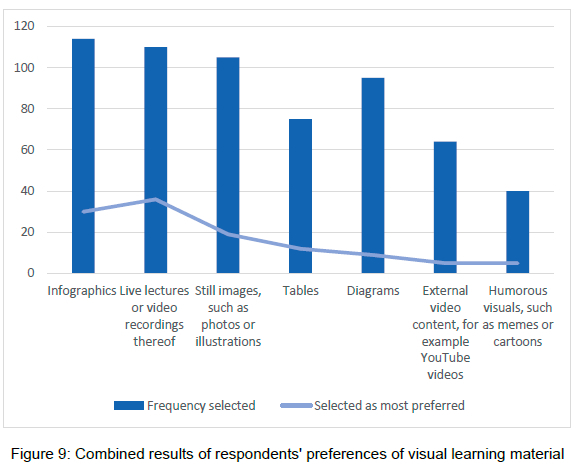

The students were asked to select the visual learning materials they found to be of value from a list of those used in the module. The data are represented by the bars in Figure 9. Infographics, live online lectures or video recordings thereof, and still images (in that order) were selected most frequently as the visuals students found to be of value. A follow-up question requested that students arrange the visuals they had previously indicated to be of value in their preferred order. These data are represented by the line chart in Figure 9. Interestingly, the majority of the respondents favoured the online lectures or their recordings above the infographics as the most valuable visual learning resources, despite the fact that infographics were selected as useful most frequently. An answer to these seemingly paradoxical findings may be found in the literature. Students prefer different types of visual materials to accomplish different learning needs; Yarbrough122 explains that students' divergent backgrounds and learning needs influence their preferences and that it is thus prudent to provide visual course content in various formats.

5.2.3 Students' desire for more infographics and visual learning materials

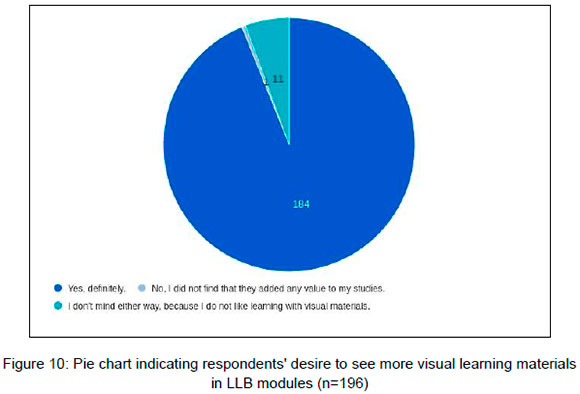

Figure 10 indicates the positive response from students when asked whether they would appreciate the inclusion of more visual materials in their online learning materials across the LLB curriculum. An unequivocal 93.9 per cent of respondents (n=184) illustrated a desire for more visual learning materials, while 5.6 per cent of respondents (n=11) illustrated that they do not like visual learning materials. Only one student (0.005 per cent) indicated finding the visual learning materials to be of no value.123

Inferential statistical analysis was conducted on the respondents' biographical data and their responses to the question on whether they would prefer the inclusion of more visuals in their LLB learning materials.124 The relationships between the data on the students' desire for more visual materials and their ages and English-language proficiency was found to be statistically insignificant.125 This means that the 93.9 per cent of students who wished for the inclusion of more visual artefacts in their learning materials are proportionally representative of all students, regardless of their age or English-language proficiency.

5.2.4 Students' self-reported DVL skills

It was vital that the empirical study investigate whether the students had the ability to understand the infographics used in the module's learning material. The students were asked whether they understood the infographics, and the results were startling. Only the 167 respondents who indicated that they made use of the infographics as learning materials were considered in this calculation. The variables were recoded and ultimately indicated that only 55.1 per cent of respondents thought that they fully understood the infographics used in the module's course materials. The data are expressed in Table 1:

Students' perceived visual literacy was investigated alongside other data to obtain a greater understanding of who the students were who self-reported that they did not understand the infographics. Cross-tabulations of the data on students' self-perceived literacy and their previous exposure to infographics in an educational context as well as their highest qualifications were completed and the statistical significance of the results were determined.126 The relationship between the data on the students' perceived understanding and their prior experience with educational infographics was found to be statistically significant. This means that students who had prior exposure to educational infographics were better able to interpret the infographics used in the HFL1501 study material. But when completing the same analysis alongside the data on the students' levels of qualification, no statistically significant relationship was found. Therefore, students who were better qualified did not report the ability to successfully interpret the infographics more frequently that those students who were less well qualified.127

5.2.5 Students' sentiments towards the infographics

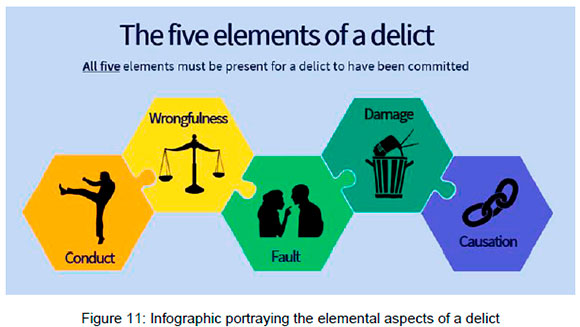

Respondents were asked four questions that gauged their sentiments (as being either positive or negative in nature) towards the infographics included in the HFL1501 course material. Two questions focussed on whether they perceived the infographics as supporting their comprehension of the learning material. Of these two, one question was posed generally while the other focussed specifically on a simple infographic depicting the five elements of a delict (Figure 11 ).128

The remaining two questions concentrated on whether the respondents regarded the infographics as increasing their enjoyment of the learning material and the module. Again, one was posed generally and the other in relation to a specific infographic, namely the infographic of the historical development of South African constitutionalism (Figure 6).

Table 2 contains the analysed numerical data obtained from asking these questions. Responses demonstrating sentiments of a positive nature (which contained words and phrases like "yes", "definitely", "absolutely", "I agree") and those of a negative nature (indicated by responses such as "no"; "not helpful", "I don't think so"; "not really") are reported. Responses that revealed no identifiable sentiment are also indicated:

The data indicate that 77 per cent of students positively associated with statements that the infographics aided their understanding of the course material, while 77.8 per cent indicated that they found the infographics to increase their enjoyment of the module and its course content.

5.2.6 Responses to an open-ended question on timelines

While the study was quantitative in nature, some of the questions were open-ended, allowing for the collection of rich data that could provide a deeper understanding of the students' views. The responses to these open-ended questions were not analysed thematically as required by the qualitative research design, due to the scope and nature of the study. However, considering the textual data collected provided context to the quantitative data as analysed. The following open-ended question focussing on the infographic provided in Figure 6 was included in the questionnaire:

Consider this infographic on the historical development of constitutionalism in South Africa. Do you think you would find the module's learning materials more enjoyable if it contained more timelines or similar descriptive images? Please provide reasons for your answers.

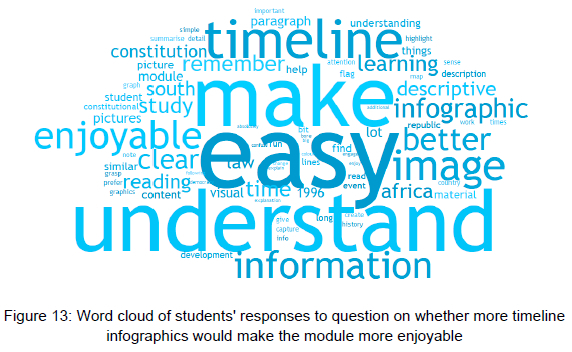

The data gathered from the answers to this question can be evaluated in two ways. The word cloud has become a popular tool with which to represent textual information in a visually perceptible manner.129 Word clouds comprise combinations and groupings of words displayed in a rectangular space in which "[t]he more prominent ... the word is in the word cloud, the more frequently it appeared in the text" being represented.130 The Qualtrics XM™ software package was used to create the word cloud in Figure 13, which is based on the written responses of all 196 respondents.

While using the word cloud as an analysis instrument is not the most scientific approach to data analysis,131 it does allow for the identification of trends in textual data.132

The word cloud illustrates that the relevant words most frequently used by the students in their responses to this question are "easy", "understand", "enjoyable", "clear", "remember", and "better". These words may indicate that the students found this infographic useful in and supportive of their studies.

Further context became evident by analysing a selection of verbatim responses provided by the respondents to this question. I include these specific individual responses here, because of the rich data they provide and their relevance to this discussion:

Respondent 55: "Yes, the use of art work such as flags and flow diagrams to illustrate constitutional development in South Africa captures my attention and makes learning more enjoyable."

Respondent 73: "Yes please, hope you do not mind me using this one for [Introduction to Law] as well".

Respondent 82: "Yes, if more timelines of such nature were included it would have been more enjoyable because I visualize the whole book as a Law timeline that starts from the medieval development of Law down to how it is linked and interwoven with todays Law."

Respondent 128: "Absolutely, ... visuals such as this help to capture one's imagination and help with summarisation and with remembering."

Respondent 165: "Yes - time lines, graphics makes studying simpler and enjoyable. Plain words, reading looks exhausting and can influence one to be lazy to even start".

Respondent 181 : "Yes. It is much easier to read and follow than a string of sentences or bullet points. The pops of colour and layout are appealing and draw your attention to the details. It makes you want to engage more with the content."

Not all the responses were positive, but even those with a more negative tone or criticism provided useful information or additional insights:

Respondent 78: "No, the manner in which it was set out in the study guide worked for me".

Respondent 118: "The writing is a bit small, but it is colourful and I think the timelines is explained better visually than just in a paragraph format."

Respondent 144: "No, still prefer the video clips or classes with study guide and form my own metal pictures".

These responses, as well as the information provided by the word cloud, indicate that many students regarded the timeline infographic as valuable. The textual data show that the infographic allowed some students to understand the contents of the module's learning material more holistically, and in relation to what is being taught in other modules in the curriculum. Other responses illustrate that the timeline infographic stimulated interest in the course content, and that the visual elements of the timeline specifically contributed in this regard.

5.3 Implications

The empirical study on the 2021 HFL1501 students' perceptions of the infographics and visual learning materials used in the course provided insights into how these students think about visual learning, as well as their ability to interpret and learn from infographics. The students indicated that they considered the infographics as beneficial online visual learning materials, but that they also wanted a variety of visuals, such as video recordings of lectures and other still images, included in the learning materials. The students resoundingly supported the addition of more visual materials in their online learning materials in law, and in this regard neither their ages nor English-language proficiency influenced this view.

Almost half of the students who participated in the study did not consider themselves as adequately visually literate to learn from the infographics with success. Students' highest level of qualification had no significant impact on their self-reported visual literacy, but their familiarity with other infographics did. What can be deduced from the data analysis is that prior exposure to educational infographics developed the respondents' DVL skills sufficiently to allow them to effectively interpret and understand the infographics used in the visual materials of HFL1501. The implication is that the more infographics students see, the better they become at understanding them and the more their DVL skills improve.

The students' sentiments towards the infographics used in the learning materials were positive and showed that the infographics both facilitated their comprehension of complex course materials and increased their enjoyment of the module. Evaluating students' responses to the open-ended question on their views on the value of the timeline infographic (Figure 6) indicated that the students regarded this infographic as aiding their contextual understanding of the specific course content and that the visual aspects thereof sparked their interest in the material and the module.

While the sample size of this study (n=196) was not representative of the population (N= 11 444), lessons learnt from this study and the use of online visual learning materials in the HFL1501 module could still inform legal educational practices and the teaching of legal history in South Africa. The educational value added by including visual learning materials (and specifically instructor-generated summary infographics) in the online course content of legal history students may be easily transferred to both the blended tuition modality and other modules in the LLB curriculum. Law teachers now need to rise to the occasion and consider how they can include visuals, such as infographics, in their own learning materials in a pedagogically sound manner.

6 Creating visuals and the need for OER repositories

I have demonstrated the necessity of including visual artefacts in the learning materials of law students and how this would help develop their DVL skills and produce LLB graduates ready for practice. It is imperative that law teachers know how to go about this practically, and knowing how to create and source visuals that are of pedagogical value is crucial. I discuss some strategies on how to accomplish this, and why it is important to share visual resources.

6.1 Sourcing and creating visual learning artefacts

One way to include visuals in learning materials is to use pre-existing free-for-use images available online. Pixabay.com133 is an example of a website with a vast database of images that may be used for free when accompanied by the appropriate attribution to the creator thereof. Licensed images, which may be purchased for a fee, often nominal, are available on websites such as Shutterstock.com.134 There are countless databases of images available for purchase and each university will have its own procedures in this regard. Academic institutions may also have their own database of graphics and photographs available to academics for the inclusion in learning materials.

Recently the academic database JSTOR135 released Artstor,136 a consolidated database of images and art. While these images are free to use, access to the database is restricted. Since JSTOR lists a vast number of academic journals, most university libraries will grant academics and students access to the database. Open access databases of learning materials such as open educational resources (OER) may also be used to source visuals. OER are openly licensed learning materials that have been distributed on the internet by the copyright-holder or creator under a Creative Commons (CC) licence.137 The OER Commons,138 Educause,139and UNESCO140 all have vast databases of OER, but searching for images here is more complicated as most of the OER constitute textbooks and reading materials.

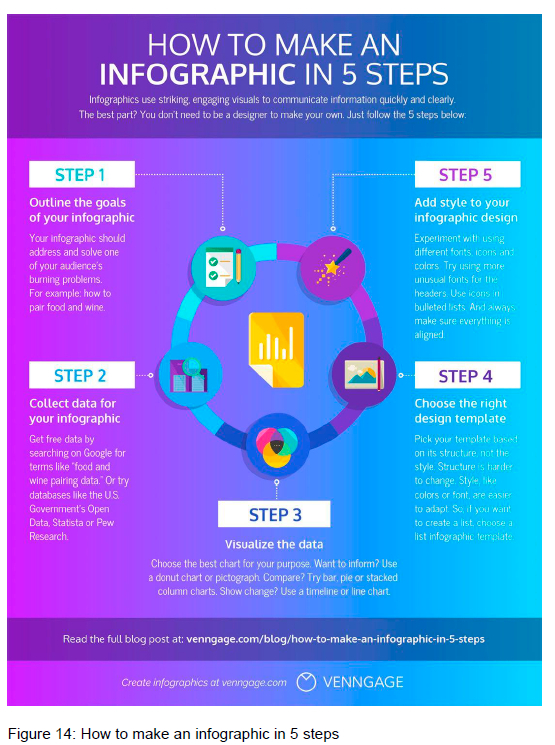

As I have indicated in this contribution, instructor-generated infographics are a valuable visual resource, since academics can tailor these to their specific course content. Infographics can be created with greater ease by making use of existing templates. Many template banks are available online free of charge.141 Infograpia.com142 is one example of a paid bank of infographic templates. While the initial expense is substantial, the service includes lifetime free updates. Infographics may also be sourced by asking students to create these for the purpose of assessment.143 It is important, however, to note that students need to have a sufficient level of existing DVL skills and access to digital tools and software to create these. Law teachers who wish to create infographics for their students may use the following guide on how to initiate such a project. Figure 14 depicts an infographic on how to create an infographic:144

6.2 The need for cooperation and the creation of repositories

South Africa's unique colonial past has shaped its legal system and its sources of law fundamentally, resulting in a legal system situated in the mixed legal family.145 But even in this family of legal oddities, the South African system is different from all others, because of its reliance on Roman-Dutch law, English common law, a modern and democratic constitution, and African customary law sources. The necessity for creating uniquely South African visual learning materials with which to educate our law students is thus obvious.

The creation of field-specific visual content on South African law is a mammoth task. This endeavour would greatly benefit from cooperation between colleagues from various law faculties and schools. The same holds true for the process of creating multi-lingual glossaries for law that encompass terminology in all indigenous languages. The duplication of work is nonsensical and would only slow down production. I propose that law schools and faculties work together, under the guidance of the Society of Law Teachers of Southern Africa, to create repositories of visual learning materials and other free-to-use resources that are aptly licensed as OER. To initialise this project I have published the infographics created for my legal historical course content and shared in this article as freely available OER, with CC BY-SA 4.0 licences.146

CC licences grant others the permission to retain, reuse, revise, remix or redistribute these learning resources while the original source or creator should be acknowledged.147 CC licensing emanated from the need to provide an alternative to restrictive intellectual property laws, to facilitate the distribution of materials freely to others.148 Some of the many benefits of creating new or adopting and revising existing OER is that the practice encourages pedagogical innovation and saves students money in instances where OER are used to replace expensive textbooks.149

Navigating CC licensing rules and guidelines is complex, as it is often difficult to determine which licence150 would best suit a particular OER.151Educational specialists and institutional instructional design divisions could provide law teachers with guidance on how to license materials so that this is done correctly and in adherence to the university in question's standards.

When considering the use and development of OER, law teachers may find valuable guidelines in the emerging field of OER-enabled pedagogy.152 This approach to teaching with OER involves students in the creation, repurposing and evaluation of OER as learning materials, which provides insight into the materials students find beneficial, while developing their critical thinking skills through deeper engagement with the course content.153

7 Conclusion

It is of paramount importance to focus on the development of the DVL skills of LLB students to ensure that we produce graduates who can thrive in modern legal practice, which will become only more visually driven as time passes. Legal historical course material is the perfect vessel (but not exclusively so) for visual learning materials in law. Visual learning artefacts are suited to communicating the space and time in which historical events occurred, granting students insight into how these events affected legal development. These visuals also provide context to the course content being taught, thereby stimulating critical thinking when what is new is being understood in relation to what is already known.

Since the instructor-generated summary infographic can be designed to communicate information about a specific module, it is suited to teaching any legal content. The infographics included in this contribution154 illustrate how legal historical course content is taught visually in the Historical Foundations of South African Law module presented online at Unisa. An empirical study into the use of these infographics and other visual learning materials illustrated that law students want more visual learning content, that these visuals must be in a wide variety of formats, and that they support learning while increasing students' enjoyment of course content. The study also indicated that reading and interpreting infographics support the development of DVL skills, and the more infographics students interact with, the better they become at understanding them. Of importance is the fact that legal history students indicated positive sentiments towards learning from materials that include descriptive visuals like timeline infographics containing graphic elements.

Visual learning artefacts can be created and sourced in numerous ways, but ultimately they must be shared amongst colleagues and institutions to aid the development of the DVL skills of South African law students across institutions. A concerted effort will be required to achieve this.

Bibliography

Literature

Aggarwal R and Ranganathan P "Study Designs: Part 2 - Descriptive Studies" 2019 Pers Clin R 34-36 [ Links ]

Alford K 2019 "The Rise of Infographics: Why Teachers and Teacher Educators Should Take Heed" 2019 Teaching/Writing 158-175 [ Links ]

Alrwele NS "Effects of Infographics on Student Achievement and Students' Perceptions of the Impacts of Infographics" 2017 JEHD 104-117 [ Links ]

Alyahya D "Infographics as a Learning Tool in Higher Education: The Design Process and Perception of an Instructional Designer" 2019 IJLTER 1-15 DOI: 10.26803/ijlter.18.1.1 [ Links ]

Arendse L "Online Teaching, Covid-19 and the LLB Curriculum: Looking Back to Look Forward?" in Maimela C (ed) Technological innovation (4IR) in Law Teaching and Learning: Enhancement or Drawback During Covid-19? (PULP Pretoria 2022) 59-67 [ Links ]

Asimow M and Sassoubre TM "Introduction to the Symposium on Visual Images and Popular Culture in Legal Education" 2018 JLE 2-7 [ Links ]

Bauling A Students' Views of the Pedagogical Value of Infographics in the Online Learning Materials of the Bachelor of Laws Degree at the University of South Africa (MEd-dissertation University of South Africa 2023) [ Links ]

Bicen H and Beheshti M "The Psychological Impact of Infographics in Education" 2017 BRAIN 99-108 [ Links ]

Barhate B and Dirani KM "Career Aspirations of Generation Z: A Systematic Literature Review" 2022 EJTD 139-157 [ Links ]

Boeren E "The Methodological Underdog: A Review of Quantitative Research in the Key Adult Education Journals" 2018 AEQ 63-79 [ Links ]

Bozkurt A and Sharma RC "Emergency Remote Teaching in a Time of Global Crisis Due to Coronavirus Pandemic" 2020 AJDE i-vi [ Links ]

Brown A et al "A Conceptual Framework to Enhance Student Online Learning and Engagement in Higher Education" 2022 HE R&D 284-299 [ Links ]

Castan M and Hyams R "Blended Learning in the Law Classroom: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Intervention in the First Year Curriculum Design" 2017 L Ed Rev 1 -20 [ Links ]

Council on Higher Education Qualification Standard for Bachelor of Laws (LLB) (CHE Pretoria 2015) [ Links ]

Council on Higher Education Report on the National Review of LLB Programmes in South Africa (CHE Pretoria 2018) [ Links ]

Church J, Schulze C and Strydom H Human Rights from a Comparative and International Law Perspective (Unisa Press Pretoria 2007) [ Links ]

Colbran SE and Gilding A "An Authentic Constructionist Approach to Students' Visualisation of the Law" 2019 The Law Teacher 1-34 DOI: 10.1080/03069400.2018.1496313 [ Links ]

Costa P "A 'Spatial Turn' for Legal History? A Tentative Assessment" in Meccarelli M and Solla Sastre MJ (eds) Spatial and Temporal Dimensions for Legal History (Frankfurt Max Planck Institute for European Legal History 2016) 27-62 [ Links ]

Crocker AD "Using Peer Tutors to Improve the Legal Writing Skills of First-Year Law Students at University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College School of Law" 2020 JJS 128-153 [ Links ]

Crocker AD "Motivating Large Groups of Law Students to Think Critically and Write Like Lawyers: Part 1" 2020 Obiter 751-766 [ Links ]

Crocker AD "Motivating Large Groups of Law Students to Think Critically and Write Like Lawyers: Part 2" 2021 Obiter 1 -19 [ Links ]

Denvir C "Scaling the Gap: Legal Education and Data Literacy" in Denvir C (ed) Modernising Legal Education (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2020) 73-91 [ Links ]

Dunlap JC and Lowenthal PR "Getting Graphic About Infographics: Design Lessons Learned from Popular Infographics" 2016 J Vis Lit 42-59 [ Links ]

Du Plessis MA and Welgemoed M "Training for Legal Practice - Towards Effective Teaching Methodologies for Procedural Law Modules" 2022 Obiter 205-233 [ Links ]

Du Plessis P and Du Plessis W "Engaging with African Customary Law: Legal History in Contemporary South Africa" 2017 PELJ 1-5 DOI: 10.17159/1727-3781 /2017/v20i0a3266 [ Links ]

Du Plessis W "Afrika en Rome: Regsgeskiedenis by die Kruispad" 1992 De Jure 289-307 [ Links ]

Dziwa DD "Hyper Visual Culture: Implications for Open Distance Learning at Teacher Education Level" 2018 Progressio 1-15 DOI: 10.25159/02568853/4705. [ Links ]

Fagan E "Roman-Dutch Law in its South African Historical Context" in Zimmermann R and Visser D (ed) Southern Cross: Civil Law and Common Law in South Africa (Juta Kenwyn 1996) 34-64 [ Links ]

Gallagher ES et al "Instructor-Provided Summary Infographics to Support Online Learning" 2017 Ed Media Intl 129-147 [ Links ]

Galloway K "Rationale and Framework for Digital Literacies in Legal Education" 2017 L Ed Rev 1 -26 [ Links ]

Gumb L "An Open Impediment - Navigating Copyright and OER Publishing in the Academic Library" 2019 C&RL News 203-206 [ Links ]

Hayes S "Counting on the Use of Technology to Enhance Learning" in Jandric P and Boras D (eds) Critical Learning in Digital Networks (Springer London 2015) 15-36 [ Links ]

Hearst MA et al "An Evaluation of Semantically Grouped Word Cloud Designs" 2020 IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2748-2761 [ Links ]

Holness D "Improving Access to Justice through Law Graduate Post Study Community Service in South Africa" 2020 PELJ 1-25 DOI: 10.17159/1727-3781/2020/v23i0a5968 [ Links ]

Horn JG and Van Niekerk L "The Patchwork Text as Assessment Tool for Postgraduate Law Teaching in South Africa" 2020 Obiter 292-308 [ Links ]

Hutchinson A "Recontextualising the Teaching of Commercial Transactions Law for an African University" 2021 Acta Juridica 275-296 [ Links ]

Imberman S and Fiddler A "Share and Share Alike: Using Creative Commons Licenses to Create OER" 2019 ACM Inroads 16-21 [ Links ]

Iyer D "Online Learning: Shaping the Future of Law Schools" 2022 Obiter 142-151 [ Links ]

Jordaan C and Jordaan D "The Case for Formal Visual Literacy Teaching in Higher Education" 2013 SAJHE 76-92 [ Links ]

Kanuka H "Understanding e-Learning Technologies-in-Practice through Philosophies-in-Practice" in Anderson T (ed) 2nd ed The Theory and Practice of Online Learning (AU Press Edmonton, AB 2008) 91-118 [ Links ]

Köseoglu S, Veletsianos G and Rowell C (eds) Critical Digital Pedagogy in Higher Education (AU Press Athabasca, AB 2023) [ Links ]

Kozlina S "'That's Me in the Photo': Photography as a Critical Pedagogy Technique in Legal Education" 2021 L Ed Rev 41-57 [ Links ]

Lankow J, Ritchie J and Crooks R 2012 Infographics: The Power of Visual Storytelling (Wiley Hoboken, NY 2012) [ Links ]

Maimela C (ed) Technological Innovation (4IR) in Law Teaching and Learning: Enhancement or Drawback During Covid-19? (PULP Pretoria 2022) [ Links ]

Maithufi M and Maimela CA "Teaching the 'Other Law' in a South African University: Some Problems Encountered and Possible Solutions" 2020 Obiter 1 -9 [ Links ]

Matusiak KK et al "Visual Literacy in Practice: Use of Images in Students' Academic Work" 2019 C&RL 123-139 [ Links ]

Meccarelli M and Solla Sastre MJ (eds) Spatial and Temporal Dimensions for Legal History (Max Planck Institute for European Legal History Frankfurt 2016) [ Links ]

Meccarelli M and Solla Sastre MJ "Spatial and Temporal Dimensions for Legal History: An Introduction" in Meccarelli M and Solla Sastre MJ (eds) Spatial and Temporal Dimensions for Legal History (Max Planck Institute for European Legal History Frankfurt 2016) 3-24 [ Links ]

Mitchell L "Developing Critical Citizenship in LLB Students: The Role of a Decolonised Legal History Course" 2020 Fundamina 337-363 [ Links ]

Mnyongani F "'The Use of Technology Has Always Been Part of the Plan for Higher Learning Institutions' - Experts on Teaching During Covid-19 at UP Law Lecture" in Maimela C (ed) Technological Innovation (4IR) in Law Teaching and Learning: Enhancement or Drawback During Covid-19? (PULP Pretoria 2022) 1-17 [ Links ]

Moolman HJ and Du Plessis A "Key Considerations for Traditional Residential Universities Intending to Offer Bachelor of Laws (LLB) through the Distance Mode of Tuition: A Case Study" 2021 PELJ 1-36 DOI: 10.17159/1727-3781/2021/v24i0a8953 [ Links ]

Mubangizi JC and McQuoid-Mason DJ "Teaching Human Rights in Commonwealth University Law Schools: Approaches and Challenges, with Passing References to Some South African Experiences" 2020 Obiter 106121 [ Links ]

Murray MD "The Sharpest Tool in the Toolbox: Visual Legal Rhetoric" 2018 JLE 64-73 [ Links ]

Mutula SM "Peculiarities of the Digital Divide in Sub-Saharan Africa" 2004 Program 122-138 [ Links ]

Nicholson CMA "Back to the Future: Teaching Legal History and Roman Law to a Demographically Diverse and Educationally Underprepared Student Body" 2005 Fundamina 50-62 [ Links ]

Nicholson C "The Relevance of the Past in Preparing for the Future" 2011 Fundamina 101-114 [ Links ]

Porter EG "Imagining Law: Visual Thinking Across the Law School Curriculum" 2018 JLE 8-14 [ Links ]

Portewig CP "Making Sense of the Visual in Technical Communication: A Visual Literacy Approach to Pedagogy" 2004 JTWC 31-42 [ Links ]

Palmer VV Mixed Jurisdictions Worldwide 2nd ed (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2012) [ Links ]

Ramlo S "Using Word Clouds to Present Q Methodology Data and Findings" 2011 JHS 99-111 [ Links ]

Roberts D "Higher Education Lectures: From Passive to Active Learning Via Imagery?" 2019 ALHE 63-77 [ Links ]

Ryan T "Coding for Critical Thinking: A Case Study in Embedding Complementary Skills in Legal Education" 2021 L Ed Rev 81 -104 [ Links ]

Sandford-Couch C "Challenging the Primacy of Text: The Role of the Visual in Legal Education" in Bankowski Z and Mae M (eds) Beyond Text in Legal Education (Taylor and Francis London 2013) 145-167 [ Links ]

Sherwin RK "Visual Literacy for the Legal Profession" 2018 JLE 55-63 [ Links ]

Silver K "Hacking the Law: Social Justice Education through Lawtech" in Köseoglu S, Veletsianos G and Rowell C (eds) Critical Digital Pedagogy in Higher Education (AU Press Athabasca, AB 2023) 79-91 [ Links ]

Sindane N "Prophecy and the Pandemic: The Vindication of Decolonial Legal Critical Scholarship" 2022 SAPL 1-13 DOI: 10.25159/25226800/10144 [ Links ]

Singh P "Can an Emoji Be Considered as Defamation? A Legal Analysis of Burrows v Houda [2020] NSWDC 485" 2020 PELJ 1-26 DOI: 10.17159/1727-3781/2021/v24i0a8918 [ Links ]

Sivo SA et al "How Low Should You Go? Low Response Rates and the Validity of Inference in IS Questionnaire Research" 2006 JAIS 351-414 [ Links ]

Snyman-Van Deventer E "Methods to Use When Teaching Legal Ethics in South Africa" 2021 Obiter 312-335 [ Links ]

Spalter AM and Van Dam A "Digital Visual Literacy" 2008 Theory into Practice 93-101 [ Links ]

Strydom H "Sampling in the Quantitative Paradigm" in De Vos AS et al (eds) Research at Grass Roots 4th ed (Van Schaik Pretoria 2011 ) 222-235 [ Links ]

Tillinghast B, Fialkowski MK and Draper J "Exploring Aspects of Open Educational Resources through OER-Enabled Pedagogy" 2020 IAFOR J of Ed 159-174 [ Links ]

Tredoux L "Tax Education: Tax in Law" 2020 TAXtalk 34-36 [ Links ]

Uyan Dur B "Data Visualization and Infographics in Visual Communication Design Education at the Age of Information" 2014 JAH 39-50 [ Links ]

Van Allen J and Katz S "Teaching with OER During Pandemics and Beyond" 2020 JME 209-218 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe S "Towards Designing a Validated Framework for Improved Clinical Legal Education: Empirical Research on Student and Alumni Feedback" 2020 PELJ 1-31 DOI: 10.17159/1727-3781/2020/v23i0a8144 [ Links ]

Van der Walt AJ "Legal History, Legal Culture and Transformation in a Constitutional Democracy" 2006 Fundamina 1-47 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk GJ "Amende Honorable and Ubuntu: An Intersection of Ars Boni Et Aequi in African and Roman-Dutch Jurisprudence?" 2013 Fundamina 397-412 [ Links ]

Welgemoed M "Clinical Legal Education during a Global Pandemic -Suggestions from the Trenches: The Perspective of the Nelson Mandela University" 2020 PELJ 1-31 DOI: 10.17159/1727-3781/2020/v23i0a8740 [ Links ]

Werth E and Williams K "Learning to Be Open: Instructor Growth through Open Pedagogy" 2021 Open Learning 1-14 DOI: 10.1080/02680513.2021.1970520 [ Links ]

Wiley D and Hilton JL "Defining OER-Enabled Pedagogy" 2018 IRRODL 133-147 [ Links ]

Williams K and Werth E "Student Selection of Content Licenses in OER-Enabled Pedagogy: An Exploratory Study" 2021 JCEL 1-20 DOI: 10.17161/jcel.v5i1.13881 [ Links ]

Yarbrough JR "Infographics: In Support of Online Visual Learning" 2019 AELJ 1-15 [ Links ]

Zawacki-Richter O and Jung I (eds) Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education (Springer Nature Singapore 2023) [ Links ]

Case law

Burrows v Houda 2020 NSWDC 485

Carmichele v Minister of Safety and Security 2001 4 SA 938 (CC)

Laugh It Off Promotions CC v South African Breweries International (Finance) BV t/a Sabmark International 2006 1 SA 144 (CC)

Le Roux v Dey 2011 3 SA 274 (CC)

Nativa (Pty) Ltd v Austell Laboratories (Pty) Ltd 2020 5 SA 452 (SCA)

Legislation

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Internet sources

Adobe Express 2023 Editable Infographic Templates https://www.adobe.com/express/templates/infographic accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

Constitutional Court of South Africa date unknown Justice Zak Yacoob https://www.concourt.org.za/index.php/judges/former-judges/11-former-judges/67-justice-zak-yacoob accessed 9 February 2023 [ Links ]

Educause 2023 Open Educational Resources (OER) https://library.educause.edu/topics/teaching-and-learning/open-educational-resources-oer accessed 21 February 2023 [ Links ]

Fengu M 2020 Unisa Students Unhappy with Online Exams https://www.news24.com/citypress/News/unisa-students-unhappy-with-online-exams-20200511 accessed 26 January 2023 [ Links ]

Infograpia 2023 Home https://infograpia.com/ accessed 21 February 2023 [ Links ]

JSTOR 2023 The New Artstor Experience on JSTOR https://www.jstor.org/ accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

JSTOR 2023 Home https://www.jstor.org/ accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

McLane J 2020 Unisa Online Exam Problems - Faulty Hardware and Server Overload https://mybroadband.co.za/news/cloud-hosting/356041-unisa-online-exam-problems-faulty-hardware-and-server-overload.html accessed 26 January 2023 [ Links ]

Merriam Webster 2003 Venn Diagram https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Venn%20diagram accessed 15 May 2023 [ Links ]

Nediger M 2023 How to Make an Infographic in 5 Steps https://venngage.com/blog/how-to-make-an-infographic-in-5-steps/ accessed 18 May 2023 [ Links ]

OER Commons 2020 About CC Licenses https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/ accessed 7 December 2022 [ Links ]

OER Commons 2023 Home https://www.oercommons.org/ accessed 21 February 2023 [ Links ]

Pixabay 2023 Home https://pixabay.com/ accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

Sciuchetti M 2022 Mastering Creative Commons and OER: How to Develop and Share Engaging Resources for the Hybrid Classroom https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/fclectures_2022/9/ accessed 7 December 2022 [ Links ]

Shutterstock 2023 Home https://www.shutterstock.com/ accessed 13 February 2023 [ Links ]

Siemens G 2005 Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age http://itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm accessed 1 February 2023 [ Links ]

United Nations 1974 Notes from the United Nations on the Freedom Charter of South Africa https://www.si.edu/object/notes-united-nations-freedom-charter-south-africa:nmaahc_2015.97.27.30 accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation 2023 Open Educational Resources https://www.unesco.org/en/open-educational-resources accessed 21 February 2023 [ Links ]

Venngage 2023 Home https://venngage.com/templates accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

Visme 2023 Home https://www.visme.co/templates/infographics/ accessed 10 February 2023 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

ACM Association for Computing Machinery

AELJ Academy of Educational Leadership Journal

AEQ Adult Education Quarterly

AI Artificial intelligence

AJDE Asian Journal of Distance Education

ALHE Active Learning in Higher Education

BRAIN Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience

C&RL College and Research Libraries

C&RL News College and Research Libraries News

CC Creative Commons

CC0 Creative Commons Zero

CHE Council on Higher Education

DVL Digital visual literacy

Ed Media Intl Educational Media International

EJTD European Journal of Training and Development

HE Higher Education

HE R&D Higher Education Research & Development

HFL1501 Historical Foundations of South African Law

IAFOR J of Ed International Academic Forum Journal of Education: Technology in Education

IEEE Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

IJLTER International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

IRRODL International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning

JAH Journal of Arts and Humanities

JAIS Journal of the Association for Information Systems

JCEL Journal of Copyright in Education and Librarianship

JEHD Journal of Education and Human Development

JHS Journal of Human Subjectivity

JJS Journal of Juridical Science

JLE Journal of Legal Education

JME Journal of Multicultural Education

JTWC Journal of Technical Writing and Communication

J Vis Lit Journal of Visual Literacy

L Ed Rev Legal Education Review

LLB Bachelor of Laws

OdeL Open distance e-learning

OER Open educational resources

PELJ Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal

Pers Clin R Perspectives in Clinical Research

SAJHE South African Journal of Higher Education

SAPL Southern African Public Law

UN United Nations

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation

Unisa University of South Africa

Date Submitted: 22 February 2023

Date Revised: 20 July 2023

Date Accepted: 20 July 2023

Date Published: 23 November 2023

Guest Editors: Prof M Carnelley, Mr P Bothma

Journal Editor: Prof C Rautenbach

* Andrea Bauling. BA LLB LLM (UP) MEd (UNISA). Lecturer, University of South Africa. Email: baulia@unisa.ac.za ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4458-0241. I should like to thank Dr Carina van der Westhuizen, Dr Kelly Young and Prof Emile Zitzke for their guidance and inputs. This article includes a short report on the research findings of my MEd dissertation of limited scope. In this effort I was greatly supported by my supervisors, Dr Faiza Gani and Prof Geesje van den Bergh. The usual caveats apply.

1 Porter 2018 JLE 8-9.

2 CHE Qualification Standard 4.

3 CHE Qualification Standard 10-11. Also see Arendse "Online Teaching, Covid-19 and the LLB Curriculum" 60. She discusses these competencies, as captured in the CHE's LLB Qualification Framework (2015), and how they relate to the necessity to develop critical thinking skills in LLB students.

4 CHE Report on the National Review 41-43.

5 The terms "online learning" was thrown around loosely by many academics and teachers who wrote about their experiences or suggested "best practices" for teaching remotely during the Covid-19 pandemic. What many of these educators failed to acknowledge is that online learning is an established field and complex pedagogical approach to digital distance education that encompasses designing learning specifically for online delivery (Hayes "Counting on the Use of Technology to Enhance Learning" 15-36; Brown et al 2022 HE R&D 284). Bozkurt and Sharma 2020 AJDE ii explain that while educators thought they were involved in online distance education, they were in essence only participating in emergency remote teaching. Referring to "online learning" in a context devoid of the applicable pedagogical strategies and accepted practices is inaccurate and irresponsible. For some of the most recent thoughts on online learning and related pedagogies, see the contributions in Köseoglu, Veletsianos and Rowell's Critical Digital Pedagogy and Zawacki-Richter and Jung's Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education.

6 Fengu 2020 https://www.news24.com/citypress/News/unisa-students-unhappy-with-online-exams-20200511; McLane 2020 https://mybroadband.co.za/news/cloud-hosting/356041-unisa-online-exam-problems-faulty-hardware-and-server-overload.html.

7 Iyer 2022 Obiter 145.