Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.26 no.1 Potchefstroom 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2023/v26i0a14940

SPECIAL EDITION: ENVIRONMENTAL & ENERGY LAW

Is the Stick Real? Trends from Concluded Prosecutions of Industrial Environmental Crimes in South Africa

M Strydom; T Field

University of Witwatersrand, South Africa. Email: melissastrydom29@gmail.com; tracy-lynn.field@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

South Africa's suite of environmental laws contains many criminal sanctions and penalty provisions. Whether the criminal sanction is an effective tool that realises the constitutionally protected environmental right depends on how it is practically enforced and whether potential offenders become aware of such enforcement measures. This article reports on research aimed at collecting and analysing prosecutions for industrial-related transgressions (conducted mainly in Magistrates' Courts) and involving offences under the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), the Waste Act, the Air Quality Act and the National Water Act. An analysis of 53 prosecutions shows that most cases resulted in convictions, half were concluded through plea and sentence agreements, half involved the conviction of individuals, no direct imprisonment penalties were imposed, and low fines were imposed in most cases. The findings include that there is some inconsistency in how different listed activities or water uses are treated as separate or consolidated criminal charges, and the exact number, outcome, or trends arising from such cases are difficult to determine as there is no central, readily accessible database of concluded prosecutions. Increased access to such information will improve knowledge, implementation and the effective use of the criminal sanction through prosecutions. In turn, this will contribute to the improved realisation of the constitutionally protected environmental right.

Keywords: Environmental law; environmental crime; industrial environmental crime; environmental prosecutions; criminal law; plea and sentence agreements; section 105A agreements; environmental right.

1 Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, South Africa has enacted a comprehensive suite of environmental laws1 to give effect to the constitutional obligation to protect the environment through reasonable legislative and other measures.2These laws3 contain many criminal offences, and on conviction, a person may be liable to significant penalties, including imprisonment, fines, or both.4

Criminal liability may be substantial depending on the nature of the offence. Maximum prescribed penalties up to R5 million or R10 million or imprisonment of up to five or ten years could be imposed.5 Section 34 of the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA) also provides for further possible consequences including that, on conviction, an accused can be ordered to pay damages or pay for losses suffered to rehabilitate or repair damages to the environment, reasonable prosecution costs, or damages equal to the advantage the accused may have gained from the transgressions.6 Liability may also extend to employers, including incorporated entities, being liable for the actions of their employees, and individuals (directors, managers, employees or agents) could be liable even where the offence benefitted an employer.7

South African environmental law academics have considered the criminal enforcement of environmental laws.8 The current literature considers the extent of criminal sanctions,9 the functionaries tasked with enforcement, the weaknesses of criminal prosecutions, the liability of corporations, directors and employers,10 alternatives to criminal measures,11 and the need to 'rethink' aspects of environmental crime in South Africa.12 Other themes considered include sentencing environmental crimes,13 the effectiveness of plea and sentence agreements,14 forms of liability15 and aspects of self-incrimination.16 However, to date the current literature has not analysed trends of criminal prosecutions in the context of industrial facilities with reference to the body of concluded cases.

Punishment through criminal sanctions can only have real deterrent value if it is believed that offenders will be caught, successfully prosecuted, and serve their sentence.17 People or entities conducting activities that may trigger environmental crimes18 may undertake a risk analysis - to determine the risk of being caught and successfully prosecuted. They may consider (or perceive) the risk as low or unlikely, if the sentence that may ultimately be imposed will not result in directors/employees going to jail, or if the fine will not break the bank. After weighing up these considerations, a prospective "criminal", may decide to proceed with their (unlawful) activities, rendering the deterrent theory of punishment ineffective.19

Environmental sanctions' deterrent value depends on "the likelihood of apprehension, prosecution, conviction and significant penalty".20 Kidd states that:

Effective enforcement is important when deterrence is the goal, and the public must be aware of penalties being utilized since "ultimately, one cannot fear what turns out to be a paper threat".21

Thus, the efficacy of prosecutions and the value of convictions require knowledge of what is happening in the criminal law system.

Holmes22 famously asserted that the law consists of "prophecies of what the courts will do ... and nothing more pretentious". Without a central, readily accessible database of concluded prosecutions, it is difficult to determine the number, outcome, or trends arising from such cases, i.e., what courts do. Although criminal measures have been evaluated in South African environmental law,23 no one has undertaken an empirical assessment of concluded prosecutions for industrial environmental crimes in South Africa, i.e., prosecutions that reached the end of the criminal justice process, resulting in a conviction or acquittal.

This research set out to obtain information on concluded environmental prosecutions in the context of industrial operations,24 focussing on offences in the NEMA, the National Environmental Management: Waste Act 59 of 2008 (the Waste Act); the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004 (the Air Quality Act); and the National Water Act 36 of 1998.

This paper aims to analyse the collected data on concluded environmental prosecutions, ascertain trends from such cases and report such findings. Ultimately, 53 concluded prosecutions under the mentioned laws were considered. A limitation of this research is that the outcome of such cases is not readily accessible and only published in limited instances; thus reliance was placed on obtaining the information from other sources, including research participants.

The remainder of this paper comprises Part 2, which sets out the methodology of the research. Part 3 outlines the relevant context in considering concluded prosecutions. Part 4 highlights findings and themes from the cases considered, and a discussion of the main findings appears in Part 5.

2 Methodology to collect and collate case information

The research involved gathering publicly available information on relevant concluded prosecutions, whether completed through a guilty plea, trial, or plea and sentence25 (section 105A) agreement. The focus was on concluded prosecutions for "industrial" (brown sector)26 environmental crimes, focusing on facilities established for producing or manufacturing products or commodities or treatment and disposal of waste, which activities are often undertaken in areas zoned for industrial use.

Industrial facilities are generally required to comply with various environmental laws, and their activities could have significant environmental impacts. To operate lawfully, they may be required to hold numerous environmental authorisations, permits, licences, and/or registrations (collectively referred to as "approvals").27 The inquiry was limited to the NEMA, Waste Act, Air Quality Act and National Water Act, based on their overarching relevance to industrial facilities, and to keep the research within manageable bounds. Several other laws may apply to industrial facilities,28 but these four are the principal laws considered.

There is no existing case law database containing the complete outcomes (with the underlying judgments, sentences or section 105A agreements) on concluded prosecutions for industrial environmental crime. We therefore had to turn to various sources to gather information on concluded cases, whether reported in the media, published by public benefit or other organisations or published in databases of court judgments.

The annual National Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Reports (NECERs) published by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE)29 from 200830 to 202031 were considered as a starting point for requesting case outcomes from relevant role-players. The number of industrial prosecutions instituted or adjudicated under the four selected laws is unknown as the NECERs provide overall statistics, not per sector. Information on concluded cases was received from participants in the underlying research32 and is limited to what was obtained.33 There are likely more cases, including prosecutions predating or postdating the NECERs. The cases collected thus represent a starting point for the development of a more comprehensive database.

The period for the inquiry was limited to 2005 to 2020, as the first concluded prosecution under the selected laws appeared to be from October 2005.34 Although there are prior prosecutions,35 their outcomes are not easily accessible. The 2005 start date also somewhat corresponds with the timing of the insertion of the approval-related offence provision in NEMA in 2005.36 The last concluded cases were from 2020, being the cutoff date for the research project.37

The prosecutions included in the data-set were mainly conducted in lower courts,38 i.e., Magistrates' Courts,39 as these courts also have jurisdiction over environmental crimes; NEMA grants magistrates' courts enhanced penal jurisdiction, but does not take away the high courts' jurisdiction to also hear such matters.40 It is not general practice in the Magistrates' Courts and not explicitly required by the rules of court for written judgments to be handed down by the presiding officer/magistrate for reporting purposes.41 The mechanical recording can be transcribed to obtain a written record of the proceedings and details of the judgment. A limited number of outcomes in prosecutions relevant to this research are accessible online. For example, section 105A agreements, judgments, or transcripts have been published by the Centre for Environmental Rights for eleven cases concluded in Magistrates' Courts.42 The outcomes of prosecutions in Magistrates' Courts are not reported in a central academic or public database (e.g., in case law reports) and are not accessible on research platforms.

Concluded case information is public unless otherwise directed by a Court,43 but it was impossible to visit each Magistrates' Court in South Africa to source cases due to time and resource constraints. High Court judgments relating to environmental matters are generally accessible, particularly when the judgment is marked reportable,44 but prosecutions rarely take place in these courts. Generally, the High Court becomes involved where a stay of prosecution in the lower court is sought,45 or where the outcome of a prosecution or warrant, or the seizure of items or confiscation orders are challenged.46 The only known environmental prosecution in the High Court, relevant to this research,47 was the private prosecution in Uzani Environmental Advocacy v BPSA.48

In order to obtain case information for concluded prosecutions, other sources had to be consulted, including requests to relevant role-players, and some reliance has to be placed on the information received. Initially, when public information was considered and before more information was received from role-players, there appeared to be limited industrial-related prosecutions. The scope of the inquiry was thus extended to a wider range of cases under the four selected Acts, including prosecutions for mining or farming-related activities. This broader inquiry resulted in the collection of 53 cases,49 of which 40 relate to industrial-type contraventions.

The thirteen additional cases comprised of the following:

Although these additional cases fall beyond the remit of industrial environmental crimes, it was decided to include them in the dataset, as their inclusion advanced the objective of establishing a baseline archive of environmental criminal prosecutions. They also served as a separate subset to compare the findings emerging from an analysis of the industrial cases. For example, nearly half of the additional cases were also concluded through a section 105A agreement.

As stated, this collection of 53 cases is very likely incomplete because it relies on information from limited sources and is not a consolidated, official database. Other cases may be unknown to the authors, and more recent cases (involving municipalities) have since emerged of which the data is not readily available except for what is reported in the media.63 The available information obtained is often also limited; for example, although the NECERs contain case summaries or mention matters criminally investigated and prosecuted, they do not necessarily provide a comprehensive account of all concluded industrial-type prosecutions.

Notwithstanding the value of knowing how many cases have been successfully prosecuted, unfortunately, for 23 of the 53 cases, the information received was limited.64 For many of these cases, only sentence annexures were received, i.e., after a guilty verdict the Magistrate will hand down a sentence usually comprising of a 1 to 2-page document. This sentence annexure cites the accused and the sentence but contains no (or very limited) further case information. From the sentence annexure, it may also be unclear which charges the accused faced.

The analysis and findings in this paper are limited by the challenges outlined above, particularly due to incomplete or difficult-to-access information. Nevertheless, the collection of cases in this research is the most complete current compendium of industrial environmental crime prosecutions assembled in South African environmental law scholarship to date.65

The bulk of this article highlights themes from the case analysis, with a view to determining the efficacy of the criminal sanction and its use as a reasonable legislative measure to protect the environment.66 As a necessary pre-cursor to that analysis, Part 3 sets out the constitutional and legislative context for environmental crimes in South Africa.

3 Industrial environmental criminal sanctions as a legislative measure to realise the constitutionally protected environmental right

This part situates the environmental criminal sanction within the context of the reasonable legislative measures intended to advance section 24 of the Constitution; relevant role players and pathways to prosecution; and sentencing; and the effectiveness of criminal sanctions.

3.1 Role of the criminal sanction within a suite of legislative measures to realise section 24

Non-compliance with environmental law requirements can be met with enforcement action ranging from civil and administrative to criminal action (as "command-and-control" mechanisms).67 The criminal sanction is a tool the State can use to realise the constitutionally protected environmental right, as it provides for punitive consequences when there is noncompliance with legislative measures. Traditionally, the aim of criminal law is said to include:

(i) prevention; (ii) deterrence, which may be on an individual or general basis; (iii) reformation or rehabilitation and (iv) retribution.68

Many consider the criminal mechanism a last resort69 that should be reserved for serious offences70 "when other means of dealing with offending and non-compliance fail".71 This reservation of the criminal law mechanism as a last resort can be construed as a last resort legislative measure, i.e. the last resort legislatures turn to in regulating behaviour. However, it could also be construed in a regulatory sense, as the last resort where legislation provides other mechanisms to address non-compliance. There is no requirement in South African environmental law to exhaust other mechanisms before proceeding to criminal prosecution; thus, administrative compliance and enforcement mechanisms and the criminal sanction can be used concurrently. Based on experience in practice, and the interviews conducted as part of the underlying research, the concurrent use of these mechanisms could be due to the seriousness of the contravention and to prompt corrective or remedial action.

Kidd aptly notes various challenges in achieving the aims of a criminal sanction, considering the widespread difficulties faced by a criminal justice system in crisis,72 and its weaknesses, particularly in an environmental law context.73 Yet, criminal sanctions for environmental law transgressions are so widely prescribed74 that the laws are described as being "littered with new criminal offences".75

For a mechanism to promote the section 24 constitutional right, it must be effective and used appropriately, within the confines of the other constitutionally protected rights. To understand the efficacy of the sanction, one has to consider its practicality and how it has been/can be used, i.e., by considering actual concluded cases and role-player concerns.76

3.2 Role-players and pathways to prosecution

Environmental Management Inspectors (EMIs) are central role-players in investigating environmental crimes and referring cases to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) for prosecution. EMIs can be designated for different mandates and functions or to enforce different environmental laws.77 Their functions could include compliance monitoring or enforcement.78 In the case of the latter, EMIs usually investigate acts or omissions (within their mandate) where there is a reasonable suspicion that it might constitute an environmental law offence.79 They have broad general powers, including questioning people about suspected unlawfulness.80

EMIs must refer a criminal case to the NPA for a decision on whether or not to prosecute. In the context of industrial environmental crimes, if the NPA decides to proceed with a prosecution, the accused will ordinarily be summoned to appear in court.81 Most industrial-related environmental crimes involve corporate entities, ordinarily cited as the first accused, as represented by corporate officers.82

Criminal prosecutions can be concluded in different ways, if a matter proceeds to trial, it could culminate in a guilty plea,83 or a section 105A agreement.84 If the accused pleads not guilty the matter will proceed to a hearing. When pleading guilty, an accused may explain their guilty plea through a plea explanation. The court may question the accused to ensure guilt and the absence of a valid defence.85 If an accused pleads not guilty, the presiding officer may ask if the accused wants to explain their defence.86 If it is unclear what is in dispute, the presiding officer may question the accused to establish which charges are contested.87 The matter then ordinarily proceeds to trial unless the prosecutor and a represented accused enter into a section 105A agreement (which is subject to formal requirements and judicial approval as explained below).

It is also possible for a prosecution to commence and not be concluded through any of these three avenues - a prosecutor could decide not to prosecute, or the matter could be provisionally withdrawn.88 This paper does not consider these cases as it is more challenging to establish the status of pending or provisionally withdrawn prosecutions. These cases are considered sub judice. Further, information is even less readily available because there is no definite outcome regarding the guilt or innocence of an accused.

As discussed below, nearly half of the cases considered were concluded through section 105A agreements, a section inserted into the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 (CPA) in 2001, formalising the "informal and longstanding practice of plea-bargaining".89 The section 105A provisions can be used in any criminal case and are not limited to environmental prosecutions.90 Certain formal requirements must be met before a court may accept a section 105A agreement, including that it must be in writing and at least state that the accused was informed of their rights to be presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, to remain silent, not to testify during the proceedings, and not to be compelled to give self-incriminating evidence.91 The agreement must contain substantial facts, facts relevant to the agreed sentence, and any admissions made by the accused.92 The court may not participate in the negotiations,93 and its role is limited to confirming that the accused entered into the agreement and that the prosecutor consulted the investigating officer and complainant.94

If satisfied that the accused admits the allegations in the charge and guilt, the court may ask relevant questions and hear evidence for sentencing purposes. If the court is satisfied that the sentence agreement is just and fair, the court sentences the accused accordingly.95 If not, the court informs the parties of the sentence it considers just. The agreement may be withdrawn by the parties, or they may abide by it subject to the right to lead evidence and present arguments relevant to sentencing.96 If the parties abide by the agreement and present evidence and argument relevant to sentencing, the court can convict the accused and impose the sentence it considers just.97 However, if they withdraw from the agreement, the trial will start anew before another presiding officer unless the accused waives this right.98 No record of the negotiations or agreement may be used unless the accused consents to recording any of their admissions.99

3.3 Sentencing and level of penalties

High penalties, either R5 million- or five-years imprisonment, or R10 million or ten years imprisonment, are generally (currently) prescribed in NEMA,100 the Waste Act101 and Air Quality Act.102 This contrasts with the five years' imprisonment provided for in the National Water Act penalty, which does not specify an equivalent monetary penalty and converts to R200 000.103

Although high penalties are prescribed in statute, these are not necessarily the penalties imposed by courts or negotiated as part of a section 105A agreement. In considering what an appropriate sentence might be, courts have a wide discretion and consider "the triad" of the crime, the offender's personal circumstances, and the interests of society, as well as the proportionality of the sentence in relation to the crime, the offender's personal circumstances and the interests of society.104

The research considered how many of the 53 cases resulted in comparatively high or low sentences (considered further below). Echoing Holmes' assertion,105 if courts do not impose such high penalties, it may indicate that the maximum prescribed statutory penalties (although an upper limit) are too simplistic or may give rise to disproportionality or disparity.

3.4 Effectiveness of the criminal sanction in SA environmental law

As previously stated, the deterrent value of environmental sanctions depends on "the likelihood of apprehension, prosecution, conviction and significant penalty".106 Deterrence relies on effective enforcement and requires public knowledge of penalties being imposed.107 According to Husak, whether criminal statutes produce any marginal gains in deterrence is doubtful,108 and lengthy delays in the criminal justice system erode deterrence value.109

The critiques of deterrence theory110 bring into question the value of environmental sanctions and prosecutions, particularly considering challenges in using criminal sanctions as an enforcement tool, the delays and difficulties within the criminal justice system,111 and the lack of readily available information about concluded prosecutions.112 The effectiveness of criminal sanctions for environmental law transgressions is linked to the general efficacy of the criminal justice system, which has been described as being in crisis.113 Any challenges and delays in that system undermine the aims of criminal law. In other words, prevention becomes less likely with lengthy time lapses whilst disputes are being adjudicated in court. The impact of punishment and deterrence then also deteriorates.

4 Assessing the cases

With the above context in mind, the 53 concluded cases collected were analysed to identify emerging themes including (1) the pathways to criminal prosecution, either through a guilty plea, trial or section 105A agreement; (2) total convictions and whether a natural (individual) or juristic person was prosecuted; (3) the percentages of the sentences imposed compared to the maximum prescribed penalty for the charge(s) the accused faced and whether it was comparatively high or low;114 (4) if additional sanctions were imposed in terms of section 34 of NEMA; (5) how charges relating to separate listed activities or water uses received different treatment in some cases; and (6) how similar penalties are prescribed regardless of the seriousness or actual environmental impact of a transgression.

4.1 Pathways to criminal prosecution

Twenty-six of the 53 cases were concluded through section 105A agreements and thirteen were concluded through guilty pleas or trials. For the remaining thirteen, it is unclear whether the prosecution was concluded by a guilty plea or trial due to limited or incomplete available information.115 Cases concluded through a section 105A agreement generally have the most information because the agreement contains relevant details and is more readily accessible. For some cases, written judgments were available;116 for others, transcriptions or High Court appeal judgments provided some information.117

Table 2 below provides a summary of how the 53 cases were concluded.

Compared to the proportion of general crimes concluded with section 105A agreements, the use of such agreements for environmental crimes appear high. According to the NPA 2019/20 Report, 2166 section 105A agreements were entered into in that year out of 231 725 finalised criminal matters,171 a ratio of just below one per cent. Based on the case information received, the ratio for section 105A agreements in environmental crimes is much higher - at 49 per cent - but this represents cases concluded over many years out of the total multi-year database of 53 cases (which is probably not an exhaustive database).

Several benefits (for the prosecution and accused) associated with the plea-and-sentence pathway may be driving the high ratio of section 105A agreements for environmental crimes. From the prosecution's perspective, environmental crimes are complex in terms of fact and law and require a lot of time, effort, and resources to pursue. Most prosecutors and magistrates (as experts in criminal or civil law and procedure) may have limited exposure to, or experience in, working with environmental laws.172The evidence is often of a scientific and technical nature, comprising of extensive documents and reports. As a result, it may be difficult for the prosecution to achieve a conviction on all charges. A section 105A agreement can result in a quicker case resolution, which would otherwise involve a protracted trial, which also requires extensive State time and resources. The benefits in terms of time and resources saved (within an already constrained criminal justice system) are often listed as mitigating circumstances in section 105A agreements. In other words, it states in mitigation that the accused pleaded guilty to the offences in the section 105A agreement thereby saving State resources and not wasting the court's time. It could (or at least should) also result in the transgressor's quicker attendance to the environmental impacts requiring remediation or authorisation.

The benefits of a section 105A agreement for an accused also involve some level of certainty over the conviction and sentence, as it is negotiated and agreed. In such negotiations, the accused may be able to select charges to which it is willing to plead guilty, thereby achieving a compromise. It is often also a compromise in the negotiation process that the juristic entity pleads guilty and is convicted, and then the charges against any natural persons who also appear as accused (often directors or employees) are withdrawn, preventing individuals from obtaining criminal records. It may be that natural persons are cited as co-accused as a tactic to encourage section 105A negotiations. In other words, where employees, directors or corporate decision-makers are cited as co-accused with the corporate entity, such employees would rather negotiate that the juristic entity pleads guilty, and a compromise is reached in the form of a section 105A agreement to avoid the prosecution of the individuals in their personal capacity. A criminal record likely has more severe consequences for an individual than it would have for a juristic entity. Individuals obtain a criminal record through a SAP69 which record is easily retrievable based on fingerprints and may affect various aspects of an individual's life (employment or travel prospects). Whereas juristic entities with such a record can be wound up, deregistered and reestablished.

When reading the facts and circumstances in the section 105A agreements, culpability/fault is not always apparent. Often the charges relate to negligent as opposed to intentional offences. Section 105A agreements contain lengthy explanations of the accused's reasonable measures to avoid environmental harm or offences. Of course, the accused takes a "best foot forward" approach in explaining the circumstances that led to the alleged contravention. However, this makes it difficult to assess the level of culpability thoroughly. Because not many of the cases considered have ended in a successful trial with available detailed records, it was also challenging to assess the level of culpability or how the court may decide on a matter.173

4.2 Total convictions - natural persons convicted

Of the 53 concluded cases, only one resulted in an acquittal after going to trial.174 This is indicative of a 98 per cent conviction rate. A possible explanation for this could be that due to limited resources, only strong cases are selected for prosecution (or pursued). The authors are aware of some matters where the prosecution did not proceed due to the technical nature of some transgressions, the lapse of time, questionable culpability, the magnitude of relevant evidence and lack of State resources, including sourcing expert witnesses.

In about half (26 of 53) of the successful prosecutions, natural (individual) persons were convicted,175 most involving a business entity where individuals were convicted either alone or with a business entity - as persons in authority, proprietors, or directors. Unfortunately, for most of these cases (17), limited information is available; for many, only a SAP69 form (the form that records the accused's conviction) and a short annexure indicating the sentence was received. Often, the information lacks the complete charges the accused faced. For these 17 cases, it was therefore impossible to assess each individual's culpability or factors relevant to the sentence imposed.

Nevertheless, the available information is useful in adding to the database of known concluded prosecutions. Albeit limited and constrained, the data was used to try and establish how the sentences imposed compare to the prescribed maximum penalties. Fourteen cases involving the conviction and sentencing of a natural person (excluding where a section 105A agreement was concluded or in the case of S v Frylinck) resulted in a comparatively extremely low sentence, equal to or below one per cent of the potential maximum penalty. This figure may indicate that when the court's discretion is exercised in sentencing, the punishment considered appropriate for individuals is at the lower end.

4.3 Percentage comparison of sentences imposed versus potential maximum statutory penalties

In the overwhelming majority of cases, comparatively low sentences were imposed. This finding is based on a comparison of the prescribed penalty for the known charges and sentences that were ultimately imposed.176 In 43 of the cases (81 per cent) sentences below 50 per cent of the potential maximum statutory penalty were imposed. Five cases resulted in comparatively high sentences/fines. For the remaining five cases, the comparative percentage is unknown because of limited data.

The five cases that resulted in comparatively high sentences, and the calculation/comparison, appear in Table 3 below.177 Notably, three of these cases were concluded through section 105A agreements (1, 4 and 5 in the table below). The other two (numbers 2 and 3 below) were concluded through a trial (Frylinck) or a guilty plea (Joubert).178 In respect of items 1, 4 and 5 in Table 3, the accused may have agreed to relatively high fines to keep evidence of its culpability out of the public domain and limit reputational risk; other factors unknown to the researchers may also have influenced these agreed penalties. Because a section 105A agreement was concluded, underlying evidence would not be presented in open court and may limit public attention. Without considering the underlying evidence, the basis for agreeing to high fines is speculative.

Of the total cases, 41 resulted in fines of less than 20 per cent (most less than 5 per cent) compared to the potential maximum statutory penalty. Eleven of these resulted in a zero per cent fine; the reasons for this could include that the accused did not have the financial means to pay a fine, and the court may have considered a conviction and criminal record a sufficient punishment. In other instances, remediation costs might have been paid or payable. One accused was sentenced to serve three years of correctional supervision and undertake community service.184

When considering all the comparatively low sentences imposed (or accepted by courts) it could be argued that the prescribed maximum statutory penalties are at the extreme high end. This is particularly so considering that when sentencing principles are applied such high sanctions were likely considered to be inappropriate (and lower sentences imposed). Although the prescribed sanctions are maximums, the fact that much lower sentences are imposed does bring into question the functionality of only prescribing maximum penalties.

4.4 Listed activity treatment - Splitting of charges, duplication of convictions and multiplicity of sentencing

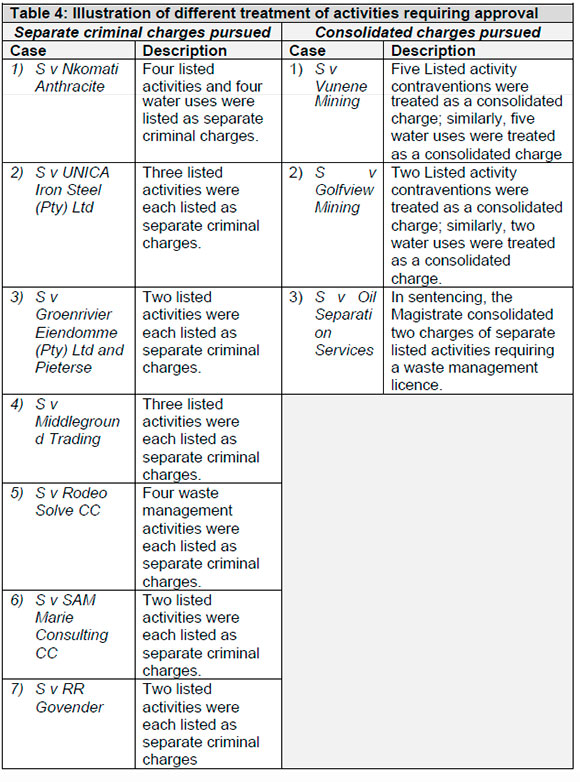

Another aspect that arose from the case assessment is that there appears to be inconsistency in how cases involving approvals for listed activities or water uses are treated. For example, where an accused undertook an activity that triggered several NEMA listed activities or water uses under the National Water Act, sometimes the prosecution dealt with each listed activity or water use as a separate criminal transgression/charge. In other cases, these were consolidated into one charge. An illustration of these cases appears in Table 4 below.

Based on the phrasing in section 24F of NEMA, each contravention of undertaking a listed activity (singular) without an environmental authorisation is a contravention and a criminal offence.185 Similar provisions appear in the Waste Act186 and National Water Act.187 Thus, (in principle) the correct position is the separate listing of each activity or water use as a separate contravention and charge. There is no immediately apparent reason or trend explaining the different approaches. A further aspect that may arise from this different treatment of listed activities or water uses is the possibility of duplication of charges and convictions,188 but is excluded from the ambit of this paper.

4.5 Section 34 of NEMA

Section 34 of NEMA creates further possible consequences when a person is convicted of NEMA Schedule 3 offences, such as damages or cost orders, and additional liability provisions, including possible liability of directors, managers, agents and employees, even where an offence benefits an employer. As mentioned above, natural persons were convicted in 26 of the 53 cases. In at least eight of these, natural persons appear to have been convicted together with juristic entities.189

Section 34 was used in 17 of the 53 cases (32 per cent) to secure payment directly to environmental authorities. This is different to the normal procedure, where a fine paid at the Magistrates' Court goes to the National Treasury. In some instances, section 34(4) was used to recover the reasonable costs incurred by the public prosecutor and the organ of state concerned. In other instances, damages were ordered in terms of section 34.

Table 5 below lists some examples where additional fines were payable directly to environmental authorities or organisations, thereby diverting payment from the general state coffers.

Imposing such additional sentences or penalties may also raise questions regarding just desert and proportionality. However, the above cases were concluded through section 105A agreements where the accused agreed to these additional sentences.

4.6 Similar offences for less serious contraventions

South African environmental law prescribes high maximum penalties with no gradation or distinction between the actual impacts of such offences or their severity. A prosecutor should seek a just, proportionate and appropriate sentence after conviction, and a presiding officer will consider relevant evidence before imposing an appropriate sentence.190 Subjecting serious and less serious offences to similar high penalties could lead to disproportionality. In other words, for the legislature to catch all offences under possible prescribed maximum penalties of R5 million or R10 million, whether serious or not, provides no direction or guidance to those that enforce or impose penalties. Magistrates' courts, that may not regularly deal with cases where their monetary jurisdiction is extended to this extent, may be reluctant to impose high fines (that may be justified in the context of serious environmental offences). Conversely, high penalties may be imposed if all offences are tarred with the same brush. If there is no gradation in the law as to what offences are considered more serious and no gradation or guidance it may result in absolute inconsistency in fines or sentences imposed, specifically as there is no central database where these case outcomes are recorded.

Penalties for serious or less serious crimes could be similar, as illustrated in the following three cases. In S v Die Straat Trust, the accused was charged with (1) conducting an unlawful water use; (2) failing to register a water use; (3) and (4) detrimentally affecting a water resource by excavating soil and constructing a road during February 2015. Counts 1-4 are all subject to a similar maximum penalty of R200 000. Undertaking a water use without a licence or polluting or detrimentally impacting a water resource (charges, 1, 3 and 4) appear prima facie more severe than the failure to register a water use (charge 2).191

In S v E Adams,192 the accused pleaded guilty to 22 charges all related to waste management activities, the failure to comply with licence conditions and compliance notices; and norms and standards requirements (regarding access control, signage, failure to store waste in covered containers, or exceeding capacity requirements). The maximum potential statutory penalties under the Waste Act for fourteen of the charges193 is R10 million, and for the other eight,194 it is R5 million. Similarly, it appears that three of the charges related to contraventions with less or no direct environmental impacts, for example, a failure to comply with norms and standards requiring access control or signage. In comparison, the other offences have the potential to have severe environmental impacts, yet the same maximum penalty could be applied.

In S v Samancor Manganese,195 the accused was charged with seventeen charges regarding the failure to comply with seventeen conditions across three waste management licences and failing to comply with a condition of its atmospheric emissions licence. The contravention of each different licence condition constitutes separate criminal acts, but the impact of each should be considered as some of these could be administrative non-compliances without direct environmental impacts. For example, not informing the authorities of changes in contact details is unlikely to have environmental impacts and a lower penalty would be more appropriate.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This paper set out to establish trends from the concluded environmental prosecutions in South Africa, and found that most of the cases resulted in convictions, half were concluded through section 105A agreements, half involved the conviction of individuals, and no direct imprisonment penalties were imposed. Comparatively low fines (compared to the possible maximum prescribed statutory penalties) were imposed in most cases. In about a third, the mechanisms or consequences contemplated in section 34 of the NEMA were invoked. There is some inconsistency in how different listed activities or water uses are treated as separate or consolidated criminal charges. The exact number, outcome, or trends arising from such cases are difficult to determine as there is no central, readily accessible database of concluded prosecutions.

The foregoing analysis informs the question of whether the criminal sanction is a 'reasonable measure' for purposes of realising section 24 of the Constitution. In revisiting the questions a prospective offender may ask themselves in considering the risk of facing an environmental prosecution (as posed in the introduction), it is clear that such prosecutions occur, more than we may be aware of (considering that 53 cases were gathered as part of this research) and 98 per cent of these cases resulted in convictions. The risk of being caught and successfully prosecuted may not be as low or unlikely as may have been perceived before knowing of these 53 cases. Although the sentences ultimately imposed may not result in direct imprisonment (at least not for first offenders), many individuals have obtained criminal records in these cases (in 26 of the 53 cases). Nevertheless, awareness of these prosecutions is a key to attaining improved protection of the section 24 environmental right.

The trend to conclude environmental prosecutions through section 105A agreements196 appears to have benefits, including a quicker resolution of a case and some certainty over the outcome. A further benefit is that authorities can use it to negotiate funds earmarked for specific purposes, as contemplated in section 34 of NEMA, i.e., to be used for remediation costs, and investigation costs, to support the performance of the functions of EMIs.

For large organisations, the penalties imposed may not break the bank, but for smaller enterprises, it may be more of a punishment - considering that most of the cases (81 per cent) resulted in comparatively low sentences/fines. Only five of the cases considered resulted in comparatively high sentences. As courts consider appropriate sentences and factors relevant thereto, natural persons received comparatively extremely low sentences (in fourteen cases), equal to or below one per cent, indicating that courts' discretion may temper disproportionality as they do not impose fines commensurate with the maximum prescribed penalties. The more common imposition of comparatively low sentences may weaken the retributive and deterrence value of the criminal sanction.

For the section 24 constitutionally protected environmental right to be realised using criminal sanctions, environmental offences must be met with retributive action, punishing offenders proportionally to the harm caused, deterring offenders and others from committing such offences. Proportionality is influenced by the nature of the accused (corporate entity or an individual) and the nature of the transgression (serious or administrative). To be reasonable, criminal sanctions should distinguish between serious and less serious offences depending on the actual environmental impacts. Prescribing the same potential maximum penalty for all offences (or offenders) may lead to disproportional sentences or unequal enforcement.197 There must be consistency in prosecutorial approaches - such as with listed activity treatment and depending on the underlying facts. Of greater importance is that the harm to the environment is repaired and rehabilitated. These are considerations that should guide criminal enforcement and the creation of criminal sanctions to achieve the ultimate aim of realising the constitutionally protected environmental right.

The research has also highlighted the need for a publicly accessible database with detailed case information. The lack of such a database undermines the deterrent objective of criminal law and arguably impairs the efficacy of law enforcement efforts.

Knowledge of practical challenges in the application of the law (through case outcomes) will positively influence legislative drafting, thereby promoting more practical and accurate laws. Key role-players (regulators, enforcement authorities, prosecutors, magistrates, defence counsel, the regulated community, and the general public) may learn from how others have applied the law to facts, and become more familiar with environmental laws, which will develop and enhance its application.

The accessibility of such cases will broaden general awareness (enhancing its deterrent value). Justice would be more visible to the general public and would be "seen to be done".198 Increased awareness of successful prosecutions will increase deterrence and contribute to the improved implementation and the effective use of the criminal sanction through prosecutions.

The benefits of such a database will ultimately extend to a better-protected environment.

Bibliography

Literature

Brickey KF Environmental Crime: Law, Policy, Prosecution (Aspen New York 2008) [ Links ]

Burns Y and Kidd M "Administrative Law and Implementation of Environmental Law" in King ND and Strydom HA (eds) Fuggle and Rabie's Environmental Management in South Africa 2nd ed (Juta Cape Town 2009) 222-268 [ Links ]

Cameron E "The Crisis of the Criminal Justice System" 2020 SALJ 32-71 [ Links ]

Craigie F, Snijman P and Fourie M "Dissecting Environmental Compliance and Enforcement" in Paterson A and Kotzé L (eds) Environmental Compliance and Enforcement in South Africa: Legal Perspectives (Juta Cape Town 2009) 41-61 [ Links ]

Craigie F, Snijman P and Fourie M "Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Institutions" in Paterson A and Kotzé L (eds) Environmental Compliance and Enforcement in South Africa: Legal Perspectives (Juta Cape Town 2009) 65-102 [ Links ]

Duff RA et al The Boundaries of the Criminal Law (Oxford University Press Oxford 2010) [ Links ]

Fourie M "How Civil and Administrative Penalties Can Change the Face of Environmental Compliance in South Africa" 2009 SAJELP 93-118 [ Links ]

Hall J "Facing the Music through Environmental Administrative Penalties: Lessons to be Learned from the Implementation and Impact of Section 24G?" 2022 PELJ 1-34 [ Links ]

Holmes OW Jr "The Path of the Law" 1897 Harv L Rev 457-478 [ Links ]

Husak D "The Criminal Law as Last Resort" 2004 OJLS 207-235 [ Links ]

Husak D Overcriminalization: The Limits of the Criminal Law (Oxford University Press Oxford 2008) [ Links ]

Kidd M "Environmental Crime: Time for a Rethink South Africa?" 1998 SAJELP 181-204 [ Links ]

Kidd M "The Use of Strict Liability in the Prosecution of Environmental Crimes" 2002 SACJ 23-40 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Alternatives to the Criminal Sanction in the Enforcement of Environmental Law" 2002 SAJELP 21-50 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Vicarious Liability for Environmental Offences" 2003 Obiter 186193 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Liability for Corporate Officers for Environmental Offences" 2003 SA Public Law 277-288 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Environmental Audits and Seff-Incrimination" 2004 CILSA 84-95 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Sentencing Environmental Crimes" 2004 SAJELP 53-79 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Administrative Law and Implementation of Environmental Law" in King ND (ed) Fuggle and Rabie's Environmental Management in South Africa 3rd ed (Juta Cape Town 2018) 209-252 [ Links ]

Kidd M "Criminal Measures" in Paterson A and Kotzé L (eds) Environmental Compliance and Enforcement in South Africa: Legal Perspectives (Juta Cape Town 2009) 240-268 [ Links ]

Kidd M Environmental Law 2nd ed (Juta Cape Town 2011) [ Links ]

Kidd M The Protection of the Environment through the Use of Criminal Sanctions: A Comparative Analysis with Specific Reference to South Africa (PhD-thesis University of Natal 2002) [ Links ]

Kotze LJ "Environmental Governance" in Paterson A and Kotzé L (eds) Environmental Compliance and Enforcement in South Africa: Legal Perspectives (Juta Cape Town 2009) 103-128 [ Links ]

Kruger A Hiemstra's Criminal Procedure (LexisNexis Durban 2008-, 2018 update) [ Links ]

Murombo T and Munyuki I "The Effectiveness of Plea and Sentence Agreements in Environmental Enforcement in South Africa" 2019 PELJ 141 [ Links ]

Nurse A An Introduction to Green Criminology and Environmental Justices (Sage Thousand Oaks, CA 2016) [ Links ]

Paterson A and Kotzé L (eds) Environmental Compliance and Enforcement in South Africa: Legal Perspectives (Juta Cape Town 2009) [ Links ]

Robert S "No Double-Dipping: Rethinking the Tests for Duplication of Convictions" 2019 SALJ 489-512 [ Links ]

Skeen A St Q updated by Hoctor S "Criminal Law" in Joubert WA and Faris JA (eds) The Law of South Africa 3rd ed (LexisNexis Durban 2012-, 2017 update) vol 11 [ Links ]

Snyman CR Criminal Law 6th ed (LexisNexis Durban 2014) [ Links ]

Snyman CR Strafreg 4th ed (LexisNexis Butterworths Durban 1999) [ Links ]

Steyn E "Plea-Bargaining in South Africa: Current Concerns and Future Prospects" 2007 SACJ 206-219 [ Links ]

Strydom M "A Critique on Privately Prosecuting the Holder of 'After the Fact' Environmental Authorisations: Uzani Environmental Advocacy CC v BP Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd' 2021 SALJ 617-648 [ Links ]

Strydom M The Use and Impact of Criminal Sanctions for Environmental Law Transgressions in Industrial Facilities in South Africa: Determining the Boundaries of Overcriminalization (PhD-thesis University of the Witwatersrand 2022) [ Links ]

Terblanche S The Guide to Sentencing in South Africa 3rd ed (LexisNexis Durban 2016) [ Links ]

Watney M "Duplication of Convictions in Respect of Simultaneous Multiple Robberies: S v Toubie 2004 (1) SACR 530 (W)" 2005 TSAR 891-896 [ Links ]

Case law

Feedmill Developments (Pty) Ltd v Attorney-General, KwaZulu-Natal 1998 4 All SA 34 (N)

Mineral Sands Resources (Pty) Ltd v Magistrate Vredendal 2017 2 All SA 599 (WCC)

Mostert v The State 2010 2 SA 586 (SCA)

NDPP v Tutu Ndolose 2014 2 SACR 633 (ECM)

S v A Joubert (Paarl District Court) (unreported) case number A223/10 (date unknown)

S v Acker (Hermanus Regional Court) (unreported) case number ECH 100/05 of 1 October 2005

S v Aesthetic Waste Services (Pty) Ltd (Butterworth Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown)

S v Aid Safe Waste (Pty) Ltd (Benoni Regional Court) (unreported) case number 182/09 (date unknown)

S v Amro Natal CC (Pinetown Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC180/20 (date unknown)

S v Anker Coal (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number ESH 8/11 of 3 April 2012

S v Arbac Services CC (Germiston Magistrates' Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown)

S v Arcelor-Mittal South Africa Limited (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH118/19 (date unknown)

S v Blue Platinum Ventures 16 (Pty) Ltd (Lenyenye Regional Court) (unreported) case number RN126/13 of 30 January 2014

S v Bosveld Phosphates (Pty) Ltd (Phalaborwa Regional Court) (unreported) case number 5/01/2014 (date unknown)

S v D Groenewald (Pretoria Regional Court) (unreported) case number 14/493/2018 (date unknown)

S v Deva Kishorelal (Bronkhorstspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH105/17 (date unknown)

S v Die Straat Trust (Worcester Regional Court) (unreported) case number 3WRC2/2017 of 23 March 2017

S v E Adams (Bloemfontein Regional Court) (unreported) case number 18/174/18 (date unknown)

S v Emporium Base Minerals (Pty) Ltd (Germiston Regional Court) (unreported) case number 4SH100/17 (date unknown)

S v EnviroServ Waste Management Ltd (Durban Regional Court) (unreported) case number 41/540/20 (date unknown)

S v G Vyacheslav (Cape Town Regional Court) (unreported) case number H/63/2018 (date unknown)

S v Ganter Scrapmetals CC (East London District Court) (unreported) case number A1562/2013 (date unknown)

S v GM Mkhulise and TR Lepota (Benoni Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH431/12 (date unknown)

S v Golfview Mining (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number ESH 82/11 of 3 May 2013

S v Groenrivier Eiendomme (Pty) Ltd and Pieterse (Worcester Regional Court) (unreported) case number WSH 47/2017 of 18 May 2017

S v Haarburger 2002 1 SACR 542 (C)

S v Hanste (Pty) Ltd (Innovative Recycling) (Pretoria North Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH2/172/11 (date unknown)

S v Harrismith Galvanizing and Steel (Pty) Ltd (Harrismith Regional Court) (unreported) case number HSH91/12 (date unknown)

S v Inxuba Yethemba Municipality (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown)

S v JLH Serfontein and City Square Trading 323 (Pty) Ltd (Potchefstroom Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown)

S v John Henry Deale (Kroonstad Regional Court) (unreported) case number SHP95/14 (date unknown)

S v KL Makhubo, DG Zungo and KLM Drums Collectors CC (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC2014/11 (date unknown)

S v M de Scally (Pretoria North Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH2/216/10 (date unknown)

S v Melville (Kirkwood District Court) (unreported) case number A513/09 of 18 October 2010

S v Middleground Trading (Potchefstroom Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC66/2016 (2017)

S v MJ Lourens (Court unknown) (unreported) case number SH36/12 (date unknown)

S v Moosa Ali and JNR Joubert (Durban Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC201/18 (date unknown)

S v Nirove South Africa (Pty) Ltd (Motherwell Regional Court) (unreported) case number RCMW31/20 (date unknown)

S v Nkomati Anthracite (Nelspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH 412/13 of 28 August 2013

S v NM Selby (Eerstehoek Regional Court) (unreported) case number SHL131/2012 (date unknown)

S v Oil Separation Services CC (Mokopane Regional Court) (unreported) case numbers SH64/16 and 751/17 (date unknown)

S v Rand West City Local Municipality (Randfontein Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC 38/2020 (date unknown)

S v Richard Batson (George Regional Court) (unreported) case number G/SH187/10 (2011)

S v Rob Fonto (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC40/15 (date unknown)

S v Rodeo Solve CC (Camperdown Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC04/18 (date unknown)

S v RR Govender (Durban Regional Court) (unreported) case number 41/470/18 (date unknown)

S v SA Demolishers CC (Verulam Regional Court) (unreported) case number 1009/11/2010 (date unknown)

S v SAM Marie Consulting CC T/A Biotech SA (Pty) Ltd (Pinetown Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown)

S v Samancor Chrome Ltd (Lydenburg Regional Court) (unreported) case number SHL 472/2012 (date unknown)

S v Samancor Manganese (Pty) Ltd (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC217/15 (date unknown)

S v Silicon Smelters (Pretoria Regional Court) (unreported) case number 14/01477/2011 (date unknown)

S v SS Ngcobo, ML Serite and Iseewaste (Pty) Ltd (Kempton Park Regional Court) (unreported) unknown case number (date unknown)

S v Stefan Frylinck (Pretoria Regional Court) (unreported) case number 14/1740/2010 (2011)

S v T Mosekidi (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH152/09 (date unknown)

S v Thaba Chweu Local Municipality (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown)

S v Tierhoek Boerdery (Clanwilliam Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (2019)

S v UNICA Iron Steel (Pty) Ltd (Temba Regional Court) (unreported) case number E01/14 of 31 December 2013

S v Vunene Mining (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number 94/11/2010 (2011)

S v York Timbers (Nelspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH 865/2010 (2013)

S v Zinn 1969 2 SA 537 (A)

Sappi Ngodwana case (Mpumalanga) (unreported) SH 158/190 (date unknown)

Umhlaba Plant Hire CC v DPP Western Cape (10152/2015) [2015] ZAWCHC 161 (15 September 2015)

Uzani Environmental Advocacy v BPSA 2019 5 SA 275 (GP)

York Timbers (Pty) Ltd v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2015 1 SACR 384 (GP)

Legislation

Adjustment of Fines Act 101 of 1999

Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act 45 of 1965

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989

Hazardous Substances Act 15 of 1973

Magistrates' Court Act 32 of 1944

National Environment Laws Amendment Act 14 of 2009

National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998

National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004

National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004

National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003

National Environmental Management: Waste Act 59 of 2008

National Forests Act 84 of 1998

National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999

National Water Act 36 of 1998

Water Services Act 108 of 1997

Government publications

GN 1411 in GG 19435 of 30 October 1998

GN R1352 in GG 20606 of 12 November 1999 (Regulations Requiring that a Water Use be Registered)

GN R740 in GG 33487 of 23 August 2010 (Rules Regulating the Conduct of the Proceedings of the Magistrates' Courts of South Africa)

GN 217 in GG 37477 of 27 March 2014

Proc 1 in GG 27161 of 6 January 2005

Internet sources

Centre for Environmental Rights 2023 Judgments - Magistrates' Courts https://cer.org.za/virtual-library/judgments/magistrates-courts accessed 10 July 2023 [ Links ]

National Prosecuting Authority 2020 Annual Report 2019/20 https://www.npa.gov.za/sites/default/files/media-releasesZNPA_Annual_Report_2019-2020.pdf accessed 9 July 2023 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

CER Centre for Environmental Rights

CILSA Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa

CPA Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

DFFE Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment

EMI Environmental Management Inspector/s

Harv L Rev Harvard Law Review

NECER National Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Report

NEMA National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998

NPA National Prosecuting Authority

OJLS Oxford Journal of Legal Studies

PELJ Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal

SACJ South African Journal of Criminal Justice

SAJELP South African Journal on Environmental Law and Policy

SALJ South African Law Journal

TSAR Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg

Date Submitted: 6 April 2023

Date Revised: 9 August 2023

Date Accepted: 9 August 2023

Date Published: 23 November 2023

Guest Editors: Prof AA du Plessis, Prof LJ Kotze

Journal Editor: Prof C Rautenbach

* Melissa Strydom. LLB (UJ) LLM PhD (Wits). Attorney, South Africa. E-mail: melissastrydom29@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5226-4591. The underlying information and ideas for this article originates from my PhD research, guided by my supervisor, Prof Field. I thank my co-author, the peer reviewers and editors for their invaluable input, and officials who provided crucial information. The research was subject to ethics clearance (protocol number H18/11/31, 16 November 2018).

** Tracy-Lynn Field. BMus (UP)BProc LLB LLM (Unisa) PgDip Tertiary Education PhD (wis). Claude Leon Chair in Earth Justice and Stewardship, Professor, School of Law, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa and Advocate of the High Court of South Africa. E-mail: tracy-lynn.field@wits.ac.za. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2925-9449.

1 Hall 2022 PELJ 25.

2 Section 24 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution).

3 Including the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA), the National Environmental Management: Waste Act 59 of 2008 (the Waste Act); the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004 (the Air Quality Act); and the National Water Act 36 of 1998 (the National Water Act) - which are the focus of this research.

4 As provided for, in for example, ss 49A and 49B of NEMA, ss 67 and 68 of the Waste Act, ss 51 and 52 of Air Quality Act, and s 151 of the National Water Act.

5 Section 49B of NEMA.

6 Section 34(1)-(4) of NEMA.

7 Section 34(5)-(9) of NEMA.

8 Including Burns and Kidd "Administrative Law"; Craigie, Snijman and Fourie "Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Institutions"; Kotze "Environmental Governance"; Kidd "Criminal Measures"; Kidd Environmental Law. Several criminal law scholars were considered as part of the underlying PhD research on criminal enforcement; but are not referenced here as they do not cover environmental crimes in detail.

9 Kidd Protection of the Environment.

10 Kidd Environmental Law; Paterson and Kotze Environmental Compliance; Kidd "Administrative Law and Implementation of Environmental Law".

11 Kidd 2002 SAJELP 21; Fourie 2009 SAJELP 93.

12 Kidd 1998 SAJELP 183.

13 Kidd 2004 11 SAJELP 53.

14 Murombo and Munyuki 2019 PELJ 1.

15 Kidd 2002 SACJ 23; Kidd 2003 Obiter 186; Kidd 2003 SA Public Law 277.

16 Kidd 2004 CILSA 84.

17 Snyman Criminal Law 18-19.

18 The focus of this research.

19 Snyman Strafreg 19; Snyman Criminal Law 16.

20 Kidd "Criminal Measures" 241; see also Kruger Hiemstra's Criminal Procedure 284, Snyman Criminal Law 16, 18-19.

21 Kidd "Criminal Measures" 241-242.

22 Husak Overcriminalization 27 with reference to Holmes 1897 Harv L Rev 457.

23 Including Kidd Protection of the Environment; Kidd Environmental Law, Kidd "Criminal Measures"; Burns and Kidd "Administrative Law"; Craigie, Snijman and Fourie "Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Institutions"; Kotze "Environmental Governance".

24 Strydom Use and Impact of Criminal Sanctions. The research considered the cases within the context of overcriminalisation; the consideration of the cases for this article is more limited.

25 In terms of s 105A of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 (the CPA).

26 Defined in the NECER as the "pollution, waste and EIA (brown) sub-sector".

27 This may include a NEMA environmental authorisation, a Waste Act waste management licence, an Air Quality Act atmospheric emissions licence, a National Water Act water use licence or registrations.

28 Including the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999, the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004, the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003, the National Forests Act 84 of 1998, the Water Services Act 108 of 1997, the Hazardous Substances Act 15 of 1973, provincial laws and municipal by-laws.

29 As it is now known, and previously known as the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries and before that the Department of Environmental Affairs.

30 The first publicly available report.

31 This is the last report considered for this research.

32 Strydom Use and Impact of Criminal Sanctions, subject to ethics clearance (protocol number H18/11/31, 16 November 2018).

33 The purpose of the research was not to contact each official that may possibly have access to case information for concluded prosecutions. Considering the magnitude of officials tasked with enforcement, this was impossible from a time and cost perspective, and also not within the bounds of the underlying research. This case collection is thus limited to what was received.

34 S v Acker (Hermanus Regional Court) (unreported) case number ECH 100/05 of 1 October 2005 (hereafter S v Acker).

35 For example, the Sappi Ngodwana case (Mpumalanga) (unreported) SH 158/190 (date unknown) referred to by Kidd 2004 SAJELP 53.

36 Proc R1 in GG 27161 of 6 January 2005.

37 As part of the underlying PhD research.

38 Defined in the CPA as "any court established under the provisions of the Magistrates' Courts Act, 1944".

39 Defined in the CPA as "a court established for any district under the provisions of the Magistrates' Courts Act, 1944, and includes any other court established under such provisions, other than a court for a regional division".

40 NEMA s 34H(1).

41 Rules Regulating the Conduct of the Proceedings of the Magistrates' Courts of South Africa, published in GN R740 in GG 33487 of 23 August 2010.

42 CER 2023 https://cer.org.za/virtual-library/judgments/magistrates-courts.

43 Section 7 of the Magistrates' Court Act 32 of 1944.

44 For example, on SAFLII, and on a general case law search on platforms such as LexisNexis, there are at least 101 environmental cases available, although these are mostly civil in nature.

45 See for example, Feedmill Developments (Pty) Ltd v Attorney-General, KwaZulu-Natal 1998 4 All SA 34 (N).

46 See for example, NDPP v Tutu Ndolose 2014 2 SACR 633 (ECM); Umhlaba Plant Hire CC v DPP Western Cape (10152/2015) [2015] ZAWCHC 161 (15 September 2015); Mineral Sands Resources (Pty) Ltd v Magistrate Vredendal 2017 2 All SA 599 (WCC); S v Haarburger 2002 1 SACR 542 (C).

47 I.e., related to industrial-type offences or offences of NEMA, the Waste Act, the National Water Act, and the Air Quality Act.

48 Uzani Environmental Advocacy v BPSA 2019 5 SA 275 (GP) (hereafter Uzani Environmental Advocacy v BPSA); see Strydom 2021 SALJ 616.

49 A summary of the 53 prosecution records underlies this research; it was attached to the PhD thesis but is too lengthy to reproduce here (40 pages and 17643 words).

50 S v Vunene Mining (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number 94/11/2010 (2011).

51 S v Anker Coal (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number ESH 8/11 of 3 April 2012.

52 S v Golfview Mining (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number ESH 82/11 of 3 May 2013.

53 S v Blue Platinum Ventures 16 (Pty) Ltd (Lenyenye Regional Court) (unreported) case number RN126/13 of 30 January 2014 (hereafter S v Blue Platinum Ventures).

54 S v Middleground Trading (Potchefstroom Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC66/2016 (2017) (hereafter S v Middleground Trading).

55 Mostert v The State 2010 2 SA 586 (SCA) (hereafter Mostert v The State).

56 S v Tierhoek Boerdery (Clanwilliam Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (2019) (hereafter S v Tierhoek Boerdery).

57 S v Die Straat Trust (Worcester Regional Court) (unreported) case number 3WRC2/2017 of 23 March 2017.

58 S v Groenrivier Eiendomme (Pty) Ltd and Pieterse (Worcester Regional Court) (unreported) case number WSH 47/2017 of 18 May 2017.

59 S v Melville (Kirkwood District Court) (unreported) case number A513/09 of 18 October 2010 (hereafter S v Melville).

60 S v Stefan Frylinck (Pretoria Regional Court) (unreported) case number 14/1740/2010 (2011) (hereafter S v Frylinck).

61 S v Richard Batson (George Regional Court) (unreported) case number G/SH187/10 (2011) (hereafter S v Richard Batson).

62 S v York Timbers (Nelspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH 865/2010 (2013) and York Timbers (Pty) Ltd v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2015 1 SACR 384 (GP).

63 S v Rand West City Local Municipality (Randfontein Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC 38/2020 (date unknown); S v Thaba Chweu Local Municipality (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown); S v Inxuba Yethemba Municipality (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown).

64 Mostert v The State; S v A Joubert (Paarl District Court) (unreported) case number A223/10 (date unknown) (hereafter S v A Joubert); S v T Mosekidi (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH152/09 (date unknown) (hereafter S v T Mosekidi); S v M de Scally (Pretoria North Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH2/216/10 (date unknown) (hereafter S v M de Scally); S v Aesthetic Waste Services (Pty) Ltd (Butterworth Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown) (hereafter S v Aid Safe Waste); S v KL Makhubo, DG Zungo and KLM Drums Collectors CC (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC2014/11 (date unknown) (hereafter S v KL Makhubo); S v Silicon Smelters (Pretoria Regional Court) (unreported) case number 14/01477/2011 (date unknown); S v Richard Batson; S v Aesthetic Waste Services (Pty) Ltd (Butterworth Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown); S v Arbac Services CC (Germiston Magistrates' Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown) (hereafter S v Arbac Services); S v GM Mkhulise and TR Lepota (Benoni Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH431/12 (date unknown) (hereafter S v GM Mkhulise and TR Lepota); S v JLH Serfontein and City Square Trading 323 (Pty) Ltd (Potchefstroom Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown); S v NM Selby (Eerstehoek Regional Court) (unreported) case number SHL131/2012 (date unknown) (hereafter S v NM Selby); S v Hanste (Pty) Ltd (Innovative Recycling) (Pretoria North Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH2/172/11 (date unknown); S v Blue Platinum Ventures; S v Harrismith Galvanizing and Steel (Pty) Ltd (Harrismith Regional Court) (unreported) case number HSH91/12 (date unknown) (hereafter S v Harrismith Galvanizing and Steel); S v MJ Lourens (Court unknown) (unreported) case number SH36/12 (date unknown) (hereafter S v MJ Lourens); S v Bosveld Phosphates (Pty) Ltd (Phalaborwa Regional Court) (unreported) case number 5/01/2014 (date unknown); S v Deva Kishorelal (Bronkhorstspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH105/17 (date unknown) (hereafter S v Deva Kishorelal); S v John Henry Deale (Kroonstad Regional Court) (unreported) case number SHP95/14 (date unknown) (hereafter S v John Henry Deale); S v Oil Separation Services CC (Mokopane Regional Court) (unreported) case numbers SH64/16 and 751/17 (date unknown); S v Tierhoek Boerdery; S v Nirove South Africa (Pty) Ltd (Motherwell Regional Court) (unreported) case number RCMW31/20 (date unknown).

65 Strydom Use and Impact of Criminal Sanctions 137.

66 As contemplated in s 24 of the Constitution.

67 Craigie, Snijman and Fourie "Dissecting Environmental Compliance and Enforcement " 52.

68 Skeen "Criminal Law" para 9.

69 Skeen "Criminal Law" para 9; Brickey Environmental Crime 17; Husak 2004 OJLS 207; Duff et al Boundaries of the Criminal Law 255.

70 Kidd Environmental Law 276.

71 Nurse Introduction to Green Criminology 84.

72 Cameron 2020 SALJ 32.

73 Kidd Environmental Law 270-274; Kidd "Criminal Measures" 242-243.

74 Kidd Environmental Law at 269; Kidd Protection of the Environment 441.

75 Craigie, Snijman and Fourie "Dissecting Environmental Compliance and Enforcement " 53.

76 The underlying PhD research involved interviews with 32 key industry participants, the findings are not discussed in this article.

77 Section 31D of NEMA

78 Section 31G(1)(a) of NEMA.

79 Section 31G(1)(b) of NEMA.

80 Section 31H(1)(b) of NEMA.

81 Chapter 6 of the CPA.

82 Section 332(2) of the CPA.

83 Section 112(1) of the CPA.

84 Section 105A of the CPA.

85 Sections 112(2) and 113 of the CPA.

86 Section 115(1) of the CPA.

87 Section 115(2) of the CPA.

88 Section 6 of the CPA.

89 Steyn 2007 SACJ 207.

90 Steyn 2007 SACJ 207.

91 Section 105A(2)(a) of the CPA.

92 Section 105A(2)(b) of the CPA.

93 Section 105A(3) of the CPA.

94 Section 105A(4)(a) of the CPA.

95 Section 105A(8) of the CPA.

96 Section 105A(9)(a) and (b) of the CPA.

97 Section 105A(9)(c) of the CPA.

98 Section 105A(9)(d) of the CPA.

99 Section 105A(10) of the CPA.

100 Section 49B(1) and (2) of NEMA.

101 Section 68(1) and (2) of the Waste Act.

102 Section 52(1) of the Air Quality Act.

103 In terms of the Adjustment of Fines Act 101 of 1999 s 1(1)(a) read with the Magistrates' Court Act 32 of 1944 s 92(1)(b), a five-year imprisonment penalty could equate to a fine of R200,000. GN 217 in GG 37477 of 27 March 2014 determines that the fine a court can impose is "R120 000 where the court is not the court of a regional division, and R600 000 where the court is the court of a regional division", i.e., and which could impose 3- or 15-years imprisonment respectively, equating to a R40 000 per year fine.

104 S v Zinn 1969 2 SA 537 (A) 540G-H.

105 Husak Overcriminalization 27.

106 Kidd "Criminal Measures" 241.

107 Kidd "Criminal Measures" 241-242.

108 Husak Overcriminalization 50.

109 Husak Overcriminalization 146.

110 Including that overcriminalisation impairs the deterrent effect of punishment as explained by Skeen "Criminal Law" para 9.

111 Husak Overcriminalization 146.

112 Strydom Use and Impact of Criminal Sanctions 137.

113 Cameron 2020 SALJ 32.

114 On the assumptions that the base data for the calculations are correct, although there may be variables that are not apparent from the information obtained.

115 For example, the information is often contained in brief summaries in the NECERs, SAP69 forms (the South African Police Service form that captures criminal convictions), sentencing annexures containing only the sentence imposed. Where limited documents are provided, it is not always possible to determine the charges the accused faced.

116 S v Frylinck; S v Middleground Trading; Uzani Environmental Advocacy v BPSA.

117 Mostert v The State; S v York Timbers (Nelspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH 865/2010 (2013); S v Blue Platinum Ventures.

118 S v Acker (Hermanus Regional Court) (unreported) case number ECH 100/05 of 1 October 2005.

119 S v Melville (Kirkwood District Court) (unreported) case number A513/09 of 18 October 2010.

120 S v Aid Safe Waste (Pty) Ltd (Benoni Regional Court) (unreported) case number 182/09 (date unknown).

121 S v Vunene Mining (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number 94/11/2010 (2011).

122 S v Anker Coal (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number ESH 8/11 of 3 April 2012.

123 S v Golfview Mining (Ermelo Regional Court) (unreported) case number ESH 82/11 of 3 May 2013.

124 S v Nkomati Anthracite (Nelspruit Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH 412/13 of 28 August 2013.

125 S v Ganter Scrapmetals CC (East London District Court) (unreported) case number A1562/2013 (date unknown) (hereafter S v Ganter Scrapmetals).

126 S v UNICA Iron Steel (Pty) Ltd (Temba Regional Court) (unreported) case number E01/14 of 31 December 2013.

127 S v Samancor Chrome Ltd (Lydenburg Regional Court) (unreported) case number SHL 472/2012 (date unknown).

128 S v Bosveld Phosphates (Pty) Ltd (Phalaborwa Regional Court) (unreported) case number 5/01/2014 (date unknown).

129 S v Rob Fonto (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC40/15 (date unknown) (hereafter S v Rob Fonto).

130 S v Samancor Manganese (Pty) Ltd (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC217/15 (date unknown).

131 S v Die Straat Trust (Worcester Regional Court) (unreported) case number 3WRC2/2017 of 23 March 2017.

132 S v Groenrivier Eiendomme (Pty) Ltd and Pieterse (Worcester Regional Court) (unreported) case number WSH 47/2017 of 18 May 2017.

133 S v Rodeo Solve CC (Camperdown Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC04/18 (date unknown).

134 S v G Vyacheslav (Cape Town Regional Court) (unreported) case number H/63/2018 (date unknown) (hereafter S v G Vyacheslav).

135 S v SA Demolishers CC (Verulam Regional Court) (unreported) case number 1009/11/2010 (date unknown).

136 S v D Groenewald (Pretoria Regional Court) (unreported) case number 14/493/2018 (date unknown) (hereafter S v D Groenewald).

137 S v SAM Marie Consulting CC T/A Biotech SA (Pty) Ltd (Pinetown Regional Court) (unreported) (unknown case number) (date unknown).

138 S v E Adams (Bloemfontein Regional Court) (unreported) case number 18/174/18 (date unknown) (hereafter S v E Adams).

139 S v SS Ngcobo, ML Serite and Iseewaste (Pty) Ltd (Kempton Park Regional Court) (unreported) unknown case number (date unknown) (hereafter S v SS Ngcobo).

140 S v RR Govender (Durban Regional Court) (unreported) case number 41/470/18 (date unknown) (hereafter S v RR Govender).

141 S v Arcelor-Mittal South Africa Limited (Vereeniging Regional Court) (unreported) case number SH118/19 (date unknown).

142 S v Amro Natal CC (Pinetown Regional Court) (unreported) case number RC180/20 (date unknown).

143 S v EnviroServ Waste Management Ltd (Durban Regional Court) (unreported) case number 41/540/20 (date unknown).

144 Mostert v The State 2010 2 SA 586 (SCA).

145 S v Richard Batson (George Regional Court) (unreported) case number G/SH187/10 (2011).