Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.26 no.1 Potchefstroom 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2023/v26i0a17260

SPECIAL EDITION: ENVIRONMENTAL & ENERGY LAW

South African Environmental Law and Political Accountability: Local Councils in the Spotlight

N Ngcobo

North-West University, South Africa. Email: nonhlanhlangcobo9@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The world is facing an environmental crisis threatening human and non-human existence. Various actors are responding to this crisis, including politicians, international non-governmental organisations, transnational organisations and scientific communities. Municipalities are governing entities in cities and are deemed critical actors to help respond at a sub-national level to the global environmental crisis. In terms of sections 151(2) and 156(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution) municipal councils have executive and legislative authority over local environmental governance (LEG) matters listed in Schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution, thus making municipal councils the highest South African authority with legal and political powers in local communities. This article uses the constitutions, policies, and manifestos of political parties active in the local government sphere to ascertain the role of political parties in (local) environmental governance. The aim of this inquiry is to investigate how political parties in South Africa conceive of their accountability in the environmental governance context. The assumption is that unless councillors are politically inclined and are expressly expected at party level to pursue ecologically sustainable development, municipalities will not be able to fulfill their role in the urgently needed transition. The article finds that municipal councils are accountable for environmental governance and should improve on this responsibility. The accountability should start with parties making explicit environmental commitments and holding their councillors accountable for failing to fulfil them.

Keywords: Municipal councils; Constitution; political parties; local government; environmental law and governance; South Africa.

1 Introduction

The world is facing an environmental crisis threatening human and non-human existence.1 This crisis includes resource depletion, environmental degradation, a decline in biodiversity, climate change and mounting air, soil and water pollution.2 Scientists predict these problems will become more pressing due to unprecedented urbanisation and world population growth.3 Various actors are responding to this environmental crisis, including politicians, international nongovernmental organisations (INGOs), transnational corporations (TNCs) and the scientific community.4 This is because these actors are realising that environmental protection is a common responsibility of all human beings, requiring the full participation of all global actors.5

Municipalities are governing entities in cities and their actions are deemed critical to the response to the global environmental crisis.6 This is because, while bilateral and multilateral agreements are negotiated and adopted by national governments, their implementation happens at city level.7 The same holds for South Africa to the extent that municipalities are governing authorities in the local government sphere. In terms of section 2 of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 (Municipal Systems Act), a municipality is an organ of state in the local sphere of government exercising legislative and executive authority and consists of the political structures, the administration, and the community of a municipality. Municipalities further exercise their legislative and executive authorities in the constitutional system of co-operative government envisaged in section 41 of the Constitution.

The political structures of municipalities are the highest governing authorities in municipalities.8 In terms of the Constitution, the executive and legislative authority of a municipality is vested in its municipal council, which has the right to govern the local government affairs of its community, subject to national and provincial legislation.9 Furthermore, national and provincial government may not compromise or impede a municipal council's ability or right to exercise its powers or perform its functions, including its powers and functions with respect to the environment.10 Municipal councils consist of councillors who are affiliated with their political parties and representatives of local communities.11 Municipal councils thus exist in a unique space where community politics and party politics coincide and interact.

The politics of councillors (and municipal councils) is that they are guided in the first instance by their political parties' constitutions, policies and manifestos. This is despite the pronouncements of the Constitution and the Code of Conduct for Councillors, which state that councillors must always act in the interest of their municipalities by providing a political link between the municipal council and the community.12 Therefore, the environmental governance stance of the political parties matters.

It follows, therefore, that the accountability of political parties in environmental governance is premised on the fact that members of these parties eventually become councillors in municipal councils. This article investigates how political parties operating in the local government sphere conceive of their accountability in the environmental governance context in terms of aspects of South African local government and environmental law. To achieve this investigation, the first section of the article will discuss the role of politics in (local) environmental governance. This discussion is anchored in international environmental politics (IEP), which holds that environmental issues are increasingly becoming a political agenda of significant importance.

The second part of the article will discuss the significance of South African politics in environmental governance. This part will highlight how the Constitution has restructured the governing system in local government, making municipal councils and councillors the highest environmental governance authorities in municipalities and also positioning them as a meeting point for global environmental politics, parochial community politics and party politics. The third section of the article will consider the accountability of municipal councils in South Africa through the lens of the Constitution and local government and environmental law legislation. This section will also discuss some jurisprudence where the court found that municipal councils were accountable for environmental protection and degradation, as well as the right of local communities to an environment that is safe for their health and well-being. The fourth section is an appraisal of the constitutions, policies and manifestos of (local) political parties in South Africa. This section evaluates the above instruments to ascertain the environmental governance stance of these parties, including the extent to which these parties are liable for advancing environmental governance in South Africa. The fifth section concludes the article. The article is a desktop-based investigation and an interdisciplinary study of law and politics.

2 The role of politics in (local) environmental governance

2.1 The role of politics in international environmental governance

Global environmental issues were not a political concern until the 20th century when it became apparent that humans were having an increased effect on the earths' ecosystem.13 This realisation led to a response by political actors which culminated in the first conference on the global environmental crisis, namely the Stockholm Conference, 1972 (the Conference).14 This Conference led to the establishment of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the establishment of environmental departments in the governments of several states. What is noteworthy about the Conference is that owing to its policy of apartheid South Africa did not participate in the process of establishing UNEP.15 South Africa also failed to meaningfully contribute to the participatory process that followed the Conference, including conventions and agreements.16 Furthermore, the country was also not invited to become a member of the governing council of UNEP in 1973.17 Therefore, the isolation of South Africa in international environmental governance amongst other things is evidence that ecological issues have become a global political agenda of importance.18

IEPs does not have a concise definition. It is premised on the understanding of scholars that the environment (and its governance) is influenced by states, global institutions, the political economy, theories of international relations (IRs) and, in recent decades, subnational governments, among other things.19 The general theme of political science scholars writing on the topic of IEP is that the notion refers to a realm where global actors pursue environmental interests through contestation, collaboration and discourses using power, authority and organisational ability.20 In this realm political actors across different nations perform actions, including developing and adopting environmental policies, yet in some instances these actors fail to act for the environment.21

Cities and their governing structures are at the receiving end of the positive and negative actions of actors in IEP.22 For instance, the positive action is that cities implement conventions and treaties that are negotiated by national governments. The negative action is that cities suffer from the environmental consequences of degradation and pollution. A recent addition to the pressure of cities in IEP is the urban goal added to the UNs Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 11 states that by 2030 cities and human settlements should be inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.23 The goal suggests that political leaders in cities are increasingly being seen as key to promoting human resilience to environmental shocks, improving peoples' livelihoods and fostering ecologically sustainable development on a global scale.24 Cities have become sites for struggles around devolution and urban autonomy. The political regime of a country determines the self-governing status of subnational governments and the extent that city leaders can play a role in IEPs. For instance, where power has been decentralised from federal to subnational governments, cities can directly influence environmental governance. This is the situation of South African cities, whose governing authorities have powers and functions vested in the Constitution.

2.2 The role of party politics in South Africa's (local) environmental governance

With South Africa being a constitutional democracy, the Constitution has captured the global concern of an ecologically deteriorating environment in a constitutional environmental right.25 Du Plessis and Kotzé state that concretising the right in the Constitution creates an obligation for the state to protect the right and ensure that its organs comply with its standards.26Furthermore, concretisation enables judicial intervention where the right is under threat.27

As stated above, the inception of the Constitution in South Africa has also altered the role of politics in the Country by allowing political parties to determine the leadership of a municipality. This is different from the previous governing regime of apartheid, where municipalities were elected by the white minority and governed by provincial councils with limited legislative power.28As the highest authorities in municipalities, local councils specifically make decisions concerning the exercise and performance of all the functions of municipalities, including matters relating to the environment and peoples' health and well-being.

Councils comprise councillors (functionaries of the local government system representing the community) who are representatives of their parties.29 This means that councillors inter alia play an oversight role in the work of municipal public servants (the administration) on behalf of the community (the electorate).30 This function entails receiving implicit and explicit mandates from the community and reporting back to such communities, especially on the municipality's performance. Municipal councils provide a place where community politics meet party politics and where local policies are supposed to originate and be implemented through these interactions.

As elected politicians in the South African political systems, however, councillors are also expected to advance their political parties' purpose, policy, and ideals. These purposes, policies and ideals are often reflected in the constitutions, policies, and election manifestos of the parties. The relevance of this lies therein that:

Political parties play a unique and crucial role in our democratic system of government. Parties enable citizens to participate coherently in a system of government, allowing for a substantial number of popularly elected offices. They bring fractured and diverse groups together as a unified force, providing a necessary link between the distinct branches and levels of government, and provide continuity that lasts beyond the term of office. Parties also play a role in encouraging active participation in politics, holding politicians accountable for their actions, and encouraging debate and discussion of important issues.31

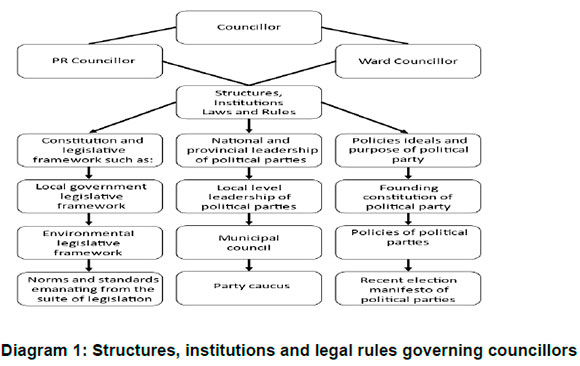

This statement points to the general role of parties. However, in the South African local government context it is quite possible that a political party may fail to deliver what it promises during election time. This is because party leadership at national level sometimes takes decisions meant to be deliberated and decided on by local leaders in municipal councils, undermining the role of councillors in the local government sphere.32 In such instances councillors or councils find it difficult to challenge national leadership for fear that they may be removed from the party lists and subsequently removed as councillors. Below is a diagram that illustrates the complex role of councillors in environmental governance as political office bearers whose conduct is guided by the Constitution and local government and environmental law legislation, as well as the purpose, policies, and ideals of their affiliated political parties.

The above diagram illustrates how councillors serve in their parties and, by virtue of their political office, in party caucuses and municipal councils.33 All have rules that councillors should abide by. It is not controversial for councillors to abide by the ideals and policies of their political parties, but this must be balanced with their mandate as community representatives that employ them to function within a set of legal rules determined by the Constitution, local government law and environmental legislation. Thus, councillors are dealing with a conflation of accountability. For instance, the electorate or community conceivably holds councillors accountable for delivering on the promises made in manifestos, and they are subject to internal party discipline which would insist on the implementation of the parties' manifesto and policy.

3 Accountability of municipal councillors in South Africa through the lens of domestic constitutional, local government and environmental law and jurisprudence

3.1 The Constitution

The Constitution is a framework within which flow all duties, powers, functions and responsibilities of councillors with respect to the environment. As stated before, section 24 of the Constitution captures the global concern with the deteriorating environment. This section enunciates the substantive right of people to an environment that is not harmful to their health and well-being.34When read with sections 7(2) and 8(1) of the Constitution, this right compels local authorities, together with the other spheres of government, to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the right of people to an environment that is not harmful to their health and well-being. This right applies both horizontally and vertically, thus imposing a duty on other people, political parties and local authorities, among others, to refrain from activities that are likely to infringe on the right of people to enjoy this right. Section 24(b) states that the environment must be protected through reasonable and legislative measures to secure ecologically sustainable development. This section enjoins municipal councils to use their legislative powers to enact by-laws to protect the environment. Section 151 of the Constitution states that the executive and legislative authority of a municipality is vested in its municipal council.35 A municipality has the right to govern, on its own initiative, the local government affairs of its community, subject to national and provincial legislation as provided in the Constitution.36

The attempts made by municipal councils to regulate the environment must be forward-looking. This means that the environment must be protected for the current and future generations. In Fuel Retailers Association of South Africa v Director General: Environmental Management, the Court found that the Constitution recognises the interrelationship between the environment and development in so far as it envisages that any development should be balanced against the consideration of nature and its resources.37

The functions of local government found in Schedule 4B and 5B of the Constitution are part and parcel of the duty to prevent soil, air and water pollution and the decay of local ecological systems.38 This requires an uninterrupted provision of services by councils, including municipal health services, stormwater management, water and sanitation services limited to potable water supply systems, domestic waste-water and sewage disposal systems, and refuse removal and waste disposal services. If councils do not execute their functions, they fail in their constitutional mandate. Such a failure is answerable to the communities that have elected the councillors.39

3.2 Local Government: Municipal Systems Act and Municipal Structures Act

A suite of legislation affirms the accountability of municipal councils and councillors to environmental protection and governance.40 Section 11 of the Municipal Systems Act states that municipal councils take all decisions of the municipality.41 Councils should govern the environmental affairs of communities using legislative and executive authority, including developing environmental policies, plans, strategies, and programmes.42 Councils must set targets for service delivery and accompany these targets with green budgets, among other things.43 One of the key strategies of a municipality is the integrated development plan (IDP), which allows councils to identify environmental issues in their community and mainstream these across all other plans of their municipality.44 It is the duty of councillors to identify environmental issues that should be addressed by way of prioritising them in the IDP. Section 26(a) of the Act states, for instance, that the IDP of a municipality must reflect the municipal council's vision for the long-term development of the municipality with special emphasis on the municipality's most critical development issues. This is important, considering that no development can occur in a deteriorating and chronically polluted environment.

The Municipal Systems Act enjoins councils to create a culture of community participation in matters of local government.45 Political parties have been known to participate actively in matters of local government, whether their members serve as councillors or not, without imposing or interfering with the decision-making powers of the municipality. One way of doing this is through ward committees. Ward councillors often constitute their ward committees with members of their own political parties to act as advisors to the councillor. In order to retain power in the committee, the ward councillor serves as chairperson. Despite this, a ward committee's pivotal role is to serve all community members' needs regardless of their affiliation.46

Other committees or structures enhancing environmental governance by political office-bearers include sections 79 and 80 committees. Each of these committees may be created by the council or the executive mayor of a municipality and given a specific duty related to environmental protection. The committee may be tasked with developing a by-law, policy or strategy relating to environmental protection or with making recommendations to municipal councils on the most effective way to deal with environmental issues or with general oversight in environmental governance matters.

Section 80 committees specifically report to the executive mayor or committee. Therefore, executive mayors are arguably the most powerful members of the municipal council.47 The powers and functions of an executive mayor include identifying the environmental needs of the municipality, reviewing and evaluating these needs in order of priority, and recommending to council strategies, programmes and services to address environmental needs through the IDP and estimates of revenue and expenditure.48 It is critical, therefore, for a political party to recruit and nominate people into public office who understand the environmental governance issues of their municipalities and dedicate themselves to solving them.

3.2.1 NEMA and SEMAS

There is a variety of pieces of legislation, including sector-specific legislation applicable to the duty of municipal councils to the environment in environmental law, all of which are executed in accordance with the principles of the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA) as framework legislation.49 NEMA is laden with principles that foster integrated environmental management across all spheres of government, including the State's responsibility to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights in the Bill of Rights in the Constitution, to place people and their needs at the forefront of its concerns, and serve their physical, psychological, developmental, cultural and social interests equitably.50 Other principles in NEMA include the duty of care and the precautionary principle, which require that any person who causes or may cause pollution or degradation of the environment take reasonable measures to prevent this from occurring.51 Therefore, municipal councils must take reasonable measures to prevent their municipalities from failing to deliver on environmentally related services such as refuse collection and sanitation.

Throughout the Act, NEMA refers to the environment as being held by the state in public trust for the people.52 This further invokes the accountability of councils to preserve nature and its endowments in a manner espoused in various SEMAs for the benefit of the current and future generations, a tenet of the principle of sustainable development.

The wording of the Constitution and legislation makes it difficult for us to distinguish between the responsibilities of councils or municipal councillors in environmental governance. This legal framework broadly refers to "municipalities" with scant reference to ''municipal councils'' or ''councillors''. It is safe to state that this deficit in the legal framework of (local) environmental governance is compensated for by understanding that municipal councils are the highest authority in municipalities.

3.3 Judicial pronouncements on the accountability of councils/councillors involved in environmental governance

The courts in South Africa have made some assertions on the accountability of municipal councils regarding environmental matters where their failure to act positively or their negative actions have violated their environmental mandate and people's right to a safe and healthy environment. These pronouncements are addressed below.

3.3.1 Marius Nel v Hassequa Local Municipality

The Hessequa and Swellendam Local Municipalities adopted by-laws (between 2012-2013) relating to the management and use of rivers in their areas, which sought to regulate boating activities, requiring boat users amongst other things to be licensed by the municipalities; the consequence of which required users to pay licence and cancellation of licence fees.53 Additionally, municipalities would fix tariffs, fees, and levies with respect to the registration and licensing of boats.54 The by-laws also prohibit some behaviours relating to using boats, fishing and other activities, including operating boats recklessly while under the influence of alcohol or drugs, operating an overloaded boat or one that is leaking pollutants.55

The applicants approached the High Court to declare the adopted by-laws unconstitutional and in conflict with national legislation.56 The applicants did so on several grounds, including that municipalities do not have the powers to legislate on the use of rivers.57 The Court held that it is permissible for a municipality to make and administer by-laws requiring that people who wish to use boats on rivers be licensed and to authorise officers to enforce such by-laws.58 The Court reasoned that section 156, read with schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution gives municipalities the power to regulate the use and management of rivers in their areas.59 Although ''rivers'' are not explicitly listed in schedules 4B and 5B, public amenities, public places and places of recreation include rivers. Therefore, the Court affirmed the right of councils to legislate on environmental governance matters.

3.3.2 Featherbrook Homeowners Association NPC v Mogale City Local Municipality

In this case the Court had to consider whether municipalities have a duty to undertake measures to mitigate stormwater flooding in terms of their climate change policies and whether doing so is part of fulfilling their obligations in terms of the constitutional environmental right.60 It followed that the applicant applied for an interim structured supervisory interdict to the High Court seeking relief against several state entities, including Mogale City Local Municipality, where it sought relief from the constant overflooding of the Muldersdrift Se-Loop River that traversed the jurisdiction of the Municipality and the City of Johannesburg.61 The Court had to decide on this question based on the allegations made by the applicant that despite numerous pleas and engagements, the Municipality had failed to provide any stormwater mitigation, adaptation and prevention as far as chronic stormwater flooding was concerned.62 According to the applicant, annual rains had increased the water flow and stormwater into the area since 2010, placing pressure on the river's embankment and beds, thus corroding them and making them highly unstable and leading to floods.63 The flooding threatened security fences adjacent to the riverbed and exposed municipal infrastructure, including sewer pipes and electric cables.64 The Court held the municipal council of Lesedi Local Municipality accountable for its failure to mitigate the environmental issues in so far as the Municipality failed to meet its duties in terms of section 24 of the Constitution. The Municipality had failed to provide the local community with an environment that is not harmful to their health and well-being.65 This section of the legislation also states that the government is obliged to adopt legislative measures to prevent pollution and ecological degradation, which the Municipality had failed to do.66

3.3.3 Maccsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town

One of the functions of local government in relation to the environment is municipal planning. The municipal council of the City of Cape Town admitted being fully aware of this.67 In this case the then Minister of Mineral Resources, acting in terms of section 27 of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act 28 of 2002 (MPRDA), granted a mining permit to Maccsand (Pty) Ltd, authorising it to mine sand on the Rockland Dunes.68 These dunes are located in a residential area between two schools and close to private homes. However, in terms of the Land Use Planning Ordinance 15 of 1985 (LUPO), which is a provincial law, unless the land in question was rezoned by the City of Cape Town from residential, Maccsand could not mine in the area.69Based on LUPO, the City interdicted Maccsand, restricting them from mining in the area unless rezoning happened.70 The City extended the application, stating that authorisation in terms of NEMA was also necessary for Maccsand to mine the area.71

Maccsand and the Minister contended that mining was an exclusive competence of the national government72 and that LUPO therefore did not apply because the Act regulated a municipal functional area.73 Furthermore, applying LUPO in a mining area would be inconsistent with the Constitution.74

The Court rejected the arguments that LUPO was not applicable.75 It also rejected claims that the MPRDA adequately provided environmental protection and that NEMA was not necessary.76 In rejecting the claims, the Court found that while the MPRDA regulates mining activities, LUPO regulates land use.77Therefore, the two Acts did not encroach on each other. The City of Cape Town had a duty to ensure that any activity that happened in its area aligned with the zoning rules. This meant that although the City had not rejected the prospect of mining in the area, it held that unless the area was rezoned mining was impermissible. It was evident from the City's reasoning that until such rezoning had taken place, an environmental impact assessment in terms of section 24 of NEMA would be necessary in order to ensure that mining would not cause severe harm to the area. This showed a commitment by the City to protecting the environment from harmful activities. Furthermore, the effect of interdicting Maccsand was to protect the land from unlawful activities that would lead to environmental degradation.

3.3.4 Trustees for the time being of Groundwork Trust v Minister of Environmental Affairs

This case concerned the accountability of municipal councils to prevent chronic air pollution in the area. The applicant sought declaratory and mandatory relief concerning the extent of governments' obligation regarding continuous air pollution emission in the Highveld Priority Areas.78 According to the applicant, the council as an organ of state had violated section 24(a) of the Constitution in so far as the provision affords everyone the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health and well-being.79 It argued that not all air pollution violates the right to a healthy environment, but if air quality did not meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standard this was a prima facie violation of the right.80 The area in question covers some of the most heavily polluted towns in the Country, including Middelburg, eMalahleni, Secunda, Standerton, Benoni and Boksburg. The area contains twelve of Eskom's81 coal-fired power stations and Sasol's82 coal-to-liquid fuels refinery. Due to the concentration of sources of industrial pollution in the environment, residents experience poor and dangerous air quality.83 The Court held that the poor air quality in the Highveld Priority Area was in breach of section 24(a) of the Constitution and that this right, like the right to basic education, was immediately realisable.84 The decision of the Court enjoined the Council of Emalahleni Local Municipality to develop and adopt a policy that would direct the actions of the Municipality to mitigate air pollution in the area.

3.3.5 Beja v Premier of the Western Cape

This case concerns the responsibility of municipal councils to provide water and sanitation, the absence of which would endanger the life, safety, health and well-being of people and the environment. The applicants in this case approached the Court seeking relief to declare the conduct of the City of Cape Town unlawful and in violation of the Constitution.85 The application followed when the City of Cape Town erected 1316 toilets, including 51 open toilets, which subjected the community to degrading circumstances, including using public toilets in the full view of passers-by.86 Finding in favour of the applicant, the Court reasoned that the City had violated sections 24 and 27 of the Constitution.87 The objectives of municipal councils are to provide services to communities in a sustainable manner and to promote a safe and healthy environment.88 This is in line with the duty of municipal councillors to provide the basic services necessary for advancing human health and well-being.89

3.3.6 Mazibuko v City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality

In this case the Court was called upon to consider the link between municipal councils providing access to water (as a right of the people living in local communities) and their duty to manage the sustainable use of water (as co-trustees of the community's natural resources).90 The residents of Phiri, Soweto (the applicants) were challenging the City of Johannesburg's free basic water policy in terms of which six kilolitres of water were provided monthly free of charge to all households in Johannesburg, and the lawfulness of the installation of pre-paid water meters in the community.91 The Court found that it could not be said that it was unreasonable for the City not to have supplied more, especially given that the Municipality still had the duty to supply over 100,000 households with access to basic water services.92 Therefore, the municipal council of the City of Johannesburg had a duty to adopt policies (such as Operation Gcin'amanzi) reasonably necessary for effective environmental governance responsibilities concerning the sustainable use of and preservation of water.93

3.3.7 City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality v Blue Moonlight Properties

This case did not necessarily deal with environmental matters found in Schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution. It highlighted the responsibility of municipal councils to develop and adopt relevant policies and by-laws necessary for the effective administration of socio-economic rights in South Africa. The case also highlighted that, in line with the co-operative governance mandate of municipalities, councils could not escape their constitutional duties to advance socio-economic rights in the Constitution. In this case the Court dismissed an argument of the City of Johannesburg that it did not have the responsibility to provide temporary accommodation to a person who, after eviction from a private property, would be left destitute.94 It reasoned that the City was responsible for providing temporary accommodation in fulfilling the socio-economic right enunciated in section 26 of the Constitution. The Court made it clear that local governments have a duty to provide adequate housing as part of their developmental duties in sections 152 and 153 of the Constitution.95 Furthermore, the developmental duties of municipalities must be considered against the responsibilities of local government in terms of the Municipal Systems Act, including providing basic services that are necessary to ensure an acceptable and reasonable quality of life.96

3.3.8 Kgetlengrivier Concerned Citizens v Kgetlengrevier Local Municipality

This case concerned the unlawful act of a municipal manager in failing to adequately respond to the outcry of community members in Kgetlengrevier Local Municipality. The accountability of the municipal council in this regard was found in its failure to oversee the work of the municipal manager as an employee of the council. In December of 2020 an urgent application had been made by the residents of Kgetlengrivier against their Municipality and its Municipal Manager regarding their failure to provide adequate water and to prevent the Municipality from polluting two rivers with untreated sewage.97 The Court found that the Municipality's actions constituted a violation of the community's constitutional environmental right.98 As such, it ordered that the Municipal Manager be imprisoned for ninety days should the sewage pollution persist without being remedied.99 The Court also ordered that sufficient, potable water should be provided within ten weeks.100 The provisions referenced by the Court in finding in favour of the local community, including sections 24, 27 and 151 of the Constitution, were found to be applicable to the municipal council of Kgetlengrevier Local Municipality, which could not distance itself from the consequences of the Courts' judgement based on the pronouncement by the Court that the municipal manager should face imprisonment.

In essence, the Constitution and a suite of local government and environmental law legislation were used by the courts in these cases to reach a decision that found that municipal councils are responsible for environmental governance issues in their jurisdictions. The Constitution confers original legislative and executive authority on municipal councils.101

4 Provision for environmental governance accountability: an appraisal of the constitutions, manifestos, and party policies of local political parties in South Africa

This section of the article is an appraisal of the constitution, policies, and manifestos of (local) political parties in South Africa. It investigates the above instruments to ascertain the perceived accountability of political parties in the environmental governance context. In order to achieve this, the author asks three distinct questions. Firstly, what does addressing environmental issues in municipal councils entail? Secondly, what are the party and the councils governed by the party currently doing with regard to environmental governance? Thirdly, what should be done by municipal councils to improve environmental governance? The parties selected for this investigation include some of those that were registered and stood for election in the 2021 local government election. The Green Party is excluded from this investigation because it contested the elections in the City of Cape Town only.

4.1 Action SA

Action SA is a relatively new political party. It was established in 2020 by the former mayor of the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, Herman Mashaba, after he left the Democratic Alliance.102 Action SA contested elections for the first time in the 2021 Local Government Elections. The Party states on its official website that it seeks to provide a credible alternative to what it views as "a broken political system that has failed the people of South Africa since the dawn of democracy".103 It is also stated that, as its name suggests, the Party's focus is on "action" to move South Africa forward from an era of broken promises, corruption and failed government.

Action SA recognises that there is an ongoing battle against climate change and further states that it will commit to international imperatives to fight climate change and integrate sustainability into operating models.104 Clean air, water and waste are singled out as priority areas for the party in its local government election manifesto (2021 ), and it further indicates that its municipalities will take better care of the environment by promoting a culture of reducing, reusing and recycling solid waste to deal with pollution from waste.105

There is a need for urgent action in local councils driven by committed leadership to ensure adaptation to and mitigation of climate change.106 This action includes national government allowing local municipal councils and individuals to procure renewable electricity directly from independent power producers (IPPs).107

As of the last local government elections (2021), Action SA is not governing any municipal councils. As such, they do not have a record of what their Party has done to improve LEG. However, the Party appears to be dedicated to positive action towards environmental improvement at the local level, including to "take progressive action to improve air quality and ensure that all residents have access to potable drinking water that meets stringent health standards".108 The assumption is that the "stringent health standards" refer to those found in the relevant legislation, including the Water Services Act 108 of 1997 and National Health Act 61 of 2003. This proposal is not new, nor is it too ambitious. It is in fact a responsibility of local government to provide communities with access to services limited to potable water supply systems and air quality management. Furthermore, the Party wants to protect biodiversity by holding accountable those that cause damage to the environment.109 The Party does not say how it intends to do this.

4.2 African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a well-established political party. It was established in 1912 as a socio-democratic political party known for its role in the opposition to and struggle against apartheid.110 The ANC has been the dominant party in the South African government since the inception of democracy in 1994.111 In its latest constitution (2017) the Party states that its primary objective is to construct a "united, non-racial, non-sexist, democratic and prosperous society in South Africa".112 As the governing party the ANC inherited a fragmented policy and legal framework which required an overhaul of almost all legislation, including the existing environmental laws and policies. NEMA, the relevant framework legislation, is a result of the environmental policy development process of the ANC known as the Consultative National Environmental Policy Process (CONNEP), which was launched in August 1995.113

According to the Party, dealing with environmental issues in municipal councils entails that municipalities address water loss due to poor maintenance, refuse not being collected regularly, and raw sewage flowing in the streets.114 As such, the Party proposes a focus on developing and maintaining water and sewerage infrastructure, and, where such infrastructure exists, rehabilitating it.115 In its January 8th 2023 statement, the Party noted how the collapse of municipalities in South Africa has devastated communities that deal with chronic water loss due to poor maintenance, refuse not being collected regularly, and raw sewage flowing in the streets.116 Electricity (or the lack thereof) is also recognised as an environmental governance issue that requires the Party to take steps to solve it. The ANC is one of the few parties analysed that has a track record in environmental governance. The language used in its instruments suggests that the Party ''acknowledges'' its failures. However, the existing instruments do not provide details on how they would solve their environmental governance challenges.

The Party proposes that municipal councils need to increase their contribution of renewable energy to the country's energy mix through the diversification of their energy sources.117 The Party further states that there is a need for a just transition from reliance on coal to renewable energy that creates new economic opportunities for workers and communities.118 The Party further seeks to oversee the retirement of ageing coal-powered stations to improve the air quality for communities by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.119 The ANC national government has moved towards fulfilling this promise by allowing local government to generate or procure electricity from IPPs.120

4.3 African Transformation Movement

The African Transformation Movement (ATM) was established in 2018.121 ATM is a faith-based political party established to create and develop a "decolonised, modern, healthy, happy, functional democracy, fair and prosperous society that prides itself on integrity and inclusivity".122 Its political ideology is humanism -more particularly, African humanism.123

The key environmental problems recognised by this Party include the lack of clean and potable drinking water, the removal of domestic refuse and the prevention of soil, water, air and noise pollution.124 Public health care is the object of the Party's focus, however.125 It may be assumed that health, as seen by the Party, includes environmental health. 126 This inference is drawn from the issues that the Party deems as affecting human health, including the inability of many communities to access quality drinking water, and the shortage of health inspectors to check that food is produced, stored, and distributed in a safe manner and that such food is safe and wholesome for human consumption. Preventing communicable diseases is also identified as an environmental health challenge in local government. It is impressive to see that ATM recognises the link between environmentally related functions where water, air and food quality would affect the physical health of communities. This suggests that the Party would not engage in silo management of environmental issues.

As of the last local government elections (2021), ATM is not governing a municipal council. As such, they do not have a record of what their Party has done to improve LEG. At most, the Party states its commitment to solving environmental issues without necessarily identifying specific tools or measures.127 For instance, the Party commits to prioritising and providing basic services to local communities as necessary for human health and well-being as envisaged in section 24 of the Constitution.128 The Party does not mention how it will achieve this.

4.4 Democratic Alliance

The DA was created in 2020.129 It was founded after the Democratic Party (DP) reached a merger agreement with the Federal Alliance and the New National Party (NNP).130 The DA is officially the national opposition party of the ANC.131The DA states in its constitution that it stands with all South Africans who "share a community of values embodied by these words: freedom, fairness, opportunities and diversity".132 This Party is currently governing several municipalities in South Africa, including the City of Cape Town, and is in charge of several coalition councils, including Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality. The DA is currently governing the Western Cape province.

In its 2021 manifesto the Party highlights environmental issues including water scarcity, wastewater and sewage, pollution and reliance on coal for energy.133The Party considers these issues as pertinent to environmental concerns in the local government sphere134 and it recognises that water is a scarce resource that is essential to life, health and economic development. It is the building block of human life and of every municipality.135 As such, the Party is of the view that the water crisis across municipalities reflects government failure.136The Party also recognises that the deteriorating state of municipal wastewater and sewage treatment management is one of the numerous pollution problems experienced in most parts of the Country and that it is a major contributor to environmental and human health problems.137 As such, the Party pledges amongst other things to provide access to reliable, clean, running water, safe to drink and to use in food preparation, and not to expose communities to raw sewage.138

As stated before, the DA has a history of governance in local government, and therefore identifies programmes that have been carried out in its municipalities over the years and proposes that these should be mainstreamed across all municipalities that it envisages governing. Some of programmes include working with residents, businesses and civil society to effectively deal with droughts in any municipality it is elected to govern.139

Educating communities on environmental conservation is also important for the DA. The Party's manifesto states that it wants to encourage communities to find solutions to reduce water consumption, such as waterless toilet systems or grey water flush systems.140 To reduce waste pollution the Party pledges to ensure sufficient rural waste collection points that ideally link to local buyback centres.141 An ideal solution is also believed to include innovations such as free drop-off facilities and the use of online waste recycling maps that connect residents and businesses with all types of buyback centres.142

The Party states that DA-led municipalities will purchase power from IPPs to minimise the effects of load shedding, as opposed to relying on Eskom. The Party supports businesses and people that sell their excess wind- and solar-generated electricity.143 The Party further urges national government to implement zero-rating value-added tax on LED lightbulbs and energy-efficient appliances144 - it is estimated that streetlights account for 30 to 60 per cent of total local government carbon emissions.145 The Party proposes that all streetlights operate using LED lighting, which will reduce carbon emissions because of the longer lifetime of such lights.146

With regard to what should be done by municipal councils to improve environmental governance, the Party proposes that whether the environment is governed through regulations, market-based mechanisms (including incentives) or taxes, each of these instruments should be subjected to a comprehensive regulatory impact assessment to determine the likely effect of the instrument on economic growth and employment levels.147

The instruments of the DA are impressive. They identify an environmental programme and thereafter propose a solution. The proposed solutions are not too ambitious given the fact that most of these have been implemented by the Party. Perhaps a point of critique is that the proposals made have been implemented in municipalities where there are more financial and human resources than in many other district and local municipalities. It might not be easy to implement these programmes in such other municipalities, given that they are often not as well-resourced as cities or metropolitan municipalities.

4.5 Economic Freedom Front

The EFF is a radical and militant economic emancipation movement formed in 2013.148 The Party was established by the former ANC youth league chairperson, Julius Malema, following his expulsion from the ANC. The EFF states on its website that its main aim is to bring together "revolutionary, militant activists, community-based organisations and lobby groups into a political party that is pursuing the struggle of economic emancipation".149

According to the EFF, most municipalities in South Africa do not deliver on the basics that underpin environmental governance which, the Party recognises, includes providing services such as clean drinkable water, and reliable electricity, sanitation and refuse services.150 The Party recognises that local government has a positive duty towards the environment that includes conserving the environment for the current and future generations.151

The instruments and history of the Party do not suggest that the Party has governed a municipal council. In its manifesto (2021) the Party states that it seeks to explore measures alternative from legislative ones to fulfil this duty.152It believes, for instance, that nature reserves must be used for environmental education purposes.153 Therefore, the Party states that it will nurture young people "that are aware of the ecological limits of the planet".154 Municipalities under the EFF would prioritise the maintenance of ecological infrastructure, and employ a team of people that will focus on eradicating alien plants, rehabilitating wetlands, and rehabilitating areas affected by soil erosion through the planting of ecologically suitable plant species.155

Other extra-legal measures proposed by the Party include creating municipal-owned nurseries.156 The Party wants to create municipal-owned nurseries that will grow indigenous plants in the hope that this will incentivise businesses that use clean energy, have clear water recycling methods and limit pollution levels.157 The Party also wants to establish a biodiversity conservation forum primarily comprised of civil society organisations.158 The functions of such a forum will include discussing the progress made with conserving natural resources and acting as an advisory forum to municipalities.159

The proposals of the Party are impressive, but they are rather remote from South Africa's reality. The Party should first detail its plans with regard to clean drinkable water, and reliable electricity, sanitation and refuse services and not merely ''acknowledge'' these as pertinent environmental governance issues affecting many South African municipalities.

4.6 GOOD Party

The GOOD Party was formed in 2018 by its founder and leader, Patricia DeLille (former Mayor of the City of Cape Town and current Minister of Tourism).160The Party states that its principles include zero tolerance for racism, gender, discrimination, corruption and poverty.161 The GOOD Party focusses on climate change as an environmental governance issue for local government.162According to the Party, cities are where climate change effects are felt most severely and where poor and vulnerable communities are disproportionally adversely affected.163

The Party believes that in governing the environment, municipal councils must uphold and implement international commitments to reduce emissions and the impact the country has on the planet.164 This includes reducing reliance on coal for energy and focussing on cheaper renewable sources of energy.165 The Party states that there is a need to devolve relevant functions from national to local government, such as electricity procurement and distribution, transport, rail and efficient urban planning.166 This would allow municipal councils to legislate on matters affecting their communities and implement sustainability programmes suitable for their communities.167

The Good Party is one of the few parties that expressly acknowledges that municipalities have a role to play in fulfilling international environmental obligations. This is not a surprise given that its leader has participated in city networks around the world including the C40 Cities organisation. As mayor of the City of Cape Town, De Lille pledged that the City would implement ambitious policies and innovative programmes that aimed for net zero carbon emissions from newly-built buildings by 2050.168 However, like the EFF, the Party should first detail its plans with regard to clean drinkable water, and reliable electricity, sanitation and refuse services, as these could be considered ''pressing'' issues in South African municipalities.

4.7 The Freedom Front Plus

The FF Plus was established shortly before April 1994 under the leadership of General Constand Viljoen.169 The Party participated in the first democratic elections, which were held in the same year.170 In its mission statement, the Party states that it is

irrevocably committed to the realisation of communities, in particular the Afrikaner's internationally recognised right to self-determination, territorial and otherwise, the maintenance, protection and development of their rights and interests as well as the promotion of the right to self-determination for any communities in South Africa bound by a common linguistic and cultural heritage.171

According to the Party, core problems in local government include the ongoing destruction of the environment.172 The Party argues that South Africa's natural resources and environment are being destroyed by an incompetent government with incorrect priorities.173 Landfills are illegal, sewage runs into rivers and the sea, and municipal by-laws meant to prevent pollution either do not exist or are not properly implemented.174

None of the instruments of the Party suggests that the FF Plus has adopted innovative ways to govern the environment. In its manifesto (2021) the Party states that the environment should be protected through effective policing in the case of pollution and the contravention of applicable laws.175 There is also a need to prioritise upgrading and to maintain sewage plants176 - infrastructure allocations must be used to upgrade existing infrastructure.177 Practical solutions must be investigated to prevent waste pollution in rivers, dams and the sea.178 Such solutions should include, for instance, affixing nets to stormwater drains to prevent plastic waste from entering water sources.179

According to the FF Plus, attention should also be given to the security of landfill sites and the enforcement of applicable legislation.180 Each municipality must encourage a culture of recycling and initiate projects which involve the unemployed in the orderly recycling of waste for the benefit of the community and the environment.181 The FF Plus also posits that municipalities should create a favourable environment for residents to switch to renewable energy.182

This should involve rebates on taxes for residents who switch to renewable energy sources, for example.183 The Party also encourages the private generation of electricity and calls for projects for affordable and sustainable alternative electricity.184 The legislative and executive powers and functions of municipal councils are generous to the extent that they allow municipalities to use innovative measures to govern the environment. The Party must balance between regulating the environment through bylaws and other innovative measures.

4.8 Inkatha Freedom Party

The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) was established on the 21st of March 1975 by its then leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi.185 The Party states that it exists to serve the people of South Africa and to do so in the spirit of Ubuntu.186 This makes Ubuntu a founding principle of the IFP.

It is common knowledge that the IFP governs several municipalities in KwaZulu-Natal, including uMhlathuze, Dannhauser, Mtubatuba and Amajuba local municipalities.187 The instruments of the IFP do not highlight the environmental governance stance of the Party other than the manifesto's (2021) committing it to provide clean water by investing in infrastructure and connecting households.188

4.9 United Democratic Movement

After being expelled from the ANC in November 1996, Bantu Holomisa launched the United Democratic Party (UDM) on the 27th of September 1997.189 In its vision statement the Party avers that the UDM is "a political home for all South Africans, united in the spirit of South Africanism".190 Therefore, South Africanism is an ideology that focusses on how the common passion and rich cultural diversity of South Africans can be used to create a country that all will be proud to live in.

The key environmental challenges prevalent in municipalities as seen by the UDM include access to water and sanitation, reliable access to electricity and regular refuse removal.191 These are issues, the Party states, in rural areas, townships, health care facilities and schools.192 The Party states in its manifesto that access to water and sanitation is even more important because it is a constitutional right of all citizens.

The Party makes a commitment to providing basic municipal services such as ensuring regular waste removal.193 It also states that it will enforce by-laws for the effective execution of the duties of local government.194 The Party adds in its manifesto that it will establish dedicated task teams which will clean and remove alien vegetation from vacant municipal sites, wetlands and streams, and that it will provide recycle centres for waste pickers to avoid the mushrooming of unregulated recycle sites.195 The UDM's instruments are significantly void of details on how the Party will achieve environmental governance.

5 Conclusion

While there is sufficient research on environmental governance and the scope of the accountability of global political and non-political actors therein, this article is the first to question the accountability of political parties concerning environmental governance in South Africa. The objective of this article was to investigate how political parties in the Country conceive of their accountability in the environmental governance context. Conducting an inquiry of this nature was possible only by reviewing a selection of the parties' constitutions, policies and manifestos. The inquiry could also not be divorced from IEP.

South African municipalities have sworn allegiance to international institutions that advocate sustainable environmental governance. This has ensured that IEP infuses South African cities, changing how local authorities do politics. The Constitution has allowed for the relationship between international institutions such as ICLEI and C40 Cities and local government authorities to persist. The Constitution has also altered the role of politics in the South African local government sphere - essentially allowing political parties to select from among their ranks councillors to govern municipalities.

The role of councils is complex. Councils owe allegiance to the international environmental community (in IEP), the Constitution and the relevant legislative and policy framework, as well as to their affiliated parties. Councillors are guided in the first instance by their parties' ideals, policies and strategies. It would be unfair to assume that without the policy backing of their political parties' councillors would be reluctant to advance or prioritise environmental concerns in their councils. However, where the constitutions, policies and manifestos of a political party promise ecologically sustainable development and the protection of the environment, this could serve as a meaningful driver of the councillor's commitment to ecologically sustainable development and environmental priority-setting in municipalities. There is also tension between adhering to party dictates and fulfilling promises to local communities. Councils are accountable to local communities. Accountability in local government is a constitutional mandate listed in the objects of local government and in the Code of Conduct for Councillors. Therefore, the task of municipal councils to maintain these relationships is complex but critical for effective environmental governance.

The courts in South Africa have said that municipal councils are accountable for environmental governance. The golden thread that runs through the courts' reasoning is too be found in sections 151(2) and 156(1), which state that municipal councils have executive and legislative authority over LEG matters listed in Schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution. It comes as no surprise therefore that several parties correctly state in their instruments that environmental governance is a constitutional mandate.

The selected party manifestos, constitutions and policies have revealed that political parties still have a narrow focus on environmental governance. Some of the parties acknowledge that local communities are adversely affected by the lack of municipal services, including water, sanitation, solid waste management and stormwater systems. However, the parties do not present a clear plan of action. This suggests that unless these political parties have a plan on how their councils will provide sustainable municipal services, local communities will continue to suffer the consequences of a degraded environment. Local communities also directly feel the effects of climate change, as in the case of the chronic droughts in Gqeberha and the floods in eThekwini and the surrounding areas. However, minimal mention is made in the manifestos of climate change and its effects on local communities. Perhaps political parties could be bolder in their pronouncements on environmental governance in their instruments?

It is apt to conclude that the development of environmental law and the trajectory of environmental governance in South Africa has been spearheaded by dedicated thinkers such as Prof Willemien du Plessis. Though not active in party politics she has been closely involved with the workings and training of government officials and decision-makers for many years. She has always had the interests of our country at heart and has so served as an example not only to academics and students, but also to those decision-makers in the local and other spheres of government who hold the integrity of our environment in their hands.

Bibliography

Literature

Alger J and Dauvergne P "Researching Global Environmental Politics: Trends, Gaps and Emerging Issues" in Alger J and Dauvergne P (eds) A Research Agenda for Global Environmental Politics (Edward Elger Cheltenham 2018) 114 [ Links ]

Andanova L and Mitchell R "The Rescaling of Global Environmental Politics" 2010 Annual Review of Environment Resources 255-282 [ Links ]

Aust H and Du Plessis A "Introduction: The Globalisation of Urban Governance - Legal Perspectives on Sustainable Development Goal 11" in Aust H and Du Plessis A (eds) The Globalisation of Urban Governance: Legal Perspectives on Sustainable Development Goal 11 (Routledge London 2019) 1-15 [ Links ]

Bos G, Düwell M and Van Steenbergen N "Introduction" in Düwell M, Bos G and Van Steenbergen N (eds) Towards the Ethics of a Green Future: The Theory and Practice of Human Rights for Future People (Routledge London 2018) 1-8 [ Links ]

Bouteligier S Cities, Networks, and Global Environmental Governance: Spaces of Innovation, Places of Leadership (Routledge New York 2013) [ Links ]

Carroll P et al "Environmental Attitudes, Beliefs about Social Justice and Intention to Vote Green: Lessons for the New Zealand Green Party?" 2009 Environmental Politics 257-278 [ Links ]

Cloete J Public Administration and Management (Van Schaik Cape Town 1998) [ Links ]

Curtis S "Cities and Global Governance: State Failure or a New Global Order?" 2016 Millenium 1-20 [ Links ]

Dalby S "Environement and International Politics: Linking Humanity and Nature" in Sosa-Nunez G and Atkins E (eds) Environment, Climate Change and International Relations (E-International Relations Publishing Bristol 2016) 42-59 [ Links ]

Dalton R "The Greening of the Globe? Cross National Levels of Environmental Group Membership" 2005 Environmental Politics 441-459 [ Links ]

De Solada A and Galceran-Vercher M "Introduction" in De Solada A and Galceran-Vercher M (eds) Cities in Global Governance: From Multilateralism to Multistakeholderism? (Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Barcelona 2021) 13-24 [ Links ]

De Visser J "Developmental Local Government in South Africa: Institutional Fault Lines" 2009 Commonwealth of Local Governance 7-25 [ Links ]

Du Plessis A "SDG 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient, and Sustainable" in Ebbesson J and Hey E (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of the Sustainable Development Goals and International Law (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2022) 281-303 [ Links ]

Du Plessis A and Kotzé L "The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and Environmental Rights Standards" in Turner S et al (eds) Environmental Rights: The Development of Standards (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2019) 93-115 [ Links ]

Dyer H "Green Theory" in McGlinchey S, Walters R and Scheinpflug C (eds) International Relations Theory (E-International Relations Publishing Bristol 2017) ch 11 [ Links ]

Eckersley R "Green Theory" in Dunne T, Kurki M and Smith S (eds) International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity (Oxford University Press Oxford 2013) 266-281 [ Links ]

Eleojo EF "Africans and African Humanism: What Prospects?" 2014 AIJCR 297-308 [ Links ]

Feris L and Fuo O "Environmental Rights Protected in the Constitution" in Du Plessis A (ed) Environmental Law and Local Government in South Africa 2nd ed (Juta Cape Town 2021) ch 6 [ Links ]

Fox S and Goodfellow T Cities and Development 2nd ed (Routledge London 2016) [ Links ]

Freedman W "The Legislative Authority of the Local Sphere of Government to Conserve and Protect the Environment: A Critical Analysis of Le Sueur v eThekwini Municipality [2013] ZAKZPHC 6 (30 January 2013)" 2014 PELJ 567612 [ Links ]

Fuo O Local Government's Role in the Pursuit of the Transformative Constitutional Mandate of Social Justice in South Africa (LLD-thesis NorthWest University 2014) [ Links ]

Hall J "Facing the Music through Environmental Administrative Penalties: Lessons to be Learned from the Implementation and Impact of Section 24G?" 2022 PELJ 2-35 [ Links ]

Harris P "Introduction: Delineating Global Environmental Politics" in Harris P (ed) Routledge Handbook of Global Environmental Politics 2nd ed (Routledge London 2022) 1-13 [ Links ]

Haufler V "Transnational Actors and Global Environmental Governance" in Delmas M and Young O (eds) Governance for the Environment: New Perspectives (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009) 119-143 [ Links ]

Heijden J et al "Special Section: Advancing the Role of Cities in Climate Governance - Promise, Limits, Politics" 2019 Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 365-373 [ Links ]

Karsten ASJ Local Government Accountability in South Africa: An Environmental Law Reading (PhD-thesis North-West University 2022) [ Links ]

Kemp D Global Environmental Issues: A Climatological Approach 2nd ed (Routledge London 1994) [ Links ]

Kidd M "The National Environmental Management Act and Public Participation" 1999 SAJELP 21-31 [ Links ]

Mathenjwa M "The Legal Status of Local Government in South Africa under the New Constitutional Dispensation" 2018 SAPL 1-14 [ Links ]

May A "Environmental Health and Municipal Public Health Services" in Du Plessis A (ed) Environmental Law and Local Government in South Africa 2nd ed (Juta Cape Town 2021) ch 7 [ Links ]

Napier C and Labuschagne P "Parliamentary Whips in the Modern Era: A Parliamentary Necessity or a Historical Relic?" 2017 Journal of Contemporary History 208-226 [ Links ]

Nhamo G and Agyepong A "Climate Change Adaptation and Local Government: Institutional Complexities Surrounding Cape Town's Day Zero" 2019 Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 1 -9 [ Links ]

Pereira J "Environmental Issues and International Relations, a New Global (Dis)Order: The Role of International Relations in Promoting a Concerted International System" 2015 Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 191 -209 [ Links ]

Pieterse M "Out of the Shadows: Towards a Line between Party and State in South African Local Government" 2020 SAJHR 131-153 [ Links ]

Shepherd N "Making Sense of 'Day-Zero': Slow Catastrophes, Anthropocene, Futures, and the Story of Cape Town's Water Crisis" 2019 Water 1-19 [ Links ]

Stevenson H Global Environmental Politics: Politics, Policy, and Practice (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2017) [ Links ]

Steyn P "Environmental Management in South Africa: Twenty Years of Governmental Response to the Global Challenge, 1972-1992" 2001 Historia 25-53 [ Links ]

United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN New York 2015) [ Links ]

Vogler J "Environmental Issues" in Owens P, Baylis J and Smith S (eds) The Globalisation of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations 8th ed (Oxford University Press Oxford 2020) 387-403 [ Links ]

Vogler J "Mainstream Theories: Realism, Rationalism and Revolutionism" in Harris P (ed) Routledge Handbook of Global Environmental Politics 2nd ed (Routledge London 2022) 30-41 [ Links ]

White JK "What is a Political Party?" in Katz RS and Crotty W (eds) Handbook of Party Politics (Sage London 2006) 5-15 [ Links ]

Case law

Beja v Premier of the Western Cape 2010 10 BCLR 1077 (WCC)

City of Cape Town v Robertson 2005 2 SA 323 (CC)

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality v Blue Moonlight Properties 2012 2 BCLR 150 (CC)

Featherbrooke Homeowners Association NPC v Mogale City Local Municipality (High Court: Gauteng Local Division, Johannesburg) (unreported) case number 11292/2020 of 25 January 2021

Fedsure Life Assurance Ltd v Greater Johannesburg Transitional Metropolitan Council 1998 12 BCLR 1458 (CC)

Fuel Retailers Association of Southern Africa v Director-General: Environmental Management, Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Environment, Mpumalanga Province 2007 10 BCLR 1059 (CC)

Kgetlengrivier Concerned Residents v Kgetlengrivier Local Municipality (CIV APP FB 04/22; UM69/2021; UM79/2021) [2023] ZANWHC 29 (17 March 2023)

Marius Nel v Hessequa Local Municipality (Western Cape Division of the High Court, Cape Town) (unreported) case number 12576/2013 of 14 December 2015

Maccsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town 2012 7 BCLR 690 (CC)

Mazibuko v City of Johannesburg 2010 3 BCLR 239 (CC)

Trustees for the time being of Groundwork Trust v Minister of Environmental Affairs (39724/2019) [2022] ZAGPPHC 208 (18 March 2022)

Legislation

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002

Land Use and Planning Ordinance 15 of 1985

Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act 56 of 2003

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998

Marine Living Resources Act 19 of 1998

Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act 28 of 2002

National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998

National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004

National Health Act 61 of 2003

National Water Act 36 of 1998

Spatial Planning Land Use Management Act 16 of 2016

Water Services Act 108 of 1997

Government publications

GN 423 in GG 18739 of 13 March 1998

GN 1093 in GG 43810 of 16 October 2020

Internet sources

ActionSA date unknown Climate Change and the Environment https://www.actionsa.org.za/climate-change/ accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

ActionSA 2021 Local Government Manifesto 2021 https://www.actionsa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ActionSA-LGE-Manifesto-2021.pdf accessed 6 May 2022 [ Links ]

ActionSA 2023 About ActionSA https://www.actionsa.org.za/about/ accessed 25 January 2023 [ Links ]

African National Congress 2017 ANC Constitution as Amended and Adopted at the 54th National Conference, Nasrec, Johannesburg 2017 https://www.anc1912.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ANC-Constitution-2017.pdf accessed 2 February 2023 [ Links ]

African National Congress 2021 Manifesto 2021 https://bit.ly/3P99JBp accessed 2 May 2022 [ Links ]

African National Congress 2023 About https://www.anc1912.org.za/our-history/ accessed 25 January 2023 [ Links ]

African Transformation Movement 2019 ATM Manifesto: 2019 National and Provincial Elections https://socialsurveys.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ATM_Manifesto_booklet.pdf accessed 25 January 2023 [ Links ]

African Transformation Movement 2021 2021 Local Government Elections Manifesto https://bit.ly/3uLNcCO accessed 2 May 2022 [ Links ]

Cilliers Z and Euston-Brown M 2018 Aiming for Zero-Carbon New Buildings in South African Metros https://www.sustainable.org.za/uploads/files/file145.pdf accessed 16 October 2023 [ Links ]

Democratic Alliance 2013 The DA Policy on Natural Resources: Environmental Affairs, Fisheries, Water Management and Mineral Resources https://cdn.da.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/14234226/Natural-Resources1.pdf accessed 13 October 2021 [ Links ]

Democratic Alliance 2019 History https://www.da.org.za/why-the-da/history accessed 25 January 2023 [ Links ]

Democratic Alliance 2020 Democratic Alliance Federal Constitution https://cdn.da.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/09091807/DA-Constitution-As-Adopted-on-31-October-2020-final.pdf accessed 3 February 2023 [ Links ]

Democratic Alliance 2021 2021 Local Government Elections Manifesto https://bit.ly/3P5Z36x accessed 6 May 2022 [ Links ]

De Vos 2018 Party and State: Conflating the Two Undermines Democracy https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2018-01-31-party-and-state-conflating-the-two-undermines-democracy/ accessed 16 October 2023 [ Links ]

Economic Freedom Fighters 2021 2021 Elections Manifesto https://effonline.org/2021-lgemanifesto/ accessed 6 May 2022 [ Links ]

Economic Freedom Fighters 2022 Home https://effonline.org/home/home-main2/main-home/ accessed 25 January 2023 [ Links ]

Freedom Front Plus 2020 Background https://www.vfplus.org.za/background accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

Freedom Front Plus 2020 Mission https://www.vfplus.org.za/mission accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

Freedom Front Plus 2021 Municipal Elections Manifesto 2021 https://www.vfplus.org.za/File/Download/17018/a95cb569-6b50-40c2-b488-775da5dca823 accessed 6 May 2022 [ Links ]

GOOD 2023 Home https://forgood.org.za accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

GOOD 2023 Environmental Justice for South https://forgood.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Climate.pdf accessed 3 November 2023 [ Links ]

GroundUp Editors 2018 Day Zero and Cape Town's Cacophony of Chaos: Mmusi Maimane's Approach to the Water Crisis is Wrong https://www.groundup.org.za/article/cape-town-leaderships-cacophony-chaos/ accessed 16 October 2023 [ Links ]

Harper P 2023 IFP/EFF Coalition Collapse will Cost Inkatha "One or Two" Councils, Says Hlabisa https://mg.co.za/politics/2023-01-30-ifp-eff-coalition-collapse-will-cost-inkatha-one-or-two-councils-says-hlabisa/ accessed 16 October 2023 [ Links ]

Inkatha Freedom Party 2021 Local Government Manifesto 2021 https://bit.ly/3okvG4Z accessed 6 May 2022 [ Links ]

Inkatha Freedom Party 2023 Our History https://www.ifp.org.za/our-history/ accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

Inkatha Freedom Party 2023 Why IFP? https://www.ifp.org.za/why-ifp/ accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

National Government of South Africa date unknown Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd https://bit.ly/3IHn6YY accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

Pieterse M 2018 Cape Town Water Crisis: Crossing State and Party Lines isn't the Answer https://theconversation.com/cape-town-water-crisis-crossing-state-and-party-lines-isnt-the-answer-90861 accessed 27 January 2023 [ Links ]

Sasol 2022 Sasol https://www.sasol.com/who-we-are/about-us accessed 16 October 2023 [ Links ]

United Democratic Movement 2017 Vision and Mission: UDM https://udm.org.za/vision-mission/ accessed 26 January 2023 [ Links ]

United Democratic Movement 2021 2021 Local Government Election Manifesto https://bit.ly/3yBzrYs accessed 6 May 2022 [ Links ]

United Nations Environment Programme 1973 Report of the Governing Council https://rb.gy/q8rx99 accessed 3 November 2023 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations