Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versão On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.26 no.1 Potchefstroom 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2023/v26i0a16378

SPECIAL EDITION: ENVIRONMENTAL & ENERGY LAW

The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Investment Climate

M Faure

Maastricht University and Erasmus, School of Law, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Email: faure@law.eur.nl

ABSTRACT

In this contribution to honour Willemien du Plessis we use the economic approach to law to explain how environmental law affects economic development and vice-versa. The contribution starts by presenting the Environmental Kuznets Curve that makes clear that environmental regulation should not retard economic development but that, on the contrary, environmental protection and economic growth can go hand-in-hand, provided there is environmental regulation. The contribution further discusses the idea of competition between legal orders and how this affects environmental law, and to this end both the race-to-the-bottom as well as the race-to-the-top are discussed. Finally, attention is paid to the role of environmental law in economic development.

Keywords: Environmental regulation; investment; World Bank; federalism; competition; environmental quality; centralisation; race-to-the-bottom; race-to-the-top.

1 Introduction

I have had the great honour and privilege to work with Willem ien on a book which we edited containing contributions from many African authors on fundamental questions regarding the balancing of interests in environmental law in Africa. A central question in that joint publication was how the interests of economic development and the need to provide environmental protection could be balanced in an appropriate manner. It is a question which is crucial to environmental law and one to which Willemien has paid a lot of attention, for example also with respect to mining law in South-Africa1and with respect to cooperative governance.2 It is also this complicated balancing exercise that will be the central issue in this contribution in honour of Willemien. I should like to focus particularly on the relationship between environmental law, environmental quality and the investment climate. It is a very difficult relationship because on the one hand there is a stream of literature arguing that there is a competition between legal orders, which is where this topic resorts economically. This corresponds to the idea that there would be a competition between states in order to attract business. Economists, as will be explained below, consider this competition between states and between legal orders as potentially beneficial. Just as economists see the effects of competition as being beneficial (generally leading to higher quality and lower prices), so the assumption with regard to the legal system is that competition might reduce costs and increase the quality of legal rules.

On the other hand, as will also be discussed below, some fear that this competition could also create competition to attract industry, which may eventually result in lower levels of environmental quality. This leads to the question of precisely what states are doing in practice: beneficially competing with one another to provide a higher quality of regulation to the citizens, or lowering levels of (environmental) standards to attract industry? The fear is indeed that the competition in legal orders could turn into a situation in which states would wish to attract business investments and in doing so would lower the levels of environmental standards. The assumption underlying this fear is that generally environmental regulation increases the cost of doing business. It assumes, in other words, that environmental regulation (such as the obligation to obtain an environmental permit) creates additional expenses. The same would be the case with other environmental obligations, such as a duty to pay environmental taxes or charges. From that perspective, and thus only at first glance, environmental law would endanger the investment climate as it would be bad for business. That would imply that, if a country really would like to attract industry, it should simply have a poor environmental legal framework. Intellectually this problem has been described as the race to the bottom. It implies that the seemingly beneficial competition between legal orders could transform into a negative situation where jurisdictions compete with one another to achieve ever lower environmental quality. This race to the bottom is sometimes also connected to the notion of the pollution haven hypothesis. This idea works as follows: assume that one country would like to attract industry and would subsequently lower environmental standards in order to attract industry; a neighbouring country might observe that, might wish to compete, and might consequently lower its environmental standards even further. That could (theoretically) give rise to a negative spiral whereby countries would compete for industry by offering ever lower environmental standards. The pollution haven hypothesis postulates that industry would relocate to "pollution havens" where their investments would not be hindered by environmental regulation. In other words, the pollution haven hypothesis points to the danger that the competition between legal orders is no longer positive but destructive, amounting to environmental regulation below acceptable levels of efficiency.

Of course, the race to the bottom is largely a theoretical construct which is minimally supported by empirical evidence. The relevant question is therefore to what extent competition between legal orders could in practice turn into a race to the bottom. Empirically this raises two questions. The first one is whether states indeed engage in a competition with lower standards to attract industry? And the second one is whether industry would also react, in other words, would it relocate merely because of the lower environmental standards? After all, the investment decisions of industry are dependent not only upon the level of environmental regulation. As will be indicated later in this essay, environmental regulation constitutes in fact only a small proportion of the total investment. That means that even if a state would like to offer lenient environmental standards in order to attract industry, it is not certain that that would be successful as a policy to create an attractive investment climate. Another empirical difficulty is that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between a healthy regulatory competition between legal orders to increase the quality of a regulation on the one hand, and on the other the competition to attract industry with inefficiently low standards; in other words, the race to the bottom. In practice there can be grey areas and often there is just a thin line between those two hypotheses.

In other words, it becomes evident from this brief general sketch that there are two slightly competing visions concerning the relationship between environmental law and the investment climate. The positive vision is that states will compete to provide a high quality of environmental regulation to their citizens; the negative view fears a downward spiral, a potential race to the bottom, and the creation of pollution havens. The issue has also received a lot of attention from the World Bank, as it has analysed (mostly through its so-called "Doing Business" reports) which conditions are favourable for industry to make investments. Again, some may argue that a favourable investment climate requires a lenient environmental policy. However, as will also be explained in this essay, the answer is in fact more balanced. Industry does not necessarily require a lenient environmental law framework, but rather legal certainty, so that industry can make the corresponding investments. There is, in addition, a different hypothesis, also to be discussed below, that it may be attractive to some extent for industry to have co conform with stringent environmental regulation. As is often the case in economics, the answer to these complicated economic issues is not black or white. How industry will react to environmental regulation will depend to a large extent on a variety of different factors and elements. In this essay I should like to sketch the different types of literature that have shed some light on this issue. First of all there is an area of literature dealing generally with the relationship between environmental protection and economic growth, also referred to as the Environmental Kuznets literature (2). Next, I will discuss the concept of the competition between legal orders (3) and the question of whether there will be a race to the top (4). I will then briefly sketch the work of the World Bank on this topic (5) and discuss the role of environmental law (6). Section 7 concludes the essay.

2 Environmental Kuznets Curve

2.1 What is the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC)?

The Environmental Kuznets Curve is named after the Nobel prize winner Simon Kuznets, who wrote on the relationship between income inequality and income levels in a country.3

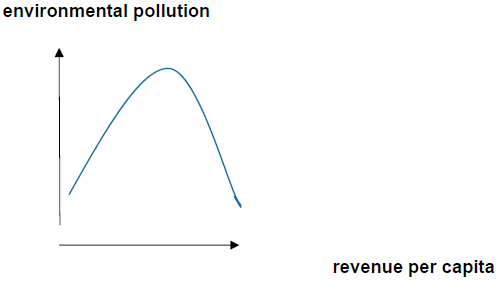

Since the 1980s scholars have applied this concept to environmental pollution, examining the empirical relationship between measures of environmental quality and national income.4 This literature shows an inverted u-shaped relationship, meaning that in the first phase of economic development (at low income levels) increasing economic development leads to increasing environmental degradation. However, there is a certain turning point (the top of the inverted u-curve) where income levels increase to such a point that a demand for higher environmental quality emerges, and so where increased economic welfare leads to increased environmental improvements. In the second phase an increase in income levels therefore leads to improved environmental quality. This is shown in the following curve:

This work has become known especially through the World Bank, which referred to it in its World Development Report 1992. The normative lesson that was drawn from this literature was that developing countries would have an interest in fighting poverty and increasing income levels, since this would also lead to higher levels of environmental quality. This vision has been strongly voiced by Beckerman, who was involved in drafting the 1992 World Development Report of the World Bank.5 Beckerman holds that "it is fairly clear that the best way to improve the environment of the vast mass of the world's population is to enable them to maintain economic growth" and "the strong correlation between incomes and the extent to which environmental protection measures are adopted demonstrates that, in the longer run, the surest way to improve your environment is to become rich".6

The policy conclusion drawn from this literature was therefore that pollution levels would automatically go down with the development of economic growth. That is, as will be illustrated below, a jejune conclusion. But let us first focus on what the potential explanations for this EKC could be.

2.2 Explanations

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) is surprising at first glance since the dominant view may be that more economic development (industrialisation) will automatically lead to more environmental pollution. The EKC shows that environmental damage may occur or increase in the beginning of industrialisation and economic development, but that there is a point beyond which environmental pollution peaks and later increasing levels of income would lead to decreased levels of pollution and corresponding higher levels of environmental quality. There is empirical evidence in support of the EKC, but the difficulty is of course to identify the precise causality behind the relationship. Simply stating that increasing income levels eventually leads to less pollution is too simple. Strand presents five theoretical reasons why the EKC may work; why higher income levels in a country could lead to lower pollution levels:7

1. When incomes grow, there may be a tendency for a larger share of total demand to consist of services rather than manufactured goods. This could explain why environmental and resource burdens decrease as incomes grow.

2. Technological progress generally leads to greater efficiency in the use of energy and materials. This idea is also strongly related to the work of Michael Porter, holding that environmental improvement does not necessarily come at the expense of competitiveness. Porter showed that, on the contrary, increased environmental performance will also lead to an increased competitiveness of nations and industries.8 This is known as the "Porter hypothesis", showing that not only countries but also companies may benefit from investment in environmental protection since this could increase their competitiveness.

3. The increase of income could also lead to changing preferences in the population. Once their basic needs are satisfied the population may value a clean environment, especially since it will want to enjoy its free time and recreation in a clean environment. In the words of Arrow et al, "People spend proportionally more on environmental quality as their income raises."9

4. With increasing economic development an educated population may demand democratic reform, and democratic societies tend to be more environmentally friendly.

5. Given the different levels of income among countries, increasing income may lead to moving the burden of production to lower income countries. This environmental dumping to pollution havens may reduce pollution levels in the rich countries which are able to relocate polluting activities to lower income countries.

2.3 Policy consequences

Some argue that this EKC literature, indicating that after a turning point increasing income levels lead to higher environmental quality, gives at least some room for optimism in the sense that economic development is apparently accompanied by such technological progress that environmental degradation, at least for traditional environmental quality variables such as air and water quality, can be successfully reduced.10

However, looking at the EKC literature in this simple way, one could be tempted to reach the (simplistic and therefore wrong) conclusion that the best way for a nation to promote environmental protection would be to promote economic growth.11 Empirical evidence after all shows that higher income levels go hand in hand with increased environmental protection.12In the words of Dasgupta et al, "In developing countries, some policymakers have interpreted such results as conveying a message about priorities: grow first, then clean up."13 Given those assumptions, one might reasonably conclude that regulatory instruments like environmental law could influence environmental quality only to a limited extent since this quality would be dependent upon other factors to a large extent, more particularly economic development and per capita income levels.

However, more refined empirical studies have shown that this conclusion would be too unbalanced, as environmental law itself plays a complex role in the EKC. Panayotou has shown that as far as the case of ambient SO2 levels is concerned, policies and institutions can significantly reduce environmental degradation at low income levels and speed up improvements at higher income levels.14 Cole et al have also shown that "developed countries have 'grown out of' some pollution problems" but "this is by no means an automatic process. Pollution levels have fallen only in response to investment and policy initiatives".15 Also Arrow and his coauthors conclude that "economic liberalisation and other policies that promote gross national product growth are not substitutes for environmental policy". Indeed "economic growth is not a panacea for environmental quality",16 since "in most cases where emissions have declined with rising income, the reductions have been due to local institutional reforms such as environmental legislation and market-based incentives to reduce environmental impacts".17 Dasgupta et al also show that the primary reason to make the EKC lower and flatter (and hence to reach the turning point towards decreasing pollution with rising income levels more quickly) is related to the primary role of environmental regulation. Richer countries have the capacity to regulate pollution more strictly, which is an important explanation of the EKC.18

Dan Esty and Michael Porter asked to what extent a nation's regulatory regime could influence environmental quality beyond the effects of income levels as suggested by the EKC literature. The result of this powerful research, based on an examination of regulatory intensity and environmental quality in a great number of developed and developing countries, is that economic development and environmental protection go hand in hand with the improvement of a country's institutions and more particularly its environmental regulatory regime.19 They find that not only do the rigour and structure of environmental regulations have a particular impact on environmental performance, but also on the enforcement. The empirical evidence suggests that a country can benefit environmentally not only from economic growth, but also from developing the rule of law and strengthening its governance structures.20

Interestingly, Esty and Porter also found evidence that countries that adopted a stringent environmental regime relative to their income were able to speed up economic growth rather than to retard it.21

2.4 Importance

The policy results of this EKC literature are therefore quite important. The literature shows first of all that economic growth provides several mechanisms that enable superior environmental outcomes. Second, the literature also shows that enhanced environmental rules and the development of stringent environmental standards can act to accelerate both economic and environmental benefits. These studies also provide strong support for increasing effective regulatory capabilities in developing countries. This literature has important consequences for China as well. It shows that a country like China should not be afraid of regulating industry in an intensive way if that would be the particular demand of the public. The EKC literature, and more particularly the empirical evidence provided by Esty and Porter, shows that stringent environmental regulation can go hand-in-hand with increased income levels and improved environmental quality. Investments in environmental regulation and a better environmental governance should therefore not endanger economic growth, but may stimulate economic growth as well as environmental quality.

3 Competition between legal orders

Another type of literature very relevant for the relationship between environmental regulation and the investment climate is the idea of competition between legal orders. This has already been referred to in the introduction.

3.1 Tiebout's model of federalism

In 1956 Tiebout developed a seminal theory on the optimal provision of local public goods.22 Tiebout imagined a scenario wherein local governments within a common federal nation competed as if they were firms creating public goods.23 His model enabled a solution to the "free-rider" problem in providing public goods by observing that communities compete in the provision of public goods and that residents could respond by "voting with their feet" to create better alignment of the goods provided with taxpayer willingness to support the provision of those goods. The seven conditions of the theory are:24

(i) that local voters can readily relocate to other communities in the same federal nation,

(ii) that each local voter has full awareness of the circumstances and options in each jurisdiction,

(iii) that there are sufficiently many communities from which to select a community,

(iv) that local voters face no employment consequences of relocating,

(v) that the public services of each community create no externalities or other diseconomies for the other communities,

(vi) that like private firms each producer of public goods faces an optimal number of residents in the community at which point the preferred public goods could be produced at the lowest average cost, and

(vii) communities with populations smaller than the optimal size of population per the previous assumption will make efforts to attract new residents to better attain those lower average costs of public good production.

Tiebout argued that when all those conditions hold true25 voters will react to their knowledge of options in different communities to choose their most preferred community, respectively per each voter, leading to overall allocative efficiency across the federal nation.

For example, if in one community the majority of the citizens have a high preference for sporting facilities and in another community a majority of the citizens have a preference for opera, the first community will probably construct sporting facilities whereas the second will probably provide an opera house. If someone living in the second community would prefer sporting facilities instead of the opera house, he could then move to the first community which apparently provides services which better suit his preferences. A well-informed citizen could move to the community that best matches the citizen's preference; i.e., the community that provides the local services sought by that citizen-on-the-move. Through this so-called "voting with the feet", competition between local authorities will lead citizens to cluster together according to their preferences.

In practice it is evident that different communities do indeed offer a variety of different services. Thus, a citizen can influence the provision of local public goods not only by participating in decision-making procedures, such as by voting, but also by choosing in which communities to engage in those decision-making procedures by relocating his//her abode to those communities.26

Further, the efforts put into communicating the information about the effectiveness of each community's approach to public goods would create deliberative information enabling all of the communities to evaluate their future policies and public goods.27

3.2 Competition between legal orders

This basic idea applies not only to community services, but also to fiscal decisions28 and environmental choices.29 In addition, this idea of citizens moving to the community that provides services which best correspond with their preferences could also be applied with respect to legal rules. A competition between legislators will lead to legal systems competing with one another to provide legislation that corresponds best to the preferences of citizens.30

The model holds that lawmakers in various nation-states will create competitive markets for the supply of law.31 Thereafter, citizens would cluster together in states that provide legal rules that correspond to their preferences. Well-informed citizens who may be dissatisfied with the legislation provided could move (voting with the feet) to the community that provides legislation that corresponds best to their preferences. This idea, assuming that different legal systems offer different legal rules, thus explains the variety and differences between the legal systems.32 This system, assuming that a competition between legal orders leads to allocative efficiency in the provision of legal rules, works only if certain conditions are met. One condition is that citizens have adequate information on the contents of the legal rules provided by the various legislators, in order to be able to make an informed choice. In addition, exit is often costly or legally prohibited, so people may stay even if the legal regime does not suit their needs optimally.33 A decision about location is made under the influence of a set of criteria in which the legal regime may not be decisive.34Usually job location and residence are so important that in reality there is often little left for people to choose.35

3.3 Criteria for centralisation

The Tiebout competition between legal orders works only on the condition that there are no transboundary externalities. If there are such transboundary externalities states may not have an incentive to impose stringent regulations upon their own citizens if the consequences of harmful actions are felt only outside their own territory. Transboundary externalities may thus create inefficiencies in the absence of central regulation.36 When a problem crosses the borders of the competence of an authority, that also becomes an argument to shift the decision-making power to a higher regulatory level, preferably to an authority which has jurisdiction over a territory large enough to deal with the problem adequately.37

This argument in favour of centralisation could play a role with respect to environmental problems. It could be argued that these are certainly often transboundary.38 In many regional organisations or federal states, one could therefore also notice that the transboundary character of a problem is often used as an argument for shifting decision-making powers to the central level. For example, much of the European legislation deals with transboundary problems and the same is the case in the United States of America (USA) as well, to a large extent.

There is a second argument for centralisation related to the already mentioned race to the bottom scenario, which envisions that governments could use lenient regulation as a competitive tool to attract industry.39

The validity of this race-to-the-bottom argument is strongly debated among law and economic scholars who tend to stress the benefits of competition between States and point out the dangers of centralisation.40 Others point at the potentially destructive effects of this interstate competition and hence attach more belief to the race-to-the-bottom rationale.41

Is there empirical evidence that industry will relocate as a result of lenient environmental law? North-American research has already shown that the effects of environmental regulation on the location decisions of industry are "either small, statistically insignificant or not robust to tests of model specification".42 Although more evidence somewhat relaxes these earlier findings it certainly does remain valid in the area of environmental law.43

As has already been mentioned in the introduction, the difficulty is that it is often not easy to distinguish beneficial competition between legal orders and a destructive race to the bottom. For example, there is competition between Chinese provinces. To some extent this competition may be beneficial when the provinces strive to offer better environmental regulation to their residents using mutual learning and best practices from other provinces. In other cases there may be a race to the bottom when provinces are attracting industry with inefficiently low levels of regulation, in which case they would de facto act as pollution havens.44 Whether there is a race to the bottom that would justify centralisation is therefore an empirical matter. And as has already just been indicated, the outcome of the empirical research in this domain is not crystal clear. One of the difficulties is that states may compete with one another by lowering their levels of environmental regulation in order to create a beneficial investment climate. But it is not always certain whether industry will respond (with relocation) to that competition. The problem is that environmental regulation often amounts to only a small percentage of the total costs of investment decisions. Other elements such as the quality of the workforce, the fiscal climate, the infrastructure and the availability of raw materials could be far more important in the investment decision of an industry.45 Moreover, differences in environmental regulation may play a role in a first decision concerning investment, but when an industry is already located in a particular area the marginal benefits of relocation need to be higher than the costs of relocation, and this may not always be the case.

4 Race to the top?

The competition between legal orders has just been presented as a race to the bottom. However, the competition will not always necessarily lead to a race to the bottom. There are some jurisdictions that act differently, not racing to the bottom at all. For example, it could be observed that there was in fact a relatively high level of environmental protection in Europe in the 1980s and several states were trying to achieve higher levels of environmental regulation. It was particularly those states that already had stringent environmental regulation, such as some of the Nordic countries (Sweden and Denmark) and the Netherlands and Germany that were trying to compete with other European Union (EU) Member States in terms of having the most stringent environmental regulation.46

One US state that has been known for racing to the top has been California. California has always tried to enact stricter emission standards than other states and its outcome has even been referred to as the California Effect. California has enacted strict environmental standards and has subsequently been followed by other states.47

This observation is interesting in the light of the previous discussion concerning the EKC. The story on the race to the top confirms that (as supposed in the EKC) states that actually have stringent environmental regulation also perform well economically, and have higher levels of gross domestic product (GDP). This is in fact related to a hypothesis developed by Michael Porter known in the literature as the Porter hypothesis.

4.1 The Porter hypothesis

The race-to-the-top argument fits into the Porter hypothesis, of course. In contrast to the traditional economic paradigm that environmental regulation imposes an additional cost on firms and may thus damage their competitiveness in the market,48 Porter basically argues in many publications that firms that move beyond environmental compliance will automatically not only make more investments in environmental protection but become more innovative generally.

The innovations needed to reach higher environmental standards would, according to Porter, also provide other benefits to the firm. In particular, Porter and Van de Linder believe that regulation can exert a substantial influence on firms' environmental innovation in at least six respects.49 This further innovation would provide strategic gains to the firm as a result of which those firms that strive for higher standards of environmental protection would also eventually be more profitable.50 Porter has defended this "Porter hypothesis" not only with respect to individual corporations, but also with respect to states. He holds that increased environmental performance will lead to increased competitiveness of both nations and industries.51

An overview of the literature shows that the empirical evidence broadly supports the Porter hypothesis. Ambec et al distinguish between a "weak" and a "strong" version of the Porter hypothesis. The weak version indicates only that properly designed environmental regulation may spur innovation.52The strong version implies a relationship between environmental regulation and the business performance of a firm.53 The authors conclude that the evidence for the weak version of the Porter hypothesis (that stricter environmental regulation leads to more innovation) is fairly clear and well-established.

When we look at the empirical evidence on the strong version of the Porter hypothesis (that stricter regulation enhances business performance) the record shows that while earlier studies found that environmental regulation has a direct negative effect on business performance,54 more studies have found clear empirical support for the strong form of the Porter hypothesis.55

4.2 Trading up: the California Effect

States engaged in a race-to-the-top aim at strengthening the international competitiveness of domestic firms. Some other (competing) states may mimic their strict regulatory standards because jurisdictions which have developed strict standards can force foreign producers to meet their domestic standards since market access may otherwise be denied.

The best evidence probably comes from California, which enacted stricter emission standards than the other states (thus the phenomenon is now referred to as the California Effect) and other states subsequently followed the California example.56 Many more examples of this "California Effect" exist, and this in fact leads to the opposite of a race-to-the-bottom, being the imposition of strict environmental standards which are subsequently "exported".57

"California Effects" can in some cases also be found in the transatlantic relationship. Basically, there have been situations in which regulatory trade measures by the (then) European Commission (EC) have led to a strengthening of domestic regulatory standards in the USA and Canada.58This once more shows that there is no straightforward answer to the question of whether jurisdictions engage in a race-for-the-bottom or rather a race-to-the-top, since the answer depends on particular facts and circumstances.

Looking at the case of the EU there also seems relatively little evidence that the traditional EU Member States were engaged in a race-to-the-bottom. Some high standard countries in Europe were rather involved in a race-to-the-top than in a race-to-the-bottom.59 The case of the Directive on Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control60 precisely proves that point: Northern European countries were strongly in favour of imposing strict emission standards (based on best available technologies) with which their industry presumably already could comply at the European level in order to create a "level playing field". Less developed Member States like Spain and Portugal were concerned over the potential costs to industry of having to use best available techniques as a result of the directive. The directive is now clearly to the advantage of industries in countries such as Germany, that already have strict facilities-specific emission limits. They prevailed at the European level, leading to a harmonisation of European emission limit values. De facto, this forced the foreign competitors in the South to follow the same strict regulation with which the industry in the North had already complied.61

This example shows that, as was indicated in the literature, a race-to-the-top can just as well lead to political policies overriding industrial and economic efficiencies.

4.3 Summary

This overview of the theoretical and empirical literature shows that the relationship between economic growth, industry behaviour and environmental quality is a complicated one. First of all, it is not always clear whether jurisdictions will be racing to the bottom or to the top. To a large extent that may depend upon the stringency of the environmental regulation in their own country and also on the level of economic development within the jurisdiction.

But it is important to recall that a race to the top (leading to higher environmental quality) is not more desirable under all circumstances (from an economic perspective) than a race to the bottom. After all, the race to the top could lead to the creation of barriers to market entry. Stringent environmental regulation could (sometimes inefficiently) create barriers to market entry. Domestic industry may try to impose its own domestic standards on foreign competitors. To the extent that they already have to comply with stringent environmental standards domestically, this does not lead to additional costs for them, but it may create serious barriers to market entry and thus restrict competition. It is also for that reason that one can sometimes observe coalitions between industry and green nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) in favour of stringent environmental regulation. Usually that could be described as a strategy on the part of industry to create barriers against market entry. It is for that reason that it is often difficult to judge the efficiency of particular strategies.

5 World Bank and LLSV

There are additional streams of literature which have also given attention to the relationship between economic growth and the quality of environmental regulation to an important extent.

5.1 World Bank

The first type of literature comes from a variety of studies from the World Bank concerning the relationship between law and the investment climate in a jurisdiction. The tenet of the reports of the World Bank is surprisingly simple: regulation (whether it concerns administrative regulation concerning the establishment of companies, labour law or financial regulation) always leads to additional costs for companies and will therefore have a negative effect on the investment climate. However, regulation which is favourable to corporate life, such as an adequate protection of property rights and more particularly intellectual property rights, will be considered as positive for the investment climate. There are many reports published by the World Bank, all having the objective of exhorting (especially developing) countries to create legal rules which are beneficial to business, as this would create a positive investment climate and therefore contribute to economic growth. For example, Klapper and co-authors show that regulation concerning the establishment of companies has a negative effect on the number of newly created companies.62 Regulation protecting intellectual property or supporting the financial sector would lead to an increase in research-oriented companies that have a need of external financing.63 The policy conclusion from these (and many other) studies from the World Bank for (developing) countries is that they have to reduce the regulatory duty for companies or at least should improve the quality of the regulation in order to attract the establishment of new companies and to promote economic growth.64 An amazing number of studies can be found on the website of the World Bank in which the World Bank tries to convince (developing) countries to create a favourable investment climate through regulation.

In addition the World Bank also publishes the so-called "Doing Business" reports. These reports provide an assessment (on the basis of a variety of criteria) of how difficult or easy it is for companies to locate themselves in a particular jurisdiction. The "Doing Business" reports address the many elements that affect the investment climate, some of which are related to law (such as how easy it is to obtain a building permit, the protection of minority shareholders and the enforcement of contracts), but many others relate to the wider business climate, such as the question of how complicated it is to obtain electricity in a particular country.65 In addition to examining the formal regulation, some studies also examine the costs and burdens with which companies are confronted when locating in a particular jurisdiction. This is especially done in the so-called "Enterprise Surveys", which are based on self-reporting by companies and therefore to some extent provide a biased impression concerning regulatory burdens.66

5.2 LLSV

In a different stream of literature strongly related to this work of the World Bank, there are the many publications of La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Schleifer and Vishny (summarised as LLSV) in which they examine the impact of legal rules on economic growth and more particularly on shareholder protection.67 LLSV generally concludes that the common law legal system provides a better protection to financial markets and more particularly to shareholders than the civil law. The most important reason for this is that common law judges have a better ability to stimulate the functioning of the market. In the civil law, judges would rather be bureaucrats forced to implement governmental policy. According to LLSV: "Common law stands for the strategy of social control that seeks to support private market outcomes, whereas civil law seeks to replace such outcomes with state-desired allocations."68 LLSV also claims that government property (for example in the financial sector, like the ownership of banks) is stronger in civil law countries than in the common law. As a result, in civil law countries (where LLSV mostly targets France) per capita economic growth and productivity would be lower than in common law countries.69Government intervention would be stronger in France than in common law countries, which generally would lead to a less effective government intervention.70

The LLSV studies have led to an amazing amount of criticism, both from lawyers as well as from economists.71 Economic heavy-weights like Acemoglu72 and Klick73 formulate serious criticism on the empirical support for the studies performed by LLSV. Klick even titled his contribution analysing the LLSV-methodology "Shleifer's failure".74 In addition, lawyers have seriously criticised the fact that particular legal rules and legal institutions were simply wrongly assessed75 and that legal historical research showing that in some civil law countries (more particularly Germany) creditor protection was systematically better than in the common law countries was simply ignored.76 Some conclude that "despite its tremendous influence in both academic and policy circles, the empirical estimates from the legal origins literature are simply not credible".77

6 The role of environmental law

What can now be said about the role of environmental regulation concerning the investment climate? It has been shown that theoretically jurisdictions could engage in a race to the bottom, trying to lure companies to a location with lenient environmental regulation. But the empirical evidence in that respect is not always crystal-clear and certainly not one-dimensional. The empirical evidence rather seems to indicate that the effect of environmental regulation on the investment climate is limited and statistically non-significant.78 There may be some effect of environmental regulation in the case of new companies seeking their first location, but differences in environmental regulation will usually not lead to a relocation of companies. Other factors, such as the tax level, infrastructure and the labour market have a far greater influence on the investment climate than the quality of environmental regulation.79 An empirical study concerning the decision of German companies to relocate outside of Germany shows that the following elements play a much more important role: lower labour costs, access to new markets, possibilities to penetrate other markets, lower costs and possibilities to expand the production capacity.80 Environmental standards do not seem to play much of a role.81

There is, however, empirical research from the US showing that the intensity of environmental regulation does have some influence. It shows that stricter regulation would lead to fewer locations of polluting industries.82 Research also shows that there is competition between individual states in the US concerning not only the intensity of environmental regulation but also concerning enforcement. A 10% increase in enforcement activity in a competing state led to a 5% to 16% increase in enforcement activities in another state.83 States do apparently react to enforcement efforts in other states, but this does not necessarily lead to a race to the bottom. Also, when competing states increase their enforcement activities, this leads to an increase in the own state as well.

That companies do react to changes in legislation, including environmental regulation, was shown when in 2004 ten Central- and East-European states joined the EU, thereby facilitating the mobility of capital from West to East. Many companies from the West used this possibility.84 The relocation to the East took place because of lower taxes and lower labour costs, but the intensity of environmental regulation also played an important role.85

7 Conclusion

In this contribution to honour Willemien du Plessis I have focussed on a topic which is undoubtedly of importance for many African countries, being the relationship between environmental regulation and the investment climate. One can certainly not argue that environmental regulation will always have an enormous influence on investment culture. The answer to a question about this is often: it depends. The starting point remains the literature of the Environmental Kuznets Curve, and this has important consequences, including at the policy level, for many countries. The lesson from the EKC is that states should not necessarily be afraid of stringent environmental regulation. Stringent regulation and a better institutional infrastructure will, as was shown by Esty and Porter, not only lead to higher environmental quality, but also to economic growth. Improved environmental quality and economic growth can therefore go hand-in-hand.

That is also the lesson from the Porter hypothesis. Porter shows (and his theory is supported by empirical evidence) that investments that companies have to make as a result of stringent environmental regulation lead to innovations that can increase their profitability. That is an important message both for companies as well as for states: compliance with stringent environmental regulation does not lead to the lower profitability of companies or reduced economic growth. Quite to the contrary. Moreover, some states may be racing to the top (like California or some of the Nordic countries). But it was also stressed that from an economic perspective a race to the top should be entered with caution, as it could lead to the creation of barriers to market entry, thus restricting competition and creating inefficiencies.

The most important policy conclusion from this literature (both theoretical and empirical) with respect to the relationship between an investment climate and an environmental policy is one that will hopefully please Willemien: there is no reason to be afraid of a stringent environmental policy. This message could be an important element in an information strategy of government officials directed towards industry. Compliance with environmental regulation, the move towards a green and circular economy, could go hand in hand with the increased profitability of companies and economic growth in states. It is a message that Willemien has also often spread in South-Africa and in the world. With her impressive work she has contributed in an important manner to the optimal mix between environmental protection and economic development. In other words, she has contributed greatly to the crucial notion of sustainable development.

Bibliography

Literature

Acemoglu D, Johnson S and Robinson JA "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation" 2001 Am Econ Rev 1369-1401 [ Links ]

Ambec S et al "The Porter Hypothesis at 20: Can Environmental Regulation Enhance Innovation and Comparativeness?" 2013 REEP 2-22 [ Links ]

Armour J et al "Law and Financial Development: What We are Learning from Time-Series Evidence" in Faure M and Smits J (eds) Does Law Matter? On Law and Economic Growth (Intersentia Antwerp 2011 ) 41 -98 [ Links ]

Arrow K et al "Economic Growth, Carrying Capacity and the Environment" 1995 Ecological Economics 91-95 [ Links ]

Ayres RU "Economic Growth: Politically Necessary but not Environmentally Friendly" 1995 Ecological Economics 97-99 [ Links ]

Beckerman W "Economic Growth and the Environment: Whose Growth? Whose Environment?" 1992 World Development 481-496 [ Links ]

Braun B "Locational Response of German Manufacturers to Environmental Standards" 1998 Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 253263 [ Links ]

Cole MA, Rayner AJ and Bates JM "The Environmental Kuznets Curve: An Empirical Analysis" 1997 Environment and Development Economics 401416 [ Links ]

Dasgupta S et al "Confronting the Environmental Kuznets Curve" 2002 Journal of Economic Perspectives 147-168 [ Links ]

De Bruyn SM "Explaining the Environmental Kuznets Curve: Structural Change and International Agreements in Reducing Sulphur Emissions" 1997 Environment and Development Economics 485-503 [ Links ]

Du Plessis W "Legal Mechanisms for Cooperative Governance in South Africa: Successes and Failures" 2008 SA Public Law 87-110 [ Links ]

Esty D "Revitalising Environmental Federalism" 1996 Mich L Rev 570-653 [ Links ]

Esty D and Geradin D "Environmental Protection and International Competitiveness. A Conceptual Framework" 1998 Journal of World Trade 5-46 [ Links ]

Esty DC and Porter ME "Industrial Ecology and Competitiveness: Strategic Implications for the Firm" 1998 Journal of Industrial Ecology 35-43 [ Links ]

Esty DC and Porter ME "National Environmental Performance: An Empirical Analysis of Policy Results and Determinants" 2005 Environment and Development Economics 391-434 [ Links ]

Esty DC and Porter ME "Ranking National Environmental Regulation and Performance: A Leading Indicator of Future Competitiveness" in Porter ME et al (eds) The Global Competitiveness Report 2001-2002 (Oxford University Press New York 2002) 78-100 [ Links ]

Faure MG "Optimal Specificity in Environmental Standard-Setting" in Dias Soares C et al (eds) Critical Issues in Environmental Taxation: International and Comparative Perspectives Vol III (Oxford University Press Oxford 2010) 730-745 [ Links ]

Faure M "Regulatory Competition vs Harmonisation in EU Environmental Law" in Esty DC and Geradin D (eds) Regulatory Competition and Economic Integration (Oxford University Press Oxford 2001) 263-286 [ Links ]

Faure MG and Johnston JS "The Law and Economics of Environmental Federalism: Europe and the United States Compared" 2009 Va Envtl LJ 205-274 [ Links ]

Frey B and Eichenberger R "To Harmonise or to Compete? That's not the Question" 1996 Journal of Public Economics 335-349 [ Links ]

Grossman GM and Krueger AB "Economic Growth and the Environment" 1995 Quarterly Journal of Economics 353-377 [ Links ]

Grossman GM and Krueger AB "Environmental Impacts of a North-American Free Trade Agreement" in Garber PM (ed) The US, Mexico Free Trade Agreement (MIT Press Cambridge 1993) 13-56 [ Links ]

Helland E and Klick J "Legal Origins and Empirical Credibility" in Faure M and Smits J (eds) Does Law Matter? On Law and Economic Growth (Intersentia Antwerp 2011 ) 99-113 [ Links ]

Hirschman AO Exit, Voice and Loyalty. Responses to Decline in Firms, Organisations and States (Harvard University Press Cambridge 1990) [ Links ]

Hotelling H "Stability in Competition" 1929 Economic Journal 41-57 [ Links ]

Inman R and Rubinfeld D "The EMU and Fiscal Policy in the New European Community: An Issue for Economic Federalism" 1994 Int'l Rev L Econ 147161 [ Links ]

Jaffe A et al "Environmental Regulation and the Competitiveness of US Manufacturing: What Does the Evidence Tell Us?" 1995 Journal of Economic Literature 132-163 [ Links ]

Kirchgässner G and Pommerehne W "Tax Harmonisation and Tax Competition in the European Community: Lessons from Switzerland" Unpublished paper presented at the Cost Meeting (November 1993 Luzern) [ Links ]

Klick J "Shleifer's Failure" 2013 Tex L Rev 899-909 [ Links ]

Kloppers H and Du Plessis W "Corporate Social Responsibility, Legislative Reforms and Mining in South-Africa" 2008 Journal of Energy and Natural Resources Law 91-119 [ Links ]

Konisky DM "Regulatory Competition and Environmental Enforcement: Is There a Race-to-the-bottom?" 2008 American Journal of Political Science 853-872 [ Links ]

Kuznets S "Economic Growth and Income Inequality" 1955 Am Econ Rev 1-28 [ Links ]

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F and Shleifer A "The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins" 2008 Journal of Economic Literature 285332 [ Links ]

La Porta R et al "The Quality of Government" 1999 Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 222-279 [ Links ]

La Porta R et al "Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation" 2002 Journal of Finance 1147-1170 [ Links ]

List JA, McHone W and Millimet DL "Effects of Air Quality Regulation on the Destination Choice of Relocating Plants" 2003 Oxford Economic Papers 657-678 [ Links ]

Livermore MA "The Perils of Experimentation" 2017 Yale LJ 636-708 [ Links ]

Millimet DL and List JA "The Case of the Missing Pollution Haven Hypothesis" 2004 Journal of Regulatory Economics 239-262 [ Links ]

Oates W Fiscal Federalism (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich New York 1972) [ Links ]

Oates W and Schwab R "Economic Competition among Jurisdictions: Efficiency Enhancing or Distortion Inducing?" 1988 Journal of Public Economics 333-354 [ Links ]

Ogus A "Competition between National Legal Systems. A Contribution to Economic Analysis to Comparative Law" 1999 ICLQ 405-418 [ Links ]

Partain R "The Legally Pluralistic Tourist" in Sonnenburg S and Wee D (eds) Touring Consumption. Management - Culture - Interpretation (Springer VS Wiesbaden 2015) 261-284 [ Links ]

Porter M "America's Green Strategy" 1991 Scientific American 168-179 [ Links ]

Porter ME and Van der Linde C "Towards a New Conception of the Environment - Competitiveness, Relationship" 1995 Journal of Economic Perspectives 97-118 [ Links ]

Princen SBM The California Effect in the Transatlantic Relationship (PhD-dissertation Utrecht University 2002) [ Links ]

Revesz R "Rehabilitating Interstate Competition: Rethinking the Race-for-the-Bottom Rationale for Federal Environmental Regulation" 1992 NYU L Rev 1210-1254 [ Links ]

Revesz R "Federalism and Interstate Environmental Externalities" 1996 U Pa L Rev 2341-2416 [ Links ]

Revesz R "Federalism and Environmental Regulation: An Overview" in Revesz R, Sands Ph and Stewart R (eds) Environmental Law: The Economy and Sustainable Development (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2000) 37-79 [ Links ]

Rojec M and Damijan J "Relocation via Foreign Direct Investment from Old to New EU Member States: Scale and Structural Dimension of the Process" 2008 Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 53-65 [ Links ]

Rose-Ackerman S Re-thinking the Progressive Agenda: The Reform of the American Regulatory State (The Free Press New York 1992) [ Links ]

Shen G Regulation of Cross-Border Establishment in China and the EU: A Comparative Law and Economics Approach (Intersentia Antwerp 2016) [ Links ]

Siems M "Measuring the Unmeasurable: How to Turn Law into Numbers" in Faure M and Smits J (eds) Does Law Matter? On Law and Economic Growth (Intersentia Antwerp 2011) 115-136 [ Links ]

Tiebout C "A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures" 1956 Journal of Political Economy 416-424 [ Links ]

Van den Bergh R "Subsidiarity as an Economic Demarcation Principle and the Emergence of European Private Law" 1998 MJECL 129-152 [ Links ]

Van den Bergh R, Faure MG and Lefevere J "The Subsidiarity Principle in European Environmental Law: An Economic Analysis" in Eide E and Van den Bergh R (eds) Law and Economics of the Environment (Juridisk Forlag Oslo 1996) 121-166 [ Links ]

Vogel D "Environmental Regulation and Economic Integration" in Esty DC and Geradin D (eds) Regulatory Competition and Economic Integration: Comparative Perspectives (Oxford University Press Oxford 2001) 337-347 [ Links ]

Xu G "The Role of Law in Economic Growth: A Literature Review" 2011 Journal of Economic Surveys 833-871 [ Links ]

Internet sources

Council Directive 76/464/EEC of 4 May 1976 on pollution caused by certain dangerous substances discharged into the aquatic environment of the Community, OJ L128 18.5.1976, p. 23-29, available on https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31976L0464 [ Links ]

Divanbeigi R and Ramalho R 2015 Business Regulations and Growth. Policy Research Working Paper No 7299 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22172 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Hallward-Driemeier M and Pritchett L 2011 How Business is Done and the 'Doing Business' Indicators: The Investment Climate when Firms have Climate Control. Policy Research Working Paper No WPS 5563 http://hdl.handle.net/10986/3330 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Klapper L and Delgado J "Entrepreneurship: New Data on Business Creation and How to Promote It. Note No 316 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11163 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Klapper L and Love I 2010 New Firm Creation. Viewpoint No 324 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11078 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Klapper L, Laeven L and Rajan R 2004 Business Environment and Firm Entry: Evidence from International Data, Policy Research. Working Paper No 3232 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14724 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Panayotou T 1995 Economic Instruments for Environmental Management in Developing Countries https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/28543 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Strand J 2002 Environmental Kuznets Curves: Empirical Relationships between Environmental Quality and Economic Development: Memorandum No 04/2002 https://www.sv.uio.no/econ/english/research/Memoranda/working-papers/pdf-files/2002/Memo-04-2002.pdf accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

Van Zeben J 2012 Regulatory Competence Allocation: The Missing Link in Theories of Federalism https://economix.fr/uploads/source/doc/seminaires/lien/Van-Zeben.pdf accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

World Bank Group 2016 Doing Business Regional Profile 2016: Landlocked Economies https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23862 accessed 11 June 2023 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

Am Econ Rev American Economic Review

EKC Environmental Kuznets Curve

EC European Community/European Commission

EU European Union

GDP Gross Domestic Product

ICLQ International and Comparative Law Quarterly

Int'l Rev L Econ International Review of Law and Economics

LLSV La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Schleifer and Vishny

MJECL Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law

Mich L Rev Michigan Law Review

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

NYU L Rev New York University Law Review

REEP Review of Environmental Economics and Policy

Tex L Rev Texas Law Review

U Pa L Rev University of Pennsylvania Law Review

USA United States of America

Va Envtl LJ Virginia Environmental Law Journal

Yale LJ Yale Law Journal

Date Submitted: 21 March 2023

Date Revised: 19 June 2023

Date Accepted: 19 June 2023

Date Published: 23 November 2023

Guest Editors: Prof L Kotze, Prof AA du Plessis

Journal Editor: Prof C Rautenbach

* Michael Faure, Professor of Comparative and International Environmental Law, Maastricht University and Professor of Comparative Private Law and Economics, Erasmus School of Law, Rotterdam, both in the Netherlands. Email: faure@law.eur.nl. ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8756-7832.

1 Kloppers and Du Plessis 2008 Journal of Energy and Natural Resources Law.

2 Du Plessis 2008 SA Public Law.

3 Kuznets 1955 Am Econ Rev. 1 - 28.

4 See especially Grossman and Krueger "Environmental Impacts of a North-American Free Trade Agreement", and Grossman and Krueger 1995 Quarterly Journal of Economics 13 - 56.

5 Beckerman 1992 World Development 481 - 496.

6 Beckerman 1992 World Development 491.

7 Strand 2002 https://www.sv.uio.no/econ/english/research/Memoranda/working-papers/pdf-files/2002/Memo-04-2002.pdf 6-8.

8 Porter and Van der Linde 1995 Journal of Economic Perspectives 97 - 118.

9 Arrow et al 1995 Ecological Economics 92.

10 Strand 2002 https://www.sv.uio.no/econ/english/research/Memoranda/working-papers/pdf-files/2002/Memo-04-2002.pdf 18.

11 This has been qualified by Ayres as "false and pernicious nonsense" (Ayres 1995 Ecologie Economics 99.

12 Also see Esty and Porter 1998 Journal of Industrial Ecology; Esty and Porter "Ranking National Environmental Regulation and Performance".

13 Dasgupta et al 2002 Journal of Economic Perspectives 147.

14 Panayotou 1995 https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/28543. Also see De Bruyn 1997 Environment and Development Economics, who argues that the existence of environmental policy fostered by international agreements explains why SO2 emissions curve downward at high income levels.

15 Cole, Rayner and Bates 1997 Environmental and Development Economics 412.

16 Arrow et al 1995 Ecological Economics 93.

17 Arrow et al 1995 Ecological Economics 92.

18 For the reasons see Dasgupta et al 2002 Journal of Economic Perspectives 152153.

19 See Esty and Porter 2005 Environment and Development Economics 424.

20 See Esty and Porter 2005 Environment and Development Economics 415.

21 See Esty and Porter 2005 Environment and Development Economics 424-425.

22 Tiebout 1956 Journal of Political Economy 416. For a discussion see Rose-Ackerman Re-thinking the Progressive Agenda 169-170.

23 Van Zeben 2012 https://economix.fr/uploads/source/doc/seminaires/lien/Van-Zeben.pdf 7.

24 Van Zeben 2012 https://economix.fr/uploads/source/doc/seminaires/lien/Van-Zeben.pdf 7, with reference to Tiebout 1956 Journal of Political Economy 419.

25 It is well recognised that the seven elements are restrictive in nature, but certain areas do functionally reflect these requirements; for example, certain areas in the USA, as well as other areas that might reflect partial satisfaction or no satisfaction with these requirements. We make no argument here that these are by any means commonly assumed conditions - merely that this model is very useful for analysing federal systems.

26 On the possibilities of citizens' taking action, see generally the well-known treatise of Hirschman on exit, voice and loyalty (Hirschman Exit, Voice and Loyalty).

27 Livermore 2017 Yale LJ 640.

28 See e.g. Inman and Rubinfeld 1994 Int'l Rev L Econ 147; Kirchgassner and Pommerehne "Tax Harmonisation"; and Oates Fiscal Federalism.

29 See Oates and Schwab 1988 Journal of Public Economics 333-354.

30 For a sociological perspective on the consumption of legal rules by individuals, see Partain "The Legally Pluralistic Tourist".

31 Ogus 1999 ICLQ 405-418.

32 Van den Bergh 1998 MJECL 134. Also, the Hotelling market model may be seen as antecedent to this result. See Hotelling 1929 Economic Journal.

33 As Ogus states, there should be no barriers to the freedom of establishment and to the movement of capital (Ogus 1999 ICLQ 407).

34 That is one of the reasons why Frey and Eichenberger argue in favour of Functionally Overlapping Competing Jurisdictions (FOCJ): the choice for one legal or institutional regime should not be exclusive; there may be "overlapping" jurisdictions depending upon the different functions (Frey and Eichenberger 1996 Journal of Public Economics 335-349).

35 Rose-Ackerman Re-thinking the Progressive Agenda 169.

36 Revesz "Federalism and Environmental Regulation" 67.

37 Esty 1996 Mich L Rev 603-605.

38 Also see Oates and Schwab 1998 Journal of Public Economics.333 -354. Who argue that as long as the effects of pollutants are confined within the borders of the relevant jurisdictions, local authorities will make socially optimal decisions of environmental quality.

39 See eg Rose-Ackerman Re-thinking the Progressive Agenda 166-170.

40 See especially Revesz 1992 NYU L Rev 1210 - 1254; Revesz 1996 U Pa. L Rev 2341 -2416.

41 See e.g. Esty 1996 Mich L Rev 570 - 653; Esty and Geradin 1998 Journal of World Trade 5 - 46.

42 Jaffe et al 1995 Journal of Economic Literature 157-158.

43 Faure and Johnston 2009 Va Envtl LJ 246-250. This literature is further discussed below in section 6.

44 On the competition between the provinces in China and the impact on investment decisions also see the dissertation by Shen Regulation of Cross-Border Establishment.

45 Jaffe et al 1995 Journal of Economic Literature 158.

46 See Faure and Johnston 2009 Va Envtl LJ 262-265.

47 Vogel "Environmental Regulation and Economic Integration" 336.

48 Jaffe et al 1995 Journal of Economic Literature 133.

49 Porter and Van der Linde summarised these six aspects in Porter and Van der Linde 1995 Journal of Economic Perspectives 99-100.

50 This has inter alia been defended in Porter and Van der Linde 1995 Journal of Economic Perspectives 97-118. For a summary see Faure and Johnston 2009 Va Envtl LJ 205-274.

51 See Porter 1991 Scientific American 168.

52 Ambec et al 2013 REEP 9.

53 Ambec et al 2013 REEP 9.

54 Ambec et al 2013 REEP 9.

55 Ambec et al 2013 REEP 16.

56 See Vogel "Environmental Regulation and Economic Integration" 336.

57 See Vogel "Environmental Regulation and Economic Integration" 336.

58 See on this issue extensively Princen The California Effect.

59 See Van den Bergh, Faure and Lefevere "The Subsidiarity Principle" 141-142; Faure "Regulatory Competition vs Harmonisation" 272.

60 Council Directive (EC) 76/464 OJ 1976 L 129/23.

61 See Faure "Optimal Specificity in Environmental Standard-Setting" 742-744.

62 Klapper, Laeven and Rajan 2004 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14724.

63 See Klapper and Delgado 2007 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11163; Klapper and Love 2010 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11078.

64 Also see in that respect inter alia Divanbeigi and Ramalho 2015 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22172.

65 See World Bank Group 2016 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23862.

66 See Hallward-Driemeier and Pritchett 2011 http://hdl.handle.net/10986/3330.

67 See an excellent summary of this literature in Xu 2011 Journal of Economic Surveys.

68 La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer 2008 Journal of Economic Literature 326327.

69 La Porta et al 2002 Journal of Finance 1147-1170.

70 La Porta et al 1999 Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 222-279.

71 An excellent summary of the criticisms is provided by Xu 2011 Journal of Economic Surveys 844-850.

72 Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson 2001 Am Econ Rev 1369-1401.

73 See Helland and Klick "Legal Origins and Empirical Credibility" 99-113.

74 See Klick 2013 Tex L Rev 899-909.

75 See Siems "Measuring the Unmeasurable" 115-136.

76 In that respect, see Armour et al "Law and Financial Development" 41-98.

77 Helland and Klick "Legal Origins and Empirical Credibility" 111.

78 See Jaffe et al 1995 Journal of Economic Literature 132-163.

79 Jaffe et al 1995 Journal of Economic Literature 132-163; Dasgupta et al 2002 Journal of Economic Perspectives 159-160.

80 Braun 1998 Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 253-263.

81 Also see in that respect Shen Regulation of Cross-Border Establishment 206.

82 List, McHone and Millimet 2003 Oxford Economic Papers 657-678; Millimet and List 2004 Journal of Regulatory Economics 239-262.

83 Konisky 2008 American Journal of Political Science 853-872.

84 See Rojec and Damijan 2008 Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 53-65.

85 Faure and Johnston 2009 Va Envtl LJ 205-274.