Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.25 no.1 Potchefstroom 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2022/v25i0a9472

ARTICLES

The African Union's Self-Financing-Mechanism: A Critical Analysis in terms of the World Trade Organisation's Rules and Regulations

University of the Western Cape South Africa. Email: goadams@uwc.ac.za; plenaghan@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to critically analyse from a theoretical perspective the compatibility of the African Union's (AU's) self-financing mechanism (SFM) with the rules and regulations of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) principle, which forms an integral part of the anti-discrimination provisions. The AU consists of 55 African countries, most of them members of the WTO. The SFM agreed is in the form of a 0.2 per cent levy applied to all eligible goods imported from a non-AU member state into the territory of an AU member state. As most of the AU member states (AUMSs) are WTO members, they must adhere to all the rules and regulations of the WTO. It is against this backdrop that this paper analyses the AU SFM against the relevant WTO rules and regulations. Most importantly this paper will provide recommendations for the compatibility of the AUs SFM in terms of the existing WTO rules and principles, such as the operation of the Differential and More Favourable Treatment, Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries, more commonly referred to as the Enabling Clause, given the WTOs general classification of all African countries as developing or least developed countries. The need for the AU to be self-sustainable financially in order for it to achieve its goals and objectives has most recently been reinforced.by the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic both locally and internationally.

Keywords: African Union; self-financing mechanism; anti-discrimination principle; most-favoured-nation principle; developing or least developed countries; free trade area; free trade agreements; preferential trade arrangements.

The lesson taught at this point by human experience is simply this, that the man who will get up will be helped up; and the man who will not get up will be allowed to stay down. This rule may appear somewhat harsh, but in its general application and operation it is wise, just and beneficent. I know of no other rule which can be substituted for it without bringing social chaos. Personal independence is a virtue and it is the soul out of which comes the sturdiest manhood. But there can be no independence without a large share of self-dependence, and this virtue cannot be bestowed. It must be developed from within.1

1 Introduction

A detailed historical account of the establishment of the African Union (AU) is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is imperative that the formation of the AU in conjunction with its objectives and principles is briefly introduced to put into perspective the importance of the AUs proposed self-financing-mechanism (SFM). The AU was officially established by the operation of Article 2 of the AU Constitutive Act (AUCA), which establishes the AU subject to the provisions of the AUCA.2 The AU was fundamentally formed with the vision to create an Africa that is:

An integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena.3

When the constituent parts of the vision are analysed, it is specifically stated that the prosperous and integrated Africa for which the AU strives should be driven by its own people. For any individual, organisation or country to be self-driven, the elements of independence and self-reliance are the key factors in determining how successful they will be. The correlation with the opening quotation is clear given the direct reference to the drive of its own people as stated in the AU's vision statement.

The reality of the matter is that the AU is significantly dependent on foreign funding, 76 per cent of the AU's budget funding stems from outside donors and partners such as the European Union, the United States, China, the World Bank and the United Kingdom.4 This reality is further worsened as the AU has been unable to collect the AU Member contributions as planned for the past few years as published in the 2018 AU budgeted funding analysis.5 Out of the 55 African Union Member States (AUMSs), about 30 default on payments on an annual basis, thus creating significant funding deficits.6 There are 6 countries, South Africa, Nigeria, Algeria, Angola, Egypt and Libya who contribute about 60 per cent of the membership portion of the AUs budget. As part of a study to support the development of a SFM it was established that about 90 per cent of the programme budget was donor funded and that AUMSs have paid on average only 67 per cent of their budgeted contributions.7 As a result the AU is in a compromised position of depending on donor funding, which has however consistently fallen below the requested amounts, and has been unable to execute its planned programmes. It is with this lack of sustainable and predictable funding in mind that the implementation of a World Trade Organisation (WTO) compatible SFM is imperative for the AU to achieve the principle of self-reliance.

Pursuant to the objective of finding a viable, equitable, sustainable and predictable source of financing for the AU, various alternative funding sources were identified and presented at the May 2013 AU Assembly.8 The concept of the SFM was approved but some AUMSs, especially those reliant on the tourism industry, raised concerns about the effect of the proposals on their already struggling tourism industries.9 In January 2016 Dr Kaberuka proposed the use of a 0.2 per cent import levy to be charged on all eligible goods imported into the African Continent to finance the AUs Operational, Programme and Peace Support Operations Budgets starting from the year 2017.10 The proposed 0.2 per cent import levy was accepted by the Assembly of the Union at the twenty-seventh AU Summit in Kigali as a viable option. The SFM is more commonly referred to as the Kigali decision.11 However, concerns were raised by some of the WTO Members regarding the WTO compatibility of the AUs SFM as most of the AUMSs are WTO Members and therefore need to adhere to all of the rules and regulations of the WTO.12 The COVID-19 pandemic forced all countries including those that provide donor funding to focus on stimulating their national economic activities through national monetary grants. The establishment of the AU COVID-19 Response Fund, following donor funding deficits, emphasises the need for the AU to be self-sustainable so that it can continue with its mandate, and it is therefore imperative that the AU finds a WTO-compatible SFM.13

To become WTO members the relevant AUMSs had to commit and agree to all the WTO rules and regulations governing international trade as prescribed in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1994) (GATT 1994). These rules and regulations need to be adhered to by all the WTO members. Contravening members run the risk of facing disputes initiated by other WTO members or by the WTO itself. Whilst the AU as an organisation is not a WTO member, of the 55 AUMSs the WTO membership status can be summarised as follows: 43 have full WTO membership status, 8 have observer WTO membership status14 and only 4 have no WTO affiliation,15which substantiates the extent to which the WTO rules and regulations would apply to the AU through the dual AU/WTO membership status.16

It has been argued that the SFM proposed by the AU in its current form might be inconsistent with the requirements as set out by the WTO.17 As WTO members, the affected AUMSs are obliged to adhere to the WTO rules and regulations. The GATT 1994 states in the relevant part that in the objective of furthering reciprocal and mutually beneficial agreements directed at substantially reducing the tariffs and other barriers to and eliminating discrimination in international trade, all of the members agree to follow the Articles to the GATT 1994.18 All AU/WTO member states are bound by all of the WTO rules and regulations, but the following are relevant with respect to the AUs SFM. The specific articles that the AUMSs might contravene by the 0.2 per cent import levy on eligible goods are Article I -General Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) Treatment, Article II - Schedules of Concessions, and any regional trade agreements (RTAs) entered into under Article XXIV of the GATT 1994.

Article 1 of the GATT 1994 essentially requires that all WTO members be afforded the same benefits to eliminate discrimination amongst WTO members. Therefore, if a lower rate is charged by a WTO member on goods imported from another WTO member, then that lower rate must be applicable to all the other WTO members as well. The Schedules of Concessions as per Article II of the GATT 1994 list all of the maximum tariff levels, also referred to as bound rates, that a WTO member can charge any other WTO member. All RTAs in terms of Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 between the relevant WTO members have the same effect of prescribing bound rates when those agreements were concluded. In both instances the SFM could result in an AU/WTO member adding an additional 0.2 per cent import levy cost onto eligible goods for which bound rates have already been agreed. The result would be a breach of existing agreements and could therefore render the SFM WTO incompatible.

The SFM is definitely a step in the direction of achieving the goals as set out by the AU in respect of self-reliance and economic growth.19 In its current form the SFM may not be WTO compatible, giving rise to the possibility of disputes being filed against AU/WTO members. However, the GATT 1994 provides for exceptions to the general rules that can be used by the AU as a means to defend the SFM and render it WTO-compatible. All the AUMSs are either developing or least developed countries in terms of the WTO classifications.20 These classifications of the AUMSs allow for certain exceptions to the WTO rules and regulations that will be discussed further in the body of the paper.

As previously indicated, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to be financially self-reliant and a SFM as envisioned by the AU that is WTO compatible will significantly assist the AU in achieving that objective. Of the 55 AUMSs, 25 AUMSs as of 20 December 2018 were at various stages of the SFM implementation. Of the 25 AUMSs, 16 AUMSs21 have implemented the SFM and except for 2 AUMSs22 the remaining 14 AUMSs fully or partially paid their 2018 contributions to the AU through the SFM. At this date a further 6 AUMSs23 were in the process of domesticating the Kigali Decision.24

Part 2 of this paper will focus on the AU and the details of the SFM, while Part 3 will highlight the WTO rules and regulations relevant to the AUs SFM and assess the WTO compatibility of the AUs SFM against the relevant rules and regulations. A preliminary conclusion will be provided, after which possible corrective action will be suggested that the AU could consider so that the SFM could be deemed WTO compatible. An overall summary regarding the WTO compatibility of the SFM and corrective action will be provided in Part 4.

2 The African Union and the self-financing mechanism

Before getting into the details of the AUs SFM, it is important that we gain an understanding of the objectives and principles of the AU. This will put into perspective the need for a SFM as approved by the Kigali Decision. As previously indicated, the AU was officially established by the operation of Article 2 of the AUCA. Articles 3 and 4 of the AUCA set out the objectives and principles respectively of the AU and as such provide the framework within which the AU can plan and act as an institution. The substance of Article 3 of the AUCA is geared to creating greater unity between the African countries, promoting the interest of the African Continent and promoting sustainable development in the African Continent at the economic, social and cultural levels. Article 4 of the AUCA, with specific reference to paragraph (k) of the article, explicitly promotes the notion of self-reliance within the AU framework, which cannot be achieved when donor funding constitutes about 76 per cent of the AUs budget, as it did at the time of developing the SFM.25 As with any organisation with planned objectives, the budgetary requirements have to be met so that the funds are available for the organisation to be effective; and the AU is no different.

The AU's budget consists of three major components: (1) the operational budget; (2) the programme budget (excluding peace support operations); and (3) the peace and security budget.26 Only the pertinent details for the purposes of this paper will be highlighted.27

An analysis of the overall member state contributions reveals the following:28

(a) The member states have collectively not paid 100 per cent of the contribution budgeted for by the AU in any of the years.

(b) On average only 67 per cent of the total member state contribution has been paid to the AU over the five-year period analysed.

(c) Of the arrear member state contributions outstanding, only 67 per cent were paid by the member states in arrears.

This leaves the AU in the compromising position of expecting about 90 per cent of the programme budget to be funded by donors. Donor funding has, however, consistently fallen below the requested amounts, which has left the AU unable to execute the programmes planned for. It is with this lack of sustainable and predictable funding in mind that we shift our attention to the relevant details of the AU's SFM.

2.1 The background and purpose of the Self-Financing Mechanism

The notion of self-reliance was core to the pan-African values leading to the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and has been carried forward to the principles of the AU as well.29 The initial conceptualisation of a SFM can be traced back to declaration 1 (XXXVII) by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government held in 2001, during which the determination to uplift the living conditions of Africans via the achievement of self-reliance was reiterated.30 The purpose of the SFM can be ascribed to the achievement of the following objectives:31

1. To provide reliable and predictable funding for Continental peace and security through the Peace Fund,

2. To provide an equitable and predictable source of financing for the union,

3. To reduce the dependency on partner funds for the implementation of Continental developmental and integration programmes and

4. To relieve the pressure on national treasuries with respect to meeting national obligations for payment of the assessed contributions of the Union.

An analysis of the above objectives highlights the financial requirements the shift from a policy of non-interference as per the OAU principles to non-indifference as per the AU principles is expected to have on the peace fund.32 Creating a reliable source of funding to cover the budgetary requirements of the AU is critical to reducing dependency on donor funding, especially for development programmes and a SFM to assist the members of the Union to fulfil their financial contribution requirements.

2.2 The form and relevant details of the self-financing mechanism

Pursuant to the objective of finding a viable, equitable, sustainable and predictable source of financing the AU, various alternative funding sources were identified33 and presented at the May 2013 AU Assembly.34 The principle of the SFM was in substance approved but the alternative funding sources raised concerns amongst the AUMSs reliant on an already struggling tourism industry as the hospitality and flight ticket levies could negatively affect those AUMSs.35 In January 2016 Kaberuka proposed the use of a 0.2 per cent import levy to be charged on all eligible goods imported into the continent to finance the AU's aforementioned budgets, starting from the year 2017.36 The 0.2 per cent proposed import levy was accepted by the Assembly of the Union at the twenty-seventh AU Summit.37

The SFM is technically described as a 0.2 per cent import levy to be charged on all eligible goods imported into the territory of an AUMS from a non-AUMS.38 An analysis of the statement used to describe the SFM identifies the following components as important:

(1) 0.2 per cent import levy;

(2) charged on all eligible goods; and

(3) imported into the territory of an AUMS from a non-AUMS.

The operation of the SFM could in theory result in the 0.2 per cent import levy being charged on import transactions involving eligible goods between WTO Members, where the seller is not an AUMS. However, should both the seller and the buyer be AU/WTO members, the 0.2 per cent import levy would not be charged and this deemed discriminatory action is the basis of the MFN principle. As WTO members the affected AUMSs39 have the responsibility to adhere to all the WTO rules and regulations as prescribed by the GATT 1994. The MFN principle of the GATT 1994 requires that all like products, irrespective of their origin, should be subject to the same bound rates as agreed in the schedule of concessions.

Article II of the GATT 1994 provides for this schedule of concessions that have been agreed to on a multilateral level by all the WTO Members. This inconsistency in the bases of the 0.2 per cent import levy has raised concerns as it contravenes Article I - General MFN Treatment, Article II -Schedules of Concessions, and any RTAs entered into under Article XXIV of the GATT 1994. It is with this deemed contravention of the non-discrimination principle that we continue to part 3 of the paper to address the relevant WTO rules and regulations applicable to the AUs SFM and the impact on the AUs SFM.

3 The applicable WTO rules and regulations and impact on the AUs SFM

The WTO rules and regulations consist of multilateral40 and bilateral or RTAs41 that are applicable to all affected WTO members.42 The multilateral trade system has benefits and consequences. The key benefit is that all the WTO members are treated equally, but WTO negotiations are complex and time consuming, a fact which has given rise to the proliferation of bilateral agreements and RTAs.43

Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 provides for exceptions to the MFN rule to facilitate economic integration, which fundamentally forms the basis for RTAs.44 Even though Article XXIV provides for exceptions to the MFN principle by allowing RTAs, the bound rates as per the multilateral trade agreements are carefully policed by the WTO and any agreements that contravene the RTAs bound rates are considered WTO-incompatible.

With specific reference to the functioning of the SFM the following relevant rules and principles have been isolated for the purpose of addressing the effect of the SFM from a WTO perspective: (1) the principles of non-discrimination; (2) the rules on conflicts between trade liberalisation and other societal values and interests; and (3) the rules on special treatment for developing countries.

The AUs SFM in its current form could be considered WTO incompatible from the perspectives of: (1) the MFN principle in terms of the multilateral agreement; and (2) existing RTAs that have been signed amongst WTO Members to facilitate economic integration in terms of Article XXIV of the GATT 1994. The AUs SFM will therefore be assessed against the applicable WTO rules and principles from both perspectives. We will then separately assess the SFM with reference to the rules on special treatment for developing countries as provided for by the WTO.

3.1 WTO compatibility of the AUs SFM from a MFN perspective

3.1.1 The principles of non-discrimination

The non-discrimination principles of the WTO as contained in the Articles of the GATT 1994 are arguably the most important principles upon which the multilateral trading system is built.45 The MFN obligation in terms of Article I and the national treatment (NT) obligation in terms of Article III of the GATT 1994 collectively form the anti-discrimination principles of the WTO, which are defined below.46

Article I: Most-Favoured-Nation treatment obligation

In terms of Article of the GATT 1994, the MFN treatment obligation requires in simplified terms that, when a WTO Member grants a more favourable47 advantage to another WTO Member, then that advantage should be granted immediately and unconditionally for all like products48imported from other WTO Members.

Article III: National treatment on internal taxation and regulation obligation

In summary, Article III(1)-(10), subject to very limited circumstances,49requires that all like products imported into the territory of a WTO Member should be afforded the same treatment as a locally produced like product. To this end, the imported like products cannot be directly or indirectly subjected to internal taxes or other charges, which the locally produced like product would not directly or indirectly be subjected to.

These two articles collectively, therefore, ensure that like goods are not discriminated against at the national border (MFN) and once inside the border, the like goods are not discriminated against within the border (NT). The SFM in principle only affects the goods at the border and not when they have entered the territory of an AU/WTO Member. Therefore, from a discrimination perspective, Article III of the GATT 1994 will not be discussed further in this paper.

3.1.1.1 Most-Favoured-Nation obligation

In terms of Article of the GATT 1994, WTO Members are not allowed to discriminate between WTO Members. To determine consistency with Article I(1), a four-tier test is applied as follows:50

(1) whether the measure at issue is a measure covered by Article I.1 which grants an advantage, favour, privilege or immunity, with respect to customs duties and charges of any kind;51

(2) whether the measure grants an advantage;52

(3) whether the products concerned are "like" products;53 and

(4) whether the advantage is accorded "immediately and unconditionally" to all like products concerned, irrespective of their origin or destination.54

An analysis of the four-tier test reveals quite clearly that like products, irrespective of the WTO Member's origin, should in principle be treated exactly the same by the purchasing WTO Member. Any WTO Member can challenge any other WTO Member if a breach in terms of Article of the GATT 1994 is suspected, which will be addressed in the section to follow.

3.1.1.2 Effect of MFN principle on the AUs SFM

Using the same numbering convention as previously, the SFM is assessed against the MFN principle as follows:

(1) whether the measure at issue is a measure covered by Article I(1);

The measure at issue is the 0.2 per cent import levy to be charged on all eligible goods imported from non-AU members, which could be eligible goods from non-AU/WTO members, into the territory of an AU/WTO member state. This is a charge imposed on imported eligible goods, which qualifies as a measure covered by Article

(2) whether the measure grants an advantage;

The AU/WTO member states will possibly be charging non-AUMSs who are WTO members a 0.2 per cent import levy on eligible products imported into the territory of a AU/WTO member state. The same charge will not be levied on eligible products imported from a AU/WTO member and therefore, an advantage through the lack of such a levy is granted amongst the AU/WTO member states.

(3) whether the products concerned are "like" products;

It is technically possible but highly unlikely that none of the products traded between the AUMSs will not qualify as a like product imported from other WTO member states not part of the AU. Therefore, in principle it is likely that eligible like products will be traded between the AUMSs and acquired from other WTO member states not part of the AU.

(4) whether the advantage at issue is granted "immediately and unconditionally" to all like products concerned.

By virtue of the self-financing mechanism, the advantage granted amongst the AUMSs will not be granted immediately and unconditionally to all eligible like products from other WTO member states not part of the AU. From the above assessment it appears that the AU's SFM is inconsistent with the MFN principle of the WTO. However, such an arrangement could be allowed if the provisions of Article XXIV dealing with RTAs are correctly applied. This leads us to the following perspective against which the SFM will be tested.

3.2 WTO compatibility of the AUs SFM from a RTA perspective

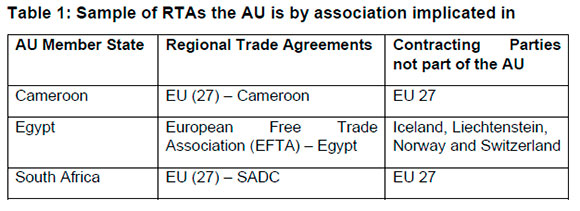

Under the rules on conflicts between trade liberalisation and other societal values and interests, the GATT 1994 provides for exceptions that allow WTO members to deviate from the MFN principle for the purpose of achieving trade liberation.55 There are numerous articles of the GATT 1994 which govern the application of these exceptions. However, Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 and the Understanding on the Interpretation of Article XXIV of the GATT 199456 dealing with regional integration exceptions will be addressed because of their relevance to this paper.57 Various AUMSs are party to numerous RTAs with WTO members outside of the AU. From the complete list of AUMSs, three AUMSs have been selected and table 1 below created to show the RTAs that the AU is implicated in and might possibly contravene.

From a RTA perspective, it needs to be determined only if the SFM will result in a breach of existing RTAs that the AUMSs have agreed to in their individual capacities with other WTO members not part of the AU. With this in mind, it is highly likely that in principle eligible like goods would have bound rates in terms of existing RTAs signed between AU/WTO members and WTO members to part of the AU. Some African countries could have agreed to a zero tariff and the implementation of the 0.2 per cent levy will put them in breach of those particular RTAs.58 In terms of the EFTA-Southern African Customs Union (SACU) Free Trade Agreement Article 8(1), no new customs duties should be introduced in trade between the EFTA States and SACU, which agreement would be contravened by the SFM. The SFM in its current form as tested from a MFN perspective potentially adds a 0.2 per cent additional charge to bound rates on goods agreed between WTO Members in terms of Articles XXIV of the GATT 1994 and therefore renders it WTO-incompatible from a RTA perspective.

Having performed the assessment of the SFM from the MFN (Article 1 ) and RTA (Article XXIV) perspectives in isolation, the AUs SFM must be assessed in conjunction with the general WTO classification of the AUMSs. This is because of the special and differential treatment afforded to developing and least developed WTO Members in terms of paragraph 2 of the preamble to the WTO Agreement, which will be addressed next.59

3.3 WTO compatibility of the AUs SFM from a MFN and RTA perspective taking into account the rules on special treatment for developing countries

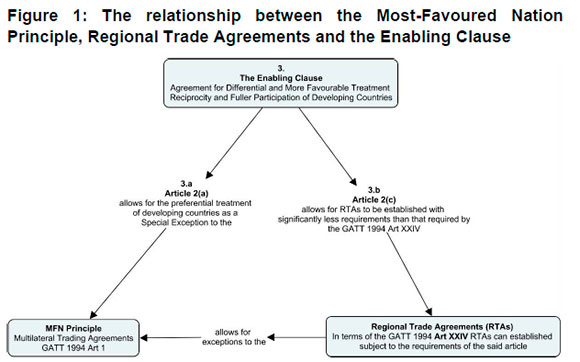

The WTO Agreement in paragraph 2 of its preamble explicitly states that the developed WTO members should through their trade relations strive to increase the living standards, employment and real income of the developing and least developed WTO members. The GATT 1994 as administered by the WTO includes many provisions specifically dedicated to allowing for the special and differential treatment afforded to developing and least developed WTO members. Arguably, the most significant of all special and differential treatment provisions of the GATT 1994 was established on 28 November 1979.60 On this date, a decision labelled L/4903 was taken to establish the agreement for Differential and More Favourable Treatment Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries, more commonly referred to as the Enabling Clause. In broad terms, developed countries under the Enabling Clause may afford differential and more favourable treatment to developing countries, which would otherwise have been inconsistent with the WTO rules on non-discrimination.

Of particular importance and relevance to the AU is the operation of the Enabling Clause within the spheres of (1) the MFN principle, and (2) RTAs. The WTO classification of the AUMSs as either developing or least developed countries allows for the operation of the Enabling Clause when the AU/WTO member states conclude agreements that would otherwise be WTO-incompatible. The sections of the Enabling Clause relevant to this paper have been extracted and discussed below.

(a) In terms of paragraph (2)(a) of the Enabling Clause, developed countries may afford preferential tariff treatment to products originating in developing countries as a special exception to the MFN principle.

(b) In terms of paragraph (2)(c) of the Enabling Clause, developing countries can amongst themselves conclude preferential trade arrangements under Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 and its understanding which otherwise would be inconsistent with the MFN obligation principle of the WTO. Ordinarily the establishment of a RTA amongst developed WTO Members would need to meet stringent substantive requirements as set out by Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 and its understanding before it is considered valid. However, these stringent requirements do not exist under the Enabling Clause to establish a RTA between WTO Members classified as developing or least developed countries.61

As indicated, the relevant classification of the AU/WTO members allows for the operation of the Enabling Clause when assessing the AUs SFM against the WTOs general rules and regulations.

The Enabling Clause has broad and far-reaching effects on the general WTO rules and regulations related to both the MFN Principle and the establishment of RTAs. We have therefore constructed figure 1, that illustrates the interconnected relationship between the MFN principle, RTAs and the Enabling Clause.

Figure 1 will be used by the authors to isolate the respective concepts marked starting with the Enabling Clause and to address them separately where appropriate and then in combination via the conceptual linkages. The specific number and letter combination of the concept map will be referenced in the sections to follow so that the reader can follow the discussion accordingly. The self-financing mechanism will then be assessed in section 4.4 against these concepts based on the same logic.

3.3.1 The Enabling Clause

The effect of the Enabling Clause needs to be addressed from the MFN (3.a) and RTAs (3.b) perspective. From the MFN perspective, developed countries in terms of (3.a) Article 2(a) of the Enabling Clause can have preferential trade agreements with developing countries, which will be considered WTO-compatible. From a RTA perspective, developing countries in terms of (3.b) Article 2(c) of the Enabling Clause can amongst themselves establish RTAs which will be considered WTO-compatible even if the agreed rates are lower than those charged to WTO Members not party to the RTAs. The following sections will address the MFN and RTA perspectives considering the operation of the Enabling Clause.

3.3.1.1 The Enabling Clause - MFN perspective

A significant majority of the AUMSs' international trade transactions are concluded with countries in North, South and Central America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia, most of which are developed countries in terms of WTO classification. With reference to paragraph (2)(a) of the Enabling Clause, developed countries can afford to give developing and least developed WTO Members preferential treatment which otherwise would be WTO-incompatible.

3.3.1.2 The Enabling Clause - RTA perspective

With reference to paragraph (2)(a) of the Enabling Clause, developing and least developed WTO Members can amongst themselves, with fewer requirements than that required as per Article XXIV of the GATT 1994, establish a RTA that would be WTO compatible. In January 2012 the AU at the 18th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia adopted a decision to form an African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) with the aim of initial implementation as from the year 2017.62 The AfCFTA Agreement will bring together all 55 AUMSs, potentially forming the biggest Free Trade Area (FTA) since the establishment of the WTO. Of all the AUMSs, only Eritrea has not signed the agreement.63 The AfCFTA Agreement's implementation date was set as 1 January 2021 at the 12thExtraordinary Session of the Assembly of the African Union in Niamey, Niger on 7 July 2019. Of the 54 AUMSs that have signed the AfCFTA Agreement, only 28 AUMSs have deposited their instruments of ratification with the Chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC).64 As of 5 October 2020, it is noted per the official WTO RTAs database that no notification or application for the AfCFTA Agreement to be registered as a RTA has been recorded.65 Therefore the AU's SFM should be considered WTO incompatible from a RTA perspective before taking into account the operation of the Enabling Clause.

3.4 Tentative conclusion based on analysis and possible corrective actions

Based on the application of the relevant WTO rules and principles before considering the operation of the Enabling Clause, it would appear that the SFM in its current form is WTO-incompatible from both a MFN principle and RTA perspective as Articles I and XXIV of the GATT 1994 respectively are not being adhered to.

However, considering the Enabling Clause and its consequential effects on the MFN principle and RTAs, special and differential treatment can be sought for the SFM, given the WTO's general classification of the AUMSs. The possible corrective actions can be grouped into a temporary short-term and a permanent long-term suggestion in nature, considering any possible future reclassification of any AUMSs' status as developed countries.

Most of the AUMSs are either developing or least developed countries in terms of the WTO classifications and the preamble to the WTO Agreement recognises the responsibility to try to raise the standard of living amongst the developing and least developed countries.66 It has been noted, however, that no application for a special waiver has been sought to activate the Enabling Clause as developing or least developed countries.67 An application under the provision of paragraph (2)(a) of the Enabling Clause for the AU's SFM to be WTO-compatible would be a short-term solution. The reason for this is that other WTO Members can apply to the WTO for the classification of developing or least developed countries to be changed to developed countries, which would render the provisions of the Enabling Clause inapplicable.

As a long-term suggestion to the SFM's possible WTO incompatibility, the AU should apply to the WTO to have the AfCFTA Agreement registered as a FTA in terms of Article XXIV of the GATT 1994. Successful registration would allow the AUMSs to charge different rates amongst themselves as would be required to charge WTO Members not part of the FTA. The successful registration of the AfCFTA Agreement as a FTA would fundamentally allow the AUMSs to implement the AUs SFM without contravening the rules and regulations of the WTO anti-discrimination principles.

The AU should as a temporary short-term measure apply to the WTO for the AfCFTA Agreement to be registered as a RTA under the non-restrictive requirements of the Enabling Clause, which would allow for the circumvention of the MFN principle in terms of Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 and its understanding. By having the AfCFTA Agreement registered as a RTA under the Enabling Clause, the AUMSs would be able to eliminate trade barriers within the FTA group and still implement the SFM, which should be considered WTO-compatible.68 The support for the AfCFTA Agreement was echoed by Deputy Director-General Alan Wolff of the WTO in a speech delivered at Addis Ababa University on 11 February 2020 in which he congratulated the African leaders on the signing of the AfCFTA Agreement and considered it a significant step towards achieving the sustainable development goals of peace and prosperity in Africa.69 The long-term problem that could ultimately exist for the registration of the AfCFTA Agreement as a FTA under the Enabling Clause is that other WTO members can apply to the WTO for some of the AUMSs' classifications to be changed from developing or least developed countries.

Therefore, as a permanent long-term suggestion it would be imperative that the AU work towards meeting the requirements of Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 to have the AfCFTA Agreement registered as a FTA with the WTO without the provisions of the Enabling Clause. This should be a priority whilst the AUMSs are generally all classified as developing or least developed countries.

4 Conclusion

In the preamble to the WTO Agreement, a relevant extract of the objectives for its establishment states the following:

Recognizing further that there is need for positive efforts designed to ensure that developing countries, and especially the least developed among them, secure a share in the growth in international trade commensurate with the needs of their economic development.

The AU's attempt to achieve self-reliance and independence is important to Africa as a whole. For as long as the AU is dependent on donor funding for its basic operations, it will not be able to make objective decisions to the benefit of Africa without fear of losing the funding. This paper tries to address the balancing act required between achieving the goals and objectives of the AU through self-reliance and ensuring that the mechanisms used to achieve self-reliance are WTO-compatible.

To address this need for self-reliance, the AU proposed a SFM in the form of a 0.2 per cent levy on all eligible goods imported into the territory of the AU. As discussed in part 3, the SFM in its current form can be considered to be WTO-incompatible.

The AU needs to consider the suggestions presented to make the SFM compatible with the WTO rules and regulations to avoid any disputes that might arise because of the SFM. The current incompatible WTO status of the SFM could severely undermine the intention of the AU to become self-reliant. Even though the SFM might not have been officially challenged by a WTO Member yet, it is better to be compliant with the WTO rules and regulations than to trust in the goodwill of the other WTO Members.

The SFM is, in the authors' view, a significant step towards the pursuit of independence and self-reliance and ultimately the greater good of Africa. With reference to the opening quotation, the authors conclude this paper with the following statement: independence cannot be achieved without a significant measure of self-reliance and this independence cannot be conferred by anyone. It can be developed only from within those who seek it. This is very much the scenario in which the AU finds itself. Bravery and technical acumen are required from the AU's leadership to bridge the gap between the AU's independence and the technical requirements of the WTO.

Bibliography

Literature

Adams G A Critical Analysis of the African Union's Self-Financing Mechanism (MPhil Law-dissertation University of the Western Cape 2018) [ Links ]

Apiko P and Aggad F Analysis of the Implementation of the African Union's 0.2% Levy: Progress and Challenges (European Centre for Development Policy Management Maastricht 2017) [ Links ]

Van den Bossche P and Zdouc W The Law and Policy of the World Trade Organisation: Text, Cases and Materials 4th ed (Cambridge University Press New York 2018) [ Links ]

International instruments

Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000)

Differential and More Favourable Treatment, Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries (1979)

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1994)

Trade Agreement Between Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) (2006)

Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation (1994)

Internet sources

Amadeo K 2020 Multilateral Trade Agreements: Pros, Cons and Examples https://www.thebalance.com/multilateral-trade-agreements-pros-cons-and-examples-3305949 accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2001 Assembly of Heads of State and Government Thirty-Seventh Ordinary Session https://au.int/en/decisions/assembly-heads-state-and-government-thirty-seventh-ordinary-session accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2020 AU in a Nutshell https://au.int/en/au-nutshell accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2018 Background Paper on Implementing the Kigali Decision on Financing the Union https://au.int/web/en/financing-union-document accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2018 Decisions, Declarations and Resolution of the Assembly of the Union Twenty-Seven Ordinary Session https://au.int/en/decisions-2 accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2018 Financing of the Union "By Africa, for Africa" https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/31955-file-what20is20financing20of20the20union-1-2.pdf accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2018 The Gap Between the Planned Commission Budget and Actual Budget that is Funded by Both Member States and the Partners: 2011-2015 https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/35739-file-faqs_on_financing_of_the_union.pdf accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2019 Africa is Financing its Development Agenda Through Domestic Resource Mobilization https://au.int/en/articles/africa-financing-its-development-agenda-through-domestic-resource-mobilization accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

African Union 2020 AU COVID-19 Response Fund https://au.int/en/aucovid19responsefund accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Dictionary of International Trade 2018 Multilateral Agreement https://www.globalnegotiator.com/international-trade/dictionary/multilateral-agreement/ accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Douglass F 2018 Quotation Collection http://www.quotationcollection.com/author/Frederick-Douglass/quotes accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Erasmus G 2017 The New Self-Financing Mechanism of the African Union: Can the Proposed AU Levy be a Step Towards Financial Independence? https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/11661-the-new-self-financing-mechanism-of-the-african-union-can-the-proposed-au-levy-be-a-step-towards-financial-independence.html accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Fabricius P 2016 AU Self-Funding Plan Cautiously Welcomed https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/au-self-funding-plan-cautiously-welcomed-2046731 accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Miyandazi L 2016 Is the African Union's Financial Independence a Possibility? http://ecdpm.org/talking-points/african-union-financial-independence/ accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Oji EC and Lusignan B 2004 The Africa Union: Examining the New Hope of Africa https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297a/The%20African%20Union%20-%20Examining%20the%20New%20Hope%20For%20Africa.pdf accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Tralac 2018 African Continental Free Trade Area Legal Texts and Policy Documents https://www.tralac.org/resources/our-resources/6730-continental-free-trade-area-cfta.html accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

Tralac 2020 African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Legal Texts and Policy Documents https://www.tralac.org/resources/by-region/cfta.html accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

World Trade Organisation date unknown Understanding on the Interpretation of Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994 https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/10-24.pdf accessed 16 June 2022 [ Links ]

World Trade Organisation 2018 Map of Negotiating Groups in the Doha Negotiations https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dda_e/negotiating_groups_maps_e.htm?group_selected=GRP007 accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

World Trade Organisation 2020 DDG Wolff Affirms WTO Commitment to Support Africa's Economic Integration https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news20_e/ddgaw_11feb20_e.htm accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

World Trade Organisation 2020 Members and Observers of the WTO https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/org6_map_e.htm accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

World Trade Organisation 2020 Principles of the Trading System https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact2_e.htm#top accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

World Trade Organisation 2020 Regional Trade Agreements Database http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx accessed 25 November 2021 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

AfCFTA African Continental Free Trade Area

AUC African Union Commission

AUCA Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000)

AUMS African Union Member State

AU African Union

EFTA European Free Trade Association

FTA Free Trade Area

GATT 1994 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1994)

MFN Most-Favoured-Nation

NT national treatment

OAU Organisation of African Unity

RTA Regional trade agreement

SACU Southern African Customs Union

SFM self-financing mechanism

WTO World Trade Organisation

Date Submission: 8 January 2021

Date Revised: 2 August 2022

Date Accepted: 2 August 2022

Date published: 12 December 2022

Editor: Dr A Storm

* Gordon Adams. BComm Accounting BComm Accounting Honours CA (SA) M Phil (Law). Lecturer, Economics and Management Science Faculty, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. Email: goadams@uwc.ac.za. ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9144-6742.

** Patricia Lenaghan. BLC LLB LLM LLD. Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. E-mail: plenaghan@uwc.ac.za. ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0002-1145-3350.

1 Douglass 2018 http://www.quotationcollection.com/author/Frederick-Douglass/quotes.

2 Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000).

3 AU 2018 https://au.int/en/au-nutshell.

4 Miyandazi 2016 http://ecdpm.org/talking-points/african-union-financial-independence/.

5 AU 2018 https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/35739-file-faqs_on_financing_of_the_union.pdf 2.

6 AU 2018 https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/35739-file-faqs_on_financing_of_the_union.pdf 1.

7 AU 2018 https://au.int/web/en/financing-union-document 8.

8 Apiko and Aggad Analysis of the Implementation of the African Union's 0.2% Levy 2.

9 Apiko and Aggad Analysis of the Implementation of the African Union's 0.2% Levy 2.

10 AU 2018 https://au.int/en/decisions-2.

11 AU 2018 https://au.int/en/decisions-2.

12 Erasmus 2017 https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/11661-the-new-self-financing-mechanism-of-the-african-union-can-the-proposed-au-levy-be-a-step-towards-financial-independence.html.

13 AU 2020 https://au.int/en/aucovid19responsefund

14 People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, Union of the Comoros, Republic of Equatorial Guinea, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Libya, Federal Republic of Somalia, Republic of South Sudan and Republic of the Sudan.

15 Republic of the Congo, State of Eritrea, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Democratic Republic of Sâo Tomé and Principe.

16 WTO 2020 https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/org6_map_e.htm.

17 Erasmus 2017 https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/11661-the-new-self-financing-mechanism-of-the-african-union-can-the-proposed-au-levy-be-a-step-towards-financial-independence.html.

18 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1994) (GTT 1994) Preamble.

19 AU 2018 https://au.int/en/au-nutshell.

20 WTO 2018 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dda_e/negotiating_groups_maps_e.htm?group_selected=GRP007. The reader is instructed to select the least-developed countries from the drop-down list.

21 Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Congo Republic, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Togo.

22 Chad and Gambia

23 Nigeria, Comoros, Senegal, Mauritania, Ethiopia and Libya.

24 AU 2019 https://au.int/en/articles/africa-financing-its-development-agenda-through-domestic-resource-mobilization.

25 Fabricius 2016 https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/au-self-funding-plan-cautiously-welcomed-2046731.

26 AU 2018 https://au.int/web/en/financing-union-document 4-5.

27 For a more detailed overview, see Adams Critical Analysis of the African Union's Self-Financing Mechanism 57-58.

28 AU 2018 https://au.int/web/en/financing-union-document 7. The interested reader is referred to p 8, figure 4 of the document referenced above to get a more comprehensive picture of the recent differences between the requested and actual funding received from the development partners.

29 AU 2018 https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/31955-file-what20is20financing20of20the20union-1-2.pdf 13.

30 AU 2001 https://au.int/en/decisions/assembly-heads-state-and-government-thirty-seventh-ordinary-session.

31 AU 2018 https://au.int/web/en/financing-union-document 2.

32 Oji and Lusignan 2004 https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297a/The%20African%20Union%20-%20Examining%20the%20New%20Hope%20For%20Africa.pdf 14.

33 The funding sources included: (1) a US$2.00 hospitality levy per stay in a hotel; or (2) a text message levy of US$0.05 cents per message; or (3) a US$5.00 travel levy per flight ticket coming into the African Continent from outside of Africa.

34 Apiko and Aggad Analysis of the Implementation of the African Union's 0.2% Levy 2.

35 Apiko and Aggad Analysis of the Implementation of the African Union's 0.2% Levy 2.

36 AU 2018 https://au.int/en/decisions-2

37 AU 2018 https://au.int/en/decisions-2.

38 AU 2018 https://au.int/web/en/financing-union-document.

39 See fns. 14-15 for the AUMSs WTO membership breakdown.

40 Dictionary of International Trade 2018 https://www.globalnegotiator.com/international-trade/dictionary/multilateral-agreement/. A multilateral agreement is an agreement between three or more contracting WTO Members. The most significant example of this type of trade agreement is the GATT 1994 which applies to all WTO Members.

41 Regional trade agreements are reciprocal trade agreements between two or more WTO Members and include free trade agreements and customs unions. An example of this is the agreement for the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

42 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 37-38, 673.

43 Amadeo 2020 https://www.thebalance.com/multilateral-trade-agreements-pros-cons-and-examples-3305949.

44 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 679.

45 WTO 2020 https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact2_e.htm#top.

46 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 39.

47 Compared to what was previously granted or initially agreed to in terms of the GATT 1994.

48 Like products are not defined in terms of the GATT 1994 and the term has different meanings in different contexts. For the purpose of this paper, like products will be considered to be directly substitutable products. The interested reader is referred to the following for a detailed analysis: Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 316-319, 354-363.

49 These circumstances are deemed beyond the scope of this paper and are therefore not addressed.

50 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 311-321.

51 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 311-314.

52 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 314-315.

53 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 316-319.

54 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 319-321.

55 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 42.

56 WTO date unknown https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/10-24.pdf, hereafter referred collectively to as Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 and its understanding.

57 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 685.

58 Erasmus 2017 https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/11661-the-new-self-financing-mechanism-of-the-african-union-can-the-proposed-au-levy-be-a-step-towards-financial-independence.html.

59 The WTO Differential and More Favourable Treatment, Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries (1979) 191.

60 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 321-325.

61 Van den Bossche and Zdouc Law and Policy of the WTO 687.

62 Tralac 2020 https://www.tralac.org/resources/by-region/cfta.html.

63 Tralac 2018 https://www.tralac.org/resources/our-resources/6730-continental-free-trade-area-cfta.html.

64 Tralac 2018 https://www.tralac.org/resources/our-resources/6730-continental-free-trade-area-cfta.html.

65 WTO 2020 http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx.

66 WTO 2018 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dda_e/negotiating_groups_maps_e.htm?group_selected=GRP007.

67 Erasmus 2017 https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/11661-the-new-self-financing-mechanism-of-the-african-union-can-the-proposed-au-levy-be-a-step-towards-financial-independence.html.

68 Erasmus 2017 https://www.tralac.org/discussions/article/11661-the-new-self-financing-mechanism-of-the-african-union-can-the-proposed-au-levy-be-a-step-towards-financial-independence.html.

69 WTO 2020 https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news20_e/ddgaw_11feb20_e.htm.