Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versão On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.25 no.1 Potchefstroom 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2022/v25i0a14596

SPECIAL EDITION: FESTSCHRIFT - CHARL HUGO

Financial Services and Arrangements to Facilitate the (Ex)Portability of Social Security Benefits in the Southern African Development Community

LG Mpedi

University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Email: lgmpedi@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This contribution reviews the financial services and arrangements to facilitate the (ex)portability of social security benefits in the Southern African Development Community (the SADC). It commences by providing a general background to the theme it covers by focussing on the (ex)portability of social security as part of the coordination principles contained in the pertinent International Labour Organisation social security conventions, the (ex)portability of social security benefits provided for in SADC social security instruments, the key purpose of the payment of social security abroad, and the negative impact of the absence of the suitable cross-border payment of benefits in the SADC. It proceeds by discussing the common methods used for the cross-border payment of social security benefits in the SADC. These models are business-to-business, business-to-client, government institution-to-government institution, and client-to-business. The contribution continues by reviewing selected challenges in the region facing financial services and arrangements to facilitate the payment of social security abroad. These challenges are the lack of a single currency, remittance costs, and unbanked persons. The paper concludes by making recommendations for developing a coherent regional and enabling framework for the payment of social security benefits abroad.

Keywords: (Ex)portability; social security benefits; social security coordination; financial services; regional integration.

1 General background

1.1 (Ex)portability of social security as part of the coordination principles contained in the pertinent ILO social security conventions

The concept of the transferability or (ex)portability of social security benefits1 is one of the well-known five social security coordination principles.2 These principles which can, for example, be found in the International Labour Organisation (hereinafter the ILO) conventions dealing with social security coordination3 are as follows: equality of treatment, determination of the applicable legislation, maintenance of acquired rights and provision of benefits abroad, maintenance of rights in the course of acquisition, and reciprocity.

1.2 (Ex)portability of social security benefits as provided for in the Southern African Development Community social security instruments

The notion of the (ex)portability of social security benefits is known in the Southern African Development Community (hereinafter the SADC)4 and provided for in several instruments of that regional organisation. For example, article 17(1)(d) of the Code on Social Security in the SADC of 2007 (hereinafter the Code) requires the Member States to ensure that all lawfully employed immigrants are protected through the promotion of core principles such as "the facilitation of exportability of benefits". The Code directs, at article 17(2), that: "These principles should be contained in both the national laws of Member States and in bi- or multilateral arrangements between the Member States."

Secondly, the Member States have adopted the SADC Cross-Border Portability of Social Security Benefits Policy Framework of 2016 (hereinafter the Framework). One of the specific objectives of the Framework is to: "Provide for mechanisms to enable workers moving within and outside the SADC Region to keep the social security rights which they have acquired under the legislation of the one Member State".5 Furthermore, the SADC Member States adopted the Guidelines on the Portability of Social Security Benefits in SADC (hereinafter the Guidelines) in 2020. The Guidelines aim to facilitate cooperation between the Member States on the portability6 of social security benefits.7

In the area of the payment of social security benefits abroad, the Guidelines direct that migrant workers and their dependents from the SADC region may not be legally denied the payment of cash benefits for the mere reason that they reside abroad, or they are absent from the territory of a Member State.8This is important because the sad reality is that:

Regarding the payment of benefits abroad, many countries suspend the payment of benefits to migrant workers who reside abroad, even though they export benefits to their own nationals residing abroad. Some countries completely prohibit the payment of benefits abroad, while others make the export of benefits conditional on the conclusion of reciprocal social security agreements with the countries of residence. Still others may only offer a lump-sum benefit in place of a pension if the insured person leaves the country. Such limitations may be due to monetary restrictions or to administrative problems (e.g., benefits in kind such as medical services cannot be provided directly by the competent social security institution outside of its area of competence), but may also be based on the underlying conception that a State is only responsible for those persons living within its own borders.9

In addition, the Guidelines require the Member States to introduce measures that are aimed at reducing the challenges migrant workers are confronted with in their quest to access social security.10 Furthermore, the Member States agreed to conclude bilateral and multilateral arrangements to facilitate the portability of the benefits.11 The abovementioned SADC instruments are the right step in the right direction.12 However, it is regrettable that these instruments are soft law. Accordingly, they are not binding. The SADC region needs to adopt a binding instrument that will, inter alia, make provision for the payment of benefits abroad as a matter of urgency.13

1.3 Key purpose of the payment of social security abroad

The payment of social benefits abroad or the exporting of benefits endeavours to guarantee the social security rights of the migrant workers. As pointed out by Hirose, Nikac and Tomagno:14

Protecting the right of migrant workers to social security is important, not only for securing the equality of treatment in social security for migrant workers, but also for extending social security coverage to currently unprotected population. Increasing social security coordination between countries through bilateral and multilateral agreements and the ratification of relevant international conventions should be a high priority of social policy as the well-being of millions of migrant workers and their families are at stake. Furthermore, the portability of social security rights does not only bear significance for the workers and their families, but undoubtedly facilitates the free movement of labour within and across economic zones and is, therefore, indispensible (sic) for the proper functioning of integrated labour markets.

In essence, the (ex)portability of social security benefits enables the migrant workers and their dependents to access the benefits in their home country.15

1.4 Negative impact of the absence of suitable cross-border payment of benefits in SADC

Notwithstanding its role and importance, the (ex)portability of social security benefits in the SADC region is, in practice, very limited.16 This is due to a variety of factors which include the shortage of social security coordination agreements in the region.17 The absence of an appropriate regional cross-border payment of benefits regime and lack of information or ignorance among ex-migrants has resulted in unclaimed benefits. For instance, in 2017 it was estimated that there were R10 billion unclaimed in mineworkers' retirement funds in South Africa, which situation was attributed to "failure by many employers or funds to provide proper information to employees, such as informing them of their entitlement to withdrawal if they resign, are dismissed or retrenched from their employment and how to claim a benefit when it accrues".18 Notwithstanding the reasons advanced, this is problematic, particularly when one considers the fact that many former migrant workers and their families now live in abject poverty.

2 Common methods used for the cross-border payment of social security benefits

Four models followed in the region for the cross-border payment of social security benefits are discernible, namely: business-to-business, business-to-client, government institution-to-government institution, and client-to-business.

2.1 Business-to-business

The business-to-business transmission of benefits from one country to another involves the handling of benefits by businesses. The benefits go through "several hands", among corporate entities, before they reach the intended beneficiaries in the country of the migrant workers' origin. For example, the payment of benefits due to ex-mineworkers who worked in South Africa invariably involves the relevant social security fund, TEBA in South Africa, a bank (in the ex-mineworkers country of origin) and a local TEBA office.19 TEBA is a key player in the sense that it renders a variety of pertinent services, which include cash transmission, as well as compensation and other industry monetary benefits.20 TEBA plays an important role in the facilitation of the cross-border payment of benefits in favour of ex-mineworkers who were employed in South Africa. However, it no longer has offices in Malawi.21 This has placed the ex-mineworkers in that country in a disadvantageous position. Pensions due to Malawian ex-mineworkers are paid in Malawi by the Rand Mutual Company to the National Bank of Malawi.22

The National Bank of Malawi disburses the benefits and receives life certificates23 on behalf of the Rand Mutual Assurance Company. The standard practice is for the social security institution effecting the cross-border payment of benefits to cover the incidental administrative costs. For instance, Rand Mutual Assurance Company is reported to pay the benefits into the private bank accounts of the beneficiaries in countries such as Lesotho and Eswatini. It then funds the administrative costs which have been negotiated as a flat fee. It must be pointed out that the volatility of the currency for SADC countries that are not part of the Common Monetary Area (hereinafter the CMA),24 affects the value of the benefit payable to the beneficiary. In addition, the value of the amount to be paid is negatively undermined by the differences in regional banking systems which are reported to be responsible for the delays in the clearing of funds disbursed and additional costs which are born by the client.25 The business-to-business model is prevalent in the mining sector where TEBA is a key player and between countries that have a bilateral labour agreement with South Africa.26 The biggest challenge is that TEBA does not have a presence in all the Southern African countries (e.g., Malawi). The advantage of this approach is that the transaction costs are generally borne by the businesses and not the beneficiaries.

2.2 Business to client (individual payment)

There are social security funds in the region that pay benefits directly to the bank accounts of the former foreign employees. This occurs often in instances where migrant workers are paid a lump-sum benefit upon the termination of employment. This is the case in countries such as South Africa and Malawi. The preferred retirement insurance for most mineworkers in South Africa is a provident fund.27 This fund pays out a lump sum at retirement. The point is that migrants are entitled in South Africa to receive their retirement benefits in full upon departure from that country.28

The Malawian Pension (Payment of Benefits from Pension Funds) Directive of 29 August 2014 makes provision for the payment of the pension benefits of a member leaving that country permanently. It directs a trustee of a pension fund to pay the benefits from a pension fund on the ground that a member has left or is about to leave Malawi permanently.29 A member of the pension fund is required to provide details of the destination country, including the town, city or address of residence as well as documentation showing the emigration status.30 In addition, the Pension (Payment of Benefits from Pension Funds) Directive obliges a trustee to set up control measures to curb fraud in the payment of benefits.31 A trustee has a statutory duty to verify the identity of the member of the beneficiary before making payment.32 This approach is beneficial in the sense that the migrant worker or his or her dependants gets paid the benefit in full into his or her (the dependants') bank account. However, in practice this is easier said than done due to financial exclusion.

2.3 Government institution-to-government institution

This form of cross-border payment of benefits consists of a situation where a national social security institution pays an amount of money to an embassy which will in turn remit it to its home government for disbursement as benefits to its nationals who are former migrant workers. Such an arrangement is reported to exist between the National Social Security Authority (hereinafter the NSSA) of Zimbabwe and the Malawian Embassy.33 The NSSA pays the associated bank charges for transferring money to the Malawian Embassy's account. The Malawian government is then responsible for paying the cost of transferring the pension. According to Keendjele, this is because "pensioners in Malawi receive their benefits in full at the ruling exchange rate".34 Another example of a government-to-government model of cross-border payment of benefits is that of Zambia and Malawi. The Zambian Government remits pensions to Malawi in favour of Malawians who worked in Zambia. The Malawian Government assists in the tracing of such workers and remitting the relevant documents back to Zambia, through the Zambian Embassy, for further processing. This arrangement is non-reciprocal. It exists largely due to gaps in the cross-border payment of social security benefits arrangements and its use is likely to diminish when an appropriate regional framework is established. In the end, this payment mechanism is not ideal, and it is accordingly not to be recommended or encouraged.

2.4 Client-to-business

The client-to-business remission of benefits occurs largely in the instance where the benefits are paid as a lump sum upon the termination of employment in the host country. It should be recalled that the available options for the migrant workers who contributed to a provident fund include taking the full fund credit as cash. Migrant workers would then remit the money through formal channels to the country of origin. The formal remittance channels in the region include commercial banks, money transfer operations (MTOs), post office services, money transfers via telecommunications companies, retail outlets and courier services.35 The total costs of remitting the money in the SADC vary from one country to another.36 South Africa, on the one hand, has been identified as the most expensive country to remit money from.37 Lesotho, on the other hand, is hailed as the cheapest country. This is largely credited to its "lower regulatory barriers for remitting between countries in the Common Monetary Area (CMA))".38 This is mainly because:

There are no foreign exchange restrictions between banks of the CMA member countries in respect of cross-border transactions amongst themselves. Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland [now Eswatini] have their own monetary authorities and legislation. The application of exchange control within the CMA is governed by the Multilateral Monetary Agreement. Investments and transfers of funds in Rand from/to South Africa to/from other CMA countries do not require the approval of the Financial Surveillance Department.39

In addition, the cost of remitting the money in the SADC is estimated to be "significantly higher than other regions of the world".40 SADC countries must strive toward easing the regulatory challenges of remitting the money in the region. This should make it easy to remit benefits across the borders.

3 Financial services and arrangements to facilitate the (ex)portability of social security benefits: Selected challenges

3.1 Single currency in SADC

Monetary Union and Single Currency are part of the five regional integration milestones of the SADC.41 To date, the region does not have a single currency. Indeed, a single currency in a regional economic community or between the Member States is not a precondition for the successful portability of the social security benefits regime. Nevertheless, its relevance and importance cannot be emphasised enough, especially when it comes to matters such as the reduction of costs associated with the cross-border payment of benefits. It is important to note that the value of currencies fluctuates from time to time, and this influences the rate of the amount remitted.42 In addition, there is the persistent problem of the (non-)exportability of currency that hinders cross-border payments. This challenge has been summed up by Mpedi, Smit and Nyenti as follows:

The (non-)exportability of currency is a matter that is regulated and, at times, restricted by law in most countries. In some instances, the approval of the Central Bank has to be sought and granted before money can be exported. There is nothing wrong with such a requirement. However, cumbersome currency restrictions may impede the conclusion of portability agreements and the eventual payment of social security in some countries.43

Eswatini, Lesotho, South Africa, and Namibia are members of the Common Monetary Area. These countries use the South African Rand (ZAR). It is believed that this is a good basis for addressing the challenges associated with currency conversion and inflation as well as the shortage of foreign currency as frequently experienced in Zimbabwe.44

3.2 Remittance costs

Southern Africa has been flagged as one of the regions with excessive remittance costs.45 The five most expensive remittance corridors in sub-Saharan Africa are in the SADC region. These corridors are South Africa to Eswatini, South Africa to Zambia, South Africa to Angola, South Africa to Botswana and Angola to Namibia.46 The Member States, such as South Africa, need to lower the remittance costs. These are more than necessary as the high costs erode the value of the benefits before they reach the intended beneficiaries.47 This is crucial, especially when one considers the reality that countries such as Lesotho (20.9% of Gross Domestic Product) and Zimbabwe (8.2% of Gross Domestic Product) are listed among the topmost remittance-dependent African countries by share of the Gross Domestic Product.48 In addition, remittances are vital for the survival of many households in remittance-dependent countries of the region.49

3.3 Unbanked persons

Financial exclusion is rife in the SADC. According to the SADC: "In the area of financial inclusion, 32 per cent of adults in the SADC Region are financially excluded, which is around 45.7 million individuals against the target of 25 per cent by 2021. Overall levels of financial inclusion vary considerably across the region, from 97 per cent in Seychelles to 40 per cent in Mozambique."50 There are many individuals, especially in rural areas, who do not have a bank account. Barriers to financial inclusion are diverse and they include poor physical infrastructure, a lack of documentation by potential consumers, and a lack of products suitable for the needs of the (low-income) consumers.51 Another point to note is that financial institutions are invariably situated in urban areas. As a result, those persons who live in (deep) rural areas are excluded and marginalised from the banking systems in the region. It is imperative that banking and/or financial services are brought closer to the underserved and unserved communities. SADC member countries should minimise the regulatory red tape to promote the establishment of innovative ways and means to serve these communities.

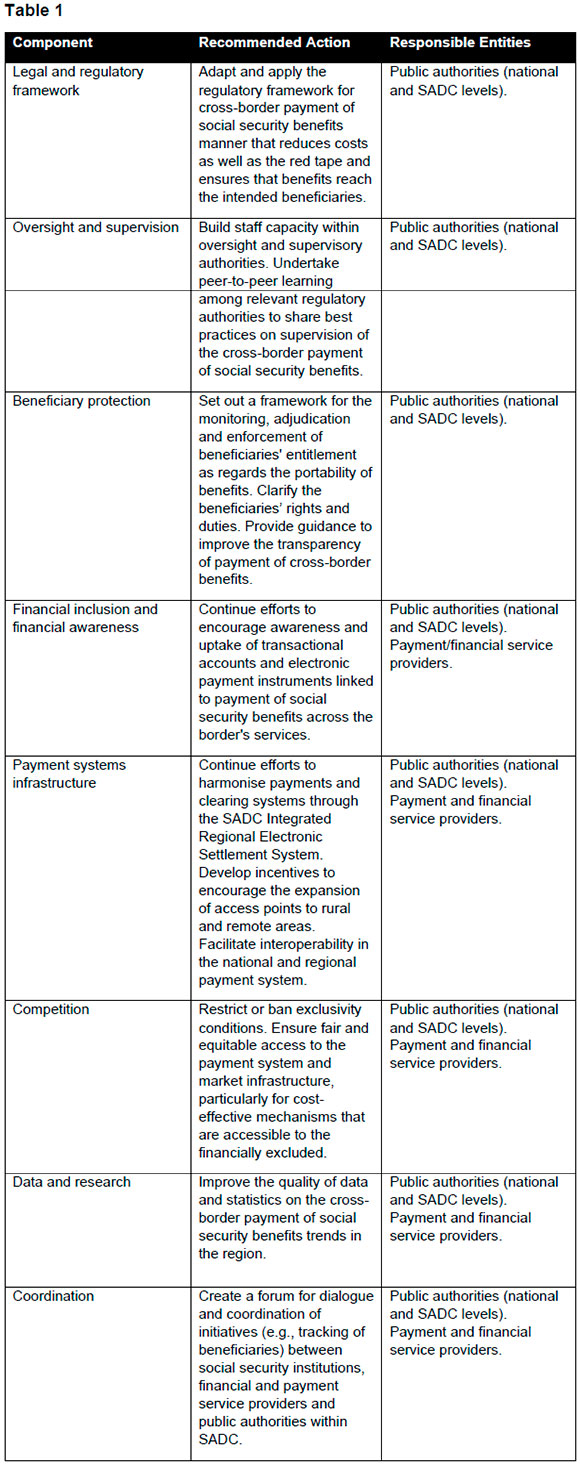

4 Developing a coherent regional and an enabling framework

The SADC region is desperately in need of a coherent regional system and an enabling framework that will facilitate the (ex)portability of social security benefits for former migrant workers. Therefore, the following recommendations are of the utmost importance:52

5 Concluding thoughts and observations

As shown in the contribution, financial services and arrangements to facilitate the (ex)portability of social security benefits are not foreign concepts in the SADC region. However, it is abundantly clear that the available services and arrangements are inadequate. The SADC is desperately in need of a coherent and enabling framework to ensure that social security benefits are paid abroad without let or hindrance. Therefore, the SADC as a regional organisation needs to adopt a binding regional instrument that will facilitate the payment of social security benefits abroad. Secondly, the SADC countries must conclude binding pertinent bilateral and multilateral social security arrangements. This will take some serious political will on the part of the Member States. Furthermore, the SADC countries need at the country and regional level to work towards the adoption of a single currency, lowering remittance costs and extending access to the banking systems to the unbanked members of their populations. Failure to address these issues is a luxury that the region cannot afford, given the rampant socio-economic challenges such as poverty that migrant workers and their families must contend with in that part of the world.

6 Personal tribute to Charl Hugo

Charl and I first met in 2004 or 2005 in Munich, Germany. It was a brief meeting over coffee with a mutual colleague. However, he left a lasting impression on me. He spoke gently and listened intently. Little did we know then that our paths would cross again in future when we both worked at the same Faculty of Law. It was during this period that I got to know Charl reasonably well. You see, Charl and I have a common love for nature and the Kruger National Park. I fondly call him Nare ya Mokgalabye (the old buffalo/die ou buffel) and he calls me Tau (lion/leeu). Nare and I get along very well. Our relationship is based on trust and mutual respect that has developed over the years. I have learned so much from Nare and feel blessed that our paths crossed. He always speaks his mind. However, he prioritised the collective needs and interests of the team. Nare always takes an interest in people he comes across irrespective of their background. It is through his curious nature that we discovered that Nare is the only person who was not present at my baptism who knows the place, river, and exact spot where I was baptised. Those who know Nare will tell you that he is a birder par excellence. Before I met him, birds were to me just another category of creatures that made it into Noah's Ark before the great flood. But now, thanks to Nare, I am sure to spend a minute or two appreciating these amazing creatures whenever and wherever I see them. As the old buffalo slows down from a remarkable career, I wish to say that Nare will be sorely missed by his students, colleagues (especially the junior ones that he took great pleasure in mentoring) and friends, myself included. There are many wonderful memories we made with Nare that we will treasure for the rest of our lives. I will always remember one evening around a fire in Vaalwater where Nare played the guitar and sang John Denver's Take me home, country roads. Thanks, Nare, for your friendship, hard work and kind support. We could have not done many of the things we achieved without you. Tsela tshweu, Nare ya mokgalabye! Mooiloop, die ou buffel! You have earned the right to rest easy in a warm pool of mud, Dagga boy!

Bibliography

Literature

Dupper O "Migrant Workers and the Right to Social Security: An International Perspective" in Becker U and Olivier M (eds) Access to Social Security for Non-Citizens and Informal Sector Workers (Sun Press Stellenbosch 2008) 13-56 [ Links ]

Hirose K, Nikac M and Tomagno E Social Security for Migrant Workers: A Rights-based Approach (ILO Geneva 2011) [ Links ]

Keendjele D Social Protection in SADC: The Report of the Study on Access to and the Portability of Social Security Benefits by Migrant Mine Workers in the SADC Region (2018) (Unpublished Report Prepared for the ILO) [ Links ]

McGillivray W Strengthening Social Protection for African Migrant Workers through Social Security Agreements (ILO Geneva 2010) [ Links ]

Mpedi LG "Molao wa tshireletso ya leago ka mo go ditshaba tseo di hlabologago tsa borwa bja Afrika" 2011 De Jure 18-31 [ Links ]

Mpedi LG "Portability of Accrued Social Security Benefits within the SADC Region Policy Framework: Opportunities, Pitfalls and Challenges" in Olivier MP, Mpedi LG and Kalula E (eds) Liber Amicorum: Essays in Honour of Professor Edwell Kaseke and Dr Mathias Nyenti (Sun Press Stellenbosch 2020) 221-230 [ Links ]

Mpedi LG and Nyenti MAT Towards an Instrument for the Portability of Social Security Benefits in the Southern African Development Community (Sun Press Stellenbosch 2017) [ Links ]

Mpedi LG, Smit N and Nyenti MAT "Access to Social Services for NonCitizens and the Portability of Social Security Benefits within the Southern African Development Community: A Synthesis" in Mpedi LG and Smit N (eds) Access to Social Services for Non-Citizens and the Portability of Social Security Benefits within the Southern African Development Community (Sun Press Stellenbosch 2011) 1-64 [ Links ]

Olivier M "Enhancing Access to South African Social Security Benefits by SADC Citizens: The Need to Improve Bilateral Arrangements within a Multilateral Framework (Part I)" 2011 SADC Law Journal 121-148 [ Links ]

Olivier M "Social Protection in SADC: Developing an Integrated and Inclusive Framework - A Rights-Based Perspective" in Olivier M and Kalula E (eds) Social Protection in SADC: Developing an Integrated and Inclusive Framework (Centre for International and Comparative Labour and Social Security Law, RAU and Institute of Development and Labour Law, UCT Cape Town 2004) 21-70 [ Links ]

Olivier M "Social Security Standards in Southern Africa" in Becker U, Pennings F and Dijkhoff T (eds) International Standard-Setting and Innovations in Social Security (Kluwer Law International The Hague 2013) 89-106 [ Links ]

Olivier M "Social Security for Migrants: Does the European Union Framework Provide Lessons for Developments in SADC?" in Bergman J et al (eds) Social Security in Transition (Kluwer Law International The Hague 2002) 107-124 [ Links ]

Osode P "The Southern African Development Community in Legal Historical Perspective" 2003 Journal for Juridical Science 1-9 [ Links ]

Southern African Development Community SADC Financial Inclusion Strategy (SADC Gaborone 2016) [ Links ]

South African Reserve Bank Currency and Exchange Guidelines for Individuals (South African Reserve Bank Pretoria 2019) [ Links ]

Truen S et al Updating the South Africa-SADC Remittance Channel Estimates (FinMark Trust Midrand 2016) [ Links ]

World Bank The Market for Remittance Services in Southern Africa (World Bank Washington DC 2018) [ Links ]

Government publications

Malawi

Pension (Payment of Benefits from Pension Funds) Directive, 29 August 2014

South Africa

GN R162 in GG 27316 of 22 February 2005 (Regulations in terms of the Social Assistance Act 13 of 2004)

International instruments

Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Kingdom of Lesotho Relating to the Establishment of an Office for a Lesotho Government Labour Representative in the Republic of South Africa, Lesotho Citizens in the Republic of South Africa and the Movement of Such Persons Across the International Border (1973)

Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland (Now, Eswatini) Relating to the Establishment of an Office for a Swaziland Government Labour Representative in the Republic of South Africa, Certain Swaziland Citizens in the Republic of South Africa, the Movement of Such Persons Across the Common Border and the Movement of Certain South African Citizens Across the Common Border, and Addendum Thereto (1975)

Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and Government of the Republic of Botswana Relating to the Establishment of an Office for a Botswana Government Labour Representative in the Republic of South Africa, Botswana Citizens in the Republic of South Africa and the Movement of Such Persons Across the International Border (1973)

Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Portugal Regulating the Employment of Portuguese Workers from the Province of Mozambique on Certain Mines in the Republic of South Africa (1964)

Agreement between the Governments of the Republic of South Africa and Malawi Relating to the Employment and Documentation of Malawi Nationals in South Africa (1967)

Code on Social Security in the SADC (2007)

Equality of Treatment (Accident Compensation) Convention (1925)

Equality of Treatment (Social Security) Convention (1962)

Guidelines on the Portability of Social Security Benefits in SADC (2020)

Maintenance of Migrants' Pension Rights Convention (1935)

SADC Cross-Border Portability of Social Security Benefits Policy Framework (2016)

Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention (1952)

Internet sources

Anonymous 2017 R10bn Unclaimed in Mineworkers' Retirement Funds https://www.news24.com/fin24/Money/Retirement/r10bn-unclaimed-in-mineworkers-retirement-funds-20170412 accessed 31 August 2022 [ Links ]

Bisong A, Ahairwe PE and Njoroge E 2020 The Impact of Covid-19 on Remittances for Development in Africa https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/Impact-COVID-19-remittances-development-Africa-ECDPM-discussion-paper-269-May-2020.pdf accessed 31 August 2022 [ Links ]

Hoda A and Rai DK 2019 Totalisation/Portability of Social Security Benefits: Imperatives for Global Action https://icrier.org/pdf/Working_Paper_379.pdf accessed 31 August 2022 [ Links ]

Jefferis K 2019 Zimbabwe's Currency Crisis is Far from Being Resolved https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-12-11-zimbabwes-currency-crisis-is-far-from-being-resolved/ accessed 7 July 2022 [ Links ]

Mpedi LG and Nyenti M 2013 Portability of Social Security Benefits in Mining Sector: Challenges Experienced by Former Mineworkers in Accessing Social Security Benefits in Selected Southern African Countries https://www.africaportal.org/publications/portability-of-social-security-benefits-in-mining-sector-challenges-experienced-by-former-mineworkers-in-accessing-social-security-benefits-in-selected-southern-african-countries/ accessed 31 August 2022 [ Links ]

Southern African Development Community date unknown Single Currency https://www.sadc.int/integration-milestones/single-currency accessed 7 July 2022 [ Links ]

Southern African Development Community 2020 SADC Records Notable Progress in Financial Markets and Regional Integration https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/sadc-records-notable-progress-financial-markets-and-regional-integration accessed 7 July 2022 [ Links ]

List Of Abbreviations

CMA Common Monetary Area

ILO International Labour Organisation

MTOs money transfer operations

NSSA National Social Security Authority

SADC Southern African Development Community

Date Submitted: 01 July 2022

Date Revised: 18 August 2022

Date Accepted: 29 August 2022

Date Published: 27 October 2022

Guest Editor: Dr Karl Marxen

Journal Editor: Prof C Rautenbach

* Letlhokwa George Mpedi. B Juris LLB (Vista) LLM (RAU) LLD (UJ). Professor and Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Academic, University of Johannesburg, South Africa and Visiting Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Email: lgmpedi@uj.ac.za. ORCID: 0000-0003-1075-4140.

1 The exportability of social security benefits essentially means "reducing or eliminating restrictions on the payment of benefits and receipt of services when a worker who had previously been covered by a country's social security scheme is no longer resident in that country". See McGillivray Strengthening Social Protection 3. A social security benefit is deemed to be exportable, in the context of this contribution, if "the payment of the benefit is allowed outside the borders of a country". See Hoda and Rai 2019 https://icrier.org/pdf/Working_Paper_379.pdf 2.

2 See Dupper "Migrant Workers and the Right to Social Security" 13 for further reading.

3 The Equality of Treatment (Accident Compensation) Convention (1925); Maintenance of Migrants' Pension Rights Convention (1935); Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention (1952); Equality of Treatment (Social Security) Convention (1962).

4 The Southern Development Community (SADC) is a Regional Economic Community in Southern Africa consisting of the following Member States: Angola, Botswana, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. See Osode 2003 Journal for Juridical Science 1 for further reading on the history of the SADC.

5 Section 4(1)(a) of the SADC Cross-Border Portability of Social Security Benefits Policy Framework (2016). Also see Mpedi and Nyenti Towards an Instrument for the Portability of Social Security Benefits.

6 "Portability" is defined as the "transfer of accrued social security benefits of a beneficiary and it includes measures aimed at the maintenance of acquired rights and rights in the course of acquisition as well as payment of benefits abroad". See the Definition and Glossary of the Guidelines on the Portability of Social Security Benefits in SADC (2020) (the Guidelines).

7 Guideline 1(2) of the Guidelines.

8 Guideline 5(2)(a) of the Guidelines.

9 Hirose, Nikac and Tomagno Social Security for Migrant Workers 3.

10 Guideline 5(2)(b) of the Guidelines.

11 Guideline 5(2)(c) of the Guidelines.

12 See, for example Mpedi "Portability of Accrued Social Security Benefits" 227 and Mpedi 2011 De Jure 18.

13 A call for such an instrument has been made on several occasions. As Mpedi points out: "The need for a legally binding instrument has been emphasized at a SADC Employment and Labour Sector workshop on the portability of social security benefits. Apart from calling for a binding instrument, the workshop concluded that the instrument should, apart from making provision for the portability of social security benefits, coordinate social security in the SADC region." See Mpedi "Portability of Accrued Social Security Benefits" 227. In addition, Olivier has called for the adoption of specific and concrete measures as follows: "The conclusion is clear: specific and concrete measures need to be adopted at the regional level to deal with the social security plight of intra-SADC migrants, in addition to required changes to national law and practice. Entering into appropriate inter-country arrangements, in particular through bilateral and multilateral agreements, based on accepted international law principles, as contained in the Code on Social Security in the SADC as well, provides a method to achieve this result". See Olivier "Social Security Standards" 105.

14 Hirose, Nikac and Tomagno Social Security for Migrant Workers 2.

15 Hirose, Nikac and Tomagno Social Security for Migrant Workers 13.

16 See Mpedi and Nyenti Towards an Instrument for the Portability of Social Security Benefits.

17 See, for example, Olivier "Social Protection in SADC" 54-60; Olivier "Social Security for Migrants" 121; Olivier 2011 SADC Law Journal 121; Mpedi, Smit and Nyenti "Access to Social Services" 28-33; Mpedi and Nyenti Towards an Instrument for the Portability of Social Security Benefits.

18 Anon 2017 https://www.news24.com/fin24/Money/Retirement/r10bn-unclaimed-in-mineworkers-retirement-funds-20170412.

19 TEBA has offices in southern Mozambique, Lesotho, Eswatini, Botswana and South Africa.

20 Mpedi and Nyenti 2013 https://www.africaportal.org/publications/portability-of-social-security-benefits-in-mining-sector-challenges-experienced-by-former-mineworkers-in-accessing-social-security-benefits-in-selected-southern-african-countries/ 75.

21 Keendjele Social Protection in SADC 31.

22 Keendjele Social Protection in SADC 33.

23 "Life certificate", which is also referred to as proof of life, proof of existence or certificate of existence, is defined as a "statement made and signed under oath or affirmation by a beneficiary before an attesting officer to prove that he or she is alive" (reg 1 of the Regulations in terms of the Social Assistance Act 13 of 2004 (GN R162 in GG 27316 of 22 February 2005)). It should be noted that biometric, voice recognition and facial recognition technology is also used to establish proof of existence.

24 The Common Monetary Area consists of Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa.

25 Keendjele Social Protection in SADC 85.

26 See the Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and Government of the Republic of Botswana Relating to the Establishment of an Office for a Botswana Government Labour Representative in the Republic of South Africa, Botswana Citizens in the Republic of South Africa and the Movement of Such Persons Across the International Border (signed on 24 December 1973 and entered into force on 24 December 1973); Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Kingdom of Lesotho Relating to the Establishment of an Office for a Lesotho Government Labour Representative in the Republic of South Africa, Lesotho Citizens in the Republic of South Africa and the Movement of Such Persons Across the International Border (signed on 24 August 1973 and entered into force on 24 August 1973); Agreement between the Governments of the Republic of South Africa and Malawi Relating to the Employment and Documentation of Malawi Nationals in South Africa (signed on 1 August 1967 and entered into force on 1 August 1967); Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Portugal Regulating the Employment of Portuguese Workers from the Province of Mozambique on Certain Mines in the Republic of South Africa (1964) (signed on 13 October 1964 (amended by exchange of notes on 24 February 1971 and 11 May 1971) and entered into force on 1 January 1965); and Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland (Now, Eswatini) Relating to the Establishment of an Office for a Swaziland Government Labour Representative in the Republic of South Africa, Certain Swaziland Citizens in the Republic of South Africa, the Movement of Such Persons Across the Common Border and the Movement of Certain South African Citizens Across the Common Border, and Addendum Thereto (signed on 22 August 1975 and entered into force on 22 August 1975).

27 Mpedi and Nyenti 2013 https://www.africaportal.org/publications/portability-of-social-security-benefits-in-mining-sector-challenges-experienced-by-former-mineworkers-in-accessing-social-security-benefits-in-selected-southern-african-countries/ 23.

28 Mpedi and Nyenti 2013 https://www.africaportal.org/publications/portability-of-social-security-benefits-in-mining-sector-challenges-experienced-by-former-mineworkers-in-accessing-social-security-benefits-in-selected-southern-african-countries/ 23.

29 Section 8 of the Malawian Pension (Payment of Benefits from Pension Funds) Directive, 29 August 2014 (hereafter the Malawian Pension Directive).

30 Section 8(a)-(b) of the Malawian Pension Directive.

31 Section 14(1) of the Malawian Pension Directive.

32 Section 14(2) of the Malawian Pension Directive.

33 Keendjele Social Protection in SADC 83.

34 Keendjele Social Protection in SADC 83.

35 Truen et al Updating the South Africa-SADC Remittance Channel Estimates 41.

36 Truen et al Updating the South Africa-SADC Remittance Channel Estimates 42.

37 World Bank Market for Remittance Services 18.

38 Truen et al Updating the South Africa-SADC Remittance Channel Estimates 42.

39 South African Reserve Bank Currency and Exchange Guidelines for Individuals 3233.

40 World Bank Market for Remittance Services 7.

41 SADC date unknown https://www.sadc.int/integration-milestones/single-currency.

42 Mpedi and Nyenti 2013 https://www.africaportal.org/publications/portability-of-social-security-benefits-in-mining-sector-challenges-experienced-by-former-mineworkers-in-accessing-social-security-benefits-in-selected-southern-african-countries/ 87.

43 Mpedi, Smit and Nyenti "Access to Social Services" 37.

44 Jefferis 2019 https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-12-11-zimbabwes-currency-crisis-is-far-from-being-resolved/.

45 See Bisong, Ahairwe and Njoroge 2020 https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/Impact-COVID-19-remittances-development-Africa-ECDPM-discussion-paper-269-May-2020.pdf 9.

46 Bisong, Ahairwe and Njoroge 2020 https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/Impact-COVID-19-remittances-development-Africa-ECDPM-discussion-paper-269-May-2020.pdf 9.

47 Mpedi, Smit and Nyenti "Access to Social Services" 37.

48 Bisong, Ahairwe and Njoroge 2020 https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/Impact-COVID-19-remittances-development-Africa-ECDPM-discussion-paper-269-May-2020.pdf 12.

49 Olivier 2011 SADC Law Journal 125.

50 SADC 2020 https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/sadc-records-notable-progress-financial-markets-and-regional-integration.

51 SADC Financial Inclusion Strategy 36-41.

52 Adapted from World Bank Market for Remittance Services ix.