Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.25 no.1 Potchefstroom 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2022/v25i0a14061

SPECIAL EDITION: FESTSCHRIFT - CHARL HUGO

Should Market Value Be Retained as the Only Tax Base for Municipal Property Rates in South Africa?

R Franzsen*

University of Pretoria South Africa. Email: riel.franzsen@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In terms of the Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004 (MPRA), metropolitan and local municipalities in South Africa may levy property rates on property. The MPRA provides for only one tax base, namely "market value". Given the paucity of skills and capacity to prepare credible valuation rolls and given the costs of doing so, especially B3 and B4 local municipalities situated in rural areas are struggling to comply with the valuation-related provisions of the MPRA. A brief review of property tax base options utilised globally indicates that some countries allow for different tax bases (or even different taxes) based on the location and/or use of property and some jurisdictions apply simplified methodologies (such as value banding, points-based assessment or even self-assessment) to assess properties for property tax purposes. In the light of there being viable alternatives to market value and of the challenges faced by many rural local municipalities, the South African government should revisit the policy decision to have only market value as the tax base across vastly different types of municipalities.

Keywords: Property tax; rates; local municipality; municipal valuer; valuation.

1 Background

South Africa has a long history of property taxation. A recurrent property tax modelled on the British system was first introduced in the Cape of Good Hope colony in 1836.1 On the basis of this model, all four former provinces levied a local recurrent tax, referred to as "rates", "assessment rates", or "property rates". Municipalities had the option of selecting one of three possible tax bases, namely land value only (called "site rating"), land and buildings collectively (called "flat rating"), or land and buildings separately (called "composite rating").2 Across the country each of these three systems were used by about a third of municipalities.3 These rating systems were retained throughout the period of local government institutional reform from 1993 to 20004 and were replaced only when a new national property rates regime was implemented in terms of the Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004 (hereafter MPRA).5

South Africa's municipalities derive their power to levy "rates on property" from section 229(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Section 229(2)(b) of the Constitution states that the power of a municipality to impose rates on property may be regulated by national legislation - hence the enactment of the MPRA on 2 July 2005. According to the Preamble of the MPRA,

it is essential that municipalities exercise their power to impose rates within a statutory framework that not only enhances certainty, uniformity and simplicity across the nation, but also takes into account historical imbalances and the rates burden on the poor.

Seemingly in line with the principles of "certainty", "uniformity" and "simplicity", the MPRA provides for a single, uniform system of property rates for the whole country. In other words, when municipalities implemented the new law, they were compelled to determine the market value of all rateable property and levy rates accordingly.

After a period of more than ten years since the last municipalities implemented the MPRA in 2011, it is prudent to ask whether the important policy decision to opt for a single, uniform rating system for all municipalities was indeed the right decision. Although the metropolitan municipalities and many of the local municipalities managed to implement the MPRA, assess properties and levy rates accordingly, some local municipalities, especially those in rural settings, are struggling to administer the Act.

In this paper, I review the "one tax base for all municipalities" decision against Casanegra de Jantscher's often-quoted adage "tax policy is tax administration".6 Apart from the policy decision to opt for a "market value"-based tax, I focus on only one critical step in the administration of a market value-based rating system, namely the valuation of rateable property. In essence, I want to answer two questions:

(a) Is it appropriate to have market value as the only tax base for property rates in South Africa?

(b) If market value is not suitable for all municipalities, what alternative options could be considered?

I attempt to answer these questions firstly by providing an overview of the institutional context within which the MPRA must be administered, in other words I provide a brief overview of the municipal landscape in South Africa. I then review those provisions of the MPRA dealing with the determination of "market value" and the administration of the valuation process. This entails an overview of valuation service providers, monitoring and oversight, valuation cycles and the cost of valuation rolls. I do not consider other important issues pertaining specifically to tax administration, namely billing, payment, collection, enforcement and overall system management.

After a review of the rating landscape in South Africa, I provide a brief overview of international property tax policies and practices as these may be instructive as regards possible alternatives to the "one tax base for all municipalities". I conclude with final conclusions and recommendations.

2 South Africa's rating landscape

2.1 Institutional environment

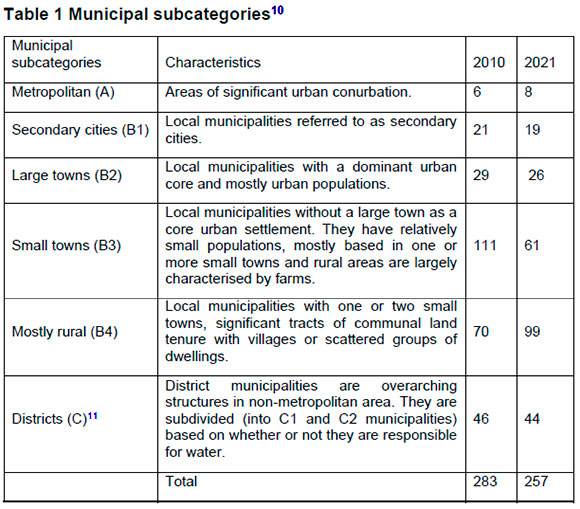

To give effect to section 155(1) of the 1996 Constitution, the Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998 (hereafter Municipal Structures Act) provides for three different categories of municipalities in the local sphere of government,7 namely metropolitan municipalities (Category A), local municipalities (Category B) and district municipalities (Category C).8 Since the 2016 local government elections, there are 257 municipalities: eight metropolitan, 205 local and 44 district municipalities. Metropolitan and local municipalities collectively cover the total surface area of South Africa, and all these municipalities typically consist of both urban and rural areas although the dominance of either urban or rural property differs widely across these municipalities as is apparent from Table 1.

Since the implementation of the Municipal Structures Act, various government reports refer to the municipal sub-categories identified in the Municipal Infrastructure Investment Framework (MIIF)9 - as indicated in Table 1.

As pointed out by Statistics South Africa (StatsSA),12

The local government landscape is dominated by eight large metropolitan municipalities who, as a group, contribute about 60% to total municipal income ... . As urban centres, these cities (together with smaller, secondary cities) are able to generate the bulk of their income from service charges and property rates. Due to their collective size, they have a large influence on the trend reflected in national aggregates . . The much smaller, rural municipalities are typically more dependent on grants and subsidies than they are on other income sources.

In the following sections the focus will be the 160 B3 and B4 local municipalities. It is assumed that the B1 and B2 local municipalities have or can solicit the skills to regularly value all rateable properties and have sufficient capacity to administer the MPRA more generally. It is noteworthy that section 81 (dealing with provincial monitoring and reporting) and section 83 (providing for ministerial regulations) of the MPRA explicitly allow for differentiation between different kinds of municipalities, in relation to "categories, types or budgetary size, or in any other manner".

2.2 Rating in terms of the MPRA

2.2.1 Tax base and taxpayer

Section 2(1) of the MPRA states that metropolitan and local municipalities may levy property rates. This seems to imply that district municipalities may not levy rates. Given the institutional environment of municipalities, all municipalities consist of urban and rural areas and therefore rates on property apply to urban and rural properties. With only a few exceptions, all properties that are not excluded from the tax base must be valued and reflected in a municipality's valuation roll.13 Owners of "property" are primarily responsible for rates.14 The tax is based on the rateable property's "market value" comprising land and buildings as one composite value.15Section 46(1) of the MPRA states:

Subject to any other applicable provisions of this Act, the market value of a property is the amount the property would have realised if sold on the date of valuation in the open market by a willing seller to a willing buyer.

Given that market value is the tax base, the next subsection focusses on the assessment of that base, in other words on the valuation of property.

222 Property valuation

2.2.2.1 Procurement of valuation service providers and oversight

According to section 33 of the MPRA, a municipality must designate a municipal valuer. One of the important functions of the municipal valuer is to prepare a valuation roll of all properties in the municipality.16 Only an individual who is appropriately qualified and registered as a "professional valuer" or a "professional associated valuer" with the South African Council for the Property Valuers' Profession (SACPVP) in terms of the Property Valuers Profession Act 47 of 2000 may be appointed as a municipal valuer.17

In the metropolitan municipalities and a few other large local municipalities, in-house valuers are used.18 For the vast majority of local municipalities, however, valuation services must be sourced from the private sector in terms of an open, competitive and transparent bidding process.19 The procurement of valuation services is one of the most problematic areas as regards the administration of property rates.20 Especially in the case of some local municipalities that are predominantly rural, councils may not know what to ask for in their tender specifications when they advertise for the appointment of a municipal valuer. They may also lack the skills to evaluate the tenders received and/or to evaluate the quality of the actual work done by the appointed municipal valuer. Although some of the amendments effected by the Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Amendment Act 29 of 2014 (and implemented on 1 July 2015) were aimed at addressing these problems,21 they generally added further responsibilities in an environment where municipalities are already struggling to cope with compliance.

Prior to the enactment of the 2014 amendments, there was only limited oversight in respect of the quality of valuation rolls and, by implication, the quality of the work performed by municipal valuers. Section 82 of the MPRA provides for the monitoring of the quality of valuation rolls by the minister responsible for local government - i.e., possible political oversight of a highly technical matter.22 This provision is inadequate. A much more holistic approach regarding the monitoring and oversight of municipal valuations is called for. Although a minister may appoint a technical committee to perform such a task and, in principle, perform such a task admirably, continuous technical oversight would have been a more appropriate route to take. In some jurisdictions23 this oversight is indeed the responsibility of a valuer general's office. In South Africa, however, the office of the valuer general, established under the Property Valuation Act 17 of 2014 is (by implication) precluded from performing this important task.

Further amendments implemented on 1 July 2015 provide for more oversight at the provincial level. The member of the executive (MEC) responsible for local government is tasked to monitor the determination of a date of valuation for a general valuation, the appointment of municipal valuers, and whether a project plan regarding the municipal general valuation has been submitted by the municipal manager. This amendment presupposes that the capacity exists in the offices of the provincial MECs to perform this task. In an attempt to address the issues with valuation and oversight, the MPRA now also saddles the municipality24 with additional tasks.

"(1) The Minister may monitor, and from time to time investigate and issue a public report on, the effectiveness, consistency, uniformity and application of municipal valuations for rates purposes.

(2) The investigation may include-

(a) studies of the ratio of valuations to sale prices; and

(b) other appropriate statistical measures to establish the accuracy of the valuations, including the relative treatment of higher value and lower value property.

(3) Investigations in terms of subsection (1) may be undertaken in respect of one or more or all municipalities." (Emphasis added.)

2.2.2.2 Valuation cycles and supplementary valuations

Until the MPRA was amended with effect from 1 July 2015, a valuation cycle was four years, with a possible extension of one further year under "exceptional circumstances" without any indication what these could be.25As from 1 July 2015, the valuation cycle for metropolitan municipalities is still four years but may be extended by the MEC for local government for a further two years.26 For local municipalities the valuation cycle has been extended to a maximum of five years with a possible two-year extension to seven years.27 The extension of the cycle to five years for local municipalities should have a definite positive impact on B3 and B4 municipalities, as it will reduce the cost of more regular comprehensive revaluations.

For various reasons, however, it may become necessary to undertake a new valuation during a valuation cycle. In such circumstances, a supplementary valuation roll must be compiled.28 The MPRA mandates that a supplementary valuation roll must be prepared at least once a year.29Although there may be relatively few properties requiring supplementary valuations in the case of B3 and B4 municipalities, the appointed municipal valuer must still prepare an annual supplementary roll. This comes at a cost.

2.2.2.3 Valuation capacity

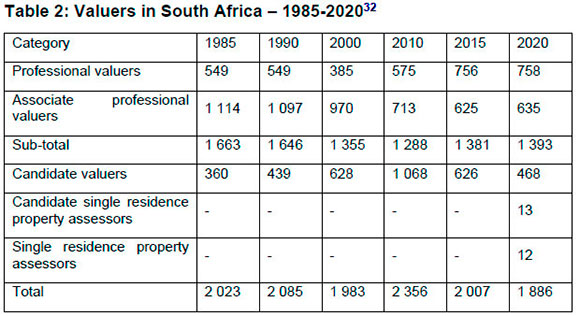

Although the valuation profession in South Africa is more than a century old and well-established,30 it remains an area of concern.31 Table 2 provides a description of the numbers of valuers in South Africa over a period of 35 years since 1985.

It is apparent that the numbers of professional valuers and associate professional valuers collectively have declined between 1985 and 2010 and increased again only from 2010. What is alarming is the decline in the numbers of candidate valuers. In 2020 there were still fewer qualified valuers who could do municipal valuations than 35 years ago in 1985. Furthermore, in the early 2000s apparently only about 20 to 25 per cent of the professional valuers actually undertook municipal valuations.33 There is no indication that the situation has improved by 2021.

2.2.2.4 Cost of valuation rolls

The costs of preparing and maintaining a valuation roll are substantial. These include the costs of preparing a first and thereafter regular general valuation rolls and of preparing annual supplementary valuation rolls and the costs pertaining to the valuation appeal board.34 Generally smaller municipalities located in rural areas cannot benefit from the principle of economies of scale. These municipalities typically have to source private sector valuers based in cities and these valuers will require travel and subsistence allowances over and above the actual cost of the property valuation task.

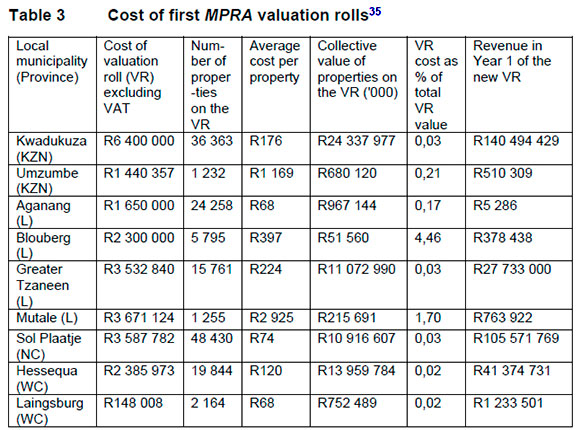

Table 3 analyses the costs of the first general valuation rolls prepared in terms of the MPRA in nine municipalities surveyed in 2011. Of course, a first valuation roll will be more expensive than successive general rolls, given the data requirements pertaining to a first roll. This is especially true for those local municipalities where property rates were not levied prior to the implementation of the MPRA.

Stating the cost as an average per property is admittedly a crude measure given the prevalence of different property use categories among these municipalities. What is interesting (if not worrying), however, is the significant range when overall cost is expressed in this manner - from only R68 to R2 925 per property. When the cost of the valuation roll is expressed as a percentage of the overall value of the valuation roll, it is noteworthy that especially Blouberg and the former Mutale local municipalities seem to be outliers.36

In Year 1 of the new valuation roll, Aganang Local Municipality raised only R5 286 in revenue from rates and R190 082 in Year 2. There was no realistic chance of recovering the R1.65 million cost of the valuation roll over the then possible five-year valuation cycle.37 This rather stark example points out the importance of doing a proper cost-benefit analysis in a municipality before deciding to implement a rating system and thereafter embarking on the appointment of a municipal valuer. After all, section 2 of the MPRA states that a "metropolitan or local municipality may levy a rate on property in its area" (emphasis added).

2.3 Preliminary conclusions

From the discussion in the previous subsections, it can be surmised that there are substantive problems and challenges with the "single tax base for all municipalities" arrangement. A value-based rating system is indeed not an appropriate system for all South Africa's local municipalities.

First, the institutional environment in many B3 and especially B4 municipalities is such that credible market values cannot be determined or can be determined only at exorbitant costs that leaves some of these municipalities with little or no revenue to provide municipal services and infrastructure and perform their constitutional responsibilities.38

Second, it can be argued that the principles of "certainty, uniformity and simplicity" cannot or should not be understood to imply a single, uniform rating system across all metropolitan and local municipalities. "Certainty" and "simplicity" are unlikely where the cost of obtaining and analysing market data to determine credible market values is prohibitive or in a municipality consisting predominantly of communal land and where market data are basically non-existent or extremely limited. The principle of "uniformity" should be carefully considered. To be fair in its application, the rating system must first and foremost be applied in a uniform manner in each municipality.39 There should also be uniformity across municipalities,40but only if they are similar in most respects. Surely, uniformity does not imply that vastly different municipalities (for example metropolitan municipalities versus B4 local municipalities) should of necessity apply a rating system that is uniform in all respects.

Third, a market value rating system is data intensive and therefore costly to implement and maintain. Several issues pertaining to skills and capacity in the valuation context have been identified in respect of municipal valuers and municipalities, and even in respect of the responsibilities given to MECs and the minister under the MPRA. If it were possible to apply the market value tax base in and across all South African municipalities, then a uniform system would be justified. In the light of the realities many B3 and B4 municipalities face, however, a market value system is seemingly inappropriate and therefore the insistence on a single system should be revisited.

3 International experience

To answer the second question, namely whether there are possible alternatives to the market value system, I briefly review recurrent property tax systems globally to gauge whether there are approaches or systems that may be more appropriate for South Africa's B3 and B4 municipalities.

3.1 Property tax base categories

An important policy decision when a property tax is designed and implemented is the decision about an appropriate tax base (or bases).41Traditionally there are three broad tax base categories to determine taxable amounts for recurrent property taxes, namely per-unit taxes, area-based taxes and value-based taxes.42 Countries or jurisdictions, however, also design and use what can best be called "hybrid" approaches43 that best suit their peculiar circumstances and that can mobilise revenue at minimal cost.

3.1.1 Per-unit taxes

The first and most rudimentary category is a per-unit tax or simple flat tax. It can be used where data on property sizes and values are too limited to be used as criteria for assessment. Given their inherent unfairness and lack of revenue buoyancy, per-unit taxes are rarely encountered in practice. A recent example, however, was the € 100 tax per dwelling in the Republic of Ireland.44

3.1.2 Area-based taxes

In the case of area-based property taxes, the taxable amount is determined using primarily the physical area (i.e., the square metres or hectares) of the property. A simple area-based tax that focusses only on size is uncommon.45 Most countries applying area-based taxation adjust the tax base by one or more factors, such as location and/or property use. This is done to approximate value, increase fairness and/or to introduce a measure of progressivity.46 Area-based approaches are typically encountered in developing47 and transitional48 countries where formal property markets may be less developed and the capacity and skills to determine property values limited.

3.1.3 Value-based taxes

In countries where property markets operate efficiently and the capacity and skills exist to determine credible property values on a significant scale and on a regular basis, capital or rental value approaches are generally the preferred tax base options.49 Both these approaches are extensively used globally.50 Value-based assessment uses methods and techniques that rely on market information to establish an estimate of how real property markets would value immovable property.51 In practice they are data intensive and difficult to administer.

In countries using value-based systems, different taxable object may be assessed and taxed. Most commonly encountered are systems taxing the collective value of land and buildings. There are, however, countries where land and buildings are taxed as separate taxable objects,52 where only land values are taxed53 and lastly where only the value of buildings is taxed.54

Most value-based systems would use techniques and methods (including mass valuation) to determine a discrete value for each taxable property. Nowadays the utilisation of computer-assisted mass appraisal (CAMA)55techniques and geographic information systems (GIS)56 is well-established especially in developed countries and jurisdictions, such as Canada, Hong Kong, the Netherlands and the United States.57 Given the paucity of quality property-related data and valuation and statistical analytical skills, CAMA is less commonly encountered in developing countries.58 The City of Cape Town, however, is a leading example of the effective use of CAMA to revalue almost 800 000 residential properties every three years.59

Any well-functioning value-based system requires quality data and continuous system maintenance to remain fair and revenue-buoyant. Achieving comprehensive tax base coverage and undertaking regular revaluations to ensure an equitable distribution of the tax burden are very often beyond the financial means, administrative capacity and professional skills levels in many developing countries.60 Even in some developed countries revaluations may take place irregularly, for example in Germany61and the United Kingdom.62

3.2 Tax base options

3.2.1 Single tax base versus multiple tax bases

A property tax with a single tax base is encountered in some countries. Apart from South Africa, provinces in Canada and most states in the United States levy a tax on capital value. Egypt and Uganda levy only one tax based on annual value.63

The laws in several countries provide for different tax bases or even different taxes, in some instances with reference to location, or whether land has been developed or not,64 or commonly with reference to use. For example, the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland have different taxes for residential and non-residential properties.65 In the State of Johor, Malaysia, municipalities can choose to levy rates on rental value or capital value with the vast majority using rental values.66 Shires in Western Australia differentiate based on use, applying a gross rental value system to urban properties and a system based on unimproved land values for rural properties.67

In Namibia, urban local authorities levy a recurrent property tax (also called "rates") in terms of the Local Authorities Act 23 of 1992. This Act provides for a range of tax base options.68 Section 73 of this Act states that local authorities can decide on a rate based on the value of: (1) the whole property; (2) of the land only; (3) only the improvement; or (4) the land and the value of improvements, but separately. Rather pragmatically, section 79 of this Act also allows for a rate on a basis other than valuation. This opens the door for small local authorities to implement a simple or calibrated area-based system.69

3.2.2 Alternative approaches

To address peculiar country or jurisdiction-specific challenges, various unique approaches have been developed and implemented across a range of countries or jurisdictions. Although there are various approaches,70 only three that may be informative in the South African context will now be discussed.

3.2.2.1 Value banding

In 1993, after the unprecedented tax revolt following the implementation of the community charge in 1989, Great Britain71 implemented the council tax. Value banding constitutes a unique valuation methodology. Rather than estimating the actual market value of each residential property in a jurisdiction, all residential properties were placed in one of eight predetermined value "bands" based on a judgment of the approximate value of the property. Each value band has its own tax rate and therefore every property in a specific band will have the same tax liability. Value banding has some advantages. First, it requires less property information and less valuation expertise. It is therefore less costly to implement and maintain than a market value system reliant on discrete values. Second, the absence of discrete values that can otherwise be challenged implies fewer objections and appeals from property owners.72 Third, the political role of assigning tax rates is somewhat divorced from the valuation exercise. Fourth is the reduced need to undertake frequent revaluations. It is only when values have moved beyond the upper (or lower) limits of the band that a revaluation should be considered.

Although it is currently used only in Great Britain (since 1993) and the Republic of Ireland (since 2013), this approach may indeed be suitable for African countries with functioning property markets but a paucity of valuation skills and capacity. As discussed below, it is indeed expressly referred to in the MPRA.

3.2.2.2 Points-based systems

In Malawi, section 64 of the Local Government Act of 1998 provides that an assembly (i.e., a local authority) may levy a fixed sum on the owners of buildings (with possible differentiation on the basis of use), or a fixed sum per unit area of land, or both such fixed sums.73 For all assessable land and buildings, however, section 65 states that a valuation roll must be prepared at least once every five years and land and buildings must be valued separately and then taxed on the basis of capital improved value. In a country with predominantly residential properties, a weak formal market and few qualified valuers,74 not surprisingly the valuation rolls of many assemblies are not comprehensive but severely outdated.

In 2013 the Mzuzu City Council75 designed and implemented a so-called "points-based" property tax system.76 It was done to boost stagnant revenues, address the issue of the poor base coverage (with only a fraction of rateable properties on the valuation roll) and the unfairness of a 20-year-old valuation roll that had been updated only once through a supplementary valuation.77 As Fish points out:78

The need for fairness, simplicity, cost efficiency and ease of use has driven a hybrid of the area-based method incorporating aspects of the market value-based approach.

Further challenges included poor physical addressing resulting in the weak billing, enforcement and sensitisation of and communication with ratepayers. With the points-based system, the city was able to assess many more previously unassessed properties, including properties in informal settlements where market data are unavailable.79 To deal with the increased number of properties, valuation was also made more efficient. A simple, cost-effective CAMA system, which city officials found easy to monitor, was introduced.80 With a points-based approach, points rather than price are assigned to the surface area of the building, while additional points are awarded for positive features or deducted for negative features of the property (such as location, construction type and materials and access to services).81

From 2013 to 2018, the city managed to increase its annual revenue from rates by 700 per cent.82 A disadvantage of the points-based method is that the process of deducting or adding points can been seen as somewhat opaque. The total points allocated and how they equate to value may not easily be recognised by the taxpayers as reasonable.83 Apart from significant increases in revenues, there are other advantages of the points-based valuation approach:84 First, the method is formulaic, which allows for automation, and a computer-aided system is administratively more efficient and cheaper than a traditional value-based approach. Second, extending the base coverage to new properties is not dependent on valuation by a professional valuer. Last, objections and appeals are limited to the factual description of the property. Although Mzuzu's reform seems to be a success, the points-based valuation method was not (and still is not) sanctioned by law. Section 68 of the Local Government Act only provides for market value-based assessment.85

In Sierra Leone, the Local Government Act of 2004 also dictates that property rates86 must be levied on the assessed annual value of assessed buildings.87 In the absence of a well-functioning market as well as the absence of valuation skills, Freetown and a number of other councils are experimenting with more pragmatic approaches.88 In Freetown, the city was "geo-mapped" and more than 67 000 new properties were added to the property database in 2020.89 Significant revenue gains were realised in 2021.

Unfortunately, in the cases of Mzuzu (Malawi) and Sierra Leone these "pilot study" points-based experiments were not sanctioned by law at the time when the projects commenced. This is still the case in Malawi, but apparently the new system in Freetown (Sierra Leone) is now lawful after an amendment of the law and the passing of a by-law.90

3.2.2.3 Self-assessment scheme in Bangalore, India

At the beginning of the 21st century, several cities in India replaced their annual rental value systems with adjusted area-based property tax systems to overcome issues with outdated valuation rolls, corruption and especially rent control.91

In 2000, Bangalore, the capital of Karnataka State, replaced its defunct annual value system with the "Self Assessment Scheme" (SAS) - which can be described as a hybrid between an area-based system and a value-based system.92 Under the SAS system, property owners were required to declare the prescribed physical characteristics of their property. In 2008, the SAS was revised with the introduction of "unit area values". Unit area values are determined with reference to the average rate of expected returns from a property per square foot per month, depending on the property's location and use. The city was classified into five value zones based on guidance values produced and published by the State's Department of Stamps and Registration. At least until 2011 these value zones were adjusted regularly. Over a three-year cycle the value increase must be at least 15 per cent, resulting in some buoyancy as regards an otherwise static tax base. For residential properties there is differentiation based on four categories of building materials and quality, as well as whether the property is owner-occupied or tenanted. For non-residential properties differentiation is done based on location, specific use categories and whether self-occupied or tenanted.93 It is a simplistic system allowing taxpayers to self-declare their property size, use and occupancy as well as to calculate the tax payable.

3.3 Preliminary conclusions

Quality data and proper data management are important features of any well-functioning value-based property tax system. This means that all the key elements of the system, such as property and ownership data, valuation rolls, as well as billing, payment and enforcement, must be maintained. Creating and maintaining databases, especially valuation rolls, come with a price tag.

Due to poor policy choices the property tax laws of some countries are not administrable in practice.94 Tax policy is, after all, tax administration. Surely, a malfunctioning value-based system that does not treat properties and property taxpayers equally before the law, is administratively cumbersome and underperforms regarding the revenue raised should be questioned.

A "one country one tax base" approach for the recurrent property tax may be too rigid and simplistic. Although market value-based systems function well in Canada and the United States, for example, some developed countries or jurisdictions do not subscribe to this approach - for example Great Britain, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.95 The laws in many countries allow for a variety of tax bases and, concomitantly, local choice on the most appropriate system to use.96

Although still value-based, a simple value banding approach for residential properties can generate significant revenue at minimal cost. However, non-value approaches designed and implemented to address the challenges presented by traditional value-based systems such as the points-based system or self-assessment schemes can also work. To be successful these simplistic and pragmatic approaches require political and legislative support.97

4 Conclusions and recommendation

In 2002, a few years before the MPRA was implemented, Solomon et al stated:98

It is worthwhile, therefore, for policy makers in South Africa to exercise their minds to find a version of the property tax-based on the valuation of existing, clearly defined rural rights-rather than the blind application of an urban tax with the unintended consequences of threatening a political institution which, despite its awkward fit with the current democratic rhetoric, has served rural South Africans well through some dark times.

Although their arguments deal with the political economy and nature of communal land rights, the sentiment expressed can be extended to the administrative feasibility of the current South African rating system. Some of the local municipalities in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo provinces consist almost exclusively of communal land.99

Interestingly, section 45(3) of the MPRA already provides rural municipalities with the option of a value-banding system. It states:

(a) If the available market-related data of any category of rateable property is not sufficient for the proper application of subsections (1) and (2), such property may be valued in accordance with any mass valuation system or technique approved by the municipality concerned, after having considered any recommendations of its municipal valuer and as may be appropriate in the circumstances.

(b) A mass valuation system or technique that may be approved by a municipality in terms of paragraph (a) includes a valuation system or technique based on predetermined bands of property values and the designation of properties to one of those bands on the basis of minimal market-related data.

Section 45(3) requires a recommendation from the municipal valuer and subsequent approval by the municipal council. To date, this section has not been used. It is, after all, still a value-based system. The current cohort of professional valuers and professional candidate valuers does not have the capacity to undertake regular general valuations and annual supplementary valuations for the metropolitan and all local municipalities across South Africa. Furthermore, the costs pertaining to the preparation and maintenance of a comprehensive valuation roll, even if it were to remain valid for seven years, are too high for many rural local municipalities with small property rates bases.

It is evident in section 2 above that the market value approach is not serving all municipalities in South Africa equally well. The differences between metropolitan municipalities and other large predominantly urban B1 and B2 local municipalities on the one hand and, B3 and B4 local municipalities on the other, cannot be ignored. A cost-benefit analysis of alternative approaches to market value property rating should be undertaken.

The South African government should revisit the current "one size fits all" approach as regards the tax base for property rates.100 The current market value system is simply not appropriate for all local municipalities. Furthermore, pragmatic approaches applied in other countries or jurisdictions suggest that there are solutions to the problem. The MPRA already allows for differentiation between different types of municipalities. Surely this can be extended to the most important component of the rating system, the tax base. An adjusted area-based system along the lines of a point-based or self-assessment system may be a more pragmatic and cost-effective approach especially for those B3 and B4 (i.e., rural) local municipalities with extensive tracts of communal land.

Bibliography

Literature

Aki-Sawyerr Y "Property Tax Reform in Freetown, Sierra Leone" Unpublished contribution at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and African Tax Institute on Property Taxation and Land Value Capture in Africa (5-7 May 2021 Virtual Conference) [ Links ]

Bahl R and Bird RM Fiscal Decentralization and Local Finance in Developing Countries (Edward Elgar Cheltenham 2018) [ Links ]

Bell ME "Property Tax Structure and Practice" in Bell ME and Bowman JH (eds) Property Taxes in South Africa: Challenges in the Post-Apartheid Era (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2002) 59-75 [ Links ]

Bell ME and Bowman JH "Adapting the South African Property Tax to Changed Circumstances" in Bell ME and Bowman JH (eds) Property Taxes in South Africa: Challenges in the Post-Apartheid Era (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2002) 3-22 [ Links ]

Bowman JH "Current Property Tax Laws" in Bell ME and Bowman JH (eds) Property Taxes in South Africa: Challenges in the Post-Apartheid Era (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2002) 45-56 [ Links ]

Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike Property Tax Self Assessment Scheme Handbook - Block Period 2008-09 to 2010-11 (Government Press Bangalore 2009) [ Links ]

Brzeski J, Romänovä A and Franzsen R The Evolution of Property Taxes in Post-Socialist Countries in Central and Eastern Europe - ATI Working Paper WP-19-01 (University of Pretoria Pretoria 2019) [ Links ]

Casanegra de Jantscher M "Administering the VAT" in Gillis M, Shoup CS and Sicat GP (eds) Value Added Taxation in Developing Countries (World Bank Washington DC 1990) 171-190 [ Links ]

Cloete CE "Training Valuers in South Africa - The Future" Unpublished contribution delivered at the International Property Tax Institute 4th Mass Appraisal Valuation Symposium (25-26 March 2009 Pretoria) [ Links ]

Cloete JJN South African Local Government and Administration (Van Schaik Hatfield 1989) [ Links ]

Daud et al 2013 Journal of Property Tax Assessment and Administration Daud DZ et al "Property Tax in Malaysia and South Africa: A Question of Assessment Capacity and Quality Assurance" 2013 Journal of Property Tax Assessment and Administration 5-18 [ Links ]

Fish P Training Manual for Implementing Property Tax Reform with a Points-Based Valuation - ICTD African Tax Administration Paper 2 (International Centre for Tax and Development Brighton 2018) [ Links ]

Franzsen RCD "Property Tax: Alive and Well and Levied in South Africa?" 1996 SA Merc LJ 348-365 [ Links ]

Franzsen R "Education of Valuers in South Africa" Unpublished contribution at the University of British Columbia Vancouver Canada 6th Mass Appraisal Valuation Symposium, International Property Tax Institute (7-8 October 2011 Vancouver) [ Links ]

Franzsen R "International Experience" in Dye R and England R (eds) Land Value Taxation (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2009) 27-47 [ Links ]

Franzsen R "South Africa" in Franzsen R and McCluskey W (eds) Property Tax in Africa: Status, Challenges and Prospects (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2017) 376-396 [ Links ]

Franzsen RCD "The Taxation of Rural Land" in Bell ME and Bowman JH (eds) Property Taxes in South Africa: Challenges in the Post-Apartheid Era (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2002) 215-231 [ Links ]

Franzsen RCD and McCluskey WJ "Some Policy Issues Regarding the Local Government: Property Rates Bill" 2000 SA Merc LJ 209-223 [ Links ]

Franzsen R and McCluskey W "Introduction" in Franzsen R and McCluskey W (eds) Property Tax in Africa: Status, Challenges and Prospects (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2017) 3-28 [ Links ]

Franzsen R and McCluskey W "Namibia" in Franzsen R and McCluskey W (eds) Property Tax in Africa: Status, Challenges and Prospects (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2017) 313-328 [ Links ]

Franzsen RCD and McCluskey WJ "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 41-68 [ Links ]

Franzsen R and Welgemoed W "Submission on Proposed Amendments to the Municipal Property Rates Act (MPRA)" Unpublished report for the South African Local Government Association (June 2011) [ Links ]

Franzsen R, Ali-Nakyea A and Tommy A "Simplifying Recurrent Property Taxes in Africa" in Evans CC, Franzsen R and Stack E (eds) Tax Simplification: An African Perspective (Pretoria University Law Press Pretoria 2019) 178-203 [ Links ]

Jibao S "Sierra Leone" in Franzsen R and McCluskey W (eds) Property Tax in Africa: Status, Challenges and Prospects (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2017) 364-375 [ Links ]

Kitchen H "Property Tax: A Situation Analysis and Overview" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 1 -40 [ Links ]

McCluskey WJ et al "Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal and the Property Tax" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 307-338 [ Links ]

McCluskey WJ and Franzsen RCD "Non-Market Value and Hybrid Approaches to Property Taxation" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 287-305 [ Links ]

McCluskey WJ and Franzsen RCD "Property Taxes in Metropolitan Cities" in Bahl R, Linn J and Wetzel D (eds) Metropolitan Government Finance in Developing Countries (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2013) 159-181 [ Links ]

McCluskey W, Franzsen R and Bahl R "Challenges, Prospects and Recommendations" in Franzsen R and McCluskey W (eds) Property Tax in Africa: Status, Challenges and Prospects (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2017) 551-592 [ Links ]

McCluskey W, Franzsen R and Bahl R "Policy and Practice" in Franzsen R and McCluskey W (eds) Property Tax in Africa: Status, Challenges and Prospects (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2017) 29-104 [ Links ]

McIlhatton D et al "Geographic Information Systems and the Importance of Location: Integrating Property and Place for Better Informed Decision Making" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 339-357 [ Links ]

Ministry of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development The White Paper on Local Government (Ministry of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development Pretoria 1998) [ Links ]

Plimmer F "Legal Issues in Property Tax Administration" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 187-205 [ Links ]

Prichard W, Fish P and Zebong N Valuation for Property Tax Purposes: ICTD Summary Brief 10 (International Centre for Tax and Development, Institute of Development Studies Brighton 2017) [ Links ]

Rao UAV "Is Area-Based Assessment an Alternative, an Intermediate Step, or an Impediment to Value-Based Taxation in India?" in Bahl RW, Martinez-Vazquez J and Youngman JM (eds) Making the Property Tax Work (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2008) 241 -267 [ Links ]

Rosengard JK "Principles of Property Tax Reform" in McCluskey WJ, Cornia GC and Walters LC (eds) A Primer on Property Tax: Administration and Policy (Wiley-Blackwell West Sussex 2013) 173-186 [ Links ]

Salm M Property Tax in BRICS Megacities (Springer International Cham 2017) [ Links ]

Solomon D et al "Tribal Land and the Property Tax" in Bell ME and Bowman JH (eds) Property Taxes in South Africa: Challenges in the Post-Apartheid Era (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Cambridge MA 2002) 195-213 [ Links ]

Zybrands A "Commentary on the Municipal Property Rates Bill" Unpublished contribution to the Department of Constitutional Development's Property Rates Bill Workshop (7-8 April 2003 Benoni) [ Links ]

Legislation

South Africa

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 200 of 1993

Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act 56 of 2003

Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004

Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Amendment Act 29 of 2014

Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998

Local Government Transition Act 209 of 1993

Property Valuation Act 17 of 2014

Property Valuers Profession Act 47 of 2000

Other countries

Local Authorities Act 23 of 1992 (Namibia)

Local Government Act of 1998 (Malawi)

Local Government Act of 2004 (Sierra Leone)

Internet sources

Chirambo A and McCluskey R 2019 Property Tax Reform Increases Municipal Revenue in Mzuzu, Malawi https://www.ictd.ac/blog/property-tax-reform-increases-municipal-revenue-in-mzuzu-malawi/ accessed 21 January 2022 [ Links ]

Financial and Fiscal Commission 2016 Submission for the Division of Revenue 2017/2018 (27 May 2016) https://www.ffc.co.za/_files/ugd/b8806a_36a9ec3c70b94020a12942a6413f737b.pdf accessed 21 January 2022 [ Links ]

National Treasury 2011 Local Government Budgets and Expenditure Review http://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/igfr/2011/lg/default.aspx accessed 3 January 2022 [ Links ]

StatsSA 2021 The Peaks and Troughs of Municipal Income http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14250 accessed 15 February 2022 [ Links ]

StatsSA 2021 Municipal Dependence on National Government Financing http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14537 accessed 15 February 2022 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

CAMA computer-assisted mass appraisal

CoGTA Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs

GIS geographic information systems

KZN KwaZulu-Natal

L Limpopo Province

MEC Member of the Executive Council

MIIF Municipal Infrastructure Investment Framework

MPRA Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004

NC Northern Cape

SA Merc LJ South African Mercantile Law Journal

SACPVP South African Council for the Property Valuers Profession

SAS Self Assessment Scheme

WC Western Cape

Date Submitted: 16 March 2022

Date Revised: 12 May 2022

Date Accepted: 02 June 2022

Date Published: 27 October 2022

Guest Editor: Dr Karl Marxen

Journal Editor: Prof C Rautenbach

* Riel Franzsen. BLC LLB MA (UP) LLD (US). South African Research Chair in Tax Policy and Governance, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: riel.franzsen@up.ac.za. ORCiD: 0000-0003-4545-2775. The author wishes to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments.

1 Cloete South African Local Government and Administration 131-132.

2 Franzsen 1996 SA Merc LJ 352-353. See also Bowman "Current Property Tax Laws" 49-50.

3 Bell "Property Tax Structure and Practice" 64-65.

4 Bell and Bowman "Adapting the South African Property Tax" 6-7; Franzsen and McCluskey 2000 SA Merc LJ 210. At local government level there has been significant institutional reform. The reform was set in motion by the interim Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 200 of 1993 and the Local Government Transition Act 209 of 1993 and gained momentum after the White Paper on Local Government was tabled in 1998. The new constitutional and institutional dispensation necessitated an overhaul and eventual replacement of the various provincial rating systems - see Franzsen 1996 SA Merc LJ 353-354; Franzsen and McCluskey 2000 SA Merc LJ 209-211.

5 Although the Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004 (the MPRA) was promulgated on 2 July 2005, it could become operative only on the first day of the municipal fiscal year (i.e., on 1 July) and only once a municipality had adopted its municipal property rates policy (s 3) and had prepared a first valuation roll in terms of the Act. S 89 (repealed in 2014 as it was no longer required) stated that municipalities were required to bring their valuation records and administration up to date within a transitional period of four years (1 July 2006 to 1 July 2009), which was later extended to six years (i.e., until 1 July 2011). Many municipalities implemented their new valuation rolls undertaken in terms of the MPRA in 2008 or 2009 - see Franzsen "South Africa" 381.

6 Casanegra de Jantscher "Administering the VAT" 179.

7 See s 40 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution) regarding the three spheres of government.

8 Section 155(2) of the Constitution states that national legislation "must define the different types of municipality that may be established within each category". Part 2 (ss 7-11) of the Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998 (the Municipal Structures Act) provides the details regarding types of municipalities and these relate to the way municipalities are governed.

9 This framework was developed by the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (CoGTA) and the Development Bank of South Africa - see StatsSA 2021 http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14537.

10 Adapted from the 2007 Municipal Infrastructure Investment Framework (MIIF).

11 As district municipalities do not levy rates (as implied by s 2 of the MPRA), the distinction between C1 and C2 district municipalities is not relevant.

12 See StatsSA 2021 http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14250. When data from the Financial Census of Municipalities Report are applied to the MIIF categories these data show that in 2020 metropolitan councils generated 81% revenue from own income, compared with only 28% recorded by B4 municipalities - see StatsSA 2021 http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14537.

13 Section 7 read with s 30 of the MPRA. S 82A(e) furthermore states that municipalities must submit reports to the minister (responsible for local government) on the "total revenue foregone in respect of any properties subject to partial exclusions, exemptions, rebates and reductions".

14 Section 24 of the MPRA.

15 See the definitions of "property" and "market value" (s 1) read with s 45 and s 46 of the MPRA.

16 See s 34 of the MPRA.

17 See s 39 of the MPRA read with s 19(1) of the Property Valuers Profession Act 47 of 2000. This was also the situation under the former provincial laws - see Franzsen and Welgemoed "Submission on Proposed Amendments to the Municipal Property Rates Act (MPRA)" 6.

18 These municipalities have valuation departments or divisions with qualified valuers as employees. Some of these municipalities, e.g., Cape Town and Ekurhuleni, also utilise the services of private sector valuers when they undertake their general revaluations - Franzsen and Welgemoed "Submission on Proposed Amendments" 7. They state that some municipalities also make extensive use of data collectors to collect property-related data needed to prepare valuation rolls. This is provided for in s 36 of the MPRA.

19 Section 33 read with ch 11 of the Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act 56 of 2003.

20 Franzsen and Welgemoed "Submission on Proposed Amendments" 8; Financial and Fiscal Commission 2016 https://www.ffc.co.za/_files/ugd/b8806a_36a9ec3c70b94020a12942a6413f737b.pdf 128.

21 See amendments to ss 81 and 83 and new sections, namely ss 82A and 82B of the MPRA.

22 Section 82 of the MPRA provides:

23 E.g., Canada, New Zealand and Australia - see Franzsen and McCluskey 2000 SA Merc LJ 220-221.

24 Sections 81(1B) and 82A of the MPRA.

25 See s 32(2) of the MPRA.

26 Section 32(2)(a)(i) of the MPRA.

27 Section 32(2)(a)(ii) of the MPRA.

28 Section 78(1) of the MPRA.

29 Sections 77 and 78(6) of the MPRA. Supplementary valuations must reflect the value of the property as if valued at the date of valuation determined for the last (i.e., current) general valuation.

30 The South African Institute of Valuers was established in 1909. Whereas the South African Council for the Property Valuers Profession (the SACPVP) regulates the registration of valuers, this institute is a self-regulatory entity dealing with valuation standards and ethical codes for the profession.

31 Cloete "Training Valuers in South Africa"; Franzsen "Education of Valuers in South Africa".

32 Data provided by the SACPVP.

33 Franzsen "South Africa" 389-390 (referencing Zybrands "Commentary on the Municipal Property Rates Bill"). See s 19(1) of the Property Valuers Profession Act 47 of 2000.

34 Section 61(3) of the MPRA.

35 Adapted from a table prepared by Franzsen and Welgemoed "Submission on Proposed Amendments" 34. It is important to note that Aganang Local Municipality was disestablished on 3 August 2016 and its municipal area merged into Blouberg Local Municipality, Molemole Local Municipality and Polokwane Local Municipality. Mutale Local Municipality was also disestablished and merged with Thulamela and Musina Local Municipalities.

36 Admittedly, a sample of only nine municipalities is not statistically relevant.

37 Franzsen and Welgemoed "Submission on Proposed Amendments" 37. Four municipalities in the sample of nine could not recover the cost of the first general valuation roll from the revenue in the first year of implementation of the relevant roll.

38 See ch 7 of the 1996 Constitution.

39 Bell and Bowman "Adapting the South African Property Tax" 11; Kitchen "Property Tax" 7. The principles of horizontal and vertical equity are clear. Those that are alike should be treated the same and those that are not alike should be treated differently. In a property tax context, all properties should be assessed in the same manner and demands for payment should be the same for everyone in a similar situation - see Bell and Bowman "Adapting the South African Property Tax" 13; Plimmer "Legal Issues in Property Tax Administration" 199.

40 Bell and Bowman "Adapting the South African Property Tax" 11. This is generally required for the purposes of addressing disparities in fiscal capacity across municipalities. In the South African context, where categories A, B and C municipalities and sub-categories (e.g., B1, B2, B3 and B4) are clearly defined, vertical differentiation and dissimilar treatment of subcategories can be applied for equalisation purposes.

41 Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 41; Rosengard "Principles of Property Tax Reform" 178. See also Prichard, Fish and Zebong Valuation for Property Tax Purposes 1-2.

42 See Franzsen and McCluskey "Introduction" 6.

43 McCluskey and Franzsen "Non-Market Value and Hybrid Approaches" 287-305.

44 The residential property tax in Ireland was abolished in 1978 but reintroduced in 2012 in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis. After more than 30 years without a tax on residential property, the absence of sufficient data on property size and value made the immediate implementation of an area-based or value-based tax impossible. This temporary tax was replaced in 2013 by a value-based tax, using value banding - Franzsen and McCluskey "Introduction" 7. In Malawi, s 64 of the Local Government Act of 1998 also allows for a per-unit tax.

45 Franzsen and McCluskey "Introduction" 7.

46 McCluskey and Franzsen "Non-Market Value and Hybrid Approaches" 287-293; Franzsen and McCluskey "Introduction" 7. See also Prichard, Fish and Zebong Valuation for Property Tax Purposes 3.

47 E.g., Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan - Franzsen and McCluskey "Introduction" 7.

48 E.g., the Czech Republic and Slovakia - Brzeski, Romanova and Franzsen The Evolution of Property Taxes 11-12.

49 Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 45-54; Franzsen and McCluskey "Introduction" 6, 8-11.

50 Examples of countries using capital value as tax base include Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, United States, and Zambia (see Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 46-54), whereas countries or jurisdictions using annual rental values include Egypt, France, Hong Kong (China), Singapore, Uganda, and the United Kingdom (see Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 45-46). In some countries, for example Australia, Malaysia and New Zealand, municipal councils can choose to apply either a capital or a rental value system.

51 In Canada and the United States, the term "real estate" is used for immovable property.

52 E.g., Namibia - see Franzsen and McCluskey "Namibia" 323. This system is used in the capital city, Windhoek - see Franzsen and McCluskey "Namibia" 325. In Botswana and Malawi, land and buildings are assessed separately but taxed collectively.

53 Countries taxing only land values include Estonia, Fiji, Jamaica and Kenya - see Franzsen "International Experience" 28, 42-45. In some countries "land value" or "site value" systems are provided as an option for all properties (Australia, Namibia and New Zealand), or certain property use categories (Western Australia) - see Franzsen "International Experience" 30-38.

54 Examples of countries taxing only buildings (and other improvements) include Egypt and Sierra Leone, where annual rental value is used, and Ghana and Tanzania, where capital value is used.

55 For a detailed discussion of computer-assisted mass appraisal (CAMA), see McCluskey et al "Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal" 307-338.

56 For a detailed discussion of geographic information systems (GIS) in the context of property taxation, see McIlhatton et al "Geographic Information Systems" 339-357.

57 Bahl and Bird Fiscal Decentralization 253.

58 McCluskey, Franzsen and Bahl "Policy and Practice" 82; Bahl and Bird Fiscal Decentralization 253.

59 Franzsen "South Africa" 386.

60 Daud et al 2013 Journal of Property Tax Assessment and Administration 14.

61 Salm Property Tax in BRICS Megacities v. The last formal revaluations were undertaken in 1964 in former West Germany and 1935 in former East Germany.

62 Valuations (and banding) for the council tax applicable in England, Wales and Scotland were undertaken in 1991 with no revaluation or re-banding undertaken thereafter.

63 See Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 45.

64 For example, Cote d'Ivoire - see Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 43.

65 In the United Kingdom the uniform business rate levied on non-residential properties is based on rental values whereas the council tax in Great Britain and property rates in Northern Ireland levied in respect of residential properties are based on capital values.

66 See Daud et al 2013 Journal of Property Tax Assessment and Administration 10.

67 Franzsen and McCluskey "Value-Based Approaches to Property Taxation" 43.

68 See s 73 of the Local Authorities Act 23 of 1992; and Franzsen and McCluskey "Namibia" 322-323.

69 Franzsen and McCluskey "Namibia" 326.

70 For example, some cities in Tanzania, such as Arusha, utilise a so-called flat-rate system - see McCluskey, Franzsen and Bahl "Challenges, Prospects, and Recommendations" 577.

71 I.e., England, Scotland and Wales. Northern Ireland never introduced a value-banding system. The council tax was a "quick fix" solution. Political and time constraints made it impossible to accurately determine discrete values for every residential property. Thus, a pragmatic approach was devised, called "value banding". The Republic of Ireland introduced a banding system for residential property in 2013 based on nineteen value bands.

72 McCluskey, Franzsen and Bahl "Challenges, Prospects and Recommendations" 578.

73 The fixed sum system is supposed to be used in areas not yet designated as ratable areas, or areas that are for whatever reason not assessable.

74 There are fewer than 40 qualified valuers registered with the Board of Surveyors in Malawi, but the Mzuzu University and the Blantyre Polytechnic offer a four-year degree programme for valuers and the University of Lilongwe offers a programme for valuation technicians.

75 Mzuzu is the 3rd largest city in Malawi.

76 The Revenue Mobilisation Programme (REMOP) was done with the support of the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and under the guidance and supervision of an international consultant, Paul Fish.

77 These base coverage and valuation issues were attributed to high valuation fees.

78 Fish Training Manual for Implementing Property Tax Reform 14.

79 As a first step, attention was given to property discovery, with 30 000 new properties added to the 10 000 on the defunct valuation roll - see Chirambo and McCluskey 2019 https://www.ictd.ac/blog/property-tax-reform-increases-municipal-revenue-in-mzuzu-malawi/.

80 Chirambo and McCluskey 2019 https://www.ictd.ac/blog/property-tax-reform-increases-municipal-revenue-in-mzuzu-malawi/.

81 Fish Training Manual for Implementing Property Tax Reform 14-15. Fish points out that the city undertook an exercise to compare market-based rates with those derived from the points-based method. Fifty properties of various types were valued and the rates that would have been paid were compared to the rates determined under the points-based system. The results demonstrated that the points-based rates closely mimicked the market-based rates.

82 See Chirambo and McCluskey 2019 https://www.ictd.ac/blog/property-tax-reform-increases-municipal-revenue-in-mzuzu-malawi/.

83 Fish Training Manual for Implementing Property Tax Reform 15. As Fish points out, taxpayers can, however, compare the points-based outcome and tax bill to other similar properties nearby with reference to the principle that properties of equal "value" should be taxed the same.

84 Fish Training Manual for Implementing Property Tax Reform 15.

85 Section 67 of the Local Government Act of 1998 requires valuers responsible for valuation rolls to be registered with the Board of Surveyors Institute of Malawi. Mzuzu used an international consultant who was not locally registered.

86 Referred to as the city rate for Freetown and the town rate for other cities and towns - Jibao "Sierra Leone" 370.

87 See s 69 read with s 75(1) of the Local Government Act of 2004. For a discussion of the rating system in Sierra Leone, see Jibao "Sierra Leone" 368-374.

88 In respect of Malawi, see Fish Training Manual for Implementing Property Tax Reform 14-18 and in respect of Sierra Leone, see Franzsen, Ali-Nakyea and Tommy "Simplifying Recurrent Property Taxes" 199.

89 Aki-Sawyerr "Property Tax Reform in Freetown".

90 Aki-Sawyerr "Property Tax Reform in Freetown". Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr is the mayor of Freetown.

91 E.g., Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Delhi, Hyderabad and Pune. Ahmedabad introduced a "calibrated area-based" system. To approximate value, properties were "calibrated" with reference to location, building size and age, usage and occupancy. As no provision was made for amending these factors (multipliers), the tax base was not buoyant, and revenues started decreasing over time. The only growth was the addition of new properties - not sufficient to maintain or increase the revenue stream - see Rao "Is Area-Based Assessment an Alternative?" 249-252. See also McCluskey and Franzsen "Property Taxes in Metropolitan Cities" 162.

92 The process was transparent and the public relations campaign well-managed. The mayor had the backing of opposition parties, the media and the majority of taxpayers - see Rao "Is Area-Based Assessment an Alternative?" 257. It is noteworthy that when a capital value system was introduced in Karnataka State in 2005, Bangalore retained the Self Assessment Scheme (the SAS).

93 For a detailed discussion of this self-assessment system, see Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike Property Tax Self Assessment Scheme Handbook, published by the city council. Significant increases in revenue were experienced between 2000 and 2011. For an overview of a similar unit-area approach applied in New Delhi, see McCluskey, Franzsen and Bahl "Challenges, Prospects, and Recommendations" 575-576.

94 This is the case in many African countries. See McCluskey, Franzsen and Bahl "Challenges, Prospects and Recommendations" 570-572.

95 McCluskey, Franzsen and Bahl "Challenges, Prospects and Recommendations" 570.

96 E.g., Namibia. This is also the case in Eswatini, Kenya and Zimbabwe.

97 Although one can sympathise with the frustrations of revenue-starved local authorities, experimenting with alternative, pragmatic approaches not sanctioned by law, as in Malawi and Sierra Leone, should be avoided.

98 Solomon et al "Tribal Land and the Property Tax" 211. See also Franzsen "Taxation of Rural Land" 224-225.

99 Financial and Fiscal Commission 2016 https://www.ffc.co.za/_files/ugd/b8806a_36a9ec3c70b94020a12942a6413f737b.pdf 92. Many of the properties in these rural municipalities are either excluded from the tax base, or exempted, or fall below a rateable value threshold (s 17(1)(h) of the MPRA) with the result that the potential revenue from property rates is limited. Furthermore, tax administration (i.e., billing, collection and enforcement) present additional challenges.

100 This is indirectly proposed in National Treasury 2011 http://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/igfr/2011/lg/default.aspx 208.