Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.22 n.1 Potchefstroom 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a7593

SPECIAL EDITION: DETERMINING THE CONTENT OF INDIGENOUS LAW

Orocowewin Notcimik Itatcihowin: The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw Code of Practice and the Issues Involved in Its Writing

B Éthier*; C Coocoo**; G Ottawa***

Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Canada. Benoit.ethier@uqat.ca; ccoocoo@atikamekwsipi.ca; gottawa@atikamekwsipi.ca

ABSTRACT

The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw Nation has for several years been developing a code of practice (orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin) to regulate hunting, fishing and plant harvesting activities in Nitaskinan, its ancestral territory. The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice is a collective project that sets out to put its territorial regulations in writing. The project's objective is threefold: to ensure the transmission of territorial knowledge and of rules relating to forest activities; to adapt these rules, passed on by ancestors, to the contemporary context; and to have them recognised by non-natives and the governments of other nations, including the governments of Canada and Quebec. This article presents some of the issues related to the process of writing and coding orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin, the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice; in particular, the importance of the oral tradition as a means of transmitting knowledge is emphasised. In our language, we say "atisokana ki atisokan" - we are infused and transformed by the narratives transmitted orally. This mode of transmission is politically, philosophically and emotionally significant. It is a unique way for us to let the heart speak, through direct contact, without interference.

Keywords: Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin; Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice; customary law; territorial knowledge; Atikamekw Nehirowisiw; First Nations; Canada.

1 Introduction

An analysis of the impact of writing indigenous customary law was undertaken in the 1980s by anthropologists and lawyers, particularly in African contexts1. In the African context, the process of writing indigenous customary law was carried out mainly by the English colonial elite from the 1930s onwards. This process was intended to ensure some level of recognition of indigenous customary law in accordance with the "indirect rule" approach2 and to provide a framework for indigenous customary law. However, determining finite rules for indigenous customary law, which is intended to be more informal and flexible, has proved, according to Chanock, to promote a form of colonial continuity and inter-tribal strife: "[T]he courts were to apply the customary law of each tribe, strengthening tribal divisions and drawing sharper lines between what had been fluid and conflicting spheres of local law".3

As they formalised customary law, British officers were careful to select the normative and moral aspects they considered fair and acceptable, neglecting those aspects that contravened their values and normative principles.4 The formalisation and essentialisation of customary law as defined - in terms of substance rather than process - by the colonial elite, and as recognised by them, did not allow indigenous normative orders to adjust to the new contingencies arising from colonialism, modernity and the new forms of market economy.5

As the above-mentioned studies in African contexts demonstrate, the processes of codification, writing and enforcement of indigenous customary law by the colonial elite can exacerbate rather than reduce social conflicts and inequalities. That is why we, as a people, have decided to take charge in our own way of this project to write orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin, our territorial regulations, to ensure compliance. To be valid in the eyes of our people, orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin must be the result of a collective and consensual process (orocowewin). Thus, when we talk about orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin, we are talking about our own societal project rather than a project and an approach imposed by colonial governments. We have already suffered enough from their policies.

This article6 presents some of the issues related to the process of writing and coding orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin, the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice.7 This project consists of writing down our territorial regulations related to hunting, fishing and plant harvesting practices. The code of practice aims to maintain harmonious relationships with Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok families and with notcimik, our place of origin and belonging.8Our customary law applies to the different Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok generations. Our daily and contemporary activities are carried out with due respect for our ancestors and great-grandchildren, who will also feed and live (nehirowisiw opimatisiwin) within notcimik.

Work on the development of the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice is ongoing. We have been working on this document for several years (since the late 1990s) but it is not yet complete. We have spent a considerable time and energy documenting animal-related knowledge, such as bear, moose and beaver knowledge, but we have not yet documented it all. We need to further document knowledge about small game such as the hare, the partridge and migratory birds. As we point out later in this text, the code of practice is based on our knowledge of the fauna and flora. For several years now, we have been conducting a consultation process with elders and territorial leaders in the three communities to gather territorial knowledge and develop our own code of practice.

As a society and as a nation, we have made the decision to work on the code of practice in our own way, in a spirit of consultation and consensus. The approach we propose is therefore one that aims to foster and put into practice our own visions of politics, our own ways of life and our own aspirations.

In this text, we discuss in particular our approach, but also the different challenges we must overcome during the process of writing and codifying our customary law and territorial knowledge. In particular, the importance of the oral tradition as a means of transmitting knowledge is emphasised. This mode of transmission is politically, philosophically and emotionally significant. It is a unique way for us to let the heart speak, through direct contact, without interference.

First, we explain our situation as a people within Canada, a country whose successive governments imposed their own political and legal systems on the first occupants of the territory, often ignoring or denying our own political and legal knowledge and practices. However, we remain hopeful that we will one day be able to ensure that our own values, principles and practices are known and acknowledged. This is an ambitious undertaking, but it has been underway for centuries. This is an ongoing process, and, through this text, we wish to contribute to this project of "reconciliation" and sharing.

2 The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw nation - a brief history

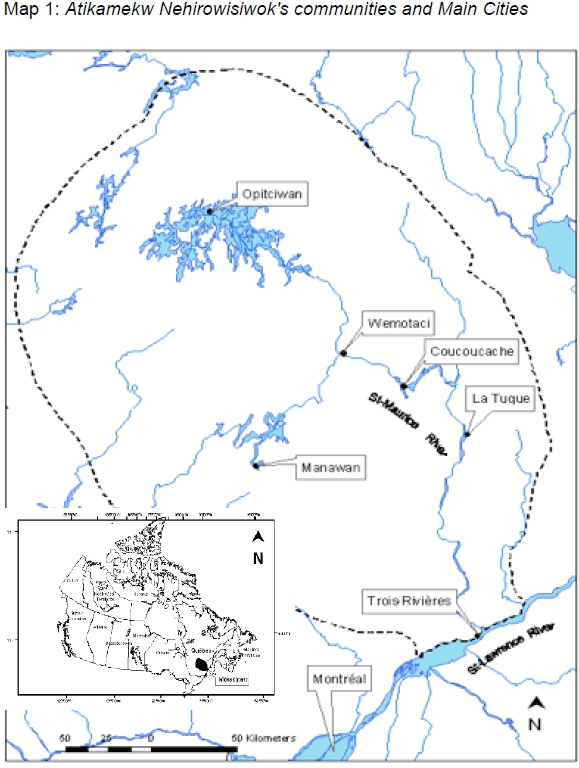

In the early 1900s, we were about 200 Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok. Nowadays, our population is just over 7,800 members gathered in four communities (the infamous reserves), including one that has not been inhabited for several decades, Kokaci or Coucoucache (see map 1: Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok's communities).

Our people are known as Atikamekw, which means "white fish". It is an ethnonym originating from a family clan that is part of our people or nation. It is a fairly recent name but one that is widely used in missionary writings. As a people, we have always used the term Nehirowisiw (plural Nehirowisiwok) to identify ourselves. It is an ethnonym, but the term refers first and foremost to who we are and who we should be, because it involves a set of values that are fundamental to us. Here is how Cécile Mattawa, a technolinguist at Opitciwan, translates the term Nehirowisiw:

The one who comes from the forest, his food is also described, his tools and equipment, the fact of using resources and the way to use them; a being who is independent of all others (wir tipirowe or autonomous), their identity also includes their beliefs, their territory, their lifestyle (Onehirowatcihiwin), their innate right ... as a Nehirowisiw, the resources and elements they adapt to their life (e.g. a [Nehirowisiw] can only report or tell about the benefits of a medicinal plant if it grows on their territory).9

Nehirowisiw entails respect of a set of rules and values that are orally transmitted from generation to generation. These include rules related to the preservation and use of resources and the fundamental values of personal autonomy, sharing and reciprocity. These values remain essential to Atikamekw Nehirowisiw, to our identity.

3 Some elements of our customary law and traditional sanctions

The central institution of our nation is the family, either immediate or extended. Elders say peikw otenaw, "the main and primary community" when they talk about the family. It is in this nucleus that transmission, education, value teaching, teaching of hunting techniques, etc. take place. Needless to say, these activities are carried out in the territory.

In Atikamekw Nehirowisiw society and customary law, women play a fundamental role. They are the ones who ensure the health and well-being of both children and the community as a whole. The mother takes care of the children from 0 to 5 years old. From the age of 5, boys are taught to hunt and become providers. They learn with their father, but also a lot with their grandfather and their uncles. Girls continue their learning with their mother, grandmother or aunts. They start learning how to prepare game, etc., the activities that women used to do in the camps during the time of nomadic life. Before becoming sedentary, children also received instruction during summer gatherings and meetings. It could be extended family members or group members who passed on their knowledge.

Slowly, young people are allowed to explore their autonomy. From the age of 10 to 12, boys are allowed to go hunting alone (partridge, hare, etc.) until marriage. Kokomak (grandmothers) give advice to the soon-to-be married couples. It is also these kokomak who are the guardians of family ties (to avoid inbreeding). The Kokomak society is a traditional institution of ours whose role is to ensure social cohesion, respect for the rules of marriage, clan membership, territorial belonging, etc.

Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok families hold a set of rights and responsibilities over the management of the resources of their home territory. Following childbirth, the Nehirowisiw iskew (Atikamekw Nehirowisiw woman) buries her placenta within her territory. This practice, which was abandoned between the 1970s and 2000s, is now coming back to life and some women who give birth in the community or in hospitals outside the community are asking to keep their placenta to bury it in their hunting grounds. This practice demonstrates the attachment to notcimik - the territory of origin and belonging. Notcimik provides for us throughout our lives, even when we are in our mother's womb. The foetus within the mother is fed by the resources of the territory, of notcimik. After birth, the placenta that is buried within notcimik returns to feed the soil. The burial of the placenta within notcimik is also a mark of presence in and belonging to the territory. The elders often tell us, in detail, about the births that took place within notcimik. Elders say that notcimik (the fauna and flora) must hear the baby cry after birth. It is important for the animals to know that we are here. Attending the territory from birth or at a very early age strengthens the attachment and relationships between Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok youth and their home territory. Births within notcimik, although rare nowadays because the majority of women give birth in hospitals, are important events. These events are recorded in our toponymy. Several sites still bear the name of the person who was born there.

Families develop an attachment and a form of expertise related to the management and use of resources within notcimik. By the same token, they have a social responsibility to share resources with other families. It is in this sense that the values of sharing, respect and reciprocity are intrinsic to Atikamekw Nehirowisiw identity (see quote from Cécile Mattawa, above).

However, we cannot say that there have never been any conflicts among families regarding the management and sharing of territorial resources. When our elders talk about the traditional way of resolving conflicts, they talk first about prevention, problem solving and reparation rather than punishment. We first aim for balance: to rebalance what is unbalanced. Often, these processes are ritualised. They are ritualised so that the people involved can integrate certain elements into their lives, because these practices transform us as a person and as Atikamekw Nehirowisiw.

Nevertheless, there have also been different forms of sanctions in our society, particularly when the actions taken may threaten the lives of others or of a group of people. Sanctions are intended to repair the fault or to teach a lesson to the wrongdoers to prevent them from repeating their misdeed. We will give some examples of sanctions practiced in our communities.

One winter, during a very difficult time for everyone (not much game or food), a young man made a joke about killing a moose (e ki nipasowetc). The whole group had got ready to go and prepare the moose (kitci nta nikotisotcik). On arriving at the site, the young man admitted that it was a joke (e ki arimikaniwok). He was asked to bring the sleds back to the camp by himself (kitci kiwetapehitc).

To give another example of punishment: a man kept killing moose, more than enough. He had been warned several times but he kept going. At one point, the group members gave him a consequence, but did so after several warnings. They confiscated his weapon (okripinime), which is an essential tool for hunters. Without a weapon, the hunters cannot assume their role as providers within their family and solidarity inter-family networks. This sanction allowed this person to understand that he could not overexploit the territorial resources as this could harm the species' preservation and the survival of future Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok generations.

Another example of an event that took place in the Manawan community, again with young people is that they wanted to play a joke on a hunter by nailing his bark canoe to a stump. There was an investigation to find out who did this. We found out who it was, and the young people admitted their wrongdoing. By breaking the canoe, they prevented a community member and his family from hunting and fishing. Just like the rifle, the canoe is an essential tool for the hunter and not being able to use it could compromise his survival. A consequence was given to these young people. We required them to craft a bark canoe to compensate for the one they had damaged. Crafting a bark canoe requires several weeks of work. Following this sanction, they never played that joke again.

These are just a few of the many examples of possible sanctions for failing to respect certain fundamental principles, such as respect for the autonomy of the individual and respect for and preservation of fauna and flora. We have always been taught not to kill animals in vain. Under our principles, we can kill an animal for our subsistence, but it is absolutely forbidden to kill for fun or to waste the meat and skin of the slain animal.

4 Atikamekw Nehirowisiw and Wemitcikocic coexistence

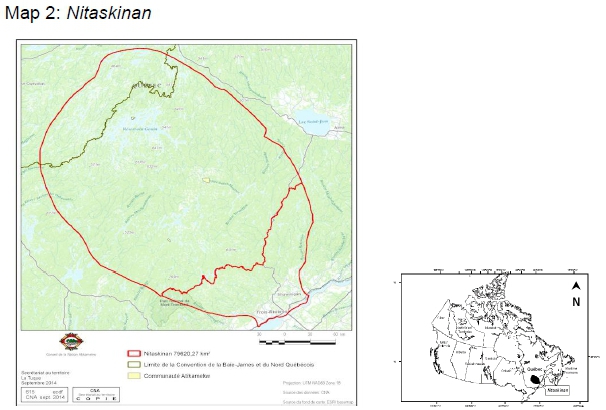

We have been in contact with the Wemitcikocicak (a word to describe the Europeans who arrived around 1600, mainly the French) for hundreds of years. Over the past two centuries, the Wemitcikocic has created enormous pressure on Nitaskinan, our ancestral territory (see map 2: Nitaskinan). These include the major impacts on:

• the forest industry since the 1800s;

• the hydroelectric dam construction;

• the railway construction;

• private clubs, outfitters and Controlled Harvesting Zones (ZECs);

• forced sedentarisation (the creation of indigenous reserves);

• the mechanisation of the forest industry in the 1970s.

After the arrival of the Wemitcikocicak, there were changes in our way of life. We adopted manufactured objects, such as the rifle. The Wemitcikocicak have also adopted products from our material culture, such as maple water. It was, among others, Atikamekw Nehirowisiw who taught the knowledge related to maple water to the French. In the Manawan community, each spring, some Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok families still prepare maple water in the traditional way. Harvesting maple water requires skills held by only a few families of the community who have a thorough knowledge of sugar maple (irinatikw).

The cohabitation of Atikamekw Nehirowisiw and Wemitcikocic is not always straightforward, as the values and practices related to resource management are not necessarily the same. Within Nitaskinan, Wemitcikocic gives itself abusive rights to exploit natural resources. By resource exploitation, we mean first of all forest exploitation. For more than a century, our region has been the core of Quebec's forest industry. Cities such as Trois-Rivières (Metaperotin), Shawinigan (Acowinikanik) and La Tuque (Capetciwotakanik) have developed around the forest industry. Since the 1970s, with mechanisation and the new methods of wood fibre exploitation, our ancestral territory has undergone enormous transformation. Clearcutting with increasingly destructive machinery removes a significant portion of wildlife habitat and food, and also crushes and destroys the soil (and the micro-organisms that live in it), not to mention the pollution of groundwater aquifers. Hunters have been noticing that the land changes caused by the forestry industry impact the demographics and health of animals such as moose, hare and beaver.

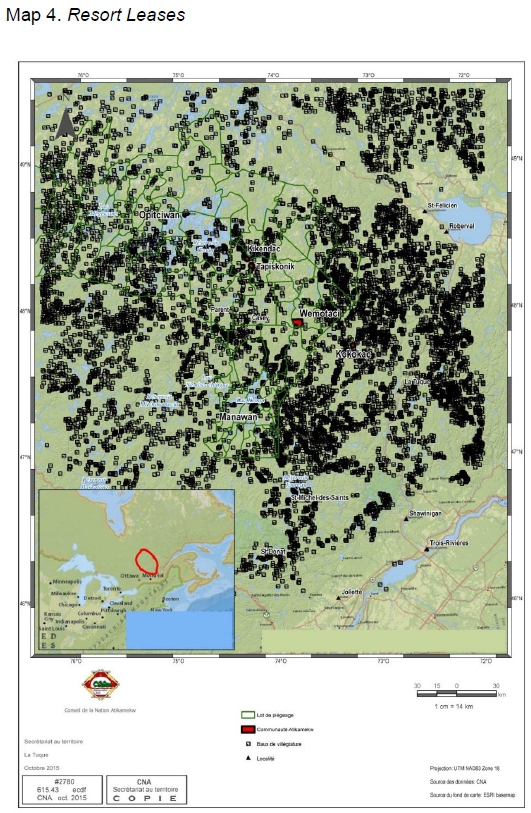

In addition to the presence of forestry companies on our territory, we also note the presence of several dozen outfitters and thousands of non-native vacationers who hold natural resource use and exploitation rights granted by the Government of Quebec. To make hunting and fishing territories accessible, in 1978, the Government of Quebec created the Controlled Harvesting Zones, commonly known as ZECs (see Map 3: ZEC). Since the creation of ZECs, nearly 50,000 resort leases have been granted through public tenders in the province, including several thousand on Nitaskinan alone (see map 4 Resort Leases). There are also several dozen outfitters who, like vacationers, have rights to use and exploit natural resources granted by the Government of Quebec. ZECs therefore promote access to ancestral native territories for non-native sport hunters. The latter are often unaware that they hunt and fish on our unceded territories, and this can cause conflicts between native families and non-native sport hunters.

In conjunction with the pressure on the land, Wemitcikocic have also created pressure on our very mental integrity, with, for example, the evangelisation practices of missionaries and the residential schools created by the federal government with the explicit purpose of assimilating us.10Between the 1950s and 1980s, residential schools brought together native youth from across the country in various church-run institutions to forcibly teach them French and English as well as Christian values, while denying them the opportunity to speak their mother tongue and practise their rituals. In our nation, residential schools have caused the breakdown (ki orapirin) of the family nucleus and of the community and shattered our knowledge and territorial occupation. That is to say, it caused our disempowerment, the imposition of another way of life (among other things, individualism), self-denigration, etc.

It is in this colonial context where our land rights are not recognised, our territorial resources are squandered and stolen and our young people find it difficult to attend the territory and put ancestral knowledge into practice that we have collectively decided to work on putting our land rights into writing.

5 Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin - Objectives of the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice

The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice is a collective project that sets out to put our own territorial regulations in writing. Basically, it is a document that lists the rules related to hunting, fishing and harvesting of certain plants. These rules have been transmitted for thousands of years, essentially through oral communication. Our elders simply say "weckatc", for a very long time. First of all, it is interesting to note that our elders say that these are not rules created by us, Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok, but rules that come from notcimik, from the territory of origin and belonging. The source of the code of practice must be the shared territorial knowledge of seniors and families. This is why our approach is intended to be collective and consensual.

The code of practice has three main objectives: to transmit our normative knowledge, to adapt our rules to the contemporary context and to foster the recognition of our normative practices and principles by non-natives and governments.

1. Transmission of normative knowledge to young Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok: As noted above, one of the many consequences of residential schools is the very significant disruption in the transmission of traditional knowledge. When the young people came back from residential schools and had children, they could not pass on what they did not have as an education themselves. One of the objectives of our efforts is to create such knowledge-sharing spaces for elders and younger generations. This knowledge can be taught in schools in Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok communities.

2. Adaptation of our rules to today's reality: We recognise that many things have changed over the past several decades. Let us just consider demographics. We are more numerous today and the resources of the territory will not necessarily be sufficient to meet everyone's needs. We must also adapt our traditional practices by using new technologies. For example, hunting practices have changed significantly with the use of motor vehicles. The introduction of the freezer has also had an effect on meat sharing practices. In the past, when communities had fewer members and there was no freezer, hunters would share their catch with everyone. Today, some hunters keep pieces of meat in the freezer and share them on special occasions.

As in many contemporary societies, young people use technology a lot. It is now one of the preferred means of passing on traditional knowledge. Elders share their knowledge on different platforms, such as community radio. The Internet is also a tool that the Cultural Service of the Atikamekw Nation Council uses to encourage young people to take an interest in their cultural heritage.

3. Recognition and respect for our normative knowledge: The code of practice also operates within the context of a comprehensive land claim process initiated with the governments of Canada and Quebec since 1979. As a people, we are still sovereign and autonomous within our ancestral territory. We have never surrendered our sovereignty.

Although no agreement has been signed to date, we are pursuing efforts to have our territorial rights and regulations recognised. As we seek to achieve self-determination, we are committed to enforcing the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice within our territory. The application of this code is done internally, for the members of the Nation, for the time being. Non-natives are governed by their own rules and laws. Asking non-natives to adopt our code of practice means passing on our knowledge to them and giving them rights in our territory. That is why we will keep our code of practice for the members of our Nation, for the people who play a role in our society, in our traditional institutions and within Nitaskinan.

6 Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin - the process of developing the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice

Developing the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice is intended to be a collective and consensual project aimed at updating normative practices, principles and processes in a coherent manner and in accordance with the epistemological and ontological principles passed on by our ancestors. The orocowewin concept included in the orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin phrase refers to consensual decision-making. Orocowewin could be translated literally as "what is decided together". This concept can also refer to a major collective project, of a political nature or otherwise, or to a direction to be taken (a life path). Some Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw (CNA) documents11 prepared in the context of the self-government claims and the development of the Nitaskinan Constitution translate this concept into decision, regulation, law, resolution, ruling, order-in-council. The sentence orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin could be translated as: "a societal project to develop the rules of coexistence within our forest land; a place of origin and intimacy".

The consultation processes conducted throughout the code of practice development project have led in recent years to the drafting of several documents that are still identified as "working documents" or "documents for consultation only". At a territorial symposium held in Opitciwan in the spring of 2015, three main documents were discussed: a document entitled "Notcimik"12 which is identified as the "territorial base", a document on territorial principles ("Kiskeritamowina e aspictaiikw askik itekera") and the code of practice ("orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin"),'13which combines a set of rules related to hunting, fishing and harvesting activities. All of those three documents were distributed and discussed during the symposium.

The first document, "Notcimik", which brings together a body of knowledge related to animals (their behaviour, the use of their body parts), plants (their characteristics, their uses) and climate (markers of change in climate on animals, insects, snow, water, moon and wind) is the most voluminous of the three. As we have previously stressed, this document remains incomplete since several pieces of information have not yet been put in writing, in particular knowledge relating to small animals, including migratory birds.

The document on territorial principles ("Kiskeritamowina e aspictaiikw askikw itek era") describes the values guiding territorial management activities (tipahiskan) and the system of territorial authority and responsibility (tiperitamowin aski) based on territorial knowledge (kaskina nehiro wisi kiskeritamowina). The document highlights, for example, the role of ka nikaniwitcik (territorial leaders) in resolving territorial disputes and in the transmission and distribution of family hunting territories. Emphasis is placed on the flexibility of the family hunting territory system that takes into account "family history, deaths and alliances woven over time".14 Oral tradition remains important in these processes of transmission and distribution of responsibilities and territorial rights. It ensures maintenance of this flexibility and the "relative autonomy"15 of local institutions and customary law in the contemporary context.

As with the document on the territorial basis and principles, the code of practice (Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin) remains to this day in the proposal phase and is considered a "working document". It mainly deals with a set of obligations to ensure respect for animals and plants and the preservation of balanced relations with them. This document includes a number of prohibitions on behaviours that may be considered disrespectful to plants and animals, may reduce the availability of resources or may hinder the maintenance of networks of reciprocity between families.

These works are closely linked to each other. In fact, the exercise carried out in recent years aimed to ensure that the code of practice was the result of a pooling of territorial knowledge (contained in the territorial database) and territorial principles. For the members of the code of practice working group, it was essential to connect the rules of conduct concerning hunting, fishing and harvesting activities with knowledge related to animal behaviour, plant use and utility, as well as the principles guiding the forms of territorial authority passed on by the ancestors.

These three documents were produced through a consultation process with elders and ka nikaniwitcik from the three communities. The territorial symposia held in Wemotaci (2014) and Opitciwan (2015, 2016) aimed to discuss this work, validate its content and make additions and amendments to it. The discussions held during these symposia were recorded and broadcast in the three communities and to members living outside the communities via community radio stations and the Société de Communication Atikamekw-Montagnais (SOCAM), which means that a significant proportion of the Nation's members have access to information and can participate in the discussions directly or through a family representative. First, the whole process allowed the members of the Nation to share a set of experiences and family knowledge. Second, this process allowed the members of the Nation to deliberate on a societal project and to discuss the development of an Atikamekw Nehirowisiw government that would emanate from the normative values and principles promoted by elders and territorial authorities.

7 The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw authority system and the issues involved to writing the code of practice

It is important to point out that the process of writing customary law is not unanimously accepted within the nation. This is why the documents have not yet been made public today. It turns out that the writing of customary law raises certain issues related to the way we practise our own system of authority.

In discussions around the development of the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice, some interlocutors mentioned their discomfort in writing and formalising "rules" in a form that is not their own. Some feel that once written, this code would be similar to what state (non-native) institutions "impose" on citizens, and would limit their autonomy rather than defend it.

Indigenous customary law, once written and formalised, can, depending on its use, entrench and circumscribe normative rules and practices that are intended to be flexible and adapted to the context of application. As Cruikshank16 points out, customary (unwritten) law emphasises the "legal process" of conflict resolution rather than the encoded and reified "legal product". Customary law, as it emerges through oral tradition, can then be understood as a "social activity" that articulates and adapts itself according to the context of application and the role and status of the involved parties.17

Some members of the Nation favour the transmission of knowledge and rules of conduct through oral tradition. We often say "atisokana ki atisokan" - we are infused and transformed by narratives. When the narrative permeates you, it never leaves you; it is now part of you. This relationship we have with the oral tradition, we do not have with the written word. The sharing relationship and sensitivity are different. With oral tradition, we relate to the person who narrates to us, in his or her own language formed by his or her territory of origin (notcimi arimowewin). You learn things about their territory of origin just by listening to the words they say, their accent, their tone. With writing, the teachings do not infuse you; it is as if they were dead. We do not hear notcimi arimowewin (the language of the territory) when the words are written. In the oral tradition, there is a whole sensory and emotional aspect that is not found in the written word. The oral tradition appeals more to affect, to the heart than to the intellect, the head. Furthermore, it is said that narratives (atisokana) contain two hearts: it is the relationship between our communicating hearts and the foundation of our community, our life and our social cohesion.

Atisokana shared by our ancestors contain the necessary elements to ensure the transmission of normative knowledge related to Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok life and values. Ensuring respect and transmission of this knowledge through oral tradition is in itself an act of autonomy, power and responsibility. According to Anicinabe author and activist, Léanne Simpson,18 transmitting these stories can even be interpreted as an implicit or explicit act of resistance; a way of assuming sovereignty and difference in the midst of unequal power relations and assimilative policies. This mode of transmission is also part of the local authority system.

Our elders, who are represented as authority figures and guardians of knowledge, decide with whom and when they share their knowledge and stories. Also, knowledge bearers will not transmit all their knowledge to a single person. They will share parts of their knowledge with different people, usually with people to whom they have also passed on part of their territorial and family responsibility. It is the elders who choose which part of their knowledge they transmit and to whom they transmit it. This mode of knowledge transmission is linked to a deeper philosophy based on balance, social cohesion and the equitable distribution of knowledge and power. The idea underlying this approach is, first and foremost, to distribute knowledge and responsibilities and to encourage individuals and families to work together, interact and make their own contribution. In this sense, this model of knowledge transmission contributes to ensuring social cohesion and an equitable distribution of rights, powers and responsibilities.

The transmission of knowledge through oral tradition is also closely linked to the transmission of roles, statuses and responsibilities. Family members recognise the status, contribution and authority of each individual in specific areas. These roles, powers and responsibilities are often transmitted within families. This transmission relates directly to the family knowledge developed and transmitted within family hunting territories. Putting in writing elders' knowledge has the effect of partially modifying this mode of transmission of knowledge, authority and responsibilities, depending on the use that is made of it.

During these meetings, some members of the Nation expressed a measure of scepticism regarding the writing down of their customary law, which should define their ancestral rights - expressing concern, for example, that this practice could limit their ancestral rights rather than ensure their legal application. Some also say that this practice constitutes a disavowal of the role and authority of elders.

At the territorial symposium held in Opitciwan in 2015, a young person from the community expressed his fear that the writing of the code of practice would transform the traditional system of territorial authority:

What I think of this document: everything the elders said, their knowledge, etc., has been transcribed. It's like we cheated on them. When we have completed our work on the code and if we adopt it without really knowing its content, then the government will be the first to be pleased with our decision. Not long ago, before the holidays, I had a dream. I dreamt that our three communities now lived in one big village. We were now living together in one place. Then we heard rumours that the kokocew was coming to devastate our village. The elders then told people to prepare themselves, to prepare everything that is useful and to prepare all our stock of traditional food, game, meat, etc., and to go hide all this in the woods so that it would not be destroyed. Then the kokocew arrived in the village, it looked like a dog and was made of metal and its face looked like that of a man with very clear eyes. He first goes to see those who helped him, and kills them, and he is very happy to kill them. Then, he ransacks the big village, I see women fleeing into the woods with their children. As I am getting ready to run away, two women come to me to give me their moccasins, which they have been keeping for a long time, saying to me: take these moccasins and bring them with you, they are the only things we have left. That's what my dream was. And when I think about the documents we are discussing, I wonder where it will lead us. I don't know what decision will be made when the work on the code is finished, but I can't say that it's all very good. It can be very damaging for us, thinking about its impact on our future, considering all the barriers the government wants to impose on us. That is all I wanted to say at the moment in our assembly. Thank you for listening to me.

The hesitation about putting customary law into writing certainly comes from a fear associated with its use by non-Native institutions. It must be said that the colonial legacy has heavily impacted the trust that members of the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw Nation have in the government and in non-Native institutions in general, which they sometimes liken to kokocew, an anthropomorphic cannibal entity. The fear is that the misuse of the code of practice will limit Atikamekw Nehirowisiw sovereignty, rights and territorial responsibilities and even disrupt the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw territorial authority system, in which elders (kimocomonowok) and ka nikaniwitcik play a prominent role.

Yet, kimocomonowok and kanikaniwitcik are not necessarily opposed to some of their knowledge being written and made available to all Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok members. In fact, they have often participated in the recording of their narratives and knowledge as part of various research and community projects devoted to the promotion and transmission of knowledge. Recordings made in such contexts have been widely broadcast on community radio and in schools for the benefit of young people in the communities. The implications of writing their stories are not all that different from those of audio recordings, provided that the use of the narratives and knowledge is made wisely. The problem is not simply with writing down the knowledge of elders, but rather with the codification and setting of rules based on the knowledge of elders.

It is important to note that several elders voluntarily participated in the process of developing the code of practice, which aimed to put territorial knowledge ("Notcimik" document), territorial principles ("Kiskeritamowina e aspictaiikw askik itekera" document) and finally territorial regulations ("Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin" document) into written form. The participation and expressed willingness of Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok elders in the code of practice development project provides legitimacy to the project. This participation also leads to a significant mobilisation of Nation members and political representatives of the band councils and the Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw.19 To date, the code of practice is written and will, like any legal text, be subject to constant revision. The document is currently only accessible to members of the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw Nation as we consider it essential that our members can integrate, revise and improve the code before making it accessible to non-natives and to our state interlocutors.

In summary, putting our territorial regulations into writing continues to spark debate within our nation. Over the past few years, several points of view have been expressed regarding this process of developing the code of practice and we must point out that, although we have not yet reached a consensus, these debates have allowed us to share territorial knowledge among ourselves, strengthen our relationships and exercise our political know-how as we developed our consultation approaches in accordance with the methods the elders showed us. This experience has shown us that it is not only the finished product (the code of practice) that is important, but also the whole process and mobilisation around this collective project in which we are involved as a people.

8 Conclusion

The writing of indigenous customary law, often described as fluid, relational and intrinsically linked to local cultural and political dynamics, necessarily poses several challenges. 20 Janine Ubink21 describes this process of writing as the passage of local customary practices into judicial customary law. This passage necessarily implies an alteration, as much in nature as in the content of customary law. At the same time, the writing of customary law facilitates both the transmission of indigenous legal knowledge and its recognition by state interlocutors. It is in this idea that Atikamekw Nehirowisiw made the non-irreversible choice to engage in this process.

The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice aims to ensure the transmission of our normative knowledge, our ancestral rules for living well together within notcimik, our place of origin and belonging. This code also aims to ensure that territorial regulations are adapted to the contemporary context, the new demographic reality, the new technologies and the anthropogenic transformations of Nitaskinan over the past decades. Lastly, the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice is also a document that will be used in the creation of an Atikamekw Nehirowisiw autonomous government, which will be responsible for enforcing it.

As we have pointed out in this text, there is no unanimity among the members of the Nation regarding the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice. The important aspect to remember here is the richness of the process and the dynamism shown by Nation members with respect to these projects of knowledge transmission and self-determination. For more than 40 years, elders, territorial leaders and members of band councils and the Council of the Atikamekw Nation mobilised to work together on the creation of an autonomous government that will implement the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw code of practice. Even though the code of practice remains a "working document", this collective project has enabled us to share and transmit family and territorial knowledge in an appropriate form, with due respect for our own system of authority and transmission of normative knowledge. In this respect, this project is an expression of cultural and identity affirmation.

The article raised some concerns related to the writing of our customary law. These concerns shared by members of the Nation teach us that the code of practice must better identify the main, broader territorial principles and knowledge that will not compromise flexibility in the application of territorial regulations or our system of territorial authority that is based on the specific knowledge of families. In accordance with our system of authority based on the values of complementarity and reciprocity, territorial knowledge and territorial jurisdictions continue to be transmitted in the family networks. As the article points out, family and family networks are still our central cultural, political and legal institution. In our words, this institution is Peikw Otenaw, our main and primary community.

The collective project of writing our customary law teaches us that not all knowledge has to be written. In working on the code of practice, we agreed not to mention family knowledge related to medicinal plants and ritual knowledge. This knowledge remains in the families who remain its guardians. This knowledge also remains anchored in notcimik and will continue to exist as long as life (pimatisiwin) remains. We trust our families and we also have trust in past and future generations. We have trust in the future of our people and our nation; we are confident that they will use, in their practices within the territory, our ways of doing and being, especially in the application of territorial regulations, which must first and foremost continue to be passed on through the oral tradition. Putting it in writing is also appropriate, but it will never replace oral transmission and can never be complete, because we can in no way gather all the territorial knowledge in a written document.

Bibliography

Literature

Chanock M "Neither Customary nor Legal: African Customary Law in an Era of Family Law Reform" 1989 IJL&F 72-88 [ Links ]

Chanock M Law, Custom, and Social Order: The Colonial Experience in Malawi and Zambia (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 1985) [ Links ]

Commaroff J "Colonialism, and the Law: A Foreword" 2001 L & Soc Inquiry 305-314 [ Links ]

Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw E Nehiromonaniwok ka aicinikateki Atikamekw iriniw kitci masinahikan ka wi orasinahikatek / Termes de référence en Atikamekw pour la Commission sur la Constitution Atikamekw (Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Nehirowisiw La Tuque 1998) [ Links ]

Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Commission territoriale atikamekw, 29-30 octobre 2012 (Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Nehirowisiw La Tuque 2012) [ Links ]

Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Orocowewin Notcimik Itatcihowin: Propositions de règles du futur code de pratiques Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok. Document de travail (Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Nehirowisiw La Tuque 2015a) [ Links ]

Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Notcimik. Document de travail (Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Nehirowisiw La Tuque 2015b) [ Links ]

Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Kiskeritamowina e aspictaiikw askik itekera: Principes territoriaux. Document de travail (Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw Nehirowisiw La Tuque 2015c) [ Links ]

Cruickshank J The Social Life of Stories: Narrative and Knowledge in the Yukon Territory (UBC Press Vancouver 1998) [ Links ]

Éthier B Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin: Ontologie politique et contemporanéité des responsabilités et des droits territoriaux chez les Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok (Haute-Mauricie, Québec) dans le contexte des négociations territoriales globales (PhD-thesis Université Laval 2017) [ Links ]

Gluckman M The Judicial Process among the Barotse of Northern Rhodesia. (University Press for the Rhodes Livingston Institute Manchester 1955) [ Links ]

Gluckman M Custom and Conflict in Africa (Basil Blackwell Oxford 1963) [ Links ]

Lavoie K Savoir raconter ou l'art de transmettre: Territoire, transmission dynamique et relations intergénérationnelles chez les Wemotaci iriniwok (Haute-Mauricie) (Masters thesis Université Laval 1999) [ Links ]

Merry SE "Law and Colonialism" 1991 L & Soc'y Rev 889-922 [ Links ]

Moore SF Social Facts and Fabrications: "Customary" Law on Kilimanjaro (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 1986) [ Links ]

Morphy F and Morphy H "Anthropological Theory and Government Policy in Australia's Northern Territory: The Hegemony of the 'Mainstream'" 2013 Am Anthropol 174-187 [ Links ]

Morphy H "'Not just Pretty Pictures': Relative Autonomy and the Articulations of Yolngu Art in its Context" in Strang V and Busse M (eds) Ownership and Appropriation (Berg Oxford 2011) 261 -286 [ Links ]

Ottawa G Les pensionnats indiens au Quebec: un double regard (Editions Cornac Montréal 2010) [ Links ]

Poirier S "Contemporanéités autochtones, territoire et (post)colonialisme. Reflexions sur des exemples canadiens et australiens" 2000 Anthropologie et sociétés 137-153 [ Links ]

Rouland N Anthropologie juridique (Presses universitaires de France Paris 1988) [ Links ]

Simpson L Dancing on our Turtle's Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Recreation, Resurgence and a New Emergence (Arbeiter Ring Winnipeg 2011) [ Links ]

Snyder F "Colonialism and Legal Form: The Creation of 'Customary Law' in Senegal" 1981 J Legal Plur 49-90 [ Links ]

Ubink J "The Quest for Customary Law in African State Courts" in Fenrich J-M, Galizzi P and Higgins T (eds) The Future of African Customary Law (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2011) 83-102 [ Links ]

Legislation

Indian Act, 1876

Internet sources

Mattawa C 2019 Identité http://www.atikamekwsipi.com/identite accessed 11 August 2019 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

Am Anthropol American Anthropologist

CNA Council of the Atikamekw Nation

IJL&F International Journal of Law and the Family

J Legal Plur Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law

L & Soc Inquiry Law and Social Inquiry

L & Soc'y Rev Law and Society Review

SOCAM Société de communication Atikamekw-Montagnais

ZEC Controlled Harvesting Zones

Date Submission 4 October 2018

Date Revised 27 June 2019

Date Accepted 8 July 2019

Date published 12 December 2019

* Benoit Éthier. PhD (Anthropology, Université Laval, Québec). Assistant professor at School of Indigenous Studies, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Val-d'Or, Canada. E-mail: Benoit.ethier@uqat.ca.

** Christian Coocoo. Coordinator at Services culturels, Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw, La Tuque (Québec), Canada. E-mail: ccoocoo@atikamekwsipi.ca.

*** Gérald Ottawa. Researcher at Secretariat au territoire, Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw, La Tuque (Québec), Canada. E-mail: gottawa@atikamekwsipi.ca.

1 Gluckman Custom and Conflict; Gluckman Judicial Process among the Barotse; Snyder 1981 J Legal Plur; Chanock Law, Custom, and Social Order; Chanock 1989 IJL&F; Merry 1991 L & Soc'y Rev; Commaroff 2001 L & Soc Inquiry; Ubink "Quest for Customary Law".

2 As applied in some British colonies, such as colonies in Africa and India, colonial regimes based on the indirect rule principle delegate administrative responsibility to local administrations that are still part of colonial administrations. In contrast, under the direct rule, the control of the public affairs of a colony is under the direct administration of the colonial state.

3 Chanock Law, Custom, and Social Order 182.

4 Merry 1991 L & Soc'y Rev 897.

5 Moore Social Facts and Fabrications 190.

6 This article is the result of a research collaboration between Christian Coocoo (CNA), Gérald Ottawa (CNA) and Benoit Éthier (UQAT) that began in 2012. Some parts of this text are from Benoit Éthier's doctoral thesis submitted in 2017 (Éthier Orocowewin notcimik itatcihowin).

7 "Code of practice" is an approximative translation of the itatcihowin concept. This translation is more appropriate than others such as "codification" since it refers specifically to normative practices and behaviours.

8 Notcimik translates literally as "the place where I come from". It is a place of origin, but it also represents the territorial resources that sustain us.

9 Mattawa 2019 http://www.atikamekwsipi.com/identite. French translation.

10 Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw 2015a Orocowewin Notcimik Itatcihowin; Lavoie Savoir raconter ou l'art de transmettre; Ottawa Les pensionnats indiens au Québec; Poirier 2000 Anthropologie et sociétés.

11 Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw 1998 E Nehiromonaniwok ka aicinikateki Atikamekw iriniw kitci masinahikan ka wi orasinahikatek; Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw 2012 Commission territoriale atikamekw.

12 Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw 2015b Notcimik.

13 Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw 2015a Orocowewin Notcimik Itatcihowin.

14 Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw 2015c Kiskeritamowina e aspictaiikw askik itekera.

15 Morphy "Not just Pretty Pictures"; Morphy and Morphy 2013 Am Anthropol.

16 Cruickshank Social Life of Stories 70.

17 Rouland Anthropologie juridique.

18 Simpson Dancing on our Turtle's Back.

19 Unlike Native band councils, which are institutions created by the federal government and legislated by the Indian Act, 1876, the CNA is an institution created in 1983 by members of the Atikamekw Nation. The CNA's primary role is to defend the interests of members of the three communities and represent them in negotiations with the governments of Canada and Quebec.

20 Chanock Law, Custom, and Social Order; Chanock 1989 IJL&F; Merry 1991 L & Soc'y Rev; Commaroff 2001 L & Soc Inquiry; Ubink "Quest for Customary Law".

21 Ubink "Quest for Customary Law".