Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.22 no.1 Potchefstroom 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a5803

ARTICLES

Examining the Land Use Act of 1978 and Its Effects on Tenure Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Ekiti State, Nigeria

University of Cape Town South Africa. bblkeh001@myuct.ac.za; simon.hull@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The Land Use Act of 1978 (LUA) has failed to achieve some of its objectives. The rural poor and the vulnerable are those most affected. The failure is ascribed to problems inherent in the Act and poor implementation. This paper discusses the effect of the LUA on the customary ownership of land and its effect on the tenure security of the rural poor. Using a conceptual framework for guiding cadastral systems development, the critical areas of the LUA as pertains to tenure security are analysed for the degree of their success, sustainability, and significance. The framework looks at the underlying theory, the drivers of change, the change process, and the land administration system. A mixed methodology approach was adopted for the study, using a single case study. Three groups of respondents contributed to the study: land professionals, civil servants and students. The study found that securing title to land is difficult, compensation provisions need to be reviewed, formal land registration is not in the interest of the poor, land is not available at an affordable rate, land speculators are still active in Nigerian land markets, the composition of the two committees is inadequate, and the refusal to grant certificates to people below the age of 21 is age biased. It further revealed that the power granted to the governor is enormous and unnecessary. The findings showed that the LUA is both effective in some areas and dysfunctional in others. This is because of the age of the Act and the lack of a pro-poor policy focus. Based on these findings recommendations were made, including that a new policy be enacted that includes pro-poor policies and customary laws. The LUA is found to be useful in urban areas, but not in solving land-related problems in rural areas. This study provides an understanding of the legal holding of land in Nigeria.

Keywords: Land administration; Land Use Act; tenure security; customary tenure system; customary law; customary ownership; pro-poor policy; Nigeria.

1 Introduction

Land is the primary asset of the rural poor in Nigeria, where 80% of the population are peasant farmers.1 When the LUA was promulgated in 1978, the Nigerian population was 69 million.2 Four decades later the Nigerian population is 193 million.3 As the population increases, the demand for land also increases; therefore land tenure security is vital to the growing population of Nigeria. The economy of a country also depends on this natural asset. Land policy affects the economy of a nation either positively or negatively depending on how effectively the policy is implemented.4

There is no shortage of literature describing the Nigerian LUA and its effect on land ownership. The problems generally identified by the literature relate to landlord and tenant relationships,5 the conversion of freehold to leasehold,6 the astronomical rise in land values,7 the increase in speculation with land,8 the problem of consent provisions,9 hindrances to agricultural development and investment,10 and compensation provisions.11 This study contributes to the existing studies by evaluating the LUA in relation to the tenure security of the rural poor.

Amokaye12 notes that the LUA did not abolish customary land ownership and further recognised that it should be removed from the 1999 Constitution for it to achieve the twin objectives of equitable land distribution and efficient land administration. Atilola13 notes that the LUA has created more uncertainties about land ownership for peasant farmers.

Due to the problems created by the enactment of the LUA, the Nigerian government was desirous to reform the land tenure system in Nigeria. With the introduction of the Nigerian land reform programme in 2009, it was observed that the provisions of the LUA are a significant constraint on the programme's success.14 The flaws in the implementation of and failure to deliver a land administration system (LAS) that benefits all Nigerians are identified as the primary reasons for land reform in Nigeria.15 Nigerian land reform is at a crossroad after an attempt to carry out two pilot studies in Kano and Ondo state;16 this was because it was aimed at unlocking the "dead capital"17 of land held in rural areas.18

1.1 Defining terms

Customary law consists of customs that are accepted as legal requirements or obligatory rules of conduct, practices and beliefs that are so vital and intrinsic a part of a social and economic system that they are treated as if they were laws.19

Statutory rights of occupancy are granted by the governor of a state to land in urban areas per section 5(1) of LUA. Statutory rights of occupancy can be deemed to be issued or expressly granted by the governor of a state. When a right exists under customary tenure, or statutory tenure before the promulgation of the Land Use Act, the transitional provisions of section 34 (2) and 36 (2) of the LUA assume that the existing holders are deemed to be granted a certificate of occupancy. This certificate of occupancy has the same standing as the certificate of occupancy expressly issued by section 5(1) of the LUA.

Customary right of occupancy, per Section 51 of the LUA, means the "right of a person or community lawfully using or occupying land in accordance with customary law and includes a customary right of occupancy granted by a Local Government under this LUA".

Land tenure security is the perception by individuals or groups of people that their rights to the ownership, use or occupation of a piece or parcel of land will be free from encroachment, eviction or interferences from both internal and external sources.20 For a more explicit expression, tenure security may also be defined as the legal and practical ability to defend one's ownership, occupation, use of and access to land from interference by others.21 Tenure insecurity is caused by a lack of certainty as a result of land rights affected by conflicts. Sen22 describes a landless person as someone "without a limb of [his] own", which may lead to economic and social deprivations. In sub-Saharan Africa land tenure security is defined as "an emergent property of a land tenure system."23 The system comprises five interacting elements: people, social institutions, public institutions, land rights and restrictions, and land and information about land. Positive interactions among these elements improves tenure security.24 Land rights in rural areas are of primary importance if poverty and hunger will be reduced in society. At least three of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have land as a component (goals 1, 2, 5).25

The human rights-based approach (HRBA) recognises beneficiaries as stakeholders or rights-holders, and compels states to fulfil their duties towards citizens, while citizens must also respect the rights of others.26

Improvements or unexhausted improvements are defined, in Section 51 of the LUA, as "anything of any quality permanently attached to the land, directly resulting from the expenditure of capital or labour by an occupier or any person acting on his behalf, and increasing the productive capacity, the utility or the amenity thereof and includes buildings, plantations of long-lived crops or trees, fencing, walls, roads and irrigation or reclamations works, but does not include the result of ordinary cultivation other than growing produce".

Pro-poor is a term used to characterise policies that consider the people living in slum areas;27 it was later extended to the rural poor.28 It is used to define concepts that concern people living in poverty.29 In this context, it is used to refer to policy that considers poor people.

1.2 Land tenure security in Nigeria

Land tenure security is vital to the growing population of Nigeria. It is the way people perceive whether they are secure on their land. Land tenure security may significantly improve food security and quality at a relatively low cost. The main catalytic force to reduce poverty in Nigeria is access to land. Insecure tenure tends to strike at the foundation of the livelihood systems of the rural poor. For productivity and efficiency, secure access to tenure rights may be essential for encouraging investment. On the other hand, tenure insecurity may cause destitution and discourage farmers from investing in their farms.30 The tenure insecurity of the rural poor may lead to rural poverty while poor access to land may lead to increased poverty.31 It is noted that the sparse population in rural areas of Nigeria experiences tenure insecurity.32

Land rights holders in rural communities using the land for agricultural purposes (commercial or subsistence) can only access the formal land registration system for title registration. This system requires a minimum of 14 different steps to be taken, starting with the production of a survey plan of the land and the making of applications in a prescribed format. Different kinds of fees are paid, ranging from the opening of file fee, the application fee and the survey fee to various additional charges. These fees exceed a total of 22% of the land value.33 To obtain statutory or customary rights of occupancy a minimum of six to nine months is required for processing. After obtaining the certificate of occupancy, a landholder is required to pay an annual rental fee to the local government for the use of the land. The cost and bureaucratic procedures involved in the formal land registration system obstruct the rural poor from having secured tenure.34 For example, in Ekiti State very few rural dwellers have applied for a certificate of occupancy. In a three year study in Ekiti State, less than 2% of applications for certificate of occupancy were submitted.

The LUA does not specify if a certificate of occupancy granted can be renewed after the expiration of the 99-year leasehold, leaving the Governor with the option to renew or not. As the date of the expiry of the leasehold nears, insecurity of tenure will increase.

1.3 Problem statement, aims and objectives

While land is the primary asset of the rural poor, the LUA has reportedly failed to meet its objectives and is said to have caused many distortions to the land rights and access to land of Nigerians.35 The resulting tenure insecurity impacts negatively on the productivity of the land. This study addresses the problem of tenure insecurity in south-western Nigeria.

The poor, marginalised and vulnerable groups of the rural areas in Ekiti State are most affected by tenure insecurity. They rely mainly on land as a means of livelihood and hence must have secure tenure free from the fear of being evicted or of their land being encroached upon. In a recent land dispute between Itaji-Ekiti and Ayede-Ekiti, three people were killed.36 This conflict was caused by trespassing and the breach of an existing court judgement by the Ayede-Ekiti. This would not have happened if their land rights had been recognised, recorded and respected. The residents of Itaji-Ekiti are facing tenure insecurity as a result of land conflicts. Considering the triple indicators of tenure security37 - viz. legitimacy, legality and certainty - it appears that there is uncertainty in land rights.38 This research draws a distinction between the failure of the state to provide legislation that secures customary land tenure (de jure security), and customary laws and practices that provide de facto tenure security.

The aim of the study is to assess the effects of LUA on customary tenure security in Ekiti State. The associated objectives are to appraise the LUA in terms of its effects on customary land tenure and to examine the parts of the LUA that affect tenure security and that need a review in Ekiti State.

1.4 Research outline

Section 2 discusses the methodology while the review begins with an examination of publications related to the LUA. The methodology included using a questionnaire to gauge people's perceptions of the LUA, which was supplemented by several in-depth interviews to gain a deeper understanding of the pertinent issues. These are explained in section 3. Conclusions and recommendation are to be found in section 4.

2 Methodology

To achieve the stated objectives, a single case study using mixed methods was adopted. This is because a single case study provides a vibrant picture of a typical case and provides a better understanding of the case.39 The study is unique because no recent research relating to tenure security in this study area has been conducted. The study is also unique because it investigates people's level of tenure security vis-a-vis the operation of the LUA. A combination of random and purposive sampling methods was adopted for the study.

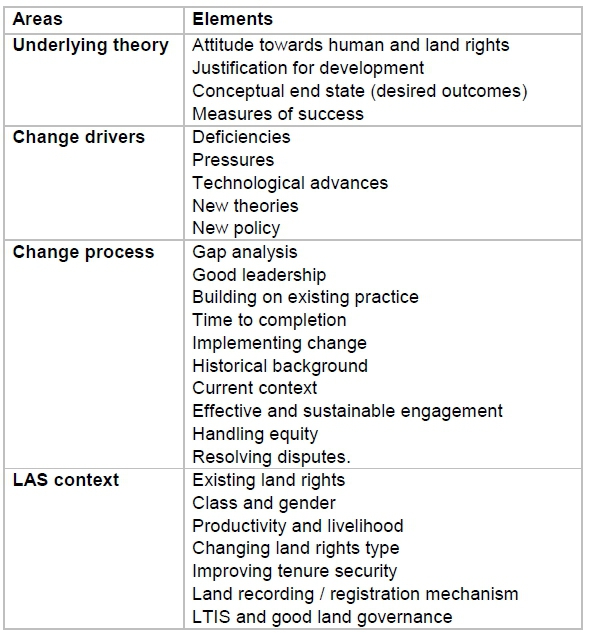

The conceptual framework for guiding cadastral systems development in the context of customary land rights40 is used to assess the Nigerian LUA of 1978 regarding its success, sustainability and significance41 for land rights-holders in South-western Nigeria. Success means achieving the required goals of development. Sustainability relates to the endurance of the intervention. In order for them to be significant, the goals of the development should arise from the needs of the land rights holders. The framework comprises four levels of detail: there are five evaluation areas, 13 aspects, 32 elements, and 87 indicators. This research uses 4 evaluation areas and 26 elements in its evaluation, because not all evaluation areas, aspects and indicators are applicable. See Error! Reference source not found. for the selected elements used.

Table 1 Abridged conceptual framework showing selected areas and elements used42

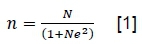

Four steps were used in executing the research work. Firstly, questionnaires were administered to professional land surveyors (Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State), professional estate surveyors (Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State), academics (Federal Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti), civil servants (from the office of the surveyor-general, Ekiti State; the Ministry of Land, Housing and Urban Development, Ekiti State; and 16 Local Government areas, Ekiti State), and students (Federal Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State and Federal University of Technology, Akure). These questionnaires were used to gather data as regards tenure security, which was subsequently used for the analysis. The population of the study comprised professionals dealing directly with land matters, and students studying surveying. At the time of the research, these individuals totalled 775. The sample size was calculated for each category to ascertain what each category would contribute to the study. Per Yamane,43

where n represents the sample size, N represents the population under study, and e is the margin of error (0.005). Hence, a sample size of 256 was used. The sample size was then organised into three groups: professionals, civil servants and students. There were 83 professionals, 142 civil servants and 27 students. Of the 256 questionnaires administered, 252 (98%) were returned.

Further data collection was performed via one-on-one, in-depth, semi-structured interviews. The interviews were used to gain a deeper understanding of the relevant issues. In such projects the use of multiple sources of evidence ensures the triangulation of the results and enhances methodological rigour. Three groups of respondents were interviewed: community heads, land rights holders, and heads of formal institutions. The institutions were the office of the Surveyor-General, Ekiti State; Ekiti State Housing Corporation, Ado-Ekiti; and the works department of the Oye Local government, Oye-Ekiti. In Itaji-Ekiti, 3 community heads were interviewed, 10 land rights holders and 3 heads of formal institutions were also interviewed. The interviews comprised the second step of the research.

Thirdly, the questions in the questionnaires administered were coded in the variable view of IBM SPSS (Spatial Statistics for Social Sciences 22). The data were entered into the data view of the SPSS. This was achieved by using the questionnaire identification numbers. Thereafter, the descriptive statistical analysis and correlation coefficient were used to analyse data from all departments together.

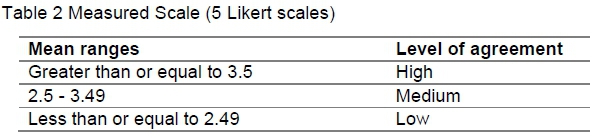

A 5-point Likert scale was used to rank the responses, and for the purposes of this publication only the means of the responses are presented. Table 2 shows how the 5-point Likert scale was graded as high, medium and low.

3 Appraisal of the Land Use Act of 1978

3.1 The underlying theory

3.1.1 Land Use Act and the place of the customary ownership of land

The LUA was promulgated in 1978. It replicates the land tenure law of 1962 in nationalising all land in Nigeria and placing it under the control of the state governors.44 Many academicians and legal experts have expressed different opinions on the interpretation of section 1 of the LUA: "Subject to the provisions of this Act, all land comprised in the territory of each State in the Federation are hereby vested in the governor of that State and such land shall be held in trust and administered for the use and common benefit of all Nigerians in accordance with the provisions of this Act". The interpretation of section 1 of the LUA resulted in two schools of thought on the impact of the LUA on the control and use of land in Nigeria, namely "nationalisation" and "private rights".45

3.1.2 The nationalisation school of thought

The nationalisation school of thought based its argument on the use of the words "vest" and "trust" in section 1 of the LUA.46 Many authors have supported the nationalisation school of thought.47 The word "vest" has been interpreted to mean that the ownership of land is transferred to the governor, and "trust" means that the LUA ascribes absolute credence to the governor. A court judgement on land matters also followed this school of thought. Thus, in Nkwocha vs Governor of Anambra State, Eso, JSC said:48

[T]he tenor of that Act as a single piece of legislation is the nationalisation of all lands in the country by transferring ownership to the state leaving the private individuals with an interest in land which is a mere right of occupancy.

With the provisions of section 1 of the LUA, the legal title of land is vested in the governor, although the legal title is not absolute, as it stipulates that the governor is required to exercise the control and management of the land for the benefit of all Nigerians.49 The vesting of this legal title assumes the existence of other titles vested in persons other than the governor.50 These other titles may be referred to as equitable titles.51 This equitable title is provided in sections 34(2) and 36(2), which preserve the rights of the possession, occupation and enjoyment of land both in urban and rural areas. Other scholars aver that section 1 of the LUA was not meant to divest landholders of the ownership of the land, and that section 28 will not in any case empower the governor in the matter of the revocation of rights, if the ownership of the land is truly transferred to the governor.52 In Umezulike's view, what the citizenry still have is use rights.53

3.1.3 The private property rights school of thought

The "private property rights" school of thought is dominated by Omotola and Smith,54 with support from others.55 The "private property rights" school of thought states that the Act could not have nationalised land. Instead, evidence of individual ownership rights is well spelt out in the Act, although the alienation of an interest in land is encumbered. Section 1 of the LUA must be read with other sections of the LUA before the full meaning can be found.

The preamble to the LUA states that "All lands comprised in the territory of each state in the federation are hereby vested in the governor of that state, and such land shall be held in trust and administered for the use and common benefit of all Nigerians in accordance with the provisions of this Act"56 (emphases added). As such, the preamble to the LUA creates confusion and controversy. The use of the word "vest" in this preamble is indicative of the "vesting of the ownership" of all land in the governor of the state.57 Olawoye states that land cannot be held allodially since the promulgation of the LUA,58 although section 14 of the LUA stipulates that a holder of rights of occupancy enjoys exclusive rights against all persons except the governor. Such exclusive rights are relative and not absolute. Other lines of reasoning confirmed this: in Ogunola v Eiyekole,59Olatawura, JSC stated that "an owner of customary land remains the owner all the same even though he no longer is the ultimate owner. The owner of the land now requires the consent of the Governor to alienate his interests which hitherto he could do without such consent."60

3.1.4 The aspect of the underlying theory

The elements of the underlying theory are the attitude towards human and land rights, the justification for development, conceptual end state,61 and measures of success. These are used in this section to scrutinise the LUA -see Table 1.

Considering the literature reviewed and the primary objectives of the enactment of the LUA, it is observed that a human rights-based approach was not followed. This land policy was enacted by the military regime, which nationalised all land and placed it under the control of the governors of the respective states. According to Tanner, a human rights-based approach was considered in enacting Mozambique's 1995 Land Policy, in which existing local land rights were analysed. Although the process of enactment involved the setting up of a panel, a "broad consultation process involving a wide range of role players with interest in land"62was not considered in Nigeria's 1978 LUA. The LUA fails to take existing rights into account, but only recognises them by stating in section 34 that land held before the promulgation of the LUA is to be held as if the holder is a holder of statutory rights in land in urban area. Many of these existing rights have also been the subject of dispute because of the issuance of a certificate of occupancy by the governor to a different party entirely. See Adole v Gwar.63

The LUA is based on formalisation theory. This is so because the Act is a replica of colonial law as reflected in the land tenure law of 1962. The justification for the development arises from the formalisation theory, which may not be aligned to the needs of the people. With the introduction of the Nigerian land reform programme in 2009, it was observed that the provisions of the LUA were a significant constraint to the success of land reform.

Only alignment with the goals of the enactment can bring about the success required. The LUA has failed to achieve any of its objectives, which is interpreted as a lack of success. Sustainability can be ascertained based on the achievement recorded so far. Its interpretation, implementation, and enforcement are deficient. Several court decisions have interpreted the LUA. See Garuba Abioye v Saadu Yakubu on the issue of customary landlords and customary tenants.64 Several interpretations are ascribed to sections 1, 34 and 36 of the LUA, while the last two sections relate to transitional provisions of land in urban and non-urban areas. As per Olatawura, JSC, with reference to section 36(2) and (3): "The time has come now for the comprehensive review of the LUA",65 but the implementation by the executive is deficient. These deficiencies also hinder success.

Concerning the customary ownership of land, the human and land rights elements of the underlying theory in customary areas are not ascertained because there is confusion on the topic of ownership. One school of thought believes that the implementation of the act is good, while the second school of thought believes that the implementation of the act is poor.

3.2 The change process

3.2.1 Customary land tenure, customary law and received English law

Sections 34 and 35 of the LUA convert absolute ownership into rights of occupancy, which can be enjoined through statutory or customary rights. Thus, customary rights are recognised. Section 29(3) identifies a community chief or leader of the community as the person to whom compensation is payable upon the revocation of the rights of occupancy. Hence, the section recognises that land can still be held by a community, thus recognising customary tenure. Two characteristic features of customary land tenure are communal ownership and the unique position of the Obas (the community head in Yoruba culture), the Obis (the community head in Ibo culture), Chiefs (street heads), and heads of families.66 The general rule about traditional land ownership is that the community heads or family heads hold land in trust for people, and the preamble to the Act alludes to these two characteristics of customary law. Hence, because all land vests under the trusteeship of the governor of the respective state, the governor has stepped into the shoes of the community leaders (the Obas, the Obis, the Chiefs, and the heads of families). The consent of the governor must be provided before the alienation of any land in urban areas. This is similar to the customary law rule that the consent of community leaders is sought before land can be alienated.67

Section 50 defines an occupier to be a person using or occupying land lawfully under customary law. Considering other sections of the Act, such as Section 6(9), which empowers local government to grant customary rights of occupancy; section 21 says no transfer of such land can be done without the consent of the local government. Under the transitional provisions pertaining to land not in the urban area, Section 36(5) says that no such land can be sub-divided or laid out in plots; yet in practice the land is held by the people and sub-divided into plots. This is one of the major indicators that informality exists in land administration. The LUA seems more to be a law on paper than in application. If these provisions were to be strictly applied, then customary rights could not be enjoined under customary law, which inevitably would erode the position of customary leaders in consent and alienation.

In ensuring tenure security, justice that is all-inclusive is advocated (social justice) rather than justice that is exclusive (legal), because judges define customary law differently (see Olubodun v Lawal,68 Owoniyin v. Omotosho,69and Nwaigwe v Okere70). Financial status is an enabler and a lack of finances is an inhibitor of access to the formal courts, which are more accessible to the rich than to the poor. Section 46(4)(b)(i) of the 1999 Constitution empowers the National Assembly to make provision for poor citizens of Nigeria to enable them to engage the services of a legal practitioner. The Legal Aid Act makes provision for the poor to access legal services in civil and criminal cases.71 Yet accessing legal services remains a challenge for the poor.72

Legal justice is nothing more than the result of received English law. Hence the common, civil and customary laws should be given the same recognition in the administration of justice. This position is supported by Onnoghen, who read the lead judgement in Nwaigwe v Okere.73

It is also worth noting the provisions of the law recognising customary law. Firstly, customs are not recognised as law unless they are established through the state or can be proved as a fact.74 Secondly, it is necessary to note section 18(3) of the Evidence Act, which states that during a judiciary proceeding, customs cannot be enforced as law if they are contrary to public policy or not in accordance with natural justice, equity and good conscience.75 The rules of natural justice are in two forms: namely, all parties to a dispute must be heard, and no one should act as a judge in a case in which he is a party. In the Nigerian legal system what is equitable and of good conscience is not precise and has no specific definition.76 A major constraint to recognising customary law is the position taken in the statutes to the effect that customary law must not be incompatible with any written law within the jurisdiction of the court which is applying the customary law. The judicial decisions in Kopek v Ekisola77supported this position.

In providing social justice, the Ekiti State government recently established traditional palace courts in recognition of the role of traditional rulers in the administration of justice.78 We advocate in this paper that land in dispute under customary law should be subjected to traditional courts for social justice rather than formal courts. Two reasons are given for this: the cost of seeking justice in the formal courts, and the time taken.

3.2.2 The aspect of the change process

Three aspects of the change process in the conceptual framework are getting to the end state, the community/country context, and working together.79 These three aspects have ten elements (see table 1) that are used in this section to guide the assessment of the LUA.

One of the greatest challenges of the 1978 LUA is the designation of urban and non-urban areas. Sections 1, 2 and 3 spell out the powers of the governor relating to land in an urban area. Section 3 further states that on the order of the National Council of states, the governor will publish, in the Gazette, the areas designated as urban in each state. This provision means that all land according to the Act is non-urban unless gazetted by the governor. Section 51 of the LUA defines "urban areas" to mean such areas as are designated by the governor of each state. Without this demarcation of urban and non-urban the governor has no power of control and management of land as stipulated in section 2 of the LUA.80 In addition the LUA failed to specify the guidelines for demarcating an area as urban or non-urban. Many state governors are yet to designate areas that are urban. Others use the provisions of section 4 of the LUA, which allows the use of different laws based on the land tenure law of former Northern Nigeria or the various states' land laws to enforce the use of different criteria and guidelines in demarcating urban and non-urban lands. If sustainable land reform is to be achieved, it is necessary to have uniform guidelines for demarcating an area as urban or non-urban.81

The LUA was meant to address the gaps in Land Tenure Law of 1962 but several gaps are still in existence among which are the demarcation guidelines for urban areas. Existing customary land rights are not protected as legitimate. Instead, all the LUA aims to achieve is to convert freehold to leasehold, adopting a "replacement model" instead of an "adaptation model" (see the details of the proposed continuum of land reform theories).82 There is a need to protect customary land rights based on customary norms. The LUA recognises statutory and customary land rights only according to the provisions of the LUA, but in reality, there is little adherence to the provisions of the Act. Hence, there has been no attempt to build on existing practice. Community participation is important in land policy formulation because customary laws and historical backgrounds need to be considered. See the position of Olatawura, JSC in Abioye v Yakubu. This is when the interest of all can be promoted. The LUA lacks in this regard. It has been a military enactment to date. Hence, the outcome has no significance for land rights holders. There is thus less sustainability.83 Effective and sustainable engagement is absent.

Problems of implementation and problems inherent in the LUA have been identified.84 Political will is lacking in the implementation of the LUA. The LUA was enacted 40 years ago, which means that there has been enough time for the realisation of its goals. Although achieving an end state may take time,85 this 40-year period is deemed to be sufficient for the achievement of the Act's stated objectives.86

From a human rights perspective, every land rights holder should be entitled to compensation without discrimination.87 Ensuring equity means acknowledging all stakeholders' needs. Disputes emanating from the payment of inadequate compensation are not heard in any court in Nigeria because of the provisions in the Act. The Land Use and Allocation Committee (LUAC) is the only committee allowed to entertain such disputes. This section of the Act infringes on the fundamental human right to be granted a fair hearing by a court or tribunal established by law, as stipulated by section 36(1) of the 1999 Constitution. The LUAC is not qualified as a court or a tribunal because the LUAC is constituted by the governor of each state in Nigeria. The governor is empowered to revoke the rights of occupancy in cases of overriding public interest, and is mandated to pay compensation. In the event of the payment of inadequate compensation, the governor whose act has been complained of is indirectly the judge in his own case. This is against the rule of natural justice and good conscience and negates the provision of section 46 of the Nigerian Constitution. Hence, the dispute resolution mechanisms are not appropriate and acceptable to all stakeholders. An alternative dispute resolution mechanism that is affordable to the poor should be considered instead.

None of the land rights holders interviewed (see section 2) were aware that LUA exists, and only one out of three community heads interviewed was aware of its existence. All the heads of the formal institutions were aware that the LUA exists. This law could be characterised as law on paper, but it does not ensure tenure security, easy title registration or land accessibility in customary areas.

The overall perception of all the respondents as expressed in their responses to the questionnaire was that land is not affordable. They believe that despite the promulgation of the LUA, land speculators are still operating in land transactions. The majority of the respondents said that land is not readily available for the citizenry. The control and management of land by the governor was applauded by the majority of respondents, who were of the opinion that the governor had been able to control and manage land as stipulated by LUA. The Act negates the rule of a fair hearing in determining disputes arising from the payment of compensation.

3.3 The change drivers

3.3.1 The LUA and compensation provisions

Compensation arises from the compulsory acquisition of private or public properties in the overriding public interest. Sections 28 and 29 make provision for the conditions requisite for compulsory acquisition and compensation payments.88 Section 28 empowers the governor to revoke rights of occupancy; and section 29 requires the same governor to pay compensation on the revocation of rights to land. The question to be answered is whether the due process is followed in the compulsory acquisition and whether adequate compensation is paid. The latter refers to compensation to be paid on un-exhausted improvements on the land, which means compensation is not paid on land without improvement.89 Section 30 of the LUA refers disputes about the compensation payable to the LUAC. This section of the Act contravenes natural justice, which requires that you must not be a judge in a case to which you are a party. The governor pays the compensation and appoints the committee member. The governor is indirectly a judge in a case in which he is a party. The issue of compensation payable under the Act may not be heard in any court in Nigeria because of the provisions of the Act. This negates the relevant provision of the Nigerian Constitution. Several authors clamour for the review of this section.90

Otubu91 notes that land had no commercial value before the LUA other than that related to improvements on the land. However, section 29(4) (a) states that compensation is payable on the land to an amount equal to the rent, if any, paid by the occupier during the year in which the right to occupancy was revoked. The divide between the amount of the rent and the commercial value of the land is of concern. The LUA indicates that compensation is to be paid separately for crops and buildings.92 There are instances where compulsory acquisition is done without compensation. This is referred to as penal revocation. This includes the situation where a person issued with a certificate of occupancy refuses to pay or accept such a certificate,93 where there is a breach of the terms contained in the certificate,94 and where land rights-holders alienate their rights of occupancy without the requisite consent of the governor.95 This revocation on the grounds of alienation without the governor's consent is extended to the deemed grant of rights of occupancy, as can be observed in Savannah Bank Ltd v Ammel Ajilo.96Constitutional backing for this provision is to be found in section 44(2) of the 1999 Constitution, which states that nothing in subsection (1) of this section shall be construed as affecting any general law. The backing of both the LUA and the Nigerian Constitution in this regard may affect tenure security. Sections 21 and 22 of the LUA have created difficulty in land transactions because of the provisions relating to consent.

Many judicial decisions support this section of the LUA, namely CCCTS Ltd v Ekpo,97and UBN Plc v Astra Builders Ltd.98Section 26 of the LUA states that any sale without the governor's consent is null and void. A review of this section in terms of removing the governor's consent in order to ease land transactions is repeatedly suggested in the literature.99

We propose that the entirety of section 47(1)(a), (b) and (c) should be expunged from the Act as it is not in conformity with the provisions of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Subsection (1) states that the "Act shall have effect notwithstanding anything to the contrary in any law or rule of law including the Constitution of the Federation or of a State." The Act disallows the jurisdiction of any court in Nigeria from enquiring into any question in respect of the powers of the governor pertaining to the vesting of all land in the state and the granting of statutory occupancy. The same applies to the local government.

3.3.2 The aspect of change drivers

Two aspects of the change drivers in the conceptual framework are demand and supply.100 Only the aspect of demand will be considered here. It has two major elements: deficiencies and pressure.101 The deficiencies are dealt with in this section. The main driver of change giving rise to the enactment of the 1978 LUA was the desire to unify the land tenure system in Nigeria. The reform was to have a direct impact on land use, land value and land development. Four decades of its operations have caused many distortions in LAS in Nigeria. The land market has been mainly informal and land is not affordable. Litigation, the inequitable distribution of land and inefficient LAS are on the increase.

With reference to table 1, deficiencies in the existing system are noted as drivers of change processes. A major deficiency of the Nigerian land administration system is the inability of the LUA to achieve its main objective of unifying the land tenure system. This is causing distortions to land use, land value and land tenure and prompted the genesis of the land reform programme that was initiated in 2009. Most respondents expressed the opinion that politics affects the implementation of the Act. This is an indication of bad land governance because politicians are policy makers responsible for deciding "what should be done to promote the public good, and then to make it happen".102 Policy makers should also rally public support if they are determined to implement such policy.103

3.4 Land administration system

3.4.1 The LUA and tenure security

One of the central objectives of the LUA is to make land readily available at an affordable rate to all Nigerians. The stated objectives of the LUA have not been achieved because of the problems inherent in the LUA and the problem of implementation.104 The problems inherent in the LUA are the lack of implementation guidelines, the entrenchment of the LUA in the Constitution, the inalienability of land in rural areas, the vesting of all land for the use and collective benefit of Nigerians only, inadequate compensation provisions, compensation outside the jurisdiction of courts, clarity regarding rights to land for grazing purposes, and the age of the Act. The problem of implementation lies in the abuse of power by the governor, the inefficient public service and too much bureaucracy, and a lack of political will. Institutional weakness is seen as the cause of the astronomical rise in land value and the increase in land speculation in Nigeria.105

3.4.2 The aspect of land administration system

Three aspects of the LAS in the conceptual framework are pro-poor land policy, the strategic level and the implementation level.106 Only the implementation level will be considered here. It has three major elements: improving tenure security, land recording and registration mechanisms, and good land governance.107 The process of formulating policy and legislation should include community participation. This was not done for the LUA of 1978, which was promulgated by the military government and entrenched in the constitution of Nigeria to avoid review. For the connection between policy and the needs of the people, the customary needs, norms and values must be part of the process of policy legislation.108 This is when the significance and success of outcomes for the community can be measured. Hence, the sustainability of the policy is improved.

Improving tenure security entails improving legitimacy, legality and certainty.109Legitimacy can be measured using material evidence in the form of records of rights, restrictions and responsibilities (RRRs) in land transactions and demarcation using beacons or any other visible markers, while legality refers to the use of formal law to protect RRRs and transactions in land.110 Certainty exists when there is an absence of corruption, conflict and natural disasters, and power is not abused.111 Legitimacy and legality are achieved by virtue of the existence of the LUA for the majority of urban residents. Certainty has never been achieved through the LUA, because all land rights holders can be affected by disputes or conflicts.

The LUA is based on a formal land registration system, yet less than 3% of Nigerian land is registered.112 The aim of the LUA is to create a uniform LAS in Nigeria. The result of each state's enacting different land registration laws is fragmentation in the LAS, creating non-uniformity in the administrative structures and land registration processes. Hence, there are as many dissimilar or contrasting LASs as there are states.113 For example, the introduction of the electronic document management system (EDMS) in Lagos, Nigeria improved land registration and public confidence in transactions. It centralised and consolidated file storage, and reduced the waiting time for obtaining land information. This has not reduced the frequency of land disputes, however, and neither has it increased the number of applications processed. However, it has increased the revenue generated by the government. This means that the government continues to generate revenue from land registration at the expense of ensuring tenure security.114 When measuring the success of the LUA based on the achievement of its objectives, the indications are that it has failed.115 For the LUA to be sustainable, pro-poor policies must be a primary objective, because the majority of Nigerians are peasant farmers who require secure access to land. For the land registration system to benefit the rural poor, alternative approaches to land registration/recording must be included in the LUA.

The interviewees were asked five questions relevant to the impact of the LUA on the customary land tenure system. Based on the responses received, the respondent believed that they understood the LUA. The impact of the LUA on the customary land tenure system is therefore analysed on the basis of their views. Two schools of thoughts emerged: some respondents thought that the Act had abolished customary ownership while the others disagreed with the statement that the Act had abolished the customary ownership of land. Although customary ownership continues to exist in reality, the people do not own their land according to the law, which requires that the land belong to the state. The results show that it has been difficult to secure title to customary land since the promulgation of the LUA. The general perception of the respondents is that customary ownership comprises a combination of communal ownership, family ownership and ownership where the head of the family has supreme power. It is shown that the system of ownership of customary land is not clearly defined by the LUA. 72,2% of the respondents agree that ownership of customary land is not clearly defined.

This view is supported by the polemic generated by judicial opinions on the interpretation of section 1 vis-a-vis customary owners. For example, in Garuba Abioye v Saadu Yakubu116the trial court asserted that the LUA did not intend to rob customary landlords of their rights, as contended by customary tenants.117 In the court of appeal the decision of the trial court was reversed. Akpata, JCA read the lead judgement, Wali and Maidama, JCA concurred that the rights of customary landholders are eroded by the provisions of section 1.118 The Court of Appeal asserted that the LUA eroded the rights of customary owners to Isakole. Isakole is the money paid by a customary tenant to the customary landlord who has granted the former permission to use the land for farming activities. Inviting the participation of 24 amici curiae, which included all attorneys-general in the country and five senior advocates of Nigeria (SAN), and taking into account the discussion of the learned counsels, a bench of seven Supreme Court judges expressly stated that the LUA had not abolished existing rights or interests in land. Bello, CJN gave the lead judgement. This is the state of confusion in the law, where courts on different levels use their discretion and express opinions on the interpretation of the law.

All the areas of the law examined above show that land rights are not recognised and protected. Achieving a pro-poor land policy requires existing land rights to be recognised and protected. This is when significant land tenure will be delivered to land rights-holders. The majority of the respondents agreed that the LUA negates our presidential system of government. The majority are of the opinion that the decision not to grant certificates of occupancy to people below the age of 21 is age-biased. The majority agreed that the power granted to the governor by the LUA is unnecessary. As regards the compensations provisions in the LUA, the respondents agreed that compensation provisions need to be reviewed: 35,3% agreed that the composition of the LUAC is acceptable while 57,1% disagreed. 35,7% agreed that the composition of the Land Allocation and Advisory Committee (LAAC) is acceptable while 55,2% disagreed.

4 Conclusion and recommendations

4.1 Recommendations

1. It is recommended that the LUA be reviewed, particularly in the areas examined in this study. This will also include considering the local context in which the law will be applicable. The primary aim of the new land policy should be to ensure tenure security for all land rights-holders in Nigeria.

2. Upon the review of the LUA, it is essential that the implementation procedures be included as regulations in the Act.

3. The various sections of the Act need a holistic review by a group of people consisting of academics, land professionals and civil servants.119The land policy needs to be reviewed so that it may achieve the sustainable development goals of ensuring tenure security for the rural poor.

4. In developing a pro-poor land administration system, it is recommended that the government should not lay emphasis on the formal LAS alone but should holistically consider alternative approaches to the land registration system. The approach of "delimitation" and "demarcation" in Mozambique would be a useful model to consider.120

5. As Nigeria comprises diverse cultures, it is questioned whether a single land policy is appropriate to serve the entire country. It is advocated that land policy should consider the local situation of the rural poor. Hence the enactment of land laws should be based on pro-poor policies. A single land law with different statutes for different cultures is advocated.

6. Compulsory acquisition under the LUA should be subjected to the oversight of a land commission to avoid the governor using executive power against the opposition party. An example of such malpractice is the current "National Grazing Reserve Bill 2016", which sought to acquire land indiscriminately in the interest of a particular group of people.121

4.2 Conclusion

The aim of this study has been to assess the effects of the LUA on customary tenure security in Nigeria. This was achieved by examining critical areas of the LUA (see section 3). The associated objectives were to appraise the LUA in terms of its effects on customary land tenure and to examine the areas which affect tenure security and establish those which need to be reviewed. Following the assessment of the effects of the LUA on tenure security, recommendations have been made.

A full evaluation of the LUA has not been conducted, because the aim of the research was to measure the tenure security of the rural poor. Hence, areas having to do with tenure security were evaluated. The research findings provide some conclusions about the LUA of 1978, which are based on the analysis carried out. Considering the objectives of the Act, its implementation is unsatisfactory. Many sections of the Act do not take the needs of the rural poor into account and are confusing and contradictory.122Hence the following recommendations are made.

Recommendation 1 is fundamental to this research. We propose that a new, pro-poor policy be enacted. Recommendation 2 concerns the implementation problem in the LUA. This should be solved by generating implementation guidelines during the review process. There is confusion about who owns the land. The people claim that they own their land while the Act transfers ownership to state governments. The relationship between the rights of those who live on the land the rights of the government should be well defined in the Act (see recommendations 1, 2 and 3). The formal land registration system is relied upon for title registration in Itaji-Ekiti, which is not in the interest of the rural poor. Security of title has been found to be difficult to attain since the promulgation of the Act. Recommendation 4 calls for the need to develop alternative approaches to land registration. In order that the Act should fulfil its objectives, an important objective would be making land readily available at an affordable rate. This objective has not been fulfilled.

Recommendation 5 calls for the enactment of a land policy that incorporates the customary norms of the people, and notes that a single land policy may not be appropriate for Nigeria. Recommendation 6 concerns the establishment of a land commission to supervise the committees as well as the governor in discharging their responsibilities. The opinions of the respondents indicate that it is not desirable for land to be vested in the government. The composition of the two committees (the LUAC and the LAAC) is inadequate. The LUAC excludes a professional land surveyor, while the LAAC excludes the customary leader. The respondents' view was that the decision not to grant a certificate of occupancy to people below the age of 21 is age-biased. The enormous power given to the governor is unnecessary because such power may be abused.

According to the findings of this research, the land speculation is on the increase. This is a significant sign of bad governance in land administration. The land speculators operate in the informal land market. Government control and management of land are not satisfactory at all. This is evident from the discussion so far. The land is placed in the hands of a few elites who have the economic power to acquire such. These elites take advantage of the populace who are in dire need of land, and they sell it at a very high price.

The provision of the Constitution which disallows any court to entertain any issues resulting from the inadequate payment of compensation negates the presidential system of government in which the judiciary is a separate arm of government. The judiciary is the private man's hope of getting justice, when injustice is meted out to him.

Bibliography

Literature

Abugu U Land Use and Reform in Nigeria: Law and Practice (Immaculate Prints Abuja 2012) [ Links ]

Adeniyi PO Improving Land Sector Governance in Nigeria: Implementation of the Land Governance Assessment Framework (World Bank Group Washington DC 2011) [ Links ]

Aluko BT and Amidu AR "Women and Land Rights Reforms in Nigeria" in International Federation of Surveyors 5th International Federation of Surveyors Regional Conference: Promoting Land Administration and Good Governance (8-11 March 2006 Accra) 1-13 [ Links ]

Aluko O "The Effects of Land Use Act on Sustainable Housing Provision in Nigeria: The Lagos State Experience" 2012 JSD 114-122 [ Links ]

Amokaye, OG "The Impact of the Land Use Act upon Land Rights in Nigeria" in Home R (ed) Local Case Studies in African Land Law (PULP Pretoria 2011) 59-78 [ Links ]

Arko-Adjei A Adapting Land Administration to the Institutional Framework of Customary Tenure: The Case of Peri-urban Ghana (PhD-dissertation Delft University of Technology 2011) [ Links ]

Atilola O "Land Administration Reform Nigerian: Issues and Prospects" in International Federation of Surveyors Congress 2010: Facing the Challenges - Building the Capacity (11-16 April 2010 Sydney) 1 -16 [ Links ]

Atilola O "Systematic Land Titling and Registration in Nigeria: Geoinformation Challenges" in International Federation of Surveyors Working Week 2013: Environment for Sustainability (6-10 May 2013 Abuja) 1-13 [ Links ]

Babalola KH and Hull SA "Using the New Continuum of Land Rights Model to Measure Tenure Security: A Case Study of Itaji-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria" 2019 SAJG 84-97 [ Links ]

Babalola SO et al "Possibilities of Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) Implementation in Nigeria" 2015 ISPRS Annals 155-163 [ Links ]

Bazoglu N et al Monitoring Security of Tenure in Cities: People, Land and Policies (UN-Habitat Nairobi 2011) [ Links ]

Chikaire JU et al "Land Tenure Reform: A Vehicle for Achieving Agricultural Transformation Agenda in Nigeria" 2014 MRJASSS 114-122 [ Links ]

De Soto H The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (Bantam Press New York 2000) [ Links ]

Emeka N, Famobuwa OS and Chinemeze I "Land Reform System and Its Implications on Agricultural Production in Nigeria" 2017 UJAR 338-343 [ Links ]

Fekumo JF "Does the Land Use Act Expropriate? A Rejoinder" 1988/89 JPPL 5-20 [ Links ]

Franco JC "A Framework for Analyzing the Question of Pro-poor Policy Reforms and Governance in State/Public Lands: A Critical Civil Society Perspective" in FIG/FAO/CNG International Seminar on State and Public Sector Land Management (2008 Verona) 1 -47 [ Links ]

Garner BA Black's Law Dictionary 9th ed (West Holmes, Minn 2009) [ Links ]

Goodin, Rein and Moran "The Public and its Policies"Goodin RE Rein M and Moran M "The Public and its Policies" in Goodin RE Rein M and Moran M (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy (Oxford University Press 2006) 3-35 [ Links ]

Hull S and Whittal J "Towards a Framework for Assessing the Impact of Cadastral Development on Land Rights Holders" in International Federation of Surveyors Working Week 2016: Recovery from Disaster (2-6 May 2016 Christchurch) 1-27 [ Links ]

Hull S and Whittal J "Human Rights in Tension: Guiding Cadastral Systems Development in Customary Land Rights Contexts" 2017 Survey Review 117 [ Links ]

Hull S and Whittal J "Filling the Gaps: Customary Land Tenure Reform in Mozambique and South Africa" 2018 SAJG (AfricaGEO 2018 Special Ed) 103-117 [ Links ]

Ibiyemi A "Making a Case for Review of the Land Use Act: A Focus on Claims for Compensation in the Rural Areas" 2014 LSPJT 216-235 [ Links ]

James RW Nigerian Land Use Act: Policy and Principles (University of Ife Press Ile-Ife 1987) [ Links ]

Kingston K and Oke-Chinda M "The Nigerian Land Use Act: A Curse or a Blessing to the Anglican Church and the Ikwere Ethnic People of Rivers State?" 2017 AJLC 147-158 [ Links ]

Myers WG Land and Power: The Impact of the Land Use Act in Southwest Nigeria (PhD-dissertation University of Wisconsin-Madison 1991) [ Links ]

Nelson M "Dynamics in Nigerian Land Administration System" in Research Association for Interdisciplinary Studies Conference Proceedings (10-11 June 2019 London) 245-250 [ Links ]

Nuhu MB "Compulsory Purchase and Payment of Compensation in Nigeria: A Case Study of Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Abuja" 2008 NJSRER 102126 [ Links ]

Nwabueze RN "Alienations under the Land Use Act and Express Declarations of Trust in Nigeria" 2009 JAL 59-89 [ Links ]

Nwapi C "Land Grab, Property Rights and Gender Equality in Pluralistic Legal Orders: A Nigerian Perspective" 2016 AJLS 124-146 [ Links ]

Nwocha ME "Impact of the Nigerian Land Use Act on Economic Development in the Country. Land Tenure in Nigeria Prior to the Land Use Act" 2016 BLR 430-442 [ Links ]

Ojigi LM "An Evaluation of the Efficiency of the Land Use Act 1978 of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and its Implications in Minna and Environs" in International Federation of Surveyors Knowing to Manage the Territory -Protect the Environment - Evaluate the Cultural Heritage (6-10 May 2012 Rome) 1-15 [ Links ]

Okafor B and Nwike E "Effects of the Land Use Act of 1978 on Rural Land Development in Nigeria: A Case Study of Nnobi" 2016 BJES 1-16 [ Links ]

Olawoye CO "The Statutory Shaping of Land Law and Land Administration up to the Land Use Act" in The Land Use Act: Report of a National Workshop (25 May 1981 Lagos) 14-22 [ Links ]

Olong MA and Ogwo B Land Laws in Nigeria 3rd ed (Faith Printers International Lokoja 2013) [ Links ]

Omotola JA "The Land Use Act and Customary System of Tenure" in The Land Use Act: Report of a National Workshop (1982 Lagos) 35-41 [ Links ]

Omotola JA "Does the Land Use Act Expropriate?" 1985 JPPL 1-20 [ Links ]

Otubu AK "Land Reforms and the Future of Land Use Act in Nigeria" 2007 NCLR 126-143 [ Links ]

Otubu AK "Private Property Rights and Compulsory Acquisition Process in Nigeria: the Past, Present and Future" 2012 AUDJ 5-29 [ Links ]

Otubu AK "The Land Use Act and Land Administration in 21st Century Nigeria: Need for Reforms" 2018 JSDLP 81-108 [ Links ]

Place F, Roth M and Hazell P "Land Tenure Security and Agricultural Performance in Africa: Overview of Research Methodology" in Bruce J and Migot-Adholla S (eds) Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa (Kendall/Hunt Dubuque, Iowa 1994) 15-39 [ Links ]

Simbizi DMC Measuring Land Tenure Security: A Pro-Poor Perspective (PhD-dissertation University of Twente 2016) [ Links ]

Simbizi DMC, Bennett RM and Zevenbergen JA "Land Tenure Security: Revisiting and Refining the Concept for Sub-Saharan Africa's Rural Poor" 2014 LUP 231-238 [ Links ]

Smith IO Practical Approach to Law of Real Property in Nigeria 2nd ed (Ecowatch Lagos 2007) [ Links ]

Thontteh EO and Omirin MM "Land Registration within the Framework of Land Administration Reform in Lagos State" 2015 PRPRJ 161-177 [ Links ]

Uchendu VC "State, Land, and Society in Nigeria: A Critical Assessment of Land Use Decree 1978" 1979 JAS 62-88 [ Links ]

Ukaejiofo A "Perspectives in Land Administration Reforms in Nigeria" 2008 JOE 43-50 [ Links ]

Umezuruike NO The Land Use Decree, 1978: A Critical Analysis (FAB Education Books Jos 1989) [ Links ]

Weinberg T The Contested Status of 'Communal Land Tenure' in South Africa (Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Cape Town 2015) [ Links ]

Whittal J "A New Conceptual Model for the Continuum of Land Rights Model" 2014 SAJG 13-32 [ Links ]

Williamson O "The New Institutional Economic: Take Stock, Looking Ahead" 2000 JEL 595-613 [ Links ]

Yamane T Elementary Sampling Theory (Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1967) [ Links ]

Yin RK Case Study Research 4th ed (Sage Los Angeles, CA 2009) [ Links ]

Case law

Adole v Gwar 2008 11 NWLR Pt 1120

Garuba Abioye v SAADU Yakubu 1991 NWLR Pt 190

CCCTCS Ltd v Ekpo 2008 6 NWLR Pt 1083

Kopek v Ekisola 2010 41 NSCQR 553

Nkwocha v Governor of Anambra State 1984 NLR 324

Nwaigwe v Okere 2008 34 NSCQR Pt II

Ogunola v Eiyekole 1990 4 NWLR Pt 146

Olubodun v Lawal 2008 35 NSCQR 570

Owonyin v Omotosho 1961 2 NLR 304

Savannah Bank Ltd v Ammel Ajilo 1989 1 NWLR Pt 97

UBN Plc v Astro Builders Ltd 2010 5 NWLR Pt 1186

Legislation

Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999

Evidence Act, CAP E14 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2010

Legal Aid Act, 2011 CAP A2 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004

Nigeria Land Use Act, 1978 CAP L5 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004

Internet sources

Anonymous 2019 Ekiti Government Approves 'Palace Courts' in Ekiti State https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/ssouth-west/322643-ekiti-govt-approves-palace-courts.html accessed 19 July 2019 [ Links ]

Aribigbola A 2007 Urban Land Use Planning, Policies and Management in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Empirical Evidence from Akure, Nigeria https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3ded/0079083551f27741faf539db74760ff88813.pdf accessed 20 August 2018 [ Links ]

Banire MA date unknown Customary Tenancy and the Land Use Act: A Critical Review http://mabandassociates.com/pool/Customary_tenancy_and_land_use_act.pdf accessed 24 August 2018 [ Links ]

Cotula L, Toulmin C and Quan J 2006 Better Land Access for the Rural Poor: Lessons from Experience and Challenges Ahead http://www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpadocs/Better_Land_Access_for_the_Rural_Poor_FAO.pdf accessed 12 September 2019 [ Links ]

Department for International Development 2007 Land Better Access and Secure Rights for Poor People http://mokoro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/dfid_land_policy_paper_2007.pdf accessed 6 August 2018 [ Links ]

IndexMundi 2017 Nigeria: Population https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/nigeria/population accessed 7 August 2018 [ Links ]

Kolawole Y 2013 97.5% of Nigeria's Land not Registered - Presidential Committee https://www.vanguardng.com/2013/02/97-5-of-nigerias-land-not-registered-presidential-committee/ accessed 4 February 2013 [ Links ]

Mabogunje AL 2010 Land Reform in Nigeria: Progress, Problems and Prospects http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf accessed 2 August 2018 [ Links ]

National Bureau of Statistics 2016 Statistical Report on Women and Men in Nigeria 2015 https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/491 accessed 8 August 2018 [ Links ]

Nigerian Law Today 2017 Grazing Bill and the Right to Property in Nigeria: A Voice of Reason http://nigerianlawtoday.com/the-grazing-bill-and-the-right-to-property-in-nigeria-a-voice-of-reason accessed 21 June 2018 [ Links ]

Norfolk S and Bechtel P 2013 Land Delimitation and Demarcation: Preparing Communities for Investment: Report for CARE-Mozambique http://gender.careinternationalwikis.org/_media/care_land_report_final_jan13.pdf accessed 11 September 2019 [ Links ]

Ogundele K 2017 Ekiti Monarch Laments Killings over Land Dispute, Urges Fayose, IG to Intervene Ado-Ekiti http://punchng.com/ekiti-monarch-laments-killings-land-dispute-urges-fayose-ig-intervene/ accessed 11 September 2019 [ Links ]

Otubu AK 2014 Compulsory Acquisition without Compensation and the Land Use Act https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420039 accessed 10 September 2019 [ Links ]

Otubu AK 2015 The Land Use Act and Land Ownership Debate in Nigeria: Resolving the Impasse https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2564539 accessed 10 September 2019 [ Links ]

Rasak SE 2011 The Land Use Act of 1978: Appraisal, Problems and Prospects https://docplayer.net/54260775-The-land-use-act-of-1978-appraisal-problems-and-prospects.html accessed 1 October 2018 [ Links ]

Sen A 2000 Social Exclusion: Concept, Application, and Scrutiny https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29778/social-exclusion.pdf accessed 6 August 2018 [ Links ]

Sida 2004 Strategic Guidelines for Sida Support to Market-Based Rural Poverty Reduction Improving Income among Rural Poor https://www.sida.se/contentassets/a8303f32cc174d9ca827fa03a67aabdb/improving-income-among-rural-poor_1286.pdf accessed 6 August 2018 [ Links ]

Tanner C 2002 Law-making in an African Context: The 1997 Mozambican Land Law http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/legal/docs/lpo26.pdf accessed 20 September 2018 [ Links ]

United Nations 2015 Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf accessed 20 September 2018 [ Links ]

UN-Habitat 2008 Secure Land Rights for All http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/getElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=2488&alt=1 accessed 18 June 2018 [ Links ]

United States Agency for International Development date unknown Country Profile: Property Rights and Resource Governance - Nigeria https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_Nigeria_Profile.pdf accessed 13 September 2019 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

AJLC African Journal of Law and Criminology

AJLS African Journal of Legal Studies

AUDJ Acta Universitatis Danubius. Juridica

BJES British Journal of Environmental Sciences

BLR Beijing Law Review

DFID Department for International Development

EDMS Electronic Document Management System

JAL Journal of African Law

JAS Journal of African Studies

JEL Journal of Economic Literature

JOE Journal of the Environment

JPPL Journal of Private Property Law

JSD Journal of Sustainable Development

JSDLP Journal of Sustainable Development Law Policy

ISPRS Annals ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences

LAAC Land Allocation and Advisory Committee

LAS Land Administration System

LFN Laws of the Federation of Nigeria

LSPJT Lagos State Polytechnic Journal of Technology

LUA Land Use Act of 1978

LUAC Land Use and Allocation Committee

LUP Land Use Policy

MLHUD Ministry of Land Housing and Urban Development

MRJASSS Merit Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Soil Sciences

NBS National Bureau of Statistics

NCLR Nigerian Current Law Review

NJSRER Nordic Journal of Surveying and Real Estate Research

PRPRJ Pacific Rim Property Research Journal

RRRs Rights, restrictions and responsibilities

SAJG South African Journal of Geomatics

SDGs United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

SDILJ San Diego International Law Journal

UJAR Universal Journal of Agricultural Research

UN United Nations

USAID United States Agency for International Development

Date Submission 20 November 2018

Date Revised 4 November 2019

Date Accepted 4 November 2019

Date published 25 November 2019

* Kehinde H Babalola. HND Surveying and Geoinformatics (SG) FPA PD (SG) FSS PGD (URP) FUTA, MSc (Eng) UCT. Registered Surveyor, (SURCON), Senior Technologist, Dept of SG, Federal Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State Nigeria. University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. E-mail: bblkeh001@myuct.ac.za. Many thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their input.

** Simon A Hull. BSc (Surveying) (UKZN) MSc (Eng) (UCT) PGCE (Unisa). Professional Land Surveyor, (SAGC) Senior Lecturer, School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town, South Africa. E-mail: simon.hull@uct.ac.za.

1 Babalola et al 2015 ISPRS Annals 156; USAID date unknown https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_Nigeria_Profile.pdf 56.

2 IndexMundi 2017 https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/nigeria/population_2.

3 NBS 2016 https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/491 1.

4 Okafor and Nwike 2016 BJES 1.

5 Otubu 2015 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2564539 9-11; Myers Land and Power 14, 28, 30-32, 52-55; Banire date unknown http://mabandassociates.com/pool/Customary_tenancy_and_land_use_act.pdf 114.

6 Kingston and Oke-Chinda 2017 AJLC 157.

7 Nwapi 2016 AJLS 141.

8 Aluko 2012 JSD 114.

9 Nwabueze 2009 JAL 69-79; Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 8.

10 Emeka, Famobuwa and Chinemeze 2017 UJAR 341-342; Chikaire et al 2014 MRJASSS 119-120; Nelson "Dynamics in Nigerian Land Administration System" 248.

11 Amokaye "Impact of the Land Use Act upon Land Rights in Nigeria" 66-67; Ibiyemi 2014 LSPJT; Otubu 2014 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420039 1-23.

12 Amokaye "Impact of the Land Use Act upon Land Rights in Nigeria" 66-67.

13 Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 8.

14 Mabogunje 2010 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf 9.

15 Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 8.

16 Mabogunje 2010 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf 17-20.

17 De Soto Mystery of Capital 27-29; Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 9.

18 Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 9-10.

19 Garner Black's Law Dictionary 443.

20 Place, Roth and Hazell "Land Tenure Security and Agricultural Performance in Africa" 19.

21 Weinberg Contested Status of 'Communal Land Tenure' 6; Bazoglu et al Monitoring Security of Tenure in Cities 5.

22 Sen 2000 https://www.adb.org/sites/default/fNes/publication/29778/social-exclusion.pdf_14.

23 Simbizi, Bennett and Zevenbergen 2014 LUP 231.

24 Simbizi, Bennett and Zevenbergen 2014 LUP 231.

25 UN 2015 https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf 15-18.

26 Franco "Framework for Analyzing the Question of Pro-poor Policy Reforms" 18-19.

27 UN-Habitat 2008 http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/getElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=2488&alt=1 2, 37.

28 Simbizi Measuring Land Tenure Security 80.

29 UN-Habitat 2008 http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/getElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=2488&alt=1 2, 37.

30 Sida 2004 https://www.sida.se/contentassets/a8303f32cc174d9ca827fa03a67aabdb/improving-income-among-rural-poor_1286.pdf 20; DFID 2007 http://mokoro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/dfid_land_policy_paper_2007.pdf 24-31.

31 Cotula, Toulmin and Quan 2006 http://www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpadocs/Better_Land Access for the Rural Poor FAO.pdf 7-8.

32 Cotula, Toulmin and Quan 2006 http://www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpadocs/Better_Land Access for the Rural Poor FAO.pdf 7-8.

33 USAID date unknown https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USA_ID_Land_Tenure_Nigeria_Profile.pdf 8.

34 Aribigbola 2007 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3ded/0079083551f27741faf539db74760ff88813.pdf 3.

35 Uchendu 1979 JAS; Omotola "Land Use Act and Customary System of Tenure" 40; Mabogunje 2010 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf 4-5, 20; Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 7-9; Rasak 2011 https://docplayer.net/54260775-The-land-use-act-of-1978-appraisal-problems-and-prospects.html 84-86; Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 199-216; Otubu 2014 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420039 18-19; Otubu 2015 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2564539 18-19; USAID date unknown https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_Nigeria_Profile.pdf 4.

36 Ogundele 2017 https://punchng.com/ekiti-monarch-laments-killings-land-dispute-urges-fayose-ig-intervene/.

37 Whittal 2014 SAJG 22.

38 Babalola and Hull 2019 SAJG 94.

39 Yin Case Study Research 86.

40 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 6-12.

41 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 6-12.

42 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 6-14.

43 Yamane Elementary Sampling Theory.

44 Olawoye "Statutory Shaping of Land Law" 5, 20; Omotola "Land Use Act and Customary System of Tenure" 35; Myers Land and Power 75-76; Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 19; Ojigi "Evaluation of the Efficiency of the Land Use Act" 3.

45 Otubu 2014 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420039; Otubu 2015 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2564539 8-10.

46 Nwabueze 2009 JAL 65.

47 Aluko and Amidu "Women and Land Rights Reforms in Nigeria" 6-10; Mabogunje 2010 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf 9, 20.

48 Nkwocha v Governor of Anambra State 1984 NLR 324.

49 Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 20.

50 Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 20.

51 Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 20-21.

52 Omotola 1985 JPPL 3; Fekumo 1988/89 JPPL 5.

53 Umezuruike Land Use Degree 5.

54 Omotola 1985 JPPL 3; Smith Practical Approach to Law of Real Property 70-71.

55 James Nigerian Land Use Act 33; Fekumo 1988/89 JPPL 5-20.

56 Preamble of the Land Use Act of 1978.

57 Olawoye "Statutory Shaping of Land Law" 18; Olong and Ogwo Land Laws in Nigeria 170-177; Rasak 2011 https://docplayer.net/54260775-The-land-use-act-of-1978-appraisal-problems-and-prospects.html 80-82.

58 Olawoye "Statutory Shaping of Land Law" 19.

59 Ogunola v Eiyekole 1990 4 NWLR part 146, 632.

60 Ogunola v Eiyekole 1990 4 NWLR 648.

61 It is the conceptual/imagined/envisioned end point/outcome of a development programme.

62 Hull and Whittal 2018 SAJG 108.

63 Adole v Gwar 2008 11 NWLR Pt 1120.

64 Garuba Abioye v Sa'adu Yakubu 1991 NWLR Pt 190.

65 Garuba Abioye v Sa'adu Yakubu 1991 NWLR Pt 190.

66 Omotola "Land Use Act and Customary System of Tenure" 35.

67 Omotola "Land Use Act and Customary System of Tenure" 35-37.

68 Olubodun v Lawal 2009 35 NSCQR 570.

69 Owoniyin v Omotosho 1961 2 NLR 304.

70 Nwaigwe v Okere 2008 34 NSCQR Pt II 1325.

71 Section 8 of the Legal Aid Act, 2011.

72 Nwocha 2016 BLR 435.

73 Nwaigwe v Okere 2008 34 NSCQR Pt II 1357.

74 Nwocha 2016 BLR 437.

75 Evidence Act, CAP E14 LFN, 2010.

76 Nwocha 2016 BLR 437.

77 Kopek v Ekisola 2010 41 NSCQR 553.

78 Anon 2019 https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/ssouth-west/322643-ekiti-govt-approves-palace-courts.html.

79 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 10.

80 Land Use Act, 1978 CAP L5 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004.

81 Otubu 2018 JSDLP 88-90.

82 Hull and Whittal "Framework for Assessing the Impact of Cadastral Development" 127.

83 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 11.

84 Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 199.

85 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 10.

86 Williamson 2000 JEL 596-598.

87 Arko-Adjei Adapting Land Administration 11.

88 Nuhu 2008 NJSRER 104-105; Ibiyemi 2014 LSPJT 221-228.

89 Otubu 2014 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420039 5, 22.

90 Otubu 2012 AUDJ 21-23; Nuhu 2008 NJSRER 104-105; Ibiyemi 2014 LSPJT 221228.

91 Otubu 2007 NCLR 132.

92 Section 29(4)(c) of the Land Use Act, 1978.

93 Section 28(5)(c) of the Land Use Act, 1978.

94 Section (28)(5)(a) of the Land Use Act, 1978.

95 Section 28(2)(a) of the Land Use Act, 1978.

96 Savannah Bank Ltd v Ammel Ajilo 1989 1 NWLR Pt 97 305.

97 CCCTS Ltd v Ekpo 2008 6 NWLR Pt 1083 369.

98 UBN Plc v Astra Builders Ltd 2010 5 NWLR Pt 1186 10.

99 Smith Practical Approach to Law of Real Property 228; Otubu 2018 JSDLP 105-108; Olong and Ogwo Land Laws in Nigeria 153.

100 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 7.

101 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 7.

102 Goodin, Rein and Moran "The Public and its Policies" 14.

103 Goodin, Rein and Moran "The Public and its Policies" 1.

104 Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 196; Nwocha 2016 BLR 102.

105 Nwocha 2016 BLR 126-127; Aluko 2012 JSD 119-120.

106 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 12.

107 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 12.

108 Hull and Whittal 2017 Survey Review 55.

109 Whittal 2014 SAJG 22.

110 Whittal 2014 SAJG 22.

111 Whittal 2014 SAJG 22.

112 Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 8-9, 15; Atilola "Systematic Land Titling and Registration in Nigeria" 2; Kolawole 2013 https://www.vanguardng.com/2013/02/97-5-of-nigerias-land-not-registered-presidential-committee/.

113 Ukaejiofo 2008 JOE 43.

114 Thontteh and Omirin 2015 PRPRJ 161.

115 Omotola "Land Use Act and Customary System of Tenure" 40; Mabogunje 2010 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf 4-5, 20; Atilola "Land Administration Reform" 7-9; Uchendu 1979 JAS; Rasak 2011 https://docplayer.net/54260775-The-land-use-act-of-1978-appraisal-problems-and-prospects.html 84-86; Abugu Land Use and Reform in Nigeria 199-216; Otubu 2014 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420039 18-19; Otubu 2015 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2564539 18-19; USAID date unknown https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_Nigeria_Profile.pdf 4.

116 Garuba Abioye v SA'ADU Yakubu 1991 NWLR Pt 190 30.

117 Garuba Abioye v SA'ADU Yakubu 1991 NWLR Pt 190 30.

118 Garuba Abioye v SA'ADU Yakubu 1991 NWLR Pt 190 9-10.

119 Tanner 2002 http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/legal/docs26.pdf 49.