Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.22 n.1 Potchefstroom 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a5681

ARTICLES

Prêt-à-Porter Procreation: Contemplating the Ban on Preimplantation Sex Selection

S Soni*

University of KwaZulu-Natal South Africa; sonish@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Preimplantation genetic testing makes it possible to genetically test in vitro embryos for the presence of genetic disease. It also identifies the sex of the embryo. Preimplantation sex selection is prohibited in a number of jurisdictions, including South Africa. Sex selection may be considered to be included in the ambit of the right to reproductive autonomy under the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. An analysis of international human rights law supports such a view, and a comparison with foreign law suggests that South Africa should be wary of adopting blanket prohibitions without considering their context. The analysis demonstrates that a prohibition of preimplantation sex selection may have no place in South African law.

Keywords: Sex selection; preimplantation genetic testing; preimplantation sex selection.

1 Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing (or PGT) refers to a variety of genetic testing methods which take the following forms: preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), preimplantation genetic testing for monogenetic disorders and HLA-typing (PGT-M), and preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR). All these methods have been indicated for use in in vitro treatment. They involve the identification of genetic disease at the embryonic level, and this allows individuals to exercise choice by screening against the selection of embryos which bear genetic characteristics which predispose them to developing serious diseases such as cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy. This article focusses on one of these methods, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy, or PGT-A, particularly for the purpose of the sex selection of the embryo which will be implanted for pregnancy.

Most jurisdictions have prohibited sex selection in the absence of genetic disease. In other words, they prohibit the selection of an embryo based on its sex, where that choice is based on non-therapeutic social reasons, or pure desire to have a child of a particular sex. Because PGT-A technology studies the genetic composition of an embryo, it inevitably reveals the sex of that particular embryo. This is beneficial where sex is a determining factor for genetic disease and the avoidance of genetic disease, as it allows prospective parents to ensure that their child will not possess a sex-linked condition by screening against those genetic characteristics.

This article examines existing regulatory approaches to using PGT-A for sex selection for non-therapeutic purposes by studying the framework of international, foreign and South African law. The article concludes with a determination and recommendation as to whether the prohibition of non-therapeutic sex selection is justified under South African law.

2 Sex selection

The normal male-to-female sex ratio should fall within a narrow scope of 104 to 107 boys to every 100 girls.1 Where these ratios are skewed in a population, this often suggests the use of sex-selective abortions or other sex-selective procedures.2 Sex selection refers to attempts to either choose or influence the sex of a child before pregnancy, and after birth (infanticide).3

Sex selection is generally prohibited in the absence of achieving a therapeutic benefit. In population groups which maintain a preference for a particular sex (usually male), sex selection is desired and employed to achieve that result. In some jurisdictions, the desire to select the sex of offspring may be based on a reason as simple as wanting to achieve balance in the family - so called family balancing.4 As controversial as the methods of selecting sex are the reasons for doing so. A state such as India, whose population demonstrates a cultural preference for sons, has suffered a skewed sex ratio in the general population as a result.5 The United Kingdom, which does not evidence such preference, does not currently bear that risk.6 The controversy of non-therapeutic sex selection is whether it is a choice which should be respected on the basis that it is an element of reproductive autonomy, or to prohibit it on the basis that it is a form of discrimination against women where it is exercised on the basis of the so-called "son preference". It has been argued that sex selection for this purpose can perpetuate the devaluation of daughters and women's inferior family and social status, and many countries have chosen to prohibit sex selection for this reason.7

The available data prepared by the Center for Genetics and Society shows that currently 36 countries have adopted national laws (or policies having the force of law) on sex selection.8 Of the thirty-six countries, none expressly permit sex selection, five prohibit sex selection for any reason, and the remaining thirty-one prohibit sex selection for non-therapeutic or social reasons. Twenty-five of these countries are European, eight are Asian, two are from Oceania, and one is from North America. Six countries' laws contain prohibitions which are explicitly articulated regarding sex selection practices. They are Canada, China, India, Israel, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Individuals seeking preimplantation sex selection often travel to countries such as the United States, Mexico, Italy and Thailand, where there is no ban on non-therapeutic sex selection. This phenomenon is called "reproductive tourism", where individuals travel for sex selection and general infertility treatments such as IVF.9

3 International human rights law

International human rights law attempts to balance two interests which have the potential to conflict with each other: the right to reproductive autonomy and the principle of non-discrimination. It provides for binding obligations upon States that have become party to the human rights treaties, which have an obligation to give due consideration to the human rights treaties to which they are signatory.10 These treaties often have implications for sex selection. Further, there is a legal obligation under international law to act in accordance with the principles of treaties which a State has ratified, and a positive obligation to incorporate those principles in the State's domestic law. International law, as a set of global values, can therefore form an important basis for an international strategy in relation to sex selection.11These norms also force States to address the underlying causes of sex selection, such as the low status of women in society.12 International law does not contain an express right to sex selection, however. Save for one express exception, it does not prohibit the practice either. It will be argued that international human rights law phrases rights in a manner which supports reproductive choice, and this could very well include a right to select the sex of one's offspring. Other rights provide a basis for recognising discrimination that may underlie sex selection.

3.1 The Biomedicine Convention

The right to reproductive autonomy exists in international law through a series of inter-related rights.13 These include the right to decide on the number and spacing of one's children, the right to private and family life, the right to liberty and the right to maternity protection.14 Of additional importance are the rights to health, information, and the benefits of scientific progress.15 While medical ethics and international law have developed as two separate legal disciplines, there are two international instruments which merge them together. The first is the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (the Biomedicine Convention), which expressly prohibits preimplantation sex selection in the absence of a medical reason.16Article 14 states that

The use of techniques of medically assisted procreation shall not be allowed for the purpose of choosing a future child's sex, except where serious hereditary sex-related disease is to be avoided.

3.2 The Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights17

Article 3 provides that human dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms must be fully respected, and the interests and welfare of the individual should have priority over the sole interest of science or society.18While the Declaration is of a more general nature and does not expressly refer to sex selection, it is suggested that its provisions support an individual's autonomous right to select the sex of their offspring. This submission is based on Article 45 which states that the autonomy of persons to make decisions while taking responsibility for those decisions and respecting the autonomy of others must be respected.19

3.3 The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

Article 8(1) of the ECHR states that everyone has the right to respect for his or her private and family life. If an individual can show interference with this right, then the onus is on the State in question to attempt to justify such interference under Article 8(2).20

3.4 The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The Charter enshrines several political, social, and economic rights for European Union (EU) citizens and residents in EU law. Few of its provisions relate to biomedicine. Article 3, which enshrines the right to integrity of the person, states that -

In the fields of medicine and biology, the following must be respected in particular:

(a) the free and informed consent of the person concerned, according to the procedures laid down by law,

(b) the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at the selection of persons,

(c) the prohibition on making the human body and its parts as such a source of financial gain, and

(d) the prohibition of the reproductive cloning of human beings.21

Like the ECHR, the Convention also protects the right to respect for an individual's private and family life, home and communications.22 Article 9 states that the right to marry and the right to found a family is guaranteed in accordance with the national laws which govern the exercise of these rights. The Convention also protects the right to equality, and specifically the right to equality between men and women.23 Discrimination, including discrimination based on genetic characteristics, is prohibited by Article 21, which prohibits discrimination on a number of grounds, including sex.

3.5 Other international documents

The Cairo Programme was adopted in 1994 by 185 member States of the United Nations at the United Nations Conference on Population and Development. It contains a definition of reproductive health which recognises the right of men and women to reproduce and to decide on the number of children they have. It is silent, however, on the right to determine their sex. It has been argued that the Declaration takes a stand against sex selection, as it identifies the problem of "son preference" of several countries and states that this is often compounded by the increasing use of technologies to determine foetal sex, resulting in the abortion of female foetuses.24 One of its policy objectives is to eliminate discrimination against female children and the causes of preference, which results in harmful and unethical practices regarding female infanticide and prenatal sex selection.25 It is worth noting that this policy objective expressly relates to sex-selective abortion and infanticide, and not generally or specifically to preimplantation sex selection.26 One possible reason for this is that the document predates preimplantation techniques.27 Toebes suggests that the fact that the Declaration refers to discrimination against girls in a general manner indicates that all forms of sex selection should be banned.28 In line with the Cairo and Beijing Declarations, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) recognises an equal right for men and women to choose the number and spacing of one's children, but not the sex.29

Some rights in international instruments support reproductive choice. For example, the right to privacy and family life may support the choice to terminate an unintended pregnancy. However, Toebes suggests that the overarching absence of express prohibitions on sex selection indicates that guidance may be sought from the findings of treaty monitoring bodies and international courts.30 It is argued that the choice to select the sex of one's offspring at the preimplantation stage is not only a part of reproductive autonomy but should fall within the ambit of the right to privacy. There are examples which support this view. The first is the General Comment on Equality of Rights between Men and Women by the Human Rights Commission, in which it was stated that when States impose a legal duty on doctors to report cases of women who have undergone a termination of pregnancy, this constitutes a violation of the right to privacy of the patient.31The Committee also recognised a violation of the right to privacy enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, where medical authorities refused to carry out a therapeutic abortion in Kl v Peru.32In the case of Brüggeman and Scheuten v Federal Republic of Germany, the former European Commission on Human Rights held that not every regulation of the termination of unwanted pregnancies would constitute an infringement of the right to privacy of the mother.33 As such, States which are party to the ECHR have a margin of appreciation when it comes to abortion legislation.

Toebes states that this creates an impression that there is no clear guidance in international law regarding the link between the right to privacy and the right to terminate pregnancy.34 She then links these findings with the issue of preimplantation sex selection, and concludes that international treaty bodies are far removed from deciding on an issue such as sex selection on the basis of a right to privacy.35 This may be an erroneous conclusion, bearing in mind that these decisions relate to the right to terminate a pregnancy, which is an existing gestation with a foetus in utero. Preimplantation sex selection, while it is still based on the issue of the right to choose between a desired and undesired sex of offspring, is not identical to the abortion issue. It is worthwhile to note that the approach of human rights bodies and the international courts has been to discourage and prohibit the discrimination which is perceived to underlie sex selection, rather than to guarantee the protection of the foetus.36 If the discrimination is not against an existing individual, can it actually be discrimination? It seems to be a massive intrusion on an individual's reproductive rights to prohibit preimplantation sex selection on the basis that we prohibit prenatal sex selection. Most countries have determined that termination of pregnancy is a constituent right to reproductive autonomy if performed within the prescribed legal limits. The legal limits serve as a dividing line between lawful and unlawful termination. If law can allow terminations within the legal limits, then surely it can distinguish between sex selection that is lawful and that which is not? It is argued that prenatal sex selection such as sex-selective abortion and infanticide should be prohibited. However, the choice to select sex at the preimplantation stage should not be restricted in any fashion.

4 Recommendations of the European Society of Human Reproduction37

Between the years 2001 and 2014 the ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law produced ethical statements on specific moral issues in the practice of ART. The articles were published in the ESHRE journal "Human Reproduction" after approval by the Executive Committee. In 2013 the Task Force published an article on sex selection for non-therapeutic reasons.38The Task Force was divided on the issue. One view was that non-therapeutic sex selection reflects discriminatory attitudes, and to allow it would be at odds with a human rights perspective based on equality between the sexes.39 The other view is that there is nothing inherently sexist about non-therapeutic sex selection, which finds the basis of the current ban unconvincing.40 ESHRE suggested that such an issue could be decided on the basis of evidence showing that non-therapeutic sex selection would lead to serious harm to the children who are born as a result, or would affeci society as a whole.41 ESHRE concluded that a revision of the ban on sex-selection was necessary, which would allow for sex selection for non-therapeutic reasons in conditions that take into account societal concerns about the possible impact of the practice.42 It supported the suggestion of the HFEA (in its 2003 report) that preimplantation sex selection should be allowed in a trial setting, which would involve proper pre-treatment implications, counselling, and the serious monitoring of all relevant aspects.43 A trial would "permit an assessment to be made of the extent and profile of demand for this service, and controlled follow-up of families involved, including the effects of selection on the subsequent treatment and long-term psychological development of the children".44

The Task Force concluded with the following recommendations:45

(a) Sex selection should be allowed in principle if aimed at avoiding offspring health risks.

(b) Centres offering flow sorting should commit themselves to careful monitoring and follow-up in order to provide data for assessing the longer-term safety of the technology.

(c) If the present ban on sex selection for non-therapeutic reasons is to be maintained, clarification is needed as to whether it applies to fulfilling parental requests for additional selection in the context of a medically indicated IVF/PGT procedure.

(d) If the arguments against a categorical ban are found convincing, there would still be a need for setting conditions defining the responsible use of sex selection for non-therapeutic reasons.

5 The South African legal framework

Access to reproductive technology such as PGT-A falls under the umbrella right to access to health and more specifically access to reproductive healthcare. Such rights are protected by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (hereinafter referred to as "the Constitution"), which provides the legal foundation for the existence of the Republic, sets out the rights and duties of its citizens, and defines the structure of the government.46 Patients' rights and legal provisions regarding healthcare are more specifically identified in the National Health Act 61 of 2003 (hereafter referred to as "the NHA"), which was assented to by the President on 18 July 2004, and came into force on 2 May 2005. The provisions of the NHA were promulgated over a period of time. Thus, some provisions of the NHA were applicable from that date, while others came into force only later. Chapter 8 of the NHA, titled "Control of use of Blood, Blood Products, Tissue and Gametes in Humans" is an example of such provisions, which became fully operational only in 2012. Until that time, matters pertaining to human tissues were legislated under the Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 (hereafter referred to as "the HTA"). The HTA was important in South African medico-legal history as it was an attempt to legislate for the use and control of human body tissues (including gametes). However, it had been drafted at a time when many of the cutting-edge scientific and medical practices which have now become part of routine medical practice today were still in their infancy or barely envisaged.47 These include, for example, much of assisted reproductive technology, cell-based therapy and tissue banks.48 Advances in other treatments such as blood transfusion, transplantation and genetic services that occurred subsequently were likewise not provided for in the HTA.49 The NHA therefore provided a welcome revision of legislation governing such treatments. The revision was not flawless, however. All of the sections of Chapter 8 have now been enacted: section 53 came into force on 30 June 2008; sections 55, 56 and 68 on 17 May 2012; and on 1 March 2012 the remaining sections 54 and 57-67 were enacted. Several sets of regulations pertinent to Chapter 8 have been published since 2012.

5.1 Reproductive autonomy and the South African Constitution

Several rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights protect reproductive rights, which protect the health and well-being of both men and women.50 They are also said to require access to voluntary, quality reproductive and sexual health information, education and services.51 Section 12 of the Constitution, which protects the right to freedom and security of the person, expressly identifies reproductive choice-making as an important element of the right. It provides that

Everyone has the right to bodily and psychological integrity, which includes the right to make decisions concerning reproduction.52

Reproductive rights in South Africa have traditionally focussed on the rights of individuals to avoid reproduction.53 However, with an increase in the use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), there has been a shift of focus from the rights of individuals to avoid reproduction to the rights of individuals to reproduce non-coitally.54 With the emergence of new technologies, reproduction by non-coital means is becoming more frequent, and the right to engage in these new technologies is becoming increasingly important.55

The crucial issue is whether such a right exists.56 The Constitutional Court decision in AB v Minister of Social Development suggests that it does, but only if the person claiming this right is physically involved in the reproductive process.57 In this case the Court was asked to decide on the constitutional validity of section 294 of the Children's Act 38 of 2005, which provides that an individual wanting to enter into a surrogate motherhood agreement must provide his or her gametes for the artificial fertilisation procedure by which the embryo is created. It was put to the Court that this section was unconstitutional on the basis that it violated several rights of individuals who were unable to provide their gametes for use, including the rights to reproductive autonomy and dignity. In order to deal with this argument, the Constitutional Court assessed the historic basis for the genetic link requirement. The Court referred to the report issued by the South African Law Commission in 1992 which recommended that surrogate motherhood agreements be permissible only if the gametes of at least one of the commissioning parents were used, so that the child is related to at least one of the commissioning parents.58 The Commission based this recommendation on the premise that it was necessary in order to promote the bond between the child and the commissioning parents, as well as being in the best interests of the child. The provision would also restrict undesirable practices such as "shopping around" with a view to creating children with particular characteristics.59

As pointed out in AB v Minister of Social Development,60in 1994 a parliamentary ad hoc committee recommended the retention of the requirement that the gametes of at least one of the commissioning parents be used towards conception or in the case of a single person, the gametes of that single parent. The rationale for this recommendation was that the use of both male and female donor gametes would result in a situation similar to adoption, as the child or children would not be genetically linked to the commissioning parent or parents. That situation would obviate the need for surrogacy, as the couple could adopt a child instead.61 The High Court made two important observations: the first was that social practices and norms constantly change and evolve and that the legislature must take cognisance of these changes.62 The second was that the SALC specifically recognised that individuals have the right to make certain decisions concerning reproduction and that a limitation of this right would constitute a violation of their rights to dignity and privacy.63 The Court felt that the underlying constitutional value that was of particular relevance was autonomy.64

In Barkhuizen v Napier the court defined autonomy as "the ability to regulate one's own affairs, even to one's own detriment", and as "the very essence of freedom and a vital part of dignity".65 In NM v Smith O'Regan J offered the following in respect of the subject of autonomy: "Recognising the role of freedom of expression in asserting the moral autonomy of individuals demonstrates the close links between freedom of expression and other constitutional rights such as human dignity, privacy and freedom". Underlying all these constitutional rights is the constitutional celebration of the possibility of morally autonomous human beings independently able to form opinions and act on them. As Scanlon described in his seminal essay on freedom of expression, an autonomous person:

... cannot accept without independent consideration the judgment of others as to what he should believe or what he should do. He may rely on the judgment of others, but when he does so he must be prepared to advance independent reasons for thinking their judgment likely to be correct, and to weigh the essential value of their opinion against contrary evidence.66

In State v Jordan counsel argued that the structure of the Constitution makes it necessary to cluster the rights to dignity, privacy, and freedom of the person under the global concept of autonomy due to an overlap of the challenges.67 It was a matter of extreme significance for all persons to be able to determine how to live their lives, and it is the experience of autonomy that matters.68 Autonomy encompasses the right to make decisions rather than the content of these decisions.69 It was also argued that the State should not be empowered to make judgments concerning the good or bad life, as long as the conduct in question does not harm others70. Even where such conduct may be unworthy or risky, the State cannot interfere if it is not harmful to others.71

The Constitutional Court declined to confirm the order of constitutional invalidity on the basis that the regulatory provisions in chapter 19 must be considered in the context of the Children's Act as a whole.72 Further, the impugned provision did not disqualify commissioning parents because they are infertile - it afforded them the opportunity to have children of their own by contributing gametes for the conception of the child.73 If, however, a parent cannot contribute a gamete, the parent still has available options afforded by the law (namely adoption).74

Section 14 of the Constitution provides for the right to privacy, which has been described as "the right to be let alone".75 The right to privacy ensures that certain areas of an individual's life remain free from State interference.76I submit that the choice to select the sex of one's offspring should be a choice which falls under the ambit of the right to privacy, but Ginsburg argues that there are drawbacks to this.77 She discusses this in the context of the right to choose an abortion, and comments that placing the right to choose abortion in the right to privacy has made it easier for the court to justify limiting women's access to abortion.78 She argues that reproductive choice is better based on the right to equality.79 Dworkin suggests that the privacy argument should not be dismissed altogether, but can be used to supplement the equal protection analysis.80 This approach makes sense in South Africa, where there is a long history of State regulation of reproduction.81

The right to freedom and security of the person includes the right for persons to make decisions concerning reproduction and to security in and control over their bodies.82 In Ferreira v Levin (which was decided under the Interim Constitution), the majority of the Constitutional Court interpreted the right narrowly so as to confine it to physical integrity in the context of unlawful detention.83 However, the minority of the Court interpreted the right widely.84Ackermann J interpreted the right to freedom as being distinct from the right to security and in a negative sense, meaning that individuals have the right "not to have obstacles to choices and possible activities" put in their path by the State.85 On this reasoning, the interpretation of the right to freedom and security of the person would not preclude the possibility of the right's supporting preimplantation sex selection.

Section 10 protects the right to dignity by providing that everyone has inherent dignity, which must be respected and protected. It is also a foundational value and an interpretive guide to the Constitution.86 The Constitutional Court has taken the view that the right to dignity amplifies and gives meaning to other rights contained in the Bill of Rights, including the rights to privacy, equality, and freedom and security of the person.87 In the context of abortion, an infringement of dignity has been argued to impact not only on a woman's quality of life, but also on that of her existing family and children. The decision as to what constitutes a society based on dignity, equality and freedom will be determined by the Constitutional Court in the future.88 In R v Morgenthaler the Court described the notion of freedom, as in a free and democratic society, as one which "does not require the State to approve the personal decisions made by its citizens, but does require the State to respect them".89

5.2 The National Health Act 61 of 2003

Chapter 8 of the NHA regulates the use of blood, blood products, tissue and gametes in human beings.90 Like the HTA which it replaced, the NHA prohibits the removal of this human biological material from living persons for medical or dental use without the procurement of the proper written consent of such person.91 The Chapter also contains important prohibitions on the removal of biological material in certain instances, including removal from an individual who is mentally ill; the removal from individuals under the age of 18 years of tissue which is not replaceable by natural processes; and the removal of gametes from individuals who are under the age of 18 years.92 There is a further prohibition against the removal of embryonic, placenta, or foetal tissue, stem cells and umbilical cord, but excluding umbilical cord progenitor cells.93 This exclusion is important as it is these progenitor cells which are removed during umbilical cord blood storage - an option sometimes exercised by parents at the birth of their children for potential later use should the child require treatment.

5.3 Regulations to the National Health Act

The relevant set of regulations issued in terms of section 68(1) of the NHA is the Regulations Relating to Artificial Fertilisation of Persons. They were published in March 2012 (hereinafter referred to as "the Regulations").94The Regulations apply to the withdrawal of gametes from living persons and their use in such. Therefore, they regulate the authorisation of fertility clinics, the removal or withdrawal and storage of gametes, compensation for such removal or withdrawal, the establishment of a Central Data Bank, the donation of gametes, control over artificial fertilisation, embryos transfer storage, and the destruction of embryos and zygotes.

Regulation 13 expressly states that preimplantation and prenatal testing for selecting the sex of a child is prohibited except in the case of a serious sex-linked or sex-limited genetic condition. Regulation 21 imposes a penalty upon any person who contravenes the regulations. Non-compliance with the regulation amounts to an offence and if found liable on conviction, such a person would be liable to pay a fine or to imprisonment not exceeding a period of ten years (or a combination thereof).

The prohibition of sex selection in the absence of disease first appeared in South African law as part of the 2012 regulations. It is worthwhile to note that until that time, individuals were free to select the sex of their embryo/s for implantation. A new set of regulations relating to the artificial fertilisation of persons was published in 2016, but to date these have not been promulgated.95

At the time that the Regulations were promulgated in 2012, the Southern African Society of Reproductive Medicine and Gynaecological Endoscopy (SASREG) was asked to provide input on the issue of sex selection via PGT-A.96 The consensus at the Reproductive Medicine Society at the time was to allow "family balancing", i.e. the choosing the sex opposite to that of an existing child, but not to allow sex selection for the first child.97 Genetics specialists in the country also agreed with this viewpoint, and also provided this recommendation in writing.98 These comments were sent from both groups to the Department of Health.99 The Department of Health made the decision to ban sex selection completely (unless a medical indication existed) and did not allow family balancing. No reasons were provided for this decision.100

5.4 The guidelines of the Health Professions Council of South Africa

The guidelines for good practice in the healthcare professions issued by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) prohibit the use of preimplantation screening in the case of IVF for non-therapeutic reasons.101The Guidelines for Biotechnology Research state that this technology should not be used to positively select for certain characteristics such as a particular gender, hair colour or physical strength, if these characteristics have no significant bearing on the health of the child.102 Sex selection is specifically mentioned in the Guidelines for Reproductive Health, which acknowledges that discrimination based on sex and gender is still prevalent in many societies, and abortion on the basis of the sex of the foetus is a direct violation of the ethical principles of justice and the protection of the vulnerable.103The Guidelines states that sex selection should not be used as a tool for sex discrimination against either sex (particularly the female sex), but may be used as a means of avoiding a sex-linked genetic disorder if deemed necessary by the healthcare practitioner.104 These guidelines counsel against the use of sex selection for non-therapeutic reasons, but it is submitted that the guidelines have not been thoroughly thought through.

While the biotechnology research guidelines prohibit the selection of the characteristics of children in the absence of medical grounds, the specific sex selection provisions in the reproductive health guidelines prohibit the use of sex selection as a tool for sex discrimination. I submit that the selection of a child's sex does not constitute discrimination against the unselected sex. Preference for one sex does not necessarily indicate a sexist attitude. Further, the guidelines urge against the use of selection which has no significant impact on the health of the child. However, it is argued that the choice of sex may well be of such significance. It may be in the future child's best interests that the parent be allowed to exercise this choice. Put differently, it may be in a future child's best interests to exist as a particular sex, rather than face discrimination or more unfavourable conditions as a result of being born of the sex which the parent did not prefer. It is also important to note that the HPCSA guidelines were published in September 2016, following the entry of the prohibition against non-therapeutic sex selection into South African law. As such, the guidelines jump on the proverbial "'bandwagon" created by the Minister in 2012, as opposed to being based on established ethical principles.

5.5 Guidelines of the Southern African Society of Reproductive Medicine and Gynaecological Endoscopy (SASREG)

At the time of writing, SASREG had no profession guidelines for obstetricians and gynaecologists. Instead, it relies on the ESHRE guidelines for non-therapeutic sex selection.105

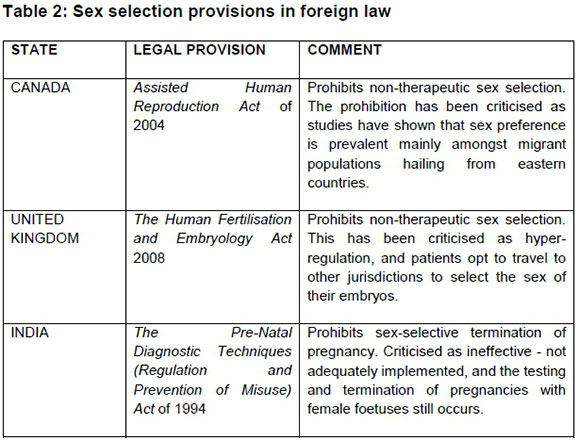

6 Foreign law

Considering that there are at least 36 countries with legal regulation of sex selection, it is worthwhile to assess the approach taken by other jurisdictions.106 For the purposes of brevity, three other jurisdictions will be considered. These have not been arbitrarily selected. They are primarily English-speaking countries in which the Constitution is sovereign. This will allow real comparison to be made with the South African legal framework as they are aligned with the South Africa's human rights dispensation and therefore of comparative value. We must also consider whether the legal provisions of these countries have been unchallenged, and if so, whether these legal challenges have resulted in the legal provisions remaining intact or being amended.107

7 Discussion

On the one hand, a prohibition of sex selection can be interpreted as a limitation of the hard-won right to the reproductive autonomy of women and couples generally.108 On the other hand, it has been argued that where it is used to favour sons, it can perpetuate the devaluation of women's status, therefore enhancing gender inequality and sex discrimination.109 This argument is self-defeating as it suggests the infringement of women's rights to reproductive autonomy in order to prevent discrimination against women! Further, it is not clear that the State can promote equality in the public sphere by prohibiting perceived unequal treatment in the private sphere.

This appears to be an unjustified intrusion by the State on the privacy of the individual. In Griswold v Connecticut the court stated that

The principles ... reach farther than the concrete form of the case then before the court, with its adventitious circumstances; they apply to all invasions on the part of the government and its employees of the sanctity of a man's home and the privacies of life. It is not the breaking of his doors, and the rummaging of his drawers, that constitutes the essence of the offence; but it is the invasion of his indefeasible right of personal security, personal liberty and private property, where that right has never been forfeited by his conviction of some public offence, - it is the invasion of this sacred right which underlies and constitutes the essence of Lord Camden's judgment.110

Moazam argues emphasising on reproductive choice is not the only way to address the problem of discrimination against women in society.111 She argues that autonomy must be evaluated in the context of the relevant culture, and in a society such as India, women are still largely powerless and subjugated to men.112 Sex selection further confines women to subordinate roles as they are treated as "machines to generate the perfect child", while males are preferred to females.113 The position of more liberal feminists can also be taken into account. Their argument places emphasis on the preservation of reproductive autonomy and choice. It holds that women are in the best position to judge whether their pregnancy should be terminated or not, and society should not interfere with that choice.114 Many jurisdictions therefore recognise a woman's right to choose to terminate her pregnancy as an element of her reproductive autonomy. Allowing parents to choose the sex of their offspring constitutes a logical sequence to these developments.115

A further argument levied against sex selection is the "slippery slope" argument of being able to control every characteristic of one's future child. This argument has been used by supporters of the right to choose, on the basis that allowing the State to control reproductive decisions will lead to a gradual loss of women's reproductive control. It has also been argued that sex selection technology may be used to select against progressively milder medical conditions.116 More frequently this argument has been used by opponents of sex selection on the basis that it represents taking one step further on the "slippery slope" of being able to design the perfect child - or a "designer baby".117 This term was considered by the Constitutional Court in AB v Minister of Social Development.118It found the term confounding as it had no precise explanation of its ambit.119 Without a fairly precise explanation of what is intended by it, the term "designer children" is, at best, confounding. The only real attempt to define the term was made in the expert evidence tendered, which defined the term as

A baby whose physical [characteristics] are chosen in advance of their implantation by commissioning parents. The motivation for [this] choice is unrelated to health matters; it is a cosmetic choice as opposed to a choice arising from a medical need.120

Apart from the claim that "designer babies" are those chosen for cosmetic reasons, the court found this definition unhelpful.121 The court also felt that it was unclear whether the term was based on sound scientific principles.122It noted that the expert witness referred to the work of Professor Alan Handyside, who insists that the term has no scientific merit whatsoever.123Handyside believes that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to "cherry-pick a desired combination of traits" because of the approximately eight million possible genetic combinations available in one embryo, amongst other reasons, and the second applicant correctly pointed out that the expert witness had made no attempt to refute these assertions.124

The legal problem is that we do not have clarity regarding what we mean by the terms "designer baby" and "perfect child". Only some characteristics of a child are genetically determined, not all. If by "perfect" we mean optimising the child's chances in life, we in fact have a moral duty to make the child "perfect", in accordance with Savulescu's view. Further, I submit that the term has been deliberately propagated with a negative undertone, in very much the same way that the term "eugenic" has. The dictionary meaning of the term "design" is "to devise for a specific function or end".125 I submit that if we are interpreting the term in the context of PGT-A, then it would encompass diagnosis and selection to achieve a specific genetic result in the resultant offspring. On this premise, all the children born as a result of the use of PGT-A are designer babies. Irrespective of the purpose of the selection, the exercise of that choice achieves a certain end result - the birth of offspring with genetic characteristics which were favoured over those which were not. It is argued that it therefore does not matter whether an individual is selecting against a serious genetic disease or an undesired sex, because if the act of selection for a particular characteristic informs our idea of "design", then these are all designer children. It is thus submitted that the prevailing understanding of the term is incorrect. It has been deliberately used to describe only the positive selection of non-medical traits. This creates a legal inconsistency: why is a child a designer child if we selected its sex at the preimplantation stage, but not a designer child if we selected therapeutic advantages at the preimplantation stage?

Most of the research into the arguments against sex selection are based on the premise that the choice of sex of an embryo amounts to discrimination against the sex which is not selected. To allow an individual to select the sex of their embryo would reinforce societal prejudices against one sex (usually females). But can sex selection amount to discrimination if we consider acts of discrimination as prohibited against legal persons? There is no "person" in existence at the PGT-A stage, because it is trite that a foetus cannot be the bearer of rights and duties. So, if there is no discrimination against an actual person, whom is the discrimination against? The idea of the opposite sex? Males or females in the abstract? This is not a sound argument as the values of equality, dignity and so forth do not exist in the abstract, and are not protected as such. Equality is constitutionally protected as both a value and a right. Rights and values often coincide and coexist, but are separate concepts. Values are associated with communities or groups of individuals and their belief systems, such as their religious values, their cultural values etc. Rights, on the other hand, attach to individuals. Rights are therefore not defined in terms of group beliefs. We may therefore classify rights broadly, such as "human rights". Although these concepts are abstract ideas, their objects are real people, not abstracted, non-existent people. They are therefore protected insofar as they apply to actual legal persons.

The Constitution does not protect an abstract notion of equality; it protects the equality of actual people. In order to label sex selection as discriminatory, one would have to show how sex selection discriminates against actual people. Individuals should have the right to choose the sex of the foetus as part of their right to privacy. Their choice is not necessarily indicative of discrimination or an attitude towards the opposite sex. It is a purely personal choice within the personal sphere, and there may be other factors or values which have influenced that choice. While there may be individuals who would prefer a child of one sex due to an active "dislike" of the other, the author does not support the argument that to select a female embryo, for example, implies a general prejudicial and discriminatory attitude towards the male sex. In the same way, if a person chooses to enter into a heterosexual relationship, that choice does not automatically imply that they are a homophobic. To select against an embryo which possesses Down's Syndrome does not at all reflect a general attitude towards people who are already living with Down's Syndrome. In short, a person's choice exercised in his or her private life will not reflect a general public attitude, and these choices should be respected as part of the person's right to privacy. These choices in no way infringe on or are in violation of any other person's rights.

This issue may be contrasted with selection against a genetic condition, such as Down's Syndrome. Selection against embryos that possess the genetic karyotype for Down's Syndrome is not seen as discrimination. Down's Syndrome is a disease that is completely legal to select against (on the basis that it is accepted as a genetic disease serious enough to warrant its being selected against). People who are currently living with Down's Syndrome enjoy the same rights and freedoms as other individuals. They are respected as members of society and not subjected to harsh treatment based on their having Down's Syndrome. They are allowed to live as normal lives as is possible. However, an embryo which possesses the genetic karyotype indicative of Down's Syndrome may be destroyed - discarded as medical waste - because its parent/s positively selected an embryo which did not possess Down's Syndrome - a "healthy" embryo. So, if we are prepared to accept that there is no question about the rights of individuals living with Down's Syndrome, but the law sanctions selection against embryos possessing Down's Syndrome, surely this implies that the selection does not amount to discrimination at all? So why should selection between male and female embryos amount to discrimination? To differentiate between embryos cannot amount to discrimination, because discrimination does not exist in relation to an abstract idea. The same argument should apply to sex selection.

Let us consider an example to illustrate the possible practical outcomes which result from the prohibition against sex selection. Imagine a woman pressured by her culture to bear a son, because her husband's family needs an heir to continue the family name. Imagine this woman falling pregnant and carefully monitoring her pregnancy at each doctor's appointment, waiting with bated breath until the day that the ultrasound can reveal the sex of the foetus she is carrying. Imagine that she discovers that she is carrying a daughter. There are a number of possible outcomes from this point on. The sex of a foetus can first accurately be determined between 12 and 14 weeks of gestation. She could choose to terminate the pregnancy on the basis of the foetus's sex, which she is entirely entitled to do provided the termination falls within the time frames identified in the TOP legislation as a legal termination. In law, this termination would not be seen as discrimination against females. Yet how is it different to selecting against an embryo of a particular sex? This is arguably a worse scenario than allowing a woman to choose the sex of her child at the embryonic stage. It is accepted that neither the embryo nor the foetus in gestation is capable of bearing any rights, and neither are they seen as legal entities. However, is it justifiable to prevent an individual from selecting the sex of the child prior to pregnancy, or to insist that the individual play the "genetic lottery" and terminate a pregnancy which will ultimately yield a child of the undesired sex? It is arguably less traumatising for the woman (and society) to select against the sex not preferred prior to pregnancy than to terminate it in utero. The second possible outcome for this woman is that she continues the pregnancy. There are hereafter a number of possible consequences for both herself and the child she bears. She may face prejudice, having borne a daughter, and psychological trauma arising from her sense of having let her husband down, disgracing the family etc. In some cultures she may be thrown out of the family home, with or without her daughter. A heavy price to bear for an outcome that she was prohibited from avoiding.

Potentially, the daughter who is born has the heaviest price to pay in this scenario. This child is unwanted, having been born of the undesired or "wrong" sex. To cater for her interests, the "best interests of the child" (or future child) principle may be considered. This is arguably one of the most important considerations. Would it not have been in her best interests to allow her parents to select the sex of their foetus? In trying to preserve the ideal of the equality of the sexes and to prevent discrimination against one or the other, the law denies an individual the capacity to avoid a situation which results in an actual person's suffering discrimination and inequality. This if anything is a failure of the law to prevent discrimination. The current legal framework prioritises the interests of the community to the absolute detriment of the interests of the individual and the future child. What an analysis of the example shows is that permitting sex selection would support the interests of the individual and future child, but this does not entail sacrificing community interests. In fact, it has yet to be established that prohibiting sex selection is in the interests of the community. There is no compelling argument that sex selection should be treated any differently from other traits that the law currently allows to be actively selected against. It is submitted that the community interest does not suffer as a result. Even if we distinguish between genetic characteristics such as sex and diseases like Down's Syndrome on the basis that disease impacts on the health of the embryo whereas sex does not necessarily have that same effect, we still run into trouble. Even in the absence of a sex-linked disease, surely sex is capable of being as significant to the future child's life as a disease would be? Sex may not affect the physical health of that child, but what about the emotional or psychological health of that child? Again, it may well be in the best interests of that future child that his or her parent/s be allowed to exercise choice over his or her sex.

It must also be asked whether there is always a need to justify sex selection on the basis that it would be in an individual's best interests. If it is accepted that selection against Down's Syndrome embryos does not amount to discrimination against people living with Down's Syndrome, why would selection against a female embryo (for example) amount to discrimination against females? It cannot. Non-therapeutic sex selection should be a right, and not simply prohibited because it offends an ideal.

In the US and UK, studies have indicated that sex selection would not result in a marked preference for males over females, one of the fears associated with non-therapeutic sex selection.126 It is indisputable that there are some cultures which do show a marked preference for boys over girls, but cultures differ from country to country, and within countries - especially in multicultural countries such as South Africa. In Canada, for instance, it has been recognised that sex-selective practices are prevalent in migrant populations primarily of Asian origin.127 One study indicated that the male/female ratios in Ontario showed that migrant women born in India were significantly more likely than women born in Canada to have a male infant - and this in a country that does not allow preimplantation sex selection or the termination of pregnancy. This demonstrates that preimplantation sex selection is clearly preferable to the selective termination of pregnancy.128

The prohibition of sex selection in India does not indicate that sex selection should likewise be prohibited in South Africa. There are no clear reasons why non-therapeutic sex selection was suddenly prohibited in South Africa in 2012. The World Health Organization has even stated that

...although the relatively recent availability of technologies that can be used for sex selection has compounded the problem, it has not caused it.129

If it is to guard against the possible preference of a son, then data would need to support that objective. In the absence of such, it is a massive intrusion on the right to the reproductive autonomy of an individual, as well as an arbitrary prohibition. It is submitted that it is not the duty of the State to maintain the male/female sex ratio, and further that the State does not have the duty of ensuring that individuals will be able to procure a spouse for the purposes of marriage and/or procreation.

In its report on sex selection, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority states:

... the main argument against prohibiting sex selection for non-medical reasons is that it concerns that most intimate aspect of family life, the decision to have children. This is an area of private life in which people are generally best left to make their own choices and in which the State should intervene only to prevent the occurrence of serious harms, and only where this intervention is non-intrusive and likely to be effective.130

The excerpt demonstrates the HFEA's recognition of the argument that sex selection falls within the ambit of private and family life, and that any interference by the State would have to be justified.131 This issue has not been decided by a court of law. However, if sex selection did fall within the right to respect for private and family life as protected under Article 8 of the European Convention Human Rights, the question would be whether or not the state can justify interference with that right.132 It follows that if a court were to decide that sex selection does not fall under the ambit of that right, the state would not have to justify interference.133 While the HFEA suggests that public opinion against the practice contributed to its decision in favour of a continued ban, it concluded its report by stating that

[Consultation] ... shows that there is a wide-spread hostility to the use of sex selection for non-medical reasons. By itself this finding is not decisive, the fact that a proposed policy is widely held to be unacceptable does not show that it is wrong. But there would need to be substantial demonstrable benefits of such a policy if the State were to challenge the public consensus on this issue.134

In its report on sex selection the HFEA highlighted concerns about the welfare of families and children, particularly the risk of psychological harm to children who were selected on the basis of their sex alone.135 This point is criticised by John Harris, who argues that it is difficult to prove that a child is selected on the basis of its sex alone.136 Speculative harms must be balanced against the parents' reasons for wanting to select the sex of their child. The HFEA report on sex selection is criticised as having underplayed the interests of parents, because even though it implicitly acknowledges that sex selection is part of the right to private and family life, it concentrates on the alleged harms which would be caused to others.137 The HFEA concedes that we cannot know what the result will be unless we legalise the practice of sex selection and thereafter monitor it.138 It also observes a positive benefit of sex selection, in that it would reduce the number of "unwanted" children or aborted foetuses, and the effects of parental disappointment in families where the parents keep attempting to conceive a child of a particular sex naturally.139 This is significant and weighs against the speculative harms and risks to which the HFEA and other authors have given attention.140 The benefit appears to undermine the idea that there is a pressing need to prohibit sex selection on the basis that it is necessary to guard against highly speculative infringements of the rights and freedoms of others.141

It has been suggested that Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights applies to self-determination in a general way.142 Privacy can be viewed as a subset of autonomy, or as a synonymous concept.143 Scott states that autonomy and privacy are not one and the same thing.144However, the European Court of Human Rights observed in Pretty v United Kingdom that while there was no legal precedent which established any right to self-determination under Article 8, the Court considered personal autonomy to be an important principle underlying the interpretation of its guarantees.145 Scott argues that this can be interpreted as the court's recognising that self-determination is not the same as privacy, but personal autonomy is still important in the interpretation of Article 8.146 The court has interpreted the right to respect for private and family life, and particularly the meaning of "private life", in various ways. This includes the right "to establish and develop relationships with other human beings especially in the emotional field, for the development and fulfilment of one's own personality".147 Overall, Article 8 has been said to protect the individual from arbitrary action by public authorities.148 In Evans v United Kingdom, the court held that the right to respect for the decision to become a parent in the genetic sense also fell within its ambit.149 Scott argues that this interpretation provides the basis for a case to be made that sex selection falls within the sphere of private life.150 It could be argued that parents have the right to opt to have either a male or a female child and therefore to establish a relationship with one or the other.151

8 Conclusion

Before assisted reproductive technology became available, infanticide and neglect were the main methods by which families dealt with unwanted children.152 Technology has allowed individuals to exercise control over the traits of their future children by positively selecting for or against particular traits. While selection against serious medical conditions is largely permitted around the world, the positive selection of traits is subject to legal control. Sex selection, whilst permitted where it is necessary to avoid a sex-linked condition, is subject to a blanket prohibition where its use is non-therapeutic.

International human rights law focusses mainly on whether the permissibility of choosing the sex of one's offspring is inherent in the right to reproductive choice. An analysis of international human rights law suggests that the international human rights perspective is geared towards a general prohibition against sex selection; but it is important to note that the prohibitions lie against prenatal sex selection and not expressly preimplantation sex selection. It has been suggested that the reason for this omission is that technology had not yet advanced to the current stage at the time when the international documents were drafted. It is submitted that banning the practice will not eradicate sex selection, and it most certainly will not eradicate discrimination against women. States such as India have attempted to do so by the prohibition of dowries and sex selection.153However, these measures have not achieved their purposes. India has failed to eradicate dowries and most certainly has failed to prevent sex selection. Sex selection can be analysed against the backdrop of another right which forms part of reproductive autonomy - the right to choose to terminate a pregnancy. A prohibition of terminations does nothing but drive the practice underground, where women may be subject to unsafe treatment. As Mohapatra concluded, until social issues such as son preference are combated, legislative efforts to stop sex selection will not be effective and may result in harming women rather than assisting them.154Safe terminations are therefore encouraged and access to healthcare facilities is imperative. Similarly, prohibiting sex selection would have no result other than inducing individuals to seek assistance elsewhere. Restricting access to technologies and services without addressing the social norms and structures that determine their use is likely to result in a greater demand for clandestine procedures which fall outside the regulations, the protocols and the scope of monitoring.155 The WHO concluded its inter-agency statement by affirming that imbalanced sex ratios (outside the 106:100 male-to-female ratio) are an unacceptable manifestation of gender discrimination against girls and women and a violation of their human rights.156 However, while imbalanced sex ratios may be of concern, the countries offered as evidence are mainly those in South-Asia, East-Asia and Central Asia.157 Countries like Canada have seen this trend in the birth statistics of migrant populations. In those countries the sex ratio can be indicative of underlying discrimination against females, as females are under pressure to produce sons. However, in the absence of data, we cannot conclude that this finding will be applicable to all countries. The United Kingdom prohibits non-therapeutic sex selection, and the restriction has been criticised as excessive regulatory control. South Africa did not prohibit the practice until 2012, and no reasons were advanced for instituting the prohibition,

In conclusion, it is clear that preimplantation sex selection must be distinguished from other types of sex selection. While prenatal sex selection may be prohibited, there is no convincing reason to prohibit it at a preimplantation level.

Bibliography

Literature

Cook RJ, Dickens BM and Fathalla MF Reproductive Health and Human Rights: Integrating Medicine, Ethics, and Law (Clarendon Press Oxford 2003) [ Links ]

Deonandan R "Recent Trends in Reproductive Tourism and International Surrogacy: Ethical Considerations and Challenges for Policy" 2015 Risk Manag Healthc Policy 111-119 [ Links ]

Dickens BM "Can Sex Selection be Ethically Tolerated?" 2002 J Med Ethics 335-336 [ Links ]

Dondorp W et al "ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law 20: Sex Selection for Non-medical Reasons" 2013 Human Reproduction 1448-1454 [ Links ]

Dworkin R Life's Dominion: An Argument about Abortion and Euthanasia (Vintage New York 1994) [ Links ]

Ginsburg R "Sex Equality and the Constitution: The State of the Art" 1992 Women's Rights Law 361-366 [ Links ]

Glendon MA Abortion and Divorce in Western Law (Harvard University Press Cambridge, Mass 1989) [ Links ]

Harris S "Sex Selection and Regulated Hatred" 2005 J Med Educ 291-294 [ Links ]

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority Sex Selection - Options for Regulation: A Report on the HFEA's 2002-2003 Review of Sex Selection including a Discussion of Legislative and Regulatory Options (HFEA London 2003) [ Links ]

Health Professions Council of South Africa Guidelines for Good Practice in the Health Care Professions: General Ethical Guidelines for Reproductive Health (Booklet 8) (HPCSA Pretoria 2016) [ Links ]

Health Professions Council of South Africa Guidelines for Good Practice in the Health Care Professions: General Ethical Guidelines for Biotechnology Research in South Africa (Booklet 14) (HPCSA Pretoria 2008) [ Links ]

Jones OD "Sex Selection: Regulating Technology Enabling the Predetermination of a Child's Gender" 1993 Harv J L & Tech 1-62 [ Links ]

Moazam F "Feminist Discourse of Sex Screening and Selective Abortion of Female Foetuses" 2004 Bioethics 205-220 [ Links ]

Mohapatra S "Global Legal Responses to Prenatal Gender Identification and Sex Selection" 2013 Nev L J 690-721 [ Links ]

Nys H "Physician Involvement in a Patient's Death" 1999 Med L Rev 208246 [ Links ]

O'Sullivan M "Reproductive Rights" in Woolman S and Bishop M (eds) Constitutional Law of South Africa (Juta Cape Town 2013 RS 3) ch 37 [ Links ]

Pepper MS "Enactment of Chapter 8 of the National Health Act and Regulations thereto" 2012 SAJBL 60 [ Links ]

Ray JG et al "Sex Ratios among Canadian Liveborn Infants of Mothers from Different Countries" 2012 CMAJ E492-E496 [ Links ]

Sachan D "India's Problem with Girls" 2013 BMJ 4149 [ Links ]

Scott R Choosing between Possible Lives: Law and Ethics of Prenatal and Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (Hart Oxford 2007) [ Links ]

South African Law Commission Report on Surrogate Motherhood: Project 65 (Pretoria November 1992) [ Links ]

Scott R Rights, Duties and the Body: Law and Ethics of the Maternal-fetal Conflict (Hart Oxford 2002) [ Links ]

Toebes B "Sex Selection under International Human Rights Law" 2008 Med L Int 197-225 [ Links ]

Tregenza-Parker G Sex Selection for Family Balancing? A Legal and Ethical Analysis (LLM-dissertation University of Exeter 2013) [ Links ]

Van Niekerk C "Assisted Reproductive Technologies and the Right to Reproduce under South African Law" 2017 PELJ 1-31 [ Links ]

Vogel L "Sex Selection Migrates to Canada" 2012 CMAJ E163-E164 [ Links ]

Case law

AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (GP)

AB v Minister of Social Development 2017 3 BCLR 267 (CC)

Brüggeman and Scheuten v Federal Republic of Germany D&R 10 (1978)

Barkhuizen v Napier 2007 5 SA 323 (CC)

Evans v United Kingdom (2007) ECHR 264

Ferreira v Levin 1996 1 SA 984 (CC)

Griswold v Connecticut 381 US 479 (1965)

Karen Noelia Llantoy Huamán v Peru Communication No 1153/2003

Kroon v Netherlands (1994) 19 EHRR 263

NM v Smith 2007 5 SA 250 (CC)

Pretty v United Kingdom (1998) 26 EHRR 241

R v Morgenthaler (1988) 44 DLR (4th)

S v Jordan 2002 11 BCLR 1117 (CC)

S v Makwanyane 1995 3 SA 391 (C)

Legislation

Children's Act 38 of 2005

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983

National Health Act 61 of 2003

International instruments

Beijing Declaration (1995)

Cairo Programme of Action (1994)

Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000)

European Convention on Human Rights (1950)

European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (1997)

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966)

Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005)

UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979)

UN Human Rights Committee General Comment No 28: The Equality of Rights between Men and Women (Article 3) UN Doc CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.10 (2000)

Government publications

GN R175 in GG 35099 of 2 March 2012

GN R1165 in GG 40312 of 30 September 2016

Personal communications

Personal communication between the author and Dr Paul le Roux (Cape Fertility Clinic), 12 January 2018

Internet sources

Chamie J 2008 "The Global Abortion Bind" Yale Global Online https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/global-abortion-bind accessed 11 August 2019 [ Links ]

Darnovsky M 2009 Countries with Laws or Policies on Sex Selection https://nanopdf.com/download/countries-with-laws-or-policies-on-sex-selection_pdf accessed 11 August 2019 [ Links ]

Merriam-Webster Dictionary 2019 Dictionary https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary accessed 11 August 2019 [ Links ]

Sen G 2009 Gender Biased Sex Selection. Key Issues for Action https://www.dawnnet.org/uploads/documents/Sex%20Selection%20GS%20draft%2008062009_2011-Mar-8.pdf accessed 26 August 2019 [ Links ]

United Nations Population Fund 1994 Programme of Action (adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 5-13 September 1994) https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/PoA_en.pdf accessed 11 August 2019 [ Links ]

World Health Organization 2011 Preventing Gender-Biased Sex Selection: An Inter-Agency Statement https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/gender_rights/9789241501460/en/ accessed 9 September 2017 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

ART Assisted reproductive technologies

BMJ British Medical Journal

CEDAW UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979)

CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal

ECHR European Convention on Human Rights

ESHRE European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

EU European Union

Harv J L & Tech Harvard Journal of Law and Technology

HFEA Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority

HPCSA Health Professions Council of South Africa

HTA Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983

Hum Reprod Human Reproduction

IVF In-vitro fertilisation

J Med Educ Journal of Medical Education

J Med Ethics Journal of Medical Ethics

Med L Int Medical Law International

Med L Rev Medical Law Review

Nev L J Nevada Law Journal

NHA National Health Act 61 of 2003

PELJ Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal

PGT Preimplantation genetic testing

PGT-A Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy

PGT-M Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenetic disorders and HLA-typing

PGT-SR Preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements

Risk Manag Healthc Policy Risk Management and Healthcare Policy

SAJBL South African Journal of Bioethics and Law

SASREG Southern African Society of Reproductive Medicine and Gynaecological Endoscopy

TOP Termination of pregnancy

UN United Nations

WHO World Health Organization

Date Submission 16 October 2018

Date Revised 13 September 2019

Date Accepted 13 September 2019

Date published 25 October 2019

* Sheetal Soni. LLB (UNatal) LLM Doctoral Candidate (UKZN). Lecturer of International Law and Bioethics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. E-mail: sonish@ukzn.ac.za.

1 Chamie 2008 https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/global-abortion-bind.

2 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 197.

3 It encompasses a number of different practices including the use of prenatal ultrasound imaging during pregnancy to determine the sex of the foetus, as well as infanticide or child neglect post-birth. This article focusses on preimplantation selection only.

4 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 198.

5 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 198.

6 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 198.

7 Dickens 2002 J Med Ethics.

8 Darovsky 2009 https://nanopdf.com/download/countries-with-laws-or-policies-on-sex-selection_pdf.

9 Deonandan 2015 Risk Manag Healthc Policy.

10 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 207.

11 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 207.

12 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 207.

13 Cook, Dickens and Fathalla Reproductive Health and Human Rights 175.

14 Cook, Dickens and Fathalla Reproductive Health and Human Rights 175.

15 Cook, Dickens and Fathalla Reproductive Health and Human Rights 158.

16 The Convention entered into force in 1999 and has been ratified by 29 countries (although the United Kingdom declined to ratify it).

17 UNESCO's Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005).

18 Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005).

19 Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005).

20 The grounds include national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of crime and disorder, for the protection of morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

21 Article 3(2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000).

22 Article 7 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000).

23 Article 20 and 23 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000).

24 UN Population Fund 1994 https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/PoA_en.pdf 26.

25 UN Population Fund 1994 https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/PoA_en.pdf 28.

26 Prenatal selection takes place during the gestation of the foetus, unlike selection at the preimplantation stage, which precedes a pregnancy.

27 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 210.

28 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 210.

29 Article 16(1) of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) (CEDAW).

30 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 211.

31 UN Human Rights Committee General Comment No 28: The Equality of Rights between Men and Women (Article 3) UN Doc CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.10 (2000).

32 Karen Noelia Llantoy Huamán v Peru Communication No 1153/2003.

33 Brüggeman and Scheuten v Federal Republic of Germany D&R 10 (1978) 61.

34 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 211.

35 Toebes 2008 Med L Int 212.

36 There is no agreement in international law as to when life begins. Therefore, the international framework provides no guidance as to how the right to life relates to prenatal sex selection.

37 The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) was founded in 1985 by Robert Edwards and J Cohen, who felt that study and research in the field of reproduction needed to be encouraged and recognised. ESHRE aims to promote the understanding of reproductive biology and embryology, facilitate research and the subsequent dissemination of research findings to the public, scientists, clinicians and patient associations and to inform politicians and policy makers in Europe. ESHRE engages in medical education activities, the development of data registries, and the implementation of methods to improve safety and quality in clinical and laboratory procedures. ESHRE is comprised of a General Assembly, which is made up of diverse sub-special interest groups, such as andrology, reproductive genetics, ethics and law, and paramedics; and an Executive Committee, which has various sub-committees, such as the Finance Subcommittee, Training Subcommittee, Annual Meeting Subcommittee, the Committee of National Representatives, and the Communications Committee.

38 Dondorp et al. 2013 Hum Reprod 1448.

39 Dondorp et al. 2013 Hum Reprod 1452.

40 Dondorp et al. 2013 Hum Reprod 1448.

41 Dondorp et al. 2013 Hum Reprod 1448.

42 Dondorp et al. 2013 Hum Reprod 1452.

43 Dondorp et al 2013 Hum Reprod 1453.

44 HFEA Sex Selection.

45 Dondorp et al. 2013 Hum Reprod 1448.

46 The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

47 Pepper 2012 SAJBL 60.

48 Pepper 2012 SAJBL 60.

49 Pepper 2012 SAJBL 60.

50 O'Sullivan "Reproductive Rights" 2.

51 O'Sullivan "Reproductive Rights" 2.

52 Section 12(2)(a) of the Constitution.

53 Van Niekerk 2017 PELJ 31.

54 Van Niekerk 2017 PELJ 31.

55 Van Niekerk 2017 PELJ 31.

56 Van Niekerk 2017 PELJ 31.

57 AB v Minister of Social Development 2017 3 BCLR 267 (CC) para 76.

58 South African Law Commission Report on Surrogate Motherhood para 4.6.3.

59 See AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (GP) at para 38 where the court referred to the Commission's report.

60 AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (GP) para 38.

61 AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (gp) para 38.

62 AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (gp) para 292.

63 AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (gp) para 244.

64 AB v Minister of Social Development 2015 4 All SA 24 (gp) para 313

65 65 Barkhuizen v Napier 2007 5 SA 323 (CC).

66 66 NM v Smith 2007 5 SA 250 (CC).

67 67 S v Jordan 2002 11 BCLR 1117 (CC).

68 68 S v Jordan 2002 11 BCLR 1117 (CC).

69 69 S v Jordan 2002 11 BCLR 1117 (CC).

70 70 S v Jordan 2002 11 BCLR 1117 (CC).para 52.

71 71 S v Jordan 2002 11 BCLR 1117 (CC).

72 72 AB v Minister of Social Development 2017 3 BCLR 267 (CC).

73 73 AB v Minister of Social Development 2017 3 BCLR 267 (cc).

74 AB v Minister of Social Development 2017 3 BCLR 267 (CC).

75 Glendon Abortion and Divorce in Western Law.

76 O'Sullivan "Reproductive Rights".

77 Ginsburg 1992 Women's Rights Law 363.

78 Ginsburg 1992 Women's Rights Law.

79 Ginsburg 1992 Women's Rights Law.

80 Dworkin Life's Dominion.

81 Historically, it was women whose rights to reproductive autonomy was limited by excessive State regulation in South Africa. Women were, for example, subject to the marital power of their husbands and did not have equal status as guardians of their children until 1993.

82 Section 12(a) and (b) of the Constitution.

83 Ferreira v Levin 1996 1 SA 984 (CC).

84 Ferreira v Levin 1996 1 SA 984 (CC).

85 Ferreira v Levin 1996 1 SA 984 (CC).

86 Sections 10 and s1(a) of the Constitution.

87 S v Makwanyane 1995 3 SA 391 (C).

88 O'Sullivan "Reproductive Rights".

89 R v Morgenthaler (1988) 44 DLR (4th) 486.

90 The Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 was enacted to provide for the donation or making available of human bodies and tissues for the purposes of medical or dental training, research or therapy, or the advancement of those fields generally.

91 Section 55(a) of the National Health Act 61 of 2003.