Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.22 n.1 Potchefstroom 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a5194

ARTICLES

The Prevention of Organised Crime Act 1998: The Need for Extraterritorial Jurisdiction to Prosecute the Higher Echelons of Those Involved in Rhino Poaching

RD Nanima*

University of Western Cape South Africa; rnanima@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The continuous rising levels of rhino poaching in South Africa require smart strategies that move beyond prosecuting the actual poachers to engaging the transnational criminals who deal with the rhino horn after it leaves the country. In this regard, South Africa has a number of laws that deal with the poaching of rhino horns. The Prevention of Organised Crime Act 121 of 1998 (POCA) does not provide for the adequate prosecution of offenders outside South Africa. It is argued that the POCA has to be amended to provide for extraterritorial jurisdiction to deal with the prosecution of the higher echelons of those involved in rhino poaching. While the POCA provides for extraterritorial jurisdiction in some respects, the application of these provisions still presents challenges in their implementation. To substantiate this claim, this article first discusses the international networks that support the trade in rhino horn. A critique of the available statistics on rhino poaching follows, as does a suggestion that attention must be paid to the details in the statistical records to understand how desperate the situation is. Thereafter, an evaluation of South Africa's legislative framework and other interlinking factors that affect rhino poaching is performed This demonstrates the need for extraterritorial jurisdiction with regard to rhino poaching.

Keywords: Extraterritorial jurisdiction; higher echelons; National Strategy; Prevention of Organised Crime Act; prosecution; rhino poaching.

1 Introduction

South Africa has placed a lot of emphasis on the prosecution of rhino poaching, using the various strategies at its disposal. These include the use of preventive measures like the training of officers to detect smuggling at the ports of entry, the specialised training of game rangers to aid the execution of body/vehicle searches, arrests, and the handling of seized items across South Africa.1 Statistics have been compiled that indicate a high degree of success in the prosecution and conviction of these criminals. However, at the core of these statistics are disturbing details pertaining to the conviction rate. This is defined as the percentage of the convictions divided by the number of cases finalised with a verdict. As will be shown, the conviction rate is not a good yardstick to measure success.

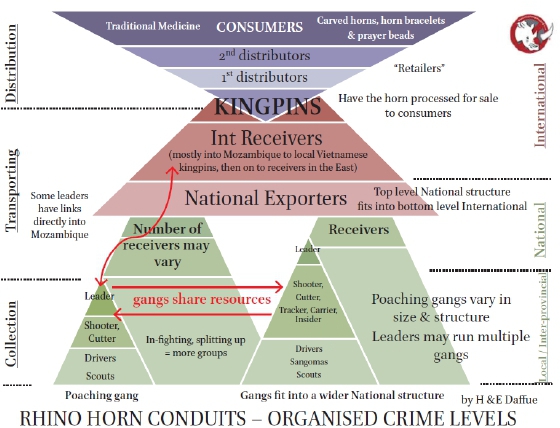

In addition, the conviction rate is not explained in the light of the classification of the rhino poaching syndicates. While the classification reflects the three stages of collection, transportation, and distribution,2 the reconciliation with the persons who are convicted is limited to those arrested and prosecuted in South Africa. These individuals are usually involved in the collection and transportation stages. This limitation does not adequately deal with the accused who are arrested outside South Africa. It is argued that an informed conclusion can be arrived at only after an evaluation of South Africa's legislation, the principles of criminal law, and other interlinking factors in the prosecution the higher echelons.

1.1 Classification of organised crime networks

Hendricke and Daffue classify the organised rhino crime network as a complex system that consists of three stages: collection, transportation, and distribution.3 At the collection stage are local gangs that include scouts, drivers, shooters, cutters and leaders, who go to the national parks and harvest the rhino horn.4 The leaders, who usually have direct links to Mozambique, act as the conduit to the transportation stage, where they take the rhino horn either to national exporters or to international receivers.5 The latter individuals then transfer the rhino horn to the kingpins. The kingpins act as the last link in the transportation chain and may have the horns processed for the distribution stages.6 The kingpins also act as the links between the transportation stage and the distribution stage. They transmit the horns to the first distributors, who deliver them to the second distributors. At this point, the horn reaches the final consumer.7

This structure is similar to that of the criminal chain proposed by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime (The Global Initiative).8Transnational organised crime includes three groups: the source, transit, and the destination market.9 At the source, the poachers or the collectors carry out the act of poaching, extraction and collection of the resources.10The collection stage is closely related to Hendricke and Daffue's model. The second stage, including transit, involves various players such as brokers and smugglers, who perform various acts, including bribing the relevant officers and smuggling, to ensure that the merchandise is taken out of the first jurisdiction.11 It is at this point that the national exporters and international receivers come in handy in ensuring that the rhino horn is brought to the markets, once it has been smuggled out of South Africa. The Global Initiative presents the final stage as the destination market, which engages with players such as market controllers, vendors, traditional medicine practitioners, wildlife restaurant owners, and consumers.12 These five players ensure that the poached product is ready for purchase and consumption.

While Hendricke and Daffue's classification present the three stages of collection, transportation and distribution,13 the Global Initiative, too, presents the three stages of source, transit and market. As points of intersection, the stages of source and collection, followed by transportation and transit, culminate in the distribution or destination market. Both these models present three levels in rhino horn poaching. For the purposes of this article, the author uses the model of Hendricke and Daffue, as illustrated below:14

The framework of the networks (as illustrated above) aids in the argument that prosecution is to a major extent targeted at the players in the collection stage. There is inadequate prosecution of the players at the transportation and the distribution stages.

1.2 Unpacking the emphasis on rhino poaching

Before delving into the body of the article, it may be prudent to explain the author's emphasis on the need to prosecute rhino poaching in particular rather than poaching of other kinds of wildlife, or other complex transnational crimes with a similar organisational structure that are not yet adequately dealt with in legislation.

First, the rhino is the species closest to extinction after the group of the pangolins, vultures, and riverine rabbits.15 Poaching has greatly affected the black rhino population, followed by the white rhino.16 An attempt to extend the emphasis of this article to other endangered species that are affected by poaching would affect the quality of the evaluation and compromise the arguments made in this contribution. Secondly, other kinds of transnational organised crime present similar organisational structures,17 yet the gaps in the current legislation affect effective prosecution.18 Notable examples include human trafficking, terrorism and related offences, corruption, the smuggling of persons, dealing in drugs, dealing in arms, and illicit trading. The point of departure is that there are international or regional treaties that are specific to the prosecution of these crimes as international crimes.19 The possibility of using universal jurisdiction to prosecute them makes the prosecution easier.20 As will be shown, the lack of interlinking factors such as the codification of the aut dedere aut judicare principle in South Africa's laws, the lack of universal jurisdiction to prosecute rhino poaching, and the lack of specific extradition treaties are factors that support the argument made here.21

1.3 An evaluation of the National Integrated Strategy to Combat Wildlife Trafficking

The DEA has adopted a National Integrated Strategy to Combat Wildlife Trafficking (NISCWT).22 The NISCWT defines poaching to include the activity of the illegal capturing or hunting of wildlife, with the intention of possession, transportation, consumption, exportation or the selling and use of its body parts.23 Poachers are defined as individuals or a group of individuals involved in the collection, transportation, consumption, exportation and the sale of the body parts. These two definitions recognise the categorisation of the stages in rhino poaching,24 and the trafficking syndicates as key players in rhino poaching in South Africa. 25 The efficacy of the NISCWT should be with regard to the measures that should be used to deal with individuals who are involved in the transportation, consumption, exportation and sale of the rhino horn outside South Africa. This is because the current legislative framework deals to a great extent with the poachers at the collection stage in South Africa, who are usually arrested and prosecuted.26

In this regard, the NISCWT is guided by three objectives:

[To improve] law enforcement, supported by the whole of government and society, to effectively investigate, prosecute and adjudicate wildlife trafficking as a form of transnational organised crime.

[To increase] the government's ability to detect, prevent and combat wildlife trafficking in South Africa and beyond.

[To increase] national, regional and international law enforcement collaboration and cooperation on combating wildlife trafficking.27

An adequate evaluation of all these three objectives of the NISCWT is beyond the scope of this article. This article evaluates specific aspects of the NISCWT with regard to how higher echelons, as part of the wider definition of poachers, can be effectively prosecuted in South Africa. The second objective that requires the Republic to detect, prevent and combat wildlife trafficking within and beyond South Africa is evaluated.

The second objective emphasises the need to ensure that ports of entry are not used for wildlife trafficking.28 The government is expected to detect, prevent and combat wildlife trafficking within and beyond the Republic, reduce corruption, increase its resources to improve security at the border points, and enhance crime preventive strategies around poaching hotspots.29 These obligations are not enforced beyond South Africa's borders because of the lack of extraterritorial jurisdiction and mutual cooperation with other States.30 The key question is how the government can perform the three obligations outside South Africa. The answers are in the interrogation of the current statistics on poaching, the legislative provisions, the modes of criminal liability, and the doctrine of aut dedere aut judicare with regard to the prosecution of higher echelons.

2 Current statistics: a danger in the detail?

The reported statistics are not uniform, which requires that they be approached with caution. The official statistics published by the Department of Environmental Affairs show a significant increase in the number of poachers arrested in 2016 and a decline in rhino poaching to 24 per cent.31This is based on the arrest of 414 poachers in South Africa, in contrast to the 557 arrests in 2015. The Government reiterates that it has undertaken preventive measures which include the training of officers to detect smuggling at the ports of entry, and the specialised training of over 1000 game rangers to aid the execution of body and vehicle searches, arrests, and the handling of seized items across South Africa.32

On the other hand, other scholars who follow rhino poaching closely offer a different interpretation.33 It is reported that 1028 rhinos were poached from January to December 2017, which reflects a minimal decline of 2.4 per cent in comparison to the 1002 rhinos poached in 2016.34 The statistics are different because of the different definition accorded to the "conviction rate" by the NPA. It is defined as the percentage of cases with a guilty verdict divided by the number of cases finalised with a verdict.35 This definition does not include cases that are not brought to court for prosecution or where arrests made but without consequent prosecution. Such a definition leads to different statistics depending on whether the percentage of cases with a guilty verdict is related to cases with a verdict or cases where arrests have been effected.

Something is evident in the statistics that adds value to this study. The persons who are arrested during the collection stage are those individuals who do the actual poaching, such as the 414 poachers who were arrested in South Africa. There is little reference to arrests outside South Africa of other players, like international receivers, kingpins and distributors in other jurisdictions like Mozambique and the far east. The references to the preventive measures taken, such as the detection and prevention of the movement of rhino horn beyond South Africa's major ports of entry, are to those effected inside rather than outside the Republic.36 The statistics are silent on the legal countermeasures to deal with the detection, arrest and prosecution of individuals engaged in the transportation and distribution of the rhino horn.

Other government organs that are engaged in the prosecution of the persons involved in rhino poaching include the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the National Directorate of Public Prosecutions (NDPP). A look at the NDPP Annual Report for 2016 indicates that there was a high conviction rate of 88.9% (359 convictions as at 31 May 2016).37 While this resonates with the conviction rate of 88.8% alluded to by the DEA, a contradiction is evident where the NDPP Annual Report for 2016 shows that the 46 convictions for the year involved 15 Mozambiqans. However, if this contradiction is to be tested against the results for a different year, perhaps for 2015, for instance, one finds disturbing detail in the rhino poaching statistics. The killing of 1175 rhinos that led to 317 arrests resulted in the conviction of only 48 accused out of the 54 (17 per cent of the arrests) who were prosecuted. 38 It is absurd to conclude on the basis of the prosecution of 17 per cent of the arrested persons that there is a conviction rate of 88 per cent. This mode of calculation of the conviction rates does not offer a useful approach to dealing with all the challenges in rhino poaching.

These contradictory reports are silent regarding any successes beyond the borders of South Africa with regard to transportation and distribution. The need for caution has to be emphasised.

3 An evaluation of the current legislative framework

This section looks at the legislative framework before the enactment of the POCA, the position of the POCA in the light of other principles of criminal law, and other interlinking factors.

3.1 Legislative framework

A look at other laws that deal with environmental crimes is instructive in presenting a contextual background that justifies the argument that the provisions of the POCA should be amended.

3.1.1 National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998

The National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA) deals with issues of corporate governance, integrated environmental management, and issues of international obligations and duties.39Furthermore, the NEMA provides a framework within which to carry out activities that are sanctioned by the Minister and accords powers to the latter to create offences for the contravention of the Act.40

With regard to offences, it prohibits individuals from engaging in listed activities without the permission of the Minister.41 Particular regard is placed on section 25, which creates guidance on the creation of offences. The relevant provision provides that:

The Minister may introduce legislation in Parliament or make such regulations as may be necessary for giving effect to an international environmental instrument to which the Republic is a party, and such legislation and regulations may deal with inter alia the following-

...implementation of and compliance with the provisions of the instrument, including the creation of offences and the prescription of penalties where applicable;...42

This subsection requires the enactment of legislation for the implementation of and compliance with an international instrument and criminalises prohibited conduct. There is no guidance on how to deal with cases involving suspects who are beyond South Africa's borders.43 It is correct to state that the NEMA fails to address issues of organised crime, extraterritorial jurisdiction, and wildlife crimes with regard to higher echelons outside the jurisdiction of South Africa.

On a positive note, it is worth noting that some provinces in the Republic have enacted legislation that can be used to prosecute the various players in rhino horn poaching. For instance, Limpopo Province enacted the Limpopo Environmental Management Act (LEMA),44 which consolidates and amends the environmental management legislation and incidental matters in Limpopo Province.45 The LEMA has been put to the test and applied in a number of cases.46

3.1.2 National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004

The National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004 (NEMBA) provides a statutory framework for the management and conservation of the Republic's biodiversity as dealt with in the NEMA. 47Against this background, the NEMBA offers two plausible steps with regard to the prosecution of rhino poachers. First, it restricts dealings in endangered species. 48 Secondly, it empowers the Minister to prepare a list of endangered species.49 Just like the NEMA, the NEMBA does not deal with incidents that occur outside the borders of the Republic.50 However, the NEMBA still fails to address issues of the prosecution of persons who are higher echelons involved in organised crime, and/or in extraterritorial spaces. An example of this shortfall is illustrated below:

A person may not carry out a restricted activity involving a specimen of a listed protected species without a permit issued in terms of Chapter 7.51

The wording of the section indicates a criminalisation of particular activities within South Africa's borders. It fails to capture instances where the person involved in the poaching is outside the borders of the Republic. The lack of guidance on extraterritorial jurisdiction with regard to the prosecution of higher echelons is a great limitation in the fight against rhino poaching. Closely linked to the NEMA and the NEMBA is the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act (NEMAPAA),52 which provides for the management and governance of protected areas and their usage.53 The key consolidating feature lies in the emphasis on poaching within South Africa's borders.

3.1.3 Criminal Procedure Act 55 of 1977

The Criminal Procedure Act has safeguards that ensure the effective prosecution of serious offences that are listed in schedule 5. The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) has to consent to the prosecution of these offences, and exceptional circumstances have to be proved by an accused before he or she is granted bail. The list of serious offences includes rape, murder, particular kinds of organised crime such as trafficking by commercial careers, drug trafficking, and the smuggling of ammunition. However, dealing in endangered species such as poaching is not recognised as among the schedule 5 offences.54 This is an indication that the safeguards accorded to serious crimes do not extend to dealing in endangered species or the offences under the POCA. In addition, the safeguards under the Criminal Procedure Act ensure that there is a streamlined process that governs the institution, process and final determination of offences, where the accused is in South Africa. There is no reference to bringing the higher echelons to South Africa or any other foreign court for trial in instances of rhino poaching in the Republic. While the implications of listing the offence of dealing in endangered species as a schedule 5 offence aid effective prosecution, a higher echelon from another jurisdiction cannot be subjected to these safeguards.

3.1.4 International Cooperation in Criminal Matters Act 75 of 1996

The International Cooperation in Criminal Matters Act (ICCMA) deals with facilitating the provision of evidence, the execution of sentences in criminal matters, and the confiscations and transfer of the proceeds of crime between South Africa and foreign States.55 Its objectives are:

To facilitate the provision of evidence and the execution of sentences in criminal cases and the confiscation and transfer of the proceeds of crime between the Republic and foreign States, and to provide for matters connected therewith.56

The cumulative effect of the scope of the ICCMA does not go beyond the three aspects of the provision of evidence, the execution of sentences and the transfer of the proceeds of crime. This is an indication that instances of the commission or aiding and abetting of a crime by an individual who is outside the Republic cannot be prosecuted with the aid of the ICCMA.57

In addition, this Act deals with the procedures related to the admission of evidence, and with other subsequent court matters. It should be stated that it offers support in instances where rhino poaching has occurred at the three levels and the evidence that needs to be used has to be obtained from outside of the jurisdiction. The shortcoming of the ICCMA lies in its failure to deal with an offence that starts in the Republic and continues beyond South Africa's borders. The advantage that the ICCMA provides is its ability to ensure that orders made by foreign states in the course of criminal prosecution may be registered and enforced in South Africa.58 As such, it is argued that the ICCMA then may aid only the admission of evidence from outside the Republic and the enforcement of foreign judgments where the culprits have been prosecuted and convicted abroad.59 It is at this point that a law that offers extraterritorial jurisdiction may come in handy.60

It is worth noting that the POCA amends the ICCMA by providing new definitions of a confiscation order and a restraint order.61 In addition, the POCA repealed the Proceeds of Crime Act 76 of 1996.62 Before the repeal was effected, the Proceeds of Crime Act was limited to the recovery of the proceeds of crime and the prohibition of money laundering63 through the provision of confiscation orders64 and restraint orders,65 and the realisation of property.66 The effect of the amendments introduced by the POCA extended the initial application of the Proceeds of Crime Act by providing for offences relating to organised crime, racketeering activities, the proceeds of unlawful activities, and criminal gang activities.67 Usually, the poaching of rhinos is an organised crime that includes various players, right from the collection stage, through the transportation stage, to the distribution stage.68As such, while the amendments by the POCA aid its effectiveness in the prosecution of wildlife crimes, they still offer no concrete guidance on how to deal with the prosecution of higher echelons.

3.1.5 South African Police Service Act 68 of 1995

The South Africa Police Service Act (SAPSA)69 has a list of activities that indicate the recognition of organised crime. It states that the recognition as such of activities

by a person, group of persons or syndicate acting in -

(i) an organised fashion; or

(ii) a manner which could result in substantial financial gain for the person, group of persons or syndicate involved70

in respect of the hunting, importation, exportation, possession, buying and selling of endangered species or any products thereof as may be prescribed;71

in more than one province or outside the borders of the Republic by the same perpetrator or perpetrators, and in respect of which the prevention or investigation at national level would be in the national interest.72

The above circumstances acknowledge that organised crime networks have an existing organised structure that functions for financial benefit. In addition, the benefits in this context result from dealing with endangered species, and there is a need for transnational cooperation in conducting investigations. In addition, the SAPSA elaborates on the notion of an "organised fashion" as the ongoing, continuous or repeated participation in at least two incidents of criminal activity.73 It would appear that this qualification is for the purpose of qualifying a crime as organised crime rather than for the purpose of the prosecution of the culprits.

A comparison of the list in the SAPSA with the definition of a criminal gang in the POCA indicates that this organised structure may be either informal or formal. Secondly, the members engage individually or collectively in criminal activities. The point of contention is the existence of either a name or an identifying symbol. While the SAPSA provides this definition, it does not criminalise the activities that would form organised crime, requiring extraterritorial jurisdiction. This informs the decision to evaluate the POCA as the law that deals with organised crime.

3.1.6 Extradition Act 67 of 2002

In addition, the Extradition Act allows for ad hoc arrangements in the absence of an extradition agreement, where there is a request for the surrender of a person.74 The purpose of extradition is to ensure that persons who have committed a crime in country A and are within the jurisdiction of country B may, upon a request by A, be moved from country B to country A to be prosecuted. The author is not aware of any extradition agreements between South Africa and the Asian States of Vietnam or China. This poses great challenges with regard to the prosecution of the higher echelons of those involved in rhino poaching. Nonetheless, an examination of the position with regard to extradition in the three countries is instructive in placing the study in context. There is a need to establish whether an ad hoc arrangement is an international agreement.

The South African Constitution allows the President of South Africa to enter into international agreements on behalf of the Republic,75 such as extradition agreements.76 The international agreements, however, have to be domesticated through an approval by resolution of the National Council of Provinces and the National Assembly.77 The failure to obtain this approval renders any application of the agreement void.

Before the question of whether an ad hoc arrangement is an international agreement is answered, it should be noted that there are international law principles that may be used to ensure the prosecution of a citizen of one State in another. One of these principles is comity, which is described as:

... a set of reciprocal norms among nations that call for one state to recognise, and sometimes defer to, the laws, judgments, or interests of another. Comity is a regime of intergovernmental courtesy.78

Flowing from this definition, it is envisioned that South Africa, Mozambique, and Far East countries such as Vietnam recognise the interests that each country has with regard to rhino poaching. The concluded Memorandums of Understanding with some States such as Vietnam lack the required guidance with regard to the prosecution of persons outside South Africa's borders.79

As earlier stated, the ad hoc arrangements in the absence of an extradition agreement may be used where there is a request for the surrender of a person.80 While the process is subject to the same rules that apply to an extradition treaty, it is required that the President considers the request for the surrender and offers his written consent.81 This occurred in Harksen v President of the Republic of South Africa, where in the absence of an extradition agreement the President consented to the extradition of Harksen, a German national, to Germany to face trial.82 In the Harksen case the Constitutional Court stated that the ad hoc arrangement by South Africa to extradite Harksen to Germany was not unconstitutional as far as it was not an international agreement that required ratification by Parliament.83 It should be stated that while the President may conclude ad hoc extradition treaties, these remain to be domestic engagements that do not require parliamentary approval. This position solves the silence of the Constitution on domestication, and indicates that ad hoc agreements are domestic engagements rather than international agreements.

It is prudent to examine the use of ad hoc agreements where associated States are involved. According to the Extradition Act, four principles govern engagements with associated States. First, there should be an existing extradition agreement that provides for the endorsement for execution of warrants of arrest on a reciprocal basis.84 Secondly, a magistrate in the associated State before whom a warrant is issued for the arrest of any person to be surrendered to the associated State is required to endorse the warrant for execution.85 Thirdly, the warrant is endorsed regardless of the whereabouts or suspected whereabouts of the person to be arrested.86Fourthly, the Magistrate has to be satisfied that the warrant was lawfully issued.87

These principles should be reflected in the laws of extradition of the associated States. If this is asserted in the affirmative, then the first requirement of a subsisting extradition agreement is solved. Although the author is not aware of any subsisting agreement between South Africa and Mozambique,88 it is argued that this lack is solved by the application of the Extradition Act to ad hoc arrangements.89 The reading of sections 6, 5 and 11(b) points to a person to be extradited to South Africa, other than from associated States to the Republic. The application of the remaining principles requires that there should be similar provisions in the extradition laws of associated States and the willingness to enforce them.90 The current law of extradition in Mozambique lacks similar provisions.91

3.1.7 CITES and UN Resolutions

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) offers international resolutions that require a legal framework that embraces the prosecution of organised crime. The importance of these resolutions lies in the call for States Parties to embrace international cooperation with regard to illicit trafficking in wildlife and corruption. States Parties to CITES recognise that corruption plays a significant role in facilitating wildlife crime92 with the close involvement of organised crime groups.93 It is on this basis that the States Parties stress the need to undertake measures that ensure the effective implementation of the Convention,94 through administration, regulation, implementation or enforcement through the use of adequate penalties under domestic legislation.95

This resolution notes that the three main chains in illicit wildlife trafficking involve the source, transit and market countries, which are facilitated by corruption at all these levels. An emphasis on dealing with corruption is not an end in itself as far as there are other aspects that contribute to the continued trafficking of wildlife like the lack of a law that adequately deals with extraterritorial jurisdiction. Despite this position, it is worth noting that the resolution encourages the use of national enforcement agencies that have a cross-border effect like the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).96 The weight is still on the State Party to embrace such initiatives and convert them into an enabling law that leads to the prosecution of the higher echelons.

A recent UN resolution on tackling illicit trafficking in wildlife calls on the Member States to take decisive steps at the national level to prevent, combat and eradicate illegal trade from both the supply and demand sides.97This requires the recognition that while the supply might be from the Republic, the demand is beyond its borders. This creates complications with regard to the prosecution of the perpetrators at the source of the supply and at the end of the demand chain. It is on this basis that the resolution calls for the strengthening of legislation that deals with the prevention, investigation, prosecution of perpetrators and the increased sharing of information and knowledge among national and international authorities.98This resolution fails, however, to tackle the challenge that wildlife-related offences are largely transnational crimes that require cooperation from various State Parties to bring the higher echelons to justice.

3.2 An evaluation of the POCA

A good criminal law should clearly identify the prohibited conduct and describe the punishment for it. This is based on the principles of nullum crimen sine lege and nulla poena sine lege.99Against this background, where a law fails to prescribe the prohibited conduct, it becomes a challenge to punish those who commit it.100 The failure by a law to deal with such conduct is a challenge, especially where it is the result of jurisdictional challenges. These challenges include the situation where an individual in another jurisdiction aids and abets the commission of an offence by an individual in the local jurisdiction, such as the Republic of South Africa. This presents procedural problems, such as drafting the charges, which are expected to indicate the place and time where the offence was committed. This situation is exacerbated where it is necessary to prosecute an individual who was outside South Africa's geographical borders at the time of the commission of the offence.

3.2.1 Challenges to the application of the POCA

The POCA was enacted at a time when the various criminal laws that deal with recovery and forfeiture were inadequate to effectively deal with organised crime, money laundering and the activities of criminal gangs.101Thus, while the POCA set out to provide a statutory framework to deal with this loophole, it is yet to be seen how it adequately deals with organised crime. The POCA presents two challenges in its application. First, it is used to aid the addition of charges where transnational organised crime is involved. For instance, where one is charged with fraud102 and forgery;103counts of money laundering may be placed as additional charges.104

The drawback in implementing this approach lies in the way organised crime works:

...it is usually very difficult to prove the direct involvement of organised crime leaders in particular cases, because they do not perform the actual criminal activities themselves, it is necessary to criminalise the management of. and related conduct in connection with enterprises which are involved in a pattern of racketeering activity:105

While this recognition is instructive, the success of the POCA depends on how it deals with the higher echelons of those involved in rhino poaching who are beyond the borders of the Republic.

The reasons for enacting the POCA, therefore, resonated with the need to reduce organised crime by creating a framework that would ensure that the proceeds of such crime would be dealt with.106 The drafting group of the Prevention of Organised Crime Bill indicated that South Africa's laws before 1998 emphasised the arrest of users, sellers, and key leaders of organised crime.107 Drawing on trends in the United States, the drafting group suggested that repo-legislation be introduced to ensure that the proceeds of organised crime be forfeited.108 This position formed the basis of the enactment of the POCA and limited its application to the proceeds of crime, without engaging the prosecution of those involved in organised crime, such as rhino poaching.109

On the foregoing basis, it is in order to argue that the POCA is used by the prosecution as a tool to include other charges, especially where transnational organised crime is involved. The effectiveness of the POCA in dealing with rhino poaching as a form of transnational organised crime has to be evaluated against the offences that it provides, and their effectiveness in dealing with offences related to rhino poaching. The POCA deals with three kinds of offences: offences related to racketeering,110 the proceeds of unlawful activities,111 and criminal gang activities.112 The main question that follows from the framework of the POCA is whether rhino poaching falls under one of these categories. As noted earlier, rhino poaching involves the collection, transportation and distribution of rhino horn. It follows that the law that regulates organised crime is expected to deal with these three activities, regardless of their geographical location.113

Before undertaking a discussion of the three activities, it should be noted that the POCA does not define organised crime. A look at its drafting history reveals that this is by design, as the drafting group indicated that since there was no universal definition of organised crime, it would be difficult for South Africa to have one.114 The closest definition of organised crime relates to a criminal gang. The POCA states that a criminal gang includes

... any formal or informal ongoing organisation, association. or group of three or more persons, which has as one of its activities the commission of one or more criminal offences, which has an identifiable name or identifying sign or symbol. and whose members individually or collectively engage in or have engaged in a pattern of criminal gang activity.115

This definition stipulates the four ingredients that inform the existence of a criminal gang: a formal or informal organisation, involved in the commission of offences, with an identifiable name or symbol, and whose members are either individually or collectively involved in the criminal activities.

While the POCA provides for offences related to racketeering.116 It does not define the concept. In the first schedule to the POCA117 it describes the pattern of racketeering activity as the planned, on-going, continuous or repeated participation in an offence. The first schedule provides for dealing in or being in possession of or conveying endangered game in contravention of a statute or provincial legislation.118 In addition, the POCA criminalises the engagement in racketeering activities within and outside South Africa.119It would be expected that the provisions in the first schedule to the POCA and the provision of extraterritorial jurisdiction for racketeering activities would place rhino poaching within the bounds of the Act. The offences related to racketeering are not complete unless the person receiving the property uses it to advance illegal activities.120 It would appear that a once-off criminal activity that does not involve the use of its proceeds to further illegal activities is not an offence. It follows that extraterritorial jurisdiction for racketeering activities does not include jurisdiction over rhino poaching unless it has realised proceeds that may be intercepted by the operation of the POCA. Some of the instances of racketeering activity that may be ongoing or continuous include running Ponzi schemes121 or engaging in various criminal activities in an organised manner.122

The POCA provides for a mode of dealing with the proceeds of unlawful activities as defined in section 1.123 The offences include money laundering,124 aiding an individual to benefit from the proceeds of illegal activities,125 the acquisition, possession and use of the proceeds of unlawful activities,126 and the failure to report suspicions regarding the proceeds of unlawful activities.127 Just like racketeering, the POCA provides under chapter 3 for extraterritorial jurisdiction to assist the prosecution. It is also intent on dealing with the proceeds of illegal activities, other than the illegal activities themselves. This in effect defeats the purpose of reducing the incidence of rhino poaching, if the law requires that there should be proceeds of illegal activities as a condition that precedes prosecution.

With regard to criminal gang activities,128 the POCA offers clarity on what they entail. These include the illegal actions or omissions by members of the gang on third parties, by means of actual violence or threats.129 In addition, the continued existence of the gang should be evident from its criminal activities or the conscription of persons to join it.130 While a literal interpretation shows that the section seeks to deal with the existence of the gang, it does not mean that the other activities of the gang, like rhino poaching, are not dealt with. An individual's participation in the activities of a gang is an offence under the POCA.

In the interim, the POCA has the following shortcomings. First, the offences of racketeering activities and the proceeds of unlawful activities as defined in s 1 pertain to the benefits that accrue from illegal activities and their use to advance illegal activities. This is an indication that unless the State proves to the court that a higher echelon involved at the transportation or distribution levels uses proceeds to enable the criminal gangs in the collection level to acquire more rhino horn, he or she may not be prosecuted under the POCA. Secondly, the extraterritorial jurisdiction for offences in the two categories is with regard to the proceeds obtained, and how appropriate orders may be applied to deal with them.131 Other than the proceeds obtained, the POCA cannot be used to deal with activities related to rhino poaching outside the Republic.

3.2.2 Modes of criminal liability as an alternative ?

While the POCA sought to amend particular acts, these amendments have suffered practical limitations in enforcing the criminal liability of all the key players in rhino poaching.132 There are various principles of criminal law in relation to modes of liability such as aiding and abetting, conspiracy to commit an offence, common purpose and accessorial liability which need to be interrogated.133 It is argued that unless these principles are developed to have extraterritorial application, they cannot be applied to rhino poaching or wildlife offences in general. To substantiate this, the author interrogates the use of common purpose in prosecuting the higher echelons.

In South Africa persons may be taken to participate in the commission of an offence where it is shown that they formed a purpose to commit the offence, directly or indirectly. According to the common purpose doctrine, the prosecution has to prove beyond reasonable doubt that each accused had the requisite intention with respect to the unlawful outcome at the time of the commission of the offence.134 This is an indication that the higher echelon should have intended the criminal act of poaching the rhino as the intended criminal result of their facilitation of the process through the provision of logistics for this purpose. This position rhymes with the definition that where "two or more persons agree to commit a crime or actively associate in a joint unlawful enterprise, each will be responsible for specific criminal conduct committed by one of their number which falls within their common design."135

One may ask the question, what informs the common purpose. This is pretty straight forward - a prior express or implied agreement before the commission of the offence.136 The limits of its application are in relation to extraterritoriality, where an individual participates in a location where the court does not have jurisdiction. While the common purpose doctrine would be instructive, its extraterritorial application is limited. A good example is where a person commits the offence of theft outside South Africa and then maintains the possession of the property herein.137 The lack of extraterritorial jurisdiction in the wording affects the use of common purpose in prosecuting higher echelons. This is exacerbated by the limited nature of the extraterritorial jurisdiction that is provided for under the POCA.138 As such, the doctrine of common purpose can be used only where the penal laws of the States that harbour higher echelons enable the prosecution of offences where their participation starts in another jurisdiction (like South Africa) and continues to that jurisdiction (like Vietnam).139

Furthermore, the challenge to combatting rhino poaching lies in its nature as a transnational other than an international crime. The prosecution of the higher echelons in an international crime is accomplished by the use of universal jurisdiction, regardless of where the criminals are located.140Conversely, the prosecution of transnational crime requires interstate cooperation.141 The existence of limited cooperation affects the already limited extraterritorial jurisdiction.142 Furthermore, where there are limited interstate transnational values, the emphasis attached to the prosecution of rhino poaching is not the same in other States.143

3.2.3 Use of the aut dedere aut judicare principle: an alternative?

Another possible alternative is the use of the aut dedere aut judicare doctrine. Although this principle is used by the International Criminal Court in the context of war crimes, it is instructive in contextualising the need for extraterritorial jurisdiction.144 This principle requires that a State with the custody of an international offender has a duty to either prosecute or to extradite him or her to another State to face trial. This principle draws legitimacy from international treaties that are signed to secure the prosecution of war crimes145 and crimes against humanity.146

It should be noted that the principle may be applied outside the scope of crimes against humanity and war crimes on the basis of the relationship between the principle of aut dedere aut judicare and human rights. First, the enforcement of human rights requires that the protection of the impugned rights be subjected to the prosecution of perpetrators.147 Secondly, where national crimes attract a level of international concern, the obligation to use the principle should suffice.148 In this regard, where the crime that is transnational in nature affects the social, economic, cultural and other interests of all or a substantial number of States and involves private individuals or group conduct, the aut dedere aut judicare principle may be used.149 In this regard, the international criminalisation of poaching in endangered species by CITES should be viewed as an international concern with rhino poaching as a national crime.150

One may argue that the challenges to the application of the principle in the national sphere lie in a State's discretion to balance its sovereignty on the one hand and extradition on the other;151 or where its punishment for the criminal conduct amounts to torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.152 These challenges are solved by the level of international concern that the crime attracts.153 The South African Constitutional Court has pronounced its support for the non-imposition of punishments that amounts to torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.154 The issue of the severity of the punishment in the context of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, therefore, does not arise.

Despite the likelihood of overcoming the challenges to the application of the aut dedere aut judicare principle, South Africa's position in the fight against rhino poaching needs to be contextualised. Where the higher echelon is in a country other than South Africa, his or her successful prosecution lies with the prosecutorial authorities in that State. South Africa cannot seek to prosecute the perpetrator beyond its borders. Prosecution can take place only where the interests of South Africa and the other State converge. In addition, at its core this principle requires that the State in control of the person to be investigated surrenders or delivers him or her to be prosecuted in the State seeking extradition. This requirement should be in its domestic law or in an international treaty to which both the requesting State and the State in custody of the perpetrator are parties.155

Some scholars argue that this obligation does not necessarily refer to investigations. It is suggested that investigations should be done where there is adequate evidence to prosecute the offence before it can be prosecuted in the State where the accused is located. Where the offence in the State that is holding the higher echelon is radically different, it is necessary to extradite the person to the other State, where he or she will be prosecuted.156 This brings one back to the position that the lack of an extradition agreement on rhino poaching with either Mozambique or Vietnam negates the chances of the possible prosecution of an accused in South Africa.

The lack of treaties that codify the criminalisation of particular conduct denies the State in need of this treaty the legal effect of such codification, and as such there is no binding engagement with the State that harbours the perpetrators.157 It is rather unfortunate that while the origin of a transnational criminal law norm is international, its penal proscription is limited to national jurisdiction, making its application an uphill task.158

3.3 Steps by CITES

Recent decisions taken at the 17 Conference of the Parties to the CITES are important to this conversation. They offer guidance to States Parties, the CITES Secretariat, range Parties, Mozambique and Vietnam.159 The Secretariat requires all parties to review their implementation and strategies related to the effectiveness of the law-enforcement response to rhino poaching and trafficking.160 While this is a welcome development, it requires a concerted effort to have the effects of the review felt across the board. This is especially true where the level of emphasis on a particular wildlife species in one State is not commensurate to the level of emphasis in others.

Secondly, all rhino range States have a duty to always review poaching and trafficking trends, such that the preventive and combating measures are effective, adaptive and responsive to new trends. 161 This speaks to the need for vigilance in prosecution,162 mutual cooperation and enforcement through various measures such as extradition,163 and the use of strategies that counter the killing and trafficking of rhinos.164 The duties placed on range States reflect the key concepts informing this contribution, namely effective prosecution, mutual cooperation and extradition. These duties require that the range States either prosecute the higher echelons on the basis of their violations of South Africa's environmental penal law, or extradite the offenders to the Republic. Secondly, they ought as far as possible to attach the same emphasis that South Africa and the States Parties to CITES attach to the prohibition of rhino poaching. This is evident in the Secretariat's duty to conduct visits to Mozambique and Vietnam to review arrests, seizures, prosecutions, and convictions.165 This approach suggests the need to appreciate the socioeconomic constructions that the two countries attach to rhino horn. While the Mozambican perpetrators benefit financially from illegal transportation, Vietnamese society believes in the medicinal benefits that rhino horn accords it. This has to be contextualised in the move to ensure effective prosecution, mutual cooperation, and extradition. These steps have shown that the question of the effectiveness of the current legal regimes of the States Parties to ensure that a higher echelon resident in a range State can be tried is lacking.

4 Use of extraterritorial jurisdiction

In view of the challenges described above as being evident in the operation of the POCA with regard to the prosecution of culprits with regard to endangered species, it is prudent to contextualise extraterritorial jurisdiction and indicate how it may be used.166 This is premised on the fact that China, Vietnam, Mozambique and South Africa are all signatories to CITES.167 In addition, there is an MoU between South Africa and Vietnam where the two countries identify illegal wildlife trafficking as a global challenge that requires cooperation in the enforcement of and in compliance with CITES.168 Other than agreeing on the need for compliance with CITES, the two countries do not agree on the prosecution of cases beyond their borders.169 It is important to note that the forms of cooperation do not specifically include the prosecution of persons engaged at the three levels of rhino horn poaching as indicated above.170 It should be noted, however, that the two States agree that other forms of co-operation may be mutually agreed upon by them, subject to their domestic legislation. The relevant Article provides for other forms of cooperation as shall be mutually agreed upon by the Parties subject to the Parties domestic legislation and available funding.171 While this provision is a welcome development, it poses two challenges. First, it does not specifically speak to wildlife offences like rhino horn poaching. Secondly, the author is not aware of any provision in the POCA that may be used to prosecute such individuals under this MoU.172 On a lighter note, the decisions by the CITES Conference of Parties and the recent adoption of new environmental penal laws in Vietnam are steps in the right direction. This aids the pursuit of logical avenues to prosecute trafficking in rhino horn as a challenging transnational crime.

There is a need to pursue the possible prosecution of all the players in the rhino horn syndicates. There are examples of States that have used extraterritorial jurisdiction to deal with instances of environmental crime. For instance, the United States (US) Lacey Act Amendments of 1981 provided for measures that made it unlawful to import, export, sell, acquire, or purchase fish, wildlife or plants taken, possessed or sold in violation of a State or foreign law.173 Thus, it provided for extra-territorial action. Instead of creating an offence to violate US national law elsewhere, the Act prohibited the violation of the laws elsewhere, to be prosecuted in the US.174In addition, in March 1998 Norway required all Norwegian registered companies or vessels conducting business outside its territorial waters to register for a period of one year.175 In the event that a vessel was removed from the register for the contravention of conservation or management measures laid down by regional or sub-regional agreements, it lost access to all quotas it stood to benefit from in the domestic and cooperative fisheries.176

These historical successes indicate that South Africa and the range states can use extraterritorial jurisdiction to prosecute offenders who are arrested outside its jurisdiction. An arrangement on extraterritorial jurisdiction that goes beyond recovering the proceeds of organised crime is instructive. In addition, to effectively utilise extraterritorial jurisdiction, one has to establish the nature thereof that is needed by South Africa to ensure that there is optimal prosecution of the higher echelons of those involved in rhino poaching. The question is how this extraterritorial jurisdiction may be applied. The answer lies in a brief unpacking of the concept of jurisprudence. Jurisdiction may be of a prescriptive, adjudicative or enforcement nature.177 With regard to the enquiry being undertaken in this article, adjudicative jurisdiction is instructive insofar as it involves the power to subject persons or things to a judicial process.178 In this regard, there is a need to subject the higher echelons of those involved in rhino poaching to prosecution both in respect of their personal involvement and/or the rhino horn as the subject of their activities.

In addition to the above, with regard to extraterritorial jurisdiction, international law has developed principles on territoriality. First, any one State may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State, unless there is a rule making that possible; and secondly, States have a wide discretion to exercise jurisdiction within their own territory in instances where there are acts or omissions that have been committed outside their borders.179 With regard to the first principle, the then Permanent Court of International Justice stated:

Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that - failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary - it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from a convention.180

This indicates that in international law the existence of a permissive rule allows a State to exercise its jurisdiction over an act that occurs in another State. The question that follows with regard to the scope of the permissive rule is whether a State's enforcement of jurisdiction in respect of acts committed in another State is based on the existence of the permissive rule or the lack of a prohibitive rule. This question resonates with the presumption that what is not prohibited under international law is permitted.181 It follows that there is a lack of clarity with regard to the application of the permissive rule due to changing strands of either sovereignty or interdependence. While it may be argued that the SS Lotus case of France v Turkey (the Lotus case) postulates a position that international law is either a system of permissive or prohibitive rules,182 this conclusion does not reflect the majority opinion, leading to the development of the Lotus principle. The majority opinion presented States as independent communities that need to ensure co-existence by recognising equal sovereignty as the basis for any restriction on the exercise of their sovereignty.183 As a result, the principle that permissiveness should be based on a State's discretion to consent to an act of extraterritorial jurisdiction in exercise of its sovereignty indubitably has to be linked to its interdependence.184 Therefore, international law is not a system of permissive or prohibitive rules as the Lotus principle suggests, but rather a collection of independent States that co-exist.185 It follows that this coexistence assists in the balancing of rights and interests between States in the sphere of international law.

The application of extraterritorial sovereignty by South Africa with regard to acts committed by the higher echelons of those involved in organised crime should not be seen as an act that undermines the sovereignty of other States, such as Mozambique and Vietnam, but rather as an act that requires the interdependence of sovereign States affected by rhino poaching. There is a lot of scholarly literature that calls for co-existence and interdependence in fighting environmental crime, which is instructive in creating a basis for extraterritorial jurisdiction to fight it.186

In addition to the discussion on the permissive rule, consider this hypothetical situation that illuminates the concept of extraterritoriality. Poacher A poaches rhino horn and transmits it to a receiver B. This receiver then transports the horn beyond South Africa's jurisdiction to an international receiver C. The international receiver transmits the rhino to a kingpin D, who then uses the distributor E to transfer the product to the consumer F. This hypothetical scenario indicates that while poacher A and the receiver B are within South Africa's borders, the international receiver C, distributor E and consumer F are beyond South Africa's borders. A localisation of a particular transaction informs the choice of jurisdiction. If one places emphasis on where the transaction started, then A and B are prosecuted in South Africa due to South Africa's prescriptive jurisdiction as a result of its national laws.187 With regard to the transaction that forms the effect of the crime, that is the transmission of the rhino horn to the persons C, D or the distribution to E and F, their prosecution may be undertaken in the respective countries without any need for extraterritorial jurisdiction.188The question that needs to be answered is why C and D should not be prosecuted in the Republic.

Before one engages with the possible prosecution of C and D in the Republic, this hypothetical situation poses a plethora of challenges. First, other countries may not criminalise the conduct of C and D. For instance, Mozambique and Vietnam do not have laws that deal with Organised Crime Groups with regard to international receivers, kingpins and distributors of rhino horn.189 However, Vietnam's Penal Code provides for offences against regulations on the management and protection of endangered and rare animals within its jurisdiction. The Section states:

1. Any person who violates regulations on management and protection of animals on the List of endangered and rare species; endangered, rare animals of Group IB or in Appendix I of CITES in any of the following cases shall be liable to a fine of from VND 500,000,000 to VND 2,000,000,000 or face a penalty of 01 -05 [sic] years' imprisonment:

a) Illegally hunting, killing, imparking, [sic] transporting, trading animals on the List of endangered and rare species;

b) Illegally storing, transporting, trading animals specified in Point a of this Clause or body parts thereof; from 02 kg to under 20 kg of elephant tusks; from 0.05 kg to under 01 kg of rhino horns.190

The section is silent on dealings in an endangered animal or animal products from outside the country's jurisdiction. One may argue that the problem that South Africa is dealing with in regard to the higher echelons of those involved in such conduct is not adequately dealt with under Vietnam's Penal Code either.

Secondly, and as noted earlier, the States in issue may not attach similar emphasis to rhino horn poaching as South Africa does. While South Africa has taken various initiatives to curb rhino poaching, such as the establishment of an environmental investigative task force, the monitoring of rhino populations, the prosecution of alleged offenders, and the forfeiture of assets that arise from the trade, other countries have not taken such initiatives.191 In this regard, a look at Mozambique's position on environmental crime is instructive due to the challenges that arise from its limited initiatives in comparison with South Africa. Mozambique's Conservation Law provides for a maximum prison sentence of 12 years for poaching protected species.192 However, this harsher sentence does not appear to apply to wildlife trafficking cases. In addition, the Conservation Law does not define the protected species.193 Research indicates that the limitations implicit in these initiatives have dire effects on dealing with rhino horn poaching. While 539 alleged poachers were arrested between 20122014, the convictions led to the imposition of 17 fines and no custodial sentences.194 While a Report by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Rhino Specialist Groups and Trade Records Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce (TRAFFIC) to CITES' 17th Conference of the Parties (CoP17) showed that high-ranking law enforcement officers were arrested for armed robbery and trafficking in rhino horn, they were released on bail.195 In addition, a Vietnamese citizen who had initially been arrested at Maputo Airport going to Kenya with seven rhino horns in May 2012 was later detected a week later at Bangkok's international airport in transit from Kenya to Hanoi with the horns.196 As a result, the different initiatives in Mozambique, Vietnam and South Africa justify the need for the Republic's adoption of another approach in the direction of extraterritorial jurisdiction. South Africa has to engage other countries through the strategic use of extraterritorial jurisdiction to deal with the international receivers, kingpins and distributors.

As such, a treaty or extradition arrangement offers the platform of extraterritorial jurisdiction to deal with rhino poaching. At their core is the prosecution in South African courts of the higher echelons arrested in the range States. This would aid the effective use of modes of criminal liability such as common purpose. The use of extraterritorial jurisdiction embraces the definition of poaching and poachers by the NISCWT with regard to the individuals who are involved in the collection, transportation and distribution of rhino horn. It offers an opportunity to enhance the second and third objectives of the NISCWT, which require that a lot of the prevention and promotion be done outside the borders of South Africa.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

An evaluation of the current legislation shows that all the provisions deal with the prosecution of rhino poachers who are inside South Africa. This conclusion is buttressed by the evaluation of the use of common purpose as a mode of criminal liability, which still requires the accused to be within South Africa for it to be effected. Furthermore, other principles like the use of aut dedere aut judicare are not effective in so far as they are not entrenched in the legislation that provides for offences that aid rhino poaching. It seems clear that there is a need for ad hoc arrangements or other modes of mutual assistance to ensure that the accused is either brought to South Africa for prosecution or tried in the range States for his role in the poaching.

In addition, the recent recommendation by the DEA on compliance and the enforcement of wildlife offences still falls short of leading to the effective prosecution of higher echelons.197 As stated earlier, the addition of offences in the POCA to schedule 5 of the Criminal Procedure Act simply makes the trial process more effective with regard to the accused who are in South Africa.198 The higher echelons are still effectively not prosecuted due to a lack of extraterritorial jurisdiction.

The achievement of logical solutions to rhino horn poaching has to take place through the use of both long-term and short-term engagements that speak to the prosecution of all the players in the poaching nexus. The first logical step is to use the multinational or bilateral treaties that provide for judicial or quasi-judicial jurisdiction. In this context it is desirable that any MoU clearly provides for the investigation and prosecution of the players in the rhino horn nexus from the first to the second and third hierarchies. While the bilateral agreement may be achieved through MoUs, extradition treaties, or further engagements with CITES, a provision that provides for the prosecution of the higher echelons of those involved in rhino poaching for their involvement per se rather than for their use the proceeds of their crimes is the preferred and most effective course of action to pursue.

In addition, the establishment of ad hoc extradition arrangements between South Africa and other affected countries should be encouraged through the diplomatic channels to enable the prosecution of the higher echelons. This will create subsidiary universality, which will enable the prosecution of these people once they are apprehended in territories other than South Africa.199

The existence of these treaties is affected by their failure to deal with the prosecution of the higher echelons of rhino poaching. This failure highlights the need to have this law. Therefore, an amendment to the POCA that provides for the domestication of the multilateral or bilateral treaties should be adopted to ensure that extraterritorial jurisdiction is achieved. This will ensure their prosecution, which will be fortified by the treaties that allow for the extraterritorial jurisdiction. A few initiatives need to be undertaken in order to make it possible to deal with the limitations on the POCA through the use of extraterritorial jurisdiction. First, the offences related to racketeering activities and the proceeds from illegal activities should be extended beyond their current application to the benefits that accrue from illegal activities and their use to advance illegal activities to the actual illegal activities that involve players beyond South Africa's borders. This would enable the prosecution of the international players in the rhino poaching syndicates where the State can prove that a person has transported or distributed endangered species or their products, like rhino horn. In addition, there should be an extension of extraterritorial jurisdiction for offences with regard to the proceeds obtained and the subsequent application of appropriate orders to deal with them to enable the Republic to deal with the offences themselves rather than with the proceeds obtained from the offences.200 The activities (that do not include the application of the proceeds of rhino poaching) of the higher rhino poaching echelons outside South Africa that emerge from the rhino poaching within the Republic would then be adequately dealt with in the POCA. These activities would include the transportation, processing and distribution of rhino horn products. Thus, the activities of the higher echelons that are not expressly subjected to extraterritorial jurisdiction, such as the transportation and distribution of rhino horn, would be provided for. It is thus proposed that the South African Law Commission should undertake a due diligence study of chapters 5 and 6 of the POCA with a view to the provision of extraterritorial jurisdiction for the prosecution of the higher echelons of those involved in rhino horn poaching.

The argument that an amendment to the POCA is flawed. First, the current provisions deal only with the proceeds arising from the crimes instead of with the crimes themselves, which limits the application of the POCA. As a tool, the POCA will be better utilised when the amendment is introduced. The cost of the investigation would greatly be reduced if there were cooperation with other investigative agencies, including sharing evidence and information on the activities that arise from the action of rhino poaching in the Republic.201 In addition, though there are clear instances of political will in Vietnam and South Africa, as shown in the recently signed MoU to cooperate in criminal matters, and to control the sale of the rhino horn in the two countries; a lot more needs to be done.202 This is also evident in the recent step taken by Vietnam to join other countries in signing the London Declaration on the illegal wildlife trade and the introduction of a penal law that prohibits the poaching of the rhino horn.203 This gesture of political will would be self-defeating if Vietnam were not to take practical steps to prosecute these echelons or enter ad hoc engagements to extradite the perpetrators to South Africa to face trial.204

The long-term strategies include engaging with CITES and INTERPOL to remind State Parties to perform their obligations under the treaties, and should be adequately expressed in any extradition treaties or MoUs between South Africa and other countries that deal with the scourge of rhino poaching.

Bibliography

Literature

Ashworth A Principles of Criminal Law 3rd ed (Oxford University Press Oxford 1999) [ Links ]

Boister N "Transnational Criminal Law" 2003 EJIL 953-976 [ Links ]

Boister N An Introduction to Transnational Criminal Law (Oxford University Press Oxford 2018) [ Links ]

Botha N "Rewriting the Constitution: The 'Strange Alchemy' of Justice Sachs, Indeed!" 2009 SAYIL 246-262 [ Links ]

Brownlie I Principles of Public International Law 5th ed (Clarendon Press Oxford 1998) [ Links ]

Burchell J Principles of Criminal Law 4th ed (Juta Cape Town 2013) [ Links ]

Cassese A International Criminal Law (Oxford University Press Oxford 2013) [ Links ]

Colangelo AJ "What is Extraterritorial Jurisdiction?" 2014 Cornell L Rev 1303-1352 [ Links ]

Curley M and Stanley E "Extraterritorial Jurisdiction, Criminal Law and Transnational Crime: Insights from the Application of Australia's Child Sex Tourism Offences" 2016 Bond L Rev 169-197 [ Links ]

De Greef K Booming Illegal Abalone Fishery in Hangberg: Tough Lessons for Small-scale Fisheries Governance in South Africa (Doctoral dissertation University of Cape Town 2014) [ Links ]

Ferreira A et al "The Obligation to Extradite or Prosecute (aut Dedere aut Judicare)" 2013 UFRGSMUN 202-221 [ Links ]

Ferreira-Snyman MP "The Evolution of State Sovereignty: A Historical Overview" 2006 Fundamina 1-28 [ Links ]

Global Financial Integrity Transnational Crime in the Developing World (Global Financial Integrity Washington DC 2011) [ Links ]

Handeyside H "The Lotus Principle in ICJ Jurisprudence: Was the Ship Ever Afloat?" 2007-2008 Mich J Int'l L 71 -94 [ Links ]

Hartnick ER South Africa's Human Rights Centred Approach to Extradition (LLM-thesis University of the Western Cape 2013) [ Links ]

Henzelin M Le Principe de l'Universalité en Droit Pénal International: Droit et Obligation pour les États de Poursuivre et Juger selon le Principe de l'Universalité (Helbing & Lichtenhahn Bâle 2000) [ Links ]

Hertogen A "Letting Lotus Bloom" 2015 EJIL 901-926 [ Links ]

Hübschle AM A Game of Horns: Transnational Flows of Rhino Horn (International Max Planck Research School on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy Cologne 2016) [ Links ]

Katz A "The Incorporation of Extradition Agreements" 2003 SACJ 311-322 [ Links ]

Kemp GP "Foreign Relations, International Cooperation in Criminal Matters and the Position of the Individual" 2003 SACJ 370-392 [ Links ]

Liddick DR Crimes against Nature: Illegal Industries and the Global Environment (Praeger Santa Barbara 2011) [ Links ]

Lowe V and Staker C "Jurisdiction" in Evans MD (ed) International Law 3rd ed (Oxford University Press Oxford 2010) 313-339 [ Links ]

Morktar A "Nullum Crimen, Nulla Poena Sine Lege: Aspects and Prospects" 2005 Stat LR 41-55 [ Links ]

Mujuzi JD "The South African International Co-operation in Criminal Matters Act and the Issue of Evidence" 2015 De Jure 351-387 [ Links ]

Mujuzi JD "The Prosecution in South Africa of International Offences Committed Abroad: The Need to Harmonise Jurisdictional Requirements and Clarify some Issues, Generally" 2015 AYIHL 96-117 [ Links ]

Nanima RD "Prosecution of Rhino Poachers: The Need to Focus on the Prosecution of the Higher Echelons of Organized Crime Networks" 2016 Afr J Leg Stud 221-234 [ Links ]

Nanima RD "The Drafting History of Uganda's Penal Code Act and Challenges to its Implementation" 2017 Stat LR 226-239 [ Links ]

O'Keefe R "Universal Jurisdiction: Clarifying the Basic Concept" 2004 JICJ 735-760 [ Links ]

Panov SM The Obligation aut Dedere aut Judicare ('Extradite or Prosecute') in International Law: Scope, Content, Sources and Applicability of the Obligation 'Extradite or Prosecute' (Doctoral dissertation University of Birmingham 2016) [ Links ]

Perrez FX Cooperative Sovereignty: From Independence to Interdependence in the Structure of International Environmental Law (Kluwer Law International The Hague 2000) [ Links ]

Podgor ES "Defensive Territoriality: A New Paradigm for the Prosecution of Extraterritorial Business Crimes" 2002 Ga.J Int'l & Comp L 1-30 [ Links ]

Roth BR "The Enduring Significance of State Sovereignty" 2004 Fla L Rev 1017-1050 [ Links ]

Seinfeld G "Reflections on Comity in the Law of American Federalism" 2015 Notre Dame L Rev 1309-1343 [ Links ]

Van Uhm DP "Organised Crime in the Wildlife Trade. Centre for Information and Research" 2012 CIROC Newsletter 2-4 [ Links ]

Watney M "A South African Perspective on Mutual Legal Assistance and Extradition in a Globalized World" 2012 PELJ 292-318 [ Links ]

Weil P "The Court Cannot Conclude Definitively ... Non Liquet Revisited" 1998 Colum J Transnat'l L 109-119 [ Links ]

Case law

Chitat Ng v Canada Communication No 469/1991

De Vries v The State 2012 1 SACR 186 (SCA)

Dewnath v S 2014 ZASCA 57 (17 April 2014)

Els v S 2017 2 SACR 622 (SCA)

Falk v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2012 1 SACR 265 (CC)

Harksen v President of the Republic of South Africa 2000 2 SA 825 (CC)

Hartford Fire Ins Co v California 509 US 764

Kruger v Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs 2016 1 All SA 565 (GP)

Mkhabela v S 2016 ZAGPPHC 936 (8 November 2016)

Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa 2001 3 SA 893 (CC)

Moti v President of the Republic of South Africa 2017 ZAGPPHC 501 (18 August 2017)

National Commissioner of the South African Police Service v Southern African Human Rights Litigation Centre 2015 1 SA 315 (CC)

President of the Republic of South Africa v Quagliani; President of the Republic of South Africa v Van Rooyen; Goodwin v Director-General, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development 2009 8 BCLR 785 (CC)

Prinsloo v S 2016 1 All SA 390 (SCA)

Prosecutor v Dusko Tadic (Appeal Judgement), IT-94-1-A (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia) (15 July 1999)

S v De Vries 2008 1 SACR 580 (C)

S v Kruger 1989 1 SA 785 (A)

S v Lemthongthai 2015 1 SACR 353 (SCA)

S v Meyer 2017 ZAGPJHC 286 (4 August 2017)

S v Mgedezi 1989 1 SA 687 (A)

S v Van Der Linde 2016 2 SACR 377 (GJ)

SS Lotus (France v Turkey) (1927) PCIJ Series A, No 10

Legislation

Conservation Law 16 of 2014

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Criminal Law Amendment Act 105 of 1997

Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007

Criminal Procedure Act 55 of 1977

Drugs and Drug Trafficking Act 140 of 1992

Extradition Act 67 of 2002

International Cooperation in Criminal Matters Act 75 of 1996

Lacey Act Amendments, 1981

Limpopo Environmental Management Act 7 of 2003

National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998

National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004

National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003

Nuclear Energy Act 32 of 1998

Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act 12 of 2004

Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons Act 7 of 2013