Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.21 n.1 Potchefstroom 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2018/v21i0a4220

CASE NOTES

Disposing of Bodies, Semantically: Notes on the Meaning of "Disposal" in S v Molefe

TR Carney*

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

In S v Molefe the presiding officer determines the meaning of the word "disposal" at the hand of two criteria, namely visibility and permanence; this means a body has to be permanently out of sight to be considered disposed of. He applies these two criteria in order to conclude if the accused is guilty of concealing the birth of her child by disposing of its body. In doing so, the court no longer interprets the word as an everyday word but turns it into a legal term. This note questions the linguistic soundness of the criteria by investigating how language structures space, and how these constructions relate to the word "disposal". In order to scrutinise the criteria, a text analysis was carried out by applying Talmy's ideas surrounding prepositions in structuring space and movement. Connected to this is the semantic difference between the words "seeing" and "looking": seeing is a sensory act, whereas looking is a cognitive one. In keeping with the contested word's status as a legal term, the difference between seeing and looking aids in formulating two new criteria. Courts may consider assessing whether disposal took place on the grounds of containment and movement; for instance, has the body been moved from one location to another and is the body being contained within another object like a bucket, a wooden box or a suitcase?

Keywords: Attempt; concealment of birth, disposal; dispose of; disposed; looking; ordinary meaning; seeing; space in language; uncompleted attempt.

1 Introduction

Where do people generally dump bodies, especially if they are trying to hide them from the authorities? If the most widely used corpus of English, the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA),1 is anything to go by, bodies are disposed of everywhere. When we study the collocates "dispose" and "body" (as lexemes)2 and pay attention to location, the 132 tokens offer the following possibilities: bodies of water (swamps, oceans, lakes), hefty or plastic bags, open spaces (fields, forests, the beach, vacant land and remote spots), trash cans, dumpsters, Styrofoam coolers, or they can be tossed somewhere "over the railing". Equally interesting is the fact that many bodies are wrapped in a blanket prior to disposal, at least in what we can tell from the COCA results. How is this different from a South African reality? Not much, apparently. When scrutinising a number of local cases, the bodies of the deceased are dealt with in a similar fashion. Bodies have been left in the bush,3 in a shallow grave,4 in a remote place,5 in an alley between houses,6 in an overturned vehicle,7 at sea,8 inside a manhole,9inside a lion enclosure,10 in small bottles and a bowl,11 and even covered with grass.12 The concealment of a baby's dead body in a bucket does not seem much out of place, then, as was the case in S v Molefé13(hereafter Molefe).

The use of corpora to aid in determining the ordinary meaning of words (and other legal-linguistic issues) is becoming commonplace.14 Consisting of more than 520 million words and containing texts that range from the written (fiction, news reports, academic contributions) to the spoken, which includes reports on South Africa, COCA does give some idea of the ordinary meanings reasonable English speakers assign to words.15 For the purpose of this contribution, one of the conclusions we can draw from the COCA results and examples taken from case law concerning the disposal of bodies, within the parameters of its ordinary meaning, is that a body does not need to be placed completely out of sight to be disposed of. Sometimes bodies are left in public spaces and are therefore easily found. We can also infer that the place of disposal can be of a temporary nature.

To dispose of something means that you want to get rid of it and that you want to free yourself of something, for instance a problem - like a dead body.16 The meaning of the word neither implies permanence nor does it prescribe location. If a body was dumped in an open veld, it was not necessarily the disposer's intention to place it out of sight permanently, but rather to simply rid him/herself of a problem. The word "dispose" furthermore alludes to the acts of hiding and concealing.

In 2012 the Molefe17case offered an alternative interpretation of the lexeme "dispose", based on opinions in R v Dema18 and R v Smith19, (hereafter Dema and Smith) which seem to form the legal principle for such cases. Amongst other problems, the law report questions when disposal is successfully executed. It offers two criteria, namely a measure of permanence and visibility.20 In other words, a body is effectively disposed of when it lies in its intended place and is completely out of sight, rather than being there "for all to see".21 Snyman22 confirms this when he states that when people can find the body again, it has not been duly disposed of. These criteria do not wholly correspond with the ordinary meaning suggested above, and phrases like "intended place", "not for all to see" and "when people can find the body again" are vague; as a result, they may create more problems than they solve. For instance, does the permanence of a resting place apply only to officially recognised interment sites and locations used by criminals with the sole intention that the body never be found? It occurs often enough that innocent parties happen upon a body, either shortly after or years after it was dumped. Once the body has been discovered, is its status of disposal then revoked because someone found it?

Pittman JP is quite adamant in Dema that to place a body "on the floor or on a table or bed"23 does not constitute disposal, because anyone entering that room can see it. Yet in the case brought before Pittman JP the child's corpse had been placed inside a wooden box that had a lid on it. If it were not for the blood trail leading to the box, the accused's roommate would most likely not have known about the body's whereabouts, and this could have given the accused enough time to dispose of it somewhere else in a more permanent location. When looking at this from a linguistic perspective, it is important to pay attention to the prepositions used in describing locations and actions. Pittman JP refers to the body "on" the floor, "on" the table, "on" the bed, whereas the body was "in" the box. In Smith, the body was "in" the suitcase and the same applies to Molefe; the body was "in" the bucket. The prepositions "on" and "in" tell us something about the spaces involved, and how speakers perceive and interpret them.24 These scenarios invoke two different verbs, such as seeing and looking. We see an object that lies on top of a surface and we look at what is inside a container. The language involved reveals something more than what can simply be seen or found.

This brings me to the purpose of the present contribution, which is first to consider the court's given criteria, and second to determine whether a linguistic perspective can shed new light on the meaning of the lexeme "dispose" within its context. Lastly, the aim is to consider other possible criteria in service of the interpretation of the contested word's meaning. As a legal-linguistic (and specifically a forensic-semantic) issue is at the heart of this note, I will limit myself to the identified language aspects of the case and not endeavour to criticise the court's overall decision or the legal principles underlying the judgement. Readers should rather see this contribution as a linguistic thought experiment which aims to expand on the existing interpretation of the disposal and concealment of a body as a statutory offence.

The note is divided into the following sections: at first, the facts of the case relevant to this discussion are provided. This is followed by a consideration of what the word "attempt" means. Thereafter, I look at Talmy's ideas on how language structures space, and their consequence for the court's given criteria. The last part of this contribution focuses on the lexeme "dispose" as a legal term, and the new criteria that may improve its current definition.

1 employ a text analytical methodology to come to my conclusions.

2 Facts of the case

The accused, an adult female, gave birth prematurely, resulting in the baby's being born dead. She was subsequently convicted in the Bloemhof district on a charge of contravening section 113(2) and (3) of the General Law Amendment Act 46 of 1935, which prohibits the unlawful concealment of the birth of a child and the (attempted) disposal of its body. The accused voluntarily pleaded guilty of lying to the nurse about the dead child and confessed her intention to attempt to dispose of its body. She had been confronted by police and forced to show them where the body was kept, and had therefore not been able to affect her plan. The body had been kept in a bucket at the accused's house. Though the accused was found guilty by the Bloemhof Magistrate's Court, the case was sent for special review due to the fact that the Director of Public Prosecutions had given verbal permission to prosecute instead of written notification. On review, Rabie J addressed not only the issue of verbal/written permission, but also attended to the question whether a stillborn baby qualifies as a child and whether the accused actually disposed of or attempted to dispose of its body, based on the criteria of permanence and visibility. The conviction was set aside.

3 An issue of attempt

Though the presiding officer never defines the word "attempt", he clearly distinguishes between the disposal of a body and an attempted disposal. According to Rabie J, neither a disposal nor an attempted disposal took place.25 If neither activity took place, the implication is that the accused did nothing. Yet the baby had not crawled into the bucket by itself. The body's location implies that it was placed there by someone, in this case the accused. This furthermore implies that steps were followed as part of an initial attempt to dispose of the body.

The word "attempt" means that a person tries to reach a certain goal. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as "a putting forth of effort to accomplish what is uncertain or difficult"; the word is also contrasted with "the attainment of its object".26 The word furthermore entails that the attempter has either not done this specific deed before or that he or she had not succeeded during the previous challenge. Once the attempter reaches the intended goal, the act is no longer known/seen as an attempt, but as a completed task. This is obvious when studying the applicable antonym: "success". It may happen that a person has to try more than once to complete a task. Each try qualifies as an attempt. Placing the baby in the bucket in order to get rid of it elsewhere later on qualifies as the start of an intended process. The fact that the final act of disposal was not successfully completed does not mean that no attempt was made. Instead, we can refer to it as a failed attempt.

From a legal point of view, both Burchell27 and Snyman28 distinguish between completed and uncompleted attempts.29 Using the words of Watermeyer CJ in S v Schoombie,30Burchell31 defines "attempt" as follows:

a) the wrongdoer has done everything he or she has set out to do in order to commit a crime, but has failed due to a lack of skill or foresight, or the presence of an unforeseen obstacle;

b) the wrongdoer has not been able to do everything he or she has set out to do, because the completion of the crime has been prevented by the intervention of some external agency.

In the event of an uncompleted attempt, a court has to gauge to what extent an accused's acts amount to or fall short of an attempt.32 As such, the question of proximity arises. How close to successful completion does the attempt lie? Burchell33 goes on to state that an accused will be accountable for an attempt "as soon as he or she does an act in furtherance of that intention, no matter how remote the act may be from the completion of the crime". Snyman34 argues that a person is guilty of an attempt once it becomes clear that he or she - through commissions or omissions - has at least started executing the intended crime. However, Burchell's35 opinion differs from Snyman's in the sense that an attempt should have made some considerable progress before it can attract liability; in other words, it should amount to more than just the start of a process. Both scholars share the view that an attempt is more than just preparation.36

From my perspective, the attempt in Molefe falls within the uncompleted category: an intended crime that is interrupted or prevented before the act could be completed.37 The accused placed the baby's corpse in the bucket temporarily, with the intent of disposing of it permanently. Due to the early intervention of the police she could not go ahead with her plans. The situation in Smith is similar: the accused placed the body in a suitcase and then proceeded to hide the suitcase in another room until she was able to remove it from the premises. The defence used the words "temporary disposal".38

Let us play devil's advocate for one second: if the argument so far does not suffice and we accept that the body's placement in the bucket does not qualify as either disposal or an attempted disposal, then how should we describe the situation? If it is not an attempt to conceal the body, should we then describe it as a suspended condition? Or should we simply describe the situation by reverting to the statement that the baby's body is in a bucket? The fact that the accused put the baby's body in the bucket, either to conceal it or for easy transport to an intended location, means that a process was set in motion. As such, an attempted disposal commenced.

4 How language structures space, according to Talmy39

In Talmy's conceptual approach to language systems, a distinction should be made between two levels. The first and broadest level uses lexical items, sentences, paragraphs and larger chunks of discourse to convey conceptual content, which may include feelings, ideas and practical information.40 The second level consists of closed-class words, which are also known as grammatical or function words.41 Called closed-class forms because no new meanings or functions can be added to their existing meaning or function, these words include pronouns, conjunctions, articles and prepositions. The pronoun "he" can refer only to a male in the third person singular, unlike the word "apple", which evokes a variety of senses. Function words like prepositions can provide us with a great deal of additional information. For instance, when scrutinising a sentence such as that in 4.1 below, we pay close attention to the prepositions and what they tell us about space and motion.

4.1 The pecan nut tree is next to the house

We know that the preposition "next to" tells us something about space, volume, mass and location.42 The tree is the smaller object; as a result, its location is described in terms of the larger object, the house.43 We can furthermore infer distance and consequently know that the tree is near the house, but not inside it. Likewise, "next to" means that the tree is positioned to the left or right of the house, otherwise we would have said that the tree is in front of, behind or opposite the house. The tree's location with respect to the position of the house similarly tells us something about the boundaries of the objects; their geometry.44 If we were to interchange the two objects (the house is next to the pecan nut tree), we are not simply left with two objects that relate to space; rather, we are confronted with a semantic difference. If the house is described in relation to the tree, the implication is that the tree is older and better known than the house. The pecan nut tree then becomes a very specific point of reference.45

When we consider the preposition in combination with the verb, we realise that the objects are stationary; no movement is present. One object is not transpositioned from one location to another.46 By contrast, the following sentence illustrates motion.

4.2 James backs the car out of the garage

In sentence 4.2, aspects such as space, volume and location are still present and relevant, but now there is also a conceptual path which indicates motion.47 One object is now transpositioned from one location to another. We know the car that used to be inside is now in the process of moving out and backwards. The preposition gives us a sense of direction. Moreover, the main object (the car) is no longer in a state of being contained; its location and its relation to the garage are changing. The fact that the car is in the process of occupying a new space confirms that an ongoing event is taking place.

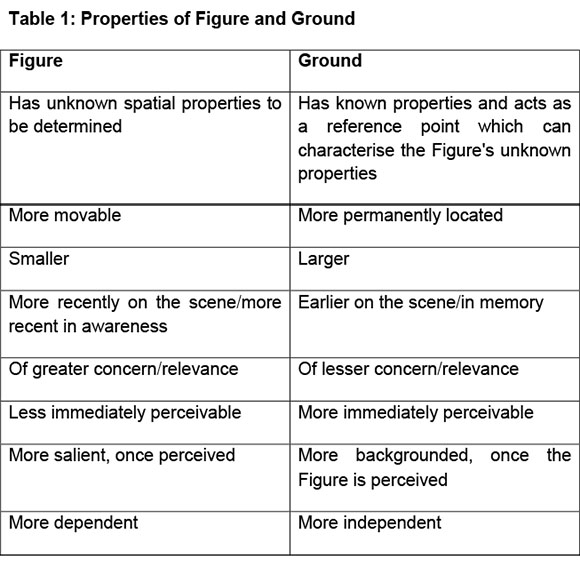

Talmy48 uses Gestalt theory in referring to the primary object as "Figure" and the secondary object as "Ground". He describes Figure as a "moving or conceptually movable entity" whose site or path is the variable value, whereas Ground is seen as the reference entity, which mostly has a "stationary setting" with respect to the Figure's site or path.49 In sentence 4.2, the car qualifies as Figure and the garage as Ground. Some of their properties are summarised in Table 1.50

As the Ground, the garage in sentence 4.2 is the larger and more permanently located object. A garage is conventionally built before the owner's car is bought and is the first of the two objects to be seen, due to its size and the fact that the car was parked inside. As cars come and go, the garage forms part of an earlier memory. Because the event revolves around the car (the Figure), the garage is of lesser concern and moves to the background once the car is perceived. However, the car's location is determined in relation to that of the garage, which makes the garage more independent. It furthermore consists of known properties (height, width, length; it has four walls and a roof; it has a large, retractable door) which in turn might assist in learning the properties of the car (its height, width, length, etc.).

When applied to the case at hand, the baby's corpse qualifies as the Figure and the bucket as the Ground. The body is smaller than the bucket and its spatial properties are determined in relation to those of the bucket. Though both objects are moveable, the bucket is less moveable with the body in it; Hence the accused's risk of being caught. In this scenario the body is moved into the bucket (provisionally). The body is also more recently on the scene and of greater concern than the bucket. More importantly, the body is less immediately perceivable due to its location in the bucket, making the bucket the first thing we see before observing the body. Once the body is perceived, it becomes more salient than the bucket. The body's whereabouts are dependent on the bucket, whereas the bucket's location and geometry are not dependent on the baby in it.

When applying the properties of Figure and Ground to this case, we not only learn something about the geometry of the baby's body but also something about space, movement and time. We can illustrate this through the three sentences below. In the first two sentences the body's location is stationary, but in the third sentence movement is implied. This furthermore implies that the bucket (and by extension the accused's house) was the body's first location of disposal at that point in time - albeit temporarily.51 Here the prepositions aid in determining the object's immediate environment.

4.3 The body is in/inside a bucket at my house.

4.4 The body is in/inside a bucket at my house [before I can bury it in the back yard].

4.5 The body is in/inside an unmarked grave in the veld [after I kept it in a bucket for two days].

Both of the prepositions "in" and "inside" indicate an enclosure.52 If you say that something is in a box or a bucket, you are recalling its geometry, specifically its interior.53 If an object is located/positioned within another container (object X is to be found in the interior of the container), there is no longer an act of seeing but an act of looking, of finding. If, however, object X is lying somewhere on the surface, which would be indicated by prepositions such as "on top of", "next to", "across from", or "in front of", then the act of seeing would be more suitable and looking would be reserved for closer inspection. When object X is to be found inside another object such as a container, X is not there for all to see. In order to observe the contents of the bucket, the police had to look inside the bucket; the contents had to be shown to them. In other words, there is a semantic difference between "seeing" and "looking". Seeing is a sensory act, whereas looking is a cognitive one. It is therefore not just a straightforward issue of the object's visibility. When a person has to actively look at/for something, the object is hidden from plain sight. Considering that the accused intended to dispose of the body and that the body's location was not on top of a surface rendering it easily visible, the act of concealment should be obvious.54 The body was hidden and not clearly visible. If the accused had not intended or attempted to hide the baby's corpse, there would have been no reason to place it inside a container. She could then have placed it on any given surface like her bed or a table "for all to see".

1) a POINTs BEloc AT a POINTs, FOR an bEXTENTt.

2) a POINTs BEloc AT a POINTs that IS OF the INSIDE OF [AN ENCLOSURE].

5 New criteria for the interpretation of "disposal"

It is common practice within many legal systems to interpret words according to their ordinary meaning, when those words are not defined by the legislator.55 Admittedly, as with "reasonable person", the concept of ordinary meaning remains elusive and problematic.56 As Hutton57 points out, what is ordinary to one person is not necessarily ordinary to the next. Nevertheless, ordinary meaning is often seen as the popular, straightforward meaning of words, or (regrettably) their dictionary meaning.58 We understand ordinary meaning as being the opposite of technical, jargon-filled and scientifically precise language. Slocum59describes ordinary meaning as texts having to be "understood by different people in the same way"; this must include the general public as well as legal practitioners. Ordinary meaning furthermore places a limitation on a court's ability to interpret words, especially if they come across as clear and unambiguous.60 Unless a legal term exists or the definition of a word does not fit the context, a court may not veer from a word's ordinary meaning.61

Though it falls within a court's authority and responsibility to decide which words are ordinary words and which are terms of art,62 and also to extend/broaden a word's meaning to give better effect to a relevant statute,63 the technical term should always be a trustworthy preference. The chosen criteria by which a word's meaning is extended or newly defined should therefore be clear and watertight.

By introducing the two criteria for interpreting "disposal", Pittman JP turned the contested word into a technical legal term, which he probably did in favour of the accused. In doing this, a court no longer understands "disposal" within the boundaries of its ordinary meaning, as can be seen by Rabie J's application of the same criteria. As has been suggested earlier, the court's two criteria for disposal are linguistically vague, rendering them problematic. When faced with criteria that come across as forced and linguistically unsound, what would be a better solution? The two options would be either to revert to the word's ordinary meaning (the ideal option) or to retain its status as legal term, but with new criteria.

As mentioned before, the criteria put forward by Rabie J are those suggested by Pittman JP. In contrast to Rabie and Pittman's view, Searle J considered the accused's actions in Smith as a "secret disposing of the dead body"64 and did not base his decision on a specific set of criteria; rather he used the facts of the case to determine if disposal took place. The suitcase in which the body was concealed and was later transported to different locations sufficed as a place of disposal. The fact that the secret was revealed that same evening did not revoke the status of disposal. There is no mention of permanence or visibility. The temporality of the concealment does not raise questions of attempt or disposal and, as with the box in Dema and the bucket in Molefe, anyone would have been able to open the suitcase and see its content if they so wished.

What could be alternative criteria for the lexeme "disposal" with regard to the context of intentional concealment? In keeping with what we already know of its ordinary meaning, I offer these two (rather simple) criteria, namely containment and movement. They can be illustrated in the following questions:

a) Can we easily (that is, immediately or without much effort) see the body?

b) Was the body placed in a location other than that in which the person died?

Both these questions are closed-ended. If we answer "yes" to the first and "no" to the second question, then the body was not disposed of. The reverse is true for bodies that were disposed of.

The first criterion brings us back to the difference between the verbs "see" and "look". If it is a matter of searching for something, then the object is no longer in plain sight. Once the preposition in/inside becomes relevant, we are dealing with the concealment of (or attempt to conceal) a crime.65 Also, we can then describe the dead body in terms of its place of disposal, its containment or Figure and Ground relations.

The second criterion, which is directly connected to the first, may describe a conceptual path. If a woman gave birth to a stillborn baby at her house, on her bed, and left the baby right there, the location remains static; no concealment is present. However, if she panicked and placed its body under her bed, inside her closet, behind her TV console, or in a shallow grave -even if only temporarily - to conceal what had just happened to her, the body has been transported from one location to the next. In order to conceal the event the object's location is no longer kept static.

My criteria correspond with the presiding officers' initial understanding that if a body is there for all to see it has not been disposed of. The difference between our interpretations lies with the movement and containment of the body, regardless of the duration of time. A court has to consider both criteria. For instance, if a person wants to conceal a dead body, the person will not remove it from one surface, like a bed or a table, and place it on top of a similar surface close by. This would be odd. In such a case movement might have taken place, but with no to little effect. We can still easily see the body, which means that containment has not taken place.

What if a body were placed inside a container that is either transparent or very shallow? What if a body were deliberately dumped in a larger space such as a forest, in the bushveld or on a beach? Concerning the first question, containment is determined by seeing versus looking. If the content of a container is easily visible, then containment is not present. Regarding the second question, we are once more led by the semantics of the prepositions involved. We do not walk "on" the field or swim "on" the lake or hike "on" the forest. A person goes hiking "in" a forest; he or she is contained by it. A forest is something you enter. A body in a veld, a forest or a lake is usually visible only to those who happen upon it or search for it. It is placed in these locations because it will not be easily seen or found. In fact, when the police suspect that a body might be in a field or forest, they use search parties and detection dogs to help them find it. The same cannot be said for a body that was left on a beach or in a clearing. A beach is something you walk or sit "on", which renders it easily visible, at least more so than would be the case with a dead body in a forest. A beach or a cleared piece of land should rather be seen as a surface, which does not contain. However, if a person did not die on the beach, but his or her body was taken there, then movement in service of concealment of the crime was clearly present.

6 Conclusion

Language is the legal profession's most important vehicle; unfortunately, it is not always its friend. Because the meaning of words is infamously ambiguous, indefinable and often troublesome, it is probably better to keep things as simple as possible. Section 113(2) of the General Law Amendment Act defines neither "dispose" nor "concealment", but it offers "lawful burial order" as a contextual antonym of the two words mentioned here above. From this we can infer that if someone does away with a body in a manner that does not qualify as a legal burial, the action most probably meets the requirements of disposal.

From a linguistic perspective, based on the contextual meaning of "disposal", the accused did try to conceal the birth of her child by disposing of its body. The bucket became the first instance of disposal. She removed the body from where it was stillborn and deliberately placed it inside a bucket to hide it from wandering eyes. She disposed of its body temporarily with the intention of getting rid of it somewhere else. In the Smith case, the court found the accused guilty with a strong recommendation for mercy, indicating that the court had sympathy for what had happened to the accused. We get the impression that the presiding officers in Dema and Molefe wanted to be equally merciful by indicating that the accused had not transgressed any law. However, the accused in Dema and Molefe did break the law. Assigning the two criteria to the word "disposal" may have been a somewhat clumsy and excessive way of being lenient. Linguistically, it makes more sense to study words conceptually and within their context than to add to their meaning, especially when their conventional meaning can do the work equally well.

Bibliography

Literature

Blackwell S "Why Forensic Linguistics Needs Corpus Linguistics" 2009 Comparative Legilinguistics 5-19 [ Links ]

Burchell J Principles of Criminal Law 4th ed (Juta Claremont 2013) [ Links ]

Carney TR and Bergh L '"n Taalkundige Perspektief op Woordeboekgebruik in die Hof: Die Woordeboek as Toevlugsoord" 2014 LitNet Akademies (Regte) 23-64 [ Links ]

Cotterill J "How to Use Corpus Linguistics in Forensic Linguistics" in O'Keeffe A and McCarthy M (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics (Routledge New York 2012) 578-590 [ Links ]

Cowen DV "The Interpretation of Statutes and the Concept of 'the Intention of the Legislature'" 1980 THRHR 374-399 [ Links ]

Devenish GE Interpretation of Statutes (Butterworths Durban 1996) [ Links ]

Dictionary Unit for South African English The South African Concise Oxford Dictionary (Oxford University Press Cape Town 2007) [ Links ]

Du Plessis L Re-interpretation of Statutes (Butterworths Durban 2002) [ Links ]

Feist MI "Inside In and On: Typological and Psycholinguistic Perspectives" in Evans V and Chilton P (eds) Language, Cognition and Space: The State of the Art and New Directions (Equinox London 2010) 95-114 [ Links ]

Hutton C Word Meaning and Legal Interpretation (Palgrave Macmillan London 2014) [ Links ]

Labuschagne JMT "Die Woord as Kommunikasiebasis in die Wetgewingsproses" 1988 SAPR 34-45 [ Links ]

Labuschagne JMT "Regsnormvorming: Riglyn vir 'n Nuwe Benadering tot die Tradisionele Reëls van Wetuitleg" 1989 SAPR 205-212 [ Links ]

Labuschagne JMT "Gewone Betekenis van 'n Woord, Woordeboeke en die Organiese Aard van Wetsuitleg" 1998 SAPR 145-148 [ Links ]

Mouritsen SC "The Dictionary is not a Fortress: Definitional Fallacies and a Corpus-based Approach to Plain Meaning" 2010 BYULR 1915-1980 [ Links ]

Mouritsen SC "Hard Cases and Hard Data: Assessing Corpus Linguistics as an Empirical Path to Plain Meaning" 2011 CSTLR 156-205 [ Links ]

Odendal FF and Gouws RH Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (Pearson Kaapstad 2010) [ Links ]

Slocum B Ordinary Meaning: A Theory of the Most Fundamental Principle of Legal Interpretation (Chicago University Press Chicago 2016) [ Links ]

Snyman CR Strafreg 4th ed (Butterworths Durban 1999) [ Links ]

Solan L "Can Corpus Linguistics Help Make Originalism Scientific?" 2016 YLJF 57-64 [ Links ]

Solan LM and Gales T "Finding Ordinary Meaning in Law: The Judge, the Dictionary or the Corpus?" 2016 IJLD 253-276 [ Links ]

Talmy L "How Language Structures Space" in Pick H and Acredolo L (eds) Spatial Orientation: Theory, Research and Application (Plenum Press New York 1983) 225-282 [ Links ]

Talmy L Towards a Cognitive Semantics. Volume 1: Concept Structuring Systems (MIT Press Cambridge, Mass 2000) [ Links ]

Vandeloise "Are there Spatial Prepositions?" in Hickman M and Robert S (eds) Space in Language: Linguistic Systems and Cognitive Categories (John Benjamins Amsterdam 2006) 139-154 [ Links ]

Woolls D "Better Tools for the Trade and How to Use Them" 2003 Forensic Linguistics 102-112 [ Links ]

Case law

South Africa

R v Dema 1941 1 SA 599 (E)

R v Smith 1918 CPD 260

S v Cele 1991 1 SACR 621 (A)

S v Kleynhans 1994 1 SACR 195 (O)

S v M 1998 1 SACR 41 (O)

S v Mamba 1990 1 SACR 211 (A)

S v Mofokeng 1992 2 SACR 110 (A)

S v Molefe 2012 2 SACR 514 (GNP) S v Mooi 1990 1 SACR 592 (A)

S v Nair 1993 1 SACR 451 (A)

S v Roberts 2000 2 SACR 522 (SCA)

S v Schoombie 1945 AD 541

S v Scott-Crossley 2008 1 SACR 223 (SCA)

S v Shabalala 1991 2 SACR 478 (A)

S v Terblanche 2011 1 SACR 77 (ECG)

Venter v R 1907 TS 1910

United States of America

People v Harris (72 Ill 2nd 16377 NE 2nd 28, 1978 Ill 17 Ill Dec 838) State v Rasabout (2015 UT 72, 356 P 3rd 1258)

United States v Costello (666 F 3rd 1040 (2012))

Legislation

General Law Amendment Act 46 of 1935 Interpretation Act 33 of 1957

Internet sources

Brigham Young University 2017 Disposal https://corpus.byu.edu/coca/ accessed 8 September 2017 [ Links ]

Lee T and Mouritsen S 2017 The Path Forward for Law and Corpus Linguistics https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/08/11/the-path-forward-for-law-and-corpus-linguistics/?tid=ss_mail& utm_term=.e4f45b62d59f accessed 8 January 2018 [ Links ]

Oxford University Press 2017 Attempt http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/12765?rskey=B8ZBhz&result=1#eid accessed 25 October 2017 [ Links ]

Vogel F, Hamann H and Gauer I "Computer-assisted Legal Linguistics: Corpus Analysis as a New Tool for Legal Studies" 2017 L&SI https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/lsi.12305 accessed 1 May 2018 [ Links ]

List of Abbreviations

BYULR Brigham Young University Law Review

COCA Corpus of Contemporary American English

CSTLR Columbia Science and Technology Law Review

IJLD International Journal of Legal Discourse

L&SI Law and Social Inquiry

SAPR Suid-Afrikaanse Publiekreg

THRHR Tydskrif vir Hedendaagse Romeins-Hollandse Reg

YLJF Yale Law Journal Forum

Date of submission: 15 January 2018

Date published: 17 May 2018

Editor Prof C Rautenbach

* Terrence R Carney. BA (Hons) MA (UP) PhD (UFS). Senior lecturer, Department of Afrikaans and Theory of Literature, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa. E-mail: carnetr@unisa.ac.za.

1 Brigham Young University 2017 https://corpus.byu.edu/coca/.

2 A lexeme is a single word that can take different morphological forms, for instance the word "run" takes the forms "runs", "ran" and "running". The word "disposal" is dealt with in the same way and includes the forms "dispose", "disposed", "disposing" and "disposable".

3 S v Mooi 1990 1 SACR 592 (A) 593; S v Mamba 1990 1 SACR 277 (A) 229.

4 S v Cele 1991 1 SACR 627 (A) 628; S v Roberts 2000 2 SACR 522 (SCA) 522.

5 S v Kleynhans 1994 1 SACR 195 (O) 195.

6 S v Terblanche 2011 1 SACR 77 (ECG) para D.

7 S v Mofokeng 1992 2 SACR 710 (A) paras F and G.

8 S v Nair 1993 1 SACR 451 (A) 451.

9 S v Roberts 2000 2 SACR 522 (SCA) 522.

10 S v Scott-Crossley 2008 1 SACR 223 (SCA) para F.

11 S v Shabalala 1991 2 SACR 478 (A) 478.

12 S v M 1998 1 SACR 47 (O) 49.

13 S v Molefe 2012 2 SACR 574 (GNP) paras 2 and 6.

14 Woolls 2003 Forensic Linguistics 102-112; Blackwell 2009 Comparative Legilinguistics 5-19; Mouritsen 2010 BYULR 1915-1980; Mouritsen 2011 CSTLR 156-205; Cotterill "How to Use Corpus Linguistics" 578-590; Solan 2016 YLJF 5764; Solan and Gales 2016 IJLD 253-276; Vogel, Hamann and Gauer 2017 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/lsi.12305. This is not restricted to literature, but can be seen in a few cases too. The following state and federal cases in the United States have either made use of typical corpus linguistic techniques or they have explicitly referred to corpus linguistics as a method of interpreting ordinary meaning: State v Rasabout (2015 UT 12, 356 P 3rd 1258), People v Harris (12 Ill 2nd 16311 NE 2nd 28, 1918 Ill 11 Ill Dec 838) and United States v Costello (666 F 3rd 1040 (2012)). See furthermore Lee and Mouritsen 2011 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2011/08/11/the-path-forward-for-law-and-corpus-linguistics/?tid=ss_mail&utm_term=.e4f45b62d59f.

15 Granted, of course, a South African corpus of English would be better suited for South African language queries. Such corpora are currently not publicly accessible.

16 See the definitions for "dispose of" in Dictionary Unit for SAE 2001 South African Concise Oxford Dictionary 335 and "ontslae raak" in Odendal and Gouws Handwoordeboek 801.

17 S v Molefe 2012 (2) SACR 514 (GNP) (hereafter Molefe).

18 R v Dema 1941 1 SA 599 (E) (hereafter Dema).

19 R v Smith 1918 CPD 260 (hereafter Smith).

20 Molefe para 1.

21 Molefe para 7.

22 Snyman Strafreg 432.

23 Dema para 4.

24 The preposition "in" is often described in terms of containment and inclusion, whereas "on" is about surface contact between two objects; see Feist 2010 "Inside In and On" 95-114.

25 Molefe paras 8 and 9.

26 Oxford University Press 2017 http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/12765?rskey=B8ZBhz&result=1#eid.

27 Burchell Principles of Criminal Law 535.

28 Snyman Strafreg 283.

29 Snyman actually identifies three instances, which include the "impossible attempt". This happens when X has the intent but not the means to execute his or her plans.

30 S v Schoombie 1945 AD 541 545-546.

31 Burchell Principles of Criminal Law 535.

32 Burchell Principles of Criminal Law 538.

33 Burchell Principles of Criminal Law 538.

34 Snyman Strafreg 283.

35 Burchell Principles of Criminal Law 538.

36 Burchell Principles of Criminal Law 61; Snyman Strafreg 283.

37 Snyman Strafreg 283.

38 Smith 260.

39 Talmy Toward a Cognitive Semantics.

40 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 178.

41 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 178.

42 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 180.

43 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 182.

44 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 182. Also see Vandeloise 2006 "Are There Spacial Prepositions?" 141.

45 See Vandeloise "Are there Spatial Prepositions?" 142. He states that prepositions such as these have the function of localising a target by referring to the landmark. What he means by this is that one determines and describes the target object's location by using the larger landmark/point of reference. We can say "John is waiting behind the church" where the church is the point of reference; however we cannot really say "The church is situated behind John's poodle, Jessica"; it would be odd to use a dog as a type of landmark, unless there is a well-known statue of Jessica.

46 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 180-181.

47 See Vandeloise "Are there Spatial Prepositions?" 142.

48 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 184.

49 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 184.

50 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 183.

51 We can use the following motion-aspect formulas in Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 215, 245-246 to calculate and confirm the stationary nature and location of the body. The relevant formulas for that case look like this:

52 Talmy Towards a Cognitive Semantics 194.

53 Talmy "How Language Structures Space" 246. The use of prepositions is not restricted to geometry, of course. They are connected to an object's functional attributes too; in the instance of a bucket, the usage extends to holding, constraining, collecting and carrying; see Feist 2010 "Inside In and On" 97, 102, 104, and Vandeloise "Are there Spatial Prepositions?" 140, 143. The prepositions will change when the object is used for something other than its prototypical function. For example, when someone utilises a bucket as a stepladder, the preposition will change from "in" to "on".

54 Bear in mind a bucket's function as a carrying vessel. In Smith, the suitcase is considered a place of disposal, partly because it was used as a transportation device. See Snyman Strafreg 432, fn 230.

55 Hutton Word Meaning 26-21.

56 Hutton Word Meaning 44.

57 Hutton Word Meaning 56. He goes on to describe ordinary meaning as a legal fiction; also see Du Plessis Re-interpretation of Statutes 199. Similar arguments have been made by Labuschagne 1988 SAPR 34; Labuschagne 1989 SAPR 208; Labuschagne 1998 SAPR 146; Cowen 1980 THRHR 386 and Devenish Interpretation of Statutes 26.

58 Du Plessis Re-interpretation of Statutes 199. See furthermore the contribution by Carney and Bergh 2014 LitNet Akademies on the misapprehension that ordinary meaning is equal to a dictionary definition.

59 Slocum Ordinary Meaning 3.

60 Carney and Bergh 2014 LitNet Akademies 31.

61 Hutton Word Meaning 41; Devenish Interpretation of Statutes 242. This is also known as the golden rule, which became cemented in South African case law by means of Venter v R 1901 TS 1910.

62 I agree with Hutton Word Meaning 41-42, that the boundary between ordinary and legal meaning remains problematic, making clear distinctions difficult.

63 Article 1 of the Interpretation Act 33 of 1957; also see Devenish Interpretation of Statutes 241.

64 Smith 260.

65 Of course, this does not apply to situations where someone died inside a container by accident, unless the murderer chose the container as both the place of death and that of concealment.