Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.20 n.1 Potchefstroom 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2017/v20n0a735

ARTICLES

Regulating Against Business "Fronting" to Advance Black Economic Empowerment in Zimbabwe: Lessons from South Africa

Tapiwa V WarikandwaI, *; Patrick C OsodeII, **

IUniversity of Fort Hare South Africa. Email: TWarikandwa@ufh.ac.za

IIUniversity of Fort Hare South Africa. Email: POsode@ufh.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article examines Zimbabwe's indigenisation legislation, points out some of its inadequacies and draws lessons from South Africa's experiences in implementing its own indigenisation legislation. Both countries have encountered challenges relating to an upsurge in unethical business conduct aimed at defeating the objectives of their black economic empowerment programmes, policies and legislation. This practice is called business fronting. However, while South Africa has succeeded in enacting a credible piece of legislation aimed at addressing this issue, Zimbabwe has yet to do so. The article points out that the failure to specifically regulate against business fronting poses the most significant threat to the attainment of the laudable aims and objectives of the indigenisation programme and related legislation. In order to avoid becoming a regulatory regime that is notorious not only for being functionally ineffective but also for tacitly permitting racketeering in reality, the article argues for the adoption of anti-fronting legislation in Zimbabwe using the South African legislation as a model.

Keywords: Black economic empowerment; indigenisation; business fronting; Zimbabwe; South Africa; distributive justice.

1 Introduction

Black economic empowerment programmes in Zimbabwe and South Africa have often seen the indigenous people who were previously and who remain largely excluded from the economic mainstream going into a state of euphoria1 based on the genuine belief that such programmes are an effective panacea2 for their existential socio-economic challenges.3 This belief appears to be affirmed by the values set out in the African Charter on Human and People's Rights,4which recognise and advance the right to the free disposition of wealth and natural resources in the best interests of indigenous peoples.5 It is thus not surprising to see that indigenisation in Zimbabwe is founded on a socio-political creed that land and mineral resources exist in the country's territory to a greater extent6 for the benefit of indigenous people7 and to a lesser extent for multinational corporations.8The term multinational corporation, for the purposes of the implementation of indigenous economic empowerment laws, is often controversially understood to refer to western-owned companies and not Asian-owned companies.9 The need to remedy colonial injustices and significantly improve the extent of the participation of indigenous Zimbabweans in the country's economic activities is often advanced as the primary justification for indigenisation programmes which seek to economically empower previously disadvantaged Zimbabweans.10 Premised on the need to redistribute the country's economic resources in a manner that favours indigenous Zimbabweans,11 Magure points out that the indigenisation programme has promised much to the anxious and highly expectant majority but delivered little.12 Instead, many of the benefits from the indigenisation programme have gone to a few well-connected elites13 due largely to unethical business practices such as business fronting.14Accordingly, in order to ensure that each and every indigenous Zimbabwean benefits from the indigenisation of land as well as other economic resources and is enabled to enter the economic mainstream, the IEEA urgently requires strengthening through the inclusion of specific anti-fronting clauses or alternatively the enactment of an independent anti-fronting legislation.15It is therefore not surprising that at the time of writing this article, the Public Sector Corporate Governance Bill had been tabled before parliament with a view to introducing a law which addresses corruption and other related maladministration challenges in the public and private sectors.16Specifically, the law will seek to address any murky business activities in both the private and public sectors and ensure that such practices are punishable at law.17 This in itself is sufficient evidence of the Zimbabwean Government's acknowledgement of the inadequacies of the existing laws in fighting corruption and other irregular business activities, including business fronting.

This article argues that presently, because of the omission to provide for the problem of fronting, Zimbabwe has inadequate black economic empowerment legislation which has created a reality in which the benefits of the legislation's implementation appear to accrue largely to the well-connected, politically favoured elites and their associates.18 The article is divided into six parts. The first part introduces the concept of indigenisation in Zimbabwe, while the second presents a brief description of the country's indigenisation regulatory framework. The third part undertakes an analysis of incidents of business fronting in Zimbabwe and shows why it is easy to front. The fourth part examines the regulation of business fronting in South Africa, while the fifth part draws lessons for Zimbabwe from South Africa's amendment of its black economic empowerment legislation in order to effectively address the challenge of fronting. The last part of the article offers recommendations on how best to strengthen Zimbabwe's indigenisation laws in preventing fronting.

2 Zimbabwean indigenisation law

Indigenisation policies and processes in Zimbabwe are regulated by the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act (IEEA).19 The IEEA provides the policy definition of empowerment as:

The creation of an environment which enhances the performance of ... economic activities of indigenous Zimbabweans into which they would have been introduced or involved through indigenisation.20

Emphasis in the definition is clearly on the compelling need to ensure that the benefits of the indigenisation policy cascade down to indigenous Zimbabweans in their multitudes and not just to a few politically connected elites and their foreign business partners, which may be the current state of affairs.21 It is submitted that the need to maximise the reach or dispersal of those benefits is the reason why section 2(1)22 of the IEEA further defines indigenisation as:

... a deliberate involvement of indigenous Zimbabweans in the economic activities of the country, to which hitherto they had no access, so as to ensure the equitable ownership of the nation's resources.23

The indigenisation policy of Zimbabwe, the IEEA, as well as the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Regulations seek to achieve the following objectives:

a) transforming indigenous Zimbabweans from being mere suppliers of labour and consumers to participants in the country's economy as owners of businesses;24

b) transferring equity shareholding in all businesses with a net asset value of United States Dollars (USD) 500 000 and above to indigenous Zimbabweans;25

c) promoting the procurement of at least 51% of goods and services needed by all government departments, statutory bodies and local authorities from businesses controlled by indigenous Zimbabweans;26

d) establishing a National Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Board (NIEEB) to advise the Minister and manage the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Fund;27

e) establishing an Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Fund to provide assistance to indigenous Zimbabweans for the purposes of financing share acquisitions, warehousing shares under employee share ownership schemes or trust, and management buy-ins and buy-outs;28

f) setting up Employee, Management and Community Share Ownership Schemes or Trusts as part of the 51% indigenous shareholding to ensure the broad-based participation of indigenous Zimbabweans in the economy;29

g) reserving business sectors such as the production of food and cash crops, employment agencies, estate agencies, milk processing, marketing and distribution, advertising agencies, and the provision of local arts and craft to indigenous Zimbabweans;30 and

h) providing a dispute resolution platform in the form of the Administrative Court to be available to any business aggrieved by a Minister's decision to apportion 51% of such an entity to indigenous Zimbabweans.31

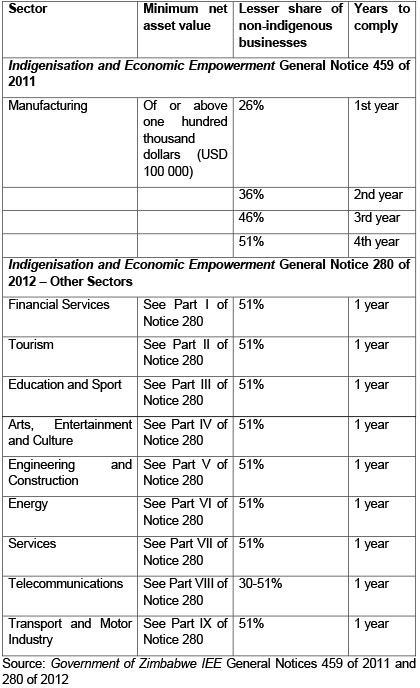

The methodology for implementing the controversial IEEA32 is prescribed in the equally controversial Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) Regulations.33The controversy lies mainly in the 51% indigenisation equity threshold imposed on all foreign-owned businesses, as illustrated in the Table below:

The specified share transactions issues regarding the 51 % equity threshold appear to constitute a threat to business investments in that they are not negotiable.34 Section 3(5) of the IEEA provides that an exemption from complying with the said regulatory requirements is permissible only in instances where the foreign-owned company is able to furnish evidence that the transfer of a lower percentage of its shares or a longer period of achieving the indigenisation objectives is appropriate in its special or unique circumstances.35 However, section 3(5) has been a source of contention as policy makers had appeared to suggest that it implies that the 51% equity threshold is negotiable.36 In fact section 3(5) suggests otherwise, as it provides that:

The Minister may prescribe that a lesser share than fifty-one per centum or a lesser interest than a controlling interest may be acquired by indigenous Zimbabweans in any business in terms of subsections (1)(b)(iii), (1)(c)(i), (1)(d) and (e) in order to achieve compliance with those provisions, but in doing so he or she shall prescribe the general maximum timeframe within which the fifty-one per centum share or controlling interest shall be attained.37

In justifying the indigenisation programme as reflected in the IEEA, the government has been consistent in advancing and relying upon a populist argument that the country's land and mineral resources should benefit Zimbabweans and not only multinational companies.38 This is probably premised on the genuine need to ensure that indigenous Zimbabweans and not multinational companies receive the greater share of the proceeds flowing from the exploitation of the country's land and mineral resources.

Section 2(1) of the IEEA pursues a distributive justice agenda.39 This is because the ultimate policy goal of transferring the ownership of the land and mineral resources to indigenous Zimbabweans is the closing of the ever-widening inequalities40 between the wealthy and the indigent.41Accordingly, a theoretical construction such as the distributive justice theory, which advocates a just and fair distribution of the benefits and proceeds originating from the land and mineral resources in any society, becomes strongly affirming of the Zimbabwean indigenisation process.42Accordingly, the government should in this regard be applauded for trying to ensure that multinational corporations do not continue to take the larger share of the said proceeds43 and benefits while indigenous people remain exposed to various forms of exploitation.44 To address such socio-economic injustices, it is clearly plausible to adopt legal policies whose objectives are directed at reform of the society's economic order in order to achieve an equitable, fair and just distribution of responsibilities and benefits.45

However, it must be ascertained whether the contemporary capitalist and/or neo-liberal economic order46 can effectively accommodate social policies designed to bridge the gap between the rich and the poor and, for that purpose, embrace the implementation of socio-economic programmes implicit in the distributive justice theory, such as indigenisation programmes.47

Alvarez has pointed out that today neoliberal ideology shapes institutions whose policies account for contemporary international economic law.48Governments are not an exception. This concern is readily manifest in the fact that whereas section 3 of the IEEA and the broad tenor of Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment General Notice 114 of 2011 is that every Zimbabwean should benefit from the country's resources, section 2(1) of the IEEA excludes the State/Government as a specific beneficiary of indigenisation. This suggests that only individuals and juristic persons were earmarked to benefit from the indigenisation programme. Reference in section 2(1) of the IEEA is made to the following categories of beneficiaries as being the targets of indigenisation: "1) a natural person, 2) a company 3) an association, syndicate or partnership amongst others ...".49

There may be some justification for the exclusion of the government as a direct beneficiary of indigenisation. After all, the listed categories of beneficiaries are subjects of the State, whose business operations have the potential to directly or indirectly contribute to the fiscus and/or revenue base of the country. However, the net effect of excluding the State as a direct beneficiary of the indigenisation laws in Zimbabwe is that unscrupulous individuals50 and companies owned by such individuals or persons related to or connected to them have become largely responsible for an upsurge in corruption.51 As a result the gains from the mineral resources which should be available for the pursuit of the best interests of the State and its subjects at large are being externalised through the collusion of these companies and individuals.52 If excluding the State as a beneficiary of indigenisation53promotes corrupt business practices such as fronting, then the underlying legal or policy position adopted is problematic, at least in the Zimbabwean context.54 As a result of the exclusion, instead of increasing the participation of the black majority, the current regulatory practice may increase the pace of widening inequality between the wealthy and the indigent;55 and it could also undermine the implementation of the indigenisation programmes and laws as the resources necessary for that purpose would not be available.56

Against this background, unregulated, unethical and fraudulent practices such as business fronting, which subvert the pre-eminent objective of increasing the participation of the indigenous Zimbabweans57 in the economic mainstream, must be systematically confronted.

3 Business fronting in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwean courts have not had the opportunity to pass judgement on the troubling issue of business fronting and the duty of State organs in responding to allegations of fronting. This could be due in part to the politicised nature of the country's judicial system.58 The indigenisation programme was introduced and implemented at the behest of the ruling party, the Zimbabwe African National Union - Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF).59Not surprisingly, most of the current beneficiaries of the indigenisation programme are people sympathetic to ZANU-PF and its policies.60 These beneficiaries include members of the judiciary such as judges, who received farms forcefully taken from white owners at the height of the chaotic land reform programme.61 The persons who perpetrate violations of indigenisation laws also appear to be members of ZANU-PF, who know that as long as they are in the good books of the country's and party's leadership they will not be prosecuted.62 The practical result is that there is no rapidly developing jurisprudence on business fronting in Zimbabwe. However, this has not stopped concerns being raised in the media regarding incidents of business fronting. Surprisingly, President Robert Mugabe himself has added his voice to the increasing chorus of concerns about incidents of business fronting,63 which should, under the current economic crisis of Zimbabwe, be regarded as a serious crime.64

Business fronting in Zimbabwe can be attributed to a number of factors. Among those involved are:

a) disgruntled foreign investors who use corrupt and greedy well-connected business elites to retain the investments they lost and/or stand to lose in the face of the aggressive indigenisation policy in Zimbabwe;65

b) unscrupulous and well-connected elites who seek to maximise their returns from the spoils of the haphazard indigenisation programme;66and

c) ordinary people who benefited from indigenisation programme on merit, accidentally or through political patronage, and have realised that the indigenisation programme lacks the necessary implementation-related financial support and is simply being used to score political points.67

This realisation has made the ordinary citizens who are beneficiaries of the indigenisation programme comfortable with fronting for foreign business persons in return for huge sums of money which the government cannot offer them. These citizens have come to view the indigenisation programmes as counter-productive and a significant threat to investment security.68 It is thus not surprising that indigenisation policies are closely associated with the economic decline which has characterised Zimbabwe's economy in the last decade.69

Business fronting has been covertly taking place in Zimbabwe70 probably because there is no specific legislation which provides authoritative guidance as to what fronting is or prescribes deterrent measures against those who engage in the practice. In the absence of a specific piece of legislation which defines business fronting,71 how it is monitored and a prescription of the consequences, the fundamentally plausible programme will continue to flounder. As the law currently stands in Zimbabwe, practices which constitute fronting in the commercial arena are not clearly outlined for interpreters of the IEEA. But the success of any law lies largely in its clarity.72It is therefore submitted that the omission of specific business fronting provisions in the IEEA detailing the definition of the conduct, how it is to be policed and the consequences thereof undermines the attainment of the IEEA's transformative objectives.73 Under the law as it currently stands, any fraudulent and/or dishonest business conduct is dealt with in terms of the Criminal Law Codification and Reform Act (CLCRA).74 Under the CLCRA, the penalty for refusing to comply with the business-related provisions of the Act is a maximum fine at level 12,75 which is currently USD 2000, five years imprisonment or both.76 Such a penalty is clearly incapable of having a significant deterrent effect when compared to the real and potential benefits of the illicit practice.

A closer analysis of the IEEA points to the existence of a number of clauses which appear to have been specifically included to preserve the interests of the wealthy in Zimbabwe.77 For example, the IEEA mandates the responsible Minister to keep a record of individuals who stand as prospective beneficiaries of shareholder interests in non-indigenous companies.78 Further, the regulations provide the Minister with an essentially unlimited discretion to determine whether or not to accept or reject an indigenisation proposal or to attach conditions to the approval of such a proposal, a discretion which is conducive to the politics of patronage.79 Recent evidence produced before a parliamentary portfolio committee on Mines and Mineral resources revealed Community Trust pledges that were covert80 and unaccounted for,81 apparently made at the directive of the former Minister of Youth Empowerment and Indigenisation, Mr Saviour Kasukuwere,82 in respect of allegedly inaccurate and nonexistent indigenisation plans.83

The chaotic state of affairs surrounding the Community Share Ownership Trusts (CSOTs) therefore makes it critically important to highlight the fact that the IEEA stipulates that "no appeal lies against a Ministerial decision to reject an indigenisation plan".84 Further, it provides that:

... the noting of an appeal ... shall not, pending the determination of the appeal, suspend the decision, order or other action appealed against unless the Administrative Court directs otherwise.85

As already highlighted above, Zimbabwean courts currently have a tendency not to act independently of the executive, as attempts to do so can lead to a purging of judicial officials.86 Accordingly, the implementation of legislation such as the IEEA can be manipulated to enrich politically connected indigenes and thereby promote, rather than discourage, the practice of business fronting in Zimbabwe.87

4 Regulation of fronting in South Africa

The fronting challenge in South Africa was exacerbated by the fact that, until 2011, the courts had not definitively pronounced on government's duties in responding to fronting practices; but the opportunity arose in the landmark case of Viking Pony Africa Pumps (Pty) Ltd v Hidro-Tech Systems (Pty) Ltd.88This case allowed the Constitutional Court to pronounce itself inter alia on the policy rationales of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), which it regarded as a constitutionally mandated governmental response to "one of the most vicious and degrading effects of racial discrimination in South Africa", being ".. .the econom ic exclusion and exploitation of black people".89The Constitutional Court's ruling in the Viking Pony case effectively imposes an obligation on an organ of state that has received a complaint about alleged fronting to properly investigate the complaint and to act accordingly.90

The ruling in the Viking Pony case was followed in 2013 by the passing into law of the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Amendment Act (Amendment Act).91 Fronting in the Amendment Act is regulated in a combination of three ways focusing on: (a) definition, (b) monitoring, and (c) consequences. Fronting has often been used as a token of the superficial inclusion of historically disadvantaged persons into mainstream economic activities with no actual transfer of wealth or control.92 The provisions of the Amendment Act are intended to provide authoritative guidance as to what fronting is, and to prescribe deterrent measures against those who violate its provisions. The South African B-BBEE Amendment Act adopted a plausible dualist approach to addressing the challenge of defining business fronting; the one approach focusing on providing a comprehensive yet elastic definition of fronting and the other aimed at establishing a strong and properly resourced institutional framework for implementation.93 The first facet of the said definition is a broad, catch-all definition of what constitutes business fronting. In this regard section 1 (e) of the B-BBEE Amendment Act defines "fronting practice" as: "a transaction, arrangement or other act or conduct that directly or indirectly undermines or frustrates the achievement of the objectives of this Act or the implementation of any of the provisions of this Act Clearly, the wording of this broad definition includes the three most common forms of business fronting, namely window dressing,94benefit diversion95 and the use of opportunistic intermediaries.96

The legislature through section 1 (e) of the B-BBEE Amendment Act adopted a plausible, catch-all, open-ended definition of business fronting,97 which is an approach that is usually characterised by an element of vagueness intended, in this particular case, to ensure coverage of conduct or activities which may amount to business fronting but which may have been unwittingly excluded by the legislature.98 The second facet of the definition consists of a closed list of practices, conduct or situations falling within the regulatory scheme of business fronting.99

In addition to the dual-faceted definition of fronting, the B-BBEE Amendment Act establishes a Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Commission (B-BBEE Commission) which is required to effectively assume the role of the regulatory watchdog over issues pertaining to the B-BBEE Act.100 The B-BEE Commission which will be established as:

... a juristic person with the duty of providing oversight to the B-BEEE process has the responsibility to: 1) investigate cases of fronting; 2) investigate complaints; and 3) receive and monitor reports on B-BBEE from organs of state and listed entities.101

The role of the B-BBEE Commission102 could be likened to a limited extent to the role of the Anti-Corruption Commission in Zimbabwe.103 However, the difference between the two is that the B-BEE Commission deals with matters specifically related to the BEE programme, which makes it a specialised juristic person unlike the Anti-Corruption Commission, which has no defined area of speciality and appears to have been intended to deal with all matters of corruption.104 The effectiveness of such a commission is likely to be minimal, as it lacks expertise on the multiplicity of complex issues which are required to come before it. Further the Anti-Corruption Commissioners are appointed by the State President and function on the lines of political patronage, just like the judiciary in Zimbabwe, which fact places the prospects of the Commission's effectiveness in serious doubt.105

Furthermore, the penalties prescribed for business fronting under the B-BBEE Amendment Act are fairly severe and therefore more likely to generate an effective deterrence effect than those in their Zimbabwean counterparts. This submission flows from the fact that the B-BBEE Amendment Act creates a number of offences and associated penalties.106For example, it creates an offence for the intentional misrepresentation of information for the purposes of securing a favourable B-BBEE status; providing false information to a government entity; and failure by a public officer to report any offence in terms of the B-BBEE Act.107 A person convicted in terms of the B-BBEE Amendment Act could be liable to a fine108or imprisonment of up to ten years for a section 13O(1)(a)-(d)109 violation and a period not exceeding 12 months for a section 13O(2)110 violation. There is no guidance as to what the extent of imprisonment could be, as fronting is not yet specifically legislated against in the IEEA. However, based on the experience of the implementation of indigenisation and related regulations in Zimbabwe thus far, it is highly probable that a stiff penalty may be imposed on a person who is not politically connected and who is found to have engaged in conduct resembling business fronting. Another option available to the authorities in Zimbabwe is to rely on the level 12 penalty provided in the CLCRA. That penalty currently stands at a miserly USD 2000 which, it is submitted, would hardly deter anyone from committing a potentially high profit-yielding economic crime such as business fronting.111

In respect of juristic persons, the B-BBEE Amendment Act allows the imposition of a fine of up to a maximum of ten per cent of the juristic person's annual turnover.112 And in addition to the penalties, any person convicted of any offence under the B-BBEE Amendment Act may be banned from further contracting with any Government entity.113 It is submitted in this respect that the penalties imposed by the South African B-BBEEA Act are on the face of it sufficiently stiff to produce the much desired deterrence effect from the perspective of would-be offenders.114 In this regard the Zimbabwean legislative framework presents further significant weaknesses. The penalty of USD 2000 clearly does not match up to the ten years imprisonment or fine of 10% of the annual turnover of a company provided for in the South African legislative regime. This particular difference in the regulation of fronting between the two countries might explain why the practice exists in Zimbabwe. Accordingly, to the extent that fronting threatens to derail the country's controversial indigenisation programme, the penalty-related provisions of the Zimbabwean legislative framework stand to gain much strength from a reform process which embraces the South African approach as epitomising "best practice" in the prevention and regulation of business fronting.

5 Lessons from South Africa

The reason for South Africa's adopting the anti-fronting legislation was that within a few years of introducing the Black Economic Empowerment (hereinafter BEE) programme115 it became evident that in practice the benefits were not reaching large numbers of those intended to be the beneficiaries of the programme.116 Rather, the pattern emerged of a few well-connected business elites colluding with politically connected black elites to capture the opportunities spawned by the programme.117 A robust and systematic approach had to be adopted to address this untenable situation.118 The result was the passing of the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Amendment Act (Herein after B-BBEE Amendment Act).119This Act amended the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act120with the primary objective of addressing all known and perceived weaknesses in the current regulatory framework.121

Also see Zuma "B-BBEE Not Just About Benefiting a Few Individuals"; Andreasson 2011 B&S 647; Bogopane 2013 JSS 277. See further Yokogawa 2010 http://www.yokogawa.com/za/cp/overview/za-bee.htm.

It is submitted that Zimbabwe can draw lessons from South Africa's challenges with business fronting and related practices in the following ways:

a) by acknowledging that in practice, the benefits of the indigenisation programme are not reaching large numbers of the previously disadvantaged indigenous Zimbabweans intended to be the beneficiaries, due to the prevalence of corrupt and unethical business practices such as business fronting, and hence, by accepting the need for effective regulatory mechanisms to address such a challenge;

b) by adopting a clear definition of what amounts to business fronting, as has been done by South Africa in the B-BBEE Amendment Act of 2013;

c) by outlining the monitoring mechanisms for business fronting; and

d) by clearly elaborating the consequences of fronting practices by way of the statutory prescription of severe penalties that will act as effective deterrents.

6 Conclusion

In their current state, Zimbabwe's IEEA and related Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Regulations do not benefit most indigenous Zimbabweans. Instead, as correctly pointed out by Magure, they appear to be advancing the interests of politically connected elites.122 This is the result of deficiencies at the levels both of legal instrument design and of institutional enforcement. In parts one and five of this article it has been pointed out that the major deficiency of the IEEA is the omission to systematically address the problem of business fronting. Accordingly, it is proposed that the IEEA be amended and reinforced with anti-fronting provisions accompanied by effective enforcement mechanisms. Two possible approaches could be adopted, as follows:

a) amending the IEEA by inserting provisions which specifically define what constitutes business fronting, how it is to be policed, and the consequences of engaging in fronting practices. This approach would make the IEEA a comprehensive one-stop-shop for obtaining adequate guidance on illegal and unethical business practices relating to indigenisation; or

b) enacting a separate piece of legislation that regulates business fronting practices in the mould of South Africa's B-BBEE Amendment Act.

Of the two proposed approaches, the first option would be preferred, as there is an already existing legal framework regulating indigenisation issues in the form of the IEEA. To that end, incorporating the anti-fronting provisions in that legislation would be more cost-effective and less time-consuming.

And in undertaking such a law reform process, Zimbabwe can draw valuable lessons from South Africa,123 which has recently amended its BEE legislation to combat business fronting. In promulgating the amendment statute, South African policy makers accepted that business fronting is a significant contributory factor preventing the success of the country's indigenisation programme, especially by facilitating benefits diversion, creating opportunistic beneficiaries and thereby limiting the trickle-down effects as well as the overall impact of the related instruments and initiatives.124 It is against this background that the B-BBEE Amendment Act is commended to Zimbabwean law and policy makers as a model, seeing that it contains substantive definitional and implementation-related provisions which seem adequate to the task of addressing the formidable threat to the success of the indigenisation programme posed by business fronting.

Bibliography

Literature

Alvarez SA and Barney JB "Opportunities, Organisations and Entrepreneurship" 2008 SEJ 171-173 [ Links ]

Andreasson S "Economic Reforms and 'Virtual Democracy' in South Africa and Zimbabwe: The Incompatibility of Liberalisation, Inclusion and Development" 2003 JCAS 371-384 [ Links ]

Andreasson S "Indigenisation and Transformation in Southern Africa" Paper prepared for the British International Studies Association Annual Conference (15-17 December 2008 Exeter) [ Links ]

Andreasson S "Confronting the Settler Legacy: Indigenisation and transformation in South Africa and Zimbabwe" 2010 PG 424-433 [ Links ]

Andreasson S "Understanding Corporate Governance Reform in South Africa: Anglo-American Divergence, the King Reports, and Hybridization" 2011 B&S 647-673 [ Links ]

Arrowsmith S "National and International Perspectives on the Regulation of Public Procurement: Harmony or Conflict" in Arrowsmith S and Davies A (eds) Public Procurement: Global Revolution (Kluwer Law International London 1998) 5-26 [ Links ]

Black Economic Empowerment Commission A National Integrated Black Economic Empowerment Strategy (Skotaville Press Johannesburg 2001) [ Links ]

Bogopane LP "Evaluation of Black Economic Empowerment Policy Implementation in the Ngaka Modiri Molema District North West Province, South Africa" 2013 JSS 277-288 [ Links ]

Carmody P "Ecolonization and the Creation of Insecurity Regimes: The Meaning of Zimbabwe's Land Reform Programme in Regional Context" in Palloti A and Tornimbeni C State, Land and Democracy in Southern Africa (Routledge New York 2016) 169-182 [ Links ]

Carter S and Wilton W "Don't Blame the Entrepreneur, Blame Government: The Centrality of the Government in Enterprise Development; Lessons from Enterprise Failure in Zimbabwe" 2006 JEC 65-84 [ Links ]

Cheadle, Thompson and Hayson Inc et al Black Economic Empowerment: Commentary, Legislation and Charters (Juta Cape Town 2005) [ Links ]

Chekera YT and Nmehielle VO "The International Law Principle of Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources as an Instrument for Development: The Case of Zimbabwean Diamonds" 2013 AJLS 69-101 [ Links ]

Chiduza L "Towards the Protection of Human Rights: Do the New Zimbabwean Constitutional Provisions on Judicial Independence Suffice" 2014 PELJ 367-418 [ Links ]

Chitereka G and Hamauswa S "Mining Rights and Mineral Related Corruption in Zimbabwe: The Case of Gwanda, Kwekwe and Chiadzwa Mining Areas" 2014 ZJPE 69-83 [ Links ]

Chowa T and Mukuvare M "Zimbabwe's Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Programme (IEEP) As an Economic Development Approach" 2013 RJE 1-18 [ Links ]

Fargher M "Whitewashed equality" The Herald Zimbabwe (4 November 2013) 10 [ Links ]

Fredriksson P and Svensson J "Political Instability, Corruption and Policy Formation: The Case of Environmental Policy" 2003 JPE 1383-1405 [ Links ]

Gallagher J "The Battle for Zimbabwe in 2013: From Polarization to Ambivalence" 2015 JMAS 27-49 [ Links ]

Gamble A Crisis Without End? The Unravelling of Western Prosperity (Palgrave Macmillan Victoria 2014) [ Links ]

Genev VI "The 'Triumph of Neoliberalism' Reconsidered: Critical Remarks on Ideas-centered Analyses of Political and Economic Change in Post- communism" 2005 EEPS 343-378 [ Links ]

Goko C "Honour 2006 Plan, Zimplats Urges Govt" Daily News Zimbabwe (29 April 2014) 12 [ Links ]

Government of Zimbabwe First Report of the Thematic Committee on Indigenisation and Empowerment on the Operations of the Community Share Ownership Trusts and Employee Share Ownership Schemes SC (The Government Harare 2015) [ Links ]

Gumede W Corruption Fighting Efforts in Africa Fail Because Root Causes Are Poorly Understood (Foreign Policy Centre Washington DC 2012) [ Links ]

Harvey D "Neo-liberalism as Creative Destruction" 2006 GA 145-158 [ Links ]

Helmsing B Perspectives of Local Economic Development: A Review (International Institute of Social Studies The Hague 2010) [ Links ]

Kalula E and M'Paradzi A "Black Economic Empowerment: Can There be Trickle-down Benefits for Workers?" 2008 SJ 108-130 [ Links ]

Kaplow L "The General Characteristics of Rules" in Bouckaert B and De Geest G (ed) Encyclopedia of Law and Economics (Edward Elgar Cheltenham 2000) 512-513 [ Links ]

Leal-Arcas R International Trade and Investment Law: Multilateral, Regional and Bilateral Governance (Edward Elgar Cheltenham 2010) [ Links ]

Leon T "Creeping Expropriation of Mining Investments: An African Perspective" 2009 JENRL 33-40 [ Links ]

Libby R and Woakes M "Nationalisation and the Displacement of Development Policy in Zambia" 1980 ASR 33-50 [ Links ]

Mabhena C and Moyo F "Community Share Ownership Trust Scheme and Empowerment: The Case of Gwanda Rural District, Matebeleland South Province in Zimbabwe" 2014 IOSR-JHSS 72-85 [ Links ]

Madhuku L "Constitutional Protection of the Independence of the Judiciary: A Survey of the Position in Southern Africa" 2002 JAL 232-258 [ Links ]

Magure B "Foreign Investment, Black Economic Empowerment and Militarized Patronage Politics in Zimbabwe" 2012 JCAS 67-82 [ Links ]

Magure B "Land, Indigenisation and Empowerment: Narratives that Made a Difference in Zimbabwe's 2013 Elections" 2014 JAE 17-47 [ Links ]

Makoni PL "The Impact of the Nationalisation Threat on Zimbabwe's Economy" 2014 COC 160-179 [ Links ]

Matunhu M "A Critique of Modernization and Dependency theories in Africa: Critical Assessment" 2011 AJHC 65-72 [ Links ]

Matunhu M "The Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Policy in Zimbabwe: Opportunities and Challenges for Rural Development" 2012 SAPRJ 5-20 [ Links ]

Mazingi L and Kamidza R "Inequality in Zimbabwe" in Jauch H and Muchena D (eds) Us Apart: Inequalities in Southern Africa (Open Society Initiative of Southern Africa Johannesburg 2011) 322-383 [ Links ]

Mbeki M Architects of Poverty: Why African Capitalism Needs Changing (Picador Africa Johannesburg 2009) [ Links ]

Mhiripiri N "Legitimising the Status Quo through the Writing of Biography: Ngwabi Bhebe's Simon Vengesayi Muzenda and the Struggle for and Liberation of Zimbabwe" 2009 JLS 83-98 [ Links ]

Monibot G How Did We Get into this Mess? Politics, Equality, Nature (Verso Books London 2016) [ Links ]

Moyo S "Land Reform and Redistribution in Zimbabwe since 1980" in Moyo S and Chambati W Land and Agrarian Reform in Former Settler Colonial Zimbabwe (CODESRIA Dakar 2013) 29-78 [ Links ]

Moyo S "The Political Economy of Transformation in Zimbabwe: Radicalisation, Structural Change and Resistance" in Sall E (ed) Africa and the Challenges of the Twenty-first Century: Keynote Lectures Delivered at the 13th General Assembly of CODESRIA (Rabat Morocco, December, 2011) (CODESRIA Dakar 2015) 23-46 [ Links ]

Moyo S "Primitive Accumulation and the Destruction of African Peasantries" in Patnaik U and Moyo S (eds) The Agrarian Question in the Neoliberal Era: Primitive Accumulation and the Peasantry (Fahamu Books and Pambazuka Press Cape Town 2011) 61 -85 [ Links ]

Moyo S "The Scramble for Land in Africa" Paper presented at the Round Table Dialogue on Land Reform, Land Grabbing and Agricultural Development in Africa in the 21st Century (17-18 June 2013 Addis Ababa) [ Links ]

Munyedza P "The Impact of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act of Zimbabwe on the Financial Performance of Listed Securities" 2011 BEJ 1-14 [ Links ]

Murombo T "Law and the Indigenisation of Mineral Resources in Zimbabwe: Any Equity for Local Communities" 2010 SAPL 568-589 [ Links ]

Murombo T "Regulating Mining in South Africa and Zimbabwe: Communities, the Environment and Perpetual Exploitation" 2013 LEDJ 31-49 [ Links ]

Ncube T "Empower the Majority, Not a Select Few" Sunday Times (1 August 2004) 17 [ Links ]

Ndlela D "Scandal Rocks Zuva Petroleum" Financial Gazette (20 February 2014) 2 [ Links ]

Ngwerume KJ and Massimo ET "Contribution of the Bindura Community Share Ownership Trust to Rural Development in Bindura Rural District Council of Zimbabwe" 2014 JPAG 1-17 [ Links ]

O'Connel P Vindicating Socio-economic Rights: International Standards and Comparative Experiences (Routledge London 2012) [ Links ]

Osode PC "Advancing the Cause of Black Economic Empowerment through the Use of Legal Instruments" in Osode PC and Glover G (ed) Law and Transformative Justice in Post-Apartheid South Africa (Spekboom Louis Trichardt 2010) 261-290 [ Links ]

Osode PC "The New Broad-Based Economic Empowerment Act: A Critical Evaluation" 2004 SJ 108-114 [ Links ]

Philip M "The Land Grab Corporate Food Regime Restructuring" 2012 JPS 681-701 [ Links ]

Posner E "Standards, Rules, and Social Norms" 1997 Harv JL & Pub Pol'y 101-117 [ Links ]

Quinot G and Arrowsmith S "Introduction" in Quinot G and Arrowsmith S (eds) Public Procurement Regulation in Africa (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2013) 1-22 [ Links ]

Raban O "The Fallacy of Legal Certainty: Why Vague Legal Standards May be Better for Capitalism and Liberalism" 2010 PILJ 175-191 [ Links ]

Raftopoulos B "The State, NGOs and Democratisation" in Moyo S, Makumbe J and Raftopoulus B (eds) NGOs, the State and Politics in Zimbabwe (SAPES Books Harare 2000) 21-45 [ Links ]

Raftopoulos B and Moyo S "The Politics of Indigenisation in Zimbabwe" 1995 EASSRR 17-33 [ Links ]

Ratnapala S Jurisprudence (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009) [ Links ]

Rawls A Theory of Justice (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Massachusetts 1971) [ Links ]

Raz J "Legal Principles and the Limits of Law" 1972 Yale LJ 823- 841 [ Links ]

Rood L "Nationalisation and Indigenisation in Africa" 1976 JMAS 427-447 [ Links ]

Rood L "The Impact of Nationalisation" 1977 JMAS 489-494 [ Links ]

Scalia A "The Rule of Law as a Law of Rules" 1989 U Chi L Rev 1175-1181 [ Links ]

Schauer F Playing by the Rules (Clarendon Press Oxford 1991) [ Links ]

Selby A Commercial Farmers and the State: Interest Group Politics and Land Reform in Zimbabwe (D Phil-thesis Oxford University 2006) [ Links ]

Sibanda A "The Corporate Governance Perils of Zimbabwe's Indigenisation Economic Empowerment Act 17 of 2007" 2014 IJPLP 24-36 [ Links ]

Sithole AK and Chikerema A "Property Ownership by Zimbabwean Women: A Myth or a Reality?" 2014 ZJPE 84-96 [ Links ]

Southall R "Ten Propositions About Black Economic Empowerment in South Africa" 2007 RAPE 67-84 [ Links ]

Stark B "Jam Tomorrow: Distributive Justice and the Limits of International Economic Law" 2010 BC Third World LJ 3-34 [ Links ]

Stark B "Jam Tomorrow: A Critique of International Economic Law" in Carmody C, Garcia F and Linarelli J (eds) Global Justice and International Economic Law: Opportunities and Prospects (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2012) 261-272 [ Links ]

Sustein CR "Problems with Rules" 1995 CLR 1021-1032 [ Links ]

Tebbit M Philosophy of Law: An Introduction 2nd ed (Routledge London 2005) [ Links ]

Tekere E A Lifetime of Struggle (SAPE Books Harare 2007) [ Links ]

Warikandwa TV and Osode PC "Legal Theoretical Perspectives and Their Potential Ramifications for Proposals to Incorporate a Trade-labour Linkage into the Legal Framework of the World Trade Organisation" 2014 SJ 41-69 [ Links ]

Zikhali W, Ncube G and Tshuma N "From Economic Development to Local Economic Growth: Income Generating Projects in Nkayi District, Zimbabwe" 2014 IJHSS 27-33 [ Links ]

Zimudzi TB "A Predictable Tragedy: Robert Mugabe and the Collapse of Zimbabwe" 2012 JCS 508-511 [ Links ]

Zuma J "B-BBEE Not Just About Benefiting a Few Individuals" Keynote Address to the Broad-Based Economic Empowerment Summit (3 October 2013 Midrand) [ Links ]

Case law

Asia

AMCO v Republic of Indonesia (Merits) 1992 89 ILR 368

Bharat Cooperative Bank (Mumbai) Ltd v Employees Union 2007 4 SCC 685

Hamdard (Wakf) Laboratories v Deputy Labour Commissioner 2007 5 SCC 281

Himalayan Tiles and Marble (P) Ltd v Francis Victor Coutinho 1980 3 SCC 223

Mahalakshmi Oil Mills v State of AP 1989 AIR 335

NDP Namboodripad v Union of India 2007 4 SCC 502

England

Dilworth v Commissioner of Stamps (Lord Watson) 1899 AC 99

South Africa

Affordable Medicines Trust v Minister of Health 2006 3 SA 247 (CC)

Bengwenyama Minerals (Pty) Ltd v Genorah Resources (Pty) Ltd 2011 4 SA 113 (C)

Chairperson, Standing Tender Committee v JFE Sapela Electronics (Pty) Ltd 2008 2 SA 638 (SCA)

Eskom Holdings Ltd v New Reclamation Group (Pty) Ltd 2009 4 SA 628 (SCA)

Esorfranki Pipelines v Mopani District Municipality 2014 2 All SA 493 (SCA)

Millennium Waste Management (Pty) Ltd v Chairperson, Tender Board: Limpopo Province 2008 2 SA 481 (SCA)

Moseme Road Construction CC v King Civil Engineering Contractors (Pty) Ltd 2010 4 SA 359 (SCA)

National Credit Regulator v Opperman 2013 2 SA 1 (CC)

Tetra Mobile Radio (Pty) Ltd v MEC, Department of Works 2008 1 SA 438 (SCA)

Viking Pony Africa Pumps (Pty) Ltd v Hidro-Tech Systems (Pty) Ltd 2011 2 BCLR 207 (CC)

United States

De Sanchez v Banco Central de Nicaragua 770 F 2d 1385 US Court of Appeals 5th Circuit (19 September 1985)

Legislation

Namibia

New Equitable Economic Empowerment Framework Bill of 2016

South Africa

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003 Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Amendment Act 46 of 2013 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Preferential Procurement Regulations, 2011 (GN 501 in GG 34350 of 8 June 2011)

Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act 12 of 2004

Zimbabwe

Criminal Law Codification and Reform Act 23 [Chapter 9:23] of 2004 Finance Act 3 [Chapter 23:04] of 2009

Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act [Chapter 14:33] of 2007

Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) Regulations Statutory Instrument 21 of 2010 [CAP 14:33]

Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) (Amendment) Regulation Statutory Instrument 66 of 2013 [CAP 14:33]

Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment General Notice 114 of 2011

Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment General Notice 459 of 2011

Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment General Notice 280 of 2012

Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission Act 13 [Chapter 9:22] of 2004

Zimbabwe Constitution Act 20 of 2013

International instruments

African Charter on Human and People's Rights (1986)

Southern Africa Development Community Protocol Against Corruption (2001)

Internet sources

Andrews M 2008 Is Black Economic Empowerment a South African Growth Catalyst? (Or Could It Be ... ) - A Paper Presented at the Center for International Development at Harvard University, Working Paper 170 https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/getFile.aspx?Id=426 accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Anon 2012 Zimbabwe Equity Laws Should Benefit Poor: Bank Chief https://www.modernghana.com/news/399099/zimbabwe-equity-laws-should-benefit-poor-bank-chief.html accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Anon 2013 'Indigenisation Fronting is a Serious Crime' http://businessdaily.co.zw/index-id-national-zk-32850.html accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Atud V 2011 Nationalisation Case Studies: Lessons for South Africa http://www.miningweekly.com/print-version/chamber-of-mines-2011-06-22 accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Coltart D 2008 A Decade of Suffering in Zimbabwe: Economic Collapse and Political Repression Under Robert Mugabe - Centre for Global Liberty and Prosperity Development Policy Analysis Working Paper Series No 5 https://www.cato.org/publications/development-policy-analysis/decade-suffering-zimbabwe-economic-collapse-political-repression-under-robert-mugabe accessed 25 March 2015 [ Links ]

Department of Trade and Industry 2003 Black Economic Empowerment Strategy Document http://www.thedti.gov.za/economic_empowerment/bee-strategy.pdf accessed 17 March 2015 [ Links ]

Department of Trade and Industry 2007 Rationale for BEE http://www.thedti.gov.za accessed 9 September 2015 [ Links ]

Department of Trade and Industry 2013 Fronting http://www.thedti.gov.za/economic_empowerment/fronting accessed 17 March 2015 [ Links ]

Foundation for the Development of Africa 2004 What is Fronting? http://www.foundation-development-africa.org/africa_black_business/fronting.htm 3 September 2015 [ Links ]

Gaomab M 2009 The Relevance of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) to the Implementation of Competition Policy and Law in Namibia: Is It an Imperative? http://www.fesnam.org accessed 11 March 2015 Global Business Holdings 2011 http://gbholdings.org [ Links ]

Global Business Holdings 2011 The Essence of the Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment http://gbholdings.org accessed 9 September 2015 [ Links ]

Government of Zimbabwe Date Unknown Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation (Zim-Asset): Towards an Empowered Society and a Growing Economy October 2013 - December 2018 http://www.dpcorp.co.zw/assets/zim-asset.pdf accessed 1 September 2015 [ Links ]

Honeycomb Transformation 2013 Fronting a Company's Ownership http://www.honeycombtransformation.co.za/fronting-companys-ownership/accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Langa V 2014 Indigenous Businesspeople Fronting for Foreigners - Mugabe https://www.newsday.co.zw/2014/10/29/indigenous-businesspeople-fronting-foreigners-mugabe/ accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Levenstein K 2013 BEE Fronting Legislation has Serious Implications http://kasieconomics.com/2013/08/20/bee-fronting-legislation-has-serious-implications/ accessed 10 August 2015 [ Links ]

Magaisa A 2012 The Illegality of Zimbabwe's New Indigenisation Regulations in the Banking and Education Sectors http://www.zimeye.org/the-illegality-ofZimbabwe%E2%80%99s-new-indigenisation-regulations-in-the-banking-and-education accessed 23 May 2016 [ Links ]

Magaisa A 2015 The Trouble with Zimbabwe's Indigenisation Policy http://alexmagaisa.com/the-trouble-with-zimbabwes-indigenisation-policy/ accessed 19 May 2016 [ Links ]

Makombe EK 2013 I Would Rather Have My Land Back: Subaltern Voices and Corporate/State Land Grab in the Save Valley - Land Deal Politics Initiative Working Paper Series No 20 http://www.plaas.org.za/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/LDPI20Makombe.pdf accessed 23 May 2016 [ Links ]

Makwiramiti AM 2011 In the Name of Economic Empowerment: A Case for South Africa and Zimbabwe http://www.polity.org.za/article/in-the-name-of-economic-empowerment-a-case-for-south-africa-and-zimbabwe-2011-02-24 accessed 23 May 2016 [ Links ]

Matyszak D 2010 Everything You Ever Wanted to Know (And Then Some) About Zimbabwe's Indigenisation And Economic Empowerment Legislation But (Quite Rightly) Were Too Afraid To Ask http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Everything%20you%20ever%20wanted%20to%20know.pdf accessed 11 March 2015 [ Links ]

Matyszak D 2013 Digging Up the Truth: The Legal and Political Realities of the Zimplats Saga http://archive.kubatana.net/docs/demgg/rau_zimplats_saga_120423.pdf accessed 11 March 2015 [ Links ]

Matyszak D 2016 Chaos Clarified - Zimbabwe's 'New' Indigenisation Framework http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Chaos%20Clarified.pdf accessed 23 May 2016 [ Links ]

Mazingi L and Kamidza R 2011 Inequality in Zimbabwe http://www.osisa.org/sites/default/files/sup_files/chapter_5_-_zimbabwe.pdf accessed 19 May 2016 [ Links ]

Mebratie AD and Bedi AS 2011 Foreign Direct Investment, Black Economic Empowerment and Labour Productivity in South Africa http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-201111029344 accessed 17 May 2016 [ Links ]

Mpofu B 2012 Indigenisation Versus Juice: Which is the Way Forward? https://www.newsday.co.zw/2012/12/06/indigenisation-versus-juicewhich-is-the-way-forward/ accessed 17 May 2016 [ Links ]

Mugabe T 2016 Zimbabwe: New Weapon to Fight Corruption http://allafrica.com/stories/201605090140.html accessed 23 May 2016 [ Links ]

Mugabe T and Gumbo L 2014 Pay Up, Diamond Mining Firms Told http://www.herald.co.zw/pay-up-diamond-mining-firms-told/ accessed 17 May 2016 [ Links ]

Mujuru JTR 2015 Full Text of Mujuru Manifesto http://www.nehandaradio.com/2015/09/08/full-text-of-mujuru-manifesto/ accessed 9 September 2015 [ Links ]

Portfolio Committee on Mines and Energy 2013 First Report on Diamond Mining (With Special Reference to Marange Diamond Fields) 2009-2013, Presented to the Zimbabwean Parliament in June 2013 http://petergodwin.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Chininga-Parliament-Report-on-Marange-Diamond-Mining-June-2013.pdf accessed 25 March 2015 [ Links ]

Portfolio Committee on Youth, Indigenization and Economic Empowerment 2016 First Report on the Marange-Zimunya Community Share Ownership Trust (Presented to Parliament of Zimbabwe on 25 October 2016) http://www.veritaszim.net/node/1891 accessed 20 February 2017 [ Links ]

Republikein 2014 Mugabe Warns Against Fronting http://www.republikein.com.na/sakenuus/mugabe-warns-against-fronting-foreign-firms.232808 accessed 19 May 2016 [ Links ]

Robertson J 2012 Indigenisation Regulations Continue to Prevent Economic Recovery http://www.mikecampbellfoundation.com/images/Downloads/Indigenisation%20blocks%20recovery%20John%20R%2026%20July%2012.pdf accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Selby A 2007 Losing the Plot: The Strategic Dismantling of White Farming in Zimbabwe 2000-2005 - Centre for International Development, Queen Elizabeth House, Working Paper Series No 143 http://www3.qeh.ox.ac.uk/pdf/qehwp/qehwps143.pdf accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Sibanda A 2013 Striving for Broad Based Economic Empowerment in Zimbabwe: Localisation of Policy and Programmes to Matebeleland and Midlands Provinces - Ruzivo Trust Working Paper 7 http://www.ruzivo.co.zw/publications/working-papers.html?download=49: Broad%20Based%20Economic%20Empowerment%20in%20Zimababwe-Matebeleland%20and%20Midlands_PIP%20Working%20Paper.pdf accessed 17 May 2016 [ Links ]

Sokwanele 2010 The Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act (14 of 2007) http://www.sokwanele.com accessed 9 September 2015 [ Links ]

Solomon M 2012 The Rise of Resource Nationalism: A Resurgence of State Control in an Era of Free Markets or the Legitimate Search for a New Equilibrium? http://www.saimm.co.za/Conferences/ResourceNationalism/ResourceNationalism-20120601.pdf accessed 17 May 2016 [ Links ]

Transparency International 2014 Transparency Perceptions Index https://www.transparency.org/cpi2014/results accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Watson M 2010 Zimbabwe's Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act: A Historical Moment for the African Continent http://www.minorityperspective.co.uk accessed 9 September 2015 [ Links ]

Wynn C 2013 Blacks 'Fronting for Whites' on Zim Farms http://ewn.co.za/2013/11/20/Blacks-fronting-for-whites-on-Zim-farms accessed 20 May 2016 [ Links ]

Yokogawa South Africa (Pty) Ltd 2010 Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) http://www.yokogawa.com/za/cp/overview/za-bee.htm accessed 10 September 2015 [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association 2013 Update and Analysis of Extractive Sector and Mining Issues in Zimbabwe http://www.zela.org/docs/publications/2013/uae.pdf 11 March 2015 [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Democracy Institute 2014 Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions Towards the Zim-Asset Policy in Mashonaland West Province: A Snap Survey Report http://www.zdi.org.zw/en/images/zimasset.pdf accessed 23 July 2015 [ Links ]

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AJHC African Journal of History and Culture

AJLS African Journal of Legal Studies

ASR African Studies Review

B&S Business and Society

B-BBEE Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment

B-BBEE Commission Broad-Based Black Economic

Empowerment Commission B-BBEE Act Broad-Based Black Economic

Empowerment Act B-BBEEA Act Broad-Based Black Economic

Empowerment Amendment Act BC Third World LJ Boston College Third World Law Journal

BEE Black Economic Empowerment

BEJ Business and Economic Journal

BUILD Blueprint to Unlock Investment and Leverage for Development

CLCRA Criminal Law Codification and Reform Act

CLR California Law Review

COC Corporate Ownership and Control

CSOTs Community Share Ownership Trusts

DMC Diamond Mining Company

DTI Department of Trade and Industry

EASSRR Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review

EEPS East European Politics and Society

GA Geografiska Annaler

Harv JL & Pub Pol'y Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy

IEEA Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act IJHSS International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences

IJPLP International Journal of Public Law and Policy

IOSR-JHSS International Organisation of Scientific Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences

JAE Journal of African Elections

JAL Journal of African Law

JCAS Journal of Contemporary African Studies

JCS Journal of Contemporary Studies

JEC Journal of Enterprising Culture

JENRL Journal of Energy and Natural Resources Law

JLS Journal of Literary Studies

JMAS Journal of Modern African Studies

JPAG Journal of Public Administration and Governance

JPE Journal of Public Economics

JPS Journal of Peasant Studies

JSS Journal of Social Science

LEDJ Law, Environment and Development Journal

NIEEB National Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Board

PELJ Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal

PG Political Geography

PILJ Public Interest Law Journal

RAPE Review of African Political Economy

RJE Researchjournali's Journal of Economics

SADC Southern Africa Development Community

SAPL Southern African Public Law

SAPRJ Southern African Peace Review Journal

SEJ Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal

SJ Speculum Juris

U Chi L Rev University of Chicago Law Review

Yale LJ Yale Law Journal

ZACA Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission Act

ZANU-PF Zimbabwe African National Union - Patriotic Front

ZELA Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association

Zim-Asset Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable SocioEconomic Transformation

ZJPE Zimbabwe Journal of Political Economy

15 March 2017

Editor Prof C Rautenbach

* Tapiwa V Warikandwa. LLB; LLM; LLD (Fort Hare). Post-doctoral Fellow, Department of Mercantile Law, Nelson R Mandela School of Law, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. Email: TWarikandwa@ufh.ac.za.

** Patrick C Osode. LLB (Jos); BL (Nig); LLM (Lagos); SJD (Toronto). Professor, Department of Mercantile Law, Nelson R Mandela School of Law, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. Email: POsode@ufh.ac.za.

1 Gallagher 2015 JMAS 27. Also see Moyo "Political Economy of Transformation" 23 24.

2 Chowa and Mukuvare 2013 RJE 14.

3 Ngwerume and Massimo 2014 JPAG 4. Also see Government of Zimbabwe First Report of the Thematic Committee 6; Andreasson "Indigenisation and Transformation"; Matunhu 2012 SAPRJ 5; ZELA 2013 http://www.zela.org/docs/publications/2013/uae.pdf; Mabhena and Moyo 2014 IOSR-JHSS 72; and Zikhali, Ncube and Tshuma 2014 IJHSS 27.

4 See art 21(1) as read with art 22(1) of the African Charter on Human and People's Rights (1986).

5 Andreasson 2010 PG 424. Also see the case of AMCO v Republic of Indonesia (Merits) 1992 89 ILR 368 paras 405, 466; and De Sanchez v Banco Central de Nicaragua 770 F 2d 1385 US Court of Appeals 5th Circuit (19 September 1985) para 17, for a comparative analysis of similar practices in other jurisdictions in the world.

6 Section 3(1)(a) of the Zimbabwean Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act [Chapter 14:33] of 2007 (herein after IEEA) stipulates that: "at least fifty-one per centum of the shares of every public company and any other business shall be owned by indigenous Zimbabweans..." Also see ss 3(1)(b)(iii), 3(1)(c)(i) and 3(5) of the IEEA.

7 Section 2(1)(b) of the IEEA. Section 2(1)(b) must be read together with s 14 and s 20(1)(c) of the Zimbabwean Constitution Act 20 of 2013. Also see s 1 of the South African Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003 (B-BBEE Act), which provides that: "'black people' is a generic term which means African, Coloureds and Indians". In the same section of the B-BBEE Act, it further provided that "'broad-based economic empowerment' means the economic empowerment of all black people including women, workers, youth, people with disabilities and people living in rural areas through diverse but integrated socio-economic strategies ..."

8 Leal-Arcas International Trade and Investment Law 178. Also see Munyedza 2011 BEJ 9.

9 Makwiramiti 2011 http://www.polity.org.za/article/in-the-name-of-economic-empowerment-a-case-for-south-africa-and-zimbabwe-2011-02-24. The Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe once argued that, "Why should we continue to have companies and organisations that are supported by America and Britain without hitting them back? The time has come for us to revenge and one way of (doing this) is for us to use the IEEA. That Act gives us authority to take over the companies. We can begin with 51%, but in some cases we must read the riot act and say this is only 50% but if you do not lift the sanctions we will take 100%." Also see Matyszak 2010 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Everything%20you%20ever%20wanted%20to%20know.pdf; and Matyszak 2013 http://archive.kubatana.net/docs/demgg/rau_zimplats_saga_120423.pdf.

10 Section 2(1)(b) of the IEEA. Also see s 2 of the South African B-BBEE Act; Department of Trade and Industry 2007 http://www.thedti.gov.za; Global Business Holdings 2011 http://gbholdings.org; Watson 2010 http://www.minorityperspective.co.uk; and Sokwanele 2010 http://www.sokwanele.com.

11 See the definition of "indigenisation" in the s 2(1)(b) of the IEEA and the objectives of the black economic empowerment programme in s 2 of the South African B-BBEE Act.

12 Magure 2012 JCAS 67; Matyszak 2010 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Everything%20you%20ever%20wanted%20to%20know.pdf; Raftopoulos and Moyo 1995 EASSRR 17; Carter and Wilton 2006 JEC 65; Matyszak 2016 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Chaos%20Clarified.pdf; An dreasson 2003 JCAS 384; Magaisa 2015 http://alexmagaisa.com/the-trouble-with-zimbabwes-indigenisation-policy/; and Sibanda 2014 IJPLP 24.

13 Magure 2012 JCAS 68-69. Also see Tekere Lifetime of Struggle 11; and Raftopoulos "State, NGOs and Democratisation" 21 -45. The authors point out that the Government led by the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) has created a fertile environment for the emergence of a "national bourgeoisie". The national bourgeoisie consists of members of the ruling party ZANU PF who deliberately pursue their objectives as an integral part of the ruling party's politics of patronage.

14 Anon 2012 https://www.modernghana.com/news/399099/zimbabwe-equity-laws-should-benefit-poor-bank-chief.html. Also see Gaomab 2009 http://www.fesnam.org; Helmsing Perspectives of Local Economic Development.

15 Incorporating anti-fronting clauses in the IEEA or enacting anti-fronting legislation would be a sign that the Zimbabwean government is sincere in its efforts to arrest the scourge of fronting, which is a significant aspect of corruption in Zimbabwe. It will also show that the Government is serious about implementing its commitments regarding the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Protocol against Corruption adopted on the 14th of August 2001 in Blantyre, Malawi.

16 The Bill's main objective is to address the inadequacies of the existing laws on corporate governance in addressing issues of unethical business practices in Zimbabwe. The presentation of the Bill before parliament has been linked to the need to ensure that individuals, government officials, and company representatives do not defeat the objectives of the Zim Asset Policy. The Zim Asset Policy itself "... was crafted to achieve sustainable development and social equity anchored on indigenisation, economic empowerment and employment creation which will be largely propelled by the judicious exploitation of the country's abundant human and natural resources". See the full Zim Asset Policy at Government of Zimbabwe Date Unknown http://www.dpcorp.co.zw/assets/zim-asset.pdf.

17 Mugabe 2016 http://allafrica.com/stories/201605090140.html.

18 See Magure 2012 JCAS 69.

19 Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act [Chapter 14:33] of 2007 (herein after referred to as the IEEA).

20 Section 2(1) of the IEEA.

21 Moyo "Land Reform and Redistribution" 29. Also see Fargher The Herald 10; Moyo "Scramble for Land in Africa" 29; Philip 2012 JPS 681; Moyo "Primitive Accumulation" 61; Carmody "Ecolonization" 169; and Mazingi and Kamidza 'Inequality in Zimbabwe" 371.

22 Section 2(1) also defines empowerment as "...the creation of an environment which enhances the performance of the economic activities of indigenous Zimbabweans into which they would have been introduced or involved through indigenization".

23 Section 2(1) of the IEEA.

24 Section 2(1) of the IEEA.

25 Sections 3(1) and 3(5) of the IEEA. Also see Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment General Notice 459 of 2011 and Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment General Notice 280 of 2012.

26 Section 3(1)(f) of the IEEA.

27 Section 7 of the IEEA.

28 Section 12 of the IEEA.

29 Section 12(2)(a)(ii) of the IEEA.

30 Sections 3, 4 and 5 of Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) (Amendment) Regulation Statutory Instrument 66 of 2013 [CAP 14:33]. These reserved economic sectors include the following: the agricultural production of food and cash crops; transport (buses, taxis and car hire services); the retail and wholesale trades; barbershops; hairdressing and beauty salons; employment agencies; estate agencies; valet services; grain milling; bakeries; tobacco grading and packaging; tobacco processing; advertising agencies; milk processing; the provision of local arts; and marketing and distribution. Also see s 3(1)(e) of the IEEA.

31 Sections 20(1)(c) and 20(2) of the IEEA.

32 Sections 3(1)(a), 3(b)(iii), 3(c)(i), and 3(5) of the IEEA. Also see Magaisa 2012 http://www.zimeye.org/the-illegality-ofZimbabwe%E2%80%99s-new-indigenisation-regulations-in-the-banking-and-education; and Matyszak 2016 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Chaos%20Clarified.pdf 1-20.

33 See the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) Regulations Statutory Instrument 21 of 2010 [CAP 14:33], which was gazetted on the 29th of January 2010 and subsequently came into effect on the 1st of March 2010.

34 For a detailed analysis of these issues see Matyszak 2016 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Chaos%20Clarified.pdf 15-18.

35 Section 3(5) of the IEEA. Also see ss 4, 7 and 8 of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) Regulations Statutory Instrument 21 of 2010 [CAP 14:33]; and ss 4, 7 and 8 of the 2010 regulations.

36 Matyszak 2016 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Chaos%20Clarified.pdf 15-18.

37 Section 3(5) of the IEEA. Emphasis added.

38 Section 3(1)(e) of the IEEA prohibits foreign investment in sectors reserved for Zimbabweans. Also see Matyszak 2010 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Everything%20you%20ever%20wanted%20to%20know.pdf.

39 Rawls Theory of Justice 94. The distributive justice theory was originally postulated by John Rawls. The underlying rationale of this theory is that people should be compensated for their past misfortunes. In the Zimbabwean context such misfortunes would relate to the colonial injustices which precluded indigenous Zimbabweans from participating in mainstream economic activities.

40 Government of Zimbabwe Date Unknown http://www.dpcorp.co.zw/assets/zim-asset.pdf.

41 Matyszak 2010 http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Everything%20you%20ever%20wanted%20to%20know.pdf; and Sithole and Chikerema 2014 ZJPE 84.

42 Stark 2010 BC Third World LJ 3. Also see O'Connel Vindicating Socio-economic Rights 7.3; Stark "Jam Tomorrow" 263.

43 The courts in De Sanchez v Banco Central de Nicaragua 770 F 2d 1385 US Court of Appeals 5th Circuit (19 September 1985) paras 405, 466 and AMCO v Republic of Indonesia (Merits) 1992 89 ILR 368 para 17 emphasised that states do enjoy a customary international law right to regain the ownership of industries as part of their territorial and economic sovereignty. A substantial foreign ownership of national resources and/or business sectors threatens national and economic sovereignty. Also see Leal-Arcas International Trade and Investment Law 178; Chekera and Nmehielle 2013 AJLS 69; and Murombo 2013 LEDJ 31.

44 Such forms of exploitation include labour market abuse, the deprivation of basic social services, and marginalisation from participating in the Zimbabwean economy. See Mazingi and Kamidza 2011 http://www.osisa.org/sites/default/files/sup_files/chapter_5_-_zimbabwe.pdf.

45 Ratnapala Jurisprudence 335.

46 The neoliberalism economic policy model and ideology places emphasis on free trade. It allows for minimal state intervention in socio-economic affairs and aggressively advocates the freedom of capital and trade. See Monibot How Did We Get into This Mess? 12; Harvey 2006 GA 145; Gamble Crisis without End? 10; and Genev 2005 EEPS 343.

47 Warikandwa and Osode 2014 SJ 44.

48 Alvarez and Barney 2008 SEJ 171.

49 See s 2(1) of the IEEA.

50 Transparency International 2014 https://www.transparency.org/cpi2014/results. The 2014 Transparency International Global Corruptions Index reveals that Zimbabwe is one of the most corrupt states in Southern Africa and the world in general with a ranking of number 156 out of 175. In trying to explain the source of such corruption, Transparency International chairperson Jose Ugaz pointed out that: "A significantly lowly ranking is perhaps an indication of predominant bribery, absence of adequate sentencing as well as punishment for corruption and public institutions that do not act in response to citizens' needs".

51 Coltart 2008 https://www.cato.org/publications/development-policy-analysis/decade-suffering-zimbabwe-economic-collapse-political-repression-under-robert-mugabe.

52 Chitereka and Hamauswa 2014 ZJPE 69. Also see Matunhu 2011 AJHC 65; and Murombo 2013 LEDJ 33.

53 Makoni 2014 COC 160. Indigenisation is defined as "a Government-initiated process whereby it limits certain industrial sectors to its native citizens only, and hence forces foreigners (aliens) to sell those targeted assets. The Government does not have ownership of the assets, but rather ensures a stronger hold over its domestic economy and through indigenisation can encourage and ensure the growth of local firms and individuals". Also see Rood 1976 JMAS 427; and Rood 1977 JMAS 489.

54 As a possible alternative to indigenisation, the Zimbabwean Government could have considered a nationalisation policy which aims to benefit the nation as a whole as opposed to individuals and private companies owned by indigenous Zimbabweans. Nationalisation refers to the process when a government initiates "...asset seizure as part of social and economic reform to improve livelihoods of a country's nationals". See Makoni 2014 COC 160. According to Atud, nationalisation could offer the following benefits to a country. It a) allows profits to be equitably distributed amongst more people, and the country as a whole; b) leads to regional economic growth and not just national economic growth; c) focuses more on citizens' social welfare as opposed to profiteering; d) leads to a country's greater economic performance and efficiency; and e) promotes employment creation and job security. Also see Atud 2011 http://www.miningweekly.com/print-version/chamber-of-mines-2011-06-22 and Solomon 2012 http://www.saimm.co.za/Conferences/ResourceNationalism/ResourceNationalism-20120601.pdf; Leon 2009 JENRL 33; and Libby and Woakes 1980 ASR 33. See further Makoni 2014 COC 161-163 where she describes the mixed nationalisation experiences of Zambia, Chile, Venezuela and Norway. However, for nationalisation to be a success, the timing of the implementation of the programme should be right. There should also be qualified personnel to run the nationalised entities as well as capital available to fund the business operations of such entities.

55 Robertson 2012 http://www.mikecampbellfoundation.com/images/Downloads/Indigenisation%20blocks%20recovery%20John%20R%2026%20July%2012.pdf.

56 Efforts to realise the benefits of indigenisation have not achieved the intended objectives. Even supplementary policies aimed at strengthening Zimbabwe's economy so as to further enhance the viability of the indigenisation policies have not met with success. For example, the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation policy has failed due in part to the poor indigenisation policies. See Government of Zimbabwe Date Unknown http://www.dpcorp.co.zw/assets/zim-asset.pdf. Also see Zimbabwe Democracy Institute 2014 http://www.zdi.org.zw/en/images/zimasset.pdf; and Sibanda 2013 http://www.ruzivo.co.zw/publications/working-papers.html?download=49:Broad%20Based%20Economic%20Empowerment%20in%20Zimababwe-Matebeleland%20 and%20Midlands_PIP%20Working%20Paper.pdf.

57 Section 14(1) of the 2013 Zimbabwean Constitution. Also see s 2(1) of the IEEA.

58 Chiduza 2014 PELJ 369. See also Madhuku 2002 JAL 232.

59 Moyo "Land Reform and Redistribution" 29. Also see Mhiripiri 2009 JLS 83.

60 Makombe 2013 http://www.plaas.org.za/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/LDPI20 Makombe.pdf; Magure 2014 JAE 19; and Coltart 2008 https://www.cato.org/publications/development-policy-analysis/decade-suffering-zimbabwe-economic-collapse-political-repression-under-robert-mugabe.

61 Selby 2007 http://www3.qeh.ox.ac.uk/pdf/qehwp/qehwps143.pdf. Also see Selby Commercial Farmers.

62 The need to observe the rule of law has been raised as a fundamental issue by the ousted former Zanu-PF member and also former Vice-President of Zimbabwe, Dr Joice Mujuru, who in launching the political manifesto for her new political party placed emphasis on ensuring that political bigwigs are subject to the law. See Article 8(iii) of the Blueprint to Unlock Investment and Leverage for Development (BUILD) (Mujuru 2015 http://www.nehandaradio.com/2015/09/08/full-text-of-mujuru-manifesto/).

63 Langa 2014 https://www.newsday.co.zw/2014/10/29/indigenous-businesspeople-fronting-foreigners-mugabe/.

64 Murombo 2010 SAPL 568. For an analysis of the effects of incoherent policies, also see Fredriksson and Svensson 2003 JPE 1383.

65 Ndlela Financial Gazette 2.

66 Ndlela Financial Gazette 2.

67 Wynn 2013 http://ewn.co.za/2013/11/20/Blacks-fronting-for-whites-on-Zim-farms.

68 Mpofu 2012 https://www.newsday.co.zw/2012/12/06/indigenisation-versus-juicewhich-is-the-way-forward. Also see Goko Daily News Zimbabwe 12.

69 Zimudzi 2012 JCS 508.

70 Republikein 2014 http://www.republikein.com.na/sakenuus/mugabe-warns-against-fronting-foreign-firms.232808. Also see Gumede Corruption Fighting Efforts.

71 Anon 2013 http://businessdaily.co.zw/index-id-national-zk-32850.html.

72 Tebbit Philosophy of Law 47.

73 A comparison with the situation in South Africa will show that business fronting has been clearly defined, with its monitoring mechanisms clearly spelt out, as are its consequences. Namibia, which also seeks to come up with an indigenisation law, has included the definition of what fronting is in its New Equitable Economic Empowerment Framework Bill of 2016, which is still under consideration by the Namibian Parliament. See s 1(j) of the proposed NEEEF Bill.

74 Criminal Law Codification and Reform Act 23 [Chapter 9:23] of 2004 (CLCRA). Also see the new schedule of offences which became effective with the introduction of the Finance Act 3 [Chapter 23:04] of 2009.

75 See First Schedule of the CLCRA.

76 The statutory punishment provided for in the CLCRA is also similar to the one referred to in s 10(3) of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) Regulations Statutory Instrument 21 of 2010 [CAP 14:33]. The sections make it an offense to fail to submit a form (IDG01) which shows that indigenisation requirements or a proposed business transaction such as a merger, foreign investment or unbundling of a business are accompanied by an acceptable indigenisation plan, in which case the penalty is a level 12 fine (USD 2000), five years imprisonment or both.

77 For example, s 18(1) of the IEEA provides that any person who, "...under an obligation to do so, without lawful excuse, fails or refuses to pay, collect or remit any levy or any interest or surcharge connected therewith shall be guilty of an offence and liable to a fine not exceeding level six or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding one year or to both such fine and such imprisonment". In terms of the schedule of offences provided in the Finance Act 3 [Chapter 23:04] of 2009 a level six offence carries a fine of USD 300. Also see the First Schedule of the CLCRA.

78 Section 15(1) of IEEA.

79 Section 5 of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment (General) Regulations Statutory Instrument 21 of 2010 [CAP 14:33].