Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.18 n.6 Potchefstroom 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v18i6.10

ARTICLES

Experiences and challenges of evidence leaders ("prosecutors") in learner disciplinary hearings in public schools

A SmithI; J BeckmannII; S MampaneIII

IM Ed PhD candidate, University of Pretoria. E-mail: antoonsmith@yahoo.com

IID Ed. Research Fellow, Edu-HRight Research Unit, North-West University. Email: johan.beckmann21@gmail.com

IIIB Ed PhD. Lecturer, University of Pretoria. E-mail: smampane@up.ac.za

SUMMARY

After the abolition of corporal punishment at schools, teachers have been faced with an increase in unacceptable learner behaviour and threatening situations in their classrooms. An urgent need arose to address learner discipline in innovative ways. Disciplinary hearings that deal with cases of serious misconduct represent a shift away from authoritarian control towards a corrective and restorative approach. This article presents views of educators that had acted as evidence leaders ("ELs") at disciplinary hearings. Qualitative data was collected through semi-structured interviews in a district of the Gauteng Education Department. AtlasTi software was utilised to analyse the verbatim interview transcriptions. Educators that usually served as evidence leaders ("prosecutors"), but had not been trained in law, experienced problems in conducting quasi-judicial functions without proper support and training. ELs regularly experience animosity from parents and learners; are frustrated by the unwillingness and failure of the provincial education departments to act in accordance with an SGB recommendation. Disciplinary hearings are time-consuming and lawyers representing learners complicate rather than facilitate the process. These weaknesses jeopardise the efficacy and fairness of the process and may ultimately defeat the purpose of a disciplinary hearing.

Keywords: Disciplinary hearing, Evidence leader, Learner discipline, Semi-structured interviews, Qualitative research, Quasi-judicial duties

1 Introduction

There is incontrovertible evidence of significant disciplinary problems in South African public schools.1 Before the advent of democracy in 1994 there was a perception that the one of the failings of the education system in South Africa was a failure to protect the rights and interests of learners in disciplinary hearings investigating charges of misconduct against them. The alleged lack of protection for learners was attributed among other reasons to racial discrimination, authoritarianism, and a disregard for the rule of law and the principles of natural justice. The principles of natural justice form part of the common law but their application in school disciplinary matters left much to be desired in the past.2

Education policy and legislation introduced after 1994 attempted to address the perceived shortcomings in the disciplinary system applicable to learners. Sections 8 and 9 of the South African Schools Act 84 of 1996 (hereafter SASA) make provision for discipline and punishment in schools by determining among other things that each public school has to adopt a code of conduct for learners, and by providing in Section 8(5)(a) that the code of conduct should contain provisions of due process to protect the interests of the learner and any other party involved in disciplinary proceedings emanating from learner conduct in a public school. The education authorities that initiated the laws and policies apparently assumed that educators and parents would be able to handle the quasi-judicial duties imposed on them by such proceedings without making mistakes and would thus do justice to their intentions.

Disciplinary proceedings can have very serious results for learners, and it is therefore very important and that those conducting them should respect legal principles. In practice, however, it appears that legal principles are often not respected or are applied incorrectly, and that the education authorities and even the courts have set aside findings and sanctions.

Because it would appear that educators are not trained to handle the quasi-official aspects of a disciplinary hearing of a learner properly,3 and therefore frustrate the goals articulated in Section 8 of SASA, we investigated the experiences of educators who are instructed by the principal of a school to act as evidence leaders ("prosecutors") in disciplinary hearings of learners as in chapter A of the Personnel Administrative Measures (hereafter PAM).4 In this article we report on our findings, which suggest that the objectives of the legislative provisions on learner disciplinary hearings are not being achieved, that hearings could have a negative impact on education, and that evidence leaders experience a great deal of stress because they have to play important roles for which they have not been trained and for which training is not readily available.

We found that the participants generally have a sound knowledge of the procedural aspects of learner discipline, although this was acquired through "trial and error" over many years rather than through formal training. Support was not and is not forthcoming from their local education districts. The excessive amount of paperwork required and the need to be conversant with the large number of laws relevant to their work make it very demanding.

Furthermore, the inception of the disciplinary procedures required by SASA has caused many educators (and also some schools) to abandon their task of disciplining learners and to leave everything to the disciplinary committee. Participants also pointed out that witnesses have a tendency to lie under the pressure of a disciplinary hearing, or in an attempt to protect their friends. When parents make use of a lawyer or counsel to defend their case, a good number of lawyers seem to want the disciplinary hearings to proceed as courts of law and not just tribunals.

More proactive involvement by Department of Basic Education is urgently needed to support the role of the evidence leader in a disciplinary hearing, which may result in reducing the number of disciplinary hearings that need to be held by the Department of Basic Education. Disciplinary hearings are complicated and time-consuming, but they do convey the message that discipline in schools is a very important matter.

2 Background

The new constitutional and educational dispensations introduced in South Africa in the latter half of the 1990s were aimed at addressing the perceived problems regarding learner discipline, among other things, by putting provisions concerning learner disciplinary hearings in place. In drafting the provisions it was assumed that educators (both school-based and office-based ones) would be able to play specific quasi-judicial roles and to apply legal concepts (like due process and just administrative action) in educator and learner disciplinary hearings and tribunals in order to help create educational environments conducive to quality education and to ensure that justice was done.

It was also believed that the imposition of formal legal requirements on such hearings would better protect the rights of the accused learners and the educators alike, better than they had been protected under the previous dispensation, and that the constitutional provisions on just administrative action (as in section 33) would ensure that paying mere lip service to the principles of natural justice would no longer suffice. Authentic compliance with the principles of administrative justice (incorporating the principles of natural justice) would now become imperative. Among the assumptions and expectations of the law and policy makers were that the educators already in the system would be able to play the pivotal roles of evidence leaders ("prosecutors") and presiding officers in disciplinary hearings concerning serious learner misconduct, the consequences of which, for learners, may include suspension or expulsion.5

Provision was in made in education legislation for such proceedings6 and the roles of educators in those proceedings. Educators (both school-based and office-based ones, as defined in the Employment of Educators Act)7do not receive pre-service training in respect of these matters. Neither do they receive meaningful and appropriate in-service training.8 The result of this seems to be a general failure of justice, and proceedings that miss their goals. Aggrieved parties then have to turn to courts of law and other agencies in large numbers to have disputes on decisions settled - naturally at great financial and other cost to the persons and institutions involved, as well as to the country as a whole.

The education authorities have also been in the process of transforming the South African school system since 1994 by means of policy frameworks that emphasise key values denied by the previous education system, such as equity and democracy.9 This is also evident in the policy pertaining to the disciplining of learners that has been transformed from a punitive system to a corrective and restorative process.

School Governing Bodies and School Management Teams (hereafter SMTs) are required to meet their obligations to maintain democratic values when disciplining learners. Item 7 of the Guidelines for the Consideration of Governing Bodies in Adopting a Code of Conduct for Learners (hereafter Guidelines)10 explains that the management of discipline at school starts with the teachers' accountability, which refers to the required fairness during all aspects of learner discipline at schools.

The implementation of due process by school governing bodies in the disciplinary process as contemplated in SASA11 began in only in 1997 with the commencement of the SASA. It is worth mentioning that the legal principles inherent in due process were part of South African common law before 1997, but their implementation left much to be desired.12

3 Conceptual framework

The evidence leader plays a key role in the disciplinary process in a school. For the purpose of this paper the evidence leader is an educator of the school allocated the responsibility to act as evidence leader by the principal in terms of section 4.1 of chapter A PAM.13 This section provides that

In addition to the core duties and responsibilities specified in this section, certain specialised duties and responsibilities may be allocated to staff in an equitable manner by the appropriate representative of the employer [the principal].

The provision implies that the work of an evidence leader is specialised and additional to the core duties and responsibilities of educators. This would suggest that such an educator is entitled to empowerment by the employer as represented by the principal through specific professional development initiatives.

It is the task of the evidence leader to gather information with regard to a disciplinary case and to refer serious cases to disciplinary hearings. There are many guidelines of which the evidence leader must take note to manage misconduct as stipulated in SASA 14 as well as in the regulations governing a fair disciplinary process as contemplated in section 33 of the Bill of Rights in the Constitution,15which deals with administrative justice. Evidence leaders must also take cognisance of the Guidelines articulated by the Department of Education.16

School disciplinary hearings are similar to court cases and can be seen as quasi-judicial hearings to resolve learner transgressions. 17 Disciplinary hearings could also be explained as independent tribunals or forums that are established to make quasi-judicial decisions. A disciplinary committee constituted as a tribunal performs a quasi-judicial function when it investigates the alleged transgression of a learner. 18 A disciplinary hearing therefore has elements of a court hearing, but is not a hearing in a court of law.19 The presentation of evidence in such a hearing requires due process, a fact which presents many challenges to the evidence leader.

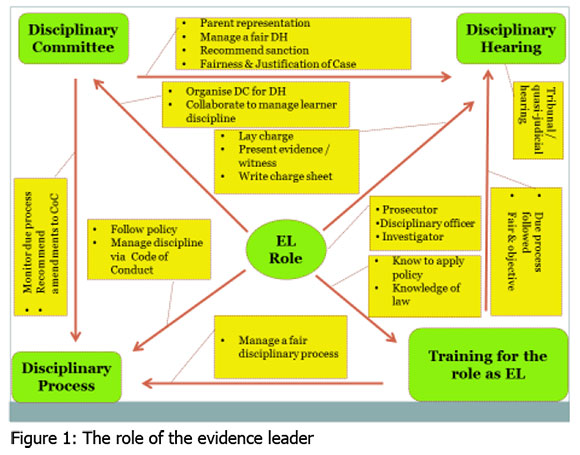

The diagram in figure 1 is a representation of the different areas in which the evidence leader plays a role and how these areas are interlinked. The five areas are:

1. Role of the educator evidence leader

2. Fair and justifiable disciplinary hearings

3. Role of the disciplinary committee in disciplinary hearings

4. Management of the disciplinary process

5. Training for the role as evidence leader

The evidence leader is also known as the "prosecutor" in disciplinary hearings, and is expected to manage an unprejudiced disciplinary process at school.20 For the purpose of this research the evidence leader is an educator of the school or a member appointed by the principal as evidence leader or disciplinary officer (prosecutor). The purpose of this research was to gain knowledge from the experiences of evidence leaders to help clarify the role and practice of evidence leaders, a fair disciplinary hearing, and due process.

Figure 1 illustrates that the evidence leader is the pivot of a due process when managing learner discipline. The evidence leader plays a crucial role in the process preceding the disciplinary hearing, which includes the initial investigation, the writing of the charge sheet, preparing witnesses and evidence in support of the case, and presenting the former in the disciplinary hearing.21 It is also the right of the evidence leader to cross-examine the accused or any witness produced by the accused learner for the defence.22 The work done by the evidence leader, although it is crucially important concerning disciplinary hearings, is still constrained by legal principles, for example the Constitutionn23and SASA,24 to ensure a just and fair disciplinary process, which includes the principle of audi alteram partem.

4 Fair and justifiable disciplinary hearings

Disciplinary hearings are similar to court cases and can be seen as quasi-judicial hearings to resolve learner misconduct.25 For the purpose of this study the disciplinary hearing is seen as a quasi-judicial hearing or forum at school, where an evidence leader presents a case before a disciplinary committee to consider serious misconduct cases.26 Disciplinary hearings are informed by the provisions of section 12(1) of the Constitution27to ensure that the disciplining of learners is fair and justifiable. This provides the learner with the right of freedom and security of the person, including the right not to be tortured in any way, and not to be punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way.28 The role of the disciplinary committee in the disciplinary hearing is intended to ensure that the hearing is objective and unprejudiced and, crucially, that learners are treated fairly, justly and are safeguarded against unfair and arbitrary treatment.

The disciplinary hearing is one part of a process which starts with an incident of alleged misconduct and is concluded with the alleged offender's being found not guilty or guilty and, in the latter event, therefore sanctioned. Disciplinary action is instituted against a learner when there is substantive evidence of misconduct or when it is in the best interest of the school and its learners for the accused learner to be punished.29The school governing body enforces corrective action regarding serious misconduct only after the learner has been given a fair and justifiable hearing, as stipulated in section 8(5) of SASA.30 Due process and adherence to the principles of natural justice are important to a fair disciplinary hearing.31

5 Due process and learner discipline

The most important principle of the disciplinary process is fairness. Managing a fair process is a key factor of the evidence leader's role and determines the success of the disciplinary hearing. It is the obligation of the evidence leader and especially of the disciplinary committee to ensure that fair procedures are followed in accordance with the legal requirements laid down in the statutes dealing with learner discipline and administrative justice, as evident in section 33 of the Constitution.32Administrative justice is a fundamental principle of administrative law, as is due process that encompasses the principles of fairness and impartiality. 33 Administrative justice denotes a system of public administration which upholds the principles of fairness, reasonableness, equality, propriety and proportionality.34 Joubert35 emphasises that reasons for a ruling must be given to the learner by the disciplinary committee as an important element of due process. Due process has to be procedurally and substantively fair.36 Procedurally fair due process means that fair procedures must be followed when an alleged breach of a Code of Conduct is investigated, a disciplinary hearing is held and corrective measures are imposed.37 Substantively fair due process implies that a fair and reasonable rule or standard exists, is known, and must have been contravened through misconduct.38

6 The legal principles focused on learner discipline

It is the duty and challenge of school principals, educators and school governing bodies to create and maintain a safe and disciplined school environment.39 It has become increasingly complicated to manage discipline in schools. It is within this environment that evidence leaders have to work. The disruptive behaviour of learners is the starting point of the evidence leaders' role. The work done by the evidence leader has to be informed by legal principles to guide his/her actions during an investigation.

The Constitution,40SASA,41 the Bill of Rights,42 and section 33 of the Constitution43(with particular reference to the right to just administrative action) have established the legal principles designed to guide the evidence leaders' actions. Section 8(5) of SASA44 has to do with due process, section 9 of the same act has to do with the principles of natural justice. These are essential guiding principles for the evidence leader in managing the disciplinary process and disciplinary hearings.

The policies regarding management discipline have a direct influence on the manner in which the evidence leader manages the disciplinary process, and should guide the evidence leader in the performance of his/her role. According to Deacon45 the evidence leader has to make use of the Code of Conduct to protect the safety of each individual involved in the disciplinary process. The aim of the Code of Conduct is to promote school standards and not to punish; it should promote progressive action and the enforcement of discipline.46 A disciplined school has functional school rules, but it is even more necessary for a disciplined school to undertake corrective disciplinary actions against those learners who disrupt teaching and learning or challenge the Code of Conduct.47

Another guiding principle is the common law, which is law that has not been enacted in legislation but is valid and recognised by the courts. Some of the significant common law principles which apply to evidence leaders are audi alteram partem, nullum poena sine lege, in loco parentis and nemo iudex in sua causa.48

Case law is also relevant. It comprises of court decisions which have been recorded in law reports and rulings in cases which establish important legal principles which are relevant at the present time.49 Case law is important in interpreting primary and secondary legislation, clarifying concepts and principles and protecting people's rights, thus resolving disputes regarding the law pertaining to disciplinary hearings.50

The law requires that a participant in quasi-judicial proceedings, such as the evidence leader or the disciplinary committee, should ensure that the hearing is conducted impartially and fairly and is transparent. All of the parties involved in a case should be able to see that justice has been done fairly.51

7 Training for the role of evidence leader

According to Beckmann,52 educators and parents who play a part in the disciplinary hearing have generally not been trained in law and may therefore experience the disciplinary process or hearing as challenging or intimidating. It stands to reason that the training of the evidence leader is vitally important, before this person can be regarded as competent to act as an evidence leader. The issue of teacher development was debated comprehensively at the National Teacher Development Summit held in July 2009.53 Training or developing an individual is meant to build the capacity of the individual which, according to Aspen,54 is a process of focusing on the needs of the individual and encouraging responsibility.

The training of evidence leaders is of the utmost importance if they are to have the opportunity to be developed in this specialised field. A number of cases taken to South African courts, for example Le Roux v Dey,55exemplify some of the reasons why the evidence leader has to be trained,56 the strenuous demands that disciplinary hearings place on the role-players, and the challenges they face in handling issues. The greatest perceived need is for more and more appropriate training of all role players regarding the major tasks that confront them, inter alia with regard to their legal rights and duties.57 Various methods have been applied by schools to train educators as evidence leader and empower them with new skills and knowledge. Watkins and Cervero58 have discussed the importance of workplace learning as it improves performance and competence in a professional's work setting.

Beckmann and Prinsloo59 propose that evidence leaders' training about what to do before a hearing should include issues such as the duty to:

1. put all facts before the disciplinary committee in a balanced and fair manner;

2. serve the ends of truth and justice, and not merely attempt to find the accused guilty;

3. comply with constitutional guidelines concerning the assumption that the accused is not guilty, unless this assumption is rebutted (the opposite is proved) on a balance of probabilities;

4. draft a charge sheet (after the consultations referred to below) which can be regarded as the central document of a disciplinary tribunal. The charge sheet has to be clear and unambiguous (not vague) and understandable on a number of issues, namely who the perpetrator of the offence or misconduct is, what the accused is accused of, where the alleged offence or misconduct took place, and when it happened;

5. afford the accused enough (a reasonable amount of) time to consider the charge sheet and to prepare;

6. notify the accused in writing of the date, time and venue of the disciplinary hearing, and inform the accused of his or her rights.

During the disciplinary hearing the evidence leader must among other things:60

1. follow hearing procedures and show courtesy towards everybody, including the presiding officer, accused and witnesses (aiming to negate the influence of American "law" television series and movies);

2. arrange for and elicit oral evidence and evidence by witnesses who made written statements, ensuring that such witnesses are available at the disciplinary hearing;

3. provide the relevant documents (if any), placed in an original file ("bundle"), with three numbered copies, one each for the presiding officer, the accused and the witnesses;

4. remember that he or she is in the role of a prosecutor and not that of a persecutor;

5. adhere to the order of proceedings in a disciplinary hearing /tribunal/inquiry (it should be remembered that a disciplinary hearing is quasi-judicial in nature, that the onus to prove the allegations against the accused lies with the evidence leader, and that the guilt of the accused needs to be proved on a balance of probabilities and not beyond all reasonable doubt, as in criminal cases). The evidence leader is at all times bound by the charge sheet.

After a disciplinary hearing where an accused learner has been found guilty, the evidence leader should summarise the proceedings of the disciplinary hearing in context, focussing on the nature of the guilt of the learner.61 Finally the evidence leader should propose a sanction which has been authorised by the disciplinary code and which could range from a warning to a final warning and to expulsion.62

The training of the evidence leader should not only focus on due process and knowledge of the law, but should also prepare the evidence leader for what to expect if the outcome of the disciplinary hearing is overturned. If that takes place, or even if the outcome is only challenged, this may have a wide range of negative effects on education at the school. 63 It follows from the above, then, that the training of principals, teachers, and in this research the evidence leader, is of fundamental importance before a person should act as an evidence leader.

8 Research design

This paper is based on research conducted by means of a case study design, investigating the role of a number of evidence leaders involved in learner disciplinary hearings. A case study can be defined as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in detail and within its real-life context.64 Information was gathered by interviewing participants who were purposefully selected, preferring evidence leaders who had been involved in disciplinary processes and disciplinary hearings. The research required a thorough literature review and careful and thoughtful posing of questions to understand the complex social phenomenon of the involvement and role of evidence leaders in the disciplinary process and disciplinary hearings.65 This design facilitated the collection of large amounts of information and detail regarding the research topic, which allowed the researchers to examine and understand a wide range of data.66 The design informed the understanding of the phenomenon as opposed to generating a mere description of the data.67 Another advantage of this design was that it created new ideas which emerged from vigilant and detailed observations of the participants during the interviews.

8.1 Methodology

The research adopted a qualitative design characterised by the detail of the study and the fact that it was context bound.68 This was a form of "field research", since the semi-structured interviews were conducted in the natural settings of the participants.69

The study followed an interpretivist paradigm.70 Interpretivists follow a subjectivist epistemology which accepts that researchers cannot separate themselves from what they know and study. The research involved triangulation of the knowledge gained from the semi-structured interviews, an extensive literature review, and the interpretation of the case studies. An interpretive approach relies on naturalistic methods, which include interviewing and the analysis of existing texts.71 McMillan and Schumacher72 indicate that such a design focuses on the phenomenon that the researcher wishes to understand, regardless of the number of sites, participants, or documents involved in the study. According to Henning,73 phenomenology implies that participants sketch their experiences in their own words by means of reflective interviews. An interview schedule was used during the semi-structured interviews to allow the participants to sketch their experiences. This schedule focused in particular on the experiences and involvement of evidence leaders in disciplinary hearings and the fairness of the disciplinary process.

8.2 Sampling

Data was collected from participants who had been purposefully selected by the researchers. Purposeful sampling gave the researchers the opportunity to hand-pick the participants relevant for this research, in order to develop a sample large enough to contain all the required traits and knowledge of evidence leaders.74 Stratified and criterion sampling was used and predetermined participants who had the required characteristics and experiences as evidence leaders were sampled.75 Those chosen to participate were those who were involved in learner disciplinary hearings and who had relevant experience as evidence leaders in the disciplinary system of a school.

The knowledge generated in this research was gained from twelve participants who acted as evidence leaders in eight secondary schools, which included public and independent schools. Qualitative research is characterised by relatively small groups of participants.76 The research area covered two education districts in the Gauteng Province. Five of the schools were ordinary secondary public city schools and two were independent schools. One school was a school for learners with special educational needs (LSEN) in a township. Two of the schools were major independent schools in the Gauteng Province. The reason for including the two independent schools was to be able to compare the experiences of evidence leaders in the two different domains of secondary teaching in South Africa, to give more definition to the evidence leader role. It was important to get a range of views on the research topic, as these interviewees produced "radically different" or "contrasting views" which played a central part in modifying the theories identified.77

Ethical clearance had to be obtained from the University of Pretoria, the Department of Basic Education, and both districts prior to the start of the interviews. The participants voluntarily engaged in face-to-face, semi-structured interviews.78 The letter of invitation stated that participation was voluntary and this fact was repeated at the start of each interview.

8.3 Data collection

We collected data for this qualitative research via semi-structured face-to-face interviews with participants who acted as evidence leaders, and from an elaborated literature review. Interviews are by nature social encounters between interviewers and interviewees and aim to produce versions of the interviewees' past (or future) actions, experiences, feelings and thoughts. It was observed by the researchers and noted in the field notes with what ease the participants shared their experiences towards the end of the interview. These face-to-face interviews enabled the researchers to gain better insight into the research topic and the lived experiences of the people with experience as evidence leaders. A voice recorder was used to record the data collected so as to make it easier for the data to be transcribed, and to assist the researchers during data analysis and clarification. Field notes provided the researchers with the opportunity to gain a clear view of their thoughts, and also assisted in planning the next step in the process of data collection, known as prefiguring.79

The researchers also studied relevant cases such as Le Roux v Dey 2011 3 SA 274 (CC) and De Kock v Head of Department of the Department of Education, Province of the Western Cape (CPD) unreported case number 12533/98 of 2 October 1998.

A fourth method of data collection included the studying of charge sheets, the minutes of disciplinary hearing cases, transcriptions of voice recordings, recommendation letters and appeal letters held by the schools participating in this research.80 The document analysis was an attempt to substantiate the findings made during the interviews.

8.4 Analysis and interpretation

After the completion of the data collection process, the researchers immersed themselves in the data and familiarised themselves with the information in order to perform a discourse analysis,81 which involves studying the patterns within the data (ways of talking and behaving) within the broader context in which the text functions.82 The aim of discourse analysis is to discover patterns of communication that have functional relevance for the research.83 Then the researchers took all the collected data, including the field notes, the document analysis and the interview transcripts to triangulate the data and shape a clear understanding of the information. The researchers made use of a case study design and focused on conducting content analysis by identifying patterns to rationalise the role and practice of evidence leaders.84 The documents fleshed out the details of the disciplinary processes and hearings and led to a better understanding of the role and practice of the evidence leaders.85

The content analysis then performed was an inductive and iterative process where the researchers looked for similarities and differences in the text that would corroborate or disconfirm their theories.86 The researchers' content analysis entailed the initial preparation of the data by organising the raw data (the transcribed interviews and audio material) via the ATLAS.ti version 7.5.7 qualitative data analysis software programme. Secondly, it involved coding all the raw data, or identifying where it was originally obtained.87 The next step was to copy the textual data and store it safely. The researchers made use of inductive coding, which allowed them to examine the data directly and to allow the codes to emerge from the data and to be compared to the code emerging from other data. 88 This method of coding supports the constructivist theory, which involves coding only what the participant said. It also supports the grounded theory, which involves coding the textual data line by line. Constructivism adheres to a realist position that assumes multiple and equally valid realities.89

The coding units were generated using the ATLAS.ti software programme and included words or segments of each sentence. After the coding process the researchers grouped the coded data into themes and theme clusters, after which they identified patterns from the coded data. In this process of data analysis the method of crystallisation supported the researchers in generating meaningful data. The process of examining and reading the data (immersion) was temporarily postponed in order to reflect on the analysis experience and to attempt to identify and articulate patterns evident during the immersion process.90 The data codes were descriptive summaries of the information the participants had provided. This process was continued until all of the data had been examined and patterns had emerged that were meaningful and could be verified.91

9 Preliminary findings

This paper reports on the preliminary findings as interpreted by the researchers.

9.1 Disciplinary hearings as mechanisms to manage learner discipline

There is an enormous difference between the disciplinary system prior to 1994 and post the "apartheid" era. Participant B stated that in the time prior to 1994 discipline was punitive and learners were afraid to be disciplined, and there was also a great deal of injustice during this era. Discipline was managed internally and was largely one-sided. The disciplinary hearing was a post-1994 method of managing discipline in a manner that is democratic and fair, allowing learners the opportunity to learn from their wrongdoing. This allowed all of the stakeholders of the school to view the case objectively.

All the participants concurred that the aim of the disciplinary hearing is to act in the best interest of the learners and to correct their behaviour.

Participant D said that every disciplinary hearing is different and should be managed as a unique case. People react differently even in regard to the same charge or transgression. It is expected that every learner's case should be viewed objectively and that every learner should have a fair opportunity to state his/her side of the story. This implies that all facts, evidence and witnesses should be investigated in detail by the disciplinary committee before they sanction the learner.

Participant A maintained that a successful and educational disciplinary system means that learners learn to take responsibility for their actions, and that it involves all stakeholders - parents, teachers, as well as evidence leaders and disciplinary committees - in the decision-making process. The majority of the participants believed that the disciplinary hearing should give the parent and the learner the opportunity to ask questions and to understand the disciplinary process, the charge, and the sanction given, as well as the policies involved. The disciplinary hearing should allow all parties involved to walk out of the disciplinary hearing convinced that justice had been done fairly.

Participants C and D were concerned about the limited time disciplinary committees have to make a fair judgement after all the evidence has been presented and all the witnesses have been heard. The policy guiding disciplinary hearing procedures, Circular 74, requires a break be taken after all the evidence has been presented, before the disciplinary committee delivers its sanction.92 During this period the disciplinary committee has the opportunity to discuss and reflect on all facts and evidence presented, which supports a fair process. Some of the participants indicated that they do not deliver their sanction on the same day, in order to give the disciplinary committee ample opportunity to digest the case. The majority of the participants, though, noted that their disciplinary committee managed disciplinary hearings in such a manner that sanction was given on the same day of the hearing. The choice of process depended on the school governing body's attending as the disciplinary committee, and what its notion of a fair hearing was.

9.2 Role of the evidence leader

All the participants identified the evidence leader as the prosecutor during the disciplinary hearing, and as the representative of the school. The evidence leader's tasks included the initial investigation and collection of relevant evidence or artefacts in support of the case to be presented before the disciplinary committee. This was unanimously described by the participants as being challenging, as well as being something they did not really understand. All of the participants expressed feelings of frustration with this.

The evidence leader as prosecutor is to represent the school during the disciplinary hearing and to present the facts of the case. According to participant A it is not expected of the evidence leader to be a "hanging judge", but to present all of the evidence objectively. It is one of the main priorities of the evidence leader to describe the case through this presentation in such a manner that the disciplinary committee may discuss it and, where the learner if found guilty, to decide on a sanction that is fair and is applicable to the transgression.

Participant D emphasised that the aim of the evidence leader is to act in the best interests of the learner, the school and the community. According to participants B, C and D it is important that the evidence leader accumulate the facts of the case correctly and factually, to prevent the fabrication of evidence and facts. This has a direct impact on the fairness of the process and hearing. It is the biggest challenge to present the case to the disciplinary committee in such a manner that it is objective and correct. The disciplinary committee is an unbiased and objective panel who have no prior knowledge of the case presented by the evidence leader.93 The disciplinary committee and parents should have a clear picture of what happened on the day of the incident.

Most of the participants identified the evidence leader as the first person who hears about the incident and keeps track of the sequence of events. The whole case from the moment of the incident up to the point when the charge is laid is the responsibility the evidence leader. According to participants I and J one key characteristic of this role is communication between the evidence leader and the disciplinary committee, as well as the parents. The methods of communication are telephone calls from day one of the incident, as well as a letter explaining the process and the charges against the learner. Any inconsistency in this process, the charge sheet, facts or evidence will influence the fairness of the process of the disciplinary hearing as stipulated in the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act.94

Participant A made a comment about the evidence leader's role as "fancy footwork" when presenting the case before the disciplinary committee and parents. It was important to this participant that the evidence leader should have insight into what the reason for the incident was, almost like a sixth sense. This is necessary when presenting a case where there is an aggressor and a victim, as in the classic break-time fight. The evidence leader needs to act in the best interests of both learners, due to the possibility of there being mitigating or aggravating circumstances. According to participant A, this is a skill that is developed through years of experience of managing disciplinary hearings. According to this participant, it is essential for the evidence leader to be a teacher at heart, to separate the transgression from the learner, because he/she works with the children. It is only then that the disciplinary hearing will be corrective and restorative.

9.3 Managing a fair disciplinary process and disciplinary hearing

All participants noted that the whole disciplinary process, from the moment of the incident until the point of sanctioning or acquittal, should be fair and should not unfairly discriminate against any learner. The evidence leader is obliged to stay objective at all stages of the process. According to the majority of the participants the most important factor is to give the learner ample opportunity to talk and to defend his/her case.

The disciplinary committee was characterised by the participants as an unprejudiced committee which requests as much information as possible about a case before making a decision. It was advisable that the disciplinary committee should include one member with a law background who would give legal guidance to the other members of the committee. It was also advisable that one member should be a parent with no law background, because this person would bring a balance between "law enforcement" and acting in the best interests of the learner. This would bring a balance when the disciplinary committee explained its decision in terms of the applicable policies and laws and what was in the best interests of the learner.

The following essential factors were identified by the participants as enhancing the fairness of disciplinary hearings:

1. In preparation for the disciplinary hearing, the evidence leader should gather the witnesses and make sure that they give the correct version of the incident.

2. Some schools make use of camera systems to record video footage of incidents. The footage is presented as evidence during a disciplinary hearing.

There was agreement that the function of the evidence leader was to ensure that the hearing was fair and based on a true reflection of what happened. The disciplinary hearing should be focused on the learner and the transgression performed by the learner, and should take action to correct it.

9.4 Training and knowledge of the evidence leader

The majority of the participants reported that they had not been trained to act as evidence leaders. All the participants indicated that they gained knowledge regarding the role through years of experience. Some of the participants indicated that they had completed modules on classroom management and general education law as part of their tertiary qualification. Militello, Schimmel and Eberwein,95 as well as Mirabile,96reiterate the lack of consistent training in education law for teachers.

The majority of the participants pointed out that the role of the evidence leader is challenging, he/she has to manage the entire disciplinary process, including the setting of the disciplinary hearing date and arranging for the disciplinary committee members to attend. Participant J said that as an ordinary teacher she found it difficult to understand some of the legal terms used during a disciplinary hearing. Participants A and C said they felt sorry for the person who would be taking over the role as evidence leader from them. They made it clear that they had nobody who had helped them to shape their role as evidence leader. Everything they knew had been gained through many years of trial and error. All the participants reiterated the importance of being trained as evidence leaders, due to the complexity and specialisation of the role. It was important to them that the role be satisfactorily performed, because the future of a learner was at risk, the reputation of the school and that of the evidence leader is in the limelight, and the public perception of the school's disciplinary system could be compromised.

Most of the participants said that the support they received from their local Education District Offices took the form of notices or information communicated after principals' meetings. This was frustrating to them due to their not understanding the instructions in the notices or not receiving the instructions first hand. Most of the information was focused on the different types of transgressions or steps to follow in the disciplinary process. There was very little advice on how to increase fairness or on what due process means. They all indicated that they needed more relevant information regarding changes in disciplinary policies, how to prepare witnesses, and what to do when a lawyer attended a disciplinary hearing. Three of the participants indicated that they knew of a private company, African Management Consultants International,97which presents seminars on essential skills for role players in education disciplinary tribunals, but said that it was very expensive to attend. The dilemma was that many of these educators only learn about a fair disciplinary process and the role of an evidence leader when presenting a case in a disciplinary hearing. The participants made it clear that there are still enormous gaps between the training of evidence leaders and what they experience.

9.5 Policy guiding the discipline process

The participants thought that the policies and laws regulating the disciplinary system have some of the characteristics of a court of law. There were mixed reactions from the participants to this resemblance. Some said that the disciplinary hearing was too rigid and impersonal, and very intimidating to learners, parents and evidence leaders. Other participants complimented the policies guiding the disciplinary hearing, because the policies provided the disciplinary hearing with structure and a sense of authority. Beckmann and Prinsloo98 indicate that there is a lack of policy related to disciplinary hearings or that it is poorly formulated and badly implemented schools.

All of the participants admitted that the policies and laws, for example SASA, are of the utmost importance to guiding the actions of the evidence leader and disciplinary committee in order that the hearing should be fair and just. The evidence leader and disciplinary committee are empowered in terms of law and policies like the National Education Policy Act 27 of 1996 (NEPA), the SASA, the PAM and the school's Code of Conduct. Principals and educators have original and delegated authority to discipline and punish learners, as confirmed in the case of Van Biljon v Crawford99and R v Muller.100It is original authority in terms of their status as educators and delegated authority in terms of their position in loco parentis namely to take action when necessary The educator has the right to act like a reasonable parent when supervising, disciplining and punishing learners.101

According to Cameron102 the Constitution and policies regarding discipline are "over-lawyerised, over-proceduralised and over-legalised" and have to be a "re-calibrated" to improve efficiency and fairness. It is disconcerting to the participants that the policy documents do not support them in the detail of how they should perform their roles in disciplinary hearings. The participants were concerned that the policies regarding the disciplinary hearing prescribed the flow of proceedings but could not predict or indicate the manner in which people react during the proceedings. Some participants indicated that parents might have the urge to vent their spleen or challenge the disciplinary committee, because they wanted to protect their children. It is the human factor that the policy documents struggle to describe, such as the aggravating or psychological factors influencing the case.

9.6 Challenges experienced by the evidence leader

The majority of the participants were ordinary teachers with teaching qualifications, who applied their professional skills, attitudes and knowledge to manage school discipline. The first challenge communicated and identified by all participants was that they had not been trained or were not qualified for their roles as evidence leaders. The role of an evidence leader is very challenging and detailed, taking into consideration due process and the requirement of fairness in all of the actions taken by the evidence leader. Another challenge expressed uniformly by the participants was the excessive amount of paper work to be done and the number of laws to take note of when executing this role. Much time was spent on the preparation and analysis of documents which were essential during the disciplinary hearing. It was overwhelming for the evidence leader in times when more than one disciplinary hearing was scheduled at a time. It was under these circumstances that administrative and procedural mistakes were made by the evidence leader, which might influence the fairness of the process.

According to the participants the idea of having disciplinary hearings to manage learner discipline is relatively new. In the past, teachers and principals "took the law into their own hands". Participant A emphasised that some teachers were afraid to discipline learners. Participants A, B, D and I noted that the disciplinary hearing could create the idea that discipline was the responsibility of the evidence leader alone. These participants said that since the inception of the disciplinary hearing system, many teachers did not want to get involved in general classroom discipline. These teachers used the role of the evidence leader and disciplinary hearings as an escape route and passed their problems on to the evidence leader to sort things out. The teacher would stand back and shift all responsibility to the evidence leader. This was a cause of great concern for the evidence leader due to the overload of cases to investigate as well as the amount of time spent on paperwork. According to participant D the disciplinary hearing was not intended to manage classroom discipline and entertain apathetic teachers. According to all the participants, the main goal of a disciplinary hearing was to manage serious cases that could lead to suspension or expulsion.

The use of witnesses during a disciplinary hearing is another challenge. Some of the participants indicated that there is often a discrepancy between what the witness report on the day of the incident and what they state during the disciplinary hearing. They said that witnesses tended to stay away on the day of the disciplinary hearing, or did not want to attend the disciplinary hearing from the start. In these cases the witnesses want to protect their identity, because they are afraid of what will happen after the disciplinary hearing. Some have no transport. Some participants indicated that the learner might initially indicate that he/she is guilty, but turn around during the disciplinary hearing and plead not guilty. It is a great challenge for the evidence leaders to give an objective view of what happened on the day of the incident. This has a direct effect on the presentation of the charge against the accused learner and the disciplinary hearing may conclude with no result. This is of great concern in cases where the learner has been charged with an offence concerning the use of illegal drugs, assault, or being in possession of weapons on school premises.

The majority of the participants identified the charge sheet as an administrative challenge. Most of them struggle with the wording and to identify the policy or law applicable in the case. These participants mentioned that a number of disciplinary hearings finished indecisively due to complications related to the charge sheet. All of the participants knew that the charge sheet has to be communicated and handed over to the learner and parents at least five days prior to the hearing.103

The participants indicated that the parents are over-protective of their children and get emotionally involved in the proceedings of the disciplinary hearing. These parents impulsively challenge the evidence leader, the disciplinary committee, the witnesses or the disciplinary process to protect the dignity of their children. It is under these circumstances that parents make use of a lawyer or counsel to defend the case. According to the participants most lawyers want the disciplinary hearing to proceed as a court of law and not as a tribunal, where parents and the school governing body gather to discuss the charge at hand. The lawyer sometimes does not understand that the goal of the disciplinary hearing as a tribunal with quasi-judicial elements is to give the disciplinary committee a fair opportunity to view the case and to act in the best interest of the learner and the school.104 The purpose of the disciplinary hearing is the correction of the learner's actions and the restoration of the learner, rather than to judge him/her. The participants who had had the experience of facing lawyers said that they had asked questions outside the experience and qualifications of the evidence leader, leaving the evidence leader dumbstruck. Neither the evidence leader nor the parents are qualified in law, a fact which causes considerable confusion and frustration, in particular when the lawyers make use of Latin terminology during a disciplinary hearing. The majority of the participants expressed their feelings of incompetence and frustration when a lawyer is called to represent the learner.

The participants emphasised that the disciplinary hearings are procedurally very complex and detailed, which makes them time consuming. Participants C and D indicated that their disciplinary hearings might proceed for five to six hours. Most of the learners' disciplinary hearings are scheduled during the school week after five o' clock in the evening, when parents return from work. The participants said that the time and duration of the disciplinary hearings had a definite effect on the learner, who need to attend school the next day, not to mention the evidence leader, who also needed to teach. They indicated that it was counter-productive to schedule disciplinary hearings during school hours, because that is not in the best interests of the learner's education or the school. One participant indicated that the disciplinary hearings in her school are scheduled over two to three nights, with a time limit of four hours per session. Some of the participants mentioned that the disciplinary committee consisted of professional people, who were not paid to attend these hearings. They felt that it was important that neither the evidence leader, nor the parents nor any witness waste their time.

There were some learners who showed no respect for the disciplinary process or the disciplinary hearing. Participant G said that "suspension doesn't scare our learners". The five-day suspension "looks like a holiday to them" (participant H). This was extremely upsetting to hear, because the purpose of the evidence leader and the disciplinary hearing is to support the learners to correct their behaviour.

Another challenge concerned parents who decided to transfer the learner to another school before the date of the disciplinary hearing, to prevent the learner from having a bad record. In these cases, justice is not done and the learner does not face the consequences of his/her transgression. Participants I and J said that it is likely that the transgression will re-occur in the receiving school. It is imperative that the evidence leader should communicate with the receiving school regarding the transgressions made by the learner, to have continuity in the development of the learner and to see that justice is done.105

Participants B and C noted that the role of the evidence leader is determined closely by what the school governing body as the disciplinary committee expects from the process and hearing. Every three years the composition of this committee will change with the election of the new school governing body. These participants were of the opinion that the newly-elected school governing body as the disciplinary committee could consist of a majority of members qualified in law, which would most likely manage the process and disciplinary hearings like a court of law. They also said that there were times when members of the disciplinary committee had no law background and managed the process and disciplinary hearings as a tribunal the purpose of which was to discuss the case fairly and discover the truth. These participants maintained that both of the very different disciplinary committee scenarios are effective and functional, as long as there is due process and the disciplinary hearing is fair. They indicated that the challenge for the evidence leader is to anticipate how the new disciplinary committee will manage this process. They said that the character and method of handling the disciplinary hearing was completely reliant on the disciplinary committee. Participant C emphasised the importance of the evidence leader's meeting with the newly-elected disciplinary committee to agree on how the disciplinary hearings are to be carried out, since the evidence leader will otherwise experience a great deal of frustration when presenting these cases to disciplinary hearings.

9.7 Impact of a disciplinary hearing on learner behaviour

According to the participants, a disciplinary hearing conveys the message that disciplinary issues are being dealt with and that there is accountability for transgressions on school premises. Participant A stated that the disciplinary hearing is the democratically acceptable equivalent of the "rod" used in the era prior to 1994. It was not the intent of the disciplinary hearing to create fear among learners in disciplining them or in managing discipline at the school. This participant said that learners who attended a disciplinary hearing would communicate with others in the school and warn them to be more careful and abide by the school's Code of Conduct. Some participants stated that they had the practice of communicating the sanction to the school after disciplinary hearings. This normally gave teachers more authority in the classroom when managing discipline in the classroom.

Disciplinary hearings should have a "wow value", as one participant put it, because the parents of the learner as well as the school and community expect a sanction that is fair. This participant noted that the disciplinary process that builds up to a disciplinary hearing with sanctioning shows that the management of discipline is a priority in the school. This sends out a warning to the learners in general to abide by the code of conduct, and communicates the message that the disciplinary process is functional. The participants are of opinion that the disciplinary hearing emphasises that a school should be a safe place for a learner and to develop in.

Most of the participants shared their view of the educational value of the disciplinary hearing. Participant J said that the disciplinary hearing should support the parents to find out what the truth is and to hear both sides of the story. Others were of the opinion that the disciplinary hearing is overshadowed and at times overruled by the letter of the law. The educational value of the disciplinary hearing was restricted by the pre-determined policies and corresponding sanctions, which restrict the learner in correcting his/her transgression. These participants wanted the disciplinary committee to have more powers to impose sanctions, so that the learner has a second chance, but also so that justice is seen to be done. The challenge of the disciplinary hearing was to strike a balance between the sanction to address the misconduct and the educational value of the sanction, because the transgressor is a developing child. The majority of the participants emphasised that in most cases aggravating circumstances or related family matters caused the learner to transgress. The transgression was due to a chain of events that caused the behaviour of the learner. It was important to these participants that the evidence leader has to prove guilt according to the balance of probabilities and not beyond all reasonable doubt, as is expected in criminal cases.

10 Conclusion

Learner behaviour problems have been a major concern to teachers, administrators and parents for years. More than ever before, teachers are faced with critical problems in their classrooms, and are confronted (on a daily basis) with unacceptable learner behaviour and threatening situations. After the abolition of corporal punishment and control, an urgent need arose to deal with behavioural issues in innovative ways. The new approach to positive behavioural support, namely disciplinary hearings, represents a shift from a focus on deficit and control towards a developmental and restorative approach.106 This approach is embodied in the Constitution,107SASA108 and the specific outcomes of the National Curriculum Statement, which give priority to the concept of responsibility.109 According to Rossouw,110 there is an overemphasis on the human rights of learners that is complicating the management of discipline in public schools. There is also a concern about independent schools who do not abide by education statutes, especially those that are concerned with discipline.111

In the 20 years of democracy much has changed in the manner in which learners are disciplined. The disciplinary system is transparent now, and involves all stakeholders in the discipline and development of learners. There is an emphasis on communication and cooperation between schools and parents. The participants in this research project seemed to believe that democracy in South African schools has not yet reached its full potential. The manner in which evidence leaders and disciplinary committees manage fair disciplinary processes and disciplinary hearings could support our education system to democratically discipline our learners to become responsible citizens. Learners need to know what they have done and to take responsibility for their actions and decisions.112

The parents of a school and the community want a school where there is discipline, order and justice. The role of the evidence leader and the function of the disciplinary hearing build the confidence of the parent community regarding their children's safety and education. A disciplinary hearing can send out a message that the management of the school regards the education and democratic and fair development of learners as its main priority. The evidence leader and teachers have a responsibility to support and guide the learner after sanctioning, to prevent the learner from transgressing again. This is the restorative and educational value of the disciplinary process and hearing, when the development of the learner is the pivot of school discipline. The participants understandably believe that that the Department of Basic Education should become more hands-on and accessible concerning school-related disciplinary matters. This research focuses on the evidence leader in the very unique role of managing due process and ensuring fairness when disciplining learners. The effective management of a disciplinary process that is fair and just will succeed when the Department of Basic Education places a priority on the development and training of evidence leaders. In collaboration with the Department of Basic Education the school governing body and principals of schools should employ evidence leaders with a law qualification, in particular education law, or urgently get their evidence leaders trained and qualified in law.

All the participants were intrigued by this research topic and requested that the researchers form discussion groups when the research has been completed. They have a hunger to know more and to associate with the experiences of other evidence leaders. It is the professionalism of these evidence leaders and their ambition to learn that impressed us most. They all want to improve as evidence leaders, as well as to protect the dignity of the learner and that of the school. Most importantly, they feel learners need to have respect for the hierarchy of the school management and the disciplinary process. 113 It is not a fear associated with corporal punishment, but concerns respecting those with authority, namely teachers and the evidence leader.114

While the formal introduction of factors such as due process, administrative justice and the rules of natural justice into learner discipline is welcomed, it is of concern that educators and other role players who are not trained in law are expected to carry out vital quasi-judicial functions without proper support and training. This weakness jeopardises the integrity of the process and the dignity of some role players.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Literature

African Management Consultants International "Essential Skills for Role Players in Education Disciplinary Tribunals" Seminar material for a seminar (13-15 February 2013 Johannesburg) [ Links ]

Aspen DN Creating and Managing the Democratic School (Falmer Press London 1994) [ Links ]

Beckmann JL and Prinsloo J "Training Teachers to Play Quasi-judicial Roles in Learner Discipline: The Story of an Intervention to Close the Justice Gap" Paper delivered at the International Symposium on Education Reform (ISER) (10-18 June 2013 Jyväskylä and Helsinki Finland) 27-47 [ Links ]

Black TR Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistic (Sage London 1999) [ Links ]

Burns Y Administrative Law under the 1996 Constitution (Butterworths Durban 1998) [ Links ]

Cameron E 2014 "Claiming Back the School: A Constitutional Perspective on Discipline in Schools" Paper read at a SAOU (Suid-Afrikaanse Onderwysersunie) Conference on Discipline and Violence in Schools (26 July 2014 Pretoria) [ Links ]

Coolican H Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology 3rd ed (Hodder and Stroughton London 1999) [ Links ]

Gauteng Department of Education Circular 74: Managing of Suspension and Expulsion of Learners in Public Ordinary School (The Department Pretoria 2007) [ Links ]

Henning E Finding Your Way in Qualitative Research (Van Schaik Pretoria 2004) [ Links ]

Hopkins K "Some Thoughts on the Constitutionality of 'Independent' Tribunals Established by the State" 2006 Obiter 150-155 [ Links ]

Joubert R Learner Discipline in Schools (CELP Pretoria 2008) [ Links ]

Joubert R, De Waal E and Rossouw JP "Discipline: Impact on Access to Equal Educational Opportunities" 2004 Perspectives in Education 77-87 [ Links ]

Malan K "Geregtigheid, Billikheid en Demokrasie: 'n Oorweging van Onderskeidinge en Onderliggende Beginsels" 2005 SA Public Law 68-85 [ Links ]

Maree K First Steps in Research (Van Schaik Pretoria 2011) [ Links ]

Mashile A "School Governance Capacity Building for Transformation" in De Groof J et al (eds) Governance of Educational Institutions in South Africa: Into the New Millennium (Mys and Breesch Ghent 2000) 80- 82 [ Links ]

McMillan JH and Schumacher S Research in Education: A Conceptual Introduction (Longman New York 1997) [ Links ]

Merriam SB Qualitative Research! and Case Study Applications in Education (Jossey Bass San Francisco 1998) [ Links ]

Militello M, Schimmel D and Eberwein HJ "If They Knew, They Would Change: How Legal Knowledge Impacts Principal's Practice" 2009 National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin 27-52 [ Links ]

Mirabile C A Comparison of Legal Literacy among Teacher Subgroups (PhD-thesis Virginia Commonwealth University 2013) [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis J Qualitative Research: Support Session for M Ed and PhD Students (University of Pretoria, Groenkloof Campus Pretoria 2014) [ Links ]

Patton M Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (Sage Thousand Oaks CA 1990) [ Links ]

Roos R "The Legal Nature of Schools, Codes of Conducts and Disciplinary Proceedings in Schools" 2003 Koers 499-520 [ Links ]

Rossouw JP "Learner Discipline in South African Public Schools: A Qualitative Study" 2003 Koers 413-435 [ Links ]

Schwandt TA "Constructivist, Interpretivist Approach to Human Inquiry" in Denzin NK and Lincoln YS (reds) Handbook of Qualitative Research (Sage Thousand Oaks CA 1994) 118-137 [ Links ]

Seale C et al Qualitative Research Practice (Sage Thousand Oaks CA 2004) [ Links ]

Squelch JM Discipline (CELP Pretoria 2000) [ Links ]

Struwig FW and Stead GB Planning, Designing and Reporting Research (Pearson Cape Town 2007) [ Links ]

Van Staden J and Alston K "School Governance: Keeping the School out of Court by Ensuring Legally Defensible Discipline" in De Groof J et al (eds) Governance of Educational Institutions in South Africa: Into the New Millennium (Mys and Breesch Ghent 2000) 110-117 [ Links ]

Watkins K and Cervero R "Organizations as Contexts for Learning: A Case Study in Certified Public Accountancy" 2000 Journal of Workplace Learning 187-194 [ Links ]

Western Cape Education Department Learner Discipline and School Management: A Practical Guide to Understand and Managing Learner Behaviour within School Context (Education Management and Development Centre Metropole North 2007) [ Links ]

Wimmer R and Dominick J Mass Media Research: An Introduction (Wadsworth Belmont 2000) [ Links ]

Yin RK Case Study Research Design and Methods 4th ed (Sage Thousand Oaks 2009) [ Links ]

Case law

Le Roux v Dey 2011 3 SA 274 (CC)

De Kock v Head of Department of the Department of Education, Province of the Western Cape (CPD) unreported case number 12533/98 of 2 October 1998

R v Muller 1948 4 SA 848 (O)

Van Biljon v Crawford (SECLD) unreported case number 475/2007 of 13 March 2008

Legislation

Constitutional of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 Employment of Educators Act 76 of 1998 National Education Policy Act 27 of 1996 Promotion of Administrative Justice Act 3 of 2000 South African Schools Act 84 of 1996

Government publications

Gen N 776 in GG 18900 of 15 May 1998 (Guidelines for the Consideration of Governing Bodies in Adopting a Code of Conduct for Learners)

GN 222 in GG 19767 of 18 February 1999 (Personnel Administrative Measures) Gen N 6903 in Gauteng PG 144 of 4 October 2000 as amended by Gen N 2591 in PG 72 of 9 May 2001 (Regulations for Misconduct of Learners at Public Schools and Disciplinary Proceedings)

Internet sources

Cohen D and Crabtree B 2006 Qualitative Research Guidelines Project http://qualres.org/HomeGuid-3868.html accessed 9 July 2014 [ Links ]

Education Labour Relations Council 2009 Teacher Development Summit http://www.sace.org.za/upload/files/TDS%20Declaration.pdf accessed 28 March 2014 [ Links ]

Unisa Institutional Repository 2012 Department of Educational Leadership and Management http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/6421 accessed 18 June 2014 [ Links ]

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AMCI African Management Consultants International

EEA Employment of Educators Act 76 of 1998

ELRC Education Labour Relations Council

JJS Journal for Juridical Science

LSEN Learners with Special Educational Needs

NASSP Bulletin National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin

NEPA National Education Policy Act 27 of 1996

NRF National Research Foundation

PAM Personnel Administrative Measures

SASA South African Schools Act 84 of 1996

SMTs School Management Teams

UIR Unisa Institutional Repository

WCED Western Cape Education Department

As NRF Incentive Funding grant holders the authors acknowledge that the opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations of this article are those of the authors and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard

1 Rossouw 2003 Koers 416.

2 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 28.

3 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 30.

4 Personnel Administrative Measures (PAM).

5 Sections 8 and 9 of the South Afrccan Schools Act 84 of 1996 (hereafter SASA).

6 Sections 8 and 9 of SASA.

7 Employment of Educators Act 76 of 1998 (hereafter EEA).

8 Militello, Schimmel and Eberwein 2009 NASSP Bulletin 29.

9 Mashile "School Governance Capacity Building" 81.

10 Gen N 776 in GG 18900 of 15 May 1998.

11 Section 8(5) of SASA.

12 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 28.

13 GN 222 in GG 19767 of 18 February 1999.

14 Sections 8 and 9 of SASA.

15 Section 33 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution).

16 GN 222 in GG 19767 of 18 February 1999.

17 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 33; Joubert Learner Discipline 48.

18 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 33.

19 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 33; Hopkins 2006 Obiter 150.

20 Gen N 6903 in Gauteng PG 144 of 4 October 2000 as amended by Gen N 2591 in PG 72 of 9 May 2001.

21 Joubert Learner Discipline 46.

22 WCED Learner Discipline 22; Joubert Learner Discipline 49.

23 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

24 South African Schools Act 84 of 1996.

25 Joubert Learner Discipline 48.

26 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 28; Hopkins 2006 Obiter 150.

27 Section 12(1) of the Constitution.

28 Section 12 of the Constitution.

29 Gauteng Department of Education Circular 74 4.

30 Section 8(5) of SASA.

31 Section 9 of SASA.

32 Section 33 of the Constitution; Roos 2003 Koers 517.

33 Squelch Discipline 119.

34 Burns Administrative Law 130.

35 Joubert Learner Discipline 48-50.

36 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 32.

37 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 32.

38 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 32.

39 Joubert Learner Discipline 78.

40 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

41 South African Schooss Act 84 of 1996.

42 Ch 2 of the Constitution.

43 Section 33 of the Constitution.

44 Section 8(5) of SASA.

45 AMCI "Essential Skills".

46 AMCI "Essential Skills".

47 Joubert, de Waal and Rossouw 2004 Perspectives in Education 86.

48 Van Staden and Alston School Governance 110.

49 Van Staden and Alston School Governance 110.

50 Joubert Learner Discipline 11.

51 Malan 2005 SA Pubic Law 84.

52 AMCI "Essential Skills".

53 ELRC 2009 http://www.sace.org.za/upload/files/TDS%20Declaration.pdf.

54 Aspen Creating and Managing the Democratic School 85.

55 Le Roux v Dey 2011 3 SA 274 (CC).

56 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 35-36.

57 Mashile "School Governance Capacity Building" 3; ELRC 2009 http://www.sace.org.za/upload/files/TDS%20Declaration.pdf.

58 Watkins and Cervero 2000 Journal of Workplace Learning 188.

59 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 40-41.

61 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 42.

62 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 29.

63 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers" 35.

64 Yin Case Study Research Design 18.

65 Yin Case Study Research Design 3-4.

66 Wimmer and Dominick Mass Media Research 60.

67 Yin Case Study Research Design 6.

68 Coolican Research Methods 450-451.

69 Merriam Quaiitative Research 63.

70 Maree First Steps in Research 47.

71 UIR 2012 http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/6421.

72 McMillan and Schumacher Research nn Education.

73 Henning Finding Your Way 67.

74 Black Doing Quantitative Research 68.

75 Patton Qualitative Evaluation 185.

76 Patton Qualitative Evaluation 185.

77 Sea le et al Qualitative Research Practice 78.

78 Maree First Steps in Research 295.

79 Nieuwenhuis Quaiitative Research 74.

80 Maree First Steps in Research 298.

81 Struwig and Stead Paannnng, Designing and Reporting Research 76.

82 Struwig and Stead Paannnng, Designing and Reporting Research 76.

83 Struwig and Stead Paannnng, Designing and Reporting Research 76.

84 Maree First Steps in Research 298.

85 Sea le et al Qualitative Research Practice 388.

86 Maree First Steps in Research 101.

87 Schwandt "Constructivist, Interpretivist Approach" 119.

88 Maree First Steps in Research 105.

89 Schwandt "Constructivist, Interpretivist Approach" 121.

90 Cohen and Crabtree 2006 http://qualres.org/HomeGuid-3868.html.

91 Cohen and Crabtree 2006 http://qualres.org/HomeGuid-3868.html.

95 Militello, Schimmel and Eberwein 2009 NASSP Bulletin 27.

96 Mirabile Comparison of LegalLtteracy 38.

97 AMCI "Essential Skills".

98 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers".

99 Van Bljon v Crawford(SECLD) unreported case number 475/2007 of 13 March 2008.

100 R v Mul/er 1948 4 SA 860 (O).

101 Joubert Learner Discipline 13.

102 Cameron 2014 "Claiming Back the School".

103 Gauteng Department of Education Circular 74 87.

104 Beckmann and Prinsloo "Training Teachers".

106 Rossouw 2003 Koers 415.

107 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

108 South African Schooss Act 84 of 1996.

109 WCED Learner Discipiine.

110 Rossouw 2003 Koers 415.

111 Roos 2003 Koers 508.

112 Cameron 2014 "Claiming Back the School".

113 Cameron 2014 "Claiming Back the School".

114 Cameron 2014 "Claiming Back the School".