Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.17 no.6 Potchefstroom 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v17i6.11

ARTICLES

The legal implications of the economic realities of artificially manipulating a decrease/increase of earnings per share - if any

CG KilianI; E Snyman-Van DeventerII

IMA (University of Regensburg), LLD (University of the Free State). Former interim researcher at the European Academy and research fellow at the University of the Free State. Email: corneliuskilian@hotmail.com

IILLM (University of the Free State), LLD (University of the Free State). Professor of Law, Head of the Department of Mercantile Law, University of the Free State. Email: snymane@ufs.ac.za

SUMMARY

Although probably oversimplified, calculating "earnings per share" or the "earnings-per-share ratio" entails the activity of dividing the net profit of a company by the number of its issued shares. The economic reality is that companies may use innovation and creativity to lawfully engineer a better earnings-per-share ratio in order to attract more shareholder investments. Neither the Companies Act of 1973 nor that of 2008 makes any provision for the maximum or minimum amount of capital required to float a company, or the minimum number of shares that should be issued. This depends solely on the promoters' discretion of the number of shares that must equal the capital amount. It is therefore possible that the promoters may excessively exercise their discretion when deciding on the authorised share capital, and later tailor-make or financially engineer the share capital structure of the business to make it attractive to shareholders or future shareholders. After all, the law does not prohibit statutory financial engineering. The purpose of this article is therefore to consider section 75 in the Companies Act of 1973 - or its equivalent (section 36(2)) in the Companies Act of 2008 - and the topic of statutory approval for an artificial decrease or increase in the number of issued shares. Possible methods of preventing or limiting artificial increases in earnings per share are also suggested.

Keywords: earnings per share; earnings-per-share ratio; Companies Act; economic reality; financial engineering; share capital structure.

1 Earnings per share: background and introduction

1.1 Background

The topic of earnings per share is certainly not a popular research topic, nor is it regularly encountered in law journals or case-law judgments. It remains a largely unexplored yet intriguing research area, and is known as the most unexamined field in company law. Not surprisingly, therefore, it is sometimes difficult to explain what the concept of earnings per share is. Schedule 4 to the Companies Act of 19731 defines it as follows:

... the earnings attributable to each equity share, based on the consolidated net income for the period, after tax, and after deducting outside shareholders' interest and preference dividends, divided by the weighted average number of that class of share in issue.

The Companies Act of 2008,2 however, provides no definition or suitable explanation of earnings per share.

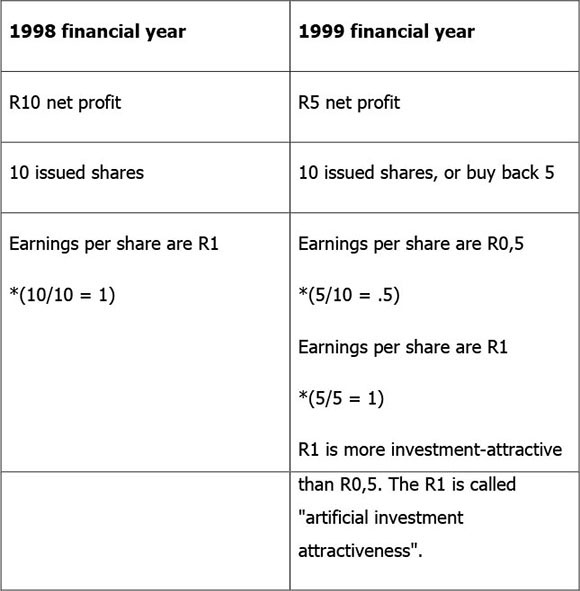

In considering why a listed share has a very high or low price on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE Ltd), earnings per share constitute the economic basis for interpreting such a price. Although probably oversimplified, calculating "earnings per share" or the "earnings-per-share ratio" entails the activity of dividing the net profit of a company by the number of its issued shares.3 There have been many responses to this core explanation. The economic reality is that companies may use innovation and creativity to lawfully engineer a better earnings-per-share ratio in order to attract more shareholder investments.4 Having thus determined that the relevant share price pertains to the number of issued shares, "earnings per share" encapsulates the economic reality that the number of issued shares may decrease artificially through creative engineering. After all, the law does not prohibit statutory financial engineering.

The purpose of this article is to consider section 75 in the South African Companies Act of 1973, or its equivalent (section 36(2)) in the new South African Companies Act of 2008), and the topic of statutory approval for an artificial decrease or increase in the number of issued shares. The economic-reality argument is based on section 85 of the Companies Act of 1973 or its equivalent in Act 2008 (sections 48 refers to section 46(1)c and section 46(1)c refers to section 4 of the Act), which illustrates that section 75 or its equivalent in the Act of 2008 (section 36(2)) is not subject to any liquidity or solvency requirements. In fact, section 75 or its equivalent in the Act of 2008 does not require a reason for limiting or preventing the artificial decrease or increase of the number of shares through financial engineering.

1.2 Introduction

Neither the Companies Act of 1973 nor that of 2008 makes any provision for the maximum or minimum amount of capital required to float a company, or the minimum number of shares that should be issued. This depends solely on the promoters' discretion of the number of shares that must equal the capital amount.5 It is therefore possible that the promoters may excessively exercise their discretion when deciding on the authorised share capital, and later tailor-make or financially engineer the share capital structure of the business to make it attractive to shareholders or future shareholders.6 For example, the earnings per share are calculated by dividing retained profits (net profit) by the number of shares issued.7 Similarly, a shareholder of a listed company could divide the market price per share of a listed company by the earnings per share in order to calculate the investment attractiveness of a listed share, which is known as the "price-to-earnings ratio".8

This article considers possible methods of preventing or limiting artificial increases in earnings per share.9 The word "artificial" in this instance is not meant in the sense of an artificially inflated turnover, but rather to denote the artificial engineering of the number of issued shares to increase the earnings-per-share ratio, without an actual increase in the company's turnover or in the net profits through normal business operations. The word "artificial" should therefore be understood in the context of clever financial engineering of the number of shares issued to the shareholders of the company.10 First, however, it is important to consider the capital rule philosophy in South Africa pertaining to section 85 of the 1973 Companies Act as it was amended in Act 37 of 1999, and its significant contribution to the field of the maintenance of share capital in the 2008 Companies Act.

2 The new and old capital rule philosophy in South Africa

2.1 The new philosophy (1999)

Indeed, company law philosophy pertaining to capital rules has expanded rapidly in recent decades, partly due to the growing statutory importance of the new Companies Act 2008, and its economic significance to shareholders. Thus, as the relevant literature that covers the period from 1887 to 1999 is too voluminous to consider exhaustively, this article only briefly focuses on the significant law-orientated contributions in the two separate timeframes of 1887 and 1999. For practical purposes the "new" capital rules introduced in 1999 by the amended section 85 of the 1973 Companies Act are discussed first.

In terms of these rules, the company may acquire its own shares (as a method to decrease the number of issued shares), if the financial ratios in section 85 have been adhered to.11 The ratios as disclosed by section 85 as amended in Act 37 of 1999 are those most widely used in the financial industry to determine the financial position of a company before the company is allowed to acquire its issued shares, particularly the liquidity (cash in hand) and solvency ratios (assets exceed liabilities). The purpose of the "new" capital rules was to benefit the shareholders of the company without any prejudice to the company's creditors should the company decide to acquire its own shares.12 However, it has become increasingly obvious that the acquisition of own shares has quite the opposite, positive effect by influencing the earnings per share directly. This has interesting implications in the light of section 85's requirement for creditor protection through the solvency and liquidity ratios. Before section 85 was amended in Act 37 of 1999, section 85 had no liquidity or solvency ratios as requirements to support or validate a buy-back of company shares.13

Yet there are also certain drawbacks to these ratios as statutory requirements. As the balance statement of a company discloses the financial position of that company only on a specific date,14 an accountant can choose a date to "window-dress" the balance statement favourably so as to comply with the statutory ratios of section 85 as amended in 1999.15 On the other hand, the balance sheet presents only a snapshot of the company's financial affairs on a specific day, and remains relevant until the next financial year-end (a twelve-month period). To neutralise the latter circumstance, one can argue that an auditor should instead disclose the weighted average cost of capital in relation to the internal rate of return in the company's balance sheet. If the internal rate of return is less than the weighted average cost of capital, this would imply that the company is unable to pay its debts as they become due, and should consequently not be allowed to acquire any of its shares.16 Nevertheless, due to the difficulties associated with the correct calculation of an internal rate of return, the 2008 Companies Act has rectified this by introducing a time period of twelve months. In economic terms, the 2008 Act requires not only a solvency and liquidity ratio but also a twelve-month period to support or validate the buy-back of shares. Both the proposed Companies Bill of 200717 and the 2008 Act state as follows in section 4 (as referred to in sections 46 and 48) which is the equivalent of section 85 of the Act of 1999:18

(1) For any purpose of this Act, a company satisfies the solvency and liquidity test at a particular time if, considering all reasonably foreseeable financial circumstances of the company at that time -

(a) the company's total assets equal or exceed its total liabilities; and

(b) it appears that the company will be able to pay its debts as they became due in the course of business for a period of -

(i) 12 months after the date on which the test is considered.19

The time period included in this section has implicitly introduced the relationship between the internal rate of return and the weighted average cost of capital. Even though it is not a requirement to disclose this relationship in any financial statement to determine whether the company will actually be able to comply with the twelvemonth time period, it is at least a continuous requirement up to the next financial year-end. If the internal rate of return is less than the weighted average of the cost of capital, we can assume that the company will not be able to service its debts as they become due - thereby breaching the twelve-month time period.20 If it is able to pay its debts for a period longer than twelve months, this implies true company liquidity.21 On the other hand, the requirements in section 4 or 85 can be avoided by making use of section 75 or its equivalent (section 36(2)) in the 2008 Act. Section 75 or section 36(2) requires no liquidity or solvency ratios nor a twelve-month time period as requirements to support or validate the decrease or increase in the number of issued shares. Due to the latter, the following question is posed: is the decrease or increase of issued shares an intra vires act?

2.2 The old philosophy (1887)

One of the cornerstones of company law is the matter Trevor v Whitworth.22 The Trevor case laid down a very important principle in 1887, although perhaps similar in part to section 48 of the Act of 2008,23 when Lord Herschell stated the common-law principle that a company24 is not allowed to buy-back its own shares unless a buy-back is regulated in its constitution so as to allow for an intra vires act.25 This "old" rule as stated by Lord Herschell required no true liquidity/solvency to legitimise the buy-back of shares. It required only an intra vires act to support or validate any buy back of shares, or else the transaction would be ultra vires and void in the common law.26 Before it was amended in 1999, section 85 did not require an intra vires act to support or validate a buy-back of shares. On the other hand, section 75 required authorisation in the articles of association to decrease or increase the number of issued shares. If no authorisation was provided for in the articles of association, the decrease or increase constituted an ultra vires act. The same intra vires act is not per se a requirement in section 36(2) of the 2008 Act.27 However, neither section 85 before it was amended (and after its amendment) nor section 75 seems to have been adequate in protecting the creditors of a company, since an ultra vires act could be set aside by the company in terms of section 36 of the 1973 Act .28 In the 2008 Act, section 218 (2) simply states that any person who contravenes any provision of the 2008 Act is liable to any other person for any loss suffered, and section 218(1) continues that only a court has the power to declare an ultra vires act void or voidable. Consequently, the following paragraphs consider whether section 85 as was amended or its equivalent in section 4, in economic reality, indeed offers sufficient protection for creditors stemming from any buy-back of shares.29

2.3 The new capital rules introduced in 2008 and the need for a reason as a requirement to legitimise a buy-back of shares

As stated above, the legal aspects of section 85 were not adequate to conclude whether the creditor or the company would be prejudiced due to a buy-back of shares,30 as it was possible for management to "window-dress" the balance sheet.31 Irrespective of an intra vires act, the acquisition or buy-back depended on the balance sheet and whether the liquidity or solvency ratios had been met. Interestingly, the Trevor case32 considered a reason as an ancillary requirement to legitimise the acquisition or buy-back of shares. In that matter, Lord Herschell enquired as follows: "What was the reason which induced the company in the present case to purchase its shares?"33

One such possible reason could be the prevention of a hostile takeover. Hostile takeovers have been covered in depth in law literature. The prevention of a hostile takeover relates more to the proper-purpose doctrine. For example, in the Hogg v Cramphorn case,34 the board of directors issued additional shares in an attempt to avoid a hostile takeover, since the allotment of shares was not subject to any liquidity or solvency ratios. Although the directors believed that the allotment was in the best interest of the company (the creditors of the company were not prejudiced), the court nevertheless held35 that the additional allotment of shares was for an improper purpose.

This judgment concurs with that in the matter Mills v Mills,36 where Chief Justice Latham held that:

... the question that arises is sometimes not a question of the interest of the company at all, but a question of what is fair between the different classes of shareholders ...37

The reason for the latter statement is simply that, in economic reality, directors are also shareholders of a company, whose shares bear a direct relation to their own interests. Thus, if a director is advancing the interest of a company, he or she is also advancing his or her own interest in that company.38 Through additional allotment, the earnings per share will decrease, which makes for an easy argument against the additional allotment of shares. Besides the latter, section 85 or section 48 requires no valid reason for such a buy-back, and whether or not a buy-back contravenes the proper-purpose doctrine falls outside the scope of this article.39 However, it should be noted that any artificial increase in earnings per share to attract possible investors/shareholders should be interpreted as being improper.40 Section 52 of the 2007 Bill also does not prohibit any artificial increase in earnings per share. It states the following:

Shares of a company that have been issued and subsequently re-acquired by that company, must be returned to the same status as shares of the same class that have been authorized but not issued.

And the 2008 Act also does not prohibit any artificial increase in earnings per share. Section 35(5)(a) states:

Shares of a company that have been issued and subsequently acquired by that company, as contemplated in section 48, must have the same status as shares that have been authorized but not issued.

Similarly, section 48(3)(b) (which is equivalent to section 85) also contains the requirement of a plausible reason relating to the status of shares. A company in a relationship with a subsidiary may not purchase those shares if there would be no other shares than convertible or redeemable preference shares in the subsidiary. Section 48(5)(c) requires a genuine reason, and prohibits a buy-back if the end result of such an acquisition of shares would prevent the company from fulfilling its financial obligations - being unable to pay the creditors of the company timeously. It should be noted that section 48 does not explicitly refer to an intra vires act, but refers to the requirements of section 46 in the event of a buy-back. Section 46(1)(a) requires a legal obligation, which could imply the company's constitution.

In the following paragraphs, the focus shifts to the financial position of a company as a reason not to allow for a buy-back of shares or a decrease in the number of issued shares in terms of section 36(2).

3 Financial obligations

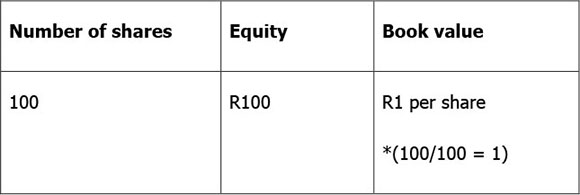

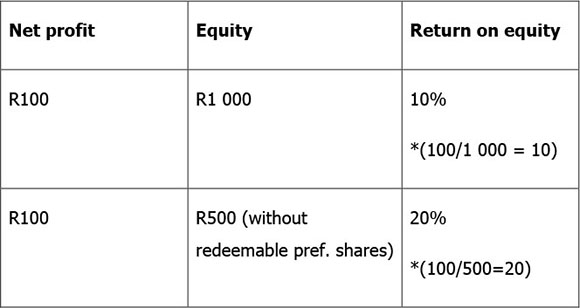

The equity or shareholders' fund is calculated by deducting liabilities from assets as disclosed in the balance sheet of the company. The book value of a share is determined by dividing the equity by the number of issued shares. This method is used for both par and no-par value shares in order to determine the book value of a company's shares,41 and can be illustrated as follows:

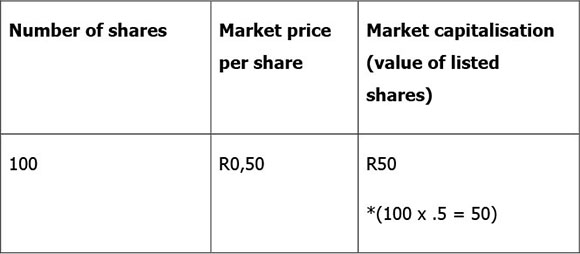

In the Rabinowitz case,42 the court used the book value and not the market price of the shares to determine their value. Although this may be correct, it should be noted here that the market price of a share is not a confirmation of the value of the company as a going concern,43 but is merely used to calculate the current value of a listed share-capital company. This approach to calculating value is known as the market capitalisation of a listed company.44 The following serves to illustrate this:

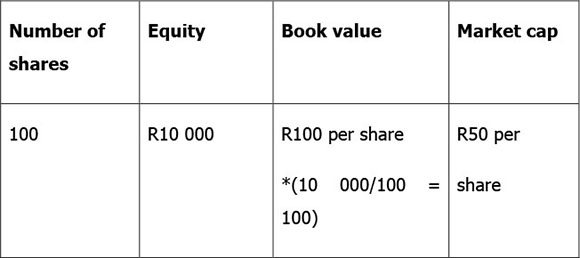

However, the book value of a going concern is important, as it illustrates the relationship between the market price of a listed share and the book value per share, in other words, whether the market price of the share is overvalued or undervalued compared to the book value per share, as follows:

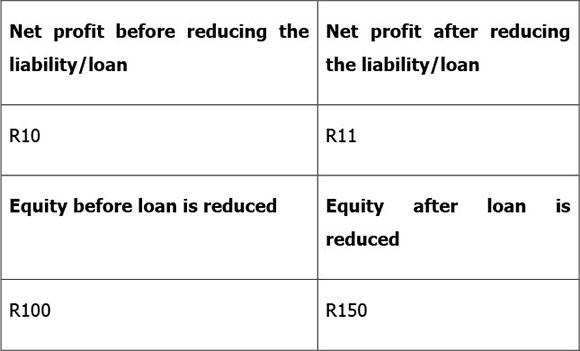

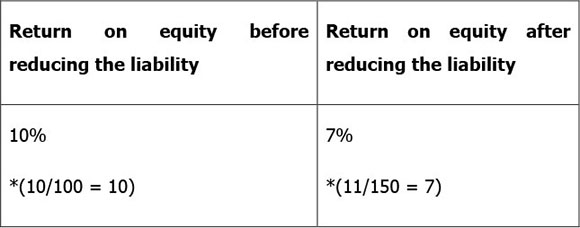

If the shares are undervalued upon comparing the book value to the market cap,45 this indicates grounds for a possible takeover bid, for example to acquire the company for R50 when the book value of its shares is R100 (see the table above). Similarly, if the book value is less than the market cap, it indicates that the price listed for the shares is overvalued. In order to increase the book value of the shares the board of directors will largely focus on reducing the company's debt or liabilities. As the debt decreases, the equity of the company will increase, since the amount of the liabilities deducted in the income statement will be less. Therefore, equity in the balance statement will increase. To illustrate this, the debt-to-equity ratio - which is also important to obtain a holistic view of the book value of shares - is used to spot artificial increases in earnings per share or book value per share.46

Instead of altering the debt-to-equity ratio, for example by paying off the debt, the board of directors can use section 48 to alter the capital structure of the issued shares, and consequently artificially raise the issued shares' book value. Although capital or cash is required to fund the acquisition, this can easily be avoided by using section 36(2) of the 2008 Companies Act, which also alters the capital structure of shares without any cash in return for shares.47 Thus, section 36(2) is the focus of the following paragraph.

4 Altering the book value of shares without a buy-back

Section 75 of the 1973 Companies Act provides for altering the composition of the number of issued shares in relation to the share capital of the company.48 Section 75(1) states as follows:

Subject to the provisions of sections 56 and 102 a company having a share capital, if so authorized by its articles, may by special resolution-

(c) consolidate and divide all or any part of its share capital into shares of larger amount than its existing shares or consolidate and reduce the number of the issued no par value shares;

(i) convert any of its shares, whether issued or not, into shares of another class.

Section 36(2) of the 2008 Companies Act states as follows:

The authorisation and classification of shares, number of authorised shares of each class and the preferences, rights, limitations and other terms associated with each class of shares, as set out in the company's memorandum of Incorporation, may be changed only by-

an amendment of the memorandum of incorporation by special resolution of the shareholders or the board of the company, in the manner contemplated in subsection 3 except to the extent that the memorandum of incorporation provides otherwise.

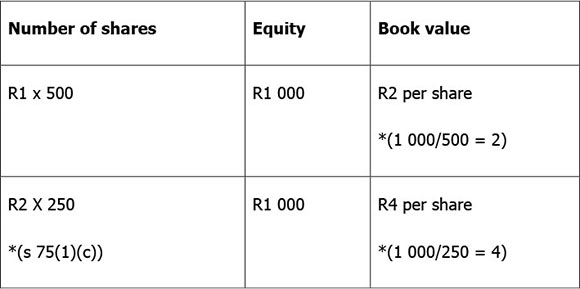

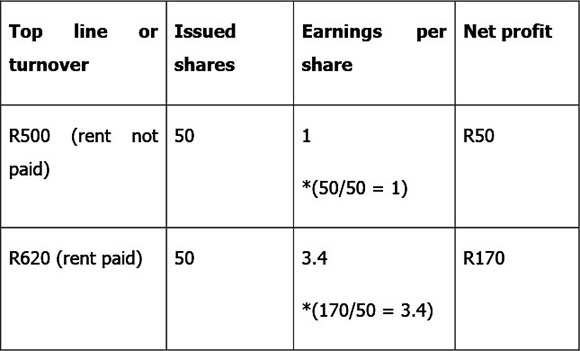

If the company has made use of section 36(2), the number of issued shares will be altered legally to "shares of larger amount", for instance 500 at R1 each converted into 250 at R2 each. To a potential investor, the result will indicate higher earnings per share (net profit divided by fewer shares),49 producing a promising book value per share in the balance sheet.50 The following table serves to illustrate this:

The above also applies to earnings per share. Equity increases through company profitability, as was discussed earlier and was illustrated by the debt-to-equity ratio. For example, if net profit is R1 000, earnings per share would be R4 per share (1 000/250). Compare this to 500 issued shares, which would work out to earnings per share of R2 per share (1 000/500). If a company is listed on the stock exchange and the listed price per share is R8, R8/R4 per share equals 2, compared to R8/R2 per share, which equals 4. In economic reality, the former simply is more investment-attractive.

Not only does section 36(2) influence the earnings-per-share ratio, but it affects other financial ratios as well. Section 36(2) can be utilised to alter the composition of the share capital of a company by converting certain shares into redeemable preference shares. Although the earnings-per-share ratio will be unchanged by the alteration, the return-on-equity ratio will be affected.51 Redeemable preference shares are excluded52 from the shareholders fund; therefore, without increasing the net profits of a company, the return on equity will indicate a greater return, as follows:53

This artificial method of altering the status of "shares" can convert any share-capital company into a company that is attractive to investors, by means of skilful financial engineering as permitted by section 36(2). Also, the 2008 Companies Act provides for the conversion of shares into other classes of shares in terms of section 41(3). Moreover, the 2008 Act and the 2007 Bill, in sections 36(3)(a) and 34(2)(a), also make provision for increasing or decreasing the number of shares. In essence, sections 36(3)(a) or 34(2)(a) allow for an artificial increase in earnings per share without complying with section 4 of the 2008 Act, as was discussed earlier.

The following represent some guidelines as to which companies should ideally be allowed to buy back shares, and which not. The same rationale should be applied to the use of section 36(2).

5 Economic categories of companies

5.1 A company experiencing fewer net profits than in previous financial years

A company that experiences fewer retained profits along with increased liabilities will command less financial leverage to conduct business continuously,54 and poses a greater risk of future liquidation or financial collapse.55 Under such circumstances, a company should not be allowed to acquire its own shares.56 See the following table as an illustration:

5.2 A company with a marginal or high growth rate

An increase or growth in the top line (the turnover) will increase the company's additional current assets (for example cash) with which to conduct business continuously.57 It is therefore very important to understand in what way the company financed the increase (the growth) in turnover.58 If the company did so by means of increased liabilities, its profitability may be negatively influenced if the anticipated increase in the top line is not achieved, resulting in a decrease in net profit. This would constitute a poor financial position like that in paragraph 5.1 above. On the other hand, marginal or high growth achieved through current assets will lead to net profits that are linear to the increase in the top line.

An increase in liabilities and a decrease in profitability will be an indication that the growth and profits are not in equilibrium and, consequently, the earnings per share will decrease. The board of directors must therefore adjust the growth rate of the company to yield favourable profitability results, as evidenced by the earnings-per-share ratio. Unless these circumstances are achieved, this type of company should also not be allowed to acquire its own shares as a method of artificially increasing the value of its shares.

The following section serves to explain the concept of artificial increases in more detail, before it is illustrated with reference to a case law example.

6 Linearity between assets, profits and growth as a requirement to allow a buy-back of shares

6.1 The concept

Establishing whether assets, growth and net profit are in equilibrium, or linear to each other, requires a simple financial calculation or mere common sense.59 For example, if the current assets (cash) are being used adequately to produce an increase or growth in the top line, the direct result should be an increase in net profits or equity reflected in a promising earnings-per-share ratio.

On the other hand, if a company increases its liabilities to finance a buy-back of its own shares, this will affect the profitability of the company negatively.60 Under such circumstances there will be greater pressure on the current assets to increase not only the top line61 but to ensure that the additional liabilities deducted in the income statement will disclose favourable net profits. In an economic reality, the possibility arises that the current assets will not be sufficient to maintain previous profitability results owing to the additional burden of financing.

6.2 Case law example of non-linear assets, growth and profit

In the Rosslare case,62 the assets, growth and profit of the company must be assumed not to have been in balance, owing to the fact that the company had redeemed a liability through allotting additional shares. The asset concerned was a block of flats in which a member/shareholder could occupy a flat without paying rent. The plaintiff argued that the occupation of a flat was in fact a reduction of the capital of the company. The court held that this was not so.

It must be respectfully stated that the case seems to have been decided incorrectly. To illustrate why, the following liability example is again used. A liability places pressure on the top line/turnover of a company to produce sufficient net profits. If a liability is reduced, it follows that there will be increased net profits, evidenced by an increased earnings-per-share ratio.63

The increase in net profits stemming from the reduced liability will increase the earnings-per-share ratio.64

Applying this logic to the case cited above, the occupation of a flat requires rent (growth) to be paid, and will consequently increase the top line linearly to net profits, which implies an increase in earnings per share. If rent is not paid, the asset or flat is not linear to the top line and, consequently, there is no increase in earnings per share. It is well understood that if rent is not paid, it dilutes the value of the lease agreement, and thus also the value of the shares of the company as a going concern.

From the table above, it is clear that the extra growth experienced in the top line as a direct result of the rental income indicates linearity between the rental income, growth and profitability through the earnings-per-share ratio. When rent is not paid, the number of issued shares (50) can be reduced to 15 to equal earnings per share similar to those if rent were paid - 50/15 equals 3.3 (3.4 in the above table) - by making use of section 36(2). For this reason, it is submitted that clever financial engineering should also be subject to section 4 or at least the giving of a reason as to why the company requires a decrease in the number of issued shares so as to avoid an artificial increase in earnings per share.65

7 More case law: earnings per share and specific performance

In the Haynes case,66 Judge De Villiers dealt with the matter of the court's discretion to grant an order for specific performance. There are certain principles affecting the court's discretion not to order specific performance if the same result could be achieved by ordering the payment of damages. A favourable economic reality may be achieved by ordering damages instead of specific performance.

In the Benson case,67 however, the Appellate Division rejected the latter principle. In terms of the general principles of breach of contract, the innocent party has a right to elect either specific performance or damages.68 The plaintiff in the Benson case purchased 171 500 shares, but received delivery of only 107 900. The plaintiff claimed specific performance of 63 600. The court granted the order on the basis of equity and in accordance with public policy.69 If the court had applied the English-law principle as found in the Haynes case, the company that had failed to deliver the additional 63 600 shares would have increased its earnings per share, as these 63 600 would not have been taken into account when calculating earnings per share.70

8 Conclusion

The Companies Act of 1973 did not make any provision for a maximum or minimum amount of capital required to float a company, or for a minimum number of shares to be issued.71 It is therefore possible for the promoters to excessively exercise their discretion when deciding on the authorised share capital, and later tailor-make (by buying back shares) or financially engineer the share capital structure in accordance with the business potential of the company, in order to generate an attractive earnings per share, especially in respect of listed companies.

This has not been altered by the Companies Act of 2008. Besides the latter statutory regulation, as was discussed earlier, it is consequently proposed that trafficking in shares (such as the buy-back of shares) must be prohibited if the purpose of a buy-back is to artificially increase the company's investment attractiveness.72 In addition, the buy-back of shares could easily be avoided by making use of section 36(2), which requires no solvency/liquidity ratios or any authorisation required in the memorandum of incorporation to amend the number of issued shares.73 All that is required is a special resolution to amend the number of shares.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Literature

Atkinson PJ Financial Collapse: A Critical Study of Events Leading to the Judicial Management or Liquidation of selected Public Companies (MCom thesis UNISA 1979) [ Links ]

Auret CJ and De Villiers JU "A Comparison of Earnings per Share and Dividends per Share as Explanatory Variables for Share Price" 2000 SEE 39-53 [ Links ]

Bannock G, Baxter RE and Davis E Dictionary of Economics 7th ed (Penguin London 2003) [ Links ]

Benade ML et al Entrepreneurial Law 3rd ed (LexisNexis Butterworths Durban 2003) [ Links ]

Berelowitz J "Legal Aspects of the Valuation of Shares" 1979 De Rebus 199-202 [ Links ]

Black A, Wright P and Davies J In Search of Shareholder Value: Managing the Drivers of Performance 2nd ed (Prentice Hall New York 2001) [ Links ]

Brews PJ "Corporate Growth through Mergers and Acquisitions: Viable Strategy or Road to Ruin?" 1987 S Afr J Bus Manag 10-21 [ Links ]

Brews PJ Towards a More Appropriate Take-over Regulation in South Africa (PhD thesis University of Witwatersrand 1990) [ Links ]

Briggs D "The Purchase by a Company of its Own Shares" 1981 De Rebus 293-294 [ Links ]

Cassim FHI "The Rise, the Fall and the Reform of the Ultra Vires Doctrine" 1998 SA Merc LJ 293-315 [ Links ]

Cassim FHI "The Reform of Company Law and the Capital Maintenance Concept" 2005 SALJ 283-293 [ Links ]

Cilliers HS et al Korporatiewe Reg 2nd ed (Butterworths Durban 1992) [ Links ]

Cilliers HS et al Corporate Law 3rd ed (Butterworths Durban 2000) [ Links ]

Correia C et al Financial Management 2nd ed (Juta Cape Town 1993) [ Links ]

De Koker L Roekelose of Bedrieglike Dryf van Besigheid in die Suid-Afrikaanse Maatskappyereg (LLD thesis University of the Orange Free State 1996) [ Links ]

De Villiers JU et al "Earnings per share and the cash flow per share as determinants of share value: test of significance using the bootstrap with demsetz's method" 2003 SEE 95-125 [ Links ]

Delport PA Verkryging van Kapitaal: 'n Aanbod van Aandele (LLD thesis University of Pretoria 1987) [ Links ]

Dempsey A and Pieters HN Inleiding tot Finansiële Rekeningkunde (Lexicon Isando 1993) [ Links ]

Donnan F "The Share Ratio Act: Innovation or Experimentation in Securities Regulation?" 1996 C & SLJ 101-112 [ Links ]

Geyser M and Liebenberg IE "Creating a New Valuation Tool for South African Agricultural Co-operatives" 2003 Agrekon 106-115 [ Links ]

Jooste R "The Maintenance of Capital and the Companies Bill 2007" 2007 SALJ 710-733 [ Links ]

Kerr AJ The Law of Sale and Lease 2nd ed (Butterworths Durban 1996) [ Links ]

Kerr AJ The Principles of the Law of Contract 6th ed (LexisNexis Butterworths Durban 2002) [ Links ]

Kilian CG and Du Plessis JJ "Possible Remedies for Shareholders When a Company Refuses to Declare Dividends or Declare Inadequate Dividends" 2005 TSAR 48-60 [ Links ]

Marx J (ed) Investment Management (Van Schaik Pretoria 2005) [ Links ]

Meskin PM (ed) Henochsberg on the Companies Act 4th ed (Butterworths Durban 1985) [ Links ]

Meskin PM (ed) Henochsberg on the Companies Act 5th ed (Butterworths Durban 1994) [ Links ]

Pollard SM "An Update on the Calculation of Interest on Preference Payments" 1995 C & SLJ 353-365 [ Links ]

Pretorius JT et al Hahlo's South African Company Law Through the Cases: A Source Book 5th ed (Juta Cape Town 1991) [ Links ]

Pretorius JT et al Hahlo's South African Company Law Through the Cases: A Source Book 6th ed (Juta Cape Town 1999) [ Links ]

Rappaport A Creating Shareholder Value: The New Standard for Business Performance (Free Press New York 1998) [ Links ]

Ribstein LE "Efficiency, Regulation and Competition: A Comment on Easterbrooke and Fischel's Economic Structure of Corporate Law" 1992 Nw U L Rev 254-286 [ Links ]

South African Institute of Chartered Accountants The Usefulness of Financial Statements AC 000.26 (SAICA Johannesburg 2004) [ Links ]

South African Institute of Chartered Accountants Earnings per Share AC 104 (SAICA Johannesburg 2007) [ Links ]

Smit A "Die Bydrae van die Franchisebedryf tot die Suid-Afrikaanse Ekonomie en die Faktore wat die Waarde van 'n Franchisebedryf Beïnvloed" 2007 TGW 181-191 [ Links ]

Smullen J and Hand N Dictionary of Accounting (Oxford University Press Oxford 2005) [ Links ]

Stainbank L and Harrod K "Headline Earnings per Share: Financial Managers' Perceptions and Actual Disclosure Practices in South Africa" 2007 Meditari: Accountancy Research 91-113 [ Links ]

Van der Linde K "The Solvency and Liquidity Approach in the Companies Act 2008" 2009 TSAR 224-238 [ Links ]

Vigario F Managerial Accounting and Finance 2nd ed (F Vigario Kloof 1998) [ Links ]

Walsh C Key Management Ratios: The 100+ Ratios Every Manager Needs to Know (Prentice Hall Harlow 1996) [ Links ]

Weaver T and Keys B Mergers and Acquisitions 11th ed (Ernst & Young Johannesburg 2002) [ Links ]

Wessels JW "The Future of Roman-Dutch Law in South Africa" 1920 SALJ 265-284 [ Links ]

Yeats J and Jooste R "Financial Assistance: A New Approach" 2009 SALJ 566-587 [ Links ]

Case law

Amalgamated Packaging Industries (Rhodesia) Ltd 1963 1 SA 335 (SR)

Axiam Hoddnngs v Deloitte & Touche 2006 1 SA 237 (SCA)

Benson v SA Mutual Life Assurance Society 1986 1 SA 776 (A)

Cachalia v De Klerk and Benjamin 1952 4 SA 672 (T)

Capitex Bank Ltd v Qorus Hoddnngs Ltd 2003 3 SA 302 (W)

Cohen v Segal 1970 3 SA 702 (W)

Dean v Prince 1954 1 All ER 749 (CA)

Donaldson Investments v Anglo-Transvaal Collieries 1979 3 SA 713 (W)

Ex Parte Associated Lead Manufacturers (Pty) Ltd 1960 2 SA 36 (D)

Ex Parte Coca Coca (Pty) Ltd 1947 3 SA 571 (T)

Ex Parte National Industrial Credit Corporation Ltd 1950 2 SA 10 (W)

Ex Parte NBSA Centre Ltd 1987 2 SA 783 (T)

Ex Parte Rattham & Son (Pty) Ltd 1959 2 SA 741 (SR)

Ex Parte Rietfontein Estates Ltd 1976 1 SA 175 (W)

Ex Parte Seafoods Successors Ltd 1957 3 SA 73 (D)

Ex Parte Witwatersrand Board of Executors Building Society & Trust Co Ltd 1926 WLD 205

Extel Industrial (Pty) Ltd v Crown Mils (Pty) Ltd 1999 2 SA 719 (SCA)

Haynes v King Williams Town Municipality 1951 2 SA 371 (A)

Hogg v Cramphorn 1967 Ch 254

Hoice Holdings Ltd v Yabeng Investment Holding Co Ltd 2001 3 SA 1350 (W)

Ilic v Parginos 1985 1 SA 795 (A)

In Re X Ltd 1982 2 SA 471 (W)

Katzoff v Glaser 1948 4 SA 630 (T)

Klein v Kolosus Holdings Ltd 2003 6 SA 198 (T)

Kleynhans v Van der Westhuzzen 1970 2 SA 742 (A)

Knox D'Arcy Ltd v Jamieson 1996 4 SA 348 (A)

Mills v Mills 1938 60 CLR 150 (High Court of Australia)

Rabinowitz v Ned-Equity Insurance Co Ltd 1980 1 SA 403 (W)

Rex v Milne and Erleigh (7) 1951 1 SA 791 (A)

Rosslare v Registrar of Companies 1972 2 SA 524 (D)

Trevor v Whitworth 1887 12 AC 409 (HL)

Legislation

Companies Act 61 of 1973

Companies Act 71 of 2008

Companies Amendment Act 37 of 1999

Companies Bill, 2007 [B61-2008]

Internet sources

Australian Accounting Standards Board 2005 Pronouncements http://www.aasb.co.au/pronouncements/aasb_standards_2005.htm accessed 25 July 2005 [ Links ]

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AASB Australian Accounting Standards Board

C & SLJ Company and Securities Law Journal

NW U L Rev Northwestern University Law Review

S Afr J Bus Manag South African Journal of Business Management

SA Merc LJ South African Mercantile Law Journal

SAICA South African Institute of Chartered Accountants

SALJ South African Law Journal

SEE Journal for Studies in Economics and Econometrics

TGW Tydskrif vir die Geesteswetenskappe

TSAR Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg

1 Companies Act 61 of 1973.

2 Companies Act 71 of 2008.

3 Smullen and Hand Dictionary 148.

4 Bannock, Baxter and Davis Dictionary 107.

5 Cilliers et al Corporate Law para 16.20. The rules of the JSE require shares to be issued for at least R1 per share - see Amalgamated Packaging Industries (Rhodesia) Ltd 1963 1 SA 335 (SR); Ex Parte Rietfonten Estates Ltd 1976 1 SA 175 (W); Companies Act 61 of 1973.

6 Walsh Key Management Ratios 82. The excess cash will increase the "total assets" as disclosed in the balance sheet. The return on total assets ratio will thus produce an indication of ineffective asset utilisation by the management to produce sales/turnover. A promoter is not required to have any business background or financial qualifications to float a company.

7 Benade et al Entrepreneurial Law 150. Although the company's constitution is a public document, the issue price par value is of no importance. This is clearly evident from the philosophy pertaining to no-par value shares. If an unlisted public company issues 20 million shares at 1c each, the earnings per share would be less than in the case of 10 million shares at 2c each.

8 See in general Ex Parte Seafoods Successors Ltd 1957 3 SA 73 (D); Ex Parte Rattham & Son (Pty) Ltd 1959 2 SA 741 (SR); Ex Parte Associated Lead Manufacturers (Pty) Ltd 1960 2 SA 36 (D).

9 Stainbank and Harrod Meditari 91. These authors suggested that earnings per share should be stated in the company's financial statements. Also see De Villiers et al SEE 95; Auret and De Villiers 2000 SEE 39.

10 Walsh Key Management Ratios 260-275; Vigario Managerial Accounting 285; Katzoff v Glaser 1948 4 SA 630 (T) 636: "...the value of anything is what it is worth at the time". In Dean v Prince 1954 1 All ER 749 (CA), the court remarked that there is no accountancy principle that fixes or limits the calculation of the value of shares. Also see Donaldson Investments v Anglo-Transvaal Collieries 1979 3 SA 713 (W) 731H-732B.

11 Companies Amendment Act 37 of 1999; Pretorius et al Company Law (6th ed) 121; Brews Take-over Regulation 28, 142.

12 Section 85(4) of the Companies Act 61 of 1973: "A company shall not make any payment in whatever form to acquire any share issued by the company if there are reasonable grounds for believing that - (a) the company is, or would after the payment be, unable to pay its debts as they become due in the ordinary course of business or (b) the consolidated assets of the company fairly valued would after the payment be less than the consolidated liabilities of the company."

13 Section 85(1)-(3) of the Companies Act 61 of 1973 required the permission of creditors to allow for a buy-back of company shares.

14 Hoice Holdings Ltd v Yabeng Investment Holding Co Ltd 2001 3 SA 1350 (W); Capitex Bank Ltd v Qorus Holdings Ltd 2003 3 SA 302 (W).

15 SAICA Financial Statements, Walsh Key Management Ratios 82. The cash-flow cycle also depends on the balance sheet information. Also see Klein v Kolosus Holdings Ltd 2003 6 SA 198 (t); Cachalia v De Klerk and Benjamin 1952 4 SA 672 (T); Extel Industrial (Pty) Ltd v Crown Mills (Pty) Ltd 1999 2 SA 719 (SCA) 732F; Iicc v Pargnnos 1985 1 SA 795 (A) 803D; Keynhans v Van der Westhuizen 1970 2 SA 742 (A); Knox D'Arcy Ltd v Jameson 1996 4 SA 348 (A).

16 See Donaldson Investments v Anglo-Transvaal Collieries 1979 3 SA (W) 731H, 732B. Shareholder value is not calculated by means of the earnings per share times the number of issued shares.

17Companies Bill, 2007 [B61-2008].

18 The 2008 Act contains similar wording.

19 Section 4(1)(b)(i) of the Companies Act 71 of 2008 also refers to 12 months.

20 Atkinson Financial Collapse 46: "Notwithstanding the apparent success of the use of ratio analysis in the prediction of company failure, it should be noted that some researchers comment that, while ratios of failed firms were found to be significantly different from those of non-failed firms, the ability of such ratios to predict failure was not so conclusive." In this regard, the internal rate of return should be calculated and compared to the weighted average cost of capital. If the internal rate of return is less, the forecast value of the company would be less than that of a company able to create a greater internal rate of return.

21 Black, Wright and Davies In Search of Shareholder Value 23: "We raise capital ... sell it at an operating profit. Then we pay the cost of the capital. Shareholders pocket the difference." The greater the liabilities, the greater the weighted average cost of capital, and consequently, the less the profits. Also see Delport Verkryging van Kapitaal 205.

22 Trevor v Whitworth 1887 12 AC 409 (HL); Pretorius et al Company Law (6th ed) 122; Benade et al Entrepreneurial Law 180.

23 Briggs 1981 De Rebus 293; Ex Parte Rietfontenn Estates Ltd 1976 1 SA 175 (W); Meskin Henochsberg (4th ed) 135. Before the Act was amended, s 83 regulated the reduction of share capital; Jooste 2007 SALJ 710; Yeats and Jooste 2009 SALJ 566.

24 Cilliers et al Corporate Law para 190.01: the shareholders are a personification of the company, and are in reality the company; see Meskin Henochsberg (4th ed) 135.

25 Also see Cohen v Segal 1970 3 SA 702 (W) 706.

26 Ex Parte NBSA Centre Ltd 1987 2 SA 783 (T) 785. In this regard, s 311 of the Companies Act 61 of 1973 can be considered illegal in terms of reducing the share capital of the company through a buy-back of its own shares, unless so agreed by the members of the company. The consequence of an ultra vires act is that the buy-back is voided; Cassim 1998 SA Merc LJ 293; Cilliers et al Corporate Law para 12.14.

27 Cassim 2005 SALJ 283.

28 Meskin Henochsberg (5th ed) 179.

29 See in general Ex Parte Witwatersrand Board of Executors Building Society & Trust Co Ltd 1926 WLD 205.

30 Black, Wright and Davies In Search of Shareholder Vauue 23; Delport Verkryging van Kapttaal 205.

31 Kilian and Du Plessis 2005 TSAR 48; Van der Linde 2009 TSAR 224.

32 Trevor v Whitworth 1887 12 AC 409 (HL); Pretorius et al Company Law (6th ed) 122; Benade et al Entrepreneurial Law 180.

33 Pretorius et al Company Law (6th ed) 122.

34 Hogg v Cramphorn 1967 Ch 254.

35 Hogg v Cramphorn 1967 Ch 254 265. Judge Buckley held that the majority of shareholders were acting oppressively towards the minority and/or that the powers of the directors interfered with the shareholders' rights as stipulated in the company's constitution.

36 Mills v Mills 1938 60 CLR 150 (High Court of Australia).

37 Mills v Mills 1938 60 CLR 150 (High Court of Australia) 162.

38 Mills v Mills 1938 60 CLR 150 (High Court of Australia) 162-163.

39 Axiam Holdings v Deloitte & Touche 2006 1 SA 237 (SCA); Correia et al Financial Management 512. The company's operations may create profit, but its future continuation depends on the availability of cash.

40 Kilian and Du Plessis 2005 TSAR 48; In Re X Ltd 1982 2 SA 471 (W) 477; Ex Parte Coca Cola (Pty) Ltd 1947 3 SA 571 (T); Ex Parte National Industrial Credit Corporation Ltd 1950 2 SA 10 (w); Berelowitz 1979 De Rebus 199, 202. A skilful broker can realise shares without affecting their current listed price.

41 Marx Investment Management 131-151. There are five different methods to calculate the value of a share, and a specific method serves a purpose in a specific circumstance, ie for a business to be valued as a going concern or not.

42 Rabinowttz v Ned-Equiti Insurance Co Ltd 1980 1 SA 403 (W).

43 Donaldson Investments v Anglo-Transvaal Collieries 1979 3 SA 713 (W) 731H-732B. The council's argument was that the net asset value or book value of shares is calculated as market cap (italisation). This is incorrect.

44 See Berelowitz 1979 De Rebus 201.

45 The market cap is calculated as the number of issued shares multiplied by the listed price per share.

46 Geyser and Liebenberg 2003 Agrekon 106. The authors recommend the shareholder value-added method as the performance measurement of an enterprise's value in the future. In Smit 2007 TGW 181, the author discusses why small- to medium-sized businesses fail in the commercial world, eg, because management does not undertake financial planning. The shareholder value-added or the economic value-added method indicates whether management is able to perform financial planning adequately, as it makes use of a forecast of current management decisions, linking these to business value. Also see Donaldson Investments v Anglo-Transvaal Collieries 1979 3 SA 713 (W) 731H-732B.

47 Companies Act 61 of 1973.

48 Cilliers et al Corporate Law 381.

49 See Weaver and Keys Mergers 14.

50 Walsh Key Management Ratios 170.

51 Marx Investment Management 139; Klein v Kalosus Holdings Ltd 2003 SA 6 SA 198 (T), where the court dealt with a reduction in share capital; Correia et al Financial Management 205.

52 Cilliers et al Korporatiewe Reg 224, 337. The authors explain redeemable shares as a "... hibriede vorm van aandele en skuldbriewe met eienskappe van beide ... alhoewel hul suiwer as aandele beskou word". Also see SAICA Earnings.

53 Walsh Key Management Ratios 182. The stock market price of a share, divided by the book value of a share, must produce the same ratio when dividing the return on equity through the earnings yield.

54 Walsh Key Management Ratios 190. Increased liabilities can create increased profit as well as increased risk. The increase in liabilities should therefore increase the value of shareholders' equity at the same time. However, if the ratio/balance between debt and equity is increased beyond a prudent level - although this may indicate an increased earnings yield or a stronger return on equity - it will serve to reduce the total company or shareholders' value in the long term.

55 Atkinson Financial Collapse 22; De Koker Roekelose of Bedrieglike Dryf van Besigheid 47; Vigario Managerial Accounting 296.

56 Donnan 1996 C& SLJ 101, which contains an interesting account of the business rules on share ratios.

57 Axiam Holdings v Deloitte & Touche 2006 1 SA 237 (SCA); AASB 2005 http://www.aasb.co.au/pronouncements/aasb_standards_2005.htm; Dempsey and Pieters Inleiding 69 - "[w]inste is inkomste minus uitgawes"; Correia et al Financial Management 512 -the company's operations may create profit, but its future continuation depends on the availability of cash.

58 Marx Investment Management 145; Walsh Key Management Ratios 122. To determine the cash-flow cycle, stock will be divided by the top line (sales), multiplied by 365 (ie expressed in days). The same approach will be used to determine days to the payment of accounts and account payments received. After calculating all the days, these must be added up and the accounts paid deducted, indicating the number of days on which there must be sufficient cash. This number of days divided by sales, multiplied by 365, as well as the predetermined growth in sales will express the amount of cash necessary to sustain the cash-flow cycle.

59 Rappaport Creating Shareholder Value 18. The cost of equity is 12%. To illustrate the 12% in practice, consider the following: The turnover of a company is R200. An increase/growth of 10% will increase the turnover to R220 (R15 investment). If the company invested R30, sales/turnover must be increased by 20% in order to create equity value. If sales increased by only 10%, although earnings per share may be higher, the value of the equity is less. This is because the amount of cash invested is neither equal to the growth rate nor at least 20%.

60 Marx Investment Management 133.

61 Pretorius et al Company Law (5th ed) 586, where the authors cite Ammonia Soda Co Ltd v Chamberlain, where the court in 1918 passed clear judgment on the importance of turnover (circulating capital) in relation to perpetual or everlasting existence. Since a company's focus is on circulating capital the intention is that the said capital be returned to the company at an increased (internal rate of return) rate - in other words, consisting of extra profits.

62 Rosslare v Registrar of Companies 1972 2 SA 524 (D).

63 Brews 1987 S Afr J Bus Manag 10; Donnan 1996 C & SLJ 101.

64 Marx Investment Management 131.

65 Pretorius et al Company Law (6th ed) 147. The auditors can also make use of tax returns to create higher apparent profits for a company. Tax returns differ from deferred tax on the basis of the delivery of money. Deferred tax is not money received by the company, because the Receiver of Revenue will debit the credit amount in the income statement. The reason behind this philosophy is that the company is a going concern.

66 Haynes v King William's Town Municipality 1951 2 SA 371 (A) 378; Wessels 1920 SALJ 265.

67 Benson v SA Mutual Life Assurance Society 1986 1 SA 776 (A). The Benson case also cited Rex v Milne and Erleigh (7) 1951 1 SA 791 (A) 873: "...[I]n contracts for the sale of shares which are daily dealt in on the market and can be obtained without difficulty, specific performance will not ordinarily be granted."

68 Kerr Law of Sale 598; Kerr Principles of Contract 677.

69 Pollard 1995 C & SLJ 353.

70 Kerr Law of Sale 599; Ribstein 1992 Nw U L Rev 284.

71 The rules of the JSE require shares to be issued for at least R1 per share.

72 Berelowitz 1979 De Rebus 199, 202; Brews 1987 S Afr J Bus Manag 10.

73 S 75 of the Companies Act 61 of 1973 required authorisation to amend the number of issued shares in the articles of association as well as a special resolution.