Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versão On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.17 no.6 Potchefstroom 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v17i6.01

ARTICLES

Proportionality and the limitation clauses of the South African Bill of Rights

IM Rautenbach

BA LLB (UP) LLD (UNISA). Research Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Johannesburg. Email: irautenbach@uj.ac.za

SUMMARY

"Proportionality" is a contemporary heavy-weight concept which has been described as an element of a globalised international grammar and as a foundational element of global constitutionalism. The article firstly describes the elements of proportionality as they are generally understood in foreign systems, namely whether the limitation pursues a legitimate aim, whether the limitation is capable of achieving this aim, whether the act impairs the right as little as possible and the so-called balancing stage when it must be determined whether the achievement of the aim outweighs the limitation imposed. The German academic Alexy (Theorie der Grundrechte (1986)) developed what he called a mathematical weight formula to deal with the balancing stage. An overview is provided of how the elements of proportionality were dealt with in the text of the South African interim Constitution of 1994, the early jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court, and in the text of the final Constitution of 1996. Contemporary South African academic criticism of the use of the concept is also analysed. The article then endeavours to relate the elements of Alexy's weight formula to both the elements of the South African general limitation clause in section 36 of the Constitution and to the appearance of such elements in the formulation of specific rights in the Bill of Rights. Although the levels of abstraction reached in the debates on the Alexy formula are so daunting that it is most unlikely that South African courts and practitioners will ever use it, certain valuable insights can be gained from it for the purposes of dealing with proportionality within the context of the limitation of rights in South Africa. Despite opposition from certain academics, proportionality is a prominent feature of the application of the limitation clauses in the South African Constitution. The elements of proportionality provides a useful tool for the application, within the context of the limitation of rights, of general and wide concepts such as "fairness", "reasonableness", "rationality", "public interest" and, somewhat surprisingly, also of the general concept "proportionality" as such. South Africa's participation in the global recognition and application of this way of dealing with the limitation of rights is worthwhile.

Keywords: Limitation of rights; bills of rights; proportionality; elements of proportionality; history of proportionality in the South African Constitution; balancing; weight-formula.

1 Introduction

Proportionality is a contemporary, heavy-weight concept. In 2012, two books were published on it, namely The Constitutional Structure of Proportionality by Matthias Klatt and Moritz Meister and Proportionality and Constitutional Culture by Moshe Cohen-Eliya and Iddo Porat, the first two pages of which contain many references to the popularity of the concept.1 According to Klatt and Meister it is widely accepted that proportionality is an element of a globalised, common constitutional grammar, and they refer to other writers who have described it as "indispensable ... in constitutional rights reasoning", "of central importance in modern public law" and "a foundational element of global constitutionalism".2 Bernard Schlink says that proportionality is "part of a deep structure of constitutional grammar that forms the basis of all different constitutional languages and cultures".3 Cohen-Eliya and Porat describe proportionality as "the archetypal universal doctrine of human rights adjudication" and state:4

European constitutional lawyers are concerned with predominantly one thing -proportionality. Whether you are a German constitutional lawyer, an Italian, a French or English one, you will invariably have been debating and talking about the proportionality doctrine as part of your work. Indeed not only if you are a European scholar. This would probably be true if you were a Canadian, Australian, Indian, Israeli, or a Chinese lawyer. Almost every discussion of constitutional law in these countries seems to touch at some point on proportionality, and the academic literature on proportionality has by now spawned a plethora of articles and books.5

Before investigating the reasons and justification for the popularity of proportionality Cohen-Eliya and Porat provide an in-depth comparative analysis of proportionality with reference to its German origin6 and its application in Western Europe, on the one hand, and the American doctrine of balancing on the other. Klatt and Meister also concentrate on various aspects of the structure of proportionality analysis, not only by refining the weight formula of Alexy,7 but also by making a valuable contribution to the debates on the merits and disadvantages of proportionality, the relation between proportionality and balancing8 and the relation between proportionality and deference towards the discretion exercised by other organs of state. Although the authors of these two works provide in-depth, comparative analyses of the role of proportionality in particularly the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights and in Canada, Germany and Israel, their work contains only very brief references to South Africa.9 The purpose of this article is to relate some of their insights and conclusions in respect of proportionality to the interpretation and application of limitation clauses in the South African Bill of Rights (paragraphs 6 and 7). This is done against the background of how the idea of proportionality was incorporated both in the text of the South African Constitution and in the early jurisprudence of the South African Constitutional Court (paragraphs 3 and 4), and criticism that has been levelled against this incorporation (paragraph 5). However, before that is done the elements of proportionality as it is generally understood are defined, and the way in which the concepts "limitation of rights" and "limitation clauses" are used in this article is briefly explained (paragraph 2).

2 The elements of proportionality in reviewing the limitation of rights

Some dictionary meanings of "proportion" are a "due relation of one thing to another or between parts of a thing" and (in a mathematical sense) the "equality of ratios between two pairs of quantities"; "proportionality" means "in due proportion, corresponding in degree or amount".10

In limitation analysis, it seems to be generally accepted that the "parts of the thing" or "pairs of quantities" concerned are the limitation of the right, on the one hand, and the purpose of the limitation, on the other.11 These elements were present in what is usually quoted as the first codified version of proportionality in German public law, namely in article 10(2) of the Prussian Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preussichen Staaten of 1794, which read: "The police is to take the necessary measures for the maintenance of public peace, security and order."12 Although the legislature intended to authorize the police to exercise a discretion to combat disorder, the Courts turned it into a rule that limited the exercise of the discretion, as stated by Schlink: "The police were entitled to use only means that were fit, necessary, and appropriate ...".13

The "parts of the thing" can also be described in terms of harm imposed and the benefit achieved,14 which almost inevitably leads to the idea that the parts must be weighed or balanced to find solutions to disputes that can be resolved by the formulation and application of legal rules.15 (Balancing in this sense, is therefore not undertaken to find a compromise with which the combatants are equally satisfied or dissatisfied. It usually means weighing conflicting rights and interests in order to determine who should win.)16 Weighing and balancing have always been key concepts in all endeavours to solve legal disputes, not only in state-individual relations, but also in private relations.17 South African private law literature abounds with innumerable references to the weighing and balancing of interests. Duncan Kennedy18 succinctly defines the relationship between private law balancing and public law proportionality as follows:

[M]y hypothesis is that there is a single evolving template, organized around conflict between rights and powers, between powers, between rights, involving in each case the same three questions: (a) Have the parties acted within, or been injured with respect to, their legally recognised powers or rights? (b) Has the injuror acted in a way that avoids unnecessary injury to the victim's legally protected interest? (c) If so, is the injury acceptable given the relative importance of the rights and powers asserted by the injuror and the victim? While there are, of course, dramatic practical institutional differences between balancing in private and public law, it is not clear to me that there are any differences at this more abstract analytical level.

A "due" relation between the limitation and its purpose would render the limitation justifiable. The dictionary meanings of proportionality do not tell us what kind of relation is due or appropriate. However, the mere use of the term relation implies that some or other kind of link between a limitation and a purpose must exist. This rules out the possibility that a limitation can be justified if no purpose exists, or if no purpose that may be legitimately pursued exists, or if the limitation is completely incapable of promoting the purpose. In this sense, the ordinary meaning of proportionality contains the essence of Cohen-Eliya's and Porat's preferred explanation for the spread and the global popularity of proportionality, namely that it is a key component of a culture of accountability in which those who harm others must at the very least provide plausible reasons for doing so.19 Andenas and Zlepting state: "Proportionality thus becomes a tool to enhance accountability and justification for governmental action. Additionally, judges may also become more accountable since they also have to justify their decisions in a detailed fashion."20 It must be noted, however, that proportionality involves more than just providing reasons for the sake of accountability regardless of whether they are good or silly reasons. In very general terms it is usually also stated that the reasons given must be "plausible" or "proper" reasons, and whatever "plausible" or "proper" might mean, these qualifications mean that proportionality inevitably also has a substantive meaning.

There seems to be a fair amount of consensus on the elements of proportionality. These elements are also known as "stages",21 or rules "in the sense of optimization requirements", or "subprinciples of the proportionality test",22 or "the four-prong structure of proportionality".23 Whatever they are called, the following are usually referred to: legitimate ends (purposes), suitability, necessity, and proportionality in a narrow sense.24 Klatt and Meister summarise the meaning of the different concepts as follows:

The first stage examines whether the act pursues a legitimate aim; suitability, whether the act is capable of achieving this aim; necessity, whether the act impairs the right as little as possible; and the balancing stage, whether the act represents a net gain, when the reduction on enjoyment of rights is weighed against the level of realization of the aim.25

However, one must be careful not to oversimplify the "rules" contained in this summary. For example, "whether the act is capable of achieving this aim" is generally known as a rational relationship test with which all factual limitations must comply. But it must be noted that in its most basic form it simply means that the limitation is capable of contributing "something" towards achieving the goal, which can never be said to be the final answer in respect of suitability. In certain instances depending on the weighing exercise in the final stage it may be required that the limitation must be capable of contributing "substantively" or "in all respects" towards the goal.

In this article, "the limitation of rights" refers to situations in which laws or actions, after the commencement of the Constitution, affect the conduct and interests protected by the constitutional rights. Constitutionally valid limitations must comply with all of the requirements imposed by the Constitution. How these limitations may be formulated in a Constitution is referred to below.

The qualification "after the commencement of the Constitution" indicates that we are not concerned in this article with certain limitations inserted in the definition of the rights by the constitution makers by, for example, limiting those who may benefit from the right expressly to children or citizens; or by excluding expressly certain conduct and interests from the ordinary meaning of the words used in the text to describe the protected conduct and interest.26 Constitution makers follow the latter approach when they are convinced that the excluded conduct is so harmful to other public and private interests that it is not worthy of constitutional protection. They therefore do the balancing or weighing themselves before the commencement of the Constitution and do not leave it to the Courts to do after the event either in terms of limitation clauses or, when a Constitution does not have limitation clauses, in terms of limitation requirements developed by the Courts themselves. In principle, Courts should after the commencement of the Constitution not engage in attaching narrow meanings to the description of protected conduct and interests so as to exclude conduct not worthy of constitutional protection from the protective ambit of rights.27 All instances of narrowing after the commencement of the Constitution of the meaning of the constitutionally imposed duties or the protected conduct and interests always involve a measure of balancing and weighing,28 and this should preferably be the outcome of the application of limitation clauses, which is more in line with a culture of iustifiability.29 Klatt and Meister explain that "[t]here is no need to exclude certain considerations from balancing by means of a narrow definition, since the balancing model is able to assign the proper weight to them".30 They also explain:

Once certain behaviour is protected prima facie, the state has to iustify the infringement of the right by applying the right's limitations, inter alia the proportionality test. Within the proportionality test, balancing has to be done according to the law of balancing, that means openly and traceably. ... This burdens the state with the duty to give reasons for the limitations, instead of burdening the people with the duty to iustify exercising their rights, and thus prevents iudicial arbitrariness. Therefore, broad definitions of rights are preferable.31

Modern Bills of Rights usually provide expressly for the limitation of rights by institutions or persons after the commencement of the constitution.32 Constitutions could contain general limitation clauses that apply to all rights in the Bill of Rights; or provisions that apply only to the limitation of specific rights; or they could contain a general limitation clause and provisions relating to specific rights which qualify or merely reiterate aspects of the general limitation clause.33 When Constitutions do not provide expressly for the limitation of rights, which is the case with most rights in the Constitution of the United States and some of the rights in the German Constitution,34 the Courts develop requirements for the limitation of rights. The South African Constitution contains a general limitation clause and there are several sections in the Bill of Rights with provisions that qualify or reiterate aspects of the general limitation clause in respect of the limitation of specific rights.35

3 Proportionality and the general limitation clause of the interim Constitution (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 200 of 1993) and the early jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court

The first subsection of the general limitation clause in the interim Constitution read:

33(1) The rights entrenched in this Chapter may be limited by law of general application, provided that such limitation -

(a) shall be permissible only to the extent that it is - (i) reasonable; and (ii) justifiable in an open and democratic society based on freedom and equality; and

(b) shall not negate the essential content of the right in question, and further provided that any limitation to

(aa) a right entrenched in section 10, 11, 12, 14(1), 21, 25 or 30(1)(d) or (e) or (2);36 or

(bb) a right entrenched in section 15, 16, 17, 18, 23 or 24, in so far as such right relates to free and fair political activity,37

shall, in addition to being reasonable as required in paragraph (a)(i), also be necessary.

This general limitation clause did not refer expressly to proportionality.

Whereas the genealogical history of the clause has been recorded by Du Plessis and Corder,38 hardly any attention has been paid to how and why South Africa's Constitutional Assembly moved from that clause to the clause in the final Constitution and how proportionality featured in what transpired.

In the first reported judgment of the South African Constitutional Court, S v Zuma,39 the Court was not enthusiastic about the "proportionality" test applied by the Canadian Courts in dealing with the general limitation clause in article 1 of the Canadian Constitution.40 Kentridge AJ said on behalf of a unanimous Court:41

The Canadian courts have evolved certain criteria, in applying [section 1], such as the existence of substantial and pressing public needs which are met by the impugned statute. There, if the statutory violation is to be justified it must also pass a 'proportionality' test, which the courts dissect into several components. ... These criteria may well be of assistance to our courts in cases where a delicate balancing of individual rights against social interests is required. But section 33(1) itself sets out the criteria which we are to apply, and I see no reason, in this case at least, to attempt to fit our analysis into the Canadian pattern.

However, having said that, the Court then did indeed consider the generally recognized elements of the proportionality review, namely "a rational connection test" as part of balanced relation between the limitation and its purpose, the nature of the rights affected as being "fundamental to our concepts of justice and forensic fairness", the availability of less intrusive ways to achieve the purpose (the state failed to convince the Court "that it is in practice impossible or unduly burdensome for the State to discharge its onus"), "administration of justice" as a purpose of the limitation and the effect of the limitation on the victims of the factual limitation of their rights.42 In doing so, the Court provides both an example in the statements quoted above of an approach that is "reasonable" and/or "necessary" on the one hand, and the elements of proportionality, on the other, which should be seen as alternative tests, and also an example of an implicit refutation of the distinction. To regard reasonableness/necessity and rationality as alternative tests is an incorrect approach. In all systems in which effect has to be given to general standards for limitation review (usually formulated in terms such as "reasonable" and/or "necessary" or "justifiable"), taking account of the elements of proportionality has almost always enabled those who apply the general standards to give effect to those standards in concrete cases without detracting from the values which those general terms embody. The elements of proportionality are taken into account in applying a "reasonableness" requirement in the Indian Constitution43 and the Canadian Constitution,44 and are a "necessary" requirement in respect of certain rights in the European Convention on Human Rights.45 One of the benefits of comparative exercises is that they can reveal that differently worded concepts in different systems could involve the same form of application and often render the same results.46 The concept "proportionality" seems to have been a useful instrument to give effect to broad concepts such as "reasonable" or "necessary" that appear in the formulation of general standards, and even to unarticulated core values embedded in particular legal systems.47 Elements and techniques now known as elements of proportionality seem to have been used since ancient times48 to apply general legal standards to disputes in concrete cases.

Two months later, in S v Makwanyane, the Constitutional Court changed its initial hesitant approach.49 The following statement in the judgment of the president of the Court Chaskalson P formed the foundation of future developments as far as the general limitation clause in the final Constitution is concerned:50

The limitation of constitutional rights for a purpose that is reasonable and necessary in a democratic society involves the weighing up of competing values, and ultimately an assessment based on proportionality. [Footnote 103 of the iudgment: A proportionality test is applied to the limitation of fundamental rights by the Canadian courts, the German Federal Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights. Although the approach of these Courts to proportionality is not identical, all recognise that proportionality is an essential requirement of any legitimate limitation of an entrenched right. Proportionality is also inherent in the different levels of scrutiny applied by United States courts to governmental action.] This is implicit in the provisions of section 33(1). The fact that different rights have different implications for democracy, and in the case of our Constitution, for 'an open and democratic society based on freedom and equality', means that there is no absolute standard which can be laid down for determining reasonableness and necessity. Principles can be established, but the application of those principles to particular circumstances can only be done on a case by case basis. This is inherent in the requirement of proportionality, which calls for the balancing of different interests. In the balancing process, the relevant considerations will include the nature of the right that is limited, and its importance to an open and democratic society based on freedom and equality; the purpose for which the right is limited and the importance of that purpose to such a society; the extent of the limitation, its efficacy, and particularly where the limitation has to be necessary, whether the desired ends could reasonably be achieved through other means less damaging to the right in question. In the process regard must be had to the provisions of section 33(1), and the underlying values of the Constitution, bearing in mind that, as a Canadian Judge has said, 'the role of the Court is not to second-guess the wisdom of policy choices made by legislators'.

4 Proportionality and the general limitation clause in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

The statement of Chaskalson P quoted at the end of paragraph 3 contains features that provide context to the way in which the general limitation clause in the final Constitution was formulated: first, the judge clearly linked proportionality and balancing/weighing; second, the judge emphasised that reasonableness and necessity are general standards to be given effect to in concrete situations; and third, the Court said that the recognised elements of proportionality are considerations to be taken into account in the balancing process.

In order to relate how these features assisted with the formulation of section 36 of the final Constitution, one has to refer to the reasons why certain aspects of section 33 of the interim Constitution were left out and replaced. (The fact that the final Constitution left out the prohibition in the interim Constitution that the essential content of a right shall not be negated, is not discussed in this article.)51

Section 33 of the interim Constitution provided for two tests for limitation. The general test was "reasonableness" and the test for certain specified rights was "reasonableness and necessity". According to Du Plessis and Corder "reasonable" in section 33(1)(a) was supposed to reflect the Canadian test for the application of the reasonableness test in section 1 of the Canadian charter of rights, and "reasonable and necessary" in section 33(1)(b) was a stricter test. The authors explain:

[The Canadian limitation test], amongst others, requires the interest or consideration underlying the limitation of a right to be of sufficient importance to outweigh the ratio for entrenching that right. Applying the stricter limitation test in s 33(1)(c), a South African court which considers the necessity of a limitation could then conclude that a standard stricter than sufficient importance, for instance absolute or compelling or overriding importance, must be invoked to adjudicate the limitation of the right in question. The proportionality test could then follow only once the threshold of necessity has been crossed.52

In principle, it can indeed be accepted as a truism that great injustice can be brought about by judging all limitations in terms of a single standard. This has been a generally accepted principle since the development of different so-called levels of scrutiny in the application of the world's oldest operative Bill of Rights in the Constitution of the United States of America.53 The real problem is how to distinguish instances in which stricter standards should be applied from circumstances in which weaker standards can be applied and how to determine what the contents of those standards should be. However, in drafting and approving section 36 of the final Constitution, the Constitutional Assembly abandoned the formalised so-called bifurcated approach in the interim Constitution, that is the listing of rights in two categories to which different standards of review must be applied. The reasons for doing so pertain both to the formal ranking of rights in order to apply different standards of review to the different categories, and to the meaning and significance that should be attached to the words and phrases that are usually used to describe the general standard of review.

As far as the formal ranking of rights is concerned, it was explained elsewhere that the so-called bifurcated approach was probably abandoned for various reasons.54 First, it is a drastic and rigid measure to constitutionally entrench a fixed list of ranked rights. If in future the "relative importance" of rights should change, the ranking can be altered only by constitutional amendment, whereas such changes can effectively be dealt with by applying a general limitation clause that requires that the nature of the affected right must be investigated. Second, it is extremely difficult to reach agreement on such ranking.55 And third, developing stricter standards to apply to limitation does not depend only on the relative importance of the rights concerned but also, for example, on which aspects of a right are affected and the nature and extent of a limitation. For example, a stricter standard is applied to the invasion of so-called personal inner-sanctum privacy than to the invasion of privacy in respect of business transactions, and to the limitation of the right to personal freedom by incarceration than to the limitation of the same right by a request to stand in a queue to vote or to apply for the renewal of a driver's licence.

Extended debates were conducted during the negotiations on the basis of the feature of the formulation in the interim Constitution that the phrase "reasonable and necessary" describes a stricter test than the word "reasonable". It was assumed that the strictness or otherwise of limitation requirements could for all future purposes be determined by using specific words and phrases. Less than six months before the final constitutional text was adopted on 8 May 1996 consensus had still not been reached on which words to use in the new text. In the Working Draft of the New Constitution of 22 November 1995 published by the Constitutional Assembly for public comment, outstanding issues were referred to in square brackets. The first paragraph of the draft general limitation clause read:

(1) The Rights in the Bill of Rights may be limited by or pursuant to law of general application only to the extent that the limitation of a right is -

(a) [reasonable / reasonable and justifiable / reasonable and necessary / necessary /justifiable] in an open and democratic society based on freedom and equality;

(b) compatible with the nature of the right that it limits; and

[(c) consistent with the Republic's obligations under international law].56

The negotiators apparently changed course when they realised that regardless of which terms are used to define the general standard in various foreign Bills of Rights and other human rights instruments, the effective and meaningful application of all the concepts involved some or other form of proportionality. At the time the Constitutional Assembly realised something which was described much later in the following terms by Andenas and Zlepting:57

It can also be the case that similar tests are given different names, such as necessity, reasonableness, cost-benefit-analysis, or rationality review, and yet their normative requirements may be very similar to the proportionality test.

When time-consuming debates then flared up on the exact meaning of proportionality, the formulation in the Makwanyane case by Chaskalson P of the elements of proportionality became the catalyst that enabled the reaching of consensus on the formulation of section 36(1). The agreement that these elements should form part of the general limitation clause somehow rendered further debates on the exact wording of the general standard and the meaning of proportionality unnecessary. Nobody had serious objections to a requirement that the matters to be taken into account should include the matters referred to by the President of the Constitutional Court. How the elements fit into contemporary theories of proportionality or a construction by any other name became less important.58 The Constitutional Assembly decided that the general standard would read "reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom",59 that the word "proportionality" would not feature in the description, and that a duty must be imposed on everybody who interprets or applies the general limitation clause to take into account the matters referred to in the Makwanyane case, namely the nature of the right, the importance of the purpose, the nature and extent of the limitation and the relation between the limitation and its purposes, and to these "less restrictive means to achieve the purpose" were added. Section 36(1) of the Constitution thus reads:

The rights in the Bill of Rights may be limited only in terms of law of general application to the extent that the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom, taking into account all relevant factors, including -

(a) the nature of the right;

(b) the importance of the purpose of the limitation;

(c) the nature and extent of the limitation;

(d) the relation between the limitation and its purpose; and

(e) less restrictive means to achieve the purpose.

5 Academic objections against the Chaskalson dicta in the Makwanyane case and the formulation of section 36

Academics who before the adoption of the interim Constitution advocated the Canadian approach towards the limitation of rights in great detail were "taken by surprise" and disappointed. They were critical of both the Chaskalson dicta in the Makwanyane case and the formulation in the final Constitution.60 They still are. Despite the global appeal of proportionality as described in paragraph 1 above, these writers are opposed to the concept. As late as 2013 the criticism of De Vos and Freedman included the following:61

(a) The authors state that the Constitutional Court's jurisprudence is based on proportionality or balancing, notwithstanding the fact that proportionality is not referred to in the text. However, despite the fact that the word proportionality hardly features expressly in any foreign or international human rights texts, the concept has gained universal acclaim and is apparently applied almost globally.

(b) The authors state that it is unclear what exactly proportionality requires and that "the term's flexibility lends itself to morally appealing but legally inexact analysis". This is reminiscent of criticism against balancing which Duncan Kennedy describes as regarding balancing "as, at least potentially, a Trojan horse for the invasion of law by ideology".62 They also contend that "[this] confusion is not necessarily inevitable as both reasonableness and justifiability are capable of greater textual certainty".63 However, as is indicated above, there is a fair amount of unanimity on the elements of proportionality, and in following the line of reasoning of Kentridge AJ in the Zuma case, the authors also misconceive the relation between the general concepts in the abstract standards of review and proportionality as an instrument to give effect to the concepts.64 Neither Kentridge AJ nor the authors provide information on the contents of the "textual certainty" of reasonableness and justifiability; and the authors, writing in 2013, do not provide examples of "legally inexact analysis" in the Constitutional Court's jurisprudence of the past 18 years that can be ascribed to the Court's application of section 36(1)(a) to (e).

(c) The authors contend that instead of following the Canadian approach as articulated in R v Oakes,65 the South African approach is based on the vague concept of proportionality. This black-and-white distinction between the Canadian approach and the approach that is followed in section 36 and by the Constitutional Court in applying section 36 is not borne out by the observation of other writers that Canada has been a destination for the migration of the concept of proportionality and an example of how the concept can be applied. According to Cohen-Eliya and Porat the Supreme Court of Canada "embraced the European doctrine of proportionality by interpreting Section 1 of the Charter as including it, and in the years to come proportionality analysis became almost synonymous with constitutional analysis".66 The same writers state: "[Proportionality] travelled from its original birthplace in Germany, through the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), to all of Western Europe and Canada ...." 67

(d) De Vos and Freedman complain that in formulating section 36, the Constitutional Assembly moved away from the interim Constitution and Canadian "structured, sequential enquiry with set criteria to be met to a global singular enquiry with factors to be considered".68 This complaint concerns inter alia firstly the steps to be taken to apply section 36 in general, and secondly, the chronological order in which the steps must be taken. It is of course true that section 36 does not describe the order in which the factors must be considered, and that the only instruction section 33 of the interim Constitution contained in this regard was that the right that has been factually limited must first be classified as a right to which only a reasonableness standard applies or a right to which both a reasonable-and-necessary standard applies. Section 33 of the interim Constitution contained no instruction that American, Canadian, German or Indian steps to apply a Bill of Rights had to be followed. Likewise, section 36 of the final Constitution leaves it to those who apply and review limitations to decide in which order they wish to consider the elements of proportionality or how much weight they must attach to the relevant factors when they do the weighing or balancing. It also does not contain any instruction in respect of which questions concerning elements must be considered on a preliminary basis, that is before a proportionality or balancing exercise is being undertaken. Nothing in the text of section 36 precludes making such distinctions. In this regard it must be noted that although such instructions do not appear anywhere in the German Bill of Rights, a distinction has always been made in Germany between the proportionality elements of legitimacy, suitability and necessity on the one hand, and so-called proportionality in the narrow or strict sense, which involves considering, as stated by Klatt and Meister, "whether the [limitation] represents ... a net gain, when the reduction on enjoyment of rights is weighed against the level of realization of the aim".69 Even in the case of a particular set of steps that has achieved national or international acceptability to determine, for example delictual or criminal liability, or illegality in contract, or for that matter, the constitutional justifiability of the factual limitations of rights, it is unrealistic to accept that universally true and valid templates exist in this regard. The steps taken by persons or institutions always represent a certain level of understanding of the subject matter by both themselves and their audiences, and to a large extent they even represent personal convenience and predilections in respect of what should be considered first and what later.

However, De Vos and Freedman concede that they are faced with the reality that proportionality has become part of the constitutional thinking in South Africa and they therefore also propose certain steps to be taken in the application of section 36.70 They revert to the Canadian procedures. In describing their steps they follow the explanation provided earlier by Woolman and Botha of the Canadian process, namely "... whether the limitation serves a sufficiently important objective, ... whether the limitation is rationally connected to the said objective ... whether the limitation impairs the right as little as possible ... and ... whether the actual benefits of the limitation are proportionate to its deleterious consequences".71 These steps do not include a consideration of the nature of the right, which means that its importance or abstract value in general or for the particular aggrieved party for the purposes of proportionality analysis is not considered. There should also be a more emphatic statement that the relationship between the limitation and its purpose pertains not only to the existence of a rational relationship between the purpose and the limitation but also to other aspects of the relationship such as the extent to which the limitation and the purpose can be achieved.

(e) Finally, De Vos and Freedman contend that "the all-at-once approach [of the Constitutional Court and section 36, in the sense that no specific steps or stages are prescribed] reduced the precedential value by making the balance struck too case-specific".72 This point of criticism ignores certain basic features of the way in which general legal standards defined in terms of general concepts are applied. The general test in the introductory part of section 36 is "reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom". Nowhere has a test of this nature been formulated that is capable of providing a single fit-all standard of review for all factual limitations. As will be explained below, the inclusion of the factors to be considered clearly implies that within the framework of the general test, the Bill of Rights does not provide for a single standard for all limitations. But this need not result in an ad hoc standard for every conceivable limitation. Through the ages and nowhere in the world has standard setting in private law and other fields of public law in terms of general terms such as reasonableness, unlawfulness, appropriateness, the boni mores or public opinion resulted in case-specific outcomes and situational justice without precedential value. While different situations lead to different outcomes as a result of the interplay between some of the factors referred to in section 36(1)(a) to (e), the outcomes in respect of different clusters of situations in respect of the rights or aspects of rights involved, the purposes of limitation involved, and the different ways in which rights may be limited, for example, constitute the substance of creating and sustaining precedents.

6 The relevance of the matters referred to in section 36(1)(a) to (e) for the application of the general test that the limitation must be "reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom"

6.1 Introduction

The limitation of rights in terms of the South African Constitution is governed by two principles: first, that the entrenched rights are not absolute but that they may be limited after the commencement of the Constitution,73 and second, that those who limit rights must comply with the requirements set out in the Constitution.74 This approach is clearly different from approaches that rights are absolute and always trump or overrule any other consideration, or that rights may be limited for whatever purposes and in any way the sovereign legislature or any other state organ considers appropriate, or that only certain expressly listed rights are absolute and the rest may be limited.75

In terms of section 36(1) of the Constitution, the general requirements for the limitation of any right is that it may be limited only in terms of law of general application "to the extent that the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom". The reference to "law of general application" gives effect to the formal aspects of the rule of law or legality, namely that all limitation must be authorised by legal rules.76 In investigating the second part of the general test that refers to the reasonableness and justifiability of a limitation of the right, the factors in section 36(1)(a) to (e) must be taken into account. How is the taking into account of the factors in section 36(1)(a) to (e) supposed to assist us in applying the general standard of "reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom?"

First, to state the obvious, by including the elements of proportionality in the general limitation clause the Constitutional Assembly clearly indicated that it wished proportionality in some or other form to play a role in applying the general standard. The similarities between the generally recognised element of proportionality as described in paragraph 2 above are simply too obvious for anyone to be able to miss this point.

Second, the fact that the matters to be taken into account refer to information about the concrete circumstances of specific limitations that conform to the general standard of "reasonableness and justifiability" does not mean that the requirements for the justification of the limitation are pitched at exactly the same level of strictness for all cases. In a certain sense, the requirements for a particular case are determined by the interplay in a weighing process of the information on matters like those referred to in section 36(1)(a) to (e). This can be illustrated by referring to the so-called first law of balancing formulated by Alexy in his Theorie der Grundrechte.77 This law as articulated by Klatt and Meister78 reads:

The greater the degree of non-satisfaction of, or detriment to, one principle, the greater the importance of satisfying the other.

The principles referred to in this formulation can for our purposes be described as, on the one hand, the right that has been limited and, on the other hand, the interests or rights protected or promoted in terms of the purpose of the limitation. It is clear from this law that depending on the degree of interference with a right by the limitation, the requirements to establish that a limitation is "reasonable and justifiable" would differ. The justification of greater degrees of interference clearly requires more important or more compelling purposes and more certainty (for example, on a scale of possibly, probably or necessary) in respect of the extent to which the limitation will serve the purpose than lesser degrees of interference. As stated by the South African Constitutional Court: "The more substantial the inroad into fundamental rights, the more persuasive the grounds of justification must be."79

It is also clear from the formulation in section 36(1)(a) to (e) that requirements for justification are not prescribed in these paragraphs. They prescribe that certain information must be obtained and considered in order to apply the general standard to a specific case. Proportionality analysis does not replace the general standard that all limitations must be "reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic state based on human dignity, equality and freedom". The latter is not an empty, meaningless phrase. In the final analysis, the information on the matters referred to in section 36(1)(a) to (e) is not needed to perform weighing and balancing for the sake of weighing and balancing as a useful forensic tool. Section 36 requires that the weighing must have a specified substantive outcome, namely an outcome that is justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom, and not in a closed, authoritarian society based on the violation of human dignity, equality and freedom. Is there anyone who can honestly say that she or he does not know the difference between these two kinds of society?

The matters that must be taken into account according to section 36(1)(a) to (e) are analysed in South African handbooks.80 The purpose of the following subparagraph (paragraph 6.2) is to add a few insights gained from the description and discussion by Klatt and Meister of Alexy's weight formula. Only a brief outline of the formula is presented here and it must be emphasised that only a few inferences are drawn. Much more needs to be done in this field.

6.2 The Alexy weight formula and section 36(1) of the South African Constitution

Klatt and Meister81 describe the weight formula as follows:

The greater the product of reliability, intensity of interference and abstract weight of one principle is, the greater must be the product of reliability, intensity of interference and abstract weight of the other principle.

For South African purposes the formula could be adapted to read:

The greater the combined effect of the abstract weight of the right that has been limited, the intensity of the interference with the right and the reliability of empirical information concerning the abstract weight and the intensity is, the greater must be the combined effect of the abstract weight of interests and rights served by the limitation, the intensity on those interests and rights if the measure to limit the right has not been undertaken and reliability of the empirical information concerning the abstract weight and the intensity.82

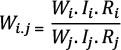

The mathematical expression of the basic weight formula looks like this:

Wi.j stands for the outcome of the weighing process; Wistands for the abstract weight of the right; Wjfor the abstract weight of interests and rights promoted by the limitation; li and Ij for the intensity of interference respectively with the right, and with the purpose of the limitation if the limitation of the right has not been undertaken; Ri and Rj for the reliability of the empirical premises on which conclusions are based in respect of respectively the abstract weight of and interference with the right, and the abstract weight of and interference with the purpose of the limitation.83

"Concrete weight" or "intensity of interference" or "extent of reliability of empirical premises" has inevitably to be located at a certain level somewhere on a scale of respectively "concrete weights", "intensity of interferences" or "reliability of premises".84 A decision has also to be made on how many levels to use, for example, three, namely

- in the case of concrete weight: less important, important and very important;

- in the case of intensity: light, moderate or serious;

- in the case or empirical reliability: certainty, average certainty, or uncertainty (or necessity, probability, or possibility).85

In order to do a calculation, decisions will also have to be taken on the numerical value of these levels, such as 1, 2 and 3. And there is no law that says that these values must be the same for every category of variable above and below the line. Decisions of this nature could, of course, be controversial. Decisions on the number and nature of the levels and the numerical value assigned to the levels are not empirically objective. This fact serves as a sober reminder that the weight formula "is by no means an attempt to replace balancing with a mere calculation".86 However, this does not mean that assigning weight to the variables in the formula is the Achilles heel of the proportionality project. It should rather be seen as the entry point of the socio-economic and political impulses that inevitably form the bases of all legal concepts. The weight formula, like any other instrument or method clothed in technical or "scientific" legal nomenclature, rescues nobody involved with the limitation of rights from taking hard and difficult decisions on what is required in "an open and democratic state based on human dignity, equality and freedom".

The levels of abstraction reached in the debates on the Alexy model can be daunting.87 It is not difficult to predict that South African Courts and practitioners will not be inclined to use the mathematical format of the formula. However, the weight fomula presents a structure in which all the particles of proportionality analysis are comprehensively linked. Valuable lessons can be learned from it when verbalised proportionality templates and structures are developed in particular systems.

For example, one aspect that is clearly "visible" in the mathematical formula is that a limitation is unconstitutional when the combined effect of the factors in respect of the right and the effect of limitation is greater than the combined effect of the factors relating to the purpose of the limitation.88 The mere fact that the abstract weight of the limited right, for instance, is greater than the abstract weight of the public interest or private right that is being protected is not decisive; the higher abstract weight of the right may be neutralised or exceeded by the other variables of the formula.89 It also means that when the weights attached to the importance of the right and the importance of the purpose are considered to be equal, the outcome will be determined by the other variables.90

Against this background the following can be said about the role of information in the determination of the matters referred to in section 36(1)(a) to (e) of the Constitution. In doing so, it must be noted that because section 36(1) provides that all of the relevant factors must be taken into account, matters covered in the German weight formula and not in the South African application can always be added to a South African template; and, as will be pointed out below, in taking account the factors in section 36(1)(a) to (e) the South African Courts have in certain instances covered matters differently from the way in which they are being dealt with in the variables of the German model.

Although the protective ambit of a right as an aspect of the nature of the affected right (section 36(1)(a)) must be determined in the first phase of a Bill of Rights inquiry to determine whether the right has been factually limited or not, an evaluation has to be made of the importance of the right relative to other rights for the purpose of the proportionality analysis. In applying section 36, South African Courts always pay attention to the importance of the right by referring to how important it is in an "open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom". It is always concluded that the right is very important, which is not surprising, because that, after all, is why it was entrenched in the Bill of Rights.

The abstract importance of the affected right relative to other rights must be distinguished from that importance relative to the importance of the purpose of the limitation, which may include the exercise, protection or promotion of another individual right (for example, in the context of the law of delict or the law of contract). The latter is an aspect of the weighing of colliding rights. In this regard, Klatt and Meister comments as follows:

The abstract weights of colliding human rights are often equal, and then, can be disregarded in balancing. Sometimes, however, the abstract weights of the colliding principles are not equal. The right to life, for example, has a higher abstract weight than the right to property.91

In South Africa the nature of the right also refers to a particular aspect of the right that has been limited, and in this regard different weights can indeed be accorded to different aspects of the right to property,92 for example, and the right to freedom of expression.93 The nature of the right also refers to the nature of the bearer of the right in that particular case. Whether the bearer is a natural or juristic person could, for example, in the case of the right to privacy, influence the strictness of the standard.94

The importance of the purpose of the limitation (section 36(1)(b)) constitutes the abstract weight of the interests and rights that the limitation protects or promotes. A legitimate purpose must be protected or promoted and the actions to execute the limitation must thus fall within the powers of the person or institution that limits the right.95 The legality of the limiting law or action is, of course, also covered by the requirement in the introductory part of section 36(1), that a limitation must be "in terms of law of general application", and it is therefore sometimes considered not to form part of the "proportionality in the narrow sense" which forms the focus of the German formula. However, as far as this proportionality in the narrow sense is concerned, it is important to note that the importance of the purpose of the limitation involves more than mere formal legality or formal infra vires. The purpose of the limitation refers also to the benefit that can be achieved by limiting the right and the importance of achieving that benefit in an "open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom". In this sense, the mere exercise of a legitimate power or a legal competence is not the purpose that must be noted for balancing purposes;96 the importance of the purposes for which such powers and competences are exercised must be determined.

The nature and extent of the limitation (section 36(1)(c)) refers to information on how intrusive the limitation was in respect of the conduct and interests that are protected by the right - the intensity of the limitation, in the German model. It is always recorded in South African Court judgments on the limitation of rights. The nature of a limitation also relates to the methods and instruments used to limit the right. A discretion to limit rights in an authorising law forms part of the methods to limit rights. The extent of a limitation may therefore be influenced by the width or narrowness of the discretion. At the same time, whether a narrow or wide discretion to limit rights is constitutionally permitted in a particular case could depend on how seriously a right may be affected by the limitations that may be imposed. The extent of a discretion to limit rights therefore forms part of the nature and extent of a limitation.97 In the German weight model, the counterweight to the intensity of the limitation consists of the intensity of the negative effect of not imposing the limitation on the protection and promotion of the interests or rights. In the South African general limitation clause, information in this regard is covered by the information on the relation between the limitation and its purpose, derived by asking (as is indicated below) what, if any, positive effect imposing the limitation is going to have on the protection and promotion of the purpose of the limitation.

Information on the relation between the limitation and its purpose (section 36(1)(d)) relates to whether the limitation is capable of making a contribution to the achievement of the purpose (the so-called rational relationship test) and, if it does, what the extent of the contribution is. If the limitation is not capable of furthering the purpose, it is unconstitutional. In its most basic form it is the weakest test that can be applied to the limitation of a right. However, it is extremely important to note that although the rational relationship test in its basic form is a requirement for all limitations (and thus forms part of the general standard of "reasonableness and justifiability")98 and although there could be instances in which a consideration of all the factors in section 36(1) could lead to a conclusion that only a rational relationship test must be applied, stricter requirements can and must be added, to apply a stricter test if required by the nature of the right involved and the nature and extent of the limitation.99 The relation between the limitation and its purpose thus involves more than information on compliance with the rational relationship test in its most basic form. All aspects of how a limitation promotes the purposes must be recorded. If the purpose is served only marginally, it stands to reason that (for the purposes of the German weight formula) not having imposed the limitation would have hampered only slightly the purpose of the limitation;100 and if the purpose is served substantially, not having imposed the limitation would mean that the intensity of the negative effect on the purpose would have been serious.

Information on less restrictive ways to achieve the purpose (section 36(1)(e)) relates to the proportionality element that when there are two or more suitable ways of furthering the purpose of a limitation effectively, the one that interferes less intensively with the right that is to be limited, must be chosen.101 Alternative ways of limiting as effectively the right for the same purpose must be taken into account.102 The range of permissible options that the person or institution who limits rights may choose from also determines the strictness or otherwise of the test that is applied in a particular case. The extent of what Klatt and Meister call "means selecting discretion" is limited not only by the consideration that the alternatives must be as effective as the impugned measures, but also by the fact that all of the available alternatives must be constitutional in the sense that all of them must pass all of the other constitutional requirements for limitations. To the extent that it can be argued that "reasonable and justifiable" means that a limitation must be proportionate to the purpose of the limitation, it is unthinkable that a discretion to limit could on any basis whatsoever mean that the permissible range of options to choose from includes ways of limiting rights that are otherwise unconstitutional. As has been stated elsewhere, the number of constitutionally permissible alternatives in the range of alternatives determines the extent of the discretion to limit rights, the "margin of appreciation", the limits of a strict separation of powers, and the judicial deference towards and respect for the expertise and responsibilities of those who limit rights.103

Schlink describes the problems concerning the reliability of information in the proportionality analysis (Ri and Rj in the Alexy formula) as follows:

The fitness and the necessity of a means is an empirical problem, and often science, scholarship, and experience can help in solving it. But often all one has are assumptions, contradictory experiences, and as many expert opinions as there are interests involved. Climate change is an example. Beyond basic agreement that climate change is dangerous and has to be countered, information about the extent of the dangers and the effectiveness of the countermeasures is ambiguous and insufficient.104

Schlink submits that the problem can be solved by the rules of onus of proof.105 In South Africa applicants who allege that their right has been violated or threatened bear the onus to adduce evidence to that effect, whereas those who rely on compliance with the requirements for the factual limitation of the right bear the onus of proving the necessary facts.106 However, the mere location of the onus does not tell us which level of reliability of the information concerning certain variables in the Alexy formula is required to dispose of the onus. Alexy's second law of balancing (as reformulated by Klatt and Meister,107 and with italicised phrases added by me in square brackets for the convenience of South African readers) reads that "[t]he more serious an interference with a principle [a right affected or the interest or right protected by the limitation] is, the more certain must be those premises that justify the classification of intensity of interference [if the right has not been limited]". This means that for the purposes of supplying information on the relation between the limitation and its purpose in section 36(1)(d), the level of reliability of the information on the extent to which the limitation is capable of furthering the purpose (certainty, probability, possibility) provided by the person or institution who limits the right is determined by the nature and extent of the limitation. It can certainly also be influenced by the nature of the right and the importance of the purpose of the limitation.

7 The elements of proportionality and the limitation of specific rights

In paragraph 2 above, reference is made to the phenomenon that the South African Bill of Rights contains provisions that deal with the limitation of specific rights and that these provisions either qualify certain features of the general limitation clause or merely reiterate them. No discussion of the role of proportionality in South African limitation of rights analyses can be complete without a brief reference to the role of proportionality analysis in applying such provisions. Although the South African Courts often fail to recognise these provisions as dealing with the limitation of the rights concerned and consequently deal with them as if they form part of the description of the conduct and interests protected by the right or the duties imposed by the right, the judgments of the Courts clearly reveal that they apply elements of proportionality when they are applying the particular words and phrases.108 Dealing with the limitation of these rights in this way sometimes unfortunately results in a rather haphazard review of the limitation of the rights concerned.

The following are a few examples. The Constitutional Court held that section 9(1) of the Constitution requires that differentiation that does not amount to unfair discrimination must be rationally related to the purpose of the differentiation and that an enquiry in this regard belongs to the first stage of a Bill of Rights investigation.109 However, the existence of a rational relationship between the differentiation and its purpose is a matter covered by section 36(1)(d). It is the weakest test that can be applied to the limitation of a right,110 and the general limitation clause need not be applied after a Court has found that no rational relationship exists in a particular case.111 The Constitutional Court also works with proportionality during the first stage of the enquiry to determine if a deprivation of freedom was undertaken "arbitrarily and without just cause" in applying section 12(1)(a) of the Constitution, but nevertheless endeavours to consider the matters referred to in section 36(1)(a) to (e) after it has concluded that there was an arbitrary deprival without just cause.112 The elements of proportionality are also considered when the Constitutional Court applies the concept "arbitrary" in the provision in section 25(1) that "no law may permit the arbitrary deprival of property";113 when the Court reviews the justification by the state that it has taken "reasonable and other measures within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of these rights" when it failed to provide access to adequate housing and to health care services, sufficient water and food and social security in sections 26(1) and 27(1) of the Constitution;114 and when the Court applies the concept "reasonable" in the right to administrative action that is lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair in section 33 of the Constitution.115

8 Concluding remarks

Despite some opposition from certain academics, proportionality is a prominent feature of the application of the limitation clauses in the South African Constitution. South Africa therefore participates fully in the global recognition and application of this mode of approaching the limitation of rights. On the merits of doing so, the following statement of Klatt and Meister seems to be appropriate:

All in all, proportionality is a structured approach to balancing fundamental rights with other rights and interests in the best possible way. It is a necessary means for making analytical distinctions that help in identifying the crucial aspects and considerations in various cases and circumstances and ensuring a proper argument.116

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Literature

Alexy R Theorie der Grundrechte (Suhrkamp Frankfurt am Main 1986) [ Links ]

Alexy R "Die Konstruktion der Grundrechte" in Clerico L and Steckmann J-R (eds) Grundrechte, Prinzipien und Argumentation (Nomos Baden-Baden 2009) 9-20 [ Links ]

Alexy R "Ideales Sollen" in Clerico L and Steckmann J-R (eds) Grundrechte, Prinzipien und Argumentation (Nomos Baden-Baden 2009) 21-38 [ Links ]

Andenas M and Zlepting S "Proportionality: WTO Law in Comparative Perspective" 2007 Tex Int'l LJ 370-423 [ Links ]

Beatty D (ed) Human Rights and Judicial Review (Nijhoff Dordrecht 1994) [ Links ]

Cohen-Eliya M and Porat I Proportionality and Constitutional Culture (Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2012) [ Links ]

Currie I and De Waal J The Bill of Rights Handbook 6th ed (Juta Cape Town 2013) [ Links ]

De Vos P and Freedman W (eds) South African Constitutional Law in Context (Oxford University Press Cape Town 2013) [ Links ]

Du Plessis LM "The Genesis of the Chapter on Fundamental Rights in South Africa's Transitional Constitution" 1994 SAPL 1-21 [ Links ]

Du Plessis L and Corder H Understanding South Africa's Transitional Bill of Rights (Juta Kenwyn 1994) [ Links ]

Gröpl C Staatsrecht I (Beck Munchen 2012) [ Links ]

Grünberger M "Das Prinzip der Personalen Gleichheit. Eine Skizze des Rechtfertigungsmodells von Gleichbehandlungspflichten Privater Akteure" in Ast S et al (eds) Gleichheit und Universalität (Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart 2012) 93-106 [ Links ]

Iacobuccu F "Judicial Review by the Supreme Court of Canada under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms: The First Ten Years" in Beatty D (ed) Human Rights and Judicial Review (Nijhoff Dordrecht 1994) 93-134 [ Links ]

Jarass H and Pieroth B Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland 10th ed (Beck München 2009) [ Links ]

Keller H and Stone Sweet A (eds) A Europe of Rights (Oxford University Press Oxford 2008) [ Links ]

Kennedy D "Transnational Genealogy of Proportionality in Private Law" in Brownsword R et al (ed) The Foundations of European Private Law (Hart Publishing Oxford/Portland 2011) 185-220 [ Links ]

Klatt M and Meister M The Constitutional Structure of Proportionality (Oxford University Press Oxford 2012) [ Links ]

Kumm M "Who is Afraid of the Total Constitution? Constitutional Rights as Principles and the Constitutionalization of Private Law" 2006 GLJ 341-369 [ Links ]

McIntosh E, Fowler HW and Fowler FG The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English 4th ed (Oxford University Press Oxford 1959) [ Links ]

Mureinik E "A Bridge to Where? Introducing the Interim Bill of Rights" 1994 SAJHR 31-48 [ Links ]

Pieterse M "Constructing freedom jurisprudence" 2001 SALJ 87-101 [ Links ]

Rautenbach IM "The Limitation of Rights in terms of Provisions of the Bill of Rights Other than the General Limitation Clause: A Few Examples" 2001 TSAR 617-641 [ Links ]

Rautenbach IM "Introduction to the Bill of Rights" in Anonymous Bill of Rights Compendium [Issue 29] (LexisNexis Durban 2011) 1A1-1A319 [ Links ]

Rautenbach IM Rautenbach-Malherbe Constitutional Law 6th ed (LexisNexis Durban 2012) [ Links ]

Reddy B and Dhavan R "The Jurisprudence of Human Rights" in Beatty D (ed) Human Rights and Judicial Review (Nijhoff Dordrecht 1994) 175-226 [ Links ]

Sachs M Grundgesetz 5th ed (Beck Munchen 2009) [ Links ]

Sacco R "Legal Formants: A Dynamic Approach to Comparative Law" 1991 AJCL 1-34, 343-401 [ Links ]

Schlink B "Proportionality in Constitutional Law: Why Everywhere but Here" 2012 Duke J Comp & Int'l L 291-302 [ Links ]

Stern K Das Staatsrecht der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Vol 1 2nd ed (Beck Munchen 1984) [ Links ]

Van Dijk P and Van Hoof GJH Theory and Practice of the European Convention on Human Rights (Kluwer The Hague 1998) [ Links ]

Von Münch I and Kunig P Grundgesetz - Kommentar 5th ed (Beck München 2000) [ Links ]

Weaver R Constitutional Law: Cases, Materials and Problems 2nd ed (Aspen New York 2011) [ Links ]

Woolman S and Botha H "Limitation" in Woolman S, Bishop M and Brickhill J (eds) Constitutional Law of South Africa 2nd ed (Juta Kenwyn 2007) ch 34 [ Links ]

Case law

Bato Star Fishing (Pty) Ltd v Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism 2004 4 SA 490 (CC)

Bernstein v Bester 1996 2 SA 751 (CC)

Bobroff v De la Guerre (CC) unreported case number CCT 122/13 and CCT 123/13 of 20 February 2014

Bredenkamp v Standard Bank of SA Ltd 2010 9 BCLR 892 (SCA)

Dawood; Shalabi; Thomas v Minister of Home Affairs 2000 3 SA 47 (CC)

De Lange v Smuts 1998 3 SA 785 (CC)

First National Bank v CIR: First National Bank v Minister of Finance 2002 4 SA 768 (CC)

Gaertner v Minister of Finance 2014 1 BCLR 38 (CC)

Government of the RSA v Grootboom 2001 1 SA 46(CC)

Harksen v Lane 1998 1 SA 300 (CC)

Investigating Directorate: Serious Economic Offences v Hyundai Motor Distributors (Pty) Ltd 2001 1 SA 545 (CC)

Jooste v Score Supermarket Trading Co 1999 2 SA 1 (CC)

Khosa; Mahlaule v Minister of Social Development 2004 6 SA 505 (CC)

Law Society of South Africa v Minister for Transport 2011 1 SA 400 (CC)

Malachi v Cape Dance Academy International (Pty) Ltd 2010 6 SA 1 (CC)

Minister for Welfare and Population Development v Fitzpatrick 2000 3 SA 422 (CC)

Minister of Health v TAC (1) 2002 5 SA 703 (CC)

Moise v Transitional Local Council of Germiston 2001 4 SA 491(CC)

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice 1999 1 SA 6 (CC)

Ngewu v Post Office Retirement Fund 2013 4 BCLR 421 (CC)

North and Central Council v Roundabout Outdoors (Pty) Ltd2002 2 SA 625 (D)

Prince v President of the Law Society of the Cape of Good Hope 2002 2 SA 794 (CC)

Prinsloo v Van der Linde 1997 3 SA 1012 (CC)

R v Oakes 1986 1 SCR 103

S v Bhulwana; S v Gwadiso 1996 1 SA 388 (CC)

S v Makwanyane 1995 2 SA 642 (CC)

S v Williams 1995 3 SA 632 (CC)

S v Zuma 1995 4 BCLR 401 (CC)

Soobramoney v Minister of Health, KwaZulu Natal 1998 1 SA 765 (CC)

Transnet Ltd v SA Metal Machinery Co 2006 4 BCLR 473 (CC)

Uniting Reformed Church De Doorns v President of the RSA 2013 5 BCLR 573 (WCC)

Legislation

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 200 of 1993

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AJCL American Journal of Comparative Law

Duke J Comp & Int'l L Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law

GLJ German Law Journal

SAJHR South African Journal on Human Rights

SALJ South African Law Journal

SAPL SA Publiekreg/Public Law

Tex Int'l LJ Texas International Law Journal

TSAR Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg

1 Klatt and Meister Constitutional Structure 1-2; Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 1-2.

2 Klatt and Meister Constitutional Structure 1-2.

3 Schlink "Proportionality" 302.

4 Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionaiity 2.

5 For bibliographies see Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionaltty 2 fn 3 and Klatt and Meister Constitutional Structure 2 fn 19.

6 Also see Schlink "Proportionality" 294-296; Stern Staatsrecht 861-867.

7 Alexy Theorie. See para 6.2 below.

8 The criticism levelled against balancing by Woolman and Botha "Limitation" must be read in conjunction with the thorough historical, political and cultural analysis of Cohen-Eliya and Porat. The criticism is countered effectively by Klatt and Meister Constttutional Structure 55-66 in their discussion of similar points of criticism raised by other writers. The differences and similarities between proportionality and balancing and debates in this regard are not covered in this article.

9 Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 3 note that the concept has also travelled to South Africa and on 13 they refer to S v Zuma 1995 4 BCLR 401 (CC) (see para 3 below); Klatt and Meister Constitutional Structure 18 refer to the general limitation clause "in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996, s 5 (sic)". The general limitation clause is contained in s 36 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

10 McIntosh, Fowler and Fowler Concise Oxford Dcctionary 963, sive "proportion".

11 See Grópl Staatsrecht 124: "Das vom Staat eingesetzte Mittel ... darf im Hinblick auf den damit verfolgten Zweck nicht 'masslos' (unverhältnismässig) sein."

12 Translation by Schlink "Proportionality" 294.

13 Schlink "Proportionality" 294. See also Stern Staatsrecht 863; Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 25.

14 Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionaiity 106.

15 In stating that the role of balancing in legal reasoning is controversial, Kennedy "Transitional Genealogy" 189 distinguishes two main approaches. The first is that balancing is a technique of "last resort" - "[w]e balance when there is a gap, or conflict or ambiguity in legal materials ..." -and the second is "that particular pieces of legal reasoning 'abuse deduction' or precedent or teleology, and that the only plausible explanation of the outcome is covert balancing".

16 The fact that the outcome of contests often leaves "losers" dissatisfied forms one of the bases of appeal systems and a right to appeal in criminal and civil proceedings. Kennedy "Transitional Genealogy" 190 has a different take on this: "In balancing, we understand ourselves to be choosing a norm (not choosing a winning party) among a number of permissible alternatives on the ground that it best balances or combines conflicting normative considerations." He then constructs the relevancy of the position of the parties involved by explaining that the normative considerations "vary in strength across an imagined spectrum of fact situations". How choosing the best balancing norm to deal with the space occupied by the contestants and their rights and interests in the imagined spectrum without eventually "choosing a winning party" is not clear.

17 See Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 149 and the contribution of Kennedy "Transitional Genealogy".

18 Kennedy "Transitional Genealogy" 218-219.

19 Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 111-113. Other explanations for the spread of proportionality include, according the authors (104-111), that it is useful for young democracies, that it is useful for the resolution of conflicts in divided societies, and that it provides a crossborder lingua franca for legal communities. They find these explanations wanting because the principle is as useful in so-called old democracies and in more or less homogeneous societies, and regressive concepts based on eg authoritarianism and racial superiority could as such also form part of an international lingua franca in certain societies and states. Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 111-112 refer to Mureinik 1994 SAAJHR 10 as one of the sources of the term "culture of justification".

20 Andenas and Zlepting 2007 Tex Int'l LJ 386. Also see Beatty Human Rights 16, who says that Bills of Rights entrench "basic principles of rationality and proportionality - of necessity and consistency - into the framework of government".

21 Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionaiity 2.

22 Klatt and Meister Constitutional Structure 8 fn 9.

23 Kumm 2006 GLJ 349.

24 Klatt and Meister Constitutional Structure 8-9; Cohen-Eliya and Porat Proportionality 2; Gröpl Staatsrecht 124-125; Stern Staatsrecht 866. According to the reconsideration of proportionality by De Vos and Freedman Constitutional Law 363-364, only the last element is called "proportionality". They regard the others as threshold matters.