Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versão On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.17 no.4 Potchefstroom 2014

ARTICLES

The potential of capstone learning experiences in addressing perceived shortcomings in LLB training in South Africa

G QuinotI; SP van TonderII

IBA LLB LLM MA(HES) LLD; Professor, Department of Public Law and University Teaching Fellow, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: gquinot@sun.ac.za

IIBA BA(Hon) BEd MEd PhD HED; Senior Lecturer, School of Higher Education Studies, University of the Free State. E-mail: vtondersp@ufs.ac.za

SUMMARY

Current debates about legal education in South Africa have revealed the perception that the LLB curriculum does not adequately integrate various outcomes, in particular outcomes relating to the development of skills in communication, problem solving, ethics, and in general a holistic view of the law in practice. One mechanism that has been mooted as a potential remedy to this situation is capstone courses, which will consolidate and integrate the four years of study in the final year and build a bridge to the world of practice. A literature review on capstone courses and learning experiences (collectively referred to as capstones) indicates that these curriculum devices as modes of instruction offer particular pedagogical advantages. These include inculcating a strong perception of coherence across the curriculum and hence discipline in students, providing the opportunity for students to reflect on their learning during the course of the entire programme, creating an opportunity to engage with the complexity of law and legal practice, and guiding students through the transition from university to professional identity. An empirical analysis of the modes of instruction used in LLB curricula at 13 South African law faculties/schools indicates that there are six categories of existing modules or learning experiences that already exhibit elements of capstone-course design. These are clinics, internships, moots, research projects, topical capstones and capstone assessment. A further comparative study into foreign law curricula in especially Australia and the United States of America reveals four further noteworthy approaches to capstone-course design, namely problem-based learning, the virtual office, conferences and remedies courses. The empirical study suggests that capstones indeed hold the potential as learning experiences to address some of the challenges facing legal education in South Africa but that further development of this curriculum-design element is required.

Keywords: Legal education; LLB; capstone course; capstone learning experience; curriculum; curriculum design; comparative education; content analysis.

1 Introduction and background

In recent years there has been consistent criticism of the quality of LLB graduates, in particular relating to skills development.1 Angelo Pantazis2 thus recently declared, "There is no doubt that, generally, the quality of the LLB in South Africa is of an unacceptably low standard." Most recently, such criticism has led to talk of a "crisis" in legal education in South Africa, resulting in a national summit involving all stakeholders in legal education held in May 2013 to discuss these issues under the banner "Legal Education in a Crisis?"3 One of the key issues of concern in these debates is the lack of integration between various outcomes of the LLB curriculum. These include skills in communication, problem solving, ethics and, in general, a holistic view of the law in practice.4

Parallel to these quality concerns, the legal services market is facing particular challenges both in South Africa and abroad. In England and Wales, for example, an extensive Legal Education and Training Review is currently underway. This is the most significant review of legal training in that jurisdiction since the early 1970s. It is a response to what is perceived as "an unprecedented period of change, which has the potential over the next two decades to transform the shape of the legal services market".5 In South Africa the debate on the future shape of and approach to legal services is currently taking place around the Legal Practice Bill B20B-2012. The Bill states that its purpose is "[t]o provide a legislative framework for the transformation and restructuring of the legal profession". It envisions the most significant overhaul of the legal services market in South Africa in many decades. The Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development accordingly declared that "[t]he legal profession as a whole is on the threshold of maior changes with the imminent finalisation of the ... Bill"6, and the Minister described it as "a milestone in the history of the profession".7

The purpose of this article is not to debate the problems perceived in legal education or the challenges that legal education faces. That there are such perceived problems and that major challenges exist are taken as points of departure here. The obvious question in response to this point of departure is how legal education should or at least could respond to the problems and challenges. The purpose of this contribution is to focus on one potential curriculum mechanism, namely capstone courses and learning experiences (collectively referred to as capstones) as modes of instruction with which to address some of the perceived problems in legal education. This article thus simply explores the possibility that one type or mode of instruction can generate learning experiences that may help address some of the perceived shortcomings in particular attributes of current LLB graduates.

In their joint press statement announcing the LLB Summit of May 2013, the South African Law Deans Association (SALDA), the Law Society of South Africa (LSSA) and the General Council of the Bar (GCA) already alluded to capstones as a potential mechanism to address some of the problems currently perceived in South African legal education.8 This article takes a scholarly look at capstones and asks to what extent capstones in the LLB curriculum may offer potentially useful learning experiences to counter some of the perceived problems in legal education.

Capstones may take many forms. An entire course can be designed to be a capstone experience. Alternatively a capstone experience may form only part of a course. A capstone experience may also exist outside of a formal course such as a freestanding capstone assessment or a capstone research project. Capstones are in essence a learning experience in the final year of undergraduate study in which the learning of the entire programme is integrated with an emphasis on the application of the knowledge acquired in authentic learning designs.9

2 Methodology

The research involved a qualitative design supported by a quantitative element. This resulted in a limited mixed-method qualitative and quantitative empirical and comparative survey. The potential of capstones was considered in the light of the literature on capstones. The main question asked in this part of the article, the literature review, was what the pedagogical advantages of capstones as learning experiences were.

In the second part of the research, the curricula of LLB programmes at a number of South African universities were analysed in order to ascertain if any courses presently offered in South African legal education provide capstone learning experiences. All South African universities with law faculties/schools (17) were invited to participate in this study, and 13 (76%) agreed. Because of ethical considerations pertaining to a possible reputational risk for participating institutions, only the curricula of those faculties/schools that consented to participate in the study were analysed, and on the condition of anonymity. The nature, scope and status of the courses found with capstone characteristics were analysed in the light of the literature review and the results reported here.

The same comparative analysis of learning experiences was done in respect of a number of targeted foreign law schools. An initial screening of curricula of law programmes in the United Kingdom (UK) (4 programmes), India (5 programmes), the United States of America (USA) (16 programmes), Canada (4 programmes) and Australia (4 programmes) showed that the USA and Australia provided the best examples to serve as exemplars, for the reasons set out in the discussion of the foreign comparison below. The subsequent, more detailed comparative analysis of the curricula of the law programmes in the USA and Australia generated very few further insights beyond what was found in the analysis of the South African programmes. It was only the published results of the recent Australian study on the use of capstones in legal education that provided useful further information.10 Only these latter findings are thus reported in this article.

The methodology adopted in this foreign comparative part is not in the "lending and borrowing" tradition, which aims to identify particular educational practices in foreign education systems that can be transplanted to the home country.11 Instead, the approach here puts forward the capstone practices found in foreign systems of legal education as simply exemplars from which South African legal educators can draw inspiration in developing local learning experiences in legal curricula. The differences in contexts between the systems compared were duly taken into account. The comparison was restricted to legal systems of which the approach to legal education and curriculum was largely comparable.

In all instances the analysis of the curriculum started with the published curriculum of the law programme of each institution. Further details were subsequently requested from the relevant law faculty/school on particular modules.

3 Pedagogical advantages of capstones

The literature on capstones identifies a range of pedagogical advantages of the learning opportunities created by these courses and learning experiences in higher education in general. In addition, when one brings these advantages to bear on legal education in particular, a number of further advantages emerge.

3.1 An analysis of the literature

Capstones have long been utilised in higher education and for a number of purposes.12 The literature on capstones is thus vast and stretches across a broad range of disciplines. In some areas of higher education, capstones are common (such as in mass communication and journalism programmes,13 and in engineering),14 while in others (such as law) they are only now emerging.15 As can be expected, there are many areas of disagreement and contention within the capstone literature. Even the definition of a capstone is not unproblematic. For example, it is not universally accepted that capstones must necessarily be located in the final year of a course of study,16 even though capstones are usually understood as final-year experiences.

As a mode of instruction that creates a particular type of learning experience, the key characteristics of the capstone concept, as explored below, are more important for present purposes than the form they may take. Capstones may exist as single exit-level courses drawing on prior learning. Alternatively the capstone experience may be spread out over different courses or learning activities. It need not necessarily be structured in a traditional module, but may involve more informal activities such as engagement within a community or work environment.

Capstones can be defined as

a crowning course or experience coming at the end of a sequence of courses with the specific objective of integrating a body of relatively fragmented knowledge into a unified whole. As a rite of passage, this course provides an experience through which undergraduate students both look back over their undergraduate curriculum in an effort to make sense of that experience and look forward to a life by building on that experience.17

The two key characteristics of capstones are evident in this definition. Kift et al18 effectively capture these two characteristics when they describe capstone experiences as referring

to the overall student experience of both looking back over their academic learning, in an effort to make sense of what they have accomplished, and looking forward to their professional and personal futures that build on that foundational learning.

This Janus-like nature of capstones serves primarily two functions, namely those of student development and assessment.19

3.1.1 Capstones supporting student development

As a student development tool, capstones aim to consolidate a student's undergraduate training and prepare him/her for employment. In this function, capstones also play an important role in graduate identity forming, both in terms of graduate development within the particular discipline and socialisation into the relevant profession.20

3.1.1.1 Capstone as a "cap"

The conscious and reflective consolidation of a student's undergraduate training is one of the most important advantages of capstones. It involves reflection on the whole programme or discipline. This includes reflection on the integration of different individual components such as various subfields of substantive disciplinary knowledge, methods and skills (typically encountered in distinct modules during the course of the programme).21 Some scholars take this aspect of capstones even further and include reflection on the relationship of the particular discipline with other disciplines22 and with society.23

This is a characteristic of capstones that sets them apart from other learning experiences that may seem very similar, such as internships.24 Unlike many of these other final-year experiences, the capstone is thus not simply aimed at creating an opportunity to apply competences gained in other modules in authentic settings. The capstone itself is aimed at developing new insights into the discipline. It particularly focuses on the integration of various elements of the discipline as well as the relationship between the discipline and other fields and society.25 This may involve introducing students to new materials in order to make the linkages explicit.26 In this regard, Durel talks of the "attainment of higher-order knowledge".27

Apart from its intrinsic value, the consolidating and integrative function of capstones also instrumentally brings about a number of benefits. One of these values is to enable engagement with the emergent properties of the discipline flowing from the interaction between the distinct elements (subfields of knowledge, methods and skills) studied in the relevant programme. This is a very useful pedagogical benefit flowing from capstones when one considers the complexity at stake in disciplinary study. Disciplines by and large study complex phenomena.28 It follows that programmes should consciously try to inculcate in students the limits of studying distinct elements of a particular complex phenomenon in distinct modules (and a single discipline). Programmes should also instil an awareness of the role of emergent properties of the phenomenon flowing from the interaction between the various elements.

Take the study of law as an example. Law can be seen as a complex system.29 It is, however, traditionally studied by breaking it down into various constitutive parts, such as criminal law, contract law and labour law, and studying those in distinct modules. A student may consequently fail to recognise that the way in which the rules of these distinct fields influence behaviour in a particular scenario may be as much a result of the interaction between the rules of the various subfields as the applicable rules of each particular field. For example, role-players' behaviour in a case of theft in the civil service may be as much an outcome of the interaction between the rules of criminal law, contract law, labour law and administrative law as it is determined by the rules of any of these fields in particular. There is thus an emergent property to the law flowing from the interaction between the rules in the subfields. This can be grappled with only when subfields are viewed together in the context of the authentic application. The example can be extended to show how the interaction between legal rules and objects of study in other disciplines such as economics, criminology or industrial psychology may further influence behaviour.

It is, however, not only the objects of disciplinary study that are often complex, but disciplines themselves can be viewed as complex systems.30 A discipline itself will have emergent properties flowing from the relationships between the various elements or parts constituting the discipline. The way in which content knowledge is structured within a discipline influences the content as much as the content may form the basis of the structure. Thus the structure of the discipline influences content, but the structure is at the same time based on the categorisation of the content. Both the system of knowledge and the content of a discipline in turn interact with the accepted methodology/ies of the discipline. Studying content knowledge only within the set systemisation of the discipline without engaging with the interaction between content, system and methodology may fail to reveal the dynamic nature of the discipline resulting from the interaction between these elements of the discipline. Capstones are important in a complexity paradigm to facilitate engagement with relational aspects within the discipline. Additionally, they facilitate engagement with the relationship of a discipline with its environmental context (as will become evident below), for example the professional practice of that discipline, as in the case of law and legal practice.

The integrative and synthesising characteristic of a capstone, that is its deliberate attempt at bringing together the core learning of the preceding undergraduate curriculum,31 has a second instrumental benefit. This is the effect of sharply focusing the attention on the programme outcomes and graduate attributes pursued in the particular programme. When a programme is capped by such an integrative and synthesising final-year experience, programme designers are forced to reflect on what the core outcomes of the programme are. This cannot occur only in vague generic terms for the purpose of formulating a (sometimes grandiose) statement of graduate attributes, but must also occur in real, practical terms to serve as the basis for designing a particular module or learning experience. Henscheid32 captures this very well when she describes capstones in the context of USA higher education as "where American colleges and universities may be collectively telling their students, it all comes down to this... " Having a capstone thus forces a precise formulation of the "this" that the programme "comes down to".

In this benefit, capstones can serve an important function in facilitating constructive alignment between teaching/learning activities, assessment tasks and outcomes. Constructive alignment calls for curricula to be structured in such a way that the assessment tasks aim to gauge a student's competence as expressed in the intended learning outcomes following completion of a set of teaching/learning activities.33

3.1.1.2 Capstone as a "bridge"

Capstones are not only about consolidating preceding learning and thus generating backward-looking reflection. They also have forward-looking pedagogical advantages. In this respect capstones recognise that final-year students are also "students in transition". They require particular assistance to navigate the progression from undergraduate university life to working and/or professional life or postgraduate study.34 Capstones can thus serve to provide closure on the undergraduate experience and socialise students into the relevant profession.35 To achieve this purpose, capstones must include authentic learning of some type, although it need not necessarily be in the form of work-integrated learning (WIL). There is, however, limited empirical evidence suggesting that capstones that incorporate some dimension of WIL may result in better development of certain graduate attributes pertaining to professional development than simulated activities.36

Of importance here is not simply preparing and guiding senior students for entrance into the world of work. It is also about inculcating recognition of the importance of and to develop a capacity for lifelong learning. In this way capstones do not simply serve to deliver students from the undergraduate experience into the world beyond. They also create the link between these two worlds.37

On the one hand, capstones show students how their undergraduate training relates to their profession. That is how reliance on their prior learning enables them to function in a professional setting. On the other hand, capstones serve to make students aware of the limits of their prior learning in respect of a career span. This conveys the need to retain the link to their training by never ceasing to be students.

A capstone furthermore provides students with the basis for such continued learning.38 These two benefits of capstones are also not mutually exclusive. The literature suggests that the attribute of lifelong learning in itself facilitates the transition from university to work life.39 These future-orientated benefits of capstones also, in turn, link to the backward-looking, integrative benefits discussed above. Reflection forms a core part of lifelong learning skills.40

The literature suggests that the two main functions of capstones, the integration of prior learning (the "cap" function) and transition (the "bridge" function), may be in tension. Attempts to achieve both a cap and a bridge function in a single capstone may lead to overload.41 Surveys of capstones have thus found that most such experiences focus on one of these functions, if not exclusively, then at least in terms of emphasis.42 However, there are also examples from the literature that indicate that a balance can be achieved. Rosenberry and Vicker43 suggest that capstones in communication programmes have managed to achieve a balance between these two dimensions. They suggest that this is perhaps due to the traditional focus of the field on skills development and a strong link to the relevant professions. Kift et al44 confirm this latter point. They note that where a programme does not lead to a clear professional career, the focus of capstones may be on the integrative cap function rather than the transitional bridge one. However, the authors suggest that where there is a clear professional career path following qualification, the transition function should be balanced with the integrative one.

3.1.2 Capstones as assessment instruments

As assessment mechanisms, capstones aim to verify the mastery of graduate attributes and can also serve quality assurance functions.45 However, capstones can be effective instruments of the assessment of outcomes if they fulfil a cap function in integrating prior learning. When that is the case, the capstone offers an opportunity to assess the student's competence on a whole-curriculum basis.46

The capstone is thus an opportunity for the student to demonstrate that through the foregoing curriculum he/she has mastered the programme outcomes. Capstones enable lecturers to assess if the student has indeed developed the stipulated competence to successfully exit the programme. This opportunity in turn provides the basis upon which the programme itself can be evaluated, for example for quality assurance purposes.

While whole-of-programme assessment seems to be the focus of the benefits of capstones in an assessment perspective, the bridge function of capstones can also render assessment benefits. Capstones that aim to provide a transition to after-qualification life, and in particular the world of work, and accordingly involve a significant WIL dimension, offer excellent opportunities for highly authentic assessment practices.47 These opportunities may be the best way to assess students' applied and reflexive competence.

3.2 The advantages of capstones in legal education

When one situates the general pedagogical advantages of capstones in legal education, it is clear that this type of learning experience can add significant value to a number of discipline-specific needs. Kift et al48 accordingly note the following:

In our view, a more comprehensive and integrated approach to law's final year experience provides a viable and valid answer to those who argue that law schools must take up their responsibility (and moral obligation) to provide law students with an education that develops skills in readiness for professional life.

Among the skills that capstones have been shown to be particularly good at developing are "problem-solving, decision-making, critical thinking, an ability to make ethical judgement, and social and human relationship skills".49 All of these are widely accepted as key attributes of law graduates.50

The potential to effectively teach ethics is of particular value in the context of legal education. Capstones situate learning at the interface between the integration of the whole discipline, the relationship between law as a discipline and other disciplines, the role of law in society, and the professional identity-forming function. Such experiences thus provide unique learning opportunities to address particular integrative outcomes such as ethics, which span all these dimensions of the discipline. A need for a more integrated approach to instilling professional ethics in law students has long been recognised in reports on legal education.51 The 2007 Carnegie report on legal education in the USA captures this broader notion of ethics training very well when it states the following:

That is the challenge for legal education: linking the interests of legal educators with the needs of legal practitioners and with the public the profession is pledged to serve - in other words, fostering what can be called civic professionalism.52

By nature of both their integrative and professional identity-forming functions, capstones therefore seem perfectly fit for developing ethics in this broad sense.

Zooming in even more closely to the context of South African legal education, capstones may serve the purpose of transformative legal education (TLE) very well. TLE is a theoretical framework for teaching law in contemporary South Africa and aims to integrate fundamental shifts in a triad of dimensions of legal education.53 These dimensions, firstly, represent a radically different conception of the discipline of law following constitutionalisation. Secondly, they involve an embrace of an outcomes-based constructivist teaching philosophy. Finally, the dimensions of TLE recognise the far-reaching implications of the digital revolution for our knowledge world.54

For the present purposes the most important aspects of TLE that link to the perceived benefits of capstones are the need for integration in legal education and for social, contextual grounding. TLE calls for the heightened development of law graduates' competence to approach legal problems holistically, both in terms of the whole discipline and in terms of interdisciplinary perspectives.55 This is necessary in order to inculcate in law graduates the importance of and ability to engage in substantive legal reasoning premised on overarching constitutional values and rules that now permeate all areas of law in South Africa. This is as opposed to simply being able to engage in technical analyses of particular legal rules. It also facilitates graduates' ability to formulate justification for legal arguments based on extra-legal considerations such as economic factors or psychological insights. The latter objective links with the need for the contextual grounding of legal education in the light of the law's constitutional aim of social transformation in South Africa. It should be evident that both the cap (integrative) and the bridge (transitional) functions of capstones can potentially serve these purposes of TLE quite well.

4 Nature, scope and status of existing capstones in legal education

The literature review above has highlighted the potential pedagogical advantages of capstones both generally and in relation to legal education in particular. Against this background the focus now shifts to an analysis of actual capstones (or the absence thereof) in legal education. The purpose is to determine the extent to which reliance is placed on capstones in order to achieve the abovementioned pedagogical advantages in legal education, both in South Africa and beyond. This sketch of the current landscape of law curricula in respect of capstones will facilitate the final part of the article, in which proposals will be formulated for the development of capstones in South African legal education.

4.1 Capstones in current South African legal education

An analysis of the modes of instruction used in law curricula at 13 South African law faculties/schools (representing 76% of local law faculties/schools) indicates that law curricula locally are largely content based. They are for the most part structured around any number of substantive areas of law (family law, criminal law, civil procedure, contract law etc.) taught largely in isolation from each other. There are few substantive linkages in the form of (final-year) advanced modules in particular areas following a foundational module in that area. For example, an advanced elective constitutional law module in the final year of the LLB programme may bring together learning from a number of prior foundational modules dealing with basic constitutional law, human rights, administrative law and jurisprudence. The focus is thus on what Kift56 has called "what graduating lawyers 'need to know'" as opposed to "what lawyers need to be able to do".

If one searches for capstone elements in existing curricula, a number of different types of module or learning experiences that contain some elements of capstone design emerge. These can broadly be categorised as clinics, internships, moots, research projects, topical capstones and capstone assessment.

There are various ways in which one can analyse these categories of modules or learning experiences. If one focuses on the WIL dimension of each type, one sees that clinics and internships are at one end of the scale, involving authentic learning experiences in a real-world context. Topical capstones and capstone assessment are at the other end of the scale, delivering only simulated exercises based largely on case studies. A different approach to these modules and learning experiences is to focus on the substantive integration that is achieved between different subfields of law and/or declarative and functional knowledge. In this approach, topical capstones and capstone assessment would be at one end of the scale, involving a fair level of integration, with clinics and internships closely behind them. Research projects will be more to the other side, at least as far as the integration of different subfields of law is concerned, given that these projects mostly focus on only a particular, narrow topic within a particular field of law. However, research projects do support integration between declarative knowledge and academic literacy skills, such as research and writing skills.

4.1.1 Capstone assessment

The category of capstone assessment is the closest to "true" capstones found in local LLB curricula. Only one faculty in the group analysed offers such an experience. This is the single curriculum device that seems to be designed specifically to deliver a capstone learning experience. However, it is not a true module in the sense of a series of teaching/learning activities with a set curriculum, outcomes and credit. It is more of a learning experience or an assessment instrument, although it undoubtedly also fulfils a formative function.

In this example of capstone assessment, final-year LLB students are allocated to groups consisting of six to seven students (although the group size varies depending on the size of the final-year class). Groups are constituted in such a manner as to maximise (gender, racial and nationality) diversity within the group. Each group is given a set of facts constituting an integrated, authentic case study involving various (implicit) legal questions. These lead to a final project question that is deliberately designed to bring knowledge from different areas of law together. The group then spends five hours in the university library to collectively address the scenario in the case study and to formulate answers to the questions raised (implicitly and explicitly). Immediately after the five hours, the group takes an hour-long oral examination with a panel of lecturers that asks each student questions on the scenario. Students are individually assessed on a pass/fail basis on the answers that they provide. The outcomes of this assessment are specifically aimed at getting students to engage with the law in an authentic and integrated manner. They need to draw on the whole of their prior learning to identify and address the problems posed by the case study. This assessment also clearly engages functional knowledge. It brings skills such as problem-solving and creating solutions, group work and communication skills to bear on the integrated engagement with the substantive law. This capstone assessment does not carry any credit per se but is a mandatory part of the curriculum in that students must pass it in order to graduate from the LLB programme.

As opposed to this unique capstone experience, the most common modules displaying some capstone properties are law clinics and final-year research projects.

4.1.2 Clinics

All but one of the faculties included in the study offer a clinical experience to LLB students. There is, however, significant variation across this group in respect of that experience. In all instances, the law clinic is a credit-bearing module in the final-year LLB curriculum. The exception is one faculty in which the participation in the clinic is offered in the penultimate year of the programme. In seven faculties participation in the clinical module is mandatory, while it is an elective in the remaining five. This means that of the faculties included in this study, just over half require their students to pass a clinical module before graduating from the LLB programme.

All of the clinical modules involve a combination of in-class engagements focusing on the practice of law, and actual service at the law clinic attached to the relevant university. These law clinics offer a host of legal services to qualifying (mostly indigent) members of the community under the direction of qualified attorneys. The law clinic is a prime example of WIL. As such it primarily serves the bridge, or transitional, function of capstones. However, the authentic setting supports an integrative cap function. Students have to grapple with legal problems that are not necessarily restricted to one particular area of law and that bring together knowledge of substantive law and skills. Given the focus on WIL in clinical modules, there is less emphasis on whole-curriculum reflection and deliberate attempts to bring all prior learning in the programme to a close in an integrated manner. Also, since law clinics provide only a limited number of legal services and not the full range, the substantive areas of law and attendant skills that are integrated are also limited.

There are two variations on the typical clinical module, namely street law modules and internships. Two faculties offer internship options, and three offer street law modules. Only one of the internship options is credit bearing. The other is an option under a broader requirement that all students complete 60 hours of legally orientated community service during the course of their LLB studies. The credit-bearing internship is an elective supervised service-learning module. Individual students are placed at approved institutions where they engage in public service-orientated legal work. These institutions may be international or national state institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or even law firms, as long as the services that students engage in remain not-for-profit public service, for example at a law firm's pro bono office. Students must complete a minimum of 120 hours of service in terms of a faculty-approved work plan. A faculty member is appointed to serve as an academic supervisor to the student. At the end of the internship, the student prepares a report that he/she presents to a panel.

Street law programmes also involve authentic learning experiences in the form of training that students offer to community members. Two faculties offer street law modules as final-year electives. A third faculty offers it as an alternative to work in the law clinic under the banner of the faculty's mandatory legal practice module. In the street law modules, students also engage in both in-class and out-of-class community-based learning activities. The out-of-class experience takes the form of training in particular areas of law presented by the students to particular sectors of the community. They focus on particular legal issues, such as domestic violence or homelessness, for example. Internships and street law programmes are narrower in their focus than general clinical modules. However, they seem to involve more reflection on the part of the student on both the authentic learning experience and the prior learning that informs that experience in the form of final reports (with the internship) or portfolios (in the case of street law).

4.1.3 Final-year research projects

The second most common final-year module that reveals capstone elements is final-year research projects. Ten of the faculties studied have either mandatory (nine) and/or elective (three) research projects as part of their final-year LLB curriculum. The latter two figures add up to more than 100% since a number of faculties have both mandatory and (additional) elective research project options. In one case the research project is an alternative elective to the clinical law module.

The research project typically involves independent research by the particular student into a specific topic, resulting in a substantial research essay. Students are assigned individually to members of staff that supervise the research project. Alternatively, they may participate in focus group supervision, whereby a group of students work on related topics and a single member of staff renders supervision to the group collectively. These research projects can be viewed as a limited form of capstone. Students must apply skills developed across the curriculum to a particular topic in producing the essay. However, these are capstones in only a very limited sense. They involve minimal reflection on the entire prior learning experience. They focus mostly only on one area of law and one topic within that area. They also in general do not play any role in transitioning students to working life and a professional identity. For students going on to postgraduate studies following the LLB, these projects will, however, serve as an important bridge from undergraduate to postgraduate study.

In addition to the learning experiences discussed above, there are two more types of module or learning experience in current LLB curricula in South Africa that may fulfil capstone functions. These are moots and what may be called topical capstones.

4.1.4 Moots

A moot is a simulated court case in which two teams consisting of two students in each team argue for fictitious parties on opposing sides of a legal dispute with either an academic or a practitioner presiding as the judge.57 The moot typically follows the same rules of procedure as would apply in the real, simulated court. It includes teams preparing written arguments that are exchanged between them as well as oral argument before the judge. The moot is based on a set of facts that is provided to the students. Typically a hypothetical dispute is specifically designed to raise particular points of law. The points of dispute are usually restricted to the points of law (rather than factual disputes or disputes of evidence, for which reason moots typically simulate appellate courts rather than trial courts).

Of the faculties included in this study, five offer mooting as free-standing items in the curriculum. These are not, however, all in the form of distinct modules. In one instance students are required to participate in a moot during their penultimate year of study. The moot does not carry any of its own credit but is linked to one of the other modules that the students take in that year. All of these faculties, either in addition to in-house moots or as the only moot option, recognise participation in one of the international moot court competitions for credit purposes. These competitions include the All African Human Rights Moot Court Competition and the Phillip Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition.

Of the eight faculties that do not offer mooting as distinct items within the curriculum, only one offers no mooting opportunity. The remaining seven all use mooting as skills development tools or learning experiences within modules that are typically aimed at developing general advocacy skills or communication skills. That is, a moot is one teaching/learning activity within such modules. The moot in this latter group of faculties does not fulfil any capstone function but is purely a skills development tool.

In the group of five faculties that do formally recognise moots within their curriculum, some capstone element is to be found in the moot options. In all of these options, the moot integrates at least one substantive area of law (for example law of contract, constitutional law or criminal law) and formal law (civil or criminal procedure). This results in a limited measure of integration of prior substantive learning. The integrative function of moots increases in the measure that the hypothetical dispute involves more than one substantive area of law.

In addition, moots have been found to develop important law graduate skills such as "research skills, analysis, legal argument, teamwork and presentational skills" as well as critical thinking abilities.58 The moot thus also serves to consolidate the development of these skills with substantive knowledge, further promoting the integration of prior learning. A moot is also clearly a fairly authentic, albeit simulated, teaching/learning activity. As such, moots arguably assist students to conceptualise their prior learning in a professional work context. In this way moots assist students' transition out of university. However, moots support the transitional function of capstones to a very limited extent.

Of the five faculties where moots form a distinct part of the curriculum, two oblige students to participate in the moot. Mooting is only an elective in the other three cases. Of the two faculties where mooting is mandatory, one offers it only in the penultimate year of study, which lessens the potential capstone function of the moot.

4.1.5 Topical capstones

The final item found in LLB curricula in South Africa that resembles some capstone characteristics is what can be called topical capstones. These are "ordinary" modules offered in the final year of the LLB, in all cases as electives. They exist alongside a host of other typical final-year elective modules dealing mostly with highly specialised areas of law (such as information technology law, media law, refugee law or public procurement law). What sets these few electives apart from other typical final-year electives is that they focus not on a particular area of law but rather on a social phenomenon. The result is that these modules bring together a range of different areas of law in relation to the particular phenomenon. These modules promote the integration of the different areas of distinct prior learning and situate such integration within a particular (social) contextual setting. Two examples, offered from time to time at a number of faculties (depending on staff availability and student interest), are legal issues relating to HIV/AIDS, and gender and the law. Four faculties offer modules that fall into this category of topical capstones.

4.1.6 The curriculum landscape

When one considers the complete curriculum landscape emerging from the discussion above, it seems that all of the faculties included in this study offer at least one learning experience that reveals some capstone characteristics. In two faculties it is only a clinical experience, and in one faculty it is only a final-year research project. At the other end of the scale, six faculties offer three or more different types of learning experience with capstone properties. In all but one of the faculties, at least one of the modules with capstone properties is mandatory. It would thus seem that the bulk of the law graduates from these faculties have the benefit of some capstone experience before graduating. However, there is very little evidence of coordination of the distinct modules or learning experiences with capstone characteristics at individual faculties. The capstone experience in particular modules itself thus seems to be offered largely in isolation from other similar experiences at other points in the curriculum. The evidence suggests that there is thus no coherent, coordinated capstone experience in South African legal education.

One can plot the learning experiences with capstone characteristics in existing LLB curricula on a continuum. At one end are those that exhibit a large number of the key elements of capstones (as defined above). At the other end are those that exhibit only one distinct capstone element. When one subsequently considers the complete LLB curriculum landscape in terms of such a continuum, it emerges that while most law students have some capstone experience, that experience is generally at the lower capstone end of the continuum. Students thus have only a very limited capstone experience.

The discussion in this section has shown that among the law faculties included in this study, there are no pure capstones to be found. The only limited exception to this conclusion is the capstone assessment project found in one faculty, although this experience qualifies more as an assessment instrument than a capstone. The question subsequently arises if one cannot have pure capstones in legal education. Put differently, is it not possible to implement modules or learning experiences that can bring the benefits of capstones to legal education? In the next section a few examples from foreign law curricula will be discussed to serve as exemplars for the development of capstones in South Africa.

4.2 Capstones in foreign legal education

In a comparative study of legal education it is important to bear the differences between various legal systems in mind to the extent that these impact on the nature of legal education. In this regard, systems sharing a common law background (that is, systems with significant English law influence) are more easily comparable given the common structure of legal practice and consequently legal education in those systems.59 However, important differences remain and these should be carefully borne in mind when considering comparative perspectives.

The exemplars briefly discussed in this section are drawn from two systems, namely the United States of America (USA) and Australia. Both of these systems offer interesting examples of the use of capstones in legal education and are broadly comparable with South African legal education.

In the USA the use of capstones in legal education is not surprising, given the longstanding use of capstones in undergraduate (non-law) studies in college majors.60 However, the USA experience must also be approached with caution from a South African perspective, given the important differences between legal education in that country and that in local conditions. In the USA students can study law in graduate law schools only following a first undergraduate degree. Most first-year law students are in fact at least in the fifth year of tertiary study.61 Furthermore, there is no formal period of practical training following graduation from law school before being admitted to the legal profession in the USA. Once a student has obtained his/her Juris Doctor (JD) degree (the basic law degree in the USA), he/she may write a bar examination. If the student passes, s/he would be a fully qualified lawyer in the relevant state and allowed to practise as such.62

This situation obviously differs significantly from the South African one. Locally the LLB degree is a first undergraduate degree, but law graduates must still complete a period of vocational training. The new graduate must engage in a two-year period of articled clerkship with an experienced principal in a law practice in order to qualify to join the attorneys' profession. Alternatively a graduate may opt for a year of pupillage at the bar before writing the bar examination and starting to practise as an advocate at the bar.63 There is, however, the possibility that an LLB graduate could simply approach the High Court and be admitted as an advocate without any period of practical training and subsequently practise as an independent advocate (that is, outside of the bar). This route, however, remains the exception rather than the rule in South African legal practice.

While Australia does not have a long tradition of capstones, either in higher education in general or in law,64 Australian legal education closely resembles that in South Africa. Both countries have a common law background, and in both countries the legal profession is split between attorneys/solicitors and advocates/barristers.65 In both countries, formal legal education takes the form of a first four-year undergraduate degree or a second (mostly three-year) degree.66 As in South Africa, admission to either of the professions in Australia is based on a period of practical training within the relevant profession.67 Beyond these formal similarities between the two countries, it is also striking that in Australia many of the same issues currently debated in South African legal education are also prevalent. Australian legal education, like its South African counterpart, is struggling with significant increases in student numbers without concomitant increases in resources and capacity. In Australia there is pressure to get students practice-ready by the time they graduate. There is increasing focus on skills development rather than content knowledge. Student fees continue to increase and the student body is becoming more diverse.68 This "brief environmental snapshot" of legal education in Australia that Kift69 sketches is familiar to a South African audience. Consequently, it is highly significant for the present purposes that one of the most comprehensive studies on the use of capstones in legal education was recently concluded in Australia.70

Based on their research, Kift et al71 have put forward five subject models on which capstones could be based as well as sixteen examples of actual capstones at USA and Australian law schools. The five models are:

- Problem-based learning capstones

- WIL capstones

- Project-based capstones

- Alternative dispute resolution capstones Practical legal training capstones

The sixteen examples of capstone experience are:

Capstone experience 1: The Virtual Practice/Law Office

Capstone experience 2: Transactional Legal Practice ...

Capstone experience 3: The Clinical Year in Law ...

Capstone experience 4: Law Internship ...

Capstone experience 5: Virtual Law Internship ...

Capstone experience 6: General Practice Skills Course ...

Capstone experience 7: Fundamentals of Law Practice ...

Capstone experience 8: Legal Clinics ...

Capstone experience 9: Conferences

Capstone experience 10: Student-prepared Journal Article/Issue ...

Capstone experience 11: Dispute Resolution/Advocacy Law

Capstone experience 12: Law of Remedies

Capstone experience 13: Interdisciplinary

Capstone Seminar Capstone experience 14: Advanced Research Problem

Capstone experience 15: Lawyer as Problem Solver ...

Capstone experience 16: Ethics ...72

While all of these examples are interesting and worth considering, particular attention will be given here to only a few that seem to hold out the most promise for development in South African legal education, beyond what currently exists.

4.2.1 Problem-based learning

The first model and example to consider is that of the problem-based learning capstone, as exemplified in "Capstone experience 15: Lawyer as Problem Solver". This model involves a hypothetical, complex legal problem that students must resolve over the course of a semester, either individually or in teams. The problem is designed to involve various areas of law. Students are presented at the outset with the basics of the problem in means that are as authentic as possible. An example of this might be video footage of client interviews and real documents from actual disputes.73 During the course of the semester, students work their way through the problem. More information is provided over time as students complete distinct assignments based on the process of problem solving. Activities include drafting letters to the client or counterparty or conducting research and writing research reports. These capstones are often co-taught between academic lecturers and practitioners.74 The teaching/learning and/or assessment activities may also include mooting, whereby students present arguments on different sides of the problem. This capstone serves both as a bridge and a cap function. As Kloppenberg,75 Dean of the Dayton Law School, from which the example comes, states,

we were particularly concerned about the gap between the academy and the profession, and sought to prepare our students better for practice, without sacrificing a strong, broad foundation in analytical thinking and doctrinal coverage.

4.2.2 Virtual options

A second set of noteworthy examples are those that rely on technology to simulate virtual worlds in which students can have authentic experiences. Two examples are "Capstone experience 1: The Virtual Practice/Law Office" and "Capstone experience 5: Virtual Law Internship".

In the former, students are assigned an authentic role in a virtual work environment, typically a law firm, and given a case file to manage within the virtual office.76 The file involves a legal problem with authentic artefacts that the student must use to resolve the matter and finalise the file. During the course of the semester, students are assigned various tasks in relation to the file, either directly through release on the learning management system (LMS) or by tutors. Alongside the integration of various fields of law in the given case, students are also exposed to file management and other practice-related competences. This example again combines the cap and bridge functions of capstones.

An alternative use of technology to facilitate a capstone experience is the virtual law internship example. In this example students interact with a real, external host but through digital means. While students thus do not leave campus, they are functioning in an off-campus authentic environment.77 Learning activities include an application process involving letters of application and résumés, discussion forums, the completion of a project leading to a project outline or report and, finally, reflection in the form of a portfolio, all situated in the real placement, albeit virtually.78

4.2.3 Conference

The third innovative capstone experience worth noting is the use of conferences. Kift et al79 note that while there are no examples of the use of conferences as capstones in legal education, they have been used to this effect in other disciplines, such as engineering. The idea is not that students will present their capstone projects at a capstone conference, something that is fairly common in the USA. Instead, the conceptualisation and organisation of the conference itself form the capstone experience. Students thus collaborate around a topic that forms the theme of the conference. They organise the event, including formulating the call for papers, reviewing the abstracts and presenting the bulk of the papers, even though they may approach faculty members or even outside experts to also participate.

In this model, students have to draw on their prior learning to bring relevant areas of law together around the theme of the conference so that the experience serves a cap function. The model may also serve a limited transitional function in that students may be required to engage with professionals to participate in the conference. This particular model may also be well suited to pursuing an interdisciplinary approach to a societal issue and having students collaborate across disciplines.

4.2.4 Remedies capstone

While topical capstones were identified as one type of module or learning experience that reveals capstone properties in existing LLB curricula in South Africa, the focus on remedies as the subject matter of such a topical capstone in the "Capstone experience 12: Law of Remedies" example merits attention.

Most if not all law modules during the course of legal education would touch upon remedies in some form. A final-year module that focuses exclusively on remedies provides a good platform to facilitate the integration of prior learning and to bring out the interaction between subfields of law that have been studied separately.80 Since the issue of remedies is also a highly practical one, a remedies capstone may provide a good opportunity for transition in engaging students in authentic problem-solving learning exercises.81 Remedies courses may furthermore integrate skills with substance in a manner that is difficult to achieve in other modules. Relevant skills include drafting skills attendant upon formulating draft orders, numeracy skills involved in calculating damages and interest, or the skill of analysing facts.82

5 Capstone curriculum options

The literature review and the examples from existing legal (and non-legal) curricula from both South Africa and beyond enable us to consider proposals regarding the design of capstones in the LLB curriculum to address some of the current concerns about legal education.

As a point of departure, it seems that the potential pedagogical advantages of capstones in the form of the learning experiences they create in general and for South African legal education in particular are significant. It follows that, in principle, it is worth exploring capstones as a mode of instruction in legal education in South Africa.

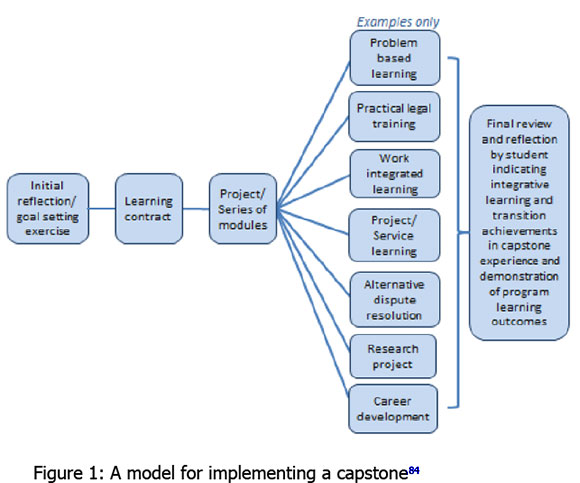

Kift et al83 present a useful implementation model in approaching capstones, which is reflected in Figure 1.

What this model illustrates is the desirability of flexibility in the design of a final-year capstone experience for law students. Since students will have different needs, both in terms of their learning styles and their career objectives, it is ideal that multiple options be offered to facilitate each student's capstone experience.85 To this end different types of capstone should be included in the curriculum, and some choice among them should be given to students. However, it is important that these options be coordinated in such a manner that the coherent capstone experience of every student is ensured. This may entail that some core elements of the overall capstone model are mandatory while others are conditional electives. The model also incorporates the notion of a learning contract in terms of which students take responsibility for their own development. This feature of the implementation model is useful in that it reinforces the development of lifelong learning skills.

The law clinic seems to be a widely used model of delivering a capstone experience, in South African law schools as elsewhere. However, it is unlikely that all law graduates in South Africa could be offered a clinical training opportunity of this nature. One reason is the significant cost implications.86 Another is the potentially significant increases in student numbers following government's declared intention to greatly increase university participation levels in South Africa.87 Existing clinical education potentially supports the bridge function of capstones well. Concern has, however, been raised that they fail to adequately integrate with substantive law taught in the rest of the curriculum.88 This undermines the integration function of clinics as capstones. Given the limited nature of the legal services offered at law clinics, it is also to be expected that not all students will find the clinical experience beneficial in transitioning to post-qualification life.

While law clinics should continue to form an important part of the capstone experience offered in South African legal education, attention should be given to the relationship of clinics to other components of a more comprehensive capstone experience. In this respect, problem-based learning, in particular through virtual simulations, may be an effective supplement to clinics in the overall capstone experience. Setting up a virtual office module may also be resource intensive.89 However, once the design is complete the experience can fairly easily be rolled out to large and successive cohorts of students with much lower further resource implications.

Ideally the clinical experience, whether real or virtual, should be accompanied by a more discipline-based capstone module that focuses more closely on the integration of prior learning. The most promising candidate for this role is probably the topical capstone, which is already found in some existing South African law faculties.

The example of a remedies capstone seems particularly promising as a design for such a module. Such a module promotes deep levels of integration of various subfields of law and incorporates many key skills. It has an authentic characteristic that would in addition support the transition function of capstones. Alternatively, a wider range of modules addressing cross-cutting (social) phenomena could be introduced within a closed electives group. These phenomena should also bring together distinct areas of law and force students to reflect on prior learning. Existing modules focusing on law and HIV/AIDS, and law and gender are good examples of such an approach. One could also, for example, think of seminars focusing on sports law, law and poverty, the law of the built environment, the law and the regulatory state, or law and economic development. These would, however, be particularly resource intensive. A third alternative could be to expand the capstone assessment currently found in one South African law faculty to a full semester module. Such a module could simply engage in problem-based learning around a complex legal problem specifically formulated for that module, involving multiple subfields of law. The final-year class could be divided into smaller groups, each with its own problem and taught separately by a team of lecturers with expertise in the relevant fields involved in the problem at issue. Teaching/learning activities could include research, drafting, and the discussion of various dimensions of the complex problem within the context of the entire problem.

Strong consideration should be given to making some combination of the clinical experience and the discipline-based topical capstone mandatory for all students in order to achieve a well-rounded capstone experience.

In addition to the two core elements of the overall capstone experience set out above, law faculties could offer a range of further, complementary capstone options from which students could choose, aligned to their learning styles and career plans. These could include moots, conferences, research projects and internships.

6 Conclusion

While legal education in South Africa is currently undoubtedly under pressure from multiple angles, these pressure points can also be leveraged to achieve pedagogical advantages. Kift90 has noted that it was the "external drivers for change in the legal and tertiary sectors" in Australia that created the momentum for "reform to core undergraduate law curriculum that might otherwise have been too radical to contemplate". This included careful consideration of capstones.

The question is if changes on the horizon in respect of South African legal education will open up the same scope for drastic change in the LLB curriculum. If so, perhaps a move towards true problem-based learning across the entire curriculum, something to which law as a discipline seems particularly well suited, would be possible. If not, extending and consolidating capstone experiences in the final year would probably be the most one could hope for.

A capstone learning experience for each law graduate may at least address some of the key concerns raised about legal education at present. These include skills in communication, problem solving, ethics, and in general a holistic view of the law in practice. Capstones are obviously not the solution to all problems in legal education, but it seems that they hold significant potential as a mode of instruction in respect of some of these problems.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Literature

American Bar Association ABA Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools 2013-2014 (ABA Publishing Chicago 2013) [ Links ]

Adams L et al"Challenges in Teaching Capstone Courses" 2003 35(3) ACM SIGCSE Bulletin 219-220 [ Links ]

Altbach PG and Kelly GP "Introduction: Perspectives on Comparative Education" in New Approaches to Comparative Education (University of Chicago Press Chicago 1986) 1-10 [ Links ]

Biggs J and Tang C Teaching for Quality Learning at University (Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press Berkshire 2011) [ Links ]

Brockopp DY, Hardin-Pierce M and Welsh JD "An Agency-financed Capstone Experience for Graduating Seniors" 2006 45(4) Journal of Nursing Education 137-140 [ Links ]

Collier PJ "The Effects of Completing a Capstone Course on Student Identity" 2000 Sociology of Education 285-299 [ Links ]

Cilliers P "Complexity, Deconstruction and Relativism" 2005 22(5) Thieory, Culture & Society 255-267 [ Links ]

De Klerk W "University Law Clinics in South Africa" 2005 SALJ 929-950 [ Links ]

Dicker L "The 2013 LLB Summit" 2013 26(2) Advocate 15-20 [ Links ]

Durel RJ "The Capstone Course: A Rite of Passage" 1993 Teaching Sociology 223-225 [ Links ]

Gardner JN and Van der Veer G "The Emerging Movement to Strengthen the Senior Experience" in The Senior Year Experience: Facilitating Integration, Reflection, Closure, and Transition (Jossey-Bass Publishers San Francisco 1998) 3-20 [ Links ]

Gillespie AA "Mooting for learning" 2007 JCLLE19-37 [ Links ]

Greenbaum L "Current Issues in Legal Education: A Comparative Review" 2012 Stell LR 16-39 [ Links ]

Hatchard J and Slapper G "The Role of the Commonwealth and Commonwealth Associations in Strengthening Administrative Law and Justice" in Corder H (ed) Comparing Administrative Justice Across the Commonwealth (Juta Cape Town 2006) 405-422 [ Links ]

Henscheid JM Professing the Disciplines: An Analysis of Senior Seminars and Capstone Courses (University of South Carolina Columbia SC 2000) [ Links ]

Jervis KJ and Hartley CA "Learning to Design and Teach Accounting Capstone" 2005 Issues in Accounting Education 311-339 [ Links ]

Kift S "A Tale of Two Sectors: Dynamic Curriculum Change for a Dynamically Changing Profession" 2004 2(2) JCLLE 5-22 [ Links ]

Kift S "21st Century Climate for Change: Curriculum Design for Quality Learning Engagement in Law" 2008 Legal Educ Rev 1-30 [ Links ]

Kift S, Field R and Wells I "Promoting Sustainable Professional Futures for Law Graduates through Curriculum Renewal in Legal Education: A Final Year Experience (FYE2)" 2008 eLaw Journal 145-158 [ Links ]

Kleyn D and Viljoen F Beginner's Guide for Law Students (Juta Claremont 2010) [ Links ]

Kloppenberg LA "Lawyer as a Problem Solver: Curricular Innovation at Dayton" 2007 U Tol L Rev547-556 [ Links ]

Kloppenberg LA "Educating Problem Solving Lawyers for our Profession and Communities" 2009 Rutgers L Rev 1099-1114 [ Links ]

Novitzki JE "Critical Issues in the Administration of an Integrated Capstone Course" 2001 Informing Science 372-378 [ Links ]

Pantazis A "The LLB" 2013 26(2) Advocate 22-23 [ Links ]

Quinot G "Transformative Legal Education" 2012 SALJ 411-433 [ Links ]

Redmond MV "Outcomes Assessment and the Capstone Course in Communication" 1998 Southern Communication Journal 68-75 [ Links ]

Rosenberry J and Vicker LA "Capstone Courses in Mass Communication Programs" 2006 Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 267-283 [ Links ]

Rowles CJ et al "Toward a Model for Capstone Experiences: Mountaintops, Magnets, and Mandates" 2004 Assessment Update 1-2, 13-15 [ Links ]

Ruhl JB "Law's Complexity: A Primer" 2008 Georgia State LR 885-911 [ Links ]

Saunders C "Apples, Oranges and Comparative Administrative Law" in Corder H (ed) Comparing Administrative Justice Across the Commonwealth (Juta Cape Town 2006) 423-449 [ Links ]

Sullivan WM et al Educating Lawyers: Preparation for the Profession of Law (Jossey-Bass San Francisco 2007) [ Links ]

Teaching and Learning Unit, University of Melbourne Interdisciplinary Higher Education (The Teaching and Learning Unit Carlton 2010 [ Links ]

Van Acker L and Bailey J "Embedding Graduate Skills in Capstone Courses" 2011 Asian Social Science 69-76 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe P "The Trouble with LLB Graduates..." 2007 (April) De Rebus 2 [ Links ]

Von Prondczynsky A "Institutionalisierung und Ausdifferenzierung der Erziehungswissenschaft als Forschungsdisziplin" 2002 5(Special ed) Zeitschrrift fur Erziehiungswissenschiaft 221-230 [ Links ]

Wagenaar TC "The Capstone Course" 1993 Teaching Sociology 209-214 [ Links ]

Weaver RL and Partlett DF "Remedies as a 'capstone' Course" 2007 The Review of Litigation 269-279 [ Links ]

Webb J "Law, ethics, and complexity: Complexity theory and the normative reconstruction of law" 2005 Clev St L Rev 227-242 [ Links ]

Government publications

Department of Higher Education and Training Green Paper for Post-school Education and Training Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training (Gen N 11 in GG 34935 of 13 January 2012)

Legal Practice Bill B20B-2012

Internet sources

Australian Learning and Teaching Council 2010 Learning and Teaching Standards Project: Bachelor of Laws. Learning and Teaching Academic Standards Statement www.olt.gov.au/resource-law-ltas-statement-altc-2010 accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

Council of Australian Law Deans 2013 Studying Law in Australia http://www.cald.asn.au/slia/index.htm accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

International Bar Association 2013 How to Qualify as a Lawyer in New Yorkhttp://www.ibanet.org/PPID/Constituent/Student_Committee/qualify_lawyer_NewYork.aspx accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

Jeffery JH 2013 Keynote Address by the Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development at the Annual General Meeting of the KwaZulu-Natal Law Society http://www.justice.gov.za/m_speeches/2013/20131018-dm-kzn-law-society.html accessed 23 October 2013 [ Links ]

Kift S et al 2012 Curriculum Renewal in Legal Education: Capstone Experiences Toolkit https://wiki.qut.edu.au/display/capstone/Home accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

Kift S et al 2013 Curriculum Renewal in Legal Education: Final Report https://wiki.qut.edu.au/display/capstone/Home accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

Legal Education and Training Review 2013 Setting Standards: The future of Legal Services Education and Training Regulation in England and Wales http://letr.org.uk/the-report/index.html accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

Law Society of South Africa 2010 Press Release: Law Society Welcomes LLB Curriculum Review - Repeats Concern at Law Graduates' Lack of Basic Skiils www.lssa.org/upload/LSSA%20Press%20Release%20LLB%20report_22_11_2010.pdf accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

McKenzie LJ et al 2004 Capstone Design Courses and Assessment: A National Study http://aaueng.com/Portals/0/AAU/Publications/Capstone%20Design%20Cours es%20and%20Assessment.pdf accessed 20 October 2013 [ Links ]

Nair N 2012 'LLB Report Urges Numeracy, Literacy Training' The Times6 July 2006 http://www.timeslive.co.za/thetimes/2012/07/06/llb-report-urges-numeracy-literacy-training accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education 2007 Subject Benchmark Statement: Law http://www.qaa.ac.uk/Publications/InformationAndGuidance/Pages/Subject-benchmark-satatement-Law-2007.aspx accessed 21 October 2013 [ Links ]

Radebe JT 2012 Budget Vote Speech by Mr JT Radebe, MP, Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, Tuesday, 17 May 2012, National Assembly, Parliament http://www.justice.gov.za/m_speeches/2012/20120517_min_budget-vote.html accessed 23 October 2013 [ Links ]

South African Law Deans Association, Law Society of South Africa and General Council of the Bar 2013 Joint Press Statement: Legal Education in Crisis? Law Deans and the Legal Profession Set to Discuss Refinement of LLB Degree www.lssa.org/upload/LLB%20SUMMIT%20PRESS%20RELEASE.pdf accessed 15 April 2013 [ Links ]

South African Qualifications Authority date unknown Registered Qualification: Bachelor of Laws http://regqs.saqa.org.za/viewQualification.php?id=22993 accessed 15 October 2013 [ Links ]

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ABA; American Bar Association

ACM SIGCSE; Association for Computing Machinery Special Interest Group on Computer Science Education

ALTC; Australian Learning and Teaching Council

CALD Council of Australian Law Deans

CHE; Council on Higher Education

Clev St L Rev; Cleveland State Law Review

DoHET; Department of Higher Education and Training

GCB; General Council of the Bar of South Africa

George State LR; George State Law Review

IBA; International Bar Association

IT; Information technology

JCLLE; Journal of Commonwealth Law and Legal Education

JD; Juris Doctor

Legal Educ Rev; Legal Education Review

LETR; Legal Education and Training Review

LMS; Learning management system

LR; Law Review

LSSA; Law Society of South Africa

NGO; Nongovernmental organisation

NYCBA; New York City Bar Association

QAA; Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (UK)

Rutgers L Rev; Rutgers Law Review

SALDA; South African Law Deans Association

SALJ; South African Law Journal

SAQA; South African Qualifications Authority

Stell LR; Stellenbosch Law Review

TLE; Transformative legal education

TLU; Teaching and Learning Unit (University of Melbourne)

U Tol L Rev; University of Toledo Law Review

UK; United Kingdom

WIL; Work-integrated learning

1 Greenbaum 2012 Stel LR 32; LSSA 2010 www.lssa.org/upload/LSSA%20Press%20Release%20LLB%20report_22_11_2010.pdf; Nair 2012 http://www.timeslive.co.za/thetimes/2012/07/06/llb-report-urges-numeracy-literacy-training; Van der Merwe 2007 De Rebus 2.

2 Pantazis 2013 Advocate 22.

3 Dicker 2013 Advocate 15.

4 Dicker 2013 Advocate 15-20; Pantazis 2013 Advocate 22-23.

5 LETR 2013 http://letr.org.uk/the-report/index.html ix.

6 Jeffery 2013 http://www.justice.gov.za/m_speeches/2013/20131018-dm-kzn-law-society.html.

7 Radebe 2012 http://www.justice.gov.za/m_speeches/2012/20120517_min_budget-vote.html.

8 SALDA, LSSA and GCB 2012 www.lssa.org/upload/LLB%20SUMMIT%20PRESS%20RELEASE.pdf 2.

9 Novitzki 2001 Informing Science 373; Redmond 1998 Southern Communication Journal 73; Van Acker and Bailey 2011 Asian Social Science 69.

10 Kift et al 2013 https://wiki.qut.edu.au/display/capstone/Home.

11 Altbach and Kelly "Introduction" 3.

12 Brockopp, Hardin-Pierce and Welsh 2006 Journal of Nursing Education 137; Henscheid Professing the Disciplines 2; Rowles et al 2004 Assessment Update 1.

13 Rosenberry and Vicker 2006 Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 271, 274.

14 McKenzie et al 2004 http://aaueng.com/Portals/0/AAU/Publications/Capstone%20Design%20Courses%20and%20Assessment.pdf 2-4.

15 Also see Henscheid Professing the Disciplines.

16 See Adams et al 2003 ACM SIGCSE Bulletin 220; Rosenberry and Vicker 2006 Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 271-272; Van Acker and Bailey 2011 Asian Social Science 70.

17 Durel 1993 Teaching Sociology 223.

18 Kift et al=2013 https://wiki.qut.edu.au/display/capstone/Home 18.

19 Rowles et al2004 Assessment Update 1; Van Acker and Bailey 2011 Asian Social Science 69-70.

20 Brockopp, Hardin-Pierce and Welsh 2006 Journal of Nursing Education 137; Collier 2000 Sociology of Education 293-295; Van Acker and Bailey 2011 Asian Social Science 69.

21 Jervis and Hartley 2005 Issues in Accounting Education 313; Wagenaar 1993 Teaching Sociology 211.

22 Wagenaar 1993 Teaching Sociology 211.

23 Durel 1993 Teaching Sociology 224; Jervis and Hartley 2005 Issues in Accounting Education 312.

24 Wagenaar 1993 Teaching Sociology 210-211.

25 Jervis and Hartley 2005 Issues in Accounting Education 314; Rosenberry and Vicker 2006 Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 269-271.

26 Kift, Field and Wells 2008 eLaw Journal 153.

27 Durel 1993 Teaching Sociology 224.

28 See Cilliers 2005 Theory, Culture & Society 255.

29 Ruhl, 2008 Georgia State LR 885; Webb 2005 Clev St L Rev 228.

30 TLU Interdisciplinary Higher Education 6; Von Prondczynsky 2002 Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 221.

31 Kift, Field and Wells 2008 eLaw Journal 150; Rosenberry and Vicker 2006 Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 269.

32 Henscheid Professing the Disciplines 1.

33 Biggs and Tang Teaching for Quality Learning 95-108.

34 Gardner and Van der Veer "The Emerging Movement" 5-6; Kift et al 2013 https://wiki.qut.edu.au/display/capstone/Home 40.