Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.17 n.3 Potchefstroom Sep. 2014

ARTICLES

The problematic practical application of Section 1(6) and 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act under a new dispensation

J Jamneck

BLC LLB LLD (UP). Professor in Private Law, Unisa. E-mail: jamnej@unisa.ac.za

SUMMARY

In recent years many developments have taken place in the field of the law of succession. Du Toit aptly states that "despite the static image that the law of succession often projects, it is a vibrant area of the law that has undergone dramatic changes in recent times and will continue to do so in future". This is indeed the case, as has been illustrated numerous times by the decisions in our courts as to the meaning of the word "spouse" and the recognition of the family as an important social institution. Although the family as an institution is not per se protected in the Constitution, our courts have recognised it as a vital social institution that comes in many different shapes and sizes and it has stressed that one form of family cannot be entrenched at the expense of other forms. As a result of various decisions on the meaning of the word "spouse" under a new dispensation, a Discussion Paper, in the form of Discussion Paper 129 (Project 25) Statutory law revision: Legislation administered by the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (2011), has seen the light in order to suggest amendments to certain legislative provisions. Unfortunately certain issues covered in this Discussion Paper have not been clearly set out and need further investigation.

Keywords: Intestate succession; succession; family; law of succession; meaning of spouse.

1 Introduction

In recent years many developments have taken place in the field of the law of succession. Du Toit1 aptly states that "despite the static image that the law of succession often projects, it is a vibrant area of the law that has undergone dramatic changes in recent times and will continue to do so in future". This is indeed the case, as has been illustrated numerous times by the decisions in our courts as to the meaning of the word "spouse" and the recognition of the family as an important social institution. Although the family as an institution is not per se protected in the Constitution,2 our courts have recognised it as a vital social institution that comes in many different shapes and sizes and it has stressed that one form of family cannot be entrenched at the expense of other forms.3

As a result of various decisions4 on the meaning of the word "spouse" under a new dispensation, a Discussion Paper, in the form of Discussion Paper 129 (Project 25) Statutory law revision: Legislation administered by the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (2011),5 has seen the light in order to suggest amendments to certain legislative provisions. Unfortunately certain issues covered in this Discussion Paper have not been clearly set out and need further investigation.

2 Background

Before investigating the recommendations of the Discussion Paper, it is necessary to briefly review the cases in which our courts have been asked to interpret the word "spouse" or "survivor" in recent years.6

The Constitutional Court, in the case of Volks v Robinson,7 protected the institution of marriage when a claim for maintenance of a surviving spouse was at issue. The deceased and his heterosexual life-partner, Ms Robinson, had been living together for 16 years but were never married and as a result, the executor of the deceased estate rejected a claim for maintenance on the basis that Ms Robinson was not "a survivor" as contemplated by the Maintenance of Surviving Spouses Act.8 Ms Robinson applied to the court for an order declaring that she was entitled to lodge a claim for maintenance against the estate, alternatively declaring that the Act was unconstitutional and invalid as it did not include a person in a permanent life-partnership. The High Court agreed with her.9

The Constitutional Court agreed that the exclusion of heterosexual life-partners from the protection of the Maintenance of Surviving Spouses Act amounted to discrimination on the basis of marital status but it found that the discrimination was not unfair. It held that the Constitution recognises marriage as an institution10 and in view of this and the international recognition of the institution of marriage, the law may distinguish between married and unmarried people and therefore deny benefits to unmarried people that are extended to married people. The judges held that the case must be seen in the context of all the rights and duties emanating from marriage. Spouses in a marriage inter alia have a legal reciprocal duty of support towards each other, but this duty of support does not extend to unmarried parties. It therefore follows that the Constitution does not require that an obligation be placed on the estate of a deceased person in circumstances where the law did not during his lifetime place such an obligation on him. The Court therefore refused to extend the protection of the Maintenance of Surviving Spouses Act to heterosexual life-partners.11

Our courts and legislature have also extended the protection of family units and marital relationships to include same-sex partnerships and polygynous marriages. In Gory v Kolver12 the Court explained the reasons for the difference between its decision and that given in the Robinson case and its willingness to extend protection to same-sex couples on the basis that, whereas heterosexual couples could legally get married in South Africa, same-sex couples could not. Where heterosexual couples therefore chose not to get married, they could not depend on the protection of the law when it came to inheritance on intestacy and claiming maintenance from the estate of the partner. Same-sex couples on the other hand did not have the option of getting married and it was therefore fair to extend spousal benefits to them if their relationship conformed to certain guidelines.

Since the decision in the Gory case, the Civil Union Act13 has widened the protection of family life. The Civil Union Act provides for the solemnisation and legal consequences of civil unions entered into either by way of marriage or civil partnership. In the preamble to the Act reference is made to the protection granted by sections 9, 10 and 15 of the Constitution and the fact that the family law dispensation that existed after the commencement of the Constitution did not allow same-sex couples the same status and benefits that marriage afforded heterosexual couples. Although the reference in the preamble is to same-sex couples, the Act clearly applies to heterosexual couples as well. It defines a civil union as "the voluntary union of two persons who are both 18 years of age or older, which is solemnised and registered by way of either a marriage or a civil partnership, in accordance with the procedures prescribed in this Act, to the exclusion, while it lasts, of all others".14 Section 13 provides that the legal consequences of a marriage in terms of the Marriage Act15 apply to a civil union. It further provides that, other than the Marriage Act and the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act,16 any reference to a marriage, husband, wife or spouse in any other act or law, including the common law, includes a civil union and a civil union partner.17

Prior to the Constitution there was limited statutory or other legal recognition of religious marriages.18 Since the Constitution, some Acts have been introduced or amended to provide for partners in such marriages.19 Our courts have also had several opportunities to deal with this issue20 but the Constitutional Court was first faced with the issue of the constitutionality of the position of spouses in a religious marriage in Daniels v Campbell21 The applicant was married to her late husband in terms of Muslim law. Despite the marriage being factually monogamous, she was not in law recognised as a spouse and therefore could not inherit from his intestate estate. The High Court22 found the provisions of the Intestate Succession Act to be unconstitutional on the basis that the narrow interpretation of the word "spouse" violated section 9 of the Constitution. It ordered that section 1 of the Intestate Succession Act was to be read as though "spouse" would include a husband or wife married in accordance with Muslim rights in a de facto monogamous union. The Court held that it would be correct to include women married in terms of Muslim rights within the definition of "spouse" both from the perspective of fairness and in line with the common linguistic interpretation of the word "spouse".23

The Constitutional Court furthermore protected polygynous marriages in Hassam v Jacobs.24 It held that the significance attached to a polygynous union in terms of Muslim religious law and the dignity of parties to a polygynous Muslim marriage should be equal to that attached to parties to a civil or customary marriage. The Court accordingly held that the term "spouse" in the Intestate Succession Act should be interpreted to include spouses in polygynous Muslim marriages.25

In the pivotal Bhe case26 the Constitutional Court also provided protection for multiple spouses. Although the Court was of the opinion that the legislature was the appropriate forum in which to amend the customary law of succession and the Intestate Succession Act, the Court held that as an interim solution section 1 of the Intestate Succession Act should be applied to all intestate estates. With reference to the calculation of the child's share when the deceased is survived by more than one spouse, the Court held that:

(a) A child's share in relation to the intestate estate of the deceased should be calculated by dividing the monetary value of the estate by a number equal to the number of the children of the deceased who have either survived or predeceased such deceased person but are survived by their descendants, plus the number of spouses who have survived such deceased person.

(b) Each surviving spouse should inherit a child's share of the intestate estate or so much of the intestate estate as does not exceed in value the amount fixed from time to time by the Minister for Justice and Constitutional Development by notice in the Gazette (R125 000 at present), whichever is the greater.

(c) Notwithstanding the provisions of subpar (b) above, where the assets in the estate are not sufficient to provide each spouse with the amount fixed by the Minister, the estate must be equally divided among the surviving spouses.27

Issues around succession, spouses and family life as well as legislation such as the Civil Union Act28 and court cases such as Bhe v President of the Republic of South Africa,29 Daniels v Campbell,30 Volks v Robinson,31 Hassam v Jacobs32 Govender v Ragavayah33 that recognise various forms of family relationships have thus now become well known, frequently discussed and even widely criticised.34

Before the decisions in these cases, religious marriages such as Muslim and Hindu marriages and customary marriages were recognised in South African law for limited purposes only,35 because they permit polygyny which was regarded as contrary to public norms. After these decisions, these marriages are recognised and in some instances the court has ordered the replacement or the word "spouse" by the words "spouse or spouses" in the relevant legislation.36 The fact that these relationships and polygonous marriages are now recognised is thus trite law but what remains to be seen is how some provisions containing these phrases are to be interpreted.

As a result of these decisions the South African Law Reform Commission is in the process of amending legislation containing the word "spouse", and a discussion paper is currently on the table in the form of Discussion Paper 129 (Project 25) Statutory law revision: Legislation administered by the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (2011).37 In this paper the addition of the words "or spouses" where the word "spouse" appears in certain sections of the Wills Act38 and of the Intestate Succession Act39 is recommended. Some of these recommendations have a very simple application, while others seem to lack in completeness.40

3 Simple application

The interpretation of certain legislative provisions by the inclusion of the phrase "or spouses" is not very complicated in some instances but in others may cause a number of problems.

In the case of section 4A(2)(b) of the Wills Act, the application is quite simple, provided one keeps the purpose of the section in mind. Section 4A(1) provides for the disqualification of an heir or his or her spouse from inheriting in terms of a will, if he or she was involved in the execution of the will. Section 4A(2) provides for exceptions to this rule and section 4A(2)(b) currently reads as follows:

... a person or his spouse who in terms of the law relating to intestate succession would have been entitled to inherit from the testator if that testator has died intestate shall not be thus disqualified to receive a benefit from that will: Provided that the value of the benefit which the person concerned or his spouse receives, shall not exceed the value of the share to which that person or his spouse would have been entitled in terms of the law relating to intestate succession.

The South African Law Reform Commission has recommended that "or spouses" be inserted after the words "or his spouse" wherever they occur in this section.41 If, for example, B is married to two sisters, C and D, the daughters of P, and B signs P's will as a witness, B, C and D will be disqualified from inheriting in terms of that will. C and D will, however, be entitled to inherit their intestate share. Consequently, had P been a widower with three daughters as his only intestate heirs and his estate is worth R300 000, they will each be entitled to R100 000. If P bequeathed R50 000 each to C and D in his will, they will inherit R50 000 each. Had he, however, left R150 000 to each, they will only inherit R100 000 each. The addition of the words "or spouses" is therefore not too problematic in this section.

In the case of section 1(4)(f) of the Intestate Succession Act,42 the application of the phrase is also relatively simple and the South African Law Reform Commission43 has also recommended that the provision should now read as follows:

1 Intestate succession

(1) If after the commencement of this Act a person (hereinafter referred to as the 'deceased') dies intestate, either wholly or in part, and-

(a)...

(Aa) is survived by more than one spouse, but not by a descendant, the intestate estate shall be divided equally among the spouses

(b)..

(Cc) is survived by more than one spouse as well as descendants-

(i) each spouse shall inherit a child's share of the intestate estate or so much of the intestate estate as does not exceed in value the amount fixed from time to time by the Minister of Justice by notice in the Gazette, whichever is the greater; and

(ii) the residue (if any) of the intestate estate shall be divided equally among the descendants;

(iii) where the intestate estate contemplated in paragraph (Cc)(i) is not adequate to provide each spouse with the amount fixed by the Minister, estate shall be divided equally among the surviving spouses.

The language of these provisions is clear and unambiguous and there can be no doubt as to the intention of the legislature.

The same cannot be said of the provisions of section 1(6) of the Intestate Succession Act.

4 Problematic interpretation of section 1(6) of the Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987

Section 1(6) of the Intestate Succession Act provides for substitution ex lege and currently reads:

(6) If a descendant of a deceased, excluding a minor or mentally ill descendant, who, together with the surviving spouse of the deceased, is entitled to a benefit from an intestate estate renounces his right to receive such a benefit, such benefit shall vest in the surviving spouse.

In Discussion Paper 129, the South African Law Reform Commission recommends44 that this provision be amended as follows to incorporate the courts' decisions re multiple spouses:

5.47 And, in respect of section 1(6), the following amendment is proposed:(6) If a descendant of a deceased, excluding a minor or mentally ill descendant, who, together with the surviving spouse or spouses of the deceased, is entitled to a benefit from an intestate estate renounces his or her right to receive such a benefit, such benefit shall vest in the surviving spouse.

The last part of the recommendation (here in italics) does not make it clear to which surviving spouse the repudiated benefit should devolve in the case of multiple surviving spouses or whether the survivors should share the benefit. At first glance, it will appear (if promulgated as is) as if the legislature had omitted amending the last part of the section by not adding "or spouses" at the end of the section and thus it would seem that the repudiated benefit should be shared by all the surviving spouses. This interpretation has also been suggested by Du Toit.45 He gives the example of a deceased in a polygonous marriage who is survived by two spouses and a child by each of these spouses. He follows the interpretation that if one of the children should repudiate his or her share of the deceased's intestate estate, that share will devolve to both the surviving spouses.

If, however, one has regard to the history and origin of section 1(6), and, perhaps more importantly, to the changing morals of society and the economic climate, one has to ask if this view is correct. In general,46 under common law, a surviving spouse was not entitled to inherit intestate from his or her deceased spouse.47 The reason for this was mainly that when it came to inheritance and the family's needs after a husband's death, a surviving spouse was usually regarded as being only of the female gender, and women in general were afforded very few rights. It was not considered necessary to provide for a surviving spouse's needs, as men had their own estates from which to maintain themselves while women were often left destitute and dependant on their children. As the role of women in society changed and women were afforded more rights, the position of women in succession also changed. Initially Act 22 of 1863 (Natal) declared that the wife of a deceased in a marriage out of community of property will be entitled to one half of his estate if they have no surviving lawful issue or, in the case of surviving issue, she was entitled to one third of his property.48

Legislation regarding succession was repealed by the Succession Act49 in 1934, which declared all surviving spouses, including widowers, intestate heirs and also made provision for the survivors of marriages in community of property. Furthermore, for the first time it provided for a child's share to be inherited by a surviving spouse.50 Under this act, the rule with regard to repudiation by any of the intestate heirs was that his or her share was inherited by the co-heirs, including the surviving spouse, and he or she could not be represented by his or her own descendants. The same was held to be the case where the intestate heir was disqualified from inheriting due to his own actions.51

The Succession Act, in turn, was repealed by the Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987, which came into operation in 1988. The Intestate Succession Act broadened the rights of a surviving spouse and with regard to renunciation or the disqualification of an heir provided as follows in section 1(4)(c):

[a]ny person who is disqualified from being an heir of the intestate estate of the deceased, or who has renounced his right to be such an heir, or any person who, by representing such first-mentioned person, would have been entitled to inherit had such a person not been so disqualified or had he not so renounced his right, shall be deemed not to have survived the deceased.

This provision was the result of many deliberations and comments and resulted in much criticism after its promulgation.52 The effect of this provision was that any heir who was entitled to inherit intestate but renounced his or her right was considered to be predeceased, with the result that his or her share of the estate was shared by the other intestate heirs, including the surviving spouse. Substitution by the surviving spouse or representation by the repudiating heirs' descendants was not possible. The repudiated share formed part of the estate and was shared by all heirs. The surviving spouse did not get the entire share that was repudiated but instead it formed part of the estate and was distributed among all the heirs according to the rules of intestate succession as laid down by the act.

The application of section 1(4)(c), however, partly defeated the purpose with which many descendants repudiated their inheritance in practice. A child often renounced the inheritance in order to benefit an ageing parent - in other words, in order to ensure that his or her parent inherited a greater share of the estate. Although such a parent did inherit a greater share in sharing the repudiated benefit with the other intestate heirs under section 1(4)(c), the intention of the repudiating child was usually that his or her surviving parent should inherit the entire repudiated share.53 This fact was recognised by the repeal of section 1(4)(c) of the act and the promulgation of section 1(6) and 1(7) as it currently reads. One would assume that the motivation behind a descendant's repudiation of a benefit will still today be to benefit his or her parent.

5 Other countries

Although it is always difficult to compare South African law of succession and especially intestate succession with that of other countries, it is possible to have a brief look at some principles which may be useful in our own interpretation of section 1(6) and 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act.

The principles applied under the repealed section 1(4)(c) conformed in many ways to the position under previous South African legislation.54 This position is still found in the modern succession law of certain European countries. When looking at the principles regarding repudiation (or renunciation) by descendants in an intestate estate, one has to bear in mind, however, that most European countries know a system of compulsory legal shares55 or, as previously known in South Africa, the legitimate portion, which has long been abolished locally.56 In the Netherlands, for example, an heir who repudiates an inheritance, whether by will or on intestacy, is considered never to have been an heir.57 This means that the other heirs will share in the repudiating beneficiary's share and that a surviving spouse will share to the same extent in the repudiated benefit. He or she would, however, not be in need of a greater share due to the statutory portion that he or she receives. In France, on the other hand, beneficiaries may negotiate with a surviving spouse to reduce their share to the benefit of the surviving spouse, but this is done with a view to receiving a "gift" (or testamentary bequest) from the survivor in the future.58 In these countries, the surviving spouse therefore gets a greater share of the estate, albeit not the entire share. The position in countries such as Italy may be contrasted with this position. In Italy the repudiated share devolves upon the descendants of the repudiating beneficiary.59 This position corresponds with the current position in South Africa under section 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act, which provides for representation by descendants of a beneficiary who is disqualified or repudiates in circumstances where section 1(6) does not apply. The position in these countries, however, does not take account of the fact that a child may repudiate with the sole purpose of benefitting an ageing parent and does not even consider this possibility due to the mandatory shares that surviving spouses inherit. These countries, of course, also do not even consider the position where multiple spouses survive the deceased, and therefore do not offer us much help in solving the problems currently under discussion. Suffice it to say that it is clear from the fact that surviving spouses receive a compulsory or statutory portion in all of these countries60 that his or her position needs to be safeguarded and is considered to be highly important.

6 Possible solution

From the discussion above, it would appear that there has always been a measure of see-saw riding between two views - the one being that the surviving spouse should receive the greatest benefit from a repudiated benefit, namely the entire repudiated share, and the other being that the benefit should be shared equally by all heirs, including the surviving spouse. What is clear, however, is that in modern times the surviving spouse has been considered worthy of protection and has been afforded more and more rights. The intention of the repudiating beneficiaries to benefit an ageing parent has also been afforded more weight. The repeal of section 1(4)(c) after the criticism levelled against it also seems to indicate that popular opinion favours the view that the surviving spouse should receive the entire repudiated benefit.

The question that now arises is how this purpose can be fulfilled under a new dispensation where multiple spouses may survive a deceased. The amendment to section 1(6) proposed in the Discussion Paper does not make it clear as to which surviving spouse should receive the repudiated benefit or whether they should all share in the benefit, as it simply states "such benefit shall vest in the surviving spouse".

As it currently reads, the section may lead to one of two results in a factual situation, depending on the interpretation allocated to the last part of the proposed amended section:

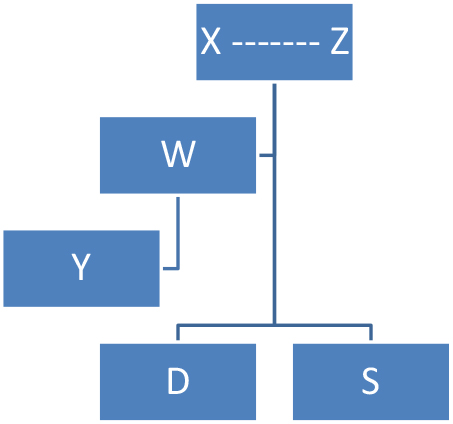

Example: Deceased X is survived by three spouses, B, C and D as well as by his son, S, born from his union with B and two daughters, F and E, born from his union with C. If we assume that X's estate (or his share in any joint estate) amounts to R600 000, a child's share will amount to R100 000 and each spouse will therefore inherit R125 000. The remaining R225 000 will be shared equally between the children, S, F and E, to the amount of R75 000 each. This will be the solution in a simple case where repudiation does not play a part.

1

1

If, however, one of the beneficiaries decides to repudiate his or her share, one of two results may be possible:

Result 1: If, for example, S decides to repudiate his share, his mother B may inherit an extra R75 000 if one assumes that he intended to benefit his parent, and if one interprets the proposed amendment to the section as referring to a single spouse, namely his parent. In other words, if "such benefit shall vest in the surviving spouse" is taken literally to refer only to one spouse, namely the parent (S's mother) of the repudiating heir.

Result 2: If, on the other hand, one follows the rules of statutory interpretation and assumes that the legislature had omitted amending the last part of the section by not adding "or spouses" at the end of the section as was done earlier in the section and throughout all the proposed amendments, a different result may be arrived at. In such a case, the R75 000 may have to be shared between B, C and D, in which case each of them will receive only R25 000.

To attain certainty on the position and in order to ensure that the prevailing intention of repudiating beneficiaries to benefit an ageing parent (as explained above), is adhered to, it is suggested that the last sentence of section 1(6) should read: "such benefit shall vest in the surviving spouse who is the parent or ascendant of such descendant".

This wording will ensure that only the parent of the repudiating beneficiary benefits and does not have to share with all other surviving spouses. In the example above, there will be no doubt that Result 1 will be the solution to the division of the estate and that the repudiating beneficiary's parent will inherit the repudiated share in toto.

7 The position under section 1(7)

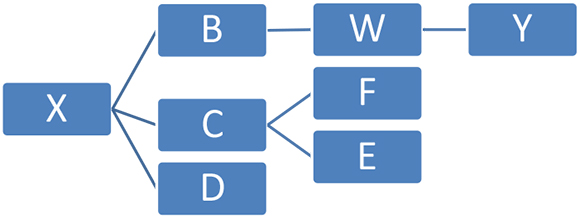

Section 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act provides that descendants of a descendant who is disqualified from inheriting or who repudiates may represent such a descendant in circumstances where section 1(6) does not apply. In terms of section 1(7), the benefit which that heir would have received devolves as if the heir had died immediately before the deceased died. This section makes provision for the following simple example:

Deceased X, who was married to Z, is survived by a daughter, D, a son, S, and a grandson, Y, the son of X's son, W.

In this example, in a simple, uncomplicated case Z will inherit a child's share or R125 000, whichever is the most, and the children will inherit the residue of the estate. If X's estate, for example, amounts to R800 000, a child's share to be inherited by W will amount to R200 000, and W, D and S will each inherit R200 000.

In this example, if W is predeceased and Z is still alive at X's demise, Y will inherit W's R200 000 in his stead in terms of section 1(1)(c). If W repudiates, however, section 1(6) applies as illustrated above and Z will inherit W's share of R200 000. And if there is no surviving spouse it will go to Y in terms of section 1(7). This application of section 1(7) under the previous dispensation in a simple example such as the above does not provide for a scenario where multiple spouses survive the deceased. The application becomes much more complicated and questions arise as to the position of the descendant (in this case Y, who inherited in W's stead) where there is more than one spouse and some of them survive the deceased.

The South African Law Reform Commission made no mention of section 1(7) in the Discussion Paper, but its application under a dispensation where more than one spouse may be the survivors of the deceased warrants a closer look.

Jamneck et al61 explains the application of the section as it currently stands as follows:

It is important to note, however, that where an heir repudiates an inheritance one must apply section 1(7) in conjunction with section 1(6) of the Act because section 1(7) is 'subject to' section 1(6). This means that the following is the position: If an intestate heir of the deceased repudiates an inheritance and the deceased is survived by a surviving spouse, the surviving spouse, will inherit the repudiating heir's share. However, if the deceased is not survived by a surviving spouse then the repudiating heir will be deemed to have predeceased the deceased and his or her descendants will inherit by representation (per stirpes). In the latter scenario, should it turn out that the repudiating heir has no descendants, the inheritance will pass to the intestate heirs of the deceased according to the normal rules of intestate succession. From the wording of section 1(6) it is clear that the section will not apply when an heir is disqualified.

If we now take into account the possibility that the deceased may be survived by more than one spouse, the application as explained by these authors should include the words "or spouses". This, however, brings one to the situation where it may never be possible for a descendant of a repudiating heir to represent him or her if there are several surviving spouses.

Example: Deceased X is survived by three spouses, B, C and D as well as by his son, W, born from his union with B, and two daughters, F and E, born from his union with C. He is also survived by his grandson, Y, the son of W.

In this example, if B (one of X's spouses and mother of W) had predeceased X, and W repudiates his inheritance, the interpretation of section 1(7) read with the proposed amendment of section 1(6) will lead to the conclusion that C and D will inherit the portion meant for S. The reason for this conclusion is that the application of section 1(7) is subject to section 1(6) and therefore section 1(6) should be applied as there still are [other] surviving spouses (except W's mother). This will mean that Y's chances of ever representing his father become very slim if his grandfather has several spouses, unless a different interpretation is afforded to section 1(6).

If, however, section 1(6) is amended as suggested above, namely to refer to the parent of the repudiating heir, the descendants of the repudiating heir will represent him or her in the case where the parent of the repudiating heir is no longer alive. In the example above, this will mean that Y will represent W because his grandmother, B (W's mother), is no longer alive to inherit the portion repudiated by her son, W. With such an interpretation or amendment, the descendants of the repudiating heir will be ensured of their inheritance and it will not devolve to other surviving spouses.

8 Conclusion

Interestingly enough, Discussion Paper 129 does not make specific mention of section 2C of the Wills Act62 but refers only to the addition of the words "or spouses" in section 4A(2)(b). The wording of section 2C(1) and 2C(2) is similar to that of section 1(6) and 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act and the legio interpretation problems of these sections have been pointed out before.63 The scope of this article does not extend to these problems, but it is suggested that the South African Law Reform Commission should also consider section 2C and its practical application if a testator is survived by multiple spouses. Furthermore, as pointed out by Rautenbach and Meyer,64 the problems created by the dual status afforded to certain women as both "spouse" and "descendant" in terms of the Reform of Customary Law of Succession and Regulation of Related Matters Act65 have by no means been addressed.

For the moment it will suffice to request that the application of section 1(6) and 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act at least be made clear. We may conclude that, although Discussion Paper 129 does not make it clear as to which surviving spouse should benefit in the case of repudiation by an heir, the solution is relatively simple. The problem may be solved by the addition of the words "who is the parent or ascendant of such descendant" in order to give effect to the intention of a repudiating heir.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Literature

Bekker JC and Koyana DS "The judicial and legislative reform of the customary law of succession" 2012 De Jure 568-584 [ Links ]

Cardillo FS "Italy" in Garb L (ed) International Succession (Kluwer Law International London 2004) 355-377 [ Links ]

Cooke A "Choice, heterosexual life partnerships, death and poverty" 2005 SALJ 542 -557 [ Links ]

Corbett MM et al The Law of Succession in South Africa (Juta Cape Town 1980) [ Links ]

Corbett MM, Hofmeyr G and Kahn E The Law of Succession in South Africa 2nd ed (Juta Cape Town 2001) [ Links ]

Du Toit F "The Constitutional Family in the Law of Succession" 2009 SALJ 463-488 [ Links ]

Hayton D European Succession Laws (Jordans Bristol 1998) [ Links ]

Heaton J "An overview of the current legal position regarding heterosexual life partnerships" 2005 THRHR 662-670 [ Links ]

Jamneck J "Die interpretasie van artikel 2C van die Wet op Testamente 7 van 1953: Deel I" 2002 THRHR 223-231 [ Links ]

Jamneck J "Die interpretasie van artikel 2C van die Wet op Testamente 7 van 1953: Deel II" 2002 THRHR 386-396 [ Links ]

Jamneck J "Die interpretasie van artikel 2C van die Wet op Testamente 7 van 1953: Deel III" 2002 THRHR 532-538 [ Links ]

Jamneck J et al The Law of Succession in South Africa 2nd ed (Oxford University Press Cape Town 2012) [ Links ]

Jordaan RA Die Eis van Afhanklikes om Onderhoud (LLD-thesis Unisa 1987) [ Links ]

Joubert CP "Repudiasie deur 'n erfgenaam" 1958 THRHR 183-219 [ Links ]

Krüger R "Appearance and reality: Constitutional protection of the institutions of marriage and the family" 2003 THRHR 285-291 [ Links ]

Lind C "Domestic partnerships and marital status discrimination" 2005 Acta Juridica 108-130 [ Links ]

Pintens W "Tendencies in European Succession Law" in Frantzen T (ed) Inheritance Law - Challenges and Reform: A Norwegian-German Research Seminar (BWV Berlin 2013) 9-23 [ Links ]

Rautenbach C and Meyer MM "Lost in translation: is a spouse a spouse or a descendant (or both) in terms of the reform of customary law of Succession and regulation of related matters act?" 2012 TSAR 149-160 [ Links ]

Robinson JA "An overview of the provisions of the South African bill of rights with specific reference to its impact on families and children affected by the policy of apartheid" 1995 Obiter 99-114 [ Links ]

Roubache J "France" in Garb L (ed) International Succession (Kluwer Law International London 2004) 218-235 [ Links ]

South African Law Commission Report (Project 22): Review of the Law of Succession (SALC Pretoria 1991) [ Links ]

South African Law Commission Discussion Paper 129 (Project 25): Statutory Law Revision: Legislation Administered by the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (SALC Pretoria 2011) [ Links ]

Schoeman-Malan MC "Recent developments regarding South African common and customary law of succession" 2007 PELJ 1-33 [ Links ]

Ten Wolde MH "The Netherlands" in Garb L (ed) International Succession (Kluwer Law International London 2004) 434-445 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe NJ and Rowland CJ Die Suid-Afrikaanse Erfreg 6th ed (JP Van der Walt en Seuns Pretoria 1990) [ Links ]

Wood-Bodley MC "Intestate succession and gay and lesbian couples" 2008 SALJ 46-62 [ Links ]

Case law

Amod v Multilateral Motor Vehicle Accidents Fund 1999 4 SA 1319 (SCA)

Bhe v Magistrate, Khayelitsha; Shibi v Sithole; South African Human Rights Commission v President of the Republic of South Africa 2005 1 SA 580 (CC)

Chikosi v Chikosi 1975 2 SA 644 (R)

Daniels v Campbell 2003 3 All SA 139 (C)

Daniels v Campbell 2004 5 SA 331 (CC)

Dawood v Minister of Home Affairs; Shalabi v Minister of Home Affairs; Thomas v Minister of Home Affairs 2000 3 SA 936 (CC)

Du Toit v Minister for Welfare and Population Development 2002 10 BCLR 1006 (CC)

Ex parte Soobiah: In re Estate Pillay 1948 2 All SA 76 (N)

Gory v Kolver 2007 4 SA 97 (CC)

Govender v Ragavayah 2009 1 All SA 371 (D)

Hassam v Jacobs 2008 4 All SA 350 (C)

Hassam v Jacobs 2009 5 SA 572 (CC)

Ismail v Ismail 1983 1 SA 1006 (A)

Kalla v The Master 1995 1 SA 261 (T)

Robinson v Volks 2004 2 All SA 61 (C)

Rylands v Edros 1997 2 SA 690 (C)

S v Johardien 1990 1 SA 1026 (C)

Seedat's Executors v The Master (Natal) 1917 AD 302

Vitamin Distributors v Chungebryen 1931 WLD 55

Volks v Robinson 2005 5 BCLR 446 (CC)

Legislation

[Wills] Act 22 of 1863 (Natal)

[Wills] Act 23 of 1874

Administration of Estates Proclamation 28 of 1902

Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992

Black Administration Act 38 of 1927

Black Laws Amendment Act 38 of 1927

Child Care Act 74 of 1983

Civil Proceedings Evidence Act 25 of 1965

Civil Union Act 17 of 2006

Code Civil (France)

Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act 130 of 1993

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Insolvency Act 24 of 1936

Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987

Maintenance of Surviving Spouses Act 27 of 1990

Marriage Act 25 of 1961

Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 120 of 1998

Reform of Customary law of Succession and Regulation of Related Matters Act 11 of 2009

Succession Act 13 of 1934

Wills Act 7 of 1953

Internet sources

Cour de Cassation 2009 Arrêt no 855 du 8 juillet 2009 (07-18.041) - Cour de cassation - Premiere chambre civile http://www.courdecassation.fr/publications_26/arrets_publies_ 2986/premiere_chambre_civile_3169/2009_3328/juillet_2009_3211/ 855_8_13416.html accesed 5 March 2014 [ Links ]

Cour de Cassation 2010 Arrêt no 475 du 12 mai 2010 (09-11133) - Cour de cassation - Premiere chambre civile http://www.courdecassation.fr/jurisprudence_2/premiere_chambre_ civile_568/475_12_16245.html accesssed 5 March 2014 [ Links ]

De Rechtspraak 2013 Rechtbank Rotterdam: Team familie 1, zaaknummer / C/10/408938 / HA ZA 12-798, 2 oktober 2013 http://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBROT:2013:8006 accessed 5 March 2014 [ Links ]

De Rechtspraak 2013 Rechtbank Noord-Holland: Afdeling privaatrecht, zaaknummer C/14/143559/ HA A 13-33, 4 september 2013 http://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2013:7676 accessed 5 March 2014 [ Links ]

De Rechtspraak 2014 Rechtbank Overijssel: Team kanton en handelsrecht, zaaknummer C/08/148478 / KG ZA 13-430, 3 januari 2014 http://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBOVE:2014:12 accessed 5 March 2014 [ Links ]

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

PELJ Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal

SALC South African Law Commission

SALJ South African Law Journal

THRHR Tydskrif vir die Hedendaagse Romeins-Hollandse Reg

TSAR Tydskrif van die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg

1 Du Toit 2009 SALJ 487.

2 Robinson 1995 Obtter 106.

3 Dawood v Minsster of Home Affairs; Sha/abi v Mnnister of Home Affairs; Thomas v Minister of Home Affairs 2000 3 SA 936 (CC); Du Toit v Minister for Welfare and Population Development 2002 10 BCLR 1006 (CC).

4 See the discussion below.

5 The Discussion Paper (SALC Discussion Paper 129 (Project 25)) covers various topics but this paper will concentrate on issues relating to succession and specifically those relating to substitution in terms of the Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987. See the discussion below.

6 Although the cases discussed here have been discussed many times in other publications, it is necessary to give a brief summary of each again in order to reach a logical determination of the application of the terms "spouse" or "spouses" in terms of ss 1(6) and 1(7) of the Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987. See Heaton 2005 THRHR 662 et seq and sources mentioned there for discussions of these cases.

7 Volks v Robinson 2005 5 BCLR 446 (CC).

8 Maintenance of Surviving Spouses Act 27 of 1990.

9 Robnson v Volks 2004 2 All SA 61 (C).

10 Section 15(3)(a)(i) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

11 For a detailed discussion of this case, see Cooke 2005 SALJ 542; Lind 2005 Acta Juridica 108130.

12 Gory v Kolver 2007 4 SA 97 (CC).

13 Civil Union Act 17 of 2006.

14 S 1 of the Civil Union Act 17 of 2006.

15 Marriage Act 25 of 1961.

16 Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 120 of 1998.

17 Du Toit 2009 SALJ 474.

18 See the Insolvency Act 24 of 1936; the Black Laws Amendment Act 38 of 1927; the Civil Proceedings Evidence Act 25 of 1965; the Child Care Act 74 of 1983.

19 For example, the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act 130 of 1993 and the Births and Deaths Regsstration Act 51 of 1992. Also see the acts mentioned in n18.

20 See Kala v The Master 1995 1 SA 261 (T); Ry/ands v Edros 1997 2 SA 690 (C); Amod v MultilateralMotor Vehicle Accidents Fund 1999 4 SA 1319 (SCA).

21 Daniels v Campbell 2004 5 SA 331 (CC).

22 Daniels v Campbell2003 3 All SA 139 (C).

23 See also Govender v Ragavayah 2009 1 All SA 371 (D) re a monogamous Hindu marriage.

24 Hassam v Jacobs 2008 4 All SA 530 (C); Hassaam v Jacobs 2009 5 SA 572 (CC).

25 See also Du Toit 2009 SALJ 470.

26 Bhe v Magistrate, Khayelitsha; Shibi v Stthoee; South African Human Rights Commsssion v President of the Repubiic of South Africa 2005 1 SA 580 (CC) (the Bhe case). See Bekker and Koyana 2012 De Jure 571 et seq for a discussion of the case.

27 See the Bhe case paras 101-124, 136.

28 Civil Union Act 17 of 2006. See also the Recognttion of Customary Marriages Act 120 of 1998.

29 Bhe v Magistrate, Khayeiitsha; Shbi v Stthoee; South African Human Rights Commission v President of the Republic of South Africa 2005 1 SA 580 (CC).

30 Daniels v Campbell 2004 5 SA 331 (CC).

31 Volks v Robinson 2005 5 BCLR 446 (CC).

32 Hassam v Jacobs 2009 5 SA 572 (CC).

33 Govender v Ragavayah 2009 1 All SA 371 (D).

34 See for example, Krüger 2003 THRHR 285-291; Lind 2005 Acta Juridcca 108-130; Schoeman-Malan 2007 PER; Du Toit 2009 SALJ 463-488; Wood-Bodley 2008 SALJ 46-62; Rautenbach and Meyer 2012 TSAR 149-160.

35 See Seedat's Executors v The Master (Nata)) 1917 AD 302; Vitamin Dsstributors v Chungebryen 1931 WLD 55; Ex parte Soobiah: In re Estate Pll/ay 1948 2 All SA 76 (N); Chikosi v Chikosi 1975 2 SA 644 (R); Ismail v Ismall 1983 1 SA 1006 (A); S v Johardien 1990 1 SA 1026 (C). See also the Black Administration Act 38 of 1927 and the Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992.

36 Hassam v Jacobs 2008 4 All SA 350 (C) 358-358, confirmed by the Constitutional Court in Hassam v Jacobs 2009 5 SA 572 (CC).

37 The Discussion Paper (SALC Discussion Paper 129 (Project 25)) covers various topics, some of which are not relevant to the current discussion.

38 Wills Act 7 of 1953.

39 Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987

40 See the discussion below.

41 SALC Dsscussion Paper 129 (Project 25) para 5.11.

42 Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987.

43 SALC Discussion Paper 129 (Project25) para 5.46.

44 SALC Discussion Paper 129 (Project25) para 5.47.

45 See Du Toit 2009 SALJ 487 fn 126.

46 Van der Merwe and Rowland Suid-Afrikaanse Erfreg 67 refers to a dispute in certain instances between the Aasdomsrecht and the new Schependomsrect as well as certain decisions where surviving spouses were regarded as intestate heirs. As the focus of this research is not a complete historical overview, these issues will not be discussed in detail here.

47 Corbett, Hofmeyr and Kahn Law of Succession 566. See Van der Merwe and Rowland Suid-Afrkkaanse Erfreg 25-66 for an overview of the Aasdomsrecht and Schependomsrect and the Octrooi of 1661, which applied in early South African law.

48 Section 5 of Act 22 of 1863 (Natal). See Van der Merwe and Rowland Suid-Afrikaanse Erfreg 67 fn35 for the wording of this section.

49 Succession Act 13 of 1934.

50 See s 1 of the Succession Act 13 of 1934. See also Corbett et al Law of Succession 588-590.

51 For the position under the common law, see Joubert 1958 THRHR 183 ev.

52 See Corbett, Hofmeyr and Kahn Law of Succession 575; SALC Report (Project 22) para 6.

53 Corbett, Hofmeyr and Kahn Law of Succession 575.

54 See the discussion above of Act 22 of 1863 (Natal) and the Succession Act.

55 Hayton European Succession Laws 49-52, 161, 171, 193, 256-259; Roubache "France" 220-221; Cardillo F"Italy" 359; Ten Wolde "The Netherlands" 435-436; Pintens "Tendencies in European Succession Law" 10.

56 The legitimate portion was abolished in South Africa in toto by 1902 - see Act 23 of 1874 and Proclamation 28 of 1902. For a discussion of the legitimate portion and the protection of the family after death, see Jordaan Eis van Afhanklkkes(LLD-thesis 1987) in general.

57 Hayton European Succession Laws 261. The same applies in France - Code Civil Ch IV, art 805.

58 In France the surviving spouse is also entitled to a set portion (la réserve) which depends on the number of surviving children - Code Civil Ch IV, art 757. See in general Cour de Cassation 2009 http://www.courdecassation.fr/publications_26/arrets_publies _2986/premiere_chambre_civile_3169/2009_3328/juillet_2009_3211/855_8_13416.html; Cour de Cassation 2010 http://www.courdecassation.fr/jurisprudence_2/premiere_chambre_civile_ 568/475_12_16245.html.

59 Roubache "France" 357. In France, the same applies in the absence of an agreement - Code Civil Ch IV, art 805-1.

60 The position of the surviving spouse has also improved over time - see Pintens "Tendencies in European Succession Law" 11, 14. See in general on the application of the legitimate portion, article 10:4 NBW; De Rechtspraak 2014 http://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBOVE:2014:12; De Rechtspraak 2013 http://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBROT:2013:8006; De Rechtspraak 2013 http://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2013:7676;

61 Jamneck et al Law of Succession 39.

62 Wills Act 7 of 1953.

63 See Jamneck 2002a THRHR 223-231; Jamneck 2002b THRHR 386-396; Jamneck 2002c THRHR 532-538.

64 Rautenbach and Meyer 2012 TSAR 149-160.

65 Reform of Customary Law of Succession and Regulation of Related Matters Act 11 of 2009.