Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.16 n.5 Potchefstroom May. 2013

NOTES

Unpacking the right to plain and understandable language in the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008

PN StoopI; C ChürrII

IBCom, LLB, LLM (UP), LLD (UNISA). Associate Professor in the Department of Mercantile Law, School of Law, University of South Africa . Email: stooppn@unisa.ac.za

IILLB, LLM (UP), LLD (UNISA). Senior Lecturer in the Department of Mercantile Law, School of Law, University of South Africa. Email: churrc@unisa.ac.za

SUMMARY

The Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 came into effect on 1 April 2011. The purpose of this Act is, among other things, to promote fairness, openness and respectable business practice between the suppliers of goods or services and the consumers of such good and services. In consumer protection legislation fairness is usually approached from two directions, namely substantive and procedural fairness. Measures aimed at procedural fairness address conduct during the bargaining process and generally aim at ensuring transparency. Transparency in relation to the terms of a contract relates to whether the terms of the contract terms accessible, in clear language, well-structured, and cross-referenced, with prominence being given to terms that are detrimental to the consumer or because they grant important rights. One measure in the Act aimed at addressing procedural fairness is the right to plain and understandable language. The consumer's right to being given information in plain and understandable language, as it is expressed in section 22, is embedded under the umbrella right of information and disclosure in the Act. Section 22 requires that notices, documents or visual representations that are required in terms of the Act or other law are to be provided in plain and understandable language as well as in the prescribed form, where such a prescription exists. In the analysis of the concept "plain and understandable language" the following aspects are considered in this article: the development of plain language measures in Australia and the United Kingdom; the structure and purpose of section 22; the documents that must be in plain language; the definition of plain language; the use of official languages in consumer contracts; and plain language guidelines (based on the law of the states of Pennsylvania and Connecticut in the United States of America).

Keywords: Plain language (plain and understandable language), Transparency, Procedural fairness, Consumer rights, Consumer contracts; Contractual fairness.

CLARITY

Frequently, though we talk about transparency,

We proliferate opacity

When what we need is clarity.

Nowadays, there's an ever-growing tendency

To obfuscate with much prolixity,

When what we need is clarity.

You wrote something long; that is wrong, it will not do.

Keep it plain and short and the message will get through.

Just write with ...

Clarity means abandoning obscurity

And preferring more simplicity.

Write English as it ought to be.

Yes, what we need is clarity.1

1 Introduction

The South African National Consumer Protection Act2 (the Act) came into effect on 1 April 2011. The purpose of this Act is inter alia to promote fairness, openness and respectable business practice between the suppliers of goods or services and the consumers of such goods and services. The Act furnishes consumers with augmented specific consumer rights, grounds for product liability, and certain automatic warranties pertaining to the quality of goods.

One of the most important aspects addressed in the Act is "language". Section 22 of the Act stipulates that all information should be in plain and understandable language. The phrase "plain and understandable" for purposes of consumer contracts can be equated to "clear"; "understandable" and "user-friendly".3 This means that difficult legal concepts and documents should be transformed or simplified into a language that is plain, understandable, clear, and user-friendly.

However, the concept "plain and understandable language" will itself become clear and understandable only when the structure and purpose of section 22; the documents required to be in plain language; the definition of plain language; and the use of official languages in consumer contracts and guidelines pertaining to plain language contracts are fully unpacked and discussed. Moreover, developments and the legal position in Australia and the United Kingdom concerning plain language in consumer contracts will be briefly introduced. The status quoin the United Kingdom is relevant to the extent that the country is the leader in the so-called "Plain English Movement". This movement became more powerful as part of the consumer movement in the 1970s, and from here, the need and demand for plain language in consumer contracts continued to grow stronger - not only in the United Kingdom, but worldwide. The Australian case is relevant to the extent that the "plain language concept" in consumer contracts is fairly new and the country's legislation has rencently underwent some reform in this regard. It will be concluded that when consumer contracts are complex and multifaceted, simplicity and plainness may be the only way to make them understandable. Lastly, the law of the states of Pennsylvania and Connecticut in the United States of America will also be considered in brief. These states' legislators have prescribed clear formal, general and visual style guides for contracts.

2 The impact of plain language measures on contractual fairness

The law of contract forms the basis of most aspects of consumer-protection law. Therefore, before we continue to the analysis of the plain language provisions contained in the Act, it is important to explain the more philosophical or theoretical background to plain language and the role plain language plays in contractual fairness.

Traditionally the law of contract merely provides a framework within which contracts are enforced,4 without concern for their context.5 Legislation is then often adopted to address this imbalance, by regulating the fairness of contract terms, for instance.6

The starting point for consumer protection legislation is the imbalance, from a legal and economic perspective, between suppliers and consumers in the making of a contract, in the terms of a contract, and in the enforcement of a contract. This imbalance may arise because the traditional (or classical) law of contract applies regardless of the identity of the parties, their relationship to one another, the subject matter of the contract, and the social context of the contract.7

In consumer protection legislation fairness is usually approached from two angles, namely substantive and procedural fairness. As the aim of these two "approaches" and therefore the moment at which reasonableness is relevant differ, it makes sense to distinguish between them, even though they are interdependent.

Measures aimed at procedural fairness address conduct during the bargaining process and generally aim at ensuring transparency.8 Transparency has two elements: (a) transparency in relation to the terms of a contract, and (b) transparency in the sense of not being positively misled, pre-contractually or during the performance of a contract, as to aspects of the goods, service, price, and terms. Transparency in relation to the terms of a contract relates to whether or not the contract terms are accessible, in clear language, well-structured, and cross-referenced, with prominence being given to terms that are detrimental to the consumer or because they grant important rights.9 In a nutshell, one could say that a contract is procedurally fair where it has been concluded voluntarily.

Substantive fairness relates to procedural fairness through the requirement of transparency. That is because a high level of transparency means that the consumer is placed in a position at least to have a chance of being able to exercise a reasonable degree of informed consent. So what is a high level of transparency? A good level of transparency has to do with, among other things, aspects such as information disclosure, awareness of the terms, the size of the print, the clarity of the language, and the interpretation and format, as these procedural factors relate to circumstances surrounding the manner in which agreement is reached.10 Transparency can be a negative control which allows at most the elimination of unclear and incomprehensible contract terms, or it may provide for positive duties, such as the duty to explain and summarise the implications of certain contractual terms.11 A high level of transparency means that the consumer is placed in a position at least to have a chance of being able to exercise a reasonable degree of informed consent. Transparency therefore enhances choice and fairness substantively.12

Although procedural fairness and measures aimed at procedural fairness may have limitations, the requirement of plain and understandable language, as set out in section 22 of the Consumer Protection Act, in a multilingual South African context where consumers are often only functionally literate, is probably the most important pro-active fairness measure contained in the Act.

3 The development of plain language in consumer contracts in Australia and the United Kingdom

Plain language is not an unfamiliar term and has been the focal point of wide-ranging discussion, research and legislation for a long time in countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom. The origins and evolution of the "plain language movement" date back centuries. Garner describes plain language as "the language of the King James version of the Bible and it has a long literary tradition in the so-called Attic style of writing" (however, many words derived from other languages are used in this version of the Bible).13 In turn, the Attic style is associated with well-known Athenian orators of the fourth and fifth centuries BCE and the Attic style is described as "active, direct, forceful and exemplified purity and simplicity".14 The simple, uncomplicated and plain language styles can be traced down through the centuries to the 20th century, when reading researchers such as Flesch (in 1979) developed and expanded reading scales in order to examine and investigate readability levels of documents.15

3.1 Australia

The plain language movement in Australia has already been active for decades.16 However, the concept "plain language" pertaining to consumer contracts is fairly new in Australian law.

In 2010, the Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament approved legislation implementing the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). This legislation regulates, among other things, unfair terms in standard form consumer contracts as well as the unfair contract terms law.17 The purpose of the ACL is to protect and safeguard consumers and to ensure fair trading in Australia.18 The ACL is contained in schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act, 2010, which is the new name of the Trade Practices Act, 1974.19

Sections 23 and 24 of the Competition and Consumer Act, 2010 are of cardinal importance to this article, since they stipulate what unfair terms of consumer contracts are and the meaning of unfair is clearly explained. It is important to note that the ACL does not specifically provide for "plain language" as such, but provides that a term is transparent if the term is "expressed in reasonably plain language".20

Section 23 stipulates as follow:

Unfair terms of consumer contracts

(1) A term of a consumer contract is void if:

(a) the term is unfair; and

(b) the contract is a standard form contract.

(2) The contract continues to bind the parties if it is capable of operating without the unfair term.

(3) A consumer contract is a contract for:

(a) a supply of goods or services; or

(b) a sale or grant of an interest in land; to an individual whose acquisition of the goods, services or interest is wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household use or consumption.

Section 24 stipulates the following:

Meaning of unfair

(1) A term of a consumer contract is unfair if:

(a) it would cause a significant imbalance in the parties; rights and obligations arising under the contract; and

(b) it is not reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term; and

(c) it would cause detriment (whether financial or otherwise) to a party if it were to be applied or relied on.

(2) In determining whether a term of a consumer contract is unfair under subsection (1), a court may take into account such matters as it thinks relevant, but must take into account the following:

(a) the extent to which the term is transparent;

(b) the contract as a whole.

(3) A term is transparent if the term is:

(a) expressed in reasonably plain language; and

(b) legible; and

(c) presented clearly; and

(d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1)(b), a term of a consumer contract is presumed not to be reasonably necessary in order to protect legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term, unless that party proves otherwise.

The question now is what exactly is meant by "reasonably plain language". As already stated, no specific provision is made for the term "reasonably plain language" under the ACL, and it is therefore assumed that reasonably plain language in consumer contracts refers to contracts that are "easily legible", "clearly expressed" and, if printed or typed, be in a "minimum 10 point Times New Roman font, or a minimum of an equivalent size".21

Moreover, communication is the main purpose of language and it is submitted that the purpose of plain language is to communicate in a clear and effective way. In other words, the needs of the audience (the consumers) take precedence over any other consideration.22 The following definition of plain language was therefore recommended:23

A communication is in plain language if it meets the needs of its audience - by using language, structure, and design so clearly and effectively that the audience has the best possible chance of readily finding what they need, understanding it, and using it.

A second question that can be asked is how a court would determine if a term is "unfair"? When a court has to determine whether a term of a standard form consumer contract is unfair, any matter that the court believes is relevant and pertinent may be taken into consideration.24 The court is, however, obliged to take the following two factors into consideration:25 (a) the extent to which the term is transparent; and (b) the contract as a whole.

A lack of transparency regarding a term in a standard form consumer contract has serious consequences and may cause imbalances for contract parties' rights and obligations. It is therefore important for a court to take the transparency requirement into consideration. Only the court has jurisdiction to determine whether a term is transparent or obscure.26 Terms which may not be considered transparent include terms that are concealed in fine print or schedules, or that are expressed and phrased in legalese or in complex, difficult or technical language.27

Although the court is required to take into account the transparency requirement, this does not mean that a contract that does not meet the transparency requirement is unfair. It should be remembered that transparency "will not necessarily overcome underlying unfairness in a contract term".28 The wording of the United Kingdom counterpart regarding unfair contract provisions differs somewhat from the Australian unfair contract terms provisions.29 The United Kingdom's laws refer to 'plain and intelligible language' while the Australian laws refer to 'transparency'. The finding of Smith J in the case of Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc30 shed some light in this regard:

Regulation 6(2) ... requires not only that the actual wording of individual clauses or conditions be comprehensible to consumers, but that the typical consumer can understand how the term affects the rights and obligations that he and the seller or supplier have under the contract.

The determining of fairness concerning a particular contractual term can therefore not be performed in isolation. It is therefore crucial that terms be assessed in the light of the contract as a whole.31 When there is a particular term in the contract that is to the benefit of the consumer, such an advantageous or favourable term may not counterbalance an unfair term if the consumer is unaware of it.32 It is thus clear that a court will be able to determine the "unfairness" of a term only if the transparency factor and the 'contract as a whole' factor are taken into account.

3.2 United Kingdom

'Plain English' is not a new concept in the United Kingdom and had already left its mark during the fourteenth century.33 The first English dictionary saw the light in 1604 with an explanation that "hard vsuall English words, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or Frensch. &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of Ladies, Gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons".34

From the seventeenth century, the Protestants, especially the Quakers, were big proponents of the use of "simple style", which was commonly known as "plain language".35

During the 1970s the "plain English movement" was started by several consumer groups and the mass media were used in order to "ridicule examples of obscurity in legal documents and government forms". In 1979 the "Plain English Campaign" was established by Muller and Cutts, who strove to fight "gobbledygook-legalese, small print and bureaucratic language". This "Plain English Campaign" has grown over the years and is still a fast-growing and successful phenomenon today.36

A need for the protection of consumers arose over the years, and the United Kingdom was left with no choice other than to develop and implement the necessary legislation.

As the law currently stands, there are two major pieces of legislation which deal with unfair contract terms, and this legislation also contains certain provisions relating to plain language in consumer contracts. They are the Unfair Contract Terms Act, 1977 (UCTA) and the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations, 1999 (UTCCR).37

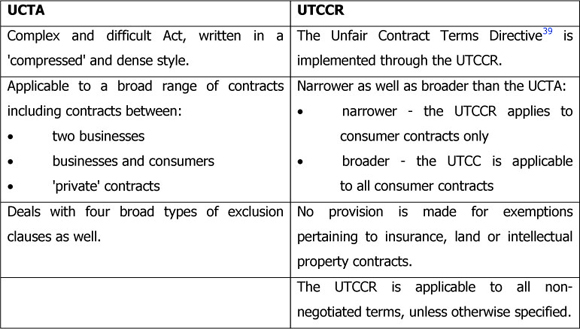

The following table provides a brief overview and comparison between the UCTA and the UTCCR:38

As for plain language in consumer contracts, the UTCCR subjects consumer contracts to two important requirements:40 (a) consumer contracts should be written in "plain, intelligible language"; and (b) consumer contracts should be "fair".

Regulation 7 of the UTCCR stipulates that it is the responsibility of sellers or suppliers to ensure that any written term of a consumer contract is expressed in "plain, intelligible language". This concept applies in three ways:41

(a) If the meaning of a contract term is in question or doubtful, the courts will choose the interpretation that is most favourable to the consumer.42 This is where the well-known common-law rule is reflected: "an ambiguous written term should be construed against the party putting it forward".43

(b) Part 8 of the Enterprise Act, 2002 stipulates that enforcement bodies are authorised to remove terms which are not in "plain, intelligible language".

(c) A term pertaining to the "adequacy of the price" or "main subject matter" will be reviewable for fairness if such a term(s) is not drafted in "plain, intelligible language".

The fairness of any term(s) in a consumer contract may be tested by a court unless such a term(s) falls within one of the following exemptions:44

(a) negotiated terms;

(b) terms which reflect the existing law; or

(c) terms which relate to the main subject matter of the price.

Moreover, in 2002 a Consultation Paper was prepared and the meaning of 'plain, intelligible language' came under "review" again. It was determined how this term compared to the UCTA and the outcome was as follows:45

A term was not plain and intelligible if it was hard to read, not readily accessible or hidden in confusing layout. ... all these factors taken together amounted to a requirement of "transparency". A term should only be exempt if it was transparent.

Clause 14(3) of the Draft Unfair Contract Terms Bill, 2005 stipulates the following:46

14(3) Transparent means

(a) expressed in reasonably plain language

(b) legible

(c) presented clearly, and

(d) readily available to any person likely to be affected by the contract term or notice in question.

It can therefore be concluded that "plain, intelligible language" means that a term(s) in a consumer contract should also be legible, presented clearly and readily available to the consumer.

4 The statutory provision: section 22 of the Act

Before we turn to the analysis of section 22 of the South African Consumer Protection Act, it is unfortunately necessary to quote extensively from the Act to enable the reader to appreciate the magnitude of the plain language provision. Section 22 stipulates the following:

(1) The producer of a notice, document or visual representation that is required, in terms of this Act or any other law, to be produced, provided or displayed to a consumer must produce, provide or display that notice, document or visual representation -

(a) in the form prescribed in terms of this Act or any other legislation, if any, for that notice, document or visual representation; or

(b) in plain language, if no form has been prescribed for that notice, document or visual representation.

(2) For the purposes of this Act, a notice, document or visual representation is in plain language if it is reasonable to conclude that an ordinary consumer of the class of persons for whom the notice, document or visual representation is intended, with average literacy skills and minimal experience as a consumer of the relevant goods or services, could be expected to understand the content, significance and import of the notice, document or visual representation without undue effort, having regard to -

(a) the context, comprehensiveness and consistency of the notice, document or visual representation;

(b) the organisation, form and style of the notice, document or visual representation;

(c) the vocabulary, usage and sentence structure of the notice, document or visual representation; and

(d) the use of any illustrations, examples, headings or other aids to reading and understanding.

(3) The Commission may publish guidelines for methods of assessing whether a notice, document or visual representation satisfies the requirements of subsection (1)(b).

(4) Guidelines published in terms of subsection (3) may be published for public comment.

In the following paragraphs we will address the following aspects: the structure and purpose of section 22, which documents must be in plain language, what plain language is, if documents should be drafted in plain language in order to comply with the plain language requirements, and proposed guidelines to determine whether or not a document is written in plain language.

5 Structure and purpose of section 22

Section 22 requires notices, documents or visual representations that are required in terms of the Act or other law to be provided in plain and understandable language as well as in the prescribed form, if any. Section 50 also makes plain language compulsory in all consumer agreements.47

The right to receive information in plain and understandable language48 is embedded under the umbrella right of information and disclosure in the Act.49 In interpreting section 22, effect must be given to certain purposes set out in section 3, several of which are served by the protection of the right to receive information in plain and understandable language.50 These include the purpose of "reducing and ameliorating any disadvantages experienced in accessing any supply of goods or services by consumers whose ability to read and comprehend any advertisement, agreement, mark, instruction, label, warning, notice or other visual representation is limited by reason of low literacy, vision impairment or limited fluency in the language in which the representation is produced, published or presented".51 Section 22 also serves the purpose of "improving consumer awareness and information and encouraging responsible and informed choice and behaviour".52 Enabling consumers to make informed choices means that consumers are able to compare products and the prices they are willing to pay, which makes markets more efficient.53 Disclosure can, for example, drive down prices by allowing consumers to shop around and compare prices. Accessible information in required notices and documents and in consumer agreements is also important for the purpose of "promoting consumer confidence, empowerment and the development of a culture of consumer responsibility".54 The prescription of standardised forms for notices and documents that are required in terms of legislation enhances consumer protection because basic information is to be presented in a uniform format, making it less likely that consumers will be misled.55

The plain language requirement therefore seeks to advance procedural fairness.56 In the context of consumer contracting, procedural fairness refers to fairness in the actual process of contracting itself, as opposed to fairness in the substance of the agreement.57 The purpose of measures aimed at procedural fairness is to enable consumers to look after their own interests when dealing with suppliers.58 One important aspect of procedural fairness is transparency.59 Several issues form part of transparency, such as the prominence given to certain terms, the size of the print, the language and structure of the contract, and giving the consumer an adequate opportunity for reflection.60 Plain language is vital to transparency and therefore also to procedural fairness. Thus, many countries have adopted plain language legislation which requires consumer agreements to be in plain language.61

6 Which documents must be in plain language?

Section 22(1) provides that any notice, document or visual representation that is required in terms of the Consumer Protection Act or any other law should be in the form prescribed by the Act.62 If no form is prescribed, it must be in plain language.63 Therefore, this section only applies to notices required by legislation, visual representations and written agreements, and not to oral agreements.64 Section 50 deals with written consumer agreements. It states that the Minister may prescribe categories of agreements required to be in writing.65 It further states that even where an agreement between a supplier and a consumer has been put in writing voluntarily, it must satisfy the plain language requirement and the supplier must then provide a copy of the agreement to the consumer.66

7 What is plain language in terms of section 22?

According to section 22(2), plain language is language that enables an ordinary consumer (of the class of persons for whom a notice, document or visual representation is intended), with average literacy skills and minimal experience as a consumer of the relevant goods or services, to understand the content, significance and import of a document, notice or visual representation, without undue effort.67

When determining if a document or representation is in plain and understandable language, the following aspects must be taken into account:68

(a) the context, comprehensiveness and consistency of the notice, document or visual representation;69

(b) the organisation, form and style of the notice, document or visual representation;70

(c) the vocabulary, usage and sentence structure of the notice, document or visual representation;71 and

(d) aids used to assist the consumer in the reading and understanding of the notice, document or visual representation.72

Gordon and Burt analysed the definition of plain language in section 22 and they state that the definition has been lauded internationally, since it involves the grammar and wording as well as the structure, content, design and style of the document.73 However, it is a very broad definition as it does not give much direction to drafters as to what is specifically required of them.74

The use of the phrase "an ordinary consumer" indicates that not only lawyers and judges should be able to understand a document sent to consumers.75 "For whom a notice, document or visual representation is intended" indicates that suppliers will have to draft more than one set of standard contracts for a specific situation in order to cater for the consumers for whom it is intended, so they must know their "target audience" in advance. It is also advisable to test the proposed wording of the document on a part of the target audience.

The phrase "average literacy skills" implies that documents must cater for average South African consumers of the class for whom the notice, document or representation is intended. A total of approximately eleven percent of adult South Africans are illiterate, so only 89 percent is at least functionally literate; that is, they have at least some basic reading and writing skills.76 However, that does not equip South African consumers to understand business and legal documents.77

"Minimal experience as a consumer of the relevant goods or services" indicates that drafters should write for first-time consumers of the particular goods or services.78 In other words, drafters should focus on the consumer with the least experience and not just the average consumer.79

"Content, significance and import" indicates that consumers must not only understand what the document says, but also how it applies to them, its significance and effect.80 Put differently, the consumer must at least clearly understand the legal consequences of a document or terms, and its express and implied meaning.

"Without undue effort" indicates that if consumers need to consult an advisor or dictionary to understand the terms of a document it would be concluded that their understanding cost them undue effort and that such a document was not in plain language.81

"Context" indicates that it is necessary to take account of how and when consumers read a document or how the document is used.82 What the consumer could reasonably be expected to know from previous transactions could therefore be taken into account. Gordon and Burt use the example of a DVD: with a DVD rental contract it would be reasonable to expect consumers to know what a DVD is, as it is unlikely that they would be in this context if they did not.83

"Comprehensiveness" indicates that the document must give full information.84 "Comprehensiveness" further indicates that it is not only necessary to take account of how a document is written, but also of what is written. The contents of a document should therefore be considered and should enable a consumer to make an informed choice.

"Consistency" indicates that the terminology and style must be consistent throughout a document.85 "Consistency" therefore indicates that it necessary to take account of how a document is written. Factors such as the consistent use of terminology, headings, and sentence structure are examples of what should be considered.

"Organisation, form and style" refers to how a document is structured. For example, no hidden small print should be used and important information should be given at the top of a document or important sections should be highlighted in text boxes.86

"Vocabulary, usage and sentence structure" refers to general principles of readability, such as using short sentences, the active voice, personal pronouns and short words, and avoiding technical jargon.87

"Illustrations, examples, headings or other aids to reading and understanding" refers to devices to make a document more inviting and to good techniques for communicating complex information.88

8 Official languages

Unlike section 63 of the National Credit Act,89 the Consumer Protection Act does not require information to be provided in more than one of the official languages.90

Under the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, South Africa has 11 languages.91 The state has a constitutional duty to take positive and practical measures to elevate and advance the use of languages that historically have had diminished status.92 All official languages must enjoy parity of esteem and be treated equitably.93

An official language requirement would have placed an enormous burden on suppliers in South Africa. One can, for example, imagine what the financial impact would have been if all suppliers were required to translate information and documents into all eleven official languages. However, it is uncertain what the position will be in respect of South Africans who do not speak English (sometimes regarded as the lingua francaof the country and also the language commonly used in agreements) and of foreigners in South Africa (who speak only a foreign language).94 How could the requirements of plain language ever be complied with if consumers do not understand the language used in agreements or other communications? Such consumers presumably have to consult an advisor or dictionary and it would be considered that their understanding cost them undue effort and that the document was not in plain language. However, a foreigner would probably not be regarded as an "ordinary consumer of the class of persons for whom the notice, document or visual representation is intended", and accordingly the requirements of plain language would not require the document to be made available in a foreign language.95

Furthermore, section 40(2) provides that it is unconscionable for a supplier to knowingly take advantage of the fact that a consumer is substantially unable to protect his or her own interests because of an inability to understand the language of an agreement. If the supplier realises that a consumer is unable to understand the language of the agreement, the agreement may be subject to challenge on the basis of section 40.

The draft of the Consumer Protection Bill contained a section on the right to information in an official language.96 However, it was omitted from the final Bill after certain industry stakeholders made submissions that the requirement for the provision of information in all official languages would have been too onerous.97

On the one hand, in the light of this omission, one can conclude that a notice, document or visual representation does not need to be written in an official language in order for it to be in plain language. On the other hand, plain language is language that enables an ordinary consumer of the class of persons for whom a notice, document or visual representation is intended to understand it. When a drafter considers the class of persons for whom a notice, document or visual representation is intended, language should certainly be taken into account. It will, therefore, be to a supplier's advantage to translate documents, notice or visual representations into the official languages spoken by the class of persons for whom they are intended.

9 Guidelines that may be published or taken into account

The three most common plain-language standards or assessment measures that may be applied to assess if agreements comply with plain language requirements are:

(a) informal assessment;

(b) formal assessment; and

(c) using assessment software.98

Informal assessment guidelines include in-house style guides and any other in-house assessment measures.99 Informal assessment would be difficult to regulate, but is a valuable in-house assessment tool for plain language. A formal and objective style guide gives more substance to general provisions and is a valuable test mechanism or guideline that a legislator or a regulator may use to give concrete guidance to drafters.

The Consumer Protection Act provides that the National Consumer Commission (NCC) may publish guidelines on methods of assessing plain language.100 No such objective guidelines have been published yet. In the absence of guidelines, it will be difficult to tell whether suppliers meet the requirements of plain language or not. In order to proactively give effect to the requirement of the use of plain language, to improve levels of disclosure and to increase procedural fairness, objective assessment mechanisms or guidelines must be put in place.

It is a concern that the definition of plain language is too flexible and is subject to discretion and interpretation.101 Guidelines on methods of assessing plain language might solve these concerns and would help in testing compliance with the plain language provisions and in preventing non-compliance.

The NCC may consider examples of style guides on plain language in foreign legislation, when drafting the proposed guidelines for South Africa. In any event, such foreign legislation may be relevant to the interpretation of the plain language standard in section 22. Section 2(2) provides that "[w]hen interpreting or applying this Act, a person, court or Tribunal or the Commission may consider appropriate foreign and international law .".

Very good examples of formal, general and visual style guides that have been adopted by legislators can be found in the law of the states of Pennsylvania102 and Connecticut103 in the United States of America.104 The legislator of Pennsylvania prescribed a broad and general standard for plain language. In s 2205(b)-(d) of the Pennsylvania Plain Language Consumer Contract Act, guidelines are listed to determine whether the general standard has been met. The guidelines that should be applied in order to determine if a document meets the plain language requirement are:

(a) the contract should use short words, paragraphs and sentences and active verbs

(b) it should not use technical legal terms other than commonly understood legal terms;

(c) Latin and foreign words may not be used;

(d) if the document defines words, they must be defined by using commonly understood meanings;

(e) sentences may not contain more than one condition;

(f) and cross-references may not be used, except cross-references that briefly and clearly describe the substance of the item to which reference is made.

Section 2205(c) contains visual guidelines which a court must consider in determining whether or not a contract meets these requirements. These guidelines require, for instance, that the contracts should have type size, line length, column-width margins and spacing between lines and paragraphs that make the contract easy to read, that the contract should have caption sections typed in bold, and that the contract should use ink that contrasts sharply with the paper. If a creditor, lessor or seller does not comply with the plain language requirements of the Pennsylvania Plain Language Consumer Contract Act,105 he or she will be liable to that consumer for the following: compensation in an amount equal to the value of the actual loss caused by the violation of the Act; statutory damage of US$100 (or less if the total amount of the contract is less than US$100); court costs; reasonable attorney fees; any equitable and other relief ordered by the court.106

Very similar guidelines to those that apply in Pennsylvania are used in Connecticut, but a more objective approach may also be followed.107 An objective test is specific in its specification because it stipulates specific numbers and sizes to which words, sentences and syllables should adhere.108 The Connecticut statute provides that a consumer contract is written in plain language if it fully meets the requirements of the alternative objective test. The objective test requires the following:

(a) the average number of words per sentence must be fewer than 22;

(b) no sentence in the contract may exceed 50 words;

(c) the average number of words per paragraph must be fewer than 75;

(d) no paragraph in the contract may exceed 150 words;

(e) the average number of syllables per word must be fewer than 1.55;

(f) the contract must use personal pronouns, the actual or shortened names of the parties to the contract, or both, when referring to those parties;

(g) no typeface of less than eight points in size may be used;

(h) at least three sixteenths of an inch of blank space must be allowed between each paragraph and section;

(i) at least half an inch of blank space must be allowed at all borders of each page;

(j) if the contract is printed, each section must be captioned in boldface type at least 10 points in size. If the contract is typewritten, each section must be captioned and the captions underlined; and

(h) the average line length in the contract must be no more than 65 characters.

The advantage of this alternative approach is that it can be applied easily and computers can be used to do the required calculations.

There are software programmes that use well-known readability tests to test whether or not a document is written in plain and understandable language. Readability formulas are mathematical equations that predict the level of reading ability needed to understand a specific document. They are based on correlations with some measure of comprehension, such as scores on a reading test. Therefore, these formulas predict readability rather than measuring it. Another drawback is that they do not address the causes of problems people might have in understanding a document, which makes it difficult to deal with such problems proactively. For example, legal language is hard to understand and it is difficult to make it more intelligible.109 Readability formulas therefore have limited use, because they are not accurate in the context of law, nor are they proactive.110 Furthermore, they are not specifically adapted in order to test compliance with the plain language requirements of different sets of legislation. The Flesch reading ease test111 is probably the most common readability test that is used in software packages such as Microsoft Office and it is sometimes incorporated into legislation through the requirement of a minimum score.112 Basically, the test scores the readability of documents in such a way that a score of 100 would mean that it was simple and a score of 0 would mean that it was very difficult to read. The average number of words in every sentence and the average number of syllables per word are taken into account.113 A document with a very good score would therefore contain shorter words and sentences. The Flesch reading ease test can be criticised from a legal perspective. The point of criticism is that legal language is hard to understand and that it cannot be improved by using only shorter words and sentences.114 This means that a document could pass the Flesch reading ease test without being written in plain language. Readability tests such as this were not developed for technical documents, because they ignore content, layout, organisation, word order, visual aids and the intended audience, and emphasise countable features of the document rather than the comprehensibility of the text.115 Readability formulas assume that all consumers are alike, while the Consumer Protection Actrequires that an ordinary consumer of the class of persons for whom the notice, document or representation is intended, with average literacy skills and minimal experience as a consumer, must be able to understand the contents without undue effort.116 So, in the South African consumer context, general text-based readability tests cannot be applied in order to test compliance with the plain and understandable language requirements.

10 Consequences of non-compliance

10.1 Validity

The effect of a term or agreement not being in plain and understandable language is not clear. Section 51(1)(a)(i) states that a supplier may not enter into a transaction or agreement subject to a term or condition if its general purposes is to defeat the policy of the Act. Section 3(1)(b)(iv) of the Consumer Protection Act states that it is the purpose of the Act to promote and advance the social and economic welfare of consumers by:

reducing and ameliorating any disadvantages experienced in accession any supply of goods or services by consumers whose ability to read and comprehend any advertisement, agreement, mark, instruction, label, warning, notice or other visual representation is limited by reason of low literacy, vision impairment or limited fluency in the language in which the representation is produced, published or presented.

Furthermore, section 51(1)(b)(i)-(iii) states that a supplier may not enter into a transaction or agreement subject to a term or condition if it directly or indirectly purports to waive or deprive a consumer of a right in terms of the Act or avoid a supplier's obligation or duty in terms of the Act or override the effect of any provision of the Act. Section 50(2)(b)(i) requires agreements to be written in plain and understandable language. Section 51(3) provides that a transaction or agreement, provision, term or condition of a transaction or agreement is void to the extent that it contravenes section 51. Therefore, one may argue that if an agreement is not written in plain and understandable language as required in terms of section 50(2)(b)(i), the agreement, provision, term or condition of the agreement will be void in terms of section 51(3).117 If an agreement, term or condition of an agreement is void, the court may sever any part of the agreement or provision or alter it to the extent required to render it lawful or declare the entire agreement or provision void as from the date it purportedly took effect.118 The court may also make any further order that is just and reasonable in the circumstances with respect to the agreement.119 On the other hand, one may argue that whether or not an agreement is in plain and understandable language is merely a factor in deciding whether a term or agreement is unfair under section 48. Whether a term is in plain language or not is merely listed as a factor in section 52.120 Therefore non-compliance with the plain language requirements will not necessarily render a term or agreement void.121

10.2 Prohibited conduct and compliance notices

In terms of section 71(1) any person may file a complaint with the National Consumer Commission,122 alleging that a person has acted in a manner inconsistent with the Act. After concluding an investigation into a complaint pertaining to the plain language requirements, the National Consumer Commission may if it believes that a person has engaged in prohibited conduct, issue a compliance notice in terms of section 100.123 The compliance notice must, among other things, set out the details and nature and extent of the non-compliance with the plain language requirements, any steps that are required to be taken, and the period within which such steps must be taken. The compliance notice must also set out any penalty that may be imposed in terms of the Act it those steps are not taken.124 Section 100 further provides that if a person to whom a compliance notice has been issued fails to comply with the notice, the National Consumer Commission may apply to the Tribunal for the imposition of an administrative fine125 or refer the matter to the National Prosecuting Authority in terms of section 110(2).126 Section 110(2) provides that it is an offence not to act in accordance with a compliance notice.127 However, no person may be prosecuted in respect of non-compliance with a compliance notice if the National Consumer Commission has applied to the Tribunal for the imposition of an administrative fine.

Plain language is not directly addressed in section 40(2). Section 40(2), however, provides that it is unconscionable for a supplier to knowingly take advantage of the fact that a consumer was substantially unable to protect his or her own interests because of an inability to understand the language of an agreement. If a consumer alleges that a supplier acted unconscionably,128 made false, misleading or deceptive representations129 or that a contract term or terms are unfair, unreasonable or unjust,130 the court must consider several factors to ensure fair and just conduct, terms and conditions.131 One of these factors in deciding if a term or agreement is unfair under section 48 is the extent to which any documents relating to the transaction or agreement satisfy the plain language requirement.132 Non-compliance with the plain language requirements may therefore contribute towards a finding of unfairness in terms of section 52 of the Act.

11 Conclusion

The Consumer Protection Act has made the use of plain and understandable language compulsory in contracts and documents intended for consumers. It contains a detailed definition of plain and understandable language, which contains elements pertaining to grammar, text, visual aspects, and illustrations. All the elements of this definition have been analysed in this article. The Act also makes provision for the publication of guidelines on assessing whether a document is in plain and understandable language or not. No guidelines have been published yet. Guidelines based on foreign legislation are therefore proposed in this article.

The importance and role of plain language in consumer contracts have also been accentuated. Great effort is being made in countries such as South Africa, Australia, the United Kingdom, Malta, and certain states in the United States of America to draw up consumer contracts in the simplest language possible, without "fancy tricks", so that an average consumer can understand such a contract. This is because a consumer has a right to empathise and understand the contract he or she signs. One can say that a consumer is entitled to "simple language" and "transparent" contracts where the rights and duties of all parties are clearly specified. The most important goal of plain language rights is to empower consumers to understand the contracts they sign and to make informed decisions. It would therefore serve no purpose to allow clearly deceptive and misleading clauses in consumer contracts, even if they are embedded in simple, straightforward words and phrases.133

It must be emphasised that plain language has substantial benefits and advantages for consumers as well as for businesses. Of course the exact value of these benefits and advantages cannot be determined, but there are enough compelling reasons to believe that these benefits and advantages outweigh the costs.134 Most importantly, using plain language increases transparency, openness and the extent of disclosure, and contributes to higher levels of procedural fairness. It may also save money and time by reducing the amount of unnecessary litigation.

To conclude, the use of plain and understandable language in consumer contracts results in transparency and clear and effective communication - nothing more or less.135 It is therefore essential that the following should be kept in mind when it comes to consumer contracts and consumer rights:136

So long as consumers' rights are not transparent, they will not be accessible by consumers. In turn, having rights that are not accessible can be tantamount to not having any rights at all. Therefore, for consumer empowerment, not only should consumers have the necessary rights, but they should also be aware of these rights and be able to access these rights when they need to.

Bibliography

Aitchison J and Harley A "South African Illiteracy Statistics and the Case of the Magically Growing Number of Literacy and ABET Learners" 2006 Journal of Education 89-112 [ Links ]

Alberts M "Plain Language in a Multilingual Society" in Viljoen F and Nienaber A (eds) Plain Language for a New Democracy (Protea Bookhouse Pretoria 2001) 89-118 [ Links ]

Asprey MM Plain Language for Lawyers (Federation Press Leichhardt 2003) [ Links ]

Black B "A model plain language law" 1981 Stan L Rev 255-300 [ Links ]

Cheek A "Defining plain language" 2010 Clarity: Journal of the International Association Promoting Plain Legal Language 5-15 [ Links ]

Christie RH and McFarlane V The Law of Contract in South Africa 5th ed (LexisNexis Butteworths Durban 2005) [ Links ]

Du Preez ML "The Consumer Protection Bill: A Few Preliminary Comments" 2009 TSAR 58-83 [ Links ]

Flesch R "A New Readability Yardstick" 1948 Journal of Applied Psychology 221-233 [ Links ]

Gordon F and Burt C "Plain Language" 2010 Without Prejudice 10.4 59-60 [ Links ]

Gorones SG The Australian Consumer Law (Thomson Reuters Sydney 2011) [ Links ]

Gouws MM "A Consumer's Right to Disclosure and Information: Comments on the Plain Language Provisions of the Consumer Protection Act" 2010 SA Merc LJ 79-94 [ Links ]

Kimble J "Answering the critics of plain language" 1994-1995 Scribes J Legal Writing 51-85 [ Links ]

Klare GR "Assessing Readability" 1974 Reading Research Quarterly 62-102 [ Links ]

Lawson R Exclusion Clauses and Unfair Contract Terms 8th ed (Sweet & Maxwell London 2005) [ Links ]

Louw E The Plain Language Movement and Legal Reform in the South African Law of Contract (LLM-thesis UJ 2010) [ Links ]

Meiring I "Consequences of non-compliance with the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008" 2010 Without Prejudice 10.11 28-29 [ Links ]

Melville N The Consumer Protection Act Made Easy (Book of Life Publications Pretoria 2010) [ Links ]

Micklethwait D Noah Webster and the American Dictionary (Mcfarland Jefferson, NC 2000) [ Links ]

Naudé T "Unfair contract terms legislation: the Implications of why we need it for its formulation and application" 2006 Stel LR 361-385 [ Links ]

Naudé T "The Consumer's Right to 'Fair, Reasonable and Just Terms' under the New Consumer Protection Act in Comparative Perspective" 2009 SALJ 505-536 [ Links ]

Nebbia P Unfair Contract Terms in European Law (Hart Oxford 2007) [ Links ]

Newman P "The influence of plain language and structure on the readability of contracts" 2010 Obiter 735-745 [ Links ]

Paterson J "The Australian Unfair Contract Terms Law: the Rise of Substantive Unfairness as a Ground for Review of Standard Form Consumer Contracts" 2003 MULR 934-956 [ Links ]

Petelin R "Considering plain language: Issues and initiatives" 2010 Corporate Communications: An International Journal 205-216 [ Links ]

Redish J "Readability Formulas have even More Limitations than Klare Discusses" 2000 ACM Journal of Computer Documentation 132-137 [ Links ]

Rinkes JGJ "European Consumer Law: Making Sense" 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law 3-18 [ Links ]

Sibiya HS A Strategy for Alleviating Illiteracy in South Africa: A Historical Inquiry (PhD-thesis UP 2004) [ Links ]

Stoop PN "Plain language and assessment of plain language" 2011 Int J Private Law 329-341 [ Links ]

Tiersma P Legal Language (University of Chicago Press Chicago 1999) [ Links ]

Viljoen F "The Plain Language Experience in the USA" in Viljoen F and Nienaber A (eds) Plain Language for a New Democracy (Protea Bookhouse Pretoria 2001) 45-51 [ Links ]

Willet C Fairness in Consumer Contracts: The Case of Unfair Terms (Ashgate Aldershot 2007) [ Links ]

Willet C "General Clauses on Fairness and the Promotion of Values Important in Services of General Interest" 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law 67-106 [ Links ]

Register of legislation

Australia

Competition and Consumer Act, 2010

Trade Practices Act, 1974

Malta

Maltese Consumer Affairs Act, 1994

South Africa

Companies Act 71 of 2008

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008

Consumer Protection Regulations,

2008 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972

National Credit Act 34 of 2005

United Kingdom

Enterprise Act, 2002

European Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993

Unfair Contract Terms Act, 1977

Unfair Contract Terms Bill, 2005

Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations, 1999

United States of America

Connecticut General Statute, 2009 (Conn Gen Stat s 42-152 (2009))

Florida Readable Language in Insurance Policies Law (Florida Stats Ann s 627.4145)

Pennsylvania Plain Language Consumer Contract Act (Pa Stat Ann Tit 73 (1997))

Register of case law

Australia

Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v AAPT 2006 VCAT 1493

Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc 2008 EWHC 875

South Africa

Bank of Lisbon and South Africa v De Orne/as 1988 3 SA 580 (A)

Magna Aloys and Research (SA) Pty Ltd v Eliis 1984 4 SA 874 (A)

National Chemsearch (SA) (Pty) Ltd v Borrowman 1979 3 SA 1092 (T)

Standard Bank of South Africa Ltd v Dlamini 2012 ZAKZDHC 64

Register of government publications

Gen N 1957 in GG 26774 of 9 September 2004 (Draft Green Paper on the Consumer Policy Framework)

Gen N 418 in GG 28629 of 15 March 2006 (Consumer Protection Bill, 2006 (Second Discussion Draft))

Register of internet sources

Australian Consumer Law 2010 The Australian Consumer Law: A Guide to Provisions www.consumerlaw.gov.au/content/the_acl/downloads/ACL_guide_ to_provisions_November_2010.pdf [date of use 23 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Australian Consumer Law 2010 A Guide to the Unfair Contract Terms Law www.consumerlaw.gov.au/content/the_acl/downloads/unfair_contract_terms_ guide.pdf [date of use 23 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Business Unity South Africa 2006 Consumer Protection Bill: Submissions by Business Unity South Africa www.busa.org.za/docs/Final%20BUSA% 20Submissions%20%20Consumer%20Protection%20Bill.pdf [date of use 5 Jan 2013] [ Links ]

Commonwealth of Australia 2010 A Guide to the Unfair Contract Terms Law www.consumerlaw.gov.au/content/the.../unfair_contract_terms_guide.rtf [date of use 7 Aug 2013] [ Links ]

Commonwealth of Australia 2010 A Guide to the Unfair Contract Terms Law www.consumer.vic.gov.au/library/publications/businesses/fair-trading/guide-to-unfair-contract-terms-law-word.rtf [date of use 19 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Department for Business Innovation and Skills 2012 Enhancing Consumer Confidence by Clarifying Consumer Law www.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31864/12-937-enhancing-consumer-consultation-supply-of-goods-services-digital.pdf [date of use 30 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Kirby N 2011 Clearly Clear? Plain and Understandable Language in terms of the Consumer Protection Act www.mondaq.com/x/144478/Consumer+Law/ Clearly+Clear+Plain+And+Understandable+Language+In+Terms+Of+The+C onsumer+Protection+Act [date of use 7 Aug 2013] [ Links ]

Mazur B 2000 Revisiting Plain Language www.plainlanguage.gov/ whatisPL/History/mazur.cfm [date of use 7 Aug 2013] [ Links ]

Micallef PE 2007 Unfair Terms in Contracts - The Maltese Perspective www.iaclaw.org/Research_papers/unfairterms.pdf [date of use 30 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Scottish Law Commission 2012 Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts: A New Approach? Issues Paper" lawcommission.justice.gov.uk/docs/unfair_terms_in_consumer_contracts_issues.pdf [date of use 18 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Skinner D 2002 Clarity www.textfixarna.se/wp-content/uploads/ 2013/01/plain_english.pdf [date of use 22 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

Sundin M 2002 Plain English and Swedish larsprêk www.textfixarna.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/plain_english.pdf [date of use 22 Apr 2013] [ Links ]

World Bank 2012 South Africa data.worldbank.org/country/south-africa [date of use 23 Jul 2012] [ Links ]

List of abbreviations

ACL Australian Consumer Law

BUSA Business Unity South Africa

DTI Department of Trade and Industry

Int J Private Law International Journal of Private Law

MULR Melbourne University Law Review

NCC National Consumer Commission

SALJ South African Law Journal

SA Merc LJ South African Mercantile Law Journal

Scribes J Legal Writing The Scribes Journal of Legal Writing

Stan L Rev Stanford Law Review

Stell LR Stellenbosch Law Review

TSAR Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg

UCTA Unfair Contract Terms Act

UTCCR Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations

1 Skinner 1998 www.textfixarna.se.

2 Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

3 Kirby 2011 www.mondaq.com.

4 However, when it is alleged that a contract in restraint of trade is unreasonable, reasonableness (the context), is assessed at the time of enforcement. See, for example, Magna Alloys and Research (SA) Pty Ltd v Ellis 1984 4 SA 874 (A); National Chiemsearchi (SA) (Pty) Ltd v Borrowman 1979 3 SA 1092 (T) 1107. Before the decision in Bank of Lisbon and South Africa v De Ornelas 1988 3 SA 580 (A) it had also been accepted that the exceptio doligeneralis provided a remedy against the enforcement of an unfair contract in unfair circumstances but the then Appellate Division reviewed the authorities on the exceptio doli generalis and concluded that it is not part of South African law (at 607B). The exceptio doligeneraiis could therefore no longer be used to give relief against the enforcement of an unfair contract.

5 The taking into consideration of context at the formation of a contract or pre-contractually is therefore not foreign to the South African law of contract. See for example the rules on misrepresentation and fraud, duress, undue influence, mistake and illegality, which aim at curbing unfairness at the formation of a contract. In these instances context (at the formation of a contract) plays a role. The question is, however, whether the common-law rules and principles cover the ground sufficiently or whether there are gaps that need to be filled to curb unfairness. See also Christie and McFarlane Law of Contract 14.

6 For a discussion of the goal of consumer protection, see Rinkes 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law 15.

7 Ri nkes 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law 15.

8 See, generally, Lawson Exclusion Causes 219; Naudé 2006 StelLR 377.

9 Willet 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law 75. See also Paterson 2003 MULR 949, where the author analyses elements of transparency: a term is in transparent where it is (a) expressed in reasonably plain language, (b) legible, (c) presented clearly, and (d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

10 See also Nebbia Unfarr Contract Terms 135-136.

11 See also Nebbia Unfair Contract Terms 137.

12 Willet Farrness 55-56.

13 Kimble 1994-1995 Scribes J Legal Wrttnng 53.

14 Petelin 2010 Corporate Communications'207.

15 See para 9 below.

16 Mazur 2000 www.plainlanguage.gov.

17 Paterson 2003 MULR934.

18 See also Gorones Austraiian Consumer Law 35-55.

19 ACL 2010a www.consumerlaw.gov.au.

20 Section 24(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act, 2010.

21 Paterson 2003 MULR 934.

22 Cheek 2010 Caartty 5.

23 Cheek 2010 Caartty 5.

24 ACL 2010b www.consumerlaw.gov.au 12-13.

25 ACL 2010b www.consumerlaw.gov.au 12-13.

26 ACL 2010b www.consumerlaw.gov.au 12-13.

27 ACL 2010b www.consumerlaw.gov.au 12-13.

28 Commonwealth of Australia 2010 www.commonlaw.gov.au 11.

29 See para 3.2 below.

30 Office of Farr Trading v Abbey Nationalp/c 2008 EWHC 875.

31 ACL 2010b www.consumerlaw.gov.au 12-13.

32 Drrector of Consumer Affarrs Victoria v AAPT 2006 VCAT 1493; see also Commonwealth of Australia 2010 www.consumer.vic.gov.au.

33 Micklethwait Noah Webster 34; see also Sundin 2002 www.textfixarna.se.

34 Micklethwait Noah Webster 34; see also Sundin 2002 www.textfixarna.se. It is important to remember that although the spelling of certain words were different at that time (1604), plain language had already become important.

35 Sundin 2002 www.textfixarna.se.

36 Sundin 2002 www.textfixarna.se.

37 See Scottish Law Commission 2012 lawcommission.justice.gov.uk for an overview.

38 Scottish Law Commission 2012 lawcommission.justice.gov.uk.

39 European Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993.

40 European Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993.

41 European Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993.

42 European Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993.

43 See also Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 330.

43 Notably, the Maltese consumer law pertaining to plain and intelligible language in consumer contracts is similar to the UK law. Article 47(1) of the Maltese Consumer Affairs Act, 1994 stipulates that a term(s) in any consumer contract must be "written in plain and intelligible language which can be understood by the consumer to whom the contract is directed". Article 47(2) further states that "if a term is ambivalent or if there is any doubt as to its meaning, then the interpretation most favourable to the consumer shall prevail". See Micallef 2007 www.iaclaw.org.

44 Scottish Law Commission 2012 lawcommission.justice.gov.uk.

45 Scottish Law Commission 2012 lawcommission.justice.gov.uk.

46 See, in general, Willet 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law79.

47 The National Credit Act 34 of 2005 was the first South African piece of legislation that required agreements to be drafted in plain language (s 64). The Companies Act 71 of 2008 in subsections 6(4) and (5) has a definition of plain language with regard to the drafting of a prospectus, notice, disclosure or other document that does not have a prescribed form. The definition is similar to the definition of plain language in the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

48 Section 22 does not merely require the use of plain and understandable language; the plain language requirement is elevated to a fundamental consumer right (see the heading of s 22 where the word 'right' is used). See also Gouws 2010 SA Merc LJ85.

49 Chapter 2, Part D of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

50 Section 2(1) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

51 Section 3(1)(b)(iv) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008. See also Gen N 1957 in GG 26774 of 9 September 2004 (Draft Green Paper on the Consumer Policy Framework) 31.

52 Section 3(1)(e) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

53 Gen N 1957 in GG 26774 of 9 September 2004 (Draft Green Paper on the Consumer Poiicy Framework) 28.

54 Section 3(1)(f) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

55 Gen N 1957 in GG 26774 of 9 September 2004 (Draft Green Paper on the Consumer Poiicy Framework) 28.

56 See also para 2 above.

57 See, generally, Lawson Exclusion Causes 219; Naudé 2006 StelLR 377.

58 Willet 2008 Yearbook of Consumer Law 75.

59 See also Paterson 2003 MULR 949, where the author analyses elements of transparency: a term is transparent where it is (a) expressed in reasonably plain language, (b) legible, (c) presented clearly, and (d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

60 Willett Fairness 321-375.

61 See para 2 above. See also Gouws 2010 SA Merc LJ80.

62 Section 22(1)(a). The Consumer Protection Act requires certain information to be made available to consumers, and the required notices, provisions or agreements should be written in plain and understandable language: see s 24 read with Consumer Protection Regulations, 2008 regs 6-7 (prescribed product labelling and trade descriptions; in this regard see also s 15 of the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972); s 25 read with reg 8 (notice disclosing reconditioned or grey market goods); s 27 read with reg 9 (notice disclosing prescribed information in respect of intermediaries); s 37 read with reg 12 (cautionary statement disclosing prescribed information in respect of alternative work schemes); s 49 (notice required for certain terms and conditions); s 50(1) (categories of agreements required to be in writing).

63 Section 22(1)(b) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

64 Du Preez 2009 TSAR 75-76.

65 Du Preez 2009 TSAR75-76.

66 Section 50(2)(a)-(b) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008. Contra Gouws 2010 SA Merc LJ 86, where it is stated that "[a]lthough signature of an agreement signifies the parties' assent to it, subs(2)(a) is an exception with a view to protecting the consumer, and not the supplier. However, to avoid creating a 'ticket case' and because the Act contemplates an agreement signed by both the consumer and the supplier, an agreement that is not signed by the supplier has to be signed by the consumer for s 22 to apply".

67 Section 64 of the National Credit Act 34 of 2005 and s 22 of the Consumer Protection Act68 of 2008 have identical plain language requirements. In Standard Bank of South Africa Ltd v Dlamini 2012 ZAKZDHC 64, a case which dealt, among other things, with the plain language requirements of the National Credit Act the court concluded (at para [48]-[50]) that strictly interpreted neither s 63 nor s 64 of the National Credit Act assists an illiterate. However, purposively interpreted they (the plain language and official language provisions of the National Credit Act) embody the right of the consumer to be informed by reasonable means of the material terms of the documents he signs. Furthermore, the supplier bears the onus to prove that it took reasonable measures to inform the consumer of the material terms of the agreement.

68 See Gouws 2010 SA Merc LJ 89, where he states that the features listed in s 22(2)(a)-(d) are merely guidelines and that non-compliance with them will not without more ado render the agreement not plain. For further discussion, see also Newman 2010 Obiter 735.

69 Section 22(2)(a) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

70 Section 22(2)(b) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

71 Section 22(2)(b) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

72 Section 22(2)(c) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

73 Gordon and Burt 2010 Without Prejudice 59-60. See also Melville Consumer Protection Act 157-170.

74 Louw Plain Language 137.

75 Gordon and Burt 2010 Without Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333; Melville Consumer Protection Act 161.

76 World Bank 2012 web.worldbank.org. See also Aitchision and Hartley 2006 Journal of Education 93-94; Sibiya Al/evaating Illiteracy 1. See also Melville Consumer Protection Act 161.

77 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333.

78 Gordon and Burt 2010 Without Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333.

79 Melville Consumer Protection Act 162.

80 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333.

81 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333, Gouws 2010 SA Merc LJ 88-89; Melville Consumer Protection Act162.

82 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333.

83 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Melville Consumer Protection Act 163.

84 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333; Melville Consumer Protection Act 163.

85 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333; Melville Consumer Protection Act 163.

86 Gordon and Burt 2010 Wtthout Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333-334; Melville Consumer Protection Act 163.

87 Gordon and Burt 2010 Without Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 334; Melville Consumer Protection Act 163; Newman 2010 Obiter 741-745.

88 Gordon and Burt 2010 Without Prejudice 59-60; Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 334; Melville Consumer Protection Act (2010) 163.

89 See also para 7 above.

90 In terms of s 63 of the National Credtt Act34 of 2005 every consumer has a right to receive any document that is required in terms of the National Credtt Actin an official language that he reads or understands to the extent that this is reasonable, bearing in mind usage, practicality, expense, regional circumstances and the balance of the needs and preferences of the population ordinarily served by the person required to deliver that document. The Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 does not contain a similar provision. One can therefore conclude that the Consumer Protection Act does not furnish a consumer with a right to receive any document that is required in terms of the Consumer Protection Actin a particular official language.

91 Section 6 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

92 Section 6(2) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

93 Section 6(4) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.See also Alberts "Plain Language" 89-118.

94 See the discussion in Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 334.

95 Section 22(2) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

96 Section 33 of the Consumer Protection Bill, 2006 (Second Discussion Draft) published in Gen N 418 in GG 28629 of 15 March 2006.

97 See eg, the submissions made by Business Unity South Africa in BUSA 2006 www.busa.org.za.

98 Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 335.

99 Asprey Paann Language 295-297.

100 See ss 92-98 for a discussion on the functions of the National Consumer Commission. See also Gouws 2010 SA Merc LLJ86-90 where he states that an agreement would be in plain language if the language used was semantically clear and coherent and contained at least some of the features listed in the Act, resulting in the agreement being legible.

101 Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 333.

102 Pennsylvania Plain Language Consumer Contract Act (Pa Stat Ann Tit. 73 (1997)). S 2205(a) requires that "all consumer contracts ... shall be written, organized and designed so that they are easy to read and understand". See also the discussion in Tiersma Legal Language 224-225, Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 336 and Louw Plain Language 140-141.

103 Connecticut General Statutes, 2009 (Conn Gen Stat s 42-152 (1999)). S 152(a) requires that all consumer contracts "shall be written in plain language". See also Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 336-337 and Louw Plain Language 139-140.

104 See also Viljoen "Plain Language Experience" 45-51.

105 Section 2205 of the Pennsylvania Plain Language Consumer Contract Act (Pa Stat Ann Tit. 73 (1997)).

106 Section 2207 of the Pennsylvania Plain Language Consumer Contract Act (Pa Stat Ann Tit. 73 (1997)).

107 Connecticut General Statutes, 2009 (Conn Gen Stat s 42-152 (1999)) ss 42-152. See Tiersma Legal Language 225 and Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 336-337.

108 See also Louw Plain Language 140.

109 Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 337-338. See also Redish 2000 ACM Journal of Computer Documentation 132; Klare 1974 Reading Research Quarterly 62.

110 See Asprey Plain Language 299.

111 The Flesch reading ease test was proposed in Flesch 1948 Journal of Applied Psychology 221.

112 See eg Florida's requirements on readable language in insurance policies, where a minimum score of 45 on the Flesch reading ease test is required (Florida Readable Language in Insurance Policies Law s 627.4145). See also Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 338. See also Tiersma Legal Language 226; Klare 1974 Reading Research Quarterly 62-102 for an analysis of readability formulas.

113 Stoop 2011 IntJPrivate Law338; Tiersma LegalLanguageat 226.

114 Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 338; Tiersma Legal Languageat 227.

115 Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 338; Redish 2000 ACM Journal of Computer Documentation 132137.

116 Stoop 2011 Int J Private Law 338.

117 See also Gouws 2010 SA Merc LJ90-91.

118 Section 52(4)(a) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008. See also Gouws 2010 SA Merc LLJ 90-91.

119 Section 52(4)(b) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008. See also Gouws 2010 SA Merc LLJ 90-91.

120 Section 52(2)(g) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

121 See also Naudé 2009 SALJ513.

122 See s 99 of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 where the enforcement functions of the Consumer Commission are set out.

123 Section 73(1)(c)(iv) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

124 Section 100(3) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

125 See s 112 of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 in respect of administrative fines. If the National Consumer Tribunal imposes an administrative fine in respect of prohibited or required conduct, the fine may not exceed the greater of 10% of the respondent' annual turnover during the preceding financial year or R1 million.

126 Section 100(6) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

127 See s 111 of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 for the penalties in respect of an offence in terms of the Act. A person convicted of an offence may be liable for a fine or imprisonment for a period not exceeding 12 months, or both a fine and imprisonment. See also Meiring 2010 Without Prejudice 29.

128 Section 40 of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

129 Section 41 of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

130 Section 48 of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

131 Section 52(1) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

132 Section 52(2)(g) of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

133 See, in general, Black 1981 Stan L Rev259-260.

134 Black 1981 Stan L Rev 259-260.

135 Kimble 1994-1995 Scribes J Legal Wrttnng 52.

136 Department for Business Innovation and Skills 2012 www.gov.uk 16.