Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.16 n.4 Potchefstroom Apr. 2013

ARTICLES

Constitutional Court 1995 - 2012: How did the cases reach the Court, why did the Court refuse to consider some of them, and how often did the Court invalidate laws and actions?

IM Rautenbach

IBA LLB (UP) LLD (UNISA). Research Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Johannesburg. Email: irautenbach@uj.ac.za

SUMMARY

The purpose of this article is to contribute data for the purposes of debates on how effectively the Constitutional Court performed its functions between 1995 and 2012. The cut-off date of 31 December 2012 has no other significance than that it was the last date before the beginning of the year in which this article was written. However, it is envisaged that the Constitution Seventeenth Amendment Act of 2012, which expressly provides that the Constitutional Court will after its commencement have jurisdiction to hear applications on non-constitutional matters. The figures contained in this article could at a later stage be used to determine what effect this amendment might have had on the functioning of the Court. it is envisaged that the Constitution Seventeenth Amendment Act of 2012, which expressly provides that the Constitutional Court will after its commencement have jurisdiction to hear applications on non-constitutional matters, will commence in the course of the second half of 2013. The figures contained in this article could at a later stage also be used to determine what effect this amendment might have had on the functioning of the Court.

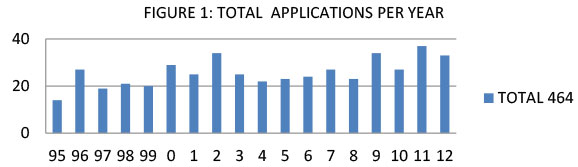

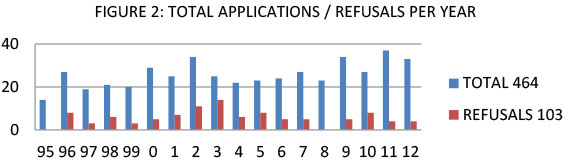

Between 1995 and the end of 2012, the Constitutional Court considered 464 applications for review.

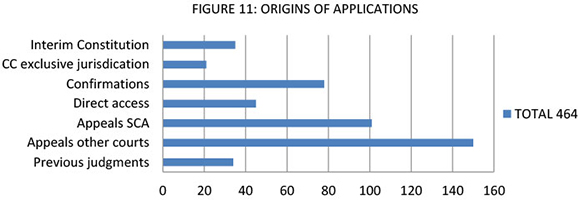

The ways in which these 464 applications reached the Court were as follows:

• 35 referrals in terms of the interim Constitution;

• 21 applications and referrals on matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court;

• 78 applications for confirmations of parliamentary or provincial laws and actions of the President;

• 45 applications for direct access to the Constitutional Court;

• 101 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal;

• 150 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of other Courts;

• 34 applications concerning previous judgments of the Court and other matters.

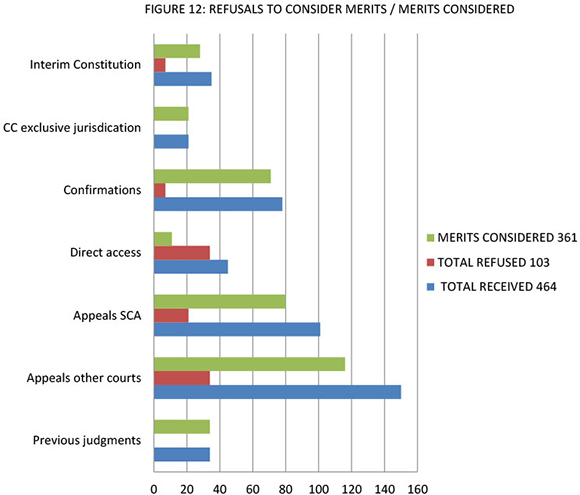

The Constitutional Court refused to consider applications in 103 instances and considered the merits of applications in 361 instances. The number of refusals per category is as follows:

• 7 refusals in respect of 35 referrals in terms of the interim Constitution;

• no refusals in respect of 21 applications and referrals on matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court;

• 7 refusals in respect of 78 applications for confirmations of parliamentary of provincial laws and actions of the President;

• 34 refusals in respect of 45 applications for direct access to the Constitutional Court;

• 21 refusals in respect of 101 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal;

• 34 refusals in respect of 150 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of other Courts;

• 34 applications concerning previous judgments of the Court and other matters.

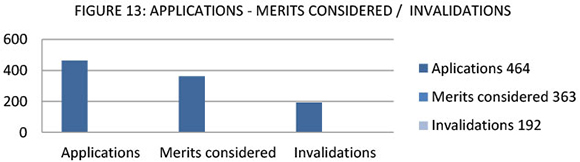

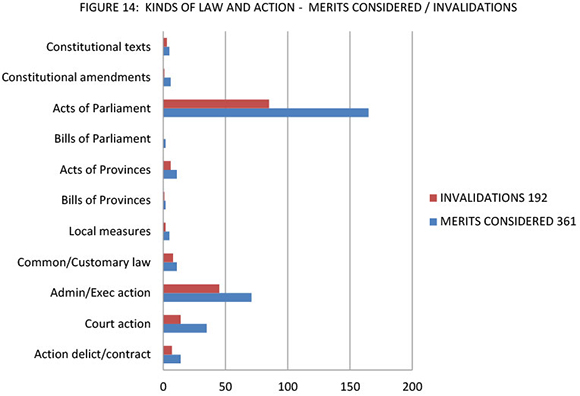

The Constitutional Court invalidated in 192 instances legal rules and actions of organs of state and individuals. These invalidations were done in respect of 464 applications for review in all the categories and they were done in respect of 361 instances in which the Court reviewed the merits of applications. 41.39% of the 464 applications received were invalidated. 53.18% of the applications of the merits were considered, was invalidated.

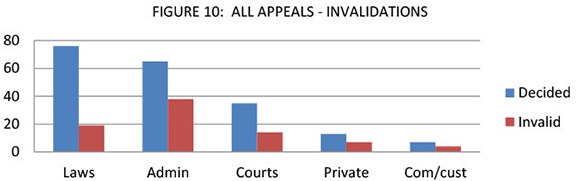

The invalidations in the different categories rules and action were as follows. In respects of:

• Draft constitutional texts - 3 refusals to certify out of 5 texts considered (60%);

• Constitutional amendments - 1 invalidation out of 6 considered (16.66%);

• Acts of Parliament - 85 invalidations out of 165 considered (51.51%);

• Bills of Parliament - 0 invalidations out of 2 considered (0%);

• Acts of Provinces - 6 invalidations out of 11 considered (54.54%);

• Bills of Provinces - 1 invalidations out of 2 considered (50%);

• Local government legislative measures - 2 invalidations out of 5 considered (40%);

• Common law and customary law - 8 invalidations out of 11 considered (72.72%);

• Administrative and executive action - 45 invalidations out of 71 considered (63,38%);

• Court discretionary action - 14 out of 35 considered (40%);

• Action in respect of delict and contract - 7 invalidations out of 14 considered (50%).

Keywords: Constitutional Court; Constitutional Court applications; Constitutional Court invalidations; Constitutional Court refusals to invalidate; Constitutional Court refusals to consider merits; Constitutional Court automatic referrals; Constitutional Court exclusive jurisdiction; Constitutional Court direct access; Constitutional Court direct appeals; Constitutional Court appeals; Constitutional Court confirmations.

Introduction

Unlike Parliament, other courts, legislative and executive institutions at all levels of government, the Constitutional Court was a completely new institution when it was instituted in 1994. The Court has been the guardian of all actions to give effect to the most comprehensive law reform programme that has ever been undertaken in South African history, namely the new constitutional dispensation. The major role it has played in the transformation of South African society and the legal system cannot be denied by anybody However, as could have been expected, everybody, and particularly everyone who forms part of some or other legal circle, has an opinion on how successful or otherwise the court has been in fulfilling this role. Opinions in this regard are often based on perceptions. The reason for this could be that the rather small number of high-profile judgments does not reflect the full picture of all the court's rulings and the effect it has had on society in general and on the legal system in particular.1

The purpose of this article is to reflect on the outcome of the counting and classifying of certain aspects of the Constitutional Court judgments delivered between 1995 and 2012. Although is it generally recognised that statistics cannot replace sound judgments, judgments based only on intuition and assumptions are usually not as sound as they could be. It is better to know than to guess, even if it is not uncommon afterwards to adapt what you know to suit your case.

This study's cut-off date of 31 December 2012 has no other significance than that it was the last date before the beginning of the year in which this article was written. However, since the Constitution Seventeenth! Amendment Act of 2012 expressly provides that the Constitutional Court now has jurisdiction to hear applications on non-constitutional matters, the figures contained in this article could be used at a later stage to determine what effect this amendment might have had on the functioning of the Court - that is, after the Court has been operating for some time as the so-called apex court.

Between 1995 and 2012, the Constitutional Court considered approximately 464 applications for review.2

However, the Court did not consider the merits of all the cases that came to its attention.3 There were approximately 103 instances in which the Court refused to consider the merits.4 These comprise 22.19 % of the total number of 464.

Section 172(1)(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996 provides that when deciding a constitutional matter within its power, every court must declare that any law or conduct that is inconsistent with the Constitution is invalid to the extent of it inconsistency. Between 1995 and the end of 2012 the Constitutional Court invalidated or confirmed the invalidation of laws or conduct in 192 instances. As indicated in the first chart in paragraph 7.3 below, these invalidations represent 41.38% of the applications it received during the period and 53.18% of the instances in which it considered the merits of applications.

There are various ways in which applications reach the Constitutional Court. In this article, these pathways were used as the categories in respect of which the counting was done. These categories are the following (the numbers refer to the sections in which they are discussed below):

1 Referrals by other courts in terms of the interim Constitution.5

2 Referrals of matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court.

3 Confirmations of invalidations by other courts of parliamentary and provincial laws, and actions of the President.

4 Applications for direct access.

5 Appeals.

5.1 Applications for appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal.

5.2 Applications for direct appeal against judgments of courts other than the Supreme Court of Appeal.

6 Applications relating to previous orders of the Constitutional Court and other matters.

In respect of each category, the measured variables which are discussed in the sections below are: firstly, the number of applications dealt with by the Court; secondly, the number of refusals by the Court to consider certain applications and the reasons for doing so; and thirdly the outcome of the consideration of the merits of applications in terms of the validity or invalidity of the laws and actions reviewed by the Court.6.

1 Automatic referrals by other courts in terms of the interim Constitution

1.1 General

The provisions of the interim Constitution which dealt with the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court were extremely complex.7 Matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court included the constitutionality of all Acts and Bills of Parliament, disputes of a constitutional nature between state organs and other matters entrusted to the Court by other legislation.8

The Supreme Court of Appeal had no jurisdiction to adjudicate on any matter within the jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court.9 However, a constitutional matter could on appeal from a provincial Division of the High Court come before the court in matters that involved both constitutional and other disputes. If the Division could not dispose of the appeal without a finding on the constitutional dispute, the Division has to refer the constitutional dispute to the Constitutional Court.10

Provincial Divisions of the High Court had jurisdiction on a wide range of constitutional matters within their areas of jurisdiction and parties before a Court could for the purposes of a particular case agree that the provincial Court would exercise jurisdiction in matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court.11 The rules for referring constitutional matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court to the Court were complicated12 and it serves no purpose to repeat them here. This project was not a success.

One of the advantages of "experimenting" within the framework of an interim constitution is that less successful enterprises need not be repeated. The Supreme Court of Appeal now has jurisdiction on all constitutional matters that do not fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court.13 Divisions of the High Court similarly have no jurisdiction on matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court,14 but may decide any other constitutional matter except a matter which the Constitutional Court has agreed to hear directly in terms of section 167(6)(a) of the Constitution.15

Between 1995 and 1998 a total number of 35 cases were referred to the Constitutional Court by other Courts in terms of the interim Constitution. They constituted 44.30% of the 79 cases considered by the Court in the years 1995, 1996, 1997 and 1998. It was the single greatest source of cases during these years. The cases represent 7.54% of all cases considered by the Court during 1995 to 2012.

The breakdown per year is as follows: 1995 - 12; 1996 - 15; 1997 - 5; 1998 - 3. Of the 35 cases, the Supreme Court of Appeal referred 3 cases.16 The referrals from the other courts were:17 Eastern Cape Division (Grahamstown) - 1; Gauteng Division (Johannesburg) - 8; Gauteng Division (Pretoria) - 11; KwaZulu-Natal Division (Durban) - 1; KwaZulu-Natal Division (Pietermaritzburg) - 2; Western Cape Division (Cape Town) - 8; and 1 combined referral from the Western Cape Division (Cape Town) and the Eastern Cape Division (Port Elizabeth).

The new Constitution abolished this system. After 1998 no referrals occurred in terms of these provisions.

1.2 Refusals to consider the merits of applications

In the case of 7 of the 35 referrals that took place between 1995 and the end of 1998, the Constitutional Court refused to consider the merits of the cases - 6 in 1996 and 1 in 1997. The reasons for these refusals included that

- the issue was moot;18

- the relevant incidents took place before the commencement of the interim Constitution and that the interim Constitution thus did not apply to them;19

- the application of the interim Constitution would not be decisive for the resolution of the dispute;20 and

- the issue was not ripe for referral because the Court a quo did not investigate whether the interim Constitution would be decisive for the case.21

1.3 Invalidations

The Constitutional Court considered the merits of applications in this category in 28 of the applications. The Court invalidated provisions of Acts of Parliament in 19 instances. In 8 cases the Court sustained the validity of Acts of Parliament and in 1 case the validity of a local government legislative action.

2 Matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court

2.1 General

Section 167(4) of the Constitution provides that only the Constitutional Court has jurisdiction on (a) disputes between organs of state in the national and provincial spheres concerning the constitutional status, powers or functions of any of those organs, (b) the constitutionality of national and provincial Bills when the President or a provincial Premier has reservations about the constitutionality of the Bill, (c) the constitutionality of Acts of Parliament or a provincial legislature at the request of one third of the members of the relevant legislature within 30 days after the Act was signed by the President or the Premier, (d) the constitutionality of constitutional amendments, (e) alleged failure by the President or Parliament to fulfill constitutional duties, and (f) the certification of provincial Constitutions.22 Except in respect of (e), the Constitutional Court has not encountered problems in interpreting and applying section 167(4). Section 167(4)(e) read with section 172(2)(a) provides a very rare example of poor draftsmanship in the Constitution. Section 167(4)(e) provides that findings on non-compliance with constitutional obligations by Parliament fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court, whereas section 172(2)(a) provides that the Supreme Court of Appeal, the High Court of South Africa or a Court of similar status may make an order concerning the constitutionality validity of a parliamentary or provincial act or the conduct of the President, but that an order of constitutional invalidity has no force unless it is confirmed by the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court has not yet reconciled the provisions of sections 167(4)(e) and 172(2)(a) satisfactorily. The Court's efforts in this regard include arguments that the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court does not include obligations to comply with the Bill of Rights;23 that it covers only non-compliance with duties of Parliament which involve the exercise of a discretion, which are not readily ascertainable, and the exercise of which are likely to cause disputes;24 and that actions which involve only the President or only Parliament are included, but not actions in which the President or Parliament has to cooperate with others in performing the action.25 Although the confirmation by the Constitutional Court of certain invalidations by the other Courts is, strictly speaking, also a matter within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court,26 such confirmations are discussed separately in paragraph 3 below.

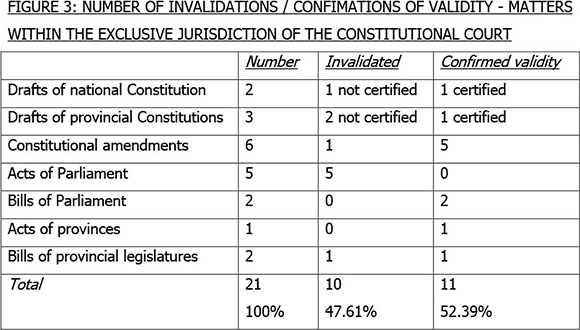

In the years 1995 to 2012 the Constitutional Court considered matters within its exclusive jurisdiction in 21 cases - that is, in 4.52% of the 464 cases considered in this period.27 The subject matter covered in these cases was as follows:

(a) Disputes between organs of state were considered in 3 cases; all these cases involved applications by provincial governments.28

(b) 1 case concerned a reference by a provincial Premier in terms of section 121(2) of the Constitution and involved the constitutionality of a provincial Bill.29

(c) The constitutionality of Parliamentary or provincial Acts (or Bills in the case of the interim Constitution) referred to the court by Speakers of legislatures at the request of at least one third of the members of the legislature concerned was at stake in 4 cases.30

(d) 6 cases concerned applications for direct access in respect of constitutional amendments.31

(e) 1 case concerned obligations of Parliament to fulfill its duties.32

(f) 1 case concerned the non-observance of obligations by the President.33

(g) 3 cases concerned the certification of provincial Constitutions,34 and 2 the certification in terms of section 71 of the interim Constitution of the new national Constitution.35

2.2 Refusals to consider the merits of referrals/ applications

There were no refusals to consider the merits of applications in any of the applications referred to in this paragraph.

2.3 Invalidations

In exercising its jurisdiction on matters within its exclusive jurisdiction between 1995 and the end of 2012, the Constitutional Court considered

- 2 drafts of the new national Constitution - it refused to certify the first draft and certified the second;

- 3 draft provincial Constitutions - it refused to certify 2 drafts and certified 1;

- 6 constitutional amendments - it invalidated 1 amendment and confirmed the validity of 5 amendments;

- 5 Acts of Parliament - it invalidated the 5 Acts;

- 2 parliamentary Bills - it confirmed the validity of both Bills;

- 1 Act of a provincial legislature - it confirmed the validity of the Act;

- 2 provincial Bills - it invalidated 1 Bill and confirmed the validity of 1 Bill.

3 Confirmations of invalidations by other courts of actions of the President and Acts of Parliament and Provinces

3.1 General

Section 167(5) of the Constitution provides that the Constitutional Court must confirm any order of invalidity made by the Supreme Court of Appeal, the High Court, or a Court of similar status, before that order can have any force.36 Section 167(2)(a) repeats this provision. Section 167(2)(c) provides that national legislation must provide for the referral of an order of invalidity to the Constitutional Court.

The Constitutional Court has explained that the purpose of the confirmation procedure is "to preserve the comity between the judicial branch of government on the one hand, and the legislative and executive branches of government, on the other, by ensuring that only the highest court in constitutional matters intrudes into the domain of the principal legislative and executive organs of state",37 and to ensure "that certainty is obtained as to the constitutionality of Acts of Parliament where that has been challenged".38

Section 167(2)(d) of the Constitution provides that any person or organ of state with sufficient interest may appeal, or apply directly to the Constitutional Court to confirm or vary an order of constitutional invalidity. The Constitutional Court has explained that although referrals of orders of constitutional invalidity are peremptory, provision has nevertheless been made for appeals and direct access because an appeal may permit more issues to be examined than would be the case in a mere referral.39

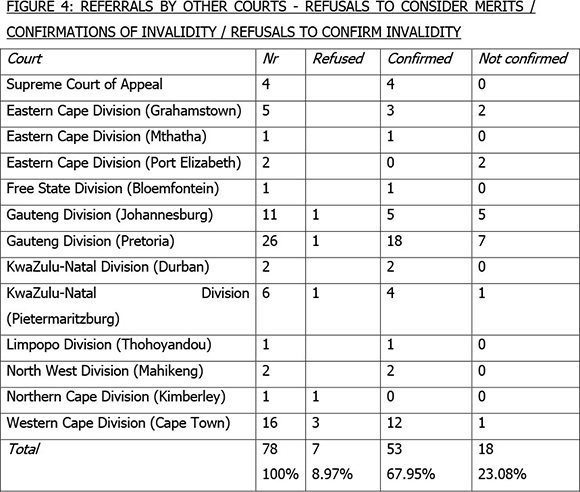

In the years 1995 to 2012 there were 74 instances in which the Constitutional Court considered confirmation of invalidations - that is, 15.94% of the 464 cases considered from 1995 to 2012.40 In 4 instances the Court considered invalidations of the same legislation by two different courts41 and the Constitutional Court thus considered 78 invalidations by individual courts. The numbers of invalidations from respectively the Supreme Court of Appeal and each one of the Divisions of the High Court considered is indicated in table paragraph 3.3 below.

3.2 Refusals to consider applications for confirmation

The Constitutional Court refused to consider 7 applications for confirmation of invalidity emanating from High Court Divisions42 - 1 application concerned an invalidation by the Gauteng Division (Johannesburg), 1 concerned an invalidation by the Gauteng Division (Pretoria), 1 concerned an invalidation by the KwaZulu-Natal Division (Pietermaritzburg), 1 concerned an invalidation by the Northern Cape Division (Kimberley); and 3 concerned invalidations by the Western Cape Division (Northern Cape).

In 2 of these 7 instances, the Court refused to consider the merits of the other Courts' invalidations because the issues were moot, either because the invalidity of the statutory provision had already earlier been confirmed by the Constitutional Court, 43 or because by the time the confirmation of invalidity was to be considered, Parliament had already passed legislation that rectified the defects in the invalidated legislation.44 The Court held that when an invalidated Act was repealed before the Constitutional Court had been able to consider the confirmation, the Court would, however, still deal with the application if the invalidation order might indeed have a practical effect.45 In 3 instances the Constitutional Court refused to decide the confirmation issue because the confirmation procedure did not apply to the invalidations concerned, either because the invalidation of ministerial regulations issued in terms of a statute was involved,46 or because it concerned an invalidation of actions of the President that need not be confirmed,47 or because the organs of state involved did not try to resolve the issues at a political level as required by section 41(1)(h)(vi) of the Constitution.48 In 1 instance the Court referred the matter back to the invalidating Court, because that Court invalidated only one provision of the Act concerned instead of considering all the provisions.49

3.3 Confirmation of invalidations

After considering the invalidations, the Constitutional Court did not confirm the invalidations in 18 cases. 3 instances concerned action by the President, 4 concerned provincial legislation and the rest concerned Acts of Parliament. The position in respect of confirmation or non-confirmation of the referrals from the Supreme Court of Appeal and Divisions of the High Court is as follows:

In the period 1995 to the end of 2012, the Constitutional Court

- confirmed in 4 instances the invalidation of proclamations and actions of the President;50

- confirmed the invalidation of provisions of provincial legislatures in 4 instances51 and refused to confirm the invalidation of provisions of provincial legislatures in 3 instances;52

- confirmed the invalidation of existing common law and its development to bring it in line with previous understanding of the rules concerned;53

- confirmed the invalidation of common law and provisions in an Act of Parliament in a combined confirmation;54

- confirmed the invalidation of customary law and provisions in an Act of Parliament in a combined confirmation;55

- confirmed the invalidation of provisions of Acts of Parliament in 42 instances and refused to confirm the invalidation of provisions of Acts of Parliament in 15 instances.

The Constitutional Court therefore confirmed invalidations in 53 instances and refused to confirm invalidations in 18 instances.

4 Direct access

4.1 General

Section 167(6)(a) of the Constitution provides that national legislation or the rules of the court must allow a person, when it is in the interests of justice do so, to bring a matter directly to the Constitutional Court. Such direct access requires the leave of the Constitutional Court. Direct access to the Constitutional Court involves instances where a constitutional issue that can also be heard by other courts is raised without having been considered by those courts.56 In these instances the Constitutional Court is approached outside the context of an appeal. (There may, however, be circumstances in which direct access may be granted in respect of an issue on which an appeal is pending in a provincial Court, if deciding the matter will fill a gap concerning a matter already on appeal from the Supreme Court of Appeal before the Constitutional Court, a decision on both matters will inevitably be the same and the Supreme Court of Appeal has devoted considerable attention to both matters when it dealt with the second matter.)57 When considering applications for direct access, the Constitutional Court has always emphasized that direct access is an extraordinary procedure to be followed in exceptional circumstances only58 and this category of applications for access to the Constitutional Court therefore inevitably contains a very high percentage of instances in which applications have been refused.59

During the years 1995 to 2012, 45 applications for direct appeal were considered by the Constitutional Court.60

4.2 Refusal of applications for direct access

34 applications were refused of the 45 applications reported, that is 75.66%. The most prevalent reasons provided by the Constitutional Court for refusing applications were that

- there was no prospect of success for the applications;61

- there was no urgency to hear the case;62

- there were too many factual matters to be resolved by lower courts;63 and

- the applicants provided no special reasons for direct access apart from the fact that the legislation or action might be unconstitutional; this is not a ground for direct access.64

Other reasons provided by the Constitutional Court were that the Court lacked jurisdiction to hear the case,65 that the application was premature because an appeal was pending,66 that the applicants confused direct access with an appeal procedure because they sought the nullification of the judgment of another Court,67 that the applicant tried to raise new issues in a separate procedure,68 and that the issue was moot.69

4.3 Invalidations

After considering the merits of direct applications in 11 instances, the Constitutional Court

- invalidated Acts of Parliament in 4 instances,70 and refused to invalidate Acts of Parliament in 3 instances;71

- invalidated common-law rules and provisions of an Act of Parliament in reaction to a single application;72

- invalidated the determination of the number of seats allocated to a provincial legislature by the Electoral Commission;73

- invalidated in two instances the actions of the registrar of the Constitutional Court74 and the registrar of a Division of the High Court.75

The Constitutional Court therefore invalidated in 8 instances and refused to invalidate in 3 instances.

5 Appeals

5.1 General

The Constitutional Court is first and foremost a court of appeal. From 1995 until the end of 2012, the Court considered 251 applications for leave to appeal. Since the commencement of the present Constitution, the Supreme Court of Appeal and the Divisions of the High Court have had jurisdiction to decide all constitutional matters which do not fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court. Whilst it could have been expected that the normal flow of appeals from the provincial levels would therefore be through the Supreme Court of Appeal, this has not happened. As is indicated below in paragraph 5.3.1, section 167(6)(b) of the Constitution provides that a person may appeal directly to the Constitutional Court from any other court when it is in the interests of justice and with leave of the Constitutional Court. The applications concerning the decisions of other Courts outnumbered the applications against decisions of the Supreme Court of Appeal. From 1995 to the end of 2012, the Constitutional Court considered approximately 101 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal and 150 applications for leave to appeal against the judgments of other courts. In the following paragraphs the figures concerning these two sources of appeal are provided separately in paragraphs 5.2 and 5.3. In paragraph 5.4 an account of the combined figures is provided.

It must be noted that as far as invalidations are concerned, there were instances in which judgments contained findings of both validity and invalidity; in this survey they are recorded as invalidations. It must further be noted that findings of invalidity of administrative, executive, judicial and private actions were based not only on inconsistencies with the Constitution, but also on being inconsistent with other legal rules. This is due to the fact that the Constitutional Court has increasingly assumed jurisdiction on constitutional matters without applying constitutional provisions in reaching conclusions on the merits of applications.76

5.2 Appeals against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal

5.2.1 General

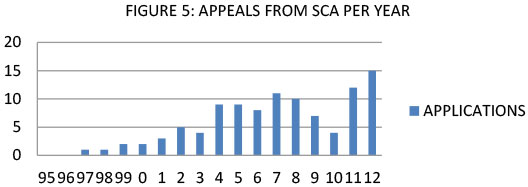

Between 1995 and the end of 2012 the Constitutional Court considered 101 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal. These applications represent 21.76% of the 464 cases which the Court considered during this period. Since 1995 there has been a steady increase in the number of applications per year.77

5.2.2 Refusals

In 21 cases the applications for leave to appeal were refused. This number comprises 20.79% of the 101 applications considered. The grounds for refusing applications included that

- there was no prospect of success;78

- the issue was moot;79

- the application related to an issue not raised in the Court a quo;80

- the determination of a matter concerning children's rights should not be postponed by further appeals;81

- no constitutional issues were involved;82

- common-law issues were involved which must first be considered by the Supreme Court of Appeal;83

- late filings of applications were not condoned;84 and

- applications for conditional appeals and pending appeals to other forums were not acceptable.85

5.2.3 Invalidations

26 of the 80 applications in which the Court considered the merits of the appeals involved Acts of Parliament; 4 involved common law and customary law; 23 involved executive and administrative action; 18 involved discretionary actions of courts a quo, and 9 involved the actions of private persons and the state within the framework of delictual actions.

In the course of considering the merits of appeals against decisions of the Supreme Court of Appeal, the Constitutional Court invalidated

- Acts of Parliament in 4 instances;86

- rules of the common law and rules of customary law in 2 instances;87

- administrative and executive action in 16 instances,88 1 of which was in respect of action of the President;89

- discretionary action such as maintenance orders, sentencing, the admissions of evidence and recusals in 8 instances;90 and

- action based on delict and breach of contract in 3 instances91 and delictual actions against the state in 3 instances.92

5.3 Direct appeals from Courts other than the Supreme Court of Appeal

5.3.1 General

Section 167(6)(b) of the Constitution provides that national legislation or the rules of the court must allow a person, when it is in the interests of justice to do so, to apply for leave to appeal directly to the Constitutional Court from any other Court. Such an application requires the leave of the Constitutional Court. A "direct" appeal to the Constitutional Court involves that the Constitutional Court hears an appeal when another Court has concurrent jurisdiction to hear that same appeal and has not yet done so. This provision therefore deals with situations in which the Supreme Court of Appeal is bypassed, and enables the Constitutional Court to hear an appeal regardless of whether or not there is a right of appeal to any other Court in terms of either the Constitution or another statute.93

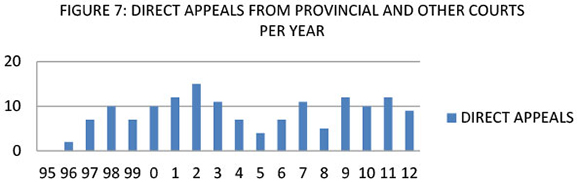

Between 1995 and the end of 2012 the Constitutional Court considered 150 applications for leave to appeal directly to the Constitutional Court. (In one instance the Constitutional Court considered appeals on the same subject matter from two different High Court Divisions94 and two applications were noted for the purposes of this article.) The applications for direct access represent 32.32% of the 464 cases which the Court considered during this period. This constitutes the largest category of applications considered by the Court.

The applications for leave to appeal against judgments of particular Courts are as follows (the number of refusals to hear applications are also included in the table):

5.3.2 Refusals

The Constitutional Court refused the merits of appeals in 34 instances. The reasons for the refusals included that:

- new issues involving the common law must first be considered by the Supreme Court of Appeal;95

- there was no urgency;96

- the issue involved action that pre-dated the commencement of the Constitution;97

- there was no prospect of success;98

- appeals against obiter conclusions are usually not allowed;99

- the issue was moot;100

- no constitutional or legal issue was involved;101

- all the parties concerned were not joined;102

- the applicants failed to apply for leave to appeal from the Supreme Court of Appeal;103

- the applicants challenged the wrong legislative provision;104

- the matter must first be considered by the Labour Appeal Court and there was no indication that the latter court could deal with the matter speedily;105

- the issues raised were not considered by the courts a quo;106

- an application to the Supreme Court of Appeal for leave to appeal on the same issue was still pending.107

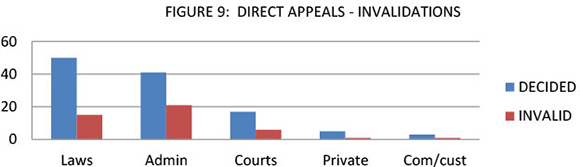

5.3.3 Invalidations

Of the 116 applications in which the court considered the merits of the appeals,

- 53 involved statutory and common law and of these:

- 43 involved Acts of Parliament of which 11 were invalidated;108

- 3 involved provincial laws of which 2 were invalidated;109

- 4 involved local legislative measures of which 2 were invalidated; 110 and

- 3 involved rules of the common law of which 2 were invalidated.111

Of the 116 applications in which the court considered the merits of appeals, 41 involved administrative and executive acts. Of these, 3 involved actions of the President of which 1 was invalidated;112 and 38 involved other administrative and executive acts of which 21 were invalidated.113

Of the 116 applications, 17 involved discretionary actions of courts a quo of which 6 were invalidated.114

5 of the 166 applications involved actions of private persons and institutions and in only in 1 instance was the action held to be unlawful.115

5.4 Combined figures concerning appeals

The Constitutional Court received 251 applications for leave to appeal from all other courts. This constitutes 54.09% of the 464 applications and referrals it considered from 1995 until the end of 2012.

The Court refused to consider the merits of applications in 55 instances, that is, in respect of 21.91% of the applications for leave to appeal received. It therefore made decisions on the merits of applications for leave to appeal in 196 instances.

After considering the merits of the 196 applications, the Court invalidated

- 15 Acts of Parliament after reviewing 69 Acts;

- 2 provincial laws after reviewing 3 laws;

- 2 local government legislative provisions after reviewing 4 provisions;

- 38 executive and administrative actions including 2 of the President, after reviewing 65 actions;

- 4 common law and customary law rules after reviewing 7 cases;

- 14 lower court exercises of discretion after reviewing 35 instances;

- 7 private law cases after reviewing 13 cases.

6 Applications relating to previous court orders and other matters

The last category of application concerns applications relating to previous orders of the Constitutional Court and a few other matters. The category consists of 34 applications, that is 7.32% of the 464 applications considered by the Constitutional Court. 16 of the applications dealt with the amendment of previous orders,116 8 with the determination of costs concerning previous judgments and the rest with the recusal of judges,117 the reopening of an appeal,118 postponements of appeal hearings,119 the admission of amici curiae,120 and the effect of previous orders on other provinces121 and previous legislation.122 There was also one judgment in which the court made a mero motu announcement about its own quorum requirements.123 In this category, no refusals to hear applications or "invalidations" are noted - it would be inappropriate to consider the determination of costs and reversal of previous cost orders or amendment to previous orders of the court itself as "invalidations".

7 Summary and notes

Between 1995 and the end of 2012 the Constitutional Court considered 464 applications for review.

7.1 How did the cases reach the court?

The ways in which these 464 applications reached the Court were as follows:

- 35 referrals in terms of the interim Constitution;

- 21 applications and referrals on matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court;

- 78 applications for confirmations of parliamentary or provincial laws and actions of the President;

- 45 applications for direct access to the Constitutional Court;

- 101 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal;

- 150 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of other Courts;

- 34 applications concerning previous judgments of the Court and other matters.

Since the Constitutional Court is primarily a court of appeal, it is not surprising that by far the greatest number of applications (251 out of 464, that is, 54.09%) consists of applications for leave to appeal against judgments of other courts. What is noticeable, however, is that the majority of these applications were for so-called direct appeal in terms of section 167(6)(b) of the Constitution, in which efforts were made to bypass the Supreme Court of Appeal.124 About 50% more applications were received against judgments of the other Courts. Although the reasons which the Constitutional Court provided for refusing to accede to requests to appeal directly from other Courts to the Constitutional Court include a few references to the fact that the appeal must first be heard by the Supreme Court of Appeal,125 the majority of reasons, as can be expected, are similar to those that applied to applications which emanated from Supreme Court of Appeal judgments.126 Add to this that the percentages of applications which the Constitutional Court refused to consider are in both instances almost the same, namely 21% in the case of applications against the Supreme Court of Appeal and 22.66% in the case of applications against other courts.127 Whatever its motivations and intentions might have been, the outcome of the Constitutional Courts willingness to hear direct appeals from other Courts was that the Constitutional Court provided the Supreme Court of Appeal with some relief from its extremely heavy case load, particularly as far as constitutional matters were concerned. This trend is likely to continue in future and it is even likely to gain momentum as far as non-constitutional matters are concerned. Section 167(3) of the Constitution was amended by the Constitution Seventeenth Amendment Act and now provides that the Constitutional Court may decide on constitutional matters and "any other matter, if the Constitutional Court grants leave to appeal on the grounds that the matter raises an arguable point of law of general public importance which ought to be considered by the Constitutional Court".128

7.2 In how many instances did the court refuse to consider the applications?

The Constitutional Court refused to consider applications in 103 instances and considered the merits of applications in 361 instances. The number of refusals per category is as follows:

- 7 refusals in respect of 35 referrals in terms of the interim Constitution;

- no refusals in respect of 21 applications and referrals on matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court;

- 7 refusals in respect of 78 applications for confirmations of parliamentary or provincial laws and actions of the President;

- 34 refusals in respect of 45 applications for direct access to the Constitutional Court;

- 21 refusals in respect of 101 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal;

- 34 refusals in respect of 150 applications for leave to appeal against judgments of other Courts.

A noteworthy feature of these figures is that the percentages of applications in respect of which the Constitutional Court refused to consider the merits of applications in terms of the interim Constitution (20%), matters within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court (0%), applications concerning the confirmation of invalidations by other courts (8.97%) and appeals against the judgments of other courts (21.91%) are relatively small compared to the high percentage of refusals in the case of direct applications, namely 75.55%. Although many of the reasons provided by the court for its refusals in this regard are no different from the reasons for refusals in other instances, the court's reluctance to act can clearly be attributed to a reluctance to act as a court of "first and final instance". "Direct access" to the Constitutional Court is available in exceptionally urgent and otherwise unavoidable circumstances only. Although this path chosen by the Constitutional Court could be criticized as leading to a virtual negation of the possibility of direct access, particularly in the case of poor people,129 it is founded upon the basic principle of all appeal systems, namely that justice requires that court decisions should in principle never be the outcome of the deliberations of a single court. This is a sound principle. The Constitutional Court explained it as follows in Bruce v Fleecytex Johannesburg CC:130

It is not ordinarily in the interests of justice for a court to sit as a court of first and final instance, in which matters are decided without there being any possibility of appealing against the decision given. Experience shows that decisions are more likely to be correct if more than on court has been required to consider the issues raised. In such circumstances the losing party has an opportunity of challenging the reasoning on which the first judgment is based, and of reconsidering and refining arguments previously raised in the light of such judgment.

7.3 In how many instances did the Court invalidate laws and action?

The Constitutional Court invalidated in 192 instances legal rules and actions of organs of state and individuals. These invalidations were done in respect of 464 applications received for review in all the categories and they were done in respect of 361 instances in which the Court reviewed the merits of applications. 41.39% of the 464 applications received were invalidated. 53.18% of the applications where the merits were considered were invalidated.

The invalidations in the different categories in respect of various kinds of law and action were as follows. In respects of:

- Draft constitutional texts - 3 refusals to certify out of 5 texts considered (60%);

- Constitutional amendments - 1 invalidation out of 6 considered (16.66%)-;

- Acts of Parliament - 85 invalidations out of 165 considered (51.51%);

- Bills of Parliament - 0 invalidations out of 2 considered (0%);

- Acts of Provinces - 6 invalidations out of 11 considered (54.54%);

- Bills of Provinces - 1 invalidation out of 2 considered (50%);

- Local government legislative measures - 2 invalidations out of 5 considered (40%);

- Common law and customary law - 8 invalidations out of 11 considered (72.72%);

- Administrative and executive action - 45 invalidations out of 71 considered (63,38%);

- Court discretionary action - 14 out of 35 considered (40%);

- Action in respect of delict and contract - 7 invalidations out of 14 considered (50%).

Acts of Parliament constitute the largest category of applications considered, to which the Constitutional Court reacted by invalidating some of the provisions considered. The real impact of the invalidation of legal rules can be assessed only by an analysis of the contents of invalidation orders and such an exercise was not the focus of this investigation. It is also very important to note that even refusals to formally invalidate legal rules could change the status quo in respect of the meaning of those rules. The Constitutional Court follows a rule that when legislation can be interpreted in more than one way and at least one of the interpretations amounts to a reasonable interpretation that does not conflict with the Bill of Rights, that particular interpretation must be followed.131 This means that without invalidating a legal rule, it may be assigned a meaning which it previously did not have.

Administrative, executive and private actions which were performed in terms of legal rules which the Court invalidated were, of course, also invalidated, but because such invalidity ensued from the invalidity of the authorising law, they were not counted in the last three categories - that is, those concerning administrative, executive, discretionary court and private action. The latter categories therefore concerned the invalidation of actions performed in terms of valid legal rules.

The category Administrative and Executive action includes 8 applications in which the constitutionality of actions of the President were considered. There were 5 invalidations of actions of the President132 and 3 instances in which the Court refused to invalidate the action.133

Processes of counting and classifying can be frustrating because they abound with pitfalls (more accurately "potholes" in the South African context) relating to incorrect counts and the subjectivity of classifications - ask anyone who grew up on a sheep farm about the frustrations of the numerous outcomes of counting the same flock over and over. However, it has to be done, even if it produces no more than a small contribution for improving the quality of the bigger debates that will follow sooner or later, after we have reached home after dusk.

Bibliography

Cachalia et at Fundamental Rights. Cacahlia A et at Fundamental Rights in the New Constitution (Juta Kenwyn 1994) [ Links ]

Currie and De Waal Bill of Rights Handbook. Currie I and De Waal J The Bill of Rights Handbook 5th ed (Juta Cape Town 2005) [ Links ]

Dugard 2006 SAJHR. Dugard J "Courts of first and final instance? Towards a pro-poor jurisdiction for the South African Constitutional Court" 2006 SAJHR 261-282 [ Links ]

Lewis 2009 LQR. Lewis J "The Constitutional Court of South Africa: an evaluation" 2009 LQR 440-460 [ Links ]

Meydani Israeli Supreme Court. Meydani A The Israeli Supreme Court and the Human Rights Revolution -Courts as Agenda Setters (Cambridge University Press New York 2011) [ Links ]

O'Regan 2012 SAJHR. O"Regan K "Discourse and debate" 2012 SAJHR 116-134 [ Links ]

Rautenbach "Teaching an 'Old Dog' New Tricks?" Rautenbach C "South Africa: Teaching an 'Old Dog' New Tricks? An Empirical Study of the Use of Foreign Precedents by the South African Constitutional Court" (1995-2010) in Groppi T and Ponthoreau M-C (eds) The Use of Foreign Precedents by Constitutional Judges (Hart Oxford 2013) 185-209 [ Links ]

Rautenbach and Du Plessis 2013 German Law Journal. Rautenbach C and Du Plessis L "In the Name of Comparative Constitutional Jurisprudence: The Consideration of German Precedents by South African Constitutional Court Judges" 2013 German Law Journal 1539-1577 [ Links ]

Rautenbach General Provisions. Rautenbach IM General Provisions of the South African Bill of Rights (Butterworths Durban 1995) [ Links ]

Rautenbach Constitutional Law. Rautenbach IM Rautenbach-Malherbe Constitutional Law 6th ed (LexisNexis Durban 2012) [ Links ]

Rautenbach and Heleba 2013 TSAR. Rautenbach IM and Heleba S "The Jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court in non-constitutional matters in terms of het Constitution Seventeenth Amendment Act of 2012" 2013 TSAR 405-418 [ Links ]

Register of legislation

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 200 of 1993

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Superior Courts Bill B 7B-2011

Register of court cases

Abahlali Basemjondolo Movement SA v Premier of the Province of KwaZulu-Natal 2010 2 BCLR 99 (CC)

African National Congress v Chief Electoral Officer IEC 2009 10 BCLR 971 (CC), 2010 5 SA 487 (CC)

Albutt v Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 2010 5 BCLR 391 (CC), 2010 3 SA 293 (CC)

Alexcor Ltd v Richtersveld Community 2003 12 BCLR 1301 (CC), 2004 5 SA 460 (CC)

August v Independent Electoral Commission 1999 4 BCLR 382 (CC), 1999 3 SA 1 (CC)

AZAPO v President of the RSA 1996 8 BCLR 1015 (CC), 1996 4 SA 671 (CC)

Bannatyne v Bannatyne 2003 2 BCLR 111 (CC), 2003 2 SA 363 (CC)

Bato Star Fishing (Pty) Ltd v Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism 2004 7 BCLR 687 (CC), 2004 4 SA 490 (CC)

Bengwenyama Minerals (Pty) Ltd v Genorah Resources (Pty) Ltd 2011 3 BCLR 229 (CC), 2011 4 SA 113 (CC)

Besserglik v Minister of Trade and Industry and Tourism 1996 6 BCLR 745 (CC), 1996 4 SA 331 (CC)

Bhe v Khayelitsha Magistrate; Sibi v Sithole 2005 1 BCLR 1 (CC), 2005 1 SA 580 (CC)

Billiton Alimintum SA Ltd t/a Hillside Aluminium v Khanyile 2010 5 BCLR 422 (CC)

Boesak v S 2001 1 BCLR 36 (CC), 2001 1 SA 912 (CC)

Bogaards v S 2012 12 BCLR 1261 (CC)

Bruce v Fleecytex Johannesburg CC 1998 4 BCLR 415 (CC), 1998 2 SA 1143 (CC)

Brümmer v Gorfil Bros Investment (Pty) Ltd 2000 5 BCLR 465 (CC), 2000 2 SA 837 (CC)

Carmichele v Minister of Safety and Security and the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2001 10 BCLR 995 (CC), 2001 4 SA 938 (CC)

Certification of the Amended Text of the Constitution of the RSA, 1996 1997 1 BCLR 1 (CC), 1997 2 SA 97 (CC)

Certification of the Amended Text of the Constitution of the Western Cape 1997 12 BCLR 1653 (CC), 1998 1 SA 655 (CC)

Certification of the Constitution of Province of KwaZulu-Natal, 1996 1996 11 BCLR 1419 (CC), 1996 4 SA 1098 (CC)

Certification of the Constitution of the RSA, 1996 1996 10 BCLR 1253 (CC), 1996 4 SA 744 (CC)

Certification of the Constitution of the Western Cape, 1997 1997 9 BCLR 1167 (CC), 1997 4 SA 1076 (CC)

Chagi v Special Investigating Unit 2009 3 BCLR 227 (CC), 2009 1 SACR 339 (CC)

Chirwa v Transnet Ltd 2008 3 BCLR 251 (CC), 2008 4 SA 367 (CC)

Chonco v President of the RSA 2010 6 BCLR 511 (CC)

Christian Education of SA v Minister of Education 1998 12 BCLR 1449 (CC), 1999 2 SA 83

City Council of Pretoria v Walker 1998 3 BCLR 257 (CC), 1998 2 SA 363 (CC)

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality v Blue Moonlight Properties (Pty) Ltd 2012 2 BCLR 150 (CC), 2012 2 SA 104 (CC)

Competition Commission of SA v Senwes Ltd 2012 7 BCLR 667 (CC)

Competition Commission v Yara SA (Pty) Ltd 2012 9 BCLR 932 (CC)

Crown Restaurant CC v Gold Reef City Theme Park (Pty) Ltd 2007 5 BCLR 453 (CC), 2008 4 SA 16 (CC)

Democratic Alliance v President of the RSA 2012 12 BCLR 1261 (CC)

Department of Land Affairs v Goedgelegen Tropical Fruits (Pty) Ltd 2007 10 BCLR 1027 (CC), 2007 6 SA 199 (CC)

Director of Public Prosecutions: Cape of Good Hope v Robinson 2005 2 BCLR 103 (CC), 2002 6 SA 642 (CC)

Director of Public Prosecutions: Cape of Good Hope v Robinson 2005 3 BCLR 231 (CC), 2005 4 SA 1 (CC)

Dlamini, Dladla, Joubert, Schietekat v State 1999 7 BCLR 771 (CC), 1999 4 SA 632 (CC)

Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly 2006 12 BCLR 1399 (CC), 2006 6 SA 416 (CC)

Dudley v City of Cape Town 2004 8 BCLR 805 (CC), 2005 5 SA 429 (CC)

Electoral Commission of the RSA v Inkatha Freedom Party 2011 9 BCLR 943 (CC)

Engelbrecht v Road Accident Fund 2007 5 BCLR 457 (CC), 2007 6 SA 96 (CC)

Ex parte Mercer 2003 1 SA 203 (CC)

Ex parte Omar 2003 10 BCLR 1087 (CC), 2004 2 SA 284 (CC)

Ex parte Western Cape Provincial Government: In re DVB Behuising v North West Provincial Government 2000 4 BCLR 147 (CC), 2000 1 SA 500 (CC)

Executive Council of the Province of the Western Cape v Minister of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development; Executive Council of KwaZuuu-Natal v President of the RSA 1999 12 BCLR 1360 (CC), 2000 1 SA 661 (CC)

Executive Council of the Western Cape Legislature v President of the RSA 1995 10 BCLR 1289 (CC), 1995 4 SA 877 (CC)

F v Minister of Safety and Security 2012 3 BCLR 244 (CC), 2012 1 SA 536 (CC)

Fedsure Life Assurance Ltd v Greater Johannesburg Transitional Metropolitan Council 1998 12 BCLR 1458 (CC), 1999 1 SA 374 (CC)

First National Bank t/a v Commissioner SA Revenue Service 2002 7 BCLR 702 (CC) 2002 4 SA 768 (CC)

Fourte v Minister of Home Affairs 2003 10 BCLR 1092 (CC), 2003 3 SA 501 (CC)

Fraser v Naude 1998 11 BCLR 1357 (CC), 1999 1 SA 1 (CC)

Fuel Retailers Association of SA v Director General: Environmental Management 2007 10 BCLR 1059 (CC), 2007 6 SA 4 (CC)

Gcali v MEC for Housing and Local Government, Eastern Cape 2003 11 BCLR 1203 (CC)

Glenister v President of the RSA 2011 7 BCLR 651 (CC), 2011 3 SA 347 (CC)

Grootboom v Government of the RSA 2000 11 BCLR 775 (CC), 2000 4 SA 1078 (CC)

Gundwana v Steko Development CC 2011 8 BCLR 792 (CC), 2011 3 SA 608 (CC

Head Department of Education Limpopo Province v Settlers Agricultural High School 2003 11 BCLR 1212 (CC)

Head of Department: Mpumalanga Department of Education v Hoërskool Ermelo 2010 3 BCLR 177 (CC), 2010 2 SA 415 (CC)

Hlope v Premier of the Western Cape Province; Hlope v Freedom Under the Law 2012 1 BCLR 1 (CC)

Hoffmann v SAA 2000 11 BCLR 1211 (CC), 2001 SA 1 (CC)

In re Constitutionality of the Mpumalanga Petitions Bill 2001 11 BCLR 126 (CC), 2002 1 SA 447 (CC)

In re: KwaZulu-Natal Amakhosi and Iziphakanyiswa Amendment Bill of 1995 1996 7 BCLR 903 (CC), 1996 4 SA 653 (CC)

In re: The National Education Policy Bill No 83 of 1995 1996 4 BCLR 518 (CC), 1996 3 SA 289 (CC)

In re:The School Education Bill of 1995 (Gauteng) 1996 4 BCLR 537 (CC), 1996 3 SA 165 (CC)

Independent Newspapers (Pty) Ltd v Minister for Intelligence Services 2008 8 BCLR

771 (CC), 2008 5 SA 31 (CC)

Institute for Securtty Studies: In re S v Basson 2006 6 SA 195 (CC)

International Trade Administration Commission v SCAW SA (Pty) Ltd 2010 5 BCLR 457 (CC)

Islamic Unity Convention v ICASA 2002 5 BCLR 433 (CC), 2002 4 SA 294 (CC)

Janse van Rensburg v Minister of Trade and Industry 2000 11 BCLR 1235 (CC), 2001 1 SA 29 (CC)

Japhta v Schoeman 2005 1 BCLR 78 (CC), 2005 2 SA 140 (CC)

Joseph v City of Johannesburg 2010 3 BCLR 212 (CC), 2010 4 SA 55 (CC)

Justice Alliance of South Africa v President of RSA, Centre for Applied Legal Studies v President of RSA 2011 5 SA 388 (CC); 2011 10 BCLR 1017 (CC)

K v Mnnsster of Safety and Securtty 2005 9 BCLR 835 (CC), 2005 6 SA 419 (CC)

Key v Attorney-General, Cape of Good Hope Provincial Division 1996 6 BCLR 788 (CC), 1996 4 SA 187 (CC)

Kruger v President of the RSA 2009 3 BCLR 268 (CC), 2009 1 SA 417 (CC)

Larbi-Odam v MEC for Education (North West Province) 1997 12 BCLR 1655 (CC), 1998 1 SA 745 (CC)

Le Roux v Dey 2011 6 BCLR 577 (CC), 2011 3 SA 274 (CC)

Lesapo v North West Agricultural Bank 1999 12 BCLR 1429 (CC), 2000 1 SA 409 (CC)

Levy v Glynos (not reported) CCT 29/00 of 21 November 2000

Liberal Party v Electoral Commission 2004 8 BCLR 810 (CC)

Lufuno Mphaphuli and Associates (Pty) Ltd v Andrews 2009 6 BCLR 527 (CC), 2009 4 SA 529 (CC)

Luitingh v Minister of Defence 1996 4 BCLR 581 (CC), 1996 2 SA 909 (CC)

Mabaso v Law Society of the Northern Province 2005 2 BCLR 129 (CC), 2005 2 SA 117 (CC)

Machete v Mailula 2009 8 BCLR 767 (CC), 2010 2 SA 257 (CC)

Macsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town 2012 7 BCLR 690 (CC), 2012 4 SA 181 (CC)

Magajane v Chairperson, North West Gambling Board 2006 10 BCLR 1133 (CC), 2006 5 SA 250 (CC)

Maphango vAengus Properties (Pty) Ltd 2012 5 BLCR 449 (CC), 2013 3 SA 531 (CC)

Masethla v President of the RSA 2008 1 BCLR 1 (CC)

Mashava v President of the RSA 2005 2 SA 476 (CC), 2004 12 BCLR 1243 (CC)

Masiya v Director of Public Prosecutions Pretoria 2007 8 BCLR 827 (CC), 2007 5 SA 30 (CC)

Matatiele Municipality v President of the RSA (1) 2006 5 BCLR 622 (CC); 2006 (5) SA 47 (CC)

Matatiele Municipality v President of the RSA (2) 2007 1 BCLR 47 (CC)

MEC for Education KwaZulu-Natal v Pillay 2008 2 BCLR 99 (CC), 2008 1 SA 474 (CC)

Merafong Demarcation Forum v President of the RSA 2008 10 BCLR 968 (CC), 2008 5 SA 171 (CC)

Minister of Education v Harris 2001 11 BCLR 1157 (CC), 2001 4 SA 1297 (CC)

Minister of Health v New Clicks SA (Pty) Ltd In re: Application for Declaratory Relief 2006 8 BCLR 872 (CC), 2006 2 SA 311 (CC)

Minister of Health v TAC (1) 2002 10 BCLR 1033 (CC), 2002 5 SA 703 (CC)

Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie 2006 3 BCLR 355 (CC), 2006 1 SA 524 (CC)

Minister of Home Affairs v Liebenberg 2001 11 BCLR 1168 (CC), 2002 1 SA 21 (CC)

Minister of Home Affairs v NICRO 2004 5 BCLR 445 (CC), 2005 3 SA 280 (CC)

Minister of Justice v Ntuli 1997 6 BCLR 677 (CC), 1997 3 SA 772 (CC)

Minister of Safety and Security v Van der Merwe 2011 9 BCLR 961 (CC)

Mkangeli v Joubert 2001 4 BCLR 316 (CC), 2001 2 SA 1191 (CC)

Mkontwana v Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality, Bisset v Buffalo

Municipality, Transfer Rights Action Campaign v MEC for Local Government and Housing Gauteng 2005 2 BCLR 150 (CC), 2005 1 SA 530 (CC)

Mnguni v Minister of Correctional Services 2005 12 BCLR 1187 (CC)

Mohamed v President of the RSA 2001 7 BCLR 685 (CC), 2001 3 SA 893 (CC)

Mohunram v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2007 6 BCLR 575 (CC); 2007 4 SA 222 (CC)

Moloi v Minister for Justice and Constitutional Development 2010 5 BCLR 497 (CC)

Motsepe v Commissioner for Inland Revenue 1997 6 BCLR 692 (CC), 1997 2 SA 898 (CC)

Moutse Demarcation Forum v President of the RSA 2011 11 BCLR 1158 (CC)

Mphela v Haakdoornbult Boerdery CC 2008 7 BCLR 675 (CC), 2008 4 SA 488 (CC)

Mthembu v S 2010 7 BCLR 636 (CC)

Municipality of Plettenberg Bay v Van Dyk & Co Inc 2004 2 BCLR 113 (CC)

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Home Affairs 2001 1 BCLR 39 (CC), 2000 2 SA 1 (CC)

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice 1998 12 BCLR 1517 (CC), 1999 1 SA 6 (CC)

National Director of Public Prosecutions v Mohamed 2002 9 BCLR 970 (CC), 2002 4 SA 843 (CC)

National Police Service Union v Minister of Safety and Securtty 2001 1 BLCR 775 (CC), 2000 4 SA 1110 (CC)

National Treasury v Opposition to Urban Tolling Alliance 2012 11 BCLR 1148 (CC), 2012 6 SA 223 (CC)

Niemand v State 2002 3 BCLR 219 (CC), 2002 1 SA 21 (CC)

Njongt v MEC, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape 2008 6 BCLR 571 (CC), 2008 4 SA 237 (CC)

Occupiers of 51 Olivia Road, Berea Township and 197 Main Street Johannesburg v City of Johannesburg 2008 5 BCLR 475 (CC), 2008 3 SA 208 (CC)

Occupiers of Portion R25 of the Farm Mooiplaats 355JR v Golden Thread Ltd 2012 4 BCLR 372 (CC), 2012 2 SA 337 (CC)

Occupiers of Skurweplaas 353 JR v PPC Aggregate Quarries (Pty) Ltd 2012 4 BCLR 382 (CC)

Pennington v Summerley 1997 10 BCLR 1413 (CC), 1997 4 SA 1076 (CC)

Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of SA. In re: Ex parte Application of the President of the RSA 2003 3 BCLR 241 (CC), 2000 2 SA 674 (CC)

Pheko v Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality 2012 4 BCLR 388 (CC), 2012 2 SA 598 (CC)

Phenithi v Minister of Education 2003 11 BCLR 1217 (CC)

Phillips v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2006 2 BLCR 274 (CC), 2006 1 SA 505 (CC)

Port Elizabeth Municipality v Various Occupiers 2004 12 BCLR 1268 (CC), 2005 1 SA 217 (CC)

Poverty Alliance Network v President of the RSA 2010 6 BCLR 520 (CC)

Premier Kwa-Zulu Natal v President of the RSA 1995 12 BCLR 1561 (CC), 1996 1 SA 769 (CC)

Premier of the Province of the Western Cape v Electoral Commission 1999 11 BCLR 1209 (CC)

Premier: Limpopo Province v Speaker: Limpopo Province 2011 11 BCLR 1181 (CC), 2011 6 SA 396 (CC)

Premier: Limpopo Province v Speaker of the Limpopo Provincial Legislature 2012 6 BCLR 583 (CC), 2012 4 SA 58 (CC)

Premier, Province of Mpumalanga v Executive Committee of the Association of Governing Bodies of State Aided Schools 1999 2 BCLR 151 (CC), 1999 2 SA 91 (CC)

President of the Ordinary Court Martial v Freedom of Expression Institute 1999 11 BCLR 1219 (CC), 1999 4 SA 682 (CC)

President of the RSA v Modderklip Boerdery (Pty) Ltd 2005 8 BCLR 786 (CC), 2005 5 SA 3 (CC)

President of the RSA v SARFU 1999 2 BCLR 175 (CC), 1999 2 SA 14 (CC)

President of the RSA v SARFU 1999 10 BCLR 1059 (CC), 2000 1 SA 1 (CC)

Prince v President of the Law Society of Good Hope 2001 2 BCLR 133 (CC)

Print Media SA v Minister of Home Affairs 2012 12 BCLR 1364 (CC), 2012 6 SA 443 (CC)

Radio Pretoria v Chairperson ICASA 2005 3 BCLR 231 (CC), 2005 4 SA 319 (CC)

Ramakatsa v Magashule 2013 2 BCLR 202 (CC)

Reflect-All 1025 CC v MEC for Public Transport, Roads and Works, Gauteng Provincial Government 2010 1 BCLR 61 (CC), 2009 6 SA 391 (CC)

Rudolph v Commissioner for Inland Revenue 1996 7 BCLR 889 (CC), 1996 4 SA 552 (CC)

S v Basson 2005 12 BCLR 1192 (CC), 2007 3 SA 582 (CC)

S v Bequinot 1996 12 BCLR 1588 (CC), 1997 2 SA 887 (CC)

S v Bierman 2002 10 BCLR 1078 (CC), 2002 5 SA 243 (CC)

S v M 2007 12 BCLR 1312 (CC), 2008 3 SA 232 (CC)

S v Makwanyane 1995 6 BCLR 665 (CC), 1995 3 SA 391 (CC)

S v Mamabolo 2001 3 SA 409 (CC), 2001 5 BCLR 449 (CC)

S v Marais 2010 12 BCLR 1223 (CC), 2011 1 SA 502 (CC)

S v Mello 1998 7 BCLR 908 (CC), 1998 3 SA 712 (CC)

S v Molimi 2008 5 BCLR 451 (CC), 2008 3 SA 608 (CC)

S v Shinga, S v O'Connell 2007 5 BCLR 474 (CC)

S v Shongwe 2003 8 BCLR 858 (CC), 2003 5 SA 276 (CC)

S v State 2001 1 BCLR 52 (CC), 2001 1 SA 1146 (CC)

S v Thunzi 2011 3 BCLR 281 (CC)

S v Van Nell 1998 8 BCLR 943 (CC)

S v Van Rooyen 2002 8 BCLR 810 (CC), 2002 5 SA 246 (CC)

S v Western Areas Ltd 2004 8 BCLR 819 (CC)

SA Asssociation of Personal Injury Lawyers v Heath 2001 1 BCLR 77 (CC), 2001 1 SA 883 (CC)

Satchwell v President of the RSA 2004 1 BCLR 1 (CC), 2003 4 SA 266 (CC)

Schubart Park Residents' Association v City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality 2013 1 BCLR 68 (CC), 2013 1 SA 323 (CC)

Shatk v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2004 4 BCLR 133 (CC), 2004 3 SA 599 (CC)

Sheard v Land and Agricultural Bank of SA, FNB of SA v Land and Agricultural Bank of SA 2000 8 BCLR 876 (CC), 2000 3 SA 626 (CC)

Shilubane v Mwamitwa 2008 9 BCLR 914 (CC), 2009 2 SA 66 (CC)

Shongwe v S 2003 8 BCLR 858 (CC), 2003 5 SA 276 (CC)

Sidumo v Rustenburg Platinum Mines Ltd 2008 2 BCLR 158 (CC), 2008 2 SA 24 (CC)

South African Liquor Traders Association v Chairperson Gauteng Liquor Board 2006 8 BCLR 901 (CC), 2009 1 SA 565 (CC)

Strategic Liquor Services v Mvumbi 2009 10 BCLR 1046 (CC), 2010 2 SA 92 (CC)

Stuttafords Stores (Pty) Ltd v Salt of the Earth Creations (Pty) Ltd 2010 11 BCLR 1134 (CC), 2011 1 SA 267 (CC)

Swartbooi v Brink 2003 1 BCLR 21 (CC), 2003 2 SA 34 (CC)

Transvaal Agricultural Union v Minister of Land Affairs 1996 12 BCLR 1573 (CC), 1997 2 SA 621 (CC)

Tsotetsi v Mutual and Federal Insurance Company Ltd 1996 11 BCLR 1439 (CC), 1997 1 SA 585 (CC)

UDM v President of the RSA (1) 2002 11 BCLR 1179 (CC), 2003 1 SA 495 (CC)

University of Witwatersrand Law Clinic v Minister of Home Affairs 2007 7 BCLR 821 (CC)

Uthukeaa District Municipality v President of the RSA 2002 11 BCLR 1220 (CC), 2003 1 SA 678 (CC)

Van Straaten v President of the RSA 2009 5 BCLR 480 (CC), 2009 3 SA 457 (CC)

Van Vuren v Minister of Correctional Services 2010 12 BCLR 1233 (CC)

Veldman v Director of Public Prosecutions (WLD) 2007 9 BCLR 929 (CC), 2007 3 SA 210 (CC)

Viking Pony Africa Pumps (Pty) Ltd v Hidro-Tech Systems (Pty) Ltd 2011 2 BCLR 207 (CC), 2011 1 SA 327 (CC)

Von Abo v President of the RSA 2009 10 BCLR 1052 (CC), 2009 5 SA 345 (CC)

Walele v City of Cape Town 2008 11 BCLR 1067 (CC), 2008 6 SA 129 (CC)

Wallach v High Court of SA (WLD) 2003 5 SA 273 (CC)

Wallach v Registrar of Deeds (Pretoria), Wallach v Splig 2004 3 BCLR 229 (CC)

Weare v Ndeble 2009 4 BCLR 370 (CC), 2009 1 SA 600 (CC)

Wiese v Government Employees Pension Fund 2012 6 BCLR 599 (CC)

Women's Legal Centre Trust v President of the RSA 2009 6 SA 94 (CC)

Von Abo v President of SA 2009 10 BCLR 1052 (CC), 2009 5 SA 345 (CC)

Xinwa v Volkswagen of SA (Pty) Ltd 2003 6 BCLR 575 (CC), 2003 4 SA 390 (CC)

Zealand v Minister for Justice and Constitutional Development 2008 6 BCLR 601 (CC), 2008 4 SA 458 (CC)

Zondi v MEC for Traditional and Local Government Affairs 2005 4 BCLR 347 (CC), 2005 3 SA 598 (CC)

Register of internet sources

SAFLII 1995-2012 www.saflii.org.za. SAFLII 1995-2013 South Africa: Constitutional Court www.saflii.org.za/za/cases/ZACC/ [date of use 22 May 2013] [ Links ]

List of abbreviations

LQR Law Quarterly Review

SAFLII South African Legal Information Institute

SAJHR South African Journal of Human Rights

TSAR Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg

1 Meydani Israeli Supreme Court 7 in an introduction to a quantitative study of rulings of the Israeli High Court of Justice.

2 As counted on SAFLII 1995-2012 www.saflii.org.za. A few double references appear in this source. In this article a case with multiple references is counted as one case. Only a few of the cases noted were not reported in the Butterworths Constitutional Law Reports or the South African Law Reports. The cases considered per year were: 1995: 14; 1996: 27; 1997: 19; 1998: 21; 1999: 20; 2000: 29; 2001: 25; 2002: 34; 2003: 25; 2004: 22; 2005: 23; 2006: 24; 2007: 27; 2008: 23; 2009: 34; 2010: 27; 2011: 37; 2012: 33.

3 See O'Regan 2012 SAAJHR 122. For statistical analyses of the use of foreign precedents by the Constitutional Court, see Rautenbach Teaching an 'Old Dog' New Tricks?, Rautenbach and Du Plessis 2013 German Law Journal.

4 The refusals per year were: 1995: 0; 1996: 8; 1997: 3; 1998: 6; 1999: 3; 2000: 5; 2001: 7; 2002: 11; 2003: 14; 2004: 6; 2005: 8; 2006: 5; 2007: 5; 2008: 0; 2009: 5; 2010: 8; 2011: 4; 2012: 5.

5 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 200 of 1993 (the interim Constitution).

6 The reasons for the findings on constitutionality are not recorded in this article. Such reasons deal with the substance of court judgments and ultimately with the effect of the judgments on the legal system. A subsequent article will provide an overview of the legal fields affected by the judgments and the impact of the judgments on these fields

7 See Rautenbach General Provisions 122-129; Cachalia et al Fundamental Right 127-131.

8 Sections 98(2) to (g) read with s 101(3)(c), (d) and (e) and 101(6) of the interim Constitution.

9 Section 101(5) of the interim Constitution.

10 Section 102(6) of the interim Constitution.

11 Section 101(6) of the interim Constitution.

12 See Rautenbach General Provisions 131-142.

13 Section 167(4) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution) describes the matters on which only the Constitutional Court has jurisdiction and s 168(3)(a) provides that the Supreme Court of Appeal may decide appeals in any matter arising from the High Court of South Africa, except in respect of labour or competition matters as may be determined by an Act of Parliament.

14 Section 167(4) of the Constitution.

15 Section 169(1) of the Constitution. S 167(1)(a) provides that national legislation and the rules of the Constitutional Court must allow a person, when it is in the interests of justice and with the leave of the Constitutional Court to bring a matter directly to the Constitutional Court.

16 S v Makwanyane 1995 6 BCLR 665 (CC), 1995 3 SA 391 (CC); Rudolph v Commissioner for Inland Revenue 1996 7 BCLR 889 (CC), 1996 4 SA 552 (CC); Fedsure Life Assurance Ltd v Greater Johannesburg Transitional Metropoittan Council 1998 12 BCLR 1458 (CC), 1999 1 SA 374 (CC).

17 The names of the Divisions are the names as they are referred to in cl 50 of the Superior Courts Bill B 7B-2011 (as amended by the Portfolio Committee on Justice and Constitutional Development (National Assembly)) which at the time of the writing of this article had already been approved by the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces.

18 Key v Attorney-General, Cape of Good Hope Provincial Division 1996 6 BCLR 788 (CC), 1996 4 SA 187 (CC).

19 Rudopph v Commissioner for Inland Revenue 1996 7 BCLR 889 (CC), 1996 4 SA 552 (CC); Tsotetsi v Mutual and Federal Insurance Company Ltd 1996 11 BCLR 1439 (CC), 1997 1 SA 585 (CC).

20 Luitingh v Minister of Defence 1996 4 BCLR 581 (CC), 1996 2 SA 909 (CC); Motsepe v Commissioner for Inland Revenue 1997 6 BCLR 692 (CC), 1997 2 SA 898 (CC).

21 S v Bequinot 1996 12 BCLR 1588 (CC), 1997 2 SA 887 (CC).

22 Sections 167(4)(a) to (f) of the Constitution.

23 Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly 2006 12 BCLR 1399 (CC) 1412F-H.

24 Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly 2006 12 BCLR 1399 (CC) 1414-1415.

25 Women's Legal Centre Trust v President of the RSA 2009 6 SA 94 (CC) para 11. In Von Abo v President of SA 2009 10 BCLR 1052 (CC), 2009 5 SA 345 (CC) para 37 reference was made to "certain duties that are pointedly reserved for the President".

26 And the best make-shift solution is probably that s 167(4)(e) should be understood to refer to the obligatory confirmation of findings of other courts in respect of the constitutional invalidity of laws and actions of Parliament and actions of the President - see Rautenbach Constitutional Law 177-178.

27 The cases considered per year were: 1995: 2; 1996: 6; 1997: 2; 1998: 0; 1999: 2; 2000: 0; 2001: 1; 2002: 0; 2003: 0; 2004: 0; 2005 0; 2006: 3; 2007: 0; 2008: 1; 2009: 0; 2010: 1; 2011: 3; 2012: 0.

28 Executive Council of the Western Cape Legislature v President of the RSA 1995 10 bclr 1289 (cc), 1995 4 sa 877 (cc). Premier of the Province of the Western Cape v Electoral Commission 1999 11 bclr 1209 (cc); Executive Council of the Province of the Western Cape v Minister for Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development; Executive Council of KwaZulu-Natal v President of the RSA 1999 12 bclr 1360 (cc), 2000 1 sa 661 (cc).

29 In re Constttutionaitty of the Mpumalanga Petitions Bill, 2000 2001 11 bclr 1126 (cc), 2002 1 sa 447 (cc).

30 In re: The National Education Policy Bill No 83 of 1995 1996 4 bclr 518 (cc), 1996 3 sa 289 (cc); In re:The School Education Bill of1995 (Gauteng) 1996 4 bclr 537 (cc), 1996 3 sa 165 (cc); In re: KwaZuuu-Natal Amakhosi and Iziphakanysswa Amendment Bill of 1995 1996 7 bclr 903 (cc), 1996 4 sa 653 (cc); Premier: Limpopo Province v Speaker: Limpopo Province 2011 11 bclr 1181 (cc), 2011 6 sa 396 (cc).

31 Premier KwaZuuu-Natal v President of the RSA 1995 12 bclr 1561 (cc), 1996 1 sa 769 (cc); Matatiele Municipaitty v President of the RSA (1) 2006 5 bclr 622 (cc); 2006 5 sa 47 (cc); Matatiele Municipality v President of the RSA (2) 2007 1 bclr 47 (cc); Merafong Demarcation Forum v President of the RSA 2008 10 bclr 968 (cc), 2008 5 sa 171 (cc); Poverty Alliance Network v President of the RSA 2010 6 bclr 520 (cc); Moutse Demarcation Forum v President of the RSA 2011 11 bclr 1158 (cc).

32 Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly 2006 12 bclr 1399 (cc), 2006 6 sa 416 (cc).

33 Justice Alliance of South Africa v President of RSA, Centre for Applied Legal Studies v President of RSA 2011 5 sa 388 (cc), 2011 10 bclr 1017 (cc).

34 Certification of the Constitution of Province of KwaZulu-Natal, 1996 1996 11 bclr 1419 (cc), 1996 4 sa 1098 (cc); Certification of the Constitution of the Western Cape, 1997 1997 9 bclr 1167 (cc), 1997 4 sa 1076 (cc); Certification of the Amended Text of Western Cape 1997 1997 12 bclr 1653 (cc), 1998 1 sa 655 (cc).

35 Certification of the Constitution of the RSA, 1996 1996 10 bclr 1253 (cc), 1996 4 sa 744 (cc); Certification of the Amended Text of the Constitution of the RSA, 1996 1997 1 bclr 1 (cc), 1997 2 sa 97 (cc).

36 See also s 172(2)(a) of the Constitution.

37 President of the RSA v SARFU 1999 2 BCLR 175 (CC), 1999 2 SA 14 (CC) para 29.

38 Mkangeli v Joubert 2001 4 BCLR 316 (CC), 2001 2 SA 1191 (CC) para 11.

39 President of the RSA v SARFU 1999 2 BCLR 175 (CC), 1999 2 SA 14 (CC) para 36.

40 The cases considered per year were: 1995: 0; 1996: 0; 1997: 2; 1998: 3; 1999: 5; 2000: 11; 2001: 5; 2002: 8; 2003: 2; 2004: 6; 2005: 3; 2006: 3; 2007: 3; 2008: 5; 2009: 10; 2010: 4; 2011: 2; 2012: 4.

41 Sheard v Land and Agricultural Bank of SA, FNB of SA v Land and Agricultural Bank of SA 2000 8 BCLR 876 (CC), 2000 3 SA 626 (CC); Bhe v Khayelitsha Magistrate, Shibi v Sithole 2005 1 BCLR 1 (CC), 2005 1 SA 580 (CC); Mkontwana v Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality, Bisset v Buffalo Municipality, Transfer Rights Action Campaign v MEC for Local Government and Housing Gauteng 2005 2 BCLR 150 (CC), 2005 1 SA 530 (CC); S v Shinga, S v O'Connell 2007 5 BCLR 474 (CC).

42 See the following 7 footnotes.

43 S v Van Nell 1998 8 BCLR 943 (CC). The invalidation by the Gauteng Division (Pretoria) of the presumption of possession arising from proof that drugs found in the immediate vicinity of an accused was confirmed in S v Mello 1998 7 BCLR 908 (CC), 1998 3 SA 712 (CC).

44 Wiese v Government Employees Pension Fund 2012 6 BCLR 599 (CC); President of the Ordinary Court Martial v Freedom of Expression Institute 1999 11 BCLR 1219 (CC), 1999 4 SA 682 (CC).

45 Uthukela District Municipality v President of the RSA 2002 11 BCLR 1220 (CC), 2003 1 SA 678 (CC) para 12.

46 Mnnsster of Home Affairs v Liebenberg 2001 11 BCLR 1168 (CC), 2002 1 SA 21 (CC).

47 Von Abo v President of the RSA 2009 10 BCLR 1052 (CC), 2009 5 SA 345 (CC).

48 Uthukela District Municipality v President of the RSA 2002 11 BCLR 1220 (CC), 2003 1 SA 678 (CC).

49 National Director of Public Prosecutions v Mohamed 2002 9 BCLR 970 (CC), 2002 4 SA 843 (CC).

50 Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of SA. In re: Ex parte Application of the President of the RSA 2003 3 BCLR 241 (CC), 2000 2 SA 674 (CC) - invalidation of presidential proclamation to bring the South African Medicines and Medical Devices Regulatory Authority Act 132 of 1998 into effect; Mashava v President of the RSA 2004 12 BCLR 1243 (CC), 2005 2 SA 476 (CC) -invalidation of presidential proclamation which assigned the execution of aspects of the Social Assistance Act 59 of 1992 to the provinces; Kruger v President of the RSA 2009 3 BCLR 268 (CC), 2009 1 SA 417 (CC) - invalidation of proclamations to put sections of the Road Accident Amendment Act 19 of 2005 into effect; and Democratic Alliance v President of the RSA 2012 12 BCLR 1261 (CC) - invalidation of appointment by the President of a Director of National Prosecutions.

51 Lesapo v North West Agricultural Bank 1999 12 BCLR 1429 (CC), 2000 1 SA 409 (CC); Ex parte Western Cape Provincial Government: In re DVB Behuising v North West Provincial Government 2000 4 BCLR 147 (CC), 2000 1 SA 500 (CC); Zondi v MEC for Traditional and Local Government Affairs 2005 4 BCLR 347 (CC), 2005 3 SA 598 (CC); South African Liquor Traders Associaion v Chairperson Gauteng Liquor Board2006 8 BCLR 901 (CC), 2009 1 SA 565 (CC).

52 In re Constitutionality of the Mpumalanga Petitions Bill 2001 11 BCLR 126 (CC), 2002 1 SA 447 (CC); Weare v Ndeble 2009 4 BCLR 370 (CC), 2009 1 SA 600 (CC); Reflect-All 1025 CC v MEC for Public Transport, Roads and Works, Gauteng Provincial Government 2010 1 BCLR 61 (CC), 2009 6 SA 391 (CC).

53 F v Minister of Safety and Security 2012 3 BCLR 244 (CC), 2012 1 SA 536 (CC).

54 Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie 2006 3 BCLR 355 (CC), 2006 1 SA 524 (CC).

55 Bhe v Khayetttsha Magistrate; Sibi vStthole 2005 1 BCLR 1 (CC), 2005 1 SA 580 (CC).

56 Shongwe v S2003 8 BCLR 858 (CC), 2003 5 SA 276 (CC) para 4. Geenister v President of the RSA 2011 7 BCLR 651 (CC), 2011 3 SA 347 (CC) para 24.

57 Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie 2006 3 BCLR 355 (CC), 2006 1 SA 524 (CC) paras 40, 44.

58 See eg Christian Education of SA v Minister of Education 1998 12 BCLR 1449 (CC), 1999 2 SA 83 (CC) para 4; Besserglik v Minister of Trade, Industry and Tourism 1996 6 BCLR 745 (CC), 1996 4 SA 331 (CC) para 1; Minister of Home Affairs v NICRO 2004 5 BCLR 445 (CC), 2005 3 SA 280 (CC) para 52.

59 See Dugard 2006 SAJHR 271.