Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versão On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.15 no.2 Potchefstroom Ago. 2012

ARTICLES

A south african perspective on mutual legal assistance and extradition in a globalized world

M Watney

BA Law, LLB, LLM (RAU), LLM (UNISA), Dip E-C Law (TJSL), LLD (RAU). Professor of Law, University of Johannesburg mwatney@uj.ac.za . This article is based on a paper read at the conference on 'Globalisation of Crime - Criminal Justice Responses' presented by the International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law and the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy on 9 August 2011, Ottawa, Canada. The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF), which made this research possible, is hereby acknowledged. All opinions expressed are, however, those of the author D'Oliveira 2003 SACJ 323

SUMMARY

This contribution focuses on the modalities of mutual legal assistance and extradition from a South African perspective. The question is posed whether South Africa has succeeded to establish the required framework as a fully fledged member of the international community to make a positive contribution in the fields of mutual legal assistance and extradition subsequent to its international political isolation during the apartheid era. Although the international community derives substantial benefit from a borderless global world, it has as a result also to deal with the negative impact of globalization on international crime. Physical and/or electronic crimes are increasingly committed across borders and may be described as borderless, but law enforcement (combating, investigation and prosecution of crime) is still very much confined to the borders of a state. Criminal networks have taken advantage of the opportunities resulting from the dramatic changes in world politics, business, technology, communications and the explosion in international travel and effectively utilize these opportunities to avoid and hamper law enforcement investigations. As a sovereign state has control over its own territory it also implies that states should not interfere with each other's domestic affairs. The correct and acceptable procedure would be for a state (requesting state) to apply to another state (requested state) for co-operation in the form of mutual legal assistance regarding the gathering of evidence and/or extradition of the perpetrator. Co-operation between states are governed by public international law between the requesting and requested state and the domestic law of the requested state. The South African legislature has increasingly provided for extraterritorial jurisdiction of South African courts in respect of organized crime and terrorism. It does however appear that existing criminal justice responses are experiencing challenges to meet the demands of sophisticated international criminal conduct. Mutual legal assistance and extradition provisions may show that the world is becoming smaller for fugitives and criminals, but the processes are far from expeditious and seamless. An overview of the South African law pertaining to mutual legal assistance and extradition indicates that the South African legislative framework and policies as well as international treaties make sufficient provision to render international assistance in respect of mutual legal assistance and extradition. The role of the courts in upholding the rule of law and protecting the constitutionally enshrined bill of rights, is indicative of the important function that the judiciary fulfills in this regard. It is important that extradition is not only seen as the function of the executive as it also involves the judiciary. It appears that South Africa has displayed the necessary commitment to normalize its international position since 1994 and to fulfill its obligations in a globalized world by reaching across borders in an attempt to address international criminal conduct.

Keywords: Extradition; mutual legal assistance; international crime; organized crime; bill of rights; criminal justice; extraterritorial jurisdiction; international agreements

1 Introduction

The international community derives substantial benefit from a borderless global world, but as a result also has to deal with the negative impact of globalisation on international crime.1Although physical and/or electronic crimes are increasingly committed across borders and may be described as borderless, law enforcement (the combating, investigation and prosecution of crime) is still very much confined to the borders of a state. Criminal networks have taken advantage of the opportunities resulting from the dramatic changes in world politics, business, technology, communications and the explosion in international travel, and effectively utilise these opportunities to avoid and hamper law enforcement investigations.2The transnational involvement of organised syndicates is characterised by the detailed planning of operations, substantial financial support and massive profits, which makes it difficult to police and prosecute.3

Internationally the following crimes and/or conduct pose a particular challenge:

-

physical crimes committed across borders, such as drug trafficking, human trafficking, money laundering, environmental crime and terrorism;

-

electronic (cyber) crimes committed within one state but the effect of which is felt in the territory of another state or in multiple states, such as the release of malware; and

-

the flight of a person accused of or sentenced for a physical or electronic crime from the state in which this took place to another state.

It is generally accepted that once a crime has been committed, it should be investigated, the perpetrator should stand trial and on conviction be punished for his unlawful conduct. The challenge that arises is how this could be ensured where the perpetrator is outside the borders of the state in which the crime was committed or where the effect of the crime was felt.

The need for effective international and transnational criminal justice has to be balanced with respect for state sovereignty and territorial integrity.4Law enforcers of one state cannot enter the territory of another state and kidnap the perpetrator, nor can they enter its territorial space and collect evidence of the crime, as this would in itself be a violation of international law. Such conduct would not only infringe the sovereignty of a state but also violate the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of another state.5Public international law governs the conduct of states in their relationships with each other. The fact that a sovereign state has control over its own territory also implies that states should not interfere with one another's domestic affairs. The correct and acceptable procedure would be for a state (the requesting state) to apply to another state (the requested state) for co-operation in the form of mutual legal assistance regarding the gathering of evidence and/or the extradition of the perpetrator. Co-operation between states is governed by public international law between the requesting and requested state and the domestic law of the requested state.6

In theory most countries provide on international and domestic level for international co-operation. A distinction is drawn between primary and secondary forms of co-operation.7Primary co-operation includes the seizure of property and other forms of enforcement as well as co-operation that requires a state to take over part of the procedure of the other state. The effective enforcement of money-laundering provisions would require primary forms of co-operation. Secondary co-operation does not involve the transfer of procedural responsibility. Assistance with an investigation and the extradition of fugitives are regarded as secondary co-operation. The primary and secondary forms of co-operation are divided into the following six different modalities of co-operation:8(i) extradition; (ii) mutual legal assistance; (iii) the transfer of criminal proceedings; (iv) the transfer of prisoners; (v) the seizure and forfeiture of assets; and (vi) the recognition of foreign criminal judgments.

This contribution will focus on the modalities of mutual legal assistance and extradition from a South African perspective. The question is asked if South Africa has succeeded in establishing the required framework as a fully fledged member of the international community to make a positive contribution in the fields of mutual legal assistance and extradition subsequent to its international political isolation during the apartheid era.

2 Mutual legal assistance

The International Co-operation in Criminal Matters Act9(the ICCM) inter alia aims to facilitate the provision of evidence, the execution of sentences in criminal cases, and the confiscation and transfer of the proceeds of crime between South Africa and foreign states.10The ICCM regulates the law in respect of mutual legal assistance.11

The ICCM provides for South Africa as the requesting state to issue a letter of request to a foreign state (the requested state) for the taking of evidence in such a state in respect of criminal proceedings pending before a court in South Africa, or to obtain information in respect of a criminal investigation.12

A reciprocal provision allows for a foreign state (the requesting state) to request South Africa (the requested state) for assistance in obtaining evidence in South Africa.13In Thatcher v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development14Sir Mark Thatcher, the son of the former British prime minister, unsuccessfully challenged a subpoena issued in terms of section 8(2) of the ICCM on the basis of a request from the government of Equatorial Guinea to South Africa to render it assistance by compelling Thatcher to respond to questions relating to his alleged involvement in a failed coup d'état in that country. The court rejected arguments that compelling Thatcher to answer questions would infringe upon his right to silence or have a prejudicial effect on any extradition proceedings against him. At the point in time when the subpoena was issued, Thatcher was on bail in South Africa relating to charges of financing the coup attempt in contravention of the Regulation of Foreign Military Assistance Act.15

The ICCM also provides for reciprocal assistance in the enforcement of orders arising from criminal proceedings.16These would include assistance in the recovery of fines and compensatory orders17and the enforcement of confiscation18and restraint orders.19

In the matter of Falk v NDPP20Falk was arrested in Germany in June 2003 on charges inter alia of themanipulation of the share price of a German corporation by misrepresentations, with a view to obtaining unlawful gain, to the prejudice of third parties who purchased shares in the corporation. In terms of an order issued by the Hamburg regional court in August 2004, the attachment of assets in Falk's estate to the value of Є31 635 413.34 was authorised to secure that amount in the eventuality of the first appellant being convicted and the court ordering forfeiture of the amount specified. The German authorities requested assistance from South Africa in enforcing the order. South Africa obliged and the foreign restraint order was registered in the Western Cape High Court in terms of the provisions of section 24 ICCM.21Falk was convicted22at the conclusion of his trial and sentenced to four years imprisonment but the court refused to grant a forfeiture order against him. Both the prosecution and Falk noted appeals. As the noting of the appeal against the order of the German Regional Court automatically suspended its operation, Falk applied unsuccessfully to the High Court in South Africa for the setting aside of the registration of the foreign restraint order and the interdict. On appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal, the court found that section 25 ICCM does not convert a foreign restraint order into an order of a South African High Court. It therefore remains a foreign order and not all of the provisions of chapter 5 of the Prevention of Organised Crime Actapply to it. The court concluded that section 26 ICCM finds application and that if an appeal is pending in a foreign court against the refusal of a confiscation order, a South African court hearing an application for the setting aside of the registration of the foreign restraint order might have regard to section 26(2) ICCM and postpone the hearing until the fate of the appeal in the foreign court becomes known.23

Evaluated from a procedural point of view, it is submitted that the mutual legal assistance measures adopted by South Africa have succeeded in making its legal processes available to the international community.

3 Extradition

3.1 Introduction

The Extradition Act24regulates South Africa's extradition procedure. Although existing agreements were retained, the country's international political isolation prevented any large-scale extension of extradition agreements. The new democratic dispensation brought this to an end and in 1996 South Africa became a party to the Commonwealth Scheme for the Rendition of Fugitive Offenders.25The number of extradition treaties has since escalated and South Africa is currently in a position to fulfill its international obligations in respect of extradition.

Extradition is defined as the physical surrender by one state (the requested state), at the request of another state (the requesting state), of a person who is either accused or convicted of a crime by the requesting state.26

Kemp points out that extradition has traditionally been treated as an aspect of international relations.27As a result of this approach, emphasis was placed on the role of the executive rather than that of the judiciary or other role players in the criminal justice system. He provides two convincing reasons, however, why the emphasis should be on the procedural process rather than on an executive-centred approach:28

(i) human rights and due process are best protected when viewed as an extension of the criminal justice system rather than as a matter of international relations; and

(ii) the aim of extradition should be effective criminal justice (with the concomitant requirements of due process and human rights protection) rather than inter-state relations.

In President of the Republic of South Africa v Quagliani29the South African Constitutional Court pronounced on the nature of extradition, recognising that it involved more than international relations or reciprocity:

It involves three elements: acts of sovereignty on the part of two States; a request by one State to another State for the delivery to it of an alleged criminal; and the delivery of the person requested for the purposes of trial and sentencing in the territory of the requesting State. Extradition law thus straddles the divide between State sovereignty and comity between States and functions at the intersection of domestic law and international law.30

Having established the nature of extradition, the applicable procedure becomes relevant.

3.2 Procedure for extradition

The extradition process (the request and surrender) is governed by international and domestic law. A general duty on the part of states to surrender criminals does not exist in customary international law.31States rely on extradition conventions, specialist crime suppression conventions, general schemes such as the Commonwealth Scheme for the Rendition of Fugitive Offenders of 1990 or even upon their domestic legislation as a legal base for extradition.32Absent a treaty there might be no duty to extradite, but a state may be required to surrender the requested person or to punish him under its own laws. This is known by the maximautdedere aut judicare(extradition or trial) and the modern trend has been to exercise this principle with regard to international crimes.33

The requested state may surrender the requested individual only after there has been compliance with

(i) an extradition agreement between the requesting and requested state; and

(ii) the domestic laws of the requested state34

The extradition agreement between the requested state and the requesting state determines the offences in respect of which the extradition is possible and the circumstances in which extradition may be refused, whereas the domestic law as outlined in legislation prescribes the procedure to be followed in extradition proceedings and some of the circumstances in which extradition may be refused.35

As indicated, an extradition agreement has an international and domestic component and both of these components must be satisfied before effect may be given to the international treaty. Requests to South Africa are made by either:

(i) associated states which are neighbouring states in Africa, which have concluded extradition agreements with South Africa; or

(ii) foreign states.

A more simplified and expeditious procedure is followed in respect of extradition requests from the associated states.36

Foreign states are divided into three groups:

(i) States with which South Africa has an extradition agreement. South Africa has entered into a number of extradition agreements with countries such as Canada, Australia and the United States of America. In 2003 South Africa also acceded to the multilateral European Convention on Extradition of 1957 and in so doing became a party to an extradition agreement with a further 50 states;

(ii) States designated by the president in terms of s 2(1)(b) read with s 3(3) of the act. The president has designated the following states namely Ireland, Namibia, Zimbabwe and the United Kingdom;37

(iii) States in respect of which the president has consented to the surrender of the fugitive.38

The minister of justice receives the extradition request from a foreign state via diplomatic channels.39The minister will then issue a notification to a magistrate who in turn will issue a warrant of arrest.40The arrest and detention are aimed at conducting an extradition enquiry.41An extradition enquiry is regarded as a judicial and not an administrative proceeding.42Extradition proceedings nevertheless remain sui generis in nature and can therefore not be described as criminal proceedings.43There is an important differentiation between judicial and executive roles in extradition proceedings.44Although a magistrate fulfills an important screening role to determine whether or not there is sufficient evidence to warrant prosecution in the foreign state,45the decision to extradite a person is ultimately an executive one.46The pivotal role of the executive in extradition proceedings has been criticised.47

Section 14 of the act provides that an order for extradition may not be executed before the period allowed for an appeal (15 days) has expired, unless the right to appeal has been waived in writing or before such an appeal has been disposed of.

3.3 Return of fugitives by means other than extradition

3.3.1 Disguised extradition and unlawful deportation

"Disguised extradition" occurs when a fugitive is deported to a state in which he is accused of a crime, in terms of deportation procedures. The practice is condemned as it deprives a person of the rights he would have enjoyed during the extradition process.48

In Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening)49the facts presented as a disguised extradition. Mohamed, a Tanzanian national, fled to South Africa after his involvement in the 1998 bombing of the US embassy in Dar-es-Salaam. He entered South Africa on a false passport and under an assumed name. He applied for asylum giving false information in support of his application and was issued with a temporary visa to facilitate his presence in the country pending his application. Mohamed's presence was discovered by the FBI in 1999 and after negotiations with the South African police and immigration authorities he was declared a prohibited person and deported to the US where he was indicted in New York on various charges relating to the bombing of the US embassy.50He risked receiving the death penalty on conviction. This procedure was followed despite the existence of an extradition agreement between South Africa and the US. Another suspect51was extradited from Germany to the US after Germany sought and secured an assurance from the US that upon conviction he would not receive the death sentence.52

The Constitutional Court held that the deportation53of Mohamed violated both the Aliens Control Act54and the Constitution. The constitutional infringement focused on the failure by the South African government to obtain a prior undertaking by the US government that upon conviction the death penalty would not be imposed.55This infringed Mohamed's rights to human dignity, to life, and not to be punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading manner.56The Constitutional Court concluded that the handing over of Mohamed to the US government was unlawful and issued the following warning:

That is a serious finding. South Africa is a young democracy still finding its way to full compliance with the values and ideals enshrined in the Constitution. It is therefore important that the State lead by example. This principle cannot be put better than in the celebrated words of Justice Brandeis in Olmstead et al v United States:57

"In a government of laws, existence of the government will be imperilled if it fails to observe the law scrupulously.... Government is the potent, omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example.... If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for the law; it invites every man to become a law unto himself; it invites anarchy."

The warning was given in a distant era but remains as cogent as ever. Indeed, for us in this country, it has a particular relevance: we saw in the past what happens when the State bends the law to its own ends and now, in the new era of constitutionality, we may be tempted to use questionable measures in the war against crime. The lesson becomes particularly important when dealing with those who aim to destroy the system of government through law by means of organised violence. The legitimacy of the constitutional order is undermined rather than reinforced when the State acts unlawfully. Here South African government agents acted inconsistently with the Constitution in handing over Mohamed without an assurance that he would not be executed and in relying on consent obtained from a person who was not fully aware of his rights and was moreover deprived of the benefit of legal advice. They also acted inconsistently with statute in unduly accelerating deportation and then despatching Mohamed to a country to which they were not authorised to send him.58

The decision is a clear indication of the high premium placed by the Constitutional Court on the protection of the fundamental rights59contained in the Bill of Rights.60Dugard indicates that if a person has been irregularly deported to South Africa in a "disguised extradition", a South African court should refuse to exercise jurisdiction.61

3.3.2 Kidnapping

The kidnapping of a person from a state by agents of another state to stand trial in the latter state is a violation of the territorial integrity of the former.62The injured state is entitled to demand the return of the kidnapped person and request the extradition of the kidnappers for trial purposes. It has been recommended that the most effective way to discourage such territorial violations would be for the courts of the abducting state to refuse to exercise jurisdiction over the kidnapped person.63

In S v Ebrahim64the South African Appellate Division held that a South African court has no competence to try a person kidnapped from another state by agents of South Africa.65The court relied on the Roman-Dutch law in stating that the rule prohibiting the exercise of jurisdiction over a kidnapped person was premised on considerations of good inter-state relations, respect for territorial sovereignty, and the promotion of human rights.66

The Supreme Court of the United States, however, decided in United States v Alvarez-Machain67that the forcible kidnapping of a Mexican national from Mexico by US law-enforcement agents did not serve as a bar to his trial in the US.68

In Bennet v Horseferry Road Magistrates' Court69the House of Lords relied on the Ebrahimcase in decidingthat it would decline to exercise jurisdiction over an arrested person, as the manner in which his presence was secured amounted to an abuse of the process of the court.70The following remark by Lord Bridge is of importance:

There is, I think, no principle more basic to any proper system of law than the maintenance of the rule of law itself. When it is shown that the law enforcement agency responsible for bringing a prosecution has only been enabled to do so by participating in violations of international law and of the laws of another state in order to secure the presence of the accused within the territorial jurisdiction of the court, I think that respect for the rule of law demands that the court take cognisance of that circumstance. To hold that the court may turn a blind eye to executive lawlessness beyond the frontiers of its own jurisdiction is, to my mind, an insular and unacceptable view.71

3.4 Factors that may obstruct extradition

An extradition agreement between the requesting and requested state and domestic laws of the requested state may provide for the following:

3.4.1 Extradition of nationals

An extradition agreement may provide that a state will not extradite its own nationals. Common law countries do not exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction and will allow the extradition of their nationals, unlike civil law countries, for example. The nationality exception to extradition is a matter of domestic law and not a generally recognised rule of international law.72

Where a state refuses to extradite its own nationals, it has been suggested that a requesting state may urge the requested state to surrender its nationals on the basis that they will, subsequent to conviction, be repatriated for sentencing and the serving of the sentence. This approach would recognise the territorial state for trial and the home state for punishment and rehabilitation.73Regard should also be given to the use of the aut dedere aut judicareprinciple of either extraditing the perpetrator or establishing jurisdiction.

Note should be taken of the McKinnon matter in this regard.74This case has resulted in much debate in the UK regarding the US-UK treaty obligations of 2003 as well as the European Arrest Warrant. In 2005 the US government requested the UK to surrender a UK citizen, Gary McKinnon, to stand trial in the US. McKinnon had allegedly hacked into 97 US military and NASA computers over a 13 month period between February 2001 and March 2002, using the name Solo. He is accused of hacking into various computer networks, including those networks owned by NASA, the US Army, the US Navy, the Department of Defense and the US Air Force. The US authorities claim he deleted critical files from operating systems, which shut down the US Army's Military district of Washington network of 2 000 computers for 24 hours and also deleted US Navy Weapons logs, rendering naval bases' network of 300 computers inoperable after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. McKinnon is also accused of copying data, account files and passwords onto his own computer. US authorities claim the cost of tracking and correcting the problems he caused was over $700 000. McKinnon has denied causing any damage, arguing that, in his quest for UFO-related material, he accessed open unsecured systems with no passwords and no firewalls and that he left countless notes pointing out their many security failings. He disputes the damage and the financial loss claimed by the US as concocted in order to create a dollar amount justifying an extraditable offence.

As at date75McKinnon, who refuses to surrender voluntarily to the US, has not yet been extradited. This may affect the UK's diplomatic relations with the US. In terms of the Extradition Act of 2003 US authorities requesting the surrender of a UK citizen need to show only that the perpetrator is suspected of a crime committed in the US and provide an accurate description of the suspect. On the other hand if the UK requests the extradition of a US citizen, it would have to show evidence that the US citizen has committed the crime. McKinnon has argued that he should stand trial in the UK. It could be argued that the UK has jurisdiction to prosecute the perpetrator since the crime of hacking was committed within the territory of the UK although the effect was felt in the US. This case study renders credence to the expression of "justice delayed is justice denied."

The McKinnon matter can be compared with that of Brian Roach, a South African citizen, who in 2011 threatened to unleash foot-and-mouth disease on British livestock in a biological terror attack unless he was paid $4 million.76Roach also threatened to launch a similar attack on the US. It is alleged that the perpetrator intended to use the funds to compensate farmers who had been forced off their properties in Zimbabwe by that government's controversial programme of land reclamation. No extradition request was received and Roach was prosecuted in South Africa.77

3.4.2 Double criminality

The principle of double criminality requires that the crime for which extradition is requested should also be a crime in the requested state.

Although it was a common practice in the past to list the extraditable offences, the tendency today is for the parties to provide for extradition in respect of extraditable crimes that are punishable in both the requesting state and the requested state with a sentence above a particular severity, without naming the crime.78South Africa's domestic law provides for extradition of persons accused of crimes which are punishable with a sentence of imprisonment or another form of deprivation of liberty for a period of six months or more.79

The South African domestic extradition law does not indicate whether the extraditable crime should be a crime in South Africa at the time of the extradition request or at the time the alleged offence was committed, but it has been suggested that it should be an extraditable crime at the time of the request.80The latter suggestion is purposed to circumvent a situation similar to that which came about in the Pinochet Case,81where extradition was refused because the conduct for which extradition was requested had not been a crime in the UK at the time of its commission.

3.4.3 Principle of speciality

According to the principle of speciality the extradited person may not be tried for an offence other than the crime for which he was extradited. This is a common clause in extradition agreements. The South African domestic extradition law also contains this principle.82In S v Stokes83the appellant, after his extradition by the US to South Africa, was served with an indictment in terms of which he was charged with theft (count 1) and three counts of fraud, alternatively theft (counts 2, 3 and 4) committed before his extradition. He objected in terms of section 19 of the Extradition Act on the basis that he might not be charged with these offences in that they were not the offences in respect of which his extradition was sought. The appellant succeeded in the court a quo in respect of counts 3 and 4. On appeal against the finding that he had to stand trial on counts 1 and 2, the Supreme Court of Appeal found that the US was advised that the appellant was sought in respect of the offences of theft of money as stated in the application for provisional arrest. No indication was given that the appellant was being sought in respect of misrepresentations having been made by him. The court therefore concluded that as the appellant's extradition was sought for the offences of theft and not fraud, he should stand trial on count 1 (theft) and the alternative charge of theft in respect of count 2.84

3.4.4 Non bis in idem

Most extradition agreements provide that a person cannot be extradited for an offence of which he was already convicted or acquitted by the requested state. The South African domestic extradition law does not contain this principle, but the person to be extradited may refer to a previous conviction or a previous acquittal as an objection to extradition.85

3.4.5 Offences of a political nature

Most extradition agreements contain a political offence exception to extradition.86The political offence exception has been controversial as courts try to define a political offence in such a way that it excludes the political terrorist.87The South African domestic extradition law provides for a political offence exception which excludes terrorist activity.88

Here one should take note of the matter of former Czech Republic citizen, Radovan Krejcir. Krecjir fled the Czech Republic in 2005, moved to Seychelles where he obtained citizenship, and settled in South Africa in 2005. He was sentenced in absentia to 6 years imprisonment for fraud by a Prague court in the Czech Republic. The Czech Republic has requested South Africa to extradite him to serve his sentence. Krecjir has in the meantime obtained temporary refugee status in South Africa and has applied for asylum. He has, however, also been arrested and charged for insurance fraud in South Africa. South Africa has not as yet extradited him to the Czech Republic, but it is debatable whether he should have been granted temporary refugee status at all, taking into account that he had been convicted of fraud in the Czech Republic.

3.4.6 Application of human right norms as an objection to extradition

Human rights impact on extradition. Most states, including South Africa, are party to international human rights conventions.

Some extradition agreements provide for the application of human rights norms, but even those extradition agreements that do not provide for such application may refuse extradition on the grounds of human rights. The two principle human rights norms in many extradition treaties provide for the non-imposition of the death penalty and non-discrimination.89

It is important that the extradited person will have a fair trial. The South African domestic extradition law provides that a person will not be extradited if the extradited person will be prejudiced at his or her trial in the requesting state by reason of his or her gender, race, religion nationality or political opinion.90

The Shrien Dewani matter is noteworthy in this regard. In November 2010, while UK citizen Dewani and his wife Anni were on honeymoon in Cape Town, South Africa, Anni was shot and killed during a hi-jacking. Dewani soon thereafter left South Africa with the permission of the South African law enforcement agency. It was later alleged during the sentencing of one of the perpetrators involved in the hijacking that Dewani had arranged for the killing of his wife. The motive for the killing is unknown, although unproven allegations have been made to the effect that it was a forced marriage which did not carry Dewani's approval and withdrawal from the marriage would have resulted in his being disowned by his family. Dewani was arrested in the UK and released on bail pending an extradition application. He denied involvement in the killing of his wife and alleged that on being extradited to South Africa his human rights would be infringed as he would be in danger of gang-related sexual violence in prison. The application by the South African government for Dewani's extradition, however, was successful.91

Another case study is that of a Swiss national, Klaar, who 11 years after his conviction of rape was extradited in January 2011 from New Zealand to South Africa to serve his sentence of 6 years imprisonment, which had been imposed in December 1998. He was arrested on 14 December 2009, and after a lengthy extradition process a court in New Zealand found that Klaar should be extradited to serve his sentence. Justice in this instance was eventually served after 11 years.

3.4.7 Incorporation of the extradition agreement between requested and requesting state into the domestic law of the requested state

On an international level an extradition treaty between South Africa and another state can be validly entered into only in accordance with the provisions of section 2(1) of the Extradition Act read with section 231(1) and 231(2) of the Constitution. Section 231(1) provides that the negotiation and signing of all international agreements is the responsibility of the national executive and section 231(2) of the Constitution states that an international agreement binds South Africa internationally after it has been approved by resolution in both the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces. Incorporation of the treaty into domestic law is governed by section 231(4) of the Constitution. Section 231(4) states that an international treaty becomes law when it is enacted into law by national legislation but a self-executing provision of an agreement that has been approved by parliament is law in the Republic unless it is inconsistent with the Constitutionor an act of parliament.92If the extradition agreement is not validly incorporated into the domestic law effect cannot be given, despite the extradition agreement's being valid on international level.

4 Conclusion

In a globalised world the commission of cross-border crimes such as human trafficking, terrorism, drug trafficking and environmental crimes are bound to increase, especially where a legal system does not provide sufficiently for extradition. Criminals will exploit deficiencies in a legal system to their own advantage. Countries without safeguards against such exploitation may become havens for fugitive criminals. This is one of the reasons why attention is increasingly being given to extraterritorial jurisdiction, to prevent criminals from escaping justice.

The South African legislature is increasingly providing for extraterritorial jurisdiction of South African courts in respect of organised crime and terrorism.93It does, however, appear that existing criminal justice responses are experiencing challenges to meet the demands of sophisticated international criminal conduct. Mutual legal assistance and extradition provisions may show that the world is becoming smaller for fugitives and criminals, but the processes are far from expeditious and seamless. An overview of the South African law pertaining to mutual legal assistance and extradition indicates that the South African legislative framework and policies as well as international treaties make sufficient provision to render international assistance in respect of mutual legal assistance and extradition. The role of the courts in upholding the rule of law in the extradition cases referred to and protecting the constitutionally enshrined Bill of Rights is indicative of the important function that the judiciary fulfills in this regard. It is important that extradition is seen not only as the function of the executive, as it also involves the judiciary. Extradition requests may therefore result in the requesting country's legal system being scrutinised by the requested country. Although 17 years is a short time in a country's history, it appears that South Africa has displayed the necessary commitment to normalising its international position since 1994, and to fulfilling its obligations in a globalised world by reaching across borders in an attempt to address international criminal conduct. To what extent this will contribute to addressing the international phenomenon of organised crime remains to be seen.

Bibliography

Boister N "The trend to 'universal extradition' over subsidiary universal jurisdiction in the suppression of transnational crime" 2003 Acta Juridica 287-313 [ Links ]

Cachalia A "Counter-terrorism and international cooperation against terrorism - an elusive goal: a South African perspective" 2010 SAJHR510-535 [ Links ]

D'Oliveira J "International co-operation in criminal matters: the South African contribution" 2003 SACJ 323-369 [ Links ]

Dugard J International Law - A South African Perspective 4thed (Juta Cape Town 2011) [ Links ]

Du Plessis M "The Pinochet cases and South African extradition law" 2000 SAJHR 669-689 [ Links ]

Du Plessis M "The extra-territorial application of the South African Constitution" 2003 SALJ 797-819 [ Links ]

Du Plessis M "The Thatcher case and the supposed delicacies of foreign affairs: a plea for a principled (and realistic) approach to the duty of government to ensure that South Africans abroad are not exposed to the death penalty" 2007 SACJ 143-153 [ Links ]

Du Toit E et al Commentary on the Criminal Procedure Act(Juta Cape Town 2011) [ Links ]

International Law AssociationReport of the 68thConference of the International Law Association, Taipei, Taiwan ( Republic of China), 24-30 May 1998 (ILA London1998) [ Links ]

Katz A "The incorporation of extradition agreements" 2003 SACJ 311-322 [ Links ]

Kemp GP "Foreign relations, international cooperation in criminal matters and the position of the individual" 2003 SACJ 370-392 [ Links ]

Kemp GP "Mutual legal assistance in criminal matters and the risk of abuse of process: a human rights perspective" 2006 SALJ 730-743 [ Links ]

Proust K "International co-operation: a Commonwealth perspective" 2003 SACJ 295-310 [ Links ]

Register of legislation

Aliens Control Act 96 of 1991

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996

Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

Extradition Act 67 of 1962

International Co-operation in Criminal Matters Act 75 of 1996

Prevention of Organised Crime Act 121 of 1998

Protection of Constitutional Democracy against Terrorist and Related Activities Act 33 of 2004

Regulation of Foreign Military Assistance Act 15 of 1998

Register of court cases

South African case law

Beheermaatschappij Helling I NV v Magistrate, Cape Town 2007 1 SACR 99 (C)

Falk v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2011 1 All SA 354 (SCA)

Falk v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2011 ZACC 26

Geuking v President of the Republic of South Africa 2001 2 SACR 490 (C)

Harksen v President of the Republic of South Africa 2000 2 SA 825 (CC)

In re Reuters Group plc v Viljoen 2001 12 BCLR 1265 (C)

Jeebhai v Minister of Home Affairs 2009 5 SA 54 (SCA)

Minister of Justice v Additional Magistrate, Cape Town 2001 2 SACR 49 (C)

Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC)

President of the Republic of South Africa v Quagliani 2009 2 SA 466 (CC)

S v Beahan 1992 1 SACR 307 (ZS)

S v Ebrahim 1991 2 SA 553 (A)

S v Roach(Unreported case no RC 158/2011, Alexandra Regional Court, 23 Jun 2011)

S v Stokes 2008 2 SACR 307 (SCA)

Thatcher v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2005 4 SA 543 (C)

Thint Holdings (Southern Africa) (Pty) Ltd v National Director of Public Prosecutions; Zuma v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2009 1 SA 141 (CC)

Tsebe v Minister of Home Affairs; Pitsoe v Minister of Home Affairs 2012 1 BCLR 77 (GSJ)

Foreign case law

Bennet v Horseferry Road Magistrates' Court 1993 3 All ER 138 (HL)

Minister of Justice v Burns 2001 SCC 7

Olmstead et al v United States 277 US 438 (1928) 485

R v Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate; Ex Parte Pinochet Ugarte (No 3)1999 2 All ER 97 (H)

The Government of South Africa v Shrien Dewani (Unreported case, City of Westminster Magistrates' Court, sitting at Belmarsh Magistrates' Court, 10 Aug 2011)

United States v Alvarez-Machain 1992 31 ILM 900

Register of international instruments

United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (2000)

Register of internet sources

Greenhill 2012 www.dailymail.co.uk [ Links ]

Greenhill S 2012 ''We just want the truth': Agony of murdered Anni Dewani's family after her husband's extradition to South Africa is temporarily halted on mental health grounds' Daily Mail Online 30 March 2012 www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2122643/Shrien-Dewani-extradition-halted-mental-health-grounds.html [date of use 10 April 2012] [ Links ]

Interpol 2011 www.interpol.int [ Links ]

Interpol 2011 Environmental Crime www.interpol.int/public/environmental crime/default.asp [date of use 28 June 2011] [ Links ]

Maclean 2011 www.telegraph.co.uk [ Links ]

Maclean S 2011 'South African farmer threatened biological terror attack on UK' The Telegraph 14 February 2011 www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/southafrica/8323274/South-African-farmer-threatened-biological-terror-attack-on-UK.html [date of use 19 April 2011] [ Links ]

UNODC 2011 www.unodc.org [ Links ]

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2011 What does environmental crime have in common with organised crime? www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/ [date of use 28 June 2011] [ Links ]

Whitehead, Porter and Hope 2010 www.telegraph.co.uk [ Links ]

Whitehead T, Porter A and Hope C 2010 'New powers to block Britons from extradition' The Telegraph 6 September 2010 www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/7985764/New-powers-to-block-Britons-from-extradition.html[date of use 16 April 2011] [ Links ]

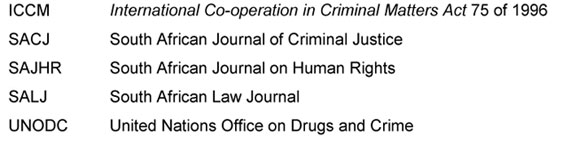

List of abbreviations

1 D'Oliveira 2003 SACJ 323.

2 Boister 2003 Acta Juridica 287.

3 UNODC 2011 www.unodc.org; Interpol 2011 www.interpol.int.

4 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B2. The United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (2000) requires state parties to "carry out their various obligations in a manner consistent with the principle of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of states". Also see Kemp 2003 SACJ 373.

5 Proust 2003 SACJ 295-296.

6 Katz 2003 SACJ 311.

7 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B2.

8 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B2.

9 International Co-operation in Criminal Matters Act 75 of 1996. The ICCM should be read with the Prevention of Organised Crime Act 121 of 1998, which aims to suppress racketeering, the financing of terrorism, and money laundering in South Africa and abroad. Also see Dugard International Law 239.

10 The ICCM further aims to enable South Africa to become a party to various international treaties on mutual legal assistance (s 27). For example, South Africa entered into mutual legal assistance treaties in terms of the ICCM with Egypt (2004), the People's Republic of China (2005) and France (2005).

11 See In re Reuters Group plc v Viljoen 2001 12 BCLR 1265 (C) para 36. D'Oliveira 2003 SACJ 346 argues that the ICCM does not comprehensively regulate mutual legal assistance law. S 31 ICCM provides that nothing contained in the act shall be construed so as to prevent or abrogate or derogate from any arrangement or practice for the provision or obtaining of international co-operation in criminal matters otherwise than in the manner provided in the act. D'Oliveira 2003 SACJ 347 indicates that South Africa has therefore "... aligned itself with the international injunction to afford other jurisdictions 'the widest measure of mutual legal assistance in investigations, prosecutions and judicial proceedings relating to criminal offences.'"

12 Section 2 ICCM. See Thint Holdings (Southern Africa) (Pty) Ltd v National Director of Public Prosecutions; Zuma v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2009 1 SA 141 (CC).

13 Section 7 ICCM. See Beheermaatskappij Helling I NV v Magistrate, Cape Town 2007 1 SACR 99 (C) for an interpretation of s 7 and the application thereof.

14 Thatcher v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2005 4 SA 543 (C). For criticism of the decision, see Du Plessis 2007 SACJ 143.

15 Regulation of Foreign Military Assistance Act 15 of 1998. Thatcher later pleaded guilty to the charge ito this act in a plea and sentence agreement and was sentenced to a five year suspended prison sentence and a fine of R3 million. He was allowed to leave the country. See Kemp 2006 SALJ 730, 734.

16 No provision is made, however, for the execution of foreign prison sentences in South Africa.

17 Section 13 ICCM.

18 Section 19 ICCM.

19 Section 23 ICCM.

20 Falk v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2011 1 All SA 354 (SCA).

21 As a result Falk was interdicted by the High Court at the request of the National Director of Public Prosecutions from dealing in any way with his shares in a company (FRS) held in trust by an attorney in Cape Town, from dealing with the sum of Є5,22 million held in a South African bank account and from dealing, except in the ordinary course of business, with any of the other assets of the company (para 4).

22 He was convicted of conspiracy to attempt to commit fraud, conspiracy to misrepresent the financial position of a corporation, and misstating the information pertaining to a corporation in its annual financial statements (paras 12-16).

23 Falk's further appeal to the South African Constitutional Court was also unsuccessful (see Falk v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2011 ZACC 26).

24 Extradiction Act 67 of 1962.

25 Dugard International Law 215.

26 Proust 2003 SACJ 296; also see Katz 2003 SACJ 311; Dugard International Law 214; Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B15.

27 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B15.

28 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B15.

29 President of the Republic of South Africa v Quagliani 2009 2 SA 466 (CC).

30 President of the Republic of South Africa v Quagliani 2009 2 SA 466 (CC) para 1.

31 Boister 2003 Acta Juridica 296; Proust 2003 SACJ 297; Dugard International Law 214.

32 Boister 2003 Acta Juridica 296; Proust 2003 SACJ 297.

33 Katz 2003 SACJ 311.

34 Harksen v President of the Republic of South Africa 2000 2 SA 825 (CC) para 4.

35 Dugard International Law 218. Ss 2 and 3 of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962 provide for the entering into extradition agreements and the ratification thereof by parliament and for the extradition of individuals ito agreements (either ito treaties or ad hoc agreements). These provisions should be read with s 231(2) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 which provides for the entering into agreements between South Africa and foreign states.

36 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B17. In terms of s 12(1) of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962 a magistrate shall, if he finds the person liable to be surrendered to the associated state, issue an order for his surrender to the associated state. This order is appealable within 15 days to the high court. S 12(2) empowers a magistrate to order that a person may not be surrendered. The grounds specified are the same as those contained in s 11(b) applicable to the executive in foreign state applications (see n 46).

37 South Africa signed the Commonwealth Scheme relating to the Rendition of Fugitive Offenders of 1990 in 1996, which allows extradition to a designated country without the need for an extradition agreement. The Scheme is not a multilateral treaty but an agreed guideline of principles, which form the basis of reciprocating legislation enacted in Commonwealth states. It is not a binding international agreement.

38 See Harksen v President of the Republic of South Africa 2000 2 SA 825 (CC) para 6.

39 S 4 of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962.

40 S 5 Extradition Act. In President of the Republic of South Africa v Quagliani 2009 2 SA 466 (CC) the arrests were carried out ito the extradition agreement between South Africa and the US, which provides for so-called "provisional arrest" in urgent cases of a person sought, pending presentation of the documents in support of the extradition request. It appears from the judgment of the Constitutional Court that the court regarded the "provisional arrests" to be lawful arrests in terms of s 40(1)(k) of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 and s 9 of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962. See Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B17-18 and Katz 2003 SACJ 321 for criticism of the "provisional arrest" provision contained in some extradition treaties. They argue that as neither the Criminal Procedure Act nor the Extradition Act provide for "provisional arrests", extradition treaties should be formulated to accord with the procedures in existing South African legislation or alternatively, that legislation should be amended to provide for "provisional arrests". The argument is premised on the notion that extradition agreements are not self-executing and that any procedures flowing from the agreements should be ito the law of South Africa.

41 S 9 of the Extradition Act sets out the procedure applicable to the enquiry.

42 Minister of Justice v Additional Magistrate, Cape Town 2001 2 SACR 49 (C) 61c.

43 In Minister of Justice v Additional Magistrate, Cape Town 2001 2 SACR 49 (C) the court described the difference between a criminal case and an extradition enquiry as follows: "In a criminal matter, the lis between the State and the accused is whether or not he or she is guilty of the crime of which he or she is accused. The cardinal question in an extradition enquiry under ss 9 and 10 ... is whether, in the case where the person whose extradition has been requested is accused of an offence committed in a foreign state, there is sufficient evidence to warrant a prosecution for the offence in the state concerned" (62a-b) and "The fact that ... a Director of Public Prosecutions ..., or a public prosecutor, may appear at an enquiry, does not make the State a party to the proceedings" (62f).

44 The phases were set out as follows in Geuking v President of the Republic of South Africa 2001 2 SACR 490 (C) 496 H-I: "It is a process with two distinct phases: the first, the judicial phase, encompasses the court proceedings which determine whether a factual or legal basis for extradition exists; in the second phase, the Minister exercises his or her discretion whether or not to surrender the person concerned to the requesting State. The first phase is judicial in its nature and warrants the application of the full panoply of procedural safeguards; the second phase is political in nature."

45 S 10(1) Extradition Act provides that if a magistrate finds a person liable to be surrendered to the foreign state, he shall issue an order committing such a person to prison to await the minister's decision with regard to his surrender. He also has to inform the person that he may within 15 days appeal such an order to the high court. If the magistrate finds that the evidence does not warrant the issue of an order of committal or that the necessary evidence is not forthcoming within a reasonable time, he shall discharge the person. See Tsebe v Minister of Home Affairs; Pitsoe v Minister of Home Affairs 2012 1 BCLR 77 (GSJ) para 69.4.

46 S 11 Extradition Act authorises the minister to order the surrender of a person committed in terms of s 10, to the foreign state. The minister may also order that the person shall not be surrendered (i) until pending criminal proceedings against the person in South Africa have been finalised or until imprisonment imposed in terms of such proceedings has been served; (ii) until the person has served a current term of imprisonment; (iii) at all, or after the lapse of a period, due to the trivial nature of the offence or by reason of the surrender not being required in good faith or in the interests of justice or its being unjust or unreasonable or too severe a punishment to surrender the person; or (iv) if he is satisfied that the person will be prosecuted or punished or prejudiced at his trial in the foreign state by reason of his / her gender, race, religion, nationality or political opinion.

47 International Law Association Report of the 68th Conference suggested that extradition legislation should be amended to provide for the protection of individuals. It was proposed that proceedings should be treated as criminal proceedings and individuals thus be entitled to minimum standards of fairness and due process. See Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B18.

48 Dugard International Law 231.

49 Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC).

50 A US grand jury concluded that the attacks on the two embassies were the work of Al Qaeda in its ongoing international campaign of terror against the US and its allies. The grand jury later indicted 15 men (including Mohamed) on a total of 267 counts, including conspiracy to murder, kidnap, bomb and maim US nationals; conspiracy to destroy US buildings, property and national defence facilities; bombing the two embassies and the murder of the 223 persons killed.

51 Mahmoud Mahmud Salim.

52 Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC) para 41-43.

53 The court pointed to the following clear distinction between extradition and deportation: "Extradition involves basically three elements: acts of sovereignty on the part of two States; a request by one State to another State for the delivery to it of an alleged criminal; and the delivery of the person requested for the purposes of trial or sentence in the territory of the requesting State. Deportation is essentially a unilateral act of the deporting State in order to get rid of an undesired alien. The purpose of deportation is achieved when such alien leaves the deporting State's territory; the destination of the deportee is irrelevant to the purpose of deportation. One of the important distinguishing features between extradition and deportation is therefore the purpose of the state delivery act in question" (Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC) para 27). Also see Jeebhai v Minister of Home Affairs 2009 5 SA 54 (SCA).

54 Aliens Control Act 96 of 1991. This act permits deportation only to a country of which the person is a national.

55 The Constitutional Court referred to the decision by the Supreme Court of Canada in Minister of Justice v Burns 2001 SCC 7 where the court held that there is an obligation on the Canadian government, in the absence of exceptional circumstances, before extraditing a suspect to seek an assurance from the receiving State that the death penalty will not be imposed (Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC) para 45).

56 Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC) para 73.

57 Olmstead et al v United States 277 US 438 (1928) 485.

58 Mohamed v President of the Republic of South Africa (Society for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in South Africa Intervening) 2001 3 SA 893 (CC) para 68.

59 Du Plessis 2003 SALJ 805 argues for extending the Mohamed principle to include not only violations of the right to life but any real risk of sufficiently serious harm relating to a fundamental value protected in the Constitution.

60 The court ordered that its judgment be delivered to the trial court in New York. Mohamed was convicted but not sentenced to death.

61 Dugard International Law 233.

62 Dugard International Law 233.

63 Dugard International Law 234.

64 S v Ebrahim 1991 2 SA 553 (A).

65 S v Ebrahim 1991 2 SA 553 (A) 579F-G. As a result the Appellate Division set aside the conviction of treason and the sentence of 20 years imprisonment imposed by the trial court on Ebrahim, who was kidnapped from Swaziland.

66 S v Ebrahim 1991 2 SA 553 (A) 579G; 582C-E. This approach was followed by the Supreme Court of Zimbabwe in S v Beahan 1992 1 SACR 307 (ZS) where the court stated that "(t)here is an inherent objection to such a course both on grounds of public policy pertaining to international ethical norms and because it imperils and corrodes the peaceful coexistence and mutual respect of sovereign nations. For abduction is illegal under international law, provided the abductor was not acting on his own initiative and without the authority and connivance of his government. A contrary view would amount to a declaration that the end justifies the means, thereby encouraging States to become law-breakers in order to secure the conviction of a private individual" (S v Beahan 1992 1 SACR 307 (ZS) 317D-F).

67 United States v Alvarez-Machain 1992 31 ILM 900.

68 The dissenting opinion of the court relied inter alia on S v Ebrahim 1991 2 SA 553 (A).

69 Bennet v Horseferry Road Magistrates' Court 1993 3 All ER 138 (HL).

70 A New Zealand national who committed fraud in the UK was arrested in South Africa and forcibly returned to the UK under the pretext of deporting him to New Zealand via the UK. This procedure was followed as there existed no extradition agreement between South Africa and the UK.

71 Bennet v Horseferry Road Magistrates' Court 1993 3 All ER 138 (HL) 155F-I.

72 Boister 2003 Acta Juridica 299.

73 Boister 2003 Acta Juridica 299-300.

74 Whitehead, Porter and Hope 2010 www.telegraph.co.uk.

75 January 2012.

76 See Maclean 2011 www.telegraph.co.uk.

77 A plea and sentence agreement was concluded in terms of s 105A of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 and the Alexandra Regional Court, Randburg sentenced Roach to an effective five years imprisonment on 23 June 2011 (S v Roach (Unreported case no RC 158/2011, Alexandra Regional Court, 23 Jun 2011). Ito the agreement, Roach (64) was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment (seven years suspended) for attempted extortion. An additional five years imprisonment was imposed for money laundering and was ordered to run concurrently with three years imprisonment imposed for the illegal possession of ammunition. Roach was also declared unfit to possess a firearm. The terrorism charge against him was withdrawn because a political motive could not be established.

78 Proust 2003 SACJ 301; Dugard International Law 219.

79 Section 1 of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962 defines extraditable offence as "... any offence which in terms of the law of the Republic and of the foreign state concerned is punishable with a sentence of imprisonment or other form of deprivation of liberty for a period of six months or more, but excluding any offence under military law which is not also an offence under the ordinary criminal law of the Republic and of such foreign state".

80 Dugard International Law 220.

81 R v Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate; Ex Parte Pinochet Ugarte (No 3) 1999 2 All ER 97 (H). See Du Plessis 2000 SAJHR 669.

82 Section 2(3)(c) read with s 19 Extradition Act 67 of 1962.

83 S v Stokes 2008 2 SACR 307 (SCA).

84 S v Stokes 2008 2 SACR 307 (SCA).para 11-18.

85 Dugard International Law 221.

86 Section 15 of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962 provides that the minister may at any time order the cancellation of a warrant for the arrest of a person issued ito the act or discharge from custody a person detained ito the act if he is satisfied that the offence iro which the surrender of the person is sought is an offence of a political nature.

87 Dugard International Law 221-222.

88 Section 22 of the act qualifies s 15 by stipulating that a request for extradition based on the offences referred to in s 4 or 5 of the Protection of Constitutional Democracy against Terrorist and Related Activities Act 33 of 2004 may not be refused on the sole ground that it concerns a political offence. Ss 4 and 5 of Act 33 of 2004 concern offences associated with the financing of terrorist offences and offences relating to explosives or other lethal devices. The preamble to Act 33 of 2004 recognises that part of the reason for the promulgation of the act relates to United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373/2001, which requires member states to become party to instruments dealing with terrorist and related activities, and that South Africa is mindful to carry out its obligations ito the international instruments dealing with terrorist and related activities. Also see Cachalia 2010 SAJHR 510.

89 Dugard International Law 226. In Tsebe v Minister of Home Affairs; Pitsoe v Minister of Home Affairs 2012 1 BCLR 77 (GSJ) the court held that failure by the South African authorities to attain an assurance that the sentence of death would not be imposed constituted an absolute bar to extradition to a country where the death penalty could be imposed (Tsebe v Minister of Home Affairs; Pitsoe v Minister of Home Affairs 2012 1 BCLR 77 (GSJ) para 92).

90 Sections 11(b)(iv) and 12(2)(ii) of the Extradition Act 67 of 1962.

91 The Government of South Africa v Shrien Dewani (Unreported case, City of Westminster Magistrates' Court, sitting at Belmarsh Magistrates' Court, 10 Aug 2011). Dewani's appeal against the extradition order to the High Court was dismissed on 30 March 2012. The High Court, however, temporarily halted his extradition to South Africa on the grounds that it would worsen his mental health condition and make it more difficult to get him into a position where he was fit to plead. The court found that it would be in the interests of justice to facilitate his recovery so that the trial could proceed sooner rather than later (Greenhill 2012 www.dailymail.co.uk).

92 Katz 2003 SACJ 315-321.

93 Kemp in Du Toit et al Commentary App B39.