Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

versión On-line ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.14 no.3 Potchefstroom jun. 2011

ARTICLES

Urban pro-poor registrations: complex-simple the overstrand project

L Downie

BA LLB (UP), BA Hons (English) (UNISA). Legal consultant (low cost housing registrations for the poor and low-literate / corporate social responsibility); previously an attorney, notary and conveyancer (leslie@downieconsult.co.za)

SUMMARY

Low-cost housing which has been disposed of by private owners is extremely difficult for conveyancers to register. The law as it stands is often incapable of giving effect to the business transactions of the poor, thereby creating insecurity of tenure nationwide. The Land Titles Adjustment Act 111 of 1993 is currently the only legislation capable of dealing with this impasse. The Overstrand Municipality has provided the staff and infrastructure to run a pilot project under the Act, for which it is awaiting confirmation from the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. This article discusses the legal issues arising and the potential of such an initiative to provide consumer protection for the low-literate and other vulnerable holders of rights.

Keywords: Security of tenure; deeds registration; alienation of land; pro poor registrations; customary marriages; consumer protection; low cost housing

1 Contextualisation1

The painting "Complex-Simple" came into being in 1939, from the brush of the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky, just prior to World War ll. Kandinsky is known for having taken up one of the intellectual preoccupations of his time, namely the idea that there is a secret correspondence among the arts, particularly between the otherwise disparate arts of music and painting, colours and sounds. He grappled with what he called the "inner necessity" of the urge to create and how to illustrate the idea that artistic activity resonates across the boundaries of colour and sounds. By 1939 his skill as an artist was fully realised, but it is his formative years that are of interest to a jurist.

In the biographical section of his book on Kandinsky, Benedikt Taschen writes that in 1886 Kandinsky decided to study law and economics. He then comments:

Perhaps he chose these dry, academic fields of study to counterbalance his inner, unresolved tensions, or perhaps to flee from the troubling, unassimilated visions of his inner world.2

He goes on to add:

In his free time he continued to occupy himself with painting and nature's 'chorus of colours', which still confronted him with insoluble problems. Jurisprudence, which trained his sense for abstract relationships, was far easier.3

Taschen entitles his book A Revolution in Painting. This is an appropriate title for a book about a man whose secret "inner necessity" lived alongside a physical, outer world which produced the 1917 Russian Revolution and two World Wars. If one wishes to understand Kandinsky, it is helpful to know such facts that in 1889 he was sent by the Society for Natural Science, Ethnography and Anthropology to the province of Vologda to record, amongst other things, the local "peasant" laws. These were the decades just prior to the most profound shift in economic, legal and political thinking seen in the twentieth century. The way the poor understood what should be the spirit of the law, as opposed to the prevailing letter of the law, would have been amongst the "easier" abstract relationships for the thinking lawyers of the time.

The complex-simple problems arising out of the interface between the "art" of the social sciences and the "art" of the law are inescapable in present-day urban South Africa, and as inescapable as the social and political forces that shaped Kandinsky's internal landscape. The right to housing is one of the most volatile areas of law in our country. The transfer of ownership is a key part of the housing dilemma, as is an understanding of the social issues which make low-cost property registration so difficult to achieve. Once the first transfer of a state-subsidised house is registered, the property is privately owned and - subject to the provincial housing department's eight-year pre-emption right - the owner may legally dispose of it.4 For the beneficiaries of a state-subsidised house, the registration of ownership will result in their first exposure to the capital of privately owned immovable property. It is the problems raised by the "not-so-free" market of these disposals about which this article must attempt to speak.5

Any conveyancer who works with registrations of transfer of ownership from the poor to the poor will know that such clients present with problems far more complex than most R5 000 000 transactions on her desk. The R5 000 000 file will typically be a medium-sized file and will be finalised in approximately two months. A R17 000 transaction, on the other hand, may well be a file oozing out of its cover and can take a year or two to register - if it is registered at all. This is not merely a problem of the poor not having access to justice due to poverty. It is the consequence of a legal system which becomes dysfunctional when applied in the context of the poor. If the beauty of simplicity within complexity is to be found in the field of pro-poor registrations, alternative ways of thinking must be explored. This paper will not include an exposition of Kandinsky's research into what was termed "peasant" law in his day. It will merely give a legal practitioner's insights into why, at the threshold of the twenty-first century, if the system does not adapt, conveyancers of low-value properties might be well advised to turn to a career in painting.

Background questions

Once the primary issues have been discussed, a brief outline will be given of the partially completed pro-poor registration projects of the Overstrand Municipality, whose municipal area stretches from Rooi Els to Betty's Bay, Kleinmond, Hermanus, Stanford and beyond Gansbaai. As I am the project leader of these projects, the approach taken to formulating the models has not been that of an academic, but that of a previous conveyancer and legal practitioner with an outcomes-based emphasis. Nevertheless, the issues which arise in these projects are very diverse, including issues relating to many other fields and considerable quantities of legal theory.

It has taken four years to bring the systems to their present point and it is still uncertain whether or not the necessary consents to bring them to fruition will be obtained. The abstract relationships of jurisprudence which have been subliminally present throughout have been far from easy to establish. Whether the projects proceed or not, it is important to make various observations and record what has been learned. Before moving to the practical side, certain issues must be raised, as further input from better equipped minds is necessary. It is against this backdrop that the conveyancing insights must be weighed.

Four questions have crystallised during the formulation of the Overstrand Municipality projects. These questions are the following:

•Are jurists prudent to approach the registration of ownership of the urban immovable property of the poor in a manner which does not take cognizance of the social sciences which study the actual disposal practices of the poor?

• Is the urban tenure security debate focussing on the dysfunctional registration of transfer of ownership to the poor, when it should be focussing on the dysfunctional management of the risks inherent in disposing of immovable property by means of an informal transaction?6

• Is the loss of respect for the rule of law linked to the existence of laws which make the business practices commonly used by the poor unlawful?

• Is the refusal of the legal system to recognise the disposal practices of the poor, (such that extra-legal informal transactions are their only option) resulting in a stifling of their free market economy? If so, is it the law itself which is preventing the poor from working their own way out of poverty?7

The primary text to which a conveyancer must apply her mind is the text of her client's personal legal history. Theoretical studies relating to tenure security seldom make their way to a conveyancer's desk, as there is only so much a legal practitioner has time to research and the South African law changes daily. The broader theory this paper seeks to raise is therefore not from the perspective of a directly academic discipline, nor does it take the approach of a statistics-based local government report. It is nevertheless worth putting the thinking of a conveyancer on the dissecting table, as conveyancers are the professionals who drive the property registration system.8

3 Client case studies

An outlinoses of privacy, full names and details are not provided: e of the factual circumstances of two sets of claimants will illustrate most succinctly the types of challenges which face a conveyancer who deals with pro-poor registrations. For purp

Client C

The registered owners are A and B. The property was registered in 2003. The property was sold to C and recorded by means of an affidavit in 2008. The affidavit was completed at the police station and signed only by seller A and not his coowner, B. It does not record all of the details of the sale. Purchaser C was married in community of property to D at the time of the purchase, but D's name was not included in the affidavit recording the purchase. Seller A took the purchase money and returned to the province of his birth. The whereabouts of both seller A and wife B is unknown. The purchaser C has been paying the rates ever since.

Client F

The registered owner is DX. A sale agreement was entered into between the state and DX in 2002, selling the property to DX as the purchaser. Subsidised housing is disposed of by the state by means of a sale to the housing beneficiary. Prior to registration of transfer of ownership of the property from the seller (who was the state) to DX (who was the purchaser), the property was sold by a relative of DX, namely EX, to the second generation purchaser F. An affidavit to this effect was written up by EX and signed by him before a commissioner of oaths in 2004, but there is no further written proof of the sale. The property was not offered to the state in terms of the pre-emption right of section 10A of the Housing Act,9 which was recorded in the original sale agreement. The purchase price was paid to seller DX in accordance with the affidavit. Transfer of ownership to the original purchaser DX was registered from the state in the name of DX in 2007. DX is known to have been in an unregistered African customary marriage throughout. Owner DX is now deceased and his customary wife has returned to a rural area and cannot be contacted. The relative EX may or may not be able to be contacted. F has since the date of the second generation sale been in possession of the property.

4 A conveyancer's priorities

The conveyancer faced with the above scenarios must know which issues to prioritise, if she wishes to act in the best interests of her clients.10 Some further background is required in order for the legal issues inherent in the case studies to be understood. These sales are second-or third-generation sales of low-cost housing, the cost of which was initially subsidised by the state. The properties are therefore privately owned and are generally valued at under R30 000. In such attorney-client interactions it is almost always the purchaser who presents himself or herself as the client, as the money has already changed hands. It is not unusual for the clients to arrive at the attorney's offices with two or three other people, of whom only one or two will be sufficiently confident to be able to take the consultation forward in English or Afrikaans. The interpreters will not necessarily be the purchasers themselves. A proper explanation of how the law will function, in a manner which will be understood by the parties, is often impossible.

Studies have shown that overheads in an attorney's firm range from between 60% and 70% of gross income.11 The cost of resolving a client's problems is therefore the first question that a conveyancer must consider. While a certain amount of pro bono work can and must be undertaken, files such as these are so complex legally that no practitioner will be able to give free advice to more than a few pro bono clients in any given year. If that limit has already been reached, the conveyancer will have to ask for some advance cover for her fees. Hearing this request it is likely that the clients and their assistants will confer and decide whether they can proceed or whether their attempt to obtain registration is futile. While the language spoken is likely to be foreign to the conveyancer, the tone of the discussion will be unmistakeable. A preliminary amount of R500 may be produced, perhaps from the safekeeping of the bra of one of the women.

Much rides on the back of the decision to accept the deposit of that money into the attorney's own place of "safekeeping", namely the firm's trust account. The amount of R500 is not even sufficient to cover the necessary disbursements and further advances will need to be called for as time passes. The dilemma is whether to turn the clients away or attempt to find some affordable shortcut to assist them. For those few conveyancers who are willing to accept the work, it will often result in the conveyancer being taken to the edge of an abyss.12 This abyss is that of a legal system that does not recognise a large proportion of the business transactions of the poor pertaining to the disposal of low-cost immovable property.

Conveyancers are service providers in terms of the Consumer Protection Act13 to be promulgated shortly. Theirs is therefore the duty to provide owners of low-value property with services that ameliorate the disadvantages of low literacy and low income, as referred to in section 3(1) of the Act. They will be expected in terms of the Act to function within a responsible legal framework.

5 The costs of the conveyancing process

Affordability is central to whether or not a deeds registries system is sustainable for properties owned by the poor.14 Private transfers of privately owned low-cost housing use the same registration system as a R5 000 000 property. The second transfer of a house bought for less than R20 000 would cost R4 100 under the current conveyancers' tariff, with an additional amount if the sale agreement needs to be redrawn. In the majority of instances the affluent purchaser will arrive with a sale agreement which has been drawn up for free by an estate agent who has some basic legal training in terms of the Estate Agents Act.15 A poor purchaser, on the other hand, will most probably have to pay for the drafting of a legally compliant sale agreement which will cost about R500 if the issues are simple. These fees apply where there is no dispute as to ownership, status or loss of documents, and no intervening transaction, after which the costs escalate exponentially as a court order, preceded by lengthy evidence, is necessary.

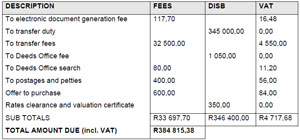

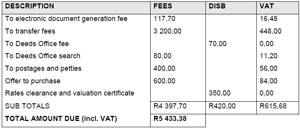

Conveyancers always draft key figures in both words and numbers so that readers will not mistake their meaning. The conveyancing cost for the transfer of a R5 000 000 (five million rand) property to an individual costs R39 815 being 0,79% (approximately comma eight percent) of the value of the property. Even if the R345 000 transfer duty is added to the cost of the R5 000 000 transfer, the costs represent only 7,7% (approximately eight percent) of the value of the property. The conveyancing cost for a property valued at R20 000 (twenty thousand rand) is R5 433, being 27% (twenty-seven percent) of the value. No transfer duty is payable on transfers valued under R500 000. A R20 000 transfer file is often considerably more complex legally than a R5 000 000 transaction.16

Since the costs are the primary barrier to effecting registration, the Overstrand Municipality's projects attempt to offer a solution to reducing these costs to sustainable levels. Nevertheless, even if the Overstrand models prove to be workable, alternative approaches to the steps necessary for the registration process need to be considered. If the vesting of the rights of the poor by commissioners' awards and court orders is likely to take place at scale, the potential of other more accessible forms of recording that make use of cell-phone technology should be given serious consideration.17

6 Causae for transfer and the transfer or titling process

It is important for this debate to distinguish between the two steps underlying the acquisition of immovable property and the conveyancing process. The first step is determining if there is in fact a lawful causa (such as an agreement of sale in the case of a sale) upon which transfer can be registered, and the second is the facilitation of such registration of ownership at the deeds registry coupled with the so-called "real agreement". A causa is the cause or reason for the transfer. If the knot of dysfunctional registration processes for the poor is to be untied it is critical that these two steps are handled separately. For the first step, a conveyancer must refer to the causa setting out the reason for transfer in order to prepare a deed of transfer which will be accepted by the Deeds Office.18

The question of the advisability of the South African registration system moving to a system of registration of titling, rather than registration of deeds, is currently under discussion. In a positive registration system, bona fide third parties who rely on the deeds register have a greater degree of legal certainty, but this makes the position of the original holders of real rights more uncertain.19 The risk of the original holders of real rights as opposed to the risk of bona fide third parties shifts according to which approach is favoured.20 For low-cost housing transfers the current system, while problematic, is nevertheless far more protective of the transactions of the poor than titling would be. Such a shift to titling need not, however, result in a loss of rights for the poor provided that there is a simultaneous shift whereby their rights vest primarily by means of court orders rather than on registration of title. The attribution of greater importance to the first or second step of the conveyancing process is integral to which emphasis the registration construct will choose to favour. Risk is the central issue here. The law and interpretative theory discussed below may seem trite to legal academics, but it is relevant insofar as assessment of risk is an attorney's stock-in-trade.21

Litigation attorneys specialise in winning battles where holders of rights take their disputes to court. Commercial attorneys specialise in pre-empting their clients being taken to court by drawing competent contracts, wills, cessions, bond documents, sureties, leases and the like. Conveyancers are commercial attorneys, but every transfer file is a potential litigation file if the conveyancer misreads the causa for transfer. The worry of a professional negligence claim is a great spur to focus the mind of a lawyer with the usual small profit margin and inadequate insurance. Accordingly, one of a conveyancer's first responses to his client's story will be to assess the causa with caution, as that part of the file that could come back to bite him. The high risks in taking on a strong adversary with access to legal expertise are not unknown to the conveyancer. In this sense a conveyancer straddles the litigation and the commercial divide, thereby also straddling the divide between the two sides of the conveyancing process.

Conveyancers grapple daily with the need to make legal assessments regarding original right holders and subsequent right holders. Therefore it is worth spelling out how a conveyancer is told about the transactions upon which the poor perceive their rights to ownership to be based. In this grey area lies the chasm between the presence or absence of the right to transfer ownership. The poor's understanding of a causa, or reason for transfer, is often entirely different from the classical legal system's understanding of what is lawful. They are regularly completely unable to effect registration of title due to faulty causae. If there is any chance that this will result in a reduction of their rights, should there be a shift to a registration of title rather than a registration of deeds approach, this must be very seriously considered. More importantly, if there is any chance that this will result in a perception of a reduction of their rights, this too is a risk which must be approached with the utmost caution.

7 Hear the other side

The simplest and most foundational concept of natural justice is the audi alteram partem rule, but for the legal practitioner the first challenge is to listen to his own client before taking the next step of listening to his opponent.22 The legal phrase is commonly translated by jurists as "hear the other side". A plain language translation (which takes cognizance of the "invisibility" of the poor) could express this concept simply by saying that a client has the right to ask the justice system to "see me". If the problem of pro-poor registrations is to be resolved, it is incumbent upon the legal profession to "hear the other side" of the poor.

The inequities which arise from a failure of the classical law to "see" the transactions of those disadvantaged by poverty must be thought through as a matter of urgency. This is true both of evictions of the poor by the poor and of disposals of ownership. It is necessary for jurists to embark on Gulliver's23 travels and feel the dangers and anger in this microcosm which is populated by the dragons of poverty, ill health, social insecurity and the continuous change caused by dire uncertainty. The obvious must be stated. When the poor enter into a sale agreement that does not comply with the Alienation of Land Act,24 they are not doing so to annoy the affluent in civil society. They are doing so because their lives are lived with all of the elements of a grand tragedy. It is the only solution they regard as being available to them.

8 Absence and presence in the conveyancer's check list

When a conveyancer is presented with the problems referred to in the case studies above, long before he moves to the facilitation of the registration process his brain must light up in areas as sophisticated and varied as Kandinsky's "Complex-Simple". In thinking through the Overstrand project, the methodology of reader response theory and some poststructuralist interpretative strategies have been used by the author in an attempt to identify the issues.25 With the rise in the popularity of the linguistic turn in the field of interpretation of statutes, a background in literary theory is extremely helpful to understanding the processes of the attribution of meaning in law.

The legal system functions as a text in terms of which there is an interplay between legal textbooks, statutory texts, case law texts, customary texts (from a largely verbal tradition), the "text" of the client's legal story, and the "text" of the jurist's own educational conditioning and worldview.26 In order to fully understand the implications of a text it is often best to apply a reading theory which assists the reader to see not only what is present, but also the gaps in the text.27 This trains the interpreter to see what is being marginalised by the text and what is being promoted. For this reason, something that is absent is often referred to as present. The "presence" of absence is for the literary theorist often an indicator of a political power struggle, with what is "present" in the text reflecting the dominant party, and what is "absent" reflecting the marginalised party.28 The phraseology of presence and absence is somewhat pretentious, but it is used below in order to highlight the fact that the business transactions of the poor are in fact "present" and the legal fraternity needs to "see" this, instead of interpreting their factual context and arrangements negatively as something that is "absent". The reader is asked to exercise patience with the inelegant wording of the paragraphs below. It is necessary in order to ensure that the concept is grasped.

With the two sample clients C and F above, there are at least eight legal issues which arise. They are discussed in detail below in order that the complexity of such files may be understood.

8.1 Law of property

The first thing that will colour the conveyancer's thinking will be when he hears of the presence of an agreement to sell, but notes the absence of a sale agreement that complies with the Alienation of Land Act.29 This will appear in various shades, as he mentally ticks off whether all the parties have signed, whether spouses have given their consent, whether the property was determinable, the extent of written as opposed to verbal arrangements and the availability of formal status documents. This will make him see the presence of an informal causa and the absence of a legal sale causa for a transfer.30 While affidavits can be used as proof of identity, there is great risk to conveyancers in using them as opposed to valid identity documents, as he accepts full responsibility for having verified such information when he signs the preparation certificate of a deed.31 In terms of this function, the conveyancer stands at the coalface of dealing with incorrect status documentation and is the person who has to bear the risk of any mistakes.

8.2 Law of succession

The second matter that will colour his thinking will be when he hears about the "presence" of the absence of a reportable estate.32 This will appear in various shades as he hears about the presence of an arrangement as to who will inherit, but the absence of a valid will,33 the "presence" of the absence of sufficient information to wind up the estate as an intestate estate,34 the presence of claiming heirs but the absence of certainty as to living relatives and the "presence" of the absence of some of the necessary identity and marriage documents. The presence of a family member acting as an informal executor and signing the sale affidavit will be noted. No estate transfer can take place without the estate being reported and wound up. This will make him see the presence of an informal causa and the absence of a legal causa for an estate transfer. It is the conveyancer's duty to confirm the authorisation of agents acting on behalf of parties and he is the person who has to bear the risk of an unauthorised transfer such as in the case of the family member above.35 He will also see that even if the causae can be regarded as lawful, two transfers are necessary, namely firstly to the deceased estate and secondly from the estate to the purchaser, thereby doubling the costs.

8.3 African customary law

The third matter that will colour his thinking will be as he hears about the presence of a relative transacting and the absence of the deceased owner and the female coowner. In the instance of an unregistered customary marriage, he will also hear the dissonance between the importance of the role of men in proving that the unregistered customary marriage has in fact taken place, and the refusal to recognise the transactions of the selfsame men in a dispute over the same property. This will make him see the presence of an informal causa and the absence of a legal causa for the unregistered customary spouse in terms of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act.36

For the sake of accuracy it must be added that, while customary law has now been recognised by the Constitution as having the same status as common law,37 for practitioners African customary law is the Cinderella of the legal disciplines. There are very few conveyancers of urban property who know much about it. Customary law is a highly specialised field and not one that is easily dabbled in. Very large law firms would include a practitioner with this expertise and they would be expected to share their knowledge with the other practitioners when necessary. However, many law firms would not have such expertise on hand. Neither would they have a textbook dedicated to African customary law, unless they had young practitioners whose curriculum included the subject and who brought their university textbooks with them. In other words many practitioners would rely on a chapter in a broader textbook, particularly on a matter such as marital status. Such books emanate either from academia, which ought to have its own internal mechanisms for the responsible and cost-efficient sharing of expertise, or from members of the legal profession.38 All text books dealing with marital status should include material on customary marriages to ensure that the need to protect these rights is more widely known. Law students registered for legal subjects, whether from the legal or other faculties, are expected to cover the basics of such matters and African customary marriages must be given appropriate coverage.

8.4 Law of persons

The fourth matter that will colour the conveyancer's thinking will arise as the conveyancer hears of the "presence" of the absence of inclusion of the purchaser's wife in the sale agreement, which will result in the presence of an informal causa, but the absence of a valid legal causa based on the Matrimonial Property Act39 and the Marriage Act.40 This is likely to result in faulty legal causae for all future transfers due to a co-owner being excluded.41 Technically speaking both a wife in a community of property civil marriage and a wife in an African customary marriage have rights to share ownership. However, those conveyancers who know what they should know about African customary law will long since have realised the total impossibility of registering ownership in the name of an unregistered customary wife, unless the husband co-operates and makes her a co-owner in terms of the transfer documents.

The chance of a conveyancer's being able to assist his clients to register their customary marriage is so slender as to be not worth considering at all. Add to this the fact that no transfer to a married couple can take place without a marriage certificate, be it a civil or a customary marriage. This author has seen only two cases where a marriage certificate was produced for an African customary marriage, and this amidst the clear existence of numerous unregistered African customary marriages.

For the conveyancer operating in a business environment, who works closely with this kind of client, section 4(9) of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act42 appears to be its most relevant provision. This is the ambiguous and contentious section which provides that failure to register a customary marriage does not affect the validity of that marriage. Assisting a woman in an unregistered customary marriage, who wishes to effect registration of ownership of a share on the grounds of her marriage, as opposed to an agreement as to co-ownership, is impossible for ordinary conveyancing practice outside of a court order, which is a process as complex and expensive as multiple transfers.43

Most customary marriages appear to be monogamous, but the decision as to the formalisation of the relationship by registration is seldom effected. This should not be confused with co-habitation. It is a marriage, but it is a marriage for which there is no written proof. In conveyancing practice, transfer to those married in community of property is a different process from transfer to co-owners. Co-ownership due to cohabitation is agreed between the parties and ownership passes on registration. Co-ownership due to marriage in community of property is by operation of law and the right to property vests on the date of the marriage. The anomaly of section 4(9) is that - due to the absence of documentary proof - transfer giving effect to the married couple by operation of the law is prohibited, unless there is a court order.

A conveyancer has the time only to flick through the basic legal textbooks on his shelf and this is seldom going to include thinking through polygymous rights.44 The only emotion a conveyancer with a civil marriage certificate on his desk will feel is relief that his R500 advance clients have their status documents in order and that he can accordingly verify their status as required by law. The last thing he is going to ask of a man and wife ready to sign the power of attorney to transfer is whether section 4(9) applies and whether there is another wife involved. This is as unlikely as is his clients informing him of such a situation. It takes three for a man to get away with bigamy. It is only a second African customary wife who needs to contract with a first African customary wife. A civil wife is oddly under no such obligation, nor are there punitive consequences for her, even if she knew of the existence of the first unregistered customary wife.45

It is nothing short of a disgrace that unregistered African customary marriages are not recorded against title deeds in the same manner as those marriages by religious rites that do not as yet have legal consequences,46 nor are they respected with the fluidity of being seen either as a marriage or a civil partnership, as is accorded to gay couples in terms of the Civil Union Act.47 Cousins indicates that social embeddedness is central to understanding the gendered character of access to land.48 When women make their bed they often have to lie in it for better or for worse. The failure to describe a wife as a wife "disembeds" her, as the naming of the marital bed defines her either as a wife or a mistress in the eyes of the society that must protect her rights. Verification of unregistered customary marriage status is easily dealt with in the conveyancer's status affidavit, meaning that the absence of documentary proof need not be a bar to the correct registration of such marriages as "governed by the laws relating to unregistered customary marriages". However, with the legal system stacked against a conveyancer, in the very unlikely event that the rights of a prior wife do come to his attention, it will only make him see the presence of an earlier informal marriage, the absence of documentary proof upon which to verify it, and therefore the absence of a legal causa to transfer a share to the section 4(9) wife without a court order.

8.5 Prescription

The fifth matter that will colour a conveyancer's thinking will occur to him as he hears about the presence of a recognised long-term occupier but the absence of an owner who can be found. An occupier's acquisition of ownership is acquired only by operation of the law after 30 years, in terms of the law relating to prescription and immovable property. This will make him see the presence of an informal causa based on the occupation and the absence of a legal causa in terms of the Prescription Act.49

8.6 Law of delict and contract

The sixth matter that will colour his thinking will arise as he hears the facts that lead him to think through whether or not the transaction is voidable due to the seller's misrepresenting the transaction to the purchaser. The client will be asked if the seller indicated that he was entering into the sale illegally due to a pre-emption clause under the Housing Act.50 The minefield of misrepresenting the rights of an unregistered African customary wife is unlikely to be raised. He will then consider the alternative possibility of the presence of a business transaction based upon a mistake due to the mutual absence of understanding that the property was not capable of transfer. This will make him see the presence of an informal causa and the absence of a legal causa due to the commercial transaction's being void due to mistake.51

8.7 Constitutional law

The seventh matter that will colour a conveyancer's thinking will arise as he hears the facts which reflect the presence of discrimination based on gender and marital status.52 This will make him see the presence of an informal causa based on what is probably an African customary law perception which clashes with the Bill of Rights equality provision. The presence of such legal causae which are founded on patriarchal norms runs the risk of being made absent due to unconstitutionality.

8.8 Law of unjust enrichment53

The eighth matter which will colour his thinking will occur to him as he hears about the presence of a transaction, but the absence of a valid deed of alienation54 and the possible remedies that a personal rather than a real right may confer. Since the conveyancer sees that it is the right to the house, not the money, that the client has approached him to protect, the conveyancer knows there are only two routes open. Either the client must be told that an informal causa is not a causa and his agreement is not a real agreement,55 or he must be told that to make his rights present, a high court order must be obtained.56

By this time the conveyancer begins to feel that legal text books and statutes have all the appeal of a mathematician extolling the virtues of imaginary numbers.57 The chances that the client will feel his R500 advance has been well spent or feeling that five years of legal training and many years of practical legal experience has brought him or her even a centimetre closer to justice are absolutely nil. Indeed, the client is likely to feel dangerously antagonistic towards conveyancers as a class and the justice system as a whole. The depth of anger and frustration amongst the poor in such a context, when they are trying to work their way out of poverty, should not be underestimated.

9 What are the conveyancer's options?

Realising that common sense must prevail, the conveyancer thinks as follows:

• Is there a lawful causa to transfer?

• If so, is there adequate proof of it as required by the conveyancing process?

• If there is no lawful causa or inadequate proof, is a court order an option?

• If so, is there adequate proof of her client's right?

This brings the conveyancer back to the most important question, namely the firm's 60% to 70% overheads and the R500 advance in the trust account for a file which would normally run a bill far in excess of the total value of the property to be transferred. The frustration of conveyancers in such a context, when they are trying to run a business, should not be underestimated. Such a system positively begs for conveyancers to come up with their own parallel systems of how to achieve registration outside of the normal parameters of what the law demands.

Conveyancers are often blamed for their cavalier treatment of poor clients. This critique is misplaced. It is not the legal cart but the legal horse that critics need to address.

10 Theoretical questions a conveyancer might raise

For the conveyancer who works regularly with such transfers, common threads will start running through the transactions. The first thread indicates that there has been a transaction which underpins the disposal of the right to ownership, but the problem is the absence of its being transacted in terms that are legally acceptable. The second thread is the absence of written proof of it in the form that is required by Regulation 44 to the Deeds Registries Act.58 This regulation requires that conveyancers verify the material being inserted in the transfer documents on the basis of formal documents such as identity documents, marriage certificates, letters of executorship, letters of authority, divorce orders and court orders.

On the complex matter of the alienation causae, the simple question is if the affluent have the right to ignore the rules of the poor? If the poor do not report deceased estates, must the law deal with their practical arrangements to deal with the assets of the estate? If the poor do not appoint formal guardians for orphaned minors but make practical arrangements for relatives to come and live in the house, must the law deal with this? If the poor transact sales verbally, must the law deal with this? To use Shakespeare's idiom, if we regard ourselves as virtuous and we will it, shall there be no more cakes and ale?59 If we believe in a free market economy, is the simple answer that we should be seeking mechanisms to recognise what the poor accept as a valid disposal of their privately owned property? Legal certainty is a key issue in this debate and the Overstrand Projects are modelled to address this.

This constant frustration by the law of the poor's attempts to face down the dragons of poverty must undermine a free market economy in the microcosm. What is the consequence of removing most of the poor's workable legal tools which entrench rights to ownership? The normal rules of the law of sale, abandonment, cession, assignment, succession and delict frequently malfunction for the poor, due to their tragic, shifting lifestyles. Must this failure of the law be allowed to result in a situation which gives the poor a total lack of interest in the value of formal private ownership? A problem must be faced before it can be solved. Economists and small business entrepreneurs need to enter this debate. To take a metaphor from the gentleman's game, what are the consequences of a handicap that removes from the poor even a sporting chance of legality?

11 What a conveyancer wants

Needless to say a conveyancer does not have the time, with a R500 advance on his fees, to think through these imponderables. His is just to do or die commercially. He functions in a business environment - he is not a social worker. What a conveyancer wants is a legal causa, short and sweet, that the Deeds Office will accept, and a client who can furnish him with the correct documents in order for him to comply with the strict requirements as to verification.

Conveyancing is probably the most demanding of the legal specialisations when it comes to precision and detail. The accuracy required depends on clients who can brief you accurately. Many of the people who are affected by these legal problems were excluded from citizenship, franchise and the right to borrow in the apartheid years, resulting in the conveyancing legislation from this period not considering their needs and rights. There is a tremendous clash of interests once a conveyancer tries to assist someone to register who might be illiterate, or apathetic from poverty, or unaware of her marital rights. People who obtain state subsidies and become owners of low-cost properties are often drawn from such groups.

The shortest, sweetest causa is an award with the weight of a court order in terms of which a literate commissioner can pass transfer directly to a low-literate transferee, irrespective of how many disposals took place from the time of the original owner to the time of the final transferee.60 This is what the Land Titles Adjustment Act61 can do and this is the outcomes-based system which the Overstrand Municipality is attempting to bring into being. If it succeeds in the form in which it is proposed, it will have the advantage of remaining invested in the formal registration of transfer system, while taking full cognizance of the documentary problems relating to the lowliterate.

12 Low-literacy and the right to the protection of the law

The rights of the low-literate to registration of ownership need to be considered in the light of the equality provisions of the Bill of Rights.62 Does an insistence upon written formalities - in order for low-literate people to be able to prove their ownership rights - result in discrimination based on language and a verbally based culture? Many of the alienations of the poor in the low-cost housing arena seem to lie between African customary law and the common law. It is nevertheless clear that these transactions are often underpinned by a largely oral tradition similar to that of African customary law, which does not translate easily into the formalistic law of conveyancing practice. Those who choose an African customary worldview are, of course, usually at ease both with a written and a verbal culture. However, those consumers who need lowcost housing are less likely to be so.

Part of the Overstrand Municipality's drive to improve title deed service delivery has been to entirely overhaul the housing record-keeping systems, to ensure later compliance with conveyancing requirements. In recognition of the challenges faced by the low-literate, it is intended that the hard copy files will be compartmentalised according to colours, so that low-literate beneficiaries can follow progress by "reading" colours. In thinking through the systems and the necessity of accessibility for housing consumers (in whose interest the housing department has been established) some fundamental questions have arisen.

The reason for the complexity regarding the absence of the documentary proof required by conveyancers is to be found in the simple fact that these transactions occur in a context of low-literacy.63 If all document-based systems are always going to be a problem, is this an indicator that it is the fact that documents are required that is the root problem, rather than the poor's inability to make use of them? If this is so, might it be said - in the context of the low literate - that a construct of legal rights which, for their very existence, requires the formality of writing, is inherently discriminatory? This suggests the need for less reliance upon documentary evidence and a minimalisation of the use of written proofs. A signed power of attorney to transfer can be processed by a conveyancer when a seller cannot be contacted, whereas a valid sale agreement cannot, as signature of the power of attorney is still required. If the poor believe a sale agreement is sufficient to transfer ownership, a commissioner appointed in terms of the Land Titles Adjustment Act64 should be able to make an award as to ownership, upon which a conveyancer can register transfer without a signed power of attorney. The threshold of the monetary jurisdiction of such a court can be pegged by the Minister of Land Affairs on designation of the erven, to ensure that such a process is not abused.65

Such questions must turn back to the understanding of justice as expressed in previous orally orientated eras. Religions that communicate by means of the "text" of visual icons are not less advanced than those that communicate by means of a written sacred text. As soon as assumptions regarding the virtue of literacy are removed, alternative possibilities can be explored.66 As Goethe said, we see what we know.

There is one unsubstantiated, hearsay comment that must be included in this paper in the fear of the possibility that it might be accurate. In a recent conversation a personal opinion was expressed that in some areas up to 70% of people are unable to attend to their Home Affairs documentary needs, either due to the apathy of poverty or lack of formal education. What would this mean for our systems if it were true? Will the current consumer protection provisions be worth the paper they are written on if the low-literate constitute such large numbers and they are forced to function in a written, paper-based rights system? Recognising that there is a need for both a causa for transfer and a need for publicity in the form of the registration of deeds, it would appear that a court order is the only mechanism able to bridge the gap between low-literacy and literacy. A court can hear oral evidence and a court order can translate the outcome of such evidence into the written recording necessary for registration of ownership.

13 Proof within an oral tradition

At first glance stepping back from the written paradigm in immovable property transactions amongst the poor may appear a revolutionary proposal, but not if one stops to consider that the expectation that everyone must be literate is a social phenomenon of the last century. For many, low literacy is due to the prevalence of political unrest during their school years, not a lack of interest in education. It seems only fair that the ball should be thrown back into the theoreticians' court to research the alternative forms of proof of the disposal of immovable property accepted in the eras when literacy was uncommon. No attempt will be made to canvas the systems of the past, nor the systems of the present living customary law, but a few practical points follow.

In one consultation, when a signatory was asked her understanding of the meaning of the word "spouse" on a document beside which she had to sign, she indicated that it meant someone who was well educated and who could explain the meaning of the documents. Low literacy makes a mockery of the Matrimonial Property Act and the Alienation of Land Act's perspective of signing witnesses and documentary proof as the soundest record as to the veracity of an event. The requirement for plain language to be used in all legal documents is unlikely to be broadly effected for a very long time and such failures of understanding will persist despite the education system's best efforts. A recent exercise requiring a plain language translation of a sale agreement into English, Afrikaans and Xhosa has made clear the extensive expertise necessary and the great difficulty and cost of such a process.67

A further illustration can be found in the formal processes for someone other than a biological parent to be appointed as the guardian of a child. Written proof of such an appointment is necessary for transfer purposes when a child is the right holder and the guardian must attend to the formalities of transfer. In a recent housing file an affidavit was handed in with the following statement by the caretaker of such a child: "I have no ambition of abdicating her. I literally bind myself to provide for her as long as it takes. That's all I would like to furnish". Apart from indicating that this poor citizen is of noble character, this quaint statement indicates both a brave attempt to deal with the obfuscation of the law, while at the same time stating succinctly the most salient problem for registrations emanating from a housing department, namely that such an affidavit is all that housing beneficiaries "would like to furnish". In the same vein, a high court order is required in order to establish the death of a person where there is no death certificate. This is far beyond the pocket of an unfortunate purchaser who is faced with the fairly common problem of a long-deceased seller.

There is no clear definition of what constitutes a document for the purposes of the law of evidence.68 Schwikkard uses the definition of Darling J in R v Daye69 as her departure point, namely his statement that a document is "any written thing capable of being evidence".70 When working with the illiterate and low-literate, the question is not what written thing can be capable of being evidence, but whether any written thing is capable of being evidence. As soon as this is understood the written "proofs" of the Alienation of Land Act can be seen to be a contradiction in terms.71 If you cannot read and write it does not mean that you cannot prove something. In the same way that a dialect is not a lesser language than the mother tongue, earlier forms of proof have no less potency than current ones, particularly since the current forms of written proof have little contact with the reality of the poor's transactions. Matters such as the date of sale are very important to ownership rights. To make absent a physical witness and prioritise the proof provided by a written document is to advantage the literate person who transacts and disadvantage the illiterate person. It could be argued that the requirement for written proof has to do with certainty and should not be confused with ability, but the question must be asked, certainty for the benefit of whom?

Lest there be concern that a reversion to oral forms of proof for the poor will result in our first-world legal system crumbling to dust and ashes, it must be pointed out that no seller will be placed in the position of a poor person entering into a business transaction to purchase the kind of high-value property that forms the basis of South Africa's first-world business environment. The legal constructs of the low-literate need not infringe upon the literate world's understanding of proof, unless the literate world is dealing in low-value properties, which is of course the context of downward raiding. Downward raiding - land grabbing by the affluent from the poor - is a concern to all who work with state-subsidised low-cost housing rights. It is not in the interest of the justice system to make it easy for an affluent person to prove she has purchased a house from a poor seller and difficult for the poor person. Low literacy would need to be proven, in the same way that any disability is a question of proof, but for the literate person contracting with the low-literate in the twenty-first century, as opposed to the literate person in Kandinsky's day, the route of audio-visual recordings is open as a further means of proof of oral agreements which include witnesses.

First-world legal standards and registration systems must be maintained if Africa is not to be re-colonised by the first world. Nevertheless, education, as important as it clearly is, is not the only weapon we have to eradicate poverty. Wisdom is often of more value than knowledge. There are many South Africans who have no hope of achieving literacy in their lifetime. There are lateral ways whereby the law can level the playing field of the business environment of the poor with the business environment of the affluent.

A privately owned house is an asset - you do not have to be able to read and write to understand the value of it. Currently the state retains the power to control which disposals are permissible for a period of eight years after the date of sale of a state subsidised house, thereby ensuring who should have priority in housing, although whether such provisions are to the advantage of the poor is questionable. It is also open to the state, should it so wish, to pass laws whereby a Deeds Office caveat prevents the transfer of previously subsidised state housing to anyone who already owns registered immovable property.

What does it mean, to honour the constitutional principles to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights of the low-literate?72 Does it mean to feel sorry for those who read and write inadequately or does it mean to attribute the dignity of equality and freedom to their verbal rules for disposal of their privately owned immovable property? What is it that justice demands?73 Is the jurisprudence of Socrates, who left nothing in writing and was possibly illiterate, not to be valued?74 If the decision as to the value of oral forms of proof is to be made only by the literate, is this not a case of nemo iudex in sua propria causa, - that "no-one should be a judge in his own cause"? A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. So is a lot.

There is a need for an urban land small-claims court which is flexible enough to recognise the legal constructs of those engaged in a verbal culture, while at the same time translating them into a written, registered form. Needless to say, with so many questions in the field of pro-poor registrations, if only the complex is focussed upon there can be no hope of providing an answer simple enough to make the next step possible. The Overstrand Municipality's projects are outcomes-based and are functioning on a constrained municipal budget with no outside funding. Together with this they have had to proceed with the legal tools that are at hand, which are blunt tools at best. This is counterbalanced by the involvement of staff and management of the highest calibre within the housing and social upliftment department. Therefore while there are still many rough edges to the model - the work has gone forward in the belief that it is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.

14 The Overstrand Municipality proposed models

A municipality is a natural partner for assisting with the stabilisation of private second-generation transfers of state subsidised housing, as municipal administrative costs escalate substantially when their records of ratepayers and residents are inaccurate. Not only administrative charges are incurred when the records of ownership are incorrect, but there is also a marked detrimental impact on the efficient collection of municipal rates and taxes. The Overstrand projects below have been conceptualised, but only some aspects of them have been tested.75

14.1 The student clinic project for undisputed transfers

The first project deals with providing access to conveyancing services where the case is a simple matter of the parties not being able to afford the legal costs. All conveyancing needs very strong backup administration, and paralegals capable of precision administration are necessary so that the professional conveyancers can be released to perform the specialist work in a sustainable way. The Overstrand project looks to further reduce the professional input through the use of law student vacation clinics to assist with undisputed sale transfers.

The first phase of the pilot project was run under the auspices of the Property Committee of the Cape Law Society. The aim was to facilitate pro bono registrations of properties purchased for under R30 000 in which no funds need to be collected, and there is no dispute. Access to the clinic is granted only where all status documents of both the seller and the purchaser are furnished beforehand. Clinic files and rates clearances are collated with the assistance of housing officers and the files are assessed for their suitability by the clinic facilitator.

In the first testing phase the Overstrand partnered with Stellenbosch University and used law students from second-year onwards. A member of the Property Committee of the Cape Law Society76 furnished precedents of all documentation for signature, and the students attended to the very time-consuming completion and signature of this documentation during the clinic. The documents are prepared in such a way that they can be forwarded to a pro bono registering conveyancer and the registering conveyancer does not need to interact with the clients.

Teams of students at each session of the clinic are supervised by one local conveyancer, who also attests the affidavits and has his time credited towards his pro bono hours. After registration the title deeds are sent back to the housing department for distribution. A municipal conveyancing clerk has been trained to act as the co-ordinator of the clinic and to perform other duties. The conveyancers, law students and the Law Society input are pro bono. The intention is that the only cost to the parties should be the deeds registry charges and some minor disbursements in other words, about R300 if they have the title deed, and a bit more if they do not.

More than half of the steps for these clinics have been tested, but the follow-up clinic has been put on hold until the new housing manager has settled in. The biggest hurdle is education regarding the need to make use of such a service, together with the collation of the files. The legal side is actually very, very easy if the files are in order before the clinic begins.

14.2 The land titles adjustment project for disputed transfers

The problem of effecting transfer changes entirely once there are de facto and de jure claimants to a low-cost property. A court order is needed, and obtaining one is an expensive and sophisticated process. The second project explores the potential of the Land Titles Adjustment Act77 to be used as a form of small-claims court for second-generation transfers, where there is more than one person who has a claim to ownership. This Act is presently being assessed for amendment. The Municipality is currently liaising with the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (the RDLR) for a pilot project and the question of the need for documentary proof has become central to the discussions. In the short term conveyancers have found that a court order is the only viable solution for such transfers to take place at scale, and the awards under the Land Titles Adjustment Act will have the effect of a court order. Real rights vest just as strongly with the handing down of a court order as with a registration of transfer. It is therefore worth considering if this does not also offer the opportunity for a different means of recording the right to ownership. Endorsements linked to cell-phone technology are worth exploring as a cheaper option.

A retired judge, justice Mark Kumleben, of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, now known as the Supreme Court of Appeal, is willing to act as pro bono commissioner in the early stages, thereby bringing the necessary juridical attribute of the wisdom of age to the awards. The discretion of the commissioner is very broad, but the bottom line is that this is a problem which potentially affects millions of South Africans and the normal legal fees to resolve the conflicts and give transfer can be more than the value of the property itself. Solutions that remove red tape must be sought or they will not be financially sustainable. A great benefit of the Land Titles Adjustment Act lies in its ability to transfer land directly from the commissioner, with no intermediate registrations. In addition, since the commissioner signs the transfer documents, he is able to instruct the conveyancer in accordance with the extreme precision which all functional conveyancing work requires. Only the documents of the final transferee will be required.

The value of the properties in the Overstrand project are generally below R30 000. Designation of previously state-subsidised housing in terms of the Land Titles Adjustment Act should be permitted only for properties valued under a certain threshold. The intention of the project is not to establish an alternative legal system for general use, but a workable system for poor landowners. In a context where there is little or no certainty as to ownership in second-generation transactions of this nature, the certainty of a land title adjustment award is in the interest of all.

The Overstrand model looks at a restructuring of responsibilities, whereby the municipal housing department undertakes a substantial amount of the work that would normally be for the account of the RDLR. The preliminary investigation (which is normally attended to by the RDLR) will be done by the Municipality by means of fieldworkers and housing officers. Much of this work is part of the highly experienced housing officers' day-to-day work, as municipalities hold the files with the beneficiary subsidy applications, which should include status documents. They also have the facilities to do deeds office searches, they hold the rates records, and control the rates clearances required for registration. They can take on the RDLR task of determining the applicant's financial status and can check the National Database so that free assistance is not given to claimants in possession of two properties. Files can then be batched for sending to the RDLR for designation, to minimise administration costs.

The model has been structured so that the commissioner's role becomes narrowly the role of adjudicating and passing transfer, and his fees should, after designation, be the only cost to the RDLR. The long-term sustainability of such a programme may be found in a commissioner's devoting a proportion of his time to pro bono claimants and a portion of his time to paying claimants within a certain threshold. The multiple notices in the Act are one of the few checks and balances provided for, and it is imperative that they be accurately done if all potential claimants are to be given an opportunity to state their case. Practitioners dealing with High Court matters for the poor find they have difficulty in serving the notices due to their clients' not knowing the residence of defendants, suggesting that legislation which requires notification by advertisement posted in public places rather than delivery of written documents is more conducive to procedural fairness for the poor. Loudhailers and posters will also be used. In terms of the Land Titles Adjustment Act the commissioner runs his own secretariat, but in the Overstrand project the housing department conveyancing clerk will attend to this.

It is possible that with experience it will be found that the system is sustainable for certain types of claims only. If the Overstrand project goes according to plan, batches of differing causes for transfer will be prepared in order to monitor this. Particular emphasis will be given to gender discrimination, as the application of African customary law perceptions is most at risk from challenges on this score. Wherever contradictions due to conflicting world-views are noted, every attempt will be made to call in experts to assist the voiceless to be heard, be they male or female.78 It may be that the assumptions of the literate/illiterate debate are replicated in the feminist/chauvinist dichotomy. Most gender-based equality challenges result in a reading of the Constitution, which disempowers men in patriarchal systems in order to empower women. The possibility exists, however, that women are predisposed to be vulnerable, while men are predisposed to be dominant. If so, the primary route to the protection of vulnerable women should be not only a race to educate all and empower females, but a race to educate men to protect women, while entrenching legal mechanisms that support male structures that respect and protect women and that punish those which do not.

The RDLR Framework Document for land titles adjustment refers to the Land Titles Adjustment Act as applicable where "persons lay claim to ownership without having proof". Section 6 of the Act states that the application must be supported by sworn declarations by the persons "alleging those facts, and by such documents as the applicant may be able to submit". This flexibility as to documentary evidence is both the danger and the wonderful opportunity that the Land Titles Adjustment Act offers to the poor and to wives in unregistered customary marriages. Provided it is properly managed, this sweeping discretion provided in the Act is in fact critical to the conveyancer's ability to deal with these problems.

Access to justice has little to do with what is in the law books and statutes. In the same way that attorneys specialising in litigation might first try to quash prosecution by speaking directly to the prosecutor, or an academic who specialises in ethics might censor certain ideas by marginalising a particular emphasis through the debates he chooses to raise, a woman's access to justice is most likely to be granted or refused without recourse to law. Gender-based corrective laws cannot reach a married woman who wishes to remain married,79 or female members of households who are not spouses but who wish to remain in a good relationship with the men of their family in a customary environment. Male advocacy is what can reach such women. The project will be sensitive to the need for women to be heard as well as the beneficial role of men who regard themselves as being bound to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights of their female relatives.80 It will also be mindful of the obvious fact that you cannot get a man down the aisle without his co-operation.

Since the project is privileged to have the services of justice Kumleben, its first aim is to set precedents for future use. Due to the wide range of issues, specialists will need to be drawn in and this will depend on pro bono offers of assistance and the funding available. In recognition of the issues relating to "embedded" rights,81 some of which apply to urban land, the Overstrand projects will aim to avoid an adversarial approach to evidence upon which awards will be based. Every attempt will be made to include all stakeholders to resolve internal conflict, to achieve as many awards as possible by consensus amongst the parties, and to ensure fluidity of negotiation. Where appropriate, the number of parties entitled to undivided shares in the property can be extended beyond the usual two co-owners.

15 First transfers of low-cost housing from the state

While the Overstrand project aims to deal with privately owned second-generation transfers of low-cost housing, the issues it raises are equally relevant to the first transfer from the state. Many of the first transfers occur in a situation where, by the time registration needs to take place, the de facto owner is not the de jure owner. The current situation, where the state has to manage this highly complex reallocation of rights and then attempt to effect transfer, is unfair on the administrative government officials who need to attend to it. The problems of the first transfer often affect the second-, third-and fourth-generation transfers, becoming irresolvable.

What is essentially a legal problem of resolving conflicting legal claims cannot and should not be handled administratively by government officials with no legal training because it is too expensive to go the legal route.82 If an assessment is made of the figures it would no doubt transpire that the cost of the current system to the state is greater than what the cost of efficient legal measures would be. In the volatile world of low-cost housing a permanent alternative dispute resolution forum, such as that outlined here, is even more urgently needed for these disputed first-generation transfers than it is for second-generation transfers. The lessons learned in secondgeneration private disposal contexts should be invaluable to the first transfer policy problems.

16 Conclusion

The Consumer Protection Act83 will not apply to once-off transactions relating to low-cost housing. Its aims are nevertheless worth reflecting on as a means of understanding the kind of society South Africa wishes to build for the future.

Excerpts of section 3(1) of the Act read as follows:

The purposes of this Act are to promote and advance the social and economic welfare of consumers in South Africa by-

| (a) | establishing a legal framework for the achievement and maintenance of a consumer market that is fair, accessible, efficient, sustainable and responsible for the benefit of consumers generally; | |

| (b) | reducing and ameliorating any disadvantages experienced in accessing any supply of goods or services by consumers |

| (i) | who are low-income persons or persons comprising lowincome communities; | |

| (iii) | who are minors, seniors or other similarly vulnerable consumers; or | |

| (iv) | whose ability to read and comprehend any advertisement, agreement ... is limited by reason of low literacy, vision impairment or limited fluency in the language in which the representation is produced, published or presented; |

| (c) | promoting fair business practices; | |

| (d) | protecting consumers from | |

| (i) | unconscionable, unfair, unreasonable, unjust or otherwise improper trade practices; | |

| (g) | providing for a consistent, accessible and efficient system of consensual resolution of disputes arising from consumer transactions; and | |

| (h) | providing for an accessible, consistent, harmonised, effective and efficient system of redress for consumers. |

The letter of this law does not place a responsibility on a municipality to protect private poor owners who are contracting with private third parties. However, the spirit of this law is what the Overstrand Municipality has been trying to give effect to. It is hoped that whether or not the Overstrand projects come to fruition, something of value will have emerged from the process of grappling with the issues surrounding the pro-poor registration of ownership of immovable property. South African business law must think through the twenty-first century assumption of written proof as being superior to audible and visual proof in the face of the need to respect diversity. This is necessary in order to explore the system of justice of the new verbal culture which is emerging amongst the poor living in low-cost housing.84 With immovable property transactions by the poor de facto risk passes differently due to a vacuum of law. A responsible legal philosophy is best expressed in the following words of Lizelle Kilbourn:

Think of society (or everyday life) as a game of soccer. If there are no rules, chaos will result. No one will know what is permissible and what is not. The "chancers" will do what they like and the honest players will suffer injustice. Even those players who want to be fair will be forced to become aggressive or dishonest players. The game will be no fun for the spectators either. Without rules there can be no fair play. This is as true for the functioning of society as it is for the playing of a soccer game. And not only must the rules exist, they must also be enforced. If the rules exist but are not enforced, they become meaningless as if they had never existed in the first place.85

Readers who have ploughed their way through the last thirty pages are no doubt wondering if this article has a beginning, a middle, and - more importantly - an end. Indeed it does. This paper begins with the visual complex-simplicity of abstract relationships expressed in Kandinsky's painting. The middle is to be found in the audible complex-simplicity of a conveyancer being instructed verbally by a client who is poor and has little education in the field of literacy. It must end with the written complex-simplicity of a literary metaphor. In order for South Africans to love justice, black-letter lawyers with panache will have to release the eloquence of the voiceless poor, in order for them to define their understanding of what is just in the disposal of privately owned property. Then, together, the written and oral law might hope to win the heart of the nation to a commitment to the rule of law upon which a free market economy is based.86

Schedule 1

QUOTATION

TRANSFER: ERF TO AN INDIVIDUAL

PURCHASE PRICE: R 5 000 000.00

Bibliography

Badenhorst PJ, Pienaar J en Mostert H The Law of Property (LexisNexis Butterworths Durban 2003) [ Links ]

Bennett TW Customary Law in South Africa (Juta Cape Town 2004) [ Links ]

Claassens A and Cousins B Land, Power and Custom (UCT Press Cape Town 2008) [ Links ]

Collier-Reed D and Lehmann K Basic Principles of Business Law (LexisNexis Durban 2009) [ Links ]

Cousins B "'Embeddedness' versus titling: African land tenure systems and the potential impacts of the Communal Land Rights Act 11 of 2004" 2005 Stell LR 488-513 [ Links ]

Derrida J Of Grammatology (translated from the original French by GC Spivak) (Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore 1974) [ Links ]

De Soto H The Mystery of Capital (Basic Books New York 2000) [ Links ]

Du Plessis LM Re-interpretation of Statutes (LexisNexis Butterworths Durban 2004) [ Links ]

Kilbourn L The ABC of Conveyancing (Juta Cape Town 2008) [ Links ]

Mostert H et al The Principles of the Law of Property (Oxford University Press Cape Town 2010) [ Links ]

Nel HS Jones Conveyancing in South Africa (Juta Cape Town 2010) [ Links ]

Pienaar G "The land titling debate in South Africa" 2006 TSAR 435-455 [ Links ]

Plato The Republic (translated from the original Greek by D Lee) (Penguin Books London 1983) [ Links ]

Rostand E Cyrano de Bergerac (translated from the original French by C Fry) (Oxford University Press Oxford 1998) [ Links ]

Ryan M Literary Theory: A Practical Introduction (Blackwell London 1999) [ Links ]

Schwikkard PJ and Van der Merwe SE Principles of Evidence (Juta Cape Town 2009) [ Links ]

Selden R and Widdowson P A Reader's Guide to Contemporary Literary Theory (Harvester Wheatsheaf New York 1993) [ Links ]

Shakespeare W Twelfth Night (Collins London 1965) [ Links ]

Sharrock R Business Transactions Law (Juta Cape Town 2007) [ Links ]

Swift J Gulliver's Travels (Oxford University Press Oxford 1973) [ Links ]

Taschen B Wassily Kandinsky 1866-1944. A Revolution in Painting (Drukhaus Cramer Greven 1993) [ Links ]

West A The Practitioner's Guide to Conveyancing and Notarial Practice (Juta Cape Town 2004) [ Links ]

Whittal J "The potential use of cellular phone technology in maintaining an upto-date register of land transactions for the urban poor" 2011 PER current edition. [ Links ]

Register of court cases

Dawood v Minister of Home Affairs 2000 3 SA 936 (CC) R v Daye 1908 2 KB 333

Register of legislation

Administration of Deceased Estates Act 66 of 1965

Alienation of Land Act 68 of 1981

Civil Union Act 17 of 2006

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008

Deeds Registries Act 47 of 1937

Estate Agents Act 112 of 1976

Housing Act 107 of 1997

Intestate Succession Act 81 of 1987

Land Restitution Act 22 of 1994

Land Titles Adjustment Act 111 of 1993

Marriage Act 25 of 1961

Matrimonial Property Act 88 of 1984

Prescription Act 68 of 1969

Reform of African Customary Law of Succession and Regulation of Related Matters Act 11 of 2009

Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 120 of 1998

Recognition of Customary Marriages Amendment Bill 2009 Wills Act 7 of 1953

Register of internet sources

Ghost Digest conveyancing news and views 22/01/09 www.ghostdigest.co.za [ Links ]

GilesFiles 2010 Labour Court Directive - judges mediating before adjudicating? www.gilesfiles.co.za/blog/?p=999 [ [ Links ]date of use 1 November 2010]

Giles J 2008 The benefits of plain legal language www.michalsons.com/thebenefits-of-plain-legal-language/20 [ [ Links ]date of use 1 November 2010]

List of abbreviations

| RDLR | Department of Rural Development and Land Reform |

| Stell LR | Stellenbosch Law Review |

| TSAR | Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg |

1 There does not appear to be another conveyancer in the author's field of specialisation. It was therefore thought to be worthwhile to record the issues as broadly as possible.

2 Taschen Wassily Kandinsky 9.

3 Taschen Wassily Kandinsky 9.

4 Ss 10A and 10B Housing Act 107 of 1997 as amended in 2001.