Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ)

On-line version ISSN 1727-3781

PER vol.12 n.4 Potchefstroom Jan. 2009

ARTICLES

Traditional leadership and independent Bantustans of South Africa: some milestones of transformative constitutionalism beyond Apartheid

SF Khunou

Freddie Khunou. UDE (SEC) Moretele Training College of Education B Juris (Unibo) LLB (UNW) LLM (UNW) LLD (NWU Potchefstroom Campus). Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, North-West University, Mafikeng Campus

SUMMARY

The institution of traditional leadership represents the early form of societal organisation. It embodies the preservation of culture, traditions, customs and values. This paper gives a brief exposition of the impact that the pre-colonial and colonial regimes had on the institution of traditional leadership. During the pre-colonial era, the institution of traditional leadership was a political and administrative centre of governance for traditional communities. The institution of traditional leadership was the form of government with the highest authority. The leadership monopoly of traditional leaders changed when the colonial authorities and rulers introduced their authority to the landscape of traditional governance.

The introduction of apartheid legalised and institutionalised racial discrimination. As a result, the apartheid government created Bantustans based on the language and culture of a particular ethnic group. This paper asserts that the traditional authorities in the Bantustans of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei seemed to be used by the apartheid regime and were no longer accountable to their communities but to the apartheid regime. The Bantustans' governments passed various pieces of legislation to control the institution of traditional leadership, exercised control over traditional leaders and allowed them minimal independence in their traditional role. The pattern of the disintegration of traditional leadership seemed to differ in Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei.

The governments of these Bantustans used different political, constitutional and legal practices and methods to achieve this disintegration. The gradual disintegration and dislocation of the institution of traditional leadership in these four Bantustans led to the loss of valuable knowledge of the essence and relevance of the institution of traditional leadership.

One of the reasons for this anomaly emanated from the fact that undemocratic structures of government were established, commonly known as traditional authorities. More often than not these traditional institutions were mere puppet institutions operating on behalf of the Bantustan regime, granted token or limited authority within the Bantustan in order to extend the control of the Bantustan government and to curb possible anti-apartheid and anti-Bantustan-system revolutionary activity within traditional areas.

The advent of the post-apartheid government marked the demise of apartheid and the Bantustan system for traditional leaders and the beginning of a new struggle for the freedom of the traditional authorities. This paper highlights changes brought about by the new constitutional dispensation in the institution of traditional leadership. The author demonstrates that the primary objective of the democratic government of South Africa in this regard is to transform the institution of traditional leadership and re-create the institution completely in line with the values and principles of the 1996 Constitution and democracy. The post-apartheid order rejects the old order as far as it is sexist, racist, authoritarian and unequal in its treatment of persons.

All of the rules, principles and doctrines of the institution of traditional leadership apply in the new dispensation only in so far as they are rules, principles and doctrines that would survive the scrutiny of the present society when measured against their compliance with the requirements of human dignity, equality and freedom. The government has enacted democratic legislation intended to change the institution of traditional leadership and make it consistent with the 1996 Constitution.

The institution of traditional leadership is obliged to ensure full compliance with the constitutional values and other relevant national and provincial legislation. The right to equality, including the prohibition of discrimination based on gender and sex, has an important impact on the institution of traditional leadership. For example, under the new constitutional dispensation women may become traditional leaders in their traditional communities, which is contrary to the old and long observed African customary rule of male intestate succession, which excluded women from succession to the position of traditional leadership.

One of the remarkable features of the transformation of traditional leadership in South Africa is that gender equality has been progressively advanced. The inclusion of women in traditional government structures adds democratic value and credibility to the institution of traditional leadership, which for many years remained essentially male-dominated. The doctrine of transformative constitutionalism is well established in South Africa.

Keywords: Traditional Leadership, Bantustans, Transformative Constitutionalism, Apartheid, Homeland System, Colonialism, 1996 Constitution, Legislation, Democratic Principles, Representative Government, Interim Constitution, Gender Equality, Indigenous Customs, Discrimination, Bills of Rights, Indirect Rule

1 Introduction

The object of this article is to explore and discuss the legal position and the role of the politics of the traditional leaders in the independent Bantustans or homelands of apartheid South Africa. As a point of departure, this article gives a brief account of the status of the traditional leaders before the inception of apartheid. In 1948, the now defunct National Party (NP) won the general elections and ascended to political power. The party's victory was marked by the formal introduction of apartheid.1 The main goal of the NP was racial, cultural and political purity.2

The foundation of apartheid was premised on the formation of artificial black nations or homelands in reserves. These homelands were created on the basis of the language and culture of a particular ethnic group.3 The political leadership of the homelands served as the prototype of the disintegration of traditional authorities. The traditional authorities in these 'artificial' states seemed to be used by the homelands' regime and were no longer accountable to their communities but to the entire political hegemony of apartheid.

The TBVC states enacted a considerable number of legislative measures, which influenced the structures of traditional leadership. This article elaborates on how the TBVC states manipulated the institutions of traditional leadership and how the roles and powers of traditional authorities were greatly altered. This article further proceeds to examine the constitutional and legislative changes of directions which have been influenced by both the 19934 and 19965 Constitutions of South Africa and shows how these changes have been initiated. The present South African government has launched a transformation project of the institution of traditional leadership. This project is intended to cure the ills of the past and democratise the institution in accordance with the constitutional imperatives.

2 Background perspectives

In the pre-colonial era, traditional leaders and traditional authorities were important institutions which gave effect to traditional life and played an essential role in the day-to-day administration of their areas and the lives of traditional people. The relationship between the traditional community and traditional leader was very important. The normal functioning of the traditional community was the responsibility of the traditional authority.6 The pre-colonial traditional leadership was based on governance of the people, where a traditional leader was accountable to his subjects. According to Spiegel and Boonzaier, there is much evidence that in pre-colonial times a significant proportion of the Southern African population was organised into political groupings with centralised authority vested in hereditary leaders known as 'chiefs'.7

Before the inception of apartheid, the traditional authorities were the instruments of indirect rule. Indirect rule or rule by association, as Ntsebeza noted, was created to manage the Africans under the administrative rule rather than to enfranchise them.8 The indirect rule was a British concept and not the making of the Afrikaner nationalists. The policy of indirect rule purported to preserve the pre-colonial structures of the traditional leadership. However, as Ntsebeza observed, in reality it was established as a means of controlling traditional communities in their areas.9 The leadership monopoly of traditional leaders changed when the colonial administrators and rulers introduced their authorities. Through the colonial system, traditional leaders became the agents of the colonial governments. The traditional authorities were recognised and shaped by colonial governments to suit, adopt and promote the objectives and aims of their colonial strategies and missions.

The successive colonial governments of South Africa enacted a considerable number of legislative measures to change the pre-colonial structures, roles and powers of the traditional leaders. For example, the Black Administration Act10 was enacted to give limited powers and roles to traditional leaders. This was due to the fact that the Governor-General was made the supreme chief of all traditional leaders in the Union of South Africa. The colonial and post-colonial governments recognised the institution of traditional leadership as an important political instrument.

At some point they withheld support from a particular traditional leader by appointing another in his place. They would also remove certain rights such as control over the distribution and administration of land. This resulted in a radical change in the leadership roles of the traditional leaders.11 What occurred in Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei provides a good example of change in the leadership roles of the traditional leaders.

3 Strategic creation of homelands

The borders of the homelands were 'fixed' long before apartheid was introduced as an official government policy, namely by the 1913 Land Act12 and the 1936 Trust and Land Act.13 When Verwoerd became Prime Minister of South Africa in 1959, he introduced the Promotion of Black Self-Government Act.14 The main objective of this Act was to create self-governing black units. The Black population was arranged and categorised into national units based on language and culture. There was the North-Sotho unit, the South-Sotho unit, the Swazi unit, the Tsonga unit, the Tswana unit, the Venda unit, the Xhosa unit and the Zulu unit.15

The administrative authorities in these national units were to be based on the tribal system. The government's contention was that each nation had to develop according to its own culture and under its own government. The government further argued that in this process of development, no nation was supposed to interfere with another.16

The Promotion of Black Self-Government Act laid a foundation for the constitutionalisation of separate development. This is so because it had the effect of creating radical separation not only for blacks from the white South African population, but also of black ethnic groups from each other. This was aptly illustrated partly in the Preamble of the Act as follows:17

The Bantu people of the Union of South Africa do not constitute a homogenous people, but form separate national units on the basis of language and culture… it is desirable for the welfare of the said people to afford recognition of the various national units and provide for their gradual development within their own to self-governing units on the basis of Bantu system of government … and its expedient to provide for direct consultation between the various Bantu national units and the government of the Union.

The basis of the Promotion of Black Self-Government Act was to ensure that blacks lived in the Bantustans and ran their own affairs without any shares in the greater South Africa. The Bantu reserves were transformed into Bantustans, later called homelands. The communities in these Bantustans were to be guided and led by the traditional leaders. Traditional leaders were used by the system to sustain the legitimacy of the Bantustans because the idea of the homeland system was to divide and rule black people.18

Verwoerd argued that the policy of independent black homelands would offer blacks economic opportunities and political representation in the reserves. As a result, traditional leaders were manipulated by the government to accept the idea of self-rule or independent homelands. Some of these homelands gained independence with the idea of forming a commonwealth with South Africa. This vision of grand apartheid became the ideal for white South Africa. The independence of the four South African homelands, namely Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei, meant that all of the Xhosa, Tswana, Venda and many other black population groups had effectively become foreigners in their own country.19

The leaders of these four homelands who 'sold' their subjects out and accepted independence endorsed the idea of independence. Most of these leaders had in their personal capacities reaped the fruits of independence. To the apartheid government, the vision of separate development was an alternative to domination by the black majority. To achieve this ideal, they thought it prudent to divide and rule the black majority. In fact, the plan to create the Bantustans was a result of fear of the united black community by the apartheid government.20

After Verwoerd's assassination in 1966, Vorster became the Prime Minister of South Africa. According to Walter, Vorster described his black policy, which differed little from that of his predecessor, as follows:21

I believe in the policy of separate development, not as a philosophy but also as the only practical solution in the interests of everyone to eliminate frictions and to do justice to every population group as well as every individual. I say to the Coloured people, as well as to the Indians and the Bantu, that the policy of separate development is not a policy, which rests upon jealousy, fear or hatred. It is not a denial of the human dignity of anyone, nor is it so intended. On the contrary, it gives the opportunity to every individual, within his own sphere, not only to be a man or woman in every sense, but it also creates the opportunity for them to develop and advance without restriction or frustration as circumstances justify and in accordance with the demands or development achieved.

Vorster believed that separate development was the only policy that could accommodate otherwise irreconcilable political and cultural differences among the various national groups. Therefore, he insisted that each nation was to determine its own future. One of the objectives of Vorster's government was to make South Africa safe for the white population. This could be achieved only if blacks were given citizenship of the homelands and denied citizenship of the so-called white South Africa. In 1970, the National States Citizenship Act22 was promulgated to provide citizenship to blacks in homelands.23

This measure provided that all blacks of South Africa would be citizens of their respective homelands.24 The system was designed in such a way that Bophuthatswana would be the homeland for the Tswana, Venda for the Vendas, Transkei for the Xhosas and Ciskei for the Xhosas as well. In other words, this Act eliminated all blacks from the Republic of South Africa, thereby taking a policy of separate development to its full fruition. As a result, black South Africans became citizens of ten homelands depending on their ethnic groups.25 The NP government intended to achieve a policy of pure apartheid by racial separation.26

The Department of Native Affairs was mandated to shape the policy of racial discrimination by creating more black nations with languages, cultures and interests of their own.27 It seems Jansen, the then Minister of Native Affairs, hoped that by creating more black nations, the government would foster solidarity between different traditional communities in South Africa. In fact, the policy of apartheid divided and separated traditional communities. In so doing, apartheid sowed the seeds of hatred and hostility between different traditional communities. The apartheid government was successful in sustaining its policy of tribal divisions for many decades.28 For example, Transkei became a self-governing territory in 1963 and was the only homeland which was dealt with outside the Self-Governing Territories Constitution Act.29

The Self-Governing Territories Constitution Act30 provided for the establishment of legislative assemblies and executive governments vested in executive councils in respect of homelands.31 With the introduction of this Act, self-governing territories were allowed to legislate for their citizens. It was also through the passage of this Act that blacks were to run their own affairs in their homelands. According to Balatseng and Van der Walt, homeland leaders could pass their own legislation only with the permission of the South African government. This demonstrates the fact that the South African government was still in control of the homelands.32 The Act also provided for the recognition and retention of the functions and powers lawfully exercised by traditional leaders in terms of the Bantu Authorities Act.33 As a result, both tribal and regional authorities were retained while territorial authorities were disestablished.34

The conditions in the homelands were not conducive to the creation of employment. Some land in the homelands was barren and not good for any kind of development. Although poverty in the homelands was a cause for concern, the homelands' leaders used public funds for their personal gains and worthless projects.35 Malnutrition was common in the communities of these homelands, not forgetting the overcrowding due to the acute shortage of land in traditional communities. Therefore, the introduction of the system of the homelands worsened the living conditions of the black people.36

4 Independent Bantustans

4.1 Transkei

The 'architects' of the independence of Transkei sought to justify their political legitimacy by producing a mixture of both democratic and tribal policies. According to Chidester, an election held in 1963 in Transkei, which led to the creation of self-government, was intended to legitimise the idea of the homeland system.37 The status of self-government in Transkei was conferred on Transkei through the passage of the Transkei Constitution Act.38 This was followed by the Status of Transkei Act,39 which granted independence to Transkei.40

The Status of Transkei Act endorsed the status, roles and functions of traditional leaders in the Legislative Assembly of the Transkei as constituted in terms of the Transkei Constitution Act.41 In other words, this Act indirectly recognised the legislative role of traditional leaders in Transkei. The majority of seats in the legislature were reserved for traditional leaders because the homeland leaders continuously enjoyed their support. These traditional leaders were given seats in the legislature to give the homeland system the flavour of a democratic mandate. The Transkei Authorities Act42 was promulgated to regulate the institution of traditional leaders. Traditional leaders in Transkei were used as 'puppets' to legitimise the notion of separate development. In this regard, it is important to note that the creators of the homeland of Transkei used traditional leaders to validate the so-called 'independence' of Transkei.43

The white authorities employed traditional leaders who participated in the Transkei government. The majority of those traditional leaders who collaborated with the white regime as early as the introduction of the Black Authorities Act44 were minor traditional leaders. For instance, the leading traditional leader of Transkei, Chief Matanzima, who later became its President, was a minor traditional leader under the authority of the Paramount Chief of the Tembu.

Chief Matanzima was declared a Paramount Chief by the South African government when conflict arose in the 1960s between Chief Matanzima and the Paramount Chief of the Tembu. Chidester noted that in 1979, when Chief Matanzima was in power in the homeland, he stripped the Paramount Chief of the Tembu of his traditional authority and had him arrested because of his anti-independence stance.45 Chief Matanzima undoubtedly supported the idea of separate development. He declared at the Transkei celebration in 1968 that:46

We believe in the sincerity of Dr Verwoerd's policy. The Transkei should cling to its ideals and continue building its nationhood as a separate entity… within the framework of separate development.

Lipton held the view that the argument of Chief Matanzima to accept independence and also the loss of South African citizenship was that partition in their own separate states was the only way blacks could win their political rights, and that the history and cultural identity of Transkei made it as well qualified for independence as neighbouring Lesotho. Many nominated traditional leaders supported this policy of Chief Matanzima. These were the people whom Lipton called its 'beneficiaries'.47 According to Matanzima the independence of Transkei was to assert the political and economic freedom of the Xhosas. Matanzima quoted Verwoerd saying that:48

We will have in the Transkei… an independent state of multi-racial character with a free economy. It will be a sovereign state that will conduct its own affairs… We feel that this will benefit the black man not only in the Transkei but also in the Republic…

4.2 Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana became a self-governing homeland in 1972 and gained its nominal independence on 6 December 1977.49 Bophuthatswana was granted independence through the enactment of the Status of Bophuthatswana Act.50 Although the Status of Bophuthatswana Act did not directly articulate and define the roles, functions and powers of traditional leaders, it did so tacitly when it recognised the Legislative Assembly of Bophuthatswana as constituted in terms of the Self-Governing Territories Constitution Act,51 which gave direct recognition52 to the authority of traditional leaders in the Legislative Assembly.53

Bophuthatswana consisted of tribal land, initially administered as a black reserve under the authority of the traditional leaders.

Later, land acquired by the South African Development Trust (SADT) was added into Bophuthatswana.54 Lawrence and Manson pointed out that Chief Mangope, who was its President until March 1994, emphasised the ethnic origin of the Tswana nation and his own position as an important and powerful traditional leader within this ethno-national entity.55 Chief Mangope claimed to be a significant paramount traditional leader of Bahurutshe and the main architect of Bophuthatswana and its transition to modernity. It was in this sense that Chief Mangope justified his control over the Bantustan structures on the basis of his status as a traditional leader of significant status. However, Lawrence and Manson explained that Chief Mangope's claim to paramountcy even over Bahurutshe lacked both validity and legitimacy.56

Chief Mangope gave the origins of Bophuthatswana mythical justifications. For instance, he emphasised the fact that the Tswana people emerged from a bed of reeds of Ntswana Tsatsi.57 Mangope believed that history,58 which placed the Tswana on the political map, began and moved through the stages of homeland development and led to the granting of Bophuthatswana's independence by the South African government in December 1977.59 When Bophuthatswana was declared an independent state, Chief Mangope stated that the event was a turning point in history.60

Bophuthatswana introduced the Bophuthatswana Traditional Authorities Act61 to regulate the institution of traditional leadership. The Act prescribed the powers, functions and roles of the traditional authorities.62 In terms of this Act, traditional leaders were also made ex-officio members of the Bophuthatswana parliament.63 As members of parliament, they were paid salaries or stipends.64 In this regard, the Bophuthatswana government almost placed all of the traditional leaders in the centre of the political bureaucratic arena. It was through this legislative measure that the independence and authority of traditional leaders were eroded and curtailed65 in Bophuthatswana. The reason for this assertion is that those traditional leaders who would not toe the line were deposed and replaced by appointed traditional leaders.66

Chief Lebone of the Bafokeng traditional community near Rustenburg defied Chief Mangope outright. He refused to hoist the Bophuthatswana flag at the local tribal offices. Chief Lebone also instructed the Bafokeng to relinquish Bophuthatswana citizenship. The Bophuthatswana government declared a state of emergency in Phokeng and ordered a Commission of Inquiry into the affairs of the Bafokeng traditional community. According to Cooper et al, about 20 headmen told the Commission that they preferred a traditional form of government under the leadership of Chief Lebone to that of the elected Bophuthatswana government.67

The activities of the Bafokeng tribal police also widened the rift between Chiefs Mangope and Lebone. The Bafokeng tribal police instituted a reign of terror on the non-Tswana and those who haboured them. These non-Tswanas were tried in Phokeng before a tribal court. Those who could not afford to pay their fines were sjambokked.68 Although non-Tswanas were unpopular with Mangope, the cruel behaviour of the tribal police moved them more closely to Chief Mangope than Chief Lebone. Mangope capitalised on the activities of the tribal police to attack Chief Lebone and his tribal police for abusing non-Tswanas and the landlords who rented them their houses.69

It also transpired that it was not only Bafokeng who wished to relinquish their Bophuthatswana citizenship. A large group of Ndebele who lived in the Hammanskraal area of Bophuthatswana led by Chief Kekana also threatened to secede. According to Cooper et al, Mangope warned them that unless they became citizens of Boputhatswana, they would be evicted from the land where they lived. The cases of Chief Lebone and Chief Kekana demonstrate that traditional leaders in Bophuthatswana ran the risk of being deposed or harassed by Chief Mangope.70

In most cases, Mangope relied on the Bophuthatswana Traditional Authorities Act, which gave him as President of Bophuthatswana the powers to recognise, appoint71 and depose traditional leaders.72 This Act was to a very large extent a replica of the Black Administration Act.73 Like the Governor-General (later State President) under the Black Administration Act,74 the President of Bophuthatswana also had the power to depose a traditional leader or headman and install his appointed traditional or acting leader. For example, in 1985, Chief Mangope invoked the provision of this Act when he deported Chief Lebone under the guise that he wanted to topple the State President of Bophuthatswana.75

It is also significant to note that both the central and local government of Bophuthatswana were firmly anchored in the institution of traditional leadership. Chief Mangope, the President of Bophuthatswana, was a traditional leader of the Bahurutshe Bo-Manyane. The Bophuthatswana government appointed traditional leaders and some of these traditional leaders were members of the Cabinet and the Bophuthatswana parliament.76 Francis posited that while some of the traditional leaders were popularly considered legitimate, some were thought to be little more than stooges.77

According to Francis, Mangope's regime was characterised by personal rule and was held together by patronage and corruption. In this regard, jobs, land and trading licenses were pieces of patronage distributed in ways that aimed to maintain and sustain political support. Political activities were banned and the opposition was severely punished, repressed and intimidated.78 This political climate made it impossible to develop strong participatory political institutions in Bophuthatswana, which was mostly an authoritarian and unpopular Bantustan.79 It alienated its inhabitants and did not create loyalty. The government of Bophuthatswana failed to achieve legitimacy or even credibility with the majority of its people or with South Africa. According to Lipton, Bophuthatswana instead became ridiculed as a Casinostan and a source of cheap labour.80 Of much importance is the fact that the Bophuthatswana government relied entirely on the support of traditional leaders to mobilise voters in the traditional authorities' areas. Suffice it to say that the political survival of Bophuthatswana revolved around support of the institution of traditional leadership.

4.3 Venda

Venda81 was the smallest of the four independent black states in South Africa. The Venda National Party (VNP) under the leadership of Chief Mphephu was the political vehicle which introduced Venda to independence.82 The VNP consisted mainly of traditionalists, particularly of traditional leaders. The VNP came into power in 1973 and was returned to power in the independence elections in 1979, largely as a result of the influence of traditional leaders and headmen.

Venda became the third homeland to gain independence from the South African government, with the introduction of the Status of Venda Act83 on 13 September 1979. Although the Venda Independent Party (VIP), the opposition party, won the overwhelming majority of elected seats in both the 1973 and 1978 elections, the ruling party, assumed power each time because the support of the VNP by the nominated traditional leaders decided the results in the National Assembly.84 The traditional leaders seemed to be used as barriers against democracy.

The Venda hegemony was centred on the institution of traditional leadership. The Venda Tribal and Regional Councils Act85 regulated the institution of traditional leadership. The traditional leaders were manipulated by Chief Mphephu to lubricate the political wheel of the Bantustan administration of Venda. It was difficult to refer to Venda as a democratic state or homeland. Chief Mphephu confirmed this proposition when he announced his intention to declare Venda a one party state because the western style of democracy was not appropriate to and compatible with an African country like Venda. This announcement justified Mphephu's sense of intolerance of democracy and political opposition.86

In 1983, Chief Mphephu became life President of the homeland. In 1984, the first post-independence elections were held in Venda. The VNP won 41 of the 45 elected seats. During the independence of Venda political activity was not tolerated and members of the opposition were detained. This earned Mphephu's administration a reputation for ruthlessness. It is important to note that since it was mainly the traditional leaders who ruled Venda, they perpetrated oppressive violations of human rights and therefore became unpopular in Venda.87 They became the enemies of the people and the servants of apartheid.

Another critical element which reduced and undermined the status and pride of traditional leaders in Venda was the dramatic resurgence of witchcraft in Venda. According to Minnaar, witchcraft cases posed a serious challenge and threats to the credibility of traditional leaders. Some of the traditional leaders were accused of working in cahoots with the witches.88 It should also be remembered that after the death of Chief Mphephu in April 1988, a considerable number of cases of witchcraft and medicine murders were reported. Some believed that Chief Mphephu made it difficult for the people to attack the witches because he was linked with witchcraft. This resulted into witch burning. When the climate of terror intensified, anyone accused of being a witch was simply killed on the spot despite protestations of innocence. Minaar observed that in some villages up to five or more accused witches were either killed or driven out of their homes each night.89

Various reasons were advanced for both the witch burnings and muti.90 Witch burnings were associated with certain political motivations, personal jealousy of individual success, and the settling of old scores. Medicine murders were commonly attributed to an individual's attempt to enhance his own personal power or to ensure success in a new business venture. Some of the traditional leaders were also accused of medicine murders.

These accusations destroyed the credibility of the institution of traditional leadership in Venda. Although not all of the traditional leaders were accused of witchcraft, they were no longer seen as the guardians and protectors of their subjects but as 'criminals' who murdered people for their material or political gain. As a result, traditional authorities lost a great deal of respect in the eyes of the Venda people.91 The traditional leaders also lost credibility in the eyes of their people because they were seen as the faithful supporters of the homeland system and administration.

4.4 Ciskei

The territory known as Ciskei was declared a self-governing area by the South African government in 1972 and its territorial authority was replaced with a Legislative Assembly.92 The early independence years of Ciskei were marred with a plethora of challenges. For example, the Transkei government vehemently opposed the independence of Ciskei. Chief Matanzima pointed out that the Ciskei independence contravened the Promotion of Black Self-Government Act. As a result, Chief Matanzima warned Chief Sebe that the march of time would catch up with him. Chief Matanzima produced a petition document signed in 1976 by 12 Ciskei traditional leaders who were in favour of the incorporation of Ciskei into Transkei. Cooper et al cited Matanzima as saying that:93

The Ciskei celebrations (and independence) were the culmination of a systematic defiance of the natural leaders of the Ciskei now scared of Chief Sebe's wrath.

Shortly before independence, Chief Sebe announced what was termed a 'Package Deal' agreed upon between himself and the then Minister of Co-operation and Development, Koornhof. According to the deal, the envisaged independence of Ciskei was to be different from that negotiated by Transkei, Bophuthatswana and Venda. The 'Package Deal' inter alia stipulated that the Ciskeians would retain their identity and nationality while at the same time not surrendering their South African citizenship.94 Subsequently, the Status of Ciskei Act95 was promulgated and Ciskei was granted independence on December 1980.

On 5 December 1980, the National Assembly of Ciskei chose Chief Sebe as the Executive President. Chief Sebe appointed a Vice President and eleven members of the Cabinet. The National Assembly consisted of 22 elected members, 33 nominated traditional leaders, one Paramount Chief and five members nominated by the President for their special knowledge, qualifications and experience.96 Chief Sebe declared his intentions to support the idea of separate development by stating that the separate development of nations had always been a characteristic of traditional African life.97 Sebe saw the homeland system as a way to re-establish his people's own traditions and customs both religiously and politically and not as a product of apartheid.98

Chief Sebe was a commoner. He made all the necessary arrangements for his installation as a traditional leader. He declared himself a traditional leader in order to legitimise and justify his traditional and political power. Sebe stated clearly at his own installation ceremony that:99

The Chief was the central symbol of national honour and pride, the custodian of all those tribal and national customs and practices that are dear and sacred to the tribe.

Ciskei's lesson is of great historical importance in the sense that it shows how the institution of traditional leadership was re-created by the apartheid government. It is therefore difficult to refer to pristine institutions of traditional leadership under these political circumstances. In fact, the traditional leaders and not the people supported the independence of Ciskei. It is evident that both the Ciskei parliament and the Cabinet were staffed with traditional leaders. Suffice it to say that the traditional leaders in Ciskei including Chief Sebe manipulated the institution of traditional leadership to justify the concept of the homeland system and Ciskei nationality.

5 The demise of the Bantustans and beyond

5.1 A call for the transformation of traditional leadership

The introduction of multi-party democracy brought the issue of traditional authorities, their history and roles in the new South Africa under a spotlight. Ntsebeza argued that the recognition of the hereditary institution of traditional leadership in the South African Constitution, while at the same time enshrining liberal democratic principles based on representative government in the same Constitution, is a fundamental contradiction. According to Ntsebeza, the two cannot exist at the same time for the simple reason that traditional leaders are born to the throne and not elected by the people.100

Therefore Ntsebeza asserted that the recognition of the institution of traditional leadership compromised the democratic project that the post-apartheid government had committed itself to. More surprisingly, he asked why it was that an organisation such as the African National Congress (ANC), which fought for a democratic unitary state after apartheid, would embrace the institution of traditional leadership, which had a notorious record under apartheid.101

The debate on the future role of traditional leaders in a democratic South Africa led to the emergence of the schools of modernists and traditionalists respectively. According to Keulder, the modernists call for a major transformation of the institution of traditional leaders to meet the requirements of a modern, non-sexist and non-racial democracy.102

The modernists were primarily concerned with gender equality and reviewed the institution of traditional leaders as the basis of rural patriarchy. On the other hand, the traditionalists believed that the institution of traditional leaders was at the heart of rural governance, political stability and rural development. They further argued that a traditional leader acted as a symbol of unity to maintain peace, preserve customs and culture, resolve disputes and faction fights, allocate land etc.

For the institution of traditional leadership, despite past policies and practices, enjoyed substantial support and legitimacy.103 However, as Keulder observed both the modernists and traditionalists agreed that the institution of traditional leadership, its composition, functions and legal manifestations should change in order to adapt to the changes in the new constitutional, social and political environments of post-apartheid South Africa.104

6 Transitional dispensation: 1993 to 2003

The constitutional transition was preceded by protracted negotiations which were aimed at creating a new order where all South Africans would be entitled to equality before the law. In terms of section 235 of the Interim Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, legislation dealing with the administration of justice, traditional leadership and governance vested with the President of the Republic of South Africa in 1994. Some of these functions were later assigned to the competent authorities within the jurisdiction of different ministries and provinces.

All the pieces of legislation from the homelands were assigned to the President and later re-assigned to the new provinces. Under section 235(8) of the Interim Constitution, the President was assigned and could re-assigned the administration of certain laws to a competent authority within the jurisdiction of the government of a province. Any such assignment would be regarded as having been made under the similar transitional arrangements in the 1996 Constitution.

Legislation dealing with the administration of justice such as the Black Administration Act105 and certain legislation of the self-governing territories and the so-called independent states, for example, the Transkei Authorities Act,106 the Regional Authorities Courts Act,107 The Chiefs Court Act,108 the Bophuthatswana Traditional Courts Act,109 the Venda Traditional Leaders Administration Proclamation 29 of 1991 etc were temporarily assigned to the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development. The 1996 Constitution provides for the continuation of both pre-1994 legislation and various pieces of legislation issued in terms of the Interim Constitution including the old order legislation passed before 27 April by the homeland governments.110

7 1993 Constitutional provisions

7.1 1993 Constitutional dispensation

In 1994, South Africa entered a new constitutional dispensation based on democracy, equality, fundamental rights, the promotion of national unity and reconciliation. The new constitutional dispensation culminated in the Interim Constitution.111 The institution, status and role of traditional leadership according to indigenous law were recognised and protected in the Interim Constitution in accordance with the Constitutional Principle VIII. The roles and functions of traditional leadership were not defined in this Principle.

In the Interim Constitution, traditional authorities and indigenous and customary law were recognised and provision was made for certain functions of traditional leadership at central and provincial government levels. Chapter 11 provided for the recognition of all existing traditional leaders and customary law. These constitutional provisions were as follows:112

(1) A traditional authority, which observes a system of indigenous law and is recognised by law immediately before the commencement of this Constitution, shall continue as such an authority and continue to exercise and perform the powers and functions vested in it in accordance with the applicable laws and customs, subject to any amendment or repeal of such laws and customs by a competent authority.

(2) Indigenous law shall be subject to regulation by law.

These Constitutional provisions were a victory for traditional leaders in the new democratic South Africa. Although Chapter 11 recognised and protected the institution, status and role of traditional leadership according to customary law, recognition of customary law and traditional leadership was subject to the supremacy of the Constitution and the Chapter on the Bill of Rights. Section 160(3)(b) of the Interim Constitution provided that where applicable a provincial Constitution may provide for the institution, role, authority and status of a traditional monarch in the province and would make provision for the Zulu monarch in case of KwaZulu-Natal.

In view of this constitutional arrangement, it is unsurprising that the traditional leaders negotiated for the type of the Constitution that would respect and uphold their aspirations and powers. The Interim Constitution provided for ex-officio status of the traditional leaders in local government structures. This status was recognised by the Constitutional Court in ANC v Minister of Local Government and Housing, Kwazulu-Natal.113 The Interim Constitution further provided a function for traditional leadership at the local level of government.114 It also provided for a National Council of Traditional Leaders at national level and a Provincial House of Traditional Leaders at provincial level.115 Initially, the six Provincial Houses of the traditional leaders were established in terms of the legislation enacted by the provincial legislatures concerned.116 These constitutional provisions were once again a victory for traditional leaders in the new democratic South Africa.117

CONTRALESA commented:

[T]he democratic dispensation developed in South Africa should be developed in a manner which reflects the values of the whole community it serves. The Constitution should therefore mirror the soul of the nation and it must include all the aspirations, beliefs and values. The institutions and role of traditional leaders, which have been in existence as longer than a liberal democracy in the West are to be treated with respect and accordingly be integrated within the structures of national, provincial and local government.

7.2 1996 Constitutional settlement

The 1996 Constitution is the supreme law of the country. Section 2 of the Constitution provides that the Constitution is the supreme law of the Republic. Law or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid and the obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled. Section 2 must be read with section 1 of the Constitution, which also pronounces the supremacy of the Constitution and the rule of law. If all of these principles are read together, one principle is indisputable: the Constitution is supreme and everything and everybody is subject to it.

Everything and everybody – all law and conduct, all traditions, customs, perceptions, customary rules and the system of traditional rule are influenced and qualified by the Constitution. The institution of traditional leadership is obliged to ensure full compliance with the core constitutional values of human dignity, equality, non-sexism, human rights and freedom. The Constitutional Court confirmed the supremacy of the Constitution in S v Thebus,118 where it held that since the advent of constitutional democracy, all law must conform to the command of the supreme law, the Constitution, from which all law derives its legitimacy, force and validity.

Thus, any law which precedes the coming into force of the Constitution remains binding and valid only to the extent of its constitutional consistency. The 1996 Constitution recognises the institution of traditional leadership. This recognition is housed in section 211(1), (2) and (3) of the Constitution.119

(1) The institution, status and role of traditional leadership, according to customary law, are recognised, subject to the Constitution.

(2) A traditional authority that observes a system of customary law may function subject to any applicable legislation and customs, which includes amendments to, or repeal of, that legislation or those customs.

(3) The courts must apply customary law when that law is applicable, subject to the Constitution and any legislation that specifically deals with customary law.

Traditional leadership is recognised subject to the 1996 Constitution and is required to be compatible with the Constitution. This constitutional provision requires the traditional leadership to change its own rules and practices not to be in conflict with the Bill of Rights. Discrimination on the ground of sex or gender would for example not be allowed and more inclusive participation in the decision-making processes will be considered.120 The 1996 Constitution is a legal effort to recreate a new and democratic institution of traditional leadership in South Africa.121

8 Milieu of legislation and public policy

8.1 Overview

In the first ten years of democracy, the post-apartheid parliament of South Africa enacted a plethora of legislation and issued government policy intended to transform and democratise the institution of traditional leadership and the system of land administration and use. Various pieces of legislation and policy are discussed hereunder.

8.2 White Paper on Traditional Leadership and Governance

The White Paper on Traditional Leadership and Governance was a product of approximately four phases, namely research, debates, extensive consultation and discussions.122 These discussions led to the production of a Draft White Paper where preliminary policy positions were outlined. The fourth phase witnessed the launch of the White Paper on Traditional Leadership and Governance that paved the way for the drafting of the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 41 of 2003 concerning the institution of traditional leadership.123

The White Paper was a culmination of a long process wherein the country engaged in a dialogue regarding the role and place of the institution of traditional leadership in contemporary South Africa as a democratic state. The key objectives of the White Paper centred on the principle of creating an institution which is democratic, representative, transparent and accountable to the traditional communities.

9 Selected pieces of legislation

The Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act124 (hereinafter referred to as the 'Framework Act') and the Communal Lands Rights Act125 (hereinafter referred as the 'CLARA') are intended among many other things to revamp and resuscitate the powers and functions of traditional leaders enjoyed under the notorious Black Authorities Act126 and various pieces of homelands' legislation. For example, the Framework Act endorses tribal authorities, which were set up in terms of the Black Authorities Act as a foundation for establishing the traditional councils,127 while the Communal Land Rights Act128 recognises these councils as having the authority to administer and allocate land in the traditional authorities' areas.129 The Framework Act directs that local houses of traditional leaders must be established for the area of jurisdiction of a district or metropolitan municipality where more than one senior traditional leader exists.

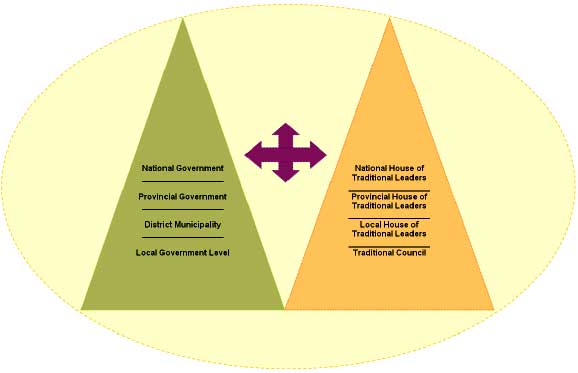

The Framework Act and various pieces of both the national and provincial legislation also provide for the establishment, composition, recognition and roles of respective provincial houses of traditional leaders and a national house of traditional leaders. These houses of traditional leaders are established horizontally in relation to each sphere of government in order to engender the principle of co-operative government. The following diagram illustrates the horizontal pattern of these houses in relation to each sphere of government:130

Other legislative initiatives affecting traditional leadership include amendments of the National House of Traditional Leaders Act,131 various pieces of the provincial legislation of the North-West Province, Mpumalanga, Limpopo, Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal,132 the Remuneration of Public Office Bearers Act133 and finalisation of the Traditional Courts Bill, 2008.134

The above legislative initiatives demonstrate the government's intention to develop and reform the institution of traditional leadership, indigenous customs and practices considered to be in conflict with the democratic values entrenched in the Constitution. According to De Beer, the passing of the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act135left nobody in any doubt about the parliament's intention to eradicate customs and practices perceived to be in conflict with the gender equality principle in the Constitution.136

10 Conclusion

In view of the preceding discussion, it is evident that both the apartheid and homelands' legislative frameworks altered the roles, powers and functions of traditional leaders. Moreover, those various pieces of legislation eroded the foundation upon which the institution of traditional leadership was founded and established. Just as the successive colonial and apartheid governments were ready to deal the institution of traditional leadership a mortal blow, the governments of the TBVC states did not hesitate to take the attack forward.

Despite the fact that the political leadership of the TBVC states promised traditional leaders 'bread' and 'butter' before they could attain 'independence' from South Africa, it was the same political leadership which eroded and undermined the powers and roles of the traditional leaders and exploited them to the fullest while they (the 'Presidents' of the TBVC states) were exploited by the successive apartheid governments. With the advent of the constitutional democracy in South Africa, the institution of traditional leadership is required to re-define itself within the framework of a democratic dispensation. The government has been in the forefront of transforming the institution of traditional leadership for about 15 years, but it seems that the transformation has not got off the ground yet.

This is a new ball game altogether. Whether or not the present government will completely democratise and transform the institution of traditional leadership is yet to be seen. As Donkers and Murray note, if the traditional leaders are to assume a dignified and just role in the new South Africa, they will have to deal with the problems facing them within the constitutional and legislative framework, for they and they alone hold the key to transforming the challenges they face into prospects, and those prospects into a reality within the confines of a constitutional democracy.137

Bibliography

Balatseng and Van der Walt "History of Traditional Authorities"

Balatseng D and Van der Walt A "The History of Traditional Authorities in the North-West" (Unpublished paper delivered at the Workshop on Culture, Religion and Fundamental Rights 26-27 November 1998 Mafikeng) [ Links ]

Beinart Twentieth Century South Africa

Beinart W Twentieth Century South Africa (Oxford University Press London 2001) [ Links ]

Chidester Religions

Chidester B Religions of Southern Africa (Routledge London 1992) [ Links ]

Cooper C et al Survey of Race Relations of Southern Africa (Johannesburg 1984) [ Links ]

Cooper et al Survey

Cooper C et al Survey of Race Relations of Southern Africa (South African Institute of Race Relations Johannesburg 1985) [ Links ]

Cope South Africa

Cope J South Africa (Benn London 1965) [ Links ]

De Beer "South African Constitution"

De Beer FC "South African Constitution, Gender Equality and Succession to Traditional Leadership: A Venda Case Study" in Hinz MO (ed) The Shade of New Leaves: Governance in Traditional Authority: A Southern African Perspective (Lit Verlag Berlin 2006) [ Links ]

De Klerk The Man of His Time

De Klerk FW The Man of His Time (Human & Rousseau Johannesburg 1991) [ Links ]

Deane 2005 Fundamina

Deane T "Understanding the Need of Anti-Discrimination Legislation in South Africa" 2005 Fundamina 1-3 [ Links ]

Donkers and Murray "Prospects and Problems"

Donkers A and Murray R "Prospects and Problems Facing Traditional Leaders in South Africa" in De Villiers B (ed) The Rights of Indigenous People: A Quest for Coexistence (HSRC Pretoria 1997) [ Links ]

Francis 2002 JSAS

Francis E "Rural Livelihoods Institutions and Vulnerability in the North-West Province, South Africa" 2002 Journal of Southern African Studies 531-550 [ Links ]

Gobodo-Madikizela A Human Being Died

Gobodo-Madikizela P A Human Being Died That Night: A Story of Forgiveness (David Philip Cape Town 2004) [ Links ]

Keulder Traditional Leaders

Keulder C Traditional Leaders and Local Government in Africa: Lessons for South Africa (HSRC Publishers Pretoria 1998) [ Links ]

Khunou Legal History

Khunou SF A Legal History of Traditional Leadership in South Africa, Botswana and Lesotho (LLD-thesis NWU 2007) [ Links ]

Lawrence and Manson 1994 JSAS

Lawrence M and Manson A "The Dog of the Boers: The Rise and the Fall of Mangope in Bophuthatswana" 1994 Journal of Southern African Studies 447-461 [ Links ]

Liebenberg "National Party"

Liebenberg BJ "The National Party in Power 1948-1961" in Miller J (ed) Five Hundred Years: A History of South Africa (Academica Pretoria 1969) [ Links ]

Lipton Capitalism

Lipton M Capitalism and Apartheid: South Africa 1910-1986 (Wildwood House Cape Town 1986) [ Links ]

Matanzima Independence

Matanzima KD Independence My Way (Foreign Affairs Association Pretoria 1976) [ Links ]

Ntsebeza Democracy

Ntsebeza L Democracy Compromised: Chiefs and the Politics of Land in South Africa (HSRC Press Cape Town 2005) [ Links ]

Olivier "Recent Developments"

Olivier NJJ "Recent Developments in Respect of Policy and Regulatory Frameworks for Traditional Leadership in South Africa at Both National and Provincial Level" in Hinz MO (ed) The Shade of New Leaves: Governance in Traditional Authority: A Southern African Perspective (Lit Verlag Berlin 2006) [ Links ]

Olivier NJJ "Traditional Leadership"

Olivier NJJ "Traditional Leadership and Institutions" in Joubert WA (eds) The Law of South Africa: Indigenous Law (LexisNexis Butterworths Durban 2004) [ Links ]

Sharp "Two Worlds"

Sharp J "Two Worlds in One Country: 'First World' and 'Third World' in South Africa" in Boonzaier E and Sharp J (eds) in South African Keywords: The Uses and Abuses of Political Concepts (David Phillip Johannesburg 1988) [ Links ]

South Africa Debates of the National Assembly

South Africa Debates of the National Assembly: Sixth Session-Eleven Parliament (Cape Town 1998) [ Links ]

Spiegel and Boonzaier "Promoting Tradition"

Spiegel A and Boonzaier E "Promoting Tradition: Images of the South African Past" in Boonzaier E and Sharp J (eds) in South African Keywords: The Uses and Abuses of Political Concepts (David Phillip Johannesburg 1988) [ Links ]

TARG Report on Conference Documentation

TARG Report on Conference Documentation The Administrative and Legal Position of Traditional Authorities in South Africa and their Contribution to the Implementation of the Reconstruction Development Programme Vol X (Potchefstroom 1996) [ Links ]

TARG Report on Politico-Historical Background

TARG Report on Politico-Historical Background The Administrative and Legal Position of Traditional Authorities in South Africa and their Contribution to the Implementation of the Reconstruction Development Programme Vol III (Potchefstroom 1996) [ Links ]

Thornton "Culture"

Thornton R "Culture: A Contemporary Definition" in Boonzaier E and Sharp J (eds) in South African Keywords: The Uses and Abuses of Political Concepts (David Phillip Johannesburg 1988) [ Links ]

Vorster "Constitution"

Vorster MP "The Constitution of the Republic of Transkei" in Voster (eds) The Constitutions of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei (Butterworths Durban 1995) [ Links ]

Walter War against Capitalism

Walter EW South Africa's War against Capitalism (Juta Cape Town 1990) [ Links ]

West "Confusing Categories"

West M "Confusing Categories: Population Groups, National States and Citizenship" in Boonzaier E and Sharp J (eds) in South African Keywords: The Uses and Abuses of Political Concepts (David Phillip Johannesburg 1988) [ Links ]

William 2004 JMAS

William JM "Leading from Behind: Democratic Consolidation and the Chieftaincy in South Africa" 2004 Journal of Modern African Studies 113-136 [ Links ]

Register of legislation and government documents

Black Administration Act 38 of 1927

Black Authorities Act 68 of 1951

Black Land Act 27 of 1913

Bophuthatswana Traditional Authorities Act 23 of 1978

Chief Court Act 6 of 1983

Communal Land Rights Act 11 of 2004

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996

Constitution of the Republic of Ciskei Act 20 of 1981

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 200 of 1993

Constitution of the Republic of Venda Act 9 of 1979

Eastern Cape House of Traditional Leaders Act 1 of 1996

Free State House of Traditional Leaders Act 6 of 1994

House of Traditional Leaders Act 10 of 1998

KwaZulu-Natal Act on the House of Traditional Leaders Act 7 of 1994

Mpumalanga House of Traditional Leaders Act 4 of 1994

National House of Traditional Leaders Amendment Bill 2008

National States Citizenship Act 26 of 1970

Northern Province House of Traditional Leaders Act 6 of 1994

North-West Provincial House of Traditional Leaders Act 12 of 1994

Promotion of Black Self-Government Act 46 of 1959

Promotion of Equality and Prevention on Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000

Regional Authorities Act 13 of 1982

Remuneration of Public Office Bearers Act 20 of 1998

Republic of Bophuthatswana Constitution Act 18 of 1977

Republic of Transkei Constitution Act 3 1976

Self-Governing Territories Constitution Act 21 of 1971

Status of Bophuthatswana Act 89 of 1977

Status of Ciskei Act 110 of 1980

Status of Transkei Act 100 of 1976

Status of Venda Act 107 of 1979

Traditional Courts Act 29 of 1991

Traditional Courts Act 29 of 1979

Traditional Courts Bill B15-2008

Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 41 of 2003

Transkei Authorities Act 4 of 1965

Transkei Constitution Act 48 of 1963

Tribal and Regional Councils Act 10 of 1975

Trust and Land Act 18 of 1936

White Paper on Traditional Leadership and Governance 2003

Register of court cases

ANC v Minister of Local Government and Housing, Kwazulu-Natal 1998 (3) SA 1 (CC)

Buthelezi v Minister of Bantu Administration and Another 1961 (3) SA 760 (CLD)

Chief Pilane v Chief Linchwe 1995 (4) SA 686 (B

Deputy Minister of Tribal Authorities v Kekana 1983 (3) SA 492 (B)

Government of Bophuthatswana v Segale 1990 (1) SA 434 (BA)

In Ex Parte Chairperson of the Constitutional Assembly: In the Certification of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 (4) SA 744 (CC)

Mabe v Minister for Native Affairs 1958 (2) SA TPD

Molotlegi and Another v President of Bophuthatswana and Another 1989 (3) SA 119 (B)

Mosome v Makapan NO and Another 1986 (2) SA 44 (B)

S v Banda and Others (1989-1990) BLR

S v Molubi 1988 (2) SA 576 (B)

S v Thebus and Another 2003 (10) BCLR 1100 (CC)

Saliwa v Minister of Native Affairs 1956 (2) SA (AD)

Segale v Bophuthatswana Government 1987 (3) SA 237 (B)

Shulubana and Others v Nwamitwa and Others 2008 (9) BCLR 914 (CC)

Sibasa v Ratsialingwa and Another 1947 (4) 369 (TPD)

Tshivhase Royal Council and Another v Tshivhase and Another 1990 (3) SA 828 (V)

Register of internet sources

Codman 1986 www.nu.ac.za/

Codman C 1986 Gazankulu: Land of Refuge and Relocation Indicator South Africa www.nu.ac.za/indicator/default.htm [date of use 10 December 2009] [ Links ]

Minnaar 1991 www.nu.ac.za/

Minnaar A 1991 The Witches of Venda: Politics in Magic Portions Indicator South Africawww.nu.ac.za/indicator/default.htm [date of use 10 December 2009] [ Links ]

Toolkit 2009 www.cogta.gov.za/

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs 2009 Legislation Impacting on the Institution of Traditional Leadership www.cogta.gov.za/index.php [date of use 10 December 2009] [ Links ]

Zinge 1984 www.nu.ac.za/

Zinge J 1984 Will Faith in Free Market for Forces Solve Ciskei's Development Crisis Indicator South Africa Indicator South Africa www.nu.ac.za/indicator/default.htm [date of use 10 December 2009] [ Links ]

List of abbreviations

ch chapter(s)

par paragraph(s)

reg regulation(s)

s section(s)

NP National Party

SADT South African Developme nt Trust

VNP Venda National Party

VIP Venda Independent Party

ANC African National Congress

CLARA Communal Lands Rights Act

TA Transkei Assembly

1 Gobodo-Madikizela A Human Being Died 144. The ideology of apartheid was laced with different terminologies such as multinational development, plural democracy and a confederation of independent nations or even good neighbourliness. See also Deane 2005 Fundamina 1-3, where she stated that the aim of apartheid was to maintain white domination and extended racial segregation. Whites invented apartheid as a means to cement their power over the economic, political and social systems. See also Liebenberg "National Party" 481. According to Liebenberg, the apartheid policy was not a new one. It was an old policy, which could be traced back to the time when Jan van Riebeeck at the Cape planted a lane of wild almond trees to indicate the boundary between the Khoikhoi area and the white area. However, the policy applied after 1948 was different from the pre-1948 policy. The difference lies in the ruthlessness of the 1948 policy which was implemented in South Africa. The 1948 policy was also enforced by the government with the aid of legislation.

2 For more information on the issue of race, see West "Confusing Categories" 100-101. West asserted that the system of race classification in South Africa was often referred to as "race classification". As West further noted the opponents and supporters of this classification regularly refer uncritically to race as the guiding principle. They argued that the system divided South Africans on the basis of colour and other physical features. According to West, classification is determined by several factors, which include inter alia appearance, descent, acceptance, language, behaviour and so on. It is on the basis of this account that West argued strongly that race classification was not based exclusively on the physical features of race.

3 For more information on culture, see Thornton "Culture" 19. Thornton asserted that the idea of "culture" has frequently been fused with that of society and had been used interchangeably to refer to a general social state of affairs or to a more or less clearly recognisable group of people. Ideas about 'cultures' and 'organisms' influenced each other in the development of theories of evolution, both cultural and biological. Sometimes people have argued that cultures are like organisms. Unfortunately for Thornton these ideas were confused and contributed nothing to a useful understanding of culture.

4 The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 200 of 1993. Hereinafter referred to as the Interim Constitution.

5 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996. Hereinafter referred to as the Constitution.

6 Khunou Legal History 2007 Z. See also the case of Shulubana v Nwamitwa 2008 (9) BCLR 914 (CC) 933, where the Constitutional Court held that the traditional authorities' power is the high-water-mark of any power within the traditional community on matters of succession. The court held further that no other body in the community has more power than traditional authorities.

7 Spiegel and Boonzaier "Promoting Tradition" 49. The word 'chief' was used differently during the colonial and apartheid periods to refer to a leader of a traditional community. A 'Chief' was also known as Kaptein, traditional authority, native leader, Bantu leader, African ruler, etc. However, under a new constitutional dispensation, the word 'chief' is no longer used and has been replaced by the words 'traditional leader'. The words 'Kgosi', 'Morena', 'Inkosi', 'Hosi', etc are also used depending on the language spoken by a particular traditional group.

8 Ntsebeza Democracy Compromised 17.

9 Ntsebeza (n 9) 17.

10 Act 38 of 1927.

11 Spiegel and Boonzaier (n 7) 49.

12 Black Land Act 27 of 1913. Hereafter referred to as the 1913 Land Act. Through this Act, the majority of black people were deprived of their land. The traditional communities and their leaders lost vast tracks of land. This piece of legislation also restricted blacks from entering into agreement or transaction for the purchase, lease or the acquisition of land from whites. This meant that traditional leaders and members of their communities could not buy or acquire land from the whites for their communities. See also Cope South Africa 18.

13 Act 18 of 1936. The Native Trust Land Act had the effect of reserving certain land in traditional communities for occupation by black people in traditional authorities' areas. With the introduction of this Act, more acres of land were added to the reserves thus making it possible for black communities to secure 13% of land.

14 Act 46 of 1959. The purpose of Act 46 of 1959 was among many other things intended to provide for the gradual development of self-governing black national units and for direct consultation between the government of the Union of South Africa and the national units in regard to matters affecting the interests of such national units. According to the Preamble of Act 46 of 1959, it was expedient to develop and extend the black system of government and to assign further powers, functions and duties to regional and territorial authorities. See also Beinart Twentieth Century South Africa 146. Beinart submitted that apartheid in its broader conception had increasingly become associated with Verwoerd. He further argued that Verwoerd dominated policy towards blacks. He described Verwoerd as one of the ideologues who moulded notions of separate cultures, nations and homelands.

15 S 2(1) of Act 46 of 1959.

16 Act 46 of 1959. The Act described the 'black population' as a heterogeneous group.

17 See the Preamble of the Promotion of Black Self-Governing Act 46 of 1959.

18 De Klerk The Man of His Time 8-9. Verwoerd is quoted by De Klerk, describing his viewpoint of the homelands system, as follows: "If we treat the Coloured, the Indian in such and such a manner, how will the Bantu Chief react? Will he not demand the same rights since he will not differentiate between one dark skin from another. And if he is granted those rights, will it not mean the end of our western civilization? Is it therefore not preferable that all persons of colour should be treated as races separate from the white, thereby eliminating all possibility of overthrowing western culture and western institution in South Africa? I say that if it is within the power of the Bantu, and if the territories in which he now lives can develop to full independence, they will develop in that way."

19 The inhabitants of TBVC states were regarded as the citizens of their respective territories. As a consequence, they were stripped of their citizenship of South Africa.

20 There were ten Bantustans which were created by the apartheid regime in South Africa. These were KwaZulu, Qwaqwa, KwaNdebele, KaNgwane, Lebowa, Gazankulu, Venda, Ciskei, Transkei and Bophuthatswana. The Self-Governing Territories Constitution Act 21 of 1971 made provision for the establishment of self-governing territories. Unlike the states of Bophuthatswana, Transkei, Ciskei and Venda that opted for independence, the leaders of these territories had not accepted the idea of independence. These self-governing national units consisted of different and separate ethnic groups on the basis of language and culture, namely KaNgwane, Lebowa, KwaNdebele, Gazankulu, KwaZulu, and QwaQwa.

21 Walter War against Capitalism 23.

22 Act 26 of 1970.

23 S 2 of Act 26 of 1970.

24 S 5 of Act 26 of 1970.

25 Act 26 of 1970. Finally, in 1970, all black people in South Africa were stripped of their citizenship.

26 Chidester Religions 204. Chidester confirmed this new order of separate development when he quoted one of the Ministers of Bantu Administration, Mulder, when he said that: "If our policy is taken to its logical conclusion as far as the Bantu people are concerned, there will be no one black with South African citizenship."

27 Chidester (n 26) 205. Chidester further cited the Minister of Native Affairs, Jansen saying: "We are of the opinion that the solidarity of the tribes should be preserved and that they should develop along the lines of their own national character and tradition."

28 It was through the policy of apartheid that the traditional communities and families were disintegrated. Furthermore, members of the same traditional community were separated and fragmented. The whole notion of apartheid was the antithesis of the notion of unity and cohesion among the black people of South Africa. For example, in 1963 Transkei received its self-government status. This was an achievement on the part of the apartheid government in breaking the unity and cohesion among the black of South Africa.

29 See Transkei Constitution Act 48 of 1963. The Transkei Constitution established a unicameral legislative assembly consisting of 109 members, of whom 45 were directly elected by all Transkeian citizens and 65 ex-officio members comprised Paramount Chief and other traditional leaders. The Constitution further made provision for the granting of Transkeian citizenship as well as national symbols such as a flag and anthem and coat of arms. See also in this regard Vorster "Constitution" 25.

30 Act 21 of 1971.

31 S 1 of Act 21 of 1971. TARG Report on Conference Documentation 24. TARG team stated that the promulgation of Act 21 of 1971 was a step further on the part of the apartheid government to realise the goal of denying the black people any claim in the government of South Africa. According to TARG, blacks had to govern themselves in small patches of land far from industrial and commercial sites. Traditional leaders in these homelands also played a very crucial role in assisting the government to achieve its goal of entrenching apartheid.

32 Balatseng and Van der Walt "History of Traditional Authorities" 8.

33 S 11 of Act 21 of 1971.

34 S 12 and 13 of Act 21 of 1971.

35 South Africa Debates of the National Assembly 782. Commenting on the Economic Co-operation and Promotion Loan Fund Amendment Bill, Dalling ANC MP stated that the so-called homelands' prime and only exports were the sweat and the toil of their people who were forced into a cruel system of contract and migratory labour. He went on to say that: "Perhaps it is important to reflect on how much of the money handed over to the petty dictatorships of the TBVC territories was wasted and not used for beneficial purposes. I remember for instance, Lennox Sebe built the extravagant international airport, which during the entire life of the state of Ciskei never saw the landing of any aircraft from any country other than from South Africa. President Sebe also purchased two – not one, but two jets for his planned Ciskei Airline. This cost several million and stood idle on the airport apron for years. Mr Mangope and Chief Matanzima used South African money to build their palaces, to stock their farms and so on."

36 The black inhabitants of the homelands were thoroughly subjected to untold suffering and poor socio-economic conditions. For instance, the majority of them had no access to electricity, clean water, sanitation and so forth. However, in homelands such as Bophuthatswana there were a considerable number of developmental projects, which signified economic growth and progress. Some of the residents of Bophuthatswana had access to clean water, electricity and sanitation. For more information on the development of the homelands, see Sharp "Two Worlds" 128. Sharp argued that development was a crucial aspect of separate development or apartheid. He further argued that as the racial policy unfolded, the development policies of the state were continually adapted, development priorities re-defined, and development goals altered accordingly. The question is: to what extent did racial policy or apartheid influence development in the homelands? If racial policy or apartheid indeed influenced development in the homelands as Sharp argued, why was apartheid widely condemned by both the black majority and international communities? The issue of development in this context remains a moot point.

37 Chidester (n 26) 207-208.

38 Act 48 of 1963.

39 Act 100 of 1976.

40 See the Republic of Transkei Constitution Act 3 of 1976. Transkei adopted this Constitution when independence was granted to it by SA in 1976. S 22 of Act 3 of 1976 provided inter alia for the representation of traditional leaders in the National Assembly. The National Assembly consisted of the Paramount Chiefs and 72 traditional leaders who represented the districts of Transkei.

41 Act 48 of 1963.

42 Act 4 of 1965. This Act dealt inter alia with matters pertaining to the appointment, recognition, suspension and deposition of traditional leaders in Transkei. In Matanzima v Holomisa 1992 (3) SA 876 (TK-CD), the court dealt with the matter concerning the suspension of a Paramount Chief in terms of s 47 (1)(b) of the Transkei Authorities Act 4 of 1965. The court found that the suspension affected the interests and the reputation of the suspended Chief and secondly there was non-compliance with the audi alteram partem maxim. The court further stated that the position of the Paramount Chief and the tribal authority are institutions which give effect to tribal custom and hierarchy and play an important role in the day-to-day administration of the area and in the lives of the Transkeian citizens. The mere existence of the tribal authority and the position of Paramount Chief, Chiefs and headmen is evidence of the tribal customary ways of all Transkeians. The position of Paramount Chief is hereditable and the suspension of a Paramount Chief must be seen against this background.

43 Chidester (n 26) 207.

44 Act 68 of 1951.

45 Chidester (n 26) 207.

46 Chidester (n 26) 208.

47 Lipton Capitalism 298. According to Lipton, the Matanzima brothers also supported Matanzima's policy. They were rewarded by the Transkei Assembly (TA) for their faithful service in the development of Transkei by granting them valuable farms in the land transferred by SA to Transkei.

48 Matanzima Independence 85.

49 See the Republic of Bophuthatswana Constitution Act 18 of 1977.