Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.24 n.1 Johannesburg 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v24i1.1200

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Organisational ethics context factors in a public energy utility company: A millennial view

Reneilwe M. Matabologa; Aden-Paul Flotman

Department of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, College of Economic and Management Science, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Millennials have become the largest age cohort in the modern world of work. Understanding the phenomenological experiences of millennials may be the key to facilitating more ethical organisational cultures

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The aim of this article is to explore the lived, working experiences of millennials' organisational ethics contexts factors as predisposed by ethical leadership in an organisation in the energy sector

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: An extensive body of research exists concerning the statistical relationship between ethical leadership, ethical culture, and workplace ethics climates. However, less explored is qualitative studies regarding millennials' work experiences of organisational ethics context factors.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: A qualitative research design was selected. Purposive and convenience sampling were utilised. The sample included eight millennials, and face-to-face interviews were used for data collection. Data were analysed by means of content analysis.

MAIN FINDINGS: The findings suggest an ambivalent and paradoxical split in how millennials experience the ethical context factors in the participating organisation

PRACTICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The study has implications for the type of leadership styles that should be considered when engaging with millennials. Top human resource management could use the results to create a working environment that actively fosters psychological attachment, satisfaction, and boosts employee commitment.

CONTRIBUTION OR VALUE ADDED: Expanding and enhancing the comprehension of how ethical leadership contributes to the theory of ethical leadership in the work context.

Keywords: co-worker; cohesion; ethical climate, ethical leadership; millennials; organisational culture; organisational justice.

Introduction

Organisational ethics context factors or ethical context are characterised by a strong emphasis on ethicality (Komalasari et al. 2019; Trevino, Butterfield & McCabe 1998), and as such, is a topic that has received a great deal of attention during the past 20 years (Rachele et al. 2013; Rashid, Sambasivan & Johari 2003; Suh, Shim & Button 2018). Studies have shown that the organisational ethics context factors have a significant impact on employees' job satisfaction and well-being (El-Nahas, Abd-El-Salam & Shawky 2013; Raja et al. 2020), and ultimately on the organisation's success (Rashid et al. 2003). Furthermore, organisational ethics context factors, that is culture and climate, predispose employees towards adopting particular ethical standards and deflect employees from unethical or disreputable conduct (Kilic & Mehmet 2022; Liu, Fellows & Ng 2004). Thus, dilemmas may arise because of differences in ethical manifestations, which are culturally dependent (Kilic & Mehmet 2022; Liu et al. 2004). According to Hollingworth and Valentine (2015), when an organisation possesses a strong ethical context, the result is enhanced employee ethical decision-making.

Ethical context has been characterised primarily by two multidimensional constructs, namely ethical climate and ethical culture (Hollingworth & Valentine 2015; Lee 2020; Trevino et al. 1998). Both constructs are concerned with the organisational context, which involves the in-house social psychological environment of the organisation, and the association of that environment with personal meaning and organisational adaptation (Moser, Seibt & Neuert 2021). Although in the mind of the general public, culture and climate may be considered synonyms, in the organisational context, culture commonly focusses on observable elements such as employee behaviour patterns and behavioural norms and values, whereas climate is concerned with employees' perceptions of their work environment (Bhaduri 2019). Thus, organisational climate can be viewed as a subset of organisational culture. Organisational culture pertains to the range of values and norms that influence the way subordinates think and conduct themselves within the working environment (Schein 2004; Tran 2021). Organisational climate, however, involves how subordinates perceive and characterise their working environment in an attitudinal and value-based manner (Rožman & Štrukelj 2021).

One way of ensuring that employees' conduct is ethical, is through the consistent utilisation of ethical leadership. Leaders are the shapers and developers of ethical teams (Homan et al. 2020). Ethical leaders are essential in shaping the moral context of an organisation (Demirtas & Akdogan 2015; Grojean et al. 2004). These leaders have also been shown to assist in developing group norms, which regulate how followers treat each other and ultimately how group members relate to one another (Kuenzi, Mayer & Greenbaum 2020; Mayer et al. 2012). When team members have trust in their leaders, they are more likely to follow ethical procedures (Godbless 2021; Hoyt, Price & Poatsy 2013).

The modern workplace continues to be characterised by increasing turbulence, debilitating uncertainty, and unethical practices (Elshaer, Ghanem & Azazz 2022; Mitonga-Monga, Flotman & Cilliers 2018). These defining features have led to a renewed focus on organisational ethics factors and the drivers of ethical practices in the workplace (Lei, Ha & Le 2019; Newman et al. 2020). Organisations are also required to reconsider the design of the workplace post pandemic, to attract, motivate and retain employees (Ali & Anwar 2021).

In the current global turbulent business environment, one observation remains uncontested. The changing pattern of work and life is dominated by millennials (Bennett et al. 2008; Rather 2018). This dictates that organisations must be in tune with the workplace experiences of millennials and are obliged to adapt their organisational ethics context factors to realise the demands and expectations of new generations in the workplace (Rather 2018). Crucial to the examination of the modern-day workforce is the understanding of the work attitudes of millennials (Gabriel, Alcantara & Alvarez 2020). That is, it is important to examine the work attitudes of millennials to understand them as potential managers.

An extensive body of knowledge exists regarding the relationship between ethical leadership, ethical culture, and ethics climate from a quantitative perspective (Haque & Yamoah 2021; Lei, Ha & Le 2020). The qualitative research on millennials' lived experiences of organisational ethics context factors, particularly within the South African and African context is less explored. There is also a paucity of research within the public energy industry with millennials as the focal group. Limited research has been dedicated to the concept of organisational ethics context factors and how these may influence employees' workplace conduct, as recommended by Mohr, Young and Burgess (2012). Therefore, a study of this nature may assist within the public energy utility sector, (which has been in the news for unethical practices) in assessing perceived leadership practices, as well as contribute to the limited research available pertaining to this important topic (Mazibuko 2020; Shokoya & Raji 2019). Thus, the aim of this study was to explore millennials' experiences of their organisational ethics contexts factors in a single organisation in the energy sector.

Theoretical perspectives

In this section, the social exchange theory (SET), the theoretical framework that underpins the study is presented. Organisational ethics context factors and work cohorts, notably millennials as the focus of this study, are also explored.

Organisational ethics context

The constructs ethical culture and ethical climate both refer to aspects of an organisation's ethical context. These constructs are viewed as having an influence on moral judgement and ethical behaviour (Van der Wal & Demircioglu 2020). Ethical culture is an organisational context factor that provides guidance to employee ethical decision-making. This is done through the personalisation of social values and norms (Zaal, Jeurissen & Groenland 2019). Leaders should be role models as they are a crucial source of ethical guidance for employees. Leaders are also responsible for forming the moral development of the organisation (Yang & Wei 2018; Zaim, Demir & Budur 2021).

Ethical culture

Ethical culture refers to aspects that stimulate ethical behaviour (Treviño, Weaver & Reynolds 2006; Van der Wal & Demircioglu 2020). Ethical culture can further be understood as the shared assumptions and beliefs held by members of an organisation. These assumptions and beliefs promote ethical conduct and deter organisational members from unethical conduct (Zaal et al. 2019). The ethical culture of an organisation can thus be viewed as a pivotal source of influence on the moral judgement of employees (Zaal et al. 2019).

Ethical culture has been considered by numerous researchers as an important dimension of organisational culture (Kaptein 2020; Van der Wal & Demircioglu 2020; Zaal et al. 2019). However, only a scant amount of research studies have attempted to link various attributes of ethical culture to unethical behaviour within organisations (Kaptein 2020; Van der Wal & Demircioglu 2020; Zaal et al. 2019).

Ethical climate

Ethical climate pertains to the most used form of moral reasoning by members of an organisation. The assumption underlying the concept of ethical climate is that members of an organisation share, at least to some extent, a form of moral reasoning (Gorsira et al. 2018; Van der Wal & Demircioglu 2020). As such, ethical climate approaches the notion of moral norms (Pagliaro et al. 2018). Moral norms include aspects such as behavioural guidelines. These guidelines drive the interpretation of what is considered to be right and wrong within groups and organisations (Pagliaro et al. 2018).

Social exchange theory

The theoretical underpinning of this study is informed by tenets of SET, which remains a prominent conceptual perspective in management and organisational studies (Mitchell, Cropanzana & Quisenberry 2012). The SET makes the assumption that the foundation of social life is exchange (Wyleżałek 2021). The social exchange theory is one of the pillars in understanding workplace behaviour and is deeply inculcated in our daily lives (Ahmad et al. 2023). The operating premise is that employees reciprocate in the form of an activity with equal value (Levine & Kim 2010). Thus, the SET offers a relevant framework for examining and analysing individuals' willingness to engage in social exchange (Cloarec, Meyer-Waarden & Munzel 2022).

The authors argue that this theory is relevant and applicable to this study. For example, employees in an organisation, like millennials, would be prepared to exchange commitment, for instance, in the form of organisational support and compliance, should they perceive their leaders to be ethical. Psychological exchanges may also occur in the form of being kind, compassionate, and by honouring the expectations of leaders in organisations. Thus, this theory offers a relevant framework for examining and analysing individuals' willingness to engage in social exchange (Cloarec et al. 2022). This theory is therefore the most applicable framework to examine current literature and to explore the research data from a qualitative perspective.

Millennials in the workplace

The millennial generation includes individuals born between 1982 and 2000 (Rather 2018; Wahab & Puteh 2021). The millennial generation has been exposed to technological advances since birth (Valenti 2019). Technology dominates the millennial generations' socialisation and means of communication. Work-life balance is an important aspect to the millennial generation within the workplace. In addition, millennials expect their work to be meaningful and to possess opportunities for advancement. Millennials also place value in the social aspect of their work environment (Valenti 2019). They want to collaborate and learn not only from their peers but also from their managers and expect to foster a strong relationship with their supervisors that is characterised by regular feedback and encouragement (Van der Wal & Demircioglu 2020). The question of whether an organisation's ethical context impacts employees' ethical decision-making process is an important one (Hollingworth & Valentine 2015). The presumption in practice is that ethics programmes, positive leadership, reinforcement, and other ethical approaches contribute to an organisation's values and engagement in ethical pursuits. These ultimately enhance an individual's ability to adequately recognise, assess, and act on ethical issues (Craft 2013). The millennial generation is concerned with operating within a positive company culture (Barron et al. 2007; Tsai 2017).

Research philosophy and methodology

Materials and methods

This study employed the interpretivism paradigm as theoretical lens and to guide data collection and analysis. Interpretivism, was given consideration to facilitate the 'verstehen' concept as it allowed for understanding, knowing, and comprehending both the nature and significance of the phenomenon being studied (Chowdhury 2014). In selecting interpretivism, the researchers were able to explore, understand and describe the organisational ethics context experiences of millennials. The study followed a qualitative research approach. This approach was deemed appropriate because of the aim and research problem to be investigated. Moreover, the qualitative research approach infuses an added advantage to the exploratory capabilities that researchers require to explore and describe a specific phenomenon (Alase 2017).

Participants and sampling

Purposive and convenient sampling was used (Qureshi 2018), with the possibility of further snowball sampling (Parker, Scott & Geddes 2019). These sampling methods were selected as a purposive sample affords for characteristics to be defined for a purpose that is relevant to the study (Andrade 2021). Moreover, the use of these sampling methods facilitates for depth in data to be gathered from a fairly small sample (Campbell et al. 2020). Thereafter, a convenience sample was drawn from the purposive sampling source that was accessible to us. The sample selection inclusion criteria included:

-

Age (millennial generation).

-

Working within the public energy utility institutions.

-

Willingness of the individual to volunteer.

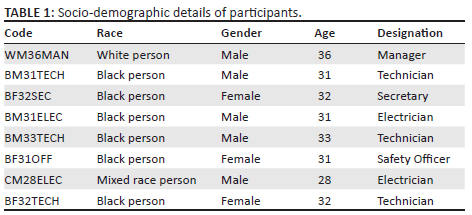

Data were collected from individuals working in the public energy utility organisation. The public energy utility organisation is a South African public electricity utility characterised by poor governance and a crumbling infrastructure (Bauer et al. 2017). The public energy utility organisation has over 16 000 subscribers in South Africa, this constitutes about one-third of the population. The participants were eight purposively selected employees who work within the public energy utility organisation. The sample comprised five men, and three women. The sample size was deemed to be sufficient, given the nature of the study for qualitative and phenomenological research (Geddes, Parker & Scott 2018), as well as the fact that data saturation had been reached (Saunders et al. 2018). The participants were between the ages of 20 and 36 years (cf. Table 1). Table 1 demonstrates how the codes for the participants were developed in an effort to maintain the participants' confidentiality.

Data collection and analysis

Data used for this study were collected by means of semi-structured interviews (Taylor 2005). The reason for the popularity of utilising a semi-structured interview method can be attributed to its capacity to be both versatile and flexible (Kallio et al. 2016). The focal advantage of using semi-structured interviews involves its ability to enable reciprocity between the interviewer and/or researcher and participants (Galletta 2012). Thus, the researcher shaped the interview process and outcomes through probing questions and affirming verbal contributions of participants (Glegg 2019). Some of the opening questions for the interview sessions were determined prior to the interviews, for example, 'Tell me about your experiences as a millennial in this organisation?'. Open-ended questions were applied to elicit rich meaning. The interview guide was structured as follows: (1) welcome and orientation, namely introduction, context, and purpose of (2) opportunity for interviewee to pose clarifying questions; (3) interview questions; (4) closure and way forward. Data were recorded by the researcher during the interview process through notes. Data were analysed by means of content analysis (Kleinheksel et al. 2020). This data collection method was selected as a key characteristic of content analysis and allows for the methodical process of coding, examining for meaning, and providing a description of a social reality by means of the formation of themes (Vaismoradi et al. 2016). Thus, content analysis is a technique used to analyse textual data and elucidate themes (Forman & Damschroder 2008).

As proposed by Creswell (2013), content analysis involves the following phases or process for data analysis: preparing and transcribing data; exploring and coding data; coding data to build themes; presenting and reporting data; conducting interpretations of findings; and validating the accuracy of findings. This process was followed in the data analysis phase.

Measures of trustworthiness

To ensure credibility and dependability, a detailed description of the data collection and analysis process was provided (Stacey 2019). Confirmability was achieved by means of providing an audit trail of the study to demonstrate how each decision was made (Amankwaa 2016). To ensure transferability, detailed descriptions of the studies are outlined to enable the reader to assess the applicability of these methods to their respective research interests (Amankwaa 2016).

Ethical considerations

An application for full ethical approval was made to the University of South Africa Research Ethics Review Committee and ethics consent was received on 11 November 2017. The ethics approval number is 2017_CEMS/IOP_020.

Participants were invited to participate in the study voluntarily, and they could withdraw from the study at any stage. They were required to sign a consent letter prior to the participation within the research study. The consent letter consisted of an explanation of the aim and importance of the study. Codes (cf. Table 1) were used to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of participants (De Vos et al. 2011). The primary researcher coordinated the collection and safe storing of data. No ethical guidelines were breached by the researchers throughout the research study process.

Findings

Five superordinate themes emerged from the analysis and interpretation of the data, which describe millennials' organisational ethics context experiences, namely (1) cordial employee workplace conduct; (2) respectful co-worker cohesion; (3) distrust between employee and manager; (4) perceived 'punishment ethos' as organisational identity; and (5) perceptions of organisational injustice. The article describes these five themes in verbatim text as obtained from the research data. Participants are acknowledged in brackets after extracts from their interviews, using codes (cf. Table 1) that presents the relevant socio-demographics of the eight participants.

Cordial employee workplace conduct

The millennials tend to view their colleagues positively, as professional where no harmful acts are deliberately directed to other colleagues. Generally, the working environment reported by the millennials was one that is gratifying. They also expressed that their working environment is further made more enjoyable as they are surrounded by fellow colleagues who are passionate about their jobs, for example, one participant noticed:

'I enjoy people who are motivated within the work environment.' (WM36MAN)

This sentiment was supported by another participant:

'The guys that I am working with are team players, we support each other.' (BM31ELEC)

Another participant observed that:

'My team is very supportive especially when I started working without any experience, they helped me to be where I am today.' (BF31OFF)

Cordial employee conduct sets the tone for workplace relations and ultimately personal satisfaction and organisational performance. However, the implications of unethical workplace conduct can be costly to organisations. In the case of the millennials in the public utility organisation, these millennials seem to portray behaviours, which are in the best interests of both the organisation and other employees.

Respectful co-worker cohesion

The millennials of the study held the perception that teamwork was prominent among their colleagues. The millennials also felt that colleagues were supportive of one another and that interactions between them could be regarded as respectful. The millennials held a uniform view regarding co-worker cohesion and generally had a desire to be included in the organisation's social structure with their respective employees. For example, one participant observed that:

I'm working with friends and a respectful, supportive team.' (BM33TECH)

Similarly, another participant noticed:

'I enjoy the culture of respecting each other and the people working around me.' (BF32SEC)

This attitude was further supported by being solid team players, for example:

'Teamwork is practised a lot even though the communication is not entirely open to all.' (BM31TECH)

The general positive outlook of these participants may result in employees of the public energy utility organisation's team feeling a sense of closeness, similarity, and unity among their peers and colleagues (Carless & De Paola 2000)

Distrust between employee and manager

Despite the cordial relations in a team context, a different experience emerged between employees and their line managers. This millennial cohort seemed to share the same sense of dissatisfaction about the level of trust they have for their managers or supervisors. As millennials they felt that managers or supervisors were not conducting themselves in a manner, which protected the interests of their subordinates. One participant shared:

'The management is also failing us as employees as most of our benefits are taken away from us due to the corruption being practiced.' (BM31ELEC)

This sentiment was echoed by another colleague who commented that:

'Favouritism among the line managers and supervisor is a problem because they protect each other … For example, a line manager protected the supervisor on a misconduct [harassment] to a junior employee.' (BM31ELEC)

The same cohort also felt that the values that they were expected to practise were not aligned with those that were practised by their respective managers or supervisors. This is supported by one of the participants who mentioned that:

'Integrity should start at top with good examples to the rest. How can I ask someone working for me to be honest if I am not?' (WM36MAN)

Another respondent added that:

'You can have the best rules and processes in the world, if management is not setting the example, it is worth nothing.' (BF32SEC)

In cases where employees have low levels of trust for their respective managers or supervisors, there may be serious implications.

Organisation's perceived identity: ethos of punishment

The participating millennials of the public energy utility organisation were unanimous in their experience of the organisation, as practising an ethos of punishment, rather than one of developmental behavioural change, for example:

'When an individual gets investigated something will be found against you, but I think sometimes it is too much about punishing someone instead of helping the person.' (CM28ELEC)

Despite this perceived ethos of punishment, the degree of centralisation in the organisation was an aspect the millennials regarded as positive. The millennials felt that they had the freedom to make work-related decisions without disturbance or pressures from managers or supervisors, for example:

'There are policies and procedures that are there as guidelines to assist in running the business with equality and fairness without management dominance and pressure.' (BF32SEC)

Moreover, the millennials expressed that they were encouraged to voice their thoughts and opinions freely and openly, for example:

'I also enjoy the environment of freedom of expression.' (BF31OFF)

The participants held a collective negative view of the corruption within their working environment. As millennials who supported integrity, they expressed the sentiment that organisational funds were being mismanaged by their managers and supervisors, for example:

'This [corruption] can make one negative and demotivated.' (BM31ELEC)

Another participant shared:

'On the wellness department, sports activities are stopped because the organisation doesn't have budget for sports activities.' (BF31TECH)

Perceived organisational injustice

The millennials mainly had a negative perception of their organisation's ethical context, particularly its justice system. The millennials perceived their organisation to be one that did not stand up for their employees' legislative rights. Moreover, the millennials asserted that, when it came to the justice system, favouritism influenced the type of punishment or praise that employees may receive, for example:

'Some unethical practices are handled very strictly, and others are swept under the carpet.' (WM36MAN)

Another participant supported this view by saying that:

'There is no fairness because of favouritism with management and certain employees who are favoured.' (BF32TECH)

Discussion

This study aimed to describe the lived experiences of millennials' organisational ethics contexts factors in an organisation in the energy sector. The findings suggest an ambivalent and paradoxical split in how millennials experience the ethical context factors in the participating organisation. Both positive experiences (in the form of cordial, civil relations, cooperative cohesion, and tacit trust between employees) and negative experiences (in the form of distrust between managers and employees, an ethos characterised by punishment, and perceptions of organisational injustice) seem to co-exist in the same workplace. This coincides with the works of Metwally et al. (2019) and Nemr and Liu (2021).

The findings further indicate that the participants of the study viewed their organisation as one that was predominantly deficient in terms of their subjective experiences of ethical conduct. The millennials held a common adverse stance regarding their organisational climate. The millennials articulated that favouritism, fairness, financial mismanagement, and restrained transparency and communication from upper management to subordinates was a major issue, which impacted them negatively as a whole. These aspects seem to be the principal drivers of unethical practices that transpired within this public energy utility organisation. The results are similar to the works of Hecht et al. (2023) and Kabeyi (2020). Nevertheless, employees were relatively fulfilled with their organisation's culture at a departmental level. The participants expressed the notion that their work roles and duties were largely related to their job titles (job satisfaction), employee teamwork was facilitated by the organisation, and their overall well-being, safety and work-life balance was a priority for the organisation (subjective well-being).

When leaders or managers of organisations face persistent problems with regard to ethics, creating an ethical culture through ethical leadership is an effective way to regulate unethical behaviour (Metwally et al. 2019). The findings of this research study suggest that ethical leadership and a climate of ethicality should be encouraged in organisations. This is also echoed in research by Al Halbusi et al. (2021). Employees may identify strongly with their leaders when leaders are ethical role models and emphasise ethical management. Leaders should therefore act as a moral exemplar to subordinates and should develop training programmes aimed at increasing their subordinates' collective moral potency (Eberly et al. 2017). In a study by Metwally et al. (2019) regarding positive influences to enhance change, it was revealed that ethical leadership enhances employees' readiness to change and that this impact is partially mediated by an organisational culture of effectiveness. This study confirms that there were positive elements in the organisation, which should ideally be nurtured by stronger ethical leadership.

These findings are supported by a recent study by Godbless (2021) as well as an earlier study by Hoyt, Price, and Poatsy (2013). Although the millennials of this study did not regard their organisation as being ethical wholistically, some departments at different levels presented results to the contrary. That is, the millennials regarded their respective work groups as those that functioned with morality.

An extensive body of research exists regarding the relationship between ethical leadership, ethical culture, and workplace ethics climate. These studies, however, were mostly conducted from a quantitative perspective. This specific study took on a less explored route. That is, a qualitative research study on millennials' lived experiences of organisational ethics context factors, particularly within the South African and African context. This study emphasises the importance of establishing an ethical work culture, being driven proactively by ethical leadership. This has implications for the evolution of organisational culture, but specifically managing organisational change. A practical implication is that organisations that are involved in culture change initiatives should put ethical leaders in management and leadership positions.

This core of ethical leaders would have the necessary integrity and credibility to facilitate active participation of employees and to ensure that the change project enjoys enough moral fibre required to reach the objectives of the organisation. It is clear from that study that millennials also value ethical leadership behaviours in the form of 'fair decision-making, empowering behaviour, people-oriented behaviour, ethical-guidance behaviour, role clarification, and integrity' as suggested by Metwally et al. (2019:14).

Millennials who already appear to value this moral inclination should be used as change champions to drive cultural change and similar initiatives. The study further affirms that the workplace and its dynamics is a complex cauldron of both ethical and unethical intentions, behaviours, and attitudes. Ethical and unethical behaviour will continue to co-exist cumbersomely. In other words, these complexities will continue to be intertwined and mutually influence each other. Hence, this study reminds managers and leaders to be cautious of adopting a simplicity mindset, but to rather remain sober minded by continuing to appreciate the value and presence of organisational complexity.

Conclusions and recommendations

It is envisaged that millennials will make up 75% of the global workforce by 2025. Millennials will continue to play a critical role as we recreate and reshape the new workplace in 'post-pandemic' times. Ethicality in the context of climate change and equality, for example, had emerged as the top social issues millennials expect from employers. This study provided an analysis of ethics and leadership within the public energy utility sector. Unethical organisations are a reality in South Africa. However, this study has revealed that ethical and unethical leaders and behaviour co-exist in the workplace and that effective, ethical leadership can minimise the prevalence of unwanted behaviour and conduct within organisations (Engelbrecht et al. 2017). Organisational manager and leaders should therefore take full responsibility for cultivating an ethical climate and culture through ethical managers and leader behaviour (Engelbrecht et al. 2017). By reinforcing these aspects, perceived manager and leader effectiveness can be advanced among employees, which will ultimately affect overall organisational performance (Engelbrecht et al. 2017). Millennials seem to value ethicality and should therefore be used as drivers of ethical behaviour and ethical cultures in our modern, complex world of work.

Limitations and future research directions

As with any research project, this study also contains limitations, which could be explored for further research endeavours.

Firstly, the study was confined to the public energy utility sector as well as a single organisation in South Africa. Secondly, the study took on a qualitative stance with a relatively small sample size, to obtain an in-depth understanding of the experiences of millennials' organisational ethics contexts factors within the organisation in the energy sector. Thirdly, inferences may be limited to and may only be made where contexts are the same or similar.

This may compromise the study's capacity to provide insight into millennials' experiences and behaviours in other sectors and organisations (Brannen 2017), which, however, is neither the intention of qualitative research in general nor this study in particular. Future researchers should therefore replicate the study within varying sectors that represent different populations. Additionally, the study can be executed quantitatively or using a mixed method approach. This will allow for a larger sample to be utilised to outline the common effects that organisational ethics context factors have on employee job satisfaction and the subjective well-being of the millennial generation. This will also allow for the data to be generalised to a larger group of individuals and facilitate in understanding the breadth and depth of the lived experiences of millennials' organisational ethics contexts factors. Another limitation that may have been present relates to bias. This may have resulted from the use of the purposive sampling method, considering that participants were selected on the basis of their readiness to provide meaningful information on the research topic (McMillan & Schumacher 2010). Therefore, it may be that only millennials who had specific feelings about the topic volunteered for the study. Overall, despite these concerns, the findings of this study provide useful insights for leadership and/or management studies, and offer opportunities for future research.

Acknowledgements

This article is partially based on R.M.M.'s thesis entitled 'Ethical leadership, group learning behaviour and group cohesion in the energy sector: A psycho-social model' towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Industrial and Organisational Psychology, University of South Africa, South Africa, January 2023, with supervisor Prof. A.P. Flotman. It is available here: https://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/30734.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

R.M.M. fulfilled the role of the primary researcher. This article formed part of R.M.M.'s Master's dissertation. R.M.M. was responsible for the conceptualisation of the study, collection of the data, interpretation of the research results and the writing of the article. A-P.F. assisted in the writing of the research article and played an advisory role in this article through the conceptualisation of the study design, which supports the writing of the article by describing the analysis procedures as well as the reporting.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors, or the publisher.

References

Ahmad, R., Nawaz, M.R., Ishaq, M.I., Khan, M.M. & Ashraf, H.A., 2023, 'Social exchange theory: Systematic review and future directions', Frontiers in Psychology 13, 101592. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1015921 [ Links ]

Al Halbusi, H., Williams, K.A., Ramayah, T., Aldieri, L. & Vinci, C.P., 2021, 'Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees' ethical behavior: The moderating role of person-organization fit', Personnel Review 50(1), 159-185. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2019-0522 [ Links ]

Alase, A., 2017, 'The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach', International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies 5(2), 9-19. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9 [ Links ]

Ali, B.J. & Anwar, G., 2021, 'An empirical study of employees' motivation and its influence job satisfaction', Journal of Engineering, Business and Management 5(2), 21-30. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijebm.5.2.3 [ Links ]

Amankwaa, L., 2016, 'Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research', Journal of Cultural Diversity 23(3), 121-127. [ Links ]

Andrade, C., 2021, 'The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples', Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 43(1), 86-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620977000 [ Links ]

Barron, P., Maxwell, G., Broadbridge, A. & Ogden, S., 2007, 'Careers in hospitality management: Generation Y's experiences and perceptions', Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 14(2), 119-128. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.14.2.119 [ Links ]

Bauer, N., Calvin, K., Emmerling, J., Fricko, O., Fujimori, S., Hilaire, J. et al., 2017, 'Shared socio-economic pathways of the energy sector - Quantifying the narratives', Global Environmental Change 42, 316-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.07.006 [ Links ]

Bennett, S., Maton, K. & Kervin, L., 2008, 'The "digital natives" debate: A critical review of the evidence', British Journal of Educational Technology 39(5), 775-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00793.x [ Links ]

Bhaduri, R.M., 2019, 'Leveraging culture and leadership in crisis management', European Journal of Training and Development 43(5/6), 554-569. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-10-2018-0109 [ Links ]

Brannen, J., 2017, 'Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: An overview', in Mixing Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Research, pp. 3-37, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S. et al., 2020, 'Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples', Journal of Research in Nursing 25(8), 652-661. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206 [ Links ]

Chowdhury, M.F., 2014, 'Interpretivism in aiding our understanding of the contemporary social world', Open Journal of Philosophy 4(03), 432-438. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43047 [ Links ]

Cloarec, J., Meyer-Waarden, L. & Munzel, A., 2022, 'The personalization-privacy paradox at the nexus of social exchange and construal level theories', Psychology & Marketing 39(3), 647-661. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21587 [ Links ]

Craft, J.L., 2013, 'A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature', Journal of Business Ethics 117, 221-259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1518-9 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2013, Qualitative inquiry and research design choosing among five traditions, 3rd edn., Sage, s.l. [ Links ]

De Vos, A.S., Strydom, H., Fouché, C.B. & Delport, C.S., 2011, Research at grassroots: For the social sciences and human service professions, 4th edn., Van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Demirtas, O. & Akdogan, A.A., 2015, 'The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment', Journal of Business Ethics 130, 59-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2196-6 [ Links ]

Eberly, M.B., Bluhm, D.J., Guarana, C., Avolio, B.J. & Hannah, S.T., 2017, 'Staying after the storm: How transformational leadership relates to follower turnover intentions in extreme contexts', Journal of Vocational Behaviour 102, 72-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.004 [ Links ]

El-Nahas, T., Abd-El-Salam, E.M. & Shawky, A.Y., 2013, 'The impact of leadership behaviour and organisational culture on job satisfaction and its relationship among organisational commitment and turnover intentions. A case study on an Egyptian company', Journal of Business and Retail Management Research 7(2), 1-31. [ Links ]

Elshaer, I.A. & Saad, S.K., 2022, 'Entrepreneurial resilience and business continuity in the tourism and hospitality industry: The role of adaptive performance and institutional orientation', Tourism Review 77(5), 1365-1384. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2021-0171 [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, A.S., Mahembe, B. & Wolmarans, J., 2017, Effect of ethical leadership and climate on effectiveness', SA Journal of Human Resource Management 15(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v15.781 [ Links ]

Forman, J. & Damschroder, L., 2008, 'Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer', Advances in Bioethics 11, 39-62. [ Links ]

Gabriel, A.G., Alcantara, G.M. & Alvarez, J.D., 2020, 'How do millennial managers lead older employees? The Philippine workplace experience', Sage Open 10(1), 2158244020914651. [ Links ]

Gabriel, A.G., Alcantara, G.M. & Alvarez, J.D., 2020, How do millennial managers lead older employees? The Philippine workplace experience, SAGE Open, pp. 1-11. [ Links ]

Gabriel, A.G., Alcantara, G.M. and Alvarez, J.D., 2020. How do millennial managers lead older employees? The Philippine workplace experience, Sage Open, 10(1), 21582440-20914651. [ Links ]

Galletta, A., 2012, Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research, New York University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Geddes, A., Parker, C. & Scott, S., 2018, 'When the snowball fails to roll and the use of "horizontal" networking in qualitative social research', International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21(3), 347-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1406219 [ Links ]

Glegg, S.M., 2019, 'Facilitating interviews in qualitative research with visual tools: A typology', Qualitative Health Research 29(2), 301-310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318786485 [ Links ]

Godbless, E.E., 2021, 'Moral leadership, shared values, employee engagement, and staff job performance in the university value chain', International Journal of Organizational Leadership 10(1), 15-38. [ Links ]

Gorsira, M., Steg, L., Denkers, A. & Huisman, W., 2018, 'Corruption in organizations: Ethical climate and individual motives', Administrative Sciences 8(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8010004 [ Links ]

Grojean, M.W., Resick, C.J., Dickson, M.W. & Smith, D.B., 2004, 'Leaders, values, and organizational climate: Examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics', Journal of Business Ethics 55, 223-241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-1275-5 [ Links ]

Haque, A.U. & Yamoah, F.A., 2021, 'The role of ethical leadership in managing occupational stress to promote innovative work behaviour: A cross-cultural management perspective', Sustainability 13(17), 9608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179608 [ Links ]

Hecht, G., Maas, V.S. & Van Rinsum, M., 2023, 'The effects of transparency and group incentives on managers' strategic promotion behavior', The Accounting Review 98(7), 239-260. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2020-0208 [ Links ]

Hollingworth, D. & Valentine, S., 2015, 'The moderating effect of perceived organizational ethical context on employees' ethical issue recognition and ethical judgements', Journal of Business Ethics 128(2), 457-466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2088-9 [ Links ]

Homan, A.C., Gündemir, S., Buengeler, C. & Van Kleef, G.A., 2020, 'Leading diversity: Towards a theory of functional leadership in diverse teams', Journal of Applied Psychology 105(10), 1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000482 [ Links ]

Hoyt, C.L. & Burnette, J.L., 2013, 'Gender bias in leader evaluations: Merging implicit theories and role congruity perspectives', Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39(10), 1306-1319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213493643 [ Links ]

Kabeyi, M.J., 2020, 'Corporate governance in manufacturing and management with analysis of governance failures at Enron and Volkswagen Corporations', American Journal of Operations Management and Information Systems 4(4), 109-123. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajomis.20190404.11 [ Links ]

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A.M., Johnson, M. & Kangasniemi, M., 2016, 'Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide', Journal of Advanced Nursing 72(12), 2954-2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031 [ Links ]

Kaptein, M., 2020, 'Ethical climate and ethical culture', in D. Poff & A. Michalos (eds.), Encyclopedia of business and professional ethics, Springer, Cham. [ Links ]

Kilic, E. & Mehmet, Ş.G., 2022, 'Employee proactivity and proactive initiatives towards creativity: Exploring the roles of job crafting and initiative climate', International Journal of Organizational Analysis 31(6), 2492-2506. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-01-2022-3100 [ Links ]

Kleinheksel, A.J., Rockich-Winston, N., Tawfik, H. & Wyatt, T.R., 2020, 'Demystifying content analysis', American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84(1), 7113. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7113 [ Links ]

Komalasari, S., Febrianto, R., Yurniwati, Y. & Odang, N., 2019, 'The influence of personal value, moral philosophy, and organizational ethical culture on auditor action and acceptance for dysfunctional behavior', in Proceedings of the 1st international conference on finance economics and business, ICOFEB 2018, 12-13 November 2018, Lhokseumawe, Aceh. [ Links ]

Kuenzi, K., Mayer, D.M. & Greenbaum, R.L., 2020, 'Creating an ethical organizational environment: The relationship between ethical leadership, ethical organizational climate, and unethical behavior', Personnel Psychology 73(1), 43-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12356 [ Links ]

Lee, D., 2020, 'Impact of organizational culture and capabilities on employee commitment to ethical behavior in the healthcare sector', Service Business 14(1), 47-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-019-00410-8 [ Links ]

Lei, H., Ha, A.T. & Le, P.B., 2020, 'How ethical leadership cultivates radical and incremental innovation: The mediating role of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing', Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 35(5), 849-862. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-05-2019-0180 [ Links ]

Lei, H., Ha, A.T.L. & Le, P.B., 2019, 'How ethical leadership cultivates radical and incremental innovation: The mediating role of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing', Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 35(5), 849-862. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-05-2019-0180 [ Links ]

Levine, T.R. & Kim, S., 2010, Social exchange, uncertainty, and communication content as factors impacting the relational outcomes of betrayal', Human Communication 13, 303-318. [ Links ]

Liu, A.M., Fellows, R. & Ng, J., 2004, 'Surveyors' perspectives on ethics in organisational culture', Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 11(6), 438-449. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699980410570193 [ Links ]

Motabologa, R.M., 2023, 'Ethical leadership, group learning behaviour and group cohesion in the energy sector: A psycho-social model' PhD thesis, Department of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Mayer, D.M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R.L. & Kuenzi, M., 2012, 'Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership', Academy of Management Journal 55(1), 151-171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276 [ Links ]

Mazibuko, G., 2020, 'Public sector procurement practice: A leadership brainteaser in South Africa', Journal of Social and Development Sciences 11(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.22610/jsds.v11i1(S).3109 [ Links ]

McMillan, J.H. & Schumacher, S., 2010, Research in education: Evidence based inquiry, 7th edn., Pearson, Boston, CA. [ Links ]

Metwally, D., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Metwally, M. & Gartzia, L., 2019, 'How ethical leadership shapes employees' readiness to change: The mediating role of an organizational culture of effectiveness', Frontiers in Psychology 10, 2493. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02493 [ Links ]

Mitchell, M.S., Cropanzana, R.S. & Quisenberry, D.M., 2012, 'Social exchange theory, exchange resources, and interpersonal relationships: A modest resolution of theoretical difficulties', in K. Törnblom & A. Kazemi (eds.), Handbook of social resource theory: Theoretical extensions, empirical insights, and social applications, pp. 99-118, Springer, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J., Flotman, A.P. & Cilliers, F., 2018, 'Job satisfaction and its relationship with organisational commitment: A Democratic Republic of Congo organisational perspective', Acta Commercii 18(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v18i1.578 [ Links ]

Mohr, D.C., Ho, J., Duffecy, J., Reifler, D., Sokol, L., Burns, M.N. et al., 2012, 'Effect of telephone-administered vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients: A randomized trial', JAMA 307(21), 2278-2285. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5588 [ Links ]

Moser, T., Seibt, T. & Neuert, J., 2021, 'Organizational culture and organizational climate research: A systematic literature review', EBOR Publication 1(1), 21-37. [ Links ]

Nemr, M.A. & Liu, Y., 2021, 'The impact of ethical leadership on organizational citizenship behaviors: Moderating role of organizational cynicism', Cogent Business & Management 8(1), 1865860. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1865860 [ Links ]

Newman, D.T., Fast, N.J. & Harmon, D.J., 2020, 'When eliminating bias isn't fair: Algorithmic reductionism and procedural justice in human resource decisions', Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 160, 149-167. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5588 [ Links ]

Pagliaro, S., Presti, A.L., Barattucci, M., Giannella, V.A. Barreto, M., 2018, 'On the effects of ethical climate (s) on employees' behavior: A social identity approach', Frontiers in Psychology 9, 960. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00960 [ Links ]

Parker, C., Scott, S. & Geddes, A., 2019, Snowball sampling, SAGE research methods foundations, s.l. [ Links ]

Qureshi, H.A., 2018, 'Theoretical sampling in qualitative research: A multi-layered nested sampling scheme', International Journal of Contemporary Research and Review 9(8), 20218-20222. https://doi.org/10.15520/ijcrr/2018/9/08/576 [ Links ]

Rachele, J., Washington, T.L., Cuddihy, T.F., Barwais, F.A. & McPhail, S.A., 2013, 'Valid and reliable assessment of wellness among adolescents: Do you know what you're measuring?', International Journal of Wellbeing 3(2), 162-172. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i2.3 [ Links ]

Raja, U., Haq, I.U., De Clercq, D. & Azeem, M.U., 2020, 'When ethics create misfit: Combined effects of despotic leadership and Islamic work ethic on job performance, job satisfaction, and psychological well-being', International Journal of Psychology 55(3), 332-341. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12606 [ Links ]

Rashid, Z.A., Sambasivan, M. & Johari, J., 2003, 'The influence of corporate culture and organisational commitment on performance', Journal of Management Development 22(8), 708-728. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710310487873 [ Links ]

Rather, B., 2018, 'Millennial generation: Redefining people policies for changing employment trends', The Researchers' International Research Journal 4(2), 27-41. [ Links ]

Rožman, M. & Štrukelj, T., 2021, 'Organisational climate components and their impact on work engagement of employees in medium-sized organisations', Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 34(1), 775-806. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1804967 [ Links ]

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B. et al., 2018, 'Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization', Quality & Quantity 52, 1893-1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [ Links ]

Schein, E., 2004, Organizational culture and leadership, Jossey, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Shokoya, N.O. & Raji, A.K., 2019, 'Electricity theft mitigation in the Nigerian power sector', International Journal of Engineering &Technology 8(4), 467-472. [ Links ]

Stacey, A., 2019, ECRM 2019 18th European conference on research methods in business and management, Academic Conferences and publishing limited, s.l. [ Links ]

Suh, J.B., Shim, H.S. & Button, M., 2018, 'Exploring the impact of organizational investment on occupational fraud: Mediating effects of ethical culture and monitoring control', International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 53, 46-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2018.02.003 [ Links ]

Taylor, M.C., 2005, 'Interviewing', in I. Holloway (ed.), Qualitative research in health care, pp. 39-55, McGraw-Hill Education, Maidenhead. [ Links ]

Tran, H.Q., 2021, 'Organisational culture, leadership behaviour and job satisfaction in the Vietnam context', International Journal of Organizational Analysis 29(1), 136-154. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-10-2019-1919 [ Links ]

Treviño, L.K., Butterfield, K.D. & McCabe, D.L., 1998, 'The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviors', Business Ethics Quarterly 8(3), 447-476. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857431 [ Links ]

Treviño, L.K., Weaver, G.R. & Reynolds, S.J., 2006, 'Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review', Journal of Management 32, 951-990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306294258 [ Links ]

Tsai, M.S., 2017, Human resources management solutions for attracting and retaining millennial workers, Business Science Reference, Hershey, PA. [ Links ]

Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H. & Snelgrove, S., 2016, 'Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis', Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 6(5), 100-110. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100 [ Links ]

Valenti, A., 2019, 'Leadership preferences of the millennial generation', Journal of Business Diversity 19(1), 75-84. https://doi.org/10.33423/jbd.v19i1.1357 [ Links ]

Van der Wal, Z. & Demircioglu, M.A., 2020, 'More ethical, more innovative? The effects of ethical culture and ethical leadership on realized innovation', Australian Journal of Public Administration 79(3), 386-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12423 [ Links ]

Wahab, H. & Puteh, F., 2021, The effect of learning styles on employee performance among adults working Gen Y, s.l., s.n., pp. 296-301. [ Links ]

Wyleżałek, J., 2021, 'Dilemmas around the energy transition in the perspective of Peter Blau's social exchange theory', Energies 14(24), 8211. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14248211 [ Links ]

Yang, Q. & Wei, H., 2018, 'The impact of ethical leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating role of workplace ostracism', Leadership & Organization Development Journal 39(1), 100-113. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-12-2016-0313 [ Links ]

Zaal, R.O., Jeurissen, R.J. & Groenland, E.A., 2019, 'Organizational architecture, ethical culture, and perceived unethical behavior towards customers: Evidence from wholesale banking', Journal of Business Ethics 158(3), 825-848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3752-7 [ Links ]

Zaim, H., Demir, A. & Budur, T., 2021, 'Ethical leadership, effectiveness and team performance: An Islamic perspective', Middle East Journal of Management 8(1), 42-66. https://doi.org/10.1504/MEJM.2021.111991 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Reneilwe Matabologa

matabrm@unisa.ac.za

Received: 25 July 2023

Accepted: 07 Dec. 2023

Published: 22 Mar. 2024