Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.23 n.1 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v23i1.1078

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Emerging market entrepreneurs' narratives on managing business ethical misconduct

Emeldah Lingwati; Anastacia Mamabolo

Gordon Institute of Business Science, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: South Africa's entrepreneurial landscape faces multiple challenges that minimise the growth of established firms. Ethical misconduct is one of the main challenges entrepreneurs encounter in their business activities.

RESEARCH PURPOSE: To gain deeper insight into the entrepreneurs' narratives of the types and management of ethical misconduct when engaging in entrepreneurial activities.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Entrepreneurs are central to economic development and alleviating challenges, such as poverty, employment creation and economic inclusion. Therefore, managing challenges that hinder their growth will contribute to the country's economic development.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: This study used narrative qualitative research to gather data on business ethical misconduct types and their management strategies. A sample of 17 established entrepreneurs participated in one-hour semi-structured interviews. Focusing on established entrepreneurs with more than three years in business provided real experiences of ethical misconduct and their management. Thematic narrative analysis was used to analyse the participants' experiences and develop key themes from the data.

This study used narrative qualitative research to gather data on business ethical misconduct types and their management strategies. A sample of 17 established entrepreneurs participated in one-hour semi-structured interviews. Focusing on established entrepreneurs with more than three years in business provided real experiences of ethical misconduct and their management. Thematic narrative analysis was used to analyse the participants' experiences and develop key themes from the data.

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: This study provides an ethical misconduct management framework that entrepreneurs could use in business practice and teaching.

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: This study contributes to entrepreneurial ethics literature and South African entrepreneurship knowledge development.

Keywords: entrepreneurship; ethics; ethical misconduct; ethical misconduct management; narrative.

Introduction

South Africa's entrepreneurship landscape has been labelled laggard relative to other less developed African countries because of its inconsistent performance and low estimated established firm measures (Swartz, Amatucci & Marks 2019). Amongst many challenges contributing to low entrepreneurial activity, entrepreneurs have to deal with ethical challenges (Robinson & Jonker 2017; Van Wyk & Venter 2022). Van Der Walt, Jonck and Sobayeni (2016) indicated a decline in ethical behaviour in the South African business environment. Moreover, the country's worrying economic state has placed additional liability on employees, influencing their deviant behaviour from the rules, involvement in questionable activities and cutting corners (Van Der Walt et al. 2016). This indicates that external factors could impact internal practices in these companies.

Literature on ethics in entrepreneurship has emphasised three key areas of interest: the benefits of ethical behaviours (Chang & Lu 2019; Schaubroeck, Lam & Peng 2016); the challenges of ethical behaviours (Lin, Ma & Johnson 2016; Mesdaghinia, Rawat & Nadavulakere 2019) and the impact of ethical behaviours on organisational performance (Dey & Steyaert 2016; Lauria & Long 2019; Mai, Zhang & Wang 2019). Despite the increasing focus on ethics, Van Wyk and Venter (2022) argued that business ethics research is still lacking in small enterprises. Mpinganjira et al. (2016) found that the South African corporate sector has mechanisms to enhance its ethical code of conduct. They contended that although studies on ethics focus on the individual, there is a need to assess ethics at the organisational level and evaluate company practices (Mpinganjira et al. 2016), especially in small enterprises (Van Wyk & Venter 2022). As such, this study centres on the interplay between entrepreneurs and their small businesses to address ethical misconduct.

Therefore, this study explores the established entrepreneurs' narratives of the types and management of ethical misconduct when engaging in business activities. To establish this, this study focused on 17 established (in operation for at least 3 years) entrepreneurs based in South Africa, specifically in the Gauteng province. The prolonged business duration ensured that these entrepreneurs engaged in business activities where their ethical principles were challenged.

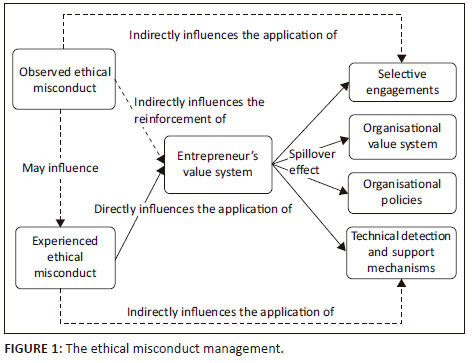

This study makes several contributions to the literature on entrepreneurship and business ethics by explaining the four mechanisms that small businesses use to manage ethical misconduct. Firstly, the narratives of entrepreneurs revealed two types of ethical misconduct, one is observed by how others engage in business, and the other is directly or personally experienced by the entrepreneurs, which influenced how their organisations respond. Secondly, the observed ethical misconduct reinforces entrepreneurs' value systems, while the experienced misconduct leads to active enactment or direct application of entrepreneurs' values to deal with the misconduct. Thirdly, entrepreneurs' value systems spill over to influence the organisational response to ethical misconduct. Fourthly, the ethical misconduct management mechanisms applied by small businesses, as influenced by the entrepreneurs' value systems, include selective engagement of potential employees and partners, organisational value systems, organisational policies and technical detection and support mechanisms. Lastly, the findings of this study build on the extant literature by demonstrating that social learning, entrepreneurs' identities and moral value spill over effects influence the management of business ethical misconduct.

Literature review

Theoretical underpinning

This study is underpinned by deontological theory, also known as formalism, which focuses on how entrepreneurs make decisions based on rules and principles (Love, Salinas & Rotman 2020). In the context of this study, formalisation implies that entrepreneurs based their entrepreneurial activities on values, rules or principles. Although there are formal rules in place, Crane and Matten (2016) suggested that ethical behaviours not only adhere to conventional moral standards, but also consider what a person with good moral standards would deem appropriate in each situation. Therefore, there are ethical behaviours that are not only a result of rules and principles, but also are individuals' moral standards. Fryer (2016) suggested that, instead of seeking legitimate solutions to ethical challenges, it is noble for business ethics to engage with people's perspectives and understand their views. This will enhance the understanding of individuals' behaviour(s) in business activities.

Entrepreneurial ethical misconduct

Since entrepreneurship focuses on the presence of opportunities and behavioural enactment by entrepreneurs (Shane & Venkataraman 2000) as well as risking and capitalising on opportunities (Hagel 2016), entrepreneurs' conduct in business activities is, thus, significant (Clarke & Holt 2010). Vallaster et al. (2019) explained that entrepreneurial behaviour implies a set of actions confronting entrepreneurs with circumstances in which decisions usually challenge existing moral standards. It is evident from the literature that morals and ethics play an essential role in how entrepreneurs conduct their businesses (Zhu 2015). In this study, ethics are defined as the intrinsic system and moral principles used to govern entrepreneurs' behaviour, including conducting their entrepreneurial activities (Crane & Matten 2016; Vallaster et al. 2019).

If ethical principles are compromised, the resulting situation is ethical misconduct. In an organisational context, Brown, Buchholtz and Dunn (2016) perceived misconduct as unethical or corrupt actions; mistakes because of incompetence or neglect of duties and lack of consistency among top, middle and bottom levels. Senadheera (2018) discovered that some ethical misconduct at an organisational level includes tax avoidance, report misconstructions, illicit payments and favours, unreliable guidelines and regulations and strong unethical network influences. This implies that misconduct or unethical behaviour could be intentional or unintentional, requiring it to be managed cautiously and strictly using the existing rules and principles to avoid these potential unintended consequences.

This study centres on ethical misconduct at an organisational level, thus including the entrepreneurial management team and employees. Literature suggests that when the top and middle management are not in sync regarding the expected ethical conduct, it is more likely that the firm will find itself marred with ethical misconduct (Brown et al. 2016). Individuals have difficulties resolving ethical conflicts between ethical frameworks in their personal lives and those they would use in their professional settings (Lauria & Long 2019). A critical challenge that entrepreneurs may encounter is a lack of synergy between different levels of management, making it essential for entrepreneurs to ensure alignment in understanding the company code of conduct. It is also vital for entrepreneurs to understand that individuals have their template of ethical values and principles that may misalign with the company's requirements, making it necessary to reiterate the code and ensure alignment.

Managing ethical misconduct

There is a distinction in how small and large corporates deal with ethical decisions, dilemmas and misconduct. Small companies have limited tools and resources, such as skills, knowledge and technology, to make decisions; whereas, large corporates have sophisticated decision-making systems (Savur, Provis & Harris 2018; Van Wyk & Venter 2022). Some less costly ethical misconduct preventative measures are behavioural, focusing on having ethical leaders. As such, entrepreneurs can use their values and ethical leadership to reinforce ethics within their organisations (Lingo 2020). Rochford et al. (2017) suggested that ethical leadership is the ability to consider issues from different perspectives, which may be fair and just. In addition, entrepreneurs may balance the differing opinions against each other and encourage consistency in their conduct by reinforcing fairness and justice. By leading a team of different individuals, it is expected that there will be different views and opinions. Literature suggests that the role of an ethical leader is, in a fair manner, to guide these differences in the right direction (Rochford et al. 2017). An essential role of an ethical leader within an entrepreneurial business is influencing followers to buy into the ethical standards, rather than enforcing them (Munro & Thanem 2018).

Some organisations manage ethical misconduct by establishing an ethical climate, the 'prevailing perceptions of typical organisational practices and procedures that have ethical content' (Newman et al. 2017:477). To promote an ethical climate, organisations must ensure that their internal structure is strategically organised, with top management creating a clear moral message and setting the ethical tone in the organisation (Warren, Peytcheza & Gaspar 2015) through policies, practices, procedures and technical or operational processes (Robinson & Jonker 2017). The management team is expected to play a role beyond the internal business environment to ensure that they do not indirectly support unethical practices in their supply chain (Clarke & Boersma 2017). Therefore, managers are tasked with checking the ethical behaviour of their existing and potential partners.

Research methodology and design

Research design

The research is underpinned by interpretivism philosophy to explore the under-researched entrepreneurs' experience of ethical misconduct in an emerging market context. Interpretivism allows entrepreneurs to construct meaning from their experiences of ethical challenges when conducting business activities. The exploratory, inductive approach allows the observation of trends in the data and formulation of themes as contributions to the understanding of the phenomenon under exploration (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2012).

This research followed a narrative qualitative research design to understand the kinds of ethical dilemmas narrated by entrepreneurs and how they manage them. The narrative research helped entrepreneurs to share the story of their ethical misconduct encounters and some of their personal experiences (Clandinin, Cave & Berendonk 2017). In alignment with the study's design, the unit of analysis was the narratives of the types of ethical misconduct and the management strategies employed by entrepreneurs within their businesses. The narratives centred on developing themes on the types of ethical misconduct experienced by entrepreneurs. Rather than focusing on how entrepreneurs told their stories, the interest was in the key themes that emerged from their stories (Maitlis 2012). Understanding the types of ethical misconduct helped to elucidate the management strategies.

Purposive sampling was used to select the participants. The chosen sampling method helped to identify participants who are in alignment with the theoretical focus of the study. The emphasis was on participants who have experienced ethical misconduct or dilemmas. Moreover, purposive sampling facilitated capturing a wide range of perspectives on ethical misconduct identified by founding entrepreneurs in different industries.

Since the topic of ethical misconduct is perceived as sensitive, the participants were carefully screened. An open invitation was sent to entrepreneurs using personal and professional networks. Some participants were referred by colleagues, but were assessed for fit according to the study's criteria. To ensure that the participants were entrepreneurial, one of the researchers searched the participants' online professional profiles and company information. If satisfied with the participants' entrepreneurial journeys, the researchers formally invited the entrepreneurs to participate in this study via email and telephone. The entrepreneurs were given an option to either proceed with the interview or opt out.

The sampling criteria included entrepreneurs in a formal business for at least 3 years, being the founding or co-founding business members and being based in South Africa. The participants were running businesses in the Johannesburg area of Gauteng, which is considered a city of business and entrepreneurial activities. The focus on the managers provided the real experiences of ethical misconduct and their management.

The sample size was 17 respondents from various industries (see Table 1), with the youngest participant being 30 years old and the oldest being 64. The newest company existed for 2 years and the oldest for 24 years. The smallest workforce included 6 employees, while the largest had 120 employees. Although the sampling size required a minimum of 3 years in operation, one company had a business duration of just 2 years. The entrepreneurial business was part of a larger institution and rebranded as a stand-alone entity. In addition, the new division entrepreneur had significant prior entrepreneurial experience and encountered ethical misconduct challenges. The sample size was beyond the recommended 12 for qualitative research (Guest, Bunce & Johnson 2006) and was deemed adequate for the study.

Data collection

Prior to data collection, the researchers applied for ethical clearance at the local university. Once ethical clearance approval was obtained, one of the researchers reached out to the participants and led the data collection process. A detailed ethical consideration discussion preceded the interview. The consent letter was read to the participants and later asked for their signatures. The respondents agreed to participate voluntarily and had the right to withdraw at any point during data collection. In addition, they gave consent to have data stored without identifiers and use anonymous quotations when reporting the data. Confidentiality was ensured by storing the interview recordings securely, using anonymous quotations and removing identifiers from the participants' transcripts. Initially, 19 participants were recruited to participate, but two of them were hesitant to sign the consent letter and, hence, were excluded from the study.

The participants gave consent to record the interview. The face-to-face interviews were recorded using a digital voice recorder, while the online interviews used the meeting platform's audio recording function. In the absence of any discomfort with the recording process, the process continued. Data were collected through 15 face-to-face and two online semi-structured interviews with the (co)founding executives of the selected companies. The semi-structured interviews allowed the participants to share their stories without being limited by the managerial type of questions. There were no significant differences between the face-to-face and online interviews.

The semi-structured interview guide focused on four sections. Section A explored the participants' background. Section B centred on broad questions about the entrepreneurs' value systems (Brown et al. 2016). Since the study tackles a 'sensitive' topic, the interview started with broad questions and ended with specific questions as a way of creating rapport. This funnel approach was emphasised by Adhabi and Anozie (2017), who also warned against influencing the responses to fit a preferred point of view. Instead, the researcher had to focus on obtaining the participants' experiences, perceptions and thoughts.

Once the researcher established a rapport with the participant, the interview proceeded to Section C on ethical misconduct. These questions were developed based on the literature sources, such as Robinson and Jonker (2017) and Warren et al. (2015). The participants were asked to share their general perceptions of ethical misconduct. Again, this made the participants open up and share their experiences without being prompted. Once they were comfortable with the ethical misconduct discussions, the participants were asked to share their personal experiences. The last part of the interview focused on the management of ethical misconduct. At the end of the interview, the participants were allowed to add insight left out during the interview.

Since entrepreneurs were engaged in daily business management activities, the average length of the interview was 37 min, which did not significantly interrupt their schedules. The interview guide had limited and focused questions on the key themes. The entrepreneurs availed themselves to answer the follow-up questions by email or telephone. At the end of each interview, the audio recordings were stored on a cloud service with a password known only to one of the researchers and later saved on the university's data platform. Once the data collection process was completed, the data were transcribed using the manual listening and typing method and software. All transcripts were quality-controlled and anonymised. The quality control also included translating vernacular phrases mentioned in the interview into English. The cleaned transcripts were stored on the cloud platform and later submitted to the university's data platform.

Analysis approach

The narrative, thematic analysis method was used to analyse the data. Thematic analysis is a widely used approach that is found to be flexible because of its allowance for multiple ways of data interpretation by focusing on either the entire data set or only one aspect of the phenomenon in depth (Braun & Clarke 2006). Maitlis (2012) mentioned that thematic analysis in narrative design could focus on the themes derived from the data rather than how the story is being told. Firstly, the researchers read the transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data and the entrepreneurs' stories. Secondly, the critical points from the transcripts were coded to highlight the relevant points. Thirdly, similar code summaries were grouped into categories that revealed the emerging patterns in the data. Fourthly, the researchers reviewed the themes to ensure that they represented the data accurately. Fifthly, the themes were labelled (see Table 2). Lastly, the analysed data were presented and included in the findings section. To ensure quality, the researchers included the participants' views or quotations in the findings presented. Furthermore, the researchers ensured credibility and transparency of the entire data collection process, coding and findings construction by providing the codes and themes that emerged from the data and showing how the conceptual model was developed (Reynolds et al. 2011).

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the Gordon Institute of Business Science.

Findings

This section presents the themes of the study, focusing on the types of ethical misconduct and their management strategies.

Types of ethical misconduct

The first theme presents the entrepreneurs' narratives of ethical misconduct. From their narratives, two main types of ethical misconduct were developed: observed and experienced.

Theme 1: Observed ethical misconduct

Entrepreneurs are aware of the ethical challenges their peers encounter and perceive that it is widespread in South Africa. These observed ethical misconduct are based on entrepreneurs' scanning of the business environment. Ethical misconduct observed by entrepreneurs was found to be the sourcing of new work or projects through political connections, unfair processes, not honouring payments and lack of consequences.

Most participants have observed that those with political affiliations or connections benefit from those relationships. A few politically connected entrepreneurs tend to receive more work, as opposed to those who are not. The entrepreneurs observed that other businesses would get contracts for work that is not aligned with their business activities because of their networks. One participant indicated:

'It is only a few connected people that are going to get business then if you are not connected, but you have got the skills, because of unethical behaviour, you are not able to get opportunities.' (Participant 10)

Participant 8 explained how he was influenced to join a political party after observing how others with political connections got business. Although the participant got the contracts, he was grateful that it did not work out. This participant's observation translated into experienced ethical misconduct:

'I ended up obtaining political membership, just to see if I can get business because the people that are affiliated with politicians are the ones that are getting business. We were not getting any way, but as soon as you start involving these people, doors start opening. But, as I said, the project did not go anywhere.' (Participant 8)

One consultant entrepreneur mentioned that other entrepreneurs often find themselves hard-pressed on resource constraints, mainly because of their company sizes and a constant need for resources. Entrepreneurs would, at times, not honour specific responsibilities, such as tax payments to protect the company and the employees; however, the act might be viewed as unethical:

'The business did not pay South African Revenue Service, and word goes around; they do not pay unemployment insurance fund. If they do not pay this, they are just trying to survive; the employees also do not feel valued.' (Participant 6)

Lastly, there is a view on the lack of enforcement or monitoring by authorities on ethical misconduct, implying a lack of accountability from the officials' end. One of the participants asserted:

'As I said, there is a lack of consequences. You see, people commit minor crimes, and they get away with it. And then people think, okay, I can do bigger or more significant offense, then I'll get away with it.' (Participant 16)

As such, the lack of consequences promotes unethical behaviours, while discouraging those wanting to do the right thing.

Theme 2: Experienced ethical misconduct

The experienced ethical misconduct that directly impacts entrepreneurs was identified by participants as ranging from employee and customer misconduct to bribery. In addition, it is critical to indicate that some participants were at ease sharing the ethical misconduct they faced in their businesses.

Dishonesty or untruthfulness was the most common challenge many entrepreneurs faced, both internal and external to the business. This behaviour can create mistrust between employees and employers, companies and customers and companies and suppliers. One participant shared how a client behaved unethically by making big decisions that affected the company financially:

'We had cases where one of our partners or staff went behind our back as the main contractor to talk to the client. And then we had to immediately indicate to them that they have behaved in a very unprofessional, unethical way.' (Participant 10)

The data show that employees are critical stakeholders in any business, although their conduct can sometimes be questionable, even when they know the code of conduct. Misconduct is based on breaching the rules and regulations in a work context. Participants shared frustration with employees who continue to misbehave, even if discussions on ethics are conducted. One participant shared an incident:

'It happens to my staff. Sometimes you say these are the dos and don'ts. They are still doing things their way, including stealing from your business and selling things back door. That is how I was affected by unethical work. I cannot do that.' (Participant 1)

The bribery request practice is one of the complex challenges entrepreneurs experience when sourcing new work to sustain their businesses. The participants mentioned that the officers managing the projects would request bribes for them to approve the projects:

'Getting work comes to the issue of ethics as well. After submitting your bid for work, you will get those guys calling you now and then saying, 'I saw your document'. They will be sending you WhatsApp, "Hey, e-wallet [electronic/mobile money] me on this number."' (Participant 4)

Requests for bribes extend to requests for favours. The entrepreneurs shared that some suppliers request project approval favours, even though they delivered a substandard service and expect the inspectors to sign off on their projects. Moreover, after awarding the contract, people involved ask that their relatives be hired and, mostly, these relatives are not skilled to do the work. Some officials engage in unethical payment behaviour by withholding payments so that the service providers can pay them to release the funds. Participants also shared that in cases where they have refused bribes, their payments have been delayed.

Ethical misconduct management

The participants indicated that managing ethical misconduct is a complex process. The data showed that the businesses rely on the entrepreneurs' or founders' value systems, which influence organisational ethical misconduct management strategies, such as selective engagement, organisational values, organisational policies and technical detection and support mechanisms.

Theme 3: Entrepreneurs' value system

The participants indicated several values. Honesty was identified as one of their essential personal ethical values that were incorporated into their businesses, particularly honesty among shareholders, and in the interaction with business shareholders and customers:

'So don't hide mistakes; when you are a shareholder, you will probably look at the business much better. The honesty part of it is [to be] honest with each other as shareholders but also to be honest with our customer base, not to lie with them, give them the facts. Don't just tell them something that they want to hear.' (Participant 2)

'So, I think given an opportunity, we try to encourage even our client because ethical behaviour affects both the business and also the client … so that we are able to continue and do business in an ethical way.' (Participant 10)

The participants raised the importance of respect for maintaining healthy internal and external business relationships. They display an attitude of respect beyond their immediate colleagues. The participants insisted that they expect people to be respectful when they are on their premises, irrespective of the individual's identity. This is supported by Participant 13, who noted that, 'Respect. I do not care who you are, where you from, what nation you are, you respect everybody'.

Furthermore, the participants reported that integrity is another significant value that drives how they conduct their business activities. Participant 4 highlighted the importance of 'professional integrity and honesty because that is the backbone of our business'. Entrepreneurs can transfer these value systems into their organisations and abide by them.

Theme 4: Selective engagements

The data showed that, since entrepreneurs constantly engage with multiple stakeholders, being selective or assertive is essential to ensure that the rules are followed. The participants acknowledged that it is vital to stand firm on regulations and not be tempted to compromise, even if the business must let go or withdraw from other engagements. Some participants mentioned that they intentionally do not engage with politicians. For example, a participant revealed:

'I do not want any other thing: either you come to join me, or you are out. The minute I start dancing to your song, you can switch it off at any time, and you can put the volume up any time and expect me to keep up with you.' (Participant 1)

Within businesses, the participants indicated that ethical enforcement starts with the hiring process; this way, they can hire people aligned with the businesses' ethical culture. Some participants further shared that they intentionally do not hire for skill but for the character, citing that it is easier to teach a skill than a behaviour. One of the participants said:

'When I look at people and work with people, I look for those characteristics whereby I can say take my priceless possession, which is my business, and I can give it to this person, and they will take care of it.' (Participant 2)

Theme 5: Organisational value system

Entrepreneurs mentioned that the organisational values that drive their businesses include leading by example, employee prioritisation, building a team spirit, accountability, transparency and professionalism. According to the study's participants, a leader who leads by example seems to get the enforcement right, as employees see it first-hand, as opposed to reading it on paper. Most participants agreed that this is a practical approach Therefore, entrepreneurs should be exemplary leaders. Establishing the organisational value systems also involves soliciting support or 'buy-in' from employees and other leaders within the business. Most participants expressed their dislike of the word 'enforcement', preferring what they deem a better approach, namely 'buy-in' from stakeholders. The participants explained that the buy-in approach is the most effective way to persuade employees to obey the rules, as they are primarily involved in giving input into the rule document. Obtaining input from employees was also found to encourage team building. This is consistent with the insight shared:

'You must get people to buy into it and, you know, if my value is the same as your value, then it would be effortless to get people to buy into it and to accept it.' (Participant 16)

Another theme on the values influencing a business's ethical value system is accountability, where participants shared the importance of delivering as expected. Not only is accountability key among team members, as one participant indicated, but also it is essential for effective and responsible management of company resources. This is illustrated by Participant 11: 'We try to entrench this notion of being a good steward of resources and exercising frugality so that you do not go outside of our means'.

The results revealed various ways to incorporate ethical standards. Talking openly and honestly about issues and challenges is one of the effective methods entrepreneurs can adopt in their businesses. They further encourage that constant reminder to employees is on the bigger picture of the business. Finally, entrepreneurs encourage professionalism, a vital driver of the value system, as it assists all stakeholders in consistently following acceptable practices, which will help in avoiding ethical misconduct.

Theme 6: Organisational policies

Most of the study's participants mentioned having policies to manage ethical misconduct. They also emphasised that it can be challenging to have comprehensive policies that address all possible deviations, which is why there is an adoption of a 'fix-as-we-go' approach. While entrepreneurs need to have policies in place to enforce conformity, the results revealed that it is also critical for the companies to practise patience with their employees and offer support in the form of training or counselling where necessary. These initiatives are crucial in guiding how entrepreneurs manage ethical misconduct. If one commits ethical misconduct, organisational policies, such as a disciplinary hearing, are applied. Others identified loopholes in their policies that required modification according to the emerging ethical misconduct trends. These results are substantiated by the following statements:

'I have got the policy statement, and that policy statement is shared with the employees, and we are operating on those bases.' (Participant 1)

and,

'We have got the policy, and it always changes, every experience teaches you.' (Participant 15)

While there are policies to guide employees' behaviours, there are also guidelines for engaging external stakeholders. In addition, participants mentioned the importance of customer and external stakeholder satisfaction according to their agreements to ensure that they keep returning for the service and avoid unpleasant experiences.

Theme 7: Technical detection and support mechanisms

The last ethical misconduct management element acknowledges that some enforcement processes are tech-enabled, as opposed to the traditional way of sitting and discussing a code of conduct with stakeholders. Participants believe that technical systems are accurate and, therefore, less prone to errors. Furthermore, most of the participants highlighted that it is good to test the process without notifying employees randomly, as this will ensure that employees are not complacent, thinking that the company will wait for complaints. A participant supported these results, sharing:

'We also do surveys, randomly call the clients to check how it went. Ask random things like, "Did you get water? Are you happy?". (Participant 5)

Majority of participants highlighted an automated process using biometrics to identify patterns. This will show employees' behaviour, especially if they have a habit of consistently taking time off for specific periods. Some participants indicated that a performance review system is effective and encourages transparency on what the employer expects from employees. This system also helps with identifying the development needs of the employees:

'They do get reviewed at every single performance review. So, after a project, you have to review yourself and say how I did on the project itself and then from a technical side as well as a soft skill side.' (Participant 15)

'We have a biometric monitor. That helps you a lot if in a month, for instance, you each month, a week after month end, for six days you are not coming to work every month, it must tell you something.' (Participant 3)

Several aspects were considered in answering the question about entrepreneurs' interpretations of ethical misconduct and how they manage them. The findings demonstrate that entrepreneurs are aware of the ethical misconduct challenges in their field and have measures to deal with them.

Discussion

Ethical misconduct

The findings of this study demonstrate the two types of ethical misconduct, as observed and directly experienced. The observed ethical misconduct does not directly involve or affect entrepreneurs. Participants expressed awareness of many ethical challenges other entrepreneurs experience, some of which were driven by a lack of law enforcement from institutions and a lack of consequences for those who flout the regulations. The ethical misconduct included political networks and interference in sourcing new business or unfair processes, where officials solicit illegal payments from entrepreneurs to access the jobs. Some participants also indicated that entrepreneurs go as far as affiliating with political parties to access new work opportunities. Although ethically questionable for those who use it, this approach seems to succeed in accessing these jobs. This is consistent with the findings of Brown et al. (2016) that misconduct is associated with corrupt acts, mistakes resulting from incompetence or even neglect of duties.

This study contributes to literature by incorporating social learning theory into understanding how the observed ethical misconduct influences entrepreneurs' ethical behaviour. According to social learning theory, individuals learn by observing others (Bandura & Walters 1977). They create hypotheses of different types of behaviours that are likely to succeed (Bandura & Walters 1977). Consequently, in this study, some entrepreneurs observed and developed the hypothesis that politically connected people succeed in business. As a result, they also decided to be affiliated with political parties to solicit business. Fortunately, in their case, most of the business activities did not work out. Some entrepreneurs hypothesised that ethical misconduct was costly in the long run, reinforcing their ethical value systems.

This study found that some ethical misconduct are directly experienced, both within and outside the business. Internally, the findings show incidents, such as tax avoidance and employees who steal from the business and are dishonest about their work activities (Brown et al. 2016). Externally, the findings indicate that entrepreneurs have had to deal with dishonest partners, requests for bribes and favours, delayed payments and tax avoidance. Senadheera (2018) also found that some entrepreneurs are exposed to unethical activities, such as tax avoidance and strong network influences. Another contribution from this study is that when entrepreneurs directly experience ethical misconduct (some previously observed), they use their value systems and identities to influence the organisational response strategies. While previous research emphasised the influence of the entrepreneurs' identity in early business formation (Mmbaga et al. 2020), this study adds to existing literature the notion that the entrepreneurs' value systems, as part of identity, play a significant role when a business is established or in the later stages of the entrepreneurial process.

Managing the ethical misconduct

Another unexpected finding is the spillover effects of entrepreneurs' value systems on how the organisations manage ethical misconduct. The results reveal that entrepreneurs or founders have their values, which they believe are critical to their businesses' success and sustainability. Integrity, honesty and respect were the entrepreneurs' values that spilled into their businesses. The findings of this study agree with Senadheera (2018) on values including honesty and respect, which are found to influence entrepreneurs' ethical value systems. Furthermore, Robinson and Jonker (2017) indicated that entrepreneurs' values are reflected in the businesses' culture. Then, this study's argument borrows insight from spillover theory to explain that entrepreneurs' value systems are part of ethical misconduct management and inform the organisational response strategies. In their study on spillover theory and team dynamics, Chang and Lu (2019) found that leaders with an empowering spirit positively impacted their subordinates' psychological empowerment and subsequent proactive behaviours. Thus, entrepreneurs' ethical orientation will influence that of the organisations.

According to Robinson and Jonker (2017), entrepreneurs hire people with similar values. The findings show that since entrepreneurs' values are intertwined with their organisations' value systems, they (pre-)manage the ethical misconduct by being selective of whom they engage with in business. This perspective is applied to the hiring of employees and the choice of business partners. Externally, Clarke and Boersma (2017) argued that ethical misconduct could emanate through association, meaning that companies could be accused of unethical practices if they do business with partners who engage in unethical practices. Like Drover, Wood and Fassin (2014), the findings reveal that the entrepreneurs were cautious about partnering with institutions and potential business partners perceived as unethical. Despite entrepreneurs trying to avoid ethical misconduct by screening their stakeholders, they do not always screen properly, resulting in cases of ethical misconduct.

It has been discovered that small businesses have a great challenge of resource constraints, which compromises their processes of curbing ethical challenges (Savur et al. 2018; Van Zyl & Lazenby 1999). This study found that one less costly way to manage ethical misconduct is by establishing organisational values and leading by example. Like other studies, some essential organisational values are transparency, honesty, accountability and professionalism (Robinson & Jonker 2017; Van Wyk & Venter 2022). Most participants highlighted the importance of buy-in from all stakeholders, as they found it to be an effective way to enforce these ethical standards, as opposed to enforcing the rules. Warren et al. (2015) supported this sentiment that buy-in on ethical standards by middle managers is critical as they are strategically positioned in the company to communicate with lower-level employees. Rochford et al. (2017) suggested that involving a team in pertinent discussions encourages the team and would make employees feel valued as part of the company. Such participation could enhance stakeholders' perceptions of their leaders (Pircher Verdorfer & Peus 2020). Participants agreed with this approach and shared that they involved the team in discussions on moral issues.

Participants also indicated that they use the code of conduct or organisational policies to enforce ethical standards in their businesses and when engaging with external stakeholders. Furthermore, they suggested that awareness and communication of these policies are critical for ensuring that the behaviour is the same in the company. Where possible, organisations provide employee training on ethics. Warren et al. (2015) confirmed that the message sent by senior management to lower-level staff through policies and procedures sets the ethical climate in the organisation. On the contrary, although most participants agree that principles are essential, some do not have these rules formalised and endorsed on paper, citing that they have a manageable number of employees. Therefore, they conduct their businesses on a verbal understanding among employees and management. These findings can be explained by reflecting on the study of Van Wyk and Venter (2022), who argued that:

In SMEs, the practice of business ethics is more informal, with no or few formal policies. It appears to be based on an internal or morally infused drive, with the owner central to it. (pp. 96-97)

Other participants defended this, citing that those employees currently in the business are regarded as partners with a vested interest in the business's success and formalising these guiding documents is not a priority. However, Lauria and Long (2019) did not fully agree with this approach, as they discovered that there is usually a conflict between personal ethical framework and professional setting ethical standards, suggesting the importance of having a guiding document to avoid such conflicts. Moreover, Bull and Ridley-Duff (2019) argued that entrepreneurs' interests differ from those who work with them in the organisation, making it necessary to have a guiding document to manage these differences. The lack of such documents may cause employees to struggle with ethics (Van Wyk & Venter 2022).

In addition to organisational policies, this study found that more advanced small businesses had technical mechanisms that helped to manage ethical misconduct. The organisations have quality measurement systems, trackers, biometric monitors and online data collection surveys to ensure that ethical principles are observed. Furthermore, the ethics discussions are incorporated into performance evaluation systems. Robinson and Jonker (2017) found that organisations had various operational mechanisms (e.g. accounting oversight, auditing practices, CCTV and GPS) to enforce ethical behaviours. While technology also provides prevention advantages, some people can bypass the system. Therefore, building strong organisational values and exemplary ethical leadership is critical to managing ethical misconduct.

Empirical model

This study aimed to investigate how entrepreneurs narrated the types and management of ethical misconduct in their businesses. Figure 1, which is this study's main contribution, shows how entrepreneurs and their business ventures are interrelated in the management of ethical misconduct. Moreover, the diagram shows the two types of ethical misconduct, as observed and directly experienced. The observed ethical misconduct does not directly affect entrepreneurs. Since there is no direct impact on entrepreneurs or their businesses, there is no need to manage the observed misconduct directly or actively. The observation of how other entrepreneurs struggle with ethical challenges reinforces entrepreneurs' response value systems. Entrepreneurs continue to live by their values, which influence their business response strategies.

In contrast, experienced ethical misconduct is directly encountered by entrepreneurs within and beyond their businesses. The first-hand experience of the ethical misconduct influences the direct application or enactment of entrepreneurs' response value systems. The entrepreneurs' values spill over into organisational response strategies. In response to the misconduct, small businesses can have selective engagement, develop and enact the organisational value systems, implement organisational policies and use technical detection and support measures.

Figure 1 shows that the observed ethical misconduct in the business environment could be directly experienced by entrepreneurs. As such, continuous reinforcement of their value systems might be a strategy to prepare them to deal with the potential ethical misconduct experiences. Lastly, the observed and experienced ethical misconduct indirectly influences the application of management strategies. This indirect influence is because of the integral role played by the entrepreneurs in shaping their organisations' value systems and other ethical management strategies. While the suggested conceptual model advances the understanding of ethical misconduct types and management in entrepreneurial businesses, it also provides an opportunity for testing using explanatory studies.

Conclusion

This study intended to establish entrepreneurs' narratives of ethical misconduct types and how they manage them within their businesses. The main contribution of this study, the empirical framework, shows the interrelatedness of the types of ethical misconduct, entrepreneurs' response value systems and the organisational response strategies. The conceptual model also helps to unpack the kinds of ethical misconduct and how they influence organisations' response strategies. The key finding is that entrepreneurs' values (e.g. honesty, integrity and respect) spill over into the organisations, thus influencing the organisational response strategies, such as selective engagement, organisational values, organisational policies and technical detection and support processes. Moreover, this study demonstrated that the type of ethical misconduct will influence entrepreneurs' value systems. This is aligned with the body of literature showing how entrepreneurs' identities are intertwined with their business activities. This study also drew from entrepreneurial leadership by showing that the top management team ought to conduct themselves in an exemplary manner. This kind of behaviour encourages employees to act ethically. Their kind of leadership further helps them have ethical and value-based engagements with various external stakeholders, such as partners, suppliers and customers.

This study has implications for entrepreneurs. Firstly, entrepreneurs should be intentional about the values they enforce in their businesses and consistently monitor that they are applied, as these are critical elements to (pre-)managing ethical misconduct in their companies. Secondly, they could find other creative mechanisms to ensure that compliance is not burdensome. Thirdly, entrepreneurs could use the suggested model to make sense of ethical misconduct and their management strategies. Fourthly, training institutions should continue providing business ethics training and support entrepreneurs to develop ethical (mis)conduct management tools. Lastly, the government should strive to provide a conducive business environment to support entrepreneurs and deal with institutional inadequacies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations and suggestions for future research. Firstly, the sample size was small, meaning the findings may not be a fair representation of the entire population. Secondly, the population was broad and not industry specific, which indicates that the industry generalisation is limited. Thirdly, the sample was restrictive and only catered to entrepreneurs with businesses operating for at least 3 years. The shortfall is the missed value of insight from newer and disruptive entrepreneurs. Fourthly, this study focused on the founders, thus excluding employees' perceptions. Fifthly, most of the study's participants identified as male, making the findings' ethical misconduct experience generalisability limited to other gender classifications. Lastly, some of the themes on the effectiveness of the policies and continuous improvement were not included as they were beyond the scope of the study.

Suggestions for future research

There are six suggestions for future research. Firstly, future research can be conducted on a larger sample size of entrepreneurs using quantitative methods. The larger sample size will contribute to the generalisability of the management of ethical misconduct. Secondly, since industries have different game rules, it could be beneficial for the study to be industry specific to determine the unique ethical challenges faced by entrepreneurs. Thirdly, future research could investigate ethical challenges faced by nascent or newly established firms. Fourthly, the study may explore reverse spillover, whereby employees influence entrepreneurs' and organisations' value systems and ethical misconduct management strategies. Fifthly, there is an opportunity to explore and compare how the different gender classifications experience and manage ethical misconduct. Lastly, this study provided an empirical model developed using qualitative data. Therefore, there is an opportunity to establish hypotheses and test the suggested conceptual model.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

This article is partially based on the author's thesis entitled "Established entrepreneurs' value system used to manage ethical dilemmas in the emerging markets" towards the degree of Master of Business Administration at the Gordon Institute of Business Science, The University of Pretoria, South Africa, on 01 December 2020 with supervisor(s) Anastacia Mamabolo. E.L. contributed to formulating the study's argument, data collection, analysis and writing the final research report. A.M. supervised the research and contributed to the conceptualisaton of the study. A.M. synthesised the literature review, re-analysed the data and converted the research report into a journal article. E.L. reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as data are not publicly available.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Adhabi, E. & Anozie, C.B., 2017, 'Literature review for the type of interview in qualitative research', International Journal of Education 9(3), 86-97. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v9i3.11483 [ Links ]

Bandura, A. & Walters, R.H., 1977, Social learning theory, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V., 2006, 'Using thematic analysis in psychology', Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Brown, J.A., Buchholtz, A.K. & Dunn, P., 2016, 'Moral salience and the role of goodwill in firm-stakeholder trust repair', Business Ethics Quarterly 26(2), 181-199. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2016.27 [ Links ]

Bull, M. & Ridley-Duff, R., 2019, 'Towards an appreciation of ethics in social enterprise business models', Journal of Business Ethics 159(3), 619-634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3794-5 [ Links ]

Chang, H.-H. & Lu, L.-C., 2019, 'Actively persuading consumers to enact ethical behaviors in retailing: The influence of relational benefits and corporate associates', Journal of Business Ethics 156(2), 399-416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3595-2 [ Links ]

Clandinin, D.J., Cave, M.T. & Berendonk, C., 2017, 'Narrative inquiry: A relational research methodology for medical education', Medical Education 51(1), 89-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13136 [ Links ]

Clarke, J. & Holt, R., 2010, 'Reflective judgement: Understanding entrepreneurship as ethical practice', Journal of Business Ethics 94(3), 317-331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0265-z [ Links ]

Clarke, T. & Boersma, M., 2017, 'The governance of global value chains: Unresolved human rights, environmental and ethical dilemmas in the Apple supply chain', Journal of Business Ethics 143(1), 111-131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2781-3 [ Links ]

Crane, A. & Matten, D., 2016, Business ethics: Managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the age of globalization, International edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Dey, P. & Steyaert, C., 2016, 'Rethinking the space of ethics in social entrepreneurship: Power, subjectivity, and practices of freedom', Journal of Business Ethics 133(4), 627-641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2450-y [ Links ]

Drover, W., Wood, M.S. & Fassin, Y., 2014, 'Take the money or run? Investors' ethical reputation and entrepreneurs' willingness to partner', Journal of Business Venturing 29(6), 723-740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.08.004 [ Links ]

Fryer, M., 2016, 'A role for ethics theory in speculative business ethics teaching', Journal of Business Ethics 138(1), 79-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2592-6 [ Links ]

Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L., 2006, 'How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability', Field Methods 18(1), 59-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903 [ Links ]

Hagel, J., III, 2016, 'We need to expand our definition of entrepreneurship', Harvard Business Review 28, 2-5. [ Links ]

Lauria, M. & Long, M.F., 2019, 'Ethical dilemmas in professional planning practice in the United States', Journal of the American Planning Association 85(4), 393-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1627238 [ Links ]

Lin, S.-H.J., Ma, J. & Johnson, R.E., 2016, 'When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing', Journal of Applied Psychology 101(6), 815-830. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000098 [ Links ]

Lingwati, E., 2020, 'Established entrepreneurs' value system used to manage ethical dilemmas in the emerging markets', Masters thesis, Dept. of Business Administration, Gordon Institute of Business Science. [ Links ]

Lingo, E.L., 2020, 'Entrepreneurial leadership as creative brokering: The process and practice of co-creating and advancing opportunity', Journal of Management Studies 57(5), 962-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12573 [ Links ]

Love, E., Salinas, T.C. & Rotman, J.D., 2020, 'The ethical standards of judgment questionnaire: Development and validation of independent measures of formalism and consequentialism', Journal of Business Ethics 161(1), 115-132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3937-8 [ Links ]

Mai, Y., Zhang, W. & Wang, L., 2019, 'The effects of entrepreneurs' moral awareness and ethical behavior on product innovation of new ventures: Evidence from China', Chinese Management Studies 13(2), 421-446. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-10-2017-0302 [ Links ]

Maitlis, S., 2012, 'Narrative analysis', in G. Symon & C. Cassell (eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges, pp. 492-511, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Mesdaghinia, S., Rawat, A. & Nadavulakere, S., 2019, 'Why moral followers quit: Examining the role of leader bottom-line mentality and unethical pro-leader behavior', Journal of Business Ethics 159(2), 491-505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3812-7 [ Links ]

Mmbaga, N.A., Mathias, B.D., Williams, D.W. & Cardon, M.S., 2020, 'A review of and future agenda for research on identity in entrepreneurship', Journal of Business Venturing 35(6), 106049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106049 [ Links ]

Mpinganjira, M., Roberts-Lombard, M., Wood, G. & Svensson, G., 2016, 'Embedding the ethos of codes of ethics into corporate South Africa: Current status', European Business Review 28(3), 333-351. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-04-2015-0039 [ Links ]

Munro, I. & Thanem, T., 2018, 'The ethics of affective leadership: Organising good encounters without leaders', Business Ethics Quarterly 28(1), 51-69. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.34 [ Links ]

Newman, A., Round, H., Bhattacharya, S. & Roy, A., 2017, 'Ethical climates in organizations: A review and research agenda', Business Ethics Quarterly 27(4), 475-512. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.23 [ Links ]

Pircher Verdorfer, A. & Peus, C., 2020, 'Leading by example: Testing a moderated mediation model of ethical leadership, value congruence, and followers' openness to ethical influence', Business Ethics: A European Review 29(2), 314-332. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12255 [ Links ]

Reynolds, J., Kizito, J., Ezumah, N., Mangesho, P., Allen, E. & Chandler, C., 2011, 'Quality assurance of qualitative research: A review of the discourse', Health Research Policy and Systems 9(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-9-43 [ Links ]

Robinson, B.M. & Jonker, J.A., 2017, 'Inculcating ethics in small and medium-sized business enterprises: A South African leadership perspective', African Journal of Business Ethics 11(1), 63-81. https://doi.org/10.15249/11-1-132 [ Links ]

Rochford, K.C., Jack, A.I., Boyatzis, R.E. & French, S.E., 2017, 'Ethical leadership as a balance between opposing neural networks', Journal of Business Ethics 144(4), 755-770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3264-x [ Links ]

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A., 2012, Research methods for business students, 6th edn., Pearson, Harlow. [ Links ]

Savur, S., Provis, C. & Harris, H., 2018, 'Ethical decision-making in Australian SMEs: A field study', Small Enterprise Research 25(2), 114-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2018.1480414 [ Links ]

Schaubroeck, J.M., Lam, S.S.K. & Peng, A.C., 2016, 'Can peers' ethical and transformational leadership improve coworkers' service quality? A latent growth analysis', Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 133, 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.02.002 [ Links ]

Senadheera, G.D.V.R., 2018, 'Values and trading ethics among Sri Lankan entrepreneurs: A historical analysis', South Asian Journal of Management 25(4), 7-27. [ Links ]

Shane, S. & Venkataraman, S., 2000, 'The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research', Academy of Management Review 25(1), 217-226. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791611 [ Links ]

Swartz, E.M., Amatucci, F.M. & Marks, J.T., 2019, 'Contextual embeddedness as a framework: The case of entrepreneurship in South Africa', Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 24(3), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946719500183 [ Links ]

Vallaster, C., Kraus, S., Lindahl, J.M.M. & Nielsen, A., 2019, 'Ethics and entrepreneurship: A bibliometric study and literature review', Journal of Business Research 99(C), 226-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.050 [ Links ]

Van Der Walt, F., Jonck, P. & Sobayeni, N.C., 2016, 'Work ethics of different generational cohorts in South Africa', African Journal of Business Ethics 10(1), 52-67. https://doi.org/10.15249/10-1-101 [ Links ]

Van Wyk, I. & Venter, P., 2022, 'Perspectives on business ethics in South African small and medium enterprises', African Journal of Business Ethics 16(1), 81-104. https://doi.org/10.15249/16-1-285 [ Links ]

Van Zyl, E. & Lazenby, K., 1999, 'Ethical behaviour in the South African organizational context: Essential and workable', Journal of Business Ethics 21(1), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006095930895 [ Links ]

Warren, D.E., Peytcheva, M. & Gaspar, J.P., 2015, 'When ethical tones at the top conflict: Adapting priority rules to reconcile conflicting tones', Business Ethics Quarterly 25(4), 559-582. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2015.40 [ Links ]

Zhu, Y., 2015, 'The role of qing (positive emotions) and li1 (rationality) in Chinese entrepreneurial decision making: A confucian ren-yi wisdom perspective', Journal of Business Ethics 126(4), 613-630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1970-1 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Anastacia Mamabolo

mamaboloa@gibs.co.za

Received: 29 June 2022

Accepted: 20 Oct. 2022

Published: 28 Feb. 2023