Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Commercii

versão On-line ISSN 1684-1999

versão impressa ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.23 no.1 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v23i1.1046

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Ethical leadership in relation to employee commitment in a South African manufacturing company

Jeremy Mitonga-Monga; Masase E. Mokhethi; Busisiwe S. Keswa; Boitumelo S. Lekoma; Leona X. Mathebula; Lindiwe F. Mbatha

Department of Industrial Psychology and People Management, College of Business Economics, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Ethically questionable practices have given rise to a tremendous interest in studying leaders' ethical behaviours, which have become a subject of interest for scholars and practitioners alike, and how they could affect employee loyalty positively

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between ethical leadership and organisational commitment in a South African steel industry.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Previous research on the influence of ethical leadership on employee commitment suggests that ethical leaders are those who inspire, motivate and foster an ethical culture that enhances the psychological connection and well-being of workers.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH, AND METHOD: This research was quantitative and employed a cross-sectional approach. The measuring instruments were the Ethical Leaders Behaviour Questionnaire and the Organisational Commitment Scale. A convenience sample (N = 200) was drawn from among permanent employees at South African steel manufacturing company. Correlation and multiple regression analyses were conducted.

MAIN FINDINGS: The results indicate that the participants' perceptions of ethical leadership related positively to the level that ethical leadership predicted organisational commitment.

PRACTICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The results of this study have interesting implications for management and human resource professionals, as they can use the information during leadership development training to promote and encourage ethical behaviour and psychological attachment among employees. The data might also be utilised to establish a culture of responsibility, which could increase employee dedication. Ethical leadership appeared as a crucial component of organisational commitment, which may result in reduced inclination to leave and absenteeism. The data might be used by management to enforce and encourage ethical behaviour, which could increase employee commitment.

CONTRIBUTION OR VALUE-ADDITION: The findings of this research will add to the body of knowledge about the relationship between ethical leadership and organisational commitment in the context of South African steel industry, while emphasising the practical implications for line managers and behavioural practitioners.

Keywords: affective commitment; continuous commitment; employee commitment; ethical leadership; normative commitment; South Africa.

Introduction

Ethical scandals and moral deficiencies, evident in society and organisations worldwide, have become trendy slogans that dominate news cycles, causing global turmoil (Mitonga-Monga & Flotman 2017:270; Suifan et al. 2020:410). The leaders of large international organisations (e.g. Facebook, Google, Uber, Samsung, etc.) have recently been under scrutiny owing to their unethical actions such as privacy breaches, bribery, as well as embezzlement scandals and harassment allegations (Hansen et al. 2013:436). Such ethically questionable practices have given rise to much interest in studying leaders' ethical behaviours, as it has become a subject of interest for scholars and practitioners alike. The oversight was undoubtedly owing to its unspoken nature that would usually go unnoticed until unethical behaviour or misconduct arose (Suifan et al. 2020:413). Even so, ethical leadership (EL) studies have been gaining momentum, with scholars and practitioners confirming its pertinent role to maintain high ethical standards, while holding employees responsible for ethical conduct (Zubair & Mujeeb 2022:17).

'Ethical leaders' refers to individuals who conduct themselves ethically, reflecting honesty, respect, fairness, integrity, respect, openness and democratic interaction (Mitonga-Monga 2020:485), which increase employees' commitment level. Organisational commitment (OC) refers to a psychological attachment that provides an employee with a stabilising or obligation force, which directs them towards specific organisational goals and values. Previous studies indicate that EL emerges as a contributor to work-related outcomes such as OC, job satisfaction and organisational citizenship behaviour, while discouraging negative ones such as turnover intention and absenteeism (Hartog 2015:412). However, it is unclear how the association would show in a developing country, with growing leadership deficiency, corruption and unethical malpractices. This research sought to investigate the relationship between EL and OC at a steel manufacturing company in a developing country such as South Africa.

Research context

Despite recent progress and its contribution to the local economy, the South African (SA) steel industry, on which we conducted our research, remains a strategic industry for South Africa, representing 1.5% of the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and accounting for some 190 000 jobs (Mail & Guardian 2016). Nevertheless, the SA steel company is facing the harmful effects of state capture, corruption and the impact of the coronavirus diease 2019 (COVID -19), which reduced steel demand by 27-30% in 2020 compared with 2019. Competition authorities found that the SA steel company engaged in anticompetitive behaviour and hence penalised the business with a R1.5 billion fine in 2016. The industry also experienced issues caused by market forces and struggled to meet high electricity, rail and port costs (Mail & Guardian 2016). However, the SA steel company has invested much in employee skill development as part of its talent management strategy; despite this investment, it still finds it challenging to retain key talent, while ensuring sustainability.

Theoretical perspectives

Ethical leadership

Much research has been conducted on business ethics, emphasising its role in developing good characteristics among individual employees to serve the prosperity and survival of both the organisation and its members (Qing et al. 2020:67). Generally, leaders are key role players to establish moral standards among their followers, while encouraging ethical behaviour that is favourable for communities and organisations (Isiramen 2021:11). The moral deficiency response to uncertain business practices under current COVID-19 pandemic circumstances has resulted in a great need for EL. It has become a topic of interest and inquiry (Demirtas & Akdogan 2015:183; Mitonga-Monga 2015:35-42). The EL refers to a 'demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships and the promotion of such conduct of followers through two-way communication' (Brown 2005:120). For instance, Tracy (2016) describes EL as behaviour that may motivate employees' sense of responsibility, tolerance, integrity and honesty. The EL is perceived to exhibit behaviours that are consistent with appropriate norms, perceptible through a leader's actions and relationships (Brown, Trevino & Harrison 2005:121; Ibrahim & Mayende 2018:2).

Ethical leaders are trustworthy, fair and principled decision-makers who lead their followers, equipped with ethical competencies and abilities (Hartog 2015; Mitonga-Monga 2020:485-491). They set clear ethical standards for their organisations and adhere to them (Babalola et al. 2016:1-2; Mitonga-Monga 2020:486). Literature identifies seven EL behaviours which are regarded as the most important components of EL (Kalshoven, Den Hartog & De Hoog 2011:51-69). Fairness refers to the extent to which a leader practises good judgement consistently and transparently when making decisions regarding employees (Mitonga-Monga & Cilliers 2016:38). Power-sharing refers to how a leader delegates power by involving followers in the decision-making process, allowing them to make autonomous decisions (Kalshoven & Den Hartoh 2009:104). Role clarification reflects a leader's ability to provide clear responsibilities and to communicate anticipated performance results from employees (De Hoogh & Den Hartog 2008:298). People orientation demonstrates a leader's ability to portray affection towards employees, while demonstrating a high level of developmental and empathetic traits (Avolio et al. 2004:811). Concern for sustainability involves the extent to which a leader considers the impact of a decision on the macro level and not only from an internal organisational perspective (Waldman, Siegel & Javidan 2006:1704).

Integrity refers to leaders who do what they say they will and who keep their promises. Leaders who are consistent and who fulfil their promises earn the trust and respect of their followers (Palanski & Yammarino 2009:406). Ethical guidance considers the extent to which a leader communicates moral norms and standards and, likewise, rewards ethical behaviour (Khalid & Bano 2015:67). When employees think that their boss is trustworthy, they are more likely to be engaged and to connect with the organisation's aims and values, trading their OC for the benefit of the organisation and for an ethical leader who is honest, respectful and altruistic. In addition, their commitment will prevent them from exiting the organisation (Imam & Kim 2022:2; Xu, Loi & Ngo 2016:493).

Organisational commitment

The OC concept is a topic of concern for both scholars and practitioners, and it has several definitions (Lee & Cha 2015:360). A standard definition of OC is embedded in the psychological bond (Allen & Meyer 1997:125-127; Mitonga-Monga & Flotman 2018:2) that enlightens employees' work behaviours. According to Ahadiat and Dacko-Pikiewicz (2020:24), OC measures employees' psychological attachment, level of involvement and identification with their job. This includes a work attitude which relates to employees' willingness to be fully involved in the organisation's activities and to remain loyal to the organisation (Mitonga-Monga 2020:486). Subsequently, such employees would be prepared to develop a penchant and emotional bond that is psychologically allied with the organisation's strategic intent (Mitonga-Monga & Flotman 2018:2).

Mamman, Kamoche and Bukuwa (2012:289) asserted that OC is a global and local commitment, characterised by varying unique and specific outcomes. Employee OC is therefore defined as a belief and feeling, which is formed internally or as a set of intentions that enhance an employee's desire to remain with the organisation and accept its goals and values (Etu & Tantua 2021:91). The OC is also perceived to be strong identification with an organisation, while being psychologically attached to it, inspiring employees to participate actively towards accomplishing the organisation's objectives (Mitonga-Monga & Flotman 2018:2).

This study used the three components of OC, which Alen and Meyer (1991:70-71) identified and which seem to be the most popular OC components (Mitonga-Monga 2020:486). These are affective commitment (showing an employee's identity, participation in and emotional connection to the organisation) and cognitive commitment (Allen & Meyer 1990:12). Continuance commitment reflects an individual's willingness to continue being a member of the organisation when evaluating leaving costs (Fayda-Kinik 2022:181). Normative commitment reflects an individual employee's devotion or moral obligation to remain in the organisation because it is the right and honourable thing to do (Mitonga-Monga & Flotman 2018:3).

Committed employees would likely want to stay in the organisation or extend their membership with the employer organisation (Mitonga-Monga 2015:35). Those employees with a solid continuance desire will likely remain with their organisation if they perceive their employer to be trustworthy (Mitonga-Monga 2020:486). Employees with a high normative level remain with their employer organisation because they believe it to be the moral thing to do (Fanggidae, Nursiani & Bengngu 2019:263). Previous studies by Suifan et al. (2020:2) argued that OC decreases work-related attitudes such as turnover intention and absenteeism.

Social exchange theory

This study used the framework of social exchange theory (SET) to comprehend the association between EL and OC (Mitonga-Monga 2020:485-486). Social exchange refers to the voluntary actions of persons who are driven by the anticipated and normal benefits they obtain from others (Blau 1964:91). Social exchange theory is a well-known theory of management that helps to explain workplace behaviour (Wang, Yen & Tseng 2015:451). It posited that exchange of resources happens via contact between two parties (Mitonga-Monga 2022:485). Mitonga-Monga, Van Lange and Balliet (2014:65) argued that social exchange is an interdependent relationship between two actors. It is a reciprocal transaction that requires something that is given and returned. Tan, Zawawi and Aziz (2016) posited that social behaviour is a kind of exchange, comprising material and nonmaterial outputs. Social exchange occurs when the interactions between two actors lead to an emergence of a sense of obligation to reciprocate each other even though the nature of the reciprocation is not clarified (Cropanzano & Mitchell 2005:876). The rule of thumb in the exchange process is to form an exchange relationship, which is the reciprocation behaviour triggered to respond to the favour given by the initial actor (Mitonga-Monga 2020:485). The absence or nonexistence of reciprocity would cause the social interaction to rupture (Lee, Mohamad & Ramayah 2010:316-345).

The social exchange begins when one actor takes the initiative to show kindness and offer benefits, while the other reciprocates by returning the favour (Cropanzano et al. 2017:478-480). This article argues that ethical leaders who treat employees fairly, delegate power, demonstrate empathy, consider the impact of their decisions, communicate moral norms and initiate the social exchange process. When employees perceive their leaders to be ethical, they find the organisation a desirable entity with which to affiliate (Cropanzano & Mitchell 2005:874). Following SET (Blau 1964; Lioukas & Reuer 2015:1827), employees who perceive their leader to be ethical are likely to be involved in social transactions; they interchange their OC for the benefit of their moral leader's fairness, respect and honesty. Hence, they would extend their stay with the organisation (Mamman, Kamoche & Bukuwa 2021:286).

Relationship between ethical leadership and organisational commitment

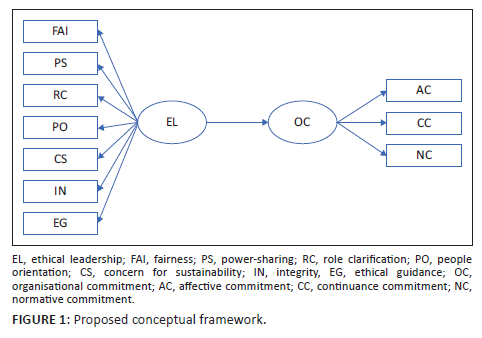

Previous research on EL and OC demonstrates that there is a strong positive relationship between the two constructs (Agha, Nwekpa & Eze 2017:202-214; Ahadiat & Dacko-Pikiewicz 2020:24-35; Hidayati et al. 2019:256; Mitonga-Monga & Cilliers 2016:35-42; Priya 2016:42-50; Sharma, Agrawal & Khandelwal 2019:712-734). For example, Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (2016:35) found a positive relationship between EL and OC. Ahadiat and Dacko-Pikiewicz (2020:24) and Mitonga-Monga (2020:485) agreed that seven characteristics of EL (people orientation, fairness, power-sharing, role clarity, concern for sustainability, integrity and ethical guidance) have a substantial impact on organisational culture.

In line with Qureshi and Butt (2020:67-69), the effects of EL on OC from the SET as an intervening variable between organisational resources and work-related attitudes are often reciprocal (Loi et al. 2015:645). For example, employees who perceive their leader to be ethical, regard them as being impartial and rational in decision-making, communicate the expected performance of sustainable organisational goals and take care of their well-being. They will likely be loyal, involved and identify with the organisation's goals and values. In other words, EL that makes and creates more meaningful work for followers is likely to facilitate employees' identification with and loyalty to the organisation and their respective performance (Hansen et al. 2013:435-449; Mamman et al. 2021:285), lowering desire to leave and absenteeism (Chabib 2016:63). Given the link between EL and OC, it is hypothesised that EL would have a favourable and substantial association with OC.

Aim of the study

The purpose of this research was to examine the link between workers' views of EL and OC in the context of the South African (SA) steel industry. The research question that guided the investigation was formulated as follows: how do employees' perceptions of leaders' ethical behaviour relate to their level of OC in a SA steel industry organisation? The researchers anticipated that the results would contribute to the ongoing debate around these two constructs (EL and OC) and possibly employees' retention strategies in the industry.

Method

Design and participants

This study used a quantitative research approach and employed a cross-sectional survey design. Cross-sectional research proves relationships among variables and can be used to rule out any possible alternative explanations for these relationships (Spector 2019:125-126). Convenience sampling (N = 200), using Raosoft (Raosoft, Inc., Seattle, Washington, United States) at a 95% confidence level, 5% of margin of error. A sample of 130 was drawn, which yielded a response rate of 65%. The sample comprised 40% women in middle adulthood (31-40 years), and of these, 51.5% were single, 96.2% were black, 36.2% had university qualifications and most had between 2 and 5 years of work experience in the industry.

Data collection

The study used the Ethical Leadership Work Questionnaire (ELWQ) (Kalshoven & De Hoog 2011) and the Organisational Commitment Scale (OCS) (Meyer & Allen 1997) as research measurement tools. The demographics section of the questionnaire evaluated the following: gender (male or female) age, ethnicity (African, Indian, mixed race, white) and tenure in the organisation.

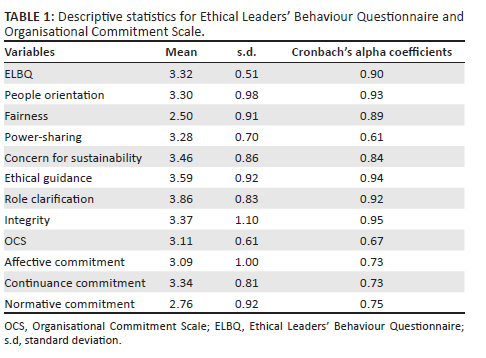

The ELWQ is a 38 item self-report instrument, which uses a five-point Likert scale varying from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Examples of the items include: people orientation ('is interested in how I feel and how I am doing'); fairness ('holds me accountable for problems over which I have no control'); power-sharing ('allows subordinates to influence critical decisions'); concern for sustainability ('would like to work in an environmentally friendly manner'); ethical guidance ('clearly explains integrity related codes of conduct'); role clarification ('indicates the performance expectations of each group member'); and integrity ('keeps his or her promises'). Kalshoven et al. (2011:57) reported a Cronbach's alpha coefficient which ranged from 0.70 to 0.95 for the Ethical leader behaviour questionnaire (ELBQ). The present study obtained Cronbach's alpha coefficients which ranged from 0.61 to 0.95 for the ELBQ.

The OCS is a 24-item self-report instrument that uses a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). It measures employees' perceptions of their affective, continuance and normative commitment. The OCS includes the following examples: Affective ('I really feel as if this organisation's problems are my own'); continuance ('it would be very hard for me to leave my organisation right now even if I wanted to'); and normative ('I would feel guilty if I left my organisation now'). Meyer and Allen (1997:187) reported an internal consistency Cronbach's alpha, ranging from 0.75 to 0.79 for the OCS. The present study obtained Cronbach's alpha coefficients, ranging from 0.67 to 0.75 for the OCS.

Data analysis

The study's data were analysed, using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 27 (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States), which yielded means, standard deviations, internal consistency, reliability, correlations and multiple regression analyses. Correlations were used to determine the association between EL and OC. Multiple regression analyses were used to determine if EL is a predictor of OC. To prove statistical significance and reduce the likelihood of type 1 errors, the researchers selected the statistical significance cut-off value at p ≤ 0.05 and that practical effect size r = 0.30-0.50 (medium to large effect size).

Ethical consideration

Before commencing with the study, the researchers obtained permission from the University of Johannesburg's High Research Ethics Review Committee (reference number IPPM-2020-441) and the organisation's management. The participants received an electronic link for the survey. However, before completing it, they were asked to complete an informed consent form to participate willingly in the study project by completing a demographic questionnaire (requesting the participant's gender, age, education, marital status, racial group and length of service in the industry) in addition to the ELBQ and OCS. Participants were required to electronically sign the permission form and complete the ELBQ and OCS.

Results

Descriptive statistics: Mean standard deviation, correlations analysis and Cronbach's alpha coefficients

This section reports on the means, standard deviations and the Cronbach's alpha for the EL and OC variables. In terms of the ELBQ, Table 1 shows that the mean scores ranged from M = 3.86 to M = 2.50. The sample of participants obtained a high mean score for the role clarification (M = 3.86; s.d. = 0.83) variable, followed by ethical guidance (M = 3.59; s.d. = 0.92), concern for sustainability (M = 3.46; s.d. = 0.86), integrity (M = 3.37; SD = 1.10), total EL (M = 3.32; s.d. = 0.51) and people orientation (M = 3.30; s.d. = 0.98), while the lowest mean score was attained for the fairness (M = 2.50; s.d. = 0.91) variables.

In terms of the OCS, Table 1 shows that the mean scores ranged from M = 3.34 to M = 2.76. The sample of participants obtained a relatively high mean score for the continuance commitment (M = 3.34; s.d. = 0.81) variable, followed by total employee commitment (M = 3.11; s.d. = 0.61) and affective commitment (M = 3.09; s.d. = 1.00), while the lowest mean score was attained for the continuance normative commitment (M = 2.50; s.d. = 0.91) variables.

Correlations

Correlations between EL and OC were calculated. To assess the likelihood of Type 1 errors, the significance value was determined at a 95% confidence level. (p ≤ 0.05) was established level and a cut-off practical effect size was r ≥ 0.30 to r ≥ 0.50 (medium to large effect size) (Hair et al. 2019). Table 2 illustrates the correlations between ELBQ and OCS. The findings indicate that ELBQ correlates significantly and positively with OCS (r = 0.38; medium effect size; p ≤ 0.05). The results also indicate that ELBQ correlated significantly with affective commitment (r = 0.38; medium effect size; p ≤ 0.05) and normative commitment (r = 0.54; large effect size; p ≤ 0.05).

Multiple regression analysis

Table 3 indicates the multiple regression results.

It was determined that the regression models were statistically significant (p < 0.05) because the model explained 21% of the variation (R2 = 21; p ≤ 0.001) in the total OC variable. In Model 1, Table 3 revealed that people-orientation (β = 0.49; p = 0.001) and fairness (β = 0.31; p = 0.001) functioned as substantial positive predictors of total OC, with people-orientation and fairness accounting for the largest variation in OC.

In Table 3, Model 2 (affective commitment) revealed that people orientation (β = 0.49; p = 0.001) served as significant positive predictors of affective commitment, with fairness contributing the most to the variation in affective commitment.

Table 3's Model 4 (normative commitment) showed that individuals' orientation (β = 0.50; p = 0.001) and fairness (β = 0.42; p = 0.001) served as substantial positive predictors of normative commitment, with people orientation and fairness providing the greatest variance to normative commitment.

Table 3 presents the outcomes of the multiple regression analyses undertaken to determine if EL positively and substantially predicts emotional and normative commitment, respectively. Models 2 and 4 display the findings. The findings in Table 3 led to the development of two more regression models, all of which were statistically significant (Fp ≤ 0.05). The models accounted for 38% (R2 = 0.36 for emotional commitment and 12% (R2 = 0.12 for normative commitment) of the variation across variables of these two subdimensions of OC.

Discussion

This study sought to examine the relationship between employees' perceptions of EL and OC within a South African steel industry context. Firstly, the objective was to determine whether EL relates significantly to OC, and whether EL is a predictor of OC in this industry.

The results showed that employees perceived a higher level of EL. This implies that their leaders provided clear responsibilities and communication, displayed moral norms and standards, involved them in decision-making, made and kept their promises and were consistent and transparent in their practices. The findings are consistent with those of Ahadiat and Dacko-Pikiewicz (2020:24-35), who found that employees who work under leaders who inspire them to contribute significantly to the formation of a feeling of honesty and sincerity, transparency and trustworthiness tend to emulate their leaders' behaviour and hence act ethically when interacting with their colleagues.

The correlation results revealed that EL correlated positively with OC. The correlation results indicated that EL is associated with OC, which implies that employees who perceived that their ethical leader was concerned about their well-being and treated them with respect and fairness are likely to be involved and identify with the organisation's norms, goals and values. The findings support Ahadiat and Dacko-Pikiewicz (2020:24-35) and Mitonga-Monga (2020:486), who assert that ethical leaders exhibit power-sharing, fairness, people-orientation, integrity, concern for sustainability and ethical guidance, which may increase employees' level of commitment to the organisation. The second objective, namely people orientation, correlated with affective and normative commitment. This suggests that when employees perceive their ethical leader to be empathetic and show concern for their well-being, they will likely be emotionally attached to and obligated to stay with the employer's organisation. These findings align with those shared by Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (2016:35-42), who found people orientation to relate to affective and normative commitment.

The results suggest that concern for the environment and its future, role clarification, ethical guidance and integrity correlated with normative commitment. The suggestion here is that workers will be loyal to the organisation and remain with it when they perceive ethical behaviours from their leader, which include: considerate decision-making, clear orientations for performance, rewards for ethical behaviour and maintaining promises. These findings support those of Hidayati et al. (2019:256, 266) and Imam and Kim (2020), who found concern for sustainability, role clarification, ethical guidance and integrity to relate to normative commitment.

The findings suggest that people orientation is linked positively to both affective and normative commitment. Employees are more likely to be emotionally linked to, and obligated to stay with, their ethical leaders if they believe that they are willing and able to empathise with others, exhibit care for them and portray ethical attributes. These findings align with those shared by Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (2016:35), who found EL to relate to affective and normative commitment.

The findings suggest that fairness correlated negatively with normative commitment, implying that when employees perceive their ethical leaders to lack transparency, exercise favouritism and treat them unfairly, they will likely leave the employer's organisation. This finding contradicts the results of Brown et al. (2005:117-134) and Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (2016:35-42), who found that fairness correlated positively with normative commitment. Moreover, no significant correlations were found between the EL aspects of individuals and groups integrity, direction, fairness, power-sharing, concern for long-term sustainability, ethical instruction and role clarity for continuance commitment. Nevertheless, other research proposes that ethical leaders who exhibit positive behaviours that promote a pleasant or ethical working environment would motivate employees to stay with the organisation (Mitonga-Monga & Cilliers 2016:35-37).

The second objective sought to determine if EL positively and significantly predicted OC. The multiple regression results revealed that EL did indeed predict OC. The third objective determined whether the seven features of EL, namely people orientation, fairness, power-sharing, concern for sustainability, ethical guidance, role clarification, and integrity positively and significantly predicted the three dimensions of OC, namely affective, continuance and normative commitment. The results revealed that people orientation and fairness contributed more towards the differences in employees' levels of affective and normative commitment (Hidayati et al. 2019:256:266). The results revealed that people orientation predicted affective commitment. This can be explained by the fact that when employees perceive their ethical leader to conduct himself or herself in an ethical manner, show genuine care and treat them with respect, they will likely demonstrate a strong emotional attachment to the organisation.

This result is congruent with findings of Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (2016:35-42), who found that EL affects emotional commitment. Furthermore, the data imply that EL (people orientation, fairness) predicted normative commitment. This may be explained by the fact that when workers consider their ethical leader to be helpful and guarantee that their needs are addressed, then they will likely feel a feeling of commitment towards the firm and will remain with the employer because it is ethically correct to do so. These results correlate with those of Hansen et al. (2013:435-449), who imply that workers who are treated fairly are inclined to invest in the business.

Implications for management practices

The limitations of this study must be recognised when assessing its results. Firstly, the research was limited to 130 employed steel industry workers in South Africa. A method of convenience sampling was utilised to pick the participants. The study's conclusions cannot be extended to other demographics and jobs. Similar quantitative studies should be undertaken with a wider sample of SA steel sector personnel if the results are to be generalised.

Secondly, the cross-sectional design of this study makes it difficult to draw conclusions on the cause-and-effect relationship between EL and OC factors. Consequently, the results were interpreted rather than proven. Thirdly, OC as a whole and a subdimension of EL, namely power-sharing, yielded poor coefficients of dependability. Prior study established the psychometric features of these assessments in a different environment; hence, this poor reliability score may be attributed to the small sample size.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, the study was restricted to 130 employed South African steel industry employees. A convenience sampling technique was used to select the participants. Hence, the results of this study cannot be generalised to other populations and different occupations. If the findings are to be generalised, similar quantitative studies should be conducted with a larger sample of employees in the SA steel industry.

Secondly, this study used a cross-sectional research design, making it difficult to draw inferences about the cause-and-effect relationship between EL and OC variables. Therefore, the findings were interpreted rather than established. Thirdly, overall OC and a subdimension of EL, namely power-sharing, produced a low-reliability coefficients score. This low-reliability score can be ascribed to the size of the sample, as prior research established the psychometric properties of these measurements in a different context.

Future studies

This study ascertains a crucial need for future research in the relationship between EL and OC. It is recommended that further research should use different methods and designs to address limitations identified in this study. The study was restricted to 130 employees who work in the SA steel industry. Future research should use different sampling techniques with a large sample from various occupational and demographical (i.e. race, gender and age, educational level and seniority) facets.

This study used a cross-sectional research design; therefore, it was impossible to determine the cause-effect relationship between EL and OC. Future researchers should use longitudinal studies to assess the effect of ethical leaders' behaviours and OC in different industries. This study produced low reliability; future studies should conduct test-retest reliability to validate the reliability of the used measurements. Ethical leaders' behaviour did not predict continuance commitment; therefore, future researchers should also use combined research approaches such as qualitative and quantitative tools, which should help them understand the relationship between EL and OC. Furthermore, demographic variables such as race, gender, age, educational level and seniority should be explored as mediating-moderating variables in the relationship between EL and OC.

Conclusion

This study's purpose was to determine the relationship between EL and OC and to establish whether EL significantly predicted OC. The empirical statistical investigation in the relationship between EL and OC provided a new understanding of employees' psychological attachment, loyalty and commitment in the steel industry.

This study shows that ethical leaders' behaviour with regard to people-orientation and fairness is crucial for understanding emotional and normative commitment. Employees who view that their moral leader cares about their well-being and treats them fairly are more likely to feel emotionally tied to their company and feel a feeling of duty to maintain their membership.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shamila Sulayman for her language editing services.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

J.M.M. conceptualised and analysed data and wrote the article. M.E.M. analysed the data, contributed to the literature review and provided the admin support to finalise the article. B.S.K., B.S.L., L.X.M. and L.F.M. contributed to the report for their research project and were responsible for the collection and transcribing of data.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data cannot be made available to protect the anonymity of the participants.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Agha, N.C., Nwekpa, K.C. & Eze, O.R., 2017, 'Impact of ethical leadership on employee commitment in Nigeria - A study of Innoson Technical and Industrial Company Limited Enegu, Nigeria', International Journal of Development and Management Review 12(1), 202-214. [ Links ]

Ahadiat, A. & Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z., 2020, 'Effects of ethical leadership and employee commitment on employees' work passion', Polish Journal of Management Studies 21, 24-35. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2020.21.2.02 [ Links ]

Allen, N. & Meyer, J., 1990, 'The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organisation', Journal of Occupational Psychology 63(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x [ Links ]

Avolio, B.J., Gardner, W.L., Walumbwa, F.O., Luthans, F. & May, D.R., 2004, 'Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors', The Leadership Quarterly 15(6), 801-823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003 [ Links ]

Babalola, M., Stouten, J., Euwema, M. & Ovadje, F., 2016, 'The relation between ethical leadership and workplace conflicts: The mediating role of employee resolution efficacy', Journal of Management 45(5), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316638163 [ Links ]

Blau, P.M., 1964, Exchange and power in social life, John Wiley, New York. [ Links ]

Brown, M.E., Treviño, L.K. & Harrison, D.A., 2005, 'Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing', Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97(2), 117-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002 [ Links ]

Chabib, S., 2016, 'Study on organisational commitment and workplace empowerment as predictors of organisation citizenship behaviour', International Journal of Management & Development 3(3), 63-73. https://doi.org/10.19085/journal.sijmd030301 [ Links ]

Coetzee, M., Mitonga-Monga, J. & Swart, B., 2014, 'Human resource practices as predictors of engineering staff's organisational commitment', SA Journal of Human Resource Management 12(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v12i1.604 [ Links ]

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E.L., Daniels, S.R. & Hall, A.V., 2017, 'Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies', The Academy of Management Annals 11(1), 479-516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099 [ Links ]

Cropanzano, R. & Mitchell, M.S., 2005, 'Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review', Journal of Management 31(6), 874-900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602 [ Links ]

De Hoogh, A.H.B. & Den Hartog, D.N., 2008, 'Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader's social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates' optimism: A multi-method study', Leadership Quarterly 19(3), 297-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.03.002 [ Links ]

Demirtas, O. & Akdogan, A.A., 2015, 'The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment', Journal of Business Ethics 130(1), 59-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2196-6 [ Links ]

Fanggidae, R.E., Nursiani, N.P. & Bengngu, A., 2019, 'The influence of reward on organizational commitment towards spirituality workplace as a moderating variable', Journal of Management and Marketing Review 4(4), 260-269. https://doi.org/10.35609/jmmr.2019.4.4(5) [ Links ]

Fayda-Kinik, F.S., 2022, 'The role of organisational commitment in knowledge sharing amongst academics: An insight into the critical perspectives for higher education', International Journal of Educational Management 36(2), 179-193. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2021-0097 [ Links ]

Hansen, D., Alge, B.J., Brown, M.E., Jackson, L.C. & Dunford, B.B., 2013, 'Ethical leadership: Assessing the value of a multifocal social exchange perspective', Journal of Business Ethics 115(3), 435-449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1408-1 [ Links ]

Hartog, D.N.D., 2015, 'Ethical leadership', Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2(1), 409-434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111237 [ Links ]

Hidayati, T., Lestari, D., Maria, S. & Zainurossalamia, S., 2019, 'Effect of employee loyalty and commitment on organizational performance with considering role of work stress', Polish Journal of Management Studies 20(2), 256-266. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2019.20.2.21 [ Links ]

Ibrahim, A.M. and Mayende, S.T., 2018, 'Ethical leadership and staff retention in Uganda's health care sector: The mediating effect of job resources', Cogent Psychology 5(1), 1466634. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1466634 [ Links ]

Imam, A. & Kim, D.Y., 2022, 'Ethical leadership and improved work behaviours: A moderated mediation model using prosocial silence and organisational commitment as mediators and employee engagement as moderator', Current Psychology 158, 547-565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02631-5. [ Links ]

Isiramen, O.M., 2021, 'Ethical leadership and employee retention', International Journal of Business Management 4(12), 10-26. [ Links ]

Kalshoven, K. & Den Hartog, D.N., 2009, 'Ethical leader behavior and leader effectiveness: The role of prototypicality and trust', International Journal of Leadership Studies 5(2), 102-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007 [ Links ]

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D.N. & De Hoogh, A.H.B., 2011, 'Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure', Leadership Quarterly 22(1), 51-69. [ Links ]

Khalid, K. & Bano, S., 2015, 'Can ethical leadership enhance an individual's task initiatives?', Journal of Business Law & Ethics 3(1), 62-84. https://doi.org/10.15640/jble.v3n1a4 [ Links ]

Lioukas, C.S. & Reuer, J.J., 2015, 'Isolating trust outcomes from exchange relationships: Social exchange and learning benefits of prior ties in alliances', Academy of Management Journal 58(6), 1826-1847. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0934 [ Links ]

Lee, J.S., Back, K.J. & Chan, E.S., 2015, 'Quality of work life and job satisfaction among frontline hotel employees: A self-determination and need satisfaction theory approach', International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 27(5), 768-789. https://doi/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2013-0530 [ Links ]

Loi, R., Lam, L.W., Ngo, H.Y. & Cheong, S., 2015, 'Exchange mechanisms between ethical leadership and affective commitment', Journal of Managerial Psychology 30(6), 645-658. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-08-2013-0278 [ Links ]

Mail & Guardian, 2016, 'Preserving the South African steel industry is pivotal for growth', Mail & Guardian, viewed 15 September 2016, from https://mg.co.za/article/2016-09-15-preserving-the-south-african-steel-industry-is-pivotal-for-growth. [ Links ]

Mamman, A., Kamoche, K. & Bakuwa, R., 2012, 'Diversity, organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior: An organizing framework', Human Resource Management Review 22(4), 285-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.12.003 [ Links ]

Meyer, J.P. & Allen, N.J., 1997, Commitment in the Workplace Theory, Research, and Application. 2nd edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks. [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J., 2015, 'The effects of ethical context and behaviour on job retention and performance-related factors', Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J., 2018, 'Perceived ethical behaviour of leaders in relation to employees' job satisfaction in a railway organisation in a developing-country setting', Journal of Contemporary Management 15(1), 447-466. [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J., 2020, 'Social exchange influences on ethical leadership and employee commitment in a developing country setting', Journal of Psychology in Africa 30(6), 485-491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1842587 [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J. & Cilliers, F., 2016, 'Perceived ethical leadership: Its moderating influence on employees' organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours', Journal of Psychology in Africa 26(1), 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2015.1124608 [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J. & Flotman, A.P., 2017, 'Gender and work ethics culture as predictors of employees' organisational commitment', Journal of Contemporary Management 14(1), 270-290. [ Links ]

Mitonga-Monga, J., Flotman, A.P. & Cilliers, F., 2018, 'Job satisfaction and its relationship with organisational commitment: A Democratic Republic of Congo organisational perspective', Acta Commercii 18(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v18i1.578 [ Links ]

Palanski, M.E. & Yammarino, F.J., 2009, 'Integrity and leadership: A multi-level conceptual framework', The Leadership Quarterly 20(3), 405-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.008 [ Links ]

Pallant, J., 2020, SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS, 7th edn., Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Priya, L.D., 2016, 'Impact of ethical leadership on employee commitment in its companies', Madras University Journal of Business and Finance 4(1), 42-50. [ Links ]

Qing, M., Asif, M., Hussain, A. & Jameel, A., 2020, 'Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment', Review of Managerial Science 14(6), 1405-1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00340-9 [ Links ]

Qureshi, Q.Z. & Butt, M., 2020, 'Mediating effect of perceived organisational support on the relationship between leader- member exchange and the innovation work behaviour of nursing employees: A social exchange perspective', Business Innovation and Entrepreneurship Journal 2(1), 67-76. https://doi.org/10.35899/biej.v2i1.63 [ Links ]

Sharma, A., Agrawal, R. & Khandelwal, U., 2019, 'Developing ethical leadership for business organizations: A conceptual model of its antecedents and consequences', Leadership & Organization Development Journal 40(6), 712-734. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2018-0367 [ Links ]

Spector, P.E., 2019, 'Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional design', Journal of Business and Psychology 34(2), 125-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8 [ Links ]

Suifan, T.S., Diab, H., Alhyari, S. & Sweis, R.J., 2020, 'Does ethical leadership reduce turnover intention? The mediating effects of psychological empowerment and organizational identification', Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 30(4), 410-428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2019.1690611 [ Links ]

Tan, J.X., Zawawi, D. & Aziz, Y.A., 2016, 'Benevolent leadership and its organisational outcomes: A social exchange theory perspective', International Journal of Economics and Management 10(2), 343-364. [ Links ]

Tracy, A.J., 2016, 'The correlation of head football coach's authentic leadership factor with degree of team success', Doctoral dissertation, Capella University, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (UMI No. 10196142). [ Links ]

UGU, G.E. & Tantua, E., 2021, 'Ethical leadership and organisational commitment of Oil Servicing Company in Rivers State', International Journal of Management Sciences 8(6), 91-104. [ Links ]

Waldman, D.A., Siegel, D.S. & Javidan, M., 2006, 'Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility', Journal of Management Studies 43(8), 1703-1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00642.x [ Links ]

Wang, H.K., Yen, Y.F. & Tseng, J.F., 2015, 'Knowledge sharing in knowledge workers: The roles of social exchange theory and the theory of planned behavior', Innovation 17(4), 450-465. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2015.1129283 [ Links ]

Xu, A.J., Loi, R. and Ngo, H.Y., 2016, 'Ethical leadership behavior and employee justice perceptions: The mediating role of trust in organization', Journal of Business Ethics 134(3), 493-504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2457-4 [ Links ]

Zubair, A. & Mujeeb, A., 2022, 'Role of perceived ethical leadership and integrity in willingness to report ethical problems among police employees', Foundation University Journal of Psychology 6(1), 16-25. https://doi.org/10.33897/fujp.v6i1.208 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Masase Mokhethi

evem@uj.ac.za

Received: 14 Apr. 2022

Accepted: 28 July 2022

Published: 15 Feb. 2023