Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Commercii

versão On-line ISSN 1684-1999

versão impressa ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.22 no.1 Johannesburg 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v22i1.1033

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Perceived work values, materialism and entitlement mentality among Generation Y students in South Africa

Emmanuel Nkomo

Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, School of Business Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: In 2016, South Africa found itself gripped by what appeared to be spontaneous but violent demonstrations by groups of university students who were demanding free university education. Negotiations with the students did not appear to yield positive results

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The present article attempted to examine the factors associated with an entitlement mentality from a sample of students in two tertiary institutions in South Africa

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Demonstrations by university students have been recurrent since 2016. The argument presented in this article is that if people's expectations far outpace what authorities are able to offer, rising frustrations might lead to rising entitlement and that such entitlement can influence workplace behaviour.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: The quantitative study used a cross-sectional design to collect data from a sample of tertiary students who by their birth years belong to Generation Y (n = 519). Structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Amos version 25. The independent t was used to compare two means between men and women on materialism and entitlement mentality.

MAIN FINDINGS: The results suggested that Generation Y's sense of entitlement is high and that they also have high levels of materialism values. Structural equation modelling was used to explore associations between perceived work values, materialism and entitlement mentality. Exploitative entitlement was found to be positively related to two dimensions of work values, namely independence and enjoyment but not related to materialism. Nonexploitative entitlement was found to be significantly related to independence, leisure and materialism

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Human resource practitioners and line managers need to pay attention to work-life balance, as research has shown that Generation Y values independence and enjoyment in the workplace and that it has implications for their vocational behaviour. Understanding of the determinants of entitlement mentality can be helpful as several managers have indicated a frustration with employees who have high work expectations but are not prepared to work hard.

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: Recommendations are offered to assist both managers and policymakers on how to deal with vocational expectations of the youth.

Keywords: Generation Y; materialism; entitlement mentality; work values; rising expectations.

Introduction and rationale

In 2016, South Africa experienced countrywide demonstrations by university students in what became known as the '#FeesMustFall' demonstrations. These demonstrations were violent and resulted in damage to property (Calitz & Fourie 2016). The main demand made by these students was that government must provide them with free university education. In a different context, as far back as 1973, Sennett's (1973) seminal article identified educational achievement as the principal source of entitlement mentality among Americans, and that the educated are more likely to feel entitled to a job than the less educated. Sennett's proposition can be linked with Davis' (1969) theory of rising expectations, which predicts the creation of a social gap when people's expectations outpace what the government of the day is able to provide. The sense of entitlement has been described as a 'pervading sense that one deserves more and is entitled to more than others' (Campbell et al. 2004:31), and an entitlement mentality has typically been linked to younger generations (Lessard et al. 2011). Recent studies (see Kasser 2010; Nkomo 2017) have linked the sense of entitlement mentality among the youth to materialism, which has been defined as the importance one attaches to material possessions. Material possessions have become cultural symbols of identity, which represent status in society (Pechurina 2020). Generational cohort theory has been used to interpret the creation of long-lasting value systems by some significant national and international events, resulting in the formation of new shared behaviours among the cohort (Smola & Sutton 2002). Research shows every generation develops its own unique behaviours reflecting changes that have taken place within the social settings of each cohort (Hoxha & Zeqiraj 2019). Because younger generations are schooled in an era in which group work and group assignments have become commonplace, they have been found to prefer social aspects of work, such as fun work environments and friendly coworkers (Kilber, Barclay & Ohmer 2014).

This article therefore attempts to link entitlement mentality and materialism with the vocational expectations of a Generation Y university student cohort in the South African context. This was done through the development and testing of a theoretical model linking entitlement mentality with vocational expectations of Generation Y. In doing so, an argument is presented that understanding the influence of entitlement mentality as a potential determinant of work behaviour can make an important contribution to understanding the needs and behaviours of Generation Y students in this context.

With Generation Y now comprising a large proportion of the labour market, much literature provides different views of differences between generational cohorts (Martins & Martins 2012). Many studies have sought to understand generational personality through the study of generational differences (Grow & Yang 2018; Lazanyi & Bilan 2017). This study, however, focused on Generation Y in order to get some insights into their vocational expectations.

An important challenge facing South Africa today is youth unemployment. In spite of well-intentioned governmental policies, unemployment levels in the youth age group have persisted around 30% - 50% (Statistics South Africa [SSA] 2013). Unemployment, particularly of the most vulnerable, in the country was also exacerbated by the 2008 global financial crisis.

As would be expected, vulnerable groups, who include young people, were among the worst affected by this crisis. Figures from SSA (2013) show that unemployment rates among the youth prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic had increased to around 60%. Currently, the world is grappling with one of the worst health pandemics that has ever been seen. The pandemic is likely to worsen the situation for developing countries as they strive to deal with unemployment. Given the above, coupled with the potential effects of an entitlement mentality often associated with Generation Y, South Africa is faced with a likely volatile future, as these young people may feel that the only way to change the status quo lies with engaging in protests (Bloom 2012b). It has been observed the world over that when young people's skills and ambitions are underutilised, there is always a possibility of a revolution taking place (Bloom 2012b).

Davis's (1969) revolution of rising expectations suggests that in a country that has seen some economic growth for long periods of time, and people are free to express themselves, if this growth is followed by a sharp decline in economic activities, a social gap is created between people's expectations and what the government offers. As this gap widens, this can result in frustration, leading to some civil unrest. The above scenario can be compared to what has happened in South Africa since the advent of democracy in 1994. The South African economy has recorded a positive growth rate of 3.3% per annum from 1994 until 2012 (Industrial Development Corporation [IDC] 2016). However, in the past decade, the South African economy has not performed as well as expected. In recent years, the South African economy has experienced a declining growth, with GDP increasing by only 0.3% on a year-on-year basis over the first half of 2016 (IDC 2016), and because of the pandemic, the economy finds itself under renewed pressure.

In his seminal article on the American situation, which could be compared to what is happening in South Africa today, Derber (1978) argues that if there are many unemployed young people in a country, a group of disgruntled, unemployed individuals could be created. According to Derber, these young people's frustration is likely to manifest in political reactions which could be considered radical.

The present study therefore seeks to, firstly, investigate whether Generation Y display relatively high levels of entitlement mentality. Entitlement has been widely researched upon in recent years and most studies suggest that it has societal negative effects (Lessard et al. 2011). Secondly, the study investigates whether Generation Y display relatively high levels of materialism. Materialism has also been found to have a negative correlation with aspects such as well-being (Bauer et al. 2012; Twenge, Campbell & Gentile 2011). Lastly, the study investigates the association between perceived work values and an entitlement mentality among Generation Y. Previous research has indicated that work values have an influence on vocational behaviour such as job satisfaction and commitment (Basinska & Daderman 2019). A study seeking to discover determinants of entitlement mentality can be helpful to managers as they have indicated a frustration with employees who have high work expectations but are not prepared to work hard (McAlevey & Ostertag 2014). Comparative research between men and women indicates that men have higher entitlement to salary than women (Hartman 2012; Steinþórsdóttir & Pétursdóttir 2021). Because of the previous studies, biological sex was controlled for in this study.

The present study used Lessard et al.'s (2011) dimensions of entitlement mentality: (1) exploitative entitlement, a sense of deservedness at the expense of others, and (2) nonexploitative entitlement, in which the individual feels deserving of positive outcomes without anyone getting exploited in the process. Materialism was defined by Ger and Belk (1996:291) as 'the importance an individual attaches to worldly possessions'. Hirschi (2010) defines work values as the importance one places on different job rewards and traits.

This study makes the following contributions:

-

By investigating the extent to which Generation Y have an entitlement mentality and materialistic values, this study contributes to our understanding of the work behaviours of younger workers.

-

Studies on materialism are mainly based on consumerist theories that explain how consumers respond to material things (Lučić, Uzelac & Previšić 2021). Such studies have produced interesting insights, but few have attempted to link materialism with employees' workplace behaviour. Given the above, this study goes a step further by proposing and testing a model which links materialism with entitlement mentality and work values.

Having introduced the research and having considered some of the key contributions of the study, it proceeds as follows. Firstly, literature is reviewed, and based on the literature review, hypotheses are derived. Next, research methods are considered, followed by a presentation of the results. The article concludes with a discussion and recommendations.

Literature review

Entitlement mentality

One of the earliest studies on entitlement was conducted by Sennett (1973), who posited that high levels of education were the primary source of entitlement feelings in most Americans and that the educated are more likely to feel entitled to a job. The concept was further developed by Bell (1976) in his seminal work on capitalist culture, in which entitlement was identified as the central, emerging attitude among the working population. Bell further posited that the emergence of rising expectations in civilised societies transmuted into a revolution of rising entitlement. Given that the youth in South Africa today have been exposed to education more than the generations before them, they are likely to display a higher level of entitlement.

Generation Y's characteristics

Many studies conducted on Generation Y have been in Western countries (Naim & Lenka 2018). The few studies conducted in the context of developing countries have largely examined their consumer behaviour (e.g. Duh 2015; Mafini, Dhurup & Mandlazi 2014). In South Africa, Generation Y can be divided into two groups. These two groups comprise different races who were born before and after the independence in 1994 (Martins & Martins 2012). Those born before independence may have witnessed apartheid but would have been too young to participate in the struggle and those born after independence are known as 'born free'. These two groups (black people and white people) have a lot in common, but because of the history of South Africa, their experiences of life may not necessarily be the same.

Social media has had a lot of influence on the lives of Generation Y in South Africa; therefore, this generation has more in common with their peers in the rest of the world (Martins & Martins 2012). As in most developing countries, this group has been affected by some social ills, which include high unemployment, exposure to drugs, AIDS and now COVID-19. Given the aforementioned findings, social commentators have described Generation Y in South Africa as being frustrated, disillusioned and angry (Malila & Garman 2016). Research on this South African cohort describes them as well educated and narcissistic, with high expectations of success (Martins & Martins 2012). This dichotomy of frustration and self-confidence makes studying this generation in South Africa worthwhile.

Studies conducted in the United States have found that students from Generation Y expected good grades but were not prepared to work hard to achieve these grades and that workers from this generation expected to be promoted after only 6 months (Corporate Leadership Council 2005). A study conducted by Jindal, Shaikh and Shashank (2017) then linked these unrealistic expectations to the sense of entitlement, which has been described as an 'impatience to succeed' attitude.

With regards to organisational commitment, O'Connor's (2018) study found that younger workers are unlikely to stay with one organisation for a long time. In South Africa, literature has portrayed young black professionals as job hoppers (Nzukuma & Bussin 2011). Since Generation Y will form tomorrow's leaders and managers, employers need to take note of their vocational expectations so that new ways of managing them can be developed. These new ways can be developed through an understanding of what this generation considers to be important with regards to employment. Work values provide an avenue through which such an understanding can take place.

Work values

A lot of research has focused on work values because they are seen as occupying a central position in influencing the overall behaviour of workers (Johnson & Mortimer 2011). They represent what is perceived as important in the workplace and tend to influence behaviour over time. Workplace behaviours such as job satisfaction, organisational commitment and general attitudes towards work have been found to be influenced by work values (Jin & Rounds 2012). Research has suggested that Generation Y enjoys working with others and forming friendships in the workplace. They also enjoy participating in decision-making and expect the employer to provide them with opportunities for training (Schtoth 2019).

Most studies on work values have identified two dimensions of work values: intrinsic and extrinsic work values (e.g. Gahan & Abeysekera 2009; Hirschi 2010). Lyons et al. (2006) define intrinsic work values as the innate satisfaction that one gets from working. Some researchers have noted a decrease in intrinsic values and an increase in extrinsic work values among the younger generations (Twenge 2010). Hirschi (2010) defines extrinsic work values as the importance a worker attaches to material-orientated work outcomes such as salary and advancement opportunities. Given the aforementioned definition of extrinsic work values, it can be concluded that extrinsic work values are related to materialism. Having noted that the present study also focuses on the materialism values of Generation Y and to ensure discriminant validity of the instrument used, a decision was taken to focus on intrinsic work values, represented by the following constructs taken from the Work Values Scale developed by Lyon (2003): independence, enjoyment and leisure.

Research evidence suggests that young educated workers entering the workplace for the first time have very high expectations (Walsh, Johnston & Saulnier 2015). Some findings indicate that young people do not consider work to be a central feature of their lives (Lyons & Kuron 2014) and that work-life balance is much more important to them. Unfulfilled expectations have resulted in high turnover of newly hired younger workers (Schullery 2013). Based on the literature review on work values, the following hypotheses are derived:

H1: Generation Y's need for independence is significantly associated with their exploitative entitlement mentality.

H2: Generation Y's need for independence is significantly associated with their nonexploitative entitlement mentality.

H3: Generation Y's need for leisure is significantly associated with their exploitative entitlement mentality.

H4: Generation Y's need for leisure is significantly associated with their nonentitlement mentality.

H5: Generation Y's need for enjoyment is significantly associated with their exploitative entitlement mentality.

H6: Generation Y's need for enjoyment is significantly associated with their nonexploitative entitlement mentality.

Materialistic values

Materialism is a concept that has been well researched and defined in other fields of study such as sociology and marketing (Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al. 2013). Researchers in different cultural contexts have attempted to gain an understanding of how materialistic values develop (e.g. Chen, Yao & Yan 2014). In trying to unpack the dimensions of materialism, Belk (1984) concluded that it is a personality trait comprised of three dimensions: envy, nongenerosity and possessiveness. Envy was defined by Belk as feelings of resentment towards another person's achievements. Nongenerosity was defined as 'not willing to give or share with others' (Belk 1984:268). Finally, possessiveness was defined as 'the tendency to keep control or ownership of one's possessions' (Belk 1984:291).

A meta-analytical study on materialism was conducted by Hurst et al. (2014) and found a negative correlation between materialism and well-being. Research also suggests that individuals with high materialism values are not good team players (Vohs, Mead & Goode 2006). Another common finding by some researchers is that materialistic individuals seem to be caught in an endless loop of chasing after material objects with the hope of finding happiness through them but not finding any. Materialism has therefore been viewed as a negative trait. Richins and Chaplin (2015), however, view the acquisition of material objects as a coping mechanism used by individuals with insecurity.

Materialism in South Africa

Indebtedness has been found to be very high in South Africa because of the consumptive behaviour of most people (Jacobs & Smit 2011). Government and social commentators have raised some concern about this type of behaviour. The main concern was raised by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) when it observed an increase on indebtedness as a portion of household disposable income between 1994 and 2008 (South African Reserve Bank [SARB] 2009).

Jacobs and Smit (2011) carried out a study in South Africa comparing indebtedness among low-income consumers and found that those between the ages of 25 and 34 years were more materialistic than those over 50 years. The study further found moderately high levels of materialism among South Africans, with the low-income bracket displaying relatively high levels of materialism. Given the aforementioned findings, further studies that examine the levels of materialism among the youth in South Africa are justified. Having laid out the foundation through a review of the literature on materialism, the following hypotheses are derived:

H7: Generation Y's need for material things is significantly associated with their exploitative entitlement mentality.

H8: Generation Y's need for material things is significantly associated with their nonexploitative entitlement mentality.

Quantitative research methodology

Drawing on the positivist paradigm, questionnaires were distributed among students registered with two tertiary institutions in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Sampling process

The research respondents were drawn from two institutions of higher learning in Johannesburg, South Africa. Convenience sampling was used in the study. After obtaining ethical clearance from the two institutions, e-mails were sent to lecturers seeking permission to distribute questionnaires during class. Research assistants then distributed hard copies in those classes where lecturers had responded positively towards the study. Respondents were required to fill in consent forms before filling in the questionnaire. One of the institutions was a public university with a total number of 37 448 students, and the other was a private institution with a total population of 8750 students. The study was conducted on a sample of students between the ages of 18 and 32 years. This was considered to be appropriate based on previous studies giving birth years for Generation Y to be between 1982 and 1999 (Smola & Sutton 2002). Raosoft's (2004) sample size calculator was used to calculate the minimum sample size, and 519 responses were received from the two institutions (315 respondents from the university and 204 respondents from the private college).

Research instruments

Based on the variables identified for the study (materialism, an entitlement mentality and work values), various instruments were adapted with item pools of up to 10 statements for each construct. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree or strongly disagree; not important at all or very much important) was then developed and pretested among 50 students in the two institutions. Based on factor analyses and other measures of internal consistency, some items were dropped, and a minimum of 5 to a maximum of 10 items remained for each construct.

Perceived work values

Work values were measured using the adapted Work Value Survey Scale developed by Lyons (2003), which addressed two key dimensions of work values: intrinsic work values and extrinsic work values. Because of the relationship between items in the extrinsic work value scale and the items in the materialism scale, it was decided that only intrinsic work values (independence, leisure and enjoyment) would be measured in this study. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale, respondents were asked to rate the importance of nine items relating aspects of work that they consider to be important when making job choice decisions, from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very much important).

Materialistic values

The five items measuring materialism were taken from Twenge and Kessler's (2013) materialism scale. For this scale, respondents were asked to rate the importance of material possessions, for example, 'having many cars', on a 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very much important) scale.

Entitlement mentality scale

The 12 items used to measure entitlement in this scale were taken from Lessard et al. (2011). The scale has two subscales that assess two variants of entitlement. The first subscale is the five-item nonexploitive entitlement subscale, which assesses entitlement that does not infringe on the rights of others, and the exploitative entitlement subscale, which assesses beliefs of entitlement at the expense of others. For this scale respondents were asked to respond using a 5-point Likert-type scale, 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Ethical considerations

The study proposal was submitted to the Central Ethical Committee of the University as well as the private college so that the study would meet all ethical considerations. Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: H15/09/28). The participants who met the inclusive criteria were invited to participate in the study. In this process, an information sheet explaining the introduction and purpose of the study was given to each respondent and participants were asked to fill in consent forms before they could participate. The participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality of the study.

Results

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 was used in the descriptive analysis of this study. Structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Amos version 25. Structural equation modelling is a robust statistical analysis tool for testing a theoretical model in order to explain as much of its statistical variance as possible. Below is a presentation of the descriptive analysis which includes the demographic results of the respondents and central tendency measures. After the descriptive analysis, there will be a discussion of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity and the structural model analysis.

Demographic information

This section presents the demographic profile of the respondents, which includes biological sex and age. The sample of this study was made up of 519 tertiary students from two institutions of higher learning in South Africa. The results suggest that more women participated in the study than men (52.8%), and a few respondents did not specify their biological sex (0.8%).

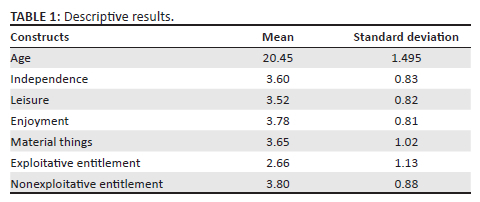

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the study, and the average age of most of the respondents was about 20 years old (20, 45).

Independent t-test results on biological sex

Biological sex was controlled for in the study. However, independent t-tests were carried out to compare means between men and women on materialism, work values and entitlement scales. Interesting results were observed which suggested that men are more materialistic than women and that women have higher intrinsic work values than men. These are indeed interesting results which warrant further studies focusing on these differences. However, no significant differences were found between men and women on entitlement mentality.

Central tendency measures

The study utilised central tendency measures to analyse the constructs involved in the study. A 5-point Likert scale, where the value 1 represents 'Strongly disagree' or 'Not at all important' and the value 5 represents 'Strongly agree' or 'Very much important', was used to measure the variables, namely independence, leisure, enjoyment, material things, exploitative entitlement and nonexploitative entitlement. Considering that the highest score on a 5-point Likert scale is 5, then 2.5 (5/2) would be the midpoint of the scale. In interpreting the mean scores, values below 2.5 were interpreted to mean that respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statements made about the construct. Scores of between 2.5 and 3.4 were interpreted to mean that respondents were neutral about the statements under consideration. However, if the mean scores were equal or above 3.5, this was interpreted to mean that respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the statements under consideration.

Results seen in Table 1 indicate that most of the respondents in the study had a high level of materialism (means score 3.65), work values (independence 3.7, leisure 3.5 and enjoyment 3.7) and high levels of nonexploitative entitlement mentality mean score (3.8). However, the mean score for exploitative entitlement was 2.6, suggesting that the respondents were neutral on this variable.

Normality assessment

Normality tests were conducted to confirm whether parametric tests could be used to test the model. The threshold values for skewness and kurtosis should be below ±3 and ±10, respectively (Kline 2011). The skewness and kurtosis values in the present study fall within Kline's (2011) recommended range; therefore, the assumption of univariate normality was met.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The first step in SEM is to conduct CFA to deal specifically with measurement models, that is, to verify the measurement quality of all latent constructs being used in SEM (Brown 2015).

Goodness of fit and validity of the measurement model

The final measurement model was drawn from SPSS Amos version 25. The model yielded a chi-square value of 617.924, degree of freedom (df) of 329 and p-value of 0.000. However, because of the sensitivity of the chi-square to the sample size, Hair et al. (2014) recommend to further examine the model fit indices. Results indicate a good model fit as discrepancy divided by degree of freedom (CMIN/df) = 1.878, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.968, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.972, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.922, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.942 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.041. The model fit indices were all within Hair et al.'s (2014) threshold.

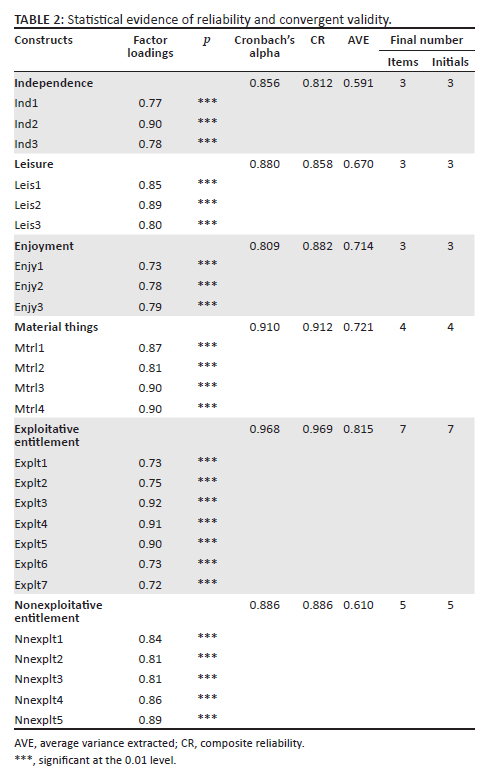

The measurement model had seven latent variables (or constructs), namely independence, leisure, enjoyment, material things, exploitative entitlement and nonexploitative entitlement. Factor loadings indicate the contribution of each item to its construct. All the factor loadings in the measurement model were good as they were all above 0.6 (Malhotra, Nunan & Birks 2017).

Reliability

Reliability is the ability of an instrument or measure to produce consistent results when the same constructs are measured under different conditions (Taherdoost 2016). Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (CR) are generally used to measure reliability. The results in Table 2 show that the Cronbach's alpha ranges from 0.778 to 0.968, thus suggesting a good level of internal consistency across all six variables in the model. This result is further supported by CR coefficients, which ranged from 0.785 to 0.969. Based on these results, all constructs involved in this study are considered reliable.

Convergent validity

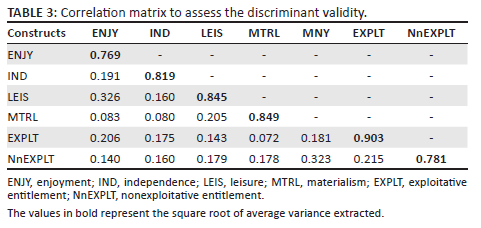

Convergent validity is 'the extent to which a set of items only measure one latent variable' (Hosany et al. 2015). The results in Table 2 suggest that there is convergent and discriminant validity because all the factor loadings are above 0.6, and there is a moderate level of correlations (less than 0.8) between the constructs. In addition, further advanced statistics may be required to check the validity of all the constructs used in this study. Average variance extracted (AVE) was calculated to check the convergent validity of the items in the scale (see Table 2). The results show that AVE of all constructs exceeded the standard of 0.5 (Malhotra et al. 2017). These results support the convergent validity evidence provided by the factor loadings in Table 3.

Table 2 indicates that there is reliability and convergent validity of the items retained in the final measurement model. All items retained in the final measurement model were considered to be good measures of what they set out to measure.

Statistical evidence of discriminant validity

Discriminant validity is the extent to which a latent variable or construct is not related to other latent variables (Taherdoost 2016). The expectation is that the square root of the AVE will be above the interconstruct correlation coefficients. Malhotra et al. (2017) suggest that discriminant validity be assessed through a comparison of correlations between pairs of constructs with the square root of AVE of each construct. Poor discriminant validity between the constructs is indicated by correlations greater than the square root of AVE. For instance, 0.769 (square root of 'enjoyment') is greater than 0.326, which is the correlation coefficient between 'enjoyment' and 'leisure'. The results in the Table 3 indicate that all the correlations were smaller than the squared root of AVEs on the diagonals, implying satisfactory discriminant validity.

All the findings of this section confirm an adequate reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity of the constructs and items in this study.

Structural model analysis

The model was tested using the maximum likelihood computed on Amos 25. The purpose of the structural model is to test the proposed hypotheses. The results indicate that the structural model satisfactorily fits the data as CMIN/df = 2.112, TLI = 0.959, CFI = 0.963, GFI = 0.908, NFI = 0.933 and RMSEA = 0.046. However, the regression weights in the model are very weak, and some paths in the model are nonsignificant. Figure 1 presents the graphical representation of the structural model.

The standardised regression weights indicate the strength of the relationship between the variables (Hair et al. 2014). Table 4 presents the standardised regression estimates and examines the significance of the direct association between the constructs.

Findings and discussion

One of the main research questions of the study was whether Generation Y in South Africa had relatively high levels of entitlement mentality as well as high levels of materialism. The study further sought to examine the potential influence of work values and materialism on entitlement mentality using SEM.

The descriptive findings from this study suggest that Generation Y in South Africa have a high sense of entitlement mentality, as seen in Table 1, with most mean scores of both exploitative and nonexploitative entitlement above the 2.5 threshold. As suggested by Lessard et al. (2011), both the exploitive and nonexploitive measures are actually measuring one construct (i.e. entitlement), and therefore although the mean score for exploitative entitlement mentality was in the neutral range, it cannot be said to be low. Table 1 also suggests that Generation Y in South Africa have high materialism values, with a mean score of 3.65. These results on materialism echo the findings of studies on Generation Y that have been conducted in South Africa (e.g. De Klerk 2020; Duh 2015). Such materialistic values may be linked to the influence of social media celebrities who have become an important source of influence among the youth. Some negative traits have been associated with materialistic individuals, namely envy, nongenerosity and possessiveness (Belk 1984). With studies conducted in South Africa showing Generation Y to be materialistic, managers who develop compensatory schemes that prioritise material rewards in this context need to pay particular attention to the potential for negative work outcomes associated with such schemes. The results of the present study indicated that Generation Y in South Africa have high levels of nonexploitative entitlement mentality. Given that this type of entitlement mentality is not based on the exploitation of others, one can conclude that it is not a negative trait.

Eight hypotheses relating work values and materialism to entitlement mentality were tested in the model. Of the three dimensions of work values, independence and enjoyment were significantly related to the exploitative variant of entitlement mentality. Independence, leisure and materialism were also found to be significantly related to nonexploitative entitlement mentality. These are very interesting results. On the basis of the aforementioned results, one could assume that people with high levels of entitlement mentality have a high sense of independence and want both leisure and enjoyment in the workplace. Wüst and Leko-Šimić (2017) conducted a study in Germany which also identified the need for independence and leisure among the youth. The results of the present study regarding work values may actually be reflecting Generation Y's need for work-life balance. The topic of work-life balance is of contemporary interest for those who believe in the quality of working life. Research has found that Generation Y pay greater attention to maintaining a work-life balance (Maxwell & Broadbridge 2017; Twenge & Kasser 2013) than other generations. The construct of independence has also been linked to entrepreneurship, which has often been associated with Generation Y (Struckell 2018). Managers can therefore tap into this entrepreneurial orientation of Generation Y by involving them in projects that allow them some independence. Policymakers might also assist the entrepreneurial by creating conditions where the youth can start their own businesses rather than rely on formal employment. However, COVID-19 has brought additional pressures to the workplace, with no one guaranteed a job during such times. Factors related to advances in technology and the need for speedy responses now all point towards a pressurised work environment. Of concern to managers would be whether these young workers would still be able to enjoy themselves under such conditions and what would happen should they not enjoy themselves. Furthermore, prospective workers who bring an entitlement mentality into their future workplace are likely to pose problems for their managers. These problems may manifest themselves in counterproductive behaviours such as demand for higher pay without corresponding hard work (Fisk 2010).

On the relationship between materialism and entitlement mentality, the results of the present study suggest that entitlement mentality is related to materialism but that the relationship depends on the variant of entitlement mentality. Interestingly, nonexploitative entitlement mentality was found to be related to materialism. The expectation, however, had been that exploitative entitlement mentality would likely be related to materialism more than nonexploitative entitlement. These results may warrant further investigation on the relationship between these constructs.

Conclusion and recommendations

Many corporate scandals have been reported locally and elsewhere (e.g. Enron, KPMG, McKinsey and the Venda Building Society), and these have been linked with materialism and a high sense of entitlement. Studies have suggested that there is greater possibility for materialistic individuals to engage in unethical behaviour to obtain the material possessions they so desire (Ozgen, Demirci & Taş 2006). Furthermore, research has linked entitlement mentality with narcissism, which is found in individuals who have a bloated ego and often believe that they can attain wealth without necessarily having to work hard for it (Jindal, Shaikh & Shashank 2017). Given the negative outcomes associated with an entitlement mentality and materialism, further studies need to be conducted on the interaction between these constructs.

The student protests that have been recurrent in South Africa since 2016 under #FeesMustFall could be viewed as a manifestation of an entitlement mentality. With so much youth unemployment in South Africa, standing at 60% (SSA 2013) sooner rather than later, these youths might demand employment. The inability of government to satisfy these needs produces pressures which contribute to civil unrest. Although it might be argued that the violence that swept through certain provinces of South Africa (namely KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng) in the week of 12 July 2021 was not necessarily involving the youth only, the results will have a long-lasting impact on the social and political fabric of South Africans (Ahmed et al. 2021). Such events tend to create long-lasting value systems which shape the behaviour of the cohorts that witness them (Smola & Sutton 2002). June is an important month in the history of South Africa, and the 16th of June is a public holiday which celebrates the 1976 youths' protests. On Youth Day in 2022, 'hundreds of young people marched to the Unions Buildings to hand over a memorandum that voices a series of concerns faced by South African youth' and one of their main concerns was lack of jobs for the youth in South Africa (Nqunjana 2022).

South Africa is the most unequal country in the world, with a Gini coefficient standing at 0.63 (World Bank 2014). With such inequalities, protests such as were seen in 2021 are more likely to happen. Currently, another protest movement led by a youthful individual, targeting illegal immigrants, is underway under what is termed 'Operation Dudula'. Dudula is a Zulu word for 'push'. These protests seem to resonate with certain opposition parties that have used illegal foreigners as a campaign tool with some measure of success in getting votes in recent local government elections. Some people believe that the votes lost to opposition parties in the recent local government elections have paralysed government in dealing with these protests. Unfortunately, such protests are notorious for getting out of hand if not controlled. It is therefore important that political leaders become more responsive to the needs of the youth; otherwise, the scenes of civil unrest recently seen across South Africa might become more common.

Limitations of the study

The following limitations should be noted when interpreting the findings of this study. The first limitation relates to the fact that data were gathered in only two institutions of higher learning in South Africa, using a nonprobability sampling technique. As a result, although trends can be observed, generalisations to the larger population may not be possible using these results. A national study might yield more generalisable results. The second limitation relates to lack of comparison with other generations. It is possible that the same findings could be made in other generations as well.

A third limitation relates to the use of SEM. This offered the advantage of simultaneous testing of the key relationships identified by theory and previous research. Further studies using the qualitative approach might explain the causes that underlie these results. The main limitation of SEM and similar tools is their inability to test causality. Further research that uses experimental methods might build on the work here to empirically test these relationships.

Overall, despite these limitations, this study offers useful findings that demonstrate the importance of understanding entitlement mentality and its associated determinates. It is hoped that this stream of research ultimately makes a difference in the ongoing efforts to address workplace attitudes that may be termed counterproductive.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank and acknowledge Prof. Chris W. Callaghan who contributed through supervising the study and writing up the work as part of the author's degree submission.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

E.N. is the sole author for this article.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data were obtained from respondents after ethics clearance was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand. As part of ethical undertaking, the data cannot identify individuals and are used in aggregated form here as per ethics requirements. The data are confidential, and information is only provided in the article at the aggregate level where respondents cannot be identified.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Ahmed, R., Mohamed, Y.S., Nell, J., Somhlaba, N.Z. & Karriem A., 2021, 'Poverty, protests and pandemics: What can we learn from community resilience?', South African Journal of Psychology 51(4), 478-480. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463211047669 [ Links ]

Basinska, B.A. & Daderman, A.M., 2019, 'Work values of police officers and their relationship with job burnout and work engagement', Frontiers in Psychology 10, 442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00442 [ Links ]

Bauer, M.A., Wilkie, J.E., Kim, J.K. & Bodenhausen, G.V., 2012, 'Cuing consumerism: Situational materialism undermines personal and social well-being', Psychological Science 23(5), 517-523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429579 [ Links ]

Belk, R.W., 1984, 'Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness', in T. Kinnear (ed.), Advances consumer research, vol. 11, pp. 291-297, Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT. [ Links ]

Bell, D., 1976, The cultural contradictions of capitalism, Basic Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Bloom, C., 2012a, Protest and rebellion in the capital, Palgrave Macmillan, Riot City. [ Links ]

Bloom, D., 2012b, 'Youth in the balance', Finance & Development 49(1), 7-11. [ Links ]

Brown, T.A., 2015, Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd edn., The Guilford Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Calitz, E. & Fourie, J., 2016, 'The historically high cost of tertiary education in South Africa', Politikon 43(1), 149-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2016.1155790 [ Links ]

Campbell, W.K., Bonacci, A.M., Shelton, J., Exline, J.J. & Bushman, B.J., 2004, 'Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure', Journal of Personality Assessment 83(1), 29-45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8301_04 [ Links ]

Chen, Y., Yao, M. & Yan, W., 2014, 'Materialism and well-being among Chinese college students: The mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction', Journal of Health Psychology 19(10), 1232-1240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313488973 [ Links ]

Corporate Leadership Council, 2005, HR considerations for engaging Generation Y employees, Corporate Executive Board, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Davis, C.J., 1969, 'The J-curve of rising and declining satisfactions as a cause of some great revolutions and a contained rebellion', in H.D. Graham & I.R. Gore (eds.), The history of violence in America: Historical and comparative perspectives, pp. 690-730, Praeger, New York, NY. [ Links ]

De Klerk, N., 2020, 'Influence of status consumption, materialism and subjective norms on Generation Y students 'price-quality fashion attitude', International Journal of Business and Management Studies 12(1), 163-176. [ Links ]

Derber, C., 1978, 'Unemployment and the entitled worker: Job-entitlement and radical political attitudes among the youthful unemployed', Social Problems 26(1), 2637. https://doi.org/10.2307/800430 [ Links ]

Duh, H.I., 2015, 'Antecedents and consequences of materialism: An integrated theoretical framework', Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies 7(1), 20-35. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v7i1(J).560 [ Links ]

Fisk, G.M., 2010, '"I want it all and I want it now!" An examination of the etiology, expression, and escalation of excessive employee entitlement', Human Resource Management Review 20(2), 102-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.11.001 [ Links ]

Gahan, P. & Abeysekera, L., 2009, 'What shapes an individual's work values? An integrated model of the relationship between work values, national culture and self-construal', International Journal of Human Resource Management 20(1), 126-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802528524 [ Links ]

Ger, G. & Belk, R.W., 1996, 'Cross-cultural differences in materialism', Journal Of Economic Psychology 17(1), 55-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(95)00035-6 [ Links ]

Grow, J.M. & Yang, S., 2018, 'Generation-Z enters the advertising workplace: Expectations through a gendered lens', Journal of Advertising Education 22(1), 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098048218768595 [ Links ]

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. & Anderson, R.E., 2014, Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Hartman, T.B., 2012, 'An analysis of university student academic self-entitlement: Levels of entitlement, academic year, and gender', Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI. [ Links ]

Hirschi, A., 2010a, 'Positive adolescent career development: The role of intrinsic and extrinsic work values', The Career Development Quarterly 58(3), 276-287. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2010.tb00193.x [ Links ]

Hosany, S., Prayag, G., Deesilatham, S., Causevic, S. & Odeh, K., 2015, 'Measuring tourists' emotional experiences: Further validation of the destination emotion scale', Journal of Travel Research 54(4), 482-495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522878 [ Links ]

Hoxha, V. & Zeqiraj, E., 2019, 'The impact of Generation Z in the intention to purchase real estate in Kosovo', Property Management 38(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-12-2018-0060 [ Links ]

Hurst, M., Dittmar, H., Bond, R. & Kasser, T., 2014, 'The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviours: A meta-analysis', Journal of Environmental Psychology 36, 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.09.003 [ Links ]

Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), 2016, Integrated report for the year ended 31 March 2016, viewed 10 May 2021, from http://www.idc.co.za/ir2014/images/pdf/ar2014.pdf. [ Links ]

Jacobs, G. & Smit, E., 2011, 'Materialism and indebtedness of low income consumers: Evidence from South Africa's largest credit granting catalogue retailer', South African Journal of Business Management 41(4), 11-32. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v41i4.527 [ Links ]

Jin, J. & Rounds, J., 2012, 'Stability and change in work values: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies', Journal of Vocational Behaviour 80(2), 326-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.007 [ Links ]

Jindal, P., Shaikh, M. & Shashank, G., 2017, 'Employee engagement - Tool of talent retention: Study of a pharmaceutical company', SDMIMD Journal of Management 8(2), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.18311/sdmimd/2017/18024 [ Links ]

Johnson, M.K. & Mortimer, J.T., 2011, 'Origins and outcomes of judgments about work', Social Forces 89(4), 1239-1260. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/89.4.1239 [ Links ]

Kasser, T., 2010, 'Materialism and its alternatives', in A.M. Zawadzka & M. Górnik Durose (eds.), ĩycie w konsumpcji-konsumpcja w Īyciu. Psychologiczne ścieĪki współzaleĪności [Life in consumption, consumption in life. Psychological interdependencies], pp. 127-141, GWP, Gdansk. [ Links ]

Kilber, J., Barclay, A. & Ohmer, D., 2014, 'Seven tips for managing Generation Y', Journal of Management Policy and Practice 15(4), 80-91. [ Links ]

Kline, R.B., 2011, Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, Guilford Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Lazanyi, K. & Bilan, Y., 2017, 'Generetion Z on the labourmarket - Do they trust others within their workplace?', Polish Journal of Management Studies 16(1), 78-93. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2017.16.1.07 [ Links ]

Lessard, J., Greenberger, E., Chen, C. & Farruggia, S., 2011, 'Are youth feelings of entitlement always "bad"? Evidence for a distinction between exploitive and non-exploitive dimensions of entitlement', Journal of Adolescence 34(3), 521-529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.014 [ Links ]

Lučić, A., Uzelac, M. & Previšić, A., 2021, 'The power of materialism among young adults: Exploring the effects of values on impulsiveness and responsible financial behavior', Young Consumers 22(2), 254-271. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-09-2020-1213 [ Links ]

Lyons, S., 2003, 'An exploration of generational values in life and at work', Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Carleton University, Ottawa. [ Links ]

Lyons, S.T., Duxbury, L.E. & Higgins, C.A., 2006, 'A comparison of the values and commitment of private sector, public-sector, and para-public-sector employees', Public Administration Review 66(4), 605-618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00620.x [ Links ]

Lyons, S. & Kuron, L., 2014, 'Generational differences in the workplace: A review of the evidence and directions for future research', Journal of Organizational Behavior 35(S1), 139-157. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1913 [ Links ]

Mafini, C., Dhurup, M. & Mandlazi, L., 2014, 'Shopper typologies amongst a Generation Y consumer cohort and variations in terms of age in the fashion apparel market', Acta Commercii 14(1), a209. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v14i1.209 [ Links ]

Malhotra, K.N., Nunan, D. & Birks, F.D., 2017, Marketing research: An applied approach, Pearson Education Limited, Harlow. [ Links ]

Malila, V. & Garman, A., 2016, 'Listening to the "born frees": Politics and disillusionment in South Africa', African Journalism Studies 37(1), 64-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2015.1084587 [ Links ]

Martins, N. & Martins, E., 2012, 'Assessing Millennials in the South African work context', in E. Ng, S.T. Lyons & L. Schweitzer (eds.), Managing the new workforce: International perspectives on the Millennial Generation, pp. 152-180, Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton. [ Links ]

Maxwell, G.A. & Broadbridge A.M., 2017, 'Generation Y's employment expectations: UK undergraduates' opinions on enjoyment, opportunity and progression', Studies in Higher Education 42(12), 2267-2283. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1141403 [ Links ]

McAlevey, J. & Ostertag, B., 2014, Raising expectations (and raising hell): My decade fighting for the labor movement, Reprint edn., Verso, London. [ Links ]

Naim, M.F. & Lenka, U., 2018, 'Development and retention of Generation Y employees: A conceptual framework', Employee Relations 40(2), 433e455. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2016-0172 [ Links ]

Nkomo, E., 2017, 'Exploring the determinants of entitlement mentality among Generation Y in two tertiary institutions in Johannesburg, South Africa', PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Nqunjana, A., 2022, '"This is the beginning of a revolution": Scores of young people march to Union Buildings', News 24, viewed 19 June 2022, from https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/watch-this-is-the-beginning-of-a-revolution-scores-of-young-people-march-to-union-buildings-20220618. [ Links ]

Nzukuma, K.C.C. & Bussin, M., 2011, 'Job-hopping amongst African black senior management in South Africa', South African Journal of Human Resource Management 9(1), 258-269. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v9i1.360 [ Links ]

O'Connor, J., 2018, 'The impact of job satisfaction on the turnover intent of executive level central office administrators in Texas public school districts: A quantitative study of work related constructs', Education Sciences 8, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020069 [ Links ]

Ozgen, O., Demirci, A. & Taş, A.S., 2006, 'Media, materialism and socialization of child consumers', in 8th international conference on education, ATINER Publication, Athens, Greece, May 25-28, 2006, pp. 319-321. [ Links ]

Pechurina, A., 2020, 'Researching identities through material possessions: The case of diasporic objects', Current Sociology 68(5), 669-683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120927746 [ Links ]

Raosoft, 2004, Sample size calculator, viewed from http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html. [ Links ]

Richins, M.L. & Chaplin, L.N., 2015, 'Material parenting: How the use of goods in parenting fosters materialism in the next generation', Journal of Consumer Research 41(6), 1333-1357. https://doi.org/10.1086/680087 [ Links ]

Schullery, N.M., 2013, 'Workplace engagement and generational differences in values', Business Communication Quarterly 76(2), 252-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569913476543 [ Links ]

Sennett, R., 1973, The hidden injuries of class, Vintage, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Smola, K.W. & Sutton, C.D., 2002, 'Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium', Journal of Organizational Behaviour 23(4), 363-382. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.147 [ Links ]

South African Reserve Bank (SARB), 2009, Quarterly bulletin, Online Statistical Queries, South African Reserve Bank. Accessesd June 2019, from http://www.reservebank.co.za/ [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa, 2013, Labour market statistics, South African Government, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Steinþórsdóttir, F.S. & Pétursdóttir, G.M., 2021, 'To protect and serve while protecting privileges and serving male interests: Hegemonic masculinity and the sense of entitlement within the Icelandic police force', Policing and Society 32(4), 489-503. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2021.1922407 [ Links ]

Struckell, E., 2018, 'Millennials: A generation of un-entrepreneurs', USASBE conference, 2019, St. Petersburg, FL. [ Links ]

Struckell, E.M., 2019, 'Millennials: A generation of un-entrepreneurs', Journal of Business Diversity 19(2), 156-168. [ Links ]

Taherdoost, H., 2016, 'Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research', International Journal of Academic Research in Management 5(3), 28-36. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3205040 [ Links ]

The World Bank, 2014, GINI index (World Bank estimate), viewed 12 March 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=ZA&most_recenvaluedesc=true. [ Links ]

Twenge, J.M., 2010, 'A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes', Journal of Business and Psychology 25(2), 201-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9165-6 [ Links ]

Twenge, J.M., Campbell, W.K. & Gentile, B., 2011, 'Generational increases in agentic self evaluations among American college students, 1966-2009', Self and Identity 11(4), 409-427. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.576820 [ Links ]

Twenge, J.M. & Kasser, T., 2013, 'Generational changes in materialism and work centrality, 1976-2007: Associations with temporal changes in societal insecurity and materialistic role modeling', Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39(7), 883-897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213484586 [ Links ]

Vohs, K.D., Mead, N.L. & Goode, M.R., 2006, 'The psychological consequences of money', Science 314(5802), 1154-1156. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132491 [ Links ]

Walsh, D., Johnston, M. & Saulnier, C., 2015, Great expectations: Opportunities and challenges for young workers in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Halifax. [ Links ]

Wüst, K. & Leko-Šimić, M., 2017, 'Students' career preferences: Intercultural study of Croatian and German students', Economics & Sociology 10(3), 136-152. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-3/10 [ Links ]

Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Baran, T., Clinton, A., Piotrowski, J., Baltatescu, S. & Van Hiel, A., 2013, 'Materialism, subjective well-being, and entitlement', Journal of Social Research and Policy 4(2), 79-91. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Emmanuel Nkomo

emmanuel.nkomo@wits.ac.za

Received: 27 Mar. 2022

Accepted: 29 June 2022

Published: 23 Sept. 2022