Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Commercii

versión On-line ISSN 1684-1999

versión impresa ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.21 no.1 Johannesburg 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v21i1.903

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Investigating the direct costs of business rescue

Nicole V.A. de Abreu; Wesley Rosslyn-Smith

Department of Business Management, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: The direct costs associated with business rescue proceedings are essential to the decision-making of directors, business rescue practitioners and other affected parties. Business rescue has come under criticism for being a costly procedure, but what constitutes these costs and how they are defined remain largely unknown

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The aim of this study was to identify and measure the direct costs of business rescue proceedings in South Africa. This research also explored the relationship between direct costs and the following variables: firm size and duration of business rescue proceedings

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Despite the significance of understanding reorganisation costs, astonishingly little is know about the size and determinants of the direct costs of business rescue in the South African context. Business rescue practitioners fees and other related expenses have been blamed for worsening business rescue proceedings' reputation. However, researchers have not yet determined the nature or quantum of such costs.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: This study employed an exploratory sequential mixed-method research design. The first phase comprised semi-structured interviews supplemented by a closed card sort with 14 business rescue practitioners. The first phase resulted in direct cost categories and components used to develop a survey instrument. The survey was administered in the second phase and measured the direct costs for 19 South African firms previously under business rescue.

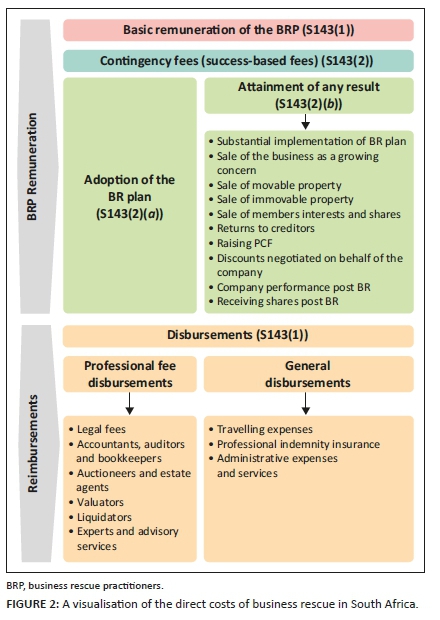

MAIN FINDINGS: The first phase results show that the direct costs of business rescue consist of four categories: the basic remuneration of the business rescue practitioner, contingency fees, professional fee disbursements and general disbursements. Because of the small sample size, the results of the second phase were inconclusive

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: This research contributes to the management body of knowledge by providing business rescue practitioners, the management of distressed companies, and affected parties, especially creditors with a starting point into understanding the direct costs of business rescue proceedings.

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: This is the first study of its kind, to quantitatively measure the direct costs of business rescue in the South African context. Therefore, the results of the study may offer affected parties some insight and clarity regarding the nature of the direct costs of business rescue.

Keywords: financial distress; insolvency; reorganisation; business rescue; reorganisation costs; direct costs.

Introduction

'Measurement is the first step that leads to control and eventually to improvement. If you can't measure something, you can't understand it. If you can't understand it, you can't control it. If you can't control it, you can't improve it'. - H. James Harrington

A vital aspect of any formal turnaround procedure is the costs it imposes on an already financially distressed firm. For the commencement decision, it becomes a vital variable that stakeholders must consider. Whilst proceedings will inevitably generate costs, these costs are most likely to vary between jurisdictions. Our understanding of reorganisation costs, both direct and indirect, is of paramount importance to decision-makers (Armour, Hsu & Walters 2012:109). Our study takes a closer look at the direct costs of the business rescue process to better understand them and their impact on a distressed firm.

Direct costs are defined as transaction costs or out-of-pocket expenses directly related to administering reorganisation proceedings. Direct costs include administrative costs, such as filing fees, paid to business consultants, lawyers, turnaround specialists, accountants and other professionals (Altman & Hotchkiss 2006:93; Armour et al. 2012:109; Bhabra & Yao 2011:43). Studies conducted across several jurisdictions, including the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom show a significant variation in the direct costs of reorganisation with mixed conclusions on the size of direct costs (Bris, Welch & Zhu 2006:1254; Citron & Wright 2008:71; Fisher & Martel 2005:157; Gine & Love 2010:3). As South Africa's business rescue environment varies significantly from these jurisdictions, these studies' findings are difficult to generalise for a South African context.

To evaluate the effectiveness of reorganisation proceedings, it is essential to understand the costs associated with reorganisation proceedings (Citron & Wright 2008:71; Ferris & Lawless 2000:629). Despite the significance of understanding reorganisation costs, astonishingly little is known about the size and determinants of the direct costs of business rescue in the South African context. Business rescue has come under criticism for being a costly process with a low success rate - only 16.74% in March 2018 (Companies and Intellectual Property Commission 2018:3; Le Roux & Duncan 2013:63; Loubser 2013:514; Pretorius 2015:37). According to Bradstreet, Pretorius and Mindlin (2015:16), business rescue practitioners' (BRPs) fees and other related business rescue expenses have been blamed for worsening business rescue proceedings' reputation. However, researchers have not yet determined the nature or quantum of such costs.

An exploratory sequential mixed-method design was used to explore the direct costs of business rescue proceedings in South Africa. The first phase entailed a generic qualitative exploration to identify the direct costs of business rescue and the components of the direct costs. During the first phase, qualitative data were collected from BRPs. Thereafter, the qualitative findings were used to develop a survey instrument administered to a sample of BRPs to measure the direct cost components of business rescue proceedings for firms previously under business rescue in South Africa. Additionally, the study examined the relationship between the direct costs of business rescue and the following variables: firm size and duration of business rescue proceedings.

This study's main objective was to identify the direct costs of business rescue proceedings in South Africa. In relation to the above, this study sought to achieve the following subobjectives:

-

To measure the direct costs of business rescue proceedings for firms previously under business rescue in South Africa.

-

To investigate the relationship between the direct costs of business rescue and the size of the firm.

-

To investigate the relationship between the direct costs of business rescue and the duration of business rescue proceedings.

The study's findings may be of interest for several reasons. Firstly, by identifying and describing direct costs, the results may offer affected parties some insight and clarity regarding the nature of direct costs. Additionally, these findings may initiate further exploration into the topic. If business rescue costs are as high as claimed to be, these costs could be a key factor contributing to the low success rate of business rescue in South Africa. As a result, understanding the size and determinants of business rescue costs is necessary before the legislator and regulator can discuss ways to reduce these costs (Betker 1997:57). On the contrary, if direct business rescue costs are insignificant, it could be concluded that the prospects for a successful reorganisation may be a function of various firm characteristics (Campbell 1997:22).

Theoretical background

Financially distressed firms are often faced with the decision to enter reorganisation proceedings or liquidate. When faced with this decision, the objective should be to choose an option that is most effective and maximises the overall value for affected parties (Gilson 2012:25). This is a critical decision because of the inherent costs accompanying each choice. If a firm chooses to reorganise when it is not economically viable and should be liquidated, resources are squandered as the firm attempts to engage unsuccessfully in reorganisation (Adams 1993:598).

As insolvency costs play a significant role in a firm's choice between liquidation and reorganisation, it is essential to understand the size of these costs (Fisher & Martel 2005:151; White 1989:146). Insolvency costs are divided into direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are defined as the transaction costs or out-of-pocket expenses directly related to administering proceedings. These costs include administrative expenses, such as filing expenses and fees paid to business consultants, lawyers, turnaround specialists, accountants and other professionals (Altman & Hotchkiss 2006:93; Armour et al. 2012:109; Bhabra & Yao 2011:43). In contrast, indirect costs are defined as lost profits or opportunities resulting from a loss of customer and supplier goodwill, a loss of key employees and management, a decrease in employee morale and productivity, inefficient asset sales and the inability to raise finance (Altman 1984:1071; Andrade & Kaplan 1998:1445; Bhabra & Yao 2011:45; Chen & Merville 1999:277; Pulvino 1998:940).

Direct costs of reorganisation

The direct costs of administering reorganisation proceedings mainly comprise fees paid to different professionals (Branch 2002:43; Citron & Wright 2008:76). According to Branch (2002:42), financially distressed firms typically employ third-party professionals, specifically accountants, turnaround specialists, lawyers and other professionals who charge significant hourly rates. A 'practitioner in possession' regime is used in the United Kingdom and South Africa, whereby an administrator (practitioner) is appointed to manage reorganisation proceedings (Pretorius & Rosslyn-Smith 2014:116). In addition to managing reorganisation proceedings, the practitioner must participate in several types of accountability-related actions, such as preparing and circulating reports to creditors and calling and conducting creditors' meetings (Armour et al. 2012:111). Several administrative tasks fall to the practitioner, such as assembling a list of creditors and determining whether creditor claims are legitimate (Fisher & Martel 2005:159). All these tasks may result in increased costs of reorganisation. Armour et al. (2012:111) report a real process cost involved with preparing a paper trail to guard against legal liability and conducting creditors' meetings. These costs usually include the practitioner's fee, legal costs associated with proceedings and miscellaneous expenses, such as telephone bills and photocopying (Fisher & Martel 2005:159).

Various studies, commonly based on samples of firms from the United States, have investigated the direct costs associated with reorganisation procedures. As a control for firm size, the results are typically reported as a ratio of total firm value. Possible measures for firm value include the market value of pre-bankruptcy assets, either at book or at estimated market value, and post-bankruptcy assets (Armour et al. 2012:109). The studies' results offer mixed findings, as the studies cover a wide variety of firms, and there is significant variation in sample sizes (Betker 1997; Bris et al. 2006:1254; Fisher & Martel 2005:157). The range of estimated costs is quite broad, as means range from 1% to about 10% of the firms' size (Altman 1984; Bris et al. 2006; LoPucki & Doherty 2004; Lubben 2000; Tashjian, Lease & McConnell 1996).

Determinants of direct costs

According to Campbell (1997:27) and LoPucki and Doherty (2004:113), firm size is an important determinant of direct costs. The greater the value of assets at stake and the larger the number of creditors, the greater the effort required in reorganisation proceedings, as more problems are likely to occur (Armour et al. 2012:110; LoPucki & Doherty 2008:989). Conflicts of interest between creditors may arise in reorganisation cases with numerous creditors. The presence of numerous creditors may increase information costs, as there may be difficulties in reaching consensus amongst multiple parties. If different creditors have conflicting objectives, the variety of pressures on the practitioner and the coordination problems may increase the costs of reorganising the firm (Altman & Hotchkiss 2006:102; Citron & Wright 2008:74). Therefore, as the level of complexity increases, distressed firms usually hire an increased number of professionals with specific skill sets, resulting in increased reorganisation costs (Altman & Hotchkiss 2006:102). Based on the above, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1(alt): There is a significant relationship between firm size and the direct costs of business rescue.

Several studies report that reorganisation costs increase with the time spent in proceedings (Altman & Hotchkiss 2006:98; Andrade & Kaplan 1998:1486; Armour et al. 2012:110; Ferris & Lawless 2000:657). To illustrate the above, professionals use the analogy of a rocket's 'burn rate' to refer to the rate at which their monthly fees accrue. This analogy suggests that the direct costs of reorganisation are primarily a function of the proceedings' length (LoPucki & Doherty 2004:128, 2008:990). Fees and other direct costs may be expected to increase the longer proceedings to continue, as practitioner and professional fees are often time based (Branch 2002:42; Citron & Wright 2008:76).

Coordination problems with the firm's stakeholders may result in prolonged reorganisation proceedings; thus, direct costs are likely to increase (Citron & Wright 2008:76). As direct costs are expected to increase with time, the firm's value is presumed to decrease as stakeholders deplete the firm's resources in a disagreement over the division of the firm's value (Andrade & Kaplan 1998:1486). In this instance, it is argued that agency problems arise. Therefore, stakeholders will support a value-destroying reorganisation as long as the value of their 'piece of the pie' is greater than that expected from a value-maximising alternative (Weiss & Wruck 1998:58). In contrast, Haugen and Senbet (1978:389) argue that stakeholder bargaining may not affect the firm value.

Several other factors may increase the duration of proceedings, such as external and environmental factors, the number of times creditors request revisions of the business rescue plan, the sources of post-commencement finance (PCF) sought and legal proceedings initiated by affected parties (Pretorius 2015:34). In a study conducted by Pretorius (2015:35), legal proceedings were identified as the key cause for extending proceedings. Based on the above, it can be hypothesised that:

H2(alt): There is a significant relationship between duration and the direct costs of business rescue.

Direct costs of business rescue proceedings

According to Section 143 of the Companies Act 71 of 2008 (hereafter referred to as 'the Act'), read with Regulation 128 of the Act, a BRP is entitled to charge the firm fees calculated on an hourly basis. The basic remuneration of a BRP is determined depending on the firm's size as defined by its Public Interest Score (PI Score) (Turnaround Management Association [TMA] 2015:1). The following tariffs are prescribed in Regulation 128 and may not be exceeded:

-

R1250 per hour, to a maximum of R15 625 per day (inclusive of value-added tax [VAT]), for a small firm;

-

R1500 per hour, to a maximum of R18 750 per day (inclusive of VAT), for a medium-sized firm; and

-

R2000 per hour, to a maximum of R25 000 per day (inclusive of VAT), for a large or a state-owned firm.

There is no limit to what a BRP can charge, as their fees are dependent on the duration of proceedings (Levenstein 2015:290). The following items are considered as an appropriate guideline for the calculation of a BRP's basic remuneration (TMA 2015:2):

-

Time spent acting as the BRP of a firm.

-

Any time spent travelling by the BRP in the discharge of duties and responsibilities.

-

Any planning, preparation and assessments completed or undertaken by the BRP in the discharge of their duties.

Regulation 128 further stipulates that the firm pays for the BRP's costs and disbursements that are reasonably required to carry out their functions and facilitate proceedings. However, the Act does not specify what these costs and disbursements entail (Levenstein 2015:481). Costs and disbursements may include professional indemnity insurance and other expenses reasonably incurred by the BRP, including travelling expenses.

These costs and disbursements further include the cost of appointing various professionals to assist the BRP in carrying out their functions (Braatvedt 2014:23; TMA 2015:5). Business rescue practitioners are commonly faced with a firm with incomplete information or unreliable and dysfunctional management. In this instance, the BRP has the power to appoint an advisor to assist with finding a proper solution. These professionals may include specialist advisors, lawyers, valuators and second or co-appointed BRPs (Pretorius 2015:37). In a study conducted by Pretorius (2015), BRPs indicated that using professionals is necessary to ensure compliance with time prescriptions and may assist with rapidly completing proceedings.

According to Section 143 of the Act, the BRP and the firm may enter into an agreement providing for further remuneration on a contingency basis relating to:

-

The adoption of a business rescue plan at all, or within a certain time, or the inclusion of any particular matter within such a plan; or

-

The attainment of any result or combination of results relating to the business rescue proceedings.

Contingency fees, also referred to as 'success-based fees', should be clearly aligned with the milestones set out in the business rescue plan. Contingency fees must be approved by the holders of a majority of the creditors' voting interests at the requisite meetings called to consider such an agreement. Therefore, contingency fees vary from case to case (Levenstein 2015:423; TMA 2015:3).

Contingency fees are accepted based on percentage payments in line with objectives set out during proceedings and on the implementation of the business rescue plan (Levenstein 2015:424). In addition, contingency fees may be linked to value obtained on the sale of the firm's assets. The TMA (2015:3) advises that a contingency fee based purely on a percentage of the asset realisations should be avoided unless the purpose of the business rescue is to conduct an informal wind-down. In the case of a wind-down, it is recommended that the BRP should receive a percentage only after a minimum threshold has been achieved.

A review of the literature has highlighted that research has not yet established the nature or size of the direct costs of business rescue. It appears that there are mixed opinions on what a BRP is entitled to charge; however, the issue is not about what the BRP may charge on an hourly basis. The Act and Regulations prescribe an hourly tariff that a BRP may charge. The problem is that the Act allows the BRP to be reimbursed for all costs and disbursements; however, the Act does not prescribe what these costs and disbursements may entail. In addition, as there is no time limit to the duration of proceedings, this creates room for inflating business rescue costs. There are no mechanisms to ensure that the fees, especially professional fees, stay within reasonable limits. As far as the additional remuneration is concerned, the Act is not prescriptive regarding what a BRP may or may not charge (TMA 2015).

The above discussion has highlighted a need to identify the direct costs of business rescue and provide affected parties with a more transparent and comprehensive understanding of these costs. In addition, there is a need to understand the size and determinants of the direct costs before the legislator and regulator can discuss ways to reduce these costs (Betker 1997:57).

Research methodology

A mixed-method approach was employed in this study. This study's strategy was one of exploratory sequential research whereby qualitative interviews were conducted in the first phase, followed by a quantitative survey in the second phase (Creswell 2014:276).

The qualitative interviews were conducted during the first phase to identify the direct costs of business rescue and these costs' components. Additionally, the qualitative phase results were used to develop an instrument to measure these costs for firms previously under business rescue in South Africa. The data were collected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of 14 BRPs from the Gauteng Province in South Africa. The interviews lasted between 15 and 91 min, with an average duration of 37 min.

In addition to semi-structured interviews, a card-sort technique was used to supplement the discussion guide. The card-sort technique allows participants to sort through word or phrase cards, prompting ideas that would otherwise remain unarticulated. According to Crilly, Blackwell and Clarkson (2006:342), this promotes a general discussion.

A closed card sort was used in this study. The researchers provided participants with categories, and participants had to choose which of the cards belong to a given category (Fincher & Tenenberg 2005:89; Rugg & McGeorge 2005:95). The researchers provided participants with four direct cost categories, and the components that make up these categories were printed on cards. Participants were interviewed at the end of the sorting exercise.

The data analysis occurred in a series of steps. The first step was to analyse the card-sort data. A simple way to analyse closed card-sort data is to document the results using a spreadsheet, with categories placed in the top row and cards placed in the first column (Spencer 2009:129). The card-sort data were first recorded in a component-by-category results matrix. The results matrix shows the number of times each card was sorted into the pre-set categories (Spencer 2018). The researchers then created a popular-placements matrix showing the percentage of participants who sorted each card into the corresponding category (Spencer 2018). The next step involved a thematic analysis of the interview data. Inductive codes were generated from the data and combined with codes identified from the card sort. Therefore, data were coded according to the individual cost components and categories of the card sort. The findings derived from the thematic analysis were used to inform the results of the data collected from the card sort.

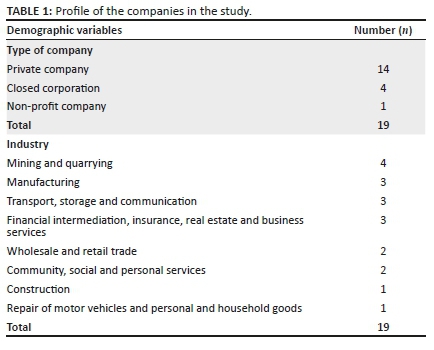

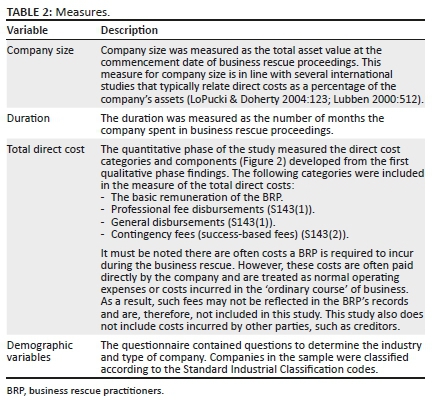

In the second phase, the quantitative study aimed to measure the direct costs and their components derived from the qualitative phase. Data on the direct costs of business rescue cases were only available from BRPs; therefore, a non-probability sampling method, specifically purposive sampling, was considered appropriate for this study. Business rescue practitioners were given inclusion and exclusion criteria regarding the business rescue cases and the BRPs ultimately selected the cases to share. Participants were requested to exclude special purpose entities, which are legal entities created to fulfil narrow, specific or temporary objectives (e.g. firms with the sole purpose of housing a single asset) (Sainati, Brookes & Locatelli 2016:58). In addition, participants were asked to only include firms where the business rescue plan was published. The quantitative data were collected through self-administered questionnaires completed by the participants. The questionnaire was administered electronically using an online platform that allows users to create and distribute questionnaires. The researchers asked all 14 participants who took part in the study's first phase to complete the questionnaire. The second phase of the study had a response rate of 43%, as only six participants agreed to complete the questionnaire. Five participants completed the questionnaire for three business rescue cases, whilst one participant completed the questionnaire for one business rescue case. As a result, 19 business rescue cases were incorporated into the study. The sample consisted of 19 firms from various industries that comprised 14 private companies, 4 closed corporations and 1 non-profit company. Table 1 displays the profile of the companies in the study in terms of the company type and industry. Most of the sample consisted of private companies (n = 14), and most of the companies were from the mining and quarrying industry (n = 4). Table 2 describes all the variables measured in the quantitative phase of the study.

Phase one: Qualitative findings

A popular-placements matrix showing the percentage of participants who sorted each direct cost component into a corresponding category is listed in Table 3. All participants interviewed supported the four direct cost categories as categories to classify the direct costs incurred to the BRP during business rescue proceedings. Each category consists of various components and is expounded on in detail in the following section. The results of the qualitative phase were used to develop the survey instrument administered during the quantitative phase. The first row of Table 3 displays the four direct cost categories, whilst the first column displays the direct cost components.

Basic remuneration of the business rescue practitioner

According to 93% of the participants, it is fair and common practice to charge the firm an hourly rate for time spent travelling in terms of professional standards. Seventy percent of participants agree that, in cases where the BRP files for proceedings, the process of filing would be included as part of the BRP's basic remuneration. It was pointed out that several BRPs charge significant once-off fees to file for business rescue on behalf of the firm. The reasoning behind this practice is that it shows the firm's dedication and financial ability to save the firm.

Participants expressed numerous issues with the hourly tariff prescribed in the Act's Regulations. Firstly, the hourly rate is too low considering the associated professional risks with the BRP profession. Secondly, participants highlighted that the hourly rate does not consider the complexity of each case, as the hourly rate is dependent on only the firm's PI Score. Lastly, participants believe that the hourly rate is not necessarily large enough to attract highly skilled and competent professionals to the field. This is because the prescribed hourly rate is not commensurate with the seniority and experience of some BRPs. As a result of the above argument, 12 participants stated that they adjust their fees for inflation or use contingency fees (discussed below).

Professional fee disbursements (S143(1))

Legal fees were found to be the largest professional fee disbursement during proceedings. This is in line with the findings of Pretorius (2015). A firm may incur legal fees during proceedings for several reasons. According to participants, creditors may not understand proceedings; therefore, disputes often arise. In addition, legal services may be required to renegotiate agreements suspended according to Section 136 of the Act. Lastly, if retrenchments are part of the plan, as is often the case in some turnaround situations, BRPs may need to enlist labour lawyers' services (Trahms, Ndofor & Sirmon 2013:1294).

According to participants, bookkeepers, accountants and auditors are usually already employed by the firm, and these costs are part of the firm's routine operating expenses. Depending on how good the firm's staff are, the BRP might bring their team or third parties to support the business rescue. It may be necessary to enlist these professionals' services to evaluate the data integrity of the firm's financial statements. These services are essential for the compilation of the business rescue plan.

The services of auctioneers and estate agents may be required in cases where the BRP would need to dispose off assets. Participants stated that the likelihood of the BRP disposing off assets effectively within the business rescue environment is small; therefore, auctioneers and estate agents would be required.

The services of a valuator are essential for the compilation of the business rescue plan, as the Act requires a BRP to calculate the probable dividend that creditors would receive should the firm be liquidated immediately. An independent valuation of the firm's assets is necessary for the BRP to calculate a fair and objective value. Furthermore, the Act provides for the BRP to sell assets during proceedings; therefore, an independent valuation of the assets is essential to ensure BRPs sell assets at a fair value.

According to 86% of participants, a liquidator's services are essential to determine the liquidation valuation. These participants stressed that an independent valuation is critical to protect themselves from creditors. In contrast, 14% of participants believe an independent valuation of the liquidation valuation is not required. Interestingly, only some participants believe that it is a requirement set out in the Act.

According to participants, BRPs are not experts in all business fields. Therefore, participants suggested that it is often essential to enlist experts and advisors' services during proceedings. Typical experts required during proceedings may include corporate governance specialists, engineers, tax specialists, mining specialists and retail experts.

General disbursements (S143(1))

All participants agree that BRPs are entitled to recover travelling expenses. This fee is typically calculated using the Automobile Association tariffs as a guideline. Ninety-three percent of participants recover the costs of professional indemnity insurance from the firms during proceedings.

According to 57% of participants, it is fair and common practice to charge a firm for administrative expenses. Administrative expenses include, for example, charging the firm for the costs of telephone calls, photocopies and faxes. All participants recover the costs of administrative services from firms during business rescue. Administrative personnel are typically part of the BRP's team and perform mundane tasks, allowing the BRP to focus on the business rescue effort. Administrative services are usually charged at a lower hourly rate than a BRPs rate; therefore, it is beneficial for the firm to save costs.

Contingency fees (success-based fees) (S143(2))

Participants stated that the hourly rate prescribed in the Act is not adequate to make accepting business rescue appointments worthwhile. As a result, contingency fees are significant as BRPs often use them to increase their hourly rate.

According to 79% of participants, charging a contingency fee on adopting the business rescue plan is fair and common practice. These participants suggested that this fee is considered appropriate on the condition that the requirements for substantial implementation are sufficiently set out in the plan. This fee is normally negotiated, and BRPs typically charge a lump sum fee or premium for the business rescue hours until that point. The premium is generally charged against the hours going forward; in other words, the BRP negotiates an increased hourly rate. However, 21% of participants do not agree with charging this contingency fee for various reasons. Firstly, it is argued that one of the functions of a BRP is to develop a plan and eventually get creditors to vote the plan in. Secondly, it is argued that this fee may create a conflict of interest as the BRP may agree to arbitrary requests made by creditors to get the plan voted in. Lastly, participants stated that, with this fee, there is a view that the BRP may be motivated to get the plan voted in, receive the payment and then abandon proceedings.

Ninety-three percent of participants agree that a BRP has the right to charge a contingency fee on the business rescue plan's substantial implementation. Participants stated that this fee encourages BRPs to not drag out proceedings unduly. Participants agree with this fee as the BRP is only compensated once the business rescue is complete and the plan is fully implemented. With this fee, participants believe that the BRP is motivated to implement the business rescue plan more efficiently and not encouraged to simply have the plan adopted. This fee is negotiated, and BRPs typically charge a lump sum fee or premium for the total hours spent on proceedings.

Seventy-one percent of participants agree that the BRP is entitled to charge a commission on the sale of the business as a going concern. Twenty-nine percent of participants do not agree with charging this fee. These participants believe that the sale of a business as a growing concern is part of the BRPs function; therefore, a BRP should not be compensated for it. Participants stated that under certain conditions, this fee could be acceptable. However, the BRP should only receive a commission once a minimum threshold, in terms of the sale price, has been achieved.

Fifty percent of participants agree with charging a commission on the sale of movable assets during business rescue proceedings, whilst 57% of participants agree with charging a commission on the sale of immovable assets. Participants agree to these fees only if the BRP is responsible for the disposal of those assets. Participants stated that this fee might be acceptable and even beneficial in a wind-down scenario. In a wind-down scenario, the firm may not have enough funds available to pay the BRP; therefore, the BRP can receive payment in the form of commission on asset sales. This type of remuneration agreement provides the BRP with the motivation to sell the assets at the best possible price. On the other hand, 50% of participants do not agree with charging a commission on the sale of movable property, and 43% of participants do not agree with charging a commission on the sale of immovable property. Participants believe that this commission may encourage the BRP to sell more assets than needed. Participants stated that a BRP should enlist professionals who are experts in disposing of assets to obtain the best possible value.

Eighty percent of participants agree that a BRP may charge a contingency fee linked to the percentage of dividends paid to creditors. This fee is typically calculated as a percentage of the difference between the business rescue dividend and liquidation dividend presented in the business rescue plan. Participants agree with this fee as it links the BRP's remuneration to creditors' dividends; therefore, for the BRP to receive the remuneration, creditors must be paid. Moreover, participants view this fee as an incentive for a BRP to do their best to receive the highest value for the creditors.

Participants agree that a BRP may receive remuneration based on the firm's performance after proceedings have ended. Participants agree with this fee, as it is a good indication of how well the BRP executed proceedings. This fee may be calculated as a percentage of profits. However, one participant believes that this fee should only be payable to the extent that the firm's profits exceed the projected value.

Sixty-seven percent of participants agree that a BRP may be entitled to become a firm shareholder once proceedings have ended. This fee may result in the BRP receiving shares, provided the share price exceeds a projected target after proceedings. This fee may also be appropriate if the firm does not have the cash available to pay the BRP's remuneration. On the other hand, 33% of participants believe that receiving shares, even after proceedings, still creates an independence issue and a conflict of interest. This is because the BRP will be motivated to reduce the firm's debt, whereas the purpose of proceedings is to optimise the recovery for the creditors.

Fifty-seven percent of participants believe a BRP should not be entitled to charge a fee on raising PCF during proceedings. Firstly, PCF already comes at a high cost; therefore, BRPs should not receive a commission. Secondly, it is argued that the task of raising PCF falls within a BRPs functions; therefore, the BRP should not receive further compensation beyond the hourly rate. Thirdly, one participant stated that if a BRP receives compensation for raising PCF, there is no incentive to reduce the costs associated with raising PCF. Lastly, one participant argued that receiving this fee may motivate BRPs to raise PCF from parties such as loan sharks. In contrast, 43% of participants agree with charging a fee on raising PCF. Participants argue that raising PCF is a difficult task and, provided that the PCF is raised from an external party, the BRP should be entitled to receive this fee.

Fifty-seven percent of participants believe a BRP should not charge a commission on the sale of the firm's interests or shares. Participants argue that if the BRP sells shares during the business rescue, it should be a separate arrangement between the sellers and the BRP. In contrast, participants stated that it might be acceptable if the sale of shares is part of the business rescue's absolute strategy or in the context of the sale of the business. Participants argue that a BRP should not receive this fee as they may be motivated to increase the shares' value by reducing the recovery by creditors to receive a larger commission.

Eighty-six percent of participants disagree that a BRP should charge a contingency fee on the discounts negotiated on behalf of the firm. Participants argue that charging this fee may incentivise the BRP to not act in the best interests of the creditors and, therefore, by charging this fee, the BRP may prejudice creditors. Participants argue that negotiating discounts is part of the BRPs function; therefore, the BRP should not receive compensation beyond the hourly rate.

Phase two: Quantitative findings

The purpose of the quantitative phase was to investigate the relationship between the direct costs of business rescue and the following variables: firm size and duration of business rescue proceedings.

The researchers are aware that a sample size of 19 firms is by no means enough to generalise the findings to the larger population. By conducting the second phase of the study, the researchers hope to initiate further exploration into the topic. The sample size for the second phase was small for various reasons. The researchers only distributed the survey to participants who were interviewed in the first phase of the study. This is because, given how sensitive the direct cost data are, it was essential to gain participants' support and trust during the first qualitative phase. In addition, the researchers could not reach a larger sample of participants because of time and cost constraints. Lastly, 8 of the 14 participants declined to participate in the second phase of the study because of the sensitivity of the cost data or because they did not have the time.

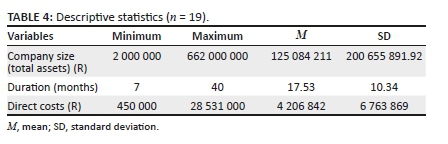

Descriptive statistics

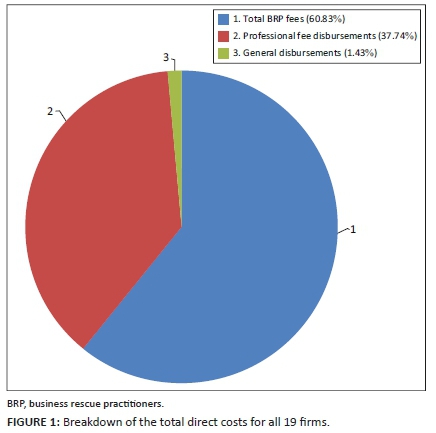

Table 4 displays the descriptive statistics of the sample firms. The average firm size, measured as total asset value at the commencement date, is R125 084 211. There is a great deal of variation in the present sample as firm size ranges from a minimum of R2 000 000 to a maximum of R662 000 000. Direct costs range from R450 000 to R28 531 000, with a mean level of R4 206 824. Total direct business rescue costs average 3.36% of the total asset value. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the total direct cost for all 19 firms.

Total BRP fees, which consisted of the BRP's basic remuneration and contingency fees, made up 60.83% of the total direct cost. Professional fees made up the second-largest direct cost component and 37.74% of the total direct cost. Of the total professional fees, 30.60% consisted of legal fees, whilst fees paid to other professionals only made up 7.14% of the total direct cost. Lastly, general disbursements consisted of 1.43% of the total direct cost.

The total BRP fees consisted of the BRP's basic remuneration and contingency fees (success-based fees) (143(2)). The primary reason for this is that, in some cases, the participants could not distinguish the difference between the two categories as contingency fees are often used to increase the BRP's basic remuneration. Therefore, the researchers combined the two categories.

Table 5 displays the descriptive statistics for the total BRP fees, professional fee disbursements and general disbursements.

Total BRP fees ranged from a minimum of R310 000 to a maximum of R15 100 000 with a mean of R2 559 158. Lawyers were the most widely used professionals in business rescue. A total of 16 out of 19 cases incurred legal fees. Legal fees range from R15 000 to R12 571 000 (M = R1 528 875). Valuators are the second most frequently used professionals in the sample (n = 10), with fees ranging from a minimum of R10 000 to a maximum of R160 000 (M = R59 100). Expert and advisory services (n = 9) fees range from R21 000 to R993 000, with a mean of R310 667. This is followed by bookkeepers, accountant and auditors' fees (n = 8), ranging from a minimum of R25 000 to a maximum of R732 000 (M = R217 750). It appears that the professionals used the least during proceedings are auctioneers and estate agents (n = 2) and liquidators (n = 2). The fees of the auctioneers and estate agents ranged from R60 000 to R292 000 with a mean of R176 000, whilst the fees of liquidators ranged from R99 000 to R125 000 with a mean of R112 000.

Table 5 displays that professional indemnity insurance is the most widely incurred general disbursement in the sample. A total of 12 of 19 firms incurred the cost of professional indemnity insurance. Professional indemnity insurance costs range from R12 000 to R223 000 (M = R44 833). Travelling expenses are the second most frequently incurred cost in the sample (n = 9), with expenses ranging from a minimum of R10 000 to a maximum of R80 000 (M = R35 111). The cost of administrative expenses and services (n = 5) fees range from R15 000 to R150 000, with a mean of R57 000.

Hypotheses tests

Hypotheses H1 and H2 deal with the correlation between (1) firm size and direct costs and (2) duration and direct costs, respectively. The relevant null and alternative hypotheses are stated below:

H1(null): There is no relationship between firm size and the direct costs of business rescue.

H1(alt): There is a significant relationship between firm size and the direct costs of business rescue.

H2(null): There is no relationship between duration and the direct costs of business rescue.

H2(alt): There is a significant relationship between duration and the direct costs of business rescue.

The above-mentioned hypotheses are both two-tailed (non-directional) hypotheses and were tested at a 5% level of significance (i.e., α = 0.05). The above-mentioned variables were measured at a ratio level of measurement; therefore, the appropriate parametric significance test is Pearson's product-moment correlation. This test assumes a linear relationship between each pair of variables being correlated and that both variables have a normal distribution (Pallant 2007:124). According to Field (2009:179), if the assumptions cannot be met, a non-parametric substitute, known as Spearman's rank-order correlation, should be used.

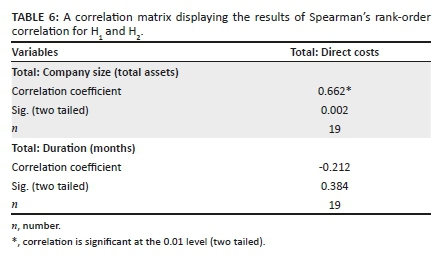

For each pair of variables, the assumption of normality was assessed through the KolmogorovSmirnov test, in combination with a visual perusal of histograms and normal probability plots. The assumption of linearity was tested through the visual inspection of a scatter plot (Field 2009:144). For all three variables, the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicate that the assumption of normality was violated. The scatter plots show that the assumption of linearity was not violated. The non-parametric Spearman's rank-order correlation was, therefore, used to test H1 and H2. According to Diamantopoulos and Schlegelmilch (2000:67), the use of non-parametric statistics is appropriate for small sample sizes (typically smaller than 30). Table 6 is a correlation matrix displaying the results of the two correlation analyses.

The results in Table 6 indicate a statistically significant, positive correlation between firm size and direct costs, rs, (17) = 0.662, p = 0.002. The coefficient of determination, r2, indicates that the two variables share a 43.8% common variance. This implies that only 43.8% of the variance in one variable is explained by the variance in the other. Adams and Lawrence (2015:234) describe this as a strong correlation, as the correlation coefficient is larger than 0.5. In summary, H1(null) was rejected in support of H1(alt). This suggests that there is a significant positive relationship between firm size and direct costs.

The correlation between direct costs and duration is not statistically significant, rs, (17) = −0.212, p = 0.384. H2(null) can, therefore, not be rejected in favour of the stated alternative hypothesis, H2(alt). The findings thus suggest that there is no relationship between duration and direct costs.

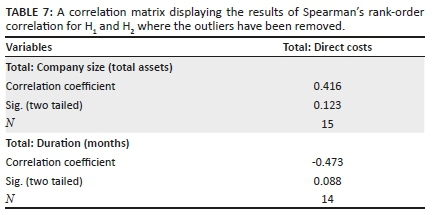

Outliers can dramatically affect the correlation coefficient, especially in small samples. Therefore, Pallant (2007:121) recommends removing outliers to reduce the effect they have on the correlation coefficient. The researchers removed the outliers, and the two hypotheses were tested. It must be noted that an advantage of Spearman's rank-order correlation is that outliers that were troublesome before ranking distort the resulting coefficient less than in Pearson's product-moment correlation. This is because the largest number in the distribution is equal to the sample size (Cooper & Schindler 2014:497; Tanner 2012). Table 7 is the correlation matrix displaying the results of the two correlation analyses after the outliers were removed.

Table 7 indicates that the correlation between firm size and direct costs is not statistically significant, rs, (13) = 0.416, p = 0.123. H1(null) is, therefore, not rejected. Thus, the findings suggest that no relationship between firm size and direct costs exists once outliers are removed.

The findings in Table 7 also show that once outliers are removed, the correlation between duration and direct costs is not statistically significant, rs, (12) = −0.473, p = 0.088. H2(null) can, therefore, not be rejected in favour of the stated alternative hypothesis, H2(alt). The findings, therefore, suggest that there is no relationship between duration and direct costs.

Discussion and conclusion

The study commenced as a qualitative exploration to identify the direct costs of business rescue. Thereafter, the direct costs identified from the qualitative data analysis were measured in the quantitative phase of this study. This study also examined the relationship between the direct costs of business rescue and the variables firm size and duration of business rescue proceedings. In summary, Figure 2 shows the direct costs of business rescue, which consist of four categories.

The findings reveal that total direct costs average 3.36% of the total asset value. The total BRP fees, which consist of the BRP's basic remuneration and contingency fees, are the largest direct cost (60.83% of the total direct cost). Professional fee disbursements follow this. In line with the research conducted by Ferris and Lawless (2000:653) and Pretorius (2015:38), the study findings indicate that legal fees make up a significant portion of direct costs (30.60% of the total direct cost).

In line with previous international research on the direct costs of reorganisation, the study's findings reveal a significant positive relationship between firm size and the direct costs of business rescue (Campbell 1997:27; LoPucki & Doherty 2004:113). Therefore, direct costs increase with the size of the firm. Larger business rescue cases are likely to be more complex, resulting in higher direct costs.

The findings suggest that there is no relationship between duration and the direct costs of business rescue proceedings. These findings are in line with those of Lubben (2008:80), who suggests that time spent in proceedings has no significant relationship with direct costs. These results are surprising given that BRPs and professional fees are time based; therefore, direct costs are expected to increase the time longer proceedings take.

In a separate analysis, the researchers removed the outliers for both H1 and H2, and the two hypotheses were tested. Once outliers were removed, the findings for H1 suggest that there is no relationship between firm size and the direct costs of business rescue. The results for H2 indicate that there is no statistically significant relationship between duration and the direct costs of business rescue. The conflicting findings are not surprising given that Pallant (2007:121) indicates that outliers can dramatically affect the correlation coefficient, especially in small samples.

Limitations and directions for future research

The qualitative phase of this study presents three main limitations. Firstly, given how the costs of business rescue have been blamed for the low success rates, according to Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2009:327), participants' responses may be subject to social desirability bias. Secondly, the qualitative phase considered only one stakeholder group's perspective, namely that of the BRP. Lastly, although it is suggested that 6-12 interviews are enough for qualitative research (Guest, Bunce & Johnson 2006:61), the researchers acknowledge that the number of participants interviewed in the first phase may limit the generalisability of the findings. Although the results cannot be generalised, this study provides a starting point for future research into the direct costs of business rescue proceedings.

Future research should examine the total direct cost of business rescue proceedings by collecting documents and conducting a document analysis to ensure all costs are included. This could result in identifying new direct cost components not identified in this study. Future research should include retrenchment costs and costs incurred to parties other than the BRP and firm. This may help provide a better reflection of the magnitude of the total direct cost of business rescue.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Both N.V.A.d.A and W.R-S. contributed equally to this work.

Ethical considerations

Approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of Pretoria, protocol reference number: EMS048/17.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, N.V.A.d.A. The data are not publicly available because of restrictions, for example, their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Adams, E.S., 1993, 'Governance in Chapter 11 reorganizations: Reducing costs, improving results', Boston University Law Review 73, 581-635. [ Links ]

Adams, K.A. & Lawrence, E.K., 2015, Research methods, statistics, and applications, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Altman, E.I., 1984, 'A further empirical investigation of the bankruptcy cost question', The Journal of Finance 39(4), 1067-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1984.tb03893.x [ Links ]

Altman, E.I. & Hotchkiss, E., 2006, Corporate financial distress and bankruptcy: Predict and avoid bankruptcy, analyze and invest in distressed debt, 3rd edn., Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. [ Links ]

Andrade, G. & Kaplan, S.N., 1998, 'How costly is financial (not economic) distress? Evidence from highly leveraged transactions that became distressed', The Journal of Finance 53(5), 1443-1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00062 [ Links ]

Armour, J., Hsu, A. & Walters, A., 2012, 'The costs and benefits of secured creditor control in bankruptcy: Evidence of the UK', Review of Law and Economics 8(1), 101-135. https://doi.org/10.1515/1555-5879.1507 [ Links ]

Betker, B.L., 1997, 'The administrative costs of debt restructurings: Some recent evidence', Financial Management 26(4), 56-68. https://doi.org/10.2307/3666127 [ Links ]

Bhabra, G.S. & Yao, Y., 2011, 'Is bankruptcy costly? Recent evidence on the magnitude and determinants of indirect bankruptcy costs', Journal of Applied Finance & Banking 1(2), 39-68. [ Links ]

Braatvedt, K., 2014, 'Costs of business rescue', Without Prejudice 14(9), 23-24. [ Links ]

Bradstreet, R., Pretorius, M. & Mindlin, P., 2015, 'The wolf in sheep's clothing - When debtor-friendly is creditor-friendly: South Africa's business rescue and alternatives learned from the United States' Chapter 11', Journal of Corporate and Commercial Law & Practice 1(2), 1-41. [ Links ]

Branch, B., 2002, 'The cost of bankruptcy: A review', International Review of Financial Analysis 11(1), 39-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-5219(01)00068-0 [ Links ]

Bris, A., Welch, I. & Zhu, N., 2006, 'The costs of bankruptcy: Chapter 7 liquidation versus Chapter 11 reorganization', The Journal of Finance 61(3), 1253-1303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00872.x [ Links ]

Campbell, S.V., 1997, 'An investigation of the direct costs of bankruptcy reorganization for closely held firms', Journal of Small Business Management 35(3), 21-29. [ Links ]

Chen, G.M. & Merville, L.J., 1999, 'An analysis of the underreported magnitude of the total indirect costs of financial distress', Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 13(3), 277-293. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008370531669 [ Links ]

Citron, D. & Wright, M., 2008, 'Bankruptcy costs, leverage and multiple secured creditors: The case of management buy-outs', Accounting and Business Research 38(1), 71-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2008.9663320 [ Links ]

Companies and Intellectual Property Commission, 2018, Status of business rescue proceedings in South Africa March 2018, viewed 24 August 2018, from http://www.cipc.co.za/index.php/publications/business-rescue/. [ Links ]

Cooper, D.R. & Schindler, P.S., 2014, Business research methods, 12th edn., McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2014, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative & mixed method approaches, 4th edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Crilly, N., Blackwell, A.F. & Clarkson, P.J., 2006, 'Graphic elicitation: Using research diagrams as interview stimuli', Qualitative Research 6(3), 341-366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106065007 [ Links ]

Diamantopoulos, A. & Schlegelmilch, B.B., 2000, Taking the fear out of data analysis: A step-by-step approach, Cengage, London. [ Links ]

Ferris, S.P. & Lawless, R.M., 2000, 'The expenses of financial distress: The direct costs of Chapter 11', University of Pittsburgh Law Review 61, 629-669. [ Links ]

Field, A., 2009, Discovering statistics using SPSS, 3rd edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Fincher, S. & Tenenberg, J., 2005, 'Making sense of card sorting data', Expert Systems 22(3), 89-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0394.2005.00299.x [ Links ]

Fisher, T.C.G. & Martel, J., 2005, 'The irrelevance of bankruptcy costs to the firm's financial reorganization decision', Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 2(1), 151-169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2005.00034.x [ Links ]

Gilson, S., 2012, 'Coming through in a crisis: How Chapter 11 and the debt restructuring industry are helping to revive the U.S. economy', Journal of Applied Corporate Financing 24(4), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2012.00398.x [ Links ]

Gine, X. & Love, I., 2010, 'Do reorganisation costs matter for efficiency? Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Columbia', Journal of Law and Economics 53(4), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1086/605848 [ Links ]

Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L., 2006, 'How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability', Field Methods 18(1), 59-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903 [ Links ]

Haugen, R.A. & Senbet, L.W., 1978, 'The insignificance of bankruptcy costs to the theory of optimal capital structure', The Journal of Finance 33(2), 383-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1978.tb04855.x [ Links ]

Le Roux, I. & Duncan, K., 2013, 'The naked truth: Creditor understanding of business rescue: A small business perspective', The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management 6(1), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v6i1.33 [ Links ]

Levenstein, E., 2015, 'An appraisal of the new South African business rescue procedure', LLD thesis, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

LoPucki, L.M. & Doherty, J.W., 2004, 'The determinants of professional fees in large bankruptcy reorganization cases', Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 1(1), 111-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2004.00004.x [ Links ]

LoPucki, L.M. & Doherty, J.W., 2008, 'Professional overcharging in large bankruptcy reorganization cases', Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 5(4), 983-1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2008.00148.x [ Links ]

Loubser, A., 2013, 'Tilting at windmills? The quest for an effective corporate rescue procedure in South African Law', South African Mercantile Law Journal 25(4), 437-457. [ Links ]

Lubben, S.J., 2000, 'The direct costs of corporate reorganisation: An empirical examination of professional fees in large Chapter 11 cases', The American Bankruptcy Law Journal 74(4), 509-552. [ Links ]

Lubben, S.J., 2008, 'Corporate reorganization & professional fees', American Bankruptcy Law Journal 82, 77-140. [ Links ]

Pallant, J., 2007, SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows, 3rd edn., Open University Press, Buckingham. [ Links ]

Pretorius, M., 2015, Business rescue status quo report: final report, viewed 20 March 2016, from http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/151110Business_Rescue.pdf. [ Links ]

Pretorius, M. & Rosslyn-Smith, W., 2014, 'Expectations of a business rescue plan: International directives for Chapter 6 implementation', Southern African Business Review 18(2), 108-139. https://doi.org/10.25159/1998-8125/5681 [ Links ]

Pulvino, T.C., 1998, 'Do asset fire sales exist? An empirical investigation of commercial aircraft transactions', The Journal of Finance 53(3), 939-978. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00040 [ Links ]

Rugg, G. & McGeorge, P., 2005, 'The sorting techniques: A tutorial paper on card sorts, picture sorts and item sorts', Expert Systems 22(3), 94-107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0394.2005.00300.x [ Links ]

Sainati, T., Brookes, N. & Locatelli, G., 2016, 'Special purpose entities in megaprojects: Empty boxes or real companies?', Project Management Journal 48(2), 55-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/875697281704800205 [ Links ]

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A., 2009, Research methods for business students, 5th edn., Pearson Education, Harlow. [ Links ]

Spencer, D., 2009, Card sorting: Designing usable categories, Rosenfeld Media, Brooklyn, NY. [ Links ]

Spencer, D., 2018, Cart sorting 101: Your guide to creating and running an effective card sort, viewed 20 July 2018, from https://www.optimalworkshop.com/101/card-sorting#openResultsAnalysis [ Links ]

Tanner, D., 2012, Using statistics to make educational decisions, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Tashjian, E., Lease, R.C. & McConnell, J.J., 1996, 'Prepacks: An empirical analysis of prepackaged bankruptcies', Journal of Financial Economics 40(1), 135-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(95)00837-5 [ Links ]

Turnaround Management Association (TMA), 2015, Business rescue practitioners' fees, viewed 13 March 2017, from http://www.tma-sa.com/info-centre/practice-notes.html. [ Links ]

Trahms, C.A., Ndofor, H.A. & Sirmon, D.G., 2013, 'Organizational decline and turnaround: A review and agenda for future research', Journal of Management 39(5), 1277-1307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471390 [ Links ]

Weiss, L.A. & Wruck, K.H., 1998, 'Information problems, conflicts of interest, and asset stripping: Chapter 11's failure in the case of Eastern Airlines', Journal of Financial Economics 48(1), 57-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00004-X [ Links ]

White, M.J., 1989, 'The corporate bankruptcy decision', Journal of Economic Perspectives 3(2), 129-151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.3.2.129 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nicole de Abreu

nicole.deabreu@up.ac.za

Received: 19 Sept. 2020

Accepted: 18 May 2021

Published: 16 July 2021