Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.19 n.1 Johannesburg 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v19i1.692

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A qualitative approach to developing measurement scales for the concept of Ubuntu

Thembisile Molose; Peta Thomas; Geoff Goldman

Department of Business Management, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: This article provides a theoretical consolidation of Ubuntu antecedents to encourage understanding of the relationship between Ubuntu and organisational management.

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The Ubuntu conceptual elements - compassion, survival, group solidarity and respect and dignity - are appraised in the context of South African hospitality management

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Ubuntu elements were identified as a regional sub-cultural influence in South Africa in Hofstede's 1983 research on the influence of culture in managing organisations. Understanding the role of Ubuntu in management is argued as being important to effectively manage culturally diverse work teams in South Africa.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: Qualitative data were collected from judgementally selected hospitality industry participants (stage 1) as to their perceptions of antecedents of Ubuntu applicable to hotel frontline employee management. Consequently, a Delphi method (stage 2) was applied asking eight purposefully selected participants to review the proposed sub-variables of the four Ubuntu elements derived from stage 1 to establish a theoretical Ubuntu measurement scale.

MAIN FINDINGS: The research proposes a theoretical measurement scale for the four broad concepts of Ubuntu.

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Theoretically, this article contributes to management research for managing service orientated businesses. Practically, this research stresses the importance of Ubuntu motivational forces as mechanisms that service managers can implement in stimulating group collective achievement of organisational goals.

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: Ubuntu research has predominantly been conceptual related only to four elements (compassion, survival, group solidarity and respect and dignity) and no previous research has delineated antecedents for these elements to propose a multidimensional quantitative measurement scale for Ubuntu.

Keywords: South Africa; Ubuntu; hospitality; hotel; antecedents; Ubuntu management; Delphi method; exploratory study.

Introduction

A great deal of attention has been given to the study of the influence of Ubuntu [humanity] in the organisation (Brubaker 2013; Karsten & Illa 2005; Khoza 1994; Mangaliso 2001; Mbigi 1997; Poovan, Du Toit & Engelbrecht 2006; Qobo & Nyathi 2016; Sigger, Polak & Pennink 2010). Like many constructs in cross-cultural management, Ubuntu has been conceptualised in various ways. Common to these conceptualisations is a link with the promotion of human relations relating not only to an individual but also to the good of an individual's community (collectivism). Communities who exhibit Ubuntu behaviour are those that make clear that their actions interrelate to determine togetherness. With the exclusion of the work of Sigger et al. (2010) and Brubaker (2013), relatively little attention has been given to the development of measures of an Ubuntu style of management. Non-African and African authors have written about the philosophical tenets of Ubuntu in management practice (Brubaker 2013; Karsten & Illa 2005; Khoza 1994, 2005; Mangaliso 2001; Metz 2008; Mbigi 1997; Mbigi & Maree 1995; Poovan et al. 2006; Sigger et al. 2010). These writings (e.g. Broodryk 2002; Kamwangalu 1999; Mangaliso 2001; Mertz 2008; Nussbaum 2003; Qobo & Nyathi 2016; Tutu 2004) tend to lack empirical research foundation that supports claims about the usefulness of Ubuntu in managing an organisation. This clearly precipitates a need for empirical data that identify Ubuntu antecedents to propose a multidimensional quantitative measurement scale for Ubuntu let alone developing insights into the relevance of Ubuntu as a management style in South African organisations.

According to Mbigi (1997), African organisations should be inspired by Africa's own cultural heritage so that they can compete in the global marketplace using uniquely African management concepts embedded in the philosophy of Ubuntu. This has importance in the context of South African hospitality organisations where there are numerous reports concerning high labour turnover and persistent poor manager-employee relations (National Department of Tourism [NDT] 2011). A comment can be made therefore that the hospitality industry, particularly tourist hotel accommodation, provides a contextual research opportunity as presented in this article about the role of the Ubuntu philosophy in management practice.

In the context of South African hospitality, the attitude of frontline employees has consistently been linked with the problem of persistent poor service delivery which hampers tourist experience. Further, this has been linked as a direct result with poor management styles and generally poor employment conditions (Coughlan, Moolman & Haarhoff 2014; NDT 2011). The National Tourism Service Excellence Strategy developed in 2011 by the NDT in collaboration with the Department of Arts and Culture in South Africa identified Ubuntu as one of the building blocks that tourists associate with in their consumption of hospitality service. To this end, the strategy proposed that Ubuntu philosophy in tourist services should be used to showcase South Africa as unique in applying Ubuntu to create the perceptions of a friendly and welcoming tourist destination (NDT 2011). The role of collectivism as purported by adoption of an Ubuntu philosophy was identified in Browning's (2006) empirical research findings. Browning (2006) found that managers failed to provide hospitality frontline employees with the physical and emotional support they expected and needed as part of a service orientated collective group when dealing with difficult guests.

Browning (2006) concluded that hospitality service managers who behave in a way that contradicts the expectations of their frontline employees do not realise the positive influence that Ubuntu can have on how employees interact with guests. Conceptually, hospitality that is premised on welcoming and serving strangers by hosts (Westmoreland 2008) is typically featured in an Ubuntu-hospitality context. In Africa, it is traditionally widely accepted that a host will open his or her home to total strangers, giving them a place to stay and a meal to eat although he or she knows little about them (Brotherton & Wood 2008). In contexts like the one described, hospitality has existed with no boundaries (welcome a stranger into the home) (Westmoreland 2008). This article explores how the influence of Ubuntu as a style of management can influence frontline manager's positive attitudes and service quality improvements in the context of South African tourist hotel accommodation.

Purpose and objectives

The primary objective of the article was to find themes from which to derive a multidimensional scale to measure the usefulness of Ubuntu in the hospitality sector. The specific aims were to:

-

Explore the literature on Ubuntu to identify themes and antecedent conditions that can be used to describe Ubuntu management practice.

-

Conduct an empirical investigation among hospitality frontline managers and academics to which establish antecedents of the Ubuntu elements of compassion, survival, group solidarity and respect and dignity that would be anticipated to help develop a quantitative measurement scale of Ubuntu management for examination of its application to the organisation.

-

Explore to what extent the management styles of South African hospitality managers can be classified as Ubuntu and their usefulness in team performance.

-

Propose the development of a multi-measurement tool of the Ubuntu concept to enable future empirical studies, and empirical data collected in South African organisations.

The conceptualisation of Ubuntu: A literature review

Like any other cultural elements or dimensions in organisation theory, Ubuntu has been conceptualised and measured in various ways: several conceptualisations of Ubuntu and what comprises its antecedents of compassion, survival, solidarity and respect and dignity (Broodryk 2005; Khoza 2005; Mbigi & Maree 1995; Tutu 1995). Ubuntu has begun to gain prominence in a myriad of academic fields and discourses, both in South Africa and beyond in knowledge domains as varied as law, media, theology, education, sport, servant leadership and public policy ethics among others (House et al. 2004; McAllister 2009; Qobo & Nyathi 2016; Richardson 2008). Mbigi (2000) and Nussbaum (2003) perceive Ubuntu as an expression of an African view of the life world anchored in Africa's own persons, cultures and societies, which is difficult to define in a Western context. Common to all the conceptualisations of Ubuntu found in the literature is a link with South Africa's Zulu-Xhosa aphorism, Umntu-ngumntungabantu which means that 'each individual's humanity is expressed in relations with others' (Battle 1996:99). Simply put this means, 'a person is a person through other people' (McAllister 2009:2; Poovan et al. 2006:17). This latter aphorism according to Mangaliso (2001) conveys the notion that a person becomes a person only through his or her relationship with, and recognition by, others. Tutu (2004) gives credence to this particular Ubuntu aphorism by pointing out that it is one unique concept that Africa can offer to the world. Therefore, this article argues that the contribution that recognises the value of Ubuntu to service management knowledge is through its extension of existing theories of individual-collectivism cultural dimensions for directing high service quality team performance. More practically, Ubuntu supports group solidarity in team work and, in turn, a collective achievement orientation by employees to attaining organisational goals. This aphorism suggests that Ubuntu is a phenomenon that can promote common understanding of work as a collective output between a manager and his work teams by promoting that as a team, they help and care for each other as they would members of one family or community as suggested by (Tutu 2004).

The Ubuntu aphorism is further adopted widely by southern African Nguni speaking people having equivalent phrases extending beyond South Africa to other sub-Saharan African countries. Broodryk (2005) reflects that the concept of Ubuntu is expressed in many different African languages, always emphasising a relationship with collectivism as a community. In Kenya, the concept of Ubuntu is talked about as 'Utu' referring to the idea that every individual's action should be performed for the benefit of the whole community (Broodryk 2005:219; Oppenheim 2012:370). In Uganda, the concept is known as Obuntu-bulamu translating to an individual's human generosity, and harmonious interaction with, one's own community (Oppenheim 2012:370). Mangaliso (2001:24) defines Ubuntu as humaneness - a pervasive spirit of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness - that individuals and groups display for one another. Mangaliso (2001) goes further to suggest that Ubuntu is invariably invoked as a scale for weighing good versus bad, right versus wrong and just versus unjust. The most prevalent understanding of Ubuntu in the literature is when it is considered 'an African humanness which is characterised by compassion or caring, sharing, communist democracy and related predispositions' (Khoza 2005:269). Khoza's view was taken up by Broodryk (2005:13) who described Ubuntu as a 'comprehensive, ancient African worldview which pursues primary values of intense humanness, caring, sharing and compassion, and associated values'. In public spaces, Ubuntu is perhaps best represented by public figures who regard Ubuntu as the essence of being human, which extends beyond African ways of life to include hospitality, kindness, warmth, welcoming, generosity and caring about others (Dandala 1996; Mthembu 1996; Tutu 1995). The article therefore asserts that, in the context of sub-Saharan Africa, communism (also referred to as collectivism) becomes understood as having group meaning expressed through Ubuntu (Broodryk 2005).

More important than language similarities, however, are to consider the differences between the various conceptualisations of Ubuntu. These differences involve the varying social ethic characteristics reflected in Ubuntu as a mode of conduct by individuals in contemporary life in terms of an individual reflecting antecedent traits such as hospitality, sharing, generosity and selflessness, that is, the behaviours that are expected to results from Ubuntu (Louw 2002; Mangaliso 2001; McAllister 2009; Theletsane 2012). Linked with such expected behaviours is group solidarity which is crucial to the survival of African communities who have historically survived through group care by the community for the community (Mbigi & Maree 1995). In this sense, Ubuntu proponents (Battle 1996; Ndaba 1994; Sono 1994) seek to increase understanding that the ideal value of Ubuntu is to connote a compromise by encouraging an exclusion of oppressive communalism but rather allowing a person to grow and prosper in a group relational setting by providing ongoing contact and interaction with others. There is a lack of consensus on the definition coupled with the scarcity of psychometrically robust measurement scales (Brubaker 2013). With the exception of limited empirical investigations (Brubaker 2013; Mabovula 2011; Mbhele 2015; Sigger et al. 2010), relatively little attention has been given to the development of measurement scales for Ubuntu that conform closely to the conceptualisation of the Ubuntu concept. Sigger et al. (2010) is a study that operationalised Ubuntu in terms of business management. Other studies tended to focus on leadership alone and not the role of collectivism (manager and workers) (Mangaliso 2001; Mbigi 1997, Mbigi & Maree 1995; Msila 2008; Nussbaum 2003; Poovan et al. 2006). Even though Sigger et al. (2010) need to be acknowledged in the development of measurement scales for Ubuntu, their stated scales reveal several limitations. Sigger et al. themselves (2010) acknowledged that their proposed items for the four Ubuntu elements met with a lack of understanding of the meaning of these items by respondents. Without firstly the development of a consensus on what Ubuntu is conceptually, based on the identification of the antecedents for each of the four Ubuntu elements, reliable scales cannot be constructed. Louw (2002:8) refers to Ubuntu as 'an account of innovative constructions, which, is inevitably coloured by our (post)modern values, beliefs and biases'. Louw (2002) argues that any attempt to answer the question, 'what is Ubuntu?' would be misguided, positing that the more important question is: 'How should Ubuntu be understood and utilised for the common good of all Africans, and of the world at large?' (Louw 2002:8). These questions underpin establishing a consensus about the composition of Ubuntu in the context of business management practice.

The four related elements of Ubuntu

This article focussed on the four elements of compassion, survival, group solidarity and respect and dignity as principles in common with other studies (Brubaker 2013; Mangaliso 2001; Poovan et al. 2006; Sigger et al. 2010). These elements and their antecedents as complemented by many authors are now discussed individually.

Antecedents of compassion

The first element of compassion involves understanding others' dilemmas and seeking to help because of the deep conviction of the interconnectedness of people (Poovan et al. 2006:18). By definition, it can simply be described as 'being moved by another's suffering and wanting to help' (Lazarus 1991:289). Muchiri (2011:433) extended the definition, stating that compassion is about an individual's expression of generosity out of concern for another, which is summarised as 'a willingness to sacrifice one's own self-interest to help others'. Similarly, Strauss et al. (2016) proposed that compassion entails consideration of the feelings that arise when one witnesses another's suffering, motivating a subsequent desire to help. A common thread in the compassion element of Ubuntu is that observing another human's suffering motivates another to extend help.

Antecedents of survival

The second element of Ubuntu is survival which Mbigi and Maree (1995) suggest can be expressed in the statements like 'an injury to one is an injury to all' where there is a shared will to survive (Poovan et al. 2006:18). In the context of South Africa and Ubuntu, the term 'survival' has in more recent times been attributed to continued endurance in difficult living experiences of South African black people during the apartheid regime (Poovan et al. 2006).

Antecedents of group solidarity

Nussbaum (2003) suggests that group solidarity permeates every aspect of an African's life and is collectively expressed through singing, effort at work, initiation and war rites, worship, traditional dancing, hymns, storytelling, body painting, celebrations, hunting, rituals and family life. These expressions could then be taken as antecedents of group solidarity. Seemingly, this is where respect and dignity through effort at work, celebrations and family life are built. Poovan et al. (2006) found that group solidarity is closely related to survival that is developed through the combined efforts of individuals in the service of their community. In a community such as a business organisation. Lutz (2009:318) states that group solidarity does indeed in a form 'tend to benefit the [workplace] community, as well as the larger communities of which it is a part'.

Antecedents of respect and dignity

Respect and dignity are considered important values in most societies and accepted as one of the building blocks in an African social culture as Ubuntu (Yukl 2002). In the context of South Africa, and in Zulu-Xhosa Nguni languages, respect means Ukuhlonipha or Unembeko lomntu translating as '[person has] respect' (Poovan et al. 2006:18). In addition, Mangaliso (2001) suggests that in an organisation, respect can be one of the building blocks for effectively managing diversely skilled work teams in Africa. Thus, when combined with dignity, this requires always valuing the worth of others as this supports respect and dignity for the individual from others (Mangaliso 2001). In 2019, Woermann and Engelbrecht propose Ubuntu principles in relation or stakeholder theory to be viewed as a way for promoting inclusive organisational decision-making (Woermann & Engelbrecht 2019). A contrary argument is presented by Smith (2017) who builds on Louw's (2002) sentiments, arguing that Ubuntu should also be seen from a subjective view. The views of Smith (2017) suggest that if Ubuntu connotes aspects such as welcoming strangers, it could also be accepted as unwelcoming in some instances. Smith articulates that if there is a saint, there is also a sinner in any situation and that while Ubuntu is touted as promoting relations among people, it may be also likely to distance some who do not like a collectivism approach from others, a subjective perspective that Smith (2017) called a process of 'transversatility'. Tavernaro-Haidarian (2018) deliberated on the concept viewing Ubuntu from a normative view in that Ubuntu can espouse a harmonious and cohesive way of relating to fellow beings but that this can contrast and actually complement individualist facets. Both views whatever one's own personal conception of what Ubuntu represents support House et al.'s (2004) assertion that African cultural Ubuntu will have influences as a distinctive philosophical concept that the sub-Saharan Africa managers could focus on. Hofstede's (1983) sentiments state that:

what people can bring about with culture is an important consideration for the understanding of how the culture in which people grew up and which is dear to them, affects their thinking differently from other people's thinking and, importantly, what it [this] means for the transfer of management practices. (p. 75)

Antecedent phrases for each element of Ubuntu that were consolidated from the reviewed literature have been to date been developed, as presented in Figure 1.

In view of the antecedents identified in Figure 1, the links between them and the academically established broad concepts of Ubuntu are compassion, survival, solidarity and respect and dignity. A synthesis of these academic authors' explanation for the four concepts with a measurement scale has not been proposed until presented by this research. Figure 1 highlights the advantage of being part of a community (either workplace or society) that cares about the others in its collective group and in so doing achieves group goals. Therefore, in a communist democracy, Ubuntu is touted as one of the building blocks for organising and in business management structures a manner of managing multicultural communities as suggested by Mangaliso (2001).

Building on established theory from Hofstede's (1983) articulation of cultural relativity in the business organisation, one of the simplest ways to recognise the contribution that an Ubuntu management style can make to the organisation in encouraging team productivity is to first recognise Ubuntu as a management style. In recognising this, a manager needs to show his or her selflessness, genuine personal work effort and authenticity to his collective through being there always, physically and emotionally for his or her team. More recent academic authors support this. Mangaliso (2001) notes that applying Ubuntu principles as a manager aims to achieve group solidarity and teamwork with a collective pride in achieving set organisational goals. Tutu (2004) concurs affirming that it is only possible when there is a common understanding between the manager and team members, and that they are together building a culture of help and care for each other as members of one family or work group. To this end, the contribution of Ubuntu as a management concept is vital to understanding because it complements existing academic knowledge of business management practices that have to date been predominantly developed in Europe and the USA (Hofstede 1983). Sigger et al. (2010) developed a measurement scale for Ubuntu which was tested among a sample of managers in varied Tanzanian organisations. These authors themselves acknowledged that the lack of participants' understanding of the literal meaning of questions led to their scale usefulness being inappropriate. These authors concluded that a more relevant measurement tool still needed to be developed (Sigger et al. 2010:24). Strauss et al. (2016:18) developed compassion measures based on managers or co-workers, noticing other's suffering, empathy, kindness, caring, mindfulness, common humanity and or emotional resonance. This literature was considered in stage 1 through probing in participant interviews. This next section details how a theoretical quantitative measurement scale was developed from the concepts synthesised through reviewing academic literature.

Research methods and design

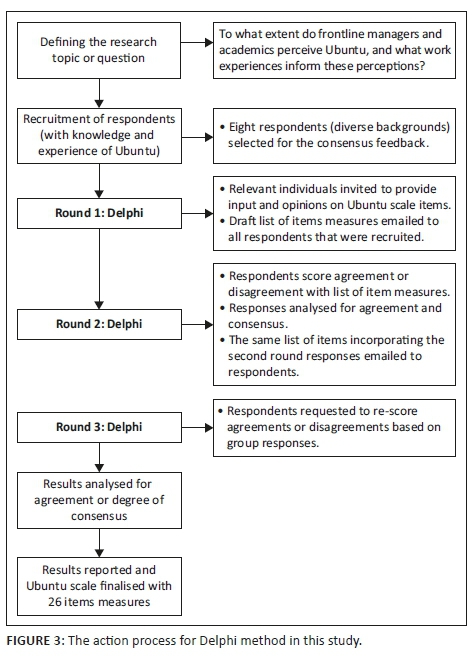

A sequential exploratory research design was adopted. The deficiency of the literature on Ubuntu as a management practice advocated this research as exploratory and qualitative for stages 1 and 2 (Figures 2 and 3) of the research to identify the items that could be consolidated to create a quantitative measurement scale (Creswell 2009:211; Guba 1990:81; Rodwell 1998:27). Qualitative researchers use ideas from the people they study and place them within the context of a natural setting of the research (Creswell 2009:207; Neuman 2006:157; Rodwell 1998:27). Qualitative research is usually categorised within an inductive research approach (Rodwell 1998:27), 'an inquiry process of understanding a social or human problem, based on building a complex, holistic picture, formed with words and reporting the views of informants within a natural setting' (Creswell 1994:2; Gay & Airasian 2000:627). Commencing this programme of research through qualitative interviews (stage 1) and a Delphi study (stage 2) using the results of stage 1 enabled the meaning of Ubuntu (on which there is a paucity in the literature) in terms of constructs to be clarified. The South African tourist hotel sector offered a unique opportunity for understanding the process by which service staff conceives Ubuntu as a consideration in their management. Purposeful sampling such as applied in this research was used so that participants were selected based on their experience of the central research phenomenon (Creswell 2009:217). The stages of the research are now explained.

Stage 1: Qualitative interviews

The first step involved the collection of data by interviewing 25 purposefully selected (15 South African hospitality frontline managers and 10 South African hospitality academic lecturers or instructors) as research participants, and analysing this data. South African hotel frontline managers were chosen as they are characterised by their role in interfacing through management practice or training with frontline employees ensuring consistent service quality delivery for customers (welcoming strangers). South African academics teaching and training in South African universities were chosen as they have insight into the usefulness of Ubuntu as a management style in a South African hotel context. Criteria for selection for this research were individuals knowledgeable as follows:

-

Academic - currently teaching hospitality management programmes.

-

Academic and hotel frontline managers - ability to speak any one of the indigenous African-Nguni languages and/or knowledgeable about the concept of Ubuntu.

-

Academic and hotel frontline managers - employed more than 12 months to ensure intimate knowledge of customer service requirements in the South African hospitality industry.

Initiating permission for interviews to be held required that contact be first made with the head office of each university or hotel group. The hotel chains approached for the research were wholly South African owned (to ensure employee service training reflected South African management aspects and employee cultural diversity in service teams) with a presence in each of the nine provinces (to ensure diversity in opinions of managers on the role of Ubuntu in their management styles). Two South African hotel groups agreed to be involved, four hotels for the first and three hotels for the second hotel group. Lecturers from four South African public universities agreed to be involved.

Invitation letters to participate were sent via email. The types of frontline manager in a hotel are broad, so to gather diverse perceptions, managers from front office, housekeeping, restaurants and banqueting or conferencing were approached, that is, front office (five participants), food and beverage (seven participants) and housekeeping (three participants). Esterberg (2002) recommends a sample minimum size of 12 as adequate for generating themes for exploratory analysis. The one-on-one interviews using a semi-structured interview schedule that interrogated the value in management of the four principal Ubuntu themes in hospitality service management were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim and content analysis conducted. The content analysis conducted on the transcribed interviews (Figure 2) established additional 16 items that described the four-key Ubuntu concepts. These items found support in the Ubuntu scale development literature (Brubaker 2013; Sigger et al. 2010; Strauss et al. 2016).

Stage 2: Delphi method

Application of a Delphi technique assists researchers to arrive at 'effective decisions about the data being interpreted in situations that present insufficient information for scale development' (Hasson, Keeney & McKenna 2000:1008). A Delphi technique can be viewed as a 'method for consensus-building' among a group of 'experts or knowledgeable participants' (Van Dun, Hicks & Wilderom 2016:4). The Delphi survey was implemented to review the trustworthiness of 16 proposed Ubuntu item measures derived from stage 1 interviews. The decision about who to invite to participate entailed a purposeful selection of participants with expert knowledge of Ubuntu (Hasson et al. 2000). Eight purposefully selected academic participants were invited to provide their expert input on the proposed 16 scale items. The Delphi study participants included six men and two women. Three of them were Xhosa speaking, two Ndebele, one Zulu and two English speaking thereby eliciting a wide knowledge base. Five participants through their upbringing and associated culture understood the concepts of Ubuntu and three had a good theoretical knowledge of Ubuntu. Employing a sample of between six is not rare in Delphi studies. Previous research (Gustafson et al. 1973) used a sample size of four participants involving two rounds; Nambisan, Agarwal and Tanniru (1999:374) with six research participants with three rounds. Accordingly, the period recommended for the participants to complete the iterative rounds of Delphi study ranges between 1 and 3 months (Okoli & Pawlowski 2004:10). Round 1 was to determine individual opinions of each of the 16 scale items from the eight participants (Hasson et al. 2000:1011). Participants were requested to judge individual concept items in terms of their ability to measure the four constructs of Ubuntu in management practice. Hasson et al. (2000) draw attention to the detail that in applying the Delphi survey-consensus method, constitute collective group consensus from the participants should be in the range 51 % - 80 %. An average of 68 % - 82 % group consensus was attained through each of rounds 1-3, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Two of the eight participants did not return their responses for inclusion in the analysis of rounds 2 and 3, resulting in a lower but acceptable response rate. In the second round, participants were requested to rate each of the 16 item statements (amended from round 1 feedback) and rate an additional 10 items added from participant round 1 feedback. Six of the 10 items corresponded with the collectivism element of Ubuntu identified by Hofstede (1983) and House et al. (2004). The 10 additional items were among the measures added to the original 16 items that participants felt should be split into individual items. The intent in this round was to assess the extent of agreement (consensus on the measurement scales) among the participants, and to resolve any further disagreements (consensus development) (Jones & Hunter 1995:377). These participants provided input and opinions finally agreeing with the pool of 26 Ubuntu item measures in round 3.

Discussion of findings

During the content analysis process of stage 1 transcribed interviews, codes emerged reflecting the four principal elements of Ubuntu as identified in reviewed literature. A second level of codes also emerged representing both positive and negative elements of an Ubuntu type management style applied in the hospitality service work place. Positive accounts broadly reflected participant reflections on manager-subordinate relationships, expressing that manager and employee do indeed need each other to succeed in attaining goals emphasising that the success of a manager depends on the people working for him or her. Negative issues raised were the issue of managers not obtaining the views of employees on how to improve work, and managers actively creating a space between them and the employees, thus distancing themselves from the employee work teams (individualism). Participants indicated that they were consciously aware that creating and maintaining unity and social relationships is a process that is complex and could be impeded by different cultural backgrounds. From these findings and supplemented by extant literature, a scale of 16 items related to describing the four Ubuntu elements was derived via the content analysis. Next, the procedure involved for developing the theoretical scale of Ubuntu with implementation of a Delphi study method in stage 2 is provided.

The design of a multidimensional scale for measuring Ubuntu elements

Approaches proposed by Hinkin (1995) and King (2004) were next applied to design the Ubuntu questionnaire. Accordingly, Hinkin (1995), Sigger et al. (2010) and Strauss et al. (2016) recommend that scale development uses a theoretical definition of the phenomena of interest (Ubuntu four concepts), applying an established typology (management) to guide item generation. These authors further note that in the absence of sufficient theory to guide the development of a measure, an inductive approach should first be used based on a sample of participants who can provide descriptions of the phenomena principles. This has been applied in this research design in stages 1 and 2 already described. The resulting items are as follows:

Ubuntu - Survival (four items) - At this hotel …

… I believe that each employee should be willing to share (the little) they have with others as a way of brotherly care.

… it is common practice for employees to sacrifice their time for the good of other team members.

… I feel that sharing my difficulties (grief) with other colleagues makes me strong.

… my manager shares his or her burden during hard times (e.g. budget cuts, salary pay cuts, restructuring or change of top management) as part of a team.

Ubuntu - Respect and dignity (four items) - At this hotel …

… I feel that my manager treats me with utmost respect and dignity.

… my manager greets me whenever he or she sees me.

… my manager expects me to respect his or her decisions.

… my manager treats each staff member as if he or she was a member of a family.

Ubuntu - Group solidarity (six items) - At this hotel …

… I have a genuine backing (support) of my co-workers, such that they are willing to help me when I need it.

… I actively contribute to work goals that benefit a wider group particularly, where they are worse-off than me.

… I generally do trust my co-workers in matters of landing or extending a helping hand.

… I have to be alert or else someone is likely to take advantage of me.

… I do helpful things that will benefit me and the colleagues I know.

… when something unfortunate happens to me (e.g. loss of family member), my co-workers get together to help me out.

Ubuntu - Compassion (six items) - At this hotel …

… I see myself as part of a diverse work team rather than as individual from a different cultural background or nationality.

… I feel that all employees should stick together as a family no matter what sacrifices are required.

… I feel it is my duty to take care of my co-workers, even if I have to sacrifice what I want.

… being a valuable team player is more important to me than my personal identity.

… the well-being of my co-workers is important to me.

… it is important to me that I respect the decisions (e.g. how to serve the customer) made by my co-workers.

Ubuntu - Collectivism (six items) - At this hotel …

… I see myself as part of a diverse work team rather than as individual from a different cultural background or nationality.

… I feel that all employees should stick together as a family no matter what sacrifices are required.

… I feel it is my duty to take care of my co-workers, even if I have to sacrifice what I want.

… Being a valued team player is very important to me than my personal identity.

… The well-being of my co-workers is important to me.

… It is important to me that I respect the decisions (e.g. how to serve customers) made by my co-workers.

Contributions of the study

Defining Ubuntu in a manner that allows for its measurement has to date been limited to a focus on the Ubuntu four principles (compassion, survival, group solidarity and respect and dignity), ignoring the role of collectivism integral to each. This article firstly synthesises various concepts of Ubuntu by earlier academic studies creating a conceptual consolidation of past research. Then, following the lead of House et al. (2004), this article has argued that organisational productivity requirements by managers such as assuring service quality excellence should consider the positive implications of Ubuntu in the context of service management. Thirdly, this article highlights the critical role of acknowledging and encouraging collectivism in attaining an Ubuntu style business management. Finally, the proposed measurement scale provides researchers with a fresh perspective of what is relevant in a scale to measure the degree of Ubuntu adopted in management scenarios.

It is acknowledged that it may not be easy to implement Ubuntu as a management style as some of this research's participants noted that Ubuntu may be perceived as a culture that supports only a certain group of people, or that it may be difficult to implement an ancient wisdom like Ubuntu in a modern society. These issues aside many aspects of the discussion in this article highlight that Ubuntu has a role to play in service organisations especially those in South Africa.

Conclusion

The conclusion that can be drawn from this article is that the values of Ubuntu, compassion, survival, group solidarity, and respect and dignity including collectivism, if consciously harnessed can play a pivotal role in elevating team cohesion among frontline managers and employees. The most important message of this research is that Ubuntu values and its practices should be understood as an organisational resource that managers could use to trigger a positive and motivational atmosphere among employees. Hence, this article left room for future work to be conducted on the validity and reliability of the developed Ubuntu scales not only in the hospitality sector but other sectors as well.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express special thanks to the three South African hotel groups and four universities who gave us the golden opportunity to conduct this research at their organisations with the frontline managers and academic staff.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no financial support was received for this research.

Authors' contributions

T.M. completed this research as a PhD candidate at the University of Johannesburg, and also completed data collection, drafting of manuscript and the revisions. P.T. provided conceptual input, editing and final alteration of the manuscript. G.G. is a co-promoter for the PhD study of T.M. G.G. provided conceptual input to the manuscript and assisted with final alterations to the manuscript.

Ethical considerations

As this is part of the PhD study that begun in 2014, there were no ethical permit numbers required but an ethical clearance was confirmed by the department. The hotel groups granted the collection of data based on a non-disclosure agreement.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for this research.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Battle, M., 1996, 'The ubuntu theology of Desmond Tutu', in L. Hulley, L. Kretzchmar & L.L. Pato (eds.), Archbishop Tutu: Prophetic witness in South Africa, pp. 93-105, Human & Rousseau, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Broodryk, J., 2002, Ubuntu: Life lessons from Africa, Ubuntu School of Philosophy, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Broodryk, J., 2005, Ubuntu: Life lessons from Africa, Ubuntu School of Philosophy, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Brotherton, B. & Wood, R.C., 2008, The nature and meaning of hospitality: The Sage handbook of hospitality management, British Library, London. [ Links ]

Browning, V., 2006, 'The relationship between HRM practices and service behaviour in South African service organizations', International Journal of Human Resource Management 17(7), 1321-1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190600756863 [ Links ]

Brubaker, T.A., 2013, 'Servant leadership, Ubuntu, and leader effectiveness in Rwanda', Emerging Leadership Journeys 6(1), 114-147. [ Links ]

Coughlan, L., Moolman, H. & Haarhoff, R., 2014, 'External job satisfaction factors improving the overall job satisfaction of selected five-star hotel employees', South African Journal of Business Management 45(2), 97-17. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v45i2.127 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 1994, Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2009, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches, 3rd edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Dandala, M., 1996, 'Cows never die: Embracing African cosmology in the process of economic growth', in R. Lessem & B. Nussbaum (eds.), Sawubona Africa: Embracing Four Worlds in South African Management, pp. 69-85, Zebra Press, Sandton. [ Links ]

Esterberg, K.G., 2002, Qualitative methods in social research, McGraw Hill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Gay, L.R. & Airasian, P., 2000, Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application, 6th edn., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Guba, E.G., 1990, 'The alternative paradigm dialogue', in E.G. Guba (ed.), The paradigm dialogue, pp. 17-30, Sage, Newbury Park, CA. [ Links ]

Gustafson, D.H., Shukla, R.K., Delbecq, A. & Walster, G.W., 1973, 'A comparison study of differences in subjective likelihood estimates made by individuals, interacting groups, Delphi groups and nominal groups', Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 9(2), 280-291. [ Links ]

Hasson, F., Keeney, S. & McKenna, H., 2000, 'Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique', Journal of Advanced Nursing 32(4), 1008-1015. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x [ Links ]

Hinkin, T.R., 1995, 'A review of scale development practices in the study of organisations', Journal of Management 21(5), 976-988. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639502100509 [ Links ]

Hofstede, G., 1983, 'The cultural relativity of organisational practices and theories', Journal of International Business Studies 14(2), 75-89. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jib [ Links ]

House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W. & Gupta, V., 2004, Culture, leadership and organisations: The Globe study of 62 societies, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Jones, J. & Hunter, D., 1995, 'Consensus methods for medical and health services research', BMJ 311(7001), 376-380. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376 [ Links ]

Kamwangalu, N., 1999, 'Ubuntu in South Africa: A sociolinguistic perspective to a Pan African concept', Critical Arts 13(2), 24-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560049985310111 [ Links ]

Karsten, L. & Illa, H., 2005, 'Ubuntu as a key African management concept: Contextual background and practical insights for knowledge application', Journal of Managerial Psychology 20(7), 607-620. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940510623416 [ Links ]

Khoza, R.J., 1994, The need for an Afrocentric approach to management, African Management, Knowledge Resources (PTY) Ltd, Randburg, pp. 117-123. [ Links ]

Khoza, R.J., 2005, Let Africa lead, Vezubuntu, Sunninghill. [ Links ]

King, N., 2004, 'Using interviews in qualitative research', in C. Cassell & G. Symon (eds.), Qualitative methods in organizational research, pp. 257-270, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R.S., 1991, Emotions and adaption, Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 2002, Power sharing and the challenge of Ubuntu ethics, viewed 30 April 2017, from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/4316/Louw.pdf? [ Links ]

Lutz, D.W., 2009, 'African Ubuntu philosophy and philosophy of global management', Journal of Business Ethics 84(Suppl 3), 313-328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0204-z [ Links ]

Mabovula, N.N., 2011, 'The erosion of African communal values: A reappraisal of the African Ubuntu philosophy, Inkanyiso', Journal of Human & Social Science 3(1), 38-47. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijhss.v3i1.69506 [ Links ]

MacDonald, P., Kelly, S. & Scott Christen, S., 2014, 'A path model of workplace solidarity, satisfaction, burnout, and motivation', International Journal of Business Communication 56(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414525467 [ Links ]

Mangaliso, M.P., 2001, 'Building a competitive advantage from ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa', The Academy of Management Executive 15(3), 23-33. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001.5229453 [ Links ]

Mbhele, N., 2015, 'Ubuntu and school leadership: Perspectives of teachers from two schools at Umbumbulu circuit', Unpublished masters dissertation, School of Education, University of Kwazulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Mbigi, L., 1997, Ubuntu: The African dream in management, Knowledge Resources, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mbigi, L., 2000, In search of the African business renaissance: An African cultural perspective, Knowledge Resources, Randburg. [ Links ]

Mbigi, L. & Maree, J., 1995, The spirit of African transformation management, Sigma, Pretoria. [ Links ]

McAllister, P., 2009, 'Ubuntu - Beyond belief in Southern Africa', Sites: New Series 6(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.11157/sites-vol6iss1id94 [ Links ]

Metz, T. 2008, 'Towards an African moral theory', Journal of Political Philosophy 15(3), 321-348. [ Links ]

Msila, V., 2008, 'Ubuntu and school leadership', Journal of Education 44(1), 67-84. [ Links ]

Mthembu, D., 1996, 'African values: Discovering indigenous roots of management', in R. Lessem & B. Nussbaum (eds.), Sawubona Africa: Embracing Four Worlds in South African Management, pp. 215-226, Zebra Press, Sandton. [ Links ]

Muchiri, M.K., 2011, 'Leadership in context: A review and research agenda for sub-Saharan Africa', Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 84(3), 440-452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02018.x [ Links ]

Nambisan, S., Agarwal, R. & Tanniru, M., 1999, 'Organisational mechanisms for enhancing user innovation in information technology', MIS Quarterly 23(8), 365-395. https://doi.org/10.2307/249468 [ Links ]

Ndaba, W.J., 1994, Ubuntu in comparison to western philosophies, Ubuntu School of Philosophy, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Neuman, W.L., 2006, Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, 6th edn., Pearson Education Inc., New York. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, B., 2003, 'Ubuntu: Reflections of a South African on our common humanity', Reflections 4(4), 21-26. https://doi.org/10.1162/152417303322004175 [ Links ]

Okoli, C. & Pawlowski, S.D., 2004, 'The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications', Information & Management 42(1), 15-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [ Links ]

Oppenheim, C.E., 2012, 'Nelson Mandela and the power of Ubuntu', Religions 3, 369-388. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3020369 [ Links ]

Poovan, N., Du Toit, M.K. & Engelbrecht, A.S., 2006, 'The effect of the social values of Ubuntu on team effectiveness', South African Journal of Business Management 37(3), 17-27. [ Links ]

Qobo, M. & Nyathi, N., 2016, 'Ubuntu, public policy ethics and tensions in South Africa's foreign policy', South African Journal of International Affairs 23(4), 421-436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1298052 [ Links ]

Richardson, R.N., 2008, 'Reflections on reconciliation and ubuntu', in R. Nicholson (ed.), Persons in community: African ethics in a global culture, pp. 65-83, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Rodwell, M.K., 1998, Social work, constructivist research, Garland Publishing, London. [ Links ]

Sigger, D.S., Polak, B.M. & Pennink, B.J.W., 2010, '"Ubuntu" or "humanness" as a management concept', pp. 11-95, CDS Research Report 29, ISSN 1385-9218, [ Links ]

Smith, W.G., 2017, 'A postfoundational Ubuntu accepts the unwelcomed (by way of "process" transversatility)', Verbum et Ecclesia 38(3), a1556. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v3813.1556 [ Links ]

Sono, T., 1994, Dilemmas of African intellectuals in South Africa, Unisa Press, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Strauss, C., Taylor, B.L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F. et al., 2016, 'What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures', Clinical Psychology Review 47(2016), 15-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004 [ Links ]

Tavernaro-Haidarian, L., 2018, 'Evolving "discourse" into discourse: Ubuntu as a normative basis', South African Journal of Communication Theory and Research 44(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2017.1415945 [ Links ]

Theletsane, K.I., 2012, 'Ubuntu management approach and service delivery', Journal of Public Administration 47(1:1), 209-426. [ Links ]

The National Department of Tourism, 2011, The National Tourism Service excellence strategy, Republic of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Tutu, D., 2004, God has a dream: A vision of hope for our time, Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

Tutu, D., 1995, 'Nothing short of a miracle', in C. Thick (ed.), The right to hope: Global problems, global visions: Creative responses to our world in need, pp. 94, Earthscan Publications, University of Michigan, viewed 21 June 2019, from https://books.google.co.za/books?id=zoyfAAAAMAAJ. ISBN 9781853833090 [ Links ]

Van Dun, D.H., Celeste, P.M. & Wilderom, C.P.M., 2016, 'Lean-team effectiveness through leader values and members' informing', International Journal of Operations & Production Management 36(11), 1530-1550. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-06-2015-0338 [ Links ]

Westmoreland, M.W., 2008, 'Interruptions: Derrida and hospitality', Kritike 2(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.25138/2.1.a.1 [ Links ]

Woermann, M. & Engelbrecht, S., 2019, 'The Ubuntu challenge to business: From stakeholder to relation holders', Journal of Business Ethics 157(1), 27-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3680-6, [ Links ]

Yukl, G., 2002, Leadership in organisations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Thembisile Molose

moloset@cput.ac.za

Received: 16 July 2018

Accepted: 28 Mar. 2019

Published: 26 Aug. 2019