Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Commercii

versão On-line ISSN 1684-1999

versão impressa ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.18 no.1 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v18i1.533

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Managers' listening skills, feedback skills and ability to deal with interference: A subordinate perspective

Mpumelelo Longweni; Japie Kroon

WorkWell: Research Unit for Economic and Management Sciences, North-West University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Active listening is the single most important contributor to effective communication by managers; however, this is the skill they seem to struggle with the most. Other important skills for effective communication include feedback and the ability to deal with interference

RESEARCH PURPOSE: This study's primary objective was to determine the effectiveness of managers' listening and feedback skills and their ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases of the communication process as perceived by subordinates with varying educational backgrounds

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: The aim was to improve managers' communication with their subordinates.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: The research followed a quantitative descriptive design. A self-administered questionnaire was compiled, a non-probability convenience sample was chosen and 931 usable responses were acquired.

MAIN FINDINGS: The results showed that subordinates perceived their managers' communication competencies to be marginally above average. Managers' listening and feedback skills were perceived to be better by graduate-level subordinates than by those with only a Grade 12 qualification. Subordinates with a postgraduate degree also had better perceptions of these skills than those with a Grade 12 qualification, although this finding was not statistically significant

PRACTICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Managers need to be aware that their communication competencies are crucial to their business's success. Additionally, their subordinates' perception of the effectiveness of their communication varies according to varying educational levels. Therefore, managers are advised to consciously make greater efforts in their communication with subordinates with lower qualifications.

CONTRIBUTION OR VALUE-ADD: In conclusion, this article will make managers more knowledgeable about potential challenges they may encounter during the communication process regarding listening skills, feedback skills and propensity to deal with interference.

Introduction

Modern businesses are faced with an onslaught of constant change and steep competition, wherein managers and subordinates are the primary sources of competitive advantage, which is predominantly achieved by ways of communication (Brunetto & Farr-Wharton 2004:594; Longenecker 2010:39). Other crucial managerial competencies include: teamwork, interpersonal relations, self-management, decision-making, networking, analytical skills, global awareness and strategic action, awareness of self and others, and creative problem-solving (Daft & Marcic 2014:13; Dogra 2012). According to Heyns and Luke (2012:113), effective communication is one of the most important competencies required for sustainable business success.

Communication is the social action that involves the transfer and exchange of information, opinions, plans and ideas among individuals or groups to motivate action, influence behaviour and entice responses (Henrico & Visser 2012:183; Kupritz & Cowell 2011:58). Businesses that exhibit effective communication have higher levels of productivity, increased returns and better employee engagement (Mishra, Boynton & Mishra 2014:190-191; Yates 2006:2). Ineffective communication among managers and subordinates significantly hampers a business's ability to achieve its objectives (Arvidsson 2010:350). An effective communication process involves active and empathetic listening and providing and receiving feedback (Daft & Marcic 2009:552).

In general, effective listening involves paying close attention to both the message and the manner in which it is conveyed, and it is crucial for managerial success (Mishra et al. 2014:196). Feedback, in general, is essentially evidence that enables persons or groups to compare actual performance with a specified standard or expectation that inspires improvement, growth and development (De Janasz, Dowd & Schneider 2009:392).

The comprehensive communication process is plagued by interference, that is: semantic barriers such as professional jargon and regional colloquialisms, physical barriers such as literal background noise, psychological barriers such as attitude, and physiological barriers such as discomfort (Brown 2001:27; Krauss 2002:654; Lunenburg 2011:10; Truter 2006:57). Sufficient knowledge on the part of managers about interference, how to deal with it and the contributing barriers to listening and feedback enables them to promote effective communication within businesses (Truter 2006:55-58).

Problem statement and the research question

Owing to the way that businesses function, there are many important managerial competencies; however, Heyns and Luke (2012:113) argue that communication is the most essential. In an ever-changing business environment with subsiding corporate loyalty, managers with exceptional communication skills such as listening, feedback and ability to deal with interference during these two stages are pivotal to the sharing of information, altering of behaviour and promoting subordinate commitment to a business (Brunetto & Farr-Wharton 2004:594). Knowledge of the opinions of subordinates concerning this process is important because problems like ineffective communication practices, mistakenly altered messages and misconstrued transmission can be linked to managers with overly positive opinions of their communication skills (Johnson 2013).

Differences in levels of education and training can be linked to different employee perceptions regarding the communication process between themselves and their managers (Gondlekar & Kamat 2016:193,195; Hailu, Kassahun & Kerie 2016). Subordinates with higher education levels can be associated with higher levels of satisfaction with the communication capabilities of their managers (Erdil & Tanova 2015:187), who, when considering these differences in educational levels, will be able to function more effectively as communicators (Tschannen & Lee 2012).

Listening plays a crucial role in the communication process and can significantly enhance interpersonal relationships in a business. When managers listen actively, subordinates tend to feel more supported, engaged and committed to them and the business (Mishra et al. 2014:196; Trees 2000:259). Managers who can listen while paying attention to the needs, problems and suggestions of subordinates are better able to achieve business objectives and utilise lucrative opportunities by easily gaining information regarding defects (Canary, Cody & Manusov 2008:111, Daft & Marcic 2009:573).

Feedback during the communication process is equally important because the most advantageous performance of a business is reliant on, not only managers and subordinates giving and receiving feedback, but its integration into their tasks as well (De Janasz et al. 2009:384). Unless managers promote an organisational culture of effective, constructive and collaborative feedback, they will be unable to alter dwindling subordinate performance positively (De Janasz et al. 2009:392; Jones & George 2013:418-419; Longenecker 2010:34). Despite the importance of feedback, most managers and subordinates are reluctant to provide or request it (De Janasz et al. 2009:393).

Successful listening and feedback exercises are accompanied by the effective handling of interference. A deficient ability to deal with interference during these processes hinders team cohesion and clarity of instructions among managers and subordinates (Schreiner 2014; Travis 2016).

The research question for this study was: How do subordinates with varying educational backgrounds perceive the effectiveness of their managers' listening skills, feedback skills and ability to deal with interference during listening and feedback?

Objectives and hypotheses

Stemming from the above, the primary purpose of the study reported on in this article was to investigate how subordinates from various educational backgrounds perceive their managers' listening skills, feedback skills and ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases in the communication process.

To achieve the purpose of this article, the objectives were to:

· compile a demographic profile of respondents who took part in the study;

· investigate managers' listening skills in the communication process as perceived by their subordinates;

· explore managers' feedback skills in the communication process as perceived by their subordinates;

· investigate managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback stages of the communication process as perceived by their subordinates;

· determine whether statistical differences exist between the perceptions of subordinates from various educational backgrounds regarding their managers' listening skills;

· establish whether statistical differences exist between the perceptions of subordinates from various educational backgrounds regarding their managers' feedback skills;

· determine whether statistical differences exist between the perceptions of subordinates from various educational backgrounds regarding their managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases;

· determine the practical significance of the differences.

The following alternative hypotheses were formulated for this research:

Ha1: There is a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' listening skills during the communication process.

Ha2: There is a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' feedback skills during the communication process.

Ha3: There is a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback stages of the communication process.

Conceptual framework

A conceptual framework, derived from various sources (Colquit, Lepine & Wesson 2013:393; Daft & Marcic 2009:552; Erdil & Tanova 2015:187; Henrico & Visser 2012:183; Jones & George 2013:417; Locker & Kaczmarek 2014:4; Trenholm & Jensen 2013:14; Tschannen & Lee 2012) was compiled to guide this study.

Literature review

The various concepts in the conceptual framework will be discussed.

Subordinates

For the purpose of the current study, subordinates from three main industries were divided into three groups based on their highest educational achievement. As indicated in the conceptual framework, subordinates play an important role in the communication process between themselves and managers. They start the communication process by encoding the message and then sending it to the managers via appropriate communication channels, with possible interference occurring anywhere in this process (Jones & George 2013:417). Subordinates' communication competencies are critical to productivity; they have to encode information-carrying messages correctly, alter unsatisfactory behaviour when given feedback and report progress and defects to managers (Colquit et al. 2013:392-393; Holm 2006:498).

Education and training

Well-educated and sufficiently trained employees are conducive to the success of a business (Al-Adwani 2014:137). According to Daoanis (2012:48), education and training in communication are included among the most important skills a subordinate should have in a business. Differences in level of education and training can be linked to different employee perceptions of aspects of communication. Gondlekar and Kamat (2016:193, 195) found that employees with postgraduate degrees had reached significantly higher levels of personal growth and development within businesses than those with only a matric qualification. Employees with higher levels of education were also found to have higher perceived levels of respect and satisfaction within the business as well as regarding the effectiveness of their managers' communication competencies (Erdil & Tanova 2015:187; Hailu et al. 2016). It can be concluded that managers who consider the educational levels of subordinates can promote effective communication (Tschannen & Lee 2012).

Managers

Managers play an important part in the success of a business, as they influence business performance (Lubatkin et al. 2006:668). As depicted in Figure 1, managers are the receivers of the messages during the first communication phase, where they fulfil the role of listeners. To be effective listeners, the managers need to withhold judgement, be attentive and refrain from formulating and rehearsing responses (Dixon & O'Hara 2010). During the feedback phase of the communication process, the roles of managers and subordinates are reversed.

Managerial competencies

Oosthuizen (2011:66) describes managerial competencies as a set of skills, knowledge, attitudes and behaviour that a manager needs to be successful in a variety of organisational settings and managerial jobs. Effective communication is imperative in business because it affects how managers and subordinates execute their tasks, as well as the quality of their execution (Henrico & Visser 2012:185-186).

The communication process

As depicted in the conceptual framework (Figure 1), the communication process consists of two distinguishable phases. These phases are usually named the 'transmission phase' and the 'feedback phase' (Daft & Marcic 2009:552). During the transmission phase, information is shared between two or more individuals or groups. For the purpose of this study, the transmission phase is referred to as the 'listening phase', because the subordinate encodes messages and the manager listens during this phase. In the feedback phase, a mutual understanding arises through cognitive actions and active listening (Daft & Marcic 2009:552-553). This phase can also be used to confirm comprehension, instruct and motivate subordinates, or request more information. These messages are sent and received via a medium (also referred to as a 'channel'), which is the pathway by which an encoded message is transmitted to a receiver (Dixon & O'Hara 2010).

Listening

Listening can be referred to as the act of consciously paying attention to not only the message but also the manner in which the message is being conveyed, such as the use of language, voice, tone and body language of the speaker (Certo 2014; Pelham 2006:180). Effective managers are active listeners who are engaged and invested in the outcome of the interaction (De Janasz et al. 2009:128). To be truly effective listeners, managers are advised to be supportive and genuinely concerned about the feelings of their subordinates during the communication process through empathetic listening (Henrico & Visser 2012:185).

As indicated in the problem statement, listening is a crucial element of the communication process. Listening skills are significantly more important than speaking for managerial success, business performance and effective communication (Flynn, Valikoski & Grau 2008:148; Fracaro 2001:3). Burley-Allen (2005:2) states that a significant portion (40%) of the communication process is made up of listening, yet despite this frequency communicators may not actually grasp the impact that effective and ineffective listening have on interpersonal interactions (Bambacas & Patrickson 2008:67). Managers who are effective listeners connect with subordinates, which, in turn, may result in those managers being perceived as leaders to be followed by choice (Canary et al. 2008:111). Subordinates also perceive managers who actively and attentively listen as being more competent communicators, which increases the likelihood of achieving interpersonal objectives. Managers gain insights into complex problems and solutions and are better able to provide valuable feedback (Canary et al. 2008:111; Trees 2000:259) when they listen attentively. Managers who are ineffective listeners are more likely to make mistakes, are generally less proficient at their managerial tasks and obstruct the flow of information (Pelham 2006:180). Insufficient listening skills may cause managers to squander potentially lucrative opportunities (French 2013; Johnson 2013).

According to Hartley and Bruckman (2002:20), managers can improve their listening skills by applying two steps: firstly, developing the aptitude to identify and deal with obstacles that prevent optimal listening and secondly cultivating and using behaviours that assist listening. Hoppe (2007:11-12) suggests a six-step model to assist managers to specifically improve their active listening: paying attention, withholding judgement, reflecting, clarifying, summarising and sharing. As the initial senders in the communication process, subordinates can smile, lean forward, maintain eye contact and arch their necks forward to increase the probability of their managers listening to them actively (Buck 2004:25).

Feedback

Feedback can be regarded as providing information relating to the performance of the receiver with the goal to improve performance (Dai, De Meuse & Peterson 2010:213; Dobbelaer, Prins & van Dongen 2013:99). During the feedback phase of the communication process, the message could also consist of validation that the first message was comprehended, reiterate the first message to ensure an accurate interpretation or request additional information (Jones & George 2013:416-417). Managers and subordinates provide and seek feedback with the intention of confirming, adding to, overwriting or restructuring received information (Ragusa 2011:21). Feedback enables subordinates to determine whether they have been successful in transmitting their message. Naturally, it also assists managers to evaluate peers and subordinates according to predetermined, preset standards, expectations and norms (Daft & Marcic 2009:573).

The importance of feedback was discussed in the problem statement. Feedback is mentally reassuring and usually leads to improved performance and growth (De Janasz et al. 2009:392; Kobeleva & Strongman 2011:98). Modern managers are usually preoccupied with their strategic responsibilities, effectively removing them from the ground-level, day-to-day operations of the businesses. This causes a rift between managers and subordinates and makes it more challenging to provide and receive effective feedback. This gap can only be bridged by fostering an effective feedback culture within a business (Jones & George 2013:418-419). Managers can only positively alter dwindling subordinate performance with effective feedback (Longenecker 2010:34). However, regardless of its importance, feedback is often neglected, and managers and subordinates find providing and requesting feedback to be inherently challenging (Daft & Marcic 2009:573). This could be because of the feedback provider's fear of the receiver's reaction, fear of insufficient tangible support of the feedback or fear of a potential rise in tension in the interpersonal relationship (Dixon & O'Hara 2010).

A prerequisite of effective feedback within the business context is established standards (Longenecker 2010:38). To provide effective feedback, managers are advised to be specific, provide the feedback face to face, be sensitive and offer solutions when providing negative feedback (Wertheim 2005). Daoanis (2012:49) recommends clear objectives and proper documentation as effective feedback practices that can serve as tangible support for the feedback and increase subordinate commitment and performance. Krasman (2011:24) found that having unambiguous goals and appropriate standards in place also increases the likelihood of feedback-seeking among managers and subordinates. Consistently seeking feedback demonstrates a subordinate's willingness to learn and leads to improved self-awareness. However, excessive feedback requests can lead to perceptions of incompetence and could indicate a lack of initiative (Van Rensburg & Prideaux 2006:566).

Interference

According to Brown (2001:27), interference is any obstruction to the effective exchange of thoughts, ideas or commands. Interference can, therefore, refer to anything that hinders the communication process, and it can occur during any phase of the communication process (Lunenburg 2011:4). A common example of interference within a business context is literal blare caused by clattering machinery during production (Colquit et al. 2013:393). There are many ways for a message to get misinterpreted, distorted, misunderstood or confused during the listening and feedback phase. The barriers that stand out the most during the listening phase of the communication process are: jumping to conclusions, hearing what one wants to hear, formulating and rehearsing responses, being inattentive (that is, thinking about other matters), judging the sender, having a closed mind, feeling anxious or self-conscious and excessive interrupting (Dixon & O'Hara 2010). During the feedback phase, fearing tension, receiver reaction and lack of concrete substantiation can be sources of barriers (Dixon & O'Hara 2010).

Having sufficient knowledge about interference and the contributing barriers to listening and feedback enables managers to deal with it better and promotes effective communication (Truter 2006:1-3). It can be concluded that the most effective way of dealing with interference is by being knowledgeable about it and actively trying to minimise its impact on the communication process (Erven 2012; Pfeiffer 1998)

Research methodology

Research design

A survey was employed to conduct this quantitative, descriptive and exploratory study (Bradley 2007:516; Burns & Bush 2014:103; Struwig & Stead 2007:243).

Target population, sampling and data collection

The target population consisted of employees with at least a Grade 12 qualification from three major South African industries. There was no sample frame in this study (Singh 2007:88), and therefore fieldworkers used a list of employees at each business as a frame, which served as a substitute for a frame. A non-probability, convenience sampling method was followed, and to provide structure to the sampling process, fieldworkers were instructed to fulfil quotas where a third of the respondents came from the manufacturing industry, another third from the retail industry and the final third from the services industry. The sample included a total of 966 workers, of whom 931 submitted usable questionnaires. Twenty trained fieldworkers were used to distribute the self-administered questionnaires and collect them afterwards. The fieldworkers were BCom Honours students in the field of Business Management who had completed an undergraduate module in Marketing Research. The following numbers of usable questionnaires were retrieved from the various provinces, and the numbers of fieldworkers employed are indicated in brackets: Gauteng, 544 (12); KwaZulu-Natal, 48 (1); North West Province, 98 (2); Western Cape, 50 (1); Mpumalanga, 91 (2); Northern Cape, 49 (1); and Free State, 51 (1).

Measuring instrument

Subordinates' opinions and perceptions concerning their managers' communication competencies were obtained using a self-administered questionnaire (Struwig & Stead 2007:244). This questionnaire commenced with an introduction that stated the rights of the respondents, provided contact details of the researchers and indicated the purpose of the study. The questionnaire was based on indicators from some literature sources and consisted of two sections. Data regarding respondents' demographic profiles were gathered in Section A, which consisted of closed-ended questions, while Section B, which comprised a five-point Likert scale, measured three communication skills, namely listening, feedback and ability of managers to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases as perceived by their subordinates. All five response categories were not named; only the end points of the scales were labelled as 'strongly disagree' and 'strongly agree', respectively.

Data analysis and interpretation

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 21) and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS version 20) were used in this study to capture and analyse the data. A 5% level of significance was used as a criterion for all statistical tests. The following analyses were performed:

Frequency analyses were performed for all the items in the questionnaire and mean scores and standard deviations were computed.

The validity of the measuring instrument was examined by applying exploratory factor analysis as a validated questionnaire was not used. Next, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to confirm the validity of the constructs.

Cronbach's alpha coefficients were used to determine reliability.

Statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05) was determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (McDaniel & Gates 2013:455; Struwig & Stead 2007:162) and Cohen's d-value was used to assess practical significance. The following criteria were used to interpret practical significance: d = 0.2 - small effect (negligible); d = 0.5 - medium effect (substantial); and d = 0.8 - large effect (definitive) (Ellis & Steyn 2003:51-52; Steyn 1999:3).

Ethical considerations

WorkWell Research Unit put the study under ethical review and deemed it to be of minimal risk. The clearance permit number obtained is EMS15/02/25-01/03.

Results and discussion

The findings from the primary data collection are discussed in this section. This section starts with a discussion of the psychometric characteristics of the measuring instrument. The remainder of the section will present the sample profile based on the demographic information gathered, followed by the results concerning the three constructs used in the empirical study, in correspondence with this study's objectives.

Psychometric properties of the measuring instrument

The researchers could not find a suitably validated questionnaire; subsequently, the compiled questionnaire was tested for construct and content validity as well as for reliability. This article forms part of a larger study in which more aspects of communication were investigated. The measuring instrument for the entire study was validated, and the findings are provided below.

Construct validity

An exploratory factor analysis was executed to determine valid constructs. Bartlett's test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy were used to test whether the data were suitable for factor analysis. The KMO statistic generally varies between 0 and 1; the KMO should be 0.50 or higher for a satisfactory factor analysis. In this study, the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.950. Bartlett's test of sphericity tests the null hypothesis that the original correlation matrix is an identity matrix, which would indicate that the variables are unrelated. The associated Bartlett's test of sphericity for the current study was found to be statistically significant in all cases.

A principal component analysis technique was used to extract factors from the data, which best describe the underlying relationships among the variables. Eigenvalues exceeding 1.0 with loads of 0.30 were used for inclusion of items in the exploratory factor analysis. An oblimin with the Kaiser normalisation technique was applied. Five factors, representing 51.79% of the variance explained in the data, were extracted. For the purpose of this article, only three of the five factors will be discussed.

The above analysis was followed by a CFA. The chi-square minimum discrepancy (CMIN) divided by degrees of freedom (DF) function was used to calculate the goodness of fit in AMOS. The goodness of fit is acceptable if CMIN/DF is between 2 and 5 (Arbuckle 2003:77-85). In this study, the goodness of fit was acceptable (CMIN/DF = 2.929). Additionally, a model is regarded as acceptable and valid in a CFA if the following conditions are met:

· The comparative fit index (CFI) is 0.93 or greater (Byrne 2001:79-88); in this study, the CFI was 0.929.

· The root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) is appropriate. Ideally, the RMSEA should be less than 0.05 (Steiger 1990:177); in this study, the RMSEA was 0.046.

Additionally, in manual calculations outside of AMOS, the following was found:

· All factor loadings were found to indicate good convergent validity and varied between 0.486 and 0.704 (as 0.486 is close enough to 0.50, it is acceptable).

· However, considering that the rule of thumb is that an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.50 and higher is required and that the AVEs for this article ranged between 0.349 and 0.414, convergent validity cannot be sufficiently argued. Because CFA is a theory-driven method, none of the items that made up the factors was removed.

· There was also no empirical evidence of discriminate validity because the AVEs did not meet the requirements for maximum shared variance, with squared correlations ranging from 0.653 to 0.771.

· Lastly, score reliability is also a requirement for construct validity. Therefore, strong composite reliability values that range from 0.680 to 0.846 vindicate the internal consistency of the scales used in this article.

Consequently, the researchers believe that the instrument can be seen as construct valid.

Content validity

According to Delport and Roestenburg (2011:173), content validity is concerned with the extent to which a measuring instrument covers the whole content domain. The items in each scale of the measuring instrument must consequently be representative of the conceptual definition under discussion and must measure the concept that the researcher intends to measure.

In this study, content validity was verified by knowledgeable study leaders and supervisors from the School of Business Management at the North-West University's Potchefstroom campus, who all found the instrument to be content valid.

Reliability

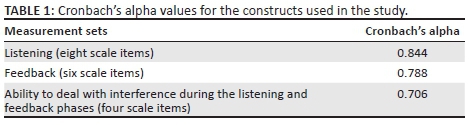

The researchers computed the Cronbach's alpha coefficients to establish the statistical reliability of the constructs. Zikmund and Babin (2015:280) state that a Cronbach's alpha value between 0.60 and 0.70 indicates fair reliability, a value between 0.70 and 0.80 indicates good reliability and a value between 0.80 and 0.96 indicates excellent reliability. Scales with a Cronbach's alpha value below 0.60 indicate poor reliability.

Table 1 depicts the reliability testing conducted in this study.

It is evident from Table 1 that all the constructs have good reliability.

Results of the empirical study

The results will be presented in line with the objectives. The demographic profile of the respondents is presented first, followed by specific findings regarding managers' listening skills, feedback skills and ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases.

Sample profile

Nearly an equal number of males and females took part in this study, the majority of whom had a Grade 12 qualification (50.2%), followed by approximately one-third who had obtained a diploma or degree. Lastly, only 123 of the subordinates had obtained a postgraduate degree. Only 337 (36.2%) of the respondents had completed a course to improve their own communication skills. The average age of the respondents was 33 years old.

Managers' listening skills as perceived by their subordinates

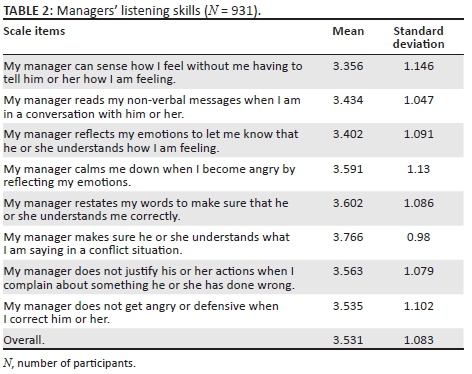

Table 2 depicts the mean scores and standard deviations of the items measuring managers' perceived listening skills on a five-point Likert scale.

Regarding their managers' listening skills, subordinates agreed most with the statement, 'My manager makes sure he or she understands what I am saying in a conflict situation'. According to Cohen (2014:139), people generally listen poorly during situations of conflict. Managers who can listen effectively under these conditions promote the solving of problems and the resolution of the conflict. However, subordinates had a less positive perception about their managers' aptitude to read their emotions during conversations. Employee engagement, commitment to production quality as well as an understanding of business issues decline when managers fail to read subordinates' emotions during the listening phase of the communication process (Mishra et al. 2014:196). The overall relatively positive mean score for managers' listening skills as perceived by their subordinates was 3.531 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.083).

Managers' feedback skills as perceived by their subordinates

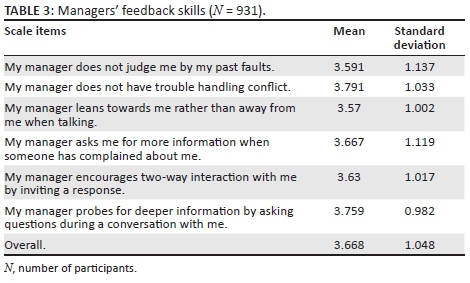

Table 3 depicts the mean scores and standard deviations regarding managers' feedback skills on a five-point Likert scale.

The statement 'My manager does not have trouble handling conflict' had the highest mean score of 3.79 (SD = 1.033). Managers who appropriately handle conflict during the feedback phase of the communication process take steps towards improving their overall communication competencies and can identify and consolidate sources of deficiencies and make the necessary amendments to reward systems (Jiang et al. 2014:101). Non-verbal feedback, such as leaning forward, is deemed to be very credible and can increase the likelihood of active listening among subordinates during the feedback phase (Buck 2004:25; Trenholm & Jensen 2013:50). However, in this study, the gesture of leaning forward so as to show interest had a lower score of 3.57 (SD = 1.002). Managers can improve their feedback skills by addressing this behaviour specifically. The overall mean score for the respondents' perceptions of how well managers provide feedback was 3.668 (SD = 1.048), pointing out that respondents perceived managers' overall feedback skills to be slightly above average.

Managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases as perceived by their subordinates

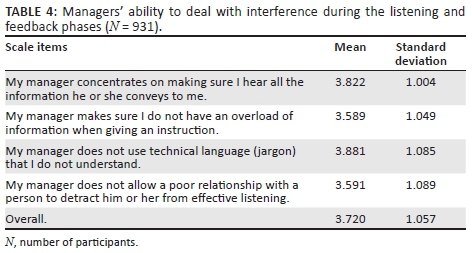

Table 4 provides insight into the mean and standard deviation scores of the items measuring managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases.

The overall mean score for managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases was a positive 3.720 (SD = 1.057). It can be concluded that subordinates generally agreed with the items within this construct. 'My manager does not use technical language (jargon) that I do not understand' was the statement subordinates agreed with most. When managers avoid the unnecessary use of technical jargon, it improves relationships between managers and their subordinates, enhances the effectiveness of the communication process and increases productivity (Patoko & Yazdanifard 2014:570). On the opposite side of the spectrum, subordinates agreed equally less with the statements 'My manager makes sure I do not have an overload of information when giving an instruction', which might lead to a loss of the intended purpose of the communication (Daft & Marcic 2009:552), and 'My manager does not allow a poor relationship with a person to detract him/her from effective listening', which may result in subordinates being more hesitant to report problems they may have experienced in the execution of their duties (Jones & George 2013:418-419).

Comparisons, statistical and practical significance

The following section compares the perceptions of subordinates with three different educational levels regarding managers' listening skills, feedback skills and their ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases.

Statistical differences between the perceptions of subordinates with various levels of education regarding three aspects of communication

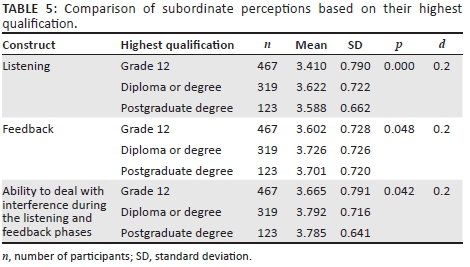

Analysis of variance was used to determine statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05), and Cohen's d-values (d ≥ 0.5) were used to determine practically significant differences between the perception of subordinates regarding their managers' listening skills, feedback skills and their ability to deal with interference during the above-mentioned communication processes based on their highest level of education. The findings are summarised in Table 5.

Regarding listening skills, there was a statistically significant difference (p = 0.000) between the perceptions of subordinates with varying educational levels (Grade 12 mean = 3.410, SD = 0.790; diploma or degree mean = 3.622, SD = 0.722; postgraduate degree mean = 3.588, SD = 0.662) in terms of how they perceived this skill.

In further conducting post hoc tests, it was found that subordinates with Grade 12 and those with a diploma or degree (Tukey's honest significant difference [HSD] at Sig. = 0.000/p = 0.000 and Games-Howell at Sig. = 0.000/p = 0.000) had statistically differing perceptions. Respondents with a diploma or degree (mean = 3.622) perceived their managers' listening skills to be slightly better than those with Grade 12 (mean = 3.410) did. However, Cohen's effect size (d = 0.2) suggests little practical significance.

With regard to managers' feedback skills, there was a statistically significant difference (p = 0.049) between the perceptions of subordinates with varying educational levels (Grade 12 mean = 3.602, SD = 0.728, diploma or degree mean = 3.726, SD = 0.726; postgraduate degree mean = 3.701, SD = 0.720) during the communication process.

In further conducting post hoc tests, it was found that subordinates with Grade 12 and those with a diploma or degree (Tukey HSD at Sig. = 0.048/p = 0.048 and Games-Howell at Sig. = 0.049/p = 0.049) had statistically differing perceptions. Subordinates with a diploma or degree (mean = 3.726) had a slightly better perception of their managers' feedback skills than respondents with Grade 12 (mean = 3.602) did. However, Cohen's effect size (d = 0.2) suggests negligible practical significance.

Regarding ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases, there was a statistically significant difference (p = 0.042) between the perceptions of subordinates from different educational levels (Grade 12 mean = 3.665, SD = 0.791; diploma or degree mean = 3.792, SD = 0.716; postgraduate degree mean = 3.785, SD = 0.641) regarding how subordinates perceived their managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases during the communication process.

However, the Tukey HSD and Games-Howell post hoc tests yielded no specific group differences, and Cohen's effect size (d = 0.2) suggested negligible practical significance.

Similarly, Tschannen and Lee (2012) and Erdil and Tanova (2015:187) found that higher levels of education were associated with better perceptions of communication skills. The findings of this study, however, are specific to the three aspects of effective communication under discussion. Furthermore, regarding listening and feedback, the statistically significant differences were only between subordinates with Grade 12 and those with a diploma or degree, whereas from the mean scores it can be concluded that the perceptions of subordinates with postgraduate degrees slightly declined. In this study, the increased educational level, from first degree to a postgraduate degree did not seem to improve the respondents' perception of their managers' listening or feedback skills or ability to deal with interference. The researchers believe that the relatively small number of respondents (p. 123) involved may have contributed to this finding. It should be noted, however, that the mean scores for the perceptions of subordinates with postgraduate degrees were higher than those of subordinates with only a Grade 12 qualification.

Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis 1

Regarding hypothesis 1, stating that there is a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' listening skills during the communication process, the following was found:

There was a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' listening skills during the communication process.

In post hoc tests, it was found that employees with a Grade 12 qualification and those with a diploma or degree had statistically significant different perceptions, where subordinates with a diploma or degree perceived their managers' listening skills to be slightly better than those with only a matric qualification. The perceptions of respondents with a postgraduate degree did not differ statistically significantly from those with the other two levels of education.

Consequently, Ha1 is accepted regarding statistically significant differences between the perceptions of subordinates with Grade 12 and those with a graduate qualification concerning managers' listening skills.

Hypothesis 2

Regarding hypothesis 2, stating that there is a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' feedback skills during the communication process, the following was found:

There was a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' feedback skills during the communication process.

In post hoc tests, it was found that employees with a Grade 12 qualification and those with a diploma or degree had statistically significant different perceptions, where subordinates with a diploma or degree perceived their managers' feedback skills to be slightly better than those with only a graduate qualification did. The perceptions of respondents with a postgraduate degree did not differ statistically significantly from those with the other two levels of education regarding managers' feedback skills.

Consequently, Ha2 is accepted regarding statistically significant differences between the perceptions of Grade 12 and graduate-level subordinates concerning managers' feedback skills.

Hypothesis 3

Regarding hypothesis 3, stating that there is a statistically significant difference on how subordinates with different education levels perceived their managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases of the communication process, the following were found:

There was a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels regarding their managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases of the communication process.

However, in the post hoc tests, no statistically significant differences could be identified between perceptions of subordinates regarding managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback stages of communication.

Consequently, Ha3 is accepted regarding the existence of statistically significant differences between the perceptions of Grade 12, graduate-level and postgraduate-level subordinates concerning managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases, without having been able to determine the educational levels wherein these differences occur.

Recommendations

Recommendations are first made from the results of the current study, followed by general recommendations from literature sources. The results showed that managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases was perceived by subordinates to be most effective of the three communication skills, followed closely by their feedback skills and then listening skills.

Managers can still improve on their ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases by refraining from information overload when giving instruction and by not allowing poor relationships with subordinates to diminish their effective listening.

Managers are also advised to add credibility to their message by paying more attention to exhibiting non-verbal cues, such as leaning forward during the feedback phase of the communication process. Showing interest by leaning forward might also entice active listening by subordinates.

Even though subordinates had relatively positive perceptions about their managers' listening capabilities, it proved to be the skill with the most room for improvement. The specific problem seemed to be managers' ability to sense how subordinates feel without having to be told how they feel. When managers effectively read their subordinates' emotions during the communication process, it will enhance employee engagement and commitment.

Furthermore, managers need to be aware that their communication is perceived differently by subordinates with varying educational backgrounds. Managers should consciously make greater efforts in their communication with subordinates with lower educational levels. To accomplish truly effective communication, particularly in the three aspects discussed in this paper, they ought to alter their behaviour appropriately.

Generally, seeing the entire communication as a process with distinct phases and elements assists managers to take the required steps towards becoming more effective communicators (Thill & Bovée 2013:50). According to various authors, listening is the most crucial skill to improve for overall effective communication (Flynn et al. 2008:148; Fracaro 2001:3; Griffen 2014:362). Regarding effective listening, some of the important behaviours that managers should practise during the listening phase of the communication process include withholding judgement, pondering on the initial message and clarifying vagueness (Hartley & Bruckman 2002:20; Hoppe 2007:11-12). Regarding effective feedback skills, it is recommended that managers have clear, unambiguous and acceptable preset standards and objectives that foster a commendable feedback culture among themselves and subordinates (Daoanis 2012:49; Krasman 2011:24; Longenecker 2010:38). Kupritz and Cowell (2011:4) suggest addressing the issue of information overload when dealing with interference during the listening and feedback phases by selecting an appropriate communication medium. In conclusion, the best way that managers can effectively deal with interference is by having knowledge about it (Erven 2012; Pfeiffer 1998).

Conclusions

This study was concerned with the importance of three aspects of effective communication between managers and subordinates, namely listening and feedback skills and ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases. The focus was specifically on the difference of perceptions of subordinates with varying educational qualifications. Figure 1 depicts the communication process as it concerns this study.

The following conclusions pertain to the empirical findings of this study and are presented in coordination with the objectives. Demographically, there were nearly equal numbers of male and female respondents with an average age of 33 years, the majority of whom had a Grade 12 qualification, followed by approximately one-third who had obtained a diploma or degree and only 123 of the subordinates who had obtained a postgraduate degree.

Subordinates at all the educational levels had relatively positive perceptions regarding their managers' listening skills, feedback skills and ability to deal with interference. Despite the importance of managers' listening skills, they were perceived to be the skills that managers are least effective in. Regarding the statistical differences between variables, it was found that there was a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational backgrounds regarding all three aspects of communication discussed in this study. Subordinates with a diploma or degree perceived their managers' listening skills to be marginally better than those with Grade 12 did. They also had a slightly better perception of their managers' feedback skills than respondents with Grade 12 had. Concerning managers' ability to deal with interference during the listening and feedback phases, it was found that subordinates with different educational levels had varying perceptions. However, no statistically significant differences were found between the perceptions of subordinates with different educational levels. Finally, judging by the mean scores, it seems that subordinates with a degree or diploma had a better perception of all the communication skills discussed in this study than those with a matric qualification, while postgraduates fell in between. Furthermore, these differences had negligible practical significance.

In conclusion, effective communication is the key to promoting and sustaining business success in a constantly changing business environment. If the managers of all businesses in a specific situation who have to communicate with subordinates implement the findings of this study, there is a greater likelihood that they will achieve their managerial goals and gain a competitive business advantage.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author contributions

M.L. is a Master of Commerce student at the North-West University. The second author, J.K., served as the supervisor for the study. This article was written and presented as the second one for the student's dissertation.

References

Al-Adwani, A.B., 2014, 'The extent to which human resources managers in KNPC believe in human resource investment', International Business Research 7(4), 132-141. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v7n4p132 [ Links ]

Arbuckle, J.L., 2003, Amos 5.0 update to the AMOS user's guide, Small Waters Corp., Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Arvidsson, S., 2010, 'Communication of corporate social responsibility: A study of the views of management teams in large companies', Journal of Business Ethics 96(3), 339-354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0469-2 [ Links ]

Bambacas, M. & Patrickson, M., 2008, 'Interpersonal communication skills that enhance organisational commitment', Journal of Communication 12(1), 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632540810854235 [ Links ]

Bradley, N., 2007, Marketing research: Tools and techniques, Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Brown, D.S., 2001, 'Barriers to successful communication: Part 1. Macrobarriers', Management Review 64(12), 24-30. [ Links ]

Brunetto, Y. & Farr-Wharton, R., 2004, 'Does the talk affect your decision to walk?: A comparative pilot study examining the effect of communication practices on employee commitment post-managerialism', Management Decision 42(4), 579-600. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740410518976 [ Links ]

Buck, G., 2004, Assessing listening, 4th edn., Cambridge University, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Burley-Allen, M., 2005, Listening: The forgotten skill, 2nd edn., Wiley, New York. [ Links ]

Burns, A.C. & Bush, R.F., 2014, Marketing research, 7th edn., Pearson, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Byrne, B.M., 2001, Structural equation modeling with AMOS, basic concepts, applications, and programming, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. [ Links ]

Canary, D.J., Cody, M.J. & Manusov, V.L., 2008, Interpersonal communication: A goals-based approach, 4th edn., Bedford St. Martin's, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Certo, S.C., 2014, Communication, McGraw-Hill Education, viewed 16 January 2016, from http://answers.mheducation.com/business/management/supervision/communication [ Links ]

Cohen, J.R., 2014, 'Open-minded listening', Charlotte Law Review 5, 139-164 (Abstract). [ Links ]

Colquit, J.A., Lepine, J.A. & Wesson, M.J., 2013, Organizational behavior, improving performance and commitment in the workplace, 3rd edn., McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York. [ Links ]

Daft, R.L. & Marcic, D., 2009, Management: The new workplace, 3rd edn., South-Western Cengage, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Daft, R.L. & Marcic, D., 2014, Building management skills: An action-first approach, South-Western Cengage, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Dai, G., De Meuse, K.P. & Peterson, C., 2010, 'Impact of multi-source feedback on leadership competency development: A longitudinal field study', Journal of Managerial Issues 22(2), 197-219. [ Links ]

Daoanis, L.E., 2012, 'Performance appraisal system: Its implication to employee performance', International Journal Economics and Business 1(2), 39-50. [ Links ]

De Janasz, S.C., Dowd, K.O. & Schneider, B.Z., 2009, Interpersonal skills in organisations, McGraw-Hill Education, New York. [ Links ]

Delport, C.S.L. & Roestenburg, W.J.H., 2011, 'Quantitative data-collections methods: Questionnaires, checklists, structured observations and structured interview schedules', in A.S. de Vos, H. Strydom, C.B. Fouché & C.S.L. Delport (eds.), Research at grass roots: For social sciences and human services professions, 4th edn., pp. 171-205, Van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Dixon, T. & O'Hara, M., 2010, Communication skills, viewed 05 April 2018, from http://cw.routledge.com/textbooks/9780415537902/data/learning/11_Communication%20Skills.pdf [ Links ]

Dobbelaer, M.J., Prins, F.J. & Van Dongen, D., 2013, 'The impact of feedback training for inspectors', European Journal of Training and Development 37(1), 86-104. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591311293301 [ Links ]

Dogra, A., 2012, Management skills list, viewed 06 January 2015, from http://www.buzzle.com/articles/management-skills-list.html [ Links ]

Ellis, S.M. & Steyn, H.S., 2003, 'Practical significance (effect sizes) versus or in combination with statistical significance (p-values)', Management Dynamics 12(4), 51-53. [ Links ]

Erdil, G.E. & Tanova, C., 2015, 'Do birds of a feather communicate better? The cognitive style congruence between managers and their employees and communication satisfaction', Studia Psychologica 57(3), 177-193. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2015.03.692 [ Links ]

Erven, B.L., 2012, Overcoming barriers to communication, viewed 25 October 2016, from http://aede.osu.edu/sites/aede/files/publication_files/Overcoming%20Barriers%20to%20Communication.pdf [ Links ]

Flynn, J., Valikoski, T.-R. & Grau, J., 2008, 'Listening in the business context: Reviewing the state of research', The International Journal of Listening 22, 141-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904010802174800 [ Links ]

Fracaro, K., 2001, 'Two ears and one mouth', SuperVision 62(2), 3-5. [ Links ]

French, J., 2013, Poor communication costs businesses billions of rands, viewed 01 August 2016, from http://www.bizcommunity.com/196/371/103718.html [ Links ]

Gondlekar, M.S. & Kamat, M.S., 2016, 'Effect of organizational climate on psychological well being: A study of Vedanta Ltd', The International Journal of Indian Psychology 3(3), 182-195. [ Links ]

Griffen, R.W., 2014, Fundamentals of management, 7th edn., South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Hailu, F.B., Kassahun, C.D. & Kerie, M.W., 2016, 'Perceived nurse-physician communication in patient care and associated factors in public hospitals of Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia: Cross sectional study', viewed 27 September 2016, from http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0162264 [ Links ]

Hartley, P. & Bruckman, C.G., 2002, Business communication, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Henrico, A. & Visser, K., 2012, 'Leading', in S. Botha & S. Musengi (eds.), Introduction to business management - Fresh perspective, pp. 160-189, Pearson, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Heyns, G. & Luke, R., 2012, 'Skills requirements in the supply chain industry in South Africa', Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management 6(1), 107-125. https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v6i1.34 [ Links ]

Holm, O., 2006, 'Communication processes in critical systems: Dialogues concerning communications', Marketing Intelligence & Planning 24(5), 493-504. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500610682881 [ Links ]

Hoppe, M.H., 2007, 'Lending an ear: Why leaders must learn to listen actively', Leadership in Action 27(4), 11-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/lia.1215 [ Links ]

Jiang, J.J., Chang, J.Y.T., Chen, H., Wang, E.T.G. & Klein, G., 2014, 'Achieving IT program goals with integrative conflict management', Journal of Management Information Systems 31(1), 79-106. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222310104 [ Links ]

Johnson, A., 2013, When poor communication has grave consequences, PR & Communications Opinion, viewed 04 January 2015, from http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/18/89702.html [ Links ]

Jones, G.R. & George, J.M., 2013, Essentials of contemporary management, 5th edn., McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York. [ Links ]

Kobeleva, P. & Strongman, L., 2011, Research, teaching and learning: Pedagogy and practice in the open and distance learning paradigm, Universal, Boca Raton, FL. [ Links ]

Krasman, J., 2011, 'Taking feedback-seeking to the next "level": Organizational structure and feedback-seeking behavior', Journal of Managerial Issues 23(1), 9-30. [ Links ]

Krauss, R.M., 2002, 'The psychology of verbal communication', International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences 3(4), 655-701. [ Links ]

Kupritz, V.W. & Cowell, E., 2011, 'Productive management communication - Online and face-to-face', Journal of Business Communication 48(1), 54-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943610385656 [ Links ]

Locker, K.O. & Kaczmarek, S.K., 2014, Business communication: Building critical skills, 8th edn., McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York. [ Links ]

Longenecker, C.O., 2010, 'Coaching for better results: Key practices of high performance leaders', Industrial and Commercial Training 42(1), 32-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851011013698 [ Links ]

Lubatkin, M.H., Simzek, Z., Ling, Y. & Veiga, J.F., 2006, 'Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration', Journal of Management 32(5), 646-672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306290712 [ Links ]

Lunenburg, F.C., 2011, 'Communication: The process, barriers, and improving effectiveness', Schooling 1(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

McDaniel, C. & Gates, R., 2013, Marketing research essentials, 8th edn., Wiley, London. [ Links ]

Mishra, K., Boynton, L. & Mishra, A., 2014, 'Driving employee engagement: The expanded role of internal communications', International Journal of Business Communication 51(2), 183-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414525399 [ Links ]

Neuman, W.L., 2003, Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, 5th edn., Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, T.F.J., 2011, 'Task of management', in J. Strydom (ed.), Principles of business management, 2nd edn., pp. 55-75, Oxford University, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Patoko, N. & Yazdanifard, R., 2014, 'The impact of using many jargon words, while communicating with the organization employees', American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 4, 567-572. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2014.410061 [ Links ]

Pelham, A., 2006, 'Do consulting-oriented sales management programs impact salesforce performance and profit?', Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 21(3), 173-188. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620610662822 [ Links ]

Pfeiffer, J.W., 1998, Conditions that hinder effective communication, viewed 25 October 2016, from http://home.snu.edu/~jsmith/library/body/v06.pdf [ Links ]

Ragusa, A., 2011, Internal communication management, Bookboon: Ventus Publishing ApS, London. [ Links ]

Schreiner, E., 2014, 5 Steps to the communication process in the workplace, viewed 07 September 2015, from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/5-steps-communication-process-workplace-16735.html [ Links ]

Singh, K., 2007, Quantitative social research methods, Sage, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Steiger, J.H., 1990, 'Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach', Multivariate Behavioural Research 25, 173-180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4 [ Links ]

Steyn, H.S., 1999, Praktiese beduidendheid: Die gebruik van effekgroottes, Publikasiebeheerkomitee, Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Struwig, F.W. & Stead, G.B., 2007, Planning, designing and reporting research, Pearson, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Thill, J. & Bovée, C., 2013, Excellence in business communication, 10th edn., Pearson, New York. [ Links ]

Travis, E., 2016, Traits to build team cohesion with managers and employees, viewed 17 July 2016, from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/traits-build-team-cohesion-managers-employees-18100.html [ Links ]

Trees, A.R., 2000, 'Nonverbal communication and the support process: Interactional sensitivity in interactions between mothers and young adult children', Communication Monographs 67(3), 239-261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750009376509 [ Links ]

Trenholm, S. & Jensen, A., 2013, Interpersonal communication, 7th edn., Oxford University, New York. [ Links ]

Truter, I., 2006, 'Barriers to communication and how to overcome them', SA Pharmaceutical Journal 73(7), 55-58. [ Links ]

Tschannen, D. & Lee, E., 2012, 'The impact of nursing characteristics and the work environment on perceptions of communication', Nursing Research and Practice, viewed 17 July 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3316962/ [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, T. & Prideaux, G., 2006, 'Turning professionals into managers using multi-source feedback', Journal of Management Development 25(6), 561-571. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710610670128 [ Links ]

Wertheim, E.G., 2005, Feedback, viewed 09 July 2015, from http://web.cba.neu.edu/~ewertheim/interper/feedback.htm [ Links ]

Yates, K., 2006, 'Internal communication effectiveness enhances bottom-line results', Journal of Organizational Excellence 10(10), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.20102 [ Links ]

Zikmund, W.G. & Babin, B.J., 2015, Essentials of marketing research, 6th edn., Cengage Learning, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mpumelelo Longweni

22965092@nwu.ac.za

Received: 02 Aug. 2017

Accepted: 26 Mar. 2018

Published: 20 June 2018