Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.17 n.1 Johannesburg 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v17i1.481

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries: Application of a model in Zimbabwe

Charles MakanyezaI; Francois du ToitII

IDepartment of Marketing, School of Entrepreneurship & Business Sciences, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe

IIUNISA Graduate School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: The study focused on the application of a model of consumer ethnocentrism in Zimbabwe, a developing country.

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The study sought to determine the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude, to determine the effect of consumer attitude on purchase intention and to establish the moderating effects of gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping and city of residence on the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Research on consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries is still in its infancy. There is a need to conduct more research on consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries in order to enhance an understanding of this important construct in international marketing.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: The study uses a cross section of 289 consumers from Harare and Bulawayo, the two largest cities in Zimbabwe. Structural equation modelling and moderated regression analysis were conducted to test the research hypotheses.

MAIN FINDINGS: The study found that consumer ethnocentrism has a negative effect on consumer attitude, and consumer attitude has a positive effect on purchase intention. None of the demographic variables was found to significantly moderate the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude.

PRACTICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Marketers who intend to expand into developing markets such as Zimbabwe are advised to consider consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes towards foreign poultry products. Firms targeting foreign markets where consumers are ethnocentric, such as in Zimbabwe, are advised to set up manufacturing facilities in such countries instead of exporting.

CONTRIBUTION AND VALUE-ADD: The study enhances our understanding of consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries where research on consumer ethnocentrism is still in its infancy.

Introduction

Globalisation has resulted in increased movement of goods and services across national boundaries. Consequently, consumers all over the world have had more access to various products from other countries than ever before. This development has paved the way for increased global competition among firms (Chowdhury 2013; Tsai, Yoo & Lee 2013). The global poultry industry has not been spared from this phenomenon. The sector has witnessed a massive movement of products across national boundaries. Consumers are now faced with a variety of products - domestic and foreign - from which to make a choice. Likewise, the global poultry sector has become very competitive (Jez, Beaumont & Magdelaine 2011). The need to survive in this international competitive environment has spurred firms to increase their focus towards understanding the behaviour of consumers in target markets, paying particular attention to consumer ethnocentrism (Chowdhury 2013; Tsai et al. 2013). An understanding of the behaviour of consumers in foreign markets is particularly important in that it helps marketers to design effective marketing strategies.

Consumer ethnocentrism is referred to as the beliefs of consumers about whether it is appropriate and moral or not to purchase foreign made products (Pennanen, Luomala & Solovjova 2017; Shimp & Sharma 1987). It is largely agreed in international marketing literature that consumer ethnocentrism negatively influences consumer attitude and purchase intention towards imported products (Balabanis & Siamagka 2017). As such, the success of international business in a particular foreign market essentially depends on the extent to which consumers are ethnocentric, that is, how foreign made products are accepted in a foreign market. Accordingly, consumer ethnocentrism is particularly important in international marketing as it influences the extent to which consumers accept foreign made products (Savitha & Dhivya 2017).

The construct of consumer ethnocentrism has received considerable attention among marketing practitioners and researchers (Bandara & Miloslava 2012; Chowdhury 2013). However, research on consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries is still in its infancy. As such, there is a need to conduct more research on consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries in order to enhance an understanding of this important construct in international marketing practice and research (Chowdhury 2013). Developing and emerging economies offer great international business opportunities (Pentz, Terblanche & Boshoff 2013, 2017).

This study was a logical progression from the study by Makanyeza and Du Toit (2016) that assessed the reliability, validity and dimensionality of the Consumer Ethnocentric Tendencies Scale (CETSCALE; see Shimp & Sharma 1987) in a developing market. Thus, the present study sought to contribute to the existing literature on consumer behaviour and international marketing by applying a consumer ethnocentrism model in Zimbabwe, a developing country. The model integrates consumer ethnocentrism, attitude, purchase intention and consumers' demographic variables. There is a shortage of studies that have addressed the effect of consumers' demographics on the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and consumer attitude. The bulk of studies that have attempted to do so have only focused on the influence of consumers' demographics on consumer ethnocentrism (Balabanis, Mueller & Melewar 2002; Bawa 2004; De Ruyter, Van Birgelen & Wetzels 1998; Hamelin, Ellouzi & Canterbury 2011; Jain & Jain 2013; Javalgi et al. 2005; Kamaruddin, Mokhlis & Othman 2002; Mangnale, Potluri & Degufu 2011; Orth & Firbasová 2003; Supphellen & Ritternburg 2001; Teo, Mohamad & Ramayah 2011; Thelen, Ford & Honeycutt 2006; Vida & Damjan 2001).

The objectives of the study are threefold. The first objective sought to determine the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products. The second objective was to determine the effect of consumer attitude on purchase intention towards imported poultry meat products. The third objective was to establish the moderating effects of consumers' demographics (gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping and city of residence) on the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude.

Imported poultry meat products and Zimbabwe were chosen because of developments in the poultry sector in that country. In this study, the term poultry products refers to fresh packaged whole chicken or chicken cuts, and processed and packaged chicken cuts. There has been a marked increase of imported poultry meat products into Zimbabwe. The products are predominantly from Brazil, South Africa and the USA. This trend started in 2009 soon after Zimbabwe had adopted a multicurrency system (Irvine's 2012). While this has intensified competition within the local market, consumers experienced an increased range of products from which to choose. The need to have a good understanding of the behaviour of consumers with regard to imported products in such an environment is therefore imperative.

Literature review

Consumer ethnocentrism

Marketers have always been concerned with the influence of the foreignness of a product on consumers' product choices (Balabanis & Siamagka 2017). Shimp and Sharma (1987) introduced the concept of consumer ethnocentrism, adapting it from Sumner's (1906) general concept of ethnocentrism. Consumer ethnocentrism refers to the beliefs of consumers about the appropriateness and morality of purchasing foreign made products (Shimp & Sharma 1987). It is concerned with biases that individuals have towards locally made or locally produced products. Consumer ethnocentrism makes consumers believe in the superiority of locally made products and to believe in the inferiority of foreign made products (Pennanen et al. 2017). Consumers who are ethnocentric view purchasing foreign products as inappropriate. They argue that doing so is unpatriotic, hurts the domestic economy and also results in locals losing their jobs. By contrast, non-ethnocentric consumers are likely to consider the actual product attributes or other emotional associations such as nostalgic attachment to a brand or love for the brand (Chowdhury 2013). Thus, consumer ethnocentrism reflects an individual's sense of identity and motivates the feeling of belongingness. As a result, consumer ethnocentrism informs consumers of acceptable or unacceptable purchase behaviour within a group (Shimp & Sharma 1987).

Consumer attitude and purchase intention

Consumer attitude refers to an inclination to behave in a consistently favourable or unfavourable manner towards a given object (Schiffman, Kanuk & Kumar 2010; Solomon 2010). The word 'object' represents such things as products, product categories, brands, places, stores or promotions (Schiffman et al. 2010). Similarly, consumer attitude is concerned with the general evaluation or judgement that people make with respect to products, brands, places or stores. Consumers who like a product are said to have favourable attitudes towards that particular product, while those who dislike a product have unfavourable attitudes towards the product (Solomon 2010).

The basic model of consumer attitude is the tri-component model. This model stipulates that attitude encompasses three components, namely cognition, affect and conation (Solomon 2010). Cognition describes the beliefs of consumers. Consumers believe that consuming a particular product is likely to result in a defined outcome. Thus, consumer beliefs are representative of the attributes that consumers ascribe to that product. Affect is concerned with consumers' feelings or emotions towards a brand or product. As such, the affective component is often referred to as the 'overall brand evaluation'. This implies that, among the three components, only affect comprehensively explains consumer attitude. Consumer beliefs are multidimensional in the sense that they explain various attributes that consumers ascribe to an object. On the other hand, consumer feelings are one-dimensional because they depict the consumer's general inclination towards the product or brand. Therefore, consumer beliefs are relevant to the extent that they explain product or brand evaluations, which in turn are the basic determinants of behavioural intentions. This implies that brand beliefs inform brand evaluations. Conation refers to the intention to buy, that is, behavioural intention or purchase intention. It represents the tendency of consumers to behave in a certain way regarding a particular object. In some cases, the purchase intention may represent the behaviour itself. However, consumers may purchase products regardless of their feelings or emotional attachment to the products (Schiffman et al. 2010).

It is generally agreed that consumer attitude influences what consumers do (Argyriou & Melewar 2011; Blackwell, Miniard & Engel 2006). Similarly, Akar and Topçu (2011) submit that a positive attitude towards a product or brand is most likely to influence an individual to use it. This is consistent with the Theory of Planned Behaviour by Ajzen (1988). The Theory of Planned Behaviour suggests that intention to perform behaviour predicts the behaviour. Thus, a complete understanding of consumer attitude towards imported products is critical in four main ways. Firstly, such understanding enables segmentation of markets. Secondly, it enables the development of new product offerings. Thirdly, it informs the crafting of winning promotional strategies. Fourthly, consumer attitude can be used to predict the behaviour of consumers in the marketplace (Assael 2004; Wilcock et al. 2004).

Demographics

Chowdhury (2013) recognises that consumers' demographic characteristics could play a vital role in influencing the behaviour of consumers. Demographic variables such as gender, age, education and income are some of the critical variables that are used to segment markets (Solomon 2010). As such, it is critical to understand how consumer behaviour is subject to demographic characteristics of the consumer (Chowdhury 2013; Schiffman et al. 2010).

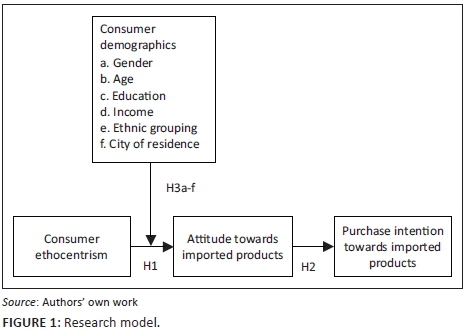

Development of research hypotheses and research model

The general agreement in literature is that consumer ethnocentrism leads to negative consumer attitude towards foreign made products (Bandara & Miloslava 2012; Pentz et al. 2017; Schiffman et al. 2010; Shimp & Sharma 1987). Many studies in both developed and developing countries have reported that consumer ethnocentrism negatively influences consumer attitude towards foreign products (Durvasula & Lysonski 2006; Makanyeza & Du Toit 2016; Moon 2004; Pentz 2011; Ranjbarian, Rojuee & Mirzaei 2010; Shankarmahesh 2006; Supphellen & Ritternburg 2001; Vida & Damjan 2001). In this case, it was plausible to posit that:

H1: Consumer ethnocentrism has a negative effect on consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products.

The consensus among scholars is that a favourable consumer attitude towards a product supports the intention to purchase the product (Argyriou & Melewar 2011; Blackwell et al. 2006; Savitha & Dhivya 2017; Schiffman et al. 2010). Consumer attitudes manifest through what consumers say or do (Schiffman et al. 2010). Therefore, consumers who like a product are said to have favourable attitudes towards that particular product, while those who dislike a product have unfavourable attitudes towards that product (Blackwell et al. 2006). Similarly, Akar and Topçu (2011) found that an individual with a positive attitude towards a product or brand is more likely to use the product or brand. In the same vein, Argyriou and Melewar (2011) posit that positive consumer attitude drives consumers to buy a particular product or brand. Therefore, it was hypothesised that:

H2: Positive consumer attitude positively influences the purchase intention regarding imported poultry meat products.

Research reports mixed findings on the effects of demographics on consumer ethnocentrism (Jain & Jain 2013; Javalgi et al. 2005; Mangnale et al. 2011; Pennanen et al. 2017; Supphellen & Ritternburg 2001; Thelen et al. 2006; Vida & Damjan 2001) and that results differ from country to country (Balabanis et al. 2002). A study of food consumers in Russia established that the characteristics of consumers do not influence consumers' ethnocentrism even though past research suggested otherwise (Pennanen et al. 2017). A study of Indian consumers by Jain and Jain (2013) found a positive relationship between age and consumer ethnocentrism. The same study reported that consumer ethnocentrism was not influenced by gender, education and income. In Morocco, a study found a positive association between age and consumer ethnocentrism while income was negatively correlated with consumer ethnocentrism (Hamelin et al. 2011). An Ethiopian study by Mangnale et al. (2011) reported that men were less ethnocentric than women. However, consumer ethnocentrism in Ethiopia was not influenced by age, education and income. In Russia, education and income were reported not to have a significant influence on consumer ethnocentrism (Thelen et al. 2006). A study of French consumers by Javalgi et al. (2005) found that women and older consumers were more ethnocentric than men and younger consumers, respectively. The study found no significant effects of education and income on consumer ethnocentrism in France. A study by Balabanis et al. (2002) of consumers in the Czech Republic and Turkey reported mixed findings. In Turkey, it was found that females and older consumers were more ethnocentric than their counterparts, while in the Czech Republic, the study found that gender and age did not influence consumer ethnocentrism. In both the Czech Republic and Turkey, education did not influence consumer ethnocentrism (Balabanis et al. 2002). In Poland, age and income correlated, respectively, positively and negatively with consumer ethnocentrism while consumer ethnocentrism was not influenced by gender (Supphellen & Ritternburg 2001). In Slovenia, income and gender did not significantly influence consumer ethnocentrism (Vida & Damjan 2001). Therefore, the following hypotheses were posited:

H3a: The effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude will be stronger for female than for male consumers.

H3b: The effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude will be stronger for older than for younger consumers.

H3c: The effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude will be stronger for less educated than for better-educated consumers.

H3d: The effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude will be stronger for low-income than for high-income consumers.

A study of wealthy college students in a coastal port city in northern China reported interesting findings (Parker, Haytko & Hermans 2011). The study found that the wealthy students had low consumer ethnocentric tendencies and held little animosity towards products from the USA. This suggests that wealthy consumers are more likely to embrace imported products than their low-income counterparts. As such, consumers in Harare, the largest and capital city of Zimbabwe, were expected to be wealthier and less ethnocentric than consumers in Bulawayo, the second largest city in Zimbabwe. The majority of consumers in Harare and Bulawayo are of Shona and Ndebele origin, respectively. Consumers of Shona origin, by virtue of staying in Harare, were expected to be less ethnocentric than consumers in Bulawayo. Drawing insights from this discussion, it was conceivable to hypothesise that:

H3e: The effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude will be stronger for Ndebele consumers than for Shona consumers.

H3f: The effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude will be stronger for consumers in Bulawayo than for consumers Harare.

Based on the foregoing hypothesised relationships, the research model is shown in Figure 1.

Research methodology

Instrument design and measures

The questionnaire was divided into four sections, namely consumer ethnocentrism (ETHN), attitude (ATTI), purchase intention (INTN) and demographic characteristics of the respondents. Demographic variables included gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping and city of residence.

Measurement of consumer ethnocentrism was based on Shimp and Sharma's (1987) CETSCALE, which was adjusted to 14 items following the findings by Makanyeza and Du Toit (2016) in Zimbabwe (see Appendix 1). All items for this scale were measured using a seven-point Likert-type scale. The scale was anchored by 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree.

According to the tri-component attitude model, attitude is made up of three elements, namely beliefs, feelings and intention to purchase (Schiffman et al. 2010). However, consumer attitude has been measured differently from one study to the other. In some cases, the components of consumer attitude have been measured in isolation while in other cases they have been measured in combination (Bruner, Hensel & James 2005; Makanyeza & Du Toit 2016). In the present study, consumer attitude was operationalised as beliefs and feelings, while purchase intentions were measured on their own. This decision was based on previous related studies that treated purchase intention as a separate construct influenced by consumer attitude (Javalgi et al. 2005; Moon 2004; Pentz 2011; Ranjbarian et al. 2010; Shankarmahesh 2006; Supphellen & Ritternburg 2001; Vida & Damjan 2001). To this end, 10 items (5 each for beliefs and feelings) were used to measure consumer attitude (see Appendix 2), while 5 items were used to measure purchase intention (see Appendix 3). The items used to measure attitude and purchase intention were derived from Assael (2004), Brewer and Rojas (2008), Bruner et al. (2005), Groom (1990), Northcutt (2009), Schiffman et al. (2010) and Solomon (2002). The items for attitude and purchase intention were reworded to suit this study. Items for attitude and purchase intention were also measured using a seven-point Likert-type scale. The scale was also anchored by 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree (see Appendices 2 and 3).

Sampling and data collection

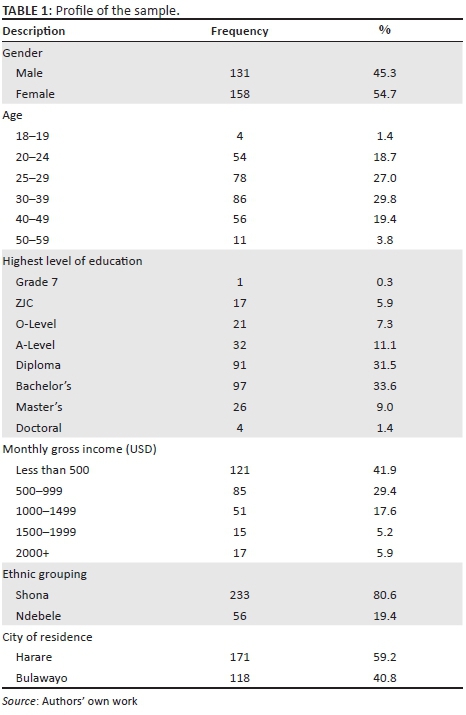

The sample comprised 289 consumers who were surveyed in Harare and Bulawayo. These are the first and second largest cities in Zimbabwe, respectively. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used. Consumers were intercepted as they walked out of main supermarkets. Table 1 presents a description of the sample.

As shown in Table 1, there were slightly more women (54.7%) than men (45.3%). The majority of the respondents (94.8%) were aged between 20 and 49. This suggests that consumers aged beyond 59 were underrepresented in the study. This is in line with the general population distribution in Zimbabwe which shows the majority (79%) of the population as aged between 21 and 59 (FinScope 2011). In terms of the highest level of education attained, the sample was dominated by consumers with diplomas and bachelor's degrees (65.1%). The majority of the respondents (71.3%) earned less than US$1000 per month. There were more people of Shona (80.6%) than of Ndebele (19.4%) origin. More respondents were from the city of Harare (59.2%) than from the city of Bulawayo (40.8%).

Analysis and results

Construct validity

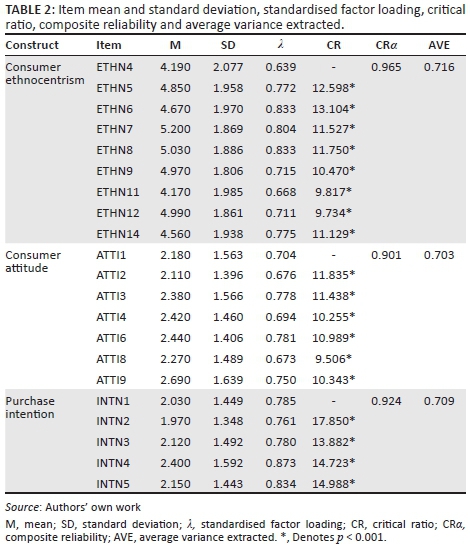

Measurement model fit indices, composite reliability (CRα), standardised factor loadings (λ), critical ratios, average variance extracted (AVEs), squared inter-construct correlations (SICs) and Harman's single factor test (see Podsakoff et al. 2003) were used to assess construct validity. Results showed that there was adequate construct validity.

The model fit indices considered were Chi-square/DF (χ2/DF), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Results showed a fair fit of data to the measurement model (χ2/DF = 1.456; GFI = 0.898; AGFI = 0.879; NFI = 0.913; TLI = 0.938; CFI = 0.948; RMSEA = 0.049). Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen (2008) and Reisinger and Mavondo (2007) suggest that χ2/DF should be less than 3, and the values of GFI, AGFI, NFI, TLI and CFI should be close to 1 while RMSEA should range between 0.05 and 0.10 for a model to be accepted. In order to improve the model fit, standardised factor loadings were assessed to determine whether or not some items were below the cut-off point of 0.6 (Bagozzi & Yi 1988). Five items from the CETSCALE (ETHN1, ETHN2, ETHN3, ETHN10 and ETHN13) and three items from the consumer attitude scale (ATTI5, ATTI7 and ATTI10) had standardised factor loadings less than 0.6. Hence, these items were eliminated from further analysis. The subsequent measurement model had a good fit (χ2/DF = 1.459; GFI = 0.931; AGFI = 0.918; NFI = 0.956; TLI = 0.971; CFI = 0.983; RMSEA = 0.057).

As shown in Table 2, composite reliability coefficients (CRα) for the three constructs were above the minimum cut-off point of 0.7 (Nunnally 1978). All standardised factor loadings were significant (p < 0.001) and above the minimum cut-off point of 0.6 (Bagozzi & Yi 1988). All critical ratios were significant (p < 0.001) and large (> 2) (Segars 1997). All average variances extracted were above the minimum cut-off point of 0.5 (Bagozzi & Yi 1988; Fornell & Larcker 1981; Segars 1997).

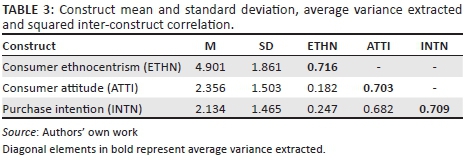

To assess discriminant validity, AVEs were compared with SICs. Results showed that there was discriminant validity among the constructs. As shown in Table 3, all AVEs were greater than the corresponding SICs (Fornell & Larcker 1981; Segars 1997).

Common method bias could be a problem where data were collected from a single informant using the same survey instrument (Heinrichs et al. 2016). As such, Harman's single factor test was applied to determine whether there was a single factor accounting for more than 50% of the total variance. All items for the constructs were included in factor analysis but with the fixed number of factors set at 1. Results showed that only 40.929% of the variance was explained by the single factor. This suggests that common method bias was not present in this study (Wu 2013).

Testing hypotheses

Structural equation modelling was used to test H1 and H2. Results showed a good fit of data to the structural model: χ2/DF = 1.467; GFI = 0.943; AGFI = 0.921; NFI = 0.948; TLI = 0.969; CFI = 0.979; RMSEA = 0.058 (Hooper et al. 2008; Reisinger & Mavondo 2007). Results of H1 and H2 testing are presented in Table 4.

Results indicated in Table 4 show that, in this study, consumer ethnocentrism negatively influenced consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products. Therefore, H1 is supported. Consumer attitude was found to influence purchase intention positively towards imported poultry meat products. H2 is, therefore, supported.

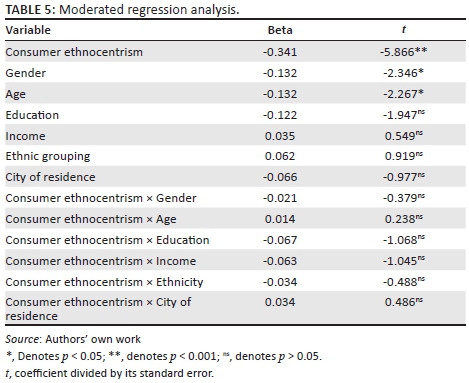

Moderated regression analysis was used to test H3a, H3b, H3c, H3d, H3e and H3f. In the regression model, consumer ethnocentrism, gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping, city of residence and interaction terms, namely consumer ethnocentrism × gender, consumer ethnocentrism × age, consumer ethnocentrism × education, consumer ethnocentrism × income, consumer ethnocentrism × ethnicity and consumer ethnocentrism × city of residence, were used as predictors of consumer attitude. Results of the moderated multiple regression analysis are presented in Table 5.

Results indicated in Table 5 show that none of the interaction terms, namely consumer ethnocentrism × gender, consumer ethnocentrism × age, consumer ethnocentrism × education, consumer ethnocentrism × income, consumer ethnocentrism × ethnicity and consumer ethnocentrism × city of residence, significantly predicted consumer attitude (p > 0.05). This implies that, in this study, gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping and city of residence did not moderate the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products. Therefore, H3a, H3b, H3c, H3d, H3e and H3f are not supported.

Discussion and implications

The study sought to determine the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products, to determine the effect of consumer attitude on purchase intention towards imported poultry meat products and to establish the moderating effects of consumers' demographics (gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping and city of residence) on the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude. The study found that consumer ethnocentrism negatively influenced consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products and that consumer attitude had a positive effect on purchase intention towards imported poultry meat products. In this study, none of the demographic variables had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and consumer attitude. These findings have implications for theory, management and future research.

Implications for theory

The study revealed that, in this study, consumer ethnocentrism negatively influenced consumer attitude towards foreign made products. This implies that ethnocentric consumers had unfavourable attitudes towards imported poultry meat products while less ethnocentric consumers had favourable attitudes towards imported poultry meat products. This finding extends the growing body of consumer behaviour and international marketing literature, which suggests that consumer ethnocentrism has a negative effect on consumer attitude towards imported products (Balabanis & Siamagka 2017; Savitha & Dhivya 2017).

As hypothesised, consumer attitude positively influenced purchase intention towards imported poultry meat products. This implies that participating consumers with positive attitudes towards imported poultry meat products were likely to buy the products. This finding concurs with other scholars that favourable consumer attitudes lead to favourable purchase intentions, which in turn lead to purchase behaviour (Akar & Topçu 2011; Argyriou & Melewar 2011).

A unique contribution of this study to the current body of consumer behaviour and international marketing knowledge was its quest to establish how consumers' demographics influence the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and consumer attitude. This area has not been given due attention in international marketing research and practice. The study found that gender, age, education, income, ethnic grouping and city of residence did not moderate the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer attitude. Failure of demographics to influence this relationship suggests a homogenous buying behaviour for poultry products across demographic consumer segments in Zimbabwe.

Implications for management

Consumer ethnocentrism can be a barrier to international business if it is not adequately addressed. This study advises marketers who intend to expand into developing markets, such as Zimbabwe, to pay particular attention to consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes towards imported poultry meat products. In foreign markets where consumers are ethnocentric, marketers need to be cautious because consumers in those markets are likely to have unfavourable attitudes towards imported products. Instead of employing exporting as a mode of entry into foreign markets where consumers are ethnocentric, marketers are advised to consider setting up manufacturing facilities in such countries, entering into joint ventures and employing local people. Including these in-country initiatives in the local marketing messages could induce favourable attitudes and, consequently, acceptance of such products. Based on the findings of this study, it may not be necessary for marketers to pay particular attention to consumers' demographics when planning marketing programmes in developing countries such as Zimbabwe.

Limitations and future research

Although it makes a contribution to knowledge and provides invaluable insights, this study had limitations which set the agenda for future research. The study considered only one product category in one developing country. It will be worthwhile in future to test the proposed consumer ethnocentrism model in other developing countries. Different product categories should also be considered. Age and ethnic grouping were somewhat unevenly represented among their respective categories. As such, it is recommended that future research consider testing the effects of age and ethnic grouping on the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and consumer attitude using samples with evenly represented categories of age and ethnic grouping. Addressing the limitations of this study could go a long way in advancing the frontiers of knowledge in consumer behaviour and international marketing research.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

C.M. was responsible for the choice and development of methodology, data collection, data analysis and discussion as well as writing of the article. F.d.T. was responsible for the choice and development of methodology, data analysis and discussion as well as writing of the article.

References

Ajzen, I., 1988, Attitudes, personality and behaviour, Open University Press, Milton Keynes. [ Links ]

Akar, E. & Topçu, B., 2011, 'An examination of the factors influencing consumers' attitudes toward social media marketing', Journal of Internet Commerce 10(1), 35-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2011.558456 [ Links ]

Argyriou, E. & Melewar, T.C., 2011, 'Consumer attitudes revisited: A review of attitude theory in marketing research', International Journal of Management Reviews 13(1), 431-451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00299.x [ Links ]

Assael, H., 2004, Consumer behaviour: A strategic approach, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Bagozzi, R.P. & Yi, Y., 1988, 'On the evaluation of structural equation models', Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16(1), 74-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327 [ Links ]

Balabanis, G., Mueller, R. & Melewar, T.C., 2002, 'The relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and human values', Journal of Global Marketing 15(3/4), 7-37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J042v15n03_02 [ Links ]

Balabanis, G. & Siamagka, N.-T., 2017, 'Inconsistencies in the behavioural effects of consumer ethnocentrism: The role of brand, product category and country of origin', International Marketing Review 34(2), 166-182. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-03-2015-0057 [ Links ]

Bandara, W.M.C. & Miloslava, C., 2012, 'Consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes towards foreign beer brands: With evidence from Zlin Region in the Czech Republic', Journal of Competitiveness 4(2), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2012.02.01 [ Links ]

Bawa, A., 2004, 'Consumer ethnocentrism: CETSCALE validation and measurement of extent', VIKALPA 29(3), 43-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090920040304 [ Links ]

Blackwell, R.D., Miniard, P.W. & Engel, J.F., 2006, Consumer behaviour, 10th edn., Thompson South-Western, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Brewer, M.S. & Rojas, M., 2008, 'Consumer attitudes toward issues in food safety', Journal of Food Safety 2008(28), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4565.2007.00091.x [ Links ]

Bruner, G.C. II, Hensel, P.J. & James, K.E., 2005, Marketing scales handbook. Volume IV: A combination of multi-item measures for consumer behaviour and advertising, Thompson Higher Education, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Chowdhury, T.A., 2013, 'Understanding consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries: Case Bangladesh', Journal of Global Marketing 26(4), 224-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2013.814821 [ Links ]

De Ruyter, K., Van Birgelen, M. & Wetzels, M., 1998, 'Consumer ethnocentrism in international services marketing', International Business Review 7(2), 185-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-5931(98)00005-5 [ Links ]

Durvasula, S. & Lysonski, S., 2006, 'Impedance to globalization', Journal of Global Marketing 19(3-4), 9-32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J042v19n03_02 [ Links ]

FinScope, 2011, FinScope consumer survey Zimbabwe 2011, Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare. [ Links ]

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D.F., 1981, 'Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error', Journal of Marketing Research 18(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312 [ Links ]

Groom, G.M., 1990, 'Factors affecting poultry meat quality', in B. Sauveur (ed.), L'Aviculture en Méditerranée, Opt Mediterr Ser A 7, pp. 205-210, Ciheam, Montpellier, France. [ Links ]

Hamelin, N., Ellouzi, M. & Canterbury, A., 2011, 'Consumer ethnocentrism and country-of-origin effects in the Moroccan market', Journal of Global Marketing 24(3), 228-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2011.592459 [ Links ]

Heinrichs, J.H., Al-Aali, A., Lim, J.-S. & Lim, K.-S., 2016, 'Gender-moderating effect on e-shopping behavior: A cross-cultural study of the United States and Saudi Arabia', Journal of Global Marketing 29(2), 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2015.1133870 [ Links ]

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J. & Mullen, M., 2008, 'Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit', Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6(1), 53-60. [ Links ]

Irvine's, 2012, 'Zimbabwe Poultry Association', Chicken Talk: Irvine's Official In-House Magazine 2012(19), 1-25. [ Links ]

Jain, S.K. & Jain, R., 2013, 'Consumer ethnocentrism and its antecedents: An exploratory study of consumers in India', Asian Journal of Business Research 3(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.14707/ajbr.130001 [ Links ]

Javalgi, R.G., Khare, V.P., Gross, A.C. & Scherer, R.F., 2005, 'An application of the consumer ethnocentrism model to French consumers', International Business Review 14(3), 325-344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2004.12.006 [ Links ]

Jez, C., Beaumont, C. & Magdelaine, P., 2011, 'Poultry production in 2025: Learning from future scenarios', World's Poultry Science Journal 67, 105-114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043933911000092 [ Links ]

Kamaruddin, A.R., Mokhlis, S. & Othman, M.N., 2002, 'Ethnocentrism orientation and choice decisions of Malaysian consumers: The effects of socio-cultural and demographic factors', Asia Pacific Management Review 7(4), 555-574. [ Links ]

Makanyeza, C. & Du Toit, F., 2016, 'Measuring consumer ethnocentrism: An assessment of reliability, validity and dimensionality of the CETSCALE in a developing market', Journal of African Business 17(2), 188-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2016.1138270 [ Links ]

Maltin, C., Balcerzak, D., Tilley, R. & Delday, M., 2003, 'Determinants of meat quality: Tenderness', Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 62, 337-347. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2003248 [ Links ]

Mangnale, V.S., Potluri, R.M. & Degufu, H., 2011, 'A study on ethnocentric tendencies of Ethiopian consumers', Asian Journal of Business Management 3(4), 241-250. [ Links ]

McCarthy, M., O'Reilly, S., Cotter, L. & De Boer, M., 2004, 'Factors influencing consumption of pork and poultry in the Irish market', Appetite 43, 19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2004.01.006 [ Links ]

Moon, B.-J., 2004, 'Effects of consumer ethnocentrism and product knowledge on consumers' utilisation of country-of-origin information', Advances in Consumer Research 31, 667-673. [ Links ]

Northcutt, J.K., 2009, Factors affecting poultry meat quality, viewed 20 June 2015, from http://athenaeum.libs.uga.edu/bitstream/handle/10724/12453/B1157.htm?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Nunnally, J., 1978, Psychometric theory, 2nd edn., McGraw-Hill, New York. [ Links ]

Orth, U.R. & Firbasová, Z., 2003, 'The role of consumer ethnocentrism in food product evaluation', Agribusiness 19(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.10051 [ Links ]

Parker, R.S., Haytko, D.L. & Hermans, C.M., 2011, 'Ethnocentrism and its effect on the Chinese consumer: A threat to foreign goods?', Journal of Global Marketing 24(1), 4-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2011.545716 [ Links ]

Pennanen, K., Luomala, H.T. & Solovjova, J., 2017, 'Analyzing the antecedents and consequences of consumer ethnocentrism amongst Russian food consumers', in C.L. Campbell (ed.), The customer is not always right? Marketing orientations in a dynamic business world. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science, pp. 741-749, Springer, Cham. [ Links ]

Pentz, C., Terblanche, N. & Boshoff, C., 2017, 'Antecedents and consequences of consumer ethnocentrism: Evidence from South Africa', International Journal of Emerging Markets 12(2), 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-09-2015-0189 [ Links ]

Pentz, C., Terblanche, N.S. & Boshoff, C., 2013, 'Measuring consumer ethnocentrism in a developing context: An assessment of the reliability, validity and dimensionality of the CETSCALE', Journal of Transnational Management 18(3), 204-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15475778.2013.817260 [ Links ]

Pentz, C.D., 2011, 'Consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes towards domestic and foreign products: A South African study', unpublished PhD dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N.P., 2003, 'Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies', Journal of Applied Psychology 88(5), 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [ Links ]

Ranjbarian, B., Rojuee, M. & Mirzaei, A., 2010, 'Consumer ethnocentrism and buying intentions: An empirical analysis of Iranian consumers', European Journal of Social Sciences 13(3), 371-386. [ Links ]

Reisinger, Y. & Mavondo, F., 2007, 'Structural equation modelling', Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 21(4), 41-71. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v21n04_05 [ Links ]

Savitha, N. & Dhivya, K.N., 2017, 'Consumer ethnocentrism: A comparison between generations X and Y', South Asian Journal of Marketing & Management Research 7(3), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.5958/2249-877X.2017.00010.8 [ Links ]

Schiffman, L.G., Kanuk, L.L. & Kumar, S.R., 2010, Consumer behaviour, 10th edn., Dorling Kindersley, New Delhi. [ Links ]

Segars, A., 1997, 'Assessing the unidimensionality of measurement: A paradigm and illustration within the context of information systems research', Omega International Journal of Management Science 25(1), 107-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0483(96)00051-5 [ Links ]

Shankarmahesh, M.N., 2006, 'Consumer ethnocentrism: An integrative review of its antecedents and consequences', International Marketing Review 23(2), 146-172. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330610660065 [ Links ]

Shimp, T.A. & Sharma, S., 1987, 'Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE', Journal of Marketing Research XXIV, 280-289. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151638 [ Links ]

Solomon, M.R., 2002, Consumer behaviour, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Solomon, M.R., 2010, Consumer behaviour: Buying, having and being, 9th edn., Pearson Education, Essex. [ Links ]

Sumner, W.G., 1906, Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals, Ginn, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Supphellen, M. & Rittenburg, T.L., 2001, 'Consumer ethnocentrism when foreign products are better', Psychology & Marketing 18(9), 907-927. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.1035 [ Links ]

Teo, P.C., Mohamad, O. & Ramayah, T., 2011, 'Testing the dimensionality of consumer ethnocentrism scale (CETSCALE) among a young Malaysian consumer market segment', African Journal of Business Management 5(7), 2205-2816. [ Links ]

Thelen, S., Ford, J.B. & Honeycutt, E.D., Jr., 2006, 'Assessing Russian consumers' imported versus domestic product bias', Thunderbird International Business Review 48(5), 687-704. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.20116 [ Links ]

Tsai, W.S., Yoo, J.J. & Lee, W.-N., 2013, 'For love of country? Consumer ethnocentrism in China, South Korea, and the United States', Journal of Global Marketing 26(2), 98-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2013.805860 [ Links ]

Vida, I. & Damjan, J., 2001, 'The role of consumer characteristics and attitudes in purchase behaviour of domestic versus foreign made products', Journal of East-West Business 6(3), 111-133. https://doi.org/10.1300/J097v06n03_06 [ Links ]

Wilcock, A., Pun, M., Khanona, J. & Aung, M., 2004, 'Consumer attitudes, knowledge and behaviour: A review of food safety issues', Trends in Food Science & Technology 15, 56-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2003.08.004 [ Links ]

Wu, I.-L., 2013, 'The antecedents of customer satisfaction and its link to complaint intentions in online shopping: An integration of justice, technology, and trust', International Journal of Information Management 33, 166-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.09.001 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Charles Makanyeza

cmakanyeza@yahoo.co.uk

Received: 15 Feb. 2017

Accepted: 23 June 2017

Published: 29 Aug. 2017

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3