Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.17 n.1 Johannesburg 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v17i1.399

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Daily news and daily bread: Precarious employment in the newspaper distribution sector in Durban, South Africa

Chibuikem C. Nnaeme

Centre for Social Development in Africa, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: The outsourcing of newspaper distribution seems to be one of the sources of precarious employment for newspaper distribution contractors and their employees

RESEARCH PURPOSE: In an attempt to contribute to the debate on outsourcing, this paper explored the effects of outsourcing newspaper distribution on the labour market experiences of newspaper distribution contractors and their employees in Durban.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: The labour market experiences of workers in precarious employment, especially those in the lower echelon of newspaper distribution, are rarely known.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: The study is a qualitative research which sought to explore the experiences of newspaper distributors in Durban. In identifying the respondents non-probability sampling was used to identify information-rich respondents for interview sections. Also, the research used participant observation to deepen data from interviews.

MAIN FINDINGS: The research finds that the respondents were exposed to precarious employment conditions irrespective of whether they were contracted or not, seemingly because of outsourcing of newspaper distribution in Durban.

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The practical implication suggests that Basic Employment Act is not guiding how the respondents are being treated.

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: The paper specifically highlights the exploitation of newspaper distributors on the streets, as they are denied any form of employment benefits or employment security despite executing their job within severe working conditions.

Introduction

Globally human beings, through street newspaper vending and home delivery, remain crucial in the distribution of newspapers despite innovations in newspaper circulation (Linder 1990:829). However, social justice concerning the employment conditions and treatment of people who engage in newspaper distribution have received little research attention. This study aims to grasp the precarious employment experience of newspaper distributors from Durban's three main newspaper companies, denoted as A, B and C. Thus, the major findings support the argument that outsourcing of newspaper distribution seems to be one of the sources of precarious employment for newspaper contractors and their employees in Durban. The argument is based on the exploration of the effects of outsourcing newspaper distribution on people in the lowest chain of distribution. Firstly, the paper will present the literature on newspaper industry, South African labour market regulation and precarious employment in South Africa. Secondly, it will give an account of the research methodology. Lastly, the paper will present the findings and conclusion.

Literature review

Existing literature on newspaper distribution has focused on the impact of Internet on processes of creation, production and distribution in the newspaper industry value chain (Graham & Hill 2009:165; Stenberg 1997:11). Other researchers have responded to newspaper production and distribution problems, with special emphasis on timely and reduced distribution cost for home delivery (Hurter & Van Buer 1996:85). As Hurter and Van Buer indicate, one of the main problems of newspaper production and distribution is the fact that newspapers are perishable goods.1 Their research focuses on how to '… develop a production and distribution system so as to minimize total cost' (Hurter & Van Buer 1996:86). Linder (1990:829) researched the rights of children who distribute newspapers in the 1980s in the United States to unionise. Kenya is a country where the newspaper industry has received more attention in sub-Saharan Africa. Some Kenyan scholars explored the expansion of distribution of newspapers to the rural areas in Kenya (Muraya 2011; Owino & Oyug 2014), and distribution route planning (Owino & Oyug 2014). Onsoti (2012) studied the impact of social media on newspaper readership among Internet users in Nairobi. Kwamboka (2011) investigated perceptions of branding of the daily newspapers by media buying agencies. Thompson focused on the readership and advertisement in newspaper industry (Thompson 1989:260). None of the literature except Linder's was concerned with the labour market plights of the newspaper distributors at the lowest chain of distribution. While other aspects of newspaper production and distribution have been explored, there is still little understanding of the effects of outsourcing newspapers distribution on people in the lowest chain of distribution, especially in South Africa.

There are different forms of newspaper distribution including shops, home distribution, street selling, vending machines and, more recently, digital distribution. However, this study aims to explore the impact of the outsourcing of distribution of printed newspapers on people at the lowest chain of newspaper distribution who are involved in home delivery (usually known as newspaper carriers [NC]) and street selling (who are known as street sellers [SS]) in Durban.

Labour market regulation in South Africa

The South African labour market regulation has been in transition from the apartheid era to date (Standing, Sender & Weeks 1996:13). The South African labour market under apartheid was perceived as complex, schizophrenic and dualistic because of its ability to uphold two distinct rules and conditions for whites and black workers, respectively (Kenny & Webster 2008:216; Standing et al. 1996:13).

Through various labour regulations acts, such as Basic Conditions of Employment Act (also the amendment) and Employment Equity Act, the democratically elected South African government seeks to regulate basic conditions of employment. South Africa in giving effect to the right to fair labour practices enshrined in section 23(1) of the Constitution and in compliance with the obligation of the International Labour Organization (ILO) stipulated basic standards of employment (Republic of South Africa 1998). After the emergence of a democratically elected government in 1994, the 1995 Labour Relations Act was promulgated to consolidate 'sectoral collective bargaining and sectoral forms of tripartism'2 (Standing et al. 1996:15-16). Standing et al. view the 1995 Labour Relation Act, which came into effect in mid-1996, as an attempt to promote a labour market that is flexibly regulated. Kenny and Webster (2008:216) argue that labour flexibility3 is being initiated simultaneously as the new government is attempting to broaden and consolidate core basic rights of workers who were formally racially marginalised and excluded.

Flowing from labour flexibility, employers through casualisation of employment have moved away from standardised, secured, full-time employment. The trend has been identified with different names such as 'outsourcing', 'subcontracting', 'casualisation', 'externalisation' and 'labour letting', among others. But what all these concepts have in common is declining employment security and benefits. These concepts have been extensively discussed in the South African labour market literature (Bezuidenhout & Fakier 2006:463; Kenny & Webster 2008:216; Standing et al. 1996:95). Kenny and Webster argue that the continuous mutation in the South African labour market appears to sustain the re-segmentation of the labour market which was initiated along racial lines during the apartheid era. Numerous scholars have explored the experiences of workers in service sector (Bezuidenhout & Fakier 2006) and retail sector (Kenny & Webster 2008), among others. However, there is still lack of knowledge in exploring the employment experiences of the street newspapers sellers and home deliverers in South Africa. It is to this knowledge gap that the current study seeks to contribute, especially in line with the Basic Conditions of Employment Act.

Precarious employment in South Africa

The changing nature of employment that seems to manifest among newspaper distributors, both contractors and their employees, seems to be because of outsourcing of distribution in a quest for competiveness, profitability and reduced labour cost. In the post-Second World War period, employment was characterised by secure labour conditions. However, over the recent decades, work has increasingly taken the form of part-time, contract and seasonal works, among others (Cranford, Vosko & Zukewich 2003:7). The common feature of evolving employment conditions is the precarious labour status - compromised job security and stability - experienced by many categories of workers especially in the global South (Benach, Muntaner & Santana 2007:14; Gregory 1980:673; Hadden et al. 2007:7). The evolving employment conditions have been identified with different terms: informalisation of formal employment (Barchiesi 2008:54), non-standard work (Rodgers 1989 cited in Cranford et al. 2003:6; Tompa et al. 2007:209) and precarious employment (Hadden et al. 2007; Rodgers 1989 cited in Tompa et al. 2007:209). Other identification terms include the following: wageless life (Denning 2010); contingent work (Barker & Christensen 1998:1); and 'flexibilisation', 'atypical', 'alternative work' or 'peripheral' or 'marginal' work (Rodgers 1989 cited in Tompa et al. 2007:209).

The increase in 'precarious employment'4 is an effect of labour market flexibility through deregulation of the economy for a freer market that began during the reign of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan from the early 1980s in Britain and the United States, respectively (Carr & Chen 2002:1; Dicks 2007:39; Hart 2010:12; ILO 2002a:12; Kalleberg 2009:6; Standing 2011:5-6). The recent changes in the nature of employment and the emergence of diverse employment conditions from standard legislated and secure labour conditions that emerged after the Second World War (Chen, Vanek & Carr 2004:13-15; Cranford et al. 2003:7; Hadden et al. 2007:7; ILO 2002b:26; Skinner & Valodia 2002:57) are pivotal in the exploration of labour outsourcing on newspaper distribution contractors and their employees. Chen et al. (2004:23) state that precarious employment conditions have a connection to poverty. This is because precarious employment is likely to lack the four pillars of decent work: opportunities, rights, protection and voice (ILO 2002a cited in Chen et al. 2004:25).

Precarious employment has become a major theme in the study of labour market in recent decades globally (Barchiesi 2008:54; Benach et al. 2007:14; Chandra, Nganou & Noel 2002:37; Gregory 1980:673; Skinner & Valodia 2002:57; Standing 2011). Precarious employment is not homogenous, nor does it have a single conception across countries. However, common features exist, namely, temporality, powerlessness, employment insecurities, lack of benefits and low income (Hadden et al. 2007:7; Standing 2011:13). For instance, there is an increase of workers in the formal enterprises without job benefits. According to Cunniah (2013:5),

[t]emporary contracts are becoming the norm, agency work is spreading, casual or day labour as well as forms of "dependent" self-employment are thriving and are even cannibalizing the core of the "formal" economy.

Peter Rossman and Janet Holdcroft describe precarious employment conditions as the outcome of deliberate strategies by big formal firms to evade their social responsibility and deprive workers the right to collective bargaining (cited in Cunniah 2013:5). Kenny and Webster (2008:222) argue, for instance, that labour casualisation of the retail sector has re-segmented the sector into core workers and flexi-workers. The labour market of service, mining and retail sectors is the representation of two common flexible forms of labour in South Africa: labour outsourcing and casualisation. While the latter concerns the reduction of statutory employment benefits and protection for workers in direct employment, the former concerns the commercialisation of employment through externalisation of labour to brokers (Kenny & Webster 2008:222). For example, Rees (1998:2-3) observed that while standardised employment in retail industry declined by about 1% between 1987 and 1997, casual employment escalated by 44.7% between 1987 and 1997 in South Africa (cited in Kenny & Webster 2008).

From the above discussion, precarious employment conditions are linked to outsourcing of various sections of production or distribution processes in order to lower input cost. As a contribution to newspaper industry literature, this paper seeks to explore the experiences of those at the lower chain of newspaper distribution to understand whether there is a relationship between outsourcing and precarious employment in newspaper distribution in Durban. The study is pertinent because little knowledge has been generated on the labour experiences of those who are engaged in the lower chain of newspaper distribution especially in South Africa.

Research method and design

In an attempt to respond to the research objective, primary and secondary data were collected. Primary data include in-depth interview responses from newspaper distribution contractors and their employees, as well as distribution managers from the three main newspaper companies in Durban within 4 months (July-November 2014). Purposeful sampling was used to identify most of the respondents. The interviews with the distribution managers were aimed at the provision of necessary background information on the changes in the company's newspaper circulation methods and other related information. Primary data also include pictures of the sites for newspaper selling and delivery. Also participatory observation method was employed to explore the distribution conditions of the respondents.

Participatory and observation data collection methods have been associated with 'the systematic description of events, behaviours, and artifacts in the social setting chosen for study' (Marshall & Rossman 1989:79 cited in Kawulich 2005:1). Through active participation and observation, which are research tools for exploration, I was able 'to learn about the activities of the people under study in the natural setting through observing and participating in those activities' (Kawulich 2005:1). I participated in street selling twice, both on major streets in Durban and suburbs. It was through these methods that I came to witness the precarious labour conditions in which contractors and their employees distribute newspapers. For instance, through participation, I realised how exhausting selling newspapers on Dr Pixley KaSeme Street (formerly known as West Street) from 6:00 to 16:00 could be while standing. I experienced the same level of exhaustion the day I joined newspaper carriers to deliver newspapers to subscribers. We covered several kilometres on foot while carrying over half a bundle of newspapers each on our heads. Through the participation in the work of my respondents, I confirmed the challenges such as weather, income and harsh working conditions, which were emphatically mentioned throughout the interviews.

From July to November 2014, in-depth interviews were conducted in Durban with seven SS of newspapers, three NC, three newspaper distribution contractors and three circulation managers from three newspaper companies. The findings also shed light on the effects of outsourcing newspaper distribution on the exploited echelon in the newspaper distribution chain. Table 1 presents general information of the respondents.

Findings

The crux of every section of this empirical report is the precariousness of the lower echelons in the newspaper distribution chain in Durban. The lower strata in newspaper distribution in Durban saw their participation as interview respondents as an outlet to share their precarious labour market experiences. The findings are thematically analysed. The themes were identified based on the frequency of the themes to respondents. The themes include employment security and benefits, working conditions and managers' response to distribution outsourcing.

Employment security and benefits

The lack of employment security and benefits, such as unemployment insurance fund (UIF), sick leave, benefit in case of hijacking and death, among others, are a major source of concern for all the contractors and their employees. For instance, Beatrice, Newspaper company A's home delivery contractor, narrated the change in benefits and entitlements5 from when she started to till date:

'… around 1995, Newspaper company A saw the writing on the wall. And they saw that they would have to start paying more. So what did they do? They got rid of us. They put us unto contract, where we cannot claim anything. They give us the contract and say: 'sign it or don't sign it'. What can we do? But we got nothing, no leave, no sick leave, we got nothing. The day you stop working, the day you stop earning.

Nobody cares. It is so cold. It really is. I mean sellers take their lives into their hands every morning. One of the guys was shot down at Checkers a year or so ago. He was selling newspapers early in the morning. We are distributing their newspapers but we cannot claim from them. We are doing the job, we take the risk. The same with me, I was hijacked here in the garage two years ago, my car was taken, my hand bag was taken, my pay was taken. Everything was taken from here, and I was left here standing in the garage. They (Newspapers company A) did not come to help me. They did not even say: ok your pay has been stolen, we will at least give you such amount. No. I am the one that is losing out. They do not take responsibility. Plus you have to have a motor car to do the job. And they will not care about the car. It is a vicious circle.' (Respondent 4, contractor, 30th September 2014)

Pointing at NC who take newspapers to subscribers' homes, Beatrice continues:

'[t]hese little boys that come on Sunday morning, they also risk their lives. They come from informal settlement. There are crooks in every single corner, they robbed them of their shoes. So these little boys sometimes are on the run for their lives on Sunday morning in endeavor to get to deliver newspapers on Sunday morning. And then we have a cut off time to get the papers delivered. So it is all in their (Newspapers A) favour, nothing for us. They use to give these boys raincoat, they use to give them tracksuit for winter, they use to give them a little Christmas gift, they use to give them a little voucher to go to shops to buy something for themselves, but not anymore.

If they had shot me or stabbed me when they took my motor car, I would not get anything. My family would have gotten nothing. The same as for these guys (pointing to her newspaper carriers) if they get stabbed while doing their routes on Sunday morning, they get nothing.' (Respondent 4, contractor, 30th September 2014)

The above extract represents proper employment benefits that ceased since the newspaper distribution was outsourced. The extract not only enumerated lack of employment security but also physical security of those at the lower chain of newspaper distribution in Durban. Thus, lack of employment security and benefits, which are the characteristics of precarious employment, were mentioned in the above quote as a representation of common experience among the respondents.

Also lack of any form of employment security and benefits contributes to high turnover of SS and NC. The majority of those interviewed in this category are seeking for another job because they claim to be in a precarious job with dire working conditions, menial income and no employment benefit. For instance, Nomsa, an SS, thinks that the reason that people have left the job in the past is because 'they (her former colleagues) thought the money they earn is small, and they do not have tables and a seat for selling newspapers'. Also, the awareness that they are entitled to nothing, no matter how long they have been working as newspaper sellers and deliverers, is a mantra that was resoundingly repeated by almost all interviewed.

Some also noted that families of the deceased colleagues got nothing from either the contractor or the newspaper company. The three quotes below from three SS portrayed what was continuously mentioned by most respondents:

'My friend who was also in this job died long time ago, about 10 years ago. He died in an accident in Phoenix. Yea, the van went under a bridge he [my friend] died. Last week another colleague of mine died of cancer. He was selling papers for 20 years. And his family got nothing. Before we use to work directly for the company, but now everything is on contract. So those former colleagues that died did not get anything.' (Respondent 7, street seller, 3rd September 2014)

'The negative side of this job is that there is no money, you cannot depend on it because if you are hit by a car now everything gonna lay down. Nothing from the company. There is not security, you are securing yourself.' (Respondent 12, street seller, 27th August 2014)

'I do not have any contract with my boss and I am not covered by any insurance. If I am injured or sick nothing happens. Even someone who was working for 35 years died and nothing was given to his family. You can't get nothing. I like this job because I cannot get another job. But I am looking for another job because, as I told you, that even if I have worked for 35 years, I can't get nothing if I died. For this job, I can't get anything. If I am sick I am sick. Nothing can I get.' (Respondent 9, street seller, 2nd September 2014)

While commenting on her deceased colleagues, another SS mentioned that '[t]hey got nothing because when you are working you are working for yourself. And when you die, you die' (Respondent 7, street seller, 4th September 2014). The lack of benefits and security was commonly reported by contractors, SS and NC as follows: 'if I do not work I will not get paid even if I am very sick'. All the SS and NC interviewed clearly mentioned that they did not have any form of benefit, UIF, sick leave with pay or any other form of employment security.

This theme first established that the condition of newspaper distribution has evolved from what it formerly was. It has changed because most employment securities and benefits as enumerated in the selected direct quotes from the respondents have now ceased because of outsourcing. In other words, because of the labour outsourcing, certain levels of benefits and protection enjoyed by those engaged in newspaper distribution earlier are no longer available to them today. Some of them even told that they were richer as newspaper distributors 20 years ago than what they are now.

Working conditions

One major condition of the job was the working hours, or what Patrick (Respondent 6, contractor, 8th October 2014) described as 'ungodly hours'. All the SS interviewed stated that they leave home for work on average at 05:00 every morning from Monday to Saturday. 'Newspaper company A' contractor has this to say about the working hours on Sundays and the risk involved for her:

'I cannot go to bed on Sunday till I get the papers delivered by the company, this is because they cannot tell me exactly when the paper will arrive. They tell me that they can come anytime from 1 o'clock in the morning. So why go to bed only to wake up at 1 o'clock? I just sit on a chair waiting for them. That is how it has been for 25 years now. I must wait and wait. Last Sunday the paper came around 2:30 in the morning, Sunday before last they came at 3:15. So no sleep till they come. And then, when I finish, I have to do complaints, non-deliveries, all the area managers have to do that, and the cut off time for all that is 11 every Sunday morning. So I am on duty from 1 o'clock, when the paper should be delivered, up until 11 o'clock, and there is no double pay.' (Respondent 4, contractor, 30th September 2014)

The second major working condition concern for SS and NC is the weather. The respondents complained of not being provided with shade, umbrellas or raincoats that would protect them and the newspapers from rain and windy conditions. When these concerns were related to Newspaper company B distribution manager, he said:

'You know thing like raincoats and things like that we supply to contractors. But if a contractor tells me that he got 50 guys working for him on the street, I give him 50 rain coats. But what does the contractor do? He does not give every guy selling newspaper for him a raincoat. I cannot manage the employees of the contractors, they have to manage their staff. There is always something that happens, people do not work for years and years. Some of them work for a very short time and move on. Then if you are to give some guys who would only work for few weeks or month raincoat and other things, it is not cost effective. The turnaround of staff is very high because it is a menial job, selling newspapers on a corner is a boring job, even for the most boring person it is a boring job. Imagine being there every day.' (Respondent 2, manager, 1st October 2014)

But from a follow-up enquiry into the above claim, the researcher discovered that a raincoat had not been provided to any SS and NC. In fact, the researcher noticed that Newspaper company B contractors mainly narrate how newspapers are protected from rain when asked to talk about the measures taken to protect their employees from adverse weather conditions. Raph reported:

'When it is raining for example we have plastics. We put them (newspapers) in nice plastics, we wrap them up, emm. In certain places we put them into the post box. With regards to whether we have our on and off days, we do. But the company provides us with plastics to protect the papers.'

When the question on what measure he had taken to protect his workers from rain was repeated, the same contractor revealed that:

'I cannot lie to you, they (newspaper carriers) come with their own stuff (raincoats, jackets). Some of them prefer not to wear jackets or raincoats when they are working, it is much easier and faster because they continuously jump in and out of the vehicle. It is uncomfortable to work with a lot of clothing on. And during summer time the guys are using shorts and sandals because it is hot and they prefer working freely.' (Respondent 5, contractor, 11th October 2014)

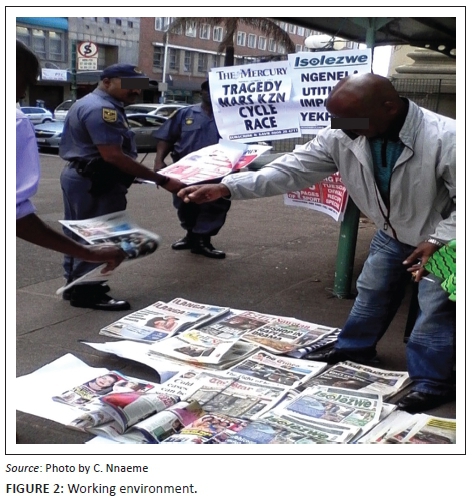

A related aspect of working conditions was the working environment. It was reported and observed during the research that none of the SS were provided with newspaper stands, tables or chairs. Most of them spread the papers on the ground while standing from morning till the end of the day's work. Some use crates as tables and chairs while others use nothing, just standing as depicted in Figures 1 and 2. The scenarios have been properly captured in the pictures6 below. Photographs of Figures 2 and 4 were taken on 13 October 2014 at 13:59 and 13:58, respectively, on a windy day, and that of Figure 3 was taken on 17 October 2014 at 13:32, on a rainy day. The pictures depicted the difficult working environment of newspaper distributors. In Figure 3, the two black crates covered in white papers served as a table, and the other crate beside was used as a chair a few minutes before the rain started. It was also noted that the day photographs of Figures 3 and 4 were taken NC around Davenport and Umbilo were seen delivering newspapers under rain without wearing raincoats but the newspapers being delivered were properly covered in plastic bags. An NC in one of the areas mentioned says that '[w]e deliver newspapers even if it is raining, sometimes the papers get wet due to rain' (Respondent 15, newspaper carrier, 29 September 2014). According to Nickel, a SS along Dr Pixley KaSeme Street (formerly known as West Street), 'when it is raining or windy and all that I cannot sell because I got no shelter here. When there is heavy rain or wind I must move away from here because I got no shelter here'. (Respondent 8, street seller, 3rd September 2014)

One of the SS whose site was captured in the picture noted:

'The problem is when it is raining, I don't have an umbrella, I don't have a tent. My boss promised me that he was gonna get the tent, next month, next month, until now. Every one of my colleagues that I know tells our boss that we need umbrella. But he keeps telling us next month, next month.' (Respondent 9, street seller, 2nd September 2014)

In responding to difficulties posed by rain, 'Newspaper company B' distribution manager reported the following:

'If you are delivering post even when it is raining you deliver post. If you selling newspapers on a street, if it is raining you will still be selling newspapers on a street. It is your job. Nothing is going to change about that, not even weather.' (Respondent 2, manager, 1st October 2014)

The working conditions discussed so far capture inhuman treatment of newspaper distribution workers, and as such contrary to the South African Basic Conditions of Employment Act. The distributors are not happy about their working condition, but at the same time they are helpless as they have no claim from the newspaper companies. This is exactly the benefit of labour outsourcing, to absolve the firms of the responsibility to labour (Castells & Portes 1989). The working conditions once again reinforce what the previous theme noted: that outsourcing of newspaper distribution breeds precarious employment.

Managers on distribution outsourcing

Outsourcing of distribution has become a basic characteristic of newspaper circulation in Durban. Newspaper company B circulation manager stated that they (the company) are in the business of news, not in the business of newspaper circulation. Hence, the firm outsources newspaper distribution to companies and agents, whom the company pays for the services they provide. According to him,

'we cannot have contracts with street sellers because there will be too many relationships to manage. If I got five hundred street sellers, then I have five hundred contractual relationships to manage. I will rather have a relationship with a contractor who would then employ the five hundred street sellers. So it is much cheaper and cost effective to give to a company to manage it for us (Respondent 2, manager, 1st October 2014).'

Among several consequences of outsourcing newspaper distribution was exploitation of workers, especially those in the lowest chain of distribution networks. According to Nickel, a street newspaper seller for 35 years:

'The contractors we are working for now do not cover us. Then, we were registered directly with the company. Now we are not registered, it is only through contractors. It is so different now because if I do not sell newspapers I would not be paid. Then the company was paying UIF, sick leave, medical aid everything, now everything is stopped.' (Respondent 8, street seller, 3rd September 2014)

In responding to the precarious working conditions of lower echelons in newspaper distribution, the distribution managers justified outsourcing newspaper distribution because of cost reduction, avoidance of providence funds, manageable size of employees and cost effectiveness.

Outsourcing of newspaper distribution exacts a negative effect on trade unions and collective bargaining. Outsourcing restores the absolute powers of employers to fire and hire and retards the gains workers earned through class struggles (Portes 1983:163). It was stressed by both contractors and their employees separately that there is no union. According to an SS, 'there is no union of newspaper sellers. If any newspaper seller has a problem, it is their own problem' (Respondent 7, street seller, 4th September 2014). The weakening of trade union and collective bargaining power is one of the outcomes of labour outsourcing.

Conclusion

The research has attempted to explore the experience of newspaper distribution workers in Durban who are exposed to precarious labour market experiences because of newspaper publishers' drive for profit, reduced labour cost and competitiveness. The precarious employment conditions of newspaper distribution contractors and their employees are the major effects of outsourcing newspaper distribution in Durban. It was demonstrated in the research that the precarious labour market experiences arise because of outsourcing.

It was also discovered that the labour flexibility through outsourcing of newspaper distribution for higher profit was the reason why newspaper distribution contractors and their employees were exposed to precarious employment conditions contrary to the Basic Conditions of Employment Act. The research also exposed the newspaper industries as the beneficiaries of outsourcing newspaper distribution in Durban, and the distribution contractors and their employees as the labour market victims. However, the researcher hopes to advocate for better treatment of newspaper distribution workers, especially those at the lowest chain of distribution. For instance, provision of raincoats, stands and chairs will go a long way in helping reduce the frustration and the negative feelings the respondents have about their work. It may be true that the government has passed labour law that protects these workers, but the most important fact is the enforcement of the labour regulation acts.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges Prof. Richard Ballard, Prof. Francie Lund and Prof. Leila Patel, and the reviewers and editors as well as all who assisted to make this paper a reality.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Barchiesi, F., 2008, 'Hybrid social citizenship and the normative centrality of wage labor in post-apartheid South Africa', Mediations 24(1), 52-67. [ Links ]

Barker, K. & Christensen, K., 1998, Contingent work: American employment relations in transition, ILR Press, New York. [ Links ]

Benach, J., Muntaner, C. & Santana, V., 2007, Employment conditions and health inequalities, Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health(CSDH). Employment Conditions Knowledge Network (EMCONET). Geneva: WHO. [ Links ]

Bezuidenhout, A. & Fakier, K., 2006, Maria's burden: Contract cleaning and the crisis of social reproduction in post-apartheid South Africa, Sociology of Work Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Carr, M. & Chen, M., 2002, Globalization and the informal economy: How global trade and investment impact on the working poor, International Labour Organization, Geneva. [ Links ]

Castells, M. & Portes, A., 1989, 'World underneath: The origins, dynamics and effects of the informal economy', in P. Alejandro, C. Manuel & B. Lauren (eds.), The informal economy: Studies in advanced and less developed countries, pp. 11-41, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MA. [ Links ]

Chandra, V., Nganou, J. & Noel, C., 2002, Constraints to growth in Johannesburgs black informal sector: Evidence from the 1999 informal sector survey, World Bank Report No. 24449-ZA, The World Bank, Washington, DC, viewed 08 June 2014, from http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP [ Links ]

Chen, A., Vanek, J. & Carr, M., 2004, Mainstreaming informal employment and gender in poverty reduction: A handbook for policy-makers and other stakeholders, Commonwealth Secretariat, London. [ Links ]

Cranford, C., Vosko, L. & Zukewich, N., 2003, 'Precarious employment in the Canadian labour market: A statistical portrait', Just Labour 3(1), 6-22. [ Links ]

Cunniah, D., 2013, 'Meeting the challenge of precarious work: A workers' agenda', International Journal of Labour Research 5(1), 5-7. [ Links ]

Denning, M., 2010, 'Wageless life', New Left Review 66, 79-97. [ Links ]

Dicks, R., 2007, 'The growing informalisation of work: Challenges for labour - Recent developments to improve the rights of atypical workers', Law, Democracy & Development: Special Issue 11(1), 39-48. [ Links ]

Graham, G. & Hill, J., 2009, 'The regional newspaper industry value chain in the digital age', OR Insight 22(3), 165-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/ori.2009.5 [ Links ]

Gregory, P., 1980, 'An assessment of changes in employment conditions in less developed countries', Economic Development and Cultural Change 28(4), 673-700. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/451211 [ Links ]

Hadden, W., Muntaner, C., Benach, J., Gimeno, D. & Benavides, F., 2007, 'A glossary for the social epidemiology of work organization, Part 3, Terms from labour markets', Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61, 6-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.032656 [ Links ]

Hart, K., 2010, Africa's urban revolution and the informal economy, viewed 30 May 2014, from https://www.econbiz.de/…/africa…urban-revolution-and-the-informal-economy [ Links ]

Hurter, A. & Van Buer, M., 1996, 'The newspaper production/distribution problem', Journal of Business Logistics 17(1), 85-107. [ Links ]

International Labour Organization (ILO), 2002a, Decent work and the informal economy, International Labour Conference 90th, Report VI, ILO, Geneva. [ Links ]

International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2002b, Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture, ILO, Geneva. [ Links ]

Kalleberg, A., 2009, 'Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition', American Sociological Review 74(1), 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400101 [ Links ]

Kawulich, B., 2005, 'Participant observation as a data collection method', Forum Qualitative Social Research in Research 6(2), 1-84. [ Links ]

Kenny, B. & Webster, E., 2008, 'Eroding the core: Flexibility and the re-segmentation of the South African labour market', Critical Sociology 24(3), 216-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089692059802400304 [ Links ]

Kwamboka, N., 2011, 'Perception of brand equity of daily newspapers by media buying agencies in Nairobi, Kenya', A Masters dissertation submitted to the University of Nairobi, Kenya in November 2011. [ Links ]

Linder, M., 1990, 'Fromstreet urchins to little merchants: The juridical transvaluation of child newspaper carriers', viewed 16 July 2014, from http://wwwir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? [ Links ]

Marshall, C. & Rossman, G.B., 1989, Design qualitative research, Sage, Newbury Park, CA. [ Links ]

Muraya, W., 2011, 'Forecasting market shares of daily newspapers in Kenya. Application of market brand switching model', Masters Dissertation submitted to the University of Nairobi Kenya in November 2011. [ Links ]

Onsoti, R., 2012, The impact of social media on newspaper readership among internet users in Nairobi: A case study of Daily Nation newspaper in Kenya, viewed 18 August 2014, from http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/11469 [ Links ]

Owino, J. & Oyug, L., 2014, 'Role of logistics on sales turnover: A survey of newspaper sales by vendors in Migori Town-Kenya', Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business 5(11), 211-231. [ Links ]

Portes, A., 1983, 'The informal sector: Definition, controversy, and relation to national development', Review 7(1), 151-174. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa, 1998, Basic conditions of Employment Act, Department of Labour, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Skinner, C. & Valodia, I., 2002, 'Labour market policy, flexibility, and the future of labour relations: The case of KwaZulu-Natal clothing industry', Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 50(1), 56-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/trn.2003.0015 [ Links ]

Standing, G., 2011, The precariat: The new dangerous class, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, New York. [ Links ]

Standing, G., Sender, J. & Weeks, J., 1996, Restructuring the labour market: The South African challenge, An ILO Country Review, Geneva, International Labour Office. [ Links ]

Stenberg, J., 1997, 'Global production management in newspaper production and distribution - Coordination of products, processes and resources', Doctoral Thesis, The Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. [ Links ]

Thompson, R., 1989, 'Circulation versus advertiser appeal in the newspaper industry: An empirical investigation', The Journal of Industrial Economics 37(3), 259-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2098614 [ Links ]

Tompa, E., Scott-Marshall, H., Dolinschi, R., Trevithick, S. & Bhathacharyya, S., 2007, 'Precarious employment experiences and their health consequences: Towards a theoretical framework', Work 28, 209-224. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Chibuikem Nnaeme

cornely@live.com

Received: 11 May 2016

Accepted: 13 Nov. 2016

Published: 28 Feb. 2017

1 Perishable goods refer to products which have declined value if stored or which cause economic loss if not delivered in time to consumers. Hurter and Van Buer categorised perishability into three classes: firstly, goods that are perishable only when considered by the customer, for example, late supply of an aspect of production such as a car seat to a car manufacturer causes economic loss. Secondly, goods that are perishable only to the manufacturer, for example, chemical manufacturer. Thirdly, products that are perishable to both manufacturer and customer, for example, newspapers. Newspapers are timely products which benefit neither the producer nor the buyers when delivery is late (Hurter & Van Buer 1996:85).

2 Tripartism refers to the union of employers, workers and government in dealing with labour market challenges.

3 Labour flexibility refers to 're-segmenting the South African labour market and creating greater insecurity and unemployment for both core and flexi workers' (Kenny & Webster 2008:217). 'And such labour strategy which aimed at "Flexibility" increasingly erodes the hard-won rights of core workers' (Kenny & Webster 2008:222). According to Standing et al. (1996:81), labour flexibility is about control and subjectivity as both employers and employees want each other to be flexible on their favourable and subjective terms.

4 Precarious employment refers to work with high uncertainty, unpredictability and risk from the point of view of the worker (Kalleberg 2009:2).

5 By entitlements I mean sick leave, rain coats, bonuses and so on.

6 The respondents in the photos gave specific consent for their photos to be published.