Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.16 n.2 Johannesburg 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v16i2.419

CHAPTER 7

Is it worthwhile pursuing critical management studies in South Africa?

Geoff A. Goldman

Department of Business Management University of Johannesburg South Africa

SUMMARY

Since the so-called paradigm wars of the 1980s and 1990s, many social sciences, including business management, have entered a state of methodological tolerance where positivists and anti-positivists are involved in an uneasy truce. The aftermath of these paradigm wars have highlighted the necessity for a multi-paradigmatic approach to social sciences. Against this backdrop, critical management studies (CMS) has made its way into the business-management discourse in the early 1990s. However, in South Africa, there seems to be a marked lack of a coherent body of knowledge on and awareness amongst business-management academics of CMS. Based on this, Chapter 7 sets out both to establish the level of familiarity amongst businessmanagement scholars regarding CMS and to assess the prevailing climate in the domain of business management.

By means of a two-stage qualitative survey, data were firstly gathered regarding the level of familiarity with CMS from 88 senior South African academics at 16 higher-education institutions. In stage two of the qualitative survey, data were solicited from 21 senior academics at 13 higher-education institutions. This data were subject to content analysis, employing Creswell's (2003) coding principles. Findings revealed that, although individual academics were open to exploring a paradigm such as CMS, the paradigmatic dominance of the positivist tradition in South Africa has resulted in institutional challenges that hinder a coherent effort to expand CMS as an emergent paradigm in South Africa.

Introduction

This research aims to ascertain the current level of familiarity with critical management studies amongst South African business-management academics. Furthermore, Chapter 7 also investigates business-management academics' opinion concerning the current climate within the field of business management (and related disciplines) as an academic domain. Traditionally and historically, a positivist tradition with associated quantitative techniques and methods seems to have typified the scholarly endeavour of business management in South Africa. However, in recent times, it has become apparent through conversations with peers that there is a movement toward exploring different research traditions and alternate research methods and techniques.

This, together with my personal journey of inquiry that has directed me to critical management studies (CMS), has prompted the focus on the current climate in the academic domain of business management in South Africa. As CMS is a relatively new movement of thought, it begs the question of how familiar South African business-management scholars are with it and how susceptible the academic community would be to a more formalised pursuit of CMS, given the current climate within this domain.

It needs to be stressed that Chapter 7 is not necessarily presented in a style that CMS scholars are familiar with, nor is it presented in a style normally associated with 'mainstream' scholarly work in management. This is intentional as it represents where I often find myself. I view myself as someone who is in the process of migrating from the mainstream to more of a critical position within the broader discipline of business management. I find the possibilities of CMS alluring and provocative, but I often battle to move away from the comfort zone presented by more 'mainstream' methodologies as that is the basis of my formal education and much of my experience. The style of Chapter 7 is therefore indicative of this migration towards critical scholarship.

Literature review

In this literary overview, I expand on the phenomenon of the so-called 'paradigm wars'. Thereafter, this methodological tension will be considered within the South African context. The literature review will conclude by examining the effect of adding a third paradigm - that of CMS - to business management as a field of academic inquiry.

The paradigm wars and associated aftermath

The so-called paradigm wars emerged in the 1980s due to the apparent shortcomings of positivist methodologies to deal with the demands of culture-orientated research in not only business management and related disciplines but in all social sciences (Buchanan & Bryman 2007; Denison 1996; Terrell 2012; Waite 2002). Scholars concerned with culture-orientated business-management research pointed out that the basic search for universal assumptions and principles to govern the activity of business management is incongruent with the context-specific nature of culture-orientated research. As a result, these scholars turned to methodologies proposed by interpretivists as a guiding ontological grounding for their work (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie 2004; Oakley 1999; Terrell 2012).

The ensuing jockeying for position is not always viewed as constructive in working towards greater commonalty of purpose amongst businessmanagement academics (Denison 1996). Inevitably, the paradigm wars degenerated into proponents of one camp attempting to discredit proponents of the opposing camp in an effort to gain heightened legitimacy within the scholarly space (Mingers 2004). This has resulted in the creation of positivist and interpretive orthodoxies that stand juxtaposed to each other and has caused a contrast between these stances that is often more ostensible than real (Denzin 2010; Neuman 2006).

The emphasis on proving the legitimacy of one camp over and often at the expense of, the other has left very little room for claims of legitimacy from scholars who attempt to combine the two perspectives into a so-called mixed-methods paradigm (Denzin 2010; Flick 2002; Guba & Lincoln 2005). The creation of the methodological orthodoxies mentioned above has resulted in claims from both camps that combining these two paradigms is not possible, given their contrasting ontological positions (Denison 1996). The paradigm wars have also resulted in much greater emphasis on the methodological correctness of the chosen research method, which has diverted necessary energy away from providing sorely-needed rich and full descriptions of the object or phenomenon under investigation and have reduced many research outputs to the mundane and obvious (Oakley 1999; Waite 2002).

Some authors point out that it does appear as though the paradigm wars have abated in recent times (Denzin 2010; Mingers 2004; Shaffer & Serlin 2004; Terrell 2012). Methodological fundamentalism seems to have now been replaced by methodological tolerance where proponents of both camps seem to recognise the legitimacy of the other under certain conditions (Mingers 2004). Also, new paradigms such as postmodernism and critical theory have also entered the management discourse, fuelled in part by an increased trend to explore these peripheral traditions from within the humanities (Waite 2002).

Thus, although the paradigm wars seem to have ceased for the most part, the academic discipline of business management (and associated areas of inquiry) appears to have now entered a phase where the domain is ontologically and methodologically more fragmented than in the past (Buchanan & Bryman 2007). The challenge that is now evident emanates from one of the consequences of the paradigm wars mentioned above. This entails the eradication of juxtapositions between the positivist and interpretive traditions in favour of a more cooperative, multi-paradigmatic stance where cooperation between paradigms is sought and encouraged in an effort to address not only issues crucial to business but also issues crucial to those groupings affected by business (Cameron & Miller 2007; Shaffer & Serlin 2004; Teshakkori & Teddlie 2003).

Apparent methodological tension in the South African context

Drawing from the preceding discussion, I now turn to the South African context and try to establish the state of affairs in the South African context as far as these paradigm wars are concerned. It must be stressed that this section is based on my own experience as an academic, having operated within the business-management space for more than 20 years. Currently, I am an associate professor at the University of Johannesburg as well as the managing editor of a management journal accredited by the South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). My opinions have been shaped by continuous conversation with fellow academic from all over South Africa as well as my experience gained during my seven-year tenure as journal editor.

In my opinion, the paradigm wars seem to have hit local shores slightly later than the 1980s as literature purports the situation to have been in (especially) the USA and Europe. Drawing from experiences as a young academic, business-management research in the 1990s was associated purely with quantitative methodologies. Only toward the end of the 1990s did qualitative research start to enter the discourse on how research should, and could, be conducted in the academic domain of business management. I have always been quite attentive to this debate as my formal education has not exclusively been within the realm of so-called 'economic and management sciences'. Although I completed a BCom, my postgraduate journey commenced down the path of the humanities, completing both a BA Hons and MA by the mid-1990s. My formal training in research methodology encompassed both quantitative and qualitative traditions, and my personal affinity lay with qualitative research. Indeed, my MA study was a qualitative one. After accepting a position as lecturer in business management, I continued to pursue an MCom, and I soon realised that an appreciation for the qualitative tradition did not exist in this field, and resultantly, my M.Com dissertation entailed a quantitative study.

Yet, despite this scenario, it must be emphasised that this situation, in my opinion at least, had changed by 2010, with a much greater appreciation in the academic domain of business management for the interpretive paradigm and associated qualitative methodologies. However, despite this increased appreciation for qualitative work, very little capacity had been created for qualitative scholarship. An exception seems to be in the field of human resources management where qualitative scholarship was on the increase as is evident from manuscript submissions to the journal I edit. The reason for the increase is that this journal had been gaining a reputation as a journal that sought to promote interpretive and qualitative research around that time.

As we now enter the latter half of the 2010s, it is apparent that the methodological tolerance eluded to in the previous section still abounds. However, it would seem as though an urgency exists to try and find some basis of cohesion for these two traditions to co-exist within the academic community rather than oppose each other. Although still in the minority, it is pleasing to see that the number of qualitative submissions at the journal I edit is slowly increasing. As many of these submissions are coming from traditionally quantitative scholars who are not yet sufficiently versed in the qualitative tradition, the rejection rate of these submissions is unfortunately very high. Be that as it may, this movement is evident of a willingness on the part of some South African scholars to create capacity in the realm of interpretive inquiry employing qualitative methods.

Adding CMS to the mix

My own scholarly journey has, as already mentioned, not been down the 'straight and narrow' commerce path. I have taken on postgraduate studies in the humanities, and after obtaining my PhD, I have embarked on three years of study in philosophy. During this time, my research interest also started shifting toward issues of morality in business, which found application in studies relating to corporate social responsibility and business ethics. My scholarly endeavour into moral issues surrounding business exposed me to the tradition of CMS, which has now become my chosen area of specialisation.

The discussion now turns to a brief introduction to CMS and its central tenets before venturing into the possibilities for CMS in the South African scholarly realm ofbusiness management and associated disciplines. This section will conclude by reflecting on the conditions necessary for CMS to gain a foothold within the academic domain of business management in South Africa.

A brief introduction to CMS

CMS is a relatively new development within the scholarly domain of business management. It is widely recognised that this movement assumed its identity and gained subsequent momentum with the seminal work of Alvesson and Willmott (1992; also see Grey 2004;

Learmonth 2007). However, it is also recognised that critical work relating to management and business practices did exist before Alvesson and Willmott's seminal work, especially in the body of knowledge dealing with labour-process theory (Anthony 1986; Clegg & Dunkerley 1977).

CMS draws upon perspectives such as neo-Marxism, labour-process theory, critical theory (most noticeably, Frankfurt School thinkers such as Habermas and Adorno), industrial sociology, post-structuralism and postcolonialism in an effort to direct critique against conventional business and management practice and knowledge creation (Alvesson, Bridgman & Willmott 2009; Dyer et al. 2014; Sulkowski 2013). It employs both non-empirical and empirical methodologies (exclusively qualitative) to incite radical re-evaluation and to encourage radical change where scholarship and practice exhibit the potential for exploitative practices or where the broader political-economic system renders those affected by the footprint of business powerless (Clegg, Dany & Grey 2011; Sulkowski 2013).

Drawing from its neo-Marxist influences, CMS challenges the potential for unequitable power relationships brought on by the dominant political-economic system, namely capitalism (Adler, Forbes & Willmott 2007). CMS scholars warn, for example, that the capitalist notion of wage labour exhibits vast potential for exploitative practices as inequitable relationships in bargaining power between forces of capital and labour render the notion of wage labour voluntary, a facade to subjugate the labour force.

CMS further posits that, through the global spread of capitalism and the mechanisms that support it (in the form of business organisations), the system has created institutions as well as institutionalised notions and practices to legitimise its success, often at the expense of local, indigenous and alternative systems of political economy (Deetz 1995; Harding 2003; Jack & Westwood 2006; Sulkowski 2013). This has resulted in a proliferation of consulting firms, business or management faculties, business schools and publications (Stewart 2009). This legitimisation has, in turn, resulted in the establishment of an ideology of managerialism, which is largely rooted in the success of the scientific method in business management. Accordingly, the academic discipline of business management rests upon this ideology of managerialism and the associated notion of scientism responsible for generating knowledge in support of the claims that managerialism presents (Kimber 2001; Stewart 2009).

Central tenets of CMS

Fournier and Grey (2000) suggest three principles that are central to CMS as tradition of inquiry. Although these 'principles' have grown synonymous with CMS as a scholarly tradition (Grey & Willmott 2005), some of them are, in themselves, contentious issues within the CMS community (Alvesson et al. 2009). The endeavour here is to introduce these principles but not to elaborate on the accompanying pros and cons in too much detail.

The first of the principles suggested by Fournier and Grey (2000) is that of denaturalisation. If one recognises that, as stated above, the dominant political-economic system has entrenched institutionalised notions of its own legitimacy and that this institutionalisation is pervasive, then it would stand to reason that this institutionalisation is not challenged but taken for granted as 'the way things are'. However, this does not necessarily mean that such institutionalised notions are just, fair or even morally acceptable. The principle of denaturalisation challenges these notions, especially if they have exploitative and morally questionable consequences. CMS, therefore, does not go along with the 'that's the way things are' or 'that's the way business goes' mind-set (Alvesson et al. 2009).

Secondly, Fournier and Grey (2000) suggest that CMS is a reflexive endeavour. In other words, it recognises that inquiry into management is advanced from the particular tradition to which its scholars ascribe and thus recognises the values which direct what is being researched as well as how it should be researched. CMS is sceptical of claims of universality and objectivity in management and posits that mainstream, positivist-oriented research in management exhibits weak (or even no) reflexivity. Reflexivity further implies that scholars and knowledge users should critically reflect upon the assumptions and routines upon which knowledge creation is based, irrespective of tradition, and must understand how culture, history and context influences knowledge generated through scholarly endeavour (Grey & Willmott 2005).

Fourier and Grey (2000) lastly suggest the principle of anti-performativity. This notion suggests that the outcome of the scholarly project in management should not necessarily further the enhancement of existing outcomes. The general yardstick against which new knowledge generated in management is evaluated is the practical value of such knowledge possesses, in other words, can such knowledge help make management a better process or practice. However, this approach means that the knowledge is still applied to further an ideology of managerialism. Anti-performativity suggests that new outcomes should be sought which do not necessarily fall within the parameters of mainstream managerialism. Anti-performativity is a contentious issue within the CMS community with strong arguments for and against it. However, as mainstream scholars point out there is no alternative in terms of these outcomes. This lack of viable alternative, yet again, speaks to the pervasiveness of the institutionalisation of the managerialist ideology. Anti-performativity, as an ideal, thus seeks to propose an alternative to the ideology of managerialism. How ambitious a project this is and what the probability is of achieving such an outcome is open to debate (Spicer, Alvesson & Kärreman 2009).

CMS, it would seem, is a radical and ambitious project that challenges deeply entrenched views about how management and business should be approached, not only from a practice point of view but also from a scholarly perspective. It reminds strongly of Socrates's 'radical discourse' and the Kantian notion of 'the world appears to me through the questions I ask.' The guiding principle, it would seem, is first to try to break down these deeply entrenched views and thereafter to reconstruct a view of business and management which is able to shed light on issues and challenges for which current managerialism might not always have the answers (Hancock & Tyler 2004).

Possibilities for CMS in South Africa

Of course, there needs to be value in introducing or making pervasive an alternative tradition to the study of business management in a particular setting. Business management seems very much to be an applied discipline where the practical application of knowledge generated is sought. It would therefore be reasonable to enquire as to what the benefit could be, for scholars and practitioners alike, of nurturing an alternative scholarly tradition such as CMS?

In my opinion, the most logical area for CMS to focus on in the South African context would be in terms of reviving indigenous knowledge and wisdom and searching for areas of integration of such wisdom into the management discourse. As a country that has been subject to more than 300 years of colonial subjugation and close to 50 years of apartheid rule, it is reasonable to posit that the local knowledge and wisdom of its people have been suppressed and have not been allowed to enter the 'mainstream' discourse, at least in the realm of business management as an academic discipline (Goldman 2013).

A simple look at 'South African' subject-matter textbooks in business management proves this point as these works are merely a collection of American or Western management principles which have been saturated with South African examples. The glaring flaw is that this literature is devoid of any uniquely South African knowledge, and at best, it only provides us with South African interpretations and applications of American or Western knowledge. This, in turn, reduces the educational endeavour in management to a mere perpetuation of the deeply entrenched institutionalised notions of managerialism.

I am of the opinion that CMS provides a lens through which South African knowledge and wisdom can actively be sought for the purpose of extracting South African perspectives on business management (Goldman, Nienaber & Pretorius 2015). The counter argument does exist that, if such knowledge did exist, it would have already been uncovered. However, I am not convinced by this argument. The agenda of managerialism is so firmly entrenched within the majority of scholars that the mere thought of a viable alternative cannot be conceived and is reduced to an exercise in futility. Yet, however romanticised it appears to be, it certainly needs to be attempted. If, through empirical inquiry, it appears that indigenous wisdom has nothing to offer to the discourse on business and management, then so be it. However, I would rather let scholarly inquiry prove this than allow ideological conviction to argue it.

Certainly, the South African context abounds with other issues that CMS can latch on to. As a tradition that seems to uncover unjust business and managerial practices and which sensitises against the misuse of power stemming from the legitimisation of ideological stances, CMS can potentially contribute to the discourse on management and business in the South African context (Goldman 2013).

Conditions necessary for CMS to gain momentum

It would be fair to assume that a specific climate needs to be prevalent for a new or emergent academic tradition to establish a foothold and gain momentum within a given milieu. Thus, one needs to establish which conditions need to be prevalent for CMS to start occupying a sound position within the academic space of business management in South Africa.

Various authors (Bernstein 1976; Fournier & Grey 2000; Hassard & Parker 1993; Locke 1996; Willmott 1993) point two the fact that two systemic issues have created a climate where the emergence of CMS is possible. I briefly expound on these below:

• The internal crisis of management: Locke (1996) purports that American managerial practices have been (and still are) seen as the yardstick against which management in the West is measured. However, he also points out that, after 1970, American management has increasingly been criticised as ineffective in the face of international competition. This resulted in a rise in popularity of (specifically) Japanese and German management principles at the expense of American principles. This has resulted in a shift in emphasis away from the 'bureaucratic administrator' towards the manager as an almost mythical figure, possessing a blend of charisma and codified rules transmitted through scientific training. This sanctification of the manager is also associated with more potential power and status centred in management, which has resulted in a fertile breeding ground for critical inquiry. Furthermore, the increased emphasis on looking for management wisdom further afield than only American management practices has resulted in a proliferation of management fads and fashions (fuelled, in part, by popular literature), which has made the vision of a stable, unified discipline not only more unrealised but (it would seem) unrealisable.

• The role of positivism in social science: The notion that social science should attempt to emulate the natural sciences in its methodologies and basic premises of aiming for the realisation of universally applicable principles has been a contentious issue at least since the 1950s (Winch 1958). Furthermore, Kuhn (1962) questioned the issue of objectivity in natural sciences, which marked a renewed interest in phenomenology and witnessed a fragmentation of social sciences into competing perspectives which marked the advent ofthe paradigm wars expounded upon earlier in this paper. Business management as an academic discipline has witnessed the gradual acceptance of non-positivist traditions, although still far in the minority. However, the basic premise is that a critical mass of scholars do exist for whom non-positivist traditions seem to be ontologically more attractive.

Given the nature of the academic discipline of business management (and related disciplines) as a social science, as much as it is an economic science, that operates in an increasingly fragmented epistemological domain and bearing in mind that the South African context is one that is heavily influenced by the legacy effects of both colonialism and apartheid, it would appear as though the climate in the academic domain of business management is susceptible for the introduction of CMS as an alternative tradition for the study of business management.

Methodology employed

From the literature review, it would seem that the academic domain of business management as a field of inquiry could be susceptible to the introduction of CMS as an alternative tradition of enquiry. In the rest of Chapter 7, I aim to employ empirical means to concretise this notion. Thus, the research question that the chapter endeavours to answer can be stated as follows: 'How susceptible is the academic domain of business management in South Africa to CMS?'

To answer this research question, the study aims to achiever the following:

• Assess the level of familiarity with CMS amongst South African business-management academics.

• Develop an understanding of the nature of the climate within the academic domain of business management with a view to introducing CMS as an alternate tradition for the study of business management.

As the aim of this study implies exploratory research, the study espoused an interpretive point of view, employing qualitative research methods. The research population comprised senior, full-time academics operating within the academic domain of business management and related disciplines at South African state-funded universities. Non-government funded higher-education institutions or private universities were not included in the study as these institutions are traditionally more focused on teaching than on research. 'Senior academics' refer to academics on the levels of senior lecturer, associate professor and full professor. The decision to focus on senior academics was borne from the relative newness of CMS. As it is not part of the mainstream thinking on business management, the probability is greater that senior, more experienced academics would have come into contact with the notion of CMS. For purposes of this study, 'business management and related disciplines' refer to academic areas of inquiry where business management is the common denominator. This would therefore include areas such as business management, hospitality management, human resources management, knowledge management, marketing management, project management, strategic management, small-business management and entrepreneurship, supply-chain management and logistics, and tourism management. Thus, senior academics working in these areas in South Africa constituted the research population for this study.

As this research is exploratory and deals with peoples' familiarity with CMS as well as peoples' views on the climate within the discipline of business management, a qualitative-survey design was adopted. The study was envisaged to employ a two-staged data collection process, and each of these stages employed its own sampling procedure:

• Stage one: This stage involved a relatively simple qualitative survey of selected research subjects concerning their familiarity with the field of CMS. One hundred academics were sourced, 88 of whom were known to me. The remaining 12 were 'cold canvassed' to ensure a relatively even spread across institutions and related disciplines of management. Thus, the sample was selected on a judgmental basis.

• Stage two: Resultant from the first stage, a number of people would be selected from the initial sample of 100 to share their views on the current climate within the discipline of management and related disciplines in the form of either a semi-structured interview or a reflective essay. Participants were given the choice due to the fact that the sample is geographically dispersed. Furthermore, time constraints and workload pressure could also prevent people from meeting with me for an interview. The exact number of people to be selected could not be established until the conclusion of stage one as this number would be dependent on the response rate in stage one and the nature of responses received. Ideally, I would have liked to approach in the vicinity of 30 people with a relative spread from those familiar with CMS to those not that familiar with it and those who have no knowledge of CMS at all. I decided that I would use a combination of judgmental and theoretical sampling techniques to select participants at the conclusion of stage one.

For stage one, research subjects were simply asked via email if they were familiar with critical theory in the academic inquiry into business and management as the purpose here was simply to establish level of familiarity with the concept. Stage one employed a more thorough soliciting of data from research participants. As the majority of people indicated that they would be writing a reflective essay, a briefing document was prepared outlining the aim of the research and stating four questions upon which participants had to reflect. These questions were also used as an interview guide for those participants who chose to conduct an interview. As stage two also wanted to include those unfamiliar and not so familiar with CMS, the questions were not CMS specific but rather sought to solicit opinions concerning the climate of business management as an academic discipline and opinions concerning non-positivist methods of inquiry.

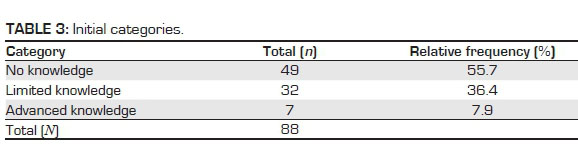

Data analysis for this study also differed in the two stages outlined above. In stage one, a simple categorisation of responses were employed. Responses were categorised in three categories, namely those with no knowledge of CMS, those with a basic knowledge of CMS and those with more advanced knowledge of CMS.

The differentiator between basic knowledge and advanced knowledge was the level of engagement with CMS. Those responses that indicated formal schooling in CMS on post-graduate (masters or doctorate) level as well as those responses indicating research publications (journal articles or conference proceedings) within the CMS space were deemed as falling into the category of 'advanced level'. This categorisation resulted in a frequency distribution indicative of familiarity of South African management academics with CMS.

For stage two, the interviews and reflective essays would be analysed by employing qualitative content analysis. More specifically, the method of coding proposed by Creswell (2003) was followed, using the questions posed in the briefing document as a coding scheme. Creswell's (2003) process for conducting qualitative data analysis entails four steps, namely:

1. Organise and prepare data: Reflective essays have the advantage that the data is already transcribed. For those participants who opted to conduct an interview, the recorded data were transcribed onto Microsoft Word. The transcription was typed at the completion of each interview and not at the end of all of the interviews.

2. Read through all data: All transcripts were read to gain an overall understanding of the views of research participants. Data were classified and grouped according to the four questions posed by the briefing document.

3. Begin a detailed analysis with a coding process: In this step, the emphasis shifted from describing to classifying and interpreting. This is where the coding process took place, utilising the following procedure:

ο Each cluster of data was viewed in turn, constantly searching for sub-themes that might arise from each ofthe four broad categories.

ο Sub-groups were scrutinised to see whether they could be viewed as a stand-alone theme or whether they could be collapsed into a stand-alone theme with other sub-themes. ο Relationships between themes and sub-themes were then sought to develop a 'big picture' of the nature of the climate of the academic space of business management.

4. Use a coding process to generate a description for the case study: This step displays the generated data, based on the themes appearing as major findings of the study. This was performed by interpreting what the data uncovered. This interpretation was based on the understanding that was derived from the collected data.

Findings from the study

The qualitative survey for stage one was conducted between August and September 2015. During this period, some participants referred me to colleagues who they thought might be familiar with CMS. These referrals amounted to eight in total. I decided to include them in the sample as it became apparent very early on that very few people fell into the 'advanced knowledge' category. From the 108 academics targeted at 16 higher-education institutions, 88 responses (81.5% response rate) were received. The outcome of the initial categorisation can be seen in Table 3.

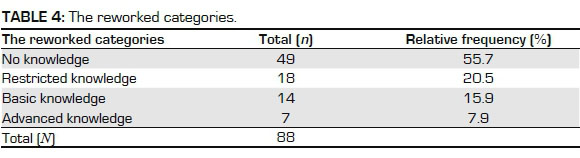

It became apparent that the 'limited knowledge' category needed to be divided into two categories as responses indicted a polarisation of responses here. On the one hand, some people had either heard of CMS or indicated in their responses that they did not know much about the topic. These responses were categorised as 'restricted knowledge' (see Table 4). On the other hand, there were responses that indicated that people had some knowledge, but they did not profess to have an advanced level of knowledge about CMS. These responses were categorised as 'basic knowledge'.

The qualitative survey for stage two ran from September 2015 to November 2015. From the responses of the qualitative survey in stage one, a target of 40 people were selected for stage two, of which:

• 7 people were from the 'advanced knowledge' category

• 16 were from the 'restricted' and 'basic knowledge' categories

• 17 people were from the 'no knowledge category.

Contact was established with all 40 research subjects. Four of these potential research subjects indicated that they were not willing to participate. Of the 36 remaining potential research subjects, data was eventually gathered from 21 research subjects. Of these 21 participants, semi-structured interviews were conducted with three people and self-reflective essays were gathered from the other 18. The research respondents emanate from 12 South African universities and universities of technology, with six senior lecturers (all with doctoral qualifications), six associate professors and nine full professors participating in the qualitative survey in stage two. In terms of familiarity with the concept of CMS, the group was constituted as follows:

• Four research subjects were from the 'advanced knowledge' category.

• Nine research subjects were from both the 'restricted' and 'basic knowledge' categories.

• Eight research subjects were from the 'no knowledge' category.

An attempt was made to apply coding to sentences, but it was soon realised that coding would be more expedient if applied to central ideas contained in multiple-sentence clusters. After initial coding, a total of 36 categories were identified in the data. Further passes through the data and scrutiny of the interrelationships between these categories resulted in the emergence of five themes central to understanding the prevailing climate in the South African academic domain of business management as well as the role CMS can fulfil in this area. Each of these five themes will now be presented and discussed in turn.

However, before I expound upon the themes, it is important to note that research participants, especially those who had no knowledge of CMS prior to being involved in this research, embarked upon some basic reading on CMS literature to be in a position to meaningfully contribute to the research. Nine of the research participants explicitly stated this in their feedback, and this included five research participants that were categorised in the 'no knowledge' category.

Theme 1: Paradigmatic dominance

The majority of the research subjects were very vocal in their view that the academic field of business management in South Africa is characterised by the distinct paradigmatic dominance of the positivist tradition. A total of 11 of the research participants directly referred to positivism as the dominant research paradigm in business management in South Africa. Although the rest of the participants did not directly refer to positivism as the dominant paradigm, it was clear from the views expressed that they felt that quantitative methods dominated in the academic discipline of business management. Peripheral to the above, the sentiment was expressed that positivism cannot adequately address pressing challenges that are emerging in the domain of business management, specifically in South Africa. In this regard, participants cited that positivism cannot adequately address issues such as complexity, hyper change and the so-called 'dark side' of management. Only one of the research participants did not feel that quantitative methods stemming from a positivist paradigm dominated the business management discourse in South Africa. The following excerpts from interviews and self-reflective essays underscore these sentiments:

'Absolutely, we need to counter the dominant positivistic approach with qualitative and critical inquiry.' (P3)

'We are currently dealing with a paradigmatic dominance of empirical practice where there is little offered as an alternative.' (P13)

'I find the space, certainly from a KwaZulu-Natal perspective, overly positivist, both in the way we teach our students to the ways in which we conduct our research. There is a veneration of the "scientific" method over other methods and epistemologies.' (P14)

'This paradigm is however not the one that business-field academics and students are used to practice in South Africa. Here the emphasis is on positivistic studies of a quantitative nature.' (P16)

These views on the dominance of the positivist paradigm also lead research participants to cite issues associated with this perceived paradigmatic dominance. Firstly, they expressed the view that the dominance of a particular paradigm leads to a situation where limited space is provided for alternative views and methodologies. The sentiment was expressed that positivism often fails to recognise its own limitations, and as such, it is oblivious to its own shortcomings, which in turn creates a situation where alternative views are frowned upon as being biased and unscientific. Seven of the research participants explicitly stated that a domain typified by such a paradigmatic dominance does not bode well as it stifles innovation of thought. They were of the view that different research paradigms should actively be promoted. Secondly, this apparent paradigmatic dominance has a marked effect on publication and publication possibilities. There was a strong sentiment amongst research subjects that most South African business-management journals were markedly positivist and that their editorial policies left very little leeway for alternative methodologies. The following annotations provide support to the findings provided above:

'Most journals in South Africa are explicitly positivist in orientation.' (P13)

'Academics and students would require some form of acceptance if they are working in this domain as it is very difficult to get published in this field in South Africa.' (P16)

'It is difficult to publish qualitative work and virtually impossible to publish critical work in this country. Most journals simply do not cater for anything other than quantitative papers.' (P21)

'Management research tends to side-step complexity neatly by taking a positivistic stance, which then leads the dominant discourse of predict, exploit and control.' (P14)

Theme 2: Diminishing returns prevalent in knowledge production

This theme seems to be a function of the paradigmatic dominance that seems to prevail within the scholarly business-management community.

Fifteen of the 21 research participants were quite vociferous in pointing out that research practices and methodologies prevalent in the domain of business management are delivering questionable results as far as the creation of new knowledge is concerned. There was a strong sentiment from research participants that this situation was, in part, due to a seemingly pervasive practice ofproducing research that seems statistically very impressive but tends to add little in the way of practical value beyond that which is self-evident. Thus, the critique here is that much of the business-management research output seems to be driven by a desire to impress the editors and reviewers of journals with intricate statistical analyses rather than by a desire to primarily produce research output that has great practical significance. The following quotations taken from interviews and self-reflective essays support these findings:

'In my opinion, and based on my research, far too much research seems to be aimed at mindless production of statistical work, with conceptual works few and far between. Where is the brave conceptual engagement with ideas? Hiding behind a statistical barrage of work has perhaps become a norm; yet it is clear that the simple act of abstracting complex phenomena into linear relationships for statistical testing is in many instances suspect; and this is not typically acknowledged by authors.' (P1)

'We merely engage in theory validating research using questionnaires with no deep empirical or theoretical contribution to management studies and its allied disciplines.' (P14)

'Researchers in the field of marketing are mainly dominated by replication studies and no or limited new knowledge are therefore developed.' (P6)

'Increasingly papers are published dealing with highly sophisticated methods of empirical analysis. Yet the output forthcoming from these works is mostly boring and self-evident. Arguably it seems therefore that the field of management science is one where more and more is said of less and less.' (P13)

Furthermore, there was also a strong sentiment amongst research participants that the dominant positivistic thinking and its associated quantitative methodologies lead to nothing more than a rehashing of that which is already known. In other words, more and more research output is forthcoming that deals with the same issues over and over. The feeling is that this scenario leads to no innovation, creativity and rejuvenation of thought. The major critique forthcoming from research respondents here is that scholars continuously draw from the same literary base to formulate hypotheses, research propositions and research questions that are tested in different contexts. However, this literary base itself is not challenged and reshaped through constructive discourse, which gives rise to a scenario where the same things get done over and over again, so to speak. The table below provides excerpts from the interviews and reflective essays that support the findings presented above.

'I question whether we are just really adding to the body of knowledge, or just contextualising what we already know.' (P4)

'In my perceptions, most research focuses on testing models empirically that adds very little to new knowledge'. (P19)

'However, my perception is that we mostly "re-hash" existing theories and follow the correct steps to finish that PhD or the research without taking the real knowledge creation into account.' (P8)

'Surely there is a huge need for academics and students to perform qualitative and critical enquiry in management - it is important that both groups can think creatively, reflectively and critically.' (P16)

Theme 3: Institutional pressures of publication

Again, this theme seems to stem directly from the sentiments prevalent in terms of knowledge production practices in the domain of business management in South Africa. The overwhelming sentiment echoed by research participants here was that, although many businessmanagement academics would like to think that their research efforts have vast practical application, the reality of the matter is that academics are driven by a need to publish rather than by a need to address societal issues insofar as issues of business management are concerned. Institutional pressure from universities as employers has resulted in academics chasing numbers of articles published and Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) credits obtained in order to fulfil performance as contractually determined by key performance areas (KPA) rather than the societal and organisational utility of their research endeavours. This seems to be the epitome of the 'publish or perish' phenomenon. Some of the research participants - four in total -felt very strongly that this situation is resulting in no new and useful knowledge being produced in the broader domain of business management. The following quotations bear witness to these sentiments:

'Although I enjoy the research projects I work on, I often ask myself how is my research adding value, am I solving the real issues at hand, contributing to business success, solving societies problems, in most cases my answer is no not really ... but I need outputs so I keep doing more or less the same research using the same methods.' (P4)

'The quantity of research output has increased but I have serious doubts as to the quality and practical impact of such research.' (P14)

'In my perception, most researchers think their research has practical application while that may not be the case in practice.' (P15)

'So we may develop academic research knowledge, but it is of no benefit to business.' (P11)

'In most instances, our research is not addressing industry challenges because as academics we are trying too hard to tick the boxes to get published. It is a publishing and funding game and not a humanitarian game of how we as academics in management can support or assist management and leaders in industry.' (P10)

Some research participants also pointed out that a consequence of the scenario outlined above is that the chasm that already exists between academia and industry just grows wider and wider as industry tends to view academic research as far too theoretical and not dealing with the issues relevant to industry. Although it is surely true that academia alone cannot be expected to bear the full brunt of the blame for this distance that exists between itself and industry, it is not doing itself any favours by pursuing a research agenda that is not aligned with the needs of businessmanagement practice. The quotations below provide support for the abovementioned findings:

'There are not really other platforms where researcher findings are shared to non-academics as most business-research conferences are attended by academics only.' (P11)

'In South Africa, the level of trust and cooperation between industry (and by the way, government too) is generally low. For example, I am not aware of many areas in the economic and management sciences where industry and government have actually commissioned major research to universities. Again, in spite of the need for board members, I am also not aware of many academics who are invited to sit on boards of companies. Also, it remains very difficult for researchers to be allowed access to companies to conduct meaningful research. Generally, researchers battle to get permission, making it very difficult to get good samples for publication in leading journals internationally. Without such robust research, it is hardly possible to contribute to addressing industry challenges.' (P12)

'Unfortunately not in the management sciences. We are all "playing the game" and writing for each other. As someone who spent more than a decade in industry, it is still shocking to me how irrelevant South African academics' research (specifically in our discipline and probably many other in management sciences) is.' (P9)

'I don't think we are publishing articles that are actually helping industry or that [are] of value to them. It's not relevant to them. At the same time, academics are not always interested in the issues that are really of concern to industry. So somewhere we keep on missing each other.' (P20)

Theme 4: Creating space for interpretive and critical inquiry

It is not surprising, based on the paradigmatic dominance perceived by research subjects, that there was a feeling that it would be in the best interest of business management as a field of academic enquiry to create space for alternative research paradigms and ways of thinking. In fact, all but one of the research participants expressed such sentiments. As it appeared that research participants felt that positivism and associated quantitative methodologies could not adequately address contemporary challenges within the domain of business management, they expressed the need for other paradigms to be encouraged and explored. The following sentiments were expressed by research subjects in support of this finding:

'Yes, space is needed for CMS in South Africa, if not more so than in developed contexts.' (P1)

'There is definitively a need for critical management studies or critical theory in management studies. For example, small businesses fail, they have been failing for years and unless the system in which they operate and the assumptions held is changed radically or approached differently, they will continue to fail in the future.' (P4)

'Yes, there is a definite need and space for qualitative and critical inquiry in all areas of management, especially in my domain of marketing management as quantitative research are [sic] no longer sufficient to understand consumer behaviour.' (P6)

'There is definitely a need for qualitative and critical inquiry in management.' (P12)

'Yes, we definitely need a space for CMS in SA. It will elevate what we do, and in a sense, we are living in the perfect country to engage with this kind of research and adopt this kind of philosophical approach.' (P14)

Specifically, research participants expounded that, although interpretive work had increased in the field of business management in South Africa, it still represents a minority that is struggling to gain a substantial foothold in the business-management discourse in the country. They were also of the opinion that CMS, which is largely unfamiliar to South African business-management scholars, holds great potential to address some of the issues that the dominant, positivist paradigm could not adequately address, and it was felt that space should consciously be created for CMS within the academic domain of business management in South Africa. Research participants expressed particular views on how this could be established. These included the following:

• Incorporating CMS as part of the business-management syllabus, thereby creating awareness of this paradigm amongst students and also forcing academics to familiarise themselves with the basic principles of CMS.

• Securing a public platform for CMS at national scholarly businessmanagement conferences such as the annual Southern Africa Institute for Management Scientists (SAIMS) conference. Participants expressed the explicit view that a 'showcase' session at this conference could help in establishing a critical mass of CMS scholars.

• South African management journals adapting their editorial policies to encourage more manuscript submissions of a critical orientation (as well as more interpretive submissions).

The following extracts from interviews and reflective essays support the abovementioned findings:

'Therefore, to answer the question, is there space for CMS in South Africa and in the syllabi of business managers? The answer is YES. This is a serious academic field of research because scholars in management face some challenges. The high demands of the AMCU trade union in platinum and gold mines in South Africa the last three years is probably a good example of extreme power play, something the modern business is not used to. The complexity of the social environment is brought to the surface, and the real power of different role players now really starts to sink in.' (P15)

'I think it would be a good idea to include CMS in our curriculum. The question is just, "where"? I do not think undergraduate is necessarily the right place for it, but I think we need it.' (P21)

'I would suggest that students should be exposed to any and all theories that would engage their minds and help them become serious thinkers.' (P18)

'However, the biggest challenge is to educate researchers and students on how to be critical and have critical thoughts.' (P4)

'I do believe, however, that South African management scientists should be made more aware of the idea of CMS, and opportunity for debates should be created (SAIMS) as the more exposure people have and the awareness that is created, the more people question and challenge the status quo.' (P4)

'Absolutely, but it will require an academic space - which is to say that at least one serious SA management journal and its editors must create such a space and invite debate within the area. Teaching academics and students the critical skills derived from the Marxist-structuralist tradition (inter-alia) will provide the means to better focus the lens of scrutiny on the key problems confronting SA.' (P13)

'Journal editors need to understand this type of work [interpretive and critical work], and they need to have reviewers that can evaluate it bias free.' (P20)

Theme 5: The possibilities of critical management studies

All research participants expressed their opinions on what CMS could contribute to the academic discourse on business management in South Africa. More often than not, these possibilities were sketched against the backdrop of the perceived deficiencies and weaknesses of the dominant positivist paradigm and associated quantitative methods. Therefore, this discussion will assume the same guise by first presenting research participants' critique against positivism and thereafter continuing to opine how CMS can fill these perceived voids.

Research participants voiced the following critique against the dominant positivist paradigm prevalent in the academic domain of business management in South Africa:

• It does not seem to address pressing issues emerging from the business environment. Research participants specifically pointed out that positivist discourse seemed to sidestep issues such as complexity, hyper-change and exploitation and inequality brought about by questionable business practices. Research participants were of the opinion that CMS, due to its scepticism of any type of dominant ideology and structural dichotomies, would be more attuned to such pressing issues and be able to give prominence to them in the academic business-management discourse.

'Adopting a critical stance in all management theory and practice can ensure that power relationships and exploitative conditions are mediated by values.' (P1)

'I use this paradigm in studies where I illuminate that organisations dominate (power) and exploit (top-down approach) instead of being a good citizen. We no longer live in the dark ages; employees are competent to contribute their competence but are hardly afford the opportunity to do so.' (P10)

'As such there is clearly a need to look at society and management through a different lens and to challenges the way we do things and the way we think.' (P4)

'A critical approach thus "unmasks" inequalities in relationships, questioning the privileging of "having", that is consuming, over "being" and relatedness to the world. However, it is challenging to accept that marketing scholars avoid these issues in their research, and my venture would be that it is largely driven by some higher level societal process.' (P7)

• Mainstream business-management thinking does not take due cognisance of the social issues and social agenda that have started to pervade the business-management discourse in recent times. Conventional mainstream business management promotes the notion of managerialism and as such focusses on the needs of the business more than it does on the needs of organisational stakeholders. Research participants are of the opinion that CMS can promote the interests of stakeholders in knowledge production more than the mainstream can.

'Only through embedding humanist and robust values that are critical to power abuse and inequality within the student-management cohort, year after year, can we affect societal change and shape a more humane society.' (P1)

'Especially from a South African perspective, we need to find alternatives to everyday problems. The plight of ordinary people is often neglected, and CMS could hold the answer. CMS necessitates a rethinking of our role in alleviating the problems associated with the problems experienced by modern society.' (P17)

'You need to be evolutionary in your approach, pragmatic in your behaviour, engaged to broaden the parameters of society, understand the importance of the human factor in life/business, learn the proper tools that help you to create successful businesses, believe that there is no one model of how to run a business and that there are alternative approaches to run a business.' (P15)

'In my opinion, CMS will challenge industry practises rather than address industry needs.' (P3)

• The dominant positivistic thinking is not contemplative enough of the inequalities and divisive realities that seem to be associated with capitalism. Positivism assumes that capitalism, as a political economy, is the ideology of choice in terms of progress and the betterment of society as a whole. Research participants felt, however, that CMS forces introspection and greater sensitivity towards inequality and exploitative practices as it has no allegiance with capitalist ideology. In fact, CMS is sceptical of capitalism as an 'ultimate and infallible' system that represents progress and prosperity.

'First, critical inquiry helps us to constantly question ourselves and reflect about our assumptions and worldviews of organisations, their role in society and the role of society in organisations.' (P12)

'The big concern is about the social injustice and environmental destructiveness of the broader social and economic systems that managers and firms serve and reproduce. Effective managers do not just apply traditional management tools but also need to reflect more critically about their role in management and society.' (P15)

'It is the objective of businesses to satisfy needs; on the contrary, the needs of stakeholders (and more specifically that of owners) appear to receive preference. The socially divisive and ecologically destructive systems in which we operate and within which managers work are evidence hereof. CMS forces everyone involved to rethink their current role in satisfying needs.' (P17)

'Hence, it is about getting things done as opposed to what is morally right. The key problem with a focus on efficiency and effectiveness is that it allegedly marginalises questions pertaining to the interaction between marketing and society.' (P7)

Resultant from this apparent lack of contemplation, research participants were also of the opinion that positivism does not allow much room for opposing points of view and therefore stifles academic debate and innovative thought as it only entertains notions that support and perpetuate it. As CMS is critical of positivism, it allows scope to debate and interact with points of view that represent various positions within the broader academic domain of business management. The following quotes provide evidence in support of this finding.

'It investigates the "other side of an argument" and as such is different from mainstream research because it challenges the status quo.' (P10)

'It requires reconsidering current structures, thoughts [sic] processes, approaches, economic, political and managerial behaviour, our understanding of the true meaning of sustainability as well as the way in which we assume factors of production should be distributed. Our major responsibility could be to stimulate and facilitate conversation on our understanding of concepts such as feminism, anarchism, communism, green thinking and so on.' (P17)

'Critically reflecting on the nature of management. This is to ongoing ask yourself: "Am I doing the right thing, and what I am doing, is it effective and efficient?"'. (P15)

'Yes, there are limits to positivistic thinking and methods. There is also a void in terms of management theory to deal with issues of complexity.' (P2)

Conclusions and recommendations

From the findings presented above, the following is evident:

• The academic domain of business management in South Africa is dominated by positivist thinking with knowledge production taking a predominantly quantitative guise.

• This dominance leaves little room for alternative epistemologies and, resultantly, provides very few opportunities for qualitative, critical and conceptual work to be published in South African journals.

• The overreliance on quantitative methodologies is creating a situation where research outputs deliver little in the form of genuinely new knowledge. Instead, business-management scholarship in South Africa seems to be typified by restating what is already known.

• Institutional pressure to publish is, at least partially, responsible for academics reverting to the 'tried and tested' avenue of getting published. This means that they are not being afforded the freedom to explore other epistemologies and paradigms as this would imply longer time frames to get published initially.

• The 'relevance vs. research' gap, that is, the gap between academia and industry, is widening, and both industry and academia tend to operate in distinct silos.

• There seems to be a need to create more space for and capacity in alternative methodologies. This is not tantamount to a revolt against positivism and its preference for quantitative methodologies. Rather it is a call to encourage innovative debate in the domain of business management.

• The shortcomings cited against positivism can be addressed by other epistemologies, and CMS has the potential to engage with some of the pressing issues arising from the South African context.

If one refocuses on the research question posed in this study, namely 'How susceptible is the academic domain of business management in South Africa to CMS?', the findings suggest that the answer to this question can be interrogated at numerous levels:

• On an individual and personal level, it would seem that the majority of South African business-management academics concede that the paradigmatic dominance of positivism has certain pitfalls which necessitates different views and approaches to business-management teaching, research and practice. Thus, at the individual level, the answer to this research question is that academics seem very susceptible to the notion of CMS and other epistemologies that challenge the pervasiveness of the dominant, positivist paradigm.

• However, on an institutional level, that is, at the level of a businessmanagement department as a whole or at any given university, workload pressure and the pressure to publish tend to force people to 'stick to what they know' and perpetuate tuition and research practices that have been followed in the past. The concern is that developing new curricula or climbing the learning curve of a new research paradigm consumes much effort and time, which academics cannot afford in the contemporary higher-education environment. On this level, thus, the answer to the research question seems to be a conditional one. People would be willing to explore CMS but not at the expense of the objectives their work environments place upon them.

• Also, on a scholarly society level, that is, at the realm of businessmanagement journals and conferences, findings seem to indicate that the scholarly community is not necessarily susceptible to alternative epistemologies as evidenced by the editorial policies and practices of South African business-management journals. Due to the pervasiveness of positivism and quantitative methods amongst South African business-management academics, review panels of journals do not always possess the expertise to be able to review submissions of a CMS nature.

To summarise, it would seem that individual academics are susceptible to the notion of CMS and other alternative epistemologies but that there are institutional barriers that limit the proliferation of capacity in and spaces for alternative epistemologies such as CMS. Although there seems to be individual efforts and incremental progress in terms of creating capacity and space, there seems to be a lack of coordinated effort to make significant inroads in this regard.

Although it is recognised that this was a very modest study that set out to answer a very simple question, it has uncovered some interesting facets ofthe nature ofthe domain ofbusiness-management scholarship in South Africa. It is evident that academics overwhelmingly feel that alternative epistemologies such as CMS need to have space within which they can develop in order to contribute meaningfully to the South African business-management discourse. As scholars, we always point out to our students that the business environment is constantly changing and evolving and that business needs to keep up with the challenges laid down by these changes. In the same vain, as academics we also need to realise that higher education is changing, and this change often has more far-reaching implications than we wish to accept. In keeping with this change, academics need to constantly adapt their efforts in terms of both tuition and research to remain relevant and useful.

References

Chapter 7

Adler, P.S., Forbes, L.C. & Willmott, H., 2007, 'Critical management studies', The Academy of Management Annals 1(1), 119-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/078559808. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M., Bridgman, T. & Willmott, H., 2009, The Oxford handbook of critical management studies, Oxford University Press, London. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M. & Willmott, H., 1992, 'On the idea of emancipation in management and organization studies', Academy of Management Review 17(3), 432-464. [ Links ]

Anthony, P., 1986, The foundation of management, Tavistock, London. [ Links ]

Bernstein, R., 1976, The restructuring of social and political theory, Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Buchanan, D. & Bryman, A., 2007, 'Contextualising methods choice in organizational research', Oranisational Research Methods 10(3), 483-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1094428106295046. [ Links ]

Cameron, R. & Miller, P., 2007, 'Mixed methods research: Phoenix of the paradigm wars', Proceedings of the 21st Annual Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) Conference, Sydney, 04-07th December 2007. [ Links ]

Clegg, S., Dany, F. & Grey, C., 2011, 'Introduction to the special issue critical management studies and managerial education: New contexts? New agenda?', M@n@gement 14(5), 271-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.3917/mana.145.0272. [ Links ]

Clegg, S. & Dunkerley, D., 1977, Critical issues in organizations, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Creswell, J., 2003, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Deetz, S., 1995, Transforming communication, transforming business: Building responsive and responsible workplaces, Hampton Press, Cresskill, NJ. [ Links ]

Denison, D.R., 1996, 'What is the difference organizational culture and organizational climate? A native's point of view on a decade of paradigm wars', The Academy of Management Review 21(3), 619-654. [ Links ]

Denzin, N.K., 2010, 'Moments, mixed methods and paradigm dialogs', Qualitative Inquiry 16(6), 419-427. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364608. [ Links ]

Dyer, S., Humphries, M., Fitzgibbons, D. & Hurd, F., 2014, Understanding management critically, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Flick, U., 2002, An introduction to qualitative research, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Fournier, V. & Grey, C., 2000, 'At the critical moment: Conditions and prospects for critical management studies', Human Relations 53(1), 7-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726700531002. [ Links ]

Goldman, G.A., 2013, 'On the development of uniquely African management theory', Indilinga African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems 12(2), 217-230. [ Links ]

Goldman, G.A., Nienaber, H. & Pretorius, M., 2015, 'The essence of the contemporary business organisation: A critical reflection', Journal of Global Business and Technology 12(2), 1-13. [ Links ]

Grey, C., 2004, 'Reinventing Business Schools: The contribution of critical management education', Academy of Management Learning and Education 3(2), 178-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2004.13500519. [ Links ]

Grey, C. & Willmott, H., 2005, Critical management studies: A reader, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Guba, E. & Lincoln, Y., 2005, 'Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences', in N.K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research, pp. 105-117, Sage, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Hancock, P. & Tyler, M., 2004, '"MOT your life": Critical management studies and the management of everyday life', Human Relations 57(5), 619-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726704044312. [ Links ]

Harding, N., 2003, The social construction of management, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Hassard, J. & Parker, M., 1993, Postmodernism and organisations, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Jack, G. & Westwood, R., 2006, 'Postcolonialism and the politics of qualitative research in international business', Management International Review 46(4), 481-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11575-006-0102-x. [ Links ]

Johnson, R.B. & Onwuegbuzie, A.J., 2004, 'Mixed-methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come', Educational Researcher 33(7), 14-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014. [ Links ]

Kuhn, T., 1962, The structure of scientific revolutions, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Kimber, M., 2001, Managerial matters: A brief discussion of the origins, rationales and characteristics of managerialism, pp. 03-45, Australian Centre in Strategic Management and Queensland University of Technology School of Management, Working paper no 52, Brisbane. [ Links ]

Learmonth, M., 2007, 'Critical management education in action: Personal tales of management unlearning', Academy of Management Learning & Education 6(1), 109-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2007.24401708. [ Links ]

Locke, R.R., 1996, The collapse of the American management mystique, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Mingers, J., 2004, 'Paradigm wars: Ceasefire announced, who will set up the new administration', Journal of Information Technology 19(3), 165-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000021. [ Links ]

Neuman, W., 2006, Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, Pearson, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Oakley, A., 1999, 'Paradigm wars: Some thoughts on a personal and public trajectory', International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2(3), 247-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/136455799295041. [ Links ]

Shaffer, D.W. & Serlin, R.C., 2004, 'What good are statistics that don't generalize?' Educational Researcher 33(9), 14-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033009014. [ Links ]

Spicer, A., Alvesson, M. & Kärreman, D., 2009, 'Critical performativity: The unfinished business of critical management studies', Human Relations 62(4), 537-560. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726708101984. [ Links ]

Stewart, M., 2009, The management myth: Debunking the modern philosophy of business, WW Norton, New York. [ Links ]

Sulkowski, L., 2013, Epistemology of management, Peter Lang, Frankfurt-am-Main. [ Links ]

Teshakkori, A. & Teddlie, C., 2003, Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Terrell, S.R., 2012, 'Mixed-methods research methodologies', The Qualitative Report 17(1), 254-280. [ Links ]

Waite, D., 2002, '"The paradigm wars" in educational administration: An attempt at transcendence', International Studies in Educational Administration 30(1), 66-80. [ Links ]

Willmott, H., 1993, 'Strength is ignorance; slavery is freedom: Managing culture in modern organizations', Journal of Management Studies 30(4), 515-552. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1993.tb00315.x. [ Links ]

Winch, P., 1958, The idea of a social science, Routledge, London. [ Links ]