Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Commercii

On-line version ISSN 1684-1999

Print version ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.16 n.2 Johannesburg 2016

http://dx.doi.org/l0.4102/ac.v16i2.412

CHAPTER 4

Decolonising management studies: A love story

Shaun D. Ruggunan

Human Resources Management Department University of KwaZulu-Natal South Africa

SUMMARY

Chapter 4 offers an auto-ethnographic account of my work as a lecturer in human resources management during a pivotal moment in South African higher education. Chapter 4 posits that any engagement in a critical-management studies project in South Africa needs to acknowledge the politics of knowledge production. Chapter 4 suggests three ways forward for a CMS project. The first is to engage in critical historiographies of South African management studies and its allied disciplines. Such exercises unpack the ways in which disciplinary knowledge is produced over time and challenge the view of management-studies knowledge as universal and apolitical. The second is to engage in a management studies for publics, as opposed to a management studies for professional mobility or a management studies for a managerialist public only. This helps democratise the curriculum and research agendas and encourages more critical public-intellectual activities from within the field. Thirdly, management-studies academics need to re-imagine the discipline through the lens of a sociological or social-science imagination which is inherently a critical and reflexive imagination. These three strategies for change will influence pedagogy, research and practice. To advocate for these changes is an act of resistance, emancipation and love.

Introduction

The aim of Chapter 4 is to provide an auto-ethnographic account of my work as an academic working in human resources management at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), South Africa. It describes and critically reflects my conscientisation in becoming a critical-management scholar within the mainstream school of management studies located in the UKZN college of Law and Management. This personal account is situated within the larger political-economic experience of South African higher education. With Chapter 4, I hope to make two contributions to scholarship in critical-management studies. Firstly, I provide an account by a South African, who has always lived and worked in South Africa. Most of the empirical and theoretical work in critical-management studies in South Africa is dominated by Nkomo in her sole authored work (1992, 2011) and in her work with others such as Jack et al. (2008), Nkomo et al. (2009) and Alcadipani (2012) even though she may not always explicitly label it as CMS. In her 2011 article on a postcolonial and anti-colonial reading of 'African' leadership and management in organisation studies, Nkomo acknowledges the difficulties of her own positionality when making interventions about CMS in a South African context. Nkomo's reflection on her own positionality should encourage South African scholars to reflect more deeply on their own positionality as knowledge producers. Nkomo's work demonstrates that a critical scholar is a reflective scholar.

In providing a personal account, I engage in a tenet of CMS known as critical reflexivity. However, I explicate the concept of vulnerability as an added dimension in the critical-reflexive process. Along with vulnerability, I invoke the concept of the (sociological) imagination as an important process and outcome of critically self-reflective engagement.

The second contribution is at a more macro level and follows from the first. I argue that South African management studies suffers from a colonial double bind. A double bind in this sense refers to a situation where South African management studies is caught between two dominant narratives. The first is the hegemony of Anglo-Saxon knowledge production in the discipline (Gantman, Yousfi & Alcadipani 2015), and the second is a historic Afrikaner-nationalist dominance in the discipline (Ruggunan & Sooryamoorthy 2014). I contend that South African management studies has to liberate itself from both these binds. In a sense, a double decolonisation has to happen. I argue that as much as this is an act of resistance by those of us working within a CMS paradigm, it is also an act of love towards ourselves, our students and the future of the discipline.

A note on the methodology

Chapter 4 is the outcome of three phases of research into critical management studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) that was funded by a teaching-and-learning grant from UKZN. Whilst each phase of the research is a 'stand-alone' project in its own right, Chapter 4 provides a useful platform to reflect on the synergies across these projects in making larger claims about CMS in a South African context. The first phase of the research involves an auto-ethnography of my teaching practice and philosophy as an academic within human resources management as a discipline within a larger school of management studies. This is the reflexive lens through which I then engage in the subsequent phases of the research. Auto-ethnography is a well-established methodology and is increasingly being used by academics as a sense-making exercise in understanding their work as scholars and teachers (Bell & King 2010; Cunliffe & Locke 2016; Dehler 2009; Fenwick 2005; Hooks 2003; King 2015; Learmonth & Humphreys 2012; McWilliam 2008). The second phase of the project took place in 2014 and 2015 and involved an interpretive engagement with students and staff in human-resource management (HRM) in my discipline about how they perceive and make sense of the intellectual project of HRM as currently offered at UKZN. This occurred through the use of in-depth interviews with eight academic staff in HRM and two focus groups each with second-year and honours students in HRM, respectively. The final phase of research involved a bibliometric (quantitative) and content analysis (qualitative) of the main outlet of human resources scholarship in South Africa, the South African Journal of Human Resources Management, from 2003 (the year of its inception) to 2013. Full ethical clearance was obtained from the UKZN ethics committee, and all the principles of informed consent were applied to all participants for all phases of the project. Chapter 4 draws on key elements of the findings from the 'data' to support the larger arguments made in it. A caution to the reader however is that this is not a data-driven chapter but a philosophical, reflexive account of how I view some of the challenges and possibilities for building a CMS in a South African context.

Part 1: Racialised epistemologies of management studies in South Africa

Currently, in 2016, South African institutions of higher education are experiencing a wave of student protests nationally (Karodia, Soni & Soni 2016; Ngidi et al. 2016; Pillay 2016). These protests began in 2015, culminating in the #FeesMustFall movement which has captured the imagination of South Africans, especially young South Africans (Butler-Adam 2016; Le Grange 2016). In 2016, parts of this social movement led by students are calling for the decolonisation of the curriculum at universities. Whilst the meaning of decolonisation remains nebulous at this stage in the social movement for curriculum change, there are trends identified by students and some academics as to what this process would entail.

Firstly, students claim that higher education and the higher-education curriculum in South Africa is highly racialised (Higgs 2016; Prinsloo 2016). Curricula elevate Anglo-Saxon and Afrikaner knowledge bases at the expense of 'black African' indigenous knowledge. (Luckett 2016). Secondly, this iniquitous state in which some types of knowledge are valued over others contributes to asymmetrical relationships of power between the majority of black students and the majority of white faculty (Molefe 2016).

Provoked by these claims, I engage in a second argument that the decolonisation of management studies in South Africa must not substitute one (colonial) knowledge-production model that legitimates managerial dominance and control for another (indigenous, African nationalist) model of dominance and control. What is needed is to provide an emancipation from colonial and postcolonial accounts of managerialism, even if this means emancipating universities from management studies altogether as suggested by Klikauer (2015). Decolonisation does not mean substituting North-American textbooks with African-authored textbooks that espouse the same managerialist ideology.

Any meaningful discussion about South Africa and critical management studies must take into account the notion of 'race'. Whilst social scientists are keen to eschew race as an essentialist category, race nonetheless has profound material consequences as epitomised by the apartheid (and post-apartheid) project of racial classification (Durrheim & Dixon 2005; Ruggunan & Mare 2012). I argue that any attempt to 'decolonise' management studies must take into account our racialised past and present.

In apartheid South Africa, universities served as an initial form of racialised social closure into certain professions (Bonnin & Ruggunan 2016). Tertiary institutions were segregated on the basis of race and ethnic group. Of the 21 universities in apartheid South Africa, nine were for Africans (further segregated according to ethnic groups), two catered for coloured and Indian people with the remaining 15 dedicated for white South Africans (but divided between English-language and Afrikaans-language universities). Those allocated to black South Africans often did not offer the tertiary qualifications that would enable a professional qualification. For example, no 'black' universities were allowed to offer the Certificate in the Theory of Accounting (CTA), a qualification required by all those who wished to become chartered accountants (Hammond et al. 2012:337), and only the 'whites-only' former technikons offered qualifications in textile design, ensuring that no black textile designers were able to qualify (Bonnin 2013).

There were exceptions; some of which were in the areas of medicine, law, teaching and social work. The apartheid state did not want to play a direct role in the day-to-day or primary welfare of African people (Mamphiswana & Noyoo 2000) and thus allowed black South Africans access to certain types of professions that would allow 'blacks to look after blacks'. Some of these professions included nursing, social work, teaching, law and medicine. This is in keeping with the apartheid state's ideas of separate development (Bonnin & Ruggunan 2016). Professions outside of the idea of 'social welfare' were not viewed as requiring the participation of black South Africans since these professions were not directly related to issues of social welfare. The state was uncomfortable with the idea of white hands on black bodies or black hands on white bodies in the fields of medicine and nursing, for example. Hence they allowed black South Africans entry into these professions albeit in a controlled and segregated manner (Marks 1994).

It is within this context of racialised and unequal higher education that disciplinary academic and ideological identities developed. I argue that management sciences (note the positivist connotation of the discipline explicit in the word 'sciences') and industrial psychology developed disciplinary identities in the 1960s at Afrikaner universities in South Africa. This was during the zenith of apartheid South Africa. However, in South Africa, the discipline has its roots as far back as 1946 with the establishment of the National Institute for Personnel Research (NIPR) at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). The NIPR, with its view of racialised and gendered hierarchies of skill (Terre Blanche & Seedat 2001), focused on applied principles of industrial and management sciences. Further, the CSIR was viewed as a proapartheid organisation up until 'the transitional period of the 1990s' (Le Roux 2015). Disciplinary knowledge was therefore not immune from the racial capitalism that informed the apartheid project in South Africa. The first fully fledged department of industrial psychology was, for example, located at the University of South Africa. According to Schreuder (2001), this location had the following consequences:

The Department [at UNISA] also acted as a mother figure for the traditional black universities and full-blown departments were eventually introduced at all these universities, as a direct result of Unisa's influence. (p. 3)

It were these Afrikaner centres of epistemological dominance that then paternalistically 'transferred to black universities departments of management and industrial psychology' (Schreuder 2001). Industrial psychology can be viewed as the 'mother' discipline of human resources management in South Africa. The transfer of content knowledge was accompanied by the transfer of disciplinary and ontological knowledge about what the management sciences are. Thus the development of management sciences (to use the positivist terminology) occurred at the intersection of Anglo-Saxon and Afrikaner nationalist epistemologies of what management sciences should entail. The question that needs to be asked is for whom and for what purpose the applied side of industrial psychology, human resources management and management sciences was constructed. It is perhaps not surprising that the first doctorate awarded in industrial psychology in South Africa in 1957 was a for a thesis entitled Die opleiding van Kleurlingtoesighouers in 'n klerefabriek' [The training of Coloured supervisors in a clothing factory]. I contend that the Afrikaner nationalist obsession with racial categorisation and eugenics (Dubow 1989; Singh 2008) found a natural home in South African management sciences. Black bodies were to be controlled, disciplined and punished. There was something innate about the black body that rendered it cognitively and physically different and thus not suited for all types of work and labour.

A racialised form of Taylorism was at the crux of the apartheid labour project, and management sciences provided a 'scientific rationale' for this project. A democratic and inclusive management studies was not possible in an undemocratic state. As Sanders (2002) shows in his work, during the apartheid era intellectuals and academics, especially those at Afrikaner or previously 'white' universities, were complicit (even in their silence) in the apartheid project (see Le Roux 2015 for the tension between the complicity and resistance of academics at South African Universities during apartheid).

There is a dearth of publications on the history of management studies in South Africa. However, there are two key publications that are revealing in their omissions. The first on the history of industrial psychology in South Africa by Schreuder (2001) and the second by Van Rensburg, Basson and Carrim (2011a, 2011b) examine the history of the development of human resources management as an applied profession. Both pieces do not speak to apartheid. In fact, the word apartheid is not mentioned once in either article. Race, power relations and the politics and purposes of knowledge production are rendered invisible. Descriptive accounts are provided with no reflexivity as to the intellectual projects of management studies under apartheid South Africa. Management sciences and HRM values and content are thus presented as universal. A first intervention in the decolonisation of management studies therefore must be to provide a critical and reflexive historiography of the disciplines in the form of publications. This will allow us to engage in processes of 'denaturalisation', there by rendering the familiar narrative of South African management studies 'strange', provocative and disruptive (Fournier & Grey 2000; Prasad & Mills 2010).

Concomitant with the dominant Afrikaner and Anglo Saxon project of management studies to control, discipline and increase perfomativity towards profit is the emphasis on the scientific method and the positivist approach (Mingers & Willmot 2013; Wickert & Schaefer 2015). I contend that the daily administration of the apartheid state project, like that of Nazi Germany or America during the height of slave ownership (Cooke 2003; Johnston 2013; Stokes & Gabriel 2010; Rosenthal 2013), was a profoundly bureaucratic and scientific management practice. The preoccupation of the apartheid state with 'scientific' racial classification, the administration of apartheid legislation and even the 'pencil test' (used to assess how straight someone's hair is, and based on straightness of hair, a racial classification was made) as a scientific means of determining one's 'race' would have resonated with the positivist philosophy of management studies at the height of apartheid (Posel 2001). Scientific evidence could be collected to demonstrate why labour markets needed to be racially segregated and as a way to manage the moral panic of racial integration.

This fetishisation of positivism continues in most South African schools of management. For example, theses by Bruce (2009); Kazi (2010) and Pittam (2010) are the only attempts to provide a critical discourse analysis of South Africa journals that focus on human resources management. Both Bruce and Pittam report that, from their content analysis of key South African journals in management studies, managerial discourses (as opposed to critical-managerial or anti-managerial discourses) persist. Both conclude that these journals overwhelmingly reflect a managerial bias, even when considering topics that are 'softer' or more focussed on human relations such as work-life balance. Their work provides a revelatory account of the mainstream agenda of South African management studies.

Institutional affiliation and knowledge production in management studies in South Africa

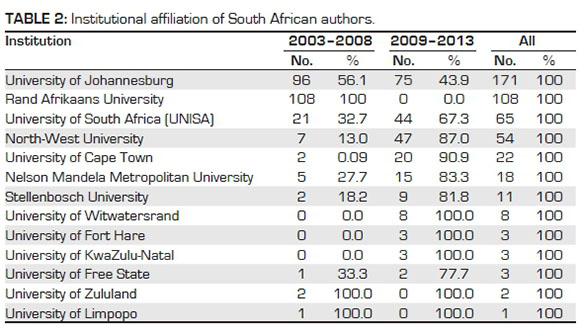

In an attempt to extend on the work of Bruce (2009), Kazi (2010) and Pittam (2010), Ruggunan and Sooryamoorthy (2014) provide a quantitative bibliometric analysis of the most important South African outlet for South African research in human resources management, the South African Journal of Human Resources Management (SAJHRM). In their review of a decade of research published in this journal (from 2003 to 2013), they made the following findings. Of a total of 259 papers published, more than 86% of articles published in the journal were authored by white South Africans (as first authors). Most of these authors work or worked at former Afrikaner universities with the majority of authors affiliated with the former Rand Afrikaans University (RAU) and the University of Johannesburg (UJ). RAU merged in 2005 with the Witwatersrand Technikon and the Soweto and East Rand campuses of Vista University to become the University of Johannesburg. The table below demonstrates the main institutional knowledge producers of empirical work in the SAJHRM.

The top four producers of papers in the South African Journal of Human Resources Management are from the former Afrikaner Universities. This is not surprising, given the epistemological genesis of the discipline in South Africa. The racial and gender demographics of authors are shifting across the South African higher-education landscape due to active state intervention. For example, women as first authors outnumber men in the SAJHRM. Black (African, Indian and coloured) authors are still in the minority, but there is an upward trend in the number of contributions from these 'groups'. This however does not reflect a shift in the type of knowledge being produced in management studies.

Three cautions

This section renders three cautions about why a demographic shift in the people who produce knowledge does not equate to a profound shift in the content of the knowledge produced. The first caution is that a racial and gendered democratisation of the discipline in terms of who is publishing does equate to an epistemological decolonisation of the discipline. It may instead become a neo-colonial project to further legitimise the managerialist discourse of the discipline. In the current context of racial and curricula transformation in higher education, decolonisation often serves as a shorthand for increasing the racial diversity of South African faculty. Whilst this in itself is a non-negotiable and laudable goal, it is not tantamount to decolonising the curriculum of management studies or any other discipline. A second caution is the tendency to equivocate research and textbooks by South African, African (from the continent) or Global South (nationality of authors) authors as innately postcolonial, decolonial or critical. From my own experience as a HRM academic, I have noted that the authors of South African HRM texts are more diverse in terms of race and gender, which is encouraging. However, the texts still reflect mainstream AngloSaxon management epistemologies accompanied by local case studies to make the texts 'relevant' for local students. This is far from a decolonial project. Rather, it seems like a neo-colonial project perpetuating dominant managerialist discourses. A third caution centres around the issue of appropriating African concepts such as ubuntu (Govender & Ruggunan 2013) and marketing these concepts as forms of indigenous African philosophies that are relevant to management studies. This is mainly advocated by management consultants and has resulted in a plethora of popular management books on ubuntu, for example Jackson (2013) and Nkomo (2011). As Mare (2001) argues, it is self-serving to appropriate African philosophies to prop up dominant managerial discourses. The South African scholarly literature on HRM remains silent on this sleight of hand by management practitioners. Critique has come from South African industrial sociology instead and from some international scholars. I would argue that South African HRM is therefore complicit in this appropriation to further its own managerial project.

HRM practitioners and consultants use ubuntu as a tool for 'diversity management', transformational leadership and conflict management, amongst other types of HR practice. Whilst not discounting the need and usefulness of indigenous philosophies in academia (in fact, this is an essential part of the decolonisation process), it is vital that we as CMS scholars ask for whom and for what purposes these indigenous knowledge systems are being applied (Banerjee & Linstead 2004; Hountondji 2002; Jack et al. 2011; Westwood & Jack 2007). These three cautions need to be framed within a larger debate on identity politics and 'who can speak for whom.' As Nkomo (2011) eloquently argues in her piece on the postcolonial condition in African management studies, positionality is important.

Epistemic violence against the other

The core curriculum of management studies in South Africa perpetuates a form of epistemic violence (Spivak 1988) regardless of the race and gender of knowledge producers. For Spivak, epistemic violence refers to the violence of knowledge production. Teo (2010) contends that, for epistemic violence to operate, it has to have the following:

[A] subject, an object, and an action, even if the violence is indirect and nonphysical: the subject of violence is the researcher, the object is the Other, and the action is the interpretation of data that is presented as knowledge. (p. 259)

I argue that, in the case of management studies, the epistemological violence refers to the interpretation of social-scientific data concerning the Other (Spivak 1988; Teo 2010). The Other in this case refers to employees and is produced under the following conditions (Teo 2010):

[When] empirical data are interpreted as showing the inferiority of or problematizes the Other, even when data allow for equally viable alternative interpretations. Interpretations of inferiority [or problematizations] are understood as actions that have a negative impact on the Other. Because the interpretations of data emerge from an academic context and thus are presented as knowledge, they are defined as epistemologically violent actions. (p. 295)

I argue that critical management studies needs through its three tenets of reflexivity, denaturalisation and critical performativity to render visible these acts of epistemic violence. Sceptics like (Klikauer 2015) remain unconvinced that CMS can actually create the conditions to transcend epistemic violence once it has identified instances of such violence. Given the persistence of the racial division of labour and racial hierarchies in the South African labour market (Commission for Employment Equity Report 2015), I posit that the practice of managerialism as informed by dominant managerialist discourse in South Africa has been unable or unwilling to shift in any significant manner the racial demographics of the labour market in the private sector. Whilst global racism is not new or unique, it does assume a specific form in the South African context. A Fordist system of racialised capitalism in the form of apartheid still resonates 25 years after the official dismantling of apartheid and 300 years after the start of British, German, Portuguese and Dutch colonial projects in Southern Africa. In HRM, 'diversity' serves as a proxy for 'race' and is something to be managed and controlled lest it creates panic amongst private-sector capital. The recent cases of Marikana and the class-action suits brought against mining capital by South African miners demonstrate the expendability of black bodies to capital (Alexander 2012). Banerjee's (2011:1541) work shows how the political, social and economic conditions that enable the extraction of natural and mineral resources from indigenous and rural communities in the Global South lead to 'dispossession and death'. This has certainly been the South African experience regarding mining capital and its managerial style despite the existence of corporate programmes for social responsibility at all the major mining houses based in South Africa. Forms of epistemic violence transform into actual physical violence against expendable black bodies as witnessed in Marikana.

The content analysis of the South African Journal of Human Resources Management from 2003 to 2013 demonstrates empirically the ways in which discourses developed about the expert and the other (Ruggunan & Sooryamoorthy 2014). The HRM researcher is the subject of the epistemic violence which is directed at the worker who is the Other. For example, the key themes that were discovered after an iterative data-reduction process are as follows:

Theme 1: Human resources management exists for managers

Managers are constructed as rational, expert and logical beings that make decisions based on positivist 'scientific research' created by HRM researchers in the academy. This also does a disservice to managers. The contributions to this journal implicitly situate the manager as all-rational, therefore denying managers the fallibilities of being human. As the literature demonstrates (Dent & Whitehead 2013; Sveningsson & Alvesson 2003), managers struggle with their own nuanced identities and what it means to be a manager.

Theme 2: Employees are therefore viewed as irrational, with little to no agency

They need to be managed to have their potential realised for more efficient profit-driven production. Asymmetrical power relations are not fully voiced. Bruce and Nyland (2011) provide a historiographic account of how managerial identify becomes constructed as rational and worker identity as irrational. This theme therefore supports their arguments.

Theme 3: Race, gender and sexuality are viewed as instrumentalist, essentialist demographic categories that are included as nominal variables on a Likert scale

There is no attempt in any of the articles to deconstruct or provide a critique of racial classification systems. These categories are seen as a natural order. Scholars write about topics such as employment equity, diversity in the workplace and affirmative action without a reflexive or critical voice. This leads to studies that exclusively focus on how management can use these racialised and sexualised bodies to increase performativity and organisational efficiencies.

Theme 4: Workers possess infinite human resourcefulness

This theme was discovered mainly from articles published in the journal from 2009 to 2013. It refers to work on performance management, work flexibility, talent management, upskilling, reskilling and improvements that workers have to make to themselves to ensure their employment in increasingly insecure labour markets. HR scholars believe that workers (as human beings) present an infinite and innate ability to constantly adapt to new labour-market conditions. Work by Costea, Crump and Amiridis (2007) introduces the concept of infinite human resourcefulness and how it has insinuated itself into HRM practice and discourse. HRM and managerialism construct the self as a work that is infinitely in progress, always being retooled to achieve more but never quite achieving it. This seems to be the philosophy informing most performance-management systems, for example.

Theme 5: The for-profit organisation is a norm

Whilst some articles focus on human resource issues in the public sector, the majority of articles focuses on the private-sector organisation. The organisation is presented as normative rather than a contested site of struggle.

Theme 6: Positivism is the dominant methodological philosophy employed by scholars publishing in this journal

The inheritance from industrial psychology is clearly seen here. There is an overwhelming use of standardised psychometric instruments that are applied to different populations in different work contexts. The work tends to be more theory validating than theory generating. Positivism is rendered normative.

Theme 7: Human relations are pro-worker

Many topics such as work-life balance, diversity in the workplace, spirituality in the workplace and transformational leadership, for example, initially appear as pro-worker but inevitably end up being calls to action to increase performative efficiencies in the workplace. 'It's all about the bottom line.'

The themes articulated above echo those found in similar studies in the Global North (Dehler & Welsh 2016; Fournier & Grey 2000; Spicer et al. 2009; Willmott 1992). This demonstrates the universality of the intellectual project of mainstream management studies. I was curious as to how the themes identified through a critical content analysis of the main outlet of HRM scholarship in South Africa may also speak to (if at all) perceptions held by HRM students and HRM permanent lecturing staff of HRM as a discipline and an intellectual project, hence the second phase of the project. In other words, do HRM scholars and professors transmit a specific set of managerialist values to students? If they do, can these value agents also change the nature of the values transmitted? The second half of Chapter 4 aims to speak to these questions.

Part two: The year of living dangerously

In our 2014 article, 'Critical pedagogy for social change' (Ruggunan & Spiller 2014), I reflect on my journey from being an academic in a department of industrial psychology to being an academic in a department of human resources, albeit at the same university.

I moved across disciplines in 2011 because funding decisions regarding my university's College of Humanities (where industrial sociology was located) left the College with limited resources. At the end of 2010, I was one of two permanent staff members in the programme for industrial sociology. This became an untenable position to work in, given that the Department originally consisted of seven permanent staff members. A post had opened up in the discipline of human resources management in the College of Law and Management on another campus of my University, and I decided to apply for it. At the time, I never considered myself a serious candidate, given the vastly different epistemic approaches between industrial sociology and management studies in South Africa. I remember thinking, 'Why would a management school hire an industrial sociologist, especially one whose work has been pro labour and implicitly anti-managerialist?'

I was therefore surprised to be shortlisted and subsequently appointed as a senior lecturer in the discipline of human resources management in the College of Law and Management Studies in 2011. The cross-pollination of social scientists from colleges of social sciences and colleges of humanities with those from business or commerce schools in the United Kingdom has been documented by critical management scholars like Grey and Wilmott (2005). As South Africa emulates the same form of new managerialism at our universities, it seems that many social-science academics have to find new disciplinary homes, many of which will be in business schools. Houghton and Bass (2012) are one of the first publications about this phenomenon that is gathering pace in the South African context.

Their article, 'Routes through the academy: Critical reflections on the experiences of young geographers in South Africa', further captures my frustrations about the commodification of South African education along a Thatcherite path. The article points out how South African academics, from sociologists to geographers, have to retool and explore new disciplinary paths and career routes in the academy. These are important interventions in understanding the politics and practices of knowledge production beyond the Anglo-American core (Hammet & Hoogendoorn 2012).

However, I would argue that it may also represent a moment of opportunity and resistance for those of us who are advocates and practitioners of a critical management studies in South Africa. It provides an opportunity to spread ideas into knowledge-production spaces to which we may not have had access otherwise. It is also a double act of emancipation and resistance to stay within the academy as CMS advocate (albeit in a different disciplinary home) rather than leave the academy altogether. If an unintended (some would say intentional) consequence of the neoliberal commodification of universities globally is the erosion of critique from public intellectuals in the social sciences and the humanities by making work in these areas insecure, that critique can reform and be articulated from new disciplinary spaces such as schools of management studies. It also opens up a space for broader reflexive debates on the intellectual project of specific disciplines, whether these be geography, accounting, management studies or medicine.

I found my new disciplinary home better resourced and better staffed. This increased the time available to me to more deeply reflect on my new role as a HRM academic. Was I to be, as Klikauer (2015) contends, an accomplice to neo-liberal capitalism or was there space for me to become an agent of change through reflecting on the values underlying society? This dissonance generated much discomfit and introspection in me during 2011. It produced a state of what I term vulnerability. I contend that vulnerability is part of the critical self-reflexive process of CMS. As the literature indicates, the flipside of vulnerability is creativity (Akinola & Mendes 2008; Brown 2012a, 2012b). Vulnerability produces a disruption, a destabilisation of existing pedagogical and disciplinary knowledge. I was deeply aware, as Nkomo (2011) observes in her account of moving from the USA to a South African department of human resources, that the Anglo-American epistemological paradigm was dominant. This was reflected in the types of textbook prescribed to students and the types of topic explored in various modules. Where South African texts were used, they reflected the main centres of HR knowledge production, that is, the formerly Afrikaner universities. However, apart from the affiliation of authors of textbooks, the narrative of the discipline of HRM was a predominantly managerialist and positivist one. We were, as averred to earlier in Chapter 4, caught in a double colonial bind, an Anglo-Saxon-Afrikaner nationalist nexus.

The geography of the UKZN as a multiple-campus institution means that HRM students cannot easily choose electives or majors in philosophy, sociology, psychology or other modules outside of the College at which they were enrolled. Apart from curricular restrictions, they would have to travel 11 kilometres to a separate campus to attend lectures there and then travel back to their home campuses. The multi-campus model means that certain colleges have specific geographic homes. Thus commerce studies are situated at Westville Campus and social-science and humanities studies are situated at the Howard College Campus in Glenwood. One impact of this is that curriculum development happens in isolation, and there is very little opportunity for interdisciplinary work across colleges. I therefore arrived to very insular curricula being offered in the curriculum for human resources management. This contributed to my vulnerability as I felt that I had to retool extensively and 'forget' my industrial-sociology training. Whilst there were synergies between industrial sociology and human resources management, the former was very labourist and the latter very managerialist. This dissonance and vulnerability allowed me to discover the CMS literature and embark on a historiography of HRM (still a work in progress) in South Africa. It was an empowering experience that led me to examine the content, message and values of the HRM modules I was teaching. I was also wary of one of the pitfalls of CMS practitioners as articulated by Grey et al. (2016), namely that one can be condescending of the voices and practices of other academics in the discipline. Vulnerability also means letting go of 'the ego of expertise'. It involves a questioning of one's role as the expert (even when that expertise is a CMS expertise!). The year 2011 was therefore one of relocation, dislocation, vulnerability (and its flip side, creativity) and conscientisation. It was at the end of academic year in 2011 that I thought it prudent to hear from other voices within the HR academy and student body at UKZN and began writing a proposal to fund a project on critical management studies. I found the university teaching and learning office (UTLO) and my colleagues within my HRM discipline very supportive of my proposal. Perhaps this is an anomalous experience, but I found a cohort of colleagues who were supportive, and my proposal was funded for a period of two years. This once again speaks of the ability to craft critical spaces in neoliberal or managerialist universities (as is the identity of most universities globally and in South Africa). The support could further be explained by a UTLO cohort of staff that are sympathetic ideologically to critical theory and its application to management studies. The support offered to CMS scholars may differ greatly, depending on the organisational culture of the university in which he or she practises. Thus, my experience may not be one that is enjoyed nationally. However, as this book project demonstrates, such support is gaining momentum.

Towards a management studies for publics

Almost a year after my move to my new home in management studies, an event occurred in South Africa that reverberated globally: the massacre of miners at Marikana in September 2012. It continues to receive extensive analysis globally and nationally. What intrigued me and further propelled me to push for a CMS agenda in HRM was the silence from management-studies academics about the egregious act of violence against workers. The ways in which the 'Marikana Massacre', as it became known, was integrated into my teaching practice was written up in a 2014 article by myself and Dorothy Spiller. The point I want to reiterate for Chapter 4 however, is the lack of any public-intellectual critique of the mining houses and their management by management studies intellectuals in South Africa. The silence was overwhelming. Comment and opinion from the academy emanated from development-studies, sociology and political-science scholars, and to a limited degree, economists. Given that what happened at Marikana was an outcome of pathological managerial practices of mining capital, the lack of a more public discourse initiated by management-studies scholars was revealing.

In his presidential address to the American Sociological Association in 2004, Michael Burawoy spoke about a public sociology. This refers to a style of sociology done for the greater public good as opposed to a private sociology which is done for professional and career mobility and usually speaks to the academy only. It is worth reiterating Buroway's (2005) argument verbatim:

Responding to the growing gap between the sociological ethos and the world we study, the challenge of public sociology is to engage multiple publics in multiple ways. These public sociologies should not be left out in the cold, but brought into the framework of our discipline. In this way we make public sociology a visible and legitimate enterprise, and, thereby, invigorate the discipline as a whole. Accordingly, if we map out the division of sociological labor, we discover antagonistic interdependence among four types of knowledge: professional, critical, policy, and public. In the best of all worlds the flourishing of each type of sociology is a condition for the flourishing of all, but they can just as easily assume pathological forms or become victims of exclusion and subordination. This field of power beckons us to explore the relations among the four types of sociology as they vary historically and nationally, and as they provide the template for divergent individual careers. Finally, comparing disciplines points to the umbilical chord that connects sociology to the world of publics, underlining sociology's particular investment in the defense of civil society, itself beleaguered by the encroachment of markets and states. (p. 20)

It may be useful for management, and indeed critical management studies, to draw on Burawoy's idea of public sociology. A critical-management studies that only offers critique is a legitimate form of intellectual endeavour in and of itself. However, in addition to this, we need a management studies for publics. I use the plural of public since the public that we should serve is composed of diverse sets of people and is heterogeneous. A management studies for different publics should speak not only to managers and for managers, but it also needs to speak about managers, about workers and about political economy. This type of critical-management studies and a management studies for the public were missing during the debates about Marikana. When management-studies academics speak publically in South Africa, it is usually about ways to increase managerial effectiveness in order to allow workers to be managed better in order to increase efficiencies or it is to provide critiques of union or labourist activities.

South Africa provides the perfect context politically, socially and economically for this experiment in management studies. Some critics like Klikhauer (2015) would argue that an activist management studies is a contradiction in terms, and management studies can only exist for a managerial class. Arguably, management studies should not even be a legitimate part of universities if it serves a managerial class only, particularly in the contexts of a developing state. If it is unable to generate its own form of critical-management studies and a management studies for publics, then it is merely a professional management studies that will continue to be exclusionary, undemocratic and a platform for epistemic violence.

Management lecturers' identities at work

Related to the issue of management studies for publics is the need to understand the ways in which lecturers construct their identities as management-studies academics. Work by Moosmayer (2012) and Huault and Perret (2016) suggests that management-studies academics are powerful transmitters of values to their students, even when those values may be the values of disciplinary knowledge rather than personal value systems. This often creates tension in the ways in which lecturers construct and perceive their identities. Three central themes on issues of identity were discovered from in-depth interviews with eight HRM lecturers at UKZN:

Theme 1: Knowledge is neutral

This is epitomised by quotes such as the following:

'[W]ell it is about the scientific method and what that determines. Business needs facts to make evidence based decisions ... so the scientific method is objective. I just present the findings to class.' (P1)

'I don't think science can have an agenda or value system, it simply presents a finding, whether you agree with that finding or not is another matter. There is no room for emotion ... so you will see that how and what I teach is common across similar modules in the country.' (P3)

Theme 2: Separation between personal and discipline knowledge value systems

Quotes from two participants suffice to illustrate this theme.

'I know that, for business, it is all about the bottom line, and much of our work that calls for greater employee empowerment gets ignored . This does upset me because as a private person I see every day how corporatisation is destroying the world around us, but at the end of the day as I said, it's about the bottom line in the real world, and I would not want my students unprepared for that world.' (P4)

'I feel that I have to present a very professional class since I am teaching about the corporate world. I guess if I was in the Arts or such it may be different but my spiritual and personal life is not for my students' consumption. I sometimes offer opinions about [corporate] scandals, but students pay a lot of money for their [business] degrees so I have to deliver.' (P5)

[ When probed further on this, the participant said] 'I mean my spiritual beliefs, don't always support the scientific method for example ... [laughs], but it's not relevant at the end of the day.' (P5)

'We do an ethics module at second year, so I'm sure values are part of that syllabus. We have to teach for the real world. We will also be designing a first-year module based on the principles of responsible management education, so I think that may bring values into the picture.' (P6)

Theme 3: Values as concern for 'other disciplines'

'[0]ur mandate is quite clear, we have to service the private sector. Yes, I think students can benefit from modules that teach values in philosophy or sociology, but for us, we do cover sustainable development and such but every module can't be an ethics or values module. I think these things can be better taught in social-science modules. That doesn't mean I don't have certain moral values, but students don't want to sit and listen to my stories.' (P2)

'I do often think about the issues of values, and I try to highlight the human-relations aspect in my teaching. However, most of our students I think end up in highly administrative jobs so I am not convinced that they actually get to make a difference. They end up as cogs . perhaps we do need to discuss this as a discipline ...' (P7)

There are three points of reflection on the above themes. Firstly, all participants interviewed expressed both semantically and latently the belief that knowledge production, which they articulated as 'the scientific method' which itself is a shorthand for positivism, is neutral and objective. There is also a strong sense of a professional identity based on 'scientific' principles and objectives. As argued by Ruggunan and Spiller (2014) and Moosmayer (2012), the positioning of positivist values as universal and neutral has been mainstreamed into management studies as a discipline. This concurs with Ruggunan and Spiller's (2014) argument that the values of positivist approaches to social sciences should be made explicit. They contend that the positivist approach constructs the academic as a 'value-free agent' in the classroom. Moosmayer (2012:9) refers to this as the 'paradox of value-free science and the need for value-orientated management studies.'

How then can a management-studies academic disrupt this notion of a value-free or economic rationalist approach to HRM? Ruggunan and Spiller (2014) posed this question in 2014 in their speculative piece on critical management studies for social change in South Africa. Since then, there has been a colloquium on critical management studies organised at the University of Johannesburg in 2015 and an Academic Monitoring and Support Colloquium at the UKZN where critical management studies was the theme of the keynote address given by myself. Both these events attempted to answer the above question by suggesting that critical self-reflexivity is required by management-studies academics if we are to give voice to values.

As we argued in our 2014 paper (Ruggunan & Spiller 2014), we support calls by Moosmayer (2012) and Lukea-Bhiwajee (2010) towards the following:

[T]o encourage greater introspection about the nature and purpose of the discipline amongst academics. This may encourage a shift towards a more social and critical perspective in the ways in which the discipline is taught and the research is generated ... Academics need to be value agents and being scientific does not imply being value free. (p. 230)

Secondly, management academics also experience a form of cognitive or emotional dissonance. This tension is most evident due to the separation of 'discipline value systems' and 'personal value systems'. Personal values also do not always have to be 'positive'. They can be negative, for example, sexist or racist or pro exploitation. Advocates of critical management studies therefore have to be careful when discussing values and value systems. Participants all said that these have to be separated. It may be hyperbolic to argue that management-studies academics are 'handmaidens of capitalism', but the interviews do reveal a cognitive and emotional dissonance between the personal and public identity of academics. The emotional labour literature (Ashforth & Humphrey 1993; O'Brien & Lineham 2016) uses concepts such as deep acting and surface acting to describe the difference between authentic and superficial displays of emotion during the labour process. The eight academics interviewed all spoke about their work in the class room as a form of 'performance', as a way of enacting the behaviour expected of a rational-scientific lecturer in the management sciences. More empirical work needs to be done to assess the extent to which deep and surface-acting behaviour influence this performativity of identity. Whilst emotional labour16 amongst teachers and academics abounds in the literature, more focused work is needed on management-studies lecturers.

Thirdly, the theme that I labelled 'values as the concern for other disciplines' is really a failure of imagination within management studies generally and in a South African context. This failure of imagination has been captured by Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) in the global literature on critical-management studies and the mainstream literature on management studies. The South African literature is less robust on the need for a (re-imagined) South African management studies that espouses the principles of critical-management studies.

I argue that what is needed is a series of imaginations in management studies. These involve three imaginations. The first of these is an imagination for what a management studies for publics may look like. The second is an imagination for a new research agenda beyond 'gap-spotting', and the third is a pedagogical imagination beyond managerial ethics as well as principles of responsible management education (PRME). These three imaginations, I argue, can be catalysed by a sociological imagination (see Alvesson & Sandberg 2013; Chiapello & Fairclough 2002; Watson 2010). The idea of the sociological imagination is associated with C.W. Mills' ground-breaking 1970 book, called The sociological imagination. It could also be referred to as a social-scientific imagination. Mills argues that such an imagination calls for the following (Watson 2010):

[L]inks to be made between personal troubles of individuals (a person losing his or her job for example) and broader public issues (the issue of unemployment in society for example). (p. 918)

This link between the personal (micro) and the public (macro) or political economy provides for a more analytical and critical management studies than we have in South Africa at present. This does mean that scholars need to engage in deep contextual work and a constant questioning of what is seen as normative in management studies. Management studies needs to exercise this sociological imagination for the public good (not corporate interests, private business or managerial good only). Social science is by nature a critical undertaking, and HRM in South Africa especially needs to identify itself as a social science rather than a business science - or any imitation of the natural sciences as I argue it currently does. This allows us to view management studies as 'a set of practices, embedded in a global economic, political and socio-cultural context' (Janssens & Steyaert 2009:146).

Given the intrinsic critical nature of social science, the 'critical' in critical-management studies is actually unnecessary. In 'doing' management studies for the public(s), we need to bring together those management-study academics who see their role as increasing the performativity of employees for corporate efficiency and those who argue for an anti-performativity management studies. If we are to do good social science, all management-studies academics need reflexivity, including those who identify themselves as critical.

A management studies for publics, therefore, must be inclusive, and it requires imagining management studies as a social science (not a 'hard' or 'positivist' science). Discussion groups, colloquia (such as the one held at the University of Johannesburg in 2015), journals, business schools, organised labour and a range of other stakeholders need to engage in robust debate about who the publics are for management studies and what its intellectual project entails.

An outcome of the above is asking the following question: 'For whom do we do research and for what purpose?' Is it only to increase organisational and performance efficiencies? Is it to increase the career mobility (professional-management studies) of academics? Or is it as Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) contend only to fill incremental gaps in the literature? We perhaps research for all these reasons, but if we are to 'decolonise' management studies from its mainstream incarnation, we have to acknowledge that, despite a massive increase in the number of management-studies articles published globally in the last three years (Alvesson & Sandberg 2013:128), there 'is a serious shortage of high-impact' or ground-breaking research in management studies. Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) offer an analysis of why management-studies research has become so 'unimaginative', and I do not want to rehearse their arguments for Chapter 4. They also suggest strategies to shift from unimaginative, 'gap-spotting' research to ground-breaking research. Their work is important because it speaks to my second call to reimagine the research agenda for South African management studies. One way of doing this is by asking the difficult questions posed above. These questions are related to problematising our identity as management-studies academics, and it is through doing this 'identity work' that we can reimagine our research agendas, especially in the unique political economy that is South Africa.

The third imagination, the pedagogical imagining, involves a reconfiguring of how we do management studies in the classroom. As I argue in a 2014 article, this involves doing management studies (in the classroom) for social change. We need to engage with Spivak's concept of epistemic violence, the postcolonial and anti-colonial philosophical literature (Ahluwalia 2001; Appiah 1993; Bhabha 1994; Fanon 1967) and Frereian pedagogy. What do we hope to achieve in management studies education, and for whom do we hope to achieve it?

Conclusion

I hope that this edited collection and Chapter 4 will stir debate about the shape and purpose of a critical-management studies project in South Africa. Chapter 4 has been an exploratory reflexive 'think piece' that suggests three ways forward in decolonising management studies and advocating for a critical-management studies project. The first is to engage in critical historiographies of South African management studies and its allied disciplines. Such exercises unpack the ways in which disciplinary knowledge is produced over time and challenge the view that management-studies knowledge is universal and apolitical. The second is to engage in a management studies for publics, as opposed to a management studies for professional mobility or a management studies for a managerialist public only. This helps democratise the curriculum and research agendas and encourage more critical public-intellectual activities from within the field. The third point is that management-studies academics need to re-imagine the discipline through the lens of a sociological or social-science imagination which is inherently a critical and reflexive imagination. These three strategies for change will influence pedagogy, research and practice. To advocate for these changes is, as mentioned in my introduction, an act of resistance, an act of emancipation and ultimately an act of love.

References

Chapter 4

Ahluwalia, P., 2001, Politics and postcolonial theory:African inflections, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Akinola, M. & Mendes, W.B., 2008, 'The dark side of creativity: Biological vulnerability and negative emotions lead to greater artistic creativity', Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 34 (12), 1677-1686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167208323933. [ Links ]

Alcadipani, R., Khan, F.R., Gantman, E. & Nkomo, S., 2012, 'Southern voices in management and organization knowledge', Organization 19(2), 131-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350508411431910. [ Links ]

Alexander, P., 2012, Marikana: A view from the mountain and a case to answer, Jacana Media, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M. & Sandberg, J., 2013, 'Has management studies lost its way? Ideas for more imaginative and innovative research', Journal of Management Studies 50(1), 128-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01070.x. [ Links ]

Appiah, K.A., 1993, In my father's house: Africa in the philosophy of culture, OUP, New York. [ Links ]

Ashforth, B.E. & Humphrey, R.H., 1993, 'Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity', Academy of Management Review 18(1), 88-115. [ Links ]

Banerjee, S.B. & Linstead, S., 2004, 'Masking subversion: Neocolonial embeddedness in anthropological accounts of indigenous management', Human Relations 57(2), 221-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726704042928. [ Links ]

Banerjee, S.B., 2011, 'Voices of the governed: Towards a theory of the translocal', Organization 18(3), 323-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350508411398729. [ Links ]

Bell, E. & King, D., 2010, 'The elephant in the room: Critical management studies conferences as a site of body pedagogics', Management Learning (41)4, 429-442. [ Links ]

Bhabha, H.K., 1994, The location of culture, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Bonnin, D. & Ruggunan, S., 2014, 'Globalising patterns of professionalisation and new groups in South Africa', in XVIII ISA World Congress of Sociology, pp. 300-301, Isaconf, Yokohama, Japan, 13-19th July. [ Links ]

Bonnin, D., 2013, 'Race and gender in the making and remaking of the labour market for South African textile designers', paper presented to the British Sociological Association Work, Employment and Society Conference, pp. 180-183, University of Warwick, 03-05th September. [ Links ]

Brown, B., 2012b, Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead, Penguin, London. [ Links ]

Brown, C.B., 2012a, The power of vulnerability, Sounds True, Audio Recording [ Links ]

Bruce, C .2009, 'Do Industrial/Organisational Psychology journal articles reflect a managerial bias within research and practice?', MSocSci Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Bruce, K. & Nyland, C., 2011, 'Elton Mayo and the deification of human relations', Organization Studies 32(3), 383-405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840610397478. [ Links ]

Burawoy, M., 2005, '2004 American Sociological Association presidential address: For public sociology', The British Journal of Sociology 56(2), 259-294. [ Links ]

Butler-Adam, J., 2016, 'What really matters for students in South African higher education?' South African Journal of Science 112(3/4), 1-2. [ Links ]

Chiapello, E. & Fairclough, N., 2002, 'Understanding the new management ideology: A transdisciplinary contribution from critical discourse analysis and new sociology of capitalism', Discourse & Society 13(2), 185-208. [ Links ]

Cooke, B., 2003, 'The denial of slavery in management studies', Journal of Management Studies 40(8), 1895-1918. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-6486.2003.00405.x. [ Links ]

Costea, B., Crump, N. & Amiridis, K., 2007, 'Managerialism and "infinite human resourcefulness": A commentary on the "therapeutic habitus, derecognition of finitude" and the modern sense of self, Journal for Cultural Research 11(3), 245-264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14797580701763855. [ Links ]

Cunliffe, A.L. & Locke, K., 2016, 'Subjectivity, difference and method', Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 11(2), 90-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/QROM-04-2016-1374. [ Links ]

Dehler, G.E. & Welsh, M.A. (forthcoming 2016), 'A view through an American lens: Galumphing with critical management studies', in C. Grey, I. Huault, V. Perret & L. Taskin (eds.), Critical Management Studies: Global Voices, Local Accents, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Dehler, G.E., 2009, 'Prospects and possibilities of critical management education: Critical beings and a pedagogy of critical action', Management Learning Action 40(1), 31-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350507608099312. [ Links ]

Dent, M. & Whitehead, S. (eds.), 2013, Managing professional identities: Knowledge, performativities and the 'new' professional, vol. 19, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Dubow, S., 1989, Racial segregation and the origins of Apartheid in South Africa, pp. 19-36, Springer, New York. [ Links ]

Durrheim, K. & Dixon, J., 2005, 'Studying talk and embodied practices: Toward a psychology of materiality of "race relations"', Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 15(6), 446-460. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/casp.839. [ Links ]

Fanon, F., 1967, A dying colonialism, Grove Press, New York. [ Links ]

Fenwick, T., 2005, 'Ethical dilemmas of critical management education: Within classrooms and beyond', Management Learning 36(1), 31-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350507605049899. [ Links ]

Fournier, V. & Grey, C., 2000, 'At the critical moment: Conditions and prospects for critical management studies', Human Relations 53(1), 7-32. [ Links ]

Gantman, E.R., Yousfi, H. & Alcadipani, R., 2015, 'Challenging Anglo-Saxon dominance in management and organizational knowledge', Revista de Administração de Empresas 55(2), 126-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020150202. [ Links ]

Govender, P. & Ruggunan, S., 2013, 'An exploratory study into African drumming as an intervention in diversity training', International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 44(1), 149-168. [ Links ]

Grey, C. & Willmott, H., 2005. Critical management studies: A reader, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Grey, C., Huault, I., Perret, V. & Taskin, L., 2016, Critical management studies: Global voices, local accents, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Hammett, D. & Hoogendoorn, G., 2012, 'Reflections on the politics and practices of knowledge production beyond the Anglo-American core: An introductory note', Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 33(3), 283-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12005. [ Links ]

Hammond, T. Clayton, B. & Arnold, P. 2012. 'An "unofficial" history of race relations in the South African accounting industry, 1968-2000: Perspectives of South Africa's first black chartered accountants', Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23: 332-350. [ Links ]

Higgs, P., 2016, The African Renaissance and the decolonisation of the curriculum. Africanising the curriculum: Indigenous perspectives and theories, African Sun Media, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Hooks, B., 2003, Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Houghton, J. & Bass, O., 2012, 'Routes through the academy: Critical reflections on the experiences of young geographers in South Africa', Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 33(3), 308-319. [ Links ]

Hountondji, P.J., 2002, 'Knowledge appropriation in a postcolonial context', in C. Odora-Hoppers (ed.), Indigenous knowledge and the integration of knowledge systems: Towards a philosophy of articulation, pp. 137-142, New Africa Books, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Huault, I. & Perret, V., 2016, 'Can management education practise Rancière?', in C. Steyaert, T. Beyes & M. Partker (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Reinventing Management Education, pp 161-177, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Jack, G., Westwood, R., Srinivas, N. & Sardar, Z., 2011, 'Deepening, broadening and re-asserting a postcolonial interrogative space in organization studies', Organization 18(3), 275-302 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350508411398996. [ Links ]

Jack, G.A., Calás, M.B., Nkomo, S.M. & Peltonen, T., 2008, 'Critique and international management: An uneasy relationship?', Academy of Management Review 33(4), 870-884. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.34421991. [ Links ]

Jackson, T., 2013, 'Reconstructing the indigenous in African management research', Management International Review 53(1), 13-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11575-012-0161-0. [ Links ]

Janssens, M. & Steyaert, C., 2009, 'HRM and performance: A plea for reflexivity in HRM studies', Journal of Management Studies 46(1), 143-155. [ Links ]

Johnston, K., 2013, The messy link between slave owners and modern management, viewed 13 June 2016, from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/the-messy-link-between-slave-owners-and-modern-management [ Links ]

Karodia, A.M., Soni, D. & Soni, P., 2016, 'Wither higher education in the context of the feesmustfall campaign in South Africa', Research Journal of Education 2(5), 76-89. [ Links ]

Kazi, T. 2009, 'To what extent does published research on quality of work-life reflect a managerialist ideology in both its latent and manifest content?', MSocSci Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

King, D., 2015, 'The possibilities and perils of critical performativity: Learning from four case studies', Scandinavian Journal of Management 31(2), 255-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2014.11.002. [ Links ]

Klikauer, T., 2015, 'Critical management studies and critical theory: A review', Capital & Class (39)2, 197-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0309816815581773. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L., 2016, 'Decolonising the university curriculum', South African Journal of Higher Education 30(2), 1-12. [ Links ]

Le Roux, E., 2015, A social history of the university presses in apartheid South Africa: Between complicity and resistance, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Learmonth, M. & Humphreys, M., 2012, 'Autoethnography and academic identity: Glimpsing business school doppelgängers', Organization 19(1), 99-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350508411398056. [ Links ]

Luckett, K., 2016, 'Curriculum contestation in a postcolonial context: A view from the South', Teaching in Higher Education 21(4), 415-428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1155547. [ Links ]

Lukea-Bhiwajee, S.D., 2010, Reiterating the importance of values in management education curriculum, International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 5(4), 229-240. [ Links ]

Mamphiswana, D. & Noyoo, N., 2000, Social work education in a changing socio-political and economic dispensation: Perspectives from South Africa, International Social Work 43(1), 21-32. [ Links ]

Mare, G., 2001, 'From " traditional authority" to "diversity management": Some recent writings on managing the workforce', Psychology in Society 27, 109-119. [ Links ]

Marks, S., 1994, Divided sisterhood, race, class and gender in the South African nursing profession, Wits University Press, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

McWilliam, E., 2008, 'Unlearning how to teach', Innovations in Education and Teaching International 45(3), 263 269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14703290802176147. [ Links ]

Mingers, J. & Willmott, H., 2013, 'Taylorizing business school research: On the "one best way" performative effects of journal ranking lists', Human Relations 66(8), 1051-1073. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726712467048. [ Links ]

Molefe, T.O., 2016, 'Oppression must fall South Africa's revolution in theory', World Policy Journal 33(1), 30-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/07402775-3545858. [ Links ]

Moosmayer, D.C., 2012, 'A model of management academics' intentions to influence values', Academy of Management Learning & Educanon 11(2), 155-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0053. [ Links ]

Ngidi, N.D., Mtshixa, C., Diga, K., Mbarathi, N. & May, J., 2016, '"Asijiki" and the capacity to aspire through social media: The #FeesMustFall movement as an anti-poverty activism in South Africa', in Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, ACM, p. 15, Boston, Massachusetts. [ Links ]

Nkomo, S.M. & Ngambi, H., 2009, African women in leadership: Current knowledge and a framework for future studies, International Journal of African Renaissance Studies 4(1), 49-68. [ Links ]

Nkomo, S.M., 1992, 'The emperor has no clothes: Rewriting "race in organizations"', Academy of Management Review 17(3), 487-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/258720. [ Links ]

Nkomo, S.M., 2011, 'A postcolonial and anti-colonial reading of "African" leadership and management in organization studies: Tensions, contradictions and possibilities', Organization 18(3), 365-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350508411398731. [ Links ]

O'Brien, E. & Linehan, C., 2016, 'The last taboo?: Surfacing and supporting emotional labour in HR work', The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27(1), 1-27 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1184178. [ Links ]

Pillay, S.R., 2016, 'Silence is violence:(critical) psychology in an era of Rhodes must fall and fees must fall', South African Journal of Psychology 46(2), 155-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0081246316636766. [ Links ]

Pittam, H. 2010, Transformational Leadership: Inspiration or domination? A critical Organisational Theory Perspective, MSocSci Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

Posel, D., 2001, 'What's in a name? Racial categorisations under apartheid and their afterlife', Transformation 27, 50-74. [ Links ]

Prasad, A. & Mills, A.J., 2010, 'Critical management studies and business ethics: A synthesis and three research trajectories for the coming decade', Journal of Business Ethics 94(2), 227-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0753-9. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, E.H., 2016, 'The role of the humanities in decolonising the academy', Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 15(1), 164-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1474022215613608. [ Links ]

Rosenthal, C., 2013. 'Slavery's scientific management', in S. Rochman & S. Beckert (eds.), Waldstreicher D slavery's capitalism, pp. 62-86, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Ruggunan, S. & Sooryamoorthy, 2014, 'Human Resource Management research in South Africa: a bibliometric study of features and trends', unpublished paper, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

Ruggunan, S. & Maré, G., 2012, 'Race classification at the University of KwaZulu-Natal: Purposes, sites and practices', Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 79(1), 47-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/trn.2012.0036. [ Links ]

Ruggunan, S. & Spiller, D., 2014, 'Critical pedagogy for teaching HRM in the context of social change', African Journal of Business Ethics 8(1), 29-43. [ Links ]

Sanders, M., 2002, Complicities: The intellectual and apartheid, Duke University Press, Durham. [ Links ]

Schreuder, D.M., 2001, 'The development of industrial psychology at South African universities: A historical overview and future perspective', SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 27(4), 2-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v27i4.792. [ Links ]

Singh, J.A., 2008, 'Project coast: Eugenics in apartheid South Africa', Endeavour 32(1), 5-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.endeavour.2008.01.005. [ Links ]

Spicer, A., Alvesson, M. & Kärreman, D., 2009. Critical performativity: The unfinished business of critical management studies, Human relations 62(4), 537-560. [ Links ]

Spivak, G.C., 1988, 'Can the subaltern speak?', in L. Grossberg & C. Nelson (eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, pp. 271-313, Macmillan Education, London. [ Links ]

Stokes, P. & Gabriel, Y., 2010, 'Engaging with genocide: The challenge for organization and management studies', Organization 17(4), 461-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350508409353198. [ Links ]

Sveningsson, S. & Alvesson, M., 2003, 'Managing managerial identities: Organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle', Human Relations 56(10), 1163-1193. [ Links ]

Teo, T., 2010, 'What is epistemological violence in the empirical social sciences?', Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4(5), 295-303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00265.x. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche, M. & Seedat, M., 2001, 'Martian landscapes: The social construction of race and gender at South Africa's National Institute for Personnel Research, 1946-1984', in N. Duncan, A. van Niekerk, C. Rey & M. Seedat, Race, racism, knowledge production and psychology in South Africa, pp. 61-82, Nova Books, New York. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, H., Basson, J. & Carrim, N., 2011b, 'Human resource management as a profession in South Africa', SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur 9(1),1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v9i1.336. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, H., Basson, J.S. & Carrim, N.M.H., 2011a, 'The establishment and early history of the South African Board for People Practices (SABPP) 1977-1991', SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur 9(1), 1-15 http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v9i1.322. [ Links ]

Watson, T.J., 2010, 'Critical social science, pragmatism and the realities of HRM', The International journal of Human Resource Management 21(6), 915-931. [ Links ]

Westwood, R.I. & Jack, G., 2007, 'Manifesto for a postcolonial international business and management studies: A provocation', Critical Perspectives on International Business 3(3), 246-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17422040710775021. [ Links ]

Wickert, C. & Schaefer, S.M., 2015, 'Towards a progressive understanding of performativity in critical management studies', Human Relations 68(1), 107-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726713519279 [ Links ]

Willmott, H. (ed.), 1992, Critical management studies, Sage, London. [ Links ]

16 By emotional labour, I refer to the ways in which our jobs and occupations require us to regulate our emotions, feelings and expressions in order to achieve the outcomes of our work.