Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Commercii

versión On-line ISSN 1684-1999

versión impresa ISSN 2413-1903

Acta Commer. vol.16 no.2 Johannesburg 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v16i2.415

CHAPTER 1

On the possibility of fostering critical management studies in South Africa

Geoff A. Goldman

Department of Business Management University of Johannesburg South Africa

SUMMARY

Critical management studies, as an emergent paradigm, has found its way into the discourse surrounding the academic discipline of business management since the early 1990s. However, in South Africa, critical management studies remains virtually unexplored. Through a critical, dialectical approach, this conceptual paper sets out to introduce the South African academic community to the notion of critical management studies. This will be done through highlighting how critical management studies came to be and through a differentiation of critical management studies from conventional thinking concerning business management. The discussion on critical management studies concludes by emphasising the central tenets of critical management studies, namely denaturalisation, reflexivity and anti-performativity.

After introducing critical management studies, the discussion turns to what it can offer in advancing business management as an academic discipline in South Africa. In this regard, the notion of postcolonialism is explored. Regardless of the political and theoretical ambiguities surrounding postcolonialism, the relevance of postcolonial thinking in the realm of business management is advocated as a possible avenue in the search for mechanisms to promote indigenous knowledge and Africa-centred wisdom as far as business management is concerned. In an academic discipline dominated by American and European wisdom and knowledge, the search for local and indigenous knowledge concerning business management is of paramount importance if we wish to successfully engage with the unique challenges posed by the South African business environment.

Introduction

The objective of Chapter 1 is to introduce the emergent paradigm of critical management studies (CMS) to South African businessmanagement academics with a view on interrogating specific applications of CMS in the discourse of business management in South Africa. To pursue this aim, CMS as an emerging paradigm will be expounded upon, and its applicability to the South African context will be explored. Chapter 1 follows a critical dialectic engagement with literature and personal experience as an academic with more than 20 years of experience in the field of business management. The inquiry was sparked, in part, by conversations with peers on the seeming inefficiencies and areas of privation of current, mainstream methods of inquiry into business management and an openness amongst some academics to explore avenues of thought that challenge mainstream convention.

The South African academic community (at least those that work in the space of business management and related disciplines) seems to be heavily stooped in the positivist tradition, which has certain consequences. Firstly, positivists are driven by the notion that science can produce value-free, objective knowledge through the removal of subjective bias and non-rational interferences (Alvesson & Deetz 2000). This objective knowledge, in turn, forms a legitimate basis for the business organisation and the management of people in accordance with scientific principles (Adler 2002; Adler, Forbes & Willmott 2007; Fournier & Grey 2000). A disconnect is apparent when science becomes removed from the essential task of developing and shaping society and instead focuses on the application of science to maintain a current order (Adler et al. 2007).

The modernist tendency is to justify value commitments through reference to the authority of science, which denies the practical embeddedness of science within certain frames of reference (Alvesson & Willmott 2012). It is important not to confuse this notion with the practical applicability of individual research endeavours. The question is whether this scientism actually strives for betterment of society or for the maintenance of its own status quo. This means that knowledge claims arising from scientism are seen as authoritative and indubitable with scant (or indeed no) room for reflection on the outcomes of the applications of science (Alvesson, Bridgman & Willmott 2009; Alvesson & Deetz 2006; Grey 2004). Science thus gains a monopoly on the guidance of rational actions, and all competing claims on a rational course of action are to be rejected (Westwood 2005).

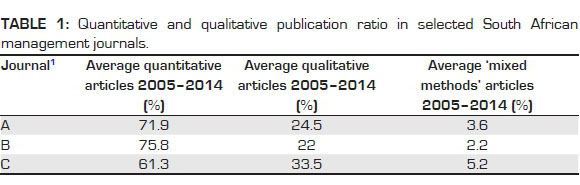

The above is quite obvious when one reflects upon the emergence of interpretive scholarly inquiry and qualitative methodologies in the discipline of business management (and related disciplines) amongst academics in South Africa. It has only been since the turn of the century that qualitative work -and publications - has attained a critical mass. This by no means implies that qualitative and interpretive work has taken centre stage in South Africa. It is still very much a growing tradition with very few truly skilled academics operating in this space. This can be seen by the number of qualitative articles published in South African management journals compared to quantitatively orientated articles. A scan of three of the leading South African open-access management journals revealed the following proportions of quantitative versus qualitative articles for the 10-year period between 2005 and 2014.

Table 1 points to the dominance of quantitative methods -normally associated with scholarly work of a positivistic nature - in the scholarly endeavour of business management and related disciplines in South Africa.

It is against this backdrop that the notion of CMS is explored. The endeavour is not an attempt to incite a revolt against more mainstream and established traditions that dominate thought, research and education within this academic domain. Rather, it is an attempt at creating awareness amongst South African management scholars as to the potential of CMS for providing insight into issues at which mainstream scholarly endeavour is limited. Thus, Chapter 1 sets out to explore how CMS can complement more established traditions rather than compete with them or negate them.

Chapter 1, firstly, gives a brief outline of the evolution of CMS as an emergent paradigm within the domain of business management. Thereafter, the nature of CMS as a school of thought is expounded. The discussion attempts to highlight the applicability of CMS to the South African context. Chapter 1 concludes by suggesting areas of inquiry that would be best suited to sense making through the application of critical-orientated methodologies such as CMS.

The evolution of CMS

It is widely acknowledged that CMS originated with Alvesson and Willmott's seminal work published in 1992 (Grey 2004; Learmonth 2007), yet work displaying similar notions had already been done before the publication of Alvesson and Willmott's work (e.g. Anthony 1986; Clegg & Dunkerley 1977). The CMS label affirmed by Alvesson and Wilmott's work acted as a sort of repository for inquiry with a critical orientation related to business management (Fournier & Grey 2000; Grey 2004).

Alvesson and Wilmott (2012) indicate that the advancement of Western society has seen the emergence of two dominating forces, namely capitalism and science. The business organisation, as it is conceived today, emerged during the Industrial Revolution and can thus be seen as an instrument through which capitalist activity takes place (Goldman, Nienaber & Pretorius 2015; Westwood & Jack 2007). The Industrial Revolution also witnessed the advent of formal inquiry into business and how it is to be administrated or managed, as is evident, for example, from the rapid growth of Taylor's notion of scientific management in the early 20th century and the resultant burgeoning of business schools in the USA (Stewart 2009).

However, it was the same Industrial Revolution that also witnessed the first major critique of capitalism and the instrument thereof (referring to the business organisation) in Karl Marx's thesis of the class struggle (Alvesson & Wilmott 2012; Sulkowski 2013). Although influential in shaping CMS, Marx's thesis is but one of many criticisms of capitalism, business organisations and the management of these business organisations. Indeed, influential thinkers from the discipline of sociology (such as Durkheim and Weber) have been critical of capitalism and business organisation especially in terms of its propensity for exploiting human beings (Alvesson et al. 2009).

Contemporary CMS draws from, and builds upon, a wide array of traditions, and consequently, it is difficult to pinpoint an exact lineage or chronology of events that has resulted in contemporary CMS. It has been enthused by many scholars and traditions such as Marx, Weber, Foucault, the Frankfurt School, labour-process theory, moral philosophy, poststructuralism and postcolonialism (Alvesson et al. 2009; Dyer et al. 2014; Fournier & Grey 2000; Grey 2004). Despite these diverse and often differing points of departure, CMS thinking seems to converge in a conception that acknowledges management as a function of history and culture (Alvesson & Deetz 2006; Grey 2004). Subsequently, CMS has grown into a multidisciplinary, pluralistic tradition which can be (to those new to, or unfamiliar with CMS) quite confusing and which has endured its fair share of attacks in terms of its scholarly project (Alvesson et al. 2009). However, the binding force behind CMS seems to be the endeavour to strive for a less discordant, less oppressive and less exploitative form of business management practice within a more morally focused political economy (Adler et al. 2007; Clegg, Dany & Grey 2011; Dyer et al. 2014).

An attempt at defining CMS

Understanding exactly what CMS is, is tantamount to catching an eel with rubber gloves. The more one reads up on the issue, the more elusive it becomes. Any attempt to define CMS is fraught with difficulty, and therefore, Chapter 1 does not attempt to put forward a working definition of CMS. Rather, different definitions will be interrogated to extract common themes from these definitions to describe the nature and characteristics of CMS.

Many authors point out that there is no singular definition of CMS as there is no singular set of parameters that accurately define it (Adler et al. 2007; Alvesson et al. 2009; Alvesson & Willmott 2012; Dyer et al. 2014; Fournier & Grey 2000; Grey 2004; Spicer, Alvesson & Karreman 2009). In its simplest form, CMS is (Parker 2002):

[A]n expression of certain authors' political sympathies, insofar as expressing sentiments that are, inter alia, broadly leftist, pro-feminist, anti-imperialist and environmentally concerned. These expressions also reflect a general mistrust of positivist methodologies within the broader realm of social sciences. The expressions mentioned manifest in an endeavor to expose moral contradictions and inequitable power relationships within the organisational context. (p. 117)

This broad sketch of CMS discloses that inquiry is dependent on the worldview of the person conducting the inquiry, that is, the researcher. Put differently, CMS requires a particular mind-set from the researcher. To be a critical-theory2 scholar thus implies far more than being critical of the world around us and of objects of inquiry. The critical scholarly endeavour is one of a deep-seated belief in the fallibility of the mainstream (or dominant) understanding of the world around us, of the methods of inquiry used to develop this mainstream view and of the paradoxes created by this mainstream thinking (Adler 2002; Cimil & Hodgson 2006; Spicer et al. 2009).

Alvesson and Willmott (2012:19) offer the following insights into CMS: 'The critical study of management unsettles conventional wisdoms about its sovereignty as well as its universality and the impartiality of its professed expertise.' This excerpt highlights another important aspect of CMS: Apart from distrusting mainstream thinking, CMS challenges the political neutrality of mainstream or conventional wisdom (Alvesson & Willmott 2012). As an institution rooted within the mechanisms of capitalism, business management often assumes a position of being beyond refute. It also assumes an iconic status brought about through legitimisation on ontological, epistemic and moral grounds (Sulkowski 2013) as managers are seen as conveyors of management reality, and the managerial structure of a business itself is seen as the quintessence of expert knowledge on business management and as the instrument of justice and democracy in the workplace (Fournier & Grey 2000).

Thus, the techniques of business management have taken precedence over the politics of business management. This has resulted in the mainstream view that management entails techniques and processes that are symbolising neutral facts (Grey 2004). At its very heart, business management is a social endeavour, and as such, it is political because social practices and institutional relationships influence (to a lesser or greater degree) strategic decisions, operating procedures and business models (Alvesson et al. 2009). This social and political side of business management implies a value-laden reality (Clegg et al. 2011; Grey 2004). The mainstream obsession, therefore, with neutral fact has maligned the value-ladenness that should be associated with business management as a social science. CMS does not wish to ignore the fact but rather promote the stance that facts are imbued with values.

A case in point could be a company's outlook on community development. Irrespective of whether the company in question takes this issue to heart and operates from a position of true commitment to the cause, or whether it is merely a public relations exercise to tick the appropriate boxes as far as social responsibility is concerned, a decision was made in terms of which direction this company should go. The decision to commit or comply is in itself a value judgement on the part of the decision maker.

Grey (2004) states the following:

[Tjhe field of management studies is already and irredeemably political, and the distinction between the critical position and others is not one of politicization but one of the acknowledgment of politicization. (p. 179)

This statement by Grey reflects the CMS position that business management (and other social sciences) cannot be neutral, despite efforts to appear so. More often than not, the practice and scholarly endeavour of business management is convened as a reality that consists only of its own activity, thus ignoring or denying the political activity of this reality (Knights & Murray 1994). By so doing, the act of management becomes an ideology that legitimises the use of power to rationalise the position of management (Sulkowski 2013). This ideology, then, contributes to the creation of identity and group solidarity. Harding (2003) attests that this ideology, referred to as managerialism, has created a huge system of the social legitimatisation of this power through institutions such as consulting firms, business and management faculties, business schools and publications. The net effect of this encroachment of managerialism into societal bodies means that CMS, as a critique on managerialism, is not only the concern of practice and scholarly endeavour but also of education. Indeed, sprouting forth from the CMS tradition has been a specialisation concerning itself with critical management education (CME) (Clegg et al. 2011; Grey 2004; Learmonth 2007).

From the above, it is evident that CMS is a complex body of interrelated views. However, irrespective of the finer detail, certain commonalities are evident from the profusion of views concerning its exact nature. CMS thus:

• Relies on a disposition assuming the fallibility of mainstream convention on the part of the inquirer.

• Challenges the political neutrality of conventional businessmanagement thinking and as such recognises that business management is a function of historical and cultural contexts.

• Accepts a value-laden reality and is sceptical of claims based entirely on the outcome of science at the expense of the values that underlie these claims.

• Is sceptical of the ideology presented by managerialism as this often legitimises practices that are morally questionable.

In summary thus, CMS requires a particular disposition on behalf of the researcher. It further urges us to see business management as part of a bigger whole, and it is weary of the exploitative potential of the commercial and managerial system.

Central tenets of CMS

In order to achieve the purpose set out in the previous section, CMS needs to rely on a set of guiding principles. Fournier and Grey (2000) provide a point of departure in this regard, stating that CMS takes the following position (also see Grey & Willmott 2005):

• It aims to denaturalise, that is, it interrogates notions of business and management that over time are taken for granted and are often legitimised as 'the way things are'. Alvesson et al. (2009) employ the analogy of organisational hierarchy to prove the point. A person that occupies a higher position than others in the organisational hierarchy (the manager) is assumed to possess more knowledge and skills that are scarcer, which in turn legitimises their high level of remuneration as the manager has greater responsibility to bear. Such manifestations of an individualist possessive ideology are challenged by CMS, arguing that the locale within which management functions should not necessarily attest to such notions.

• It is reflexive, in other words, it recognises that all accounts of business management as an area of inquiry are advanced by the specific tradition to which its scholars ascribe. Reflexivity extends a particular epistemic challenge to logical positivism that seemingly pervades mainstream research in business management and related disciplines. CMS is sceptical of the possibility of neutrality and universality in business-management research, as such notions are (at least in part) seen as furthering a research agenda which ignores parochial theory-dependency and refutes the notion of perpetuated naturalisation. In an effort to generate objective facts, mainstream business-management research discounts the values which guide not only what is being researched but also how it should be researched. Mainstream research represents weak (and often absent) reflexivity, and little attention is given by knowledge users to question the assumptions and routines upon which knowledge production is grounded. CMS views such critique as mandatory, not only of other traditions but more intensively of its own claims and how they are conditioned by context, history and culture.

• It takes a non-performative, stance. Alvesson et al. (2009) attest that business-management knowledge has value only if it can (in principle at least) be applied to enhance the achievement of existing outcomes. These outcomes are normally also naturalised notions. An anti-performative stance rejects the notion that knowledge has value only if applied and purports that new, denaturalised outcomes should be sought and that businessmanagement knowledge should augment outcomes that do not promote the agenda of mainstream business-management thinking. Often, anti-performativity is construed by those not familiar with CMS as a rejection of any notion of having pragmatic value, thus reducing CMS to the realm of the esoteric and the cynical and isolating it as a negative practice. At its very core, CMS tries to evoke change as is typical of scholarly endeavour that proceeds along the critical-theory trajectory. By way of an example, consider business-management research conducted within indigenous communities in South Africa. Very often, such research aims to understand the nature of these communities (in terms of value systems, behaviour, et cetera) in an effort to adapt managerial practices to more efficiently and effectively manage employees emanating from these communities. However, the conceptual flaw here, which the anti-performative stance attempts to address, is that at the very heart of such an endeavour is still an agenda of focusing on organisational goals and targets to pursue maximum productivity. An anti-performative stance would pursue a different agenda with such research. Typically, it would imply a movement away from organisational targets and outcomes whilst actively seeking alternative outcomes in fostering relationships between an organisation and its stakeholders. The question then becomes not 'How can the organisation better manage these stakeholders' but rather 'How can the unique stakeholder demands influence the organisation to foster better relations with these stakeholders for the benefit of all parties concerned.' Anti-performativity is a much debated issue within the CMS community with hard-lined proponents for and against it. The stance taken in Chapter 1 (presented above) is what Spicer et al. (2009) refer to as 'critical performativity', which is more of a moderate stance in terms of anti-performativity.

From the preceding discussion, it is apparent that CMS is a radical endeavour, which is often at the heart of critique against CMS. It would seem as though mainstream business-management thinking is so firmly entrenched in business-management scholars that the search for plausible alternatives seems a very daunting prospect. It is this dearth of any plausible and practical alternatives to the managerial project that seems to be a serious threat to the credibility of CMS as a movement.

Despite these sentiments, CMS forces business-management scholars to move outside of their traditional comfort zones. As the basic point of departure in CMS is scepticism towards scientism and mainstream thinking, CMS scholars also tend to be sceptical of mainstream management literature and thus look at other bodies of literature to ground their work. Mainstream management literature tends to ignore points of view from outside the managerial project that deal with issues of organisation and management. A point in case is the work of Michel Foucault, whose thought is widely recognised in the area of industrial sociology. However, within business management and related disciplines, the work of Foucault is virtually unknown (Goldman et al. 2015).

Now that a broad exposition has been offered of what CMS entails, the discussion shifts toward the possible areas of application of CMS within the South African context.

The possibilities for CMS in the South African context

If one recognises the social and value-laden nature of business management, as well as the notion that mainstream businessmanagement thinking is an extension of Western capitalism that has created a subversive power base that seeks domination and control to maintain the status quo and to suppress or marginalise divergent thought (Deetz 1995), then the potential of CMS to the play a more prominent role in the discourse on business management in South Africa (and the rest of Africa, for that matter) becomes glaringly obvious.

A logical, yet underexplored, extension of CMS is the anthropologically imbedded discourse of postcolonialism (Westwood & Jack 2007).

The conception of postcolonialism is one of a 'retrospective reflection on colonialism, the better to understand the difficulties of the present in newly independent states' (Said 1986:45). As such, postcolonial inquiry seeks to thematise and challenge matters arising from colonial associations (Banerjee 1999; Joy 2013).

Although it has risen to prominence in recent times in the realms of the humanities, most noticeably anthropology, literary studies and history (Banerjee 1999; Westwood & Jack 2007), it must be stressed at this point that postcolonialism is fraught with ambiguity, both theoretically and politically (Kandiyoti 2002; Shohat 1992). Most noticeably, the prefix 'post-' signifies a state of affairs 'after' colonialism. However, there is no exact timeframe that denotes the end of colonialism and the start of a postcolonial order (Westwood & Jack 2007). In fact, in many postcolonial nation states, traces of colonialism still remain, but these are either disregarded or disguised as economic progress and development (Banerjee 1999; McKinnon 2006; Nkomo 2015). Through claims of prioritising the agenda of the marginalised and disenfranchised 'other' (Muecke 1992), postcolonialism tends to have scant regard for the present consequences brought about by colonisation. Through continuing disparity in power relations between 'coloniser' and 'colonised', pre-specified courses of action are imposed in the name of progress (Kayira 2015; McClintock 1992). The nett effect is that colonialism is perpetuated. Only now, it takes on an economic semblance rather than an imperialist one.

Another strong critique of postcolonialism arises from the assumption that all countries that were once colonised share a common past in terms of their contact with Europe (Banerjee 1999), thus ignoring historical and cultural differences between different countries. This renders postcolonialism a culturally universal endeavour typified by singularity of thought and ahistoricity (Mani 1989; McClintock 1992; McEwan 2003; Prakash 1992; Radhakrishnan 1993).

Despite these points of critique against postcolonialism, many authors highlight the applicability of postcolonial inquiry to the realm of business management and organisation theory (Cooke 2003; Jack & Westwood 2006; Johnson & Duberley 2003; Westwood 2001), especially if one bears in mind that 'modern management theory and practice was also borne in the colonial encounter, founded on a colonizing belief in Western economic and cultural superiority' (Westwood & Jack 2007:249).

Jack and Westwood (2006) remind us that business management as a scholarly endeavour exhibits a strong continuity with the colonial project by striving for universality, the promulgation of the unity of science and the marginalisation of non-Western traditions through essentialising modes of representation offered under the auspices of legitimate knowledge. The result is that business management, as an intellectual and pragmatic enterprise, has lost its historical, political and institutional locations.

The South African context is one that exhibits a particular location in terms of culture and history as is the case with any other nation states that had fallen victim to colonialisation. This location is not necessarily compatible with the location represented in the 'mainstream' conception of the intellectual enterprise of business management and organisation theory. Without embarking on a detailed discussion of South African history and the socio-cultural, political and economic legacies that developed during this history, suffice it to mention at this juncture that South African history can be viewed as having four distinct eras.

The first of these four eras can be seen as pre-colonial. It is argued that Homo sapiens sapiens evolved in the southern part of Africa. Indeed, archaeological evidence from the Blombos caves in the Witsand area of the Western Cape province affirms the earliest 'jewellery' known, dated back some 75 000 years (Mellars 2007). By the 17th century, the region which is now South Africa was inhabited by various groups of people, most noticeably the Khoikhoi and San people in the west (Barnard 2007), the Zulu and Xhosa people in the east and tribes which would later be known as the Sotho and Tswana people of the central and northern regions (Shillington 2005).

The arrival of the Dutch on 06 April 1652 (Hunt & Campbell 2005) ushered in the era of colonialism in the region. Initially intended as a shipping station for the long sea voyages from Europe to the East (Comaroff 1998), the strategic value of the Cape of Good Hope soon became apparent for the power that controlled this waystation had control of the shipping routes between Europe and the East (Hunt & Campbell 2005). This resulted in the establishment of a strong Dutch presence in the Cape of Good Hope, which in turn meant that more land, local labour and local resources were needed to sustain this presence (Comaroff1998), resulting in the development of a distinct colony by the end of the 17th century.

This era of colonisation had a distinct Dutch and British component because the Cape of Good Hope (also called the Cape Colony) was annexed by Britain and formally became a British colony in 1806 after another short period of British rule from 1795 to 1803 (Comaroff 1998). British colonisation had a distinct effect on South African history. Under Dutch rule, the Cape Colony witnessed the subjection of indigenous peoples to Dutch imperialism (Welsh 1998). However, British imperial rule marked more widespread subjection. Not only were indigenous people subjected to a different form of imperialism (British as opposed to Dutch), but Dutch settlers (known as Boers) who had become 'naturalised' inhabitants of the Cape Colony (in many cases 3rd or 4th-generation people born in the Cape) also became subjected to British imperial rule (Comaroff 1998). This marginalisation of the Boers lead to widespread resentment against the British (Thomas & Bendixen 2000) and can be seen as the root of a liberation movement amongst Dutch speaking settlers, which would eventually crystallise in the Great Trek of the late 1830s (Ransford 1972) and later on in the rise of Afrikaner Nationalism in the 1930s (Prozesky & De Gruchy 1995).

The Great Trek of the 1830s resulted in the establishment of three Boer Republics, Natalia (1839), the Oranje Vrij Staat (OVS, Orange Free State) in 1854 and the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR, South African Republic) in 1852 (Eybers 1918). Although Natalia was annexed by the British in 1844 (Eybers 1918), the OFS and ZAR established themselves as autonomous republics and functioned independently until the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging which marked the end of the South African War (also referred to as the Second Anglo-Boer War) in 1902 (Meredith 2007). The establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910 laid down the geographical boundaries of South Africa as it stands today (Adu Boahen 1985).

The Union of South Africa marked the establishment of an independent dominion of the British Empire ruled as a constitutional monarchy, the British crown (monarch) being represented by a governor-general (Comaroff 1998; Thompson 1960). Initially ruled by a white, pro-British minority striving for white unity, a more radical National Party gained power in 1948. The National Party strove for independence from Britain and championed Afrikaner interests, very often at the expense of the interests of others (Thompson 1960). Under National Party rule, many of the 'apartheid laws' were passed in the 1950s and early 1960s (Meredith 1998). During this time, the disenfranchisement of indigenous people along with other non-white groupings in South Africa that came about through the import of slaves in the 17th and 18th centuries was heightened (Thomas & Bendixen 2000) and entered global consciousness under the term apartheid. The Nationalists gained independence from British rule (1961) in an era when colonial 'masters' had begun to relinquish political control, thus allowing former colonised territories to enter the fray as independent nation states (Peter 2007).

The third distinctive era of South African history is the apartheid era, which started, as mentioned above, with the rise to power of the National Party in 1948 and lasted until the first fully democratic elections took place on 27 April 1994 (Comaroff 1998). During this period, the disenfranchisement and marginalisation of non-white segments of the population reached its peak, and concurrently, protest action and guerrilla military action against the National Party government and the apartheid project also reached its apex (Ellis & Sechaba 1992; Meredith 1988). The international community also took action as the UN enforced economic sanctions against South Africa in 1985 (Knight 1990).

In 1994, South Africa witnessed the advent of the fourth era, that of the emergence of South Africa as a full democracy. However, as will always be the case in a heterogeneous society, the shift of power from minority rule to majority rule resulted in minority groups feeling marginalised because of efforts at 'redressing the imbalances of the past' (Anonymous 2008).

In summary, South Africa has witnessed a complex and at times violent and irrational history. In all of the eras outlined, certain groupings of this increasingly diverse society have been marginalised and disenfranchised to a lesser or greater extent. As far as the nature of business and management in the South African context is concerned, the net result of this history is that business ownership and management is seen as 'white' and labour is seen as 'black' (Thomas & Bendixen 2000). This statement is somewhat of a generalisation as initiatives such as Employment Equity and Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment have seen an increase in black ownership and management, albeit at a relatively slow pace (Booysen & Nkomo 2006; Du Toit, Kruger & Ponte 2008).

The scenario presented above has led to a huge politicisation of labour unions in South Africa as well as widespread labour unrest which has had a marked influence on decisions concerning foreign direct investment as well as the general economy of the country. Occasionally this unrest takes a violent turn as seen during the events that unfolded at Marikana in August 2012. The core of this tension can be drawn back to the fact that the predominantly white management corps (Booysen 2007) employs Western principles of management that are in direct conflict with the values of the predominantly black labour force that are rooted in an African value system.

The immanent challenge of business management in South Africa thus seems to be not only to search for effectiveness and efficiency and, by so doing, to create value for the stakeholders of the organisation. Business management should have a far broader focus. This challenge implores us to revive and formalise the indigenous knowledge schemes unique to South Africa and its people with a view of addressing the inequitable power imbalances that exist in the South African business context. Williams, Roberts and McIntosh (2012) attest that much wisdom exists in terms of communal ethics pronounced by many indigenous societies. Dyer et al. (2014) add to this notion, stating that the wisdom prevalent within indigenous knowledge systems holds significant potential to help radically transform ostensibly immovable social and environmental issues facing not only management but humanity in general.

Indigenous knowledge can foster an interest in and appreciation of diverse ideas as a heuristic for developing scholars and business professionals who can promote the idea of justice and who can contribute to renewal of the environment (Dyer et al. 2014). One does see efforts to develop the type of heuristic eluded to above, as the transition to a full democracy in the early 1990s saw much energy around transformation in all spheres of South African society, with business management being no exception (Goldman 2013). In the mid-1990s, the so-called South Africa Management Project (SAMP) was launched under the auspices of Ronnie Lessem, Barbara Nussbaum, David Christie, Nick Binedell and Lovemore Mbigi (Van der Heuvel 2008). SAMP promoted the African cultural value of ubuntu as a vehicle for greater cohesion and purpose within South African business organisations (Christie, Lessem & Mbigi 1994). Although, as an academic project, SAMP did not survive beyond the 1990s, it witnessed (and was in part responsible for) a heightened consciousness around ubuntu as a value system that could be utilised by management (Goldman 2013). However, it would also seem that much of the momentum built up around ubuntu by SAMP during this period has apparently faded during the past 10 years. SAMP can also not be seen as a critical endeavour. In as much as SAMP did challenge institutionalised beliefs around value systems in South African organisations, it seems that SAMP was a performative exercise as it used ubuntu as a tool or mechanism to further mainstream management thinking that is centred around increased organisational efficiency and effectivity. Indeed, some of the minds behind SAMP profited quite generously from the resultant businessconsulting spin-offs. Nonetheless, SAMP did serve a purpose, which was to expose the potential of indigenous knowledge to contribute to business-management discourse.

For CMS to gain a foothold in South Africa, it is important to establish what is meant by 'indigenous'. Certainly, when one thinks of indigenous in the South African context, one immediately thinks of the ethnic black people of South Africa. However, are these the only people indigenous to South Africa? Immediately apparent are the so-called 'coloured' (or 'brown') people of South Africa. The coloured people are of varied origin, including the lineage of Malay and Indonesian slaves brought to the Cape by the Dutch as well as indigenous Africans and settlers of European decent. Denoting a group of people as 'coloured' seems to be unique to South Africa as anywhere else in the world 'black' and 'coloured' would refer to the same group of people. In the South African context though, the term has come to denote a specific and uniquely South African group of people and their culture as opposed to a distinction on the basis of mere race. Should one therefore consider coloured people to be indigenous even though part of their lineage can be traced back to non-South African origins? In my opinion, coloured people do constitute a uniquely South African group of people and should thus be considered as indigenous. The same can be said of most groups of people that make up the South African population that can be traced to non-South African origins. Although part of the colonial process, white South Africans (and arguably, the Afrikaner more so than other white South African groupings), through generations of naturalisation, have developed an identity which is markedly different from that of their European ancestors. Does this not make them uniquely South African and therefore indigenous? The point is that, in order to address uniquely South African challenges, wisdom needs to be sought from everybody who inhabits and understands this realm. To exclude certain groups from this endeavour on the basis of historic lineage would marginalise the wisdom of a significant portion of the population. Therefore, the common denominator is 'South African'. In other words, the call is to actively search for South African knowledge that can address South African issues in business and management and not merely perpetuate Americanised notions of Western capitalism in business management education, research and practice.

Conclusion and personal reflection

In an academic environment typified by the pervasiveness of positivist scholarship in business management and related disciplines, there seems to be a growing sentiment amongst academics that operate within this academic domain that the positivist endeavour does not have all the answers to the issues faced by business and its stakeholders in the South African context. Increasingly, businessmanagement academics are exploring alternative epistemologies and methodologies to address these issues.

It must be stressed, however, that, although the position in Chapter 1 could be seen as an outright attack on positivism, this is not necessarily the case. The claim is not that positivism is deemed insufficient or of lesser standing. However, one needs to be open to the notion that different epistemologies are appropriate at different times and in different circumstances. As a science of verification, positivism has a definite role to play in building a body of evidence concerning the nature of the world around us. The problem is that, all too often, scholars want to prove the infallibility of a certain methodology above all else.

Positivism, as a science of verification, can complement CMS in a very definite manner. As positivistic scholarship attempts to build up a body of irrefutable evidence to explain reality, scholars embark on replication studies. If the same findings are made, more evidence is added. However, what happens when contradictory findings arise from replication studies? Could that not in itself act as impetus for critical inquiry into these contradictions? The inverse could also be asked. If an alternate reality can be proposed through critical scholarship, why can a body of accompanying evidence not eventually be built to support these suppositions? All these scenarios are possible if one seeks areas of support between different epistemologies instead of seeking for areas of contradiction.

It seems that there is enough space to grow CMS as a research paradigm in the South African milieu. However, further investigation is needed to assess the direction that CMS must take in the South African context. Furthermore, before such a direction can be established, it would also be prudent to gauge the current level of understanding of the notion of CMS amongst South African business-management scholars and to bring together a critical mass of scholars interested in pursuing such an endeavour. Preliminary and informal discussions with fellow business-management scholars have indicated that such a critical mass would be possible, but this needs to be investigated in greater detail.

The (documented) history of South Africa has culminated in the disenfranchisement of many of its people. Although political democracy has triumphed and integration on a social level has gained momentum, economic and intellectual disenfranchisement is still an issue. With intellectual disenfranchisement, the problem is not that previously marginalised people are not gaining access to education and skills development. Rather, intellectual disenfranchisement speaks to the postcolonial notion of the perpetuation of the colonial knowledge system (Mbembe 2016). Within the parameters of the scholarly endeavour of business management, this relates to Western capitalism and a perpetuation of mainstream business-management thinking. With the exception of the (now largely subdued) notion of ubuntu, precious little wisdom located indigenous knowledge systems has filtered through into the business-management discourse in South Africa. Through its very nature, CMS has the potential to redress this situation, making local knowledge more powerful in the endeavour to meet local challenges.

The student protests in South Africa that commenced in mid-October 2015 and that have become known as the #FeesMustFall campaign demonstrate the urgency of addressing this notion of intellectual disenfranchisement. Although the main focus of the #FeesMustFall campaign was the demand for free tertiary education, the students' list of demands included a so-called 'decolonisation of the curriculum', representing nothing less than an urgent call to address the pervasive intellectual disenfranchisement evident in South African education institutions. Decolonisation of the curriculum refers to the promotion and dissemination of knowledge produced by local, indigenous scholars. It urges a basic re-examination of the relevance of the knowledge produced and disseminated by universities (and other higher education institutions) by way of the curricula they pass on to students. The notion of decolonisation of the curriculum also rallies for a shift in the 'geography of thought' away from a European or American focus toward a focus of African thought, knowledge and wisdom (Higgs 2012; #FeesMustFall 2015). CMS has the potential to deal with the challenge of the 'decolonisation of the curriculum' especially if CMS in the South African context is centred around issues of postcolonial discourse within the domain of business management.

If CMS is to prosper as an intellectual endeavour in South Africa, the champions thereof need to establish exactly what they should be critical about. This implies more than merely establishing the direction that CMS must take in the South African context. 'Direction' speaks more specifically to what should be studied in the South African context. To decide on 'what we should be critical about' implies the degree of radicalism that should be employed in South Africanised CMS and the degree of pragmatism that should be associated with South Africanised CMS.

References

Chapter 1

Adler, P.S., 2002, 'Critical in the name of whom and what?', Organization 9(3), 387-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/135050840293003. [ Links ]

Adler, P.S., Forbes, L.C. & Willmott, H., 2007, 'Critical management studies', The Academy of Management Annals 1(1), 119-179. [ Links ]

Adu Boahen, A., 1985, General history of Africa, vol. VII, University of California Press, London. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M., Bridgman, T. & Willmott, H., 2009, The Oxford handbook of critical management studies, Oxford University Press, London. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M. & Deetz, S., 2000, Doing critical management research, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M. & Deetz, S., 2006, 'Critical theory and postmodernism approaches to organisational studies', in S.R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T.B. Lawrence & W.R. Nord (eds.), pp. 255-283, The Sage handbook of organisational studies, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Alvesson, M. & Willmott, H., 2012, Making sense of management: A critical introduction, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Anonymous, 2008, 'Between staying and going: Violent crime and political turmoil are adding to South Africa's brain drain', The Economist, 25 September, viewed 27 August 2015, from http://www.economist.com/node/12295535. [ Links ]

Anthony, P., 1986, The foundation of management, Tavistock, London. [ Links ]

Banerjee, S.B., 1999, 'Whose mine is it anyway? National interest, indigenous Stakeholders and Colonial discourses: The case of the Jabiluka Uranium Mine', paper presented at the Critical Management Studies Conference, Manchester, UK, 14-16th July. [ Links ]

Barnard, A., 2007, Anthropology and the Bushman, Berg, Oxford. [ Links ]

Booysen, L., 2007, 'Barriers to employment equity implementation and retention of blacks in management in South Africa', South African Journal of Labour Relations 31(1), 47-71. [ Links ]

Booysen, L. & Nkomo, S.M., 2006, 'Think manager - Think (fe)male: A South African perspective', International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 2006(1), 23-33. [ Links ]

Christie, P., Lessem, R. & Mbigi, L., 1994, African management: Philosophies, concepts and applications, Knowledge Resources, Randburg. [ Links ]

Cimil, S. & Hodgson, D., 2006, 'New possibilities for project management theory: A critical engagement', Project Management Journal 37(3), 111-122. [ Links ]

Clegg, S., Dany, F. & Grey, C., 2011, 'Introduction to the special issue critical management studies and managerial education: New contexts? New Agenda?', M@n@gement 14(5), 271-279. [ Links ]

Clegg, S. & Dunkerley, D., 1977, Critical issues in organizations, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Comaroff, J., 1998, 'Reflections on the colonial state, in South Africa and elsewhere: Factions, fragments, facts and fictions', Social Identities 4(3), 301-361. [ Links ]

Cooke, B., 2003, 'A new continuity with colonial administration: Participation in management development', Third World Quarterly 24(1), 47-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713701371. [ Links ]

Deetz, S., 1995, Transforming communication, transforming business: Building responsive and responsible workplaces, Hampton Press, Cresskill. [ Links ]

Du Toit, A., Kruger, S. & Ponte, S., 2008, 'Deracializing exploitation? Black economic empowerment in the South African wine industry', Journal ofAgrarian Change 8(1), 6-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00161.x. [ Links ]

Dyer, S., Humphries, M., Fitzgibbons, D. & Hurd, F., 2014, Understanding management critically, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Ellis, S. & Sechaba, T., 1992, Comrades against apartheid: The ANC & the South African Communist Party in exile, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IL. [ Links ]

Eybers, G.W., 1918, Select constitutional documents illustrating South African history, 1795-1910, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Fournier, V. & Grey, C., 2000, 'At the critical moment: Conditions and prospects for critical management studies', Human Relations 53(1), 7-32. [ Links ]

Goldman, G.A., 2013, 'On the development of uniquely African management theory', Indilinga African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems 12(2), 217-230. [ Links ]

Goldman, G.A., Nienaber, H. & Pretorius, M., 2015, 'The essence of the contemporary business organisation: A critical reflection', Journal of Global Business and Technology 12(2), 1-13. [ Links ]

Grey, C., 2004, 'Reinventing Business Schools: The contribution of critical management education', Academy of Management Learning and Education 3(2), 178-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2004.13500519. [ Links ]

Grey, C. & Willmott, H., 2005, Critical management studies: A reader, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Harding, N., 2003, The social construction of management, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Higgs, P., 2012, 'African philosophy and decolonisation of education in Africa: Some critical reflections', Educational Philosophy and Theory 44(2), 38-55. [ Links ]

Hunt, J. & Campbell, H., 2005, Dutch South Africa: Early settlers at the Cape, 1652-1708, Matador, Leicester. [ Links ]

Jack, G. & Westwood, R., 2006, 'Postcolonialism and the politics of qualitative research in international business', Management International Review 46(4), 481-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11575-006-0102-x. [ Links ]

Johnson, P. & Duberley, J., 2003, 'Reflexivity in management research', Journal of Management Studies 40(5), 1279-1303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00380. [ Links ]

Joy, S., 2013, 'Cross-cultural teaching in Globalized Management Classrooms: Time to move from functionalist to postcolonial approaches?', Academy of Management Learning and Education 12(3), 396-413. [ Links ]

Kandiyoti, D., 2002, 'Postcolonialism compared: Potentials and limitations in the Middle East and Central Asia', International Journal of Middle East Studies 34, 279-297. [ Links ]

Kayira, J., 2015, '(Re)creating spaces for Umunthu: Postcolonial theory and environmental education in South Africa', Environmental Educanon Research 21(1), 106-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.860428. [ Links ]

Knight, R., 1990, 'Sanctions, disinvestment and US Corporations in South Africa', in R.E. Edgar (ed.), Sanctioning Apartheid, pp. 67-87, Africa World Press, Trenton, NJ. [ Links ]

Knights, D. & Murray, E., 1994, Managers divided: Organisation politics and information technology management, John Wiley, Chichester. [ Links ]

Learmonth, M., 2007, 'Critical management education in action: Personal tales of management unlearning', Academy of Management Learning & Education 6(1), 109-113. [ Links ]

Mani, L., 1989, 'Multiple meditations: Feminist scholarship in the age of multinational Reception', Inscriptions 5(1), 1-23. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A.J., 2016, 'Decolonizing the university: New directions', Arts & Humanities in Higher Education 15(1), 29-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1474022215618513. [ Links ]

McClintock, A., 1992, 'The Angel of Progress: Pitfalls of the term "postcolonialism"', Social Text 31/32, 84-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/466219. [ Links ]

McEwan, C., 2003, 'Material geographies and postcolonialism', Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 24(3), 340-355. [ Links ]

McKinnon, K.I., 2006, 'An orthodoxy of "the local": Postcolonialism, participation and professionalism in northern Thailand', The Geographical Journal 172(1), 22-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00182.x. [ Links ]

Mellars, P., 2007, Rethinking the human revolution: New behavioural and biological perspectives on the origin and dispersal of modern humans, David Brown & Co, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Meredith, M., 1988, In the name of Apartheid, Hamish Hamilton, London. [ Links ]

Meredith, M., 2007, Diamonds, gold and war: The making of South Africa, Simon & Schuster, London. [ Links ]

Muecke, S., 1992, Textual spaces: Aboriginality and cultural studies, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney. [ Links ]

Nkomo, S.M., 2015, 'Challenges for management and business education in a "Developmental" State: The case of South Africa', Academy of Management Learning and Education 14(2), 242-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amle.2014.0323. [ Links ]

Parker, M., 2002, Against management, Polity, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Peter, J., 2007, The making of a nation: South Africa's road to freedom, Zebra Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Prakash, G., 1992, 'Postcolonial criticism and Indian historiography', Social Text 31/32, 8-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/466216. [ Links ]

Prozesky, M. & De Gruchy, J., 1995, Living faiths in South Africa, New Africa Books, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Radhakrishnan, R., 1993, 'Postcoloniality and the boundaries of identity', Callaloo 16(4), 750-771. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2932208. [ Links ]

Ransford, O., 1972, The Great Trek, John Murray, London. [ Links ]

Said, E.W., 1986, 'Intellectuals in the postcolonial world', Salmagundi 70/71(Spring/Summer), 44-64. [ Links ]

Shillington, K., 2005, History of Africa, St. Martin's Press, New York. [ Links ]

Shohat, E., 1992, 'Notes on the "postcolonial"', Social Text 31/32, 99-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/466220. [ Links ]

Spicer, A., Alvesson, M. & Kärreman, D., 2009, 'Critical performativity: The unfinished business of critical management studies', Human Relations 62(4), 537-560. [ Links ]

Stewart, M., 2009, The management myth: Debunking the modern philosophy of business, WW Norton, New York. [ Links ]

Sulkowski, L., 2013, Epistemology of management, Peter Lang, Frankfurt-am-Main. [ Links ]

Thomas, A. & Bendixen, M., 2000, 'The management implications of ethnicity in South Africa', Journal of International Business Studies 31(3), 507-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-02219-3. [ Links ]

Thompson, L., 1960, The unification of South Africa 1902-1910, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Van Der Heuvel, H., 2008, '"Hidden messages" emerging from Afrocentric management perspectives', Acta Commercii 8, 41-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.3726/10.4102/ac.v8i1.62. [ Links ]

Welsh, F., 1998, A history of South Africa, Harper-Collins, London. [ Links ]

Westwood, R.I., 2001, 'Appropriating the other in the discourses of comparative management', in R.I. Westwood & S. Linstead (eds.), The language of organization, pp. 241-282, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Westwood, R.I., 2005, 'International business and management studies as an orientalist discourse: A postcolonial critique', Critical Perspectives on International Business 2(2), 91-113. [ Links ]

Westwood, R.I. & Jack, G., 2007, 'Manifesto for a postcolonial international business and management studies: A provocation', Critical Perspectives on International Business 3(3), 246-265. [ Links ]

Williams, L., Roberts, R. & McIntosh, A., 2012, Radical human ecology: Intercultural and indigenous approaches, Ashgate, Surrey. [ Links ]

#FeesMustFall, 2015, Wits FeesMustFall Manifesto, viewed 05 March 2016, from http://www.feesmustfall.joburg/manifestoss. [ Links ]

1 The names of the journals are withheld as the relevant editors' consent had not been obtained. All these journals appear on the list approved by the South African Department of Higher Education and Training. One or more of these journals are also indexed with IBSS, ISI and Scielo SA.

2 Critical theory here refers to the tradition within which CMS is rooted.