Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Obiter

versão On-line ISSN 2709-555X

versão impressa ISSN 1682-5853

Obiter vol.44 no.3 Port Elizabeth Out. 2023

ARTICLES

Drafting definitions with polisemy and semantic change in mind

Terrence R Carney

BA(Hons) MA PhD; Associate Professor, University of South Africa

SUMMARY

Legislative definitions must be as clear and precise as possible. Different sources for legislative drafting provide guidelines on how to ensure clarity and precision. Many of these guidelines provide language-related advice. However, language guidelines and linguistic principles are not the same thing. Garth Thornton's book is one of the few that suggests drafters study language to benefit their drafting techniques. He specifically mentions the link between language and society, and claims that drafters will gain by understanding how meaning (and language) change owing to societal changes. This article explores Thornton's observation by attending to the polysemy and possible semantic change of the word "strike", taken from the case of SaSrIA v Slabbert Burger Transport [2008] ZASCA 73. The article claims that social processes like lived experiences and changing perspectives function as drivers of semantic change. These changes lead to the development of new semantic variations that coexist with the old or base meaning of a word, resulting in polysemy. Polysemy has the potential to cause vagueness, ambiguity and uncertainty, which complicates drafters' task in producing clear and precise texts. Understanding the complexity and instability of words ahead of time could aid drafters to hone their definitions for better legal communication. To prevent unnecessary semantic pitfalls, the contribution further suggests that drafters apply their linguistic awareness (referred to as the "lexicological approach") to words chosen for definition, as well as to a selection of words deliberately left undefined.

1 INTRODUCTION

In his guide to legislative drafting in South Africa, Burger makes the important observation that legislative drafters must have a very sound knowledge of the law and its sources.1 This might seem rather obvious. What is not so obvious, however, is that drafting also requires a thorough knowledge of language, and specifically linguistics.2 Most drafting guides contain many suggestions on how to improve the language of statutes or other legal documents like contracts in favour of clarity and plain language.3However, language guidance is something entirely different from linguistics. Thornton realises this and believes that an interest in linguistics is "a desirable, perhaps essential, quality for a drafter".4 To him, a drafter will benefit from a study of language, an understanding of how the various components of language function. More importantly, drafters will gain by paying attention to linguistic changes, "how time and social forces influence meaning and usage".5 Focusing on linguistics, and the knowledge that language change occurs, might seem like an added burden to over-worked drafters, but it has a direct influence on what they do. Aitchison mentions that the universe is perpetually in a state of change and language is an obvious part of this constant process.6 Words notoriously have more than one meaning, which often results in ambiguity or vagueness. They also have the potential to gain and change meaning. Paying attention to the semantic complexity of words and their potential to change is vital to prevent statutes from turning into a "morass" of incomprehensibility.7 According to Aitchison, semantic shift often makes people nervous and desperate to preserve what they consider to be a word's "proper meaning", and to prevent an apparent decay or weakening from taking place.8 Understandably, this fear is evident in law too, because law has a need for precision, clarity and precedent. The need persists in falling back on codified examples and explanation in order to be fair in all contexts.

To illustrate the value of Thornton's observation, this article considers the word "strike", which is contested in the case of SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport.9 At the time of the case, the word was undefined, and courts relied on its ordinary meaning for guidance. The case proves helpful on two fronts: it shows that the word "strike" has more than one relevant meaning worth considering, and that a semantic change could alter the way in which speakers use and define the word, now and in the future. It also shows how important it is for drafters to pay attention to various aspects like polysemy and the impact of societal changes on semantic meaning. Of equal importance is a drafter's responsibility to test undefined words and determine whether their ordinary meanings will suffice. If a test shows that they will not, drafters must consider defining selected words to ensure clarity. According to Price, good definitions help to create models through which the legislator or contractants control the future.10 If the model is successful, it will promote readability and efficiency and improve comprehensibility.11 If the South African Special Risk Insurance Association (SASRIA) had made a linguistic measurement of "strike" ahead of time, they would have realised the benefit of describing the word in their definition clause. If SASRIA had considered the polysemous nature of "strike" and its proximity with "riot" and "public disturbance", they might not have refused a pay-out or decided to litigate.

The remainder of this contribution contains four parts. First, the author provides the facts of the SASRIA case. The article then explains what semantic change entails and follows up with an indication of the possible polysemy of "strike". The author concludes with a discussion.

2 FACTS: SASRIA V SLABBERT BURGER TRANSPORT

In 2005, the South African Transport and Allied Workers Union embarked on a lawful strike. Unfortunately, the strike turned violent, resulting in property damage.12 One of the damaged items was a truck owned by Slabbert Burger Transport, which was set alight. The truck was insured by SASRIA for the value of approximately R600 000 against any damage caused by a riot, strike or public disorder.13 The insurer claimed that the truck was not damaged by any of the perils listed in the policy document.14 Instead, the applicant in SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport tried to convince the court a quo and the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) that the word "strike" should have a modified meaning to reflect true events.15 They argued that "strike" should incorporate attributes of (among others) violence and unlawfulness. In support, the applicant referred to a dictum by Dijkhorst J, where he stated:

"Although some strikes are lawful, the fact that damage is caused introduces an element of unlawfulness, which is also the hallmark of a riot or public disorder. The activities are (also in the case of a strike where damage is caused) of a disorderly nature. In the context, violence leading to damage is a necessary ingredient."16

The applicant argued that the ordinary dictionary definition did not account for the violent action that took place.17 Indeed, some strikers did commit violent and unlawful acts: they assaulted and threatened non-striking coworkers, they damaged trucks by stone-throwing and fire, and they looted cargo.18 As a result, the applicant requested that the courts apply the eiusdem generis rule to indicate that "strike" bears the same meaning as "riot" and "public disorder".19 However, as Hurt AJA correctly pointed out, the appellant's attempts at redefining "strike" to include semantic criteria of violence and unlawfulness brought them within the semantic scope of both "riot" and "public disorder" - both perils covered by the insurance policy.20 As a result, the SCA concurred with the court a quo and found no reason to either restrict or expand the meaning of "strike"; instead, it applied the ordinary-meaning principle and kept to the dictionary definition.21

Notably, the word "strike" does have more than one meaning and one of its senses does provide for a violent strike. Why would this be? One of the plausible explanations is language change that reflects perspectives in society. The next section elucidates "semantic change" in more detail.

3 SEMANTIC CHANGE

3 1 A brief overview of semantic change

Changes occur in both the grammar and the lexicon of a language for various reasons; some are unpredictable and imperceptible; others are traceable.22 Semantic change, also known as semantic shift, is a form of language change that affects the meaning of mostly lexical words. This includes new and existing words. The meaning of an existing word either changes entirely (which means that the old meaning falls away), or a new sense is added. Change is mostly a gradual process, which means that a word's new sense will not appear immediately, and depends on a diffusion within a speech community.23 For example, the word "awful" used to mean "full of awe", but now it glosses "terrible" or "bad"; the word "bar" used to refer to a counter or barrier, but its meaning now extends to include an establishment that sells alcohol.24

Language change also happens when people encounter a new language (like that of a coloniser) and this leads to an imperfect adoption of the new language, and the handing-down of those imperfections to their children.25Afrikaans provides many examples, like "watermelon". The Afrikaans "waatlemoen" is a contraction of "water lemoen" (water orange) which used to be "water meloen" (water melon). This phonological mistake can be described as an unconscious change, because speakers are not necessarily aware of the mistake or the change taking place, which also means that changes like these are often subtle.26 On the other side, speakers can be conscious of a change and might even encourage it. Active attempts at ameliorating language serve as an example. We often see this in language targeted at minority or vulnerable groups. Think of the word "cripple", which changed to "handicapped", then to "disabled", and now we use "differently-abled". We also say "visually impaired" instead of "blind". These reflect conscious decisions to change words and their meanings in order to shift attitudes in society.27

Two powerful drivers of semantic shift are the linguistic need for expression and language use. This is rather obvious in vocabulary; when items are no longer used or concepts are no longer applicable, the words that describe them fall away and become relics.28 Think of "jerkin" which denotes a man's sleeveless leather jacket worn during the Renaissance, or "floppy disc" which describes an external data storage device used mostly in the 1980s and early 1990s. Speakers create new words or extend existing meanings to cover newly conceived inventions. For instance, "ghosting" reflects both semantic and grammatical change. "Ghost" is the original meaning and refers to an undetectable apparition, while "ghosting" is an extension of the original form, describing an immediate and unexplained break in communication resulting in one party ignoring the other. "Ghosting" is polysemous, because the newer sense connects to the older sense and coexists.

One mechanism of semantic changed is speakers' own lived experiences, which links directly to changes in society. The next section briefly explains what this entails.

3 2 Subjectification and user-based linguistic need

Today, it is widely understood that speakers cannot say or write something without also expressing a point of view.29 This so-called speaker-imprint contains expressions of the self and the representation of a speaker's perspective on the matter he or she is talking about.30 This means that language use is often subjective. According to Traugott, certain elements or constructions in language help to express subjectivity explicitly. She refers to this as a process of subjectification and defines it as the development of a word's new meaning grounded in the socio-physical world, which marks subjectivity overtly.31 Put differently, the process of subjectification is a speaker's subjective perspective on meaning flowing from his or her lived experience and the speaker's view of the world. This leads to a development of pragmatic polysemies with highly contextualised senses.32 It is especially evident in pejoratives, euphemisms, amelioration, metaphors and other connotations. Speakers' beliefs that particular words are impolite or problematic are subjective. Once an entire speech community agrees that certain words carry a particular meaning, the subjective perspective becomes the norm. For example, the word "boor" used to denote a farmer, but soon other characteristics like "uneducated", "uncultured" and "rough" became associated with the lower classes in contrast to the more sophisticated middle class. Today, "boor" refers to a bad-mannered and obnoxious person. It underwent a negative shift. Its South African cognate, "boer", maintains the denotation of "farmer" but has since developed other senses associated with identity as well, all of which are subjective.

The process of subjectification is present in the disambiguation of "strike". Its connotation with violence and disturbance is in many respects subjective, grounded in South Africans' lived experiences of violent strikes and their growing (collective) perception of these events.33 It is also grounded in the user-based linguistic need to describe what the speaker is experiencing. The notion of a violent strike is neither odd nor uncommon. Manamela and Budeli note that violence during both protected and unprotected strikes has become a cause for concern, and argue that violent strikes contribute nothing to collective bargaining.34 They also remind us that the right to strike does not extend to a right to violence.35 The fact that legislation permits an employer to dismiss an employee during an unprotected strike if he or she is guilty of intimidation or property damage and misconduct is already telling of labour strike practices and of Parliament's means of coping with these incidents.36

The word "strike" can sometimes recall daunting images, of which the Marikana strike of 2012 is probably the best example. The circumstances that played out at the Lonmin Platinum Mine led to proposed amendments to the Labour Relations Act37 as a means to address unprotected industrial action and unlawful acts such as violence and intimidation.38 Some see violent labour strikes as the result of inadequate dispute-resolution mechanisms and the ineffectiveness of the Labour Relations Act, while others consider replacement labour as the potential root of all evil.39

Police-recorded protests for the period between 1997 and 2013 saw an average of 11 protests per day, of which 10 per cent were considered violent and another 10 per cent disruptive.40 Tenza reported that 114 strikes took place during 2013 and another 88 in the following year.41 In 2014, violence accompanied strikes in the form of intimidation (246 reported cases), violent incidents (50 reported cases) and vandalism (85 reported cases).42 Records from the period 1999 to 2013 show at least 181 strike-related deaths, followed by 313 injuries; and the police arrested about 3 000 people for acts of public violence associated with industrial action.43 As Tenza has indicated, strike-related violence tends to affect innocent parties as well - non-striking workers' families are threatened or assaulted and individuals associated with safety and security are often targeted.44 There are examples in case law as well, such as SATAWU v Ram Transport South Africa (Pty) Ltd, in which the court had to address accusations of intimidation, misconduct and damage to property.45 In FAWU obo Kapesi v Premier Foods Ltd t/a Blue Ribbon Salt Water, a number of non-striking workers looked on as protesters ransacked and set their homes alight, which later extended to the burning of cars and other possessions.46 Those who identified rogue protesters were killed.47This particular strike was accompanied by death threats, assaults, arson and intimidation.48 During the Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall actions, universities across South Africa also experienced violent student strikes and insourcing protests, resulting in intimidation and property damage.49Recently, protesters of the Clover strike assaulted and murdered security guards and strikers at the University of South Africa and set property on fire at the vice-chancellor's official residence.50

Even if violent strikes in South Africa are uncommon, they form part of South Africans' perception of strikes. If we accept that the process of subjectification is altering the meaning of words like "strike", it implies that "strike" is itself polysemous. The following section briefly describes what polysemy is and considers the implications for "strike".

4 POLYSEMY OF "STRIKE"

Polysemy indicates a word's capacity to have many related meanings. Most words are polysemous. A word's original meaning often coexists alongside new extensions of the word and depends on context to determine which meaning applies. Therefore, linguists view polysemous words as containing "layers of meaning".51 Sometimes the new meaning replaces the original, or it fossilises, which means that speakers no longer recognise the relation between the old and new senses. The word "bank" is a classic example of polysemy. It can refer to an institution (Allied Bank), the building ("I'll meet you in front of the bank") or the people working there ("The bank on Church Street is always helpful"). Although these are three distinct senses, they all relate to the financial institution. It takes the German word "bank" as its base, which denotes a counter. A banker was someone who processed money on a table that separated the officer from the customer.52 The reference to "table" fossilised; it is no longer recognisable as related to the financial institution.

The terms used for original and new meanings respectively are "conventional" and "occasional" meaning.53 Conventional meaning is the established definition of a word, codified in a dictionary and agreed upon by the larger speech community. Speakers use these definitions the most often and consider them common. More importantly, they are decontextualised.54The known definition of "strike" as a (peaceful) protest is currently the conventional meaning of the word, whereas "violent strike" is bound to instances of actual violent strikes.55 Occasional meaning is sensitive to context and is a modulation of the conventional meaning in the specific context of an utterance.56 In other words, the conventional meaning either restricts or expands depending on the context. This means that when a particular labour strike is evidently riotous or an instance of public disturbance, speakers could invoke the occasional sense (that is, violent or riotous strike) because the actual context makes the applicable denotation more salient.57

Frequency or repetition is key when it comes to implementing semantic changes.58 The higher the frequency of use, the greater the potential for a word's meaning to generalise.59 Generalisation happens when a lexical item develops a new or occasional meaning that still stands in relation to its conventional meaning; it is an instance of inclusion and takes the form of superordination.60 Geeraerts illustrates generalisation with the word "arrive", which is a borrowing from the French, "arriver'. Originally, the word meant to reach the river's bank, but it now extends to indicate any destination.61Complete semantic change takes place when there is a gradual shift from the occasional to the conventional, or when the new replaces the old entirely. This signifies that when speakers say "strike", they will eventually denote "violent strike". The conventionalising and generalising of "violent strike" is already underway (or so it seems) because violent strikes have become common enough to be recognised by ordinary South Africans, the media and academic scholars.62 Violent strikes are not strange or rare occurrences anymore, even if they remain rare in comparison to most South African strikes. This means that the increase in or persistence of violent strikes will eventually lead to the word "strike" denoting "violent strike" among speakers.

Conventionally, we define "strike" as an event to protest particular labour conditions. The Oxford English Dictionary describes it as a concerted cessation of work on the part of a body of worker, to obtain some concession from the employer.63 Oxford's Historical Thesaurus reveals that a strike can be official or unofficial; it is a form of dispute and protest meant to affect labour supply in some way. Ultimately, it is a participation in labour relations. Violence as a semantic characteristic is absent, which creates the impression that strikes are usually peaceful.64 However, it does not include "peaceful" as a semantic criterion either; this too is a subjective view. At its core, "strike" describes a protest in which employees affect workflow until the employer meets certain demands.

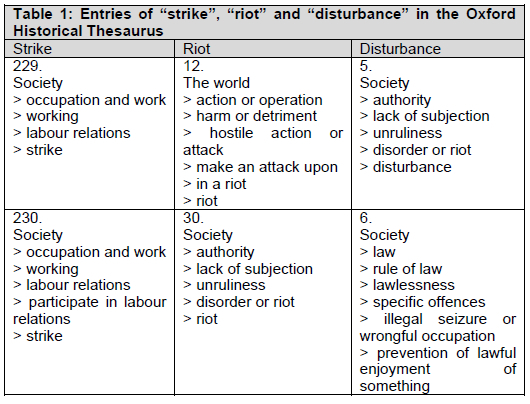

When we compare the entries for "strike", "riot" and "disturbance" (the three perils listed in the SASRIA policy) - the entries are set out in Table 1 below65 - two things become evident: "riot" and "public disturbance" are synonymous and violent strikes are very similar to riots.66 "Riot" and "disturbance" both describe an outbreak of disorder; violent action committed by a crowd, or a commotion caused by a mob. Clearly, when strikers disturb those around them and act unlawfully, the labour protest takes on riotous features. This means that we might do better to describe the occasional sense of "strike" as a "riotous strike" instead.

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Thornton says that drafters have no choice but to produce material that is as straightforward as possible and so clear that its "intended meaning is conveyed in such a way that it cannot reasonably be misunderstood".67 The author does not think such clarity is entirely possible, but he believes that drafters can come close enough if they have the necessary tools. Linguistics offers many such tools and, more importantly, it brings about an understanding that language is an instrument of thought, and a reflection of society.68 On a practical level, this is visible in the word "strike" and in the difference between its conventional and occasional meanings. As a polyseme, we can summarise "strike" as:

(1) an action to stop working in order to receive concessions from an employer (conventional sense);

(2) an action to stop working, using violence to receive concessions from an employer (occasional sense).

More importantly, if South Africans continue to perceive industrial action as violent, the meaning of "strike" will become synonymous with "riot" and "public disorder". What does this mean for interpretation? In terms of Natal Joint Municipal Pension Fund v Endumeni, understanding the semantic complexity of words will aid in deciding which one of the senses is the more sensible meaning relevant to the circumstantial facts.69 What does this mean for drafting? According to Hurt AJA, the problem was not the fact that "strike" could denote a violent event, but rather that SASRIA did not stipulate "strike" and its conditions of use.70 The practice of leaving important words undefined is partly attributable to the blurry distinction between some ordinary words on the one hand and terms of art and trade on the other. Another reason for not defining words is that drafters feel that certain words' ordinary meaning is sufficiently clear. The author thinks for the most part this is true. That said, drafters must devise a protocol or model that allows them to test ordinary words (words deliberately left undefined) to see if their ordinary meanings can stand tests of vagueness, ambiguity, plurality and the potential of changing in the immediate future. It is not enough to focus on words that seem overtly technical or unusual.

There is a potentially useful methodology that may be referred to as the "lexicological approach to drafting". Though slightly oversimplified, lexicology entails the study of various features of a word: its origin, formation, spelling, usage and meaning. Seen differently, the lexicological approach expects a drafter to study a word holistically before he or she commences with drafting a definition. In principle, drafters should apply the lexicological approach to both defined and selected undefined words.71 Before a new word is included in a dictionary, and long before the task of describing it commences, a lexicographer will monitor it for a number of years.72 The lexicographer will also study the word in detail. How do we say it? How do we write it? How do we form a particular word and any of its derivatives? To what part of speech does it belong? What meaning does it have and how many? Are any of these meanings related? The lexicographer looks at the different ways that speakers use it and labels those uses according to context and situation. Notes are made of its behaviour in sentences. It is never a simple matter of choosing a word and saying what it means. Before a lexicographer can clarify a word, he or she must understand what that word entails. Surely, the same must apply to drafters of statutes and contracts. A lexicological approach holds the following potential benefits:

• It alerts drafters, contractants and litigators to a word's possible meanings and will assist in determining which of the meanings are either vague or ambiguous.

• It helps drafters, contractants and litigators to determine which of the possible meanings is the most sensible, and therefore the preferred meaning.73

• It aids in identifying terms of art and trade among ordinary words. Sometimes, drafters leave ordinary words undefined but continue to use them as terms of art. This means the meaning of the ordinary word has shifted from its conventional use to a technical meaning. Realising this ahead of time will benefit drafters, because they can then still define the word or at least determine whether its ordinary meaning will suffice for their purpose.74

• It improves legal communication in pursuit of clarity.

• It has the potential to reduce litigation and the laborious task of repealing provisions.75

Granted, it is unrealistic to think that overburdened drafters of either statutes or contracts have enough time to do a lengthy linguistic study of each word they must define (and a host of words they choose to leave undefined). However, statutes are authoritative texts meant for many different people, including legal practitioners and ordinary citizens, and contracts are serious agreements that should reflect the best interests of both parties. Because words are the carriers of meaning and because meaning tends to be elusive, the lexicological approach expects drafters to give both defined and ordinary words more thought. Paying close attention, at least to a word's build, meaning and conventional use, will aid drafters and everyone else in the end.

With regard to the word "strike", the lexicological approach entailed a study of its polysemy and the likelihood that societal changes can affect its semantic features. Considering different aspects of "strike" illustrates that words sometimes have meanings that are different but which remain closely related. Their differences are nuanced enough that the different senses may cause uncertainty and complicate the outcome of a dispute. Understanding that a word such as "strike" is multifaceted also makes us realise that its ordinary meaning in South Africa is unstable. Therefore, relying on its ordinary meaning, or even its trade usage, is problematic. Treating it as a term of art is probably a better option. The notion that "strike" is a term and not an ordinary word is evident in the Labour Relations Act.76 The word itself occurs 113 times and the Act devotes an entire chapter to strikes and lockouts. It also helps to realise that ordinary (or dictionary) meanings have no authority; only legislative and contractual definitions do. Ordinary meaning gains authority once a court assigns authority to it. This means that a drafted definition - if drafted properly - has the power to bind people to that specific description of use in the future.77 It also means the drafter influences how people must use a certain word.78 Because the audience of a legal text is mostly heterogeneous, it is vital that drafters formulate definitions in such a manner that most users understand the text from the start.79 Considering defined and selected undefined words lexicologically could aid drafters in achieving this.

1 Burger A Guide to Legislative Drafting in South Africa (2002) 10; also see Crabbe Legislative Drafting (1994) 13.

2 Crabbe puts it a bit differently. He mentions a thorough knowledge of grammar and legal language (Crabbe Legislative Drafting 6). Indeed, they are very important for good drafting. However, grammar is only one aspect of linguistics, and legalese is a language register. Linguistics allows drafters to understand that a particular word has different meanings and it helps to explain why that might be so.

3 Burnett Commercial Contracts: Legal Principles and Drafting (2010) 50; Hawthorne and Kuschke "Drafting of Contracts" in Hutchison and Pretorius (eds) The Law of Contract in South Africa 3ed (2017) 385. Christie does not provide guidelines on the drafting of contracts, but his discussion of the interpretation of contracts stresses the importance of clarity. He mentions that disputes often arise because certain words have more than one interpretation, or because the language of the contract is poor. In the event that the contra proferentem rule must be applied, the author of the contract suffers for the incurable ambiguity. The premium on clear and precise drafting is therefore quite high. See Christie and Bradfield Christie's The Law of Contract in South Africa 8ed (2022) 258, 263, 265, 278279.

4 Thornton Legislative Drafting 4ed (1996) 3.

5 Thornton Legislative Drafting 3, 4.

6 Aitchison Language Change. Progress or Decay? (2013) 3-4.

7 Burrows Thinking About Statutes. Interpretation, Interaction, Improvement (2018) 89.

8 Aitchison Language Change 126-127.

9 SASRIA Ltd v Slabbert Burger Transport (Pty) Ltd [2008] ZASCA 73.

10 Price "Wagging, Not Barking: Statutory Definitions" 2013 60(4) Cleveland State Law Review 1017.

11 Ibid.

12 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 4.

13 Slabbert Burger Transport (Pty) Ltd v SASRIA Ltd [2007] ZAGPHC 9 par 1-2; SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 1, 3.

14 Slabbert Burger Transport v SASRIA supra par 1.18.2.

15 Slabbert Burger Transport v SASRIA Ltd supra par 1, 3; SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 8, 9.

16 South African Special Risks Insurance Association v Elwyn Investments (Pty) Ltd TPD (unreported) 1994-05-30 Case no A370/93 par 8.

17 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 10.

18 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 4.

19 Slabbert Burger Transport v SASRIA supra par 9; SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 8.

20 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 9.

21 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 10-11; Slabbert Burger Transport v SASRIA supra par 9. From both cases, it seems clear that the word "strike" was undefined by the policy document, and neither of the courts saw reason to consult the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1996. The policy-wording document (Annexure 4A) uploaded onto the SASRIA website in 2021 now defines both "strike" and "riot". The latter is defined quite specifically, but "strike" refers to the definition in s 213 of the Labour Relations Act.

22 Aitchison Language Change 16-17.

23 FuG "Language Change" in Roberts (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Universal Grammar (2017) 475-476. [ Links ]

24 Similarly, the bar (barrier) that divides a judge, lawyer and jury was extended to include the legal fraternity: the Pretoria Bar.

25 Aitchison Language Change 145. In this example, mistakes made in Dutch became standardised in Afrikaans.

26 Aitchison Language Change 56.

27 This is also known as political correctness, and usually aims at changing attitudes by introducing new words and supressing taboo terms (and behaviours). This means there is a link between language and orchestrated change. See Hughes "Changing Attitudes and Political Correctness" in Nevalainen and Traugott (eds) The Oxford Handbook of the History of English (2012) 402.

28 Aitchison Language Change 154; Traugott and Dasher Regularity in Semantic Change (2002) 11.

29 Traugott "The Rhetoric of Counter-Expectation in Semantic Change: A Study in Subjectivity" in Blank and Koch (eds) Historical Semantics and Cognition (1999) 179.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid. Not only does semantic change occur over time, it does so "in concert with broad social changes"; Hughes in Nevalainen and Traugott (eds) The Oxford Handbook of the History of English 403. In addition, see Hutton, who cites examples from English law that favour meanings that have changed because society has changed. Hutton Word Meaning and Legal Interpretation. An Introductory Guide (2014) 32-34.

32 Traugott in Blank and Koch (eds) Historical Semantics and Cognition 188.

33 Even though violent strikes in South Africa seem to be increasing, we are still dealing with perceptions. Studies analysing strike data indicate that less than 3 per cent of the workforce take part in strikes. More than 80 per cent of strikes are considered peaceful and more than 80 per cent of unionised labourers do not respond to the call to strike. Also, South Africa is on par with the rest of the world and do not strike more than other countries. According to Runciman et al (Runciman, Alexander, Rampedi, Moloto, Maruping, Khumalo and Sibanda "Counting Police-Recorded Protests: Based on South African Police Service Data" 2016 Social Change Research Unit, University of Johannesburg 15, 28, 29), about 80 per cent of protests recorded by the South African Police Service were peaceful events. See also Siwele "Most South African Workers Ignore Strike Call, Employers Say" (2021-10-07) Bloomberg; Mail&Guardian "South Africa's Strike Rate Isn't as Bad as It's Made out to Be" (2018-04-30) Mail&Guardian; Bhorat, Naidoo and Yu "Trade Unions in an Emerging Economy: The Case of South Africa" WIDER Working Paper Series wp-2014-055, World Institute for Development Economic Research.

34 Manamela and Budeli "Employees' Right to Strike and Violence in South Africa" 2013 46(3) CILSA 308 322-323.

35 Manamela and Budeli 2013 CILSA 324.

36 See Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995, and s 23(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. This kind of unlawful conduct may also be interdicted; see Basson "Some Recent Developments in Strike Law" 2000 12(1) SA Merc LJ 119 127128, 133. See also Chemical, Energy, Paper, Wood and Allied Workers Union v CTP Ltd [2013] 4 BLLR 378 (LC), and TAWUSA obo MWNgedle v Unitrans Fuel and Chemical (Pty) Ltd [2016] ZACC 28, for examples where violence is used as a criterion to determine dismissal.

37 66 of 1995, specifically ss 64, 65, 67 and 69.

38 Ngcukaitobi "Strike Law, Structural Violence and Inequality in the Platinum Hills of Marikana" 2013 34(4) ILJ 836 844-845.

39 Du Toit and Ronnie "The Necessary Evolution of Strike Law" 2012 Acta Juridica 195 195196; Calitz "Violent, Frequent and Lengthy Strikes in South Africa: Is the Use of Replacement Labour Part of the Problem?" 2016 28(3) SA Merc LJ 436 440; Kujinga and Van Eck "The Right to Strike and Replacement Labour: South African Practice Viewed From an International Law Perspective" 2018 21 Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal 1 3, 23. Along with replacement labour, Tenza mentions the deficiencies of the bargaining system and its use of balloting as contributing factors. See Tenza "An Investigation into the Causes of Violent Strikes in South Africa: Some Lessons From Foreign Law and Possible Solutions" 2015 19 Law, Democracy & Development 211 214, 219.

40 Runciman et al 2016 Social Change Research Unit 5.

41 Tenza "The Effects of Violent Strikes on the Economy of a Developing Country: A Case of South Africa" 2020 41 (3) Obiter 519 520-521. [ Links ]

42 Tenza 2020 Obiter 521.

43 Tenza 2020 Obiter 522.

44 Tenza 2020 Obiter 523. Tenza mentions that approximately 20 people were thrown off trains in Gauteng, many of them security guards. This is particularly true of replacement workers, whose lives are often in real danger; see Calitz 2016 SA Merc LJ 440.

45 SATAWU v Ram Transport South Africa (Pty) Ltd [2014] ZALCJHB 471, see par 2, 53, 68, 110 and 119.

46 FA WU obo Kapesi v Premier Foods Ltd t/a Blue Ribbon Salt Water (2010) 31 ILJ 1654 (LC) par 4.

47 FAWU v Premier Foods supra par 4. See also S v Ramabokela 2011 (1) SACR 122 (GNP), in which the appellants were convicted of kidnapping, assault and culpable homicide during a strike.

48 FA WU v Premier Foods supra par 23.

49 The court in Hotz v University of Cape Town ([2017] ZACC 10, par 32) specifically mentions valuable South African artworks that were ruined; in Rhodes University v Student Representative Council of Rhodes University ([2016] ZAECGHC 141), the court also addressed gender- and race-based violence during student protest action in addition to kidnapping, assault and intimidation; also see Durban University of Technology v Zulu [2016] ZAKZPHC 58. Violent student strikes were reported in the mass media as well; see News24 "Unisa Gets Interdict Against Protesters" (2016-01-15); Singh "Police Disperse Protesting Durban Unisa Students with Rubber Bullets, Tear Gas" (2020-01 -27) News24; Sobuwa Live "NWU Campus Closed as Violent Protests Hit Varsities" (2020-01-29) Sowetan. For an academic perspective, see Mutekwe "Unmasking the Ramifications of the Fees-Must-Fall-Conundrum in Higher Education Institutions in South Africa: A Critical Perspective" 2017 35(2) Perspectives in Education 142.

50 Otto "Moord op Oud-Recce: 'Waar is die Wye Verontwaardiging?'" (2022-02-20) Netwerk24; Sibiya "Unisa Arson Attack as Union Protests Turn Violent" (2022-05-20) Rekord.

51 Traugott and Dasher Regularity in Semantic Change 12. Another way of looking at it is to view a word as having a subset of meanings; each meaning is disambiguated according to the relevant context. In the sentence "John left for the bar at about 10h00", the context should aid the interpreter in deciding whether "bar" refers to a pub or a law chamber. See Grondelaers, Speelman and Geeraerts "Lexical Variation and Change" in Geeraerts and Cuyckens (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics (2012) 992.

52 Cognates of the German word "bank" are present in Afrikaans: "skoolbank", "skaafbank".

53 Geeraerts "Sense Individuation" in Riemer (ed) The Routledge Handbook of Semantics. Routledge (2016) 238-239. This is one way to view the distinction.

54 Geeraerts Theories of Lexical Semantics (2010) 231.

55 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 8-11.

56 Grondelaers et al in Geeraerts and Cuyckens (eds) Cognitive Linguistics 990.

57 Grondelaers et al in Geeraerts and Cuyckens (eds) Cognitive Linguistics 989-990.

58 Bybee "Usage-Based Theory and Grammaticalization" in Hene and Narrog (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization (2012) 72.

59 Bybee "Diachronic Linguistics" in Geeraerts and Cuyckens (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics (2012) 75.

60 Geeraerts Theories of Lexical Semantics 26-27.

61 Geeraerts Theories of Lexical Semantics 27.

62 The author is collecting survey data to determine to what extent respondents associate the meanings of "strike", "riot" and "public disturbance" with one another. So far, 88 per cent of respondents (N=60) view the meaning of "strike" and "riot" as very similar or the same, and 85 per cent see "strike" and "public disturbance" as having mostly the same meaning. Seventy-eight per cent of respondents said South African labour strikes are mostly violent. Though the data set is still very small and not representative, it already points to perceptions that influence people's understanding and use of the word "strike", implying that an occasional sense does exist. (Ethics ref.: 90163184_CREC_CHS_2021)

63 Oxford English Dictionary "Strike n.1" (2022) https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/191631?rskey=gKyNbU&result=1&isAdvanced=false&print (accessed 2022-06-15).

64 A study on ordinary meaning found that "strike" usually indicates a non-violent event. Carney "A Legal Fallacy? Testing the Ordinariness of 'Ordinary Meaning'" 2020 137(2) South African Law Journal 269 291-292. See also the definition of "strike" in s 213 of the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995 for comparison.

65 Oxford Historical Thesaurus "strike" (2022) https://0-www-oed-com.oasis.unisa.ac.za/browsethesaurus?page=3&pageSize=100&scope=ENTRY&searchType=words&thesaurusTerm=strike&type=thesaurussearch (accessed 2022-06-15); Oxford Historical Thesaurus "riot" (2022) https://0-www-oed-com.oasis.unisa.ac.za/browsethesaurus?thesaurusTerm=riot&searchType=words&type=thesaurussearch (accessed 2022-06-15; Oxford Historical Thesaurus "disturbance" (2022) https://0-www-oed-com.oasis.unisa.ac.za/browsethesaurus?thesaurusTerm=disturbance&searchType=words&type=thesaurussearch (accessed 2022-06-15). Most thesauri are organised according to a conceptual hypernymic taxonomy. This means that entries are sorted according to concept and then classified in terms of a hierarchical taxonomy of inclusion. The general item includes the more specific items, as it moves from broadest to narrowest classification. Each entry in Table 1 starts with their entry number, followed by the hypernymic structure within the larger conceptual structure.

66 SASRIA's current policy wording (Annexure 4A: F4; 12-13) describes "public disorder" as a riot or "civil commotion" and describes "riot" as "a tumultuous disturbance of public peace", which confirms their similarity.

67 Thornton Legislative Drafting 2-3.

68 Thornton Legislative Drafting 3-4.

69 Natal Joint Municipal Pension Fund v Endumeni Municipality [2012] ZASCA 13 par 18.

70 SASRIA v Slabbert Burger Transport supra par 10.

71 By "selected undefined words", the author is referring to lexical words specifically (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) that contribute conceptually to the purpose and function of a statute or contract. For instance, few contracts that include clauses about resignation from employment include an interpretation clause stipulating when exactly the resignation period starts. We saw that SASRIA's initial policy coupon indemnified clients against damage caused by a strike, but they did not define the word "strike". The National Nuclear Regulator Act 47 of 1999 elaborates on who an inspector is and what the inspector should be doing, but the Act does not explain what an inspector is. The reader of the Act must infer the concept from the various references to "inspector". Many words are conceptually important to the purpose and functioning of legal texts, but the legislator/drafter mostly relies on their ordinary meaning instead of stipulating them.

72 Jackson Lexicography. An Introduction (2002) 27-28; see, in general, Gouws and Prinsloo Principles and Practice of South African Lexicography (2005); and Atkins and Rundell The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography (2008) 45-47.

73 Natal Joint Municipal Pension Fund v Endumeni Municipality supra par 18.

74 This does not relate to implied terms in contracts that recall trade usage and which have conventionalised and need no further stipulation. See Fouché "The Content of Contracts" in Fouché (ed) Legal Principles of Contract and Commercial Law (2021) 106; Singh Business and Contract Law (2010) 26-33.

75 Burger A Guide to Legislative Drafting 3.

76 66 of 1995.

77 Roznai "'A Bird is Known by its Feathers' - On the Importance and Complexities of Definitions in Legislation" 2014 2(2) The Theory and Practice of Legislation 145 147.

78 Obviously, the author is not insinuating that legal texts are written by a sole drafter who controls the whole drafting process. There is a lot of input from various sources, ranging from committees to public or private participation. However, drafters make their own contributions and affect the discourse surrounding the legal text through their drafting.

79 Price "Wagging, Not Barking: Statutory Definitions" 2013 60(4) Cleveland State Law Review 999 1004.