Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Obiter

On-line version ISSN 2709-555X

Print version ISSN 1682-5853

Obiter vol.42 n.3 Port Elizabeth 2021

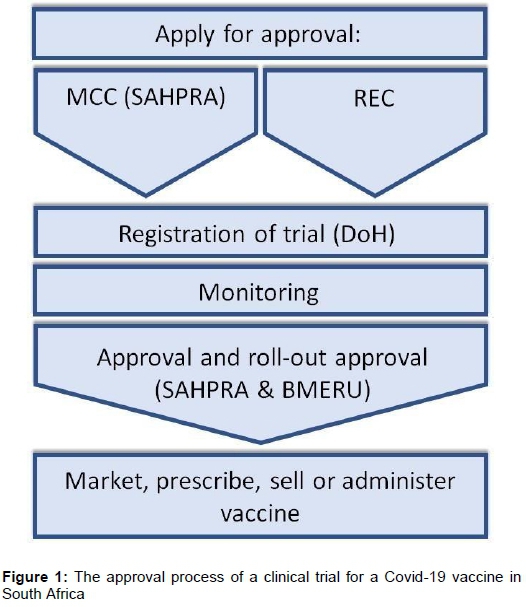

4 Approval by ethics committees

All clinical trials conducted in South Africa, including multinational trials, must apply for and receive ethical approval. Ethical approval must be granted by an accredited research ethics committee (REC) based in South Africa. RECs are responsible for ensuring that ethical norms and standards are met, but also for the safeguarding of the rights of the human participants and ensuring that a clinical trial is scientifically relevant in South Africa.

As mentioned above, the NHA in section 72 provides for the establishment of a National Health Research Ethics Council (NHREC), which must:

"(a) determine guidelines for the functioning of health research ethics committees;

(b) register and audit these health research ethics committees;

(c) set norms and standards for conducting research on humans..., including ... for conducting clinical trials;

(d) adjudicate complaints about the functioning of health research ethics committees and hear any complaint by a researcher

(e) refer to the relevant statutory health professional council matters involving the violation or potential violation of ethical or professional rules

(f) institute ... disciplinary action as ... prescribed against any person found to be in violation of any norms and standards or guidelines ...; and

(g) advise the national department and provincial departments on any ethical issues concerning research." (s 72(6) of the NHA)

Section 69 of the NHA provides for the establishment of the National Health Research Committee. This committee must:

"(a) determine the health research to be carried out by public health authorities; (b) ensure that health research agendas and research resources focus on priority health problems; (c) develop and advise the Minister on the application and implementation of an integrated national strategy for health research; and (d) coordinate the research activities of public health authorities." (s 69(3) of the NHA)

Specific provision is also made for research on or experimentation with human participants in section 71 of the NHA. This section provides for a wide variety of matters, including the conditions for research involving human participants in general, research involving a minor for therapeutic purposes, and research involving a minor for non-therapeutic reasons. The provisions found in the NHA are also supplemented by various regulations made in terms of the Act. Section 11, which provides for health services for experimental or research purposes, may also be relevant.

Currently, RECs must pay additional attention to Covid-19 trials, which are categorised as involving innovative therapy and, owing to this classification, additional control and review measures are imposed on the trial (see in general, De Vries "Research on COVID-19 in South Africa: Guiding Principles for Informed Consent" 2020 110(7) SAMJ 635-639 https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i7.14863). Once ethical approval is granted, the clinical trial may be registered.

5 Registration of clinical trial

After MCC and ethical approval has been obtained, the person responsible for the trial, the sponsor or principal investigator, must apply to the Department of Health (DoH) to have the trial registered.

The DoH must record the trial on the South African National Clinical Trial Register and award the trial a number. Only once the trial has been registered with the DoH and awarded its unique number may the trial commence (South African National Clinical Trial Register and National Health Research Ethics Committee "South African National Clinical Trial Registry (SANCTR) and National Health Research Ethics Committee (NHREC)" (2020) http://www.crc.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/53/documents/Reg/CRC%20website_Regulatory%20Content_updated%2020171204_SANCTR_NHREC.pdf (accessed 2020-11-16)). At this stage, the monitoring plan also takes effect.

6 Monitoring plan

The sponsor or principal investigator must have in place a monitoring plan that stipulates the review and monitoring of the trial. Normally, such review is done on a six-monthly basis as clinical trials may last years. However, owing to the rapidly changing dynamics of Covid-19, SAHPRA currently allows for an expedited two-week abridged Covid-19 interim progress report form for clinical trials. This report deals specifically with safety and futility monitoring (South African Health Products Regulatory Authority "Clinical Trials" (2020) https://www.sahpra.org.za/clinical-trials/ (accessed 2020-11-16)).

The prescribed form must be completed two-weekly from the date of approval of the clinical trial and even if participant enrolment has not yet started. It does not, however, replace the required six-monthly progress report.

7 Approval granted and roll-out

After the trial delivers fruitful results - that is, the successful development of a vaccine - the vaccine must be registered with SAHPRA. Only then may it be marketed, sold, prescribed or administered in South Africa, regardless of any foreign approval thereof by another country. This means, for example, that even if the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine is fully approved abroad by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it will still have to be locally approved and registered by SAHPRA. Note that, should a foreign regulatory authority that is recognised by SAHPRA (such as the FDA) already have approved the vaccine, SAHPRA may allow for expedited approval and registration within South Africa.

The registration of a new biological medicine, which includes a vaccine, is undertaken by the Biological Medicines Evaluation and Research Unit (BMERU), a sub-unit of SAHPRA. BMERU is responsible for the evaluation of applications for the registration of biological medicines, the evaluation of applications for amendments to registered biological medicines, communicating with the pharmaceutical industry on matters of policy, the establishment of regulatory frameworks for the use of blood products and stem cells, and the establishment of pertinent regulatory frameworks for vaccines (South African Health Products Regulatory Authority "Biological Medicines Evaluation and Research Unit" (2020) https://www.sahpra.org.za/biological-products/ (accessed 2020-11-16)).

Once SAHPRA and BMERU have concluded their evaluation of the registration application, taking into account any expert committee recommendations and all required documentation, it will decide whether a new biological medicine meets all requirements for registration.

If so, the medicine will be registered and may then be made available in South Africa.

8 Conclusion

This note has explained the process to be followed in approving new medication for human use within South Africa. Although the South African framework for the approval of new medication, such as a Covid-19 vaccine is clear cut, the virus has proved to be wiley; and constant vaccine improvement and development will be necessary. This in turn will make the processes discussed above even more important so as to ensure safe and efficient, legal and ethically sound vaccine availability. In the meantime, we wait with masked and bated breath.

Larisse Prinsen

University of the Free State

^rND^1A01^nCI^sTshoose^rND^1A01^nCI^sTshoose^rND^1A01^nCI^sTshooseCASES

Dismissal arising from flouting Covid-19 health and safety protocols - Eskort Limited v Stuurman Mogotsi [2021] ZALCJHB 53

1 Introduction

The Labour Court judgment handed down by Tlhotlhalemaje J in Eskort Limited v Stuurman Mogotsi (JR1644/20) (2021) ZALCJHB 53 (Eskort Limited) on 28 March 2021 raised the topical issue of fairness regarding the dismissal of an employee for gross misconduct and negligence related to his failure to follow and/or observe COVID-19-related health and safety protocols put in place at the workplace (Eskort Limited supra par 1).

In light of the above, the objectives of this case note are twofold. First, it examines the parameters under which the employer can discipline an employee for flouting the COVID-19 safety protocols and regulations. Secondly, it also considers the extent to which the employer can take appropriate action against an employee who wilfully refuses to obey the lawful and reasonable instructions of the employer during COVID-19 times.

2 Overview of the factual matrix

The employee (Mr Mogotsi) was employed as Assistant Butchery Manager by Eskort Limited (employer). Subsequently, the employee was charged with the following offences (Eskort Limited supra par 4): first, gross misconduct related to his alleged failure to disclose to the employer that he had taken a COVID-19 test on 5 August 2020 and was awaiting his results; secondly, gross negligence, in that after receiving his COVID-19 test results (which were positive), he had failed to self-isolate, had continued working on 7, 9 and 10 August 2020, and had consequently placed the lives of his colleagues at risk. It was further alleged that in the period during which he had reported for duty, he failed to follow the health and safety protocols at the workplace, including adherence to social distancing (Eskort Limited supra par 4).

Subsequent to his dismissal, the employee referred an alleged unfair dismissal dispute to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA). At the arbitration hearing, the employer led the evidence of two witnesses to prove that the employee (Mr Mogotsi) was guilty of the allegations that had precipitated his dismissal. Similarly, the employee also

led evidence in his case (Eskort Limited supra par 6). The employer's first witness testified that it was common practice for the employee (Mr Mogotsi) to travel to and from work with a colleague, Mr Mchunu, in a private vehicle. On 1 July 2020, Mr Mchunu did not feel well and consulted with a medical practitioner, who booked him off sick from 1 to 3 July 2020 and extended his sick leave on 4 July 2020. Mr Mchunu was subsequently admitted to a hospital on 6 July 2020 and was informed on 20 July 2020 that he had tested positive for COVID-19 (Eskort Limited supra par 6.1). The witness further testified that at about the time that Mr Mchunu initially fell ill, his colleague Mr Mogotsi also started experiencing chest pains, headaches and coughs. According to the witness, the employee then consulted a traditional healer, who booked him off on 6 and 7 July 2020 and from 9 to 10 July 2020 (Eskort Limited supra par 6.2).

Upon being booked off by the traditional healer, the employee (Mr Mogotsi) was informed by management to stay at home. He nonetheless reported for duty after 10 July 2020. This was even after he became aware of Mr Mchunu's positive results (Eskort Limited supra par 6.3). The employee took a COVID-19 test on 5 August 2020 and was informed on 9 August 2020 via "SMS" that he had tested positive. The employer was unimpressed with the employee's conduct and raised a concern that despite having taken a COVID-19 test on 5 August 2020 and being informed of his positive results on 9 August 2020, he had reported for duty on 7, 9, and 10 August 2020, and came to the premises to hand in a copy of his results (Eskort Limited supra par 6.4).

In addition to the above, the second witness of the employer placed on record certain fundamental issues. First, the employer had COVID-19 policies, procedures, rules and protocols in place, and all employees had been constantly reminded of these through memoranda and various other means of communication posted at points of entry and also through emails (Eskort Limited supra par 6.5). Secondly, the employee was a member of the in-house "Coronavirus Site Committee", and was responsible, inter alia, for informing all employees [about their duties] if they suspected that they might have been exposed to COVID-19 (Eskort Limited supra par 6.6).

Furthermore, when the employer conducted its own investigations after the employee's test results were made known, it was discovered that on 10 August 2020, a day after he had received his results, he was observed in video footage at the workplace walking in the workshop without a mask, and hugging a fellow employee (Ms Milly Kwaieng) (Eskort Limited supra par 6.7). Upon his test results being known, and after further investigations and contact tracing, a number of employees who had contact with him had to be sent home to self-isolate, including Kwaieng and others who had other comorbidities (Eskort Limited supra par 6.8).

Under cross-examination, the employee testified that he received the test results on 9 August 2020 but alleged that he did not know he needed to self-isolate. He conceded having hugged Kwaieng on 10 August 2020, and having walked on the shop floor without a mask. His excuse was that he was on a phone call at the time and that he needed to remove his mask to have a clearer conversation with his caller. His main contention was that, despite asking for direction after he had reported ill and informing management that he had been in contact with Mr Mchunu, nothing was done, as business had continued as usual when he reported for duty (Eskort Limited supra par 6.11).

3 The decision of the CCMA and the Labour Court

Given the above evidence and having regard to relevant provisions of the Labour Relations Act (66 of 1995), the CCMA Guidelines, the Code of Good Practice: Dismissal, and relevant cases, the CCMA commissioner held that the employer had failed to justify the sanction of dismissal in light of its own disciplinary code and procedure, which called for a final written warning in such cases; it had thus deviated from its own disciplinary code and procedure (Eskort Limited supra par 7.4). Consequently, this made the dismissal of the employee unfair.

Aggrieved by the decision of the CCMA commissioner, the employer lodged an application to review the commissioner's award on various grounds, including that he had failed properly to apply his mind to the evidence placed before him, and had made findings that were not those of a reasonable decision maker (Eskort Limited supra par 8). The Labour Court, per Tlhotlhalemaje J, held that the findings of the commissioner on the issue of the appropriateness of the sanction and the relief granted were entirely disconnected from the evidence placed before him, and consequently this made his award reviewable (Eskort Limited supra par 9).

Tlhotlhalemaje J also cautioned that the CCMA commissioner/s ought to be wary of refusing

"to determine disputes involving dismissals for ordinary misconduct, simply because the employee (in most times unrepresented and throwing everything in the mix), happened to have alleged that he/she was victimised, harassed, discriminated against, or any other allegation that would divest the CCMA of jurisdiction." (Eskort Limited supra 7 par 11)

In the Labour Court's view, where such allegations are made, a commissioner is duty bound to look at the real nature of the dispute, irrespective of how the parties label the cause of a dismissal, before deciding whether the CCMA has jurisdiction to determine the dispute. The Labour Court held further that the mere mention of "victimisation" or "discrimination" by an employee at arbitration proceedings is not a gateway to the Labour Court (Eskort Limited supra par 11).

The Labour Court held that an important consideration in this case is that the commissioner had decisively concluded that the employee's conduct was "extremely irresponsible" in the context of the pandemic, and that he was therefore "grossly negligent". According to the court, that conclusion on its own, given the facts of this case, ought to have been the end of the matter, and the dismissal ought to have been confirmed (Eskort Limited supra par 12).

In its conclusion, the Labour Court held that the CCMA commissioner had failed to take into account the totality of circumstances as stated in Sidumo v Rustenburg Platinum Mines Ltd (2008 (2) SA 24 (CC)) (Sidumo case). The Sidumo case reads, in the relevant part:

"In approaching the dismissal dispute impartially, a commissioner will take into account the totality of circumstances. He or she will necessarily take into account the importance of the rule that had been breached. The commissioner must of course consider the reason the employer imposed the sanction of dismissal, as he or she must take into account the basis of the employee's challenge to the dismissal. ... [O]ther factors will require consideration. For example, the harm caused by the employee's conduct, whether additional training and instruction may result in the employee not repeating the misconduct, the effect of dismissal on the employee and his/her long-service record. This is not an exhaustive list." (Sidumo case par 78)

To this end, the Labour Court held that the sanction of dismissal was appropriate. In the first place, the employee was aware that he had been in contact with Mr Mchunu, who had tested positive for COVID-19. On his own version, he had experienced known symptoms associated with COVID-19 as early as 6 July 2020. Be that as it may, the employee had recklessly endangered not only the lives of his colleagues and customers at the workplace, but also those of his close family members and other people he may have been in contact with (Eskort Limited supra par 17.1). Secondly, the employee's conduct came about in circumstances where, on the objective facts, and by virtue of being a member of the "Coronavirus Site Committee", he knew what he ought to do in an instance where he had been in contact with Mr Mchunu and where on his own version, he had experienced symptoms he ought to have recognised. He nonetheless continued to report for duty as if everything was normal, despite being told on no less than two occasions to stay at home during July 2020 (Eskort Limited supra par 17.2). Thirdly, the Labour Court held that the employee's conduct was not only irresponsible and reckless but was also inconsiderate and nonchalant in the extreme (Eskort Limited supra par 17.3). He had ignored all health and safety warnings, advice, protocols, policies and procedures put in place at the workplace related to COVID-19, of which he was aware of given his status not only as a manager but also part of the "Coronavirus Site Committee".

According to the Labour Court, the evidence presented before the CCMA commissioner showed that the employee was not only grossly negligent and reckless, but also dishonest. He had failed to disclose his health condition over a period of time, sought to conceal the date upon which he had received his COVID-19 test results, and completely disregarded all existing health and safety protocols put in place not only for his own safety but also for the safety of his co-employees and the applicant's customers (Eskort Limited 10 par 17.6).

Lastly, the Labour Court held that the egregious nature of the employee's conduct was such that "a trust and working relationship between him, the applicant, and his fellow employees, cannot by all accounts be sustainable" (Eskort Limited supra par 17.7). The Labour Court declared that the dismissal of the employee was procedurally and substantively fair. The court made an order setting aside the award of the CCMA commissioner, and substituting it with an order that the dismissal of the employee was substantively fair (Eskort Limited supra par 21).

4 Analysis of Eskort Limited v Stuurman Mogotsi

4 1 The employer's duty to ensure a safe working environment

The Labour Court judgment is welcomed as it compels employers to take the existing COVID-19 health and safety measures and protocols seriously. COVID-19 has taken dreadful control of the world and is described as an invisible enemy. It is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease was first identified in 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei, China, and has since spread globally, resulting in the 2019-2020 coronavirus pandemic (Musa, Sivaramakrishnan, Paget, and El-Mugamar "COVID-19: Defining an Invisible Enemy Within Healthcare and the Community" 2021 42(4) Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 495-497; Chauhan, Jaggi, Chauhan and Yallapu "COVID-19: Fighting the Invisible Enemy with MicroRNAs" 2021 19(2) Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 137-145).

COVID-19 typically spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets produced when people cough or sneeze. The WHO keeps a live count of the numbers of those who have perished. As of 6 May 2021, there had been 154 815 600 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 3 236 104 deaths as reported to the WHO (WHO "WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard" https://covid19.who.int (accessed 2021-04-07)).

The drive to curb the COVID-19 pandemic, and its global health and economic effects, is unprecedented (WHO "Impact of COVID-19 on People's Livelihoods, their Health and our Food Systems" (13 October 2020) https://www.who.int/news (accessed 2021-04-07)). South Africa has not been spared. As of 6 May 2021, South Africa's confirmed mortality cases owing to COVID-19 stood at 54 620 deaths (National Institute for Communicable Diseases (6 May 2021) https://www.nicd.ac.za (accessed 2021-05-07)). With the third/fourth wave approaching, the death toll was expected to rise dramatically as elsewhere in the world (Buthelezi "A Third of SA's Covid-19 Survivors May Be at Risk of Reinfection, Warns Discovery" (6 May 2021) https://www.news24.com/fin24/companies/health/a-third-of-sas-covid-survivors-may-be-at-risk-of-reinfection-warns-discovery-2021050; Businesstech "South Africa's Third Covid-19 Wave Could Hit Earlier Than Expected: Expert" (18 April 2021) https://businesstech.co.za/news (accessed 2021-05-07)).

Henceforth, employers have a duty to take reasonable care for the safety of their employees in all conditions of employment (Joubert v Buscor Proprietary Limited 2013/13116 (2016) ZAGPPHC 1024 (9 December 2016) par 16 and 26; see also Lewis and Sargeant Essentials of Employment Law 8ed (2004) 23; Denyer Employer's Common Law Duty to Take Reasonable Care for the Safety of His Worker's Industrial Law and its Application in the Factory (1973) 47-48). The duty to provide a safe workplace relates to the employer's responsibilities imposed by the common law to ensure that the workplace is reasonably safe. In contrast, the employer's duty to provide a safe work system relates to ensuring that the actual mode of conducting work is safe (SAR & H v Cruywagen 1938 CPD 219 229; Tshoose

"Employer's Duty to Provide a Safe Working Environment: A South African Perspective" 2011 6(3) Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology 165; Tshoose "Placing the Right to Occupational Health and Safety Within a Human Rights Framework: Trends and Challenges for South Africa" 2014 47(2) Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa 276-296). There is no specific legislation dealing with COVID-19; however, the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (as amended) is the overarching legislation regulating and dealing with issues arising from COVID-19 (Tshoose and Ndlovu "COVID-19 and Employment Law in South Africa: Comparative Perspectives on Selected Themes" 2021 33(1) SA Mercantile Law Journal 25-56).

Section 24(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 guarantees the right of everyone to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being. To give effect to the constitutional provision above, various overarching pieces of legislation were passed in South Africa to regulate employees' safety and compensation in the workplace. These are the Occupational Health and Safety Act (85 of 1993) (ÓHSA), Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (130 of 1993) (COIDA), Mines Health and Safety Act (29 of 1996) (MHSA), and the Occupational Diseases in Mines and Works Act (78 of 1973) (ODIMWA).

The overall objective of these pieces of legislation is to protect employees with regard to their safety in the workplace. However, viewed individually, they serve different purposes. OHSA and the MHSA deal with the health and safety of employees in the workplace. In contrast, COIDA and ODIMWA deal with the aftermath of injury or disease - for example, payment of compensation to injured employee/s. This approach is informed by the ILO conventions regarding employment injuries. They include the ILO's Minimum Standards Convention 102 of 1952 and its Employment Injury Benefits Recommendation 121 of 1964. The above pieces of legislation guarantee the right of everyone to a safe environment.

The Disaster Management Act Regulations set out other specific measures to be taken by employers - for example, social distancing, screening of employees, sanitising and disinfecting the workplace, monitoring and ensuring that employees wear their cloth masks. Similarly, employees are obliged to comply with measures introduced by their employer as required by the Regulations (Directive by the Minister of Employment and Labour in terms of Regulation 10(8) of the regulations issued by the Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs in terms of s 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002).

Section 8(1) of OHSA places an express obligation on the employer to maintain a working environment that is safe and healthy. On the issue of a healthy working environment, the employer must ensure that the workplace is free from any risk to the health of its employees as far as is reasonably practicable. There is a clear obligation on the employer to manage the risk of contamination in the workplace, specifically considering COVID-19 (Olivier "The Coronavirus: Implications for Employers in South Africa" (6 March 2020) https://www.webberwentzel.com/News/Pages/the-coronavirus-implications-for-employers-in-south-africa.aspx (accessed 2020-04-14)). Practically, the employer can ensure a healthy working environment by keeping the workplace clean and hygienic, promoting regular hand-washing, promoting vaccination of employees, proper ventilation, and keeping employees informed on developments related to COVID-19 (WHO "WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices" (2010) https://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplace_framework.pdf (accessed 2020-04-14) 15-16).

4 2 The employee's duty to disclose his/her COVID-19 status under POPI Act and other relevant laws

Since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, information relating to infected employees has become a vital resource in managing the spread of the disease, and in protecting other employees and members of the community. Consequently, it is important also to unpack briefly how this confidential personal information is handled and disclosed in terms of the Protection of Personal Information Act, and its Regulations (Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013 (POPI Act)).

The purpose of the POPI Act is to regulate the processing (including collection, use, transfer, matching and storage) of personal information by public and private bodies. The POPI Act gives effect to the constitutional right to privacy. In so doing, it balances the right to privacy with other rights and interests, including the free flow of information within South Africa and across its borders. The POPI Act adopts a principle-based approach to the processing of personal information. It sets out eight conditions for the lawful processing of personal information: accountability, processing limitation, purpose specification, further processing limitation, information quality, openness, security safeguards, and data subject participation. These principles apply equally to all sectors that process personal information. The Act prescribes certain conditions for the lawful processing of personal information. Personal information relating to a person's health is considered to be special personal information, owing to its sensitive nature, and a higher degree of protection is afforded to such information (De Bruyn "The POPI Act: Impact on South Africa" 2014 13(6) International Business & Economics Research Journal 1315-1334; for further reading on the POPI Act, see Burns and Burger-Smidt A Commentary on the Protection of Personal Information Act (2018) ch1 -18).

Similarly, section 14(1) of the National Health Act provides that all patients have a right to confidentiality (National Health Act 63 of 2001 (NHA)). This is consistent with the right to privacy provided for in section 9 of the Constitution. Notwithstanding the above, section 14(2)(a)-(c) of the NHA makes an important exception to the general rules of absolute confidentiality set out in the POPI Act and the Health Professions Council of South Africa Guidelines (Health Professions Council of South Africa "Guidelines for Good Practice in the Health Care Professions" (2016) (HPCSA Guidelines) https://www.hpcsa.co.za/pdf (accessed 2021-05-06)).

Specifically, if the non-disclosure of a patient's medical information would pose a serious threat to public health, then the medical information must be disclosed. For the disclosure to be justified, the risk of harm to others must be serious enough to outweigh the patient's right to confidentiality and privacy (s 14(2)(a)-(c) of the NHA). Collecting important information about the spread of COVID-19, while also protecting the patient's identity, is in line with both the POPI Act, and the Constitution. In terms of the POPI Act, information must be de-identified as soon as it has been used for the purpose it was collected. The de-identified data can then be disclosed to the public to keep it informed of the spread of the disease (Schindlers Attorneys "Testing Positive for Covid-19: Public Health vs Privacy" (2020) https://www.schindlers.co.za/2020/testing-positive-for-covid...11257 (accessed 2021-05-06)).

The gist of the matter is that a patient's right to privacy and confidentiality is a priority However, since the COVID-19 pandemic has been declared a national state of disaster under section 27(1)-(3) of the Disaster Management Act (57 of 2002), the right to privacy must be weighed against the risk of harm to the public health. The POPI Act, HPCSA Guidelines, the NHA, and the Constitution are amenable to the conclusion that public health outweighs the protection of personal information and the right to confidentiality and privacy (Donaldson and Lohr Health Data in the Information Age: Use, Disclosure, and Privacy (1994) 136-179).

In summary, it is clear that an employee has a duty to disclose his/her COVID-19 status in the following cases: first, where the risk of harm to others outweighs the patient's right to confidentiality and privacy; and secondly, where such a disclosure will play a role in assisting the government to find effective solutions to deal with the health, economic, and social impacts of COVID-19.

The first and second points (raised above) affect the duty of the employee to disclose his/her COVID-19 status. Section 36 of the Constitution provides that there is no absolute standard that can be laid down for determining the reasonableness and necessity of infringing fundamental rights in a democratic society; these circumstances have to be balanced on a case-by-case basis (S v Makwanyane 1995 (3) SA 391 par 104). In this balancing process, the relevant considerations will include the nature of the right that is limited, and its importance to an open and democratic society based on freedom and equality; the purpose for which the right is limited and the importance of that purpose to such a society; and the extent of the limitation, its efficacy, and (particularly where the limitation has to be necessary) whether the desired ends could reasonably be achieved through other means less damaging to the right in question (S v Makwanyane supra par 104).

4 3 Dismissal arising from flouting COVID-19 regulations

Generally, an employer cannot discipline an employee for what is done in the employee's private space and spare time (Van Niekerk, Christianson, McGregor,and Van Eck Law@Work 4ed (2017) 301) unless it can be shown that the conduct of the employee amounts to criminal misconduct that in some or other respect affects the business of the employer, or could be likely to affect other employees' rights to a safe working environment (Edcon Limited v Cantamesa (2020) 41 ILJ 195 (LC); Moloto and Gazelle Plastics Management (2013) 34 ILJ 2999 (BCA); Khutshwa v SSAB Hardox (2006) 27 ILJ 1067; Ibbett & Britten (SA) (Pty) Ltd v Marks (2005) 26 ILJ 940 (LC); see also Van Niekerk et al Law@Work 302).

That said, there are circumstances in which an employer can dismiss an employee for acts of misconduct committed outside the scope of his/her employment - for example, for flouting the COVID-19 rules and regulations. The case in point involves cases where the employee commits misconduct. Generally, misconduct is the most common ground upon which employers seek to justify dismissal of an employee. In these instances, the employee is disciplined for conduct that contravenes a disciplinary rule of the employer (Collier, Fergus, Cohen, Du Plessis, Godfrey, Le Roux and Singlee Labour Law in South Africa: Context and Principles (2018) 207-209). In order to show that the employee has been fairly dismissed, the employer must show that it has acted both substantively and procedurally fairly (on the procedural fairness requirement, see Schwartz v Sasol Polymers (2017) 38 ILJ 915 (LAC) par 16; Opperman v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (2017) 38 ILJ 242 (LC) par 18; Hillside Aluminium (Pty) Ltd v Mathuse (2016) 37 ILJ 2082 (LC) par 71 -72; SA Revenue Service v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (2014) 35 ILJ 656 (LAC) 34; Rennies Distribution Services (Pty) Ltd v Bierman NO (2008) 29 ILJ 3021 (LC) par 24; on substantive fairness, see Mathabathe v Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality (2017) 38 ILJ 391 (LC) par 22; Avril Elizabeth Home for the Mentally Handicapped v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (2006) 27 ILJ 1644 (LC) 1654).

In respect of substantive fairness, the employer ought to have a good reason for the dismissal, while on the procedural fairness front, the employer ought to follow the proper procedure before an employee can be dismissed or disciplined (McGregor, Dekker, Budeli-Nemakonde, Germishuys, Manamela and Tshoose Labour Law Rules (2021) 125-129). If the employer is unable to prove the misconduct on a balance of probabilities, then the employer may not dismiss the employee.

Furthermore, it should always be borne in mind that an employee should only be dismissed for gross or repeated serious misconduct. Likewise, the merits of a Policy of Progressive Discipline and the Code of Good Practice, which appears in Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act (66 of 1995), ought to be considered. Thus, the gravity of the offence concerned and its impact on the employment relationship needs to be assessed in light of the circumstances of each case (Tshoose and Letseku "The Breakdown of the Trust Relationship Between Employer and Employee as a Ground of Dismissal: Interpreting LAC Decision in Autozone" 2020 1 SA Mercantile Law Journal 156-174). The seriousness of the misconduct will determine whether or not dismissal is warranted (Tshoose and Letseku 2020 SA Mercantile Law Journal 156-174).

In a case where the employee has flouted COVID-19 regulations - for example, where an employee openly attends mass/social gatherings and posts about it (e.g., posting the name of his/her employer) on their social media, and continues to attend the office as normal. This has the potential not only to endanger the health and safety of employees who share a workspace, but also to damage the employer's reputation. The employer would be justified in taking disciplinary action against such employee/s in this situation. In fact, the Labour Court judgment in Eskort Limited has shown that in such circumstances the dismissal of an employee is warranted.

Manamela asserts that an employer may dismiss an employee who fails to comply and obey lawful and reasonable instructions in the form of an operational requirement dismissal (Manamela "Failure to Obey Employer's Lawful and Reasonable Instruction: Operational Perspective in the Case of a Dismissal: Motor Industry Staff Association and Another v Silverton Spraypainters and Panelbeaters (Pty) Ltd" 2013 25(3) SA Mercantile Law Journal 418-435). Proving an employee has not complied with the COVID-19 regulations in these kinds of situations is not always easy but, where there are suspicions and concrete evidence, formal disciplinary sanctions could be applied where an employer, following fair investigation, has a reasonable belief that misconduct warranting action has been committed.

With regard to the issue of misconduct committed outside working hours, the jurisprudence of the South African courts and academic discourse has shown that a link between an employee's off-duty misconduct and the employer's business can exist (Edcon Limited v Cantamesa 2020 41 ILJ 195 (LC); Moloto and Gazelle Plastics Management (2013) 34 ILJ 2999 (BCA); NEHAWU obo Barness v Department of Foreign Affairs (2001) 6 BALR 539 (P); Khutshwa v SSAB Hardox 2006 27 ILJ 1067; cf Tshoose "The

Employers' Vicarious Liability in Deviation Cases: Some Thoughts From the judgment of Stallion Security v Van Staden 2019 40 ILJ 2695 (SCA)" 2020 34(1) Speculum Juris Journal 42-50). Courts have found that such a link exists where the employee's conduct had a detrimental or intolerable effect on the efficiency, profitability, or continuity of the business of the employer (NEHAWU obo Barness v Department of Foreign Affairs supra). In the absence of the aforementioned link, the employer cannot discipline the employee as it is then regarded as non-work-related conduct. As discussed above, the employer will have to prove that the misconduct affected the business negatively, or that the business lost or could lose clients or even that it could bring the company name into disrepute. In short, the employer will have to prove it has a legitimate interest in the matter (Le Roux "Off Duty Misconduct: When Can It Give Rise to Disciplinary Action?" 2011 20(10) Contemporary Labour Law 91 -97).

In light of the above discussion, it becomes clear that an employer can discipline an employee for flouting the COVID-19 regulations. In fact, the Labour Court in Eskort Limited v Stuurman Mogotsi (supra) has conspicuously outlined the circumstances under which the employer can take appropriate action against an employee who wilfully refuses to obey the lawful and reasonable instructions of the employer in the time of COVID-19.

5 Concluding remarks

COVID-19 is a terrifying pandemic that may endanger humanity if it spreads and cannot be controlled. Following the Labour Court judgment in Eskort Limited, it is now clear that should an employer issue a lawful and reasonable instruction to its employees, even in the midst of a pandemic, the employee is obliged to adhere to it and could face dismissal for failure to comply (Botha v TVR Distribution (2020) 12 BALR 1282 (CCMA)). The Labour Court judgment advances the need for more to be done at both the workplace and in our communities in ensuring that employers, employees, and communities be sensitised to the realities of COVID-19, and to further reinforce the obligations of employers and employees in the face of, or in the event of exposure to, this pandemic (Eskort Limited supra par 2).To conclude, employers are encouraged to update their policies to include specific guidelines on the conduct of employees during COVID-19 and to make it clear to employees that what they do during these times of the pandemic could "cost them their job".

CI Tshoose

University of Limpopo

^rND^1A01^nAndré^sMukheibir^rND^1A01^nAndré^sMukheibir^rND^1A01^nAndré^sMukheibirCASES

Barking up the wrong tree - the actio de pauperie revisited - Van Meyeren v Cloete (636/2019) [2020] ZASCA 100 (11 September 2020)

1 Introduction

It is trite that the South African law of delict follows a generalising approach (Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa (2017) 19-20; Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict (2020) 4-5). This entails that liability will only ensue when all the elements of delict are present. South African law does not recognise individual "delicts" (Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa 19; Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 4). The generalising approach followed in South African law is qualified in that there are three main delictual actions, namely the actio legis Aquiliae for patrimonial loss; the actio inuriarum for loss arising from intentional infringements of personality rights; and the Germanic action for pain and suffering, in terms of which a plaintiff can claim compensation for negligent infringements of the physical-mental integrity (Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa 19; Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 5). This approach is further qualified in that numerous actions dating back to Roman law still exist in our law today. Included in this mix are the actions for harm caused by animals, such as the actio de pauperie, the actio de pastu, and the actio de feris, each with its own requirements (Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 435-440; Scott "Die Actio de Pauperie Oorleef 'n Woeste Aanslag Loriza Brahman v Dippenaar 2002 (2) SA 477 (HHA)" 2003 TSAR).

There have been questions as to whether these actions, in particular the actio de pauperie, still form part of South African law. In Loriza Brahman v Dippenaar (2002 (2) SA 477 (SCA) 487) the defendant claimed that the actio was no longer part of the South African law (par 14). The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) per Olivier JA held that the actio de pauperie had been part of South African law for more than 24 centuries and not fallen into disuse (par 15). Olivier JA held that the fact that the action is based on strict liability (one of the arguments raised against it) is no reason to ban it from South African law as strict liability was increasing and in suitable instances fulfils a useful function (par 15).

The SCA, again, recently confirmed the continued existence of the action in South African law in the case of Van Meyeren v Cloete ((636/2019) [2020] ZASCA 100 (11 September 2020) 40). In this case, the SCA had to decide whether to extend the defences against liability in terms of the actio de pauperie to the negligence of a third party that was not in control of the animal. The defendant held that the court should develop the common law in this regard. Considering both case law and the requirements for the development of the common law, the SCA held that such an extension could not be justified.

2 Facts

Mr Gerhard Cloete, a gardener and refuse collector, was on his way to the shop, pulling the trolley in which he collects refuse. While walking past the Van Meyeren house, minding his own business, he heard dogs behind him. Three dogs subsequently attacked him from behind. The dogs belonged to Van Meyeren, who was the appellant in the case. The dogs savaged Mr Cloete, and this resulted in his left arm being amputated. Mr Cloete claimed damages in terms of the actio de pauperie and in the alternative, on the basis of negligence (presumably in terms of the actio legis Aquiliae). Mr Cloete's presence in the place where he was attacked was lawful and he had done nothing to provoke the dogs. The dogs also attacked Mr van Schalkwyk, a passer-by who had come to Mr Cloete's assistance. Nobody was at home at the time of the incident.

By all accounts, the dogs, mixed breed with pit-bull features, had never attacked anyone and slept in the house. They had the run of the house and the garden, which was fenced and sealed off from the street by means of a padlocked gate. Whether the gate was in fact padlocked on the day of the incident is uncertain. Mr and Mrs van Meyeren testified that the gate was at all times locked with two padlocks. They alleged that the gate had been opened by an intruder. Photographs taken on the day of the incident showed no padlocks. A photograph taken some time later showed the gate with two heavily rusted padlocks (see discussion in 3 1 and 3 2 below).

3 Judgment

3 1 Court a quo

The plaintiff claimed damages in terms of the actio de pauperie in the court a quo and succeeded (see Scott "Conduct of a Third Party as a Defence against a Claim Based on the Actio de Pauperie Rejected - Cloete v Van Meyeren [2019] 1 All SA 662 (ECP); 2019 2 SA 490 (ECP)" 2019 82(2) THRHR for a case discussion of the decision of the court a quo). Initially, the defendant denied that his dogs had been responsible for the attack and if they had been, it was because an intruder had attempted to break into the front door and had broken open the gates to the garden where the dogs were kept. He denied liability and negligence.

The defendant eventually conceded that the dogs were his and that they had acted contra naturam sui generis. The court had to decide two questions, namely whether the fact that the gate had allegedly been opened and left open by an intruder could constitute an exception to liability in terms of the actio and if so, if the plaintiff could establish liability in terms of the actio legis Aquiliae? (Cloete v Van Meyeren 2019 2 SA 490 (ECP) 6). The defendant bore the onus of proving that the gate was left open by an intruder. While the Court regarded the defendant as an unsatisfactory witness, it nevertheless accepted that the gates had been locked and later broken open by an intruder (Cloete v Van Meyeren supra par 16). As there was no negligence, the court held that liability in terms of the actio legis Aquiliae had to fail.

Dealing with the actio de pauperie, the Court commenced by looking at the history of the action (par 18), referring to the historical overview in Lever v Purdy (1993 (3) SA 17 (AD) 21C-25F as cited in Cloete par 20). With reference to the Lever case (supra) the court a quo found that there were two categories of conduct of third parties that would serve as a defence against the actio de pauperie, namely (a) where the third party through positive conduct provoked the animal; and (b) where the third party who was in control of the animal, culpably lost control.

In the present case, the defendant relied on the second defence but did not succeed. In Lever v Purdy (supra), the defendant argued that the negligence of the intruder who left the gates open but was not in control of the animals would be sufficient to bring the so-called "wider" exception as a complete defence against the actio de pauperie. Lowe J argued that while the existence of the "wider exception" finds some support in case law, there is no support for such an extension in Roman law or Roman-Dutch law. Looking at previous cases such as Lever v Purdy (supra) and Loriza Brahman v Dippenaar (supra), Lowe J stated that he could "find no convincing support either in principle or flowing from the rules as to pauperian liability justifying the extension of a pauperian defence or exception as contended by the defence" (par 40). The plaintiff's claim in terms of the actio de pauperie was, therefore, successful (par 42).

According to Scott (2019 THRHR 331), the outcome of this judgment had to be welcomed, as it was in accordance with the approach that the liability of an owner of a domestic animal was based on the risk principle. This is because the person who keeps such an animal creates potential danger, and this justifies holding the owner liable, even in the absence of fault (see discussion below in 4 3).

3 2 Supreme Court of Appeal

The defendant appealed to the SCA, where the court per Wallis JA dismissed the appeal (par 43).

The SCA dealt with three issues, namely:

(a) The treatment of the factual evidence in the court a quo;

(b) Whether the actio de pauperie was still part of South African law and if so;

(c) Whether the third-party defence should be extended to a situation where the harm would not have occurred, but for the negligent conduct of the third party in circumstances where the third party had no control over the animal.

3 2 1 The treatment of the factual evidence in the court a quo

Wallis JA criticised the court a quo's handling of the "unsatisfactory and speculative evidence" of the defendant (par 13). The onus of proving that the evidence was correct rested on Van Meyeren. The court was not obliged to accept an improbable explanation merely because there was no other explanation or that the alternative seemed even less probable to the judge (par 13). Wallis JA identified two possibilities, namely (a) the gates were not sufficiently secured to keep the dogs inside, and (b) there was an intruder (the explanation proffered by the Van Meyerens). The issue, in this case, was whether the explanation of the Van Meyerens (that the dogs escaped) was, on a balance of probabilities, the only conclusion that could be reached. Mr van Meyeren bore the onus of proof and did not discharge it. His defence should, therefore, have failed (par 13).

3 2 2 Is the actio de pauperie still part of South African law?

Wallis JA summarised the recent history of the action, starting with O'Callaghan v Chaplin (1927 AD 310), including a discussion of Loriza Brahman v Dippenaar (supra par 15-10). From the case law, it is clear that the actio de pauperie was and is a part of our law (see discussion below).

Wallis JA described the contra naturam requirement as reflecting an element of anthropomorphism (see discussion below) in that "for the owner to be liable, there must be something equivalent to culpa in the conduct of the animal" (par 19 referring to SAR and H v Edwards 1930 AD 3 9-10). If the animal has not acted contra naturam the owner will not be held liable. The onus, in this case, is on the owner to prove that the animal did not act contra naturam (par 19).

3 2 3 Should the third-party defence be extended to a situation where the harm would not have occurred, but for the negligent conduct of the third party in circumstances where the third party had no control over the animal?

Mr van Meyeren argued that the defence recognised in Lever v Purdy (supra) should be extended to exempt the owner from liability for harm caused by the animal in a situation where the harm occurred as a result of the negligent conduct of a third party, irrespective of whether the third party had control over the animal or not.

Wallis JA (par 23) referred to Lever v Purdy (supra), citing the two instances identified in that case where the conduct of a third would constitute a defence against the actio de pauperie, namely (a) striking or provoking the animal in some way; and (b) where the third party was in control of the animal and failed to prevent the animal from causing harm to the victim. These cases were identified by Joubert JA upon a reading of the common-law sources. The minority decision of Kumleben JA referred, in passing, to a wider exception, but, according to Wallis JA, nothing in Lever v Purdy (supra) supported the wider third-party defence.

Wallis JA, stated that "these rather cryptic references in and to the old writers on the Roman-Dutch law" do not serve as a clear authority to indicate the existence of a wider defence (par 31).

Van Meyeren argued that the law in this regard should be developed to provide for the wider defence. Wallis JA (par 32, referring to Mighty Solutions (Pty) Ltd t/a Orlando Service Station v Engen Petroleum Ltd 2016 (1) SA 621 (CC) 38) summarised the court's power to develop the common law, stating that the power is vested in the High Courts, Supreme Court of Appeal, and the Constitutional Court, by virtue of section 173 of the Constitution. This power has to be exercised "in accordance with the interests of justice" (par 32). The courts are enjoined by section 39(2) to "promote the spirit, purport and objects of the Bill of Rights". When considering whether to develop the common law, a court has to do the following (par 32): (a) determine what the common law position is; (b) consider the underlying reasons for this position; (c) ask whether the rule offends the spirit, purport and object of the Bill of Rights; and (d) consider in which way the common law could be amended, and take into consideration the effects of the change on the particular area of the law.

Wallis J, having had already set out the common-law position (as per (a) above), proceeded to look at (b), namely the underlying reason for the actio, which, according to him was that between the owner of the dog and victim, it is "appropriate" for the owner to bear that harm, instead of the victim (par 33). Insofar as (c) is concerned, the appellant did not rely on any specific provision of the Bill of Rights; he also did not (correctly so, according to Wallis JA) allege that the limited exception offended the spirit, purport, and objects of the Bill of Rights. This, according to Wallis JA, was correct, because the actio in fact serves to protect the right to bodily integrity in section 12(2); the right to dignity in section 10; and the right to life in section 11 (par 34). The court held that the actio exists to protect these rights and it is right to rather develop the actio in ways that can protect these rights (par 34).

Counsel for the appellant submitted that given the levels of crime in South Africa it was reasonable for people to want to protect themselves and not everyone could afford sophisticated security systems (par 35). Wallis JA held that while this is true, deterrence and restraint do not mean that the intruder has to be killed or maimed (par 35).In this particular case, furthermore, the dogs harmed an innocent bystander, not an intruder; and this took place, not on the premises of the owner, but in the street (after the dogs escaped). The right to keep a dog for the protection of the home is extensive but this right becomes irrelevant where the dog harms someone outside the home (par 36). The appellant did not deny that the requirements for the actio de pauperie were met but claimed that fault was absent. However, as stated by Wallis JA, fault had never been a requirement for the actio de pauperie and a defence of absence of fault will not preclude pauperian liability.

Furthermore, Wallis JA held that where the conduct of either the victim or third parties exonerate the owner from liability in terms of the actio de pauperie, it is because the conduct directly caused the incident in which the victim suffered harm this refers to circumstances where the owner is unable to prevent the harm from taking place.

Wallis JA referred again to Lever v Purdy (supra), this time to the minority decision of Kumleben JA, in particular to the following points raised by Kumleben:

(i) The South African law of delict is based on the fault principle - in this regard, Wallis JA pointed out that vicarious liability is strict, as well as liability in terms of certain statutes (par 40);

(ii) Kumleben JA held that if one had to weigh up the interests of the owner, who was not at fault, and that of the victim, who had suffered damage as a result of the conduct of the animal, "considerations of fairness and justice favoured the owner". According to Wallis JA, this interpretation is incorrect, given the constitutional values that he mentioned earlier. Also the dog's owner can obtain insurance cover in terms of a household insurance policy (par 42).

In the final instance Wallis JA recognised that many South Africans choose to have dogs, both for companionship and for protection. This gives rise to responsibilities. When someone chooses to have an animal and someone is harmed by the animal while being innocent of fault, the interests of justice require that the owner should be held liable for the harm that ensued (par 42).

4 Discussion

4 1 The actio de pauperie of yesteryear

The actio de pauperie originated in the Twelve Tables (O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 313; Kaser Roman Private Law (1984) 252; Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 435; Polojac "Actio de Pauperie Anthropomorphism and Rationalism" 2012 8(2) Fundamina 119; Zimmermann The Law of Obligations (1990) 1096) and is said to have been around as early as 450BC (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1097).

The action was a noxal action, meaning that the owner of an animal that caused harm either had to pay compensation or to give the animal to the injured party (Kaser Roman Private Law 252; Polojac 2012 Fundamina 137; Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1099; Lever v Purdy supra 21A; O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 314). Zimmermann writes that animals were regarded to have committed the delict, and "[t]he victim of the injury was thus allowed to wreak his vengeance upon the body of the animal - in the very same way as if the wrongdoer had been a human being" (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1099; see also Polojac 2012 Fundamina 137). If, however, the animal was owned by someone, the victim could not just kill the animal because by so doing he would be infringing the rights of the owner (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1099). He could, however, request the surrender of the animal, which was known as noxae deditio (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1099; see also O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 315; Lever v Purdy supra 21A).

Eventually, a claim for damages was regarded as a more appropriate remedy as the idea of private vengeance underpinning the law of delict fell away (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1100). According to Zimmermann, in classical and post-classical Roman law the victim could choose between claiming damages from the owner or the surrender of the animal (The Law of Obligations 1100; see also Polojac 2012 Fundamina 137).

Another rule - noxa caput sequitur - provided that the owner at the time of litis contestatio was liable for damages, rather than the owner at the time the harm was caused (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1100; see also O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 314; Lever v Purdy supra 21A). Moreover, if the animal died before litis contestatio, the right to institute the action fell away (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1100).

According to the Twelve Tables, the animal had to be a quadrupes, specifically a domestic animal (Polojac 2012 Fundamina 123, Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1101; O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 314). Although the word "quadrupes" had both a wide meaning (which included wild animals) and a narrow meaning (which was limited to domestic animals) the Twelve Tables used the narrow meaning (Polojac 2012 Fundamina 123). According to Polojac, dogs were initially not included within the ambit of the actio de pauperie; this only happened once the action was extended by the lex Pesolania de cane (Polojac 2012 Fundamina 124; see also O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 370). Polojac (2012 Fundamina 124) argues that in Classical Roman times the action was only applicable to domestic animals, even though there seem to be varying opinions about this.

Insofar as the contra naturam requirement is concerned, Polojac notes that the earliest sources included this requirement (Polojac 2012 Fundamina 134; see also Lever v Purdy supra 201; O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 313314). The animal had to show ferocity beyond its instinctive feritas, in other words, the ferocity had to be contra naturam (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1102). According to Zimmermann, this requirement was introduced by Roman lawyers to limit the liability of the owners (Zimmermann The Law of Obligations 1102). Polojac notes that because of the "obvious anthropomorphism in its approach to domestic animals" this requirement has been contentious in the literature (see Polojac 2012 Fundamina 134-137).

The actio de pauperie was received in the Netherlands (Lever v Purdy supra 20I-21A). There is uncertainty whether the noxal requirement fell into disuse (O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 318; see however Knobel "Remnants of Blameworthiness in the Actio de Pauperie" 2011 74 THRHR 633 634; Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 436; Lever v Purdy supra 21A). The actio came into South African law via Roman-Dutch law (Lever v Purdy supra 21A).

4 2 The actio de pauperie today

4 2 1 Requirements

To succeed with the actio de pauperie the following requirements have to be met (Knobel 2011 THRHR 637, Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa 458-462; Louw "Verwere by die Actio de Pauperie" 2001 De Jure 159, Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 436-437; Scott THRHR 321; Scott 2003 TSAR 194):

(a) The defendant must be the owner of the animal at the time the harm is inflicted. It is not enough that he has control over the animal; he must be the owner in terms of the property law definition of ownership (Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa 459).

(b) The animal must be a domestic animal; the following animals are examples of animals recognised by our law as being domesticated: dogs; cats; livestock; bees; horses; mules; and meerkats (Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 386; Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa 459).

(c) The animal must have acted contra naturam sui generis. This means that the animal must have acted contrary to what can be expected of a reasonable animal of that kind. The "flipside" of this requirement is that the animal must have caused the damage sponte feritate commota or from inward vice. In Loriza Brahman, the Court held that the yardstick is the conduct of the genus (in this case cattle) and not a specific species (Brahman cattle - see supra par 18). As mentioned above, in Van Meyeren Wallis JA speaks of "an element of anthropomorphism [that] underlies the pauperien action" (par 19):

"It attributes to domesticated animals the self-constraints that are generally associated with human beings and attaches strict liability to the owner on the basis of the animal having acted from inward vice".

The owner in this case bears the onus of proving that the animal did not act contra naturam sui generis (Van Meyeren supra par 19).

Neethling and Potgieter (Neethling-Potgieter-Visser Law of Delict (2015) 386) are of the opinion that the contra naturam requirement should be abolished for the following two reasons (Law of Delict 386; this is not mentioned in the latest edition of the book):

(i) The requirement points to a "personification or humanisation (see above, Wallis JA describing the test as anthropomorphic) of an animal by virtue of the "reasonable animal" test. They describe this line of reasoning as "artificial and thus undesirable".

(ii) The requirement lends itself to a wider variety of interpretations, thus leading to legal uncertainty and also resulting in any harmful conduct being classified as contra naturam, which would then on the basis of policy considerations be felt to found an action for damages.

Knobel is also of the opinion that the contra naturam requirement "in the vast majority of applications [...] can only function [...] as a fiction or catch-phrase denoting a standard of behaviour imposed by the law on domestic animals, and one containing unacceptable remnants of blameworthiness at that" (Knobel 2011 THRHR 639). According to Knobel, the best way to rid the actio de pauperie of notions of blameworthiness is to drop the contra natura requirement all together (2011 THRHR 641, 643).

Loubser and Midgley (The Law of Delict in South Africa 460) note that the courts apply the contra naturam test inconsistently, and that some cases follow a subjective approach by referring to the "innate wildness, viciousness or perverseness" of the animal, while others follow an "objective or reasonable animal" approach. They also identify a third approach, which takes both objective and subjective factors into account.

(d) The plaintiff must have been present lawfully at the place where the harm was inflicted (Van Meyeren supra 20; O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 326; see Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 384 about the approaches to this, namely whether the requirement is a lawful purpose or a legal right on the part of the plaintiff. Neethling and Potgieter (Law of Delict 438) regard the "legal right" approach as being preferable).

The following defences can be raised against the actio de pauperie (Neethling and Potgieter Law of Delict 437; Loubser and Midgley The Law of Delict in South Africa 462-463):

(a) Vis maior or an act of God;

(b) Culpable or provocative conduct on the part of the victim;

(c) Culpable or provocative conduct on the part of a third party;

(d) Provocation by another animal;

(e) The person who was attacked was not on the property lawfully (Van Meyeren supra 20; O'Callaghan v Chaplin supra 326 - the court uses the example of a housebreaker who is bitten by a dog); and

(f) Volenti non fit iniuria.

In Lever v Purdy (supra) the court identified two instances where the culpable conduct of a third party could constitute defences against the actio de pauperie (21C-25F; see also Van Meyeren v Cloete supra 23):

(a) Where a third party through a positive act (such as provocation) caused the animal to inflict an injury upon the victim; or

(b) Where the third party was in control of the animal and failed to prevent the animal from harming the victim.

The court in Lever v Purdy (supra 21C-25 F) traced these defences back to Justinian and through Roman-Dutch Law to the present day.

In the Van Meyeren case the appellant wanted the court to develop the common law to allow for the third-party defence to be extended to a situation where the harm would not have occurred "but for" the negligent conduct of the third party in circumstances where the third party had no control over the animal. As indicated above, both the court a quo and the SCA held that the third-party defence could not be extended in this manner.

4 3 Is it time to put the actio de pauperie to rest?

From case law dating back to O'Callaghan v Chaplin (supra) it is clear that the action has been a part of South African law for decades:

"In my opinion, therefore, obsolescence of the option of noxae deditio, leaving the basis of liability under the law of the Twelve Tables intact, would be a perfectly possible, and indeed a satisfactory, legal position"

In Loriza Brahman v Dippenaar (supra) the defendant argued that the actio had fallen into disuse (see also Scott 2003 TSAR 194). The court held:

"[t]he time to carry the actio de pauperie to the grave, despite its age, has not yet arrived" (own translation from the Afrikaans)." (par 16)

An argument in favour of retaining strict liability for damage caused by animals is that of the risk theory. Knobel (2011 THRHR 639) regards it as the best explanation of why certain forms of delictual liability are strict, rather than fault-based. Scott describes the actio de pauperie as the oldest form of risk liability (2003 TSAR 194). Neethling and Potgieter (Law of Delict 434) write that the risk theory "provides a satisfactory explanation for most of the instances of strict liability which are recognised in our law." The risk principle entails that the defendant creates the risk by keeping the animal; hence, that is a justification for holding him liable should that danger materialise (Knobel 2011 THRHR 639; Scott 2019 THRHR 331). This sentiment is echoed by the courts. In the Loriza Brahman case (supra 16) the Court held as follows:

"[I]f one follows the approach that delictual liability ought to be based on fault, the actio de pauperie would appear as "not elegant and anomalous". If, however one's point of departure is a broader vision of delictual liability, that includes deserving cases of risk liability, then the question only is whether the actio de pauperie fulfils a deserving role." (own translation from the Afrikaans).

Loubser and Midgley (The Law of Delict in South Africa 438) see regard liability as "a type of tax on activities that attract such liability, rather than a penalty for engaging in it".

Knobel (2011 THRHR 639) states that even though the actio has its origin "in a more primitive legal system" in terms of which an owner is punished for harm caused by the animal to punish an owner for harm caused by an animal, strict liability can be justified in a modern legal system based on the risk principle.

5 Conclusion

The actio de pauperie remains a part of South African law despite the fact that our law of delict follows a generalising approach. In addition, the SCA has brushed aside questions regarding its continued existence in South African law. In Van Meyeren v Cloete (supra) the SCA reiterated the stance it adopted in the Loriza Brahman case, namely that the action remains a part of our law. The SCA has held, furthermore, that the third-party defence should not extend to the situation where the harm would not have occurred "but for" the negligent conduct of the third party in circumstances where the third party had no control over the animal. According to several authors, the risk principle is a justification for the continued presence of the actio in modern South African law as a form of strict liability. Keeping domestic animals comes with the risk that they may cause harm and if this risk materialises, it should be the defendant who is held liable for the harm that ensues from the conduct of the animal. (Knobel 2011 THRHR 639, Scott 2019 THRHR 331). The actio de pauperie, despite the onslaughts on its existence, lives another day and in the same guise.

André Mukheibir

Nelson Mandela University

^rND^1A01^nKonanani Happy^sRaligilia^rND^1A01^nKodisang Mpho^sBokaba^rND^1A01^nKonanani Happy^sRaligilia^rND^1A01^nKodisang Mpho^sBokaba^rND^1A01^nKonanani Happy^sRaligilia^rND^1A01^nKodisang Mpho^sBokabaCASES

Breach of the implied duty to preserve mutual trust and confidence in an employment relationship: a case study of - Moyo v Old Mutual Limited (22791/2019) [2019] ZAGPJHC 229 (30 July 2019)

1 Introduction

This case note is intended to revisit the contentious aspect of the implied duties of South African labour law in the individual employment relationship. Significantly, the case note intends to remind the reader about the importance of adhering to certain implied duties in the contract of employment. In this regard, the implied duty to preserve mutual trust and confidence is the central theme of this case note. On the one hand, the implied duty to safeguard mutual trust and confidence imposes an obligation upon the employer to conduct itself in a manner not likely to destroy, jeopardise, or seriously damage the trust relationship and confidence in the employment relationship. On the other hand, this implied duty is becoming a significant yardstick used by employers to address contractual labour disputes in South Africa. In order for an employer to invoke this implied duty, it must be expected that the employee would have to conduct him or herself in a manner likely to demonstrate to his employer loyalty, good faith and cooperation.

Against this background, the recent case of Moyo v Old Mutual (22791/2019) [2019] ZAGPJHC 229 (30 July 2019) (Moyo) demonstrates the impact of a breach of the implied duty to preserve mutual trust and confidence on the employment relationship. This case note intends to examine the implied obligation that rests upon the employer to safeguard trust and confidence in the relationship. The case note further reflects on the implied duty of employees to safeguard and protect mutual trust and confidence. After all, trust forms the basic fundamental core of the employment relationship, and any breach of this duty is likely to result in an irretrievable breakdown of the employment relationship. Once there is a breakdown of trust and confidence, it remains a mammoth task to restore the relationship.

2 Facts of the case

Mr Peter Moyo was an employee and also the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Old Mutual Limited (Old Mutual), the employer (Moyo v Old Mutual (22791/2019) [2019] ZAGPJHC 229 (30 July 2019) par 1). This court action was triggered by a series of events that began in March 2018 when Moyo questioned certain conflict-of-interest elements involving Mr Trevor Manuel, (Chairperson of the Board governing the employer) and Rothschild (Moyo v Old Mutual supra par 3). This conflict of interest stems from a large multibillion rand commercial project on the delisting of Old Mutual PLC from the London Stock Exchange and the proposed listing of the employer on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (Moyo v Old Mutual supra par 3). It is important to note that Manuel was a director of all these companies.

As soon as it became apparent to Moyo that there was a potential conflict of interest on the part of Manuel, he openly voiced his concerns and cautioned him not to participate in the discussion meetings (Moyo v Old Mutual supra par 5). However, Manuel ignored and failed to act on Moyo's objections, proceeding to participate in the discussion of this matter. From that point onward, Moyo noticed that his employment relationship with Manuel turned sour (Moyo v Old Mutual supra par 6) because Manuel continued to ignore Moyo's further advice relating to improper non-disclosure of a payment amounting to millions of rand paid by the employer in respect of the chairperson's legal fees (Moyo v Old Mutual supra par 7). Efforts to restore a good employment relationship between Moyo and Manuel yielded no results. On 23 May 2019, Moyo was suspended and was ultimately dismissed on 17 June 2019 for failure to discharge his fiduciary duties as a director of the employer. It was alleged that Moyo made certain disclosures about payment of Manuel's legal fees before allegations of a conflict of interest were then made against him in respect of another matter. This prompted Moyo to lodge an application in the High Court reinstating him to his position as CEO of Old Mutual.

3 Legal issues

Legal issues arising from this case are (a) whether the dismissal of Moyo was in line with the parties' contractual obligations and (b) whether the Protection of Disclosures Act (26 of 2000) is applicable in the matter.

4 Analysis of the employment relationship

The employee and employer relationship is founded on obligatory duties to work by the former, and the duty to pay wages and salaries by the latter (Fouche "Common Law Contract of Employment" in A Practical Guide to Labour Law 8ed (2015) 16 par 266). These obligatory duties fall within the confines of the contract of employment, even though not all these duties may invoke contractual elements. However, the Moyo case espouses all elements of an employment relationship, which is founded on the prescripts of contractual obligations.

The employment relationship between Moyo and Old Mutual can best be described as one where labour is bought and sold as a commodity (Davidson The Judiciary and the Development of Employment Law (1984) 7). In this instance, Old Mutual as an employer owns labour and further regulates Moyo, who is an employee. In the words of Kahn Freund, "there can be no employment relationship without a power to command and a duty to obey, that is, without this element of subordination in which lawyers rightly see the hallmark of the contract of employment" (Davies and Freedland Kahn Freund's Labour and the Law 3ed (1983) 9). Furthermore, Strydom rightly justified this regulation when he asserted that the "employer's right to control the workforce is the cornerstone of the employment relationship" (Strydom The Employer Prerogative from Labour Law Perspective (LLD Thesis UNISA) 1997 1-38). Thus, the control dynamism of the employment relationship is deeply embedded in the jurisprudential philosophy of the contract of employment. In other words, the duty of subordination forms a central part in the contract of employment. The duty of subordination entails that the employee ought to conduct him or herself in an honest and obedient manner and also be willing to cooperate with the employer at all material times (Impala Platinum Limited v Zirk Bernardus Jansen (JA100/14)). In terms of power dynamics, this expressly implies that Old Mutual finds itself in a position of authority over Moyo. In return, Moyo is expected to carry out his employment duties subject to Old Mutual authority and further to obey the lawful orders that the employer expects him to carry out.

Generally, disobeying the lawful commands of the employer by an employee may constitute the misconduct of insubordination. For this reason, the discipline and ultimate dismissal of the employee may be justifiable, as long as those actions are compliant with both the substantive and procedural requirements for dismissal.

5 Implied duty to safeguard of mutual trust and confidence in Moyo

Although the duty to safeguard trust and confidence in the employment relationship was not expressly explored in the Moyo case, its implied significance could evidently be felt in the case. This is because this duty imposes an obligation on both parties in the contract of employment. However, it is significant to note that a much greater obligation of this duty is imposed on the employer. In the present case, the employer is Old Mutual. In the landmark case of Malik v Bank of Credit & Commerce International (In liquidation) [1998] AC 30) (Malik), Lord Steyn held that an employer may not, "without reasonable and proper cause, conduct itself in a manner calculated and likely to destroy or seriously damage the relationship of confidence and trust between employer and employee" (par 45). The Malik case laid a greater obligation at the doorstep of the employer not to act in a manner likely to breach mutual trust and confidence. In other words, not only is Moyo expected to act in good faith and fair dealing, but so too is Old Mutual.

The same principle of good faith and fair dealing was raised in the case of Wallace v United Grain Growers Ltd 1997 CanLII 332 (par 139), where Judge McLachlin held:

"A contract of employment is typically of longer term and more personal in nature than most contracts, and involves greater mutual dependence and trust, with a correspondingly greater opportunity for harm or abuse. It is quite logical to imply that parties to such a contract would, if they turned their minds to the issue, mutually agree that they would take reasonable steps to protect each other from such harm, or at least would not deliberately and maliciously avail themselves of an opportunity to cause it."