Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Obiter

On-line version ISSN 2709-555X

Print version ISSN 1682-5853

Obiter vol.42 n.1 Port Elizabeth 2021

ARTICLES

Regulating construction procurement law in South Africa - does the new framework for infrastructure delivery and procurement management undermine the rule of law?

Allison Anthony

BA LLB LLM LLD; Senior Lecturer of Public Procurement Law, University of South Africa

SUMMARY

Recently, there have been numerous challenges in the legal regulation of construction procurement in South Africa. The Construction Industry Development Board and the National Treasury have brought about a number of new rules in the form of standards and frameworks in order to remove any contradictions and misalignment with applicable legislation. This article looks at the changes that have taken place in the regulation of construction procurement law and whether the new rules indeed assist in removing the challenges posed by previous rules. The research question to be answered is whether the new rules are in fact lawful.

1 INTRODUCTION

Public procurement is generally known as the process through which the government contracts with a private party for the provision of goods, works or services to or on behalf of the government. In South Africa, public procurement is constitutionally regulated by section 217, which provides that when organs of state contract for goods or services, they should do so in accordance with a system that is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective.1 Public procurement is further regulated by various statutes, including the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA),2 the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act3 and the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (PAJA).4 Further legislation includes the Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act,5 the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act (MSA),6 the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act (BBBEEA)7 and the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA).8 These statutes regulate procurement throughout South Africa, irrespective of the type of procurement or the industry in which it takes place. When it comes to specific types of procurement, these laws and additional industry-specific rules apply. This is the case for the procurement of works and services in the construction industry. The construction industry is regulated by the Construction Industry Development Board Act 38 of 2000, which establishes the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) as the regulatory body for the industry. Its sphere of regulation includes procurement in the industry (or better known as construction procurement). The CIDB is empowered to regulate and create best practice guidelines that regulate construction procurement beyond the Act and its regulations. The CIDB is thus given powers to create subordinate legislation for construction procurement in the form of these guidelines, which form the subject of this article.

In addition to the above, section 76 of the PFMA grants the National Treasury the authority to publish further rules for the regulation of public procurement.9 Therefore, public procurement, and construction procurement in particular, is regulated within a highly fragmented legal framework.

In 2016, National Treasury published an instruction note based on section 76 of the PFMA, in terms of which the Standard for Infrastructure Procurement and Delivery Management (SIPDM) was brought into operation and created a parallel legal system for the regulation of construction procurement. The standard effectively created a new system based on infrastructure delivery, and not construction works, as does the CIDB Act, its regulations, CIDB best practice guidelines and practice notes. This conclusion is based on the contradictory terms and definitions used in the SIPDM compared to the CIDB prescripts. Much misalignment between the SIPDM and CIDB prescripts ensued and an attempt was made to correct this. The result has been the new Framework for Infrastructure Delivery and Procurement Management (FIDPM) that came into operation on 1 October 2019, and which repealed the SIPDM. The FIDPM appears to be only a framework, as it is couched in very wide and vague terms that leave much room for the exercise of discretion. It therefore does not contain any substantive rules. The term "framework" is not defined in the document; however, the Oxford English Dictionary describes it as "a basic structure underlying a system, concept, or text". It would therefore be logical to conclude that the document does not and was not intended to provide detailed rules. The problem this creates is that open-ended terminology leaves room for the exercise of too much discretion, which is not appropriate in a public procurement setting as it threatens to result in unfair procedures that ultimately undermine the pillars of procurement in section 217 of the Constitution. This article explores whether the new framework will in fact remove the current contradictions and misalignment brought about by the SIPDM and whether it assists in the regulation of construction procurement law in any way. The article will also determine whether the publication of this document undermines the rule of law and is thus unlawful.

2 CONFUSING LAWS WITH GUIDELINES

In the first instance, it is interesting that the title of the document has been changed from "infrastructure procurement and delivery management" to "infrastructure delivery and procurement management". This indicates that the new document (FIDPM) is aimed at a different process. Neither "delivery management" nor "procurement management" is defined in the SIPDM and FIDPM. Therefore, it is unclear what the purpose of the change in title is. The title of the SIPDM appears to regulate infrastructure procurement and manage the delivery of such infrastructure, whereas the FIDPM intends to regulate the delivery of infrastructure while managing the procurement process in achieving this. The importance in the difference lies in the interpretation of certain terms that are either unclear, vague or are undefined. Often a court will take cognisance of the title of a document in attributing meaning to a word, phrase or provision by determining what the document aims to regulate. The difference in title is thus problematic since the FIDPM will repeal the SIPDM. Normally, when one law repeals another, the former is merely indicated as an amendment law so as to avoid confusion with regard to which law is being repealed.

Secondly, it is interesting to note that the document has been changed from a standard to a framework. A "standard" is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "something used as a measure, norm or model in comparative evaluations". Therefore, based on the definitions of the words "standard" and "framework", it can be said that the SIPDM was intended to act as a model against which all infrastructure procurement must be measured. The framework, on the other, suggests that it serves merely as a concept that underlies a greater system, thereby creating the impression that further rules will be published for the regulation of infrastructure delivery and procurement management. By implication, the lack of detailed rules in the FIDPM and the consequent repeal of the SIPDM leaves the construction industry with the CIDB prescripts and the framework as its source of regulation. Since the rules in the CIDB prescripts are detailed and regulate every part of the construction procurement process and are also aligned with the CIDB Act and its regulations, it is difficult to understand the purpose of the FIDPM. It is noted in the foreword of the document that it is intended to "prescribe the minimum requirement for effective governance of infrastructure delivery and procurement management". However, these terms are not used in the CIDB Act, its regulations or its prescripts. It is thus unclear how it is meant to supplement the rules already enacted in terms of the CIDB Act.

Based on the legal status of a framework vis-á-vis that of an Act and its subordinate legislation, the framework will be an optional document for organs of state and contractors to implement. Furthermore, until the CIDB Act has been repealed, the legal regulation of construction procurement (as opposed to infrastructure procurement) in terms of the Act is still applicable. However, the CIDB and FIDPM are aimed at different types of procurement in that the former is aimed at "construction procurement" and the latter at "infrastructure procurement". This difference and the legal implications thereof have been traversed by the current author (see Anthony "Re-Categorising Public Procurement in South Africa: Construction Works as a Special Case" 2019 22 Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal 1-21). If the FIDPM is intended to replace the SIPDM, it will need more substantial rules to create a standard model for infrastructure procurement. Moreover, the FIDPM will need more rules of substance and not merely operational guidelines for the procurement process, as it currently provides.

3 WORKING OF THE FIDPM

It appears that the FIDPM is intended to serve as a guide for implementation of the Infrastructure Delivery Management System (IDMS), which the FIDPM states must be done through infrastructure delivery management processes; these consist of portfolio, programme, projects, operations and management of infrastructure as well as infrastructure procurement gates. This terminology is inconsistent with that used in the CIDB Act and its regulations, thereby once again, as in the case of the SIPDM, creating a parallel system for the regulation of construction procurement. The FIDPM further states that it allocates responsibilities for activities and decision making at control points, stages (defined in the FIDPM as "a collection of periodical and logically related activities in the Project Management Control Stages that culminates in the completion of an end of stage deliverable") and procurement gates (defined as "a control point at the end of a process where a decision is required before proceeding to the next process or activity"). Furthermore, the framework refers to "construction" only and not "construction works" as the CIDB system does. "Construction" is defined as "everything constructed or resulting from construction operations". The latter is not defined. Another problematic definition is that of "contract management", which is indicated as "applying the terms and conditions, including the agreed procedures for the administration thereof". This definition should refer to the terms and conditions stated in the written contract; in the absence thereof, this could refer to terms and conditions agreed upon orally. The "administration thereof" could refer to the contract or the actual construction, which may differ at times, especially in the case of oral terms and conditions that were added subsequent to signing the contract. The definitions that refer to "infrastructure" in the framework are the same as those in the SIPDM, which means that these have not been aligned to the CIDB Act or any other legislation that regulates public procurement. They thus remain contrary to the law currently regulating construction procurement. Furthermore, where legislation is referred to in the framework, it is done either incorrectly or such references are incomplete. It could therefore refer to any version of the legislation, since the law is ever-changing and often amended. The same applies to National Treasury guidelines. It is submitted that perhaps this was done deliberately in an attempt to avoid constant review of the framework.

In addition, paragraph 5 of the FIDPM states that "project processes are typically linear". This section of the document refers to stages of the procurement process that must be followed and "gates" at the end of each stage where approval for a "stage deliverable" is required before the next stage can be started. This reinforces the so-called "check-box" attitude towards public procurement generally found among officials instead of a relational approach to the interlinked phases of the procurement process. This "check-box" approach can be described as each role player in the supply chain simply doing its part and handing the work over to the next role player in line. A relational approach to procurement, on the other hand, can be described as a chain in which each element of the chain is interlinked with the next. This means that each role player's action is connected to the previous and the next action in order to bring about the desired result, which is the effective and efficient procurement of goods, works and services. Actors of each activity should approach the activity with the understanding that it links to the activity before and after it. In other words, it is not an isolated action that is disposed of after the activity is completed. Therefore, the wording of the FIDPM is important in delivering the message to procurement officials that public procurement is a process in which each activity relates to the previous and the next one in order to deliver the outcome, which is infrastructure. However, the manner in which the FIDPM is (not only) written, but also illustrated, is indicative of a check-box process to be followed by officials.

4 NEW TERMINOLOGY

The FIDPM further introduces a range of new acronyms to the regulation of procurement in the construction industry. The Infrastructure Asset Management Act (IAMP), Infrastructure Procurement Strategy (IPS), Infrastructure Programme Management Plan (IPMP), Infrastructure Programme Implementation Plan (IPIP), Operations Management Plan (OMP) and the Maintenance Management Plan (MMP) are new to the regulation of construction procurement. These programmes have technical definitions, indicating that they are aimed at regulating operations within the procurement process. These should be aligned with the existing legislation or the legislation should be amended accordingly.

5 COMPARISON OF THE RULES AND DOCUMENTS

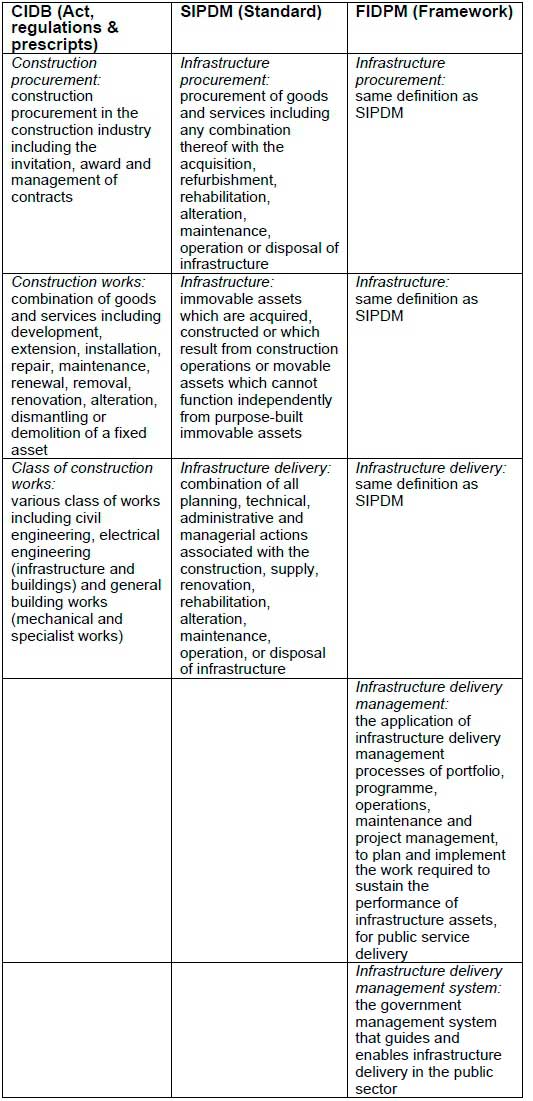

What follows is an illustration in table form of the contradictory provisions of the three different systems in construction procurement law.

From this table, it can be clearly seen that the systems under the various documents are vastly different. The CIDB Act as legislation gives the CIDB (as a juristic entity) the power to regulate public procurement. National Treasury is empowered in terms of section 76 of the PFMA to issue instructions for the regulation of public procurement. However, these instruments do not have the same legal status as the CIDB Act. They thus need to be brought in line with the Act and its procurement process, which is based on construction procurement, construction works and classes of construction works. The CIDB Act does not make any reference to infrastructure procurement, delivery or management. This difference is significant since the definitions for goods and services to be provided under these documents differ greatly. What is procured in terms of each document differs, which effectively creates two different systems of procurement in the construction industry. The FIDPM continues along the same vein as the SIPDM, and therefore the misalignment with legislation continues.

6 LAWFULNESS OF THE FIDPM

It is submitted that the FIDPM adds little, if any, value to the construction procurement process from a legal perspective. For it to add value, it would need to fill a particular gap in the legal framework, address a specific problem or make implementation of the process easier. This it fails to do. More importantly, the FIDPM is entirely contradictory to the legal framework of construction procurement and therefore goes against the rule of law. What follows is a discussion on the various ways in which the FIDPM undermines the rule of law.

6 1 Uncertain and vague

It is submitted that legal certainty and predictability are principles of the rule of law. This means that legal rules should be clear and understandable to those who must apply them. This was confirmed by the Constitutional Court in Dawood v Minister of Home Affairs,10where it was held that "[i]t is an important principle of the rule of law that rules be stated in a clear and accessible manner".11 In Affordable Medicines Trust v Minister of Health,12the court confirmed this principle again by holding that although absolute legal certainty is not required, the law must "indicate with reasonable certainty to those who are bound by it, what is required of them so that they may regulate their conduct accordingly".13 The question to be answered is whether the law conveys a reasonably certain meaning to those affected by it.14 Based on the parallel system created by the SIPDM initially, and continued by the FIDPM, it is submitted that the rule of law is undermined. The court in the Affordable Medicines Trust case further held:

"The doctrine of vagueness is founded on the rule of law, which ... is a foundational value of our constitutional democracy. It requires that laws must be written in a clear and accessible manner. ... The doctrine of vagueness must recognise the role of government to further legitimate social and economic objectives. And should not be used unduly to impede or prevent the furtherance of such objectives."15

Furthermore, Kidd notes that clarity applies to:

"all administrative decisions which require persons to act in a particular way. Delegated legislation . would be the obvious arena in which clarity would be important. Legislation might provide for administrators to issue directives (or similar notices) to persons requiring them to take specified steps in order to comply with the law. Moreover, most permits, licences or other types of authorisations would require persons to comply with conditions stipulated in those authorisation documents. These would all have to be sufficiently clear in order that the affected person would know what was required of him or her."16

Moreover, the court in Allpay Consolidated Investment Holdings (Pty) Ltd v Chief Executive Officer, South African Social Security Agency17held that "vagueness can render a procurement process ... procedurally unfair under s 6(2)(c) of PAJA".18

Furthermore, in Minister of Health NO v New Clicks South Africa (Pty) Ltd,19 the Constitutional Court held that it "is implicit in all empowering legislation that regulations must be consistent with, and not contradict, one another".20 The FIDPM, which contradicts the CIDB prescripts, is not in line with this.

6 2 Irrational

It is trite that the principle of legality is a component of the rule of law. This principle is the general constitutional principle under which the exercise of all public power is tested for lawfulness. It expresses the idea that the exercise of all public power is only legitimate when it is lawful.21 It entails rationality, which requires that the reason for the action (in this case, the creation of the FIDPM) must be rationally connected to the objective sought to be achieved (in this case, alignment of the rules in construction procurement).22 To this end, the Constitutional Court held in Albutt v Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation23that:

"[t]he Executive has a wide discretion in selecting means to achieve its constitutionally permissible objectives ... [b]ut, where the decision is challenged on the grounds of rationality, courts are obliged to examine the means selected to determine whether they are rationally related to the objective sought to be achieved . if objectively speaking they are not, they fall short of the standard demanded by the Constitution."24

In order to determine whether a decision is rational, the court in Democratic Alliance v President of the Republic of South Africa25held that the enquiry entails asking, first, whether any relevant factors may have been ignored, secondly, whether failure to consider material factors is rationally related to the purpose for which the power was conferred, and lastly, whether ignoring the relevant factors taints the process with irrationality and thus renders the final decision irrational.26

It is submitted that the purpose of the FIDPM - that is, removing the misalignment created by the SIPDM by replacing it with the FIDPM - is not achieved. Furthermore, the failure to consider the implications of the FIDPM on the legal framework of construction procurement results in the rules being arbitrary. The decision to publish the FIDPM is thus irrational.

6 3 Procedurally unfair

With regard to procedural unfairness, Murcott notes:

"[L]egality imposes a duty to consult where a failure to consult will amount to failure to take into account information at the disposal of the decision-maker which ought rationally to be taken into account by the decision-maker." 27

She notes this in light of Freedom Under Law v National Director of Public Prosecutions,28in which the court held that the principle of legality requires that a decision-maker exercises the powers conferred on him or her lawfully, rationally and in good faith. Rationality includes a procedural element29 and a refusal to include relevant stakeholders, or a decision to receive representations from some to the exclusion of others, may render a decision irrational.30

The court in Masethla v President of the Republic of South Africa31held that the principle of legality consists not only of rationality, but also "fundamental fairness".32To this end, the court held:

"The Constitution requires more; it places further significant constraint on how public power is exercised through the Bill of Rights and the founding principle enshrining the rule of law. It is a fundamental principle of fairness that those who exercise public power must act fairly. In my view, the rule of law imposes a duty on those who exercise executive powers not only to refrain from acting arbitrarily, but also to act fairly when they make decisions that adversely affect an individual."33

The court further held that the goals of the Constitution include accountability, responsiveness and openness. It is apparent from the Constitution that the democratic government envisioned is one that is accountable, transparent and requires participation in decision-making.34Therefore, to comply with the audi alteram partem rule as a component of procedural fairness, the decision makers (National Treasury) should not only have given stakeholders an opportunity to make submissions, but were also under an obligation to take those submissions into account. Relevant and material factors such as the contradiction of the FIDPM with previous CIDB rules should have been considered before publishing the rules. In the absence of such consideration, the rules were brought into operation in a procedurally unfair manner.

In the Carmichele v Minister of Safety and Security35matter, the court held that the Constitution is not merely a formal document that regulates public power. It is a document that embodies an objective, normative value system.36 The court in Masethla held:

"The requirement to act fairly is part of this objective normative value system and must therefore guide the exercise of public power. It imposes a duty on decision-makers to act fairly. Acting fairly provides the decision-maker with the opportunity to hear the side of the individual to be affected by the decision. It enables the decision-maker to make a decision after considering all relevant facts and circumstances. This minimises arbitrariness. There is indeed an inter-relationship between failure to act fairly and arbitrariness. In this sense, the requirement of the rule of law that the exercise of public power should not be arbitrary, has both a procedural and substantive component. Rationality deals with the substantive component, the requirement that the decision must be rationally related to the purpose for which the power was given and the existence of lawful reason for the action taken. The procedural component is concerned with the manner in which the decision was taken. It imposes an obligation on the decision-maker to act fairly. To hold otherwise would result in executive decisions which have been arrived at by a procedure which was clearly unfair being immune from review."37

7 JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE FIDPM

In order to manage decisions made in terms of an unlawful FIDPM, organs of state may have to take such decisions on judicial review. A decision may be taken on review by either the National Treasury itself, or organs of state that implement the FIDPM.

7 1 Judicial review by National Treasury

National Treasury, as the author of the FIDPM, would be entitled to approach a court of law to set aside decisions that are made based on the FIDPM and which may be unlawful. Such decisions would be judged against the principle of legality. This was confirmed by the Constitutional Court in State Information Technology Agency SOC Limited v Gijima Holdings (Pty) Ltd.38The action could be challenged on all the above grounds of vagueness, rationality, legal certainty and procedural fairness in not having taken relevant factors into consideration.

7 2 Judicial review by organs of state

Based on the Gijima judgment, organs of state that implement the FIDPM and apply for decisions made in such implementation to be set aside may rely on PAJA to do so. Organs of state would then challenge such decisions on any of the grounds of review listed in section 6 of PAJA. This would entail challenging decisions based on vagueness and the lack of reasonableness and lawfulness of the rules. The grounds of review include a catch-all ground in section 6(2)(i), which provides that administrative action may be set aside if such action is otherwise unconstitutional or unlawful in that it undermines the rule of law.

8 THE PUBLIC PROCUREMENT BILL

In February this year, after much speculation as to what the new procurement law would entail, the Public Procurement Bill39 was published for public comment. The Bill is aimed at unifying all pieces of legislation that regulate public procurement in South Africa, including infrastructure procurement. It is disappointing that the Bill does not address the issue of contradictory rules in the construction industry. Instead, it perpetuates this by providing in section 82(2) of the Bill that a

"procurement system for infrastructure ... must provide for matters that comply with any standard for infrastructure procurement and delivery management as may be determined by instruction."

Therefore, it appears that the FIDPM will still be in operation, contrary to the rules of the CIDB, which are legally authorised to regulate infrastructure procurement.

9 CONCLUSION

Based on the above contradictions, unexplained additions and vague or incomplete definitions, it is submitted that the FIDPM should not come into operation unless it is aligned with the CIDB legislation and prescripts. Any misalignment or contradiction can be solved by updating the prescripts of the CIDB, instead of the onerous process of creating standards and frameworks of which the legal status is questionable. If a new system in terms of infrastructure procurement as opposed to construction procurement is desired, the CIDB Act and its regulations can be amended to provide for such an amended system. Furthermore, in the absence of repeal, the CIDB system remains in force. Therefore, a procurement process based on infrastructure in terms of the standard or framework and a process based on construction in terms of the CIDB legislation exist alongside one another. The FIDPM states in paragraph 6:

"Infrastructure procurement shall be undertaken in accordance with all applicable Infrastructure Procurement-related legislation and this Framework . Infrastructure procurement shall be implemented in accordance with procurement gates prescribed in clause 6.2 and the CIDB prescripts."

The implications of this go without saying. It is thus submitted that the regulation of procurement in the construction industry should remain the mandate of the CIDB, which was established in legislation for this purpose. This will ensure that the financial, operational and legal interests of the industry are regulated by a body that is legally appointed and equipped to do so. The recent attempts at various bodies regulating the industry and consequently causing disjointed processes and stakeholder confusion is certainly leading to a situation in which too many cooks in the kitchen are spoiling the broth.

1 See s 217(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution).

2 1 of 1999.

3 5 of 2000.

4 3 of 2000.

5 56 of 2003.

6 32 of 2000.

7 53 of 2003.

8 2 of 2000.

9 S 76(4) of the PFMA provides: "National Treasury may make regulations or issue instruction applicable to all institutions, to which this Act applies, concerning (a) any matter that may be prescribed for all institutions in terms of this Act; (b) financial management and internal control; (c) the determination of a framework for an appropriate procurement and provisioning system which is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective; (d) audit committees, their appointment and their functioning; (e) internal audit components and their functioning; (f) the administration of this Act; and (g) any other matter that may facilitate the application of this Act."

10 2000 (3) SA 936 (CC).

11 Par 47.

12 2006 (3) SA 247 (CC) par 108-110.

13 See par 108. See also Investigating Directorate: Serious Economic Offences v Hyundai Motor Distributors (Pty) Ltd: In re Hyundai Motor Distributors (Pty) Ltd v Smit NO 2001 (1) SA 545 (CC) par 24, where the court held that the legislature "is under a duty to pass legislation that is reasonably clear and precise, enabling citizens and officials to understand what is expected of them". This, it is submitted, should be extended to the executive which is given powers to create delegated legislation.

14 Affordable Medicines Trust v Minister of Health supra par 110.

15 Par 108.

16 Kidd "Reasonableness" in Bleazard, Budlender, Corder, Kidd, Maree, Murcott and Webber Administrative Justice in South Africa: An Introduction (2015) 186-187. [ Links ]

17 2014 (1) SA 604 (CC).

18 Par 88.

19 2006 (2) SA 311 (CC).

20 Par 246.

21 Fedsure Life Assurance Ltd v Greater Johannesburg Transitional Metropolitan Council 1999 (1) SA 374 (CC) par 59.

22 Rationality was said to be the "minimum threshold requirement applicable to the exercise of all public power by members of the Executive and other functionaries" in Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of SA: In re Ex parte President of the Republic of South Africa 2000 (2) SA 674 (CC) par 90.

23 2010 (3) SA 293 (C).

24 Par 51.

25 2013 (1) SA 248 (CC).

26 See par 39.

27 Murcott "Procedural Fairness" in Bleazard et al Administrative Justice in South Africa: An Introduction 168.

28 2014 (1) SA 253 (GNP).

29 Par 127.

30 Par 165.

31 2008 (1) BCLR 1 (CC).

32 See par 179 (author's own emphasis).

33 Par 179-180.

34 Par 181.

35 2001 (4) SA 938 (CC).

36 Par 54.

37 Masethla v President of the Republic of South Africa supra par 183-184.

38 2018 (2) SA 23 (CC). See specifically par 27-28.

39 GG 43030 of 2020-02-19.