Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Obiter

On-line version ISSN 2709-555X

Print version ISSN 1682-5853

Obiter vol.41 n.3 Port Elizabeth 2020

ARTICLES

The international labour organisation in pursuit of decent work in Southern Africa: an appraisal

William Manga Mokofe

LLB LLM LLD Certificate in Practical Labour Law Senior Lecturer, Pearson Institute of Higher Education

SUMMARY

This article examines the role of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), regional standards, and the "decent work agenda" in addressing challenges facing nonstandard workers in southern Africa. Employees in traditional full-time employment are well protected in some southern African states, but the regulation currently available is largely unable to protect non-standard workers, and in numerous instances workers are regarded as "non-standard", on the basis of a narrow interpretation of the term "employee". Casualisation and externalisation have resulted in the exclusion of numerous workers from the protection provided by labour legislation, and union cover for non-standard workers is very low. The article further discusses the relationship between non-standard employment and labour migration in southern Africa. Light is also shed on regional standards, the challenges of unemployment, poverty, and income inequality, and labour-market transitions in southern Africa.

1 ILO INFLUENCE ON THE LABOUR LAW SYSTEMS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA AND OTHER FACTORS AFFECTING NON-STANDARD WORK

The ILO has played a major role in influencing the labour-law systems of southern Africa. Fenwick and Kalula1 suggest that there are two ways in which the ILO has principally influenced labour law in the region. First, by ratifying ILO Conventions, nations fall under the influence of the ILO's standard supervision system.2 Since its establishment in 1992, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has encouraged member states to ratify and implement the core ILO standards. All SADC member states, save for Madagascar and Namibia, have ratified all of the core ILO Conventions.3

The second way in which the ILO has influenced labour law in the region is by offering technical assistance. The ILO offers countries technical assistance to re-orientate their labour law and labour relations systems. Currently, for example, through its "In Focus Programme on Social Dialogue, Labour Law and Labour Administration", the ILO is running at least two key projects tasked with the legal regulation of labour markets in the SADC region.4 In general terms, these projects help countries to develop their labour legislation in line with international standards and to advance their capacity in key areas such as dispute resolution. In particular, the ILO has assisted most countries in southern Africa - for example, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, and Swaziland - to develop labour legislation that conforms to international standards.5 In addition, it has assisted in improving the capacity of key institutions and actors in the region through technical collaboration, for example, in the ILO/Swiss projects entitled "Regional Conflict Management and Enterprise-based Development and Strengthening Labour Administration in Southern Africa" (SLASA).6

In 1999, a SADC labour conference was arranged with the support of its Employment and Labour Sector (ELS) in collaboration with the ILO/Swiss Project for the "Prevention and Resolution of Conflicts and the Promotion of Workplace Democracy". The conference presented wide-ranging debate on three themes: minimum standards; collective bargaining; and dispute prevention and resolution.7

For instance, the ILO/Swiss Project for "Regional Conflict Management and Enterprise Development in Southern Africa" educated some 180 people on mediation and arbitration by offering a postgraduate diploma programme in dispute resolution.8 Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland and Zimbabwe were included in the project. Each country delegation included its Ministry of Labour, national union federations, national employers' organisations, and nominated universities. The project formed part of a broader vision of the ILO/Swiss Project to transform labour law and present modern and effective dispute resolution measures.9 The outcome of this project was a noteworthy improvement in dispute resolution capacity in the participating countries and a greater understanding of dispute resolution challenges in SADC countries:

"All participating countries experienced relatively volatile labour markets and poor dispute resolution capacity. All desired greater labour market stability, to attract investment and stimulate growth and create jobs. All recognised the importance of extending access to industrial justice through effective dispute resolution machinery. The creation of a skilled cadre of suitably qualified dispute resolution practitioners would make a material contribution to these objectives."10

An additional intervention under the ILO/Swiss "Project for Regional Conflict Management and Enterprise Development in Southern Africa" was the "Dialogue-Driven Performance Improvement in the Clothing and Textile Sector in South Africa".11 This project aimed to enhance the performance of mediators and arbitrators and to promote growth within the participating firms. In the main, the project offered employment to the rural female labour force and so increase access to health care in an area with a widespread incidence of HIV and AIDS. The project revealed that performance improvement can be achieved through a mix of good practice and skills development, buttressed by vigorous labour-management negotiation at industry level. This, in turn, assists in creating industrial policy regarding performance enhancement. 12 The report on the "Project to Advance Social Partnership and Promote Labour Peace in South Africa" (another ILO/Swiss Project) notes that:

"[R]espect for procedure has increased dramatically and procedural industrial action has virtually been eliminated from the South African industrial relations landscape. Settlement of disputes by conciliation is in excess of 70% and arbitrations are.completed on average within 120 days from date of referral to date of award".13

Interventions such as these by ILO/Swiss Project improve the ability of employment establishments to comply with the law. They also nurture cooperation between commercial enterprises and employees so as to achieve the protective and developmental objectives of the law. The dispute resolution mechanisms established in various southern African countries, such as the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) in South Africa are now working together at the local level to launch the Southern African Dispute Resolution Forum.

In addition, at the sub-regional level, the adoption of the Charter of Fundamental Social Rights by the SADC at its Dar-es-Salaam meeting on 5 August 2003 was a key development. The Charter is a resolute document that reinforces the need for protection, particularly of workers and vulnerable groups such as non-standard workers, and seeks to establish harmonised programmes of social security within the sub-region.14 Its provisions aim to extend social protection to both the employed and the unemployed. Article 10 provides that:

"SADC member states shall create an enabling environment that every worker shall have a right to adequate social protection and shall, regardless of status and the type of employment, enjoy adequate social security benefits. Persons who have been unable to either enter or re-enter the labour market and have no means of subsistence shall be able to receive sufficient resources and social assistance."

2 ILO INSTRUMENTS PERTINENT TO TACKLING THE ISSUE OF NON-STANDARD WORK IN SADC

Over the past century, the ILO has played a very significant role in developing labour standards and Conventions. Non-standard employment which covers workers outside of the traditional employment relationship has been acknowledged by the ILO. The changes to the traditional perceptions of work have received the attention of the ILO, and since 1990 this subject has been addressed at its annual conferences. The ILO has acknowledged the upsurge in non-standard work and the need to protect non-standard workers by means of the following:

"(a) Conventions and Recommendations pertaining to particular categories of non-standard workers, such as part-time workers and homeworkers;

(b) support for micro-enterprises in the informal economy;

(c) programmes like Strategies and Tools against Social Exclusion and Poverty (STEP) to promote the extension of social protection to informal workers;

(d) support for mutual health insurance schemes; and

(e) the continuance of work at its social security department commissioning research and investigating the extension of social- security protection to non-standard workers."15

2 1 Standards that deal with particular categories of non-standard employment

The ILO Termination of Employment Convention16 and Recommendation17control and offer guidance on the use of fixed-term or temporary employment contracts. The Convention regulates the termination of employment at the discretion of the employer, and allows for certain exclusions from all or some of its provisions which may relate to workers engaged under a contract of employment for a specified period or for a specified task, or to workers engaged on a casual basis for a short period. Furthermore, the Convention specifies that "adequate safeguards shall be provided against recourse to contracts of employment for a specified period of time, the aim of which is to avoid the protection resulting from this Convention".18

The Preamble to the Private Employment Agencies Convention 181 of 1997 notes the role that private employment agencies may play in an operational labour market, and also the need to protect these employees. The Convention applies, in principle, to all private employment agencies, all categories of employee (with the exception of seafarers), and all branches of economic activity. Ratifying states are obliged to take measures to guarantee that workers hired by private employment agencies are not deprived of the right to freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, and that the agencies do not discriminate against workers.

In addition, private employment agencies are not permitted, directly or indirectly, to charge workers any fees or costs - subject to a restricted number of exemptions. Further, ratifying states must guarantee that a system of licensing or certification, or other forms of governance, including national practices, controls the procedures and operations of private employment agencies. Ratifying states are further obliged to guarantee satisfactory protection and, where pertinent, to decide upon and allocate the particular responsibilities of private employment agencies and of user enterprises with regard to: collective bargaining; minimum wages; working hours and other working conditions; statutory social security benefits; access to training; protection in the field of occupational safety and health; compensation for occupational accidents or diseases; compensation in the event of insolvency; the protection of workers' claims; and maternity and parental protection and benefits.

The Private Employment Agencies Recommendation 188 of 1997 acts as an add-on to Convention 181 by providing, among other things, that workers employed by private employment agencies and made available to employer enterprises should, where applicable, have a written contract of employment stipulating their terms and conditions of employment, with information on such terms and conditions provided, at the very least, before the actual commencement of their assignments. Private employment agencies should avoid making employees available to employer enterprises if their placement is to replace workers who are on strike.

The Employment Relationship Recommendation provides that member states should formulate and apply, in consultation with the most representative employers' and workers' organisations, a national policy for revising at suitable periods and, if required, clarifying and adjusting, the scope of relevant laws and regulations in order to ensure active protection for workers in an employment relationship. Such a policy should include procedures: to give direction on establishing the presence of an employment relationship and on the difference between employed and self-employed workers; to contest hidden employment relationships that conceal the true legal standing of workers; to guarantee standards relevant to all forms of contractual arrangements, including those involving various parties, so that employed workers are protected; and to guarantee that such standards state who is accountable for offering such protection. Likewise, national policies should ensure the effective protection of workers, particularly those affected by vagueness regarding the nature of an employment relationship, including women workers and the most vulnerable workers.

The Part-Time Work Convention19 promotes access to productive, freely chosen part-time employment which honours the needs of both employers and employees, and guarantees protection for part-time employees as regards access to employment, working conditions, and social security. The Convention applies to all part-time workers - defined as employed individuals whose normal hours of work are less than those of equivalent full-time workers. The Convention attempts to ensure the equal treatment of part-time workers and equivalent full-time workers in a number of ways.21First, part-time workers are to be accorded the same protection as equivalent full-time employees with regard to: the right to organise; the right to bargain collectively; the right to act as employees' representatives; occupational safety and health; and non-discrimination in employment.

Secondly, procedures must be followed to ensure that part-time workers do not, simply because they work part-time, receive a basic wage22 which, calculated proportionately, is less than that of equivalent full-time employees. Thirdly, legislative social security schemes based on work-related engagements should be modified so that part-time workers are afforded working conditions equivalent to full-time workers.20 These working environments may be considered in the light of hours of work, contributions, or earnings. Fourth, part-time workers must also benefit from equivalent conditions with respect to maternity protection, termination of employment, paid annual leave, paid public holidays, and sick leave.23

Convention 175 likewise requires the implementation of measures to expedite access to productive and freely-chosen part-time work which meets the requirements of both employers and employees, provided that the essential protection mentioned above is guaranteed. It also requires that, where applicable, procedures must be applied to ensure that a transfer from full-time to part-time work or vice versa is on a voluntary basis in accordance with national law and practice. The Part-Time Work Recommendation 182 of 1994 encourages employers to deliberate with the representatives of the workers concerned on the institution or extension of part-time work on a comprehensive scale and subject to associated rules and procedures, and to offer information to part-time workers on their specific conditions of employment. Furthermore, the Recommendation explains the number and arrangement of hours of work, alterations to the fixed-work schedule, work beyond scheduled hours, and leave, as well as part-time worker training, career prospects, and job-related flexibility.

The ILO has also introduced other standards of specific interest to workers in non-standard forms of employment.24 Some additional ILO Conventions relevant to non-standard employment are, for example, the Employment Policy Convention25 which commits states to adopting policies, "to promote full, productive, and freely chosen employment".26 In this respect, the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR) talks of, "measures implemented in consultation with the social partners to reduce labour market dualism".27Moreover, the Labour Administration Convention28 requests states to broaden the tasks of labour administration to workers not currenty considered employed - a concern also recently addressed by the CEACR.29 Also pertinent is the Labour Inspection Convention30 on the need to uphold a system of labour inspection for workplaces, and its 1995 Protocol.

ILO standards have affected regional and national protocols on temporary work, temporary agency work, ambiguous and concealed employment relationships, and part-time work. Nonetheless, national regulations differ significantly, reflecting the specificities of the country, including the different legal systems and the different levels of economic development.

2 2 The decent work agenda and non-standard employment

It is difficult to discuss the role and application of ILO standards to nonstandard workers in southern Africa without investigating what constitutes decent work.

Decent work has been described as:

"Jobs of acceptable quality (constructive, profitable, and gainful work) both within the formal and the informal sectors; decent remuneration (to fulfil basic economic and family needs); fair working conditions; fair and equal treatment at work (no discrimination); safe working conditions; protection against unemployment; access to salaried jobs or self-employment promoting entrepreneurship and supporting small business by providing access to credit, premises, management training, business advisory services, and so on; training and development opportunities; and job creation".31

The main objective under the decent work agenda is, "not just the creation of jobs, but the creation of jobs of acceptable quality".32 Numerous aspects need to be addressed if the standard of prevailing employment and current jobs in southern Africa is to become satisfactory.

In February 2015, the ILO held a Tripartite Meeting of Experts on NonStandard Forms of Employment which hosted experts selected after consultation with governments, the Employers' Group, and the Workers' Group of the Governing Body to debate the obstacles to the decent work agenda that non-standard forms of employment may present. The meeting mandated member states, employers' organisations, and workers' organisations to develop policy resolutions to address decent work deficits related to non-standard forms of employment, so that all workers -regardless of their employment arrangement - could profit from decent work. Specifically, governments and the social partners were entreated to collaborate to implement measures to address unsatisfactory working conditions, to support effective labour market changes, to promote equality and non-discrimination, to ensure sufficient social security cover for all, to promote safe and healthy workplaces, to ensure freedom of association and collective bargaining rights, to improve labour review, and to address highly uncertain forms of employment that do not respect essential rights at work.33

2 3 Non-standard employment relations and the ramifications for the decent work agenda in Southern African states

Southern African states face numerous common obstacles in their globalised economies. They share similar attributes in their labour markets and encounter numerous problems in their relations with the international trade systems and financial organisations. Unemployment is a common denominator, as are the high rates of poverty. Southern African states have the same challenges of informal versus formal sector development, and share the same concerns and hurdles, including skills development, flexibility, and the restructuring of work.

In developing states such as those in southern Africa, which are afflicted by development hardships with a saturated labour market, the efforts of most employers to reduce labour costs have resulted in the proliferation of nonstandard employment relations, such as temporary work, fixed-term work, and part-time work, although workers in these groups have the skills required to be employed on a permanent basis. This phenomenon has varied implications for decent work.34

However, to implement the decent work agenda the first goal is the creation of employment opportunities. This goal states that the economy should create opportunities for investment, entrepreneurship, skills advancement, job creation, and sustainable livelihoods. Certain scholars argue that the obstacle to employment opportunities emerges from the variety of employment types created by global production systems.35 For employment to be decent, it should be indefinite, continuous, and secure so as to guarantee constant earnings for an employee. Furthermore, even within a single enterprise there may be employment that is flexible, insecure, and informal. Within the context of the various SADC states and their economic circumstances, the SADC economies as currently structured and managed, lack the capacity to create employment for their citizens.

The principal result of this is that people desperately seeking a means of survival will accept any form of employment they can find. Against this backdrop, virtually all employers take advantage of these desperate circumstances and exploit people who are in non-standard employment.36 If SADC governments make little effort to create employment or an enabling environment for people to create their own jobs, non-standard employment relations will continue to proliferate, to the delight of employers who are motivated by profit. As a result, the decent work agenda championed by the ILO will simply remain an illusion in the context of non-standard employment relations in the SADC sub-region.

Today, it is generally acknowledged that the decline in standard employment has gradually eroded labour protection. Non-standard workers become "invisible for recruitment into trade unions or for the protection through law enforcement"37 - despite certain non-standard employment relationships being perceived as falling within the safety net of labour law:

"There is a growing body of international evidence that some of the changes, notably the growth of precarious or insecure employment, have profound implications for worker attitudes and commitment as well as minimum labour standards and working conditions, especially the health, safety and well-being of workers. In particular, the growth of elaborate supply chains and flexible arrangements (along with changes to regulatory regimes) has been linked to the emergence or expansion of low-wage sectors/working poor (with substantial hidden costs to the community) and more intensive work regimes."38

The second goal of the decent work agenda aims to advance recognition and respect for worker rights in the workplace. All employees, and particularly vulnerable or poor workers, need a voice, representation, participation, and laws that promote their interests and address their concerns. The issue of workplace rights arises from the difficulty of organising and representing these workers. In the absence of collective power to bargain with employers, employees are not able to access or secure other rights. In most SADC member states, non-standard workers are denied several rights. The capacity of labour law organisations in southern Africa to accomplish the tasks consigned to them by the industrial relations system is limited. Despite formal acknowledgement of the right to freedom of association in SADC member states, trade unions in some countries continue to be subjected to substantial government intrusion,39 either by law or by more informal means. Finally, even where workers are formally covered by labour laws and institutional measures for review and enforcement are in place, a lack of qualified employees, resources, and organisational capacity, as well as fraud, limit the degree to which workers are in fact protected.40

Some southern African states do not have labour laws which allow nonstandard workers to join a trade union, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.41 Even when such legislation exists, enforcement remains a problem. When workers are denied the right to join trade unions in their workplace many of their other rights may also be denied. In such circumstances, the employers dictate the terms and conditions of work with little place for resistance from the workers. Further, because non-standard workers cannot unionise, they can also not bargain collectively with their employers, especially concerning remuneration, basic conditions of work, health and safety measures, and other related issues. In short, any employment relationship that does not allow for unionisation and the participation of workers in making choices that affect their work and advance their rights in the workplace, is contrary to the decent work agenda.

The third goal of the decent work agenda focuses on expanding social protection. This goal seeks to stimulate both inclusion and productivity by allowing for a situation where women and men benefit alike from working conditions that are safe, allow sufficient free time and recreation, take family and social values into consideration, afford sufficient reimbursement in case of lost or reduced income, and allow access to suitable healthcare. Barrientos argues that because many flexible and informal workers do not have access to a contract of employment and legal employment benefits, they are often deprived of access to other safeguards and social support from the state.42 In the South African context, non-standard workers lack basic social protection. For example, they are not included in their employers' pension schemes, nor can they claim unemployment benefits from the state, even though the state can afford to pay these. This leaves numerous workers very vulnerable to economic setbacks, both in their places of work and in society at large. This state of affairs can hardly be seen to advance the decent work agenda.

The fourth goal is advancing social dialogue. This goal is based on the assumption that the participation of strong and independent workers' and employers' organisations is crucial to improving productivity, circumventing disputes at work, and building interconnected societies. According to Barrientos, "the social dialogue challenge arises from the lack of effective voice or independent representation of such workers in a process of dialogue with employers, government or other stakeholders".43 Given the prevalence of non-standard employment in southern African states, these workers are deprived of a strong voice both within and outside the workplace due largely to their inability to unionise. The chances of their participating in meaningful social discourse with their employers and other participants are therefore slim, at best.

When employers abuse their workers based on the workers' lack of choice, the performance and loyalty of such workers to their work organisation and their work is questionable. This has grave consequences for productivity in both the workplace and in society.

In conclusion, decent work, as espoused by the ILO may be idealistic, but it is also definitely not a reality for most non-standard workers. In a country like South Africa with a saturated labour market and a capitalist social formation driven by the profit motive, employers, both local and foreign, will inevitably take advantage making the ideal of decent work very difficult to realise.

Non-standard employment is a global issue which, in some states, is driven by choice and not by a need to survive. In most southern African states, however, it is a matter of survival not choice. But decent work is arguably a journey rather than a destination; it is a benchmark that each state seeks to achieve. However, if decent work is to become a reality in the SADC states, the labour legislation and the practice of industrial relations must be reviewed to protect non-standard workers from unscrupulous employers who contravene the principles of labour law for personal gain.

Non-standard employment relations have become common in most employment settings in the SADC. Nonetheless, the impact of this form of employment relations on the ILO's decent work agenda has hardly been examined by industrial and social scientists. This article investigates nonstandard work within the context of flexibility and the restructuring of work, limited contracts, and outsourced employment. It argues that this type of employment relationship has been exacerbated by the increasing prevalence of unemployment, poverty, and inequality within the region. The article further argues that most employment enterprises in the SADC are using non-standard employment to reduce labour costs and increase profits in accordance with the dictates of the free market economy but to the detriment of temporary workers. The article contends that non-standard work leads to worrying contraventions of the decent work agenda in the SADC region.

2 4 Non-standard employment and labour migration in the SADC

Another aspect that presents a challenge to the capacity of labour law to regulate non-standard employment in southern Africa is extensive labour migration. The late nineteenth century saw a huge number of migrant workers in some economic sectors in South Africa - particularly in the mining and commercial agriculture sectors. Workers came from Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Swaziland.

To some degree, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania have also traditionally attracted labour migrants from nearby states. South Africa, however, remains the SADC's most powerful and diverse economy and continues to attract the main volume of both formal and informal migrant labourers.

Since 1990, the number of labour migrants relocating to South Africa from adjacent states has increased dramatically. There are several explanations for this, including growing unemployment in the transfer states and decreasing government contributions to social services.44 Currently, the main reasons for migration include the huge differences between SADC member states in terms of income, standards of living, levels of unemployment, and political instability.45 The effects of migration within the SADC are felt in numerous ways. One effect is that many households and communities in the region depend on the earnings of family members who have migrated to find employment;46 another is that governments have crafted legal and institutional frameworks to ensure that migrants do not settle in the receiving states.47

As observed by Mpedi and Smit, migrants may be divided into two main groups: documented migrants (permanent residents, temporary residents, refugees, and asylum-seekers); and undocumented migrants.48

Documented migrants are those who enter the state lawfully and have the host state's official authorisation to work within its territory. Consent to work is granted on the basis of an employment proposal from an employer who must justify the need to employ a migrant on the basis of his or her knowledge, abilities, skill, and proficiency in a specific profession. Because host states closely scrutinise applications for permission to allow migrants to work, applications are made only by establishments that are lawfully registered and comply (at least on the face of it) with the legislation regulating employment relations. Therefore, it is likely that most documented migrant workers work under favourable conditions similar to those of their indigenous colleagues. They have greater bargaining power and may rely on the protection afforded by labour legislation. This notwithstanding, apart from workers who have permanent resident status, migrant workers cannot access state social security protection, such as disability and unemployment insurance benefits.49

Migration within the region is problematic as it challenges the ability of national labour legislative frameworks to protect undocumented migrant workers who constitute the bulk of the migrant labour force. The latter are workers who enter and work in the state illegally, or who enter legally (on a premise other than work) and remain in the host state and work without permission. They generally lack the education or skills that would justify the issuing of a work permit. They choose to work in jobs where they can escape the attention of the public authorities and, consequently, have fewer choices available to them.50 They are thus susceptible to exploitation and abuse, and will accept work where the circumstances and conditions are substandard, the wages low, and where there is little or no job security.51 In addition, undocumented migrants are always vulnerable to substandard living and working conditions, live in fear of being deported, and are generally excluded from the social protection provided by the state.52

There is a clear link between non-standard employment and vulnerable workers. The problems facing non-standard work are worsened by the concentration of vulnerable workers in many of these jobs, including migrants, the youth, the elderly, and women. Migrants frequently work in the agricultural harvesting and construction labour forces, and perform undeclared work in many states. The youth and undocumented immigrants are particularly at peril because of their economic dependence, the absence of assistance, and their fear of lodging complaints with the regulatory authorities.53 Migrants generally engage in work that is not only hazardous, but also in sectors in which non-standard employment arrangements are commonplace.54 Many studies have failed fully to examine these correlations, a notable exception being the study on hotel housekeepers.55

Because of their precarious position, migrants cannot benefit from the protection afforded by labour laws. The SADC has acknowledged the need to work towards enabling the movement of citizens between member states and the steady harmonisation of migration policies.56 However, there has to date been little progress with regional efforts to regulate labour migration and the SADC region still has no coherent migration policy. Many migrant workers have no form of social protection while working in host states.57Migrant workers, particularly those who are undocumented, thus find themselves in conditions akin to non-standard employment. Olivier is of the view that, notwithstanding the existence of AU instruments that regulate and protect migrants in general, "the adoption, implementation and monitoring of international and regional standards ... appear to be problematic".58

2 5 A note on novel categories of employment in southern Africa

Non-standard employment is closely linked to the informal economy, but remains distinct from this category of worker. The term "informal economy" refers to those sectors in the economy where employ5m9 ent is unregulated and can be variously described. In the words of Smit,59 governments often view informality as an indispensable lifeline for the vulnerable and as a sign of economic vitality. However, informality comes with huge socio-economic costs. The majority of non-standard workers in developing states, and in particular in the SADC states, are not working informally by choice. This type of employment is often associated with uncertain working conditions and increasing employment insecurity.

In addition, the focus of labour law, as it has been advanced in the industrialised world, has been on the formal employment sector, and to a large extent, this is also true of southern African labour laws which have been "borrowed and bent" (Thompson) or "transplanted" (Kahn-Freund) from overseas.60 Therefore, most of the employed population of southern Africa working in the informal sector and/or in agriculture, do not benefit from labour law as traditionally conceived. A further concern is that the formal sector of the workforce is in a near-constant state of flux, with a significant growth in casual workers, home-workers, and other forms of non-standard employment.61

Across the region, between 10 and 20 per cent of the economically active population is engaged in the informal sector of the labour market, and a significant minority work in farming, generally in subsistence agriculture.62Consequently, the majority of the economically active population in Southern Africa work in the informal sector of the economy. Unsurprisingly, in many SADC countries, governments vigorously promote the informal sector as a means of economic growth and development because it solves joblessness and offers goods at competitive prices to those on very low wages.63According to Benjamin, in September 2005, employment in the South African informal sector represented 22.8 per cent of total employment. This figure increases to 29.8 per cent if domestic workers are included.64

Many states are well aware that the informal sector is a growing rather than a passing phenomenon, and that the extension of social protection is of crucial importance. Attempts have therefore been made to extend protection through legislation, for example, the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act 33 of 2008 in India; the Social Security Bill, 2005 in Tanzania; and the Social Security Act 34 of 1994 in Namibia.

2.6 Unemployment, income inequality, and regional labour standards

The application of ILO standards to non-standard workers and the creation of decent work, are paramount in the southern Africa region. However, unemployment, poverty, and inequality remain serious challenges confronting the region.

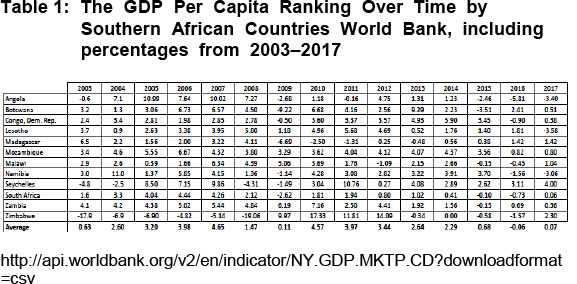

Joblessness and disparities in income are prevalent in southern Africa due to the low rate of economic growth in the region, which was reported as averaging 0.07 per cent in 2017. The growth rates in individual states vary. For instance, in 2017, Seychelles and Zimbabwe recorded an average of 4 per cent and 2.30 per cent respectively which was the highest levels of economic progression in the region. This position was formerly occupied by Namibia, Angola, and Mozambique, with growth rates of 11 per cent, 7.1 per cent, and 4.6 per cent respectively in 2004.65 The region's unemployment rate is estimated at approximately 30-40 per cent. In South Africa, this is due, in part, to the steadily increasing demand for skilled labour. On average, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has increased by three per cent per year in the SADC over the last decade. The differences in economic growth are considerable. While Angola has experienced a GDP growth per capita of more than seven per cent annually over the last decade, the per capita income of a state such as Zimbabwe has decreased by 2.8 per cent annually over the same period.

2 7 Labour market transitions in the SADC region

A crucial obstacle to the ability of labour law to provide for decent work in southern Africa is the orthodox, but now inadequate, dependence on the standard employment relationship as the linchpin of protective labour legislation. Casualisation and externalisation have produced different types of triangular employment which present a challenge to workers' protection in southern Africa. As these phenomena change the nature of employment, numerous workers no longer enjoy the protection of labour law.66

The ILO has four strategic goals: the promotion of rights at work; employment and income opportunities; social protection and social security; and social dialogue and tripartism.67 Nevertheless, there are hurdles for nonstandard employment relationships associated with these goals that apply to the circumstances in the SADC region.

The principal goal of the ILO today is to advance opportunities for women and men to secure decent and productive enjoyment in circumstances of freedom, equity, security, and human dignity.68 This goal declares that the economy should generate opportunities for investment, entrepreneurship, skills development, employment, and sustainable decent work. However, globalisation has changed the world of work. For employment to be decent, it should be indefinite, conventional, and secure and ensure an on-going income for an employee.

Within the context of the SADC, where unemployment rates are very high and the region is struggling to create jobs, the result is that people desperately looking for employment may accept whatever comes their way. It is therefore not surprising that unscrupulous employers benefit by exploiting the circumstances of these desperate individuals who are, in the main, non-standard workers.69 The author argues that if the SADC states do not implement serious measures to create jobs and an enabling environment for entrepreneurship, non-standard employment may become the norm -and only unscrupulous employers will benefit. It is further submitted that if the SADC states fail to act, the ILO's decent work agenda will remain a paper tiger in the context of non-standard employment relationships in the SADC region.

Another crucial ILO goal is to guarantee employment rights in the workplace and promote acknowledgement of and respect for the rights of workers. It is contended that all workers, irrespective of their employment status, but especially those working under unfavourable conditions, need representation, participation, and legislation that will address their concerns. Barrientos is of the view that the obstacles with regard to employment rig70hts are associated with the difficulty of organising and representing workers.70 In the absence of the collective strength to bargain with employers, workers are not in a position to acquire other rights.

In most SADC states, workers in non-standard employment have few rights. Most labour laws were originally crafted to protect employees in standard employment relationships and not those in non-standard work, who usually are unable to join a trade union. When workers find it difficult to join trade unions in their workplace, they fail to enjoy their employment rights. In such circumstances, the employer can stipulate the terms and conditions of employment with little or no opposition from workers. In addition, due to their inability to join trade unions, non-standard workers cannot bargain collectively with their employers, especially in the areas of remuneration, hours of work, health and safety measures, and other basic conditions of employment. In short, any employment relationship that does not afford its workers the right to join a trade union or does not allow the voice of the workers to be heard in decisions that affect their employment and promote their rights in the workplace, cannot advance the ILO decent work agenda.71

The extension of social protection is a third goal of the ILO. This goal encourages inclusion and productivity by ensuring that both women and men benefit from working conditions that are safe, permit enough free time and rest, take account of family and social values, provide for sufficient compensation in situations of lost or reduced income, and allow for affordable healthcare. Barrientos72 further argues that the lack of social protection is a result of the fact that numerous workers in flexible working arrangements and informal workers do not have access to contracts of employment and employment benefits. They are thus often refused access to other types of protection and the social assistance offered by the government. In the southern African context, non-standard workers seldom have any type of social protection, either from their employers, or from the state. For instance, they are excluded from pension schemes by their employers and from unemployment benefits from the state. As far as social security is concerned, this group of workers is excluded, discriminated against, and rejected by the state. This clearly goes against the ILO's decent work agenda to which most southern African states are signatory.

The ILO's goal of promoting social dialogue advocates that the participation of strong and independent employees' and employers' organisations is crucial to increasing productivity, avoiding disputes at work, and building united societies. However, the difficulty with social dialogue is the paucity of powerful voices and the independent representation of employees in a process of dialogue with employers, the state, or other participants. In the context of the dominance of non-standard employment relationships in the southern African region, this goal is very challenging in that these workers do not have a powerful voice either within or outside of their workplaces and are more often than not unable to join trade unions. When workers are exploited by their employers on the basis of their desperation and lack of alternatives, their commitment and loyalty decreases. This has a serious effect on productivity in both the workplace and the SADC region which is currently struggling to deal with poverty, unemployment, and inequality.

Olivier summarises some of the dominant characteristics of labour law in SADC countries. First, there is a primary reliance on labour legislation borrowed from other jurisdictions, rather than on developing an autochthonous system of labour law. Second, the underlying bipartite and tripartite corporatist structures have failed to contribute to labour market regulation. Third, there is a narrow focus on labour law in the small (and shrinking) formal sector of the labour market. Fourth, the ILO has had a relatively limited impact: many countries' laws fail to meet minimum standards. Finally, there is a tendency to concentrate on the legislative, judicial, and executive functions within labour departments, particularly in relation to dispute resolution.73

3 CONCLUSION

The aim of this article has been to demonstrate policy development at the ILO and to identify the international benchmarks and regional standards relevant to the regulation and protection of non-standard workers.

There can be no social justice and workplace democracy while workers' rights remain unrecognised. The ILO's mandate is organised around four interrelated and mutually reinforcing strategic objectives aimed at realising the decent work agenda: creating jobs; guaranteeing rights at work; extending social protection; and promoting social dialogue. However, like any other organisation, the ILO has its shortcomings, which include the ineffectiveness of the international standards in a changing world of work with a proliferation of non-standard workers.

The ILO has found ways of addressing these shortcomings. With regard to the challenges facing non-standard workers, the organisation has introduced standards that address non-standard forms of employment, standards that address specific categories of non-standard employment, and standards that are of particular concern to non-standard workers.

This article has also analysed the ILO's influence on the labour law systems of southern Africa, as well as unemployment, income inequality, and regional labour standards in the context of non-standard employment and labour market transitions in the southern African region. The ILO offers technical support to more than 100 states in order to achieve these goals with the support of development partners.

Decent work as espoused by the ILO may be the ideal, but is not the reality for most workers in non-standard employment relationships. In southern African states where the labour market is saturated, employers exploit the situation and make the ideal of decent work very difficult to realise. The rise of non-standard work has been aggravated by labour migration in the region, and the article has therefore also considered whether labour law in the region is capable of protecting large numbers of labour migrants.

The regulation and protection of the rights of non-standard workers, such as the right to organise and bargain collectively, requires the state, trade unions, and employers to act on the framework provided by the ILO, democratic constitutions, and the labour legislation of the various southern African states, with a view to securing a better southern Africa. Labour law scholars and experts in southern Africa should pay greater attention to international law and jurisprudence and to foreign law, to advance the rights of non-standard workers to organise and to bargain collectively. Both legislation and jurisprudence require updating and development to meet the unique needs of southern Africa.

References

1 Fenwick, Kalula and Landau "Labour Law: A Southern African Perspective" in Tekle (ed) Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries (2007) 7. [ Links ]

2 Kalula and Fenwick note that even "before a country ratifies the ILO standard, it is likely to be subject to a range of regulatory activities by the ILO. These include negotiation and discussion between the ILO officials and representatives of countries, including ministers, responsible for labour matters, and senior officials of relevant government departments." Kalula and Fenwick Law and Labour Market in East and Southern Africa: Comparative Perspectives (2004) 193-226. This might occur, eg, within the framework of campaigns to promote the ratification of the ILO's core labour standards. This "informal" aspect of ILO regulatory activity, while well-known within certain circles, has not, as far as we know, been the subject of major academic study. For a brief consideration, see Panford African Labour Relations and Workers' Rights (1994) 130-141.

3 These are the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention 87 of 1948; the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention 98 of 1949; the Forced Labour Convention 29 of 1930; the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention 105 of 1957; the Minimum Age Convention 138 of 1951; the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention 182 of 1999; the Equal Remuneration Convention 100 of 1951; and the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention 111 of 1958. Madagascar has not ratified the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention 105 of 1957 and Namibia has not ratified the Equal Remuneration Convention 100 of 1951. See http://www.ilo.org (accessed 201911-30).

4 These are the ILO/Swiss "Project to Advance Social Partnership in Promoting Labour Peace in Southern Africa", and the ILO/USDOL Project 011 "Strengthening Labour Administration in Southern Africa". See ILO "Technical Co-Operation Projects: In Focus Programme on Social Dialogue, Labour Law and Labour Administration" http://www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/ifpdial/publ/index.htm (accessed 2019-09-20).

5 For further detail see http://www.ilo.org/public/english/region/afpro/mdtharare/about/index.htm (accessed 2019-10-04).

6 Fenwick, Kalula and Landau in Tekle Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries 7.

7 Communiqué of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Labour Relations Conference Johannesburg (13-15 October 1999) 1.

8 ILO Educating for Effective Dispute Resolution in Southern Africa ILO/Swiss "Project for Regional Conflict Management and Enterprise Development in Southern Africa" RAF/03/04/SWI Pretoria (2006) 2.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 ILO Dialogue Driven Performance Improvement in the Clothing and Textile Sector in South Africa ILO/Swiss "Project for Regional Conflict Management and Enterprise Development in Southern Africa" 3.

13 ILO The ILO Promoting Labour, Peace and Democracy in Southern Africa ILO/Swiss "Project to Advance Social Partnership and Promote Labour Peace in Southern Africa" RAF/99/M10/SW1 Pretoria (2006) 1.

14 Art 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Social Rights in SADC (2003).

15 ILO Non-standard Forms of Employment Report for discussion at the Meeting of Experts on Non-Standard Forms of Employment Geneva (16-19 February 2015) 32-36.

16 Termination of Employment Convention 158 of 1982.

17 ILO Recommendation 166 of 1982.

18 Art 4 of the Termination of Employment Convention 158 of 1982.

19 The Part-Time Work Convention 175 of 1994 came into force on 28 February 1998 and has 14 ratifications: Albania, Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus, Finland, Guyana, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Mauritius, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, and Sweden.

20 However, ratifying states may, after consulting the representative organisations of employers and workers concerned, exclude wholly or in part, particular categories of worker or certain establishments from its scope "when its application to them would raise particular problems of a substantial nature".

21 The term "comparable full-time worker" refers to a full-time worker who: (i) has the same type of employment relationship; (ii) is engaged in the same or a similar type of work or occupation; and (iii) is employed in the same establishment or, when there is no comparable full-time worker in that establishment, in the same enterprise or, when there is no comparable full-time worker in that enterprise, in the same branch of activity, as the part-time worker concerned.

22 Pursuant to Recommendation 182 of 1994, part-time workers should benefit on an equitable basis from financial compensation additional to basic wages, which is received by comparable full-time workers.

23 Exclusions may be introduced for part-time workers whose hours of work or earnings do not meet certain thresholds. However, these thresholds must be sufficiently low in order not to exclude an unduly large percentage of part-time workers, and should be reduced progressively.

24 With the exception of ILO standards directed at specific occupations or economic sectors, ILO standards apply, in principle, to all workers. In some instances, exceptions may be introduced for certain enterprises, sectors, or occupations, but even then member states are encouraged subsequently to extend protection to excluded groups. Some ILO standards are of particular relevance to workers in non-standard form of employment. The Maternity Protection Convention 183 of 2000 expressly provides for its application to all employed women, "including those in atypical forms of dependent work" in recognition of the significant percentage of women found in non-standard forms of employment. The Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention 156 of 1981 applies to all branches of economic activity and to all categories of worker. It concerns men and women workers whose family responsibilities restrict their opportunities to prepare for, enter, participate in, or advance in economic activity, and is therefore particularly relevant for workers who have entered nonstandard employment arrangements in order to combine work and family responsibilities. The Social Protection Floors Recommendation 202 of 2012 can be of benefit to workers in non-standard forms of employment, particularly if they are excluded from social security cover as a result of legal thresholds. Social protection floors are nationally defined sets of basic social security guarantees aimed at preventing or alleviating poverty, vulnerability, and social exclusion.

25 Employment Policy Convention 122 of 1964.

26 Ibid.

27 ILO "Direct Request (CEACR) - adopted 2013, published 103rd ILC session (2014) Employment Policy Convention, 1964 (No. 122) - Japan (Ratification: 1986) http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:13100:0::NO:13100:P13100_ COMMENT_ID,P11110_COUNTRY _ID,P11110_COUNTRY_NAME,P11110_COMMENT_YEAR:3147206,102729,Japan,2013 (accessed 2020-01-06).

28 Labour Administration Convention 150 of 1978.

29 ILO "Observation (CEACR) - adopted 2011, published 101st ILC session (2012) Labour Administration Convention, 1978 (No. 150) - Republic of Korea (Ratification: 1997)" http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:13100:0::NO:13100:P13100_COMMENT _ID,P11110_COUNTRY_ID,P11110_COUNTRY_ NAME,P11110_COMMENT_YEAR:2700228,103123,Korea,%20Republic%20of,2011 (accessed 2020-10-12).

30 Labour Inspection Convention 81 of 1947.

31 McGregor "Globalization and Decent Work (Part 1)" 2006 14(4) Quarterly Law Review for People in Business 150-154.

32 ILO Decent Work: Report of the Director-General 4.

33 For more detail see ILO "Conclusions of the Meeting of Experts on Non-Standard Forms of Employment" (17 March 2015) http://www.ilo.org/gb/GBSessions/GB323/pol/WCMS_354090/lang-en/index.htm (accessed 2020-12-06).

34 Individual Observation Concerning Labour Inspection Convention 181 of 1947, Angola.

35 Barrientos "Modernising Social Assistance" in International Association of African Researchers and Reviewers (IAARR) Proceedings World Conference on Social Protection and Inclusion: Converging Efforts from a Global Perspective (2007) 7-24.

36 Abideen and Osuji "We are Slaves in our Fatherland - A Factory Worker" 2011 30(9) The Source 20-21.

37 Cheadle, Le Roux, Thompson and Van Niekerk Current Labour Law (2004) 698.

38 Quinlan "We've Been Down This Road Before: Vulnerable Work and Occupational Health in Historical Perspective" in Sargeant and Giovanne (eds) Vulnerable Workers: Safety, Well-Being and Precarious Work (2011) 33.

39 Fenwick et al in Tekle Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries 1.

40 Fenwick et al in Tekle Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries 34.

41 Fourie "Non-Standard Workers: The South African Context, International Law and Regulation European Union" 2008 11 (4) PER/PELJ 1. [ Links ]

42 Barrientos in IAARR Proceedings World Conference on Social Protection and Inclusion: Converging Efforts from a Global Perspective 7-24.

43 Ibid.

44 ILO Labour Migration to South Africa in the 1990s ILO Southern Africa Multidisciplinary Advisory Team, Policy Paper Series No 4 Harare, Zimbabwe (February 1998).

45 Crush, Peberdy and Williams "Migration in Southern Africa" http://www.sarpn.org/za/documents/d0001680/P2030Migration_September_2005.pdf (accessed 2020-03-18).

46 ILO Labour Migration to South Africa in the 1990s; ILO Southern Africa Multidisciplinary Advisory Team, Policy Paper Series No 4 Harare, Zimbabwe (February 1998).

47 Ibid.

48 Mpedi and Smit Access to Social Services for Non-Citizens and the Portability of Social Benefits within the Southern African Development Community (2011) 3. [ Links ]

49 Olivier and Kalula "Regional Social Security" in Olivier, Smit and Kalula (eds) Social Security: A Legal Analysis (2003) 23 15.

50 ILO Decent Work and the Informal Economy International Labour Conference, 90th Session, Geneva, 2002.

51 Fenwick et al in Tekle Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries 14.

52 Dupper "Migrant Workers and the Right to Social Security: An International Perspective" 2007 Stell LR 219 223.

53 McLaurin and Liebman "Unique Agricultural Safety and Health Issues of Migrant and Immigrant Children" 2012 17(2) Journal of Agromedicine 186-196. [ Links ]

54 Rizvi Safety and Health of Migrant Workers: Understanding Global Issues and Designing a Framework Towards a Solution (2015) 5.

55 Seifert and Messing "Cleaning up after Globalisation: An Ergonomic Analysis of the Work Activity of Hotel Cleaners" 2006 38(3) Antipode 557-578. See also Sanon "Agency Hired Hotel Housekeepers" 2014 62(2) Workplace Health & Safety 86-95.

56 Draft Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons in the SADC (1998) www.sadc.int (accessed 2019-11-15).

57 Olivier and Kalula in Olivier et al Social Security: A Legal Analysis 23.

58 Olivier "Enhancing Access to South African Social Security Benefits by SADC Citizens: The Need to Improve Bilateral Arrangements within a Multilateral Framework (Part I)" 2012 2(2) SADC Law Journal 129 138. [ Links ]

59 Smit and Fourie "Perspectives on Extending Protection to Atypical Workers, including Workers in the Informal Economy in Developing Countries" 2009 3 TSAR 516-547.

60 Kahn-Freund "On Uses and Misuses of Comparative Law" 1974 37 Modern Law Review 1.

61 Kalula "Beyond Borrowing and Bending: Labour Market Regulation and Labour Law in Southern Africa" in Barnard, Deakin and Morris (eds) The Future of Labour Law: Liber Amicorum Sir Bob Hepple QC (2004) 275-287.

62 Reports vary as to whether the correct figure is ten per cent (Torres) or twenty per cent. See Harrison and Leamer "Has Globalization Eroded Labor's Share?" 1997 15 Journal of Labor Economics 20. [ Links ]

63 Freund The African Worker (1998) 133.

64 Benjamin "Informal Work and Labour Rights in South Africa" 2008 29 ILJ 1579 1583.

65 Fenwick et al in Tekle Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries 23-26.

66 Ibid.

67 See http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-ihtm (accessed 2019-0815).

68 Ibid.

69 Fourie 2008 PER/PELJ 1.

70 Barrientos in IAARR Proceedings World Conference on Social Protection and Inclusion: Converging Efforts from a Global Perspective 7-24.

71 Okafor "Sociological Investigation of the Use of Casual Workers in Selected Asian Firms in Lagos, Nigeria" 2010 8(1) Ibadan Journal of the Social Sciences 49-64.

72 Barrientos in IAARR Proceedings World Conference on Social Protection and Inclusion: Converging Efforts from a Global Perspective 7-24.

73 Olivier "Social Protection in the SADC Region: Opportunities and Challenges" 2002 18(4) International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 377. [ Links ]