Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versión impresa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.18 no.2 Centurion may./jun. 2019

SOUTH AFRICAN ORTHOPAEDIC ASSOCIATION

The South African take on the America-British-Canadian Fellowship

Held MI; Walmsley PII; Baker PIII; Ramasamy AIV; Sandiford AV; Johnson LVI; Rosenfeldt MVII

IMD, PhD FC Orth(SA); Consultant orthopaedic surgeon; Knee Unit, Groote Schuur Hospital and Orthopaedic Research Unit, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMD, FFSTEd, FRCS(Tr&Orth); Consultant orthopaedic surgeon and honorary senior lecturer; Trauma and Orthopaedic Department, Victoria Hospital, Hayfield Road, Kirkcaldy and University of St Andrews, United Kingdom

IIIMSc, MD, DipStat, FRCS(Tr&Orth); Consultant orthopaedic surgeon; South Tees Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and the University of York, United Kingdom

IVMA, PhD, FRCS(Tr&Orth); RAMC consultant orthopaedic surgeon and senior lecturer; The Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injuries Studies, Imperial College London, South Kensington, United Kingdom

VMSc, FRCS(Tr&Orth); Consultant orthopaedic surgeon; St George's University Hospital, London, United Kingdom

VIBSc, FRACS(Ortho), FAOrthA; Consultant orthopaedic surgeon; South Australia Bone Tumour Unit, Flinders University and Flinders Centre for Innovation in Cancer, Australia

VIIBHB, FRACS; Consultant orthopaedic surgeon; Unisports Sports Medicine Clinic and Counties Manukau DHB, Auckland, New Zealand

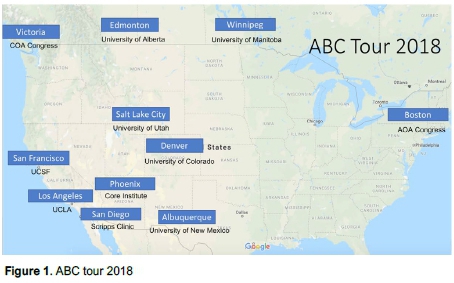

It was a great privilege to experience the American-British-Canadian (ABC) fellowship during the 2018 tour through North America (Figure 1, Table I). The following passages will introduce the fellowship and its history, and provide feedback relevant to orthopaedic practice in South Africa.

The ABC fellowship was created by Professor Harris, Chief of Orthopaedics in Toronto and President of the American Orthopedic Association who organised the first tour in 1948 (Figure 2). Its purpose was to continue the collaboration and knowledge exchange in orthopaedic surgery which emerged between the Allied Forces caring for casualties during the Second World War. Since then, a group of British surgeons visited North America on even years, and on odd years a Canadian-American group made the reverse trip. From 1982 onwards, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa each sent a fellow every two years to North America alongside four UK fellows.

And so, over the last 70 years, the ABC fellowship has supported many promising surgeons to make a significant impact on orthopaedic surgery (www.aoassn.org, link, for previous South African ABC fellows, see Table II). The most suitable meaning of 'fellowship' for the purpose of this tour was 'camaraderie, friendship, mutual support and respect'. Now, as then, the emphasis of it is to enter the international orthopaedic family, fostering networks and collaborations to create value among the fellows and for our colleagues and patients at home. It allows the exchange of new approaches, leadership styles and exploration of different health systems, but most importantly, it enables conversations around the mandate, vision, and future of our profession.

During our tour we saw that we all have similar challenges but tackle them in different ways in terms of clinical care, administration, funding and research. The US spends 17% of the GDP on health care which is not centrally funded. Strategies of US orthopaedic surgeons are based on individualism and creativity, promoting their techniques, services and outcomes to increase or defend market share and to stand out in a competitive health care system. In their hospitals, orthopaedic surgeons are seen as income generators, are given resources, posts and space, as long as this generates more productivity and income. As such, departments we visited have created biotechnology or implant design companies, massive data management hubs and hospital management consulting companies, one-stop holistic sport injury assessment and treatment centres, arthroplasty centre turned insurance company, medical tourism hotspots, and much more. Often, financial incentives are built into these systems to offset a high work load but the risk of burnout in this system is increasingly recognised and addressed. You can (and might have to) always do more!

Most of this system is mainly accessible for patients with private health care although patients with no or a lower paying health insurance are cross-subsidised, up to a certain point. What happens beyond this point is not uniformly organised or addressed. Many of the programmes we visited therefore incorporated non-for-profit organisations or projects into their departments, which attempt to look beyond short-term financial capital, including social, human and intellectual capital.

This American way of orthopaedic surgery stood in contrast to the centralisation and standardisation of the state-funded Canadian health care system. Built on egalitarian and socialistic principles it makes essential health care accessible and affordable to all. Currently Canada spends about 10% of its GDP on health care. Centralised intake clinics, standardised referral pathways, pre-operative optimisation algorithms, countrywide registries, and enforced national protocols for treatment have grown in the effort to allow equal access to high quality orthopaedic surgery. Hospitals are publicly funded and the amalgamation of hospitals has reduced competition which has increased regional and national collaborations in care, research and training. These hospitals, by law, are obliged to stay within their budget, therefore costs are cut wherever possible. Often orthopaedic departments are regarded as money spenders and are scrutinised to reduce costs by limiting procedures, implants and equipment or human resources. As a result, many trainees are unable to And posts and increasingly have to pursue double fellowships and higher research degrees to stay competitive or look for job opportunities in the US. Another drawback of this system is the increased waiting periods, namely up to two years for joint replacements. As a result, programmes have been established to increase the efficiency of doctor-patient communication, allow screening and centralised intake, which aim to decrease unnecessary care, ultimately cutting wait times. But cross-border medical tourism to the US has increased, especially for non-essential surgery and the upper class. With these vast differences there were similarities which stood out. These will be discussed in the next section and related to our practice in South Africa.

Although there are major differences in the American and Canadian system, both attempt to ensure delivery of high quality care for the populations of patients they serve, and to keep costs as constrained as possible. To achieve this, an overarching focus in both systems was to measure and analyse outcome. This was seen as key to improve access and quality of care, drive innovation, evaluate and allocate resources, and to highlight the impact and need of orthopaedic surgery. Besides this, almost all research units we visited in the US and Canada started their programme with outcome research, through which they were able to build a track record, increase funding, and assess the clinical impact of their lab-based basic science research. And so, for orthopaedic surgery in South Africa, measuring outcome might be the single most important step to adjust our practice to resource pressures and future system changes, both in the private as well as the public sector. There is much discussion on the National Health Insurance (NHI), to increase equity to health care, especially for lower-income households. Most of our health expenditure (8% of the country's GDP) is spent in the private sector in which 80% of approximately 900 of our orthopaedic surgeons work. To adjust this, the NHI plans to cap doctors' fees and link them to outcome. Without our own data we won't be able to back up our arguments in upcoming negotiations, both in the public and private sectors. One quote that came up again and again was: 'Any system will need to be paid for, either with money, waiting time or clinician hours.'

During these times, our leadership will be tested to adjust to the change of our environment.

On our tour we met incredible leaders of our profession who mainly measured their success by the progress of people they supported. To see how these departments held their junior staff in the centre of their organisation and celebrated their success was one of the most powerful memories of this trip. We often saw senior consultants and heads of departments helping out in various clinics, assisting registrars in surgery, teaching medical students, taking time to engage with sisters in the wards, visiting research support staff in their labs, and being involved in their community. This people-centred approach created an inclusive, supportive, authentic and transparent culture in their department, and the saying 'culture eats strategy for breakfast' was echoed and lived by many. But most importantly it made departments dynamic and resilient to challenges. This type of leadership and culture is also practised by many orthopaedic surgeons in South Africa and might be the greatest positive effect on the future of our profession.

This trip was an unforgettable experience, exploring the perspectives and solutions but also the countries and cultures of our orthopaedic sister associations. It brought us closer as a group of fellows and hosts, and our shared insights triggered reflections to improve our practice at home. I am humbled to have been given this great opportunity and the support from my department in Cape Town, the SAOA and our British, American and Canadian sister associations, as well as the Bone and Joint Journal. This fellowship is one of the best ways to get to know the 'behind the scenes' of orthopaedic surgery and create the future leaders of our profession through camaraderie, friendship, and mutual support.