Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versión impresa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.17 no.4 Centurion oct./dic. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2018/v17n4a1

TRAUMA

An audit of circular external fixation usage in a tertiary hospital in South Africa

Van der Walt NI; Ferreira NII

IMBChB, FC Orth(SA); Orthopaedic surgeon, Mediclinic Newcastle, c/o Hospital & Bird Street, Newcastle, 2940

IIBSc, MBChB, FC Orth(SA), MMed(Orth), PhD; Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Tygerberg Hospital, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, 7505, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Circular external fixation is a well-known treatment modality in reconstructive orthopaedic surgery and is frequently used for deformity correction, limb lengthening, limb salvage, and complex diaphyseal and periarticular fractures. The current use of this treatment modality in the South African context remains largely unknown. This retrospective review aims to describe the indications, outcomes and complications of the use of circular external fixation in a tertiary hospital in South Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed the records of 480 patients treated with circular external fixation in a specialist limb reconstruction unit. We report on patient demographics, comorbidities, indications and outcomes.

RESULTS: The final cohort consisted of 346 men and 134 women with a mean age of 35.5 years (SD 14.9, range: 5-73). Comorbidities were identified in 163 (34.0%) patients. These included diabetes in 14 (2.9%) patients and smoking in 102 (21%) patients. HIV infection was diagnosed in 120 patients (25%) with a mean CD4 count of 425 cells/mm3 (SD: 223, range: 82-1056). The mean time in external fixator was 24.6% weeks (SD: 15.3, range 4-159). The treatment objective was achieved in 441 patients (92%). The overall complication rate excluding pin-site infection was 26%. Pin-site infection occurred in 88 patients (18.3%) but had no impact on the outcome of treatment.

CONCLUSION: Circular external fixation treatment objectives can be achieved in a high percentage of patients in the context of a South African specialist reconstruction unit. This study shows favourable outcomes in deformity correction, limb lengthening, limb salvage, and complex diaphyseal and periarticular fractures. Comorbid factors, including HIV, diabetes and smoking had no effect on achieving the planned outcomes, but smoking did increase the overall time in external fixator.

Level of evidence: Level 4

Key words: circular external fixation, Ilizarov, outcome, complications

Introduction

Circular external fixation is an indispensable treatment modality in reconstructive orthopaedic surgery and is frequently used for the treatment of high grade open fractures, limb lengthening,1,2 deformity correction, limb salvage and complex diaphyseal and periarticular fractures.3-8 Owing to its minimally invasive application and three-dimensional stability, circular external fixators are increasingly being used for the management of high-energy trauma and injuries with associated soft tissue compromise.1,4,9-13,14 It is frequently utilised in peri-articular fractures of the tibia and has shown a decrease in the incidence of deep infection.4,8 The current use of this treatment modality in the South African context remains to be established.

The use of circular external fixators in South Africa has increased significantly during recent years, but the indications for their use, complications and outcomes remain to be reported. This retrospective study aims to investigate the context and use of circular external fixation in a limb reconstruction unit in South Africa. The study (retrospective cohort study) specifically aimed to provide descriptive analyses of patient biographical information, comorbidities, diagnosis and treatment outcomes.

Materials and methods

We reviewed the records of 480 consecutive patients treated with circula r external fixation in a specialist limb reconstruction unit. A retrogective review was performed on all patients who underwent treatment with circular external fixation between January 2008 and November 2015. Institutional ethics approval was obtained before commencing the study.

Ilizarov-type circular fixators were applied according to a step-wise method with the use of fluoroscopy to attain alignment. Coronal plane alignment was achieved with proximal and distal reference wires followed by sagittal plane alignment. Fixation was completed with at least two tensioned fine wires per ring.15

Hexapod external fixators were used when manual fracture reduction was not possible or where deformity correction was required. These fixators were applied using the 'rings first' method entailing the independent, orthogonal application of one ring to each bone segment. Fixation was achieved through the use of a combination of half pins and tensioned fine wires. The construct was completed with the attachment of six variable length struts. Deformity correction was planned by using post-operative radiographs, after which the correction was commenced at a rate of 1 mm per day.

Open fractures were managed according to a standardised treatment protocol that included emergency department antibiotic administration, wound irrigation and splinting followed by urgent surgical debridement. Fractures were temporarily stabilised with monolateral external fixator stabilisation and injuries were classified according to the Gustilo and Anderson system. A 48-hour wound inspection and closure was performed by either delayed primary closure, soft tissue flap or split skin graft. Conversion to circular external fixation was performed once the soft tissues had healed sufficiently.

Gunshot injuries were classified according to the Long classification.16 Low-energy injuries were treated by local wound debridement and closure in the emergency department followed by fixation, mostly but not always by circular external fixator, on an elective theatre list. High-energy injuries were treated as open fractures with emergency surgical debridement and fixation in theatre.

Periarticular fractures were classified according to the Ruedi-Algower classification for pilon fractures and Schatzker classification17-19 for tibial plateau fractures. Knee fracture dislocations were classified according to the Hohl and Moore system.20-22 These cases were initially immobilised in either a plaster of Paris backslab or joint spanning monolateral external fixation in open fractures. Following a CTbcan to plan definitive fixation, an Iliza rov type circular external fixator was applied.

In caaaa with segmental bone loss of 4 cm or more a five-ring bon e t ransport frame was constructed. A metaphyseal osteotomy was followed by a latency period of between 7 and 10 days after which bone transport at a rate of 1 mm per day was performed. A formal docking procedure was performed for all cases of bone transport. Where segmental bone loss of less than 4 cm was observed, acute or gradual limb shortening was followed by restoration of limb length through a distant metaphyseal osteotomy and lengthening.

Functional rehabilitation comprised early joint mobilisation and weight bea ring which was followed by normalisation of gait and functional use training. This a/as done witt the assistance of a physiotherapist. Pin-site care was done according to a standardised protocol.23-25 This included a meticulous intra-operative insertion technique and a post-operative pin-care regimen that includes pin-site cleaning with chlorhexidine in alcohol twice a day.

Patients were followed up every two weeks until a good compliance torehabilitation was established. Thereafter patients were seen at four-weekly intervals. Circular fixators were removed when tricorticalconsolidation was evident on outpatient radiographs.

Non-union was defined as no clinical or radiological evidence of union after a minimum of six months since the onset of initial treatment and union deemed unlikely without further intervention. We recorded non-unions as mobile or stiff, and whether they were atrophic, oligotrophic or hypertrophic.26-30 Chronic osteomyelitis was defined as osteomyelitis with radiological evidence of sequestra, involucrum, radiolucency, and clinical evidence of infection in the form of a sinus or fistula.31 Deep infection was defined as an infection involving any tissue (including bone) deep to the dermis at any point in time. The treatment objective was defined as achieving the pre-operative planned outcome. This included union as defined by clinical and radiological evidence of consolidation and adequate alignment, defined as less than 5 degrees angulation in any plane. In order to qualify as having achieved the treatment objective, limbs also had to have a functional range of motion and patients had to have functional use of the treated limb. Treatment failure was defined as any instance where the desired outcome formulated at the start of treatment was not achieved. Refer to Figures 1, 2 and 3 for more detail.

Analysis and interpretation

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Continuous variables were reported using cross tabulations, and summarised using mean and standard deviation. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were added where the standard deviationwas large and/or wh ere there was evidence of asymmetry or skewing. Differences in means by dichotomous classification were assessed using the student's t-test while difference in rank for skewed variables were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Association between these categorical variables were assessed using Pearson's chi-squared or Fisher's exact test if the expected count was less than 5.

Results

The records of 485 patients were reviewed. Five patients were excluded from the study - all of whom died from causes unrelated to their circularfixator management. Thefinal cohort consisted of 480 patients comprising 346 men (72.1%) and 134 women (27.9%). The mean age was 3 5.5years (standard deviation [SD]: 14.9, range 5-73). The age distribution over the two sexes is shown in Figure 1.

Indications for circular fixation included high grade open fractures in 144 (30%) patients, complex closed fractures in 122 (25.4%) patients, and gunshot injuries in 12 (2.5%) patients. Circular fixators were also used for the management of 102 (21.3%) non-unions and 34 (7.1%) chronic osteomyelitis cases. Sixty patients had deformit2 corrections and included 28 developmental deformities, 27 malunions and five congenital deformities. Two (0.4%) patients had circular fixator stabilisation following tumour resections.

Comorbidities were identified in 163 (34%) patients of which some of t0e patients had more than one comorbidity. These included 14 (2.9%) diabetics, 101 (21%) active smokers, 120 (25%) patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Eighty (667%) of the HIV-positive patients were on highly active anti-retroviral treatment (HAART).

Among the HIV-infected patients, the mean CD4 count was 425 cells/mm3, with an IQR of between 264 and 528 (full range 82 to 10 5(5). The distribution of CD4 counts is presented in Figure 2.

The mean treatment time ('time in frame') was 24.6 weeks (SD: 15.3, range 4-159), while the mean follow-up period was 12 months (SD: 9.6, ran ge 1-65). The distribution of time in frame and time of follow-up are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

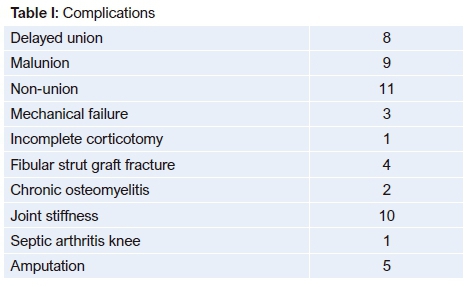

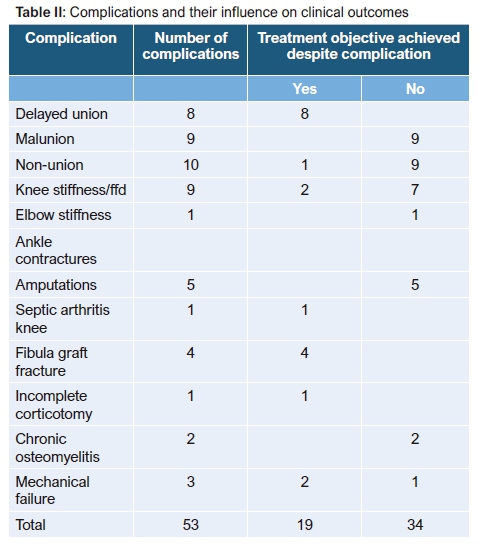

The treatment objective was achieved in 441 out of 480 (91.9%) patients. The reasons of failure to achieve the treatment objective in 39 patients included: amputation in five patients, chronic osteomyelitis in three patients, recurrence of deformity in one patient, joint stiffness in ten patients, malunion in ten patients and non-union in ten patients. Some patients did achtere the treatment objective despite developing a complication. In these cases,thecomplications were of a minor severity and did not impact treatment outcome. Refer to Tables I and II for details.

Open fractures (144)

One hundred and forty-four patients (30%) were treated for open fractures. These included two (1.4%) Gustilo-Anderson II, 75 (52%) Gustilo-Anderson IIIA and 67 (47%) Gustilo-Anderson IIIB fractures. The average time in external fixator was 24.97 weeks (SD: 10.73, range 4-69) for patients with Gustilo-Anderson IIIA injuries and 27.3 weeks (SD: 14.84, range 6-80) for patients with IIIB injuries (p=0.648).

The treatment objective was achieved in 131 out of 144 (91%) patients. Four patients who sustained Gustilo-Anderson IIIA injuries and nine patients who sustained Gustilo-Anderson IIIB injuries did not achieve treatment objective (p=0.09). There was no statistical significant difference in outcome of Gustilo-Anderson IIIA and IIIB injuries.

Failure to achieve treatment objective was due to non-union in four patients, joint stiffness in three patients, chronic osteomyelitis in two patients, malunion in two patients and two patients that required amputation. Both patients who required amputation sustained Gustilo-Anderson IIIB tibial diaphysis injuries.

Non-unions (102)

One hundred and two (21.3%) non-unions were managed with circular external fixation. Stiff hypertrophic non-unions were observed in 63 patients (61.8%) while 49 patients (38.2%) had mobile oligotrophic or atrophic non-unions. The majority of patients (92 out of 102) (90.1%) had non-unions following tibial shaft fractures; the remainder included five humeral shaft nonunions, four femoral shaft non-unions and one non-union of an ankle fracture. The average time in circular fixator was 24.4 weeks (SD: 15.2, range 6-114). The treatment objective was achieved in 94 (92.2%) cases. Six cases failed to unite, and another patient requested an amputation. One mechanical failure of the external fixator resulted in a malaligned union.

Chronic osteomyelitis (34)

Thirty-four patients (7.1%) were treated for Cierny and Mader stage IV chronic osteomyelitis.32,33 The average time in external fixator was 46.4 weeks (SD: 30.5, range 13-159).

Treatment objective was achieved in 28 (82%) patients. The six cases where the treatment objective was not achieved included two amputations, one malunion, one non-union and one fixed flexion deformity (ffd) of the knee. Only one case had residual chronic osteomyelitis following treatment, resulting in a cure rate of 33 out of 34 patients (97%). Additional complications included one delayed union and one incomplete osteotomy.

Deformity corrections (60)

Sixty patients (12.5%) underwent deformity correction with the use of circular external fixation. These included 27 patients (5.6%) that had deformity correction for malunited fractures, 28 patients (46.6%) for developmental deformities and five for congenital deformities. The malunited fractures included 19 tibial shaft malunions, five femur shaft malunions, one tibial pilon, one ankle and one forearm malunion. The average time in external fixation for malunion correction was 20.8 weeks (SD: 8.8, range 9-39). The treatment objective was achieved in all patients who were treated for fracture malunion. Apart from pin-site infection there were no other complications.

Twenty-eight patients (5.8%) were treated for developmental deformities. This included 17 tibias, seven femurs, one foot, one forearm and two wrists deformities. The average time in external fixator was 16 weeks (SD: 5.3; range 7-25). The treatment objective was achieved in 27 patients (96.4%). One patient developed recurrence of deformity following gradual correction of a wrist contracture. One patient developed septic arthritis of his knee during the correction of a distal femoral deformity.

Five patients (1.0%) had gradual correction for congenital deformities. These included two feet, two tibias and one femur. Average time in frame was 14.4 weeks (SD: 6, range 5-21). There were no complications, and the treatment objective was achieved in all patients (100%) with congenital deformities.

Gunshot wounds (12)

Twelve patients underwent circular fixator treatment for gunshot injuries. These included six Long II, three Long III and three Long IV gunshot wounds. Average time in frame was 24.7 weeks (SD: 10.78; range 17-51). The treatment objective was achieved in nine (75%) cases. Two cases complicated with knee stiffness; one occurred following a trans-articular knee gunshot while the second patient sustained a transfemoral gunshot. One case of malunion occurred in a Long type II tibial fracture. All other cases achieved the treatment goal without any complications.

Tumour resections (2)

Two patients had circular external fixators applied following tumour resections. One was used in a tibia and one in a femur. In both cases the treatment objective was achieved. In the tibial resection, the treatment was complicated by a non-vascularised fibular strut graft fracture that was successfully treated with a second circular external fixator by stabilisation and compression of the fracture.

Complications

Complications occurred in 53 patients (11.0 %) and included delayed union in eight patients (1.67%), non-union in 11 (2.3%) patients, malunion in nine (1.9%) patients and pin-site infection in 88 (18%) patients. Joint stiffness or contractures occurred in ten (2%), fibular strut graft fracture occurred in four (0.8%), and incomplete corticotomy occurred in one (0.2%). Chronic osteomyelitis occurred in two (0.4%) patients, while mechanical failure of the circular fixator occurred in three (0.6%) patients.

Amputations were performed for five patients (1%). Two were the result of high-grade open fractures of the tibia. Two amputations were performed following failed treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. The fifth amputation was performed for a patient with an atrophic tibial non-union who was not prepared to continue the planned treatment. Three of the five patients (60%) requiring amputation were smokers. This is a marginally statistically significant finding (p=0.065) with an odds ratio of 5.8 (95% CI: 0.95-35). The current study is insufficiently powered to draw strong conclusions regarding the risk of amputation in smokers.

Joint stiffness was observed in ten (2%) cases. The knee joint was affected in nine cases and the elbow in one. Five of these were secondary to a tibial plateau fracture or other knee injury. In the stiff knee group, 97 plateau fractures or other knee injuries were treated resulting in a five per cent incidence of joint stiffness in this group of patients. The relative risk for developing a knee contracture following a knee injury was only 2.4 (p=0.1); the absolute risk increase was 3% above the risk of developing knee stiffness for other lower limb circular fixation. This study thus found no causal relationship between knee injury and joint stiffness.

Pin-site infection occurred in 88 patients (18.3%). The majority (90%) of these infections were minor according to the Checketts and Otterburn classification and responded to local pin-site care and oral antibiotics. See Table III for details. No frames had to be abandoned due to pin-site infection, which means that risk of pinsite infection should not bias the decision to apply a fixator or not.

Comorbidities

A summary of the influence of comorbidity on complications is given in Table IV.

Smokers

One hundred and two patients (21%) were active smokers. The treatment objective was achieved in 87% of smokers compared to 93% of non-smokers. The average time in external fixator was 28.7 weeks (SD: 16.9, range 11-114) for smokers and 23.4 weeks (SD: 14.7, range 4-159) for non-smokers (p=0.0019). We observed an increased risk of developing a non-union in smokers (p=0.006). Pin-site infection was observed in 17.6% of smokers compared to 18.7% in non-smokers (p=0.689) (see Figure 5 and Table V).

HIV

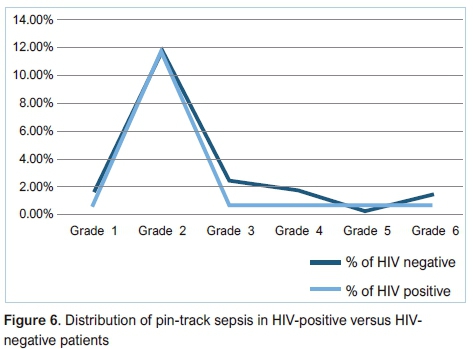

HIV infection was diagnosed in 120 patients (25%). Our data failed to show any significant difference in incidence of pin-site infection (p=0.414), non-union (p=0.367), delayed union (p=1.00), chronic osteomyelitis (p=1.00), risk for amputation (p=0.338) or risk for treatment failure (p=0.630) between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. There was no statistically significant difference in achieving the planned outcome in HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals (p=0.232). See Figure 6 and Table VI.

Note that time in frame for smokers is significantly increased (p=0.0019) (see Table VII).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to review the indications, complications and outcomes of circular external fixation in a limb reconstruction unit. Our results are comparable to results quoted in international literature.32-39

The relatively low rate of failed limb salvage (our amputation rate was 1%) observed in our study points to the fact that ring fixation is a safe and effective treatment modality. It may also indicate a relatively conservative approach to patient selection for limb salvage and that our unit could consider a more aggressive approach in attempting limb salvage instead of early amputation. The LEAP study reported an incidence of failed limb salvage of 3.6% requiring late amputation.40 It has clearly been shown that the long-term costs of an amputation exceed that of complex reconstruction.41 In a resource-poor setting like South Africa, limb salvage should therefore be considered more frequently.

The rate of chronic osteomyelitis following Gustilo-Anderson IIIB fractures in our study was 1.4%. This compares favourably to developed world rates despite the delayed primary treatment and strained plastic surgery resources. This finding is one of the most important findings of this study and strenghtens the argument for the use of circular external fixation in open fractures. The LEAP group reports 8.6% of chronic osteomyelitis in their limb salvage group.31,38,40,42

Our data failed to show any statistically significant complications in patients infected with HIV. The final outcomes were also not affected by HIV infection. It should, however, be noted that our study was insufficiently powered to perform subgroup analysis for patients with CD4 counts below 200 cells/mm3. Our study thus predicts HIV not to be a contributor to complications in patients with a relatively high CD4 count; our IQR was between 264 cells/mm3 and 528 cells/mm3. Ferreira et al. reported that HIV had no effect on the incidence or severity of pin-site infection.43 In a literature review by Karipersad in 2009, HIV had no effect on outcomes on fracture treatment.44 Our current study supports both these findings.

Smoking remains a concern when embarking on complex limb reconstruction surgery. Our study found that smoking increased the time in external fixator (p=0.0019) and also increased the risk of developing a non-union by a factor of 4.5 (p=0.006). The LEAP study found that current smokers were 37% less likely to achieve union and 3.7 times more likely to develop osteomyelitis. In contrast to the LEAP study we found no increased risk for development of osteomyelitis in smokers.45 Schmitz et al. reported time to union in closed and grade I open tibial fractures of smokers and non-smokers as 38.4 weeks and 19.4 weeks respectively.46 Our study demonstrated similar results and found time to union of 28.7 weeks for smokers and 23.4 for non smokers. (p=0.0019) Patel et al. conducted a systematic review on the effect of smoking on bone healing, and had similar findings to our study; of all the complications that were assessed, the most consistent finding was that smoking delayed bone healing.47 Patel et al. failed to identify an increased rate of non-union in the studies that they reviewed. The definition of non-union, however, varied widely among the studies making interpretation of the finding difficult. Our study found a 3.75 times higher likelihood of developing a grade 6 pin-site infection when smoking. This is, however, only an absolute risk increase of 2.18% for the development of a grade 6 pin-site infection in a smoker and only a statistical trend, which is not statistically significant. The LEAP study similarly did not identify smoking as a risk factor for pin-site infection.45

We failed to identify any correlation between diabetes and any of the outcomes measures used. The study, however, only included 14 (2.9%) patients with diabetes. This small number means that the present study is insufficiently powered to make any inferences regarding the use of circular fixators in diabetic patients. In contrast to our study, Wukich et al. found a seven-fold risk for wire complications in patients with diabetes.48

Pin-site infection was the most common complication encountered with 88 out of 480 patients (18.3%) developing some form of pin-site infection. No frames had to be abandoned due to pin-site infection, nor did pin-site infection increase the average time in frame, complication rate or final outcome. None of the comorbidities studied had a clinically significant effect on risk of developing pin-site infection. The reported incidence of pin-site infection ranges from 0-100%.49 Parameswaran et al., for example, reported an incidence of 3.6% of pin-site infection in their group of 77 patients.50 A review by Iobst et al. showed the cumulative risk of pin-site infection was 29.5%.49 Our study group has a rate of pin-site infection of 18.3%. The majority (90%) of these were minor infections that were easily treated with oral antibiotics and local pin-site care. The development of pin-site infection did not impact on the final outcome. According to our data the potential risk of developing pin-site infection should therefore not deter from the use of circular external fixation in appropriate circumstances.

There are several limitations to this study including its retrospective observational design, single-centre cohort and lack of a control group. This study was also performed in a speciallist limb reconstruction unit with dedicated treatment protocols.

Conclusion

Circular external fixation shows good outcomes in the context of the South African specialist limb reconstruction unit. This study shows favourable outcomes with an overall low rate of complications in deformity correction, limb lengthening, limb salvage, and complex diaphyseal and periarticular fractures. Comorbid factors, including HIV, diabetes and smoking, had no statistically significant effect on final outcomes. Of all the comorbidities and risk factors recorded, the only clinically significant finding was that smoking increased the time in the external fixator.

Ethics statement

Institutional ethics approval was obtained before commencing the study (BE290/13).

References

1. Watson MA, Mathias KJ, Maffulli N. External ring fixators: an overview. Proc Instn Mech Engrs 2000;214:459-70. [ Links ]

2. Khaleel A, Pool RD. Recent advances in bone transport. Curr Orthop 2001;15:229-37. [ Links ]

3. Papagelopoulos PJ, Partsinevelos AA, Themistocleous GS, Mavrogenis AF, Korres DS, Soucacos PN. Complications after tibial plateau fracture surgery. Injury 2006;37:475-84. [ Links ]

4. Ferreira N, Senoge ME. Functional outcome of bicondylar tibial plateau fractures treated with the Ilizarov circular external fixator. SA Orthop J 2011;10(3):80-84. [ Links ]

5. Young MJ, Barrack RL. Complications of internal fixation of tibial plateau fractures. Orthop Rev 1994;23:149-54. [ Links ]

6. Jiang R, Luo C, Wang M, Yang T, Zeng B. A comparative study of Less Invasive Stabilization System (LISS) fixation and two-incision double plating for the treatment of bicondylar tibial plateau fractures. Knee 2008;8:139-43. [ Links ]

7. Ali AM, Yang L, Hashmi M, Saleh M. Bicondylar tibial plateau fractures managed with the Sheffield hybrid fixator. Biomechanical study and operative technique. Injury 2001;32:S-D-86-S-D-91 [ Links ]

8. Watson JT, Ripple S, Hoshaw SJ, Fyhrie D. Hybrid external fixation for tibial plateau fractures: Clinical and biomechanical correlation. Orthop Clin North Am 2002;33:199-209. [ Links ]

9. Bronson DG, Samchukov ML, Birch JG, Browne RH, Ashman RB. Stability of external circular fixation: a multi-variable biomechanical analysis. Clin Biomech 1998;13:441-48. [ Links ]

10. Erhan Y, Oktay B, Lokman K, Nurettin A, Erhan S. Mechanical performance of hybrid Ilizarov external fixator in comparison with Ilizarov circular external fixator. Clin Biomech 2003;18:518-22. [ Links ]

11. Antoci V, Voor MJ, Antoci Jr V,Roberts CS. Biomechanical effect of transfixion wire tension on the stiffness of external fixation. 5th Combined Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Societies of Canada, USA, Japan and Europe. Poster No: 367. [ Links ]

12. Caja VJ, Kim W, Larsson S, Chao EYS. Comparison of the mechanical performance of three type of external fixators: linear, circular and hybrid. Clin Biomech 1995;10:401-406. [ Links ]

13. Roberts CS, Antoci V, Antoci Jr V, Voor MJ. The effect of transfixion wire crossing angle on the stiffness of external fixation: A biomechanical study. Injury 2005;36:1107-12. [ Links ]

14. Aronson J. Limb lengthening, skeletal reconstruction, and bone transport with the Ilizarov method. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:1243-58. [ Links ]

15. Ferreira N, Mare PH, Marais LC. Circular external fixator application midshaft tibial fractures: Surgical technique. SA Orthop J 2012;11 (4):39-42. [ Links ]

16. Long WT, Chang W, Brien EW. Grading system for gunshot injuries to the femoral diaphysis in civilians. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;408:92-100. [ Links ]

17. Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: A new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma 1984;24:742-46. [ Links ]

18. Rüedi TP, Allgöwer M. The operative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the lower end of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;138:105-10. [ Links ]

19. Schatzker J, McBroom R, Bruce D. The tibial plateau fracture: the Toronto experience: 1968-1975. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979;138:94-104. [ Links ]

20. Moore TM. Fracture-dislocation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res.1981;156:128-40. [ Links ]

21. Hohl M. Tibial condylar fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49:1455-67. [ Links ]

22. Hohl M, Luck JV. Fractures of the tibial condyle: a clinical and experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1956;38:1001-1018. [ Links ]

23. Bibbo C, Brueggeman J. Prevention and management of complications arising from external fixation pin sites. J Foot Ankle Surg 2010;49:87-92. [ Links ]

24. R Rose. Pin site care with the Ilizarov circular fixator. The Internet Journal of Orthopedic Surgery 2009;16(1):1-4. [ Links ]

25. Checketts RG, MacEachern AG, Otterburn M. Pin track infection and the principles of pin site care. In: De Bastiani A, Graham Apley A, Goldberg A (eds) Orthofix external fixation in trauma and orthopaedics. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, 2000, pp 97-103. [ Links ]

26. Ferreira N, Marais LC, Aldous C. Challenges and controversies in defining and classifying tibial non-unions. SA Orthop J 2014;13:52-56. [ Links ]

27. Ferreira N, Marais LC, Aldous C. The pathogenesis of tibial non-union SA Orthop J 2016;15:51-60. [ Links ]

28. Frolke JP, Patka P. Definition and classification of fracture non-unions. Injury 2007;38 Suppl 2:S19-22. [ Links ]

29. Megas P. Classification of non-union. Injury. 2005;36 Suppl 4:S30-7. [ Links ]

30. Ferreira N, Marais LC, Aldous C. Management of tibial non-unions: Prospective evaluation of a comprehensive treatment algorithm. SA Orthop J 2016;15:60-66. [ Links ]

31. LC Marais, N Ferreira, C Aldous, TLB le Roux. The management of chronic osteomyelitis Part I - Diagnostic work-up and surgical principles. SA Orthop J 2014;13:42-48. [ Links ]

32. Cierny G, Mader JT. Adult chronic osteomyelitis. Orthopedics 1984;7:1557-64. [ Links ]

33. Mader JT, Shirtliff M, Calhoun JH. Staging and staging application in osteomyelitis. Clin Inf Dis 1997;25:1303-309. [ Links ]

34. Rogers LC, Bevilacqua NJ, Frykberg RG, Armstrong DG. Predictors of postoperative complications of Ilizarov external ring fixators in the foot and ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg 2007;46(5):372-75. [ Links ]

35. MP Magadum, CM Basavaraj Yadav, MS Phaneesha, LJ Ramesh. Acute compression and lengthening by the Ilizarov technique for infected nonunion of the tibia with large bone defects. J Orthop Surg 2006;14(3):273-74. [ Links ]

36. Iacobellis C, Antonio Berizzi A, Aldegheri R. Bone transport using the Ilizarov method: a review of complications in 100 consecutive cases. Strat Traum Limb Recon 2010;5:17-22. [ Links ]

37. Kamat AS. Infection rates in open fractures of the tibia: Is the 6-hour rule fact or fiction? Adv Orthop 2011;15:1-4. [ Links ]

38. Nieuwoudt L, Ferreira N, Marais LC. Short-term results of grade III open tibia fractures treated with circular fixators. SA Orthop J 2016;15:20-26. [ Links ]

39. Alemdaroglu KB, Tiftikci U, Iltar S, et al. Factors affecting the fracture healing in treatment of tibial shaft fractures with circular external fixator. Injury 2009;40:1151-56. [ Links ]

40. Harris AM, Althausen PL, Kellam J, Bosse MJ, Castillo R. Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) Study Group. Complications following limb-threatening lower extremity trauma. 2009 J Orthop Trauma 2009;23(1):1-6 [ Links ]

41. Chung KC, Saddawi-Konefka D, Haase SC, Kaul G. A cost-utility analysis of amputation versus salvage for Gustilo IIIB and IIIC open tibial fractures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009; 124(6):1965-73. [ Links ]

42. MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ. Factors influencing outcome following limb-threatening lower limb trauma: lessons learned from the Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP). J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006;14(10 Spec No.):S205-10. [ Links ]

43. Ferreira N, Marais LC. The effect of HIV infection on the incidence and severity of circular external fixator pin track sepsis: a retrospective comparative study of 229 patients. Strat Traum Limb Recon 2014;9:111-15. [ Links ]

44. Karipersad, VS. Fracture fixation in HIV-positive patients: A literature review. SA Orthop J 2009;8:41-43. [ Links ]

45. Castillo RC, Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Patterson BM; the LEAP Study Group. Impact of smoking on fracture healing and risk of complications in limb-threatening open tibia fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2005;19(3):151-57. [ Links ]

46. Schmitz MA, Finnegan M, Natarajan R, Champine J. Effect of smoking on tibial shaft fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;365:184-200. [ Links ]

47. Patel RA, Wilson RF, Patel PA, Palmer RM. The effect of smoking on bone healing: A systematic review. Bone & Joint Research. 2013;2(6):102-11. [ Links ]

48. Wukich D, Belczyk R, Burns P, Frykberg R. Complications encountered with circular ring fixation in persons with diabetes mellitus. Foot Ankle Int. 2008 Oct;29(10):994-1000. [ Links ]

49. Iobst CA, Liu RW. A systematic review of incidence of pin track infections associated with external fixation. J Limb Lengthen Reconstr 2016;2:6-16. [ Links ]

50. Parameswaran AD, Roberts CS, Seligson D, Voor M. Pin tract infection with contemporary external fixation: how much of a problem? J Orthop Trauma. 2003 Aug;17(7):503-507. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Nico van der Walt

65 Paterson street

Newcastle, KwaZulu-Natal

tel: +27 34 0620985

email: nstvdw@gmail.com

Received: March 2018

Accepted: July 2018

Published: November 2018

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.