Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309

Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.16 n.4 Centurion Nov./Dec. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2017/v16n4a8

UPPER LIMB

The aetiology of acute traumatic occupational hand injuries seen at a South African state hospital

Stewart AI; Biddulph GII; Firth GBIII

IMBChB(UCT), Orthopaedic registrar, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, University of Witwatersrand

IIMBBCh, FC(Orth)SA, Orthopaedic surgeon, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, University of Witwatersrand

IIIMBBCh, FC(Orth)SA, MMed(Orth), Orthopaedic surgeon, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, University of Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Acute traumatic occupational hand injuries are the second most common cause of all traumatic hand injuries worldwide and the most commonly injured body part during occupational accidents. Traumatic hand injuries account for approximately one-third of all traumatic injuries seen at state hospitals in South Africa. The aetiology of occupational hand injures in South Africa is unknown.

AIM: The purpose of this research was to highlight the patient demographics and types of hand injuries sustained on duty and to identify the most common causes and risk factors for these injuries

METHODS: An observational cross-sectional study was done at a state hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa, between January and July 2016. A total of 35 patients over the age of 18 years were interviewed using a specially designed questionnaire.

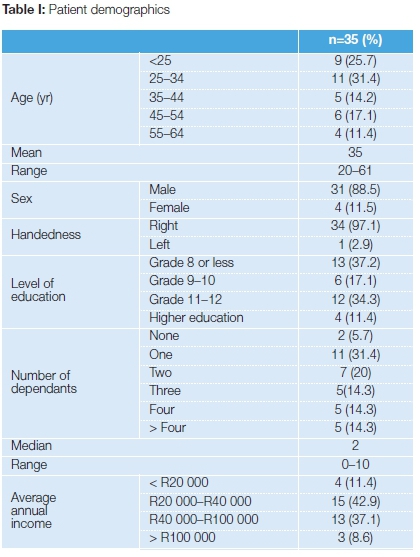

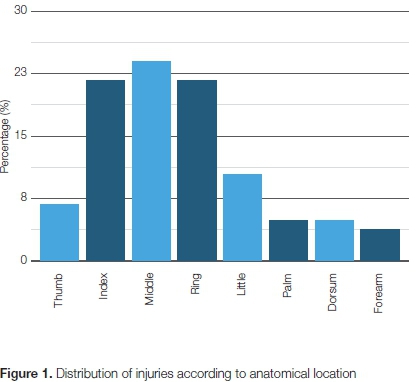

RESULTS: The patients were predominantly male (88.5 %) between the ages of 20 and 61 years (average 35), 54% had dropped out of school before Grade 11. The average monthly income was low (R1 000-R9 000 pm) and 85% were the primary breadwinner in the household. Only 51 % of the patients had 'formal' employment, the rest were either self-employed, contract workers or had intermittent 'piece' jobs. The majority of injuries occurred to machine operators, general manual labourers and construction workers. Eighty per cent of the patients had never received any occupation-specific training. Seventy-one per cent of the patients were not using any protective gloves at the time of injury. The most common sources of injury were power tools, powered machines and building material. Lacerations, crush injuries and fractures were the most common type of injury seen, involving predominantly the index, middle and ring finger. Twenty-eight per cent sustained minor injuries, 34% moderate, 20% severe and 17% major as defined by the Hand Injury Severity Score.

CONCLUSION: Patients with traumatic work-related hand injuries are poorly trained and often are not provided with protective gloves. They typically injure their index, middle and ring fingers using either a power tool, powered machine or by handling building material. The injuries sustained are most commonly lacerations, fractures and crush injuries. As a result, occupational health and safety must be improved to reduce the socio-economic burden of these injuries. Novel ways of improving safety in the informal labour market are required.

Level of evidence: Level 4

Key words: hand injuries, occupational injuries, occupational health and safety, angle grinder, HISS score

Introduction

Acute traumatic occupational hand injuries are especially common in South Africa. They account for significant time off work, loss of income, change in or loss of occupation and residual functional impairment.1 In a developing country, like South Africa, with high unemployment rates, a loss of income can be particularly devastating.2 South Africa has an unemployment rate of 25%,3therefore competition for employment is high, especially in the country's agriculture, mining and manufacturing sectors.2 As a result, residents are often employed in the informal labour market, in jobs for which they are given no specific training. This puts them at high risk of traumatic occupational injuries.4

In South Africa, it has been shown that there are shortfalls in the implementation of the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (COIDA) in the informal labour market.5 This results in employees being unable to access the correct channels of health care and compensation following their injuries. State hospitals are therefore overburdened with these types of patients.

Campbell et al. introduced the Hand Injury Severity Score (HISS) as a research tool. Their aim was to design a score that would grade hand injuries according to their severity as a guide to likely outcomes.6 The HISS evaluates anatomical components of the wrist and hand in four domains known as the ISMN: Integument (skin and nail), Skeletal (bone and ligament), Motor (tendon) and Neural (nerve and vascular). The total scores are converted to four categories: minor (<20), moderate (21-50), severe (51-100) and major (>100). There is a statistically significant correlation between the HISS and the resultant time off work, ability to return to the original occupation and post-rehabilitation hand strength.7-10

Occupational hand injuries are one of the leading causes of days off work, and result in a significant loss of productivity in South Africa's economy. Despite the obvious burden of disease that these injuries present to South Africa as a society, there is a great deal to learn about the potential risk factors, causes and preventative measures that can be taken in the future.

The aim of this study was to highlight the patient demographics and types of hand injuries sustained on duty and to identify the most common causes and risk factors for these injuries.

Methods

Following ethical approval (M150423), the study was carried out between January 2016 and July 2016. An observational, cross-sectional study was done on 35 patients over the age of 18 years, hospitalised at a tertiary care hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. Patients with occupational hand injuries who presented with secondary sepsis were excluded because they skewed the results of the injury severity score.

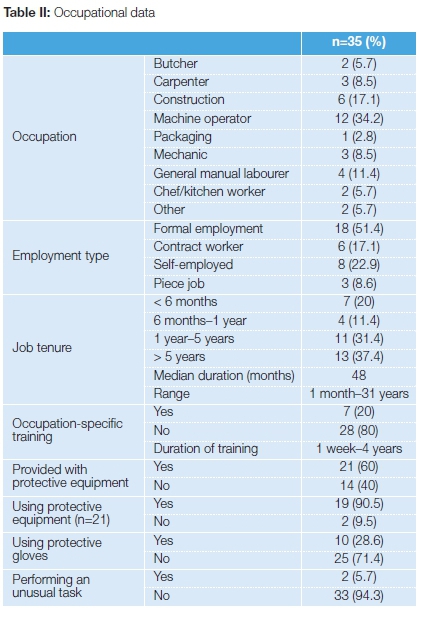

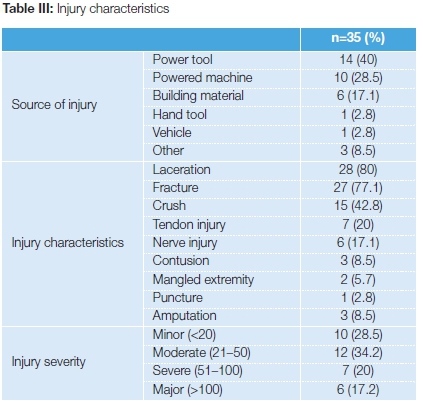

A specially designed questionnaire was used which included basic demographics, economic data such as average annual income, type of employment and whether they were considered the 'primary breadwinner' in the household (Table I). Occupation-specific data included any specific skills learned, work experience, level of training, the use of personal protective equipment, and if they were performing an unusual task at the time of injury (Table II). Injury data included the source of the injury and if a previous injury had occurred (Table III). The injury characteristics were documented and the Hand Injury Severity Score (HISS) was calculated by the main author (AS).

Results

The results showed that the patients were predominantly male (88.5%) between the ages of 20 and 61 years (average 35), with 54% having dropped out of school before Grade 11.

The average monthly income was between R1 000 and R9 000 and 85% were the primary breadwinner in the household. Almost all of the patients (94.3%) had a dependant relying on them for financial support; the median number of dependants was two (range 0-10).

Only 51% of the patients had formal employment. The remaining 49% were either self-employed, contract workers or had intermittent piece jobs.

The majority of injuries occurred in machine operators, general manual labourers and construction workers. Eighty per cent of the patients had never received any occupation-specific training. Only 60% were provided with some form of protective equipment, and only 28.6% were given protective gloves.

The majority of patients were not performing an unusual task at the time of injury (94.3%), nor were they using an unfamiliar machine.

The most common source of injury was a power tool (40%), followed by a powered machine (28.5%) and building material (17.1%). Other sources included hand tools, vehicles, knives and electrical burns.

Lacerations, crush injuries of the nail bed and fractures were the most common type of injuries seen, followed by tendon and nerve injury. Twenty-five patients sustained a combination of multiple types of injuries. Fractures and lacerations were often associated resulting in a total of 22 open fractures (78.5%).

The index, middle and ring finger were the most common digits injured. There was a total of two amputated thumbs, two amputated index fingers and one amputated middle finger (two separate patients). There was one mangled extremity resulting in an amputation through the wrist (Figure 1).

According to the HISS, 28.5% sustained minor injuries, 34.2% moderate, 20.2% severe and 17.1% major.

Patients who injured their left hand on average sustained a moderate injury (average score = 45), whereas those patients who injured their right hand sustained a severe injury (average score = 57).

The median job tenure was four years, with a range of between one month and 31 years.

Job tenure did not seem to affect the risk of sustaining a work-related hand injury; however, it did affect the severity of the injury incurred. Those patients who were injured in their first year of work sustained a mean injury severity score of 75 (severe), whereas those patients who were injured after they had been at their current job for at least one year sustained a mean injury severity score of 32 (moderate).

Discussion

This research found that occupational hand injuries correlate well with individual patient characteristics such as young age, male gender, poor education and lack of training, which is consistent with findings in similar studies from around the world.11 The predominant male population in this study conformed to most other studies on this subject and fits in with the typical young, working class individual. In South Africa, young men are often required to drop out of school early to find employment, which typically involves manual labour-type jobs. Most of the patients in this study were poorly educated - 90% had failed to progress past a high school education. Work-related hand injuries are particularly common in younger individuals; Olsen et al. demonstrated that young workers of 24 years or younger had the highest risk of occupational hand and finger trauma.12 The majority of the patients in this study would be considered to be in the low-to-middle income bracket and most of them were the sole income earners in the household. These patients were often responsible for the financial security of multiple other dependants at home. Therefore, any loss of income due to injury would cause significant financial stress and could be potentially devastating if the patient were left permanently disabled.

There have been various studies done outside of South Africa looking at the most common causes of occupational injuries. Throughout the literature the three most common causes are power tools, powered machines and building material, affecting most frequently, therefore, construction workers, mechanics, carpenters and food handlers.13-18 The results of our study are in keeping with similar studies from around the world. In our population, the most common cause was due to power tools (40%), most commonly the angle grinder. Angle grinders are versatile tools which make them extremely popular. What commonly occurs is that the safety guard is removed from the grinder or a non-standard cutting or grinding disk is used in order to increase the versatility of the grinder. When these tools are altered or adjusted, the risk of their failing increases, which can lead to frequent and severe injuries. Powered machines, especially the machine press and cutting machines such as the band saw, contributed to almost 28.5% of the total hand injuries. When compared to injuries due to power tools, injuries resulting from a powered machine were most commonly not due to equipment malfunction, but most likely due to human error.

In South Africa, the Department of Labour has stipulated that it is mandatory for all employers to provide and maintain a working environment that is safe and without risk to the health of the employees; this includes providing appropriate safety equipment.19 In our study only 60% of the workers were provided with some form of protective equipment by their employers. This figure includes any form of protection such as headgear, eye protection, protective clothing or boots. Strangely, even though more than half of the workers were offered protective equipment, very rarely did it include protective gloves. Only 28.6% of all the injured workers were using protective gloves at the time of injury. In previous studies it has been shown that wearing no or ill-fitting gloves is associated with an increased risk of an occupational hand injury; the use of protective gloves may also decrease the risk of injury.16,20 However, glove use has been shown to protect against lacerations and puncture wounds but not against fractures, avulsions, amputations and dislocations.21 This may be why the use of protective gloves in our population did not seem to affect the injury severity.

Injury characteristics

Although the overwhelming majority of patients in this study were right-hand dominant, there was a fairly equal distribution between right- and left-hand injuries. No patients sustained injuries to both hands. These results are in keeping with results of similar studies from around the world.4,11,13,16,18 For more than 90% of the patients this was their first work-related hand injury in the past year.

Occupational hand injuries can result in significant time off work and often lead to a forced change in occupation or permanent disability. Trybus et al. found that approximately 10% of patients never returned to their original occupation, either due to permanent disability or due to a change in occupation.4 In the same study they also found that 58.5% of all hand injuries had residual functional impairment despite adequate rehabilitation. Ahmed showed that 19% of injured hands had a significant loss of function despite adequate rehabilitation.22Lacerations, crush injuries and fractures were the most common types of injuries documented. Most patients had a combination of a laceration and a fracture resulting in an open fracture, which may lead to increased risk of infection as well as complications in wound healing. These injury patterns are in keeping with the most common source of injury (power tool, powered machine) which result in a relatively high energy injury. The crush injuries that were documented were predominantly of the distal phalanx resulting in a nail bed injury or associated fracture.

Injury severity

There was a fairly equal distribution between the different categories of injury severity using the HISS system. Similar studies have reported vastly different distributions of the HISS score; this is predominantly due to where their subjects were recruited from. The hospital where this study was done accepts both walk-ins and referrals from level 1 and level 2 referral centres; it also has a dedicated hand unit with a 24-hour re-implantation team on standby. Therefore, it acts as both a primary care and tertiary/quaternary institute. The mean HISS score and the overall range were higher than reported in the original study by Campbell and Kay despite a very similar study population in terms of overall patient number, age, sex and handedness. This may be due to other variables such as the nature of the work carried out at the time of injury or the source of injury.6 The average HISS score was higher for males than females. Although not statistically significant, this is in keeping with the fact that males were more likely to be employed as manual labourers or work with an angle grinder. The average HISS scores for patients wearing or not wearing any protective gloves was the same (50 vs 49). Therefore, wearing of protective gloves did not seem to affect the severity of injury incurred. But this does not take into account what the severity of the injury may have been had the patient not been wearing gloves at the time of injury.

There seems to be no consensus in the literature as to whether work experience alone may put someone at risk for an occupational hand injury. In our study, there was no significant difference in the mechanism of injury or the injury severity between those patients with more work experience versus those who had less. This implies that work experience alone may not play such an important role in the incidence or the aetiology of occupational hand injuries. The majority of patients in this study were young, however, which may have had an influence on the amount of work experience achieved in this population. Work experience may provide workers with knowledge of potential hazards as well as familiarity with the machine or tool which they are required to use. However, the cumulative risk of injury may also increase the longer a worker is exposed to a specific hazard, and it is also possible that familiarity with a task may result in potentially increased risk of injury.16,20,23

Just over 50% of the injured workers in this study had permanent employment, with a signed contract. The rest were either self-employed, contract workers or worked 'piece jobs'. According to the COIDA if an employee is injured as a result of an accident, resulting in a disablement or death, the employee or the dependants of the employee shall be entitled to the benefits prescribed in the Act. This may include the cost of medical aid at a private health care facility and subsequent financial compensation. Often permanent employees and contract workers are not registered in terms of the COIDA or struggle to claim compensation following injury, or they are unaware that they are entitled to private health care. These patients then end up at state hospitals which shifts costs to workers and overburdens an already busy health care system. It also promotes an underreporting of occupational injuries by employers and medical practitioners.24

Conclusion

The typical patient who presents to a state hospital in South Africa with an acute traumatic occupational hand injury is a young male, who is poorly educated, with a low income and multiple dependants. This patient is poorly trained for the type of work he is required to do and he is often not provided with protective gloves. These patients typically injure their index, middle and ring fingers using either a power tool, powered machine or by handling building material.

The injuries sustained are most commonly lacerations, fractures and crush injuries, but may also include tendon and nerve injuries as well as amputations.

As a result of the high rate of occupational-related hand injuries in this South African population, occupational health and safety must be improved to reduce the socio-economic burden of these injuries. Novel ways of improving safety in the the informal labour market such as compulsory training, provision of safety equipment and regulation of tools and machines is required.

A larger, multi-centre study is recommended for a more demographic representation of occupational hand injuries.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Ethical approval (M150423) was obtained to carry out the study.

References

1. Leigh J, Macaskill P, Kuosma E, et al. Global Burden of disease and injury due to occupational factors. Global Occupational Disease and Injury. 1999;10(5):626-31. [ Links ]

2. African Economic Outlook 2014. South Africa. http://www.african-economicoutlook.org (accessed 17 March 2015) [ Links ]

3. Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force survey: Quarter 3 (July to September) 2014. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=3453 (accessed 21 March 2015). [ Links ]

4. Trybus M, Lorkowski J, Brongel L, et al. Causes and consequences of hand injuries. Am J Surg. 2006;192(1):52-57. [ Links ]

5. Benjamin P. Labour market regulation: International and South African perspectives. Human Sciences Research Council. 2005. [ Links ]

6. Campbell D, Kay S. The Hand Injury Severity Scoring System. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1996;21B(3):295-98. [ Links ]

7. Van Der Molen M, Ettema A, Hovius S. Outcome of Hand Trauma: The Hand Injury Severity Scoring System (HISS) and subsequent impairment and disability. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2003(28B):295-99. [ Links ]

8. Matsuzaki H, Narisawa H, Miwa H, et al. Predicting functional recovery and return to work after mutilating hand injuries: usefulness of Campbells Hand Injury Severity Score. J Hand Surg [Am] xxxxx [ Links ]

9. Chen YH, Lin HT, Lin YT, et al. Self-perceived health and return to work following work-related hand injury. Occup Med (Oxf). 2012;62(4):295-97. [ Links ]

10. Lin D, Chang JH, Shieh SJ, et al. Prediction of hand strength by injury severity scoring system in hand injured patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(5):423-28. [ Links ]

11. Chau N, Gauchard GC, Siegfried C, et al. Relationships of job, age and life conditions with the causes and severity of occupational injuries in construction workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2004;77(1):60-66. [ Links ]

12. Olsen DK, Gerberich SG, Goodwin S. Traumatic amputations in the workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 1986;28(7):480-85. [ Links ]

13. Jin K, Lombardi DA, Courtney TK, et al. Patterns of work-related traumatic hand injury among hospitalized workers in the People's Republic of China. Inj Prev. 2010;16(1):42-49. [ Links ]

14. Garg R, Cheung J, Fung B. Epidemiology of occupational hand injury in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 2012;18(2):131-36. [ Links ]

15. Sorock G, Lombardi D, Hauser R. Acute traumatic occupational hand injuries: Type, Location and Severity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2002;44(4):345-51. [ Links ]

16. Chow C, Lee H, Yu I. Transient risk factors for acute traumatic hand injuries: A case-crossover study in Hong Kong. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2007;64:47-52. [ Links ]

17. Serinkin M, Karcioglu O, Sener S. Occupational hand injuries treated at a tertiary care facility in western Turkey. Ind Health. 2008;46:239-46. [ Links ]

18. Ihekire O, Salawu S, Opadele T. Causes of hand injuries in a developing country. Can J Surg. 2009;53(3):161-66. [ Links ]

19. South Africa. Occupational Health and Safety Amendment Act No 181 of 1993. [ Links ]

20. Choi W, Cho S, Han S. A case-crossover study of transient risk factors for occupational traumatic hand injuries in Incheon, Korea. Journal of Occupational Health. 2012;54:64-73. [ Links ]

21. Sorock GS, Lombardi GA, Peng DK, et al. Glove use and the relative risk of acute hand injury: A case-crossover study. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1:182-90. [ Links ]

22. Ahmed E. The management outcome of acute hand injury in Tikur Anbessa University Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 2010;15(1 ):48-56. [ Links ]

23. Sorock GS, Lombardi DA, Hauser R. A case-crossover study of transient risk factors for occupational acute hand injury. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2004;61 (4):305-11. [ Links ]

24. Ehrlich R. Persistent failure of the COIDA system to compensate occupational disease in South Africa. SAMJ. 2012;102:95-97. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr A Stewart

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

7 York Road, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa

2193: Cell: (+27) 0824485953; Tel: (+27) 011 883 3061

Fax: (+27) 011 7844997

Email: stwand010@gmail.com

Received: January 2017

Accepted: June 2017

Published: November 2017

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Editor: Prof Anton Schepers, University of the Witwatersrand