Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309

Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.15 n.3 Centurion Aug./Sep. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2016/v15n3a7

KNEE

Periarticular local anaesthetic in knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials

Dr ML GibbinsI; Dr C Kane II; Dr RW SmitIII; Dr RN RodsethIV

IMBChB, DTMH, Anaesthetics and Intensive Care Medicine Specialist Trainee, Severn Deanery School of Intensive Care Medicine and Anaesthesia, Bristol, United Kingdom

IIBA(Hons) MBChB, DA, Core Anaesthetics Trainee, South West Peninsula School of Post Graduate Medical Education, Torquay, United Kingdom

IIIMBChB, FCOrtho, CIME, Honorary Clinical Associate, Department of Orthopaedics, Grey's Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IVMBChB, FCA, MMed, MSc, PhD, Honorary Clinical Associate, Perioperative Research Group, Department of Anaesthetics, Grey's Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa; Department of Outcomes Research, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to quantify the effect of adding peri-articular local anaesthetic infiltration or infusion to an analgesic strategy in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty.

METHODS: A literature search of six data bases was performed. Randomised controlled trials comparing periarticular local anaesthetic infiltration/infusion against other analgesic strategies in adult patients undergoing knee arthroplasty were included. The primary outcome was resting Visual Analogue Scores 24 hours after surgery.

RESULTS: In the review, 396 potential studies were identified, of which 35 full text articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 770 patients from 12 trials were included in the final meta-analysis. Local anaesthetic addition significantly improved pain control (mean difference -0.95 [95% CI -1.68 to -0.21]); however, there was significant heterogeneity (I2: 88%).

CONCLUSION: Our analysis suggests that peri-articular local anaesthetic infiltration/infusion improves resting pain scores 24 hours after knee arthroplasty. However, the heterogeneity of these findings urges caution in their interpretation.

Key words: local anaesthetic, arthroplasty, knee arthroplasty, knee replacement, intra-articular injections

Introduction

The provision of adequate post-operative analgesia in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty presents a significant challenge. A multimodal approach to pain control in these patients has been commonly adopted with regimens including opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, adjuncts such as gabapentin or pregabalin, and the use of neuraxial and peripheral nerve blockade. Peri-articular injections and infusion of local anaesthetic holds great attraction as it provides localised analgesia without the side effects often seen with neuraxial or peripheral nerve blockade. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine whether, in adults undergoing knee arthroplasty, adding peri-articular local anaesthetic to a post-operative pain regimen improved post-operative pain scores.

Methods

The PRISMA guidelines were followed in conducting and reporting this review.1 The protocol for this review was not registered.

Trial eligibility and identification

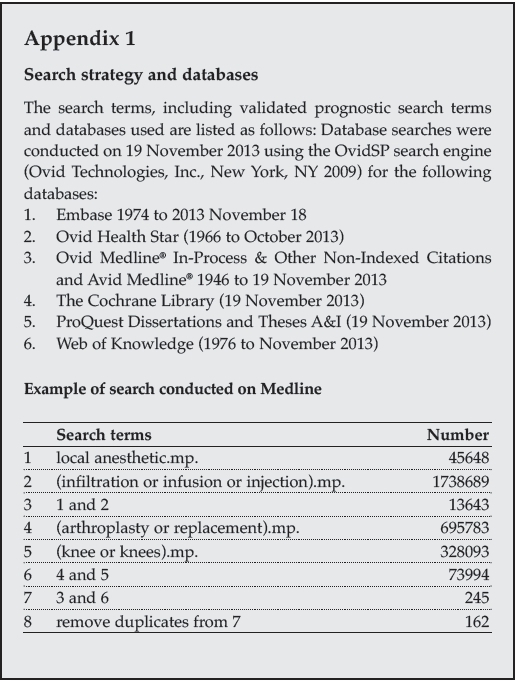

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in adult patients undergoing knee arthroplasty, in which a peri-operative pain regimen including peri-articular local anaesthetic administration which was evaluated using a visual analogue score (VAS), was compared to a regimen without peri-articular local anaesthetic, were considered eligible. Trials were included regardless of language, sample size, publication status, or date of publication. On 19 November 2013, six databases were searched (Embase, Ovid Health Star, Ovid Medline® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Avid Medline®, The Cochrane Library, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I, and Web of Knowledge). The search terms with key words used were as follows: local anaesthetic; infiltration or infusion or injection; arthroplasty or replacement; knee or knees. Appendix 1 provides an example of the search strategy used. The search was updated on 12 December 2014.

Eligibility assessment

Working in pairs we independently screened the title and abstract of each citation to identify potentially eligible trials. If either reviewer felt the citation contained a relevant trial, the article was retrieved to undergo full text evaluation. Full texts of all citations identified as being potentially relevant were then independently evaluated to determine eligibility. Disagreements were solved by consensus. Chance corrected inter-observer agreement for trial eligibility was tested using kappa statistics. Only RCTs conducted in adult patients (>17 years of age) undergoing knee arthroplasty where peri-articular local anaesthetic was added to a peri-operative analgesic regimen were considered eligible. The trial outcome had to report visual analogue scores (VAS) at rest at 24 hours after surgery to be included in the final meta-analysis. Where not reported in the text these values, together with their standard deviations, were read from study tables and graphs. Where this data was not available attempts were made to contact trial authors. Abstracts, including meeting abstracts, were not planned for inclusion.

Data collection, assessment of trial quality, bias and outcomes

For each eligible trial we attempted to extract the outcome of VAS at rest - 24 hours after surgery together with its standard deviation. Where studies included more than two groups we selected data from the control arm not making use of any local anaesthetic and data from the arm with the maximal peri-articular local anaesthetic protocol (i.e. continuous infusion of local anaesthetic was used in preference over a single shot local anaesthetic injection arm). Where trials reported the inter-quartile range and not the standard deviation the standard deviation was estimated to be 0.75 of the width of the interquartile range.2 Where bilateral replacements were done pain scores for each knee were evaluated individually.

Trial quality and bias was evaluated using the following criteria: randomisation methodology, completeness of patient follow-up, method of patient follow-up, blinded outcome assessment, consistent endpoint assessment, and the use of intention to treat analysis.

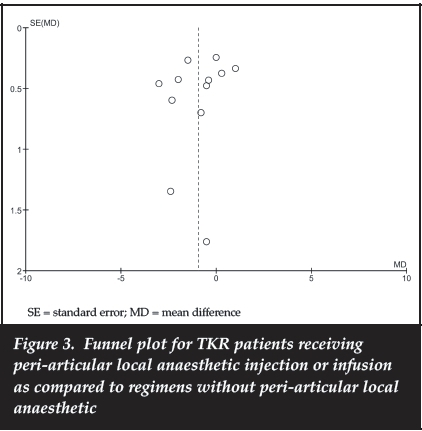

Meta-analysis of the mean difference between pain protocols including peri-articular local anaesthesia and protocols without peri-articular local anaesthesia was conducted using a random effects model in Review Manager Version 5.1. (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011). Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and chi-squared analysis. The pooled outcome was reported as a mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We constructed a funnel plot to assess for the possibility of publication bias.

Results

Trial identification and selection

The trial selection process is shown in Figure 1. We identified 396 citations, from which 35 were selected for full-text evaluation. From these we identified 12 eligible RCTs.3-14 Inter-observer agreement for trial eligibility was good (kappa = 0.75; SE 0.053).

Table I reports the characteristics of the included trials and the local anaesthetic protocols used in the trials. Table II reports the details of the comparator analgesic protocols used as well as the background analgesic protocols used for all enrolled patients, and Table III provides the quality characteristics for all included trials.

Study outcomes

The VAS score at 24 hours was reported in all included trials and provided a total of 386 patients receiving periarticular local anaesthetic and 384 patients receiving other peri-operative analgesia. Patients who received peri-articular local anaesthetic showed a statistically significant reduction in their pain score at 24 hours after surgery (mean difference -0.95; 95% CI -1.68 to -0.21; I2=88%) (Figure 2). The funnel plot for the analysis is shown in Figure 3 and shows a lack of reporting bias among the selected trials.

Discussion

Statement of principle findings

Our meta-analysis of 12 RCTs, which included a total of 770 patients, found that the addition of peri-articular local anaesthetic infiltration or infusion (LAi) to a postoperative analgesic regimen resulted in a statistically significant reduction in VAS pain scores at 24 hours after total knee arthroplasty (mean difference -0.95; 95% CI -1.68 to -0.21; I2=88%).

Strengths

We performed a rigorous search of the databases to ensure all published and non-published studies were identified. Only RCTs reporting objective measures of pain were included and inter-observer agreement for inclusion of trials was good. Where trials were thought to be eligible, but did not include the relevant outcome measures or we were unable to locate the full text article, every effort was made to contact the authors to obtain the required information.

Weaknesses

Despite a rigorous search of six databases, the possibility that relevant RCTs may have been missed cannot be excluded.

Pain is a subjective entity and as result difficult to quantify and measure. VAS is a validated method of measuring pain, and as a result we only included studies using this method. This led to the exclusion of 12 studies (nine as VAS was not used and three as no VAS score was reported at 24 hours), thus potentially significant data was excluded. We felt this unavoidable as to perform a meta-analysis an objective outcome common to all studies is required. Several studies used Numeric Rating Scales (NRS) to assess pain. As there is likely correlation between the two methods, we considered converting NRS into VAS equivalents. However, VAS uses a continuous scale whereas NRS uses an interval scale and we could find no validated method with which to perform the conversion. Therefore studies using NRS were not included as we felt it may undermine the reliability of our meta-analysis. Despite our best efforts, one trial was excluded as we were unable to locate the full article or contact the author - once again potentially excluding significant data.

Several trials included VAS scores but the data (mean and standard deviation) was not expressed numerically. Efforts were made to contact the authors for the relevant information; however, where the numerical data was unobtainable we calculated it from graphs provided.12 These attempts to extract the relevant data introduce a risk of error in measurement. However, we felt the risk of this error was outweighed by the benefit of being able to include the data within the meta-analysis.

I2 and chi-squared analysis revealed significant heterogeneity between the trials included in the meta-analysis. There are several factors that likely contribute to the observed heterogeneity. The outcomes sought in this review more likely follow a skewed, non-normal distribution as confirmed by authors of the three most methodologically rigorous studies. As pooling of data for meta-analysis involves normally distributed data, converting median and interquartile range (IQR) to mean and SD will introduce a degree of uncertainty in the estimate of effect.

The trials included in this analysis have used a wide variety of interventions to provide post-operative analgesia for total knee arthroplasty. However, it is important to note that despite these differences the addition of LAi to any regimen resulted in a reduction in post-operative pain scores. This, together with the unique mechanism by which local anaesthesia provides analgesia, and the lack of reporting bias shown in the funnel plot, suggests that these findings reflect a true additive analgesic effect over and above other analgesic modalities.

This study in relation to other studies and future research

In 2014, Andersen and Kehlet published a systematic review of the analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia in hip and knee arthroplasty.15 Their analysis of the literature comprised individual comparisons of local anaesthetic injection to placebo, peripheral nerve block, epidural and systemic analgesia. They concluded that in total knee arthro-plasty, most randomised controlled clinical trials demonstrated improved analgesia in patients receiving LAi, even in combination with multimodal systemic analgesia, particularly within the early post-operative period - thus supporting the findings of our meta-analysis. However, their review highlighted the variability between the studies and some of the methodological pitfalls commonly encountered; many studies were vulnerable to confounding and bias due to incomplete blinding, variations in background analgesia between intervention and control groups and the lack of control for the systemic effects of drugs included within the local anaesthetic injectate - such as NSAIDs. They also stated that 'the lack of a ... meta-analysis of study outcome measures' may be a limitation to their review.

Andersen et al. themselves performed a randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial assessing LAi versus placebo in 12 consecutive patients undergoing bilateral TKR, thus providing the optimum controls and eliminating many of the confounding issues experienced by other trials.16 This study was excluded from our final meta-analysis as VAS pain scores were not used. However, despite its small study size, it can be considered one of the more methodologically rigorous trials assessing the benefit of LAi and it found a statistically significant reduction in Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) pain scores in patients receiving LAi up to 25 hours post-operatively at rest and 32 hours post-operatively upon 45 degrees flexion. Owing to the use of NRS and not VAS to assess pain, only one study in the final meta-analysis included femoral nerve block in the comparator protocol. Of those studies excluded, Affas et al. performed an RCT of 40 patients comparing intra-operative local anaesthetic infiltration to pre- and post-operative femoral nerve block (via a peri-neural catheter).17 They reported a marginal reduction in pain at rest in the group receiving local anaesthetic infiltration (NRS 1.6 vs 2.1), a statistically significant increase in incidence of intense pain in the femoral nerve block group (1/20 vs 7/19 patients reporting an NRS pain score of >7, p = 0.04) and concluded that although both methods provided good analgesia, local anaesthetic infiltration 'may be considered to be superior to femoral nerve block as it is cheaper and easier'. These findings are supported by Toftdahl et al., who, in their RCT of 80 patients found that those receiving peri-articular infiltration and postoperative infusion of local anaesthetic had lower morphine consumption (83 mg vs 100 mg, p = 0.02) and improved mobility on the first post-operative day (29/39 vs 7/27 able to walk > 3m, p < 0.001).18 However, both Affas and Toftdahl's studies may be subject to bias due to a lack of blinding. Carli et al.'s double-blind RCT of 40 patients reported decrease morphine consumption (14.5 mg vs 26 mg, p = 0.02) and improved six-week recovery (assessed by several criteria) in those receiving continuous femoral nerve block compared to peri-articular local anaesthetic infiltration.19

Of the trials included in our final meta-analysis we consider Andersen3 and Williams13 to have been the most methodologically robust. Andersen performed an RCT comparing LAi (infiltration and 48-hour infusion) to continuous epidural infusion, controlling for the systemic effects of ketorolac in the local anaesthetic mixture and providing identical background analgesic protocols for both groups. They demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in morphine consumption (median 11 mg vs 33 mg at 48 hours) and VAS pain scores (median 5 mm vs 33 mm at 24-48 hours) in the LAi group. Williams's double-blind RCT compared continuous infusion of local anaesthetic for 48 hours to saline infusion.

They reported a non-significant reduction in morphine consumption (mean 39 mg vs 53 mg at 48 hours, p = 0.137) and VAS pain scores (mean 1.7 vs 2.1 at 24 hours p = 0.386) in the intervention group. However, both intervention and control groups received local anaesthetic infiltration intra-operatively.

As well as improved analgesia, one of the perceived benefits of LAi over other techniques is a potentially lower side-effect profile and improved motor function of the operated limb, resulting in earlier and improved rehabilitation. Ilfeld's review of three RCTs in 2010 suggests a causal link between continuous femoral nerve block and patient falls following total knee arthroplasty20 and Andersen reported a statistically significant increase in urinary retention and constipation in the epidural group compared to LAi.3 Vendittoli in 2006 analysed the plasma concentrations of local anaesthetic following LAi and reported that all plasma concentrations were below the toxic range.12 Neither Andersen nor Venditolli reported any complications directly related to LAi, suggesting it is a safe method of providing analgesia.

Andersen and Kehlet's systematic review also reported on length of hospital stay; however, this varied widely and was unrelated to the method of analgesia used.15 Moreover, whether the cause of increase in length of stay was related to pain or not was not reported by any of the studies analysed. As far as we are aware there are no large, high quality studies into the cost effectiveness of Lai; however, the simplicity of the procedure and decreased systemic analgesic requirements demonstrated by some studies imply it may be a cost-effective method of providing analgesia.3,12

There was significant variation in the technique of performing LAi between the studies included in our meta-analysis, which may have contributed to the heterogeneity. Variations include the precise location of single intraoperative injections, the content of injectate and the use of post-operative infusions and boluses via catheters. Several studies have been performed by Andersen into the optimum technique for LAi, including the location of the injection, the concentration and volume of injectate and the use of bandages to improve spread21-25 and Williams et al. demonstrated no significant benefit from a 48-hour infusion of local anaesthetic following intra-operative infil-tration.13 However, there is still little consensus as to the optimum technique. Standardising the procedure of LAi would assist in performing future research into not only the efficacy of LAi for total knee arthroplasty, but also its safety, and cost effectiveness.

Although a degree of caution should be exercised when interpreting the result of our meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity identified, we believe it strongly supports the inclusion of LAi as part of the analgesic regimen for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Further research should focus on the optimum technique of local anaesthetic infiltration and the benefits of additional postoperative infusion.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines Competing interests:

Funding: Dr Rodseth is supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the College of Medicine of South Africa.

Conflicts of interest: None to declare.

Declarations: This work has not been previously submitted or presented in any form.

References

1. Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org/index.htm.

2. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;343:d5928. [ Links ]

3. Andersen KV, Bak M, Christensen BV, Harazuk J, Pedersen NA, Soballe K. A randomized, controlled trial comparing local infiltration analgesia with epidural infusion for total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica. 2010;81(5):606-10. [ Links ]

4. Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A. Reduced morphine consumption and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia (LIA) following total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica. 2010;(3):354-60. [ Links ]

5. Goyal N, McKenzie J, Sharkey PF, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ, Austin MS. The 2012 Chitranjan Ranawat award: intraar- ticular analgesia after TKA reduces pain: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, prospective study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2013;(1):64-75. [ Links ]

6. Han CD, Lee DH, Yang IH. Intra-synovial ropivacaine and morphine for pain relief after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, double blind study. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2007;(2):295-300. [ Links ]

7. Mauerhan DR, Campbell M, Miller JS, Mokris JG, Gregory A, Kiebzak GM. Intra-articular morphine and/or bupiva- caine in the management of pain after total knee arthro- plasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 1997;(5):546-52. [ Links ]

8. Mullaji A, Kanna R, Shetty GM, Chavda V, Singh DP. Efficacy of periarticular injection of bupivacaine, fentanyl, and methylprednisolone in total knee arthroplasty. A prospective, randomized trial. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2010;25(6):851-57. [ Links ]

9. Ong JC, Lin CP, Fook-Chong SM, Tang A, Ying YK, Keng TB. Continuous infiltration of local anaesthetic following total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery (Hong Kong). 2010;18(2):203-207. [ Links ]

10. Reinhardt KR, Duggal S, Umunna BP, Reinhardt GA, Nam D, Alexiades M, et al. Intraarticular analgesia versus epidural plus femoral nerve block after TKA: a randomized, double-blind trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5): 1400-408. [ Links ]

11. Spreng UJ, Dahl V, Hjall A, Fagerland MW, Raeder J. High volume local infiltration analgesia combined with intravenous or local ketorolac plus morphine compared with epidural analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2010;105(5):675-82. [ Links ]

12. Vendittoli PA, Makinen P, Drolet P, Lavigne M, Fallaha M, Guertin MC, et al. A multimodal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, controlled study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series A. 2006;88 (2):282-89. [ Links ]

13. Williams D, Petruccelli D, Paul J, Piccirillo L, Winemaker M, de Beer J. Continuous infusion of bupivacaine following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized control trial pilot study. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2013;28(3):479-84. [ Links ]

14. Zhang S, Wang F, Lu ZD, Li YP, Zhang L, Jin QH. Effect of single-injection versus continuous local infiltration analgesia after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of International Medical Research. 2011;(4):1369-80. [ Links ]

15. Andersen LO, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia in hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(3):360-74. [ Links ]

16. Andersen LO, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. High-volume infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2008;52(10):1331-35. [ Links ]

17. Affas F, Nygârds EB, Stiller CO, Wretenberg P, Olofsson C. Pain control after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial comparing local infiltration anesthesia and continuous femoral block. Acta Orthopaedica. 2011;(4):441-47. [ Links ]

18. Toftdahl K, Nikolajsen L, Haraldsted V, Madsen F, Tonnesen EK, Soballe K. Comparison of peri- and intraarticular analgesia with femoral nerve block after total knee arthro- plasty: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):172-79. [ Links ]

19. Carli F, Clemente A, Asenjo JF, Kim DJ, Mistraletti G, Gomarasca M, et al. Analgesia and functional outcome after total knee arthroplasty: periarticular infiltration vs continuous femoral nerve block. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(2):185-95. [ Links ]

20. Ilfeld BM, Duke KB, Donohue MC. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2010;111(6):1552-54. [ Links ]

21. Andersen LO, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Husted H, Otte KS, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of local anaesthetic wound administration in knee arthroplasty: volume vs concentration. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(10):984-90. [ Links ]

22. Andersen LO, Husted H, Kristensen BB, Otte KS, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of subcutaneous local anaesthetic wound infiltration in bilateral knee arthroplasty: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2010;54(5):543-48. [ Links ]

23. Andersen L, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. A compression bandage improves local infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;(6):806-11. [ Links ]

24. Andersen LO, Kristensen BB, Husted H, Otte KS, Kehlet H. Local anesthetics after total knee arthroplasty: Intraarticular or extraarticular administration? A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(6):800-805. [ Links ]

25. Andersen LO, Husted H, Kristensen BB, Otte KS, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of intracapsular and intra-articular local anaesthesia for knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(9):904-12. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Matthew L.

Gibbins 78 Pembroke Road, Bristol

BS8 3EG, England, United Kingdom

Email: gibbins.matt@gmail.com