Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309

Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.15 n.1 Centurion Mar./Apr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2016/v15n1a3

HIP

Hip arthroscopy: What to tell your patient

JM NellensteijnI; RN VillarII

IMD Orthopaedics; Clinical Fellow at The Villar Bajwa Practice, Cambridge & London, UK

IIBSc (Hons), MA, MS, FRCS; The Villar Bajwa Practice, The Princess Grace Hospital, London, UK

ABSTRACT

Hip arthroscopy has gained popularity in recent years. Although femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is the most common indication for performing the procedure, there are many other conditions affecting the hip joint and its surrounding structures that can also be treated arthroscopically. Before undergoing hip arthroscopy, patients need to be informed about the chances of success of their procedure. In this article we give an overview of the current indications for hip arthroscopic surgery and their clinical outcomes, as revealed in the recent literature.

Key words: hip arthroscopy, femoroacetabular impingement, patient counselling

Introduction

Arthroscopy of the hip has gained popularity in recent years and is an accepted diagnostic tool and treatment option for many problems in and around the hip joint. It is today possible to treat pathologies that were previously unrecognised.

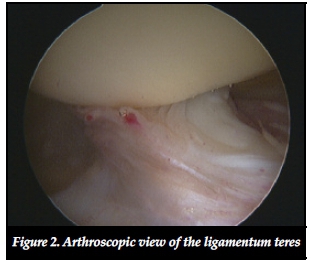

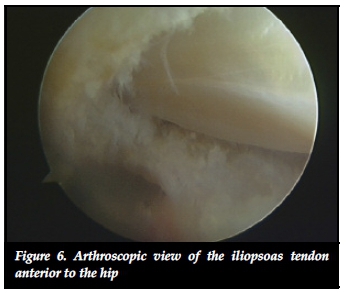

With the development of better and smaller instruments, it is possible to obtain a clear arthroscopic view of the femoral head, the acetabular surface, labrum, ligamentum teres, surrounding synovium and even surrounding structures outside the joint cavity such as the tendons of iliopsoas and rectus femoris, the psoas bursa, trochanteric bursa, and the sciatic nerve.

In the literature concerning hip arthroscopy, damage to the labrum and chondrolabral junction from femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is the main studied morbidity. For many orthopaedic surgeons and practitioners in the orthopaedic field, FAI and its sequelae are still the only reasons for performing hip arthroscopic surgery. Despite this, many other conditions affecting the hip joint and its surrounding structures can be identified and treated by arthroscopic surgery. There is more to hip arthroscopy than just FAI.

Before undergoing such surgery patients clearly need to be informed about the chances of success of their procedure. This is critical information for both the patient and their surgeon. In this article we will thus describe the current indications and outcomes of hip arthroscopic surgery for a variety of conditions and trust it might be used as an aide memoire when counselling patients pre-operatively.

Technique

It is not the purpose of this article to discuss the detailed technique of hip arthroscopy. However, in brief, arthroscopic surgery of the hip allows the surgeon to gain access to both the central (intra-articular and intra-capsular) and peripheral (extra-articular and intra-capsular) compartments of the hip. To create space to ensure access to the central compartment, a distraction device is essential. Special distraction devices are available for both lateral and supine positions. A soft-padded boot on the foot and a wide perineal post are essential to reduce the risk of traction injury. To confirm the position of instruments, fluoroscopy is often used throughout the procedure, although there is a slowly developing trend to either use no imaging at all, or to use ultrasound guidance. A needle is introduced into the joint, followed by a guide wire. Cannulated instruments are then passed over the wire to dilate the joint capsule. After insertion of a 70° arthroscope subsequent portals are placed under direct vision using the same technique. A diagnostic round of both the central and peripheral compartment is undertaken and any pathology treated. The peripheral compartment is entered without traction and the hip slightly flexed. Peri-articular hip endoscopy can also be performed without traction on the leg. Operating instruments include standard power shavers, manual arthroscopic instruments and radiofrequency devices.

FAI

FAI is described as the abutment of the proximal femur on the acetabular rim.1 Three different types can be distinguished; cam, pincer and mixed impingement. In cam-type impingement, the femoral head-neck junction is shaped abnormally, which can lead to labral damage. In the pincer-type impingement the acetabulum is frequently retroverted, which can lead to compression of the labrum in flexion. In the mixed type of impingement, both cam- and pincer-type abnormalities are apparent.

Pain due to FAI is typically located in the groin area when the hip is fully flexed to 90°, adducted and internally rotated. During physical examination, a positive impingement test suggests FAI. The condition can cause damage to the labrum and chondrolabral junction and is believed to lead to osteoarthritis (OA) over time.2

Arthroscopic intervention for FAI is aimed at addressing the labral damage and obtaining clearance of movement by alleviating the abutment of the proximal femur against the acetabular rim.

In pincer-type impingement, the acetabular rim needs to be recessed.3 The labrum has to be detached before the rim is removed. Afterwards the labrum is re-attached.

Cam-type impingement can be treated by excision of the prominent area of the femoral head and neck. This is carried out without traction in order to flex the hip and relax the anterior capsule. A dynamic assessment can be performed arthroscopically to check whether enough bone is resected.

In the mixed type, both cam and pincer resection may be needed.

Results of FAI surgery

A range of studies has shown promising results in both cam and pincer FAI. There is no high quality evidence examining the effectiveness of surgery for FAI, as there are as yet no randomised clinical trials available.4 A limited number of studies have produced robust prospective data demonstrating a significant improvement in surgical outcome at two or more years. A recent review showed improved outcome between 82% and 94% after two years.5 Two long-term studies with a follow-up of longer than ten years are available. The first retrospectively reviewed 106 patients (111 hips).6 Conversion to total hip arthroplasty (THA) was defined as a failure. Survivorship among these hips was 63%. In this series, only the labral lesions were treated and the underlying osseous deformities were ignored during surgery. Favourable predictors of survivorship were Outerbridge grades I/II chondropathy. Femoral head cartilage damage was twice as likely to cause a failure than acetabular damage.

Another predictor of failure was advanced patient age. Patients over 40 years of age at arthroscopic surgery were 3.6 times more likely to require arthroplasty during the study period.

The second long-term study prospectively reviewed 50 patients (52 hips) with a ten-year follow-up.7 This study showed improvement after the first month. Results stabilised at three months, with a continued gradual improvement throughout the first year. Scores were maintained at two years but diminished slightly by the five-year follow-up. However, ten-year results approached those of the two-year level. Results were better in patients under 50 years of age whose symptoms had been present for less than 18 months. Additionally, it was found that the presence of arthritis at the time of arthroscopy was an indicator of poor prognosis.

Labral tears

Labral tears are usually associated with a typical presentation of groin pain, catching, clicking and locking.8 These tears can be traumatic in origin and are usually caused by a sudden pivoting or twisting action. But labral tears can also be caused by repetitive micro trauma due to FAI or can be associated with congenital or structural hip abnormalities such as Perthes' disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), developmental dysplasia of the hip and hypermobility.9 The functions of the labrum are to enhance stability, preserve congruity of the socket and prevent disruption of the sealing mechanism.10 The labrum is nearly avascular; however, there is vascularity on the capsular side.11 Labral tears frequently occur in the avascular articular zone and mostly fail to heal with conservative treatment.12

Labral tears can be perfectly assessed by arthroscopy and treated by excision and debridement of the torn portion back to a stable rim, or by repairing the tear. Resection can be achieved by using a shaver or radiofrequency probe. Because of the understanding of the functional importance of the labrum, the technique of repairing or reconstructing the labrum has gained popularity in the recent years. Labral repair can be performed by fixation using sutures or fibrin glue. Labral reconstruction techniques involving autografts have been described using the gracilis tendon, ligamentum teres or iliotibial band.13-15

Results of labral repair/debridement

A recent review reports a better outcome with labral repair compared with labral debridement.16 Six studies were included, all reporting that labral repair led to greater post-operative improvements in functional scores compared with labral debridement although high quality studies are lacking.

Another recent review identified 28 studies.17 Of these, 12 reported a mean rate of good results of 82% for labral debridement. Of the 16 studies that reported a combination of debridement and re-attachment, five reported a comparative outcome for the two methods; four reported better results with re-attachment and one study did not find any significant difference in outcomes. The authors advise only to repair the tears in a good quality labrum with a high potential to heal.

Chondral lesions

Management of injuries to the articular cartilage is challenging. Several causes of articular cartilage damage have been described, including trauma, labral tears, FAI, osteonecrosis, SCFE, dysplasia and degenerative arthritis.18 Most chondral lesions are found in the anterosu-perior quadrant of the acetabulum. A lesion starting at the chondrolabral junction has the potential to destabilise as the synovial fluid is pumped by the intra articular pressure underneath the cartilage rim, which can lead to delamination over time.19 Because articular cartilage has little capacity for healing, nonsurgical management options are limited. Arthroscopic surgical options include microfracture, articular cartilage repair and autologous chondrocyte or stem cell implantation.20

Results of interventions in chondral lesions

In a study in patients undergoing microfracture, at their second look by a mean follow-up of 17 months, 19 of 20 patients had a mean fill of 96% with macroscopically good quality repair tissue.21 Histologically, the tissue was found to be primarily fibrocartilage with some staining for type II collagen in the region closest to the bone.

In a recent study of 30 patients after receiving microfracture in the hip, 87% were classified as survivors.22 Changes in patient-related outcome measurements demonstrated statistically significant improvements from before surgery to the two-year follow-up. Two patients required THA and two patients required revision arthroscopy.

In a recent study there was a statistically significant improvement at a mean of 28 months after arthroscopic repair of delaminated acetabular articular cartilage with fibrin adhesive.23

In one study significant hip score improvements were measured over baseline levels at six months after surgery using a matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implant and autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis techniques.24

Osteoarthritis

For the arthroscopic treatment of OA, multiple treatment options are possible including removal of loose bodies, osteophyte resection and debridement of bony lesions of the acetabular rim or femoral head-neck junction. Osteochondral damage can be treated by microfracture and cartilage repair. However, the role of arthroscopy in the treatment and prevention of OA of the hip is controversial.

Results in osteoarthritis

McCarthy and Lee reported that debriding osteophytes or a degenerative labrum could help improve mechanical symptoms in patients with early OA.25 The results of systematic reviews reported significantly poorer clinical outcomes in degenerative hip joints.26,27

A review including 22 studies reported positive outcomes from hip arthroscopy in patients with OA, although patients with OA had inferior results compared with those who were free of the condition.28 The greater the severity of hip OA, and older age, each predicted a more rapid progression to THA.

Pre-operative radiographic joint space narrowing of greater than 50%, less than 2 mm of joint space remaining, or generalised intra-operative severe cartilage lesions portend high rates of arthroplasty within three years of hip arthroscopic surgery.29 In overview, the worse the articular cartilage damage, the worse the expected result after hip arthroscopy.

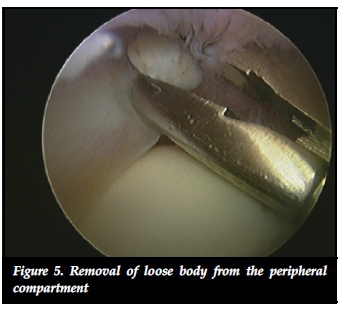

Loose bodies

Loose bodies are common findings at hip arthroscopy. Patients with loose bodies in the hip joint may present with catching or painful locking. Synovial chondro-matosis, Perthes' disease, osteochondritis dissecans and trauma are the usual conditions for developing loose bodies.30 Arthroscopy of the hip is a helpful tool to treat this problem as the loose bodies can be removed and synovial biopsy and/or synovectomy performed when a condition affecting the synovium is identified.

Results for loose body removal

In a study of 111 patients with a mean follow-up of 78.6 months, hip arthroscopy proved beneficial for patients diagnosed with primary synovial chondromatosis of the hip, providing good or excellent outcomes in 56.7% of the cases.31

In a recent review, 197 patients underwent hip arthroscopy for removal of intra-articular osteochondral fragments and synovectomy to alleviate both mechanical symptoms and pain.32 Follow-up periods ranged from one to 184 months. The recurrence rate was 7.1%. The authors concluded that for synovial chondromatosis of the hip, arthroscopic removal of osteo-chondral fragments with synovectomy is both safe and effective.

Hip instability/ ligamentum teres rupture

The bony acetabulum, labrum, joint capsule, ligamentous complex, and ligamentum teres, all contribute to the static stability of the hip joint. Injuries to these structures may result in joint instability.

A ruptured ligamentum teres can be a source of pain and locking.33 Ruptures have been classified and can be broadly acute due to a traumatic event or degenerative secondary to ongoing degeneration.34 The ligamentum teres has been reported to be capable of withstanding tensile loads similar to that of the anterior cruciate ligament and patients with subluxation of the hip may become dependent on the secondary restraint that is potentially provided by the ligamentum teres.35 Rupture of the ligamentum may thus cause symptomatic hip instability during athletic activities. Ligamentum rupture may lead to instability and subluxation of the hip, which may theoretically result in a higher incidence of degenerative change.36

Partial tears or an elongated ligament can be arthroscopically treated by radiofrequency thermal shrinkage. Arthroscopic debridement of the ligamentum remnant to prevent locking is possible when a complete tear is apparent. In addition ligamentum reconstruction is now technically possible and a number of different techniques have been described.37,38

Results in hip instability surgery

A recent review into the outcome of ligamentum debridement and reconstruction found nine level IV and V studies.39 These studies had a total of 87 patients (89 hips) who had undergone either arthroscopic debridement (81 patients, 83 hips) or reconstruction with autografting, allografting, or synthetic grafting (six patients) of a torn ligamentum teres. Patients were followed post-operatively for 1.5 to 60 months. Overall, both debridement and reconstruction improved the condition of patients, with a 40% increase in reported post-operative functional scores as well as a reported 89% of patients who were able to return to regular activity/sport.

Septic arthritis

As with so many other joints, when faced with possible infection, arthroscopic inspection, lavage, debridement, culture and biopsy of the hip is possible without the morbidity of an arthrotomy.40 Arthroscopic lavage and debridement is a safe and effective procedure for septic arthritis of the hip joint.41

Results in septic arthritis

A recent study shows that a two-portal hip arthroscopy with high-volume lavage is a safe and minimally invasive method in order to successfully treat septic arthritis of the hip and concomitant osteomyelitis of the femoral neck in children and adolescents.42 This technique leads to a very low morbidity and offers all the advantages of arthroscopic procedures.

Extra-articular lesions

Many indications for extra-articular hip endoscopy have been described.43 Peri-articular hip diseases, which are possible to address endoscopically, can be divided according to anatomical compartments involved.44

- Anterior to the hip joint: internal snapping hip syndrome, psoas tendon impingement, rectus femoris rupture or avulsion fracture and antero-inferior iliac spine impingement.

- Lateral to the hip joint: external snapping hip, trochanteric bursitis and gluteus medius tendinopathy.

- Posterior to the hip joint: piriformis syndrome, sciatic- or pudendal nerve entrapment and hamstring tendinopathy or rupture.

- Medial to the hip joint: ischiofemoral impingement.

Results in extra-articular lesions

Although the literature dealing with extra-articular hip endoscopy still shows poor scientific evidence - retrospective, single-surgeon case series and expert opinions currently make up the majority of reports available - a few are worth mentioning.45

Arthroscopic iliopsoas release appears to be successful and in case series there are higher success rates and less recurrence with the endoscopic technique compared with open procedures.46

External snapping of the hip can be operated endoscopically when conservative treatments fails. An endoscopic iliotibial band Z- or diamond-shaped release is performed.47 Where indicated, the additional treatment of a gluteus medius tear, excision of a trochanteric bone prominence or bursectomy may be performed. Good and excellent results of between 89% and 100% are reported in cohort studies.48

In most endoscopic extra-articular hip operations no direct comparison is available between open and endoscopic surgery. However, endoscopic surgery offers a safe option with minimum morbidity and low risk of complications.

Prosthetic hip

Arthroscopy has been shown to be effective in evaluating and treating problems after THA.49 Possible interventions are: adhesiolysis, capsulotomy, obtaining cultures/tissue samples, detecting loosening of components and removal of loose bodies, cement or debris.

Results in prosthetic hip endoscopy

In a study of 16 patients with a painful THA, hip arthroscopy was beneficial in 12 of 16 cases (75%) and it did not cause any complications.50 In another clinical series of patients with residual groin pain after THA, in nine patients, endoscopic iliopsoas tenotomy through the trans-capsular approach was performed.51 None of the patients had anterior cup overhang as this was considered a contraindication prior to surgery. At a mean follow-up of 11 months all patients showed improvement and no complications were reported.

Another study presents the outcome of arthroscopy after hip resurfacing arthroplasty in 15 cases.52 Arthroscopy was beneficial in cases of unexplained residual groin pain. Infection or an adverse reaction to metal debris was found in seven of 15 cases.

A recent report compared arthroscopy of painful post-arthroplasty hips with painful, native hips.53 Each study arm comprised 24 patients. For the post-arthroplasty cases, arthroscopy aided in confirming the diagnosis in 96% of the cases, and was also therapeutically successful in 43%. In the native hips, the diagnosis was confirmed and a therapeutic procedure performed in all of the cases. This provided relief of symptoms in 87%.

What to tell your patient

Hip arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure that can address many morbidities of the hip joint and its surrounding structures. The technique is still evolving and high quality studies of most of the procedures are still lacking. The results of arthroscopic treatment for patients with FAI are very promising but whether or not hip arthroscopic surgery can limit the progression to OA remains to be seen.

Poor prognostic factors for arthroscopic surgery is advanced degenerative changes. Some studies say that increased patient age is a poor prognostic factor, but not all studies support that conclusion.54,55 Of these, the degree of degenerative cartilage damage seems to be the most important factor of post-operative outcome. The greater the degree of chondral damage, the worse the likely end result.

So what should one tell a patient about the likely end result if hip arthroscopic surgery is a possibility? It is certainly feasible to give guidance based on pre-operative history, examination and imaging but so often hip arthroscopy will identify previously undiagnosed lesions, so it is difficult to be precise when it comes to offering a likely outcome to a patient.

Complications associated with hip arthroscopy do certainly exist, although their prevalence has not been shown to be greatly different to arthroscopy of other joints. Nevertheless, we believe it is right that in every case a patient is warned that hip arthroscopy does stand a chance of exacerbating the situation rather than improving it.

As a consequence, in our practice we try to keep such advice simple. For a patient without radiographic evidence of OA, we advise that one year after surgery there is an 80% chance of success, a 15% chance of making no difference and a 5% chance of making matters worse.

For a patient with significant OA on plain radiographs (e.g. Tönnis grade 2 and 3) we advise that there is a 40% chance of improving their symptoms at one year, a 45% chance of making no difference at all and a 15% chance of making matters worse.

For patients between these two extremes, the figures (Tönnis grade 1) we offer are a best-shot estimate. That is, there is a 70% chance of success, a 20% chance of making no difference and a 10% chance we can make matters worse.

Conclusions

Hip arthroscopy has clearly developed enormously over the past 20 years changing from a procedure undertaken by a few to one that is now practised by many. Indications are expanding, techniques are developing and, in tandem, clinical and laboratory studies are being widely undertaken. The procedure's future is unquestionably bright. What remains unchanged over time, however, is that patients need to be properly and reliably informed.

Conflict of interest statement

No benefits of any form have been received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

1. Crawford JR, Villar RN. Current concepts in the management of femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2005;87-B:1459-62. [ Links ]

2. Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2005;87-B:1012-18. [ Links ]

3. Lavigne M, Parvizi J, Beck M, Siebenrock KA, Ganz R, Leunig M. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement. Part I: techniques of joint preserving surgery. Clin Orthop 2004;418:61-66. [ Links ]

4. Wall PD, Brown JS, Parsons N, Buchbinder R, Costa ML, Griffin D. Surgery for treating hip impingement (femoroacetabular impingement). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 8;9. [ Links ]

5. MacFarlane RJ, Konan S, El-Huseinny M, Haddad FS. A review of outcomes of the surgical management of femoroacetabular impingement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014 Jul;96(5):331-38. [ Links ]

6. McCarthy JC, Jarrett BT, Ojeifo O, Lee JA, Bragdon CR. What factors influence long-term survivorship after hip arthroscopy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(2):362-71. [ Links ]

7. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 10-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):741-46. [ Links ]

8. Byrd JW. Labral lesions: an elusive source of hip pain case reports and literature review. Arthroscopy 1996;12:603-12. [ Links ]

9. McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, Lee J. The role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop 2001;393:25-37. [ Links ]

10. Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K. An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech 2003;36:171-78. [ Links ]

11. Seldes RM, Tan V, Hunt J, et al. Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop 2001;382:232-40. [ Links ]

12. McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, Lee J. The role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop 2001;393:25-37. [ Links ]

13. Matsuda DK. Arthroscopic labral reconstruction with gracilis autograft. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1(1):e15-e21. [ Links ]

14. Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT. Labral reconstruction using the ligamentum teres capitis: report of a new technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):753-59. [ Links ]

15. Philippon MJ, Briggs KK, Yen YM, Kuppersmith DA. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement with associated chondrolabral dysfunction: minimum two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(1):16-23. [ Links ]

16. Ayeni OR, Adamich J, Farrokhyar F, Simunovic N, Crouch S, Philippon MJ, Bhandari M. Surgical management of labral tears during femoroacetabular impingement surgery: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Apr;22(4):756-62. [ Links ]

17. Haddad B, Konan S, Haddad FS. Debridement versus re-attachment of acetabular labral tears: A review of the literature and quantitative analysis. Bone Joint J. 2014 Jan;96-B(1):24-30. [ Links ]

18. Diulis CA, Krebs VE, Hanna G, Barsoum WK. Hip arthroscopy technique and indications. J Arthroplasty 2006;21(4 Suppl 1):68-73. [ Links ]

19. McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, Lee J. The watershed labral lesion: its relationship to early arthritis of the hip. J Arthroplasty 2001;16(Suppl 1):81-87. [ Links ]

20. El Bitar YF, Lindner D, Jackson TJ, Domb BG. Joint preserving surgical options for management of chondral injuries of the hip. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014 Jan;22(1):46-56. [ Links ]

21. Karthikeyan S, Roberts S, Griffin D. Microfracture for acetabular chondral defects in patients with femoroacetabular impingement: results at second-look arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Dec;40(12):2725-30. [ Links ]

22. Domb BG, El Bitar YF, Lindner D, Jackson TJ, Stake CE. Arthroscopic hip surgery with a microfracture procedure of the hip: clinical outcomes with two-year follow-up. Hip Int. 2014 Sep 26;24(5):448-56. [ Links ]

23. Stafford GH, Bunn JR, Villar RN. Arthroscopic repair of delaminated acetabular articular cartilage using fibrin adhesive. Results at one to three years. Hip Int. 2011 Nov-Dec;21(6):744-50. [ Links ]

24. Mancini D, Fontana A. Five-year results of arthroscopic techniques for the treatment of acetabular chondral lesions in femoroacetabular impingement. Int Orthop. 2014 Oct;38(10):2057-64. [ Links ]

25. McCarthy JC, Lee JA: Arthroscopic intervention in early hip disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004 Dec;(429):157-62. [ Links ]

26. Clohisy JC, St John LC, Schutz AL. Surgical treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010 Feb;468(2):555-64. [ Links ]

27. Ng VY, Arora N, Best TM, Pan X, Ellis TJ. Efficacy of surgery for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2010 Nov;38(11):2337-45. [ Links ]

28. Kemp JL, MacDonald D, Collins NJ, Hatton AL, Crossley KM. Hip Arthroscopy in the Setting of Hip Osteoarthritis: Systematic Review of Outcomes and Progression to Hip Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Sep 18. [ Links ]

29. Lynch TS, Terry MA, Bedi A, Kelly BT. Hip arthroscopic surgery: patient evaluation, current indications, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2013 May;41(5):1174-89. [ Links ]

30. Krebs VE. The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of synovial disorders and loose bodies. Clin Orthop 2003;406:48-59. [ Links ]

31. Boyer T, Dorfmann H. Arthroscopy in primary synovial chondromatosis of the hip: description and outcome of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008 Mar;90(3):314-18. [ Links ]

32. de Sa D, Horner NS, MacDonald A, Simunovic N, Ghert MA, Philippon MJ, Ayeni OR. Arthroscopic Surgery for Synovial Chondromatosis of the Hip: A Systematic Review of Rates and Predisposing Factors for Recurrence. Arthroscopy. 2014 Nov;30(11):1499-1504.e2. [ Links ]

33. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Traumatic rupture of the ligamentum teres as a source of hip pain. Arthroscopy 2004;20:385-91. [ Links ]

34. Gray AJ, Villar RN. The ligamentum teres of the hip: an arthroscopic classification of its pathology. Arthroscopy 1997;13:575-78. [ Links ]

35. Philippon MJ, Pennock A, Gaskill TR. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the ligamentum teres: technique and early outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Nov;94(11):1494-98. [ Links ]

36. Rao J, Zhou YX, Villar RN. Injury to the ligamentum teres: mechanism, findings, and results of treatment. Clin Sports Med 2001;20:791-99. [ Links ]

37. de Sa D, Phillips M, Philippon MJ, Letkemann S, Simunovic N, Ayeni OR. Ligamentum Teres Injuries of the Hip: A Systematic Review Examining Surgical Indications, Treatment Options, and Outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2014 Dec;30(12):1634-41. [ Links ]

38. Simpson JM, Field RE, Villar RN. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the ligamentum teres. Arthroscopy. 2011 Mar;27(3):436-41. [ Links ]

39. de Sa D, Phillips M, Philippon MJ, Letkemann S, Simunovic N, Ayeni OR. Ligamentum Teres Injuries of the Hip: A Systematic Review Examining Surgical Indications, Treatment Options, and Outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2014 Dec;30(12):1634-41. [ Links ]

40. Bould M, Edwards D, Villar RN. Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis of the hip joint. Arthroscopy 1993;9:707-708. [ Links ]

41. Lee YK, Park KS, Ha YC, Koo KH. Arthroscopic treatment for acute septic arthritis of the hip joint in adults. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Apr;22(4):942-45. [ Links ]

42. Fernandez FF, Langendörfer M, Wirth T, Eberhardt O. Treatment of septic arthritis of the hip in children and adolescents. Z Orthop Unfall. 2013 Dec;151(6):596-602. [ Links ]

43. Verhelst L, Guevara V, De Schepper J, Van Melkebeek J, Pattyn C, Audenaert EA. Extra-articular hip endoscopy: A review of the literature. Bone Joint Res. 2012 Dec 1;1(12):324-32. [ Links ]

44. Aprato A, Jayasekera N, Bajwa A, Villar RN. Peri-articular diseases of the hip: emerging frontiers in arthroscopic and endoscopic treatments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014 Mar;15(1):1-11. [ Links ]

45. Verhelst L, Guevara V, De Schepper J, Van Melkebeek J, Pattyn C, Audenaert EA. Extra-articular hip endoscopy: A review of the literature. Bone Joint Res. 2012 Dec 1;1(12):324-32. [ Links ]

46. Aprato A, Jayasekera N, Bajwa A, Villar RN. Peri-articular diseases of the hip: emerging frontiers in arthroscopic and endoscopic treatments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014 Mar;15(1):1-11. [ Links ]

47. Ilizaliturri VM Jr, Martinez-Escalante FA, Chaidez PA, Camacho-Galindo J. Endoscopic iliotibial band release for external snapping hip syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2006 May; 22(5):505-10. [ Links ]

48. Aprato A, Jayasekera N, Bajwa A, Villar RN. Peri-articular diseases of the hip: emerging frontiers in arthroscopic and endoscopic treatments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014 Mar;15(1):1-11. [ Links ]

49. Lahner M, von Schulze Pellengahr C, Lichtinger TK, Vetter G, Pesendorfer SH, Hagen M, Daniilidis K, von Engelhardt LV, Teske W. The role of arthroscopy in patients with persistent hip pain after total hip arthroplasty. Technol Health Care. 2013;21(6):599-606. [ Links ]

50. McCarthy JC, Jibodh SR, Lee JA. The role of arthroscopy in evaluation of painful hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:174-80. [ Links ]

51. Van Riet A, De Schepper J, Delport HP. Arthroscopic psoas release for iliopsoas impingement after total hip replacement. Acta Orthop Belg 2011;77:41-46. [ Links ]

52. Pattyn C, Verdonk R, Audenaert E. Hip arthroscopy in patients with painful hip following resurfacing arthro-plasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:1514-20. [ Links ]

53. Bajwa AS, Villar RN. Arthroscopy of the hip in patients following joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2011;93-B:890-96. [ Links ]

54. Haviv B, O'Donnell J. The incidence of total hip arthroplasty after hip arthroscopy in osteoarthritic patients. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010 Jul 29;2:18. [ Links ]

55. Javed A, O'Donnell JM. Arthroscopic femoral osteochondroplasty for cam femoroacetabular impingement in patients over 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Mar;93(3):326-31. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Jorm Nellensteijn

Rose Cottage, Royal Oak lane Hemingford Abbots

PE289AF, Cambridgeshire, UK

+447507935375

jmnellensteijn@hotmail.com