Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versão impressa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.14 no.4 Centurion Out./Nov. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2015/v14n4a7

FOOT AND ANKLE

Achilles tendinopathy Part 2: Surgical management

Dr A HornI; Dr GA McCollumII

IMBChB(Pret); Registrar, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town

IIMBChB(UCT), FCOrth(SA), MMed(UCT); Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Although non-surgical management is the mainstay of treatment for non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy, many patients fail to respond to conservative measures. If symptoms persist after an extended period of conservative management, usually at least six months, surgery should be considered. Classically, open surgery was performed with excision of the diseased areas of the tendon. Due to a high rate of complications, as much as 10%, less invasive surgical techniques have been developed and are widely employed with good surgical outcomes and far fewer complications. The reported success rates of open and minimally invasive surgery are comparable and range from 46-100%. Considering the significant morbidity associated with open surgery, minimally invasive surgery is recommended as initial intervention, followed by open surgery if symptoms persist.

Key words: Achilles tendinopathy, main body, surgery, minimally invasive surgery, tendon

Introduction

Tendinopathy of the main body of the Achilles tendon is a common condition affecting both athletes and the sedentary population. The aetiology of this painful condition is largely unknown and exhaustive research has elucidated numerous and complex contributing intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The diagnosis is clinical, although imaging modalities such as MRI and ultrasound are useful in confirming the diagnosis in cases of clinical equipoise. Conservative management, mostly involving an eccentric exercise regimen, is the mainstay of treatment. The various conservative treatment modalities, as well as the aetiology, pathology and diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy is discussed in Part 1 of this review (see SA Orthopaedic Journal, Spring 2015 Vol 14 No 3). This article will focus exclusively on the surgical treatment of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy.

Conservative management, mostly involving an eccentric exercise regimen, is the mainstay of treatment

Some 24-45.5% of patients suffering from Achilles tendinopathy will not respond to conservative management and will require surgical intervention.1-6 Surgery should be considered only once conservative means have been exhausted and the patient failed to improve or comply with a supervised rehabilitation programme.

The goal of surgery is to modulate the cell-matrix environment in such a way that healing is promoted by improving vascularity and stimulating the remaining viable cells to regenerate.4 This was classically achieved by excision of fibrotic peritendinous adhesions and intratendinous degenerate nodules.

More recently, attention has shifted towards disrupting the pathological peritendinous neoneurovas-cularisation that has been shown to be intimately related to the severity of the disease.7 The recent development of minimally invasive techniques has decreased the high complication rates seen with open surgery and shows promising results, although some authors express a concern regarding higher risk for certain complications such as sural nerve damage.8 The rehabilitation period is also much reduced with the use of minimally invasive procedures.

Open surgical management of Achilles tendinopathy

Open tenotomy with excision of fibrotic adhesions and degenerate intratendinous lesions

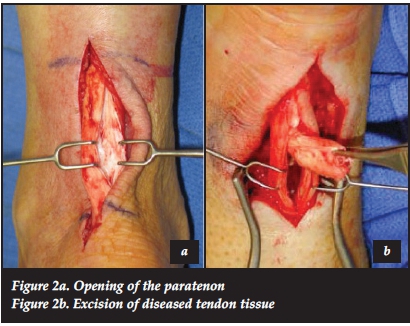

The patient is positioned prone and the tendon is approached through an incision medial to the medial border of the tendon to avoid damage to the sural nerve and vein. The paratenon is identified and incised. If there are dense, fibrotic adhesions found within the paratenon, these are excised leaving as many layers of normal paratenon intact as possible.9 Care must be taken to avoid the anterior surface of the tendon lying adjacent to Kager's fat pad, as the majority of the tendon's blood supply is believed to originate here.10 Pre-operative imaging can guide the surgeon as to the location of any intratendinous lesions; alternatively two to three longitudinal tenotomies are made to identify areas of degeneration. These areas will lack the usual shiny appearance of normal tendon tissue and would have an appearance resembling 'crab meat' (Figure 1).6 These degenerate nodules are sharply excised and the defect repaired by end-to-end suturing (Figure 2a and 2b). If the defect exceeds 50% of the surface area of the tendon, consideration should be given to one of various augmentation procedures:4

1) A tendon turndown flap can be fashioned by dissecting out one or two strips of Achilles tendon proximally at the musculotendinous junction. These strips are developed proximally but left attached distally and flipped 180 degrees to bridge the gap formed by the excised nodules.6

2) The plantaris tendon, found on the medial aspect of the tendo Achilles, may be used, either as a free graft or left attached distally to augment the tendon defect.6

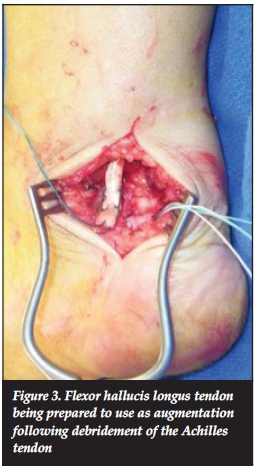

3) The flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon may be used in various ways to augment the degenerate Achilles tendon (Figure 3). Several studies have shown good to excellent outcomes in patients over 50 years of age with FHL tendon transfers for the treatment of insertional and non-insertional tendinopathy, as well as tendon ruptures.11-13

4) The peroneus brevis14 or flexor digitorum5 tendons have also been used as autologous graft to repair and augment the Achilles tendon after debridement.

Pre-operative imaging can guide the surgeon as to the location of any intratendinous lesions; alternatively two to three longitudinal tenotomies are made to identify areas of degeneration

Post-operatively, the patient is kept non-weightbearing for 2 weeks, or 6 weeks if a tendon transfer has been performed. Weight bearing is initially protected in a boot or walking cast. Range of motion and strengthening exercises are initiated at 4-6 weeks and return to activity is allowed when strength has been regained, usually 4-6 months after surgery.10

Reported success rates following open surgery of the Achilles tendon range from 46%-100%.4,5,10,15, 16 In a critical review by Talon et al.5assessing 26 published papers, there was a negative correlation between study methodology and good outcomes, which partially explains the discrepancy between the favourable results published in the literature and those which are observed in clinical practice.

Reported success rates following open surgery of the Achilles tendon range from 46%-100%

In one 7-month prospective follow-up study evaluating 42 patients who had open surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy, 67% of patients had returned to their previous level of activity and 83% of patients were asymptomatic. It was also noted that those patients who had intratendinous lesions fared worse that those who had isolated paratendinopathy.17 Alfredson et al. followed up 14 patients, eight years after they had undergone surgery for Achilles tendinopathy. All patients were satisfied with the outcome and experienced no activity restriction. Ultrasound investigation revealed persistence of structural tendon abnormalities, as well as an increase in tendon thickness.18

Saxena reviewed 27 athletes who had a variety of surgical procedures for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Elite athletes returned to their previous sporting activities in 7.9 ± 4.8 weeks and non-elite athletes in 15.0 ± 6.2 weeks. Three patients in this series required re-operation.19 Maffulli, in an age-matched series comparing men and women, found that women had significantly worse outcomes following surgery and were far less likely to return to their previous level of activity, regardless of whether or not they were physically active prior to surgery.20

The complication rate for open Achilles tendon surgery is reported to be as high as 10%, with 25% of these being major complications.9 (Major and minor complications are listed in Table I.) Risk factors for developing complications are increased age, pre-operative steroid injections, poor attention to haemostasis intra-operatively, undermining of the skin edges and excessive stripping of the paratenon.9,17

Gastrocnemius recession

The concept of gastrocnemius lengthening for the treatment of resistant Achilles tendinopathy was first suggested by Duthon et al.21in 2003. This was based on the premise that a contracted Achilles tendon leads to altered biomechanics in the hindfoot and is a well-known aetio-logical factor for the development of Achilles tendinopathy. They performed a gastrocnemius recession as described by Strayer22 on 17 tendons in 14 patients who demonstrated gastrocnemius contracture pre-operatively, as evidenced by a positive Silfverskiold test.23 All but one patient were satisfied with the outcome of surgery, and 11 of the 14 could return to their previous sporting level. MRI following surgery demonstrated reduction in size and number of hyperintense lesions and tendon thickness, signifying an improvement of the tendinopathy. There were no surgical complications in this series.

Kiewiet et al.11performed this procedure for 12 patients with contracted Achilles tendons and chronic tendinopathy. All patients had significantly improved AOFAS hindfoot scores (range 75-100) and only one patient had persistent pain. There were no complications in this series.

Percutaneous surgical techniques

Percutaneous tenotomy

This technique was first described by Maffulli et al.8in the early 1990s. The patient is positioned prone with the feet hanging over the edge of the operating table. General or local anaesthesia may be used. The area of maximal swelling is identified, and ultrasound may be used if the lesions are not clinically obvious. A stab incision is made in the middle of the tendon with a size 11 blade, cutting edge pointing caudally. The ankle is then moved through a full range of plantar- and dorsiflexion. The blade is then partially extracted and rotated 180 degrees so that the cutting edge points cranially and the ankle is again moved through a full range of plantar- and dorsiflexion. Cadaver studies have shown the resultant longitudinal tenotomy to be approximately 3 cm in length. This procedure is then repeated through stab wounds placed proximally and distally medial and lateral to the original stab wound so that the pattern resembles the number 5 on a die. Post-operatively the patient is allowed full weight bearing with or without a boot and physiotherapy is begun at 2 weeks following surgery.

The same group that described this procedure published the outcomes of 63 athletes who underwent percutaneous tenotomy for recalcitrant Achilles tendinopathy. Forty-seven of the patients reported good to excellent results. Nine patients with fair or poor results underwent formal exploration and debridement of the affected tendon 7-12 months after the index operation. Poorer results were associated with pan tendinopathy, multiple steroid injections pre-operatively and poor compliance with the prescribed rehabilitation protocol.25 The authors concluded that percutaneous tenotomy is a good surgical option for resistant Achilles tendinopathy, but patients should be aware that in the case of multinodular disease and extensive paratenon disease, open surgery will be required.

Minimally invasive stripping of the paratenon

This technique was first described by Maffuli et al? in 2008 but no published review of outcomes for this technique exists at present. The procedure is performed through four stab incisions, two proximally and two distally, on either side of the tendon. A size 1 suture is passed through the two proximal incisions ventral to the tendon and then extracted distally through the two distal incisions. The suture is then pulled distally with a see-saw motion, effectively freeing the tendon from the surrounding paratenon and disrupting neovascularisation. The procedure is repeated with the suture passed along the dorsal surface of the tendon. This can be combined with percutaneous tenotomies. The rationale for this procedure is based on the fact that numerous studies have shown a direct relation between neovascularisation and pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy.1-6,26-27

Achilles tendoscopy

Endoscopic surgery for the disorders of the Achilles tendon has been practised since the beginning of the century as an alternative to open surgery, in the hope of reducing c omplications seen with open procedures.27 The goal of Achilles tendoscopy is to release fibrous adhesions around the tendon and paratenon, to strip pathological neovascu-larisation of the ventral surface of the tendon and to release the plantaris tendon.27-28 It has recently been suggested that a thickened, adherent plantaris tendon might be causative, or at least contributory in the development of mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy.29-31 The tendoscopy can be performed through a proximal medial and distal lateral portal, or through two medial portals, using a 2.7 mm scope. Care is taken to avoid damage to the neurovascular structures by staying on the surface of the tendon at all times. The endoscopic release can be combined with longitudinal tenotomies if intratendinous pathology is also present.

Preliminary results using this method are promising. Steenstra et al. reported on 20 patients who underwent paratenon release only. All patients experienced pain relief and improved hindfoot scores, and most were able to return to sporting activities within 4-6 weeks.32 A few other small studies assessing outcomes following tendoscopy, with and without tenotomy, also reported good to excellent outcomes in all patients, return to previous level of activity and no complications.28-33-34

Conclusion

The mainstay of treatment of Achilles tendinopathy is nonoperative management but for those patients who fail to respond to such measures- surgical treatment remains a feasible option. There have been many promising developments in the field of surgical management for chronic Achilles tendinopathy with encouraging preliminary outcomes. Extensive intratendinous disease requires open surgery with excision of the degenerate intratendinous lesions- and augmentation with tendon transfers if more than 50% of the width of the tendon has been excised. Newer- minimally invasive surgeries- such as percutaneous tenotomies- are effective in treating less extensive disease and pose an attractive alternative to the classic open surgery in terms of complications and accelerated rehabilitation. Current evidence is however limited to small series with short follow-up. Further large prospective studies are needed to define the role of novel surgical techniques in the management of this complex condition.

Minimally invasive stripping of the paratenon was first described by Maffuli et al.8 in 2008 but no published review of outcomes for this technique exists at present

References

1. Paavola M, Kannus P, Järvinen TAH et al. Achilles tendinopathy: Current concepts review. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]2002; [ Links ]84-A(11):2062-75.

2. Paavola M, Kannus P, Paakkala T, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with Achilles tendinopathy: an obser vational 8-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2000;28(5):634-42. [ Links ]

3. Maffulli N, Binfield PM, Moore D, King JB. Surgical decompression of chronic central core lesions of the Achilles tendon. Am J Sports Med 1999;27(6):747-52. [ Links ]

4. Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J. Management of tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2009;37(9):1855-67. [ Links ]

5. Talon C, Coleman B, Khan M, et al. Outcomes of surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. A critical review. Am J Sports Med 2001;29(3):315-20. [ Links ]

6. Longo UG, Ronga M, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2009;17:112-26. [ Links ]

7. Longo UG, Ramamurthy C, Denaro V, et al. Minimally invasive stripping for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2008;30(20-22):1709-13. [ Links ]

8. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Francesco O, et al. Minimally invasive surgery of the Achilles tendon. Orthop Clin N Am 2009;40:491-98. [ Links ]

9. Paavola M, Orava S, Leppilahti J, et al. Chronic Achilles tendon overuse injury: complications after surgical treatment. Am J Sports Med 2000;28(1):77-82. [ Links ]

10. Heckman DS, Gluck GS, Parekh SG. Tendon disorders of the foot and ankle, Part 2: Achilles tendon disorders. Am J Sports Med 2009;36(6):1223-33. [ Links ]

11. Den Hartog BD. flexor hallucis longus transfer for chronic Achilles tendonosis. Foot Ankle Int 2003;24:233-38. [ Links ]

12. Hahn F, Meyer P, Maiwald C, et al. Treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy and ruptures with flexor hallucis tendon transfer: clinical outcome and MRI findings. Foot Ankle Int 2008;28:294-304. [ Links ]

13. Wilcox DK, Bohay DR, Anderson JG. Treatment of chronic achilles tendon disorders with flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer/augmentation. Foot Ankle Int 2000;21:2004-11. [ Links ]

14. Pintore E, Barra V, Pintore R, et al. Peroneus brevis tendon transfer in neglected tears of the Achilles tendon. J Trauma 2001;50:71-78. [ Links ]

15. Schepsis AA, Wagner C, Leach RE. Surgical management of Achilles tendon overuse injuries: A long-term follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 1994;22:611-19. [ Links ]

16. Vulpiani MC, Guzzini M, Ferretti A. Operative treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Int Orthop 2003;27:307-10. [ Links ]

17. Paavola M, Kannus P, Orava S, et al. Surgical treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a prospective seven-month follow-up study. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:178-82. [ Links ]

18. Alfredson H, Zeisig A, Fahlström M. No normalisation of tendon structure and thickness after intratendinous surgery for chronic painful midportion Achilles tendinosis. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:948-49. [ Links ]

19. Saxena A. Results of chronic Achilles tendinopathy surgery on elite and non-elite track athletes. Foot Ankle Int 2003;24:712-20. [ Links ]

20. Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G, et al. Surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy produces worse results in women. Disability and Rehabilitation 2008;30(20-22):1714-20. [ Links ]

21. Duthon VB, Lubbeke A, Duc SR. Noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy treated with gastrocnemius lengthening. Foot Ankle Int 2011;32:375-80. [ Links ]

22. Strayer LM.Recession of the gastrocnemicus. J Bone Joint Surg(Am) 1950;32:671. [ Links ]

23. Silvferskiold N. Reduction of the uncrossed two-joint muscles of the leg to one-joint muscles in spastic conditions. Acta Chir Scand 1924;56:315-30. [ Links ]

24. Kiewiet NJ, Holthusen SM, Bohay DR. Gastrocnemius recession for chronic noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34:481-86. [ Links ]

25. Testa V, Capasso G, Benazzo F, et al. Management of Achilles tendinopathy by ultrasound-guided percutaneous tenotomy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34(4):573-80. [ Links ]

26. Zanetti M, Metxdorf A, Kundert H, et al. Achilles tendons: clinical relevance of neovascularisation diagnosed with power Doppler US. Radiology 2003;227(2):556-60. [ Links ]

27. Roche AJ, Calder JDF. Achilles tendinopathy. A review of current concepts of treatment. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:1299-07. [ Links ]

28. Maqquirriain J, Ayerza M, Costa M, et al. Endoscopic surgery in chronic Achilles tendonopathies: A preliminary report. Arthroscopy 2002;18:298-303. [ Links ]

29. Van Sterkenburg MN, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Kleippol RP, et al. The plantaris tendon and a potential role in mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: an observational anatomical study. Journ Anat 2011;218(3):336-41. [ Links ]

30. Van Sterkenburg MN, van Dijk CN. Mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: why painful? An evidence-based philosophy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19(8):1367-75. [ Links ]

31. Alfredson H. Midportion Achilles tendinosis and the plantaris tendon. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1023-25. [ Links ]

32. Steenstra F, van Dijk CN. Achilles Tendoscopy. Foot Ankle Clin 2006;11:429-38. [ Links ]

33. Vega J, Cabestany JM, Golano P, et al. Endoscopic treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Clin 2008;14:204-10. [ Links ]

34. Therman H, Benestos IS, Panelli C, et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: novel technique with short term results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2009;17:1264-69. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Anria Horn

Postnet Suite 342 Private Bag X18

Rondebosch 7701 , Cape Town

Cell: 071 679 4228 Work: 021 404 5108

Email: anriahorn@gmail.com

Declaration: The content of this article is the sole work of the authors. No benefits of any form have been or are to be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.