Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309

Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.12 n.4 Centurion Dec. 2013

HIP

Is there a role for prolonged post-operative antibiotic use in primary total hip arthroplasty in the African setting?

JWM KigeraI; LN GakuoII

IMBChB, MMed Director of Clinical Services, Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Unit, PCEA Kikuyu Hospital, Kikuyu, Kenya

IIAssociate Professor of Orthopaedics, Department of Orthopaedics, College of Health Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The use of prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI) is recommended for up to 24 hours post-operatively. Surgeons in Africa have been using antibiotics for prolonged periods of time because of perceived higher infection rates. We conducted a study to determine the incidence of early post-operative SSI and to determine if the use of antibiotics beyond 24 hours post-operatively resulted in any difference in this incidence after primary total hip arthroplasties.

METHODS: A retrospective cohort study was conducted of all primary total hip arthroplasties done from 1998 to 2011. Patients had a prophylactic administered 30-60 minutes prior to surgical incision and the post-operative antibiotic regime was surgeon-dependent. The study was approved by the hospital Ethics Committee.

RESULTS: The overall incidence of post-operative SSI was 1.5%. The duration of prophylactic antibiotic use among patients who were not treated for an SSI averaged 3.39 days (SD 7.496) and ranged from 0 to 65 days. There was no statistical difference in the incidence of post-operative SSI in patients who received prophylactic antibiotics for up to 24 hours (1.4%) and in patients who received antibiotics for longer than 24 hours (2%) (p=0.706).

CONCLUSION: The risk of post-operative SSI after total hip arthroplasties is low. There is no evidence to support the use of prophylactic antibiotics for longer than 24 hours even in the African setting.

Key words: post-operative, surgical site infection, arthroplasty, primary total hip

Introduction

Any surgery is associated with a risk of post-operative surgical site infection (SSI). Various measures have been put in place to mitigate this risk. With modern surgical techniques and the use of prophylactic antibiotics, the risk of post-operative SSIs is as low as 2%.1-3 Various American and European protocols advocate the initiation of prophylactic antibiotics within one hour of the incision and continued up to 24 hours after the end of the operation4-6

In the absence of similar protocols in the African setting, it has been left to individual hospitals and surgeons to determine the duration of prophylactic antibiotic use.

Due to the less than ideal circumstances under which primary joint arthroplasty is conducted in Africa, there is a tendency to believe that the risk of post-operative SSIs would be higher. This has led to the common practice of using prophylactic antibiotics for longer than is recommended by protocols. This is done without any clinical or microbiological evidence of infection and the surgeon perceives it to be 'prophylaxis'.

We conducted a study to determine the incidence of early (within 30 days) post-operative SSI and to determine if the use of antibiotics beyond 24 hours post-operatively resulted in any difference in this incidence after primary total hip arthroplasties.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted of all primary total hip arthroplasties conducted at our hospital's orthopaedic unit from 1998 to 2011. Our hospital is the premier orthopaedic unit in the country and is located about 20 km from the capital city. It also serves as a teaching hospital for the orthopaedic residency programme of the local university and the College of Surgeons of East Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA). All patients undergoing a total hip arthroplasty had an intravenous antibiotic 30-60 minutes prior to surgical incision and the surgeries were conducted by several orthopaedic surgeons of varying levels of experience. There were no fellowship-trained surgeons at our centre. The post-operative medication was varied and depended on individual surgeons. We determined the duration of use of antibiotics and the drugs used. In all cases the Hardinge lateral approach was used and patients were mobilised from the first post-operative day. Patients were deemed to have acute infection if any of the following were noted in the first 30 days post-operatively: any wound discharge after the fifth post-operative day, purulent wound discharge at any time or a sinus at the operation site. Patients were also investigated for the presence of infection if any of the following were noted: local signs of inflammation at the surgical site (increased pain on joint movement, oedema or induration), or systemic signs of infection (e.g. fever). The investigations conducted varied depending on the primary physician. Wound pus swabs with culture and sensitivity were not routinely performed. The data analysis was done using SPSS ver17.0 (IBM corp. New York, USA). The study was approved by the institution's Ethics Committee which determined that written consent was not required as it was a retrospective study, and they waived the need for written consent. There were 666 primary total hip arthroplasties in the 14-year period.

In Africa, there is a tendency to use prophylactic

antibiotics for longer than is recommended by protocols

Results

The male:female ratio was 1:2 and the mean age was 63 years (SD 10.4). The majority of the implants (96.4%) used were cemented using cement impregnated with an antibiotic (2 g gentamycin in every 40 g of cement). A variety of implants was used with the three most common implants being De Puy (70%), Biomechanica (10%) and Tournier (10%).

There were ten cases of early post-operative SSIs, giving an overall incidence of 1.5%.

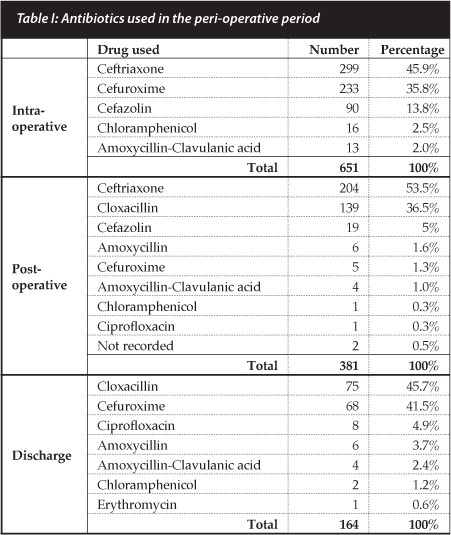

The duration of prophylactic antibiotic use among patients who were not treated for an SSI averaged 3.39 days (SD 7.496) and ranged from 0-65 days with 152 patients receiving antibiotics for longer than three days. Ceftriaxone was the commonest drug used in the intra-operative and post-operative period while cloxacillin was the most frequently used antibiotic used after the patient had been discharged from hospital (Table I).

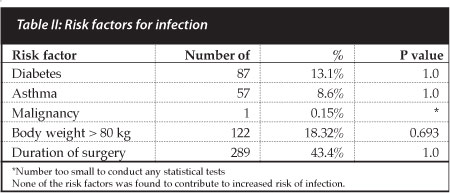

We tried to determine any co-morbidities that may be risk factors for the development of SSIs. We also tried to determine if the duration of surgery and body weight were associated with increased risk of SSI. Table II shows the risk factors and the number of patients affected. None of the risk factors identified was found to be associated with the development of SSI.

Of 666 primary total hip arthroplasties done, 11 patients did not have sufficient data for the evaluation of infection and antibiotic use leaving 655 patients who were include in this analysis. There were seven cases of infection among the 502 patients who received prophylactic antibiotics for up to 24 hours, giving the incidence of post-operative SSI of 1.4%. In patients who received antibiotics for longer than 24 hours, there were three cases of post-operative SSI among 153 patients giving an incidence of 2%. There was no statistical difference between the two groups (p=0.706).

Discussion

The mean duration of antibiotic use was about three days and the incidence of post-operative SSI was 1.5%. There is no difference in the incidence of post-operative SSI in patients who received up to 24 hours of prophylactic antibiotics compared to those who received more than 24 hours of antibiotics.

The risk of post-operative SSI in the African setting is low and comparable to other studies in the developed world.7,8 It is however higher than some centres in Europe especially in more recent studies.9 This may be due to the use of more sophisticated methods of infection prevention including the use of laminar flow and space suits in the operating room.

Inherent weaknesses of the study include the small numbers of patients developing SSI and the retrospective nature of the study. The use of antibiotic-loaded cement may confound the results as there is evidence that antibiotics leaching from the cement may be as good as system-ically administered antibiotics. However, the large number of patients studied is a great strength of the study.

Our study though has shown that there may be no benefit of prolonged antibiotic use in arthroplasty given that there seems to be no difference in the incidence of SSI with the use of antibiotics for longer than 24 hours. Given the known adverse events associated with antibiotics including the emergence of resistant organisms, the use of prolonged antibiotics is unjustified. There is hence need for orthopaedic surgeons in the African region to develop protocols to guide the peri-operative management of arthroplasty patients.

References

1. Campoccia D, Montanaro L, Arciola CR. The significance of infection related to orthopedic devices and issues of antibiotic resistance. Biomaterials. 2006 Apr;27(11):2331-39. [ Links ]

2. Pavel A, Smith RL, Ballard A, Larson IJ. Prophylactic antibiotics in clean orthopedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:777-82. [ Links ]

3. Henley MB, Jones RE, Wyatt RWB, Hofmann A, Cohen RL. Prophylaxis with cefamandole nafate in elective orthopedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;209:249-54. [ Links ]

4. Prokuski L. Prophylactic Antibiotics in Orthopaedic Surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. 2008;16:283-93. [ Links ]

5. Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery: summary of a Swedish-Norwegian Consensus Conference. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30(6):547-57. [ Links ]

6. Bratzler DW, Houck PM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Jun 15;38(12):1706-15. [ Links ]

7. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic Burden of Periprosthetic Joint Infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty. May 2. [ Links ]

8. Sukeik MTS, Haddad FS. Management of periprosthetic infection in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2009;23(5):342-49. [ Links ]

9. Jamsen E, Nevalainen P, Eskelinen A, Huotari K, Kalliovalkama J, Moilanen T. Obesity, diabetes, and preoper-ative hyperglycemia as predictors of periprosthetic joint infection: a single-center analysis of 7181 primary hip and knee replacements for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jul 18;94(14):e1011-19. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr James Kigera

Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Unit PCEA Kikuyu Hospital

PO Box 45

00202 Kikuyu Nairobi

Tel: 020-2044769

Email: jameskigera@yahoo.co.uk