Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Orthopaedic Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8309

versión impresa ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.11 no.4 Centurion ene. 2012

CLINICAL ARTICLE

Outcomes of the treatment of gunshot fractures of lower extremities with interlocking nails

AA OlasindeI; JD OgunlusiII; IC IkemIII

IFWACS. Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma, Federal Medical Centre, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

IIFMCS. Victoria Hospital, Castries, St Lucia, West Indies

IIIFMCS. College of Medicine, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

Gunshot injuries are gradually on the increase in civilian populations in developing countries due to the increase in violence in our society. The treatment of fractures from such injuries is changing with the use of locked intramedullary nailing becoming an acceptable and effective method of fixation. The Surgical Implant Generation Network (SIGN) interlocking nail is gaining universal acceptance in developing countries due to its ease of use without the need for an image intensifier. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the outcome of the use of SIGN interlocking nailing in gunshot fractures of the lower limbs. This is a prospective study of all patients in three tertiary centres in developing countries who had gunshot fractures of the lower limbs fixed with SIGN nails from 1 June 2007 to 31 May 2009 and followed up for a period of two years. There were 28 patients with 31 fractures with an average age of 32.5 years ± 12.6 SD. All the patients were males except for one female. Fractures occurred in the femur in 20 (71.4%) and tibia in 11 (29.6%). The SIGN nail was used to fix all fractures, and union was achieved in all the patients. The most common complication was wound infection in five patients (15.2%). The intramedullary locked nail provided an effective method of fixation for gunshot fractures of the lower extremity with minimum complications.

Keywords: gunshot fracture, lower extremity, SIGN interlocking nail

Introduction

Gunshot injury is increasing worldwide due to the increase in violence in civilian society.1 The management of these injuries can be challenging and sometimes the prognosis may be difficult to predict in those who survive the initial assault. The nature and severity of the bullet wound depend on the characteristics of the bullet and tissue through which it travels.2 The damage to the tissue is a function of the dissipated kinetic energy which is the product of half the mass of the bullet and square of velocity (1/2m [V1-V2]2) in addition to shock wave, temporary and permanent cavitation and secondary missiles.

The bullet could also cause injuries by wadding, yawing or tumbling.

Gunshot injury of the extremities involving the bone often results in comminuted fractures with associated complex musculotendinous soft tissue injuries, the management of which is gradually becoming a continuous burden on community and hospital resources around the world.3 Civilian orthopaedic surgeons will be required to manage gunshot injuries of the extremities with frequencies that demand a thorough understanding of the principles of ballistic injury and familiarisation with the nature of low and high energy transfer wounds to soft tissue and bone.1

There is a wide range of methods that have been advocated for the treatment of these gunshot bone fractures from non-operative 'low tech' splinting through external fixation to internal fixation with locked intramedullary nails. There appears to be consensus to treat Gustilo-Anderson grades 1, II and IIIA with locked nails while external fixation is reserved for IIIB and IIIC.3 Others have also combined both external fixation with internal fixation (Damage Control Orthopaedics [DCO]), followed by intramedullary locked nailing. There is no statistically significant difference in the clinical outcome between those treated with immediate and delayed reamed intramedullary locked nailing. However, those treated with immediate interlocking nails had a shorter hospital stay with a significant decrease in hospital expenses.4 The study was conducted to evaluate the outcome of the treatment of gunshot fractures of the lower extremities in three centres located in developing countries using the SIGN interlocking nail. SIGN is an acronym for Surgical Implant Generation Network; SIGN fracture care is a nonprofit-oriented organisation devoted to the creation of equality of orthopaedic care for surgeons in developing countries.5 The SIGN interlocking nail is a solid intramedullary nail with a target arm. The target arm has a distal jig through which the slot finder is used to locate the hole in the nail for distal locking. It is designed for use with or without an image intensifier or C arm.6,7

Patients and methods

Our research is a prospective descriptive study of gunshot open fractures of the lower extremities treated with SIGN interlocking nails at three centres located in developing countries. The study was conducted over a period of two years year, from 1 June 2007 to 31 May 2009. The inclusion criteria were gunshot to the lower extremities with long bone fractures that were followed up for a minimum of two years. The exclusion criteria were patients with gunshot injuries to the lower extremities without fracture.

All the patients were adequately resuscitated and stabilised in the Emergency Room (ER). Wound debridement was done to excise necrotic tissue and copious irrigation was done with saline. Intravenous second generation cephalosporin (Cefuroxime) was administered at presentation to all the patients and continued for five days. Biographical data and information on when the patient was shot and on the assailant were obtained. The neurovascular status of the injured limbs was examined to document neural and vascular injuries. Radiographs of the affected limb were taken in two orthogonal planes - antero-posterior (AP) and lateral views (LAT) to determine the pattern of injuries and the presence of bullets or pellets (Figures 1 and 2).

The fracture was classified using the Gustilo-Anderson method of classification of open fractures. All fractures were fixed with SIGN interlocking nails. The interval between injury and surgery and associated injuries was recorded. Intra-operatively the shells (wad) were removed but the bullets and pellets were removed only if encountered during the course of wound debridement or if they were lying along the course of an artery or nerve. There was no deliberate attempt to 'chase' them. Clinico-radiological follow-up of the patients was done at the outpatients department to monitor for union. Complications like infection were looked for in the outpatient and where they were suspected a complete blood count (CBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were done at every outpatient visit. Other complications that were followed up were limb length discrepancy, delayed union and implant failure. The data obtained were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 13 and the test of significant association was done using Chi square; the level of significance was P<0.05.

Results

There were 28 patients with 31 fractures with an age range of 15 to 70 years with an average age 32.5 years ± 12.6 SD of 32.5 + 12.6 years. All patients were male except for one female patient; half of them were shot by unknown/armed bandits or assailants while the other half were shot by security agents. Twenty (71.4%) of the injuries were low velocity missile injuries and eight (38.6%) high velocity missile ones. The low velocity gunshot injuries were caused by local Dane gun and pistol while high velocity injuries were from armed bandit attacks.

There were 26 (83.9%) femoral shaft and 15 (16.1%) tibia fractures. Sixteen (61.5%) of the femoral shaft fractures were operated using the retrograde approach and ten (38.5%) had an antegrade approach.

The time interval between injury and SIGN nailing ranged from 1 to 26 days with an average of 7.8 ± 6.1days.

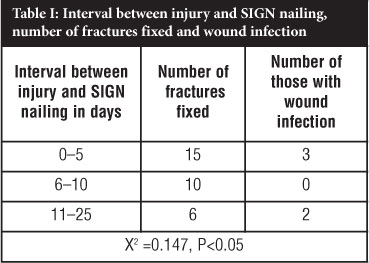

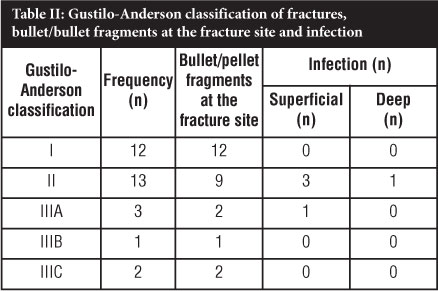

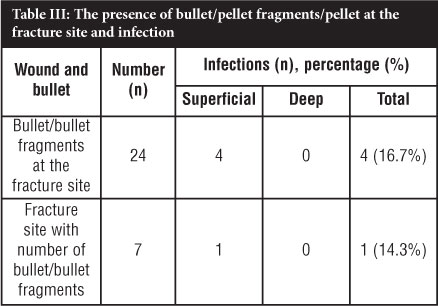

The fractures involved the right side in 13 (38.7%) patients and left side in 18 (61.3%) patients. Complications observed were wound infections in five (15.2%) cases, limb length discrepancy in two (6.5%), breakage of the distal screw in one (3.2%) and delayed union in one (3.2%) case. Of those with wound infection half had superficial infection and the other half had deep infection. Table I shows the interval between injury and surgery and the number of those with wound infection. There was no statistically significant association of the interval between injury and SIGN intramedullary nailing. Table II shows the Gustilo-Anderson classification of fractures, bullet/bullets fragments at the fracture site and wound infection. Table III shows bullet fragments or pellets at the fracture site and wound infection. The presence or absence of bullet fragments/pellets at the fracture site did not statistically affect the occurrence of wound infection (P = 0.449, CI 0.72, 1.94 OR .24, 11.63). The limb length discrepancy in the two patients was not of clinical significance as it was less than 2.5 cm. All the fractures progressed to union at between 12 and 16 weeks.

Discussion

Gunshot fractures are usually high energy injuries by definition. Studies have shown that heat generated during firing does not make the bullet sterile.8 In this study 71.8% of the injuries were caused by a low velocity missile which is similar to previous studies in developed countries where civilian gunshot injuries are most commonly low velocity, low energy missiles (300 m/sec and lower).3 The assailants in most of these cases were security agents, and sometimes injury was caused by accidental discharge during a hunting expedition. Some of the patients sustained their injuries during 'stop and search' operations by security agents. However, those with high velocity missile injuries suffered attacks by armed bandits.

Males were the most commonly injured in this study as they are the ones who are often involved in travelling in order to fend for their family. This is similar to reports in previously published papers.9,10,11 The data show the vulnerability of young productive males to sustaining long bone fractures in gunshot injury with its attendant morbidity and man-hour loss.

All the fractures were in the lower limbs of which 83.9% occurred in the femur and 45.2% around the knee. This is in tandem with other reports where the majority of the gunshot injuries were in the lower limbs.3 This may be due to the fact that the assailant's aim was to immobilise the victim either for arrest in those shot by security agents or to enable them to dispossess them of their personal belongings in those shot by armed bandits.

Standardised care for gunshot open fractures has been established in some centres in developed countries. These include operative debridement of any devitalised soft tissue and bone fragment followed by copious irrigation and early fixation. The method of bone fixation is predicated on the pattern of fracture comminution, the generalised status of the patient and local soft tissue problems encountered.3

However, there is general consensus to treat grade I and II Gustilo-Anderson staging of gunshot fracture injuries with locked intramedullary nailing, with an increasing trend among surgeons to treat grade IIIA and B with locked intramedullary nailing with good to excellent results.4 In this series SIGN interlocking nails were used to fix all fractures, irrespective of Gustilo-Anderson staging, except one who had an external fixator for a period of 26 days before intramedullary nailing was done. All the fractures progressed to union at an average of 12 to 14 weeks. This was unlike the report by Ali et al. who had nonunion in four (5.88%) of the 68 fractures caused by high velocity gunshot injuries of the femur which in their series needed a secondary procedure of bone grafting for union to occur.9

The most common complication was wound infection which occurred in 15.2% of the cases; of these, half was superficial and the other half was deep. In papers by Weil et al.12 and Mody et al.13 deep wound infection of 33% and 40% respectively was reported. However, the report by Mody et al. resulted from a war trauma setting where a higher than normal degree of wound contamination may be present. This is higher than the finding in this study. There was no case of non-union but we had one case of delayed union due to early implant failure from breakage of the two distal locking screws and early mobilisation without crutches. One of the patients with deep wound infection had gunshot injury with the entry point on the medial aspect of the tibia. The fractures were fixed statically between 1 to 26 days after the injury with 7.8 days ± 6.1 SD. Table I shows that the interval between injury and SIGN interlocking nailing did not significantly affect the infection rates in the groups. This was in agreement with findings by Molinari et al. that the operative outcome with regard to immediate, intermediate or delayed fixation has no significant difference.14

The presence of bullet/bullet fragments did not contribute significantly to the wound infection rate; neither did the presence of entry and exit wounds. Further studies with a large sample may be needed to corroborate this.

Among the 15 patients who had retrograde femoral nailing and five with tibia fracture with entry through or around the knee, 19 had restoration of normal range of motion of the knee at six months post-surgery with physiotherapy.

Conclusion

The main findings in this study relate to gunshot open fractures affecting the lower limbs in predominantly young males; infections were superficial with SIGN intramedullary nailing and union was achieved in all the patients. SIGN intramedullary nailing provided an effective intramedullary nailing device in patients with gunshot fractures of the lower limbs with union of all the fractures and reduced complications.

References

1. Mauffrey C. Management of gunshot wound to the limbs. A review. The Internet Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2006;3(1). [ Links ]

2. Hollermann JJ, Fackler ML, Coldwell DM, Menchem Y. Gunshot wounds: Bullets, ballistics and mechanism of injury. Am. J. Roentgenol 1990;155(4):685-90. [ Links ]

3. Burg A, Nachum G, Salai M, Haviv B, Velkes S, Dudkiewicz I. Treating civilian gunshot wounds to the extremities in a level 1 trauma centre: Our experience and recommendations. IMAJ 2009;11(9):546-51. [ Links ]

4. Nowotarski P, Brumback RJ. Immediate interlocking nailing fractures of the femur caused by low- to mid-velocity gunshots. J. Orthop. Trauma 1994;8:134-41. [ Links ]

5. Zirkle LG, Jr. Injuries in developing countries - how can we help? The role of orthopaedics. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008;466(10):2443-50. [ Links ]

6. Ikem IC, Ogunlusi JD, Ine HR. Achieving interlocking nails without using an image intensifier. Int. Orthop, 2007;31(4):487-90. [ Links ]

7. Ikpeme I, Ngim N, Udosen A, Onuba O, Enembe O, Bello S. External jig aided intramedullary nailing of diaphyseal fractures: Experience from a tropical developing centre. Int. Orthop. 2011;35(1):107-11. [ Links ]

8. Wolf AW, Benson DR, Shoji. H. Autosterilization in low velocity bullets. J. Trauma 1978;18:63. [ Links ]

9. Ali MA, Hussain SA, Khan MS. Evaluation of results of interlocking in femur fractures due to high velocity injuries. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2008;20(1):16-19. [ Links ]

10. Aderonmu AO, Fadiora SO, Adesunkanmi AR, Agbakwuru EA, Oluwadiya KS, Adetunji OS. The pattern of gunshot injuries in a communal as seen in two Nigerian teaching hospitals. J. Trauma 2003;55:626-30. [ Links ]

11. Persad IJ, Reddy RS, Saunders MA, Patel J. Gunshot injuries to the extremities: experience of a UK trauma centre. Injury 2005;36:407-11. [ Links ]

12. Weil YA, Petrov K, Liebergail M, Mintz Y, Mosheiff R. Long bone fractures caused by penetrating injuries in a terrorist attack. J. Trauma 2007;62:909-12. [ Links ]

13. Mody RM, Zapor M, Hartell JD, Robben PM, Waterman P, Wood-Morris R, Trotta R, Andersen RC, Wortmann G. Infectious complications of damage control orthpaedics in war trauma. J. Trauma 2009;67(4):758-61. [ Links ]

14. Molinari RN, Yang EC, Strauss E, Einhorn TA. Timing of internal fixation in low velocity extremity gunshot fractures. Contemp. Orthp. 1994;29(5):335-39. [ Links ]

Reprint requests:

Reprint requests:

Dr Anthony Olasinde

Dept. of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma

Federal Medical Centre,

Owo, Ondo state, Nigeria

Email: olasindetony@yahoo.com or olasindetony@gmail.com