Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309

Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.11 n.1 Centurion Jan. 2012

CLINICAL ARTICLE

Outcomes of osteosarcoma in a tertiary hospital

JA Shipley MMed(Orth) HeadI; CA Beukes MMed(Anat Path)II

IDepartment of Orthopaedics. University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

IIDepartment of Anatomical Pathology. University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Thirty consecutive cases of osteosarcoma treated over a five-year period were reviewed retrospectively. The cases were notable for the advanced stage of disease at presentation with half the patients presenting with metastases, and unusually large mean tumour sizes. The majority of patients needed amputation for local control of the tumour. Although follow-up is short, a third of the patients are disease-free at a mean of 30 months and a sixth alive with metastases at a mean of 16 months. Half the patients are presumed or known to be dead. Presence of metastases at diagnosis and size greater than 10 cm were associated with a poor prognosis.

Key words: osteosarcoma, outcomes, South Africa

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the commonest primary malignancy of bone, excluding tumours of haemopoietic tissue, and constitutes about a quarter of all types of sarcomas seen at our tertiary referral centre. Our subjective impression was that our patients come largely from rural areas, and are referred at a late stage, when limb-sparing surgery is impossible. Many patients already have systemic spread of their disease and their survival is poor. Informal discussions with colleagues from other centres suggest that our experience is not isolated, and that factors such as the insidious onset of the disease as well as poor peripheral referral systems contribute to the problem.

A retrospective study was performed to assess the status at presentation and outcome of our patients over a five-year period.

Patients and methods

Orthopaedic, paediatric and adult oncology records from January 2006 to December 2010 were reviewed retrospectively for details of osteosarcoma patients treated at the Universitas Academic Complex in Bloemfontein.

Universitas Academic Complex is a tertiary referral centre for the whole of the Free State, Northern Cape and adjacent areas of the Eastern Cape and North West provinces, with a combined population of some 4.2 million people. In addition, we provide tertiary services to the 1.7 million inhabitants of Lesotho. The combined total of about 6 million people from central South Africa live largely in rural areas, and follow-up, either in Bloemfontein or in oncology outreach clinics at the three major towns in the area, is often unreliable.

Patient records were retrospectively reviewed and analysed for age at presentation, gender, presenting complaint, duration of symptoms, site, histological type of tumour, tumour stage, type of treatment and duration of survival at last follow-up. An attempt was made to correlate survival with the stage of the tumour using both the Enneking/Musculo-skeletal Tumour Society and the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Systems. The size of the tumour measured on pre-operative MRI, digital X-rays or on the resection specimen was also compared to survival.

Results

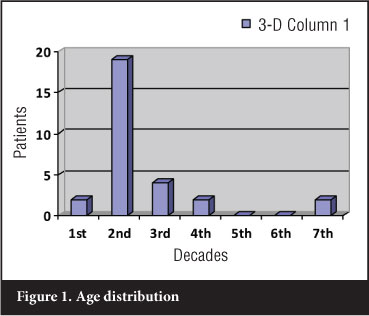

Thirty cases of osteosarcoma were treated during the five-year period from January 2006 to December 2010. Nineteen patients were male and 11 female; ages ranged from 8 to 69 years, but the vast majority were in the second decade of life (Figure 1).

Pathology

Twenty-six cases presented with a mass on the affected limb, which had been present for a mean of 6.3 months (range 1-26 months). Three patients were referred with pathological fractures, one of which was only recognised following internal fixation and failure to heal, and another with leg pain without a palpable mass.

The distal femur was involved in 17 cases, the proximal tibia or fibula in six and the proximal femur in three. Unusual tumours were the two cases with soft tissue osteosarcomas of the upper limb, and one case each of conventional osteosarcoma in the tibial diaphysis and the ilium.

Fifteen tumours were classical osteoblastic, five chondroblastic, two telangiectatic, two fibroblastic and two soft tissue osteosarcomas on histological examination. Single cases of high grade surface, dedifferentiated parosteal, periosteal and sclerotic osteosarcomas were seen.

Tumour size and staging

Tumour size was measured in 29 cases and varied from 2 x 1.2 cm to 35 x 25 cm; the mean size was 16.1 x 12.8 cm. One patient had an amputation elsewhere and the tumour size is unknown. Only eight tumours were 10 cm or less in size, of which five measured 8 cm maximum diameter or less. Eight cases were between 10 and 15 cm, six between 15 and 20 cm and seven exceeded 20 cm. Fourteen patients had distant metastases at presentation, one had a skip lesion, and two more developed metastases within two months of presentation.

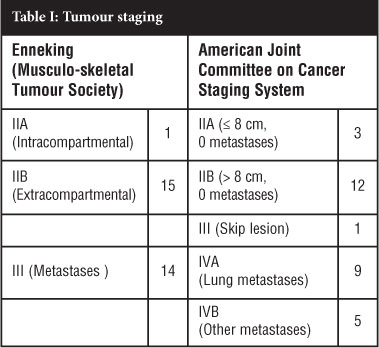

Tumours were staged by the Musculo-skeletal Tumour Society (Enneking) System and the American Joint Committee On Cancer Staging (AJCCS) Systems (Table I). Only one patient had stage IIA (intracompartmental) disease, 15 stage IIB (extracompartmental), and 14 had stage III (metastatic) disease by the Enneking System. Using the AJCCS System, three patients were stage II A (no metastases, tumour size 8 cm greatest dimension or less), 12 were stage II B (no metastases, tumour larger than 8 cm), one was stage III with a skip lesion, and 14 were stage IV with lung or other metastases (Table I).

Treatment

Four cases, including the patient treated by amputation elsewhere, were given palliative treatment. Chemotherapy was started in 22 cases. Three patients refused surgery, one of whom completed a number of courses of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and then opted for radiotherapy which failed to control the tumour locally or systemically.

Amputation was performed in 21 patients; 12 had hip disarticulations, and seven above-knee (transfemoral) amputations. One patient with osteosarcoma of the ilium had a hind-quarter amputation, and another with a tibial diaphysis tumour a knee disarticulation. No patient had a local recurrence following amputation.

One patient had a wide resection of a soft tissue osteosarcoma, and another a wide excision of a periosteal osteosarcoma of the distal femur, followed by a tumour prosthesis. Lung metastases were resected in three patients.

Outcomes

Four patients were terminal and were given palliative treatment, surviving between 2 and 14 days. Five patients defaulted, or were lost to follow-up and are presumed dead. Six patients survived a mean of 12 months (6 weeks to 39 months) before dying of disease. Five patients have survived a mean of 19.4 months (6 to 27 months) with metastases, and ten patients are alive and free of disease a mean of 30.3 months (4 to 60 months) after they started treatment.

Only two patients not treated by tumour resection have survived, both of them with metastases, one of them very extensive.

Enneking stage and outcome

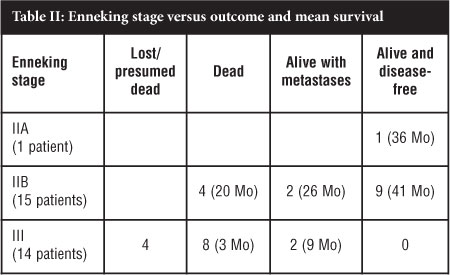

All ten patients who are alive and disease-free for a mean period of 30.3 months were Enneking stage IIA or IIB; eight had amputations, and two limb-saving wide resections. Four patients with Enneking stage IIB disease died after a mean of 20 months (9-39 months) while two more are still alive with metastases 25 and 27 months respectively after starting treatment (Table II).

AJCCS stage and outcome

The three AJCCS stage IIA patients are all alive without disease after a mean of 45 months (36-60 months). The five stage IIB patients who are disease-free have survived a mean of 25 (4-48) months, and two more are alive with metastases at 25 and 27 months; the four other IIB patients lived a mean of 17.5 (11-39) months. The single stage III patient was disease-free at 6 months when he was lost to follow-up.

For practical purposes the 14 patients with metastases at presentation staged as Enneking stage III or AJCCS stages IVA and IVB will be considered together. Twelve of the 14 patients are known or presumed to be dead; nine patients are known to have survived a mean of 3.6 months (3 days to 17 months). Two patients are alive with metastases 6 and 9 months after they started treatment; one has a soft tissue osteosarcoma of the elbow and avoided surgery, the other had a hip disarticulation and has lung metastases that are controlled by chemotherapy.

Tumour size and outcome

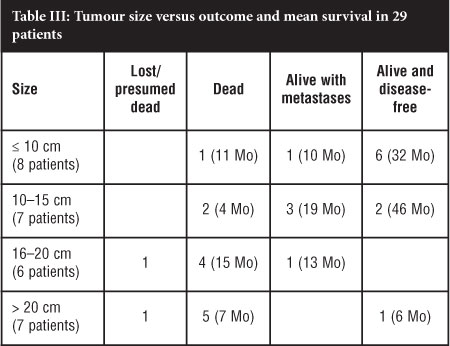

The relation between tumour size and survival is given in Table III, and there appears to be a watershed between outcomes of tumours above or below 10 cm maximum diameter. Of the eight patients where the tumour was 10 cm or less in size, six are disease-free after a mean of 32 months, one has survived with metastases for 10 months and one died after 11 months. When the tumour was between 10 and 15 cm in size, only two of the seven patients are tumour-free at 44 and 48 months respectively; three have metastases with a mean survival of 19 months (6-27 months) and two have died. Of the 13 patients whose tumour was larger than 15 cm, only two patients have survived; one is disease-free at 6 months, and the other has possible metastases at 13 months. Twenty patients (71.4%) had tumours larger than 10 cm; 13 of them had metastases on presentation, and another two developed metastases within 2 months.

Overall 6/8 (75%) patients with tumours 10 cm or less were alive and disease-free at a mean of 32 months, and another had survived 10 months with metastases; the mean survival of the whole group of seven cases was 27 months. In contrast only 7/21 (33%) patients with tumours larger than 10 cm were alive at an average of 24 months, four of them with metastases; the mean overall survival of the 17 patients in this group where this was available was 15 months (Table III).

Discussion

This study is limited by the small number of patients, its retrospective nature, and the difficulties of following a largely rural patient population. Nevertheless it clearly shows a number of important findings; slightly more than half of our patients had metastases at or within 2 months of our first seeing them, and three-quarters of these cases died of their disease; the majority of these patients had tumours larger than 10 cm in size. In contrast, the small number of patients with tumours smaller than 10 cm did well, with three-quarters of them alive and disease-free, and one patient alive with metastatic disease. The advanced stage of disease at presentation in our cases is also shown by the size of their tumours, which measured a mean of 16 x 12.6 cm.

Overall, nine patients (30%) are alive and disease-free a mean of 32 months after presentation; another five (17%) are alive with metastases at a mean of 16 months. The mean period of survival of the 14 living patients (47%) is 26 months. The short period of follow-up in many of these survivors limits the conclusions that can be made about long-term outcomes. Fourteen patients are known to have died; three are lost to follow-up with advanced disease and presumed to be dead. The two factors associated with a favourable outcome in this group of patients was tumour size less than 10 cm, and absence of metastases at the time of referral.

Wide excision of the primary tumour was performed in most cases where the patients condition allowed surgery, and this provided reliable local control of the disease; most cases were beyond limb salvage surgery but amputation was justified even in advanced cases for relief of pain and improved mobility and quality of life. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy was a problem as some potentially curable cases subsequently refused surgery, and our oncologists are now very selective in offering this treatment. The decision on amputation is often a social rather than a medical issue; the patients family must be involved if they are responsible for the future care and support of a disabled person in a poor rural setting.

Comparisons with other reported series are difficult as few of them deal with such large or advanced tumours. Much of the recent literature is concerned with chemotherapy regimens, and this will not be discussed here.

Recent studies report a five-year survival for treatment of osteosarcoma between 50% and 75%,1 but a realistic figure is probably closer to 50% as shown by two large recent studies. Pakos et al¹ reported a 52% five-year survival among 2 680 cases in an international multicentre study. Damron2 et al reviewed 8 104 osteosarcoma patients in the USA National Cancer Data Base, and found a five-year survival rate of 53.9%; this did not vary significantly over the period 1985 to 2003.

Only one series from Africa could be traced; Muthupei and Mariba3 reported a one-year survival of 26% and a five-year survival of 7.5% in 66 patients treated at Ga-Rankuwa Hospital over a 10-year period. Our small group of patients has not been followed long enough to provide figures for comparison to overseas studies, but their survival so far has been better than I expected.

Pakos et al1 analysed the prognostic factors in osteosarcoma in 2 680 cases in an international multi-centre study. Metastases at diagnosis increased the risk of mortality by a factor of 2.89; metastases were present in 13% of their cases compared to our 47%. They had insufficient data to correlate tumour size with outcome, but gave their median tumour size as 10 cm, considerably smaller than our own series. They documented an increased risk of death and metastasis when amputation was performed rather than limb salvage, possibly because the amputation patients had slightly larger tumours (mean 12.7 cm compared to 10.5 cm). Local recurrence of tumour occurred in 16% of their cases, increasing the risk of death by a factor of 3.04, and emphasising the importance of local control of the malignancy; however they found only a marginal reduction in local recurrence after amputation.

Petrilli et al4 reported a multi-centre series of 209 patients from Brazil, perhaps more closely related to South African circumstances. Although 21% had metastases at diagnosis and 43% of their tumours exceeded 12 cm in size, these figures are still far lower than ours of 47% and 70% respectively. They had an overall five-year survival of 50.1%, with 60.5% survival for the cases without metastases at presentation. As with our cases, factors associated with shorter survival were metastases at diagnosis and tumour size, both of which were related to each other. The overall amputation rate was 38%, and there was a 14.3% local recurrence rate after limb-sparing surgery.

Limb-salvage surgery was popularised after the work of Simon5 and Rougraff,6 and has become the standard treatment of bone malignancies. It is accepted that provided adequate surgical margins are achieved, there is no difference in survival between cases treated by amputation and limb salvage. Limb-salvage surgery for bone tumours is more difficult than that for soft tissue sarcomas as the skeleton must be reconstructed by structural graft or prosthesis; both often require multiple re-operations, lengthening is difficult in a growing child, and the implants are extremely expensive. Generally, amputation is reserved for large tumours where a wide resection would mean the sacrifice of critical neurovascular structures. Nevertheless, local recurrence of tumour after limb salvage is reported in 5.4% to 16%1,4,6-8 of cases, and such a recurrence is associated with a very high mortality. Wide excision is difficult below the knee where tumours are close to neurovascular structures and important tendons, so amputation and a prosthesis is far more acceptable as it allows a wide surgical margin and very similar functional results.

Tumours arising in the femur, however, are best treated by limb salvage or rotationplasty, as prosthetic fitting after amputation above the knee is often difficult or impossible, and gait, mobility, driving and psychological problems are far more common after amputation.9 Despite this, employment and sport activities are similar in these groups of patients. Hopyan et alw concluded that there is 'modest functional advantage to those with limb-sparing reconstruction over those with above knee amputation in the absence of complications'. There was minimal evidence of greater physical activity, with no psychological disadvantage, among those who had undergone rotation-plasty.

The high rate of amputation in our series, rather than limb salvage surgery, is obviously inconsistent with modern tumour surgery. Considering the above discussion, it is critical to achieve local surgical control of the malignancy; given the unusually large size of the tumours we deal with we believe that very few of our patients qualify for limb-sparing surgery. The practical difficulty of following up and treating a largely rural population means the operation performed must be the one most likely to prevent local recurrence; this usually means amputation, even though it is often socially unacceptable in the South African population.

Conclusion

Thirty consecutive cases of osteosarcoma treated over a five-year period were reviewed retrospectively. The cases were notable for the advanced stage of disease at presentation with half the patients presenting with metastases, and mean tumour sizes much larger than other reported series. The majority of patients needed amputation for local control of the tumour. Although follow-up is short a third of the patients are disease-free at 30 months and a sixth alive with metastases at 16 months. Half the patients are presumed or known to be dead.

Although at this stage the follow-up is short, the results appear encouraging, but they do not compare with overseas studies. The critical factor is the advanced stage of the tumours when patients are referred to us for treatment. The only way our results can improve is if the referring clinics and staff are educated in the need for a high level of suspicion and early orthopaedic referral despite the rarity of these tumours. The simple message must be - if a teenager has a painful mass around the knee it needs emergency referral.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor D Stones and Dr A Bester for their help in providing access to their departmental records and for their hard work in treating and following these cases at their clinics.

No benefits of any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

1. Pakos EE, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes for osteosarcoma: An international collaboration. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2367. [ Links ]

2. Damron TA, et al. Osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and Ewings sarcoma. National Cancer Data Base Report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;459:40-47. [ Links ]

3. Muthupei MN, et al. Osteosarcoma at Ga-Rankuwa Hospital: 10-year experience in an African population. C Afr J Med 2000;46(2):41-43. [ Links ]

4. Petrilli AS, et al. Results of the Brazilian Osteosarcoma Treatment Group Studies III and IV: Prognostic factors and impact on survival. J Clinical Oncology 2006;24(7):1161. [ Links ]

5. Simon MA, et al. Limb salvage treatment versus amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68:1331-37. [ Links ]

6. Rougraff BT, et al. Limb salvage versus amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:649-56. [ Links ]

7. Bacci G, et al. Local recurrence and local control of non-metastatic osteosarcoma of the extremities: a 27-year experience in a single institution. J Surg Oncol 2007;96:118-13. [ Links ]

8. Lindner NJ, et al. Limb salvage and outcome of osteosarco-ma. The University of Muenster experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;358:83-89. [ Links ]

9. Pardasaney PK, et al. Advantage of limb salvage overampu-tation for proximal lower extremity tumours. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;444:201-208. [ Links ]

10. Hopyan S, et al. Function and upright time following limb salvage, amputation and rotationplasty for paediatric sarcoma of bone. J Paediatr Orthop 2006;26:405-408. [ Links ]

Reprint requests:

Reprint requests:

Dept of Orthopaedics National Hospital Private BagX20598

Bloemfontein, 9301

Email: shipleyja@gmail.com.za